Abstract

In 2018, a group of faculty members and students from King Mongkut’s Institute of Technology, Ladkrabang (KMITL), and Royal College of Art (RCA) organized workshops and field trips to Sukhothai province in Thailand to explore the livelihood along with cultural heritages, social practices, and sustainable learning by the inhabitants of communities in Si Satchanalai district. Conceptually informed by Spencer Kagan’s notion of Cooperative and Collaborative (C&C) sustainable learning approach employed by the KMITL-RCA collaborations, this research examined the 2018 workshops and excursions for their roles in 1) advancing tacit knowledge on the artistic and architectural heritages of Si Satchanalai; and 2) bridging a horizon of understanding between Thai and foreign students. In order to assess the pedagogical efficacy of the C&C approach, the upcoming evaluative discussions encompassed a series of dependent sample t-tests, utilizing several questionnaires, surveys, and personal conversations for collecting data to construct a content model in terms of comparative studies between the KMITL and RCA participants. Not only did the statistical inquiries: 1) validate the methodological applicability of the C&C edifying model but also 2) demonstrate its merits in promoting cross-cultural learning in architectural and design discipline.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

As a part of the ongoing paradigmatic shift from the Eurocentric confinements, this research examined the methodological applicability of Cooperative and Collaborative (C&C) approach in architectural and design education, by using by a series of workshops and study trips to Si Satchanalai district in northern Thailand as the case study. Jointly organized in 2018 by a group of students and faculty members from King Mongkut’s Institute of Technology, Ladkrabang (KMITL), and Royal College of Art (RCA), the 10 day-activities aimed to explore the livelihood, cultural heritages, social practices and sustainable learning of the local people. Incorporating both qualitative and quantitative methods, the analytical discussions revealed that not only did the C&C model employed by the KMITL-RCA fieldwork advance the tacit knowledge of the Thai and British participants on artistic and architectural heritages of Si Satchanalai, but also contribute to their learning achievements by promoting cross-cultural interactions among all involving parties.

1. Introduction

As exhibited by continuous growth in academic and popular publications on the architecture of non-Western cultures since the 1990s (Bozdogan, Citation1999, pp. 211, 214), the contemporary architectural discourse had progressed toward a greater interest in cross-cultural studies stressing on relationships between the built environment and cultural contexts beyond the Eurocentric confinements. Accompanying the aforementioned change were expansions of the coverage and profundity of architectural and design pedagogy, wherein historical developments of built forms in non-Western contexts had been integrated into many English language textbooks and survey courses. The most notable occurrence, however, could be seen from an increasing number of leading universities in North America, Europe, and Australia, offering their students more variety of study abroad programs in Asia, especially those in the Indo-Pacific region (Pieris, Citation2015, pp. 2–6).

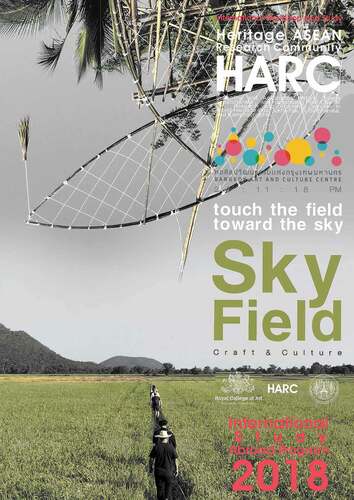

In response to such a paradigmatic shift, the Department of Architectural and Design Education, School of Industrial Education and Technology, King Mongkut’s Institute of Technology, Ladkrabang (KMITL) in Thailand had established joint-workshops and study trips with its foreign partners since 2013. In mid-November 2018, 4 KMITL faculty members and 10 students plus 1 professor and 10 students from the London-based Departments of Architecture, School of Design, Royal College of Art (RCA) embarked on a series of workshops and field trips to investigate the livelihood in company with cultural heritages and social practices by the denizens of Si Satchanalai district in Sukhothai province. Situated 450 km away from Bangkok in the lower northern region, these communities also bordered Si Satchanalai Historical Park, one of the UNESCO World Heritage Sites in the country (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), Citation2017). Apart from producing well-documented field reports and photographic archives, the 10 day-activities culminated in a public seminar at Bangkok Art and Cultural Center (BACC) by the end of the month, featuring a couple of field-based research projects undertaken by the participants.

Informed by Spencer Kagan’s approach in Cooperative and Collaborative (C&C) pedagogy (Kagan , 1994 ; Kagan , 2009), the fieldwork in Si Satchanalai intended to explore the academic relevance of cross-cultural studies in architectural and design education. In order to facilitate cross-cultural learning experiences, the KMITL and RCA students were mingled together and subdivided into two teams. Although their topical foci contained a mixture of interests, the KMITL-RCA collaborative efforts operated under a shared theme on expressions of cultural identity in built forms (for more information, see Heritage ASEAN Research Community (HARC), Citation2018).

The abovementioned activities supplied a contextual background for this research to demonstrate the pedagogical efficacy of the C&C approach utilized by the 2018 workshops and excursions in advancing cross-cultural studies. By resorting to the method of “authentic assessments” (see: Cooper & Robinson, Citation1998), the investigations evaluated the values of the 2 KMITL-RCA research projects in 1) expanding tacit knowledge of the students on the art and architecture heritages of Si Satchanalai; and 2) bridging a horizon of understanding between dissimilar bodies of participants; one grounded in their cultural roots (KMITL) whereas the other did not (RCA).

In addition, by appropriating a framework of references from the Cognitive domain in Bloom’s taxonomies (), the inquiries incorporated a series of dependent sample t-tests (Total Average Compare Mean) for comparative studies between the KMITL and RCA members in several key areas. As would be shown by the upcoming discussions, these statistical analyses revealed that: 1) not only was the C&C approach methodologically suitable for architectural and design education; but 2) its pedagogical applications also benefited cross-cultural learning, as demonstrated by several scholarly improvements that led to many academic achievements of the students from KMITL and RCA alike.

2. Theoretical foundation and methodological approach

2.1. Cross-cultural studies

As human beings in the present day had become rapidly interconnected, scholars of cross-cultural studies maintained that the ways in which one culture constructing meanings of the world could influence how people perceived themselves and other cultures. By challenging the dominance of Eurocentric epistemology, the paradigmatic shift toward cross-cultural studies had generated far-reaching effects across disciplinary boundaries, including queries on intellectual legitimacy of conventional narratives in art and architecture education (Jarzombek, Citation1999, pp. 197–198).

In examining the mechanisms by which knowledge, ideas, skills, instruments, and practices are disseminated across cultures, scholarly literature on cross-cultural studies had fashioned innovative concepts to explain the order of things. According to Ben-Zaken (Citation2010, pp. 163–167), cross-cultural exchanges happened at a cultural hazy locus, where the margins of one culture overlapped the other, thus generating a “mutually embraced zone” where human interactions took place. From such a nexus of contacts, ideas, styles, instruments, and practices cultural notions evolved (Ibid).

In arts and architecture, cross-cultural studies fostered awareness of built forms through their relationships with methods of communication, modes of representation, and identity formations. As elaborated by Ben-Zaken, not only did cross-cultural studies develop an appreciation for cultural traditions other than one’s own, but also an understanding of the interdependent nature of world society as well as meanings of existence in a multi-faceted society in both local and global terms (Ibid).

With regard to the 2018 KMITL-RCA collaborations in Si Satchanalai, cross-cultural studies supplied a philosophical framework for bridging a horizon of understanding between the Thai and foreign students (as well as faculty members). Nevertheless, since the concept of cross-cultural studies had still been evolving, assumptions on what it stood for must be questioned constantly, because there had been no single definition that could account for all theoretical positions currently branding themselves as “cross-cultural studies.” Some theoretical premises were irreconcilable or even contradictory with others, as exemplified by: 1) scholars who recognized cross-cultural studies as designating an amorphous collection of discursive practices–e.g., the post-colonial and post-modern theories–versus; 2) those who identified cross-cultural studies as a historical set of cultural strategies, such as hermeneutics, phenomenology, structuralism, and semiotics (for example see H. Bloom, Citation1975; Parry, Citation1987; Kent, Citation1993; Mugerauer, Citation1995; Burke, Citation1997; Jarzombek, Citation1999; Ben-Zaken, Citation2010).

