Abstract

Speaking in a foreign language is considered challenging to both teach and learn. Virtual humans (VHs), as conversational agents (CAs), provide opportunities to practise speaking skills. Lower secondary school students (N = 25) engaged in an AI-based spoken dialogue system (SDS) and interacted verbally with VHs in simulated everyday-life scenarios to solve given tasks. Our analysis is based on system-generated metrics and self-reported experiences collected through questionnaires, logbooks, and interviews. Thematic analysis resulted in seven themes, revolving around the speaking practice method, scenarios and technology, which, in combination with descriptive statistics, enabled a deeper understanding of the students’ experiences. The results indicate that, on average, they found it easy, fun, and safe, but sometimes frustrating in scenarios not always relevant to their everyday lives. Factors suggested as underlying the levels of experienced frustration include technical issues and constraints with the system, such as not being understood or heard as expected. The findings suggest that lower secondary school students conversing with VHs in the SDS in an institutional educational context facilitated a beneficial opportunity for practising speaking skills, especially pronunciation and interaction in dialogues, aligning with the key principles of second language acquisition (SLA) for language development.

Public interest statement

This paper reports on a study where students (N = 25) practised speaking English face-to-face with embodied virtual humans in a system. They solved tasks in everyday-life scenarios, e.g., ordering at restaurants. Our analysis is mainly based on the students’ self-reported experiences produced through questionnaires, logbooks, and interviews, but also some logged data about their activity and performance in the system. We identified seven themes, revolving around the speaking practice method, scenarios, and technology, which, in combination with descriptive statistics, enabled a deeper understanding of the students’ experiences. Results indicate that, on average, they found it easy, fun, and safe but sometimes frustrating practising in scenarios with content not always relevant to their everyday lives. Factors suggested as underlying the levels of experienced frustration include technical issues and not being understood or heard as expected. The findings implicate beneficial opportunity for practising speaking skills, especially pronunciation and interaction in dialogues.

1. Introduction

Speaking is emphasised in today’s communicative language teaching approach (Byram & Méndez, Citation2011; Council of Europe, Citation2020), highlighting oral communication in the target language for meaningful purposes in everyday-life situations. Hence, interaction plays a crucial role in foreign language development and learning (Loewen & Sato, Citation2018). It has been found that the teaching of speaking skills does not match the communicative approach (Adem et al., Citation2022) and that it is difficult to approach it in pedagogically sound ways (Goh & Burns, Citation2012). Foreign language teachers have internationally ranked speaking as the most important skill (to teach and to learn; Thiriau, Citation2017), which coincides in general with how students measure, value and align their success in language learning with their mastery of speaking skills (Darancik, Citation2018). However, there are limited opportunities to effectively practise speaking the target language in education, and little access to it outside the classroom. Additionally, speaking is considered particularly complex to learn and frustrating due to its sense of transience (Goh & Burns, Citation2012). Spoken interaction is cognitively and socially demanding, creating underlying mental and emotional barriers such as anxiety and a lack of confidence (Burns, Citation2016).

Practising speaking skills with embodied chatbots (Wang et al., Citation2017), also known as virtual humans (VHs; Schroeder & Craig, Citation2021), in a virtual learning environment, has been proposed as one possible way to address these teaching and learning challenges and provide possibilities for speaking practise (Johnson, Citation2019; Sydorenko et al., Citation2018). VHs add a social dimension and can broadly be described as human-like and artificially intelligent characters (Burden & Savin-Baden, Citation2020; Fryer et al., Citation2019), visually represented or face-to-face interaction in simulations (Johnson & Lester, Citation2016). VHs have human characteristics and behaviours, including social cues using facial expressions, gestures, and body movements. The VH actions can be controlled either by a human or by the system autonomously (Schroeder & Craig, Citation2021) when acting as the counterpart, that is, a conversational agent (CA; Burden & Savin-Baden, Citation2020) in spoken interaction. Such spoken dialogue systems (SDSs; Bibauw et al., Citation2019) use natural language processing technology to interpret the speech of students and produce relevant responses (Griol & Callejas, Citation2016). Although it is a promising technology (Golonka et al., Citation2014), there are few studies exploring its experienced use in actual language teaching and learning, i.e., as supplement in an institutional foreign language education (Bibauw et al., Citation2019). To fill this gap, this paper reports on a study exploring the use of system-controlled VHs in verbal face-to-face situations in which Swedish lower secondary school students practised speaking English as a foreign language in simulated scenarios. We focus on the subskill interaction outlined by Li (Citation2017), including interrelated skills such as the production of utterances to maintain a fluent verbal conversation and listening comprehension (Hodges et al., Citation2012).

2. Background

In this section, we delineate the theoretical framing of the study, followed by related literature from the field before presenting the study goals and the questions guiding the research. Finally, we provide a brief description of the context and roles of the researchers.

2.1. Learning to speak a foreign language

Analytically, language learning is understood as framed by social contexts and interactions between people (Swain, Citation2000). Hence, this study is anchored in a sociocultural perspective on learning and development as the increased ability to participate in relevant ways in different social interactions (c.f., Lantolf et al., Citation2014; Vygotsky, Citation1978). The theoretical foundation of the study is inspired by the pedagogical approach that integrates learning through practice, as proposed by Chapelle (Citation2009), with the active use of the target language in task-based teaching and learning (Blake, Citation2017), in line with the communicative approach. It is important that the student be exposed to the language and given opportunities for spontaneous conversational interaction, including key principles such as “authentic input, conscious noticing on form, opportunity for interaction, in-time and individualised feedback, low affective filter and an environment where language can be used” (Li, Citation2017, p. 28), along with an adequate level of scaffolding and guidance (Goh & Burns, Citation2012). Furthermore, Swain (Citation2013) pointed out the need for the field to consider the role of emotions as one aspect affecting the language learning process. Individual differences in the affective filter, such as levels of anxiety and self-confidence, speaking skills, and motivation to speak the target language, all influence speaking ability (Goh & Burns, Citation2012; Li, Citation2017).

