Abstract

In most of the countries that signed the Salamanca Statement, there seems to be a gap between policy formulations and realisations of inclusive education. Much of this gap has been blamed on the deficit or narrow view to inclusive education that focuses only on the education for disabled students, against the broader view of inclusive education, which deals with all students in danger of marginalisation. In the deficit/narrow view, mathematically gifted students are neglected, and this is detrimental to national efforts towards producing the much-needed 21st century skills. The question at stake then is the origin of this narrow view—is it how inclusive education is conceptualised in the policy framework or is it more about the discretion of the actors in the implementation context? This paper analysed 3 international, 3 national inclusive policy documents and surveyed 51 foundation-phase teachers’ perceptions and practices with the aim of understanding the extent to which gifted students were accommodated in those policy documents and practices. Vygostky’s defectology theory was used as a lens to judge whether the dominant view to inclusive education was narrow or broad. Results show that although both the narrow and broad views are mentioned, the dominant view in both policy and practice was the narrow view to inclusive education. Similar South African studies have shown how an egalitarian and equalising approach to education would leave the gifted learner with minimal attention. Consistent with previous studies, our recommendation is that respect for difference can only be cultivated if those responsible for enacting educational practices are supported by consistent and coherent policy messages, which value skills development by challenging the deficit view to inclusive education.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

In many less developed countries, expanding access to education has remained a dominant driver for educational policy makers, yet skills development has remained elusive. One of the reasons why many countries find themselves in such a crisis is because fewer stakeholders have ever approached education from the economics of gifted education and the investment in human capital perspective. From this perspective, it has been shown that the returns to education are not homogenous but rather heterogeneous across the population suggesting that different student abilities impact the economy differently. Following this view, it has been suggested that the efficient allocation of schooling investments should therefore be guided by the rate of return on investment and in education this depends on individual traits, such as ability and motivation. Such studies have shown how gifted students provide an exceptional rate of return for the financial investment made in them by the state.

1. Introduction

When it comes to the field of inclusive education, one of the most important international policy initiatives came through UNESCO’s Salamanca Statement (UNESCO Citation1994) and for that reason it is an almost obligatory reference point in both empirical and theoretical research on inclusion. The statement was signed by 92 nations at the time, and through it the ideal of inclusive education was not only introduced as a political goal to strive for but in fact became a global policy vision. In order to achieve this vision, it was mandatory for all member countries to reform their national policies and legislation, in order to design strategies that would result in effective inclusive education systems. Consequently, many nations around the globe that have an understanding of the human rights and social justice discourses underpinning inclusive education, have found it imperative to adapt the Salamanca Statement and Framework for Action to their local contexts, and have released many policy documents, which have been implemented or are in the process of implementation in several nations including South Africa. Despite the perception that inclusive education reflects the ideal values and principles that counteract the ways in which educational systems reproduce and perpetuate social inequalities; researchers warn that inclusive policies are like a double-edged sword in that they can reproduce inequality in their desire and ambition for equality. This follows empirical evidence that has shown a significant distance between these inclusive policy ideals and their effective fulfilment within the member countries. Critics point to a potential risk of inclusive education in that it has only a rhetorical space in educational reforms due to the diverse contexts and prerequisites on the ground. Against this background it therefore becomes important to study comparatively whether, and how, such ideals are expressed in different international as well as national education policies, and how they are implemented in practice.

