Abstract

The disruptive effects of this pandemic are predicted to redefine the priorities of continuing professional development (CPD) in the educational sector and reconstruct the identity and role of educators in future educational systems. Accordingly, the primary aim of the proposed research is to critically assess the factors shaping post-Covid-19 identity formation amongst secondary school teachers in Hong Kong to determine the influence of CPD and systemic needs on teacher role perceptions and goal-setting. This study will apply a mixed-methods approach to the collection of quantitative (survey) and qualitative (interview) data from a sample of Hong Kong educators. Through a critical, comparative analysis of these findings and triangulation of the evidence with prior academic theories, a model of educator development and identity formation will be proposed to improve and target developmental support throughout normalisation and post-Covid-19 recovery.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background/context

As the modern educational system weathers what many have recognised as the most disruptive global event in a generation, Covid-19, the constructs and definitions surrounding teachers’ roles and identities are evolving rapidly and incongruously (Kim et al., Citation2021; Murphy, Citation2020). Whereby content-specific and course-based continuing professional development once formed the basis of a stable and moderative pathway to teacher growth and capacity improvement, Ellis et al. (Citation2020) report that fragmentation concerning focus and priority disintegrates the purpose and course of developmental agendas. Despite efforts to standardise the teaching profession through accreditation and credentialism, Garcia and Weiss (Citation2020) observe that many teachers lack sufficient educational background in their subject matter of primary assignment to be considered expert or qualified. Further, as technological pressures and systemic needs evolve out of the digitalisation of education, a new platform of skill sets continues to take precedence, threatening the traditional paradigm of teacher competency and preparedness (Flores & Swennen, Citation2020; Hidalgo-Andrade et al., Citation2021).

According to Marschall (Citation2021), teachers’ identity develops from self-efficacy sources: social persuasion, interaction with personal and external factors, vicarious and enactive experiences, and physiological and enactive states. A balanced interaction between teacher experiences in their professions promotes the development of their identities concerning their professional requirements. Skott (Citation2018) proclaims that teachers are in a constant development process filled with belonging and becoming concerning their profession. Professional transformation is essential to capture the constantly rising needs in the external and internal learning environment. For instance, novice teacher students have met a new set of challenges that stem from the advent of the covid-19 pandemic. The challenges have compelled most teachers to find and employ the most effective teaching strategies with growing concern.

Similarly, much emphasis is placed on teacher development in their subject areas. The background and existing information in specific teaching areas will inform the consequent development and transformation in the contemporary learning environment. According to Colliander (Citation2019), marketisation & streamlining, and migration will impose changes on the approaches employed during the teaching process. For instance, second language acquisition compels teachers to use the most relatable examples during instruction. Besides, the teacher training institutions play a significant role in developing the teachers’ ability to detect and implement changes positively. For example, the psychological development of teacher identity has its framework in the sense of appreciation, connectedness, commitment, competence, and imagining future career trajectory (Van Lankveld et al., Citation2016). The universities employ appreciation to promote a vibrant identity in the teachers while shaping them for their roles.

Recognising the value in teacher trainees finds its way in their teaching subjects and their interaction with the students.

In an assessment of post-Covid-19 experiences, Berry (Citation2020, p. 488) reports that many teachers have struggled to reconcile the “unfamiliarity and uncertainty” in the environmental influences, expectations, and performative challenges of digital learning environments. As a form of “pivot pedagogy”, Schwartzman (Citation2020, p. 516) reports that educators have been challenged to adapt their teaching capabilities to multiple classroom solutions (e.g., digital, hybrid, traditional). Shifting between modes of instruction, acquiescing to changing workloads, schedules, and coursework requirements, and revising the array of skills and competencies needed to fulfill pedagogical duties has not only challenged the concept of self-identity in practice but influenced the role of teaching in both forms and function (Schwartzman, Citation2020).

While most scholars may universally acknowledge that education needs to be adapted to its revised digital standard, the effects on teacher self-identity, confidence, and pedagogy remain uncertain. For many individuals, technology gaps and skills challenges may threaten their long- term career path and teaching role (Flores & Swennen, Citation2020).

To improve teacher performance and competency moving forward, a variety of continuing professional development (CPD) solutions are available, ranging from informal mentorship and induction programmes to formal training, certification, and knowledge acquisition initiatives (e.g., conferences, courses, training; Garcia & Weiss, Citation2020). However, Choate et al. (Citation2021) have demonstrated the potentially damaging effects of Covid-19 on CPD enrolment and content area programme development as educators have refocused their developmental priorities on technical and role-specific (e.g., support, virtual lecturing) skills. The transition into virtual educational solutions is challenging and destabilizing for the traditional educator versed in lectures and front-facing communication. While Watermeyer et al. (Citation2021) have observed a form of emergency-level migration, the competencies and skills required of these educators are far from temporary accommodation. Therefore, it threatens the long-term characteristics and features of education pedagogy.

1.2. Focus of research

The current study has adopted a regional focus, emphasizing the transformative effects of Covid-19 on educational services and teacher responsibilities in Hong Kong’s secondary education institutions. For educators throughout these schools that are predominantly funded and supported by government subsidies, the transition from traditional, in-class English as a foreign language (EFL) education to digital class services has had a radical and disruptive effect. The problem, however, is that many of these experiences remain locked within individual narratives and personal perceptions that are not being reviewed or analysed to address the potential gaps and limitations of this transitional process. Namely, this study has focused on the malleability of the teacher identity and role in secondary EFL education. It highlights the perceived effects of Covid-19 and digitalisation on teacher roles, responsibilities, and skill sets in these evolving institutions.

1.3. Contribution of the study

The primary contribution of this research is a critical review of the experiences and concerns of Hong Kong teachers who have not weathered the challenges and uncertainties of the Covid-19 disruption. By capturing primary evidence of these perceptions and insights, this study has illuminated several critical gaps in the CPD protocol for secondary education teachers and highlighted the consequences of a system in which developmental priorities are fractured and incongruous with teaching roles and responsibilities. The result includes several recommendations for evolving teaching development strategies to address systemic gaps and support teacher self-efficacy to accommodate the changing students’ needs in the current and future learning institutions.