2.2. DB-CALL

In their review, Bibauw et al. (Citation2019) found studies of dialogue-based computer-assisted language learning (DB-CALL) dispersed and fragmented and suggested a conceptual framework for the combined research in this field. DB-CALL assumes that meaningful efforts in the target language in verbal contextualised conversations with the computer as an automated interlocutor develop learners’ language skills, in contrast to computer-mediated communication through the computer (Blake, Citation2017). In this case, the pragmatic unit of instruction is the dialogue, consisting of turn-taking between the system or, more precisely, the embodied CA and the student, where the dialogue is the actual task. Automatic speech recognition is used to recognise and analyse what the students say through natural language processing and to converse with them by means of a synthesised voice (Griol & Callejas, Citation2016) in the target language (native speaker). Consequently, Long’s interaction hypothesis (1996), supporting the negotiation of meaning, the importance of opportunities for output, and receiving comprehensible input and feedback, is a prominent foundation for designing such SDSs, as suggested by Morton and Jack (Citation2005). We still know little about the implications of interaction in this kind of new context for L2 development (Loewen & Sato, Citation2018).

2.2.1. Developing speaking skills with CAs in SDSs

Chatbots and human-like embodied VHs (Huang et al., Citation2022) are increasingly available as CAs for providing conversation practice, pronunciation (Kukulska-Hulme & Lee, Citation2020), and vocabulary learning, but they are still scarcely used in the institutional educational context as supplements for teaching speaking. By engaging with CAs, students can practise speaking the target language repeatedly and with feedback from the system (Doremalen et al., Citation2016; Fryer et al., Citation2019), allowing access anywhere and at any time (Huang et al., Citation2022), without travelling abroad. CAs are found to be mostly useful for language learning, with technological, pedagogical, and social affordances highlighted, such as ease of use, personalisation, authentic simulations, and keeping conversations fluent (Jeon, Citation2022). Technological limitations affect students very differently (ibid), sometimes causing frustration but still making students mostly willing to engage in conversations (Alm & Nkomo, Citation2020). Drawbacks reported include CAs’ lack of emotions and visible cues and their inability to confirm understanding (Jeon, Citation2022). The systems’ constraints on understanding several utterances in a row are identified as a challenge, together with a restricted conversational path, due to the lack of negotiation of meaning that we would normally see in a human-to-human conversation (Bibauw et al., Citation2019). Hence, CAs still have some way to go before being sufficiently robust, as suggested earlier by Coniam (Citation2008).

Research shows that SDSs have the potential to enhance language learning since they allow for meaningful everyday-life speaking activities with CAs (e.g., Anderson et al., Citation2008; Doremalen et al., Citation2016; Hassani et al., Citation2016; Johnson, Citation2019). Progress pointing towards an enjoyable and non-threatening use of CAs in everyday-life contexts is also suggested in systems like Mondly and Duolingo (Alm & Nkomo, Citation2020). It is envisioned that student engagement and acceptance could be facilitated by placing the educational activities in virtual reality, supporting experiences of immersion and the sense of being somewhere else (Kaplan-Rakowski & Wojdynski, Citation2018; Wang et al., Citation2017), hence enhancing the development of speaking skills (Morton & Jack, Citation2005). Divekar et al. (Citation2021) used a multimodal SDS with extended reality and AI-empowered CAs and showed statistically significant improvements in students’ vocabulary learning, listening comprehension, and speaking. Moreover, Johnson and Lester (Citation2016) argued that interacting with CAs in virtual reality environments facilitates cultural learning.

Studies of the use of SDSs conducted in higher education in relation to the learning outcomes of the students’ speaking ability have demonstrated a greater impact on beginner- to intermediate-level students than on advanced-level students (Kim, Citation2016). Contrastingly, Sydorenko et al. (Citation2018) suggested that students with more advanced proficiency levels of the target language may benefit more from simulated interactions due to their ability to listen and understand the interlocuter’s utterances. Anderson et al. (Citation2008) also demonstrated engaged and less stressed adolescent students interacting with embodied VHs and finding it useful and fun. SDSs have been shown to enable a low-anxiety learning environment (e.g., Anderson et al., Citation2008; Morton & Jack, Citation2005), influencing students’ willingness to communicate (Ayedoun et al., Citation2015; Divekar et al., Citation2021). Reduced anxiety over speaking has been found and explained, for instance, by SDSs that provide enjoyable and less stressful speaking practises (Bashori et al., Citation2020, Citation2021). The independence of conversing with a CA alone was reported to be beneficial for learning, with the text-to-speech function mentioned as a merit of the system but nevertheless not able to fully replace human beings in dialogues (Gallacher et al., Citation2018). Subsequently, there has been scepticism about incorporating CAs into institutional language education settings.

2.3. Aim & research questions

In summary, even though the field has looked at learning effects, students’ attitudes, and experiences of using SDSs, there is a lack of studies outside of higher education as well as of SDSs used in non-experimental institutional educational activities, in particular SDSs with VHs. Therefore, this study was designed to be a regular part of learning a second language (L2), and it was conducted in a lower secondary school. This study aims to explore the perspectives of lower secondary school students on practising their foreign language speaking skills through verbal interactions with VHs in an SDS. One way to explore this is by tapping into the students’ self-reported experiences (affective, cognitive, and educational aspects) of practising in the system. The study is guided by the following research questions:

How do students in lower secondary school practise speaking English in an SDS with VHs ?

What factors can be identified as the basis for any variations in the group’s overall experience?

2.4. The role of the researchers

The first author of this paper initiated, designed, and conducted the study under the supervision of the co-authors, who participated in the preparation phases, the analysis of the data, and the writing process of this paper. The first author distributed the logbook and the questionnaires used in the study and conducted the interviews. The relationship to the inquiry is our interest in understanding the possibilities and challenges of educational technology and its application in the (foreign language) classroom, focusing on the students as users and their experiences.

3. Methods

This section describes the roles of the researcher and the participants. Next, the design of the study, including the system used and the instruments applied for producing data in the procedure, is presented. Finally, the steps undertaken in the two-fold analysis are outlined.

3.1. Participants

A language teacher for a class (N = 25) of 12 girls and 13 boys aged 13 to 14 years, and the class itself all agreed to use the system as part of their institutional education. The type of sampling was convenience (Creswell & Creswell, Citation2018), with the participants selected based on availability. The students studied English as a foreign language at an approximate beginner level (A1–A2, for more information, see, Council of Europe, Citation2020), according to the teacher’s assessment in the seventh grade at a lower secondary school in a suburb of a large city in Sweden. The characteristics of the students relevant to the study are described in Section 4.1

3.2. Study design

This study mainly explored the students’ self-reported experiences, as suggested by Levy (Citation2015), to tap into the students’ perspectives. In addition, the study identified the differences within the group, as suggested by Schroeder et al. (Citation2021) for educational research on VH, rather than the traditional between-group experimental design. To more fully understand how the students experienced practising speaking in the system, the study employed posttrial questionnaires, logbooks, semi-structured interviews, and system-generated metrics, combining both qualitative and quantitative data, as suggested by Bergman (Citation2008) and Creswell and Creswell (Citation2018). These multiple sources enabled triangulation for a deeper understanding.