1.1. Statement of the problem

Admittedly, many studies have been done on the challenges of implementing inclusive education in different contexts including South Africa. However, the concern in this paper is that few if any of the studies so far have analysed the inclusive policy content with the aim of understanding the extent to which mathematically gifted students are accommodated therein. In South Africa, a National Strategy for Mathematics, Sciences & Technology Education (NSMSTE) was introduced in 2001 as a priority and permanent goal of the country’s effort to harness a perennial problem of poor performance especially in mathematics. The vision of the strategy was very clear in that an adequate supply of Grade 12 graduates with mathematical sciences would be better assured by focusing on learners with “exceptional” potential in mathematics who would be identified and nurtured in a hundred dedicated schools rather than through a dilution of effort across the whole schooling system. Since then, the documents related to the NSMSTE have been littered with phrases that make it unambiguously clear that the focus was on gifted learners in mathematical sciences. Given that this is a permanent strategy, what started as the hundred dedicated school project has not only grown in number to the current 1000 schools but has also changed names from dedicated schools, to Dinaledi (which means something beautiful or stars in one of the local languages) Schools, to the most recent name—Mathematics, Science & Technology (MST) schools. In the last two decades of its existence, the NSMSTE has been evaluated and revised periodically and in the latest intergrated NSMSTE 2019–2030, the minister of basic education made a candid admission that government had to do more in terms of providing “exceptional learners” with greater access to dedicated/focus schools. Similarly, in the Department of Basic Education 2018/2019 annual report, the minister also lamented that when talented children do not participate in school or drop out before achieving their full potential, this is a grossly inefficient use of the country’s human capital (DBE. Citation2019:16). The study from which this paper draws data was driven by recommendations made from such reports wherein the gifted learner is mentioned as one category of exceptionality that should become the central part of the organization, planning and teaching at inclusive schools (DOE, Citation2013). The concern for gifted students is justifiable following Rimm et al. (Citation2018) who stated that unrecognised and unsupported talent is wasted talent. In South Africa, gifted programs were seen as the domain of the rich and upper class; hence, post 1994, gifted education programs were dismantled unleashing an additional equity issue, especially for those gifted students who come from poorer socio-economic backgrounds. This paper claims that by dismantling schools for the gifted on the assumption that it was elitist and therefore exclusionary, South African “inclusive education system” did not eradicate exclusion of the children from poor communities, instead it only changed the form of exclusion from overt to covert because denying the needs for gifted students is most damaging to the prospects of poorer or minority children. It is against such a background that this paper was conceptualised.

1.2. Purpose statement

According to Stubbs (Citation2008), although there is no blueprint for “doing” inclusive education, the following three key ingredients can help an inclusive education programme to be realistic, appropriate, sustainable, effective, and relevant to the culture and context in the long term:

‘The skeleton’—The principles of inclusion that are set out in the international declarations can be used as a foundation on which to interpret and adapt to the context of individual countries.

‘The flesh’—Inclusive education is not a blueprint. Even the Salamanca Statement itself is clear in that the Framework is intended as an overall guide to planning action in special needs education. Therefore, to be effective it must be complemented by national, regional, and local plans of action.

‘The life-blood’. Although the intensions of inclusive education might have been clear on paper, however, the success of inclusive education seems to depend significantly on the active participation of teachers. Therefore, positive perceptions of teachers are deemed to be necessary and indeed an important starting point for the development of a suitable inclusive school environment.

1.3. Research questions

Consistent with these three key ingredients of skeleton, the flesh and the life-blood, three research questions are being raised in this paper as follows:

To what extent do external/global inclusive documents, to which South Africa appended its signature, support and accommodate gifted learners?

How do internal inclusive documents in South Africa support and accommodate gifted learners?

To what extent do educators implement inclusive education with gifted learners in mind, within the Umlazi district schools in Kwazulu-Natal?

1.4. Importance of the study

Inclusive education is a policy phenomenon with international, national, regional, and local implications. So, according to Hardy and Woodcock (Citation2015), inclusive practices can only be cultivated in educational systems if those responsible for enacting educational practices are supported by consistent and coherent policy messages. Lack of coherence or consistency weakens policy implementation and if there is coherence in inclusive policy messages then the different parts and levels would support each other thereby improving the chances of achieving the ambitious objectives of inclusive education. Similarly, Brunsson (Citation2000) emphasises that the absence of uncertainty and conflicts associated with ambitious activities and practices are important conditions for success. So, the importance of this study can be seen in that it was premised on the view that in order to fully understand the challenges of inclusion in South Africa, it is imperative to understand the extent to which the various policy documents both globally and locally are connected and consistent with relation to inclusion.

