Abstract

Since a pandemic was declared in 2020, Irish higher education institutions transitioned from on-campus to online delivery. This disruption created challenges to students’ acquisition of hard and soft skills. With greater employee mobility, there is an increased emphasis on soft skills development, especially those skills that enhance employability, i.e., creativity, leadership, communication, innovation, teamwork, adaptability, resilience, time management, organization, self motivation, ability to work under pressure, critical thinking and problem solving and organizational ability. The purpose of this study was to understand the effects of COVID-19 on fears for the future and on soft skills development. In this study, 111 Software Engineering university students were surveyed. The results show heightened fears for the future with regard to job opportunities, the loss of time and the lack of control. While females reported to being more fearful, they also reported enhanced empathy and strengthened resilience. Postgraduate students were less fearful about the future compared to undergraduate students whilst also reporting better time management and organization skills. This study showed that despite disruptions to education, the Software Engineering students self-reported enhancements to resilience, empathy, time management and organizational skills, with the greatest impact on resilience and time management.

1. Introduction

On 11 March 2020, the World Health Organization declared a global pandemic [WHO, Citation2020, Cucinotta & Vanelli, Citation2020]. In an effort to mitigate the spread of COVID-19, governments around the world closed schools, colleges, non-essential services and childcare centres in addition to advising those who could work from home to do so (Doyle, Citation2020; Lades et al., Citation2020). More than 180 countries worldwide were ‘wrenched” from face-to-face learning to online delivery, affecting greater than 150 billion learners across multiple educational levels (Sasere & Makhasane, Citation2020; Shahzad et al., Citation2021). To deal with the enforced closures, most higher education institutes (HEIs) underwent a “major paradigm shift” as they rapidly transitioned from face-to-face/blended learning to 100% online learning (p. 1; Parker et al., Citation2021). Using a combination of video streaming and virtual classrooms for synchronous and asynchronous delivery (Gonzalez et al., Citation2020), this rapid transition to online learning forced many HEIs to re-strategize (Shiohira & Keevy, Citation2020) and drove many academics into “unfamiliar terrain” as they made efforts to adapt their content to accommodate remote learning (p. 196; García-Morales et al., Citation2021). The move to 100% online negatively affected soft skills development (Kamysbayeva et al., Citation2021).

Studies show that the enforced isolation from peers and friends, and the imposed absence from college socializing and its associated support services due to COVID-19, resulted in a greater sense of isolation for students coupled with heightened anxiety, higher levels of depression and worsened mental health issues (Cao et al., Citation2020; Hamza et al., Citation2021; Son et al., Citation2020; Tahara et al., Citation2021). Students experienced increased boredom (Son et al., Citation2020), suicide ideation (Kaparounaki et al., Citation2020) and loneliness (Killgore et al., Citation2020), in addition to a reduced sense of well-being (Evans et al., Citation2021). Meanwhile, a study by (Ali et al., Citation2021) suggests that the break down in college life routine caused, for some students, a sense of time dilation that resulted in a lack of engagement. Students were further challenged with a decrease in the quality of their sleep (Zhang et al., Citation2020), which has been shown to negatively impact learning, academic performance and both mental and physical health (Almojali et al., Citation2017; Feng et al., Citation2014; Jalali et al., Citation2020). Across all levels of society, the screen time increased significantly during COVID-19 (Sultana et al., Citation2021). Although the social lives of younger people are typically rooted in the digital world (Twenge, Citation2017), they generally tend to choose face-to-face third-level programmes based on the enhanced learning experiences and social benefits offered by such programmes and extracurricular activities; all of which contribute to the development of their graduate attributes (Jaggars, Citation2014).

Graduate attributes within the context of Software Engineering refer to the hard skills (i.e. technical skills in software processes, methodologies and tools (Matturro et al., Citation2019)) and soft skills (i.e. communication, teamwork, organization, time management, critical thinking and problem solving skills, interpersonal skills, empathy, etc.) that enhance employability (Cinque, Citation2016; Dempsey et al., Citation2009; Tang, Citation2019; Tseng et al., Citation2019). While it is not in the remit of HEIs to guarantee employability, it is their responsibility to provide learning experiences which facilitate the development of hard and soft skills (Brennan & Dempsey, Citation2018; Malik & Ahmad, Citation2020; Minocha et al., Citation2017; Barros & Bittencourt, Citation2018) contends that the use of active learning strategies supports the development of soft skills. Other opportunities for soft skills development include; feedback (for self reflection purposes and to help with critical thinking; Brown et al., Citation2017), team projects (for interpersonal, collaboration, communication and problem solving skills; Vogler et al., Citation2018), study skills and time management workshops (for supporting students in taking better control, being more capable of dealing with problems and being more organized), attending lectures (for time management and organizational skills; Beard et al., Citation2008) and extra-curricular activities such as team sports (for time management, teamwork and socio-emotional skills; Arat, Citation2014; Cinque, Citation2016). The physical attendance at an HEI and the ensuing interactions with peers (both educationally and socially) also help to develop social awareness and can enhance intercultural skills (Martínez Lirola,). While the acquisition of relevant hard and soft skills addresses societal needs and market demands (Kanwar & Carr, Citation2020), the sudden transition to online delivery and the overall disruptions to college life and corresponding support services negatively impacted the learning experience and drastically interrupted opportunities for soft skills development (Cardoso-Espinosa et al., Citation2021).

Although research to date has mostly focused on the negative psychological and social effects of COVID-19 on students, there is a paucity of research on the impact of COVID-19 on soft skills. Given that software development has been and continues to be one of the most impactful and growing professions over the last number of decades, the acquisition of soft skills is especially critical in order to prepare Software Engineering graduates to adeptly deal with uncertain circumstances, a changed industrial landscape and a community which is typically characterized by a diverse workforce (Capretz & Ahmed, Citation2010). In this study, 111 third-level Software Engineering students in the final year of their undergraduate and postgraduate programmes provide insights into their worldview regarding fears for the future after living through 2 years of COVID-19 and the impact of COVID-19 on their soft skills development, i.e. resilience, empathy, organization, and time management.