The decision to use a questionnaire was motivated as an effective way of gathering data about the students’ self-reported experiences in the system (posttrial) and background information (pretrial), complemented with logbooks for their reflections and ratings instantly after the speaking session. The interviews provided the possibility to deepen understanding, and metrics were more of an objective way of measuring performance and activity in the system. Since the experiences of the student–VH spoken interaction are not shared reciprocally in the same way as in human-to-human interaction, it is not yet possible to ask these VHs to reflect and report on their experiences (c.f., about VHs’ minds in Burden & Savin-Baden, Citation2020); hence, our instruments are one possible way to approach the new learning situation. The analysis is based primarily on the students’ self-reported experiences, including affective, cognitive, and educational aspects of practising a foreign language in this virtual environment. The SDS was selected based on the criteria for enabling spontaneous interaction in the target language with a VH.

Analytically, the students and the SDS are viewed as constituting the learning situation, which also includes the classroom, the teacher, and the curriculum, although data on the physical environment and the school’s pedagogical perspective were not collected. The teacher and a teacher trainee were, however, included in the semi-structured interviews aimed at gaining insights into their views of the students’ experiences. The responses provided insights into the educational situation. The role of the researcher (first author) in the study was to present the aim of the study and to introduce the system together with the teacher, who acted as a facilitator during the trial. The VHs guided and instructed the students within the system, which also provided text-based instruction. The students were instructed to engage in the speaking activities, to use the various supporting features, and to visit the learner’s dashboard (Section 3.3).

3.3. Spoken Dialogue System (SDS)

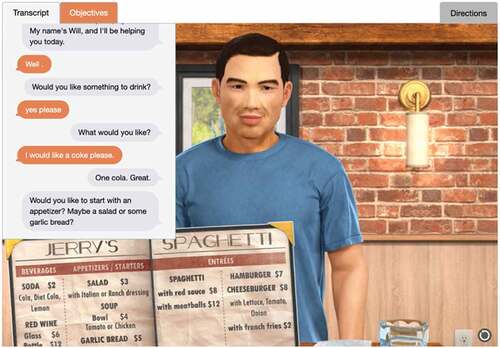

The speaking sessions took place in Enskill (Alelo, Citationn.d.; beta version) and sought to achieve realistic interaction in English to develop the students’ (interactional skills. The system and the student took turns such that both the student and the VH could be the initiators and solve different tasks together. The conversations simulated everyday-life scenarios with an action-oriented approach, in which the students’ task was to solve practical problems, such as ordering food at a restaurant or giving directions. The VHs are animated and embodied female or male characters (see, Figure ), who act as human counterparts in the dialogues. Figure illustrates a system-generated transcript in which VH Lily and a Swedish student engaged in a spoken conversation.

Figure 1. Screenshot of the VH (upper left) and the practising student (upper right), along with a transcript from a VH–student (S) verbal interaction in Enskill (Alelo, Citationn.d.).

The students practised English at the A1 and A2 levels (for more information, see, Council of Europe, Citation2020). Students’ utterances are registered and analysed in the system by applying automatic speech recognition and language technology (Johnson, Citation2019). The students can express themselves spontaneously, and the system is not dependent on predetermined responses. However, there are some constraints, such as the context, that keep conversational freedom within bounds and guide the conversation along pre-set paths. Students are enabled to take alternative paths to solve the task. They could also choose various supporting features, such as displaying the learning objectives, providing transcripts (text-to-speech) of the ongoing conversation (see, Figure ), and providing directions (suggestions for the next action and utterance). It is not possible to change the speed of VH’s speech or the variety of American English

Figure 2. Screenshot of a student’s view with a prompt to order food at a restaurant, displaying the transcript.

To solve a task, the students must accomplish certain goals (learning objectives) during the conversation (see, Figure ). Instantly after the spoken dialogue, auto-generated individualised feedback is provided with adapted instruction, suggesting adequate follow-up exercises (if needed). The students can choose to repeat the same conversation until they have fulfilled all learning objectives and feel satisfied with the results. The SDS includes an individual student dashboard (beta version) showing the results and mastery score based on learning analytics, such as time, accuracy, and turns per minute.

3.4. Data production

To explore students’ experiences, the study analysed data produced in system-generated metrics, questionnaires, logbooks, and interviews. The metrics are logged data about the students’ speaking activity and performance in the system. They displayed students’ fulfilled learning objectives, simulation, time spent, and mastery scores (based on accuracy, fluency and turns per minute). The system also generated transcripts of the conversations.

Two questionnaires were constructed and conducted digitally, drawing on previous questionnaires evaluating Enskill (Johnson, Citation2019) and with inspiration from the research project teaching, assessment, and learning (TAL) on oral proficiency in foreign language education (Erickson et al., Citation2022). Speaking was divided into three subskills in this context: pronunciation, producing one’s own utterances, and interaction (ibid.). The study’s questionnaire used a similar five-point Likert scale (Creswell & Creswell, Citation2018), sometimes followed by optional open-response items, as well as multiple-choice items (Brown, Citation2009). We adapted vocabulary to the age group, and “avatar” was used equivalent to VH (still controlled by the system). This study’s pretrial questionnaire (N = 25) for background information reported on the students’ self-assessed views of learning and speaking English in an institutional educational setting and their experience of using digital educational tools. The posttrial questionnaire (N = 23) reported primarily on the students’ experiences of practising speaking English with VHs in the SDS, the benefits and limitations experienced, as well as suggestions for improvement and, finally, the students’ own evaluation of their learning and speaking English.

In a separate digital logbook, the students (N = 22) documented their experiences (today’s practice, challenges, and benefits). In addition, semi-structured posttrial interviews were conducted with six volunteer students until data saturation was reached to deepen our understanding of the learning situation based on their experiences. An interview guide was used, with pictures representing experiences using the system. Pre- and posttrial interviews were conducted with the teacher and a teacher trainee. All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

3.5. Procedure

The study has been guided by ethical research practice principles (Swedish Research Council, Citation2017), including personal privacy compliance (GDPR, Citation2018). Once the students (and their legal guardians) had consented to participate in the study, their teacher and the first author researchers introduced it and demonstrated the system. Each student was equipped with a headset with a microphone and an account with an anonymised login to use on their laptop. Before starting the trial, the students answered the pretrial questionnaire. The trial covered four 15-minute sessions (total 60 minutes) over two weeks. The students chose from among 10 conversational scenarios per level. Unpredicted technical issues with the system (for example, software bugs) occurred randomly and were solved continuously. Directly after each speaking session, the students reflected individually by writing in the logbook for approximately five minutes. After the trial period, they filled out the posttrial questionnaire and were interviewed until data saturation was reached.