The second importance of the study can be seen in its focus on inclusion with specific reference to gifted students. Although education is meant to support the development of a diversity of talents and abilities in the learners, it is not true that equal importance can be placed on all such talents and abilities as society attempts to meet the challenges of the knowledge-based economy [KBE]. Within these debates about skills needed for the 21st century KBE, empirical evidence has shown that the positive impact on a country’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) can be isolated mainly to Science, Technology, Engineering & Mathematics [STEM] related achievements as opposed to achievements outside STEM; suggesting that STEM-related achievements are the main drivers of national affluence in the KBE (Tanenbaum, Citation2016). For this reason, ensuring an adequate supply of STEM skills is at the heart of many governments’ strategies for innovation and productivity. Some researchers have even gone further to try and establish whether all STEM disciplines have equal importance in the KBE and conclusions have been unanimous that all STEM disciplines require an understanding of mathematics suggesting that “Mathematics is the bedrock of science while science is the necessity for technological and industrial development” (Betiku, Citation1999:49). Given its bedrock status, mathematics has been described as the subject that drives the KBE; hence, it should be an important part of any efforts at modern-day technological innovation and development. Within these debates, the current view is that the progress of human civilization is based on scientific, technological, educational, moral, political, and commercial achievements of the minds of its most talented individuals (Daniels, Citation2012). In South Africa Xolo (Citation2007) also made a strong plea that it is not the gold in the mines, but the talents and the minds of our mathematically gifted youth, which will make our country an effective participant in the global playing field. From this perspective, the mathematically gifted have been described as the world’s ultimate capital asset due to their unique potential to become tomorrow’s scientists, inventors, entrepreneurs, engineers, and civic leaders in a knowledge-based economy. In this paper, it is argued that South Africa’s future depends crucially on how she educates the next generation of people gifted in the mathematical sciences.

1.5. Theoretical framework

This section starts with an outline of the structure and an explanation of the framework that was used for analysis. An analysis of the relevant research databases from 2012 concluded that the dominant use of the term inclusion was in relation to the “narrow” approach focusing on special education and disability (Norwich, Citation2014). This narrow approach states that students with disabilities shall be entitled to full membership in regular classes together with children from the same neighbourhood in local schools. This is in conflict with the broader ideology of inclusive education contained in the UNESCO’s—Salamanca Statement in which the guiding principle that informs inclusivity is that schools should accommodate all children regardless of their physical, intellectual, social, emotional, linguistic, or other conditions (UNESCO Citation1994). This should include disabled and gifted children, street and working children, children from remote or nomadic populations, children from linguistic, ethnic, or cultural minorities and children from other disadvantaged or marginalised areas or groups (page 6). So, in line with the Salamanca Statement, the broad definition of inclusion concerns all students and marginalised groups, not only those with disabilities (Thomas, Citation2013). The idea is that education develops human capital for everyone and most of the international organisations that have shown interest in inclusive education have adopted this wide approach. Both of these (deficit/narrow and broad) conceptualizations of inclusive education are foundational to the arguments in this paper—hence there was need for a framework that would enable the organisation of ideas accordingly.

