Abstract

Online learning has become a significant trend in education due to the Covid-19 pandemic. Online educators, course designers and institutions need to understand the importance of social presence in the dynamics of a community of inquiry and its association with teaching and cognitive presence. This study examined whether social presence mediated the relationship between teaching and cognitive presence. The participants were a random sample of 572 postgraduate honours students (mean age of 35.4 years; SD = 8.39 years). Participants were registered in the College of Economic and Management Sciences and the College of Science, Engineering and Technology at the University of South Africa, an Open Distance e-Learning (ODeL) institution. The students completed a standardised measure of the Community of Inquiry (CoI) instrument. The results indicated that social presence mediated the relationship between teaching and cognitive presence. The findings highlight the importance of social presence as a fundamental aspect of collaborative online learning as institutions turn to fully online teaching platforms. By implication, academic institutions and teachers must provide a more collaborative and interactive online learning environment and promote productive online communities.

Public interest statement

This study explored how students’ online social presence influences their perception of teaching and cognitive experiences in a South African Open Distance e-Learning (ODeL) context. Data were collected using the Community of Inquiry (CoI) survey to determine if social presence mediates the relationship between teaching and cognitive presence of online honours students in a developing country. The data were analysed using descriptive, correlation and process macro regression analysis to determine the mediation effect. The paper confirmed that social presence mediates teaching and cognitive presence, showing the importance of online teacher-student and student-student interaction to create an engaged learning community for students studying in an ODeL environment. The study recommends the enhancement of social presence to increase student retention, learning and satisfaction and reduce the feeling of isolation while studying fully online.

Introduction

Online learning has become a significant trend in education due to the Covid-19 pandemic. With almost all educational institutions going online in 2020, students expect to experience deep and meaningful online learning. However, this sudden change caused several problems for students, such as a lack of resources (laptops) and connectivity, which confined the student’s capacity to participate effectively in online learning (Brenya & Wireko, Citation2021; Zhang et al., Citation2020). Nevertheless, with the right content and support from the institution, teachers and their peers, students should feel they have an excellent opportunity to complete their online courses. To achieve success in an online learning environment, students should interact and collaborate online with their teachers and peers. Through the use of the Community of Inquiry (CoI) Framework (D. R. Garrison et al., Citation2000), online students may experience “meaning-making”, “trust”, and a “deeper understanding” of the learning content when studying online (Peacock & Cowan, Citation2016). The CoI framework consists of three presences, namely: teaching presence (TP), cognitive presence (CP) and social presence (SP), which will be discussed in more detail further on.

The focus of this study is on the social presence factor, which has been researched since the early adaptation of computer conferencing for learning purposes and is an important mediating variable within the CoI framework (Garrison et al., Citation2010; Shea & Bidjerano, Citation2009). According to Annand (Citation2011, 43), social presence has been considered a critical and “important antecedent to collaboration and critical discourse because it facilitates achieving cognitive objectives by instigating, sustaining, and supporting critical thinking in a community of learners.” According to Lin et al. (Citation2015), SP supports critical thinking and practical conversation and strengthens CP.

Although the importance of social presence in online/blended learning settings has been well-documented (Armellini & De Stefani, Citation2016; D’Alessio et al., Citation2019; Kim et al., Citation2016; Poquet et al., Citation2018; Swan & Shih, Citation2005), most of the research is situated within formal education from developed countries. Learners may have different online engagement patterns in the context of open distance e-learning in developing countries. Therefore, it calls for future studies to investigate the effect of social presence on the relationship between teaching and cognitive presence. This article will explore how students’ online social presence influences their perception of their teaching and cognitive experiences in a South African Open Distance e-Learning (ODeL) context. The goal is to quantitatively explore the mediating effect of social presence on teaching and cognitive presence.

Although previous studies advanced the association between the three presence aspects of the community of inquiry (Kozan, Citation2016; Ma et al., Citation2017; Mutezo & Maré, Citation2022; Peacock & Cowan, Citation2016; Shea & Bidjerano, Citation2009; Stenbom, Citation2018; Zhu, Citation2018), there is a dearth of research exploring the mediating effect of social presence on teaching and cognitive presence in an ODeL context in a developing country like South Africa. That said, there is still work to be done to understand social presence’s importance in the dynamics of a community of inquiry and its relationship to teaching and cognitive presence (Lowenthal, Citation2012; Yamada & Kitamura, Citation2011; Yuan & Kim, Citation2014). The following section describes the study context.

