Abstract

The Actiotope Model of Giftedness (AMG) is one of the most promising models in the field of the nurture of the gifted. It addresses education of the gifted from a comprehensive perspective, unlike other unilateral models around the world. To the best of the researchers’ knowledge, not a single study has been conducted on this model in Arab countries. The current study sought to identify the reality of the nurture provided to gifted students in Sudan by surveying the historical beginnings and the current reality, and then reviewing this reality from the perspective of learning sources in the AMG. This review was based on examining documents and surveying the various aspects of this reality based on comprehensive systemic learning resources. The study examined exogenous and endogenous learning sources and clarified the limitations in each. It was recommended that great effort be exerted by the state, its institutions, and the whole of society to promote education of gifted students in Sudan.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Educating the gifted and talented is an educational issue of great importance. Countries seeking progress place much emphasis on this type of education. To know about gifted education in non-western countries, we conducted this study in Sudan, which is an African Arab country.

In this study we explored the reality of the nurture provided to gifted Sudanese students by surveying its historical beginnings and current reality since 2019, and reviewing this reality from the learning resources perspective of the Actiotope Model of Giftedness (AMG). This review was done by surveying and extrapolating the various aspects of this reality from the perspective of comprehensive systemic learning resources.

The study revealed bright aspects in the Sudanese experience of nurturing the gifted and talented. It nonetheless revealed a need for very great effort on the part of the state, its institutions and society as a whole to improve gifted education in Sudan.

author statement

1. Introduction

Over more than a century, education of the gifted has experienced many developments, as the field distanced itself from the prevailing concepts that follow myths, theology and metaphysics. Initially, giftedness and excellence were conceived of from a unilateral perspective, i.e., the individual gifted with exceptional mental and creative abilities. For this reason, models focusing on giftedness and talent on an individual basis have long prevailed (Gagné, Citation2003; Gardner, Citation1994; Maker, Citation1992; Moenks, Citation1992; Renzulli, Citation1986; Sternberg, Citation2003; Tannenbaum, Citation1983). There were many theories explaining giftedness in this direction (Belsky & Pleuss, Citation2009; Dabrowski, Citation1964; Rogers & Silverman, Citation1997; Silverman, Citation1993) and identification models emerged (Pfeiffer, Citation2013). Theories have advanced a little in understanding the complex phenomenon of giftedness by adding other elements beyond absolute individualism, e.g., Clark (Citation1982), Csikszentmihalyi and Csikszentmihalyi (Citation1993), and Winner (Citation2000), who suggested that giftedness and talent are the outcome of a rich learning environment, extensive training, over-ambitious parents, and high expectations.

A more comprehensive perspective of the systems surrounding giftedness emerged when Ziegler (Citation2004) presented the Actiotope Model based on the systems theory. According to this model, continuous exchange occurs between the gifted person, his or her actions and the environment in which the individual develops (Ziegler et al., Citation2018). This model reflects the complex and dynamic nature of the giftedness process in contrast to the linear approaches that look to either the individual alone or the environment per se (Sarouphim, Citation2012). Proponents of this model believe that giftedness and excellence are not just personal traits. The AMG refutes the previous prevailing view about the traits of the gifted person and rather focuses on shaping the learning of the individual that leads to excellence. Giftedness, according to this model, is subject to self-regulation and adaptation of a highly complex system. The AMG model is based on interaction and adaptation in the biotope system that includes the environment and the individual, the Actiotope. There are 11 sets of learning goals in the AMG, four of which relate to the components of the Actiotope, five to adaptability to the Actiotope and two to the Actiotope as a system. The focus is on understanding the interactions and actions of the various individual and environmental components of the system and its pathways (Ziegler & Phillipson, Citation2012a). The model focuses on actions (Stoeger & Ziegler, Citation2005) and development of excellence in individual triggers in the context of adaptation and regulation (Ziegler & Baker, Citation2013). Schic (Citation2008) believes that the AMG is a prime example of “conceptual reactivation” in the field of giftedness and that it informs research, development and mentorship of the gifted.He (or She, whichever is appropriate) elaborates that it is necessary to take advantage of this systemic perspective to understand the structural relationships of giftedness.

This model resulted in the systemic theory of gifted education (Ziegler & Phillipson, Citation2012a, Citation2012b) and the learning resources-oriented approach to gifted education (Ziegler et al., Citation2017, Citation2019) which provides comprehensive categorization of learning resources that include five exogenous learning resources (cultural educational capital, economic educational capital, social educational capital, infrastructural educational capital and didactic educational capital), and five endogenous educational resources (actional learning capital, organismic learning capital, telic learning capital, episodical learning capital and attentional learning capital).

The significance of the AMG with its learning resources has been supported by several studies. Lafferty et al. (Citation2020) dealt with educational resources and social gender norms by examining the AMG and social gender norms on achievement. Vladut et al. (Citation2015) presented empirical evidence for the association between the Actiotope and learning resources through the Educational and Learning Capital (QELC) questionnaire. The study revealed a procedural link between the Actiotope variables and learning resources. The QELC was found to have satisfactory psychometric characteristics and acceptable factorial and concurrent validity. In the study by Mudrak et al. (Citation2020), the psychological structures of learning potentials and the systematic approach to the development of excellence were discussed. A systematic framework was presented to develop learning potentials for professional excellence inspired in the Actiotope model. The study also presented procedural strategies for teachers of gifted students to employ learning resources in the Education of the Gifted (Vladut et al., Citation2016).

The effectiveness of the AMG has been supported in Western and Eastern cultures beyond Germany, its country of origin. It has had support on the continent of Asia (Vialle & Ziegler, Citation2016), in Canada and the Czech Republic (Ziegler et al., Citation2014), East Asian countries (Mcinerney, Citation2013; Neubauer, Citation2013; Stoeger, Citation2013), Turkey and China (Vladut et al., Citation2013), Australia (Vialle, Citation2017), China (Callngham, Citation2013; Pang, Citation2012), and Turkey (Leana-Taşcılar, Citation2014, Citation2015a, Citation2015b, Citation2015c).

In this study we seek to identify the reality of the nurture provided to gifted Sudanese students by surveying its historical beginnings and current reality, and reviewing this reality from the learning resources perspective of the AMG. This review was made by surveying and extrapolating the various aspects of this reality from the perspective of comprehensive systemic learning resources.

Sudan, the subject of the current study, is an Arab African country in northeastern Africa. With an area of approximately 1,886,068 square kilometers, it is the third largest of the Arab countries extending across Asia and Africa. It lies along the crossroads south of the Sahara Desert and along the Red Sea on its northern eastern border. Sudan shares borders with seven countries and consists mainly of flat plains interspersed with mountain ranges. It has a variety of climates across its vast area and many rivers cross it. Among them are the Blue and White Niles that unite in Khartoum, the capital of Sudan to form the Nile River. Although it is an enormous country, Sudan is sparsely populated with an estimated population of 43 million people (2018 estimate), most of whom are rural. Sudan is rich in different races and cultures and a mixture of Arab and African tribes.

2. The beginnings: A historical overview of Sudan before the formation of systems for nurture of the gifted (…—2004)

Historical evidence reveals educational interest in the gifted and talented dating back to early in Sudanese history. Specialists point to indications found in the traditional educational system that such interest began with the establishment hundreds of years ago in Sudan of Al-Khalawa, a small school teaching the Holy Quran and the principles of the Arabic language. Al-Khalawa first appeared in the Funj Sultanate during the rule of Sheikh Ajib Al-Manjalk (1570–1611) and is said to have appeared before that time, but it is proven only that it expanded during his reign. The sheikh of Khalwa allowed high achievers to progress in memorization without being restricted by their class, which is a kind of academic acceleration. High achievers in memorization were also encouraged by various material and spiritual reinforcements (Bakhiet, Citation2005).

After the emergence of modern education in Sudan, some Sudanese educators were interested in the idea of giftedness and talent, so they called for taking care of the gifted and educating them according to scientific foundations. Searching for the oldest published Sudanese documents, we found that Abu Al-Qasim Badri wrote in 1953—three years before Sudan independence, an article on brilliance and genius and their importance in nation building (Bakhiet, Citation2008c). Furthermore, Osman (Citation1970) wrote an article on gifted children and Abdel Mageed (Citation1975) wrote one on educating the gifted in the Republic of Sudan. However, these calls did not find any application and remained confined to scientific journals.