2. Soft skills for software engineering students

Today’s increasingly interconnected world has served to accelerate employee mobility and opportunity (Derven, Citation2014), and place a greater emphasis on soft skills development (Naamati Schneider et al., Citation2020). UNESCO defines soft skills as a term which is “used to indicate a set of intangible personal qualities, traits, attributes, habits and attitudes that can be used in many different types of jobs … Examples of soft skills include: empathy, leadership, sense of responsibility, integrity, self-esteem, self-management, motivation, flexibility, sociability, time management and making decisions” (U. I. B. o. Education, Citationn d). Soft skills are also integral to Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 4.4: Relevant Skills for Decent Work (UNESCO, Citationn d). While soft skills can be learned from experience and on the job training, there are increasing expectations from businesses and accreditation bodies that HEIs will include learning experiences that reinforce student employability through the development of hard and soft skills (Arat, Citation2014; Brennan & Dempsey, Citation2018; Malik & Ahmad, Citation2020). However, disruptions to HEIs during COVID-19 created challenges to the traditional manner of acquiring such skills, particularly the development of soft skills, which also play a significant role in personality development (Malik & Ahmad, Citation2020). Typically, when content is to be delivered online, learning activities are designed to support the development and transfer of soft skills (Tseng et al., Citation2019). However, the sudden closure of HEIs forced many institutions to “evolve toward online teaching in record time, implementing and adapting the technological resources available and involving professors and researchers who lack innate technological capacities for online teaching” (p. 196; García-Morales et al., Citation2021). Interestingly, notwithstanding the promise of online learning, it is generally perceived negatively by students (Akpınar, Citation2021).

The soft skills which enhance employability and prepare Software Engineering students for a volatile job market typically include; creativity, leadership, communication, innovation, teamwork, adaptability, resilience, time management, organization, self motivation, ability to work under pressure, critical thinking and problem solving and organizational ability (Cinque, Citation2016; Hidayati et al., Citation2020; Shabir & Sharma, Citation2019). Software engineering continues to be one of the most impactful and growing professions (Capretz & Ahmed, Citation2010). The development of soft skills in this domain is especially critical as Software Engineering is by its very nature labour and knowledge intensive, characterized by a diverse workforce where project teamwork and effective communication are integral to successful software project success (Altiner & Ayhan, Citation2018). In a COVID-19 re-shaped global economy, many businesses have had to rapidly re-define themselves and adapt to an uncertain landscape (Li, Citation2021). In order to survive in this volatile job market, it is evermore important that Software Engineering graduates possess both the hard and soft skills as demanded by industry (Arat, Citation2014; Malik & Ahmad, Citation2020; Cinque, Citation2016) contends that a lack of skills (both hard and soft) can cause major problems for businesses. Meanwhile, Konak and Kulturel-Konak (Citation2019) argue that the lack of essential soft skills in Software Engineering teams is a key reason for the failure of IT-related projects.

3. Methods

Given the paucity of research on the impact of COVID-19 on soft skills, the research question for this study is; “What is the impact of COVID-19 on soft skills for Software Engineering students?” A Phenomenological research approach was followed as it “seeks to understand experiences and in particular the meaning people make from those experiences” (p. 379; Letourneau, Citation2015). Consequently, this study explored the personal views of undergraduate and postgraduate Software Engineering students regarding their fears for the future due to COVID-19 and their self-reporting of the impact of COVID-19 on their soft skills development, i.e. resilience, empathy, organization, and time management. To that end, an online survey was designed. In order to validate the initial survey and ensure that the survey questions aligned with the research question, the survey was tested with a representative group of final year and post graduate Software Engineering students. The revised survey comprised four sections: general respondent information, perceived fears for the future, impact on resilience and impact on the soft skills of empathy, and time management and organisational skills. The survey questions were coded in either an open question format or on a five‑point Likert scale, with 1 being strongly disagree and 5 being strongly agree. On average, the online instrument took 10–15 minutes to complete. Quantitative data were analysed using IBM SPSS V 26 with the statistical significance being set at p < 0.05. Qualitative data analysis was carried out primarily at the level of semantic themes. However, where relevant, the authors delved deeper and examined the responses at the latent level. Thematic analysis at the semantic level is defined as an examination of ” … the explicit or surface meanings of the data” (p. 84; Maguire & Delahunt, Citation2017). Meanwhile, thematic analysis at the latent level is defined as the point at which one starts “to identify or examine the underlying ideas, assumptions, and conceptualizations—and ideologies” (p. 84; Maguire & Delahunt, Citation2017).

4. Results

4.1. Characteristics of the survey respondents

A breakdown of the survey respondents’ demographics is presented in Table . As can be seen, the majority of the sample comprised male participants (78.3%, n = 111) with most respondents aged between 20 and 25 years old (66.67%, n = 111). Due to the nature of the programmes, the undergraduate and Higher Diploma Software Engineering students have been more affected by the disruption to their learning experience and access to support services compared to the Masters students. The latter have more experience with online delivery.

Table 1 Respondents’ demographics

4.2. Fears for the future

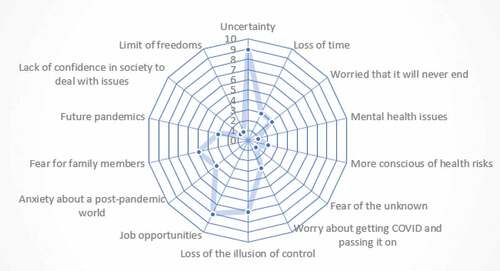

With regard to fears of the future, 45% (n = 111) of the respondents agreed that after living through 2 years of COVID-19, they are increasingly fearful of the future, while 28.8% are not. The results of the Chi-squared Test of Association showed that there was no significant relationship between gender and fears for the future (x2(df = 8, n = 111) = 5.785, p = .671). The Shapiro–Wilk test was first used to test for normality. As the p value (<.001) was less than the alpha value of .05, the null hypothesis that the data was normal was rejected at 5% significance, and we conclude that the data was non-normal. As the nonparametric equivalent of the two sample t-test, the Mann Whitney test revealed that fears for the future were slightly higher in females (MD = 4.00, n = 23) than males (MD = 3.00, n = 86), z = −.173, p = .862. Whilst there was no statistical significance in fears for the future based on undergraduate or postgraduate status (p = 0.06812) or between masters and higher diploma students (p = .208) such fears were slightly greater in undergraduate students (MD = 4.00, n = 35) compared to postgraduate students (MD = 3.00, n = 76), z = 1.82. All of the respondents aged >26 years showed that their increased fears for the future were primarily related to job opportunities and unemployment. In general, the issues of which students were most fearful included; uncertainty, fears over loss of time, worries that the pandemic will never end, mental health problems, greater awareness of health risks, greater fears of the general unknown, worries about contracting COVID-19 and passing it on to family members, loss of the illusion of control, loss of job opportunities, increased anxiety about a post-pandemic world, fear for family members, fear of future pandemics, a lack of confidence in society and its leaders to deal with comparable risks and issues and a fear regarding the limitation of freedoms (Figure ).

