Abstract

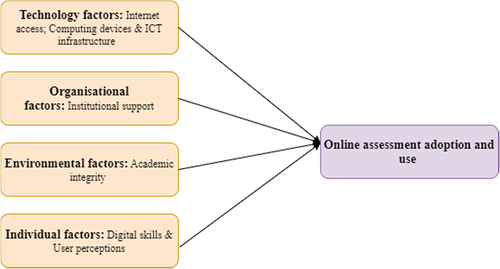

The purpose of this study was to investigate the key factors affecting the adoption and use of online assessment in Polytechnics in Zimbabwe during the COVID-19 era using the Technology-Organisation-Environment (TOE) framework and Technology Acceptance model (TAM). A qualitative research methodology was employed to discover and explain the adoption factors of online assessment for learning based on the participants’ experiences. Data were collected from lecturers and students from Harare Polytechnic using semi-structured interviews. Total of 10 students and five lecturers were purposively selected from five Departments. The factors affecting the adoption and use of online assessment were coded using Template analysis and classified based on the theoretical lens of the integration of the TOE framework and TAM. The study reveals that the adoption and use of online assessment in Polytechnics depend on technological factors (internet access, computing devices, and ICT infrastructure), organisational factors (institutional support), environmental factors (academic integrity), and individual factors (digital skills and user perceptions). This study concludes that online assessment is no longer a choice for tertiary education institutions since COVID-19 has presented a mandatory environment for its adoption. As far as theoretical contributions of this study are concerned, the study extends the TOE framework by explaining how the individual factors, for instance, the digital skills and user perceptions influence the successful adoption of technology in mandatory environments such as online assessment during COVID-19. In terms of practical contributions, the extended TOE framework can be used as a valuable point of reference for scaling up the adoption and use of online assessment in Polytechnics. The study recommends that both lecturers and students should be trained on the usage of an online assessment.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Online assessment in tertiary education institutions has been in practice for more than two decades. Nevertheless, online assessment in tertiary education has increased rapidly during the past two years due to its inevitable benefits in critical situations such as COVID-19. Online assessment is no longer a choice for tertiary education institutions since COVID-19 has presented a mandatory environment for its adoption. The pandemic has accelerated the move from physical, face-to-face assessment to online, copiously remote assessment. However, not all tertiary education institutions have successfully adopted this assessment practice. Using the extended TOE framework, the study investigated the factors affecting the adoption and use of online assessment for learning in Polytechnics in Zimbabwe. The study concludes that the adoption and use of online assessment depend on technological factors (internet access, computing devices and ICT infrastructure), organisational factors (institutional support), environmental factors (academic integrity) and individual factors (digital skills and user perceptions).

1. Introduction

Globally, the emergency of the COVID-19 pandemic which necessitated national lockdowns and working virtually to practice social distancing as measures to contain the spread of the virus caused a major disruption to education in the last two years (Chakraborty et al., Citation2021; Das et al., Citation2022; Reedy et al., Citation2021; Yong et al., Citation2021). All the educational institutions once come to a halt due to the closure of campuses and premises since according to Chakraborty et al. (Citation2021), “no [education institution] was ready for a complete shift to online education” (p. 358). The COVID-19, thus, caused learning institutions to continuously suspend face-to-face activities. In that way, increasing the need for flexibility and adaptability, while hastening the inclination towards online teaching and learning (Chandra, Citation2021; Haus et al., Citation2020; Mate & Weidenhofer, Citation2022; Rayan et al., Citation2021). Nevertheless, teaching and learning can never be complete without conducting assessment because the latter determines whether education goals are met.

Assessments are a particularly essential and indispensable element of tertiary education since they are used to guarantee the quality of knowledge and competencies of degrees, diplomas and certificates (Bashitialshaaer et al., Citation2021). So, the pandemic has brought about the abrupt requirement for online assessment; as a result, causing many tertiary education institutions to rapidly switch to online assessment platforms (Butler-henderson & Crawford, Citation2020; Chakraborty et al., Citation2021; Mate & Weidenhofer, Citation2022; Reedy et al., Citation2021) and Polytechnics have not been left untouched. Therefore, online assessment is no longer a choice for the tertiary institution and COVID-19 has presented a mandatory environment for its adoption.

Several online assessment platforms have appeared. These include, but are not limited to, Quizlet, Socrative, iSpring Suite, Google Forms, Microsoft Forms and Qorrect for Online Assessments. However, successful adoption and use of online assessment have been a challenge for the educational institutions and the researchers’ experience shows that it has remained minimal in Polytechnics. Besides, previous studies on online assessment have often focused on learning management systems (see, Ahmed & Mesonovich, Citation2019; Alturki, Citation2021; Cavus & Mohammed, Citation2021; Grönlund et al., Citation2021; Kant et al., Citation2021; Steindal et al., Citation2021). Chapman affirms that studies that focus on online assessment are comparatively low; as such, there is a dearth of knowledge on how tertiary education institutions can effectively adopt and use online assessment. Few studies during the COVID-19 pandemic have been conducted to examine the adoption of online examination (Yong et al., Citation2021), the implications of transitioning to online assessment (Mate & Weidenhofer, Citation2022), consider effective and authentic online assessment tools (Butler-henderson & Crawford, Citation2020), propose online examination adoption framework (Ngqondi et al., Citation2021), and students attitudes towards online examinations (Reedy et al., Citation2021).

However, these studies do not capture the key factors that affect the adoption and use of online assessment in Polytechnics, making the phenomenon a theoretical and practical problem. There is no unified view of factors that influence the adoption of online assessment in Polytechnics; only a few researchers have covered these issues. For example, Bashitialshaaer et al. (Citation2021) report that using online assessment is still a challenge since approximately half of all learners worldwide do not have access to computing devices while 40% have no internet access at home. This study aimed to examine the factors affecting Polytechnics in the adoption and use of online assessment during the COVID-19 pandemic. Besides, the study responds to the call for further research by Butler-henderson and Crawford (Citation2020) on the need for adding to the literature on factors to the adoption of online assessment practice. Also, due to differences in context, factors observed from literature cannot be directly transferred to the context that is implementing online assessment for the first time, for instance, Polytechnics in Zimbabwe. To fill this gap, the following research question was developed:

What are the key factors affecting the adoption of online examinations at polytechnics in Zimbabwe during the COVID-19 era?

What are the key factors affecting the use of online examinations at polytechnics in Zimbabwe during the COVID-19 era?

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: Section 2 presents literature review on the online assessment. Section 3 and 4 explain the theoretical framework and methodology of the study in detail respectively. Section 5 presents the findings and discussions. Section 6 presents the contributions of the study. Lastly, section 7 provides conclusions and recommendations.

2. Literature review

2.1. The concept of online assessment

Online assessment, also known as electronic assessment or e-assessment is a comparatively more open and flexible learning platform that is becoming more popular than a pencil-and-paper and a primary mode of assessment in tertiary education (Elsalem et al., Citation2021; Yong et al., Citation2021). This mechanism of assessment is usually done on e-learning platforms without the physical presence of students and lecturers at the same venue and has the added benefit of enabling rapid and specific feedback to large cohorts of students on their performance. Feedback allows learners to target their fallible spots for remediation. Online assessment is becoming a preferred way of assessment in both online and traditional learning environments due to a great advantage to the lecturers and the learners if used efficiently (Ali et al., Citation2021; Iskandar et al., Citation2021; Mate & Weidenhofer, Citation2022). For example, online assessment help lecturers to shorten the time spent preparing and managing the assessment period (Rayan et al., Citation2021). E-assessment can be thought of as the use of ICTs to streamline every aspect of assessment, from creating and distributing assignments to marking them (either automatically or with the aid of digital tools), reporting, storing the findings, and/or performing statistical analysis (Swaffield, Citation2011). It has enhanced the measurement of learner outcomes and made it possible for them to obtain immediate and direct feedback-assessment has improved how learner outcomes are measured and made it feasible for them to get quick feedback.