Others believe that the three national high schools established during British colonialism provided a group of outstanding male students (Abdelazim, Citation2005). These schools were Wadi Saydna High School, established in 1938 in Omdurman; Hantoub School, established in 1946 in Al-Jazirah state, and Khor Taqat Secondary School, established in 1950 in North Kordofan state. Students at these schools were sorted into four levels according to academic performance through a system known as the Sets System. This meant grouping students according to their academic excellence in different subjects. The groups were distributed in classes, for example, “Set1”, “Set 2”, “Set 3”, “Set 4”. The first group “Set1” included outstanding students, “Set2” included fewer superior students, etc. The criterion of division in the “Sets” system was high academic achievement (Abdelazim, Citation2015). Students who were gifted in arts received special care (Fadl, Citation2006). Those schools were closed in 1992.

When secondary education expanded in Sudan, the state established a model school in 1982 in Khor Omar in Omdurman to which only outstanding middle school students were admitted. However, that school had no additional programs. It only grouped the academically outstanding students in one school where students studied the same subjects and were taught by teachers with the same qualifications as teachers in other schools, although distinguished teachers were also chosen to work in it. That school continued until the last cohort graduated in 1994 (Soliman, Citation1996).

Psychologists also had an important role in preaching the issue of nurturing the gifted. Omar Haroun Khaleefa established the Sudanese Association for Gifted Children in the late eighties of the last century. It was formed at the University of Khartoum from those interested and eager to nurture the gifted and it was under the auspices of Mahjoub Al-Badawi, Minister of Education at the time. The association formulated ambitious goals: defining the gifted and talented, developing scientific tools to identify the gifted, urging educational leaders to take care of them, and raising the issue for public opinion to support it (Mohammed, Citation2006). Then Khakeefa (Citation1989a, Citation1989b) conducted several case studies on the high achievers in national and international exams and published a number of newspaper articles under the title “Save My Country’s Gifted Children”.

The Sudanese Constitution of 1990 explicitly stipulated concern and care for the gifted (Kassab, Citation2006) and one of the goals of The Comprehensive National Strategy 1992–2002 was to take care of gifted children and secure appropriate conditions for development of their abilities and creativity. Thus, the idea of establishing model secondary schools for gifted and brilliant students emerged again. The idea was adopted and implemented in the state of Khartoum by Muhammad Al-Sheikh Madani, Minister of Education. Accordingly, 37 schools were established to group academic high achievers until 2010 in the state of Khartoum. The only criterion for admission in those schools was academic excellence, and other criteria for admission were neglected. That experiment adopted none of the well-known educational systems of gifted education. Furthermore, there was no curriculum designed specifically to maximize the potential of the gifted. Likewise, schools did not seek out teachers specialized in this type of education. The most important thing that those schools lacked was the presence of psychological care services geared toward the gifted. In other words, as with previous experiences in Sudan, those schools just grouped gifted students. But this does not negate the importance of that experience in the development of gifted education in Sudan. Those special schools admitted both males and females, whereas the previous experiences were restricted to males. The schools also provided a real competitive environment for students with similar mental abilities and established a physical environment that was more suitable for them compared to public schools.

The Quarter-Century Strategy in the Republic of Sudan 2002–2027 came into being without any reference to the gifted, although among its policies was the recommendation that attention be paid to special categories that implicitly include the gifted. Furthermore, the Public Education Planning and Organizing Law (Citation2001) did not explicitly refer to the gifted, but paragraph (e) of Article (5) in the second chapter referred to encouraging creativity and developing competencies and skills. The Committee of The Second National Conference on Education Policies (Citation2002) recommended that special groups, including the gifted, be accommodated and that an office be founded for them in the Federal Ministry within the Department of Educational Planning.

Observations up to 2003 indicate that there were a number of manifestations of interest in the gifted in the Republic of Sudan. These included the establishment of the Scientific Creativity Care Authority, the allocation of an award to scientists and innovators bearing the name of the martyr Al-Zubair Muhammad Salih, and great interest in honoring and awarding students with outstanding achievement in final exams in all educational stages. There is a department in the Ministry of Science and Technology for honoring brilliant students. Honoring academic excellence has become a tradition in most states and provinces.

Our researchers also noted some weaknesses in the Sudanese experience. First, most interest was placed on encouraging the gifted to the neglect of other important aspects of nurture. Second, there was no clear legislation for the gifted. Third, there were no programs to identify the gifted, nor were there strong educational programs, quantitatively or qualitatively, for the gifted. Fourth, universities and civil society organizations played no role in the giftedness issue. Fifth and finally, the early enlightened movement (the appeals of educators and psychologists) could not transform into an effective and influential pressure group of decision makers as happened in developed countries where academics played a significant role in making their countries adopt the issue. One of the most noticeable aspects of weakness in the Sudanese experience at that time was that it focused on secondary school students with no consideration of the opinions of experts who stressed that nurture of the gifted must begin at an early age. All these shortcomings combined to lead Sudan to lag in this field compared to other Arab countries, not to mention the developed countries. This impeded Sudan’s achievement of many of the gains of gifted nurture programs, which undoubtedly wasted a lot of mental wealth.

The previously mentioned manifestations of weakness were within the official efforts of the state. As for research, the efforts of individual researchers were limited to master’s theses and doctoral dissertations and a few published articles. The researchers’ interest was limited to studying specific mental components of giftedness such as intelligence, creative thinking, or academic excellence, each on its own. The different types of giftedness were not studied and most studies were concerned with studying the relationship of these components to some psychological, social and demographic variables. Despite these delimitations, those studies enriched the scientific arena and made valuable contributions. One early study in the field of intelligence was done by Hanin (Citation1979) who established the validity of the High Intelligence Scale in the Sudanese environment. Subsequent attempts were made to adapt some international measures of intelligence to the Sudanese environment, e.g., Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (Khakeefa, Citation1987) and Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (Hussein, Citation1988). Bashir (Citation1993) developed Sudanese versions of the Stanford-Binet Scale, Abdel Rahman (Citation1997) conducted a study on the Henmone-Nelsone scale, Badri (Citation1966, Citation1997b) tested the Columbia Mental Maturity Scale (CMMS), Al-Khatib and Al- Mutawakel (Citation1998) standardized the Standard Progressive Matrices Test (SPM), and Hussain (Citation2004) validated the Otes and Lennon scale for preschool children. In general, there has been richness and diversity in research exploring intelligence and adaptation and standardization of its measures. Intelligence is an important component of intellectual giftedness and tools for measuring it are a major part of the battery for identifying the intellectually gifted.

As for practices to benefit from the study of intelligence in education, Sudan could have achieved a global precedent in this field, as Galton, the pioneer of mental measurement in the world, visited Sudan twice in 1845 and 1846 (Jarwan, Citation1999). But researchers did not obtain information about those two visits and the scientific contribution they offered. Perhaps it was Sudan’s misfortune that Galton visited it before his attempts to measure intelligence, calculate the correlation coefficient, study genius and establish the human measurement laboratory. Work in this field was delayed for a whole century and was resumed at the hands of Scott (Citation1946, Citation1948, Citation1950), another British researcher. His studies actually began in 1944 when he was an educator and then director of Gordon Memorial College. He worked under the supervision of the famous British psychologist Vernon and his study really enriched the field. The National Center for Educational Research attempted to evaluate Scott’s test in 1978 and 1979 and a version of this scale was published by Salman (Citation2000). In the same context, the Egyptian psychologist Mustafa Fahmy (Citation1954) conducted a study on the children of the Shilluk tribe in southern Sudan in order to measure their intelligence and use the results in planning appropriate educational policies for them (Fahmy, Citation1965; Fahmy & Ibrahim, Citation1954). In 1965, Badri conducted a study to validate the Goodenough Draw-a-Man Test for Sudanese children. One of the most important attempts was the study in the field of giftedness gift done by Lowenstein in 1981when he was a visiting professor at the Faculty of Education, Khartoum University. He applied the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for intelligence (WISC-R) as a criterion to compare the nominations of Sudanese and British teachers in the identification of gifted children (Bakhiet, Citation2009b).

As for creative thinking, an important component of giftedness, five attempts were made to validate measures for the Sudanese environment. Al-Hadi (Citation1981) validated the Torrance Scale for Creative Thinking (form B). B. Ibrahim (Citation1987) validated Abd Asasalam Abd Al-Ghaffar’s Scale of Creativity, Baldo (Citation1993) validated Sayed Khairallah’s Scale, Al-nail (Citation2000) validated the scale translated in Egypt by Sana Muhammad Nasr, and A. Ali (Citation2002) validated the Guilford Battery.

In the field of academic excellence, Soliman (Citation1996) conducted a study to discover the factors contributing to academic excellence. Algack (Citation1998) conducted a study in which she showed the importance of educational care for academically outstanding students at the basic stage. Researchers in psychology and in education have jointly studied this aspect of the intellectual giftedness, which led to integration between different sciences in the investigation of cognitive aspects.