According to Vik and Somby (Citation2018) the approach in most countries towards children with disabilities has been heavily influenced by the Soviet science of “defectology”. Although the word defectology, may sound harsh to the readers’ ears, it is still the current Soviet term for the discipline which studies the handicapped, their development, teacher training and methods. Concurrent with his lifelong feelings of exclusion and related quest for acceptance, Vygotsky criticized the philosophical foundations of the education of individuals with disabilities, or with some other special condition, the forms of evaluation and referral for attendance in auxiliary schools, the methods, and contents of Special Education, launching his propositions—fundamental elements for a revolutionary Defectology, its principles and ends (Barroco, Citation2018). The uniqueness of Vygotsky’s approach lies in his conceptualisation of disability as a sociocultural developmental phenomenon. This is particularly important because social life in the first decades of the 21st century has presented challenges of all kinds, one of which concerns the problem of social exclusion which, according to Vygotsky’s theory, becomes a hindrance to the development of human psychic activity (Barroco, Citation2018). According to Vygotsky, the problem of non-development is not due to the type of disability and the degree of impairment caused, but to the limits that social classes impose on men (Vygotsky, Citation2004). In one of his studies, Vygotsky asked for the reasons of handicaps but did not search for biological ones. Instead, he found that these reasons were not primarily physical “defects” but socially determined handicaps. He contrasted it to what he sarcastically labelled as an “arithmetical concept of handicap” (Vygotsky, Citation1993, p. 30), that is, viewing a child with disability as the sum of his or her negative characteristics. Therefore, breaking away from the common assumption that disability is mainly biological in nature, Vygotsky’s insight was that the principal problem of a disability is not the sensory or neurological impairment itself but its social implications. Within the context of his paradigm of the social nature of disability, Vygotsky introduced the concepts of the primary disability and secondary disability and discussed the issue of their interaction. A primary disability is an organic impairment. A secondary disability refers to distortions of higher psychological functions due to social factors. Vygotsky (Citation1993) clearly differentiated the development of children with neurological (organically based) or severe sensory or physical impairment from those who were intact neurologically, physically, and sensorially but who had endured severe cultural deprivation and educational neglect. Using the unfortunate terminology of his time, Vygotsky called the first group defectives and the second group primitives who are retarded performers rather than retarded individuals. He argued that both groups may achieve similar results academically, on psychological tests or in the domain of adaptive behaviour and social skills, but the nature of their needs and the remedies to be used differ. This view to inclusive education sees the “problem” of disability as not something that is wrong with the child but rather something that is wrong with the organization of schools. This “inclusive” approach to special needs education argues that schools should be made sufficiently flexible to accommodate diversity, whether this stems from disability or any other source.

In terms of the defectology theory’s relevance to this paper, it can be argued that when the issue of inclusive education is raised, it is most often with regard to pupils who have one or more educational disadvantages or difficulties (defective). It is not so often that consideration is given to corresponding needs of children with different kinds of high ability or gifted students but who had endured severe cultural deprivation and educational neglect (primitives). This paper argues that gifted students fit very well into this group of child-primitives because when schools do not actively identify giftedness among young children, then those schools underserve these students who consequently underachieve in relation to their full potential. So, the argument is that if gifted children are denied educational opportunities due to some perceived advantage, then it is the lack of education, and not their differences that limit their opportunities. Consistent with Vygotsky’s notion of child-primitive, it can be further argued that gifted students’ learning disability emanates from endured severe cultural deprivation and educational neglect in the current inclusive practices. Vygotsky criticised mainstreaming as a “negative model of special education” because of its combination of lowered expectations, a watered-down curriculum, and social isolation (isolation from students who think alike). Gifted children experience all these negatives in their current inclusive classrooms. Vygotsky suggested that in the future, science would be able to create a disability-specific profile of the discrepancy between the “natural” and “social” courses of development as the most important characteristic in the psychological growth of the child. Compensatory strategies should then be built after considering the child’s individuality, personal experiences, and what Vygotsky called “the social situation of development”.

Vygotsky worked several years to develop his vision for the future model of special education that can be called, using his own words, “integration based on positive differentiation” (Vygotsky, Citation1995, pp. 114, 167). He implored his readers to consider that the education of all children, regardless of the norms they follow, should contribute to the development of a socially accepted adult capable of “social labour, not in degrading, philanthropic, invalid-oriented forms … but in forms that correspond to the true essence of labour” (p. 108–109). He believed that few children, much less those of evolutionary difference, reach their potential as most of them were stuck at the lowest end of their social potential. In contrast, he believed, schools of defectology needed to be spoken about as schools of exceptional learning whose goal it was to promote, with attention to developmental issues, integration of extranormal children into the current social life, such that upon their graduation they exhibited the higher mental functions that enabled full participation in this full social stream, even if they navigated its waters with unconventional psychological tools. Although the language and ideology of the deficit remain at large in spite of efforts to attend more respectfully to the issues of difference that concerned Vygotsky, Vik and Somby (Citation2018) posit that the conception and rhetoric Vygotsky questioned in his works on Defectology are still relevant today in the discussions about inclusive education. Nowadays, to rely on Vygotskian foundations means to seek having an inclusive education that confronts every barrier “that limits or prevents the person’s social participation, as well as enjoyment, fruition, and exercise of their rights to accessibility, freedom of movement and expression, communication, access to information, understanding … ” (Barroco, Citation2018). It is against this background that Vigostky’s defectology theory was considered relevant to this paper.