1. Unisa context

The current study sought to explore social presence and its mediation role in the association between TP and CP within the Community of Inquiry (CoI) framework manifested amongst postgraduate honours students at the University of South Africa (Unisa). Unisa is the first dedicated, largest ODeL institution in South Africa and the African continent, with a history spanning over 140 years (Baijnath, Citation2014; Kgatla, Citation2016). With over 300000 students, the institution is counted as one of the mega-universities globally (Queiros & De Villiers, Citation2016).

Like other Distance Education (DE) institutions, Unisa has migrated through various generations of distance education, from predominately print-based correspondence, multimedia interaction, video conferencing, online learning and transitioning into ODeL (Queiros & De Villiers, Citation2016; Sonnekus et al., Citation2006). The Covid-19 pandemic forced Unisa to switch to a fully online form of instruction (University of South Africa (Unisa), Citation2020). The university comprises seven colleges, namely the College of Accounting Sciences, College of Agricultural Science, College of Economics and Management Science, College of Education, College of Human Science, College of Law and College of Science, Engineering and Technology. Since digital technology has become critical in all spheres, the university anticipates that online learning will ensure that every graduate can learn and function effectively in the digital era (Baijnath, Citation2014). Further, through online learning, Unisa anticipates supporting and mediating the transactional distance between the students and the institution (Hülsmann & Shabalala, Citation2016) and consequently improving student throughput and reducing the dropout rate of online education students.

This situation underscores the importance of social presence in an online learning environment. Swan and Richardson (Citation2017) emphasise the importance of developing a social presence to increase student retention, learning and satisfaction and reduce the feeling of isolation. The findings of this study could be instrumental in effecting the required changes in online learning, course design and the application of the Learning Management System (LMS) to enhance student collaboration in South Africa’s educational system. The following section describes the dynamics of the CoI framework.

2. Literature review

This study is based on the CoI framework, designed by D. R. Garrison et al. (Citation2000), (Citation2001) and is based on a collaborative-constructivist process model that describes the essential elements of a successful online higher education learning experience (Castellanos-Reyes, Citation2020; Garrison, Citation2017). This framework’s principle is that higher-order learning is best supported in a community of learners engaged in critical reflection and discourse (Garrison et al., Citation2010). According to the CoI framework, in the absence of face-to-face interaction with lecturers and peer students, participants of online learning environments must recreate the social and knowledge-building processes that occur via the moment-by-moment negotiation of meaning found in the face-to-face classroom (Zou et al., Citation2021). The CoI framework addresses the teaching, cognitive and social aspects of learning in online communities. This article will focus on three original presences as defined by D. R. Garrison et al. (Citation2000).

In this process, the CoI framework consists of three unique, interrelating elements: cognitive, teaching, and social presence, essential to providing a successful educational experience. According to this framework, the overlap of these three core elements in an online environment will support purposeful inquiry and meaningful collaboration.

The first core element of the CoI framework is the teaching presence (TP). Teaching presence is critical to help students realise the meaning and educational value of the coursework. Teaching presence involves the instructional methods used by teachers for setting up the course design, planning, interactions, and direct instructional methods (Yu & Richardson, Citation2015). This dimension brings together the social and cognitive presences directed to personally meaningful and educationally worthwhile outcomes (Vaughan et al., Citation2013).

The second core element of the community of inquiry is the cognitive presence (CP), reflecting the learning and inquiry process. According to Garrison et al. (Citation2001), cognitive presence identifies four phases in the inquiry process. These phases include defining a problem or task, exploring relevant information/knowledge, making sense of and integrating ideas, and, finally, testing plausible solutions (Garrison et al., Citation2010). All of this occurs in an environment of reflection and discourse, analysis and synthesis. According to Kucuk and Richardson (Citation2019), CP is essential in maintaining and facilitating deep engagement in learning.

The third core element, social presence (SP), is the ability “of learners to project themselves socially and emotionally, being perceived as real people in mediated communication” (D. R. Garrison et al., Citation2000, 94). Social presence creates trust, open communication, and group cohesion (Suppiah et al., Citation2020; Vaughan et al., Citation2013). Therefore, SP outlines the human experience of learning (Stenbom, Citation2018). Some indicators of SP include an available method of communication, group coherence, the encouragement of collaboration and expressing emotionally, such as using humour. These goals can be achieved online using an LMS and discussion forums for students to interact and respond to synchronous activities via Teams or Zoom meetings (tools available for such interactions). Using these tools will lead to a higher social presence, which creates the basis necessary to build on the cognitive presence (enabling learners to build on meaning in a course). A central premise of Garrison’s model is that “learning occurs through interaction” (Horzum, Citation2015, 25). The CoI model assumes that online courses are more effective when creating a virtual environment where the instructor and students are all present and learning together (D’Alessio et al., Citation2019). The creation of SP can make online learning more “interactive, appealing, engaging, and intrinsically rewarding, leading to an increase in academic and social integration that results in increased persistence and course completion” (Reio & Crim, Citation2006, 964). When these three core dimensions interact, students can have a deeper and more meaningful learning experience (Morrison, Citation2014).