2. Literature review

2.1. Teacher identity and role specificity in practice

The disruption of traditional educational systems by Covid-19 and the associated quarantines resulted in a highly fragmented educational landscape characterised by digital solutions and nomadic teachers and learners (Kim et al., Citation2021). Through a narrative analysis of teacher reports during the early phases of this crisis, Kim et al. (Citation2021) reveal frustration and disappointment associated with the loss of pupil contact and direct interactions that innovative and often inconsistent technological substitutes could not replicate. The conflict between subject- level qualifications and teacher identity observed by Garcia and Weiss (Citation2020) is an increasingly important consideration in educational systems theory. Critical conditions such as adequate qualifications and credentialing are weighed against pedagogical competency and a trait theory of teacher performance. Similar evidence presented by Donitsa-Schmidt and Ramot (Citation2020) has highlighted how during the pandemic, the consequences of teacher shortages and deficient qualifications for those already embedded in existing institutions have led to unpreparedness and declining student care. Ultimately, Comas-Quinn and Comas-Quinn (Citation2011) argues that the success of blended and digital learning outcomes is predicated upon teachers’ technological and academic transition to a new professional identity.

The concept of preparedness and teacher education is crucial when confronted with disruptive events since gaps and limitations affect teacher responsiveness to difficulties and changes in institutional expectations (Donitsa-Schmidt & Ramot, Citation2020). For example, since the onset of Covid-19, Berry (Citation2020) narrates a complex internal monologue through which teachers challenge themselves to address issues related to the unfamiliarity of digital learning, the uncertainty surrounding ongoing expectations, and the tension between effectiveness and efficiency in student support. In this personalised discourse, failure is not a function of traditional bounding mechanisms such as pass/fail or performance outcomes. Instead, it is a weighted interpretation of the link between goal achievement (e.g., students all complete tests) and knowledge transfer (e.g., complete or incomplete) outcomes (Berry, Citation2020). Rudick and Dannels (Citation2020) have observed an institutional shift towards inclusive and adaptive educational standards. Lack of continuity and transparency regarding such standards and practices continue to restrict the ability to transfer and communicate the objectives. While key antecedents such as willingness to change create the primary sustaining influence for teacher transitioning, Comas-Quinn and Comas-Quinn (Citation2011) observes that clear goals, system transparency, and teacher development are all essential to support a positive shift into blended or digital education.

As working environments evolve, the effects of digital learning and digital pedagogy on teacher role identity have the potential to reshape the educational system. In an experimental assessment of emotion, expression, and response mapping, Lo (Citation2020) observed that variables such as video quality, distance from the camera, teacher responsiveness, sound quality, and expressivity had distinct effects on student learning experiences. By downloading and transferring video records to communities of practice, the researcher highlighted how to use community practices to inform teacher behaviour through constructive feedback and support (Lo, Citation2020). The loss of direct student-teacher interactions reported by Van Nunland et al. (Citation2020) has disrupted the educational process’s personalization and intimacy. Still, it has challenged both stakeholder groups to adapt their behaviours and practices in the educational environment towards more disconnected, individual solutions. Whereby uncertainty and instability in teacher responsibilities have led to a form of treading water or purposeful waiting, Anderson et al., Citation2021) highlight the critical role of creative self-efficacy and positive developmental progress to support educators in overcoming the trauma and adverse effects of the Covid-19 crisis.

2.2. Covid-19 and self-assessment theory of teacher identity

Emphasis on the effectiveness and intrinsic value of digital education and virtual instruction has been elevated to a primary educational concern (Choate et al., Citation2021) following the closure of learning institutions from the effects of covid-19. Key considerations such as the relationship between students and teachers in virtual-only education, the lack of face-to-face exchanges, and the array of skills and technical competencies are required for teacher proficiency. Besides, Choate et al. (Citation2021) observed a wave of uncertainty in a field that always depended upon its structural rigour and consistency for the support. For many educational institutions, what Watermeyer et al. (Citation2021) has observed as a form of emergency response has migrated towards the commodification of the educational process, expanding digital learning opportunities at the expense of the traditional educational environment. Through a survey of educators and thought leaders, the researchers observe a value-based threat as this “inferior, mass-produced product” is integrated into an educational system once dependent upon a unique array of educator skills and pedagogical competencies (Watermeyer et al., Citation2021, p. 631).

The changing teaching environment, for example, mandates consideration regarding teacher responsibilities, competencies, and skill sets, particularly in light of recent techno-centric transformations of the educational system (Garcia & Weiss, Citation2020). Whereby Mose (Citation2020) reports that Covid has inspired a new standard of flexibility and structural adaptability from an administrative perspective, the lack of transparency and precise definition of such priorities has resulted in teacher and student confusion across educational institutions. For teachers confronted with developmental and role-specific hurdles, Ellis et al. (Citation2020) observe that stabilising initiatives and normalisation strategies related to CPD and teacher education are needed. While ameliorative, temporary solutions may secure against additional losses and knowledge gaps without more direct reinforcement and targeted educational support. It is predicted that teaching quality and performance will likely suffer in the medium to long term (Ellis et al., Citation2020). Wyatt (Citation2020) argues that the realisation of self-efficacy and teacher confidence provides sustainable solutions to transition from uncertainty and instability into successful, high-performing digital solutions.

Consequently, there can be an expectation of more robust, creative responses to digital learning experiences in the future that push educators beyond their traditional perceptions of best practices and communication (McWilliam & Dawson, Citation2008). However, Schwartzman (Citation2020) argues that educational systems must first determine the how and why of online student learning to develop solutions that fulfill the degree-level needs and create positive relational bridges between pedagogy and student learning outcomes. Whereas pandemic resilience became a beacon and rallying cry for much of the educational system, pursuing such “pivot pedagogy” has resulted in the transition from explicit, targeted courses to adaptive, multi-modal solutions. The solutions can engage students across platforms as the “new normal” has been realised (Schwartzman, Citation2020, p. 512). Therefore, Murphy (Citation2020) argues that researchers must distinguish between the emergency conditions mandated during the Covid-19 response and the sustainable, educationally-oriented securitisation of the system in which students will achieve high- performing outcomes and valuable knowledge transfer over the long term.