2. Methods

2.1. Research design

This study employed a mixed-method design in which both primary and secondary data were collected and both quantitative and qualitative data were collected. In order to answer the first and second research questions, document analysis [secondary data] was used where both international and local policy documents on inclusive education were analysed. This was followed by a survey questionnaire [primary data] where participants indicated their perceptions about inclusive education with special focus on gifted students. The study ended up with some classroom observations where Foundation Phase Teachers’ implementation of inclusive education was analysed again with a specific focus on gifted students.

2.2. Data collection and analysis

In collecting data to answer the first two research questions, the study was interested in analysing documents looking for words related to disability or giftedness. The study was particularly interested in distinguishing between the use of these words in the “narrow” view and the “broader” view to inclusive education with the aim of determining the predominant approach. There is some concern that gifted students are at risk of not developing to their full potential in the mixed ability classroom with a narrow view to inclusive education. In such classrooms, the reality is that when teachers differentiate, they tend to focus their efforts on the struggling learners. So according to Arduin (Citation2015) a correlation exists between the ideology predominant in a society and its approach to disability and inclusive education. When researchers want to ascertain the predominant view in one or more texts, it has been acknowledged that word counts are a preferred measure (Krippendorf Citation1980). Word repetitions (WR), key-indigenous terms (KIT), and key-words-in-contexts (KWIC) all draw on a simple observation—if you want to understand what people are predominantly talking about, look at the words they use. We therefore looked for a software that would enable us to do such word-counts.

WordStat is one such flexible and easy-to-use text analysis software—that can be used by anyone who needs to quickly extract and analyse information from large amounts of documents. Keyword-in-context (KWIC) is a useful feature in WordStat that allows one to see the occurrence of either a specific word or all words related to a category in an actual text arranged in a table format. For example, prior to analysis the researchers had identified the words “potential and capable” as being related to the “broader” view of inclusive education but when their use was analysed in context through WordStat, it was found out that these words were actually being used in relation to disabled children (narrow view) i.e. … youth or children with disabilities should be educated to the best of their potential or … and infusing greater optimism and imagination about the capabilities of persons with disabilities. From this evaluation, it was clear that WordStat was an ideal software that could perform the required tasks in this study.

A questionnaire was used to collect teacher perceptions about inclusive education and how their practice accommodates/neglects gifted students, i.e.,, the broader and narrow approaches, respectively. A lesson observation schedule was also developed to understand teacher practices regarding this broader and narrow approaches to inclusive education. The main argument was that gifted children get neglected in an environment that takes a “narrow” approach to inclusive education.

2.3. Sampling

In this study, judgemental sampling was employed where the researchers focused on documents that have continued to guide the agenda of international and national inclusive policies. From the global inclusive education documents, the Salamanca Statement, the Dakar Framework for Action & the Human Rights-Based Approach to Education for All (HRBATEFA) were sampled. From the national/local South African inclusive documents, the White Paper 6, the Curriculum & Assessment Policy Statement (CAPS) as well as the Policy on Screening, Identification and Support (PSIAS) were sampled. These documents constitute a foundational framework for the standardisation of the procedures to identify, assess and provide programmes for all learners who require additional support to enhance their participation and inclusion in schools. In terms of participating teachers, purposive sampling was employed because the researchers were particularly interested in Foundation Phase teachers in one district of KwaZulu Natal. This choice also follows Gagne’s recommendation to delay structured enrichment activities for gifted students until at least Grades 3 or 4.