While acknowledging the problems of incompatibility, this research did not seek to reconcile them but instead utilized cross-cultural studies as a guiding principle for constructing a pedagogical model for architectural and design education. Its modus operandi centered around dialectical dialogues between two oppositional discourses of 1) Orientalism, the Eurocentric perception and depiction of non-Western societies and cultures or “the East,” thus reinforcing the hegemony of the West; and 2) Occidentalism, the stereotypical views and images of “the West” by non-Western people manifested through attempts to forge their own cultural identities as a response to the Orientalist discourse (see Said, Citation1978; Carrier, Citation1995).

For that reason, both KMITL and RCA students were encouraged to scrutinize their objects of investigation as they were socially perceived, culturally conceived, physically used, and psychologically experienced, in terms of cultural artifacts of which meanings were generated via social practices, perceptions, and interpretations. An obvious case in point could be observed from a Lefebvrian reading on social space in that it was constructed and lived, before being construed and conceptualized (Lefebvre, Citation1991, pp. 34–36, 143). Hence, the connections among works of arts and architecture were vital for comprehending the built environment beyond the socio-economic and political frameworks that brought it to the existence, or merely as a representation of ideas and social relations. Rather, built forms were conditioned by them, as much as conditioned them (Perera, Citation1998, 2).

2.2. Cooperative and collaborative learning

Since the 1990s, a renowned American educational psychologist, Spencer Kagan, had devised roughly 200-classroom structural “modules” to implement what he called Cooperative and Collaborative (C&C) learning. Emphasizing positive interpersonal peer relationships, equality, self-esteem, and achievement, Kagan’s modules called for group efforts from students, using material or content selected by themselves and/or assigned by their teachers (see Kagan, Citation1994; Kagan & Kagan, Citation1998; Kagan, Citation2009).

Owing to adaptability to suit a particular student body, Kagan’s structural approach could serve various goals, ranging from 1) building team spirit and constructive relationships among students; 2) sharing information; 3) nurturing critical thinking; 4) developing communication skills; 5) achieving mastery (learning/remembering) of specified materials. By appropriating the concept of Multiple Intelligences (MIs) developed by Gardner (Citation1993), many of Kagan’s learning modules could be mixed and matched, rendering them very flexible and therefore highly capable of fulfilling multiple learning objectives at the same time (Kagan & Kagan, Citation1998, pp. 76–86).

To cite an example of practical applications, Kagan and Kagan (Citation1998, pp. 86–97) advocated Collaborative Learning (CL) activities that promoted various MIs via peer collaborative tasks, involving skills such as drawing, classifying, computing, moving the body, requiring students to collaborate in teams (interpersonal), or be introspective (intrapersonal). As indicated by several studies, the utilization of interpersonal intelligence CL structures enabled instructors to target interpersonal effectiveness for student development, which in turn cultivated a harmonious social environment in classrooms (for instance, see Ciaramicoli & Ketcham, Citation2000; Goleman, Citation1995; Goodman, Citation2002; Kagan & Kagan, Citation1998; Meyers, Citation1994).

Espousing on the above methodological premises, Kagan’s structural approach in combination with Gardner’s notion of MIs contributed an operational underpinning to justify the use of the Cooperative and Collaborative (C&C) learning method for the 2018 KMITL-RCA workshops and field trips. Nonetheless, the term C&C in this context referred to a learning model in which diverse students teamed up to explore significant questions or carry out meaningful field-based research projects during their 10 day-stay in Si Satchanalai.

In essence, crucial to the C&C learning method was a manageable-sized working party, which performs as a place where: 1) learners actively participated; 2) teachers became learners and vice versa; 3) everyone was respected and supported; 4) assignments and questions captivated and challenged students; 5) diversity was celebrated and all contributions were valued; 6) students acquired skills for resolving conflicts when they arose; 7) members drew upon their experience and knowledge; 8) goals were clearly defined and kept in mind as a guideline; 8) research tools like the Internet were made accessible; 9) students invested in their learning, and 10) cooperative groups acted in unison as a single and cohesive unit.

However, caution must be heeded that the terms “cooperative” and “collaborative”, when applied to learning, were not the same. Rockwood (Citation1995a, Citation1995b) differentiated the 2 from each other. While the former denoted a methodology of choice for foundational knowledge (i.e., traditional knowledge), the latter was associated with the social constructionist’s view that knowledge was a social construct. He also distinguished these terms by the roles of instructors. In cooperative learning, the instructor became the center of authority in the class, issuing more closed-ended group assignments with specific answers to the students. On the contrary, in collaborative learning, the instructor abdicated his/her authority and empowered small groups of learners via more open-ended and complex tasks (Ibid, Ibid).

As for the 2018 KMITL-RCA collaborations, both approaches were incorporated to suit dissimilar levels of academic maturity of the participants, whereby: 1) a more structured cooperative learning style was used for foundational knowledge; and 2) a laissez-faire approach was employed for collaborative learning on a higher level of knowledge that dwelled less on factual content but more on analytical, interpretative, and critical aspects. Moreover, in tandem with collaborative and cooperative learning, other terms and/or strategies were utilized as well, for instance: 1) team learning, 2) problem-based learning (PBL)–such as case studies and simulations–and 3) peer-assisted instruction, like workshops and discussion groups (for their detailed definitions, see MacGregor, Citation1990; Smith & MacGregor, Citation1992,; Cooper & Robinson, Citation1998).

Taken as a whole, the 2018 workshops and excursions were systematically arranged to foster cooperative learning opportunities–which according to Kagan and Kagan (Citation1998, pp. 86-98)–constituted a specific form of collaborative learning. As stated earlier, the students worked together on sets of structured research activities and were held accountable for their assignments both individually and collectively, thus requiring each member to closely collaborate with his/her colleagues. Consequently, face-to-face communication and joint effort were quintessential and indispensable for success. Aside from developing interpersonal skills, the KMITL and RCA partakers: 1) shared their strengths; 2) mitigated weaker skills of the teammates, and 3) learned to deal with personal as much as cultural conflicts. Operating under the guidance of clear research objectives from the instructors, the cooperative groups engaged in numerous activities that improved their overall understanding of the subjects and objects of investigations, which would be elaborated on in detail later in forthcoming analyses.

2.3. Learning achievements

When measuring the pedagogical efficacy of the 2018 KMITL-RCA fieldwork in Si Satchanalai, it became apparent that the concept of learning achievement was quintessential. Djamarah (Citation1994, p. 19), defined learning achievements as the outcomes of educational activities that had been done, which could be measured individually and collectively.

As portrayed by , 6 levels of learning behaviors in the Cognitive Domain of the taxonomies conceptualized by a renowned American educational psychologist Benjamin Bloom in 1956 acted as the key index performance (KPI) to assess learning achievements. These sextuple KPIs–varying from the lowest to highest echelons–encompassed the ranks of 1) knowledge; 2) comprehension; 3) application; 4) analysis; 5) synthesis; and 6) evaluation (B.S. Bloom, Citation1956, pp. 1–7).

Although the taxonomy had been widely criticized, reinterpreted, elaborated, and expanded since its creation in 1956, it had remained one of the crucial models that contributed to educational developments in the 21st century (Soozandehfar & Adeli, Citation2016, p. 1). Fundamentally, Bloom’s taxonomy of learning behaviors might be thought of as the goals of the learning process, implying that students should have acquired new skills, knowledge, and/or attitudes after a learning session. Nonetheless, the upcoming discussions solely addressed the Cognitive domain and touched upon neither the realms of Affective nor Psychomotor due to the following reasons.

First, the Affective domain dealt with emotions and attitudes, which were abstract and very time-consuming to justify. As a consequence, within a short period, the instructors were unable to evaluate the KMITL and RCA students in terms of changes in attitudes, emotions, and feelings that resulted in their growing appreciation, enthusiasm, motivation, and awareness. Second, the RCA partakers were nearly devoid of any prior knowledge on the cultural heritage of Si Satchanalai. Hence, it would be methodologically unsound to appraise them on the Psychomotor domain in terms of tangible developments in behavior and skills, as opposed to the KMITL counterparts, some of whom already possessed a significant amount of ethnographic knowledge on the same subject matter, owing to their previous travels to the area before 2018.