Accordingly, online assessment is an important component of e-learning solutions that provide a true and fair assessment of students’ performance. Online assessments are superior to traditional assessments because of immediate feedback, auto-grading, automated record-keeping and ease of preparation and schedule (Mate & Weidenhofer, Citation2022; Shakeel et al., Citation2021). Online essays and computer-marked online exams are just two examples of the wide variety of assessment activities that are included in online assessment, or e-assessment (Theresa et al., Citation2021). Online assessment and e-assessment are used interchangeably because both concepts serve the same purpose and use technology to manage and deliver assessments which can be diagnostic, summative, or formative (Huda & Siddiq, Citation2020). Thus, practically, online assessment is a novel approach in online teaching and learning designed to solve traditional assessment challenges.

In online assessment, there are three types: Assessment for learning, Assessment as learning, and Assessment of learning. AaL, AfL, and AoL represent different and valuable assessment and learning approaches. According to Schellekens et al. (Schellekens et al., Citation2021, p. 2), “Assessment for Learning is the process of seeking and interpreting evidence for use by learners and their teachers to decide where the learners are in their learning, where they need to go and how best to get there”. On the other hand, AaL refers to a method by which student involvement in assessment can be featured as part of learning. One of the key features of Aal is feedback. It is considered a subset of assessment for learning that stresses using assessment as a process of using assessment to create and support meta-cognition for students (Dann, Citation2014; Lee et al., Citation2019; Swaffield, Citation2011). As a result, AaL emphasises the student-centered aspect of AfL by extending and reinforcing the function of AfL by placing students at the centre of assessment and learning. The theories of metacognition, self-regulation, motivation, and autonomy serve as the theoretical foundation for AaL. Students gain metacognitive awareness of their own thought processes and the methods they employ to enhance learning through AaL, which helps them build this capacity. The ultimate objective of AaL is to foster learners’ capacity for self-regulation to support their pursuit of lifelong learning and personal growth.

AOL in contrast represents the measurement of learning by using assessments. Lee et al. (Citation2019) maintain that AoL performs primarily the reporting and administrative functions, where students’ performance and progress are assessed against some specified learning targets and objectives. This study investigated the phenomenon of online assessment in the context of AfL. It differs from formative assessment in its timeline, protagonists, beneficiaries, the role of students, the student-teacher interaction, and the importance of learning to the process. However, not all of these characteristics must be present (Swaffield, Citation2011). This is because AfL aims to close the learning gap by monitoring student progress against reference standards and providing continuous feedback. AfL focuses on the improvement of learning and teaching (Lee et al., Citation2019). Students, teachers, and peers engage in AfL every day, seeking, reflecting, and enhancing ongoing learning. Thus, students and teachers are the main agents in the learning process; hence, assessment should provide effective feedback mechanisms.

2.2. Factors influencing the adoption of online assessment

Globally, the adoption of online assessment in tertiary education has attracted the attention of scholars. Rayan et al. (Citation2021) analysed the challenges of robust electronic examination performance under COVID-19. The authors found that the internet speed, cost, and authenticity were the most challenges faced by e-exams centres, which were 99%, 82%, and 68%, respectively. The findings show that internet connectivity has a higher effect on the adoption of an online assessment. To identify perennial factors in the adoption of online assessment, the researchers included two authors which conducted a systematic literature review. For instance, Muzaffar et al. (Citation2021) performed a systematic review of online examination from 55 studies conducted between 2016 and 2020. The review identified four key online assessment adoption factors: network infrastructure, hardware requirements, implementation complexity, training requirement. On the other hand, Ngqondi et al. (Citation2021) conducted a systematic literature review to discern the academic threats in using the online examination. The authors reported that electronic examinations have always been shunned because of a perceived lack of academic integrity.

Similarly, Reedy et al. (Citation2021) used mixed-method research to explore the perceptions of lecturers and learners to student cheating behaviours in online assessment. The authors found that examinations in a digital world are susceptible to cheating. The study concluded by giving suggestions for enhancing academic integrity in digital examinations and assessments. Ngqondi et al. proposed an online examination implementation process grounded in the context of South Africa. Although the authors claimed that the proposed framework can provide universities with initial guidelines for the adoption of online examination, the solution cannot be suitable for all tertiary institutions due to differences in contextual characteristics. Accordingly, contexts, where the electronic examination is used, differ widely (Bashitialshaaer et al., Citation2021); therefore, there is a need for context-specific studies.

In the context of Palestine Universities, Bashitialshaaer et al. (Citation2021) used an exploratory descriptive approach with a sample of 300 drawn from lecturers and learners to identify and understand the obstacles and barriers in the successful adoption of electronic examinations. The findings revealed that power outages, unreliable internet access and the digital divide were the key factors that influence the adoption of an online assessment. The authors concluded that disparities in access to suitable devices or the internet pose a major concern in the usage of online examinations. Reliable internet connectivity ensures that digitally mediated assessment is sustainable. According to Das et al. (Citation2022), an online examination can be affected by digital level efficiency and willingness to adapt and accept the system. Also, Chakraborty et al. (Citation2021) claim that stable connectivity to the internet and digital skills are a precondition for online learning. Online assessment requires a stable and high-speed internet connection. As a result, lecturers and learners who have poor connectivity to the internet and lack digital skills are likely to face problems in using online assessment platforms. Shakeel et al. (Citation2021) maintain that the adoption of online assessment is largely constrained by the digital divide, too. Besides, not all lecturers and students have equal access to, and expertise on online technologies. While these inequalities existed prior, the COVID-19 pandemic has exposed this digital divide. This is attributed to the fact that the pandemic has introduced a paradigm shift to online education. Thus, part of the findings suggests that online assessment is more relevant to “digital-native” lecturers and learners (Mate & Weidenhofer, Citation2022). Therefore, poor internet connectivity, lack of access to the internet and lack of digital skills results in partial adoption of the online assessment.

The studies from various tertiary education institutions show that online assessment is worth adopting and using, but that there are still some challenges in its usage (Das et al., Citation2022); hence, the issue requires further investigation. The literature drawn from google scholar and SCOPUS listed publications suggest that relatively little of the research conducted touches on the online assessment. Several studies focused on electronic examination, not the entire online assessment. Only four studies slightly touched on the focus for the present study. For instance, Ghanbari and Nowroozi (Ghanbari, Citation2021) conducted an in-depth semi-structured retrospective interview with the teachers at Persian Gulf University to determine the online assessment challenges posed by COVID-19. The analysis of the findings showed that the adoption of online assessment depends on pedagogical, technical, administrative, and affective factors.

Alruwais et al. (Citation2018) investigated the benefits and drawbacks of using e-assessment in learning for different domains. The authors reported that the challenges faced in e-assessment are poor technical infrastructure and a lack of digital skills. Lack of digital skills and internet connectivity was also reported by Ali et al. (Citation2021) as factors affecting the transition to online assessment. In another study, Guangul (Citation2020) examined the challenges of remote assessment during the COVID-19 incident in higher education institutions that were taking Middle East College as a case study. The study identified four distinct challenges: academic dishonesty, infrastructure, coverage of learning outcomes, and commitment of students to submit assessments. Nevertheless, by focusing exclusively on adoption challenges, previous studies are likely to miss out on the factors that enable the adoption of online assessment since challenges only reveal constraining mechanisms. Hence, there is a need to employ a theoretical framework that houses both constraining and enabling mechanisms in the adoption and use of technology.