3.6. Analysis

The metrics from the system and questionnaire ratings were analysed through descriptive statistics. Data from the open-response items of the posttrial questionnaire, written logbook reflections and transcripts from semi-structured interviews were analysed in two ways: (i) through reflexive thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006, Citation2019) on the students’ experiences and (ii) by exploring the variations in the overall experience within the group to identify possible patterns and subgroups.

In the thematic analysis, the data were coded systematically, with collegial consensus to ensure reliability. A combination of data-driven (inductive) and theory-driven (deductive) approaches was used, and seven themes were developed in relation to the research questions. We refined these themes during the analysis and gave them illustrative titles. For further depth, as suggested by Brown (Citation2009), we added representative quotes (after translation) from the student reflections.

To explore the variations within the group, the complete data set was analysed at an individual level to obtain a broad experience profile for each student. These profiles were then clustered into three subgroups (positive, neutral, and negative) showing the degree of positivity versus negativity towards practising speaking. Group membership was subsequently related to their engagement in the system, measured through metrics (time spent and learning objectives), and analysed in correlation plots.

Data produced from the pretrial questionnaire (N = 25) were analysed using descriptive statistics for background information about the participating students. The system-generated transcripts of the VH–student conversations were read to select an illustrative excerpt (see, Figure ).

4. Results

This section presents background information about the students, logged data (metrics) on their activity in the system, and their overall experience based on ratings and open-response items posttrial. Additionally, it outlines three clustered subgroups of students (positive, neutral, and negative) and the association established between the students’ membership in the subgroup and their engagement with the system (time spent and learning objectives fulfilled).

4.1. Background information

The participating students reported spending an average of eight hours on digital devices daily, including schoolwork using digital educational tools. Many students reported in the pretrial questionnaire that learning English is generally fun and easy. However, a quarter of the students were dissatisfied with the frequency of opportunities to speak English during lesson time and identified this as the skill with the least opportunity for practice. The main obstacles to speaking English reported were a lack of confidence and anxiety.

4.2. Speaking activity (Metrics)

Metrics reports generated in the system revealed that all students (N = 25) started simulations, with 16 of the students’ making attempts at both the A1 and A2 levels. The mean value per person of the total time spent on activities at both levels was 44 minutes and 13 seconds (Table ). The minimum time spent (one second) was explained by starting a simulation without proceeding. The scenarios chosen most frequently were the planning of a party, followed by ordering at a restaurant.

Table 1.. Metrics reports from trials

4.3. Overall experience—easy, fun, and average realistic practice of speaking skills (ratings)

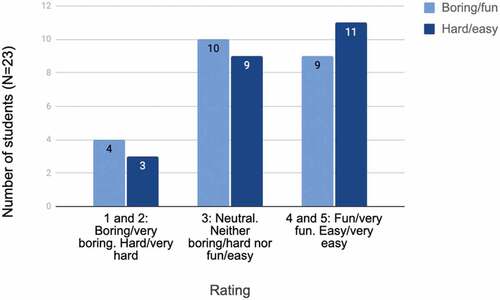

The posttrial questionnaire ratings revealed that most of the students were neutral or positive about practising speaking English with a VH, regarding both how easy (48%) and how fun (40%) it was (see, Figure ).

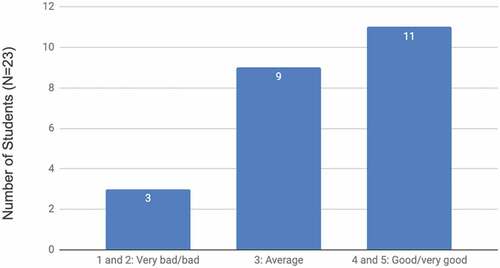

Almost half of the students found the threshold low to start using the system (48%). In addition, 11 students (48%) reported that overall, they experienced the system as good for practising speaking English (see, Figure ).

The students did not consider the scenarios very realistic (as in “real life”), with the mean rating value being 2.48. The most common answer was “average”, and 43.5% of them thought the tasks were “not realistic at all” or “only slightly realistic”. Overall, taking in all statements and evaluating the method of practising in relation to the development of speaking skills resulted in an average median value of 3 (see, Table ).

Table 2.. Students’ ratings of self-evaluative and overall experiences

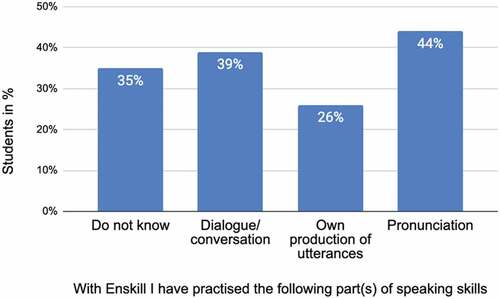

The students’ self-assessment of what subskills they practised revealed that they mostly experienced pronunciation (44%), closely followed by dialogue/conversation (39%). However, around a third (35%) had difficulty assessing which subskills they had practised, as illustrated in Figure .

Concerning the supportive features, only some students reported having used the system’s transcript feature, and only a few looked at the learner’s dashboard and practised the adapted follow-up exercises, despite being repeatedly encouraged to do so.

4.4. Overall experience with method, scenarios, technology, and design (open-response items)

Based on open-response items, the thematic analysis revealed seven themes revolving around the students’ self-reported experiences of the speaking practice method, the content of the scenarios, and the technology and design of the system. Most of the coded data were distributed within themes about the technology, mostly about not being understood or heard, resulting in repetitive VHs, hang-ups and bugs in the system.

4.4.1. Easy, fun, and innovative

The students expressed that it was “easy”, “smart”, “exciting”, “fun”, “nice”, and “a good way” of practising speaking and learning English: “Very good and this was fun and I’m very excited to continue” (Student 11). Comments included this is “an innovative way of teaching English” (Student 5) and “I liked it a lot. It was fun and nice trying a new thing, and I enjoyed it” (Student 9).

4.4.2. Learning to speak, listen, and read

Some students reflected upon which skills they had learnt and developed: “One started to feel somewhat more comfortable speaking English” (Student 16) and “you learn words and how to speak” (Student 25). Furthermore, “I think you learnt a lot from this, since you were both speaking with an avatar (so you learn pronunciation), and at the same time as speaking, you also learn to read (if you have a text beside with what you are talking about)” (Student 17, student’s parentheses).