2.1. Relationship between the three presences

Garrison et al. (Citation2010), Kozan (Citation2016), and Mutezo and Maré (Citation2022) used structural equation modelling to establish that the three presences are interconnected and influence each other in a hypothesised manner. Garrison et al. (Citation2010) showed that TP directly influences social and cognitive presence perceptions, while SP also significantly predicted CP. Garrison et al. (Citation2010) concluded that SP is a mediating factor that provides context for the educational process. On the other hand, Kozan’s (Citation2016) results indicated social presence as a partial mediator and cognitive presence as a full mediator. This means that educators can increase online learners’ cognitive presence directly, and they can do so by first increasing their social presence (Kozan, Citation2016). The study conducted by Mutezo and Maré (Citation2022) yielded a three-factor solution showing teaching presence as the highest variable and that the CoI survey is valid for ODeL institutions in a developing country. Further studies by Law et al. (Citation2019) and Ke (Citation2010) established that teaching presence directly affects social and cognitive presence. These studies showed that teaching presence plays a critical part in facilitating cognitive thinking and social interaction with peer students.

Shea and Bidjerano (Citation2009) found that social presence has a relatively insignificant effect on the online learning experience. Students who had a low social experience, but a high teaching presence still reported a high cognitive presence. The authors concluded that good teaching presence without sustained social presence could still give rise to deep learning. Arbaugh et al. (Citation2008) and Richardson and Swan (Citation2003) found a strong correlation between social presence and perceived learning during an online course. This finding implies that SP enhances students’ effective learning. Diaz et al. (Citation2010) administered the CoI survey to 413 graduate and undergraduate student volunteers at four US universities and colleges to determine learners’ perceptions of the three CoI presences and their interactions. Social presence was rated as the least important. A study by Akyol and Garrison (Citation2008) found only a significant relationship between teaching and cognitive presence and not social presence. Even though the above studies reported different findings, they all suggest that there may be a close interrelationship among the CoI presences, as reported in the study of Garrison et al. (Citation2010) and Kozan and Richardson (Citation201).

2.2. The mediating role of social presence

Garrison et al. (Citation2010) showed that teaching presence could significantly predict cognitive presence, while social presence is the mediator between the two. Li (Citation2022) found that SP partially mediates the association between TP and CP. A study by Shea et al. (Citation2010) indicated a strong correlation between teaching and social presence, which means that a more visible and active teacher implies more social students. Archibald (Citation2010) found that social and teaching presence explained 69% of the variance in cognitive presence, whereas a study by Shea & Bidjerano, Citation2009) found a 50% variation in social and teaching presence with cognitive presence. Kozan (Citation2016) indicated that when cognitive presence is encouraged, this may increase social presence levels. These studies indicate a complex interrelationship between the three presences in the creation of knowledge. Further research needs to examine these relationships to understand the importance of social presence in different contexts.

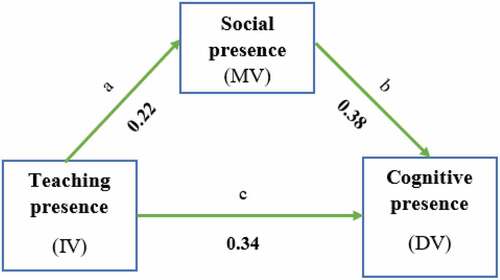

This study aims to examine the mediating effect of social presence on teaching and cognitive presence. The study thus proposes the following conceptual framework (refer to Figure below), which will determine the effect of these presences on each other.

Figure 1. A Theoretical Framework for the Study (Authors own compilation)

Figure above illustrates that social presence is seen as the mediator variable (MV), teaching presence the independent variable (IV) and cognitive presence the dependent variable (DV). The arrows in Figure propose that (1) teaching presence directly relates to SP and CP presences, and (2) TP indirectly influences CP via SP.

H1: Social presence mediates the relationship between TP and CP

3. The goal of the study

This study investigated postgraduate honours students’ perceptions of how their social presence affects their teaching and cognitive presence. The study was guided by the following research question: How does social presence mediate the relationship between teaching and cognitive presence of online honours students in a developing country setting?