3. The theoretical framework of the study

The existing literature offers a variety of theoretical frameworks and models that try to explain technology adoption and usage behaviors. Among them are theory of reasoned action (TRA; Fishbein & Ajzen, Citation1976), Technology Acceptance Model (TAM; Davis, Citation1989), theory of planned behaviour (TPB; Ajzen, Citation1991), diffusion of innovation (DOI) theory (Rogers, Citation2003), and technology-organization-environment (TOE; Tornatzky & Fleischer, Citation1990). One of the earliest theories is the DOI theory (Rogers, Citation2003), which asserts that four factors—innovation, communication channel, time, and social system—influence the proliferation of any new technology. The theory seeks to explain the process by which users adapt technological advances. The human perspective on adoption behaviour, however, was not considered by this theory. The TOE theory is developed to describe the organizational components that affect a firm’s adoption decision of new technology (Awa et al., Citation2016). The theory identifies three dimensions under which adoption factors of technological, organizational, environmental fall. These dimensions present both constraining and enabling mechanisms for technology adoption and use. The main drawback of TOE, however, is that several of the constructs in the adoption predictors are thought to apply more to large enterprises, where customers are certain of continuity and have less complaints (Awa et al., Citation2016).

Fishbein and Ajzen (Citation1976) proposed the TRA, which has its foundations in social psychology, to address the problem of technology adoption. According to TRA, a user’s attitude about a technology and societal norms can influence his behavioural intention to use that technology. This behavioral intention is more likely to be converted into action (actual usage). Ajzen (Citation1991) developed the theory of planned behavior (TPB) by adding another construct—perceived behavioral control to the TRA. The term “perceived behaviour control” refers to how easy or difficult a user thinks it will be to embrace a new technology (Scherer et al., Citation2019). TPB, however, disregarded the effects of psychological, social, and interpersonal factors on the choice to adopt technology. Theresa et al. (Citation2021) believed that TPB explanatory and predictive utilities are better enhanced by extending and integrating with TAM; hence, Davis (Davis, Citation1989) proposed TAM based on Fishbein and Ajzen’s Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA). Both TAM and TPB are routed to the theory of reasoned action (TRA). TAM has been applied in a variety of contexts to examine the adoption and usage of innovations. The model suggests that two components, namely perceived usefulness, and perceived ease of use, can explain the intention to embrace a specific technology. Due to its robustness, simplicity, and relevance in a variety of technology adoption scenarios, TAM has evolved over time into one of the most popular theories to explain technology adoption behaviour. According to the model, a person’s intention to use an application is anticipated and described by how useful and simple she/he thinks the technology is.

By using technology, TAM2 expands on this approach. This is due to the observation that empirical studies of the TAM frequently fail to correlate usage intentions with actual use, which is why Model 1 was expanded (Ansong et al., Citation2017; Awa et al., Citation2016; Ghanbari, Citation2021; Kaushik & Verma, Citation2020; Nguyen et al., Citation2022; Theresa et al., Citation2021). Due to the TAM’s limitations in terms of explanatory power (R2), TAM2, an extension of the TAM, was created. The goal of the TAM2 was to maintain the original TAM constructs while also including additional significant determinants of TAM’s perceived usefulness and usage intention constructs (Na et al., Citation2022; Scherer et al., Citation2019). Additionally, it was intended to better understand how these determinants’ effects changed as users gained more experience using the target system.

Unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT) is one of the most modern and widely recognised theories of technology adoption and is gradually replacing TAM as the most frequently used and cited theory (Nguyen et al., Citation2022; Tan, Citation2013). The most important determinants of technology adoption behaviour, according to the model, are four fundamental constructs: performance expectancy, effort expectancy, social influence, and facilitating factors. The UTAUT is built up similarly to the TAM, and the notion of the determinants is similar as well (Awa et al., Citation2016; Kaushik & Verma, Citation2020; Na et al., Citation2022; Nguyen et al., Citation2022; Qin et al., Citation2020; Scherer et al., Citation2019; Tan, Citation2013). Despite being more challenging to test than the TAM (because of the expected effects of moderation), this model is regarded as an additional, potent model of technological acceptance. Although the UTAUT model has been widely adopted, doubts exist over its capability to explain individuals’ technology acceptance (Tan, Citation2013). Just two examples of technology acceptance models are the TAM and the UTAUT. Although there are many different models, the TAM is the one that is most frequently used in research to represent both usage intentions and actual technology use. At the same time, the TAM falls short of conceptualizing what it means to accept and integrate technology in the discourse of digital learning. There are several reasons, therefore, why other acceptance models developed after TAM should not be taken into consideration. For instance, the strongly linked variables in these models lead to an unrealistically high explained variance (Chatterjee et al., Citation2021).

The study integrated the TOE theory and the TAM to investigate the factors affecting the adoption and use of online assessment in Polytechnics in Zimbabwe. According to Awa, Ukoha and Emecheta (Awa Ojiabo, Citation2015, p. 80), “Integrating TOE with other models such as TAM, with each adoption predictor offering larger number of constructs than the original, provides richer theoretical lenses to the understanding of adoption behaviour”. This is because individually, these frameworks do not provide a comprehensive lens to dissect technology adoption and usage. The TOE-TAM hybrid model is perceived as appropriate in this study since it is possible to cover all the internal and external antecedents for the adoption of online assessment for learning at Polytechnics. Likewise, TAM provides more complete constructs for understanding technology usage at individual level. At least 40% of the justifications for utilizing the system can be explained by the two main components of TAM, namely perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness (Chatterjee et al., Citation2021). On the other hand, the TOE is a suitable and holistic instrument for organizational-level research like Polytechnics because it overarches the technical aspects of online technologies and the external (environmental) and internal organisational factors that make successful adoption and use of online assessment.

The theories of TOE and TAM are frequently used to support numerous IS studies that explain end-user adoption at the organisational and individual levels, respectively (Ansong et al., Citation2017; Awa et al., Citation2016; Chatterjee et al., Citation2021; Mensah et al., Citation2022; Na et al., Citation2022; Nguyen et al., Citation2022; Qin et al., Citation2020). These theories especially target the acceptance of technology (Awa et al., Citation2016). TAM is likened to the technology construct of TOE on the grounds of the postulates of PU and PEOU. The TOE framework overcomes the illusion of accumulated traditions and techno-centric predictions of most other frameworks (e.g., TAM, TRA, UTAUT, and TPB) by incorporating both human and non-human players into the network. Furthermore, the application of the theory can enable the prediction of challenges and the factors that influence the adoption decisions of online assessment and better development of organizational capabilities through technology. In addition, the theory is appropriate for this study since tertiary institutions are business units with underlying structures that may generate composite factors related to technology, organisation, the environment and individuals capable of influencing the adoption and use of online assessment for learning at tertiary education institutions. Thus, these elements influence the way Polytechnics perceive the need to adopt and use online assessment for learning.

The TAM model and its later versions, such as TAM2 and UTATUT, assessed people’s attitudes toward innovations, such as perceived usefulness and ease of use (Ansong et al., Citation2017; Ghanbari, Citation2021; Kaushik & Verma, Citation2020; Nguyen et al., Citation2022; Tan, Citation2013). On the other hand, because it is based on tripartite aspects like Technology, Organization, and Environment, TOE has better strength and precision in measuring the acceptance of technology in the organisational environment (Awa et al., Citation2016; Mensah et al., Citation2022; Nguyen et al., Citation2022). The TOE framework provides a thorough explanation of the variables influencing adoption choices. With the use of technological, organisational, environmental dimensions and individual attributes, the TOE-TAM integrated framework can explain adoption of any contemporary technology in the context of its socio-environmental and technological aspects. To establish comprehensiveness in adopting and implementing online assessment technology from both an individual and an organisational standpoint, a model based on TAM and TOE was developed in this study as shown in Figure .