In 2003, Sudan initiated some practical scientific efforts to nurture the gifted after Dr. Omar Haroun Khaleefa, a university professor and expert in the nurture of the gifted and the representative of the International Council for Gifted and Talented Children in Sudan, returned from his work in the State of Bahrain. The beginning was at Al-Qabas schools under Dr. Khaleefa, the founder of the Simber Project to identify the gifted. There, the first program based on scientific foundations for the nurture of the gifted was implemented. Achievements of that program included training workshops for teachers and psychological counselors on giftedness, awareness and family guidance, counseling the gifted, identification of a large number of gifted students with reputable scientific methods and tools, and school enrichment programs. Courses of thinking skills were introduced for the first time in schools and summer camps. Specialists gained membership in Arab and international councils on giftedness and excellence and many of them participated in seminars, festivals and conferences. Scientific research was not neglected in that program and researchers were supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology. That program resonated with the Ministry of Education in Khartoum State that seriously began implementing scientific programs to nurture the gifted in its schools. In January, 2003, the Council of Ministers issued Resolution No. 159 assigning a committee to study education of the gifted. The Ministry of Education in Khartoum State hired Dr. Omar Haroun Khaleefa and convened several workshops and seminars among experts to study gifted education in a serious scientific manner. The most important of those workshops were those held in April, 2004, for supervisors in the Ministry of Education on nurture of the gifted. Another influential workshop, held for leaders and intermediate cadres at the Ministry of Education, dealt with the project of initiating schools for the gifted in Sudan.

3. Governmental interest in the nurture of the gifted (2005–2019)

A panel discussion was held on 4 December 2004in the Hall of the Martyr Al-Zubair Muhammad Salih in which a specialized group of working papers prepared by educational experts were presented. Based on the decision of the Minister of Education in Khartoum State and the recommendations of the panel discussion, a technical committee was formed to manage a project through which three schools were selected in the state of Khartoum in the three major cities of Khartoum, Khartoum North, and Omdurman as headquarters of the gifted schools in Sudan for the basic stage. Admission to those schools began with fourth graders and study ended with the eighth graders. Later three secondary schools were established where graduates of the eighth grade could complete three more years, up to the eleventh grade, to match the 11-grade educational system in Sudan.

The National Curriculum Center prepared and enriched the curricula of the fourth, fifth, and sixth grades in the gifted school by expanding the Arabic language and mathematics requirements and enriching the science curriculum. New subjects have since been added to the general curriculum: computer science, robotics, the English language, thinking skills, and arts. To evaluate the experience, workshops were held periodically, the first of which was held on 22 March 2005 it was attended by university professors to evaluate these enrichment curricula (Gifted Administration, Citation2006). In other words, it is noticed that an enrichment curriculum was added to the general curriculum and new study materials were added that met the unique needs of the gifted children. The National Center for Curricula and Books in consultation with the project’s technical committee and other experts developed the curricula for those schools.

As for teaching, 60 teachers with bachelor degrees and at least three years of experience, among other personal characteristics, were selected to teach at those schools. The selected teachers received 170 hours of intensive training on 14 May 2005. The trainer was Dr. Fathi Jarwan, President of the Arab Council for the Gifted and the first Arab expert in educating and nurturing the gifted (Gifted Administration, Citation2006). On 12 May 2007an intensive training workshop of 105 hours was held. It included topics in psychological counseling, the theory of successful intelligence, enriching the curricula of the gifted, and methods of teaching and evaluating the gifted. Dr. Fathi Jarwan and Dr. Mahmoud Muhammed Ali Abu Jado did the training (Gifted Administration, Citation2006).

The Sudanese experience culminated in the establishment of the National Authority for the Nurture of Gifted Children in 2006 by Decree No. 221 of 2006 issued by the President of the Republic on 8 June 2006. The authority was sponsored by the President of the Republic and headed by Professor Al-Zubair Bashir Taha. Its board of directors included an elite group of specialists in the field in addition to national figures. According to this decision, privileges and allocations were granted to the authority with partial rehabilitation of gifted schools. The authority was run for a long time by Maryam Hassan Omar, the strongest advocate of the idea since its inception in the ministry.

New branches of gifted schools were later opened in Madani, Gezira State (a joint basic school- a joint secondary school); El-Gadarif State (a joint basic school—a joint secondary school), and River Nile State—Abu Hamad—(one joint basic school). Thus, the number of gifted schools in all Sudanese states totaled 11 schools. The presence of these schools encouraged research in the field. Dosa (Citation2007) conducted a study to identify gifted students in the city of Nyala in Darfur, western Sudan. Al-Jamri (Citation2012) explored the role that art education plays in giftedness in Shendi in River Nile State, she found differences in academic achievement between students with high art abilities, and those with lower art abilities in favor of those with high art abilities, as well as she found differences between gifted group in favor of gifted girls. Haj-Adam (Citation2020) conducted a study to identify gifted students in the state of El-Gadarif.

That period also witnessed several developments in research supporting the nurture of the gifted, as some important measures were standardized for the identification of the gifted, e.g., WISC-III (Al-Hussein, Citation2008, Citation2005; Bakhiet, Citation2014; Bakhiet et al., Citation2014), the Colored Progressive Matrices Test for Children’s Intelligence (CPM; Abdal-Rahim & Al-khatib, Citation2009; Al-Khatib et al., Citation2021, Citation2006; Bakhiet, Citation2009a), the Standard Progressive Matrices Test (SPM; Bakhiet et al., Citation2007), a version of the Standard Progressive Matrices Test standardized according to Rasch Model (Bakhiet, Citation2012), the Standard Progressive Matrices Revised test (SPM+; Husain et al., Citation2019), My Classroom Activities Scale to assess the effectiveness of what is provided to the gifted in their classrooms (Bakhiet, Citation2015; Mohammed et al., Citation2018; Pereira et al., Citation2017), and the Characteristics of Giftedness Scale (Bakhiet, Citation2013, Citation2008a). Furthermore, new methods were developed to process data of the identification of the gifted (Bakhiet, Citation2008b), comparing various methods of giftedness identification (Murad, Citation2019), and training teachers of gifted students on methods of processing data of giftedness identification. Studies were also conducted to improve teachers’ attitudes towards the process of identifying gifted students (e.g., Bakhiet & Al-Hassan, Citation2014).

4. Analyzing the reality of the nurture of the gifted according to exogenous and endogenous educational sources

4.1. First: exogenous educational resources

4.1.1. Economic educational capital

This aspect deals with how education of the gifted is supported financially and logistically. We found that funding was provided from the development budget of the Ministry of Education, Khartoum State and currently from the development money of the Federal Ministry of Education. This reveals a weakness in funding sources. A high percentage of funds comes from the Educational Council for Schools and philanthropists. The authority also obtains funds from the Ministry of Finance and activities are funded with contributions of the educational council.

In terms of families, we found that parents of many gifted students supported their children financially to obtain training courses in the areas of electronic self-learning skills, cognitive development and skill, and applied and innovative outcomes. There is a follow-up and effective partnership of parents and the Educational Council that provides breakfast for needy students and orphans. Parents partially pay for the transportation of basic school students and fully pay for the transportation of secondary school students, and some students travel by public transportation.

There are interactive educational, social and sports activities and school trips, as well as personality-building and enrichment programs. There is evidence that until 2018 there were local and international partnerships and foreign visits to learn about the experiences of other countries such as Jordan, China, Saudi Arabia and Iraq. Furthermore, there are innovative works and activities, an exhibition for students, libraries, cafeterias, gardens, theaters, classes, science, language and computer labs, smart games, and an activity hall with equipment and sports games.

The schools are characterized by the presence of distinguished administrative competencies, sufficient classrooms and availability of various laboratory capabilities. The schools provide teachers with training on using modern technologies. However, Ahmed and Bakhiet (Citation2021) reported weakness and lack of available information and communication technology in gifted schools. Therefore, H. Ali (Citation2020) presented the interactive education experience and the use of open-source e-learning systems to address the problems of gifted schools in Sudan.

Until 2019, ten camps held at the Authority for the Gifted were attended by experienced trainers in the fields of creativity and development. They included workshops on drawing, designing and technologies up to the fourth-generation. Recently, Sudan joined the Smart Africa Alliance, which includes 31 African countries and an international body interested in technology in 2021.

5. Cultural educational capital

This aspect pertains to the public view of the gifted, how peers view giftedness. what the basic concept of giftedness is, what gifts are valuable, and how gifts are developed in schools and other contexts.

No adequate studies have been conducted on these aspects, but observations indicate that there are positive societal attitudes towards gifted and talented persons. The academic concept of gift prevails in general. There are good efforts to develop gifts. Al-Jamri (Citation2012) reported a positive effect of art education on the performance in other academic subjects of gifted students in secondary schools. Students with high artistic abilities outperformed their counterparts with lower artistic abilities in academic achievement.