4. Methodology

4.1. Participants

A cross-sectional quantitative survey was followed (Saunders et al., Citation2019). Participants were a probability random sample of 572 postgraduate honours at the University of South Africa (61.4% = female, 38.6% = male, mean age = 35.4 years). The majority of the participants (60%) were in the early adulthood and late career-establishment stage (aged 25–63 years). The participants studied in an ODeL environment through the myUnisa LMS, which allows for both asynchronous and synchronous online interaction and communication. Data collection took place between June and August 2019.

4.2. Measures

The Community of Inquiry (CoI) instrument (Arbaugh et al., Citation2008) was used to collect data via an online survey and has been validated within a South African ODeL context, refer to Mutezo and Maré (Citation2022). The instrument consists of a 34-item scale (Arbaugh et al., Citation2008; Swan et al., Citation2008). The scale measures three domains: teaching presence (13 items, e.g., “The lecturer communicates clearly important course objectives”); cognitive presence (12 items, e.g., “I develop solutions to course problems that can be applied in practice”); social presence (9 items, e.g., “I feel comfortable interacting with other student participants”), refer to Appendix 1 for further details on the specific questions used for each construct. Items are scored on a five-point Likert-type response format ranging from 1 = “strongly disagree” to 5 = “strongly agree”. Higher scores denote higher students’ perception levels of the three presences. In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha values for scores from the CoI ranged between 0.90 and 0.95, which indicates the internal consistency of each item and the reliability of the scale.

4.3. Research procedure and ethical considerations

The Research Ethics Committee of the College of Economic and Management Sciences and the Permissions Research Ethics Committee at the University of South Africa approved the study (2019_CRERC_006 and 2019_RPSC_010). The participants consented to participate following an explanation of the study’s goals and its voluntary and confidential nature. The participants completed the survey online at their convenience.

4.4. Statistical analysis

Data were analysed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) Version 27 for Windows software (2021). Using process macro regression analysis, we sought to predict the teaching presence from cognitive presence with moderation by social presence. Descriptive statistics were calculated to determine the mean, standard deviations and Cronbach Alpha. Correlation analysis was used to determine the relationship between the teaching, cognitive and social presences. A preliminary analysis was conducted to ensure that there was no violation of multicollinearity to conduct mediation analysis. The tolerance value was 0.561 (TP) and 0.558 (CP), and the variance inflation factor (VIF) was 1.783 (TP) and 1.791 (CP), which indicates there is no multicollinearity for this dataset (Pallant, Citation2020).

The key research questions were examined using mediation regression analysis following the recommendations offered in Hayes and Preacher (Citation2014) with the Process Macro on SPSS (Hayes, Citation2017), which was used to identify the extent to which the mediator variable (social presence) accounted for the direct and indirect effect relationship between the independent variable (teaching presence) and the dependent variable (cognitive presence). The significance value was set at the 95% confidence interval level (p ≤ 0.05) to counter the probability of type 1 errors (Hayes, Citation2017).

5. Results

5.1. Descriptive

Table below shows that the cognitive presence scored (M = 3.78; SD = .0.61), social presence (M = 3.70; SD = 0.68), and teaching presence scored (M = 3.37; SD = 0.82). Skewness ranged from −0.45 to −0.77, and kurtosis ranged between 0.25 to 1.64 for all the presences, thereby falling within −2 and above the +2 normality ranges recommended for these variables (Bryne, Citation2010).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics

5.2. Bivariate correlations

As can be observed in Table , teaching presence correlated positively with cognitive presence (r = 0.66; large effect size; p ≤ 0.05). A positive correlation was observed between teaching and social presence (r = 0.38; medium effect size; p ≤ 0.05). Finally, a positive correlation was observed between cognitive and social presence (r = 0.57; large effect size; p ≤ 0.05).

Table 2. Bivariate correlations between study variable (N = 572)

5.3. Mediating regression

As can be observed in Table , the results indicated that TP was a significant predictor of SP B = 0.22, SE = 0.002, 95%CI [0.18,0.27], ß = 0.38, p < .0001, and SP was a significant predictor of CP B = 0.38, SE = 0.03, 95%CI [0.31,044], β=0.35, p < .0001. These results support the mediational hypothesis. TP was a significant predictor of CP after controlling for the mediation, SP B = 0.34, SE = 0.02, 95%CI [0.30,037], β=0.53, consistent with partial mediation. The predictors accounted for approximately 54% of the variance in CP (R2 = 0.54). The indirect effect was tested using the percentile bootstrap estimation approach with 572 sample (Hair Jr et al., Citation2019), implemented with process macro version 3 (Hayes, Citation2017). These results indicated indirect coefficient was significant B = 0.08, SE = 0.01, 95%CI [0.06, 0.11], completely standardised B = 0.13. TP was associated with a CP score that was approximately 13 points higher, as indicated by SP.