4.3. Resilience

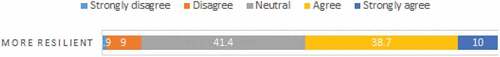

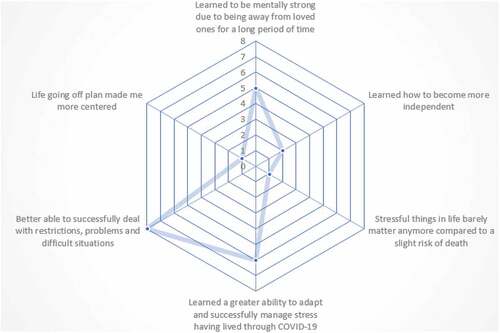

Resilience has been defined as “the ability to bounce back or recover from stress, to adapt to stressful circumstances, to not become ill despite significant adversity, and to function above the norm in spite of stress or adversity” (p. 194; Smith et al., Citation2008). Despite living through lockdowns, imposed isolation, a closure of social activities and a heightened fear for the future, etc., 48.7% of respondents (n = 111) reported greater resilience as a result of living through COVID-19 compared to 9.9% who reported a lack of resilience skills development (Figure ).

While there was no statistically significant difference between undergraduate and postgraduate students (p = 0.702) or between higher diploma and masters students (p = .372), a Mann Whitney test revealed that resilience scores were significantly higher in females (MD = 4.00, n = 23) than males (MD = 3.00, n = 87), z = −2.995, p = .003, with a moderate effect r = .285. A Kruskal–Wallis test showed that although resilience scores were not significantly different between the six age groups, those aged 20–25 years (MD = 3.00, n = 74) and those aged 30–35 years (MD = 3.00, n = 12) indicated that they felt they had become less resilient because of COVID-19 than those aged 26–30 years (MD = 4.00, n = 19), 36–40 years (MD = 4.00, n = 3), 41–45 years (MD = 4.00, n = 1) and 46+ years (MD = 4.00, n = 2), p = .421. Where they were provided, the reasons for a greater sense of strengthened resilience skills were thematically analysed with their frequency of occurrence captured (Figure ).

Spearman’s rank order correlation was computed to assess the relationship between resilience and fears for the future. There was a non-significant very small negative relationship between resilience and fears for the future (r(109) = .133, p = .163) and a non-significant very small positive relationship between resilience and a greater sense of empathy (r(109) = .0827, p = .388).

4.4. Soft skills acquisition

The soft skills scales comprised three items (α = .77344). The Cronbach’s alpha of .77344 indicates acceptable internal validity and consistency in the responses relating to how COVID-19 impacted on the soft skills development of empathy, time management and organizational skills.

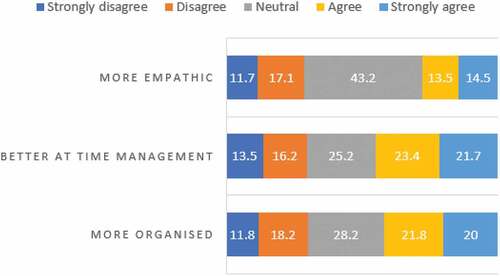

The common thread in the multiplicity of definitions for empathy is the ability to understand another person’s perspective (Cuff et al., Citation2016). 28.2% of respondents (n = 111) self-reported heightened empathy resulting from having lived through COVID-19, while 28% self-reported lower feelings of empathy and 43.8% reported no change (Figure ). A Mann Whitney test revealed a statistically significant higher self-reporting of heightened empathy skills for females (MD = 3.00, n = 23) compared to males (MD = 3.00, n = 87), z = −2.99, p = .003, with a weak effect, r = .28. There was no statistical significance in the self-reported empathy scores between undergraduate and postgraduate students (p = .246, z = −1.159) or between higher diploma and masters students (p = .564).

45.1% of the respondents (of which 26% were females and 72% were males) agreed that 2 years since the beginning of COVID-19, their time management skills have increased significantly. A Mann Whitney test revealed a statistically significant higher self-reporting of better time management skills for postgraduate students (MD = 4.00, n = 76) compared to undergraduate students (MD = 2.00, n = 35), z = −3.56, p = .000, with a moderate effect, r = .33. Although there was no statistical significance in the difference of the higher diploma and masters students’ self-reported time management skills, the higher diploma students self-reported slightly more improved time management skills (MD = 4.0 n = 50) compared to the masters students (MD = 3.5, n = 26), p = .760. While proportionally more females than males self-reported better time management skills (47.8% vs 41.3%), there was no statistical significance in the difference between their self-reported time management skills (p = .697).

41.1% of the respondents self-reported better organization skills despite the disruptions to educational delivery over the last 2 years, while 29.7% indicated worsening organization skills. A Mann Whitney test revealed a statistically significant higher self-reporting of better organization skills for postgraduate students (MD = 3.00, n = 76) compared to undergraduate students (MD = 2.00, n = 35), z = −3.512, p = .000, with a moderate effect, r = .333. Although there was no statistical significance in the difference of the higher diploma and masters postgraduate students’ self-reported organization skills, the masters students self-reported slightly more improved organization skills (MD = 3.5 n = 26) compared to the higher diploma students (MD = 3.0, n = 50), p = .764. Proportionally more females than males self-reported better organization skills (56.5%, n = 23 vs 36.7%, n = 87). However, this was not statistically significant (p = .282).

The results of the Spearman’s rank order correlation to assess the relationship between organisation and time management indicated that there was a significant large positive relationship between organisation and time management (r(109) = .779, p < .001), a significant small positive relationship between time management and empathy (r(109) = .272, p = .004) and a non-significant very small negative relationship between fears for the future and empathy (r(109) = .116, p = .227).