With regard to what constituted the definitions of “learning achievements” in this research, the term “knowledge” referred to an understanding on the cultural heritages of Si Satchanalai acquired from cross-cultural experiences during the 2018 workshops and field trips, whereas “skills” denoted a team-working process in combination with communication and problem-solving abilities. In addition, aside from alluding to the abilities of the KMITL and RCA students to learn the social, cultural, and spatial practices, together with design and planning approaches from the denizens of Si Satchanalai, “skills” characterized the abilities to advance critical and creative thinking capabilities, as well as to make progress on formulating a dialectical awareness among human beings, their livelihood, and the built environment by engaging in cross-cultural interactions.

2.4. Authentic assessment

Wehlage, Newmann and Secada (Citation1995, p. 2) identified authentic assessment as the measurement of “intellectual accomplishments that were worthwhile, significant, and meaningful,” which could be devised by an instructor, or in collaboration with students by incorporating their inputs and actions. When applying the method of authentic assessment to learning achievements, an instructor resorted to the criteria related to “construction of knowledge, disciplined inquiry, and the value of achievement” beyond the confinement of classrooms (Scheurman & Newman, Citation1998, p. 23). On that account, a practice of authentic assessments called for a holistic procedure in active learning to be implemented on a pedagogical approach utilizing the C&C model. Examples included a project-based learning lesson (PBL) that focused on a set of contextualized tasks, enabling the participants to exhibit their scholarly competency of in a more “genuine” setting, as evident from the 2018 KMITL-RCA fieldwork (see Cooper & Robinson, Citation1998, p. 383).

In a few words, the authentic assessments on the pedagogical efficacy of the KMITL-RCA collaborations in cultivating cross-cultural exchanges and learning embodied the three constituents of 1) corporeal or actual experiences of the participating students; 2) information and ideas about both the objects and subjects of inquiries obtained and/or generated by the partakers, namely a couple of field-based research projects in Si Satchanalai; and 3) reflexive dialogue among the team members, as well as with their instructors. Operating in unison, all 3 holistic components created more profound impacts on student academic performance than other variables, such as their backgrounds and prior achievements.

As depicted by , the relationships among the triple criteria of experience, information, and ideas, as well as reflexive dialogues could be explicated as the following.

The “communicate” process was very important for constructing new “experiences.”

The “knowledge base” was vital for generating and sustaining “reflexive dialogues.”

The “create” process was very crucial for assembling “information” and conceiving “idea.”

Figure 2. The relationships among the C&C method, cross-cultural learning activities, and authentic assessments from the 2018 KMITL-RCA workshops and field trips.Source: Developed from a Diagram by Spencer Kagan, 1998, with Notations from the authors

Taken together, these 3-way connections substantiated both methodological validity and conceptual congruence between the C&C approach and cross-cultural learning employed by the 2018 KMITL-RCA fieldwork in Si Satchanalai (), as would be demonstrated later by the authentic assessments on the 2 field-based research projects ( and ).

Figure 6. A Geometrical Analysis of Typical Phra Ruang Kite.Source: The authors, with Notations from Ratchakrit and Sorakrich Techapaphawit, 2018

Figure 7. An analysis on the forces of lift, weight, trust, and drag on Phra Ruang Kite.Source: Developed from Hulslander, Citation2012, with Notations from the authors

3. Research questions, objectives, procedures, themes of discussion, and modes of problematization

Incorporating a mixture of both qualitative and quantitative methods, this research intended to: 1) explore the methodological applicability of the C&C edifying model in cultivating cross-cultural experiences on the livelihood, cultural heritages, social practices, and sustainable living of the people in Si Satchanalai district; and 2) examine the pedagogical efficacy of the C&C approach in promoting cross-cultural learning in architectural and design education.

By using the 2018 workshops and field trips as the case study, the following enquiries comprised the principal research question. First, how did the KMITL and RCA partakers advance their tacit knowledge on the art and architecture heritages of Si Satchanalai? Second, how did the 2 research projects and related activities employed by the 10-day fieldwork bridge a horizon of cross-cultural understanding between the Thai and British participants? Third, how effective was the C&C approach in cultivating cross-cultural exchanges and experiences for the KMITL and RCA students in terms of learning achievements?

In addition, being a tripartite investigation, the themes of discussions initially operated under the conceptual framework and theoretical guidelines of cross-cultural studies. Consequently, the analytical narratives in the first section concentrated on the ways in which the gaps of understanding between the KMITL and RCA parties were overcome by their research assignments. Afterward, the focus of inquiries shifted to statistical investigations. Informed by Kagan’s C&C methodological applications, the inquiries in the second part of the research resorted to the method of “authentic assessments” (see Cooper & Robinson, Citation1998) to determine the values of the 2 KMITL-RCA research projects in promoting cross-cultural learning and exchanges. The appraisals were graciously provided by 25 audiences who attended the public seminar at BACC by means of surveys. In order to negate possible conflicts of interests that might influence the outcomes of the appraisals, merely 3 out of the 25 referees took part in the workshops and study trips in the district of Si Satchanalai.

Next, by appropriating a framework of references from Bloom’s learning taxonomies () (see B.S. Bloom, Citation1956, pp. 1–7), the third phase of the inquiries introduced a series of dependent sample t-tests (Total Average Compare Mean) to evaluate the pedagogical efficacy of the 2018 workshops and field trips that contributed to several scholarly improvements and accomplishments of the KMITL and RCA students. Utilizing self-assessed questionnaires in combination with personal conversations for data collections, the results were further synthesized into a content model in terms of comparative studies between the KMITL and RCA members in 20 key areas (). The outcomes of these quantitative investigations were further cross-examined and corroborated by the qualitative data obtained from individual journals in conjunction with other materials produced by the students that recorded and reflected their cross-cultural learning experiences.

Table 1. Identifications of learning activities in each criterion of authentic assessments to evaluate the pedagogical efficacy of the 2018 KMITL-RCA fieldwork in cultivating cross-cultural exchanges and learning

Table 2. Average satisfactory levels of the 5 experts from their authentic assessments on the pedagogical efficacy of the KMITL-RCA workshops and field trips in cultivating cross-cultural exchanges and learning

Table 3. Average satisfactory levels of the 20 college students from their authentic assessments on the pedagogical efficacy of the KMITL-RCA workshops and field trips in cultivating cross-cultural exchanges and learning

Table 4. Self-evaluation scores from the KMITL and RCA students (KMITL n = 10, RCA n = 10)

In any case, Bevans’ notion of inferential statistics (Bevans, Citation2020) laid a groundwork to validate the use of t-tests in this research, of which rationale consisted of triplicate accounts. First, because the KMITL and RCA members constituted a single population, the t-tests were conducted in terms of paired assessments, as shown by the “before” and “after” results in the self-evaluated questionnaires. Second, since the inquiries aimed to see whether the mean calculations of the Thais were greater or lower than those of their British counterparts and vice versa, the total of 20 one-tailed t-tests were exercised to build the content model for the comparative studies (). Third, the fact that the entire KMITL-RCA population was made of 20 students provided a justification for employing the t-tests to determine if there was a significant dissimilarity between the KMITL and RCA students in cultivating cross-cultural interactions through the C&C approach that led to their learning achievements. Although some might criticize the number of 20 KMITL-RCA participants as below the minimal requirement for 30 or above samples to ensure the methodological reliability of a t-test, an allusion to Mood et al. (Citation2007, pp. 424, 435) repudiated such a claim by counterarguing that a t-test was not useful for analyzing the samples whose size was larger than 30, because the distribution of the t-test and the normal distribution would be indistinguishable.