4.4.3. Less nervous and more comfortable

Many students reported feeling safe, “less nervous” and “more comfortable” speaking with a VH compared to speaking with other people in the classroom: “When you speak to an avatar you do not become nervous about saying something wrong. That is why I think this is good, since you learn speaking better without having to be nervous” (Student 17). The system was reported as a safer way of practising speaking English: “It is nice for many people who do not feel fully comfortable speaking with other people, so [it is] good to do this in advance so you can skip real-life conversations with human beings, but it is good to combine both” (Student 7). Additionally, this way of speaking gives you time to think: “You can train to have quicker answers when the avatar speaks, you can think through what to answer” (Student 11).

4.4.4. Human-like versus non-human-like interaction

Some students experienced the VH as more “human-like” and “real” compared to other systems:

The avatar felt like a human being; they spoke exactly like a normal human being and not like a robot, like Siri or something; this one spoke normally, which was nice. They put in scenarios in real life, so you have to say something like in a real conversation. Yes, they succeeded; it felt quite authentic indeed. (Student 9)

Aspects of humanising are interesting, and students’ referring to the VHs varied between “they,” “avatar(s),” “the figures,” “it,” “he,” “the man,” “she,” or using their human names: “I was talking with Emma about a soccer game (Student 11). However, there were large individual differences, and the VH was sometimes experienced as “strange,” feeling “kind of weird” compared with a machine: “Speaking to this avatar was good. But it is a little bit difficult because he is like a computer (Student 4). “It was not so realistic since you had to say: ‘No, I do not need any more’ … instead of just saying ‘no’ as you would say in a normal conversation” (Student 12). Frustration also arose around the repetitiveness of the interaction:

It should be more human to speak with and at least have more than one answer to answer with than ‘Can you please repeat that again?’ I was going to throw my computer out the window. You must be able to say that you want to book a train ticket or something in various ways, because [the interaction] does not work otherwise. (Student 15)

Many students reported that they gradually felt used to and more comfortable with this way of practising, indicating that it takes time: “Somewhat strange feeling at first, but you got used to it” (Student 7). “The final lesson, I have got more and more comfortable with time. I think you must take some time to get to know the programme” (Student 5).

4.4.5. Frustration when not being understood or heard by a limited system

Whereas the students experienced a good understanding of the VHs and that “(t)he voice of them sounded good and clear” (Student 20), they expressed frustration over not being understood or heard by the system: “Often when I speak, they say that I should repeat myself, and that is very annoying” (Student 21). “If you answer in another way than it says in the manual, then they say, ‘Can you say that again?’ It feels petrifying when you keep trying, but you do not know exactly what they want you to say” (Student 9). Students expressed repeated frustration over constraints in the system: “There were only a few answers to every question” (Student 11), “I can’t answer the way I want, and they can’t hear me” (Student 20), and “they didn’t answer the question I asked” (Student 2). Students also expressed frustration over the non-functioning “useless” system, constantly repeated technical issues and boredom: She or he just asked many boring questions and as I said it was very boring” (Student 20). Female students also reported that their voices were not as easily recognised by the system:” But we have concluded that it becomes more difficult for us girls, since it hears male voices better” (Student 22).

4.4.6. Quite realistic scenarios with preference for variation and age-adapted tasks

The sixth theme refers to tasks in the simulations and the extent to which they were experienced as realistic/relevant and useful. This student reported positively about the content: “For instance, there are such subjects that as a matter of fact can apply in real life, hence booking a hotel, interview, football game, etc., that you can really make big use of” (Student 17). Additionally, the students suggested more options to choose from, for instance, at the restaurant ordering various foods and not only spaghetti.

However, some students would have preferred it if the scenarios were more adapted to their age, as summarised by the teacher: “Linked to what young people are doing, their lives, hobbies, interests, conversation subjects, and so as authentically linked to their world as possible”. Furthermore, some comments reflected opinions about the content as preparation for the future and for travelling:

You learn about a lot of things here, about disco, food; if you are going on a trip to England or the USA, then you can practice and learn here beforehand. The situations were good. I missed something you do not learn in school, but need later in life, for instance, airports, something realistic, real life. (Student 9)

4.4.7. Suggestions

There was also feedback concerning the interface, such as optimising the tutorials and introduction to reduce the number of clicks and repetitive tutorials. Another idea was that the VH should give follow-up questions to deepen the conversation and vary the utterances used when not understanding. The teacher expressed a wish for a better match between the system and the Swedish curriculum, such as speaking and listening to global English with a variety of options; a wish also echoed in the students’ suggestions.

4.5. Three subgroups of students in relation to overall experience

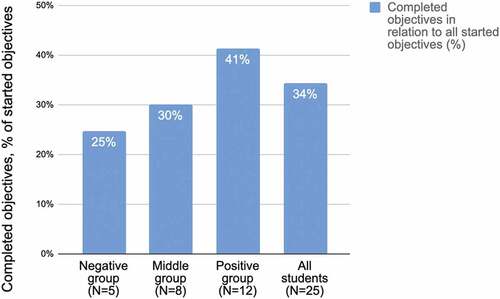

Three subgroups of students’ profiles were clustered according to a manual overview of their various posttrial ratings, open-response items, and reflection posts: negative (N = 5), neutral (N = 8), and positive (N = 12). In the correlation plots drawn, there was no association established between group membership with either self-reported pretrial views (on learning to speak and speaking English) or with time spent daily on digital devices. However, there was an association indicated between-group membership and time spent per person in the system, as well as with fulfilled learning objectives in relation to learning objectives started (see, Table and Figure ).

Table 3. Subgroups and all students’ time spent and performance in the system

This means that students’ overall experiences are reflected in their engagement with the system in terms of time spent, as well as their successful completion of learning objectives. For the negative group, reports of being bored and frustrated dominated the overall experience of the whole trial. These students showed little or no patience with the difficulties and even used inappropriate words.