Table 3. SP as a mediator of the relationship between TP and CP

Figure shows the mediating effect of SP with regard to the association between TP and CP. The arrows in Figure indicate that TP directly relates to SP and CP and that TP indirectly influences CP via SP. This means that SP is a mediator between TP and CP.

6. Discussion

The purpose of this study was to examine the mediating effect of SP in the relationship between TP and CP in a fully-online CoI-based learning ODeL community in a developing country. The results show a significant positive relationship between TP and CP. Moreover, SP mediated the relationship between TP and CP.

The result suggests that (i) TP correlates positively with CP. This implies that the higher the TP, the higher the CP. In other words, if the students perceive TP, they will likely demonstrate understanding and more profound learning skills and critical thinking. This study aligns with CitationKozan and Richardson’s (201) and Li’s (Citation2022) studies, which found that TP relates positively to cognitive presence. Our study results further showed that TP and CP related positively with SP, implying that students who perceived that their teachers planned and designed the course using direct instructional methods were likely to engage further in open communication and group cohesion. These findings are consistent with Richardson and Swan’s (Citation2003).

Social and cognitive presences related positively. These results imply that the higher the SP, the higher the CP. This implies that a positive perception of social presence engenders trust among students in an online learning environment. The results can be linked to similar findings by Garrison et al. (Citation2010) and Li (Citation2022), who found social presence positively related to cognitive presence.

The findings suggested that SP influences the relationship between TP and CP. This can be explained by the fact that when students perceive a trusting environment and identify with the community, they will likely realise personally, meaningful, and educationally worthwhile learning outcomes. This, in turn, leads them to make sense of and test plausible solutions. These findings are supported and similar to Garrison et al. (Citation2010), Li (Citation2022) and Shea and Bidjerano (Citation2009), who found SP to mediate the relationship between teaching and cognitive presence. This implies that when students perceive the design facilitation and proper cognitive and social processes, they can confirm meaning through sustainable reflection. These findings collaborate with those studies by Arbaugh et al. (Citation2010), Joo et al. (Citation2011), and Lin et al. (Citation2015), who found that TP influences CP and SP positively.

7. Limitations and implications for future studies

This study was not without limitations. Firstly, the research was conducted on a sample of postgraduate honours students in one open distance learning institution in South Africa. Therefore, it is not possible to generalise the results to other institutions of higher learning with face-to-face or blended learning environments. Longitudinal studies in the form of panel data should be conducted to establish the relationship between the core elements of the CoI framework. It is recommended that the study be replicated with more extensive samples across various institutions in other developing countries using fully online learning environments and different cultural contexts.

8. Recommendations and conclusion

This research suggests that TP influences CP. Moreover, SP acted as a mediating factor between teaching and cognitive presence in a fully online learning environment. Students who identify with the community, communicate purposefully in a positive and trusting environment, and develop interpersonal relationships by portraying their personalities, would likely be able to define tasks, explore relevant information, and make sense of and integrate ideas. For students to comprehend, they need connections and support in a time of considerable disconnection and confusion in higher education. The current study provides new evidence for ODeL institutions in emerging countries on the importance of developing a connected and engaged student community before comprehending and synthesising the study material. The Covid-19 pandemic makes it even more important for students to focus on themselves and their support networks to prevent attrition, disappointment, and disengagement while studying online. Unless students’ social needs are met, they cannot focus on learning their course content. The study implies that SP is necessary to facilitate higher-order cognitive presences and hence deep, meaningful learning (Annand Citation2011).

SP refers to how socially and emotionally connected learners are with others in an online course or environment (Swan et al., Citation2008). SP unveiled that students needed support and motivation to learn remotely in times of crisis to reduce isolation. Furthermore, the study showed the need for human interaction and engagement (Ensmann et al., Citation2021).

The findings highlight the importance of social presence as a fundamental aspect of collaborative online learning as institutions turn to fully online teaching platforms. It is recommended that universities provide training and professional development opportunities that consider social presence elements in online learning to improve faculty-student and student-student connection and engagement. This study recommends that academic institutions and teachers provide a more collaborative and interactive online learning environment and promote productive online communities, to enhance the quality of education, increase student retention and reduce the feeling of isolation for students studying in an ODeL environment.