For language teachers, the progression from traditional, contact-based teaching environments to digital educational landscapes facilitates a shift in teacher roles and responsibilities (Kodrle and Savchenko, Citation2021). Through an assessment of programme evolution, Kodrle and Sachenko (Citation2021) demonstrate how interactive media and high-involvement programs such as podcasts or virtual exercises allow teachers to communicate language-specific idiosyncrasies and variances that have a positive effect on student learning outcomes. In educational systems, technological skill gaps and digital citizenship may inhibit the effectiveness of high-involvement digital learning. Oraif and Elyas (Citation2021) observe that teacher-centred education is preferred, with visual face time bridging student frustration and effective educational outcomes. Similarly, Hazaymeh (Citation2021) confirms that skill-set gaps related to writing and speaking proficiencies for EFL students require mirroring exercises that utilise existing text and content to encourage student communication and engagement in virtual classroom activities. By diversifying the information resources and pedagogical tools available to educators, the transition toward productive learning outcomes is primarily facilitated by teacher support and systemic confidence. These conditions have evolved substantially over the Covid-19 crisis (Hazaymeh, Citation2021).

2.3. Education strategies in Hong Kong before and after covid-19

Hong Kong has undergone a series of changes in its educational systems to accommodate the changing needs and challenges in the country’s social structure. The first reform took place in 2008, dubbed the through-road model. According to Poon and Wong (Citation2008), the “through-road” model eliminates inequity and inequality in education by employing J.P. Farrell’s equality and equity concepts. However, the efficiency of the “through-road” model is met with the significant social disparity that still exists in Hong Kong. The country has a significant gap between the rich and the poor that reflects most of its structures and institutions. The efficient application of equality and equity in the curriculum should begin with social structures. The government is responsible for decreasing the gap between the rich and the poor to make the “through-road” model realistic. Further, Hong Kong has introduced changes in its structure of higher learning institutions. For instance, eight UGC-funded higher learning institutions transformed the academic programme from three years to four-year to include liberal arts education in 2012 (Lanford, Citation2016). The university changes were instigated by international standards, values, and controversy over the outcome of the evaluation. Transforming market demands and international benchmarking led Hong Kong’s curriculum developers to introduce effective changes within their learning institutions. The changes are an avenue for most instructors to find the most effective career development programmes to meet the growing demand. The development ranges from the self to professional practices.

Furthermore, curriculum changes paved the way for the introduction of online learning after the covid-19 pandemic. The global pandemic compelled Hong Kong’s curriculum developers to change their approaches to instruction as they tried to minimise possible infections. The parents were forced to avail social support and prepare their children for the new changes in the learning environment (Lau & Li, Citation2021). The preparation was essential as digital learning provides new challenges for students and teachers. For instance, Law et al. (Citation2022) proclaim that teacher-student and student-student interactions present significant challenges during online lessons. Besides, the teachers and students require prior knowledge to use the platform for effective instruction. Hence, the curriculum developers in Hong Kong consistently aim to promote mastery of relevant skills to use the online learning platform (Law et al., Citation2022). They also infused the changes in curriculum previously made to carry on with relevant content and produce effective assessment results.

On the contrary, online learning adoption in Hong Kong has met various challenges to minimise its efficiency. There is a crucial need to shift from fragmented approaches that focus on acquiring ICT infrastructure and employ the strategies that enhance the use and adoption of e- learning to support student learning (Kahiigi et al., Citation2009). Efficiency in online learning stems from giving the students sufficient skills to use the ICT equipment used in e-learning. It also relies on the availability of resources to acquire laptops and other devices used during online learning. The Hong Kong curriculum developers have failed to give the necessary knowledge on using the devices. Besides, the laxity in learning using the devices stems from eroding the country’s social and cultural practices (Law et al., Citation2022). The new form of learning is a complete transformation from the previous face-to-face learning. It disintegrates social interaction and the physical touch to learning, contrary to the country’s social values and practices. Consequently, the curriculum developers within the country are responsible for training teachers and students while also localizing the content to ensure efficiency during the e-learning process. The training is also necessary to shape teacher identity to meet the required personal traits for efficient use of the online learning platforms.

3. The present study

The primary aim of this study is to critically assess the factors shaping post-Covid-19 identity formation amongst secondary school teachers in Hong Kong to determine the influence of CPD and systemic needs on teacher role perceptions and goal-setting. In pursuing this core aim, the following primary research objectives have been established:

To assess the impact of Covid-19 on educational digitalisation and teacher development practices.

To analyse the expectations and responsibilities for EFL teachers amongst Hong Kong secondary EFL institutions.

To weigh and evaluate the perceptions of Hong Kong-based secondary education teachers regarding personal needs and development objectives following Covid- 19.

To propose solutions for improving teacher development outcomes via future support programmes and role-based redefinition guidelines.

4. Research method

4.1. Research paradigm

Multi-dimensional research and data collection techniques are adopted to assess teacher experiences and developmental priorities. Bryman (Citation2015) observes that positivist and constructivist paradigms drive evidence collection in social research. Positivism emphasises knowledge and theory testing via rigorous statistical analysis and quantitative techniques (Jonker & Pennink, Citation2010). In contrast, constructivism embraces experiential feedback and situational observations (Jonker & Pennink, Citation2010). Thus, quantitative and qualitative techniques are integrated into the study to allow triangulation and comparison of evidence from multiple streams in a pragmatic approach to empirical research (Morgan, Citation2014). The mixed method includes the collection of quantitative evidence via a structured survey instrument and qualitative evidence from open-ended interviews (Creswell & Clark, Citation2017).

4.2. Sampling and participant selection

The study targets a pre-qualified sample of representatives from Hong Kong’s secondary education industry. The selection criteria involve employment as a teacher within Hong Kong’s secondary education system and ESL or advanced English subject teacher. Internal network communication initially targeted a sample of 250–500 teachers. After a three-week administration period, 193 participants for the survey instrument were identified as optimal, representing a substantial percentage of this experientially diversified population. The interview involves administering the form to a small sample, focusing on the quality and depth of the feedback to avoid the variable scope of diversified participant reporting (Glaser & Strauss, Citation2012).

Therefore, the researcher identified a small focus group of 3 educators with direct experience in digital education in ESL. The interviews are administered via direct contact, Zoom, and telephone communication.