5. Discussion

Triangulation through multi-methods showed how the students’ experiences mostly coincide with key principles that account for developing speaking skills successfully outlined by, for instance, Li (Citation2017). The way of practising is reported to provide opportunity for (human-like) interaction (Lantolf et al., Citation2014; Loewen & Sato, Citation2018), feeling comfortable (Li, Citation2017), practising speaking in the target language in a fun, safe and (Swain, Citation2013) active way through their practical everyday-life tasks and practice of pronunciation and dialogues (Blake, Citation2017). Having time to think before answering in the dialogue nuances the picture of speaking with VHs, signalling the practice as less stressful than human-to-human interaction. Furthermore, the students expressed requisites for variation and personalisation of the system according to their interests, age, and educational needs, highlighting in particular the importance of conversational themes associated with their everyday lives and interests (e.g., Li, Citation2017; Long, Citation1996), both current and for the future. This observed lack of relevant scenarios relates to the design of SDSs as educational tools regarding the audience they target, as this specific system was not designed with the Swedish lower secondary school student and curriculum in mind.

The participants’ variation in reported experiences in this study echoes previous findings in DB-CALL (see, e.g., Anderson et al., Citation2008; Jeon, Citation2022; Johnson, Citation2019), although the former studies were primarily conducted in higher education (Bibauw et al., Citation2019). The findings reported here nuance previous studies of VR-assisted language learning, highlighting the great potential for positive engagement (Anderson et al., Citation2008; Kaplan-Rakowski & Wojdynski, Citation2018) and acceptability when practising speaking skills with VHs in immersive scenarios (Wang et al., Citation2017). Our study observed a large variation in terms of both how the speaking practice and technology were experienced and the amount of effort each student put into the activity. The results also indicate that students adapt differently to the VHs’ conversational strategies, experiencing that they are not always appropriate or aligned with the students’ expectations. The way the students in this study experience the VH possibly reveals something about the level of immersion in the different simulations and the degree to which the students engage in conversations with the VH. The results show that these students were more concerned with what the VHs said—the content and fluency—rather than how they said it, with no regard for the picture, sound, or physical appearance. In addition, the students reported being quite neutral about the use of VHs in language education.

Given that we see a large variation in individual experiences, it makes sense to explore this in terms of the underlying individual factors affecting the overall experience. One possible way for such exploration is to look for dependencies within the three subgroups. The results suggest that the few students in the “negative group” were among those very concerned with and disturbed by technical issues, constraints and frequently not being understood or heard by the VH. These students reported little patience with the difficulties, spent less time on average in the system, and fulfilled fewer learning objectives. Time is one of the components raised as crucial in relation to getting used to the system and the new way of practising. It cannot be concluded in this study whether this result has to do with the students’ proficiency level, pronunciation of English, digital competence or setting, or a combination of these factors. However, one possible explanation is that the system may be more suitable for students with a higher proficiency level in English, similar to the findings of Sydorenko et al. (Citation2018), in which intermediate students struggled with listening comprehension on behalf of benefitting from the system. In contrast, other studies have found greater effects in beginners with low or moderate proficiency levels (Kim, Citation2016). Since this study was not intended to measure the efficacy of SDS, it was impossible to draw any similar conclusions.

Most students reported an average increase in motivation and feeling more prepared, more willing, and less anxious about speaking in everyday life outside of an institutional educational setting after the trial, which is in line with earlier studies (e.g., Ayedoun et al., Citation2015; Bashori et al., Citation2020, Citation2021; Divekar et al., Citation2021). These lower secondary school students valued their experiences with the system as easy, useful, and fun, as reported in a similar study on university students (Johnson, Citation2019), who also reported Enskill as a good way to learn English, while being easy and fun to use. The students in our study found it a good way to practice English while reporting mostly favourable views, mixed some communication breakdown issues where a minority showed less patience, in contrast to results from Dizon and Tang (Citation2020), where the students tended to give up totally in those cases.

The negative group’s results can, for instance, be related to earlier findings showing that users’ confidence in the ability to learn, speak and understand the target language increased when using a system providing appropriate feedback (Wang & Johnson, Citation2008), something that did not work entirely for all students in this study. Natural language processing was probably not sufficiently developed to recognise all students’ speech in the SDS; similar limitations were also reported in Johnsons’ (Citation2019) snapshot evaluations of Enskill. The VHs (i.e., acoustic models) of this data-driven system were not previously trained to recognise Swedish students’ variations in pronunciation and widespread levels of English. This study was the first to use Enskill in a Swedish educational context. One parallel can be drawn to a study of SPELL, where the VHs were trained on L1 speakers but had to recognise non-L1 speakers’ spoken language (Anderson et al., Citation2008), a prominent issue also highlighted by Godwin-Jones (Citation2009) said to provoke frustration.

In contrast, other studies found that the comprehensibility and intelligibility of “intelligent personal assistants” interacting with non-L1 accented students is comparable to human-to-human interaction (Moussalli & Cardoso, Citation2020). Further, positive student experiences have found CAs used successfully for language assessment based on this kind of conversation (Forsyth et al., Citation2019). Furthermore, the reported gender bias in this study, with less accuracy for female speakers, aligns with earlier research (Bajorek, Citation2019), which was not further developed in this study. Both students and their teacher expressed a wish for fewer constraints in the system and opportunities to choose between different varieties of English, including the VH, which currently speaks American English.

The strengths of this study are the rich dataset unpacking the students’ experiences in the system and enabling insights based on their voices of self-reported experiences, as suggested by Levy (Citation2015), together with the measurement of performance from the system, as suggested by Chan (Citation2009). Practising speaking skills with VHs has been reported mostly positively, but our study provides more nuance to current knowledge. This study provides a starting point for understanding how lower secondary school students experience using this kind of SDS and which aspects they highlight after interacting verbally with VHs. Future studies are recommended for this age group to explore aspects with a bearing on learning and effectiveness in students’ foreign language development.

6. Conclusions

This study aimed to increase knowledge about lower secondary school students’ perspectives on practising their foreign language speaking skills in verbal interactions with VHs in an SDS. When interpreting the results, it should be noted that the SDS used has not been designed with this age group of students in this Swedish educational context in mind; it is a small-scale study in sample size and time. Based on a multi-method analysis, the findings showed that the students found this method of practising speaking skills to be mostly fun, easy, and safe but could not see the task content in the scenarios entirely relating to their own everyday lives. In addition, there was individual variation in the extent to which constraints and technical issues provoked frustration. A possible relation was detected between the students’ reported positiveness/negativity toward the overall experience and their engagement with the system in relation to the learning objectives completed and the time spent. Regardless of the students’ mixed experiences, they were all eager to give suggestions for improving the system, such as content linked to their current and future everyday lives and with fewer constraints in the interactional design. The findings suggest that these lower secondary school students engaged in conversations with VHs in the SDS, facilitating supplementary and beneficial opportunities for practising speaking skills, especially pronunciation and interaction in dialogues. Their self-reported experiences are, to a great extent, consistent with the SLA key principles recognised for efficient foreign language development and learning.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Elin Ericsson

Elin Ericsson is a PhD student at the University of Gothenburg, at the Department of applied IT, working in the division for Learning, communication, and IT. Her research project is within the field of dialogue-based computer-assisted language learning (DB-CALL). She explores the use of spoken dialogue systems with conversational agents and their possibilities and challenges in teaching and learning foreign languages, especially speaking skills. Research reported in this paper will form, together with the contributions of other two student studies, and one initial study of teachers’ views of using this educational technology, the core of her doctoral thesis. The planned title is “Practising L2 Speaking with Conversational AI”. For more info see here.Photo of the first author: Elin Ericsson Photograph: Amanda Curtis.