There is also interest in courses on thinking skills, e.g., Al-Taher (Citation2014) examined the effectiveness of the CORT program in developing creative thinking and intelligence among outstanding second graders of the secondary school in Khartoum State. The program proved to have positive effects on the study participants.

6. Social educational capital

This aspect concerns people involved in the promotion of gifted children: parents, teachers and supervisors. It also pertains to whether there is a need for more personnel and whether there are support groups such as parents’ associations.

All teachers working in gifted and excellence schools are appointed by the Ministry of Education in Khartoum State. Some of them are c-ooperators, especially teachers in the technical field. Teachers are selected based on an academic exam and a personal interview.

Teachers in these schools are characterized by a low degree of psychological burnout (Bakhiet & Al-Hassan, Citation2011). Alshaer (Citation2011) revealed that the IQ of gifted students on the Standard Sequential Matrix Scale was 112.35 according to the Greenwich Standard, while the teachers’ intelligence was 90.18. Al-Rasheed (Citation2010) revealed that the emotional intelligence of teachers and students was high. No differences in emotional intelligence were found by gender, age, marital status, region of origin or years of experience.

Another important societal aspect in caring for the gifted is the existence of legislation and regulations. So far there is no evidence in the authority of approved laws and regulations. What exists is just a proposal that was formulated in 2017–2018. There are no clear policies or organizational structure for gifted schools. Also, there are no work regulations. Recently, the Governance and Administration Sector in the Council of Ministers approved the draft law of the National Authority for the Nurture of the Gifted-on 4 April 2018.

7. Infrastructural educational capital

This dimension relates to the existence of special infrastructures that gifted individuals can use: special schools, internet resources, libraries, support centers and universities (Ziegler, Citation2021).

We found that the funds come from the development budget from the Ministry of Education, Khartoum State and are currently from the development money of the Federal Ministry of Education. This is why funds are not sufficient. A high percentage of the monies come from the Educational Council for Schools and from philanthropists.

Basic schools for the gifted were situated in public schools that had been rehabilitated to suit the gifted, but they are ineffective according to some knowledgeable people. Among other deficiencies they lack protection and safety. Secondary schools have been established in rented buildings (Report of the Giftedness and Excellence Schools Evaluation Committee, Citation2021).

8. Didactic educational capital

This dimension is concerned with the presence of sufficient knowledge in the country about how to support gifted students in regular classes and in private educational institutions. It is also considering the quality of teacher training and availability of special curricula.

Abdelazim (Citation2015) revealed that the curricula of the gifted are to a large extent in agreement with national quality standards. Similarly, Aldood and Abu Al-qasim (Citation2020) evaluated gifted education programs in the state of Khartoum from the perspective of teachers. Results revealed that gifted programs in Sudan meet international special education standards.

8.1. Second: Endogenous educational resources

8.1.1. Action learning capital

This dimension relates to the success of gifted education in the country, students’ performance in international educational studies (PISA, TIMS, etc.), students’ winning international competitions or awards, and gifted students’ realization of their full potential.

Sudan did not participate in international educational studies (PISA, TIMS, PIRLS) and other international competitions, nor did the country’s gifted schools. However, Sudanese students participated in other important fields, such as the World Robot Championship in Washington in 2016 and the World Robot Championship in Dubai and won three out of 20 cups for all competitors from all over the world. They also participated in the Robot online Challenge 2020, the fourth Qatar Schools Debating Championship 2018, and in the United Nations Girls Camp in Uganda to support women and equality issues. One important achievement is the selection of one of the school’s graduates among five international students worldwide for the Microsoft Scholarship for Artificial Intelligence, who was later hired by Google as a researcher in the field of artificial intelligence. Furthermore, one of (Is this the same school as above? If not, to what does “its” refer?) its students won the first position in a programming competition for African university students in 2020 and the sixth position globally. Some students presented entrepreneurial project models that were adopted by such large companies as Tenlog for Intelligent Systems, Monjid Services Application, A Device for Assisting Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis, and First Global Artificial Intelligence Training Center.

Every student in these schools is able from fifth grade to manufacture a robot. A study by A. Ibrahim (Citation2008) supported the advantages of academic acceleration for the mentally gifted and academically high-achieving students in gifted schools and in regular schools. The results showed that academic acceleration for gifted students contributes to the development of their social, emotional and cognitive characteristics. Wasila (Citation2015) revealed that the biology course developed the creative thinking of gifted students and their general academic achievement. UWC Sudan gives gifted students the opportunity to pursue their education at one of the 18 UWC schools around the world.

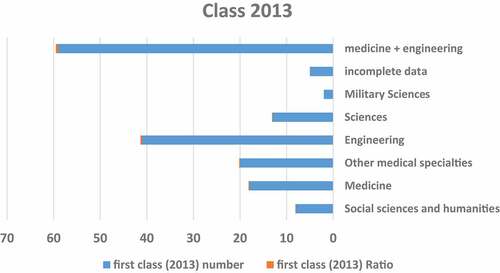

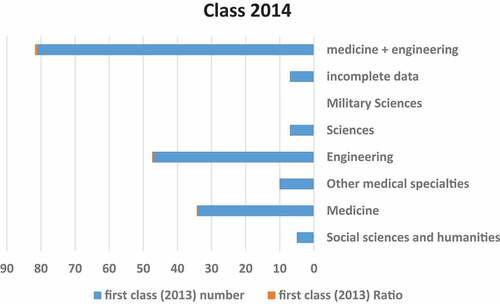

A study followed student cohorts between 2013 and 2014 (i.e., the first and the second cohorts in the secondary school) by the Giftedness and Excellence Schools Review Committee formed by a decision of the Minister of Education (Report of the Giftedness and Excellence Schools Evaluation Committee, Citation2021). The study traced students’ joining the university. and show the results of this study:

Table 1. The specializations that gifted students attended in higher education institutions

Figure 2. Tracing the enrollment path of the gifted class of 2014 in higher education institutions. adapted from (Report of the Giftedness and Excellence Schools Evaluation Committee, Citation2021).

The results above show that large numbers of gifted students joined colleges of engineering, medicine and other medical specialties, followed by science, in general, these careers are desirable in Sudanese society, and sought by the elite of society.

9. Organismic learning capital

This dimension looks at how much care is taken to ensure that gifted children learn in the best physical condition. It covers their diet or sleep habits and other health and physical aspects.

The study by Al-Hadabi and Al-Odari (Citation2019) about the counseling needs of gifted students revealed that the students’ health-related needs were high, whereas other needs were low. Alshaer (Citation2011) revealed that the percentage of stunted growth among gifted school students reached 16.2% and that the differences were statistically significant at the 0.01 level between intelligence and their nutritional level.

10. Telic learning capital

This dimension addresses the role that gift development plays in gifted students’ motivation system. Do they appreciate learning? What other interests do they have that could interfere with the development of their gifts (computer games, meeting friends, etc.). How important are their careers from their perspective?

In the study by El-Tayeb (Citation2008), teachers highly rated the degree of leadership in gifted students, while their rating of achievement motivation was low. Malik and Kambal (Citation2018) found that the emotional balance of gifted students in the state of Khartoum was high. Abdullah (Citation2020) reported a correlation between the dimensions of emotional intelligence (self-awareness, self-regulation, motivation, sympathy and social skills), creative thinking and achievement motivation among students of gifted and excellence schools in basic education in Khartoum state. Idris (Citation2016) reported high leadership and emotional intelligence among students of gifted and excellence schools in the state of Khartoum. The study also found a direct relationship between leadership and emotional intelligence. No differences by gender, age and parental education were found in leadership. However, a relationship was found between leadership and birth order. S. Ibrahim (Citation2018) revealed correlational relationships between leadership skills, and their relationship to some personality traits among gifted students in secondary schools in the state of Khartoum. Rabeh (Citation2016) found that the psychological needs of gifted students were low, whereas their psychological problems were high, especially jealousy and isolation. A relationship was found between psychological needs and achievement motivation, between psychological problems and achievement motivation, and between achievement motivation and self-esteem. No differences were found in needs and problems by gender in jealousy and isolation.

11. Episodical learning capital

This dimension deals with the educational experiences of the gifted in general. Do they find learning fun? Are their peers more likely to view them as obsessive and try to hide their educational successes? Are they more hesitant to learn? Do they feel that learning at school is beneficial to their lives?

No studies have been conducted on this dimension, but visitors to gifted schools have observed that students are happy and enthusiastic and love life, which indicates that they enjoy their presence in these schools. This dimension can be assessed by dropout rates, but no statistics are available about dropout rates in these schools. Abu Kaif and Farah (Citation2016) reported that gifted students had a higher level of quality of life than other students.