On that basis, it could be construed that the joint KMITL-RCA workshops and field trips relying on the C&C approach performed in the capacity of an independent variable for the subsequent evaluative investigations. As portrayed by , the knowledge and skills acquired from the two field-based research projects–which were fundamental for bridging the gaps of knowledge and cross-cultural understanding between the Thai and foreign students–assumed the role of dependent variables in two separate but closely related manners. On the one hand, operating in concert with authentic assessments, the triad criteria of 1) experience; 2) information and ideas; and 3) reflexive dialogues, were the determining factors in assessing the satisfactory levels of the audiences from the public seminar at BACC (i.e., educational specialists and students from other universities). On the other hand, functioning in association with learning achievements, the sextuple indicators of 1) knowledge; 2) comprehension; 3) application; 4) analysis; 5) synthesis; and 6) evaluation from the Cognitive domain in Bloom’s learning taxonomies (Ibid) were key elements in measuring multiple scholarly advancements that led to the academic accomplishments of the KMITL and RCA students ().

4. Contextual background about Si Satchanalai district and the KMITL-RCA fieldwork

Located 50 km. north of the current Sukhothai city, the historic town of Si Satchanalai occupied more than 320 hectares (800 acres) of land. Formerly called Mueang Chaliang, this urban settlement was founded in 1205 on the bank of the Yom River. From the 13th to 16th centuries, it developed into a major hub in manufacturing pottery and ceramics, many of which were exported to the Philippines, Japan, and Indonesia (Lau, Citation2004, p. 320). Being a secondary administrative center of Sukhothai Kingdom (1238–1438), Si Satchanalai was exclusively governed by the crown prince, as epitomized by Phaya Li Thai–who was highly regarded as a great ruler and scholar–ruling the city before ascending the throne as King Mahathammaracha I of Phra Ruang Dynasty (r. 1347–1368) (Andaya, Citation1971, pp. 61–65).

At present, with a population of almost 100,000, Si Satchanalai was the northernmost and the second largest administrative zone in Sukhothai province. Covering the area of 2,050 sq. km, the district is situated in a valley of the Yom River with Khao Luang Mountain Range lying westward along its north–south edge (Sukhothai Provincial Administration, Citation2007). With reference to the livelihood, agriculture and related agro-industries–e.g., refined sugar and ethyl alcohol–were the principal source of income whereas trades and commerce ranked the second, supplemented by tourism and service industry. While the growing of rice, sugarcane, corn, soybean, cotton, tobacco, banana, and orange remained the main enterprises, local communities in Si Satchanalai still preserved their cultural practices of cotton weaving and pottery making (Ibid).

Although Si Satchanalai consisted of 11 sub-districts, the participants of the 2018 KMITL- RCA fieldwork initially narrowed their scholarly efforts down to Nong O, Sarachit, and Dong Khu areas. The said selections stemmed from the fact that the 3 communities stood in proximity to the UNESCO World Heritage Site, and had been designated by the provincial administration as potential locations for promoting sustainable developments and creative tourism (Ibid). However, KMITL and RCA members eventually decided to concentrate all their research activities exclusively on Sarachit sub-district, citing ease of logistical management for the daily commute–in combination with safety concerns for transporting heavy equipment and oversized materials to the research sites–as the main reasons. Being a more urbanized settlement than Nong O and Dong Khu, Sarachit also offered better accommodations through its homestay service–an ethnographic form of hospitality–whereby the local residents acted as host families and occasionally as tour guides for the students.

Situated west of Si Satchanalai, Sarachit vividly exemplified a community where indigenous folktales and beliefs supplied a definitive shape and force in constructing a common identity of the local populace. Its culture was dominated by native folklore of Phra Ruang, based on the 14th-century manuscript known as “Traiphum Phra Ruang” (The 3 Realms of Cosmological Existence According to King Phra Ruang) (see: King Lithai, Citation1985). Being a mythical leader, Phra Ruang became synonymous with the names of many places and features in the sub-district through the stories of his supernatural powers and unrequited love.

Considering the demography of the participants of the 2018 fieldwork, the KMITL contingent consisted of six female plus four male undergraduate students, while four female and six male graduate students composed the RCA party. By resorting to the methods of focus group and self-selection, the partakers were divided into two teams, residing together with their host families in Si Satchanalai. Accompanying each team was five local teenagers–who were fairly proficient in English communication–voluntarily acting as their research assistants for the entire duration of the fieldwork. Corresponding online via the Internet and social media sites, such as Facebook since mid-2018, not only did the 10 KMITL and 10 RCA students became familiarized with each other, but also with their 10 local assistants prior to the commencement of the workshops and field trips in Thailand.

As stated before, in order to assess learning improvements and achievements, each KMITL and RCA member were assigned to keep an individual journal to record his/her learning experiences via various media and representational techniques, e.g., ink and pen drawings, pencil drawings, sketching, watercolors, models, photography, video, sound recordings, etc. Following the public seminar at BACC, the combined KMITL and RCA instructors subsequently evaluated the scholarly merits of the journals, based on their quality of presentation, details, and accuracy of documentation, as well as reflections on cross-cultural learning experiences. Emphasizing observing, recoding, analyzing, and learning the relationships among people, places, and built forms, these written reports aimed to explain how the built environment could affect human experiences, psyches, and perceptions (Suri, Citation2011).

5. The 2018 KMITL-RCA field-based research projects

5.1. Replica of Phra Ruang Kite at Baan Cook Pattana Village

During the second day of the fieldwork, the first group of students–comprising 5 KMITL and 5 RCA members–met the headwoman of Baan Cook Pattana village at the heart of Sarachit sub-district. The lady introduced them to the cultural learning center where local kites called Phra Ruang were made (). By perceiving this type of artifacts as their cultural heritage, the residents of Baan Cook Pattana had organized an annual festival where contests were held to see who could keep his/her kite in the air for the longest amount of time (also see: (Noobanjong & Louhapensang, Citation2017, p. 47; Noobanjong & Saengratwatchara, Citation2019, p. 12).

Owing to their fascination with Phra Ruang kites, the first KMITL-RCA team decided to study the geometry of these flying bodies (), which were modeled after those purportedly flown by the mythical leader. As a consequence, they assembled a twice life-size replica at a field nearby the Cultural Learning Center at Baan Cook Pattana village (), where the annual kite festival was usually held. Apart from performing as an object of inquiry for the KMITL and RCA students, the oversized model served a civic purpose as well. Its creation derived from a recommendation by representatives from Sarachit Sub-district Administrative Organization (SAO) for erecting a kind of advertisement billboards or signs to designate the location of the forthcoming kite festival to passersby in the area. For that reason, Sarachit SAO provided the KMITL-RCA team: 1) the main materials to build the gigantic replica of Phra Ruang kite–sisuk bamboo–which normally measured up to 10 m.-long with 15–20 cm.-diameters; and 2) a means of transportation in terms of pick-up trucks to carry the materials and commute to the construction site.

After their first visit to the Cultural Learning Center at Baan Cook Pattana village, the KMITL-RCA team began to look into the physical dimensions of Phra Ruang kites. A local kite master, Pruen Prangrit, voluntarily tough the students to assemble this particular kind of flying body. For the next 3 days, all members of the group laboriously engaged themselves in erecting a twice life-size Phra Ruang kite–of which overall width and height exceeded 10 m.–leaning against a 6 m.-tall bamboo scaffolding pedestal (). In doing so, the KMITL and RCA participants learned about the key qualities of sisuk bamboo–which were lightweight, resilient, flexible, inexpensive, locally available, and biodegradable–that endowed this wooden material with many promising possibilities.

In effect, the act of building twice life-size replica helped the KMTL and RCA students to formulate a basic conception about the geometry of Phra Ruang kites, as illustrated by their final works, featuring a series of 1) an analytical sketch on the geometrical compositions of a Phra Ruang kite informed by the theorem of Vesica Piscis in Euclid’s Elements (Heath, Citation1956, p. 241), displaying the ratios of formal relations among the components that constituted this tall and sturdy flying object in the shape of a 5 pointed-star () accompanied by; 2) scale drawings exhibiting the physical dimensions of the twice life-size replica of Phra Ruang kite erected by the KMITL-RCA team.