References

- Adem, H., Berkessa, M., Khajavi, Y., & Khajavi, Y. (2022). (Reviewing editor) A case study of EFL teachers’ practice of teaching speaking skills vis-à-vis the principles of Communicative Language Teaching (CLT). Cogent Education, 9(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2022.2087458

- Alelo. (n.d.). Enskill® English. A revolution in English language teaching. https://www.alelo.com/english-language-teaching/

- Alm, A., & Nkomo, L. M. (2020). Chatbot experiences of informal language learners: A sentiment analysis. International Journal of Computer-Assisted Language Learning and Teaching, 10(4), 51–19. https://doi.org/10.4018/IJCALLT.2020100104

- Anderson, J. N., Davidson, N., Morton, H., & Jack, M. A. (2008). Language learning with interactive virtual agent scenarios and speech recognition: Lessons learned. Computer Animation and Virtual Worlds, 19(5), 605–619. https://doi.org/10.1002/cav.265

- Ayedoun, E., Hayashi, Y., & Seta, K. (2015). A conversational agent to encourage willingness to communicate in the context of English as a foreign language. Procedia Computer Science, 60(1), 1433–1442. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2015.08.219

- Bajorek, P. J. (2019, May 10). Voice recognition still has significant race and gender biases. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2019/05/voice-recognition-still-has-significant-race-and-gender-biases

- Bashori, M., van Hout, R., Strik, H., & Cucchiarini, C. (2020). Web-based language learning and speaking anxiety. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 35(5–6), 1058–1089. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2020.1770293

- Bashori, M., van Hout, R., Strik, H., & Cucchiarini, C. (2021). Effects of ASR-based websites on EFL learners’ vocabulary, speaking anxiety, and language enjoyment. System, 99, 102496. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2021.102496

- Bergman, M. M. (2008). The straw men of the qualitative-quantitative divide and their influence on mixed methods research. In M. M. Bergman (Ed.), Advances in mixed methods research theories and applications (pp. 11–23). SAGE.

- Bibauw, S., François, T., & Desmet, P. (2019). Discussing with a computer to practice a foreign language: Research synthesis and conceptual framework of dialogue-based CALL. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 32(8), 827–877. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2018.1535508

- Blake, R. J. (2017). Technologies for teaching and learning L2 speaking. In C. A. Chapelle & S. Sauro (Eds.), The handbook of technology and second language teaching and learning (pp. 107–117). Wiley-Blackwell.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Qualitative research in psychology using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise, and Health, 11(4), 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

- Brown, J. D. (2009). Open-response Items in questionnaires. In J. Heigham & R. A. Croker (Eds.), Qualitative research in applied linguistics (pp. 200–219). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Burden, D., & Savin-Baden, S. (2020). Virtual humans today and tomorrow. CRC Press.

- Burns, A. (2016). Research and the teaching of speaking in the second language classroom. In E. Hinkel (Ed.), Handbook of research in second language teaching (pp. 242–256). Routledge.

- Byram, M., & Méndez, M.-C. (2011). Communicative language teaching. In K. Knapp & B. Seidlhofer (Eds.), Handbooks of applied linguistics communication competence language and communication problems practical solutions (pp. 491–516). Walter de Gruyter.

- Chan, D. (2009). So why ask me? Are self-report data really that bad? In C. Lance & R. Vandenberg (Eds.), Statistical and methodological myths and urban legends: Doctrine, verity and fable in the organizational and social sciences (pp. 309–336). Routledge.

- Chapelle, C. A. (2009). The relationship between second language acquisition theory and computer-assisted language learning. The Modern Language Journal, 93, 741–753. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2009.00970.x

- Coniam, D. (2008). An evaluation of chatbots as software aids to learning English as a second language. The EuroCALL Review, 13, 2–14. https://doi.org/10.4995/eurocall.2008.16353

- Council of Europe. (2020). Common European framework of reference for languages: Learning, teaching, assessment – companion volume. Council of Europe Publishing. http://www.coe.int/lang-cefr

- Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Sage Publications, Inc.

- Darancik, Y. (2018). Students’ views on language skills in foreign language teaching. International Education Studies, 11(7), 166–178. https://doi.org/10.5539/ies.v11n7p166

- Divekar, R. R., Drozdal, J., Chabot, S., Zhou, Y., Su, H., Chen., Zhu, H., Hendler, J. A., & Braasch, J. (2021). Foreign language acquisition via artificial intelligence and extended reality: Design and evaluation. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 1–29. Advance Online Publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2021.1879162

- Dizon, G., & Tang, D. (2020). Intelligent personal assistants for autonomous second language learning: An investigation of Alexa. The JALT CALL Journal, 16(2), 107–120. https://doi.org/10.29140/jaltcall.v16n2.273

- Doremalen, J. V., Boves, L., Colpaert, J., Cucchiarini, C., & Strik, H. (2016). Evaluating automatic speech recognition-based language learning systems: A case study. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 29(4), 833–851. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2016.1167090

- Erickson, G., Bardel, C., Österberg, R., & Rosén, M. (2022). Attitudes and ambiguities – Teachers’ views on second foreign language education in Swedish compulsory school. In C. Bardel, C. Hedman, K. Rejman, & E. Zetterholm (Eds.), Exploring language education: Global and local perspectives (pp. 157–201). Stockholm University Press. https://doi.org/10.16993/bbz

- Forsyth, C. M., Luce, C., Zapata-Rivera, D., Jackson, G. T., Evanini, K., & So, Y. (2019). Evaluating English language learners’ conversations: Man vs. machine. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 32(4), 398–417. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2018.1517126

- Fryer, L. K., Nakao, K., & Thompson, A. (2019). Chatbot learning partners: Connecting learning experiences, interest and competence. Computers in Human Behavior, 93, 279–289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.12.023

- Gallacher, A., Thompson, A., & Howarth, M. (2018). “My robot is an idiot!” – Students’ perceptions of AI in the L2 classroom. Future-proof CALL: Language learning as exploration and encounters – short papers from EUROCALL 2018. https://doi.org/10.14705/rpnet.2018.26.815

- GDPR. (2018). General data protection regulation. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legalcontent/SV/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32016R0679&from=EN

- Godwin-Jones, R. (2009). Emerging technologies speech tools and technologies. Language Learning and Technology, 13(3), 4–11 http://dx.doi.org/10.125/44186.