12. Attentional learning capital

This dimension deals with the amount of time and attention that gifted students spend in learning and developing their gifts. Does this vary depending on the area of giftedness? How focused is the work when learning or training? Is this a recreational activity or can it be described as deliberate practice?

No studies have been conducted on this dimension, but it is noticeable that students of gifted schools spend significant time on educational skills.

13. Limitations

actually, studying such subject requires an empirical method, especially with regard to analyzing the reality of nurture for the gifted in Sudan. Indeed, the researchers prepared an interview model based on the Actiotope model and the perspective of learning resources, but the response to it was not sufficient from the target educators, so it was not possible to benefit from these limited responses provided. Therefore, the researchers were unable to complete an empirical study on this subject, in addition to that, there wasn’t available enough literature in the Arabic language about perspective of learning resources, as well as the lack of certified translation of the scales and measurements prepared in the midst of this ambitious model. Also, due to the difficulty of identifying those interested in the field of gifted nurture in Sudan. finally, there are important empirical studies that we advise researchers to carry out to obtain more information to develop the experience of nurture of the gifted in Sudan, the most important of which are: translation, adaptation and standardization the Questionnaire of Educational and Learning Capital (QELC), which will facilitate conduct empirical studies about Actioetop in Sudan, and carry out it to do many studies in the Sudanese environment, moreover do cross cultural studies between gifted in Sudan and other countries.

14. Conclusions

With regard to the exogenous educational resources of economic educational capital and infrastructural educational capital, the results indicated that funding and logistical aspects are not commensurate with the development of gifted projects and that the infrastructure is insufficient to achieve the goals of gifted education. The cultural educational capital is still being researched. As for social educational capital and didactic educational capital, there is a need for more qualification and training.

In considering the endogenous learning resources, we found partial successes in actional learning capital, but these successes do not mount up to what is found in developed countries. Perhaps, gifted students haven’t had enough opportunities to show their potential in international competitions and awards. Research studies are very few concerning organismic learning capital, telic learning capital, episodical learning capital and attentional learning capital.

There is evidence that gifted students have health needs and rates of stunted growth because of the economic situation of the state, as most gifted children are from middle-income families. There is a need for very great effort on the part of the state, its institutions and society as a whole to improve gifted education in the Sudan.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Salaheldin Farah Bakhiet

Salaheldin Farah Attallah Bakhiet

(PhD, University of Khartoum, Gifted & Talented Education) is currently professor of Special Education in the College of Education at King Saud University, Saudi Arabia. His research interests include in gifted education, Intelligence, and creativity. The research reported in this paper relates to a continuous project a bout follow-up of gifted education in Sudan to contribute in its development and progress.

Huda Fadlalla Ali Mohamed

(PhD, University of Khartoum, Deaf and Hard of Hearing Education) is currently associate professor & head of the department of special education in the college of education at University of Khartoum. Her research interests include in Education of people with disabilities, Planning and developing special education programs, & gifted deaf children.

References

- The Comprehensive National Strategy 1992-2002. (1992). Wizarat altarbiat waltaelim [The Ministry of Education.].

- The quarter-century strategy in the republic of sudan 2002-2027. (2002). Wizarat altarbiat waltaelim [Ministry of Education and Instruction].

- Abdal-Rahim, N., & Al-khatib, M. (2009). Dalalat sihat wamwthuqiat aikhtibarat almasfufat altadrijiat lijun rafin (alaikhtibar almulawin - alaikhtibar alqiasiu - alaikhtibar almutaqadimi) biwilayat alkhartum [Indications of validity and reliability of John Raven’s progressive matrices tests (colored test - standard test - advanced test) in Khartoum State]. Sudan. Journal of Science and Technology, 11(1), 169–19.

- Abdel Mageed, M. (1975). Taelim almawhubin fi jumhuriat alsuwdan aldiymuqratia [Educating the Gifted in the Democratic Republic of Sudan]. Educational Research and Documentation Center.

- Abdel Rahman, S. (1997). Altiqnin alsuwdaniu watukayaf miqyas (hamnun - nilsun) lildhaka’ [The Sudanese Standardization and Adaptation of the (Himnon - Nelson) scale of intelligence] Unpublished Master’s Thesis. University of Khartoum.

- Abdelazim, L. (2005). Baed simat almawhubin alfikriiyn wamaeayir altaearuf ealayhim fi almadaris alnamudhajiat biwilayat alkhartum [Some traits of the intellectual gifted and the criteria for their identification in the model schools in the state of Khartoum]. Unpublished PhD thesis, University of Khartoum:.

- Abdelazim, L. (2015). Taqyim baed eanasir manahij almawhubin fi alsuwdan fi daw’ almaeayir alwataniat lidaman jawdat altaelim aleali fi alsuwdan [An evaluation of some elements of the gifted curricula in Sudan in light of the national standards to ensure the quality of higher education in Sudan. Journal of the College of Education University of Khartoum, 9, 74–103.

- Abdullah, H. (2020). Aldhaka’ aleatifiu waealaqatuh bialtafkir al’iibdaeii wadawafie al’iinjaz ladaa talbat madaris almawhubin walmutafawiqin fi marhalat altaelim al’asasii biwilayat alkhartum. [Emotional intelligence and its relationship to creative thinking and achievement motivation among students of gifted and excellence schools in the basic education stage in Khartoum State] .an unpublished PhD thesis, Faculty of Arts, University of Khartoum.

- Abu Kaif, S., & Farah, F. (2016). Turuq mueamalat alwalidayn waealaqatiha bijawdat alhayaat ladaa almawhubin biwilayat alkhartum [Methods of parental treatment and its relationship to the quality of life among the gifted in the state of Khartoum]. Postgraduate Journal, 23, 331–380.

- Ahmed, Z. A., & Bakhiet, S. F. (2021). The availability and use of information and communication technology at gifted primary schools in the sudan. Journal of Innovation, Creativity and Change, 15(5), 816–848. https://www.ijicc.net/images/Vol_15/lss_5/15526_Ahmed_2021_E1_R.pdf

- Al-Hadabi, D., & Al-Odari, I. (2019). Alaihtiajat al’iirshadiat lilmawhubin biwilayat alkhartum [Counseling needs for gifted students in the state of Khartoum]. International Journal of Excellence Development, 19(10), 1–21. https://search.shamaa.org/FullRecord?ID=253117

- Al-Hadi, I. (1981). Alqudrat ealaa altafkir al’iibdaeii waealaqatih bimustawaa altumuh wabaed mutaghayirat alshakhsiat al’ukhraa [The ability to think innovatively and its relationship to the level of ambition and some other personality variables]. Unpublished Master’s Thesis, Al-Azhar University.

- Al-Hussein, A. (2005). Altakayuf waltaqnin limiqyas wikslir lidhaka’ al’atfal, altabeat althaalithat, wilayat alkhartum [Adaptation and Standardization of the Wechsler Scale of Children’s Intelligence, third edition, in Khartoum State] Unpublished Master’s Thesis, Al-Neelain University

- Al-Hussein, A. (2008). Altakyif waltaqnin limiqyas Dhaka’ al’atfal Wechsler altabeat althaalithat bialwilayat alshamalia [Adaptation and Standardization of the Wechsler Children’s Intelligence Scale third edition, in the northern states]. ( Unpublished doctoral thesis). Al-Neelain University.

- Al-Jamri, Z. (2012). Aineikasat alqudrat alfaniyat ealaa tahsil almawhubin fi almadaris althaanawia [Implications of Art abilities on the achievement of gifted students in secondary schools] unpublished Ph.D. thesis. College of Education, Shendi University.

- Al-Khatib, M., and Al-Mutawakel, M.(1998).dalil aistikhdam miqyas almasfufat almutadarijat aleadii ealaa albiyat alsuwdania [Aguide to using the Standard progressive matrices Scale on the Sudanese Environment]. Khartoum, Currency house printing company.

- Al-Khatib, M., Al-Mutawakel, M., Bakhiet, S., & Abdel Rahim, N. (2021). Aikhtibar almasfufat almulawanat almutadarijat ealaa albiyat alsuwdaniat lil’atfal min sinin (4-6) sanawat [Standardization of the colored Progressive matrices test on the Sudanese environment for children aged (4-6) years]. Ajwad Media for printing and advertising.

- Al-Khatib, M., Al-Mutawakel, M., & Mirghani, A. (2006). Taqnin aikhtibar almasfufat almulawanat almutataliat litulaab alhalqat al’uwlaa min almarhalat al’asasiat biwilayat alkhartum [Standardization of the colored successive matrices test for students of the first cycle of the basic stage in the state of Khartoum]. the currency printing company limited.