5. Discussion

Intensified fears for loved ones, anxiety about future pandemics and a heightened awareness of health risks are understandable, given that the need to socially distance, quarantine and/or radically alter one’s lifestyle in response to epidemics and/or pandemics acerbates existing and/or creates new stressors (Son et al., Citation2020). Almost half of the respondents in this study agreed that COVID-19 heightened their fears for the future, with females tending to have a slightly greater fear regarding the future compared to their male counterparts. This is in line with the literature, which suggests that females are more likely to be affected by stress-related incidents and indeed are more than twice as likely to develop mood and anxiety disorders than males (Fallon et al., Citation2020). The study also showed that undergraduate students reported more heightened fear of the future compared to their postgraduate counterparts. This is not surprising as some of the masters students tend to be working already so they are less likely to be fearful of job opportunities and unemployment. As to be expected, most fears converged on the loss of the illusion of control, uncertainty and reduced employment prospects in a volatile job market, characterized by the closure of predominantly small businesses either temporarily or permanently (CSO, Citation2020; Tang et al., Citation2021; Zhai & Yue, Citation2022) and the implementation by some companies of indefinite hiring embargos (Donthu & Gustafsson, Citation2020). The students’ fears are well ground as some of those businesses which have survived successive closures and re-openings typically do so, at a lower yield and level of productivity (Galindo-Martín et al., Citation2021).

A study by (Crane et al., Citation2022) suggests elevated levels of “business death” for American SMEs during COVID-19 compared to previous non-COVID-19 years. Paradoxically, COVID-19 has also resulted in an “explosion” of entrepreneurially driven start-ups (Haltiwanger, Citation2021) and unparalleled growth in sectors such as online entertainment, online communication and online shopping (Donthu & Gustafsson, Citation2020). The former reflects the historical trend that recessions and pandemics lead to increased innovation and entrepreneurship (Garcia et al., Citation2021). Nonetheless, the overall global economic downturn has resulted in higher levels of unemployment and a correspondingly more competitive job market (Mok et al., Citation2021). Graduates entering the labour market with the requisite hard and soft skills will clearly be at an advantage compared to their lesser skilled counterparts. While HEIs have a responsibility to contribute to economic growth and the knowledge that underpins a competitive economy (Chankseliani et al., Citation2021), they are also required to provide the necessary learning environment to develop their students, socially, personally and intellectually. Part of their remit, therefore, is to produce graduates who are equipped with the necessary hard and soft skills to function in that economy (Brennan & Dempsey, Citation2018; Malik & Ahmad, Citation2020; Minocha et al., Citation2017). Within a HEI setting, students are provided with academic and extracurricular opportunities to develop these hard and soft skills, the latter being recognized to be as important as the former (Cinque, Citation2016; Tang, Citation2019).

A study Gruzdev et al. (Citation2018) regarding the skills sought by businesses indicated that the most desired soft skills included: interpersonal and teamwork skills, time management, communication in both oral and written form and critical analysis and problem solving skills. While the rapid transition to online delivery forced many HEIs to quickly turn around standard content for online delivery, there was insufficient time and in some cases experience for many academics, to design and integrate learning activities to support the development and transfer of soft skills (García-Morales et al., Citation2021). As a result, some soft skills were under developed.

Nonetheless, despite 2 years of disruptions to their learning experience and a general lack of opportunities for soft skills development, this study shows that the Software Engineering students self-reported enhanced resilience. Although (Chen et al., Citation2022) found low levels of resilience and ability to cope in third-level students during COVID-19, our study showed that on the whole, the Software Engineering students indicated stronger feelings of resilience, mainly due to “having lived through it so far”. This dovetails with the suggestion that “resilience is not personal and innate characteristics, but it is a process revealed as a result of interaction of several factors in case of one’s experiences in difficulty” (p. 1263; Erdogan et al., Citation2015). In line with the findings from (Zhang et al., Citation2020), our study showed that females tended to be more resilient than males with no significant difference reported between undergraduate and postgraduate students. 69.5% (n = 23) of female respondents indicated a greater sense of resilience compared to 42.5% (n = 87) of male respondents. The findings are contrary to a Turkish study, but further analysis may be required to compare studies using a cultural lens (Erdogan et al., Citation2015). Nevertheless, 48.7% of our study’s respondents self-reported stronger resilience after having lived through COVID-19. This is promising as resilience in the “face of” stressful conditions can positively impact psychosocial health and wellbeing whilst also being an “important personal resource” (p. 2; Dijkstra & Homan, Citation2016).

Within the context of Software Engineering, resilience is an important human capacity, especially given the high proportion of software development projects that can be terminated before they reach completion (Todt et al., Citation2018), in addition to the fluidity of user requirement changes (Schmidt et al.,).

Although 43.8% of the study’s respondents reported no change to their empathy skills, more than 28% of respondents reported heightened empathy from having lived through COVID-19. As one of the critical components of emotional intelligence (Ioannidou & Konstantikaki, Citation2008), empathy is fundamental to effective leadership, collaboration and creativity (Skinner & Spurgeon, Citation2005; Young, Citation2015). Furthermore, empathy is a critical skill for Software Engineering graduates, given the increasingly diverse nature of software development project teams and the need to liaise with stakeholders (Altiner & Ayhan, Citation2018).

Nearly 50% of respondents reported enhanced time management skills, with postgraduate students reporting better time management skills compared to undergraduate students. Meanwhile, more than 40% of the respondents reported better organizational skills. The masters students reported slightly higher organization skills compared to the higher diploma students. This was to be expected as this particular masters programme is a very structured course with weekly deliverables. Hence, in a sense, organization is almost controlled for the student. Typically, HEIs provide workshops on time management and study skills, but the availability of these resources was temporarily disrupted until facilitators and students were up and running remotely. Time management and organizational ability are important skills linked to enhanced academic (Tus, Citation2020) and job performance (Ping & Xiaochun, Citation2018). Good time management “involves skills in goal setting, setting priorities, planning and organizing skills and minimizing time wasting” (p. 1480; Nayak, Citation2019). Our study showed a significantly larger positive relationship between organization and time management skills.

In summary, while the Software Engineering students surveyed in this study generally have acerbated fears for the future, the act of surviving COVID-19 and coping with the rapid transition to online delivery has heightened empathy, strengthened resilience and improved time management and organization skills. The development of these skills will enable Software Engineering students to adapt and be more flexible along with being more empathetic and resilient.

6. Limitations

This study has several limitations. Firstly, while the sample size of 111 was small, it included both Software Engineering undergraduate students in the final year of their programme and postgraduate students. We acknowledge that this study population is not representative of third-level students in general. Furthermore, given the nature of CS, there were substantially more male respondents than female respondents (78.4% versus 20.7%). Secondly, it would have been preferable to test the respondents’ baseline levels of resilience and empathy prior to COVID-19. Furthermore, while students reported their views regarding feelings of resilience, a more formal instrument such as the Brief Resilience Scale (BRS; Smith et al., Citation2008) would have provided a deeper understanding of the characteristics (e.g., optimism, coping style, social support, etc.) which underpin and impact on resilience.