Sampling offers balanced information from country representatives with cross-national comparability (Reynolds et al., Citation2002). It is often carried out within the domestic environment to accurately depict the educational strategies employed in Hong Kong learning institutions. Hence, the selected sampling approach gives the researcher theoretically appropriate research aims that align with the highlighted research objectives (Reynolds et al., Citation2002).

4.3. Data analysis

Data analysis employs a parallel design that separates quantitative and qualitative findings for practical interpretation (Watkins & Gioia, Citation2015). The quantitative analysis uses statistical resources and modules in Microsoft Excel to compare the participants’ mean responses, visually chart the outputs, and interpret the relationships between grouped variables (Bryman, Citation2015). Further, the qualitative approach employs thematic analysis through frequency analysis and comparative reasoning to interpret the results (Merriam, Citation2015).

4.4. Ethical concerns

The researcher is responsible for preventing harm and mitigating threats to participants during empirical research. Thus, the study employs structural controls and explicit conditions founded in the research architecture (Punch, Citation2014). Specifically, the study maintains anonymity to minimise participant exposure and enhance honest and direct responses to the target questions (Babbie, Citation2015). Besides, the researcher gives the participants a standard form query letter outlining their rights, anonymity conditions, and research focus. Their agreement to the document demonstrates informed consent and willing participation throughout the research (Hammersley and Trainou, Citation2012).

5. Results

5.1. Survey findings

The first stage of the primary research was to capture representative empirical evidence from a sample population of 193 educators from varying secondary education institutions in Hong Kong (See and ). The following sections critically compare the findings, weighing population- grouped biases against core themes and targeted prompts related to professional development and teacher roles.

Appendix A. Survey Instrument With Results

Appendix B. Interview Form

5.1.1. Demographic and experiential overview

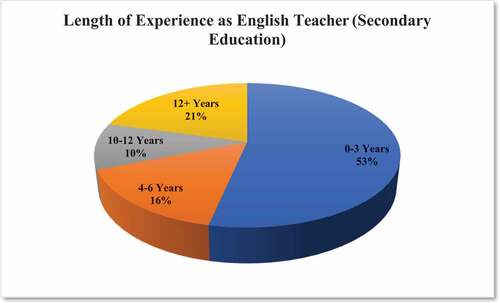

The demographic dimensions were collected as grouping mechanisms and independent variables for cross-sample comparisons. Figure visualises the length of experience reported by these participants. 53% indicated less than three years, and 21% indicated 12 years or more. This bias indicates an early-career pathway for most of the participants in this study which will be considered in the comparative analysis.

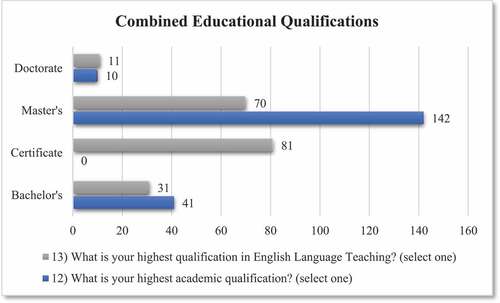

Figure highlights the distinction between academic qualifications and English language teaching qualifications. Although 78.8% of the sample reported an academic qualification at the Master’s level or above, just 41.9% indicated this same qualification level for English Language Teaching. The finding suggests that most educators were likely to pursue general academic qualifications (e.g., degree-level programmes) which fell outside their specialisation in the field (English Language). This finding is necessary when the high percentage (94.8) of non-native English-speaking teachers were considered in this sample. It suggests that attaining certificate- level status was adequate for these institutions’ English teaching appointments.

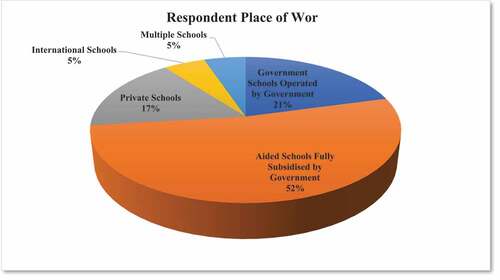

Figure visualises the workplace groupings of the participants, with 73% indicating employment at either an aided, government subsidised school, or government school operated by the government. The bias is normative considering the favourable orientation of the Hong Kong educational system towards government-supported or sponsored programmes.

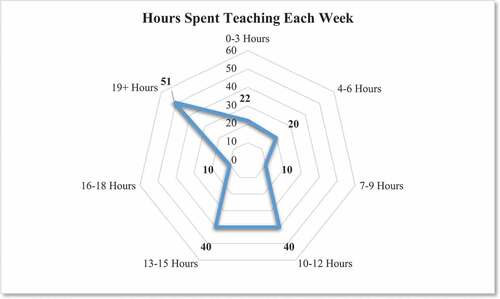

Further, Figure highlights a distribution of teaching timelines (hours per week) with a degree of variability in teaching responsibility. The most significant percentage (26.4%) indicates 19 or more hours weekly, while the combination of two groups representing 41.5% of the sample indicates between 10 and 15 hours weekly. The grouped results confirmed that most participants spend at least 10 hours teaching each week, with a mean of 4.50 (SD = 2.013).

Besides, 68.9% of the sample reported spending less than 50% of their teaching time on English language teaching.

5.1.2. Teacher qualities and competencies

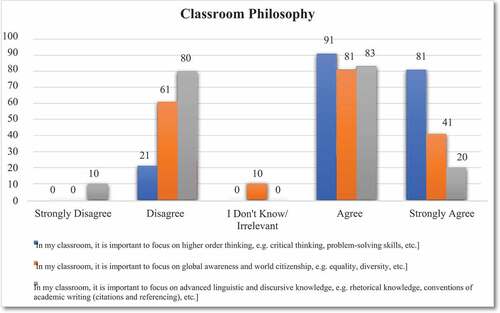

The second series of prompts focused on the trait-based perceptions of these educators regarding the ideal qualities and competencies of English language teachers. As visualised in Figure , there was a relatively positive bias towards these three prompts. For example, 89.2% of the sample reported that focusing on higher-order thinking (e.g., critical thinking) in their classroom is essential. Another 63.2% reported that focusing on global awareness and world citizenship in their classrooms is essential. Significant variation was observed when advanced linguistic and discursive knowledge was considered. 53.4% of the sample agreed with its importance, while 46.6% disagreed with the statement.