Acknowledgements

The study is funded by the Open Distance Learning Research Support Programme (ODL–RSP) at UNISA.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Ashley Teedzwi Mutezo

Ashley Teedzwi Mutezo is a Professor in the Department of Finance, Risk Management and Banking at the University of South Africa. She holds a Doctor of Commerce Degree and a Master’s Degree in Business Management from Unisa. Her research interests are in Risk Management, SME Financing and ODeL. Ashley has published in accredited journals and presented several papers at local and international conferences.

Suné Maré

Suné Maré is a Lecturer in the Department of Finance, Risk Management and Banking at the University of South Africa. She obtained her Master’s Degree in Risk Management with distinction at Unisa. Her research interests lie in online learning and risk management. She has co-published ODeL articles in accredited journals and presented several papers at conferences. She is also involved in the development of modules for online teaching. In 2016, she received Unisa’s Excellence in Teaching and Learning Award for student support.

References

- Akyol, Z., & Garrison, D. R. (2008). The development of a community of inquiry over time in an online course: Understanding the progression and integration of social, cognitive and teaching presence. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 12(3−4), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v12i3.72

- Annand, D. (2011). Social presence within the community of inquiry framework. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 12(5), 40–56. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v12i5.924

- Arbaugh, J. B., Bangert, A., & Cleveland-Innes, M., & Cleveland-Innes. (2010). Subject matter effects and the Community of Inquiry (CoI) framework: An exploratory study. The Internet and Higher Education, 13 (1−2), 37–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2009.10.006

- Arbaugh, J. B., Cleveland-Innes, M., Diaz, S., Garrison, D. R., Ice, P., Richardson, J., & Swan, K. P. (2008). Developing a community of inquiry instrument: Testing a measure of the community of inquiry framework using a multi-institutional sample. The Internet and Higher Education, 11(3–4), 133–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2008.06.003

- Archibald, D. 2010. “Fostering the development of cognitive presence: Initial findings using the community of inquiry survey instrument. Internet and Higher Education, 13, 73–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2009.10.001

- Armellini, A., & De Stefani, M. (2016). Social presence in the 21st century: An adjustment to the Community of Inquiry Framework. British Journal of Educational Technology, 47(6), 1202–1216. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12302

- Baijnath, N. (2014). Curricular innovation and digitisation at a mega university in the developing world - The University of South Africa “signature course” project. Journal of Learning for Development, 1(1), 1–6. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Curricular-Innovation-and-Digitisation-at-a-Mega-inBaijnath/e2ca0907fcc0c6da744166e957be5ef33

- Brenya, B., & Wireko, J. K. 2021. The social presence factor in blended learning community and student engagement in higher education institution in developing countries. International Conference on Cyber Security and Internet of Things (ICSIoT), France, 79–84. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICSIoT55070.2021.00023.

- Bryne, B. M. (2010). Structural equation modelling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications and programming (2nd) ed.). Routledge Taylor and Francis Group. 396 p.

- Castellanos-Reyes, D. (2020). 20 Years of the Community of Inquiry Framework. Association for Educational Communications and Technology, 64, 557–560. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-020-00491-7

- D’Alessio, M. A., Lundquist, L. L., Schwartz, J. J., Pedone, V., Pavia, J., & Fleck, J. (2019). Social presence enhances student performance in an online geology course but depends on instructor facilitation. Journal of Geoscience Education, 67(3), 222–236. https://doi.org/10.1080/10899995.2019.1580179

- Diaz, S. R., Swan, K., Ice, P., & Kupczynski, L. (2010). Student ratings of the importance of survey items, multiplicative factor analysis, and the validity of the community of inquiry survey. The Internet and Higher Education, 13(1–2), 22–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2009.11.004

- Ensmann, S., Whiteside, A., Gomez-Vasquez, L., & Sturgill, R. (2021). Connections before curriculum: The role of social presence during COVID-19 emergency remote learning for students. Online Learning, 25(3), 36–56. https://dx.doi.org/10.24059/olj.v25i3.2868

- Garrison, D. (2017). E-learning in the 21st century: A community of inquiry framework for research and practice (3rd ed) ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315667263

- Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., & Archer, W. (2000). Critical inquiry in a text-based environment: Computer conferencing in higher education. The Internet and Higher Education, 2(2−3), 87–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1096-7516(00)00016-6

- Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., & Archer, W. (2001). Critical thinking, cognitive presence, and computer conferencing in distance education. American Journal of Distance Education, 15(1), 7–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/08923640109527071

- Garrison, D. R., Cleveland-Innes, M., & Fung, T. S. (2010). Exploring causal relationships among teaching, cognitive and social presence: Student perceptions of the community of inquiry framework. The Internet and Higher Education, 13(1–2), 31–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2009.10.002

- Hair Jr, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. 2019. Multivariate Data Analysis (8th) Pearson Education Limited Edition, Pearson New International Edition

- Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach (2nd) ed.). Guilford Press.