Another limitation is the number of soft skills which were examined. Future studies could analyze the impact of COVID-19 on a more comprehensive list of soft skills. Finally, while studies show that students with mental health challenges typically have lower life satisfaction, a lower health status and higher COVID-19 anxiety (Tahara et al., Citation2021), further limitations to this study are the lack of identification of the state of the students’ mental health prior to completing the study’s survey and the need for a deeper understanding of the qualitative data through semi-structured interviews.

7. Conclusions

Over the past two years into the COVID-19 pandemic, multiple studies have been completed regarding the psychological, social, environmental and physical effects of remote learning. During this time period, HEIs have transitioned from traditional delivery to 100% online delivery to a staggered re-opening with hybrid delivery. Part of the remit of HEIs is to provide both the hard and soft skills demanded by social needs and market requirements. However, the disruption to HEI provision and services, and the rapid transition to online delivery without the requisite time to re-design content appropriately, affected soft skills development in particular. While studies have focused primarily on the negative impacts of COVID-19 on third-level students, few have looked at its impact on soft skills acquisition. Soft skills are of particular importance for Software Engineering students as they transition to a volatile job market and an uncertain industrial landscape. Skills related to resilience, empathy, communication, teamwork, organization, and adaptability are fundamental to work and life opportunities.

In this study, 111 Software Engineering university students, 35 of whom were undergraduate and 76 were postgraduate students, were surveyed. The purpose of this study was to elicit the personal views of undergraduate and postgraduate Software Engineering students regarding their fears for the future due to COVID-19 and their self-reporting of the impact of COVID-19 on their soft skills development, i.e. resilience, empathy, organization, and time management. 45% (n = 111) of the respondents agreed that after 2 years of COVID-19, they are unsurprisingly more fearful of the future. Undergraduate students were more fearful than postgraduate students. All of the respondents aged >26 years showed that their fears for the future were primarily related to job opportunities and unemployment. Their greatest fears centred around uncertainty, loss of time and loss of the illusion of control. Students were also afraid of the higher potential for future pandemics and the lack of confidence in the authorities to handle arising issues. Furthermore, they reported fears for; mental health problems and other health risks, the general unknown, worries about contracting COVID-19 and passing it on to family members and the limitation of freedoms.

The positive impacts of living through COVID-19 included a greater sense of resilience, increased empathy and improved time management and organizational skills. While females reported higher fears for the future, they also reported greater resilience, enhanced empathy and improved time management and organizational skills. Although there was no significant difference in empathy between undergraduate and postgraduate students, the postgraduate students reported better time management and organization skills. Those students aged between 20 and 35 years reported reduced resilience in general.

As HEIs return to a form of normality, lessons on the positive and negative impact of COVID-19 can be learned from 2 years of disrupted education. With the likelihood of future pandemics, HEIs have a greater responsibility to provide learning opportunities that integrate technology and support soft skills acquisition (Blau et al., Citation2020; Dempsey & Brennan, Citation2017, Citation2018; Dempsey et al., Citation2018, Citation2009, ; McAvoy et al., Citation2020; O’Dea et al., Citation2018; Winter et al., Citation2013). HEIs need to maintain the advances made and reduce/eliminate the negatives as much as possible. They need to be more conscious of soft skills in the re-design of curricula around activities and learning experiences, in order to build on the potential and ensure greater opportunities for soft skills development. If HEIs build additional soft skills early in the curriculum, graduates will automatically learn to be more flexible and better able to adapt to a world where remote working becomes more the norm than the unusual (Morrison-Smith & Ruiz, Citation2020), and where virtual spaces become increasingly prevalent in both the educational and the employment environments (Wong et al., Citation2019).

Inevitably, pandemics will re-occur. The experience from living through COVID-19 can be drawn on to better prepare students for many known and unknown pathways into the future.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to all 111 students who engaged with the survey.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Akpınar, E. (2021). The effect of online learning on tertiary level students mental health during the Covid-19 Lockdown. The European Journal of Social & Behavioural Sciences, 30(1), 52–15. https://doi.org/10.15405/ejsbs.288

- Ali, A., Siddiqui, A. A., Arshad, M. S., Iqbal, F., & Arif, T. B. (2021). Effects of COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown on lifestyle and mental health of students: A retrospective study from Karachi, Pakistan. In Annales Médico-psychologiques, revue psychiatrique (Vol. 180, No. 6, pp. S29-S37). Elsevier.

- Almojali, A. I., Almalki, S. A., Alothman, A. S., Masuadi, E. M., & Alaqeel, M. K. (2017). The prevalence and association of stress with sleep quality among medical students. Journal of Epidemiology and Global Health, 7(3), 169–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jegh.2017.04.005

- Altiner, S., & Ayhan, M. B. (2018). An approach for the determination and correlation of diversity and efficiency of software development teams. South African Journal of Science, 114(3–4), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.17159/sajs.2018/20170331

- Arat, M. (2014). Acquiring soft skills at university. Journal of Educational and Instructional Studies in the World, 4(3), 46–51. https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=58dfe7fe713fed5db36626bf265264b69cc7b95b

- Barros, F. L., & Bittencourt, R. A., “Evaluating the influence of PBL on the development of soft skills in a computer engineering undergraduate program,” In 2018 IEEE Frontiers in Education Conference (FIE), 2018: IEEE, pp. 1–9.

- Beard, D., Schweiger, D., & Surendran, K. (2008). Integrating soft skills assessment through university, college, and programmatic efforts at an AACSB accredited institution. Journal of Information Systems Education, 19(2), 229–240. https://jise.org/Volume19/n2/JISEv19n2p229.pdf

- Blau, I., Shamir-Inbal, T., & Avdiel, O. (2020). How does the pedagogical design of a technology-enhanced collaborative academic course promote digital literacies, self-regulation, and perceived learning of students? The Internet and Higher Education, 45, 100722. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2019.100722

- Brennan, A., & Dempsey, M. (2018). P-PAC (partnership in pedagogy, accreditation, and collaboration): A framework to support student transition to employability in industry. A lean systems case study. Management and Production Engineering Review, 9. https://yadda.icm.edu.pl/baztech/element/bwmeta1.element.baztech-a4cadcea-bd4a-4ae3-82b5-519b4f128f0e

- Brown, M., Worth, M., & Boylan, D. (2017). Improving critical thinking skills: Augmented feedback and post-exam debate. Business Education & Accreditation, 9(1), 55–63. https://www.theibfr2.com/RePEc/ibf/beaccr/bea-v9n1-2017/BEA-V9N1-2017-5.pdf