Moreover, a negative correlation was observed between the percentage of teaching involving the English language and the statement regarding focus on advanced English language learning (PC = −0.339, P = 0.000). A cross-tabular comparison demonstrates that teachers with less time spent teaching English per week were likely to agree with this statement, while teachers with more time were likely to disagree. Hence, it highlights the effects of higher-level, specialised English courses on teaching priorities.

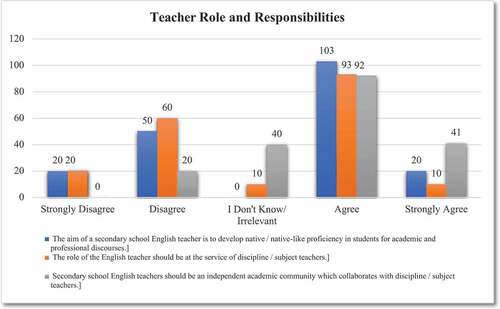

The second series of prompts visualised in Figure focused on teacher roles and responsibilities. 68.9% of the sample agreed that secondary English teachers should develop an independent academic community to support collaboration and specialisation. Further, 63.7% agreed that the primary aim of these English teachers is to assist students in developing native- like proficiency. An additional 53.4% agreed that the role of the English teacher should be at the service of the discipline, with curriculum and learning objectives informing teacher priorities.

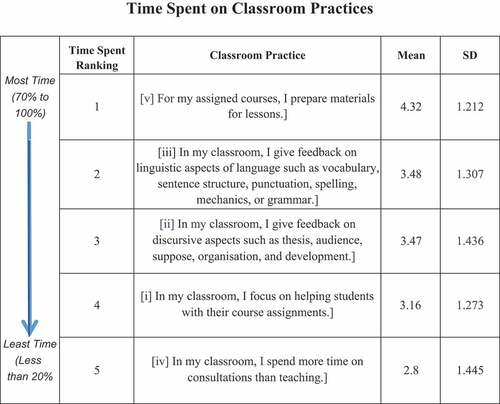

Figure highlights the weighted time spent on classroom practices. It reveals most teachers spent time preparing materials for lessons (M = 4.32), feedback on linguistic aspects of language (M = 3.48), and feedback on discursive aspects of language (M = 3.47). Other variables include consultation (M = 2.80) and assisting students with course assignments (M = 3.16). These findings highlight a targeted commitment to broaden teaching objectives and subject mastery, with less consideration for individual needs.

5.1.3. Teacher traits and qualities

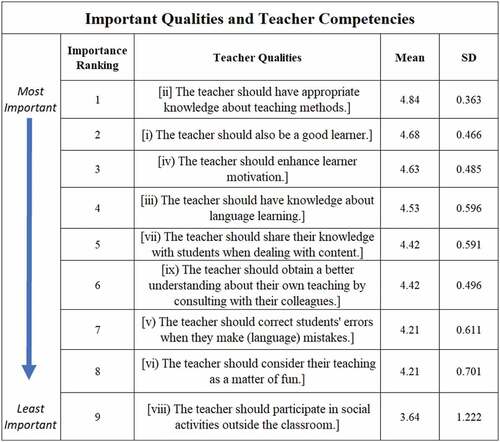

The participants were also asked to reflect on teacher traits and qualities. Figure highlights the ranked importance of crucial qualities. The top traits included appropriate knowledge about teaching (M = 4.84), good learner (M = 4.68), and the capacity to enhance learner motivation (M = 4.63). Other factors such as participating in social activities (M = 3.64) or fun in teaching (M = 4.21) were considered less important than the more practical and role-specific responsibilities.

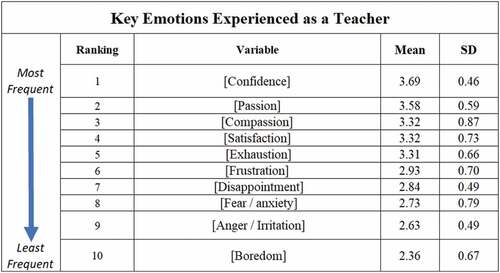

Figure ranks the leading emotions that these teachers in the classroom reported. It includes three positive outcomes of confidence (M = 3.69), passion (M = 3.58), and compassion (M = 3.32). Negative emotions such as boredom (M = 2.36) and anger (M = 2.63) were ranked lower, with less experience frequency. These findings highlight the positive orientation of teacher experiences towards productive or optimistic emotional outcomes.

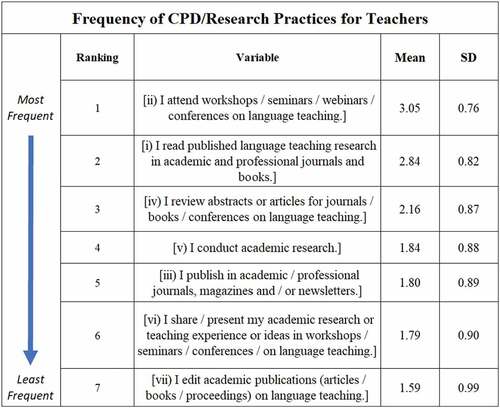

Figure ranks the top CPD behaviours reported by the teachers. It includes two primary solutions: workshops/seminars (M = 3.05) and reading/teaching research in journals (M = 2.84).

Other specific responsibilities such as editing academic publications (M = 1.59) and sharing or presenting academic research (M = 1.79) were not frequently experienced by these participants. It highlights a weighted emphasis on role-specific, teaching-oriented CPD. The finding also highlights the limited role outside developmental opportunities plays in professional growth.

Correlation tests failed to highlight a statistical relationship between outside CPD practices such as journal editing and participant qualifications. It suggests this is also an individually-oriented responsibility, not education or qualification-specific.

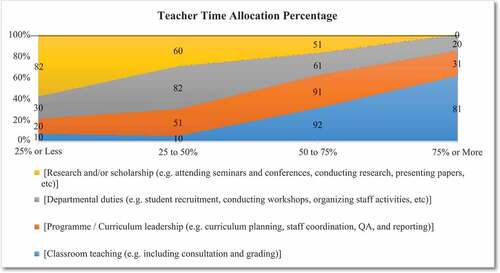

Finally, Figure asked the participants to rank their time allocation concerning teacher development. As evidenced in this model, classroom teaching received the highest level of support, with 89.6% of the sample indicating they spend more than 50% of their time on teaching responsibilities. In contrast, 73.5% reported spending less than 50% on research and scholarship.