Figure 1. Integrated TOE-TAM framework for adoption and usage of online assessment for learning

4. Research methodology

A qualitative research methodology was employed to discover and explain the adoption factors of online assessment based on the participants’ experiences. Qualitative research posits that meaning is derived from the interaction between the subject and object of inquiry (Hughes, Citation2019; Sage et al., Citation2014). The goal is to examine the text to uncover meanings that are deeply embedded in people’s minds. This means that truth and reality are a result of dialogical interaction since a human engagement with the practicalities of the world gives rise to meaning regarding reality. All the students who were exposed to online learning formed the target population of the study. Data were collected from lecturers who were directly involved in teaching and assessment and students (Reedy et al., Citation2021) from Harare Polytechnic. Ten (10) students and five (5) lecturers were purposively selected from five (5) Departments. Two (2) students were taken from each Department.

The researchers used a semi-structured interview guide comprising of a list of prepared questions related to the main research question to conduct the interview. The instrument was prepared based on recurring themes in corpus literature and was screened for accuracy and validity by four (4) researchers in the Department of educational Technology in Zimbabwe’s State Universities. Semi-structured interviews allowed the researchers to ask open-ended questions to ensure respondents give their broad perspective about the topic of the study. Interviews allowed researchers to probe the interviewee further or pursue a line of inquiry initiated by the interviewee and get an in-depth meaning of the feelings, perceptions, and attitudes of participants. Qualitative research shows that size does not matter when working with smaller more focused groups. It goes beyond figures to comprehend the participants’ thoughts and impressions.

The factors affecting the adoption and use of online assessment were coded and classified based on the theoretical codes: Technology, organisation, and environment. Thus, the explanatory nature of the framework and the factors associated with the framework are based on narratives of the interviewed participants, the codes, and the literature (Eze et al., 2018). The researchers transcribed the recorded interviews verbatim and the data were coded into themes and sub-themes using the Atlas.ti.7.5 software. The interviews were replayed several times to ensure the accuracy of the transcription (Adarkwah, Citation2021). The researchers used pseudonyms for each of the participants to ensure confidentiality. Students were coded S1 to S10 while lecturers were code L1 to L5 as mentioned in Table .

Table 1. Template for coding qualitative data

Table 2. Codes, themes and supporting cases from students and lecturers

A theme is defined as a recurring element in participants’ narratives regarding their views and experiences of a phenomenon that the researcher considers to be significant to the study. Themes are characteristics of participants’ narratives that characterize specific perceptions and experiences that the researcher considers to be relevant to the study issue. The purpose of coding texts is to get access to the main ideas and assess what is going on in the collected data. Such a process also allows amorphous data to be converted into ideas (Mahlangu, 2020). The researchers used a technique proposed by King (2004) known as the template analysis technique. It enables the researchers to create a catalogue of codes. The template analysis technique relies more on the creation of the coding template that gives summaries of themes found by the researcher (Sage et al., Citation2014.) as shown in Table while Table shows the measures taken to ensure quality of the findings.

Table 3. Measures taken to ensure the quality of the findings

5. Findings and discussions

The analysis of the findings of this study was based on the three dimensions of the TOE framework.

5.1. Technology factors

5.1.1. Internet access

Generally, the internet has allowed the implementation of e-learning services including online assessment; hence, several educational institutions have moved a great stride in administering online assessment before and during the COVID-19 pandemic (Ana & Bukie, Citation2013; Shen et al., Citation2004; Shraim, Citation2019; Yong et al., Citation2021). Nevertheless, the most obvious analysis of the findings shows that there is low adoption and usage of online assessment in Polytechnics in Zimbabwe due to the lack of internet access by both students and lecturers. Both students and lecturers indicated that they could not effectively conduct online assessments because most of them cannot afford to buy data bundles due to high costs. The following excerpts are part of the narratives from both cases:

Participant S5 said, “In terms of internet access, most students do not afford to purchase data bundles because the cost is out of reach for many of us. As a result, often, students would miss online examinations” (Lecturer, personal communication, 24 July 2021). This narrative was supported by Participant S1 who mentioned that: “Lack of access to the internet mostly due to limited data bundles would hinder the use of online examinations by both students and lecturers,” (Lecturer, personal communication, 24 July 2021). Similarly, Participant L2 mentioned that: “The cost of data is out of reach for many people. Most students and lecturers are unable to afford the exorbitant price of data. Consequently, it is difficult to administer or take an online assessment” (Lecturer, personal communication, 24 July 2021). Participant S10 said, “Implementation of online assessment can be difficult for students as it requires a stable internet connection and high-speed bandwidth” (Lecturer, personal communication, 24 July 2021).

This result is in line with the previous research which revealed two important aspects: first, approximately 40% of the learners globally have no internet access at home (Bashitialshaaer et al., Citation2021; Ullah & Biswas, Citation2022); secondly, lack of internet access poses a major concern in the usage of online assessment (Ali et al., Citation2021). Likewise, previous research shows that internet connectivity has a higher effect on the adoption of online assessment (Rayan et al., Citation2021). Online assessment requires stable internet and poor internet is a hindrance in the adoption and use of online assessment. As such, online assessment cannot be successfully conducted if there is a lack of internet access. The result strongly implies that the adoption and use of online examinations largely depend on sustained internet access; the lack of, therefore, will result in partial or no adoption at all. Accordingly, initiatives to provide subsidized data bundles for both lecturers and students should be considered.

5.1.2. Computing devices

Online assessment is a computer-mediated practice (Gamage, Citation2021) and computing devices have become an integral part of this practice. Most if not all online assessments are facilitated by computing devices. However, many students in tertiary education institutions do not have smartphones due to a lack of financial resources, inhibiting them from participating in online learning (Ullah & Biswas, Citation2022). The findings of this study reveal that most students and several lecturers in Polytechnics cannot afford to buy computers and other computing devices due to high costs. This has an undesirable impact on the use and adoption of online assessment in these institutions. The participants had the following to say:

Participant S4 said, “Online examinations have a high start-up cost. The high cost of computers and ICT equipment harms the uptake of online examinations. Computer laboratories at polytechnics have inadequate computers comparing the number of students who are within a department” (Student, personal communication, 24 July 2021). Participant L1 said, “In Zimbabwe, most students do not have access to a computer. A few have their laptops and computers at home. They also have limited internet connection” (Lecturer, personal communication,). Participant S1 said, “Some students only have access to a computer when they visit the computer labs at the institution during lectures and at times, they will be sharing a single computer for example, three students will be sharing a single computer” (Student, personal communication, 24 July 2021).

In the same vein, a lack of computers and/ or laptops was reported by Mohamed et al. (Citation2021) as the utmost barrier to e-learning services such as online assessments. Furthermore, this finding is consistent with that of Bashitialshaaer et al. (Citation2021) who reported that using online assessment is still a challenge since approximately half of all learners worldwide do not have access to computing devices. Taken together, the findings suggest that the lack of computing devices is attributed to the partial usage and adoption of online assessment at Polytechnics. It, therefore, entails those lecturers and students in Polytechnics may be unable to use online assessment due to a lack of computing devices.

5.1.3. ICT Infrastructure

ICT infrastructure has the potential to hasten the adoption of the online assessment. Nevertheless, lack of ICT infrastructures such as network, hardware, software and power supply is the fundamental problem in the adoption of online assessment world over (Bariu, Citation2020; Masue, Citation2020; Tshiningayamwe, Citation2020). Similarly, the findings obtained from interviews show that the lack of ICT infrastructure affects the adoption and usage of online assessment in Polytechnics. The current ICT infrastructure at Polytechnics is not able to handle the growing number of students taking online assessments since it was not designed to provide fully-fledged e-learning services. During the interviews, the participants had the following to say:

Participant S6 said: “Online assessment is somehow difficult to implement at Polytechnics due to lack of infrastructures such as computers, servers, uninterrupted power supply and software” (Student, personal communication, 24 July 2021). Participant S5 also said, “Monitoring of students during the online assessment will require security infrastructure such as biometric authentication. It will be quite expensive to purchase these security devices and it might take some time before an online assessment can be implemented” (Student, personal communication, 24 July 2021). Participant S3 mentioned that: “the availability of ICT infrastructure in Polytechnics is very poor and obsolete” (Student, personal communication, 24 July 2021).