- Al-nail, S. (2000). Tasmim barnamaj mutaqadim litanmiat altafkir aliabtikarii [Designing an advanced program for the development of innovative thinking] Unpublished Master’s Thesis. University of Khartoum.

- Al-Rasheed, S. (2010). Aldhaka’ aleatifiu ladaa almuealimin waltulaab waealaqatih bibaed almutaghayirat aldiymughrafiat fi madaris almawhibat waltamayuz walmadaris aljughrafiat alhukumiat fi almarhalat al’asasiat biwilayat [Emotional intelligence among teachers and students and its relationship to some demographic variables in schools of talent and excellence and in government geographical schools in the basic stage in the state of Khartoum] unpublished master’s thesis. Faculty of Arts, Al-Neelain University.

- Al-Taher, S. (2014). Faeiliat barnamaj kwrt fi tanmiat altafkir al’iibdaeii waldhaka’ ladaa tulaab almustawaa althaani almutamayizin bialmarhalat althaanawiat biwilayat alkhartum [The effectiveness of the Cort program in developing creative thinking and intelligence among outstanding second-level students at the secondary stage in Khartoum State] A PhD thesis published in ([email protected]. www.sustech.edu). College of Education, Sudan University of Science and Technology.

- Aldood, A., & Abu Al-qasim, A. (2020). Taqwim baramij taelim almawhubin biwilayat alkhartum fi daw’ almaeayir alduwaliat lirieayat almawhubin wataelimihim min wijhat nazar muealimi altarbiat alkhasati [Evaluation of gifted education programs in Khartoum state in light of international standards for the care and education of the gifted from the viewpoint of special education teachers]. Journal of Educational Sciences, 7(2), 411–452. https://journals.kku.edu.sa/jes/ar/node/336

- Algack, M. (1998). ‘Ahamiyat alrieayat altarbawiat liltulaab almutafawiqin akadymyaan fi almarhalat al’asasiat bimuhafazat ‘am dirman [The importance of educational care for academically outstanding students in the basic stage in Omdurman Governorate]. unpublished master’s thesis, International University of Africa

- Ali, A. (2002). Alealaqat bayn altafkir al’iibdaeii waltafkir alaistinbatii ladaa talbat kuliyat alfunun aljamilat bijamieat alsuwdan [The relationship between creative thinking and deductive thinking among students of the college of Fine Arts at the University of Sudan]. Unpublished PhD thesis, University of Khartoum.

- Ali, H. (2020). Aistikhdam ‘anzimat altaelim al’iiliktrunii maftuhatan almasdar limuealajat mashakil tajribat almadaris almawhubat fi alsuwdan (nizam almajmueat - alhuzmati) [The use of open-source e-learning systems to address the problems of the experience of gifted schools in Sudan (the Group- package system)] Unpublished PhD thesis. College of Graduate Studies, Al-Neelain University.

- Alshaer, K. (2011). al’atfal almawhubun biwilayat alkhartum: Dirasat biographia [Gifted Children in Khartoum State: A Biographical Study] Unpublished PhD thesis, Council for Economic, Social and Human Studies, Sudan Academy of Sciences.

- Badri, M. (1966). Saykulujiat rusumat al’atfal - akhtibar rasm alrajul watatbiqatih ealaa alduwal alearabia [The psychology of children’s drawings - the test of drawing a man and its applications on Arab countries]. Dar Al-Fath for printing and publishing.

- Badri, H. (1997a). A trial of standardization of Columbia Mental Maturity Scale (CMMS) in Khartoum state Unpublished M.A thesis. University of Khartoum.

- Badri, M. (1997b). Saykulujiat rusumat al’atfal - akhtibar alrasm albasharii watatbiqatih fi alduwal alearabia [The psychology of children’s drawings - human drawing test and its applications to Arab countries] (Second ed.). Dar Al-Fath for printing and publishing.

- Bakhiet, S. (2005). ‘Asus altaearuf ealaa almawhubin fkryaan fi almarhalat al’asasia (halat tulaab alhalqat althaaniat bimadaris alqibs biwilayat alkhartum) [The foundations of Identification intellectual gifted children in the basic stage (the case of students of the second cycle in Al-Qabas schools in Khartoum state)] Unpublished PhD thesis. University of Khartoum.

- Bakhiet, S. (2008a). Alnuskhat alsuwdaniat min qayimat taqdirat almuealimin likhasayis al’atfal almawhubin fi marhalat altaelim al’asasii “qayimat al’aliksu lilmisuhat al’awaliat lilmuhubin”The Sudanese version from the list of teacher’s estimates of the characteristics of gifted children in the basic education stage “List of Alecso for the initial surveys of the gifted”]. Journal of Education and Psychology Message, 31, 123–162. https://search.mandumah.com/Record/111202

- Bakhiet, S. (2008b, March 25). The factorial strategy: a new technique for selecting the gifted.webpsychempiricist. Retrieved from March 25, 2008 http://wpe.info/papers_table.html

- Bakhiet, S. (2008c). ‘Iijra’at tahdid al’atfal almawhubin biwizarat altarbiat waltaelim biwilayat alkhartum (2004-2007) [Procedures for Identification gifted children in the ministry of education in khartoum state (2004-2007)]. Psychological Studies, 6, 89–143.

- Bakhiet, S. (2009a). Faeaaliat aikhtibar almasfufat almulawanat almutadarijat ka’adaat lilfahs al’awalii liltulaab almawhubin fi alhalqat al’uwlaa fi marhalat altaelim al’asasii [The effectiveness of the colored progressive matrices test as a tool for the initial screening of gifted students in the first cycle in the basic education stage]. The Arab Journal of Special Education, 15, 49–80.

- Bakhiet, S. (2009b). Tatwar tarbiat almawhubin walmutafawiqin fi alsuwdan [The development of nurture for gifted and talented children in Sudan]. Journal of the Arab Psychological Science Network, 21(22), 301–307. https://search.mandumah.com/Record/111202

- Bakhiet, S. (2012). ‘Iieadat mueayarat wa’iieadat taqnin aikhtibar almasfufat altadrijiat alqiasiat biaistikhdam namudhaj rash [recalibrating and restandardizing the standard progressive matrices test using rasch model]. International Interdisciplinary Journal of Education, 1(10), 749–760. http://iijoe.org/index.php/IIJE

- Bakhiet, S. (2013). Revalidating the arabic scale for teachers’ ratings of basic education gifted students’ characteristics using rasch modeling. Turkish Journal of Giftedness and Education, 3(2), 66–80. http://dergipark.org.tr/tr/download/article-file/1475982

- Bakhiet, S. (2014). local norms for some subtests of the third version of wechsler intelligence scale for children (WISC-III) in gifted schools in khartoum. Mankind Quarterly, 54(3–4), 386–433. http://www.mankindquarterly.org

- Bakhiet, S. (2015). Alkhasayis alsaykumitriat lilnuskhat almuearibat limiqyas al’anshitat alsafiyia [Psychometric properties of the arabized version of my classroom activities scale (MCA)]. Educational and Psychological Studies Journal of the Faculty of Education in Zagazig, 87(1), 125–161. https://sec.journals.ekb.eg

- Bakhiet, S., & Al-Hassan, Z. (2011). Al’iirhaq alnafsiu wamasadiruh lilmuealimin almawhubin fi alsuwdan [Psychological burnout and its sources for gifted teachers in Sudan]. Umm Al-Qura University Journal of Educational and Psychological Sciences, 3(1), 12–68. http://uqu.edu.sa/jep

- Bakhiet, S., & Al-Hassan, Z. (2014). Faeaaliat barnamaj tadribiun fi tanmiat waey almuealimin almawhubin fi alsuwdan hawl turuq muealajat albayanat litahdid almawhubin watahsin mawaqifihim tujah eamaliat tahdid almawhubin [The effectiveness of a training program in developing the awareness of gifted teachers in Sudan about the methods of processing data for gifted Identification and improving their attitudes towards the process of gifted identification]. Arab Studies in Education and Psychology, 46(3), 11–40. https://saep.journals.ekb.eg/

- Bakhiet, S., Al-mutawakel, M., Haseeb, B., Ali, N., & Al-Hassan, S. (2007). Alkhasayis alqiasiat liakhtibar almasfufat altadrijiat alqiasiat li’atfal alfiat aleumuria (8-12) sunat fi madinat kusti [standard properties of standard progressive matrices test for children of the age group (8-12) years in kosti city]. Juba University Journal of Arts and Sciences, 6, 10–31.

- Bakhiet, S., Alshaer, K., & Meisenberg, G. (2014). factor structure of wechsler intelligence scale for children -third edition (WISC – III) among gifted students in the sudan. Mankind Quarterly, 55(1–2), 147–170. http://www.mankindquarterly.org/

- Baldo, N. (1993). Dirasat alealaqat bayn aldhaka’ wal’iibdae fi kulin min altahsil aldirasii walqiam ladaa tulaab almarhalat althaanawiat biwilayat alkhartum [A study of the relationship between intelligence and creativity in both academic achievement and values among secondary school students in the state of Khartoum] Unpublished Master’s Thesis. University of Khartoum.