As shown by , a Phra Ruang kite contained 3 main components, which were: 1) the body (its shape of 5 pointed-star); 2) the bridle (or harness); 3 and the control line (or tether). Forming the kite body was a combination of framework and outer covering, created from a lightweight material like sisuk bamboo. Paper and fabric were then stretched over the framework, turning the body into a sort of wing, 5 of which comprise a single Phra Ruang kite (). In-flight, the kite was maneuvered by the pilot via a control line, which was attached to it by a bridle. The kite turned, ascended, and descended about the point where the bridle joined the control line ().

Although an allusion to the notion of Vesica Piscis (Ibid) could be seen as an intellectual framework for the KMITL-RCA inquiries at Baan Cook Pattana, their probes into Phra Ruang kites were far from being methodologically exhaustive. As a matter of fact, the proposed geometrical analyses of the kite () had yet to be authenticated by any verifiable means, such as trigonometric equations. Notwithstanding such deficiency, however, the studies on geometrical compositions of Phra Ruang kites by the KMITL-RCA students in 2018 pioneered into a largely uncharted research topic, thus opening the door of opportunity for additional investigations to follow.

Aside from the creation of the twice life-size replica, the knowledge, and skills obtained from kite master Pruen enabled some members of the KMITL-RCA team to assemble a small number of Phra Ruang kites, before taking them to the sky by themselves. The flight tests led to an impromptu inquiry that supplied a basic understanding on the aerodynamic principles of Phra Ruang kites. As noted by the students, the 4 forces of flight–i.e., lift, weight, drag, and thrust–affected their kites similarly to the ways that they behaved to airplanes ().

By alluding to Hulslander (Citation2012) (), it could be contended that the shape and angles of a Phra Ruang kite effectively directed air motions to generate a difference in air pressures to achieve lifting force (L). Since air pressure decreased while air speed accelerated, the velocity of the air above the kite was greater than the one below it. As the amount of pressure over its body became less than the pressure underneath, the kite was, therefore, pushed upward to the sky. Whereas the gravity created the force of weight (W) pulling the kite down to the ground, a forward force (F) propelling it into the direction of motion was provided by tension from the string and moving air created by the wind, or by a forward motion made by the pilot to produce thrust. On the contrary, the difference in air pressure between the front and back of the kite–in association with the friction of the air over its surfaces–gave the backward force of drag (D) moving in the opposite direction to motion. Accordingly, the KMITL-RCA team concluded that: 1) in order to launch a kite, lift must be greater than weight; and 2) if the kite were to hover in the air, then lift must be equal to weight and thrust must be equal to drag ().

Impressed by the aerial maneuverability of Phra Ruang kites, the KMITL and RCA participants hypothesized that such acrobatic agility stemmed from the overall perimeter of the 5 pointed-star shapes. When comparing with triangular, trapezoidal, and diamond shapes, a Phra Ruang kite embodied a higher number of contact areas–10 edges in total–permitting its pilot to readily apply external forces to achieve differences in air speeds and pressures, leading to faster turning, ascending, and descending movements ( and ). So, some KMITL and RCA members urged the Sarachit SAO to permanently keep the gigantic replica of a Phra Ruang kite, and use it as a medium to educate local high school students on the subjects of aerodynamics and Newton’s laws of motions.

5.2. Bamboo Bridge at Bang Khlang Village

Similar to their colleagues in Baan Cook Pattana village, the second KMITL-RCA team continued to explore the material qualities of sisuk bamboo. Yet, unlike the first group, they did not envision their research as a stand-alone entity, but an integral element of a community development project, which was still in progress of conception. After consulting with officials from Sarachit SAO, the students realized that there was a plan conceived by residents of Bang Khlang village to erect a 400 m.-long elevated bamboo walkway, linking a local road to a newly created scenic point with rolling hills at the backdrop (). As a result, the team proposed to build a small but crucial portion of the construction project: a 6 m.-long pedestrian bridge spanning across earthen dykes ().

Figure 9. A preliminary 3-dimensional computer graphic rendition of the Bamboo Bridge.Source: The authors, 2018

In contrast to the oversized Phra Ruang kite at Baan Cook Pattana, the causeway at Bang Khlang village did not stand at the heart of Sarachit, but dwelled on the border with Mueang Bang Khlang sub-district in the neighboring district of Sawankhalok. Floating over a vast lush-green rice field (), the causeway project was also co-sponsored by Sawankhalok municipal administration. According to the local legends, the site was among the places where Phra Ruang chased his lover Nang Kham to win her affection. By resorting to this method of a psychological connection, the creation of the elevated walkway would metaphorically become a physical manifestation of the bridge over Kaeng Luang stream, which was magically made by Phra Ruang out of thin air during his pursuit of Nang Kham (see: Designated Areas for Sustainable Tourism Administration (DASTA), Citation2014).

Due to a physical limitation of the RCA members to labor in the heat from the tropical sun in Thailand for longer than a couple of hours at a time, the entire walkway was initially conceived in terms of modular construction (). Each of the 6 m.-spanned bamboo modules would be built at various locations and then transported to the construction site at Bang Khlang Village before being put together. Nonetheless, this method proved to be prohibitively expensive and thus impractical in reality, since it would incur a large sum of expenditure for hiring heavy equipment–namely mobile cranes and flatbed trucks–to carry all pre-fabricated modules from the places of their creations.

Consequently, only the bamboo overpass () was pre-assembled and relocated to the construction area, whereas the rest was built on-site by local workers. On the one hand, while granting access to the scenic point, the causeway protected crops in the field from possible damages caused by visitors. On the other hand, by sitting on top of the dykes, the bridge provided an adequate ground clearance that permitted agricultural machines and equipment–such as tractors, harvesters, and chisel plows–to pass under it and then operates in the field without disrupting the flow of pedestrian traffics, reducing the risk of accidents and injuries that might occur to the sightseers and farmers alike.

With respect to the KMITL-RCA inquiries into the tectonic capabilities of sisuk bamboo, the students relied on the concept of funicular geometry (Kanaiya, Citation2013). Intuitively, a form of inverted catenary arch entered their minds, since it intrinsically possessed an ability to withstand the weight of the material from which it was created without collapsing () (Jefferson , Citation1830, p. 416). Additional research reaffirmed that inverted catenary arches were very strong because they redirected the vertical force of gravity into compression forces distributed along the curve of the arch. In a uniformly loaded catenary arch, the line of thrust ran through its center () (Nilsson, Citation2014, p. 24). For an arch of uniform density and thickness supporting only, its own weight–like the bamboo bridge at Bang Khlang village–the KMITL-RCA team discovered that the catenary was an ideal form ( and ), as evident from many historical precedents of bridge structures.

Figure 11. Conceptualization of the Bamboo Bridge at Bang Khlang by KMITL and RCA students. (a) Distributions of loads in the funicular geometry of a catenary arch. (b). A preliminary illustration of 3-Dimensional force distributions in the bridge.Source: Courtesy of Auroville Earth Institute, 2019.Source: The authors, 2019

By adopting the catenary arches as a prototype, the students then spent the next 3 days at their homestays to assemble a 1.2 m.-wide and 2 m.-tall pedestrian overpass–with a 6 m.-span–from sisuk bamboo. Due to the pliability and high tensile strength of this locally abundant natural material, the KMITL-RCA team was able to design such a curvilinear structure that was aesthetically pleasing and physically sturdy at the same time ( and ).

In any case, the abovementioned observations led to another important aspect of the KMITL-RCA field-based research project in Bang Khlang village, which was a firsthand knowledge on different bamboo joinery techniques, e.g., fastening, dowel-fastening, dowel-bolting, piercing, crisscross-fastening, and cross-lashing joints. While some participants felt that such a topic sounded mundane and uninspired at first, the fact that bamboo was hollow, tapered, and not perfectly circular–but contained nodes at varying distances–swiftly altered their unenthusiastic perception. On the first day of building the bridge, the students learned within few hours from local carpenters to appreciate that crafting decent bamboo connections was indeed a complicated and challenging task, demanding advanced levels of craftsmanship as much as an acute artistic sense of woodworkers ().