From the above findings, it can be established that Polytechnics in Zimbabwe require adequate infrastructure for them to adopt online assessment. The findings match those observed in earlier studies. According to Bariu (Citation2020), most developing countries including those located in Sub-Sahara Africa have limited infrastructure that supports online learning, particularly, online assessment. Most educational institutions are not equipped with basic ICT infrastructure for teaching and learning. Similarly, the literature reveals that the lack of ICT infrastructure could be a serious impediment to the use of ICT to conduct an assessment (Masue, Citation2020; Permadi & Fathussyaadah, Citation2020; Stanciu et al., Citation2020). The setting up of ICT infrastructure in Polytechnics is therefore critical in the adoption and usage of the online assessment. Thus, this study concludes that the successful adoption and usage of online assessment in Polytechnics depends on sustainable infrastructure.

5.2. Organisational factors

5.2.1. Institutional support

The successful adoption of online assessment in Polytechnics demands institutional support from the College administration. The findings of this study show that the success of online assessment depends on institutional support as the deployment or improvement of ICT infrastructure requires financial resources. More importantly, participants cited a lack of financial support from the institution as a major drawback in the implementation of an online assessment. Thus, without financial support, it is almost impossible to implement an online assessment. During the interviews, the participants mentioned the following:

Participant S5 said, “There is a lack of financial support from the administration staff which hinders the deployment of prerequisite ICT infrastructure that supports online assessment” (Student, personal communication, 24 July 2021). Participant S2 said, “It takes ages for requests of ICT components to be approved. Consequently, this delays the deployment of ICT infrastructure” (Student, personal communication, 24 July 2021). Participant L3, “Online assessment should have a budget for resources and training” (Student, personal communication, 24 July 2021). Participant S3 mentioned that: “A budget should be set so that ICTs for online assessment can be purchased” (Student, personal communication, 24 July 2021).

These results corroborate the ideas of Pedro (Citation2020), who suggested that the transition from traditional to online learning necessitate various types of support to lecturers and students, especially when they have little to no experience with e-learning platforms. The author argued that the prevalent evolution of online learning services at tertiary education institutions necessitates institutional support for the development, implementation, and sustenance of online learning services. According to Ullah and Biswas (Ullah & Biswas, Citation2022, p. 1), “During COVID-19, institutional support is critical to closing the huge academic gap that has emerged as physical academic practices have been moved to a virtual education system using technology”. This shows that institutional support is the basis for the adoption of online assessment; hence, the lack of it could hinder the adoption and use of online assessment. Nevertheless, this study reveals that both lecturers and students had poor support from the College administration during COVID-19 to use online assessment.

5.3. Environmental factors

5.3.1. Academic integrity

Generally, assessments in a digital environment are vulnerable to cheating (Elsalem et al., Citation2021; Guangul, Citation2020; Holden et al., Citation2021) and it has drawn much attention from the lecturers. Therefore, without being able to authenticate a student’s environment and their actions off-camera, the integrity of online assessment cannot be guaranteed. Consequently, several lecturers in tertiary education institutions have persistently resisted the adoption of an online assessment.

Participant L3 said, “Students will never be honest in online assignments and tests; they are likely to cheat. Hence, I am always hesitant when it comes to administering online tests and other assessments” (Lecturer, personal communication, 24 July 2021). Participant L5 said, “I do not have the confidence to administer online assessments. Students always attempt to cheat in the eyes of the lecturer; what more online? So, unless there is a mechanism to track and monitor online assessment, administering online assessment is not encouraging at all” (Lecturer, personal communication, 24 July 2021).

As the demand for online learning increases in the COVID-19 era, there is a rising concern about the integrity of the online assessment practice. Previous studies that have noted the importance of online assessment in online learning environments have identified academic dishonesty as a grave threat to the integrity of such assessment (Guangul, Citation2020; Ngqondi et al., Citation2021; Reedy et al., Citation2021; Ullah et al., Citation2019). As mentioned in the literature review, in the course of the online assessment, assessment of the learning outcomes presents challenges largely due to academic dishonesty among students that may lead to biased evaluations (Reedy et al., Citation2021). Similarly, Ngqondi et al. (Citation2021) conducted a systematic literature review to discern the academic threats in using the online examination. The authors reported that electronic examinations have always been shunned by educators because of a perceived lack of academic integrity. Thus, while technology is a prerequisite for the adoption of online assessments, often, it is exploited by the students for academically dishonest behaviours. It is difficult for lecturers to monitor, control or prevent students to cheat in online environments. Therefore, there is a need for the enhancement of online assessment environments mediated by remote monitoring.

5.4. Individual factors

5.4.1. Digital skills

Literature reveals that lecturers and learners who lack digital skills are likely to face problems in using online assessment platforms since this type of assessment is conducted on digital platforms (Alruwais et al., Citation2018; Bashitialshaaer et al., Citation2021). Thus, digital skills are a precondition for the adoption and usage of an online assessment. On the same note, the findings of this study show that both lecturers and students in Polytechnics need to be equipped with digital skills to use online examination platforms. Lectures and students shared similar views as follows:

Participant S10 said, “A student may have difficulty in completing an online assessment if they have not received sufficient training on the use of online assessment platforms. Thus, if one does not possess digital skills, he or she may be unable to use online assessment tools effectively” (Student, personal communication, 24 July 2021). Other participants also raised the need to equip lecturers and students with digital skills to enhance the adoption and usage of an online assessment. Participant S4 said, “There is a need to train users of online assessment platforms for effective administration and usage of online assessment tools” (Student, personal communication, 24 July 2021). Participant S9 said, “Polytechnics should have a plan to carry out training on administering and using online assessment tools” (Student, personal communication, 24 July 2021). Participant L2 said, “The administration of online assessment tests in Polytechnics is limited due to lack of digital skills. Therefore, there is a need for the lecturers to be trained so that they will know how to create and administer online assessment tests” (Lecturer, personal communication, 24 July 2021).

These results seem to be consistent with other research which found that the adoption of online assessment is constrained by a lack of digital skills (Shakeel et al., Citation2021). For instance, Alruwais et al. (Citation2018) reported that lack of digital skills is one of the challenges faced in the adoption of e-assessment. In the same disposition, lack of digital skills was also reported by Ali et al. (Citation2021) as one of the factors affecting the transition to online assessment. Without digital skills, students and lecturers will find it difficult to use online assessment tools since these tools are digitally enabled. Generally, lecturers and students require dual digital skills: first to use computing devices and second to navigate online assessment platforms. However, little has been done to fix the digital skills deficit among the users of online assessment platforms in Polytechnics. Therefore, overcoming the digital skills gap among those who can or cannot effectively use online assessment could be one solution in enhancing the adoption of online assessment in Polytechnics. Thus, the authors argue that Polytechnics need to ensure that lecturers and students are trained to use online learning platforms effectively since not all have equal access to, and expertise on online technologies.

5.4.2. User perceptions

It is an indisputable fact that lecturers’ and the students’ perceptions play a crucial role in deciding whether to use online assessment (Iskandar et al., Citation2021). The findings of the study reveal that lecturers and students at Polytechnics in Zimbabwe have both positive and negative perceptions of the adoption of an online assessment. While some lecturers and students preferred online assessment methods over traditional assessments due to advantages brought about by using the former such as quick feedback, rapid administration, and transparency, those who encountered challenges such as poor network connections and lack of digital skills preferred traditional assessment methods. During the interviews, the participants had the following to say:

Participant S3 said, “I prefer online assessment platforms compared to pen and paper assessment. This is because, with online assessment, I do not have to be at the college campus. I can do it at home or on the go if I have internet connectivity! This method is very flexible indeed” (Student, personal communication, 24 July 2021). Similarly, participant S5 mentioned that: “I like the flexibility which online assessment has since I can do it and submit even when I am at home” (Student, personal communication, 24 July 2021). According to participant L2, “the administration of online assessment across courses is quick and flexible … with proper skills, it requires less effort compared to traditional assessment”. Participant L6 said, “With online assessment, there is improved speed and convenience of editing tasks since they are all designed using online platforms” (Lecturer, personal communication, 24 July 2021).