- Bashir, M. (1993). Taedil miqyas stanfurd biniah liunasib albiyat alsuwdania [Modifying the Stanford Binet Scale to suit the Sudanese environment] Unpublished Master’s Thesis. University of Khartoum.

- Belsky, J., & Pleuss, M. (2009). Differential susceptibility to rearing experience: The case of childcare. The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 50(4), 396–404. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01992.x

- Callngham, R. (2013). Chinese students and mathematical problem solving: An application of the actiotope model of giftedness: Rosemary Callingham. In S. N. Phillipson, H. Stoeger, and A. Ziegler (Eds.), Exceptionality in East Asia, Explorations in the Actiotope Model of Giftedness. Routledge, London. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203126387

- Clark, J. (1982). A Study of the Role of the Learning Resource Center in the Education of Gifted Elementary School Students Masters Theses. Masters Theses, Eastern Illinois university. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/2932

- Csikszentmihalyi, M., & Csikszentmihalyi, I. S. (1993). Family influences on the development of giftedness. In The origins and development of high ability (Vol. 178, pp. 187–206). https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470514498.ch12

- Dabrowski, K. (1964). Positive disintegration. Little, Brown.

- Dosa, M. (2007). altaearuf ealaa al’atfal almawhubin fi almarhalat al’asasiat bimahaliyat niala [Identification of gifted children in the basic stage in the locality of Nyala] unpublished PhD thesis. Faculty of Arts, University of Khartoum.

- El-Tayeb, H. (2008). dawafie alingaz wakhasayis alqiadat ladaa al’atfal almawhubin fi almarhalat al’asasiat biwilayat alkhartum (dirasat muqaranatin) [Achievement motivation and leadership trait among gifted children at the basic stage in Khartoum State (a comparative study)] Unpublished PhD thesis, College of Arts, University of Khartoum.

- Fadl, M. (2006). Muqabalat shakhsia [Personal interview], Hilton Jeddah, during the activities of the first regional scientific conference in Jeddah, which was held by the King Abdul Aziz and His Companions Foundation for the Gifted, 27 August 2006.

- Fahmy, M. (1965). Altanshiat aliajtimaeiat waldhaka’ li’atfal alshilik fi janub alsuwdan [Socialization and intelligence of Shilluk children in South Sudan. In L. Malika (Ed.), Readings in Social Psychology in the Arab Countries (1st ed.). National House of Printing and Publishing. pp. 312–42.

- Fahmy, M., & Ibrahim, A. (1954). Dirasat fi janub alsuwdan [Studies in South Sudan]. The Egyptian Renaissance Library.

- Gagné, F. (2003). Transforming gifts into talents: The DMGT as a developmental theory. In N. Colangelo & G. A. Davis (Eds.), Handbook of Gifted education (3rd ed., pp. 60–74). Allyn & Bacon.

- Gardner, H. (1994). Frames of mind: The theory of multiple intelligences. Basic Books.

- Gifted Administration. (2006). Altaqarir alsaadirat ean ‘iidarat almawhubin [Reports issued by the Gifted Administration] unpublished documents.

- Haj-Adam, I. (2020). tahdid almawhubin fi alsafi althaalith alaibtidayiyi bialmarhalat al’asasiat biwilayat alqadarif [Identification of gifted students in the third grade in the basic stage in the state of Gedaref] Ph.D. thesis. Institute for Research and Study of the Islamic World, Omdurman Islamic University, unpublished.

- Hanin, A. (1979). Aleawamil alnafsiat alati takmun wara’ alrida aldirasii ladaa tulaab kuliyaat altarbiat fi alsuwdan [Psychological factors that underlie study satisfaction among students of colleges of education in Sudan] Unpublished Master’s Thesis. Ain Shams University.

- Husain, N., Meisenberg, G., Becker, D., Bakhiet, S., Essa, Y., Lynn, R., & Al Julayghim, F. (2019). Intelligence, family income and parental education in the Sudan. Intelligence, 77, 101402. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intell.2019.101402

- Hussain, A. (2004). Aitijahat alwalidayn fi altarbiat waltaelim ladaa alwalidayn waealaqatihim bialqudrat aleaqliat lil’atfal fi marhalat ma qabl almadrasat dirasat maydaniat bimuhafazat ‘am dirman [Parental attitudes in the upbringing and educational level of the parents and their relationship to the mental abilities of children in pre-school education, A field study in Omdurman Governorate] Unpublished PhD thesis. University of Khartoum.

- Hussein, M. (1988). altiqnin waltakayuf alsuwdaniu limiqyas Wechsler lidhaka’ al’atfal - munaqah [Standardization and Sudanese Adaptation of the Wechsler Scale of Children’s Intelligence – Revised] Unpublished Master’s Thesis. University of Khartoum.

- Ibrahim, B. (1987). ‘Athar turuq tadris aleulum fi tanmiat altafkir alaibtikarii ladaa tulaab almarhalat althaanawia [The impact of science teaching methods on developing innovative thinking among secondary school students] Unpublished Master’s Thesis. University of Khartoum.

- Ibrahim, A. (2008). Mazaya altasrie al’akadimii liltalabat almawhubin fkryan walmutafawiqin akadymyan fi almadaris alnizamia [The advantages of academic acceleration for intellectual gifted and academically superior students in regular schools] an unpublished master’s thesis. Faculty of Arts, Al-Neelain University.

- Ibrahim, S. (2018). Almaharat alqiadiat waealaqatuha bibaed alsimat alshakhsiat ladaa altalabat almawhubin bialmadaris althaanawiat biwilayat alkhartum [Leadership skills and their relationship to some personality traits among gifted students in secondary schools in the state of Khartoum] an unpublished master’s thesis. Omdurman Islamic University.

- Idris, O. (2016). Simat alqiadat waealaqatuha bialdhaka’ aleatifii ladaa tulaab madaris almawhubin walmutafawiqin biwilayat alkhartum [Leadership trait and its relationship to emotional intelligence among students of Gifted and excellence schools in Khartoum State] unpublished master’s thesis. Al-Neelain University.

- Jarwan, F. (1999). Almawhibat waltafouk wal’iibdae [Giftedness, Talent and creativity] (first ed.). University Book House.

- Kassab, Z. (2006). Mabadi tanzim wa’iidarat baramij taelim almawhubin wamurajaeat altajribat alsuwdaniat fi daw’iha [Principles of organizing and managing gifted education programs and reviewing the sudanese experience in its light]. Regional Scientific Conference for Giftedness, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, Jeddah, 26-30 August 2006, working papers, 373–391. saudi Arabia, king Abdulaziz and his Companions Foundation for giftedness and Creativity.

- Khakeefa, O. (1987). almueayarat alsuwdaniat waltakayuf mae miqyas Wechsler lidhaka’ albalighin almunaqah [The Sudanese Standardization and Adaptation of the Wechsler Scale of Adult Intelligence-revised] Unpublished Master’s Thesis. University of Khartoum.

- Khakeefa, O. (1989a). Angizo Atfal biladi al-mawhowbeen 1[save our gifted children1]. Armed Forces Newspaper, sudanese armed forces printing press, 1092, 7, Friday, August 25.

- Khakeefa, O. (1989b). Angizo Atfal biladi al-mawhowbeen 2 [save our gifted children2]. Armed Forces Newspaper, sudanese armed forces printing press, 1101, 5, Tuesday 5 September.

- Khakeefa, O. (2004). Mashrue simbar: Tiqniaat altaearuf ealaa al’atfal almawhubin (taqyim almawhubin waltajribat alsuwdaniati) [the simber project: techniques for identification gifted children (assessment of the gifted and the sudanese experience)]. A paper presented to a panel discussion on methods of teaching and caring for the gifted, the Ministry of State Education in coordination with the Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research, April 15, ministry of education, Sudan, Khartoum.