- Goh, C. C. M., & Burns, A. (2012). Teaching speaking: A holistic approach. Cambridge University Press.

- Golonka, E. M., Bowles, A. R., Frank, V. M., Richardson, D. L., & Freynik, S. (2014). Technologies for foreign language learning: A review of technology types and their effectiveness. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 27(1), 70–105. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2012.700315

- Griol, D., & Callejas, Z. (2016). Conversational agents as learning facilitators: Experiences with a mobile multimodal dialogue system architecture. In S. Caballé & R. Clarisó (Eds.), Formative assessment, learning data analytics and gamification in ICT education (pp. 313–331). Academic Press.

- Hassani, K., Nahvi, A., & Ahmadi, A. (2016). Design and implementation of an intelligent virtual environment for improving speaking and listening skills. Interactive Learning Environments, 24(1), 252–271. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2013.846265

- Hodges, H., Steffensen, S. V., & Martin, J. E. (2012). Caring, conversing, and realizing values: New directions in language studies. Language Sciences, 34(5), 499–506. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.langsci.2012.03.006

- Huang, W., Hew, K. F., & Fryer, L. K. (2022). Chatbots for language learning—Are they really useful? A systematic review of chatbot-supported language learning. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 38(1), 237–257. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcal.12610

- Jeon, J. (2022). Exploring AI chatbot affordances in the EFL classroom: Young learners’ experiences and perspectives. Computer Assisted Language Learning, Taylor & Francis Online. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2021.2021241

- Johnson, W. L. (2019). Data-driven development and evaluation of Enskill English. International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education, 29(3), 425–457. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40593-019-00182-2

- Johnson, W. L., & Lester, J. C. (2016). Face-to-face interaction with pedagogical agents, twenty years later. International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education, 26(1), 25–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40593-015-0065-9

- Kaplan-Rakowski, R., & Wojdynski, T. (2018). Students’ attitudes toward high-immersion virtual reality assisted language learning. In P. Taalas, J. Jalkanen, L. Bradley, & S. Thouësny Eds. Future-proof CALL: Language learning as exploration and encounters – Short papers from EUROCALL 2018 (pp. 124–129). Research-publishing.net. https://doi.org/10.14705/rpnet.2018.26.824

- Kim, N. Y. (2016). Effects of voice chat on EFL learners’ speaking ability according to proficiency levels. Multimedia-Assisted Language Learning, 19(4), 63–88. https://doi.org/10.15702/mall.2016.19.4.63

- Kukulska-Hulme, A., & Lee, H. (2020). . In K.-M. Frederiksen, S. Larsen, L. Bradley, & S. Thouësny (Eds.), CALL for widening participation: Short papers from EUROCALL 2020 (pp. 172–176). Researchpublishing.net. https://doi.org/10.14705/rpnet.2020.48.1184

- Lantolf, J., Thorne, S. L., & Poehner, M. E. (2014). Sociocultural theory and second language development. In B. Vanpatten & J. Williams(Eds.), Theories in second language acquisition: An introduction (pp. 207–226). Taylor and Francis. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203628942-16

- Levy, M. (2015). The role of qualitative approaches to research in CALL contexts: Closing in on the learner’s experience. CALICO Journal, 32(3), 554–568. Equinox Publishing Ltd.https://doi.org/10.1558/cj.v32i3.26620

- Li, L. (2017). New Technologies and Language Learning. Palgrave.

- Loewen, S., & Sato, M. (2018). Interaction and instructed second language acquisition. Language Teaching, 51(3), 285–329. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444818000125

- Long, M. H. (1996). The role of the linguistic environment in second language acquisition. In W. C. Ritchie & T. K. Bhatia (Eds.), Handbook of second language acquisition (pp. 413–468). Academic Press.

- Morton, H., & Jack, M. A. (2005). Scenario-based spoken interaction with virtual agents. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 18(3), 171–191. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588220500173344

- Moussalli, S., & Cardoso, W. (2020). Intelligent personal assistants: Can they understand and be understood by accented L2 learners? Computer Assisted Language Learning, 33(8), 865–890. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2019.1595664

- Schroeder, N. L., Chiou, E. K., & Craig, S. D. (2021). Trust influences perceptions of virtual humans, but not necessarily learning. Computers & Education, 160, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2020.104039

- Schroeder, N. L., & Craig, S. D. (2021). Learning with virtual humans: Introduction to the special issue. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 53(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2020.1863114

- Swain, M. (2000). The output hypothesis and beyond: Mediating acquisition through collaborative dialogue. In J. P. Lantolf (Ed.), Sociocultural theory and second language learning (pp. 97–114). Oxford University Press.

- Swain, M. (2013). The inseparability of cognition and emotion in second language learning. Language Teaching, 46(2), 195–207. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444811000486

- Swedish Research Council. (2017). Good research practice. https://www.vr.se/english/analysis-and-assignments/we-analyse-and-evaluate/all-publications/publications/2017-08-31-good-research-practice.html

- Sydorenko, T., Daurio, P., & Thorne, S. L. (2018). Refining pragmatically-appropriate oral communication via computer-simulated conversations. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 31(1–2), 157–180. http://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2017.1394326

- Thiriau, C. (2017). Global Teaching Speaking Survey: The results. Cambridge University Press. https://www.cambridge.org/elt/blog/2017/11/06/teaching-speaking-survey-results/

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press.

- Wang, N., & Johnson, W. L. (2008). The politeness effect in an intelligent foreign language tutoring system. In B. P, Woolf, E., Aïmeur, R., Nkambou, S., Lajoie (Eds.) Intelligent Tutoring Systems. ITS 2008. Lecture Notes in Computer Science (Vol. 5091, pp. 270–280). LNCS: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-69132-7_31

- Wang, Y. F., Petrina, S., & Feng, F. (2017). VILLAGE–Virtual immersive language learning and gaming environment: Immersion and presence. British Journal of Educational Technology, 48(2), 431–450. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12388