Be that as it may, a couple of clarifications and caution must be heeded. First, the catenary arches primarily served as a general reference for conceptualizing, rationalizing, and devising a simple funicular geometry of the bamboo bridge ( and (). Second, a series of corroborating studies on the physical integrity in association with mathematical calculations and analyses on the exact parametric dimensions of this pedestrian overpass had yet to be performed. So, the validity of the geometrical compositions, structural soundness, and design procedure of the bridge had still not been verified. Nevertheless, during the construction of the bamboo overpass, a group of 10–12 workers already walked on it for several hours, which was empirically indicative of its tectonic ability to withstand a substantial amount of external load without suffering any structural damage.

5.3. Mechanism and dynamism of cross-cultural interactions and learning through the KMITL-RCA field-based projects in Sarachit

By appropriating a theoretical stance from the discipline of anthropology, a remark could be made that both KMITL-RCA field-based research projects in Sarachit sub-district incorporated two ethnographic principles–known as the etic (outsider) and emic (insider)–in facilitating cross-cultural exchanges and learning (see Askland et al., Citation2014, pp. 285–287). As exhibited by the creations of the twice life-size replica of Phra Ruang kite () and catenary overpass (), whereas the RCA partakers played the etic role, their host families–along with the local laborers, assistants, and inhabitants–assumed the emic one. The KMITL participants, however, operated in both capacities at once. They performed an emic role by working in their home country. At the same time, these students enacted an etic role through the virtue of real-life education and onsite training occasioned by the 2018 fieldwork, which took place outside their everyday learning environment in the capital city (see Pavlides & Cranz, Citation2012, pp. 1–2). Buttressed by the aforementioned framework, the ways in which cross-cultural exchanges and learning functioned through the 2 KMITL-RCA field-based research projects could be described as the following.

5.3.1. The Replica of Phra Ruang Kite at Baan Cook Pattana Village

As stated by the personal journals of the KMITL-RCA team in Sarachit sub-district, the most profound cross-cultural encounters took place at Baan Cook Pattana village during the Phra Ruang kite workshop (). Similar to a typical Thai master craftsman, kite master Pruen employed neither writing nor drawing of a technical manual in training pupils. On the contrary, he relied on the methods of demonstration and face-to-face communication. Exercising a great amount of care and patience, Pruen methodically instructed the students to make those kites piece by piece, before asking them to assemble their own copies under his watchful eyes. Through trial and error, the KMITL-RCA team eventually learned to create Phra Ruang kites, but not without difficulty.

Apparently, Pruen’s method of teaching reflected an important aspect of Thai culture, which seemed to be verbally oriented where information and knowledge were disseminated via personal conversations, as opposed to the literary tradition in the Anglosphere. Yet, because the kite master was not proficient in English, whereas none of the RCA members could speak Thai, troubles in cross-cultural interactions naturally emerged. This was the moment when the KMITL students and local assistants came in to play a quintessential role as the mediators, who helped convey the flows of ideas, queries, and wisdom between Pruen and his British apprentices. In doing so, they simultaneously assumed dual duties of both enquirers and contributors, bring in their opinions, thoughts, and questions to the conversations. In consequence, albeit suffering from language and cultural barriers, all involving parties were able to communicate fairly well with one another, allowing them to build a horizon of understanding across nationalities, ethnicities, races, socio-economic standings, spiritual beliefs, and social practices.

In brief, the below explanations delineated the mechanism and dynamism of cross-cultural exchanges and learning incorporated by the kite workshop at Baan Cook Pattana.

Kite master Pruen delivered his knowledge and expertise to the KMITL-RCA team by means of focus group training.

In their endeavors to comprehend the geometry of Phra Ruang kites, the RCA members consulted the Western concept of Vesica Piscis in Euclid’s Elements ()–of which example was illustrated by an Italian architectural theorist Cesare Cesariano in 1521–and then collaborated with their KMITL partners to perform further analyses on the kites.

The KMITL students checked the accuracy of the findings with the local assistants and other Thai sources, before presenting them to the kite master and RCA colleagues in terms of sketches, drawings, and 3-dimensional visualizations () via their representational skills.

On the one hand, the Thais–including Pruen and the local assistants–picked up a systematic and scientific way of thinking on top of technological know-how and methodological approach to carry out a design-research project from their foreign counterparts. On the other hand, the Britons acquired a number of practical skills–ranging from graphics and handicraft to construction techniques and 3-dimensional conception–from working with as much as training by the indigenous people. By attending the workshop together, all participants had advanced their tacit knowledge on the artistic heritages of Si Satchanalai–particularly on the Phra Ruang kites–from cross-cultural encounters.

5.3.2. The Bamboo Bridge at Bang Khlang Village

A number of passages from personal journals of the students jointly testified that whereas the mechanism of cross-cultural exchanges and learning at Bang Khlang were almost identical to those at Baan Cook Pattana, the scale and scope of works in constructing the pedestrian overpass were substantially larger and more intricate, entailing a greater level of interactions with the villagers. While this KMITL-RCA team did not enjoy a preparatory workshop prior to the commencement of their research project, they received on-the-job training from local carpenters to familiarize themselves with different bamboo joinery techniques, as well as from native laborers to fathom the tectonic capabilities of sisuk bamboo (). Therefore, both the KMITL and RCA members were exposed to more diverse groups of the indigenous populace–such as rice farmers, street food venders, building contractors, and district officials–making the dynamism of their cross-cultural experiences far more complicated, sometimes less productive, and convivial, than those of the other group at Baan Cook Pattana village.

In sum, the manners in which cross-cultural exchanges and learning operated through the field-based research project at Bang Khlang were succinctly elaborated by these observations.

In searching for an optimal solution for devising the overpass, the RCA students alluded to the notion of funicular geometry–originally introduced in the 17th century by a French mathematician Pierre Varignon–to justify their use of an inverted catenary arch (). Afterward, they discussed with the Thai counterparts the practicality of employing funicular geometry along with the semicircular form in erecting the catenary bridge.

Following detailed investigations on historical precedents of bridge structures, the KMITL participants scrutinized the said British proposal. By exercising their 3-dimensional visualization skills, the Thai students generated a series of computer graphic renditions to examine a suitable design for the bamboo overpass ().

The KMITL-RCA team presented their ideas to the district officials, together with local building contractors and civil engineers, to finalize the design and secure a construction permit. With significant supports graciously provided by the local assistants, the construction drawings of the bamboo catenary bridge were made. Subsequently, the Thai and British students began working with the local laborers to assemble the bamboo overpass and elevated pedestrian causeway.

In advancing the tacit knowledge on the cultural heritages of Si Satchanalai, the KMITL students and local assistants, in particular, became an indispensable intermediary between the RCA members and denizens of Bang Khlang, which occasionally resulted in complicated situations due to differences in social and cultural practices. For example, since the Britons and Thais still adhered and conceptualized in their own units of measurement–the Imperial System for the former and the Thai anthropic unit for the latter (see: Measurements in Thailand, Citation2015)–specifying an exact dimension or distance necessitated a time-consuming process and extra efforts from everyone involved. Correspondingly, the KMITL students and local assistants agreed to serve as a kind of living converters, translating and standardizing all relevant data into the SI/metric units to ensure that their RCA colleagues could successfully communicate with the villagers and the other way around. On that account, it could be contended that the act of metrication functioned as a passage for building a horizon of cross-cultural understanding between the Thai and British citizens.

5.3.3. A combined lesson from the field-based research projects on cross-cultural learning

In tandem with examinations on the personal journals, field observations performed by the instructors from both universities recapitulated that the C&C approach used by the KMITL-RCA collaborative efforts in Si Satchanal fostered cross-cultural exchanges and learning–particularly between the Thai and British members–in the following manners.

First, as all participants attempted to establish a common ground in comprehending their objects of study, they frequently made references to artifacts and/or built forms in their own cultural heritages. To cite some obvious examples, whereas some RCA students equated the silhouette of Phra Ruang kites () to the outline of Christmas star ornaments, their KMITL counterparts compared it to the shape of a famous Thai kite, the 5 pointed-star Chula. In this respect, the KMITL-RCA examinations on the formal compositions of Phra Ruang kites evoked each person’s past encounters and recollections, leading to cross-cultural exchanges with his/her foreign colleagues via self-reflexive dialogues, comparative discussions, and visual articulations ().