In contrary, participant S2 said that: “I do not really like online assessment since it favours students who have adequate digital skills to use online assessment tools. Moreover, I am not familiar with online assessment platforms due to my poor ICT background” (Student, personal communication, 24 July 2021). This was supported by participant S4 who indicated that: “I am not comfortable with the use of online assessment platforms because it favours students who are doing information technology programmes”. This narrative finds support from participant L3 who reported that: “We are still learning how to administer online assessment tasks … at times the process is frustrating due to lack of digital skills to navigate the platforms or network glitches” (Lecturer, personal communication, 24 July 2021).

Research on the perceptions of lecturers and students using online assessments has reported mixed findings. The studies revealed that the students have both positive and negative perceptions towards online assessment (Iskandar et al., Citation2021). According to Adanir et al. (Citation2020), students felt that online assessment provide significant advantages such as speedy feedback and unbiased grading. On the other hand, Iskandar et al. (Citation2021) reported that several students do not prefer online assessment due to unstable internet connection to submit assignments or attempt online quizzes and poor digital skills to navigate online assessment platforms. In addition, the literature also reports that lecturers and students who lack digital skills find online assessments stressful to use (Theresa et al., Citation2021). Similarly, a systematic literature review by Reedy et al. (Citation2021) reported the perceptions of lecturers and learners concerning the relative advantages and challenges of online examinations. Taken together, the findings reveal that online assessment is not suitable for all the users; benefits for online assessment are associated with positive perceptions while the challenges form the negative perceptions.

Therefore, Polytechnics need to identify and address the challenges that construct the negative perceptions of users. According to Theresa et al. (Citation2021), addressing these challenges is important because it influences their adoption of the technology. This suggests that the successful adoption and usage of online assessment in Polytechnics depends on resolving the factors affecting perceptions of both lecturers and students in using technology; hence, the literature reveals that knowing perceptions of users of the technology would give insights on its effective adoption (Theresa et al., Citation2021).

6. Contributions of the study

This study makes the following contributions to both theory and practice. As far as theoretical contributions of this study are concerned, the study extends the TOE framework as shown in Figure by explaining how the individual factors, for instance, the user perceptions influence the successful adoption of technology in mandatory environments such as online assessment during COVID-19; in so doing, demonstrating that the adoption of technology is not only underpinned by technology, organisation, and environmental factors but individual factors, too. The model captures the key factors that affect the adoption and use of online assessment in Polytechnics. Most previous studies exclusively focused on adoption challenges and are likely to miss out on the factors that enable the adoption of online assessment since challenges only reveal constraining mechanisms. Also, questions on the adoption of online assessment have typically been overshadowed by a focus on the acceptance of learning management systems in general. In addition, previous research tends to study online adoption factors in isolation. Therefore, by investigating them in an integrated approach, the study provides a unified view of constraining and enabling mechanisms in the adoption and use of online assessment by Polytechnics and other tertiary education institutions. Besides, the study responds to the call for further research by Butler-henderson and Crawford (Citation2020) on the need for adding to the literature on factors to the adoption of online assessment practice.

In terms of practical contributions, the findings will enlighten the administration in Polytechnics so that they pay attention to the key factors that influence the successful adoption of the online assessment. This will ensure that the pre-requisites that are required to support the adoption and usage of online assessment are in place. The extended TOE framework thus suggests that administration in Polytechnics should identify and address the challenges that construct negative perceptions of online assessment of the users. Furthermore, the extended TOE framework can be used as a valuable point of reference for scaling up the adoption and use of online assessment in Polytechnics and other tertiary education institutions.

7. Conclusion and recommendations

Online assessment in tertiary education institutions has been in practice for more than two decades (Orcid & Received, Citation2019; Swaffield, Citation2011; Tuah & Naing, Citation2021; Yong et al., Citation2021). Globally, “most of the academic institutions … have adopted some forms of electronic [assessment] many years ago as a supportive and efficient tool to their face-to-face classes and as flexible method to submit students assignments and conducts exams” (Shawaqfeh et al., Citation2020, p. 1). Nevertheless, online assessment in tertiary education has increased rapidly during the past two years due to its inevitable benefits in critical situations such as COVID-19. The COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated the move from physical, face-to-face assessment to online, copiously remote assessment. Thus, this study concludes that online assessment is no longer a choice for tertiary education institutions since COVID-19 has presented a mandatory environment for its adoption.

However, not all tertiary education institutions have successfully adopted this assessment practice. Using the extended TOE framework, the study investigated the factors affecting the adoption and use of online assessment in Polytechnics in Zimbabwe. The study concludes that the adoption and use of online assessment depend on technological factors (internet access, computing devices and ICT infrastructure), organisational factors (institutional support), environmental factors (academic integrity) and individual factors (digital skills and user perceptions). Online assessment cannot achieve the required intended assessment outcomes if lecturers and students do not have internet access, computing devices and the digital skills to access and navigate online assessment platforms. Lecturers and students need at least a smartphone and a stable internet connection to access online assessment platforms. Therefore, this study makes the following recommendations:

Firstly, Polytechnics need to consider taking initiatives to provide subsidized data bundles for both lecturers and students because most of them cannot afford to buy data bundles due to high costs.

Secondly, Polytechnics will have to provide a dedicated budget for supporting the deployment of requisite infrastructure for the adoption of an online assessment. These institutions should, therefore, come up with a budget and source for funds or a loaner to facilitate the procurement of computing devices for lecturers and students.

Thirdly, lecturers and students in Polytechnics should receive adequate training on the administration and use of online assessment platforms to overcome skills gaps among those who can or cannot effectively use online assessment tools. Eventually, this will construct positive perceptions on the adoption and usage of an online assessment.

Lastly, future research should perform a confirmatory factor analysis to determine the strength of the factors presented in Figure and develop an instrument for technology adoption framework for online assessment in Polytechnics.

Disclosure statement

No funding was received for conducting this study.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Gilbert Mahlangu

Gilbert Mahlangu is a holder of a Doctor of Information and Communication Technology from Cape Peninsula University of Technology (CPUT), South Africa. He is currently a Lecturer in the Department of Information and Marketing Sciences at the Midlands State University, Zimbabwe. He teaches Informatics and Business modules. These include but are not limited to, Data structures and Algorithms, Research in Data science and Informatics; Strategic Information Management and E-business, Strategy, and Innovation Management; Innovation and design thinking, Advanced Project Management and Applied Research Methods. His research interests are Digital inclusion; Digital transformation; Innovation and design thinking and Cyber offender behaviour. He participates in policy development for ICT in Agriculture and different presentations supporting ICTs at the university and national levels.

Lucia Makwasha

Lucia Makwasha is a lecturer at Harare Polytechnic. A holder of Master of Commerce in Information Systems Management with the Midlands State University in Zimbabwe and a Bachelor of Technology in Information Technology with Harare Institute of Technology in Zimbabwe. My research interests are in education in higher institutions, e-learning, Digital inclusion, and cyber security.