- Cao, W., Fang, Z., Hou, G., Han, M., Xu, X., Dong, J., & Zheng, J. (2020). The psychological impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on college students in China. Psychiatry Research, 287, 112934. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112934

- Capretz, L. F., & Ahmed, F. (2010). Why do we need personality diversity in software engineering? ACM SIGSOFT Software Engineering Notes, 35(2), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1145/1734103.1734111

- Cardoso-Espinosa, E. O., Cortés-Ruiz, J. A., & Zepeda-Hurtado, M. E. (2021). The development of mathematics and soft skills at the graduate level through project-based learning in times of COVID-19. Tem Journal-Technology Education Management Informatics, 1638–1644. https://www.temjournal.com/content/104/TEMJournalNovember2021_1638_1644.pdf

- Chankseliani, M., Qoraboyev, I., & Gimranova, D. (2021). Higher education contributing to local, national, and global development: New empirical and conceptual insights. Higher Education, 81(1), 109–127. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-020-00565-8

- Chen, T., Lucock, M., & Mittal, P. (2022). The mental health of university students during the COVID-19 pandemic: An online survey in the UK. PLoS one, 17(1), e0262562. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0262562

- Cinque, M. (2016). Lost in translation”. Soft skills development in European countries. Tuning Journal for Higher Education, 3(2), 389–427. https://doi.org/10.18543/tjhe-3(2)-2016pp389-427

- Crane, L. D., Decker, R. A., Flaaen, A., Hamins-Puertolas, A., & Kurz, C. (2022). Business exit during the COVID-19 pandemic: Non-traditional measures in historical context. Journal of Macroeconomics, 72, 103419. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmacro.2022.103419

- CSO., “Business Impact of COVID-19 on SMEs 2020,” 2020: https://www.cso.ie/en/releasesandpublications/ep/p-bics/businessimpactofcovid-19onsmes2020/businessclosures/#:~:text=Over%20four%20in%20ten%20responding,during%20the%20pandemic%20in%202020

- Cucinotta, D., & Vanelli, M. (2020). WHO declares COVID-19 a pandemic. Acta Bio Medica: Atenei Parmensis, 91(1), 157. https://doi.org/10.23750/abm.v91i1.9397

- Cuff, B. M., Brown, S. J., Taylor, L., & Howat, D. J. (2016). Empathy: A review of the concept. Emotion Review, 8(2), 144–153. https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073914558466

- Dempsey, M., & Brennan, A. (2017). Turbocharging the journey into the liminal space and beyond. development, 27, 28. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/0320/768107faed2a722df15ac557b978f8efee97.pdf

- Dempsey, M., & Brennan, A., “Empowering learners with self-selecting learning tools,” in 12th International Technology, Education and Development Conference, 2018 International Academy of Technology, Education and Development (IATED).

- Dempsey, M., Brennan, A., & O’Dea, M., “Re-boot learning: Providing an e-tivity scaffold for engagement for early research activity through blog technology embedded within teaching and learning,” in 12th International Technology, Education and Development Conference, 2018 International Academy of Technology, Education and Development (IATED).

- Dempsey, M., Gormley, P., & McDwyer, L., “An analysis of third-level multi-cultural interdisciplinary student learning outcomes using Wiki technology,” in 9th Annual Irish Learning Technology Association Conference EdTech, 2009 ILTA Irish Learning Technology Association

- Dempsey, M., Gormley, P., & Riedel, R. (2011). Using Wikis to Facilitate Team Work: German and Irish Students?. https://eprints.teachingandlearning.ie/id/eprint/2176/1/Dempsey%20et%20al%202011.pdf

- Derven, M. (2014). Diversity and inclusion by design: Best practices from six global companies. Industrial and Commercial Training.

- Dijkstra, M., & Homan, A. C. (2016). Engaging in rather than disengaging from stress: Effective coping and perceived control. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1415. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01415

- Donthu, N., & Gustafsson, A. (2020). Effects of COVID-19 on business and research. Vol. 117 ed, Elsevier

- Doyle, O. (2020). COVID-19: Exacerbating educational inequalities. Public Policy, 9, 1–10. https://publicpolicy.ie/downloads/papers/2020/COVID_19_Exacerbating_Educational_Inequalities.pdf

- Erdogan, E., Ozdogan, O., & Erdogan, M. (2015). University students’ resilience level: The effect of gender and faculty. Procedia-social and Behavioral Sciences, 186, 1262–1267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.04.047

- Evans, S., Alkan, E., Bhangoo, J. K., Tenenbaum, H., & Ng-Knight, T. (2021). Effects of the COVID-19 lockdown on mental health, wellbeing, sleep, and alcohol use in a UK student sample. Psychiatry Research, 298, 113819. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2021.113819

- Fallon, I. P., Tanner, M. K., Greenwood, B. N., & Baratta, M. V. (2020). Sex differences in resilience: Experiential factors and their mechanisms. European Journal of Neuroscience, 52(1), 2530–2547. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejn.14639

- Feng, Q., Zhang, Q.-L., Du, Y., Ye, Y.-L., He, Q.-Q., & Stewart, R. (2014). Associations of physical activity, screen time with depression, anxiety and sleep quality among Chinese college freshmen. PloS one, 9(6), e100914. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0100914

- Galindo-Martín, M.-Á., Castaño-Martínez, M.-S., & Méndez-Picazo, M.-T. (2021). Effects of the pandemic crisis on entrepreneurship and sustainable development. Journal of Business Research, 137, 345–353. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.08.053

- García-Morales, V. J., Garrido-Moreno, A., & Martín-Rojas, R. (2021). The transformation of higher education after the COVID disruption: Emerging challenges in an online learning scenario. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 196. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.616059

- Garcia, M., Poz-Molesky, J., Uslay, C., & Karniouchina, E. V. (2021). Rising on the storm: A comparison of the characteristics of entrepreneurs and new ventures during and before the Covid-19 Pandemic. In Rutgers Business Review (pp. 244–262). Málaga, Spain.