- Hayes, A. F., & Preacher, K. J. (2014). Statistical mediation analysis with a multi-categorical independent variable. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology, 67(3), 451–470. https://doi.org/10.1111/bmsp.12028

- Horzum, M. B. (2015). Interaction, structure, social presence, and satisfaction in online learning. Eurasia Journal of Mathematics. Science and Technology Education, 11(30), 505–512. https://doi.org/10.12973/eurasia.2014.1324a

- Hülsmann, T., & Shabalala, L. (2016). Workload and interaction: Unisa’s signature courses–a design template for transitioning to online distance education? Distance Education, 37(2), 224–236. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2016.1191408

- Joo, Y. J., Lim, K. Y., & Kim, E. K. (2011). Online university students’ satisfaction and persistence: Examining the perceived level of presence, usefulness and ease of use as predictors in a structural model. Computers and Education, 57(2), 1654–1664. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2011.02.008

- Ke, F. (2010). Examining online teaching, cognitive, and social presence for adult students. Computers and Education, 55(2), 808–820. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2010.03.013

- Kgatla, M. V. (2016). An exploration of social presence amongst first-year undergraduate students in a fully asynchronous web-based course: A case at the University of South Africa [ Unpublished Master’s thesis, University of South Africa]. Unpublished Master’s thesis, University of South Africa. University of South Africa. http://hdl.handle.net/10500/22285

- Kim, J., Song, H., & Luo, W. (2016). Broadening the understanding of social presence: Implications and contributions to the mediated communication and online education. Computers in Human Behavior, 65, 672–679. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.07.009

- Kozan, K. (2016). A comparative structural equation modelling investigation of the relationship among teaching, cognitive and social presence. Online Learning, 20(3), 210–227. https://dx.doi.org/10.24059/olj.v20i3.654

- Kozan, K., & Richardson, J. C. (201). Interrelationships between and among social, teaching, and cognitive presence. The Internet and Higher Education, 21, 68–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2013.10.007

- Kucuk, S., & Richardson, J. C. (2019). A structural equation model of predictors of online learners’ engagement and satisfaction. Online Learning, 23(2), 196–216. https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v23i2.1455

- Law, K. M. Y., Geng, S., & Li, T. (2019). Student enrollment, motivation and learning performance in a blended learning environment: The mediating effects of social, teaching and cognitive presence. Computers and Education, 136, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2019.02.021

- Li, L. (2022). Teaching presence predicts cognitive presence in blended learning during COVID-19: The chain mediating role of social presence and sense of community. Frontiers in Psychology, 13(950687), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.950687

- Lin, S., Hung, T. C., & Lee, C. T. (2015). “Revalidate forms of presence in training effectiveness: Mediating effect of self-efficacy.”. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 53(1), 32–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/0735633115588772

- Lowenthal, P. R. 2012. Social presence: What is it? How do we measure it? ( Publication No: 3506428) [Doctoral dissertation, University of Colorado Denver]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses database.

- Ma, Z., Wang, J., Wang, Q., Kong, L., Wu, Y., & Yang, H. (2017). Verifying casual relationships among the presences of the community of inquiry framework in the Chinese context. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 18(6), 213–230. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v18i6.3197

- Morrison, D. 2014. “How to develop a sense of presence in online and f2f courses with social media.” Online Learning Insights. Retrieved 14 June 2021 https://onlinelearninginsights.wordpress.com/2014/09/29/how-to-develop-a-sense-of-presence-in-online-and-f2f-courses-with-social-media/

- Mutezo, A., & Maré, S. (2022). Factorial structure of the community of inquiry survey in a South African open and distance e-learning environment. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 32(2), 129–135. https://doi.org/10.1080/14330237.2022.2028081

- Pallant, J. (2020). SPSS survival manual: Step-by-step guide to data analysis using IBM SPSS (7th Edition) ed.). Open University Press. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003117452

- Peacock, S., & Cowan, J. (2016). From presences to linked influences within the communities of inquiry. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 17(5, 267–283. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v17i5.2602

- Poquet, O., Kovanović, V., de Vries, P., Hennis, T., Joksimović, S., Gašević, D., & Dawson, S. (2018). Social Presence in Massive Open Online Courses. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 19(3), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v19i3.3370