5.2. Interview findings

The empirical research focused on semi-structured interviews administered to three teacher representatives from Hong Kong secondary schools. The responses highlight the main themes that constitute the feedback’s weight and consistency.

5.2.1. Question 1

Describe a typical teaching day. What emotion do you feel strongly? Describe an example of a very positive experience. A very negative experience?

The question’s feedback outlines different themes from normative characteristics and the arc of the teachers’ daily responsibilities. There was a consistent representation of teacher expectations and time efficiency from the interviewees: too many meetings, little time for teaching and lesson preparation. For example, 3 T reported that “we have very little time to prepare lessons; most of the time you’re talking about paperwork, admin and meetings.” Besides, 1A narrated that “probably it’s just me doing all the talking … interaction is quite minimal between a teacher and the students.” 2B indicated that their lessons were condensed while

burdens like meetings and paperwork filled in daily gaps. Consequently, 3 T observed that they had minimal time to teach. An underlying expectation of time efficiency and application fragmented daily responsibilities and displaced the current free time. However, 2B predicts that the advent of covid-19 will make the working environment less burdening.

Nonetheless, the interviewees reflected on positive and negative experiences conflicting during the teaching experience. Positive experiences included; ‘you see a student just click on something and get it right (3 T), “experiences working with colleagues” (2B), and ‘when my hard work paid off ‘(1A). In contrast, negative experiences included ‘Being not recognised for what I

do’ (3 T). Inherently, the lack of clarity between intentions and outcomes created a perceptual gap that led to misconceptions about teacher contributions to the educational process. Similarly, 1A reported that “students had their doubts … while I was doing the teaching. I felt that they didn’t trust me.” The emotional impact of distrust and student frustration were disruptive, leading to 1A’s report of educator anger and disappointment. These responses highlighted a tension between triumphs and burdens in the classroom linked to various time, role, and task-based conflicts.

5.2.2. Question 2

Do you attend any activities related to professional development? Why do you join these activities? What are some emotions you feel? How do you feel about conducting academic research?

CPD commitments were similar across all three participants and involved professional and personal developments. For example, 1A reported, “I started writing papers with my colleagues a year ago. 2B also acknowledged the Hong Kong government’s expectation that secondary school teachers should engage in professional development during their careers.

Similarly, 3 T reflected that there are “the mandatory ones and the ones you wanted to attend, but you don’t have time for.” However, as a result of Covid-19, 2B observed that they had not been participating in CPD recently and were looking for “structured professional development courses” for future adoption.

Furthermore, 2B recognised that they were motivated to join informal virtual workshops for personal development. In some cases, these courses were not aligned with professional needs and did not have direct applicability (2B). When weighing such opportunities, 3 T observed that they were encouraged to learn something exciting. Hence, it was evident that two of the participants preferred degree-level development solutions, while one (1A) preferred “challenges” related to the positive contribution of academic research to the field.

5.2.3. Question 3

Is there an alignment between your professional identity and your employer’s expectations? Why do you think/feel this? Do you have sufficient autonomy within your institution? Do you feel there is sufficient opportunity for development? Is there enough institutional support?

All participants acknowledged that their roles were consistent with their institution’s expectations. For example, 1A reported that “they just want someone to teach, to deliver the content.” Similarly, 2B indicated, “ I’m a teacher, my school expects teachers to be teachers, and I’m working hard as a teacher.” 3 T also claimed, “my professional identity is a language-related teacher” and acknowledged a strong alignment with school expectations. However, 3 T also suggested that “there are a lot of vague expectations” from broad dimensions that are unclear and inconsistent.

The participants also confirmed that they have sufficient autonomy, with 1A reflecting that they can “still move things around … I have sufficient autonomy, and I can do what I want.” Further, 2B recognised that ‘we do have autonomy as much as the direction of the school

confines us.’ They would take cues from the administration to guide decision-making and practice. 3 T reported that such oversight is invasive in some situations, referring to administrative controls as “Big Brother” as teachers are committed to achieving explicit systemic guidelines. Hence, the feedback confirmed that CPD and development goals were a function of intra-institutional “requirements” (2B) and were “sufficient” (3 T) given the current state of change in the educational system. 3 T reported that they would also like to ‘have more autonomy in managing professional development to adapt more productivity to challenges and specific classroom needs.

6. Discussion

According to Garcia and Weiss (Citation2020), developmental effects are employed to shape self-identification and teacher competency positively. For instance, training and mentorships are relevant when facing systemic challenges like changing institutional conditions. Anderson et al. (Citation2021) reveal the critical role of positive self-efficacy in supporting teacher development. They emphasise the value of creativity, environmental support, encouragement, and training to assist in normalising the disruptive effects of the Covid-19 crisis through an empirical study of teacher experiences.

The study participants highlight the needs and expectations to adapt to changing digital education and organisational goals. Forces such as the willingness to change and teacher openness to new skills and responsibilities have been observed by Comas-Quinn and Comas-Quinn (Citation2011) to directly affect the success of transitions from traditional to blended or digital learning. Similarly, Wyatt (2020) recognises that teacher self-efficacy through confidence and capacity as a result of training and development is essential to developing metacognitive capacities to engage students in digital learning environments. Lo (Citation2020) also observed how teachers could utilise communities of practice to exchange lecture materials and model teacher-student interactions with other professionals. Teachers can leverage ambiguity and systemic incongruities manifest (e.g., Mose, Citation2020), the support and guidance of professionals within and outside a given institution to inform teacher decision-making and support.

Nonetheless, Berry (Citation2020) reported an array of emotional and psychological burdens confronting teacher self-assessment and self-identification to reconcile the challenges of a Covid-19 teaching environment. From specific roles and responsibilities to more complex considerations such as teaching effectiveness and knowledge transfer, the uncertainty and unfamiliarity underscoring this highly volatile period of transition have had a direct impact on

perceptions of personal and professional needs (e.g., training, support, time off, health, guidance, motivation; Berry, Citation2020). However, Rudick and Dannels (Citation2020) observed that the discourse surrounding educational roles and responsibilities shifted towards technological capabilities and teacher roles. Besides, other considerations related to teaching effectiveness and pedagogy were gradually left behind. While the participants’ feedback in this study suggests that there is a motivation for teachers to continue to hone their pedagogical skills in the future, without revising the programme design and redefining the functional priorities of CPD, teacher roles and identity remain ambiguous and uncertain.