References

- Adanir, G. A., Ismailova, R., Omuraliev, A., & Muhametjanova, G. (2020). Learners’ perceptions of online exams: A comparative study in Turkey and Kyrgyzstan. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 21(3), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v21i3.4679

- Adarkwah, M. A. (2021). “ I ’ m not against online teaching, but what about us? ”: ICT in Ghana post Covid-19. Education and Information Technologies. 2(2), 1665–1685. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-020-10331-z

- Ahmed, K., & Mesonovich, M. (2019). Learning Management Systems and Student Performance. Int. J. Sustain. Energy. 7(1), 582–591. https://doi.org/10.20533/ijels.2046.4568.2019.0073

- Ajzen, I. (1991). Theory of Planned Behaviour. Organisational Behaviour and Human Decision Processes, 50(1), 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1108/JARHE-06-2018-0105

- Ali, L., Abidal, N., Hmoud, H., & Dmour, A. (2021). The Shift to Online Assessment Due to COVID-19: An Empirical Study of University Students, Behaviour and Performance, in the Region of UAE. International Journal of Information and Education Technology. 11(5). https://doi.org/10.18178/ijiet.2021.11.5.1515

- Alruwais, N., Wills, G., & Wald, M. (2018). Advantages and Challenges of Using e-Assessment. International Journal of Information and Education Technology. 8(1), 34–37. https://doi.org/10.18178/ijiet.2018.8.1.1008

- Alturki, U. (2021). Application of Learning Management System (LMS) during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Sustainable Acceptance Model of the Expansion Technology Approach. Sustainability.;13(19):10991. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131910991

- Ana, P., & Bukie, P. T. (2013). DESIGN AND IMPLEMENTATION OF ONLINE ADMINISTRATION SYSTEM FOR UNIVERSITIES EXAMINATION. Global Journal of Mathematical Sciences. 12(1), 39–51. https://doi.org/10.14704/WEB/V18I1/WEB18098

- Ansong, E., Lovia Boateng, S., & Boateng, R. (2017). Determinants of E-Learning Adoption in Universities. Journal of Educational Technology Systems, 46(1), 30–60. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047239516671520

- Awa Ojiabo, H. O. (2015). Integrating TAM, TPB and TOE frameworks and expanding their characteristic constructs for e-commerce adoption by SMEs. Journal of Science & Technology Policy Management, 6(1), 76–94. https://doi.org/10.30935/ejimed/8283

- Awa, H. O., Ukoha, O., & Emecheta, B. C. (2016). Using T-O-E theoretical framework to study the adoption of ERP solution. Cogent Business and Management, 3, 1. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2016.1196571

- Bariu, T. N. (2020). Status of ICT Infrastructure Used in Teaching and Learning in Secondary Schools in Meru County, Kenya. European Journal of Interactive Multimedia and Education. 1(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.30935/ejimed/8283

- Bashitialshaaer, R., Alhendawi, M., & Avery, H. (2021). Obstacles to Applying Electronic Exams amidst the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Exploratory Study in the Palestinian Universities in Gaza. Information. 12(6):256. https://doi.org/10.3390/info12060256

- Brooks, J., Mccluskey, S., Turley, E., & King, N. (2015). The utility of Template Analysis in qualitative psychology research. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 12(2):1–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2014.955224

- Butler-Henderson, K., & Crawford, J. (2020). Since January 2020 Elsevier has created a COVID-19 resource centre with free information in English and Mandarin on the novel coronavirus COVID-19. Agricultural Systems.

- Cavus, N., & Mohammed, Y. B. (2021). Determinants of Learning Management Systems during COVID-19 Pandemic for Sustainable Education. Sustainability;13(9):1–23. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13095189

- Chakraborty, P., Arora, A., & Gupta, M. S. (2021). Opinion of students on online education during the COVID-19 pandemic. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies, 2020, 357–365. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbe2.240

- Chandra, A. (2021). Analysis of factor ’ s in fl uencing the adoption of e-teaching methodology of learning by students: An empirical study amidst the present pandemic crisis. Asian Journal of Economics and Banking. 5(1), 15–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/AJEB-12-2020-0112

- Chatterjee, S., Rana, N. P., Dwivedi, Y. K., & Baabdullah, A. M. (2021). Understanding AI adoption in manufacturing and production firms using an integrated TAM-TOE model. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 170(2020), 120880. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2021.120880

- Dann, R. (2014). Assessment as learning: Blurring the boundaries of assessment and learning for theory, policy and practice. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy and Practice, 21(2), 149–166. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969594X.2014.898128

- Das, S., Lakshmaiah, K., Foundation, E., & Acharjya, B. (2022). Adoption of E-Learning During the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Web-Based Learning and Teaching Technologies. 17(2), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.4018/IJWLTT.20220301.oa4

- Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly, 13(3)319–340. https://doi.org/10.2307/249008

- Elsalem, L., Al-azzam, N., Jum, A. A., & Obeidat, N. (2021). Remote E-exams during Covid-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study of students ’ preferences and academic dishonesty in faculties of medical sciences. Annals of Medicine and Surgery, 62(January), 326–333. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amsu.2021.01.054

- Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1976). Misconceptions about the Fishbein model: Reflections on a study by Songer-Nocks. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 12(6), 579–584. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-1031(76)90038-X

- Gamage, K. A. A. (2021). Undergraduate Students’ Device Preferences in the Transition to Online Learning. Social Sciences, 10(8), 2–15. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10080288

- Ghanbari, N. (2021). The practice of online assessment in an EFL context amidst COVID-19 pandemic: Views from teachers. Language Testing in Asia. 11(4):1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40468-021-00143-4

- Grönlund, A., Samuelsson, J., Samuelsson, J., Samuelsson, J., & Samuelsson, J. (2021). When documentation becomes feedback: Tensions in feedback activity in Learning Management Systems feedback activity in Learning Management Systems. Education Inquiry, 00(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/20004508.2021.1980973

- Guangul, F. M. (2020). Challenges of remote assessment in higher education in the context of COVID-19: A case study of Middle East College. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability. 32:519–535. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11092-020-09340-w

- Haus, G., Pasquinelli, Y. B., Scaccia, D., & Scarabottolo, N. (2020). ONLINE WRITTEN EXAMS DURING COVID-19 CRISIS. International Association for Development of the Information Society, 19(2), 79–86. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED621634

- Holden, O. L., Norris, M. E., & Kuhlmeier, V. A. (2021). Academic Integrity in Online Assessment: A Research Review. 6. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2021.639814

- Huda, S. S. M., & Siddiq, T. (2020). E-Assessment in Higher Education: Students’ Perspective. International Journal of Education and Development Using Information and Communication Technology (IJEDICT), 16(2), 250–258. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED621634

- Hughes, S. (2019). Demystifying Theoretical and Conceptual Frameworks: A Guide for Students and Advisors of Educational Research. Journal of Social Sciences, 58(1–3), 24–35. https://doi.org/10.31901/24566756.2019/58.1-3.2188

- Iskandar, N., Ganesan, N., Shafiqaheleena, N., & Maulana, A. (2021). Students ’ Perception Towards the Usage of Online Assessment in University Putra Malaysia Amidst COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of Research in Humanities and Social Science. 9(2), 9–16. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1268772

- Kant, N., Prasad, K. D., & Anjali, K. (2021). Selecting an appropriate learning management system in open and distance learning: A strategic approach. Asian Association of Open Universities Journal. 16(1), 79–97. https://doi.org/10.1108/AAOUJ-09-2020-0075

- Kaushik, M. K., & Verma, D. (2020). Determinants of digital learning acceptance behavior: A systematic review of applied theories and implications for higher education. Journal of Applied Research in Higher Education, 12(4), 659–672. https://doi.org/10.1108/JARHE-06-2018-0105

- Lee, I., Mak, P., & Yuan, R. E. (2019). Assessment as learning in primary writing classrooms: An exploratory study. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 62(April), 72–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2019.04.012

- Masue, O. S. (2020). Applicability of E-learning in Higher Learning Institutions in Tanzania Willy A. Innocent Mbeya University of Science and Technology, Tanzania, 16(2), 242–249. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1268804

- Mate, K., & Weidenhofer, J. (2022). Considerations and strategies for effective online assessment with a focus on the biomedical sciences. Faseb Bioadvances, 2021, 9–21. https://doi.org/10.1096/fba.2021-00075