- Gonzalez, T., de la Rubia, M. A., Hincz, K. P., Comas-Lopez, M., Subirats, L., Fort, S., & Sacha, G. M. (2020). Influence of COVID-19 confinement on students’ performance in higher education. PloS one, 15(10), e0239490. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0239490

- Gruzdev, M. V., Kuznetsova, I. V., Tarkhanova, I. Y., & Kazakova, E. I. (2018). University graduates’ soft skills: the employers’ opinion. European Journal of Contemporary Education, 7(4), 690–698. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1200952.pdf

- Haltiwanger, J. C. (2022). Entrepreneurship during the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from the business formation statistics. Entrepreneurship and Innovation Policy and the Economy, 1(1), 9–42. https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w28912/w28912.pdf

- Hamza, C. A., Ewing, L., Heath, N. L., & Goldstein, A. L. (2021). When social isolation is nothing new: A longitudinal study on psychological distress during COVID-19 among university students with and without preexisting mental health concerns. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie Canadienne, 62(1), 20. https://doi.org/10.1037/cap0000255

- Hidayati, A., Budiardjo, E. K., & Purwandari, B., “Hard and soft skills for scrum global software development teams,” in Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Software Engineering and Information Management, 2020, pp. 110–114.

- Ioannidou, F., & Konstantikaki, V. (2008). Empathy and emotional intelligence: What is it really about? International Journal of Caring Sciences, 1(3), 118. http://www.internationaljournalofcaringsciences.org/docs/Vol1_Issue3_03_Ioannidou.pdf

- Jaggars, S. S. (2014). Choosing between online and face-to-face courses: Community college student voices. American Journal of Distance Education, 28(1), 27–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/08923647.2014.867697

- Jalali, R., Khazaei, H., Paveh, B. K., Hayrani, Z., & Menati, L. (2020). The effect of sleep quality on students’ academic achievement. Advances in Medical Education and Practice, 11, 497. https://doi.org/10.2147/AMEP.S261525

- Kamysbayeva, A., Koryakov, A., Garnova, N., Glushkov, S., & Klimenkova, S. (2021). E-learning challenge studying the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Educational Management.

- Kanwar, A., & Carr, A. (2020). The impact of covid-19 on international higher education: New models for the new normal. Journal of Learning for Development, 7(3), 326–333. https://doi.org/10.56059/jl4d.v7i3.467

- Kaparounaki, C. K., Patsali, M. E., Mousa, D.-P. V., Papadopoulou, E. V., Papadopoulou, K. K., & Fountoulakis, K. N. (2020). University students’ mental health amidst the COVID-19 quarantine in Greece. Psychiatry Research, 290, 113111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113111

- Killgore, W. D., Cloonan, S. A., Taylor, E. C., & Dailey, N. S. (2020). Loneliness: A signature mental health concern in the era of COVID-19. Psychiatry Research, 290, 113117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113117

- Konak, A., & Kulturel-Konak, S. (2019). Impact of online teamwork self-efficacy on attitudes toward teamwork. International Journal of Information Technology Project Management (IJITPM), 10(3), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.4018/IJITPM.2019070101

- Lades, L. K., Laffan, K., Daly, M., & Delaney, L. (2020). Daily emotional well‐being during the COVID‐19 pandemic. British Journal of Health Psychology, 25(4), 902–911. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjhp.12450

- Letourneau, J. L. (2015). Infusing qualitative research experiences into core counseling curriculum courses. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 37(4), 375–389. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10447-015-9251-6

- Li, S. (2021). How does COVID-19 Speed the digital transformation of business processes and customer experiences? Review of Business, 41(1), 1–14. https://usiena-air.unisi.it/retrieve/handle/11365/1180047/445029/Review-of-Business-41%281%29-Jan-2021.pdf#page=5

- Maguire, M., & Delahunt, B. (2017). Doing a thematic analysis: A practical, step-by-step guide for learning and teaching scholars. All Ireland Journal of Higher Education, 9(3). https://ojs.aishe.org/index.php/aishe-j/article/view/335

- Malik, A., & Ahmad, W. (2020). Antecedents of soft-skills in higher education institutions of Saudi Arabia study under COVID-19 pandemic. Creative Education, 11(7), 1152–1161. https://doi.org/10.4236/ce.2020.117086

- Martínez Lirola, M. (2021). Promoting intercultural competence and social awareness through cooperative activities in higher education. https://ajal.faapi.org.ar/ojs-3.3.0-5/index.php/AJAL/article/view/7

- Matturro, G., Raschetti, F., & Fontán, C. (2019). A Systematic Mapping Study on Soft Skills in Software Engineering. Journal of Universal Computer Science: J. UCS, 25(1), 16–41. https://d1wqtxts1xzle7.cloudfront.net/59130321/19_JUCS_A_systematic_mapping_study_on_soft_skills_in_software_engineering20190505-130120-139nnsq-libre.pdf?1557178124=&response-content-disposition=inline%3B+filename%3DA_Systematic_Mapping_Study_on_Soft_Skill.pdf&Expires=1675204582&Signature=S9PfalDBJEM5aHNgcjfHZJ7G5k6-FtKqA2OdN22T090Pux~nQ55T4lcT3drnKoXKzZK7METdroAFAwhiiWZw0PP~3PsdvWCYB7L8pKaSTxwlyqbNyr9muk49rNg4QBpwj082Zk0guyxFQpOdwmqzB2vvaxIWzkZSPMCDnVRWlwaZMTunFO58fIr54Q9AM89YDtKA1xf5pAq3TwboeFs~1fjvb993feDNGpbohSLszmT5dVotpQb1er4uvOH1KnIyV7r2E9gPJq~By9JxUvLmCPbxONPd06mCabz2MyK5Iesh3-OQShp0QArMCJgWHZVvh2vUbzRUwvBBmXAs8q392w__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAJLOHF5GGSLRBV4ZA

- McAvoy, J., Dempsey, M., & Quinn, E. (2020). Incremental learning in a capstone project: not all mature students are the same. International Journal of Innovative Teaching and Learning in Higher Education (IJITLHE), 1(2), 1–15. https://www.igi-global.com/gateway/article/full-text-pdf/260945&riu=true

- Minocha, S., Hristov, D., & Reynolds, M. (2017). From graduate employability to employment: Policy and practice in UK higher education. International Journal of Training and Development, 21(3), 235–248. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijtd.12105

- Mok, K. H., Xiong, W., & Ye, H. (2021). COVID-19 crisis and challenges for graduate employment in Taiwan, Mainland China and East Asia: A critical review of skills preparing students for uncertain futures. Journal of Education and Work, 34(3), 247–261. https://doi.org/10.1080/13639080.2021.1922620

- Morrison-Smith, S., & Ruiz, J. (2020). Challenges and barriers in virtual teams: A literature review. SN Applied Sciences, 2(6), 1–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-020-2801-5

- Naamati Schneider, L., Meirovich, A., & Dolev, N. (2020). Soft Skills On-Line Development in Times of Crisis. Romanian Journal for Multidimensional Education/Revista Romaneasca Pentru Educatie Multidimensionala, 12. https://web.p.ebscohost.com/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=0&sid=8b23e870-f8ae-4706-993e-3c826ec8991b%40redis

- Nayak, S. G. (2019). Impact of Procrastination and time-management on academic stress among undergraduate nursing students: A cross sectional study. International Journal of Caring Sciences, 12(3). https://internationaljournalofcaringsciences.org/docs/18_nayak_original_12_3.pdf

- O’Dea, M., Brennan, A., & Dempsey, M., “Supporting online students through the liminal space from facilitated online modules to self-starting a thesis,” in 12th International Technology, Education and Development Conference, 2018: International Academy of Technology, Education and Development (IATED).