The researcher observed challenges concerning the pressures placed upon teachers during Covid-19 to maintain student interest and engagement without sufficient resources, technological skills, or capabilities to meet the changing requirements. In the future, student engagement and creativity will play a direct role in shaping pedagogical strategies and digital communication techniques in digital learning applications (McWilliam & Dawson, Citation2008). Therefore, Ellis et al. (Citation2020) have reported that efforts to curb frustration of system inefficiencies through temporary interventions will not have a meaningful effect on teaching quality over the long term. The participants in this study have further confirmed that there is an immediate need for developmental solutions specifically oriented towards teacher experiences, responsibilities, and roles within the evolving digital or hybrid educational programme.

One of the challenges identified by the interview participants is that the rigidity of the CPD solution negates individual interests. However, it focuses on narrow administrative goals and standardised skill sets. The programme “inferiority” question raised by Watermeyer et al. (Citation2021, p. 631) is associated with the total adjustment in teacher responsibilities and the transition from knowledge sharing and downstream communication to technological moderators and assessors. Suppose digital learning forms the basis for resource and knowledge exchange. In that case, the role of the teacher in any secondary educational setting is transformed into one moderator or support agent, threatening the paradigm of teaching itself as systems continue to evolve digitally. In EFL courses, empirical evidence presented by Hazaymeh (Citation2021) and Oraif and Elyas (Citation2021) confirms that digital educational systems can have positive and sustaining effects on student learning outcomes, particularly when immersive and diverse knowledge resources are integrated with qualified and creative professionals.

Furthermore, Lee et al. (Citation2021) proclaim that the advent of Covid-19 has improved hygiene habits and risk perception among teachers and students. The pandemic has positively influenced the teachers’ ability to handle any crisis within the learning environment. Janssen et al. (Citation2020) also highlight that the positive impact was reflected in the students and their parents when they would take in collective responsibilities at home. It includes e-learning and obtaining relevant feedback on their progress. The enhanced relationship between parents and their children lessens the burden for teachers to teach students all the social skills. Thus, the teachers get the chance to mould a functional identity that propels learning in Hong Kong secondary schools.

6.1. Limitations and future research

Various limitations are observed during the research process. First, the secondary sources of information used in qualitative research presented literature on the efficiency of professional development approaches to secondary school teachers in Hong Kong. Future research can employ effective approaches that will delve into the practical techniques to promote the relevance of continuous professional development.

Secondly, the interviewees did not highlight the practical impact of ICT on fostering teacher identity. The research paves the way for evaluating the impact of implemented ICT- based solutions for CPD. Future research can identify the impact of developed teacher identity in their instruction and evaluate the impact by assessing the students’ outcomes and relevance to solving the social challenges in Hong Kong.

7. Conclusion

The primary aim of this research was to critically assess the factors shaping post-Covid- 19 identity formation amongst secondary school teachers in Hong Kong. It is also intended to determine the influence of CPD and systemic needs on teacher role perceptions and goal-setting. It is conclusive that Hong Kong secondary education must include ICT-related solutions in its CPD to address the systemic gaps and skill-based deficiencies encountered by educators during Covid-19. These developmental solutions must weigh key considerations surrounding student learning in a digital environment, including support, socio-emotional challenges, technical competency, and innovative teaching strategies or techniques. The educators interviewed for this study have confirmed a positive orientation to improve techno-pedagogical education. However, future initiatives must target specific deliverables, capabilities, and skill-sets to alleviate the uncertainty and systemic gaps that have previously impacted teacher performance and student support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Anderson, R. C., Bousselot, T., Katz-Buoincontro, J. K., & Todd, J. (2021). Generating buoyancy in a sea of uncertainty: Teachers’ creativity and well-being during the Covid-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1–32. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.614774

- Babbie, ER. (2015). The practice of Social Research. (4th Edition) Boston, MA: Cengage Learning. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

- Berry, K. (2020). Anchors away: Reconciling the dream of teaching in Covid-19. Communication Education, 69(4), 483–490. https://doi.org/10.1080/03634523.2020.1803383

- Bryman, A. (2015). Social Research Methods (4th) ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Choate, K., Goldhaber, D., & Theobald, R. (2021, April). The effects of Covid-19 on teacher preparation. Kappan, 102(7), 52–57. https://doi.org/10.1177/00317217211007340

- Colliander, H. (2019). Being transformed and transforming oneself in a time of change: A study of teacher identity in second language education for adults. Studies in the Education of Adults, 51(1), 55–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/02660830.2018.1526447

- Comas-Quinn, A. (2011). Learning to teach online or becoming an online teacher: An exploration of teachers’ experiences in a blended learning course. ReCall, 23(3), 218–232. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0958344011000152

- Creswell, J. W., & Clark, V. L. P. (2017). Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research (3rd) ed.). Sage Publications.

- Donitsa-Schmidt, S., & Ramot, R. (2020). Opportunities and challenges: Teacher education in Israel in the Covid-19 pandemic. Journal of Education for Teaching, 46(4), 586–595. https://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2020.1799708

- Ellis, V., Steadman, S., & Mao, Q. (2020). Come to a screeching halt: Can change in teacher education during the Covid-19 pandemic be seen as innovation? European Journal of Teacher Education, 43(4), 559–572. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2020.1821186

- Flores, M. A., & Swennen, A. (2020). The Covid-19 pandemic and its effects on teacher education. European Journal of Teacher Education, 43(4), 453–456. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2020.1824253

- García, E., & Weiss, E. (2020). How teachers view their own professional status: A snapshot. Phi Delta Kappan, 101(6), 14–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/0031721720909581

- Glaser, B. and Strauss, A. (2012) The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Aldine Transaction, New Brunswick.

- Hammersley, M., & Trainor, A. (2012). Ethics in Qualitative Research: Controversies and Contexts. Sage Publications.