- Queiros, D. R., & De Villiers, M. R. (2016). Online learning in a South African Higher education institution: determining the right connections for the student. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 17(5), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v17i5.2552

- Reio, T. G., Jr., & Crim, S. J. 2006. The Emergence of Social Presence as an Overlooked Factor in Asynchronous Online Learning. Retrieved 14 June 2021, http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED492785.pdf

- Richardson, J. C., & Swan, K. (2003). Examining social presence in online courses in relation to students’ perceived learning and satisfaction. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 7(1), 68–88. https://dx.doi.org/10.24059/olj.v7i1.1864

- Saunders, M. N. K., Lewis, P., & Thornhill, A. (2019). Research methods for business students (8th) ed.). Pearson Education Limited.

- Shea, P., & Bidjerano, T. (2009). Community of inquiry as a theoretical framework to foster “epistemic engagement” and “cognitive presence” in online education. Computers and Education, 52(3), 543–553. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2008.10.007

- Shea, P., Hayes, S., Vickers, J., Gozza-Cohen, M., Uzuner, S., Mehta, R., Valchova, A., & Rangan, P. (2010). A re-examination of the community of inquiry framework: Social network and content analysis. The Internet and Higher Education, 13, 10–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2009.11.002

- Sonnekus, I., Louw, W., & Wilson, H. 2006. “Emergent learner support at Unisa: An informal report.” South African Journal for Open and Distance Learning Practice 28(1−2), 44–53. https://journals.co.za/doi/10.10520/EJC88795

- Stenbom, S. (2018). A systematic review of the Community of Inquiry survey. The Internet and Higher Education, 39, 22–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2018.06.001

- Suppiah, S., Wah, L. K., Lajium, D. A., & Swanto, S. (2020). Exploring a collaborative and dialogue-based reflective approach in an e-learning environment via the Community of Inquiry (CoI) Framework. CALL-EJ, 20(3), 117–139. http://callej.org/journal/20-3/Suppiah-Lee-Lajium-Swanto2019.pdf

- Swan, K., & Richardson, J. C. (2017). Chapter 7: Social presence and the community of inquiry framework (A. L. Whiteside, A. Garrett Dikkers, & K. Swan, Eds.). Social presence in online learning: Multiple perspectives on practice and research (p.p. 64−76). Stylus Publishing.

- Swan, K., Richardson, J. C., Ice, P., Garrison, D. R., Cleveland-Innes, M., & Arbaugh, J. B. (2008). Validating a measurement tool of presence in online communities of inquiry. E- Mentor, 2(24). http://www.e-mentor.edu.pl/artykul_v2.php?numer=24andid=543

- Swan, K., & Shih, L. F. (2005). On the nature and development of social presence in online course discussions. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 9(3), 115–136. http://dx.doi.org/10.24059/olj.v9i3.1788

- University of South Africa (Unisa). (2020). Rising to the virtual challenge: DHET Report 2020. The Department of Higher Education and Training Republic of South Africa. https://www.unisa.ac.za/sites/corporate/default/News-&-Media/Publications/Annual-reports

- Vaughan, N. D., Cleveland-Innes, M., & Garrison, D. R. (2013). Teaching in blended learning environments: Creating and sustaining communities of inquiry. AU Press.

- Yamada, M., & Kitamura, S. (2011). The role of social presence in interactive learning with social software. Social Media Tools and Platforms in Learning Environments, 325–335. Springer Heidelberg Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-20392-3_19

- Yuan, J., & Kim, C. (2014). Guidelines for facilitating the development of learning communities in online courses. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 30(3), 220–232. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcal.120432

- Yu, T., & Richardson, J. C. (2015). Examining reliability and validity of a Korean version of the Community of Inquiry instrument using exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis. The Internet and Higher Education, 25, 45–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2014.12.004

- Zhang, W., Wang, Y., Yang, L., & Wang, C. (2020). Suspending classes without stopping learning: china’s education emergency management policy in the COVID-19 Outbreak. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 13(3), 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm13030055

- Zhu, X. 2018. Facilitating effective online discourse: Investigating Factors influencing students’ cognitive presence in online learning. Master’s thesis, University of Connecticut: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/gs_theses/1277/.

- Zou, W., Hu, X., Pan, Z., Li, C., Cai, Y., & Liu, M. (2021). Exploring the relationship between social presence and learners’ prestige in MOOC discussion forums using automated content analysis and social network analysis. Computers in Human Behavior, 115, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106582