- Parker, S. W., Hansen, M. A., & Bernadowski, C. (2021). COVID-19 campus closures in the United States: American student perceptions of forced transition to remote learning. Social Sciences, 10(2), 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10020062

- Ping, W., & Xiaochun, W. (2018). Effect of time management training on anxiety, depression, and sleep quality. Iranian Journal of Public Health, 47(12), 1822. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6379615/

- Sasere, O. B., & Makhasane, S. D. (2020). Global perceptions of faculties on virtual programme delivery and assessment in higher education institutions during the 2020 COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Higher Education, 9(5), 181–192. https://doi.org/10.5430/ijhe.v9n5p181

- Schmidt, C., Kude, T., Tripp, J., Heinzl, A., & Spohrer, K. (2013). Team adaptability in agile information systems development. https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=de290a361273e8c12939b31d1aad38554565fe3a.

- Shabir, S., & Sharma, R. (2019). Role of soft skills in tourism industry in Saudi Arabia. International Journal of Engineering and Management Research, 9. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3479585

- Shahzad, A., Hassan, R., Aremu, A. Y., Hussain, A., & Lodhi, R. N. (2021). Effects of COVID-19 in E-learning on higher education institution students: The group comparison between male and female. Quality & Quantity, 55(3), 805–826. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-020-01028-z

- Shiohira, K., & Keevy, J., “Virtual conference on artificial intelligence in education and training: virtual conference report. UNESCO-UNEVOC TVeT Forum, 11 to 15 November 2019,” UNESCO-UNEVOC International Centre for Technical and Vocational Education and Training, 2020

- Skinner, C., & Spurgeon, P. (2005). Valuing empathy and emotional intelligence in health leadership: A study of empathy, leadership behaviour and outcome effectiveness. Health Services Management Research, 18(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1258/0951484053051924

- Smith, B. W., Dalen, J., Wiggins, K., Tooley, E., Christopher, P., & Bernard, J. (2008). The brief resilience scale: Assessing the ability to bounce back. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 15(3), 194–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705500802222972

- Son, C., Hegde, S., Smith, A., Wang, X., & Sasangohar, F. (2020). Effects of COVID-19 on college students’ mental health in the United States: Interview survey study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(9), e21279. https://doi.org/10.2196/21279

- Sultana, A., Tasnim, S., Hossain, M. M., Bhattacharya, S., & Purohit, N. (2021). Digital screen time during the COVID-19 pandemic: A public health concern. F1000Research, 10(81), 81. https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.50880.1

- Tahara, M., Mashizume, Y., & Takahashi, K. (2021). Mental health crisis and stress coping among healthcare college students momentarily displaced from their campus community because of COVID-19 restrictions in Japan. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(14), 7245. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18147245

- Tang, K. N. (2019). Beyond employability: embedding soft skills in higher education. Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology-TOJET, 18(2), 1–9. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1211098

- Tang, J., Zhang, S. X., & Lin, S. (2021). To reopen or not to reopen? How entrepreneurial alertness influences small business reopening after the COVID-19 lockdown. Journal of Business Venturing Insights, 16, e00275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbvi.2021.e00275

- Todt, G., Weiss, M., & Hoegl, M. (2018). Mitigating negative side effects of innovation project terminations: The role of resilience and social support. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 35(4), 518–542. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpim.12426

- Tseng, H., Yi, X., & Yeh, H.-T. (2019). Learning-related soft skills among online business students in higher education: Grade level and managerial role differences in self-regulation, motivation, and social skill. Computers in Human Behavior, 95, 179–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.11.035

- Tus, J. (2020). The influence of study attitudes and study habits on the academic performance of the students. IJARW| (O), 2, 4. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3717274

- Twenge, J. M. (2017). iGen: Why today’s super-connected kids are growing up less rebellious, more tolerant, less happy–and completely unprepared for adulthood–and what that means for the rest of us. Simon and Schuster.

- U. I. B. o. Education., “Soft skills,” n d. http://www.ibe.unesco.org/en/glossary-curriculum-terminology/s/soft-skills

- UNESCO., “Sustainable development goal 4 and its targets,” n d: https://en.unesco.org/education2030-sdg4/targets

- Vogler, J. S., Thompson, P., Davis, D. W., Mayfield, B. E., Finley, P. M., & Yasseri, D. (2018). The hard work of soft skills: Augmenting the project-based learning experience with interdisciplinary teamwork. Instructional Science, 46(3), 457–488. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11251-017-9438-9

- WHO, ”Depression: Key Facts,” 2020. [Online]. Available: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression.

- Winter, L.-C., Kopeinik, S., Albert, D., Dimache, A., Brennan, A., & Roche, T., “Applying pedagogical approaches to enhance learning: Linking self-regulated and skills-based learning with support from Moodle extensions,” in 2013 Second IIAI International Conference on Advanced Applied Informatics, 2013: IEEE, pp. 203–206.

- Wong, J., Baars, M., Davis, D., Van Der Zee, T., Houben, G.-J., & Paas, F. (2019). Supporting self-regulated learning in online learning environments and MOOCs: A systematic review. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction, 35(4–5), 356–373. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2018.1543084

- Young, I. (2015). Practical empathy: For collaboration and creativity in your work. Rosenfeld Media.

- Zhai, W., & Yue, H. (2022). Economic resilience during COVID-19: An insight from permanent business closures. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 54(2), 219–221. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X211055181

- Zhang, Y., Zhang, H., Ma, X., & Di, Q. (2020). Mental health problems during the COVID-19 pandemics and the mitigation effects of exercise: A longitudinal study of college students in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(10), 3722. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17103722