- Lafferty, K., Phillipson, S., & Costello, S. (2020). educational resources and gender norms: an examination of the actiotope model of giftedness and social gender norms on achievement. High Ability Studies. https://doi.org/10.1080/13598139.2020.1768056

- Leana-Taşcılar, M. (2014). Üstün zekali çocuklarda mükemmelliğin geliştirilmesi için üstünlüğün aktiotop modeli’nin türkiye’ye uyarlanmasi için öneriler. Genç Bilim Insanı Eğitimi Ve Üstün Zeka Dergisi, 2(1), 18–32. https://dergipark.org.tr/tr/download/article-file/487424

- Leana-Taşcılar, M. (2015a). Age differences in the Actiotope Model of Giftedness in a Turkish sample. Psychological Test and Assessment Modeling, 57(1), 111–125. http://www.researchgate.net/publication/274079745_Age_differences_in_the_Actiope_Model_of_Giftedness_in_a_Turkish_sample

- Leana-Taşcılar, M. (2015b). Questionnaire of Educational and Learning Capital (QELC): Turkish language validity and factor structure. College Student Journal, 49(4), 531–541. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/287986185_Questionaire_of_educational_and_learning_capital_QELC-turkish_language_Validity_and_factor_structure

- Leana-Taşcılar, M. (2015c). The actiotope model of giftedness: its relationship with motivation, and the prediction of academic achievement among turkish students. The Australian Educational and Developmental Psychologist, 32(1), 41–55. https://doi.org/10.1017/edp.2015.6

- Maker, C. (1992). Intelligence and creativity in multiple intelligences: Identification and development. Educating Able Learners: Discovering and Nurturing Talent, 27, 12–19.

- Malik, M., & Kambal, A. (2018). Altawazun aleatifiu ladaa altulaab almawhubin fi almarhalat althaanawia [Emotional balance among gifted students at the secondary stage]. Orbits for Social and Human Sciences, 1(3), 515–529.

- Mcinerney, D. (2013). The gifted and talented and effective learning: A focus on the actiotope model of giftedness in the Asian context. In D. M. Mcinerney, S. N. Phillipson, H. Stoeger, and A. Ziegler (Eds.), Exceptionality in East Asia, Explorations in the actiotope model of giftedness, Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203126387

- Moenks, F. (1992). Development of gifted children: The issue of identification and programming. In F. J. Mönks & W. A. M. Peters (Eds.), Talent for the future. Assen/Maastricht (pp. 191–202). Van Gorcum.

- Mohammed, A. (2006). Altajribat alsuwdaniat fi rieayat almawhubin [The Sudanese experience in caring for the gifted]. Journal of Educational Studies, 13, 130–141.

- Mohammed, H., Bakhiet, S., Ali, A., & Al-Amin, S. (2018). Almaeayir alsuwdaniah limiqyas ‘anshitati alsafiiah litulaab almarhalat al’asasiat biwilayat alkhartum [sudanese standards for the scale of my classroom activities for basic stage students in khartoum state]. Journal of Special Education, 22, 224–250. https://sec.journals.ekb.eg/

- Mudrak, J., Zabrodska, K., & Machovcova, K. (2020). Psychological constructions of learning potential and a systemic approach to the development of excellence. High Ability Studies, 31(2), 181–212. https://doi.org/10.1080/13598139.2019.1607722

- Murad, T. (2019). A comparative study between the neural networks’ method, the logistic regression method, and the gradual regression of data for schools of talent and excellence unpublished doctoral thesis. Bakht al-Ruda University.

- Neubauer, A. (2013). Intelligence and academic achievement – With a focus on the actiotope model of giftedness: Aljoscha Neubauer. In S. N. Phillipson, H. Stoeger, and A. Ziegler (Eds.), Exceptionality in East Asia, Explorations in the Actiotope Model of Giftedness, Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203126387

- Osman, M. (1970). Alatfal almutafawiqun [superior children]. Documentation, 2, 67–70.

- Pang, W. (2012). commentary the actiotope model of giftedness: a useful model for examining gifted education in china’s universities. High Ability Studies, 23(1), 89–91. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ992864

- Pereira, N., Bakhiet, S., Gentry, M., Blahmar, T., & Hakami, S. (2017). sudanese students’ perceptions of their class activities: psychometric properties and measurement invariance of my class activities–arabic language version. Journal of Advanced Academics, 28(2), 141–159. https://doi.org/10.1177/1932202X17701881

- Pfeiffer, S. (2013). Serving the gifted: Evidence-based clinical and psych educational practice. Springer.

- Public Education Planning and Organizing Law. (2001). Wizarat aleadl [Ministry of Justice]. Legislation Department. 152,. (5).

- Rabeh, A. (2016). Aliaihtiajat walmushkilat alnafsiat waealaqatuha bidafie al’iinjaz wataqdir aldhaat ladaa altulaab almawhubin fi madaris almawhubin waltamayuz biwilayat alkhartum [Psychological needs and problems and their relationship to achievement motivation and self-esteem among gifted students in the Schools of Giftedness and Excellence, Khartoum State] unpublished Ph.D. thesis. Al-Neelain University.

- Renzulli, J. S. (1986). The three-ring conception of giftedness: A developmental model for creative productivity. In R. J. Sternberg & J. E. Davidson (Eds.), Conceptions of giftedness (pp. 53–92). Cambridge University Press.

- Report of the Giftedness and Excellence Schools Evaluation Committee. (2021). Madaris almawhibat waltamayuz [The Giftedness and Excellence Schools]. Review Committee formed by a decision of the designated Minister of Education.

- Rogers, K. B., & Silverman, L. K. (1997). Personal, medical, social and psychological factors in 160+ IQ children. Paper presented at the National Association for Gifted Children 44th Annual Convention, Little Rock, Arkansas.

- Salman, S. (2000). Wathiqat tarikhiatan liaikhtibar aldhaka’ alsuwdanii [Sudanese intelligence test historical document]. Educational Studies, 1, 138–156.

- Sarouphim, K. (2012). Commentary how novel is the actiotope model of gifted education? High Ability Studies, 23(1), 101–103. https://doi.org/10.1080/13598139.2012.679104

- Schic, H. (2008). research on the actiotope model of giftedness: a discussion. Paper presented at the 11th International conference of the European Council for High Ability, 17.-20. Septemper, Prague, Czech Republik. https://hella-schic.de/ressorces/Discussant_ECHA2008.pdf

- Scott, G. (1946). Intelligence testing in the Sudan. Sudan Notes and Records, 129, 1–14.

- Scott, G. (1948). Intelligence testing in the Sudan. Sudan Pamphlet, 128, 1–13.

- Scott, G. (1950). Measuring Sudanese intelligence. Journal of British Educational Psychology, 20, 43–54.

- The Second National Conference on Education Policies. (2002). Al’iirshadat walnatayij [Guidelines and Results]. Bulletin, 3, 6–8. August, Khartoum, Sudan.

- Silverman, L. K. (1993). A developmental model for counseling the gifted. In L. K. Silverman (Ed.), Counseling the gifted and talented (pp. 51–78). Love.

- Soliman, A. (1996). Dirasat tathir alsifat alnafsiat waleawamil al’usariat walmadrasiat ealaa altahsil aldirasii [Studying the effect of psychological traits and family and school factors on academic achievement]. Unpublished PhD thesis. Omdurman Islamic University.

- Sternberg, R. (2003). WICS as a model of giftedness. High Ability Studies, 14, 109–138. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359813032000163807

- Stoeger, H. (2013). Support-oriented identification of gifted students in East Asia according to the actiotope model of giftedness. In S. N. Phillipson, H. Stoeger, and A. Ziegler (Eds.), Exceptionality in East Asia, explorations in the actiotope model of giftedness, London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203126387

- Stoeger, H., & Ziegler, A. (2005). praise in gifted education: Analyses on the basis of the actiotope model of giftedness. Gifted Education International, 20, 306–329. https://doi.org/10.1177/026142940502000306

- Tannenbaum, A. (1983). Giftedness: A psychosocial approach. In R. J. Sternberg & J. E. Davidson (Eds.), Conceptions of giftedness. Cambridge University Press.

- Vialle, W. (2017). supporting giftedness in families: a resources perspective. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 40(4), 372–393. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162353217734375

- Vialle, W., & Ziegler, A. (2016). Gifted education in modern Asia: Analyses from a systemic perspective. In D. Y. Dai & C. C. Kuo (Eds.), Gifted Education in Asia: Problems and Prospects (pp. 273–291). Information Age Publishing.

- Vladut, A., Liu, Q., Leana-Tascila, M. Z., Vialle, W., & Ziegler, A. (2013). A cross-cultural validation study of the Questionnaire of Educational and Learning Capital (QELC) in China, Germany and Turkey. Psychological Test and Assessment Modeling, 55(4), 462–478. https://ro.uow.edu.au/sspapers/1697

- Vladut, A., Vialle, W., & Ziegler, A. (2015). Learning resources within the Actiotope: A validation study of the QELC (Questionnaire of Educational and Learning Capital). Psychological Test and Assessment Modeling, 57(1), 40–56. https://doi.org/10.1037/t69622-000

- Vladut, A., Vialle, W., & Ziegler, A. (2016). Two studies of the empirical basis of two learning resource-oriented motivational strategies for gifted educators. High Ability Studiesst, 27(1), 39–60.