- Hazaymeh, W. A. (2021). EFL students’ perceptions of online distance learning for enhancing English language learning during covid-19 pandemic. International Journal of Instruction, 14(3), 501–518. https://doi.org/10.29333/iji.2021.14329a

- Hidalgo-Andrade, P., Hermosa-Bosano, C., & Paz, C. (2021). Teachers’ mental health and self- reported coping strategies during the Covid-19 pandemic in Ecuador: A mixed-methods study. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 14, 933–944. https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S314844

- Janssen, L. H., Kullberg, M. J., Verkuil, B., Van Zwieten, N., Wever, M. C., Van Houtum, L. A., Wentholt, W. G., Elzinga, B. M., & Cimino, S. (2020). Does the COVID-19 pandemic impact parents’ and adolescents’ well-being? An EMA study on daily affect and parenting. PLOS ONE, 15(10), e0240962. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0240962

- Jonker, J., & Pennink, B. J. W. (2010). The Essence of Research Methodology: A Concise Guide for Master and Ph.D. Students in Management Science. Springer Verlag.

- Kahiigi, E. K., Danielson, M., Hanson, H., Ekenberg, L., & Tusubira, F. F. (2009). Criticism of e-learning adoption and use in developing country contexts. IADIS International Conference e-Learning 2009. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/270157569.Criticism_of_elearning_Adoption_and_Use_in_Developing_Country_Contexts

- Kim, L. E., Leary, R., & Asbury, K. (2021). Teachers’ narratives during Covid-19 partial school reopenings: An exploratory study. Educational Research, 63(2), 244–260. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131881.2021.1918014

- Kodrle, S., & Savchenko, A. (2021). Digital educational media in foreign language teaching and learning. E3S Web of Conferences.

- Lanford, M. (2016). Perceptions of higher education reform in Hong Kong: A glocalisation perspective. International Journal of Comparative Education and Development, 18(3), 184–204. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijced-04-2016-0007

- Lau, E. Y., & Li, J. (2021). Hong Kong children’s school readiness in times of COVID-19: The contributions of parent perceived social support, parent competency, and time spent with children. Frontiers in Psychology, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.779449

- Law, V. T., Yee, H. H., Ng, T. K., & Fong, B. Y. (2022). The transition from traditional to online learning in Hong Kong tertiary educational institutions during the COVID-19 pandemic. Technology, Knowledge, and Learning. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10758-022-09603-z

- Lee, A., Keung, V. M., Lau, V. T., Cheung, C. K., & Lo, A. S. (2021). Impact of COVID-19 on the life of students: A case study in Hong Kong. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(19), 10483. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph181910483

- Lo, N. P. K. (2020). Revolutionising language teaching and learning via digital media innovations. In Will W.K. Ma, Kar-wai Tong, & Wing Bo Anna Tso (Eds.) Learning environment and design (pp. 245–261). Springer.

- Marschall, G. (2021). The role of teacher identity in teacher self-efficacy development: The case of Katie. Journal of Mathematics Teacher Education. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10857-021-09515-2

- McWilliam, E., & Dawson, S. (2008). Teaching for creativity: Towards sustainable and replicable pedagogical practice. Higher Education, 56(6), 633–643. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-008-9115-7

- Merriam, S. B. (2015). Qualitative Research: A Guide to Design and Implementation (4th) ed.). Jossey-Bass.

- Morgan, D. (2014). Follow-up quantitative extensions to qualitative research projects. SAGE Publications, Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781544304533

- Morgan, D. L. 2014. Integrating qualitative and quantitative methods: A pragmatic approach. SAGE Publications, Inc.

- Mose, L. (2020). Navigating Covid-19 in higher education: The significance of solidarity. Communication Education, 69(4), 532–533. https://doi.org/10.1080/03634523.2020.1804131

- Murphy, M. P. A. (2020). Covid-19 and emergency eLearning: Consequences of the securitization of higher education for post-pandemic pedagogy. Contemporary Security Policy, 41(3), 492–505. https://doi.org/10.1080/13523260.2020.1761749

- Oraif, I., & Elyas, T. (2021). The Impact of COVID-19 on Learning: Investigating EFL Learners’ Engagement in Online Courses in Saudi Arabia. Education Sciences, 11(3), 99. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11030099

- Poon, A. Y. K., & Wong, Y. -C. (2008). Education Reform in Hong Kong: The “Through-Road” Model and Its Societal Consequences. International Review of Education / Internationale Zeitschrift Für Erziehungswissenschaft / Revue Internationale de l’Education, 54(1), 33–55. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27715432

- Punch, K. (2014). Introduction to Social Research: Quantitative and qualitative approaches (3rd) ed.). Sage Publications.

- Reynolds, N. L., Simintiras, A. C., & Diamantopoulos, A. (2002). Theoretical justification of sampling choices in international marketing research: Key issues and guidelines for researchers. Journal of International Business Studies, 34(1), 80–89. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8400000

- Rudick, C. K., & Dannels, D. P. (2020). Yes, and continuing the scholarly conversation about pandemic pedagogy. Communication Education, 69(4), 540–544. https://doi.org/10.1080/03634523.2020.1809167

- Schwartzman, R. (2020). Performing pandemic pedagogy. Communication Education, 69(4), 502–517. https://doi.org/10.1080/03634523.2020.1804602

- Skott, J. (2018). Changing experiences of being, becoming, and belonging: Teachers’ professional identity revisited. ZDM, 51(3), 469–480. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11858-018-1008-3

- Van Lankveld, T., Schoonenboom, J., Volman, M., Croiset, G., & Beishuizen, J. (2016). Developing a teacher identity in the university context: A systematic review of the literature. Higher Education Research & Development, 36(2), 325–342. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2016.1208154

- Van Nunland, S., Mandzuk, D., Petrick, K. T., & Cooper, T. (2020). Covid-19 and its effects on teacher education in Ontario: A complex adaptive systems perspective. Journal of Education for Teaching, 46(4), 442–451. https://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2020.1803050

- Watermeyer, R., Crick, T., Knight, C., & Goodall, J. (2021). Covid-19 and digital disruption in UK universities: Afflictions and affordances of emergency online migration. Higher Education, 81(3), 623–641. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-020-00561-y

- Watkins, D., & Gioia, D. (2015). Mixed methods research. Oxford University Press.

- Wyatt, M. (2014). Towards a re-conceptualization of teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs: Tackling enduring problems with the quantitative research and moving on. International Journal of Research & Method in Education, 37(2), 166–189.