- Mensah, I. K., Zeng, G., Luo, C., Lu, M., & Xiao, Z. W. (2022). Exploring the E-Learning Adoption Intentions of College Students Amidst the COVID-19 Epidemic Outbreak in China. SAGE Open, 12, 2. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440221086629

- Mohamed, M., Id, Z., Hamed, M. S., & Bolbol, S. A. (2021). The experiences, challenges, and acceptance of e-learning as a tool for teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic among university medical staff. PloS one;16(3):e0248758. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0248758

- Muzaffar, A. W., Tahir, M., Member, S., Anwar, M. W., Chaudry, Q., Mir, S. R., & Rasheed, Y. (2021). A Systematic Review of Online Exams Solutions in E-Learning: Techniques, Tools, and Global Adoption. IEEE Access. 32689–32712. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3060192

- Na, S., Heo, S., Han, S., Shin, Y., & Roh, Y. (2022). Acceptance Model of Artificial Intelligence (AI)-Based Technologies in Construction Firms: Applying the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) in Combination with the Technology–Organisation–Environment (TOE) Framework. Buildings, 12, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings12020090

- Ngqondi, T., Blessings, P., & Mauwa, H. (2021). Social Sciences & Humanities Open A secure online exams conceptual framework for South African universities. Social Sciences & Humanities Open, 3(1), 100132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssaho.2021.100132

- Nguyen, T. H., Le, X. C., & Vu, T. H. L. (2022). An Extended Technology-Organization-Environment (TOE) Framework for Online Retailing Utilization in Digital Transformation: Empirical Evidence from Vietnam. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 8, 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc8040200

- Pedro, N. S. (2020). Institutional Support for Online Teaching in Quality Assurance Frameworks. Online Learning Journal, 24(3), 50–66. http://dx.doi.org/10.24059/olj.v24i3.2309

- Permadi, I., & Fathussyaadah, E. (2020). Technology, organization, and environment factors in the adoption of online learning. Journal of Management and Sustainability, 7(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.5539/jms.v4n1p96

- Qin, X., Shi, Y., Lyu, K., & Mo, Y. (2020). Using a tam-toe model to explore factors of building information modelling (Bim) adoption in the construction industry. Journal of Civil Engineering and Management, 26(3), 259–277. https://doi.org/10.3846/jcem.2020.12176

- Rayan, F., Ahmed, A., Ahmed, T. E., Saeed, R. A., Alhumyani, H., Abdel-khalek, S., & Abu-zinadah, H. (2021). Results in Physics Analysis and challenges of robust E-exams performance under COVID-19. Results in Physics, 23, 103987. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rinp.2021.103987

- Reedy, A., Pfitzner, D., Rook, L., & Ellis, L. (2021). Responding to the COVID-19 emergency: Student and academic staff perceptions of academic integrity in the transition to online exams at three Australian universities. International Journal for Educational Integrity. 9(1), 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40979-021-00075-9

- Rogers, E. M. (2003). Elements of diffusion. Diffusion of Innovations, 5, 1–38. https://teddykw2.files.wordpress.com/2012/07/everett-m-rogers-diffusion-of-innovations.pdf

- Sage, D., Dainty, A., & Brookes, N. (2014). A critical argument in favor of theoretical pluralism: Project failure and the many and varied limitations of project management. International Journal of Project Management, 32(4), 544–555. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2013.08.005

- Schellekens, L. H., Bok, H. G. J., de Jong, L. H., van der Schaaf, M. F., Kremer, W. D. J., & van der Vleuten, C. P. M. (2021). A scoping review on the notions of Assessment as Learning (AaL), Assessment for Learning (AfL), and Assessment of Learning (AoL). Studies in Educational Evaluation, 71(February), 101094. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2021.101094

- Scherer, R., Siddiq, F., & Tondeur, J. (2019). The technology acceptance model (TAM): A meta-analytic structural equation modeling approach to explaining teachers’ adoption of digital technology in education. Computers and Education, 128, 13–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2018.09.009

- Shakeel, A., Shazli, T., Ahmad, N., & Ali, N. (2021). Challenges of unrestricted assignment-based examinations (ABE) and restricted open-book examinations (OBE) during COVID-19 pandemic in India: An experimental comparison. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies, 3(5):1050–1066. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbe2.290

- Shawaqfeh, M. S., Al, A. M., Al-azayzih, A., Alkatheri, A. A., Qandil, A. M., Obaidat, A. A., Al, H. S., & Muflih, S. M. (2020). Pharmacy Students Perceptions of Their Distance Online Learning Experience During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Survey Study. Journal of medical education and curricular development. https://doi.org/10.1177/2382120520963039

- Shen, J., Cheng, K., Bieber, M., & Hiltz, S. R. (2004). Traditional In-class Examination vs. Collaborative Online Examination in Asynchronous Learning Networks: Field Evaluation Results. AMCIS, 18(4), 1–11. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0969594X.2011.582838

- Shraim, K. (2019). Online examination practices in higher education institutions: learners’ perspective. Turkish Online Journal of Distance Education, 20(4), 185–196. https://doi.org/10.17718/tojde.640588

- Shraim, K. Y. (2019). Online Examination Practices in Higher Education Institutions: Learners ’ ONLINE EXAMINATION PRACTICES IN HIGHER EDUCATION INSTITUTIONS: LEARNERS ’ PERSPECTIVES. Turkish Online Journal of Distance Education. https://doi.org/10.17718/tojde.640588

- Stanciu, C., Coman, C., Gabriel, T., & Bularca, M. C. (2020). Online Teaching and Learning in Higher Education during the Coronavirus Pandemic: Students ’ Perspective. Sustainability. 12(24):10367. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410367

- Steindal, S. A., Ohnstad, M. O., Landfald, Ø. F., Solberg, M. T., & Sørensen, A. L. (2021). Postgraduate Students ’ Experience of Using a Learning Management System to Support Their Learning: A Qualitative Descriptive Study. SAGE Open Nursing. https://doi.org/10.1177/23779608211054817

- Swaffield, S. (2011). Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice Getting to the heart of authentic Assessment for Learning. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 18(4), 433–449. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969594X.2011.582838

- Tan, P. J. B. (2013). Applying the UTAUT to understand factors affecting the use of English e-learning websites in Taiwan. SAGE Open, 3, 4. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244013503837

- Theresa, M., Valdez, C. C., & Maderal, L. D. (2021). An Analysis of Students ’ Perception of Online Assessments and its Relation to Motivation Towards Mathematics Learning. Electronic Journal of e-Learning, 19(5), 416–431. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969594X.2011.582838

- Tornatzky, L. G., & Fleischer, M. (1990). Innovation As a Process. Lexington Books, 23, 1. https://doi.org/10.7251/emc2201237t

- Tshiningayamwe, S. (2020). The Shifts to Online Learning: Assumptions, Implications and Possibilities for Quality Education in Teacher Education. Southern African Journal of Environmental Education. 36(March), 16–33. https://doi.org/10.4314/sajee.v36i3.16

- Tuah, N. A. A., & Naing, L. (2021). Is Online Assessment in Higher Education Institutions during COVID-19 Pandemic Reliable? Siriraj Medical Journal, 73(1), 61–68. https://doi.org/10.33192/SMJ.2021.09

- Ullah, M. N., & Biswas, B. (2022). Assessing Institutional Support to Online Education at Tertiary Level in Bangladesh Coping with COVID-19 Pandemic: An Empirical Study. Journal of Digital Educational Technology, 2(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.21601/jdet/11735

- Ullah, A., Xiao, H., & Barker, T. (2019). A study into the usability and security implications of text and image based challenge questions in the context of online examination. Educ Inf Technol, 24(1), 13–39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-018-9758-7

- Yong, C., Tan, A., Mon, K., Swe, M., & Poulsaeman, V. (2021). Online examination: a feasible alternative during COVID-19 lockdown. Quality Assurance in Education, 29(4), 550–557. https://doi.org/10.1108/QAE-09-2020-0112