Second, by reducing the visually complicated profile of Phra Ruang kites into a series of circular, triangular, and curvilinear shapes–regulated by right-angled lines–as demonstrated by its geometrical analyses (), the objects of inquiries were transformed to simplified graphic elements, which could be universally recognized by both KMITL and RCA partakers, transcending their cultural dissimilarities in applying the 5 pointed-star shapes to suit different kinds of artifacts.

Third, the catenary bridge presented a vivid illustration of the manners in which diverse techniques were employed to visualize this bamboo overpass. As mentioned earlier, on the one hand, with a preference for a quick and pragmatic way of representations, the artistically competent KMITL members usually relied on traditional hand-drawn sketches for probing into the funicular geometry of the bridge. On the other hand, with a penchant for precision and technical versatility, the technologically shrewd RCA participants developed a mathematical model of the bridge by using specialized computer software. Since every point in the surface of each component was assigned its coordinative values (based on the Cartesian grid system in the X-, Y-, and Z-axes), the exact dimensions of the overpass became quantifiable. Altogether, not only did these two representational techniques complement each other–resulting in cross-training between the Thai and foreign teammates–but also materialize the imaginary bridge from legends of Phra Ruang into reality ( and ).

Fourth, owing to the fact that the twice-life size replica of Phra Ruang kites () and pedestrian overpass () were massively built forms, the KMITL and RCA students exercised their haptic senses–concentrating on the bodily efforts in moving across space–to internalize the corporeal knowledge on the surroundings of the sites where those objects were erected. In effect, both field-based research projects used a comparatively identical mechanism in advancing cross-cultural learning. By means of comparative and self-reflexive discussions, a horizon of understanding between the Thai and British teammates was met, leading to exchanges of practical knowledge, ideas, and memories from experiencing, documenting, and rationalizing the tectonic capabilities of sisuk bamboo ().

Fifth, the inquiries on bamboo joinery provided a dialectical dialogue for cross-cultural interactions. Irrespective of a dichotomy of the Oriental versus Occidental discourses in the academic backgrounds of the KMITL and RCA students (see: Carrier, Citation1995; Said, Citation1978), observations from the fieldwork insisted that: 1) the training of the former was still influenced by traditional craftsmanship, emphasizing on the handmade-quality of designs; while 2) that of the latter embedded many traits of the Modernist principles in mastering machine tools for artistic creations/expressions. Be that as it may, the connecting details of the catenary bridge () resulted from an amalgamation of manual and mechanized skill sets, as shown by: 1) precisely-cut-and-drilled piercing joints; 2) properly aligned mortises and tenons; 3) firmly attached dowel-bolting connections; as well as 4) neatly made fastening, crisscross-fastening, and cross-lashing joints. In a nutshell, the bamboo joinery supplied a very flexible and sensible method for applying the C&C learning model to cultivate cross-cultural interactions via comparative discussions and visual articulations ().

Taken as a whole, although the research projects in Baan Cook Pattana and Bang Khlang villages ( and ) aimed to reciprocally benefit the participants from both universities, it appeared to be more discernable for the RCA members. In addition, instead of going through superficial and tourist-like activities as normally provided by another study abroad programs, the Britons became research partners and close associates of their Thai counterparts, and vice versa. Within a short period of 10 days, both parties depended on each other to work together in an unfamiliar and demanding environment. For that reason, a corollary argument could be put forward that not only did the two groups gain mutually from their cross-cultural exchanges, but also collected from the knowledge and insights exclusively available from the local people. In the increasingly globalized world of the 21st century, such experiences would be very advantageous for those soon to enter their career in architecture and design professions.

5.4. Tacit Knowledge on Si Satchanalai Gained by the KMITL and RCA Students

Examinations of personal journals submitted by the KMITL and RCA members disclosed that the students acquired a diverse body of tacit knowledge on the cultural heritages of Si Satchanalai, ranging from arts and architecture to theatrical performance and religious rites. The scholarly contents of their writings were synthesized from a series of accompanying inquiries to support the implementations of the two research projects in Baan Cook Pattana and Bang Khlang villages. Notwithstanding a score of thematic variations, all texts encompassed investigations on formations of collective identities in Sarachit sub-district through representations of space.

In this regard, a reference to the notion of topophilia (Tuan, Citation1974, p. 4)–denoting affective bonds between people and place or setting–bestowed a conceptual framework to comprehend the twice life-size replica of Phra Ruang kites () and catenary overpass ( and ) as the case studies on how the imaginary tales of Phra Ruang were manifested in the material culture of Sarachit via social practices of the native populace. As noticed by some students, these social-psychological relations endowed the villagers with a fil rouge that not only shaped their shared identity but also designated a tangible cultural inheritance in communities around Si Satchanalai district (see: Brewer & Gardner, Citation1996).

Accordingly, another reflexive comment could be articulated that the field-based research projects, in fact, illustrated the twin traversing trajectories in the poetics of representations by cultural heritages in Sarachit. On the one hand, the annual kite festival–symbolized by the KMITL-RCA oversized replica–bequeathed a temporal space that brought Phra Ruang kites from oral narratives to the material world. Likewise, by eliciting collective memories on the magical power of Phra Ruang, the elevated walkway and bamboo bridge connected the mental consciousness and bodily senses of the inhabitants together. On the other hand, the settings of the gigantic kite at Baan Cook Pattana () and pedestrian overpass at Baan Bang Khlang () provided the physical loci where the margins of tangible cultural heritages overlapped those of the intangible ones, from which human interactions happened.

Taken together, these analyses elucidated that the ties of localities and built forms with Phra Ruang mythologies were a modus operandi in experiencing a phenomenon of place in Sarachit (see: Relph, Citation1976, pp. 4–7) that constituted a quality of placeness (Ibid, p. 64), and sense of social belonging internalized by the dwellers of Baan Cook Pattana and Baan Bang Khlang villages (or habitus) (see: Bourdieu, Citation1990, p. 63). The attributes of persistent sameness and unity–enabling both communities to perceive themselves as different from those in other districts of Sukhothai province–were instrumental in fashioning a common self-image (see: Tajfel & Turner, Citation1986, pp. 7–24).

This mode of identity formation was reinforced by Phra Ruang folk stories that integrated descriptions of places and objects in Sarachit with historical narratives on the nearby archeological ruins in Si Satchanalai Historical Park. By means of such nomenclatural affiliations, the residents of Sarachit justified their claim on being descendants of Phra Ruang (or reincarnation thereof), despite the fact that sizeable portions of the present population–including those in Baan Cook Pattana and Baan Bang Khlang villages–were of ethnic Chinese and Phuan origins, whose ancestors migrated from southern China and Xiangkhoang province in Laos during the 1840s (Sukhothai Provincial Administration, Citation2007).

The abovementioned spatial-cum-temporal explications were semantically supported by the homonymic connotations of the word “Phra Ruang.” Aside from characterizing the cosmological manuscript and mythical leader, the term stood for the dynastic name of King Lithai’s lineage, which evolved into a generic name for all Sukhothai monarchs since King Sri Inthrathit (Khun Bang Klang Hao, r. 1238–1270) (Ahaina, Citation2017). As each sovereign assumed the same royal title, Phra Ruang then signified and unified every geographical area bearing its name–along with the related terminologies–as a geo-body (see: Winichakul, Citation1994, pp. 16–18), or vassal territory of the Sukhothai polity, as evident from the toponyms and names of built forms throughout Sarachit sub-district.

As a final point, due to the proximity of Sarachit to the UNESCO world heritage site, tourism had emerged as a powerful force behind the current poetics of representations by cultural heritages in Si Satchanalai. On that basis, some KMITL and RCA participants voiced their concerns that in order to draw more travelers to visit the sub-district and generate more incomes, all aspects of local culture were commercialized and turned into “cultural commodities” to be bought and sold (see: Appadurai, Citation1986, p. 3), as insinuated by the constructions of the gigantic kite at Baan Cook Pattana () and the catenary overpass at Baan Bang Khlang villages ().

In a similar vein of thinking, a pair of British and Thai students resonated that even though originating from the initiatives of the villagers, the oversized replica of Phra Ruang kites and bamboo bridge primarily existed as tourist attractions, rather than functioning as civic space to accommodate daily communal activities. Without sufficient awareness on a delicate balance of economic gain vis-a-vis cultural sensitivity by the local people, whether the increasing popularity in commodifying heritages would turn the Sarachit into a cultural theme park–littering with simulacra of historical built forms that were disharmonious and syncretic culminating in a kind of Disneytised environments–remained to be seen, they pondered (see: Baudrillard, Citation1983, pp. 1–2, Citation1994, p. 1).

6. Pedagogical efficacy of the C&C approach utilized by the 2018 KMITL-RCA fieldwork in cultivating cross-cultural exchanges and learning

As evident from , the field-based research projects at Baan Cook Pattana and Bang Khlang villages in Sarachit sub-district ( and ) incorporated various types of learning activities, which were visual articulation (VA), other types of haptic senses (OH), bodily experience (BE), literature review (LR), self-reflexive discussion (SD), and comparative discussion (CD). These classifications subsequently became the underlying conditions for each evaluative criterion of authentic assessments–experiences, information, and ideas, as well as reflexive dialogues–to measure the pedagogical efficacy of the C&C approach employed by the 2018 KMITL-RCA fieldwork in Si Satchanalai in cultivating cross-cultural exchanges and learning ().

In order to implement the authentic assessments, a group of 25 audiences from the public seminar at BACC in Bangkok courteously agreed to serve as a panel to conduct the authentic assessments on the efficacy of the C&C model used by the 2018 workshops and field trips in advancing cross-cultural learning and exchanges. As explained before, the reviewers encompassed: 1) a contingent of 5 KMTL and RCA faculty members whose scholarly expertise dwelled in architectural and design education; and 2) a collection of 20 college students from KMITL and other universities who attended the public seminar at BACC. In order to negate possible conflicts of interests that might manipulate the outcomes of the appraisals, merely 3 of the 25 referees from both categories actually participated in the KMITL-RCA collaborative efforts in Si Satchanalai.

Under an academic framework of peer reviews (or refereeing), the evaluations were carried out by utilizing worksheets/questionnaires to measure the satisfactory levels of the audiences with the KMITL-RCA field-based research projects at Baan Cook Pattana () and Bang Khlang villages () in bridging the gaps of knowledge, as well as in cultivating cross-cultural understanding via their authentic assessments–under the triad criteria of 1) experience; 2) information and ideas, and 3) reflexive dialogues–as demonstrated by and .

As indicated by and , in order to determine the levels of satisfaction of the audiences, a series of mean calculations and deviations were also exercised, utilizing a 5-point rating-scale question in which the weights assigned to each answer choice were presented in parentheses, as listed below:

Average 4.51–5.00 signified highest practice/satisfaction (Strongly Agree).

Average 3.51–4.00 signified high practice/satisfaction (Agree).

Average 2.51–3.00 signified medium practice/satisfaction (Neither Agree nor Disagree).

Average 1.51–2.00 signified low practice/satisfaction (Disagree).

Average 1.00–1.50 signified very low practice/satisfaction (Strongly Disagree).

In essence, the average satisfactory levels of the audiences–resulting from their authentic assessments on the KMITL-RCA field research projects exhibited at BACC–testified that the C&C method was very effective in promoting cross-cultural interactions and understanding between the KMITL and RCA participants ( and ). These positive outcomes reiterated that because the C&C method was comprehensively integrated with the learning activities–as epitomized by creations of the oversized replica of Phra Ruang kites () and the pedestrian overpass () in Sarachit sub-district of Si Satchanalai–it was very easy for the audiences to recognize and appreciate their pedagogical values in architectural and design education.

In order to accomplish a comprehensive evaluation on the pedagogical efficacy of the 2018 KMITL-RCA workshops and field trips, the analyses on methodological identifications ()–together with statistical results from the authentic assessments on the average satisfactory levels of the audiences at the public seminar ( and )–were further corroborated by the appraisals on the degrees of learning achievements attained by the KMITL and RCA participants ().

As stated before, at the end of the fieldwork in Si Satchanalai, the KMITL and RCA partakers were asked to review their scholarly improvements via a self-evaluated questionnaire containing 20 inquiries. The answers were categorized into the sextuple levels of knowledge (K), comprehension (C), application (Ap), analysis (An), synthesis (S), and evaluation (E), as identified by the Cognitive realm in Bloom’s learning taxonomies (B.S. Bloom, Citation1956, pp. 1–7) (). Afterward, a series of mean calculations were conducted on the returned questionnaires to gauge the extent of learning achievements acquired by the participants in 20 key areas, including critical and creative thinking capabilities, collaborative abilities, communication skills, as well as cross-cultural understanding ().

Regarding the details of the statistical investigations, the total number of involving students were 20, 10 of which came from KMITL and 10 from RCA (KMITL n = 10, RCA n = 10). Within this population group, a series of dependent sample t-tests were undertaken to create a content model, featuring comparative studies between the KMITL and RCA members in several areas. Next, the content model was substantiated by preference achievement tests, which not only verified the validity and reliability of the coefficient alpha of the questionnaires, but also those of the survey results in terms of Cronbach ‘s Alpha (see Cronbach, Citation1951). With coefficient reliability of 0.50, the evaluations on learning achievements resulting from the efficacy of the C&C approach in cross-cultural studies implemented by the 2018 KMITL-RCA workshops and excursions were displayed below ().

Through a series of the t-tests, examined the learning achievements of the KMITL and RCA students, displaying, t = 2.61, p = 0.013, d = 0.83, a large effect size. In general, the results disclosed that there was no discernable difference in attaining educational accomplishments between the Thai and foreign participants, In spite of their cultural and other dissimilarities. Apart from assessing the Cognitive realm of the population group from the lowest to highest orders, (from knowledge to evaluation) (), the statistical outcomes in indicated that the KMITL and RCA partakers alike had gained a higher degree of improvements in all aspects. Their most noticeable progress took place at the fundamental level–knowledge–trailing by the categories of comprehension, analysis, and evaluation. Likewise, decent development happened in the areas of synthesis and application as well.

On the whole, the t-test scores in collectively justified and reaffirmed that the 2018 KMITL-RCA fieldwork possessed remarkable pedagogical efficacy, enabling the students to advance their cross-cultural understanding through knowledge obtained from their cross-cultural learnings in Sarachit sub-districts (; Item: 1, 2, 3, 6&9). Moreover, both the KMITL and RCA participants were able to develop their critical and creative thinking skills (, Item: 12–15), facilitated by cross-cultural learning (; Item: 4, 5&16) through the methods of collaborations and cooperation (; Item: 2, 4, 16, 19&20) embedded in the field-based research projects in Si Satchanalai (; Item: 1, 7, 8, 10, 11, 18&20). In a nutshell, a concluding statement could be drawn that the 2018 workshops and field trips lent opportunities for the participating KMITL and RCA students to sharpen a number of important educational skills and abilities, which would benefit their academic and professional developments alike (; Item: 17–20).

7. Cross-examinations of findings from the quantitative studies by qualitative inquiries

As evidence from the statistical studies (), the success of cross-cultural learning ( and ) significantly depended on close collaboration and mutual cooperation between the KMITL and RCA students, both within and among each of the research teams. In other words, the realizations of the 2 field-based research projects at Baan Cook Pattana () and Baan Klung villages () could not be accomplished without the ability of the participants to communicate effectively with their foreign colleagues, who neither spoke the same language nor shared similar socio-cultural heritages. Therefore, in order to cultivate cross-cultural learning activities efficiently, foreign language proficiency became mandatory as a prerequisite skill (; Item: 3, 5, 7, 11&18).

On that account, reflections from the personal journals of the KMITL and RCA partakers revealed that neither parties were sufficiently prepared to overcome the language barrier, regardless of their best efforts to do so. Nevertheless, during the 10-day workshops and excursions in Si Satchanalai district, the students came up with a practical solution to alleviate troubles in verbal communication by exercising their visualization and illustration skills–notably by the methods of sketching and drawing–which were frequently utilized in lieu of conversations. These endeavors were fostered by the reality that all the 2 research projects in Sarachit sub-districts necessitated extensive reliance on visual articulations for their constructions ().