2.4. Validity and reliability

The beauty about WordStat software when doing data counts is that it has a built-in mechanism called KWIC for validating any claims that the researcher might want to make. For example, when the frequency of the word “potential” was checked in one of the documents, it was clear (see, Figure ) that the word was first used on page 24 of the document with 50 pages, it had a total frequency of 3 and was used in the context of children with disabilities. This is easily verifiable by a second researcher thereby ensuring the validity and reliability of our data.

Regarding the other data collection instruments, i.e. questionnaire and class observation schedules, content validity was ensured from literature, which suggests the characteristics of ideal inclusive practices (Haug, Citation2017) and reliability was ensured through pilot testing.

3. Results

In the first research question, the reserachers were interested in the extent to which external/global inclusive documents (Salamanca Statement, Dakar Framework for Action & the Human Rights-Based Approach to Education for All) which influence South African inclusive education, support, and accommodate gifted learners.

Table shows the results from analysing these international documents. For example, the words disabled/disability/disabilities were used 59 times in the Salamanca Statement, 21 times in the Dakar Framework for Action and 66 times in the Human Rights-Based Approach to Education for All, giving a total of 146 times in all the three documents. In both the Salamanca Statement and the Dakar Framework for Action those words were used 100% with reference to the narrow view of inclusive education, i.e., referring to disabled learners. In the Human Rights-Based Approach to Education for All, the same words were used 83% with reference to the narrow view and 1% with reference to the wider view of inclusive education. For example, on page 16, the HRBATEFA makes reference to a participatory approach stating that: …. Whenever possible, the views of girls and boys of different ages, in and out of school, with and without disabilities, and from different ethnic groups, geographic locations and socio-economic situations should be taken into account. In this instance the word “disabilities” was used with a wider view to inclusive education. In that same document the difference [100%—(83% + 1%)] suggests that 16% of the use of these words was outside the “narrow” or “wide” categorisation. For example, in the references section of the HRBATEFA document that word “disability” appears several times and such use would not fall into our categorisation of narrow and wide.

Table 1. Distribution of frequencies of words relating to disability in the various international documents (n = 260)

In the second research question, the researchers were interested in the extent to which internal/national inclusive documents, which influence South African inclusive education, support, and accommodate gifted learners. Table shows the results from analysing these national documents. For example, the words disabled, difficulties, special needs and impairments were used 219 times all with reference to the narrow view of inclusive education, i.e., referring to disabled learners. Only the word deficit was used 3 times in the wider/broader sense of inclusive education.

Table 2. Distribution of frequencies of words relating to disability in the various national documents (n = 222)

The results are clear in that the narrow view to inclusive education is prioritised. Even the Education White Paper 6 on Education and Training (1995) acknowledges the importance of providing an effective response to the unsatisfactory educational experiences of learners with special educational needs. In accepting this inclusive approach, the White Paper 6 argues that the learners who are most vulnerable to barriers to learning and exclusion in South Africa are those who have historically been termed “learners with special education needs,” i.e., learners with disabilities and impairments (p. 7). Consequently, in an inclusive education and training system, a wider spread of educational support services will be created in line with what learners with disabilities require (p. 15).

Consistent with the study’s approach, resarchers were also interested in analysing both the international and national documents in terms of how the words gifted, potential, capable, talent and clever had been used in context. Our initial thoughts were that such words would be consistent with the wider/broader view to inclusive education.

The results in Tables were surprising in two important ways. First, it is the low frequencies showing how rarely documents refer to such concepts. Secondly and contrary to initial assumptions, these words were also used mostly in the narrow sense of inclusive education. An interesting observation is that although the Salamanca Statement is cited as an almost obligatory reference point in both empirical and theoretical research on inclusion, it only makes reference to gifted children once and as an afterthought—because it says “including”. It also makes use of the words potential and capable exclusively with reference to disabled children.

Table 3. Distribution of frequencies of words relating to giftedness in international documents (n = 73)

Table 4. Distribution of frequencies of words relating to giftedness in the national documents (n = 11)

In the third and final research question, researchers were interested in understanding teacher perceptions and practices in terms of inclusive education. It can be argued that it does not suffice that the overall general policy focuses on inclusion if the schools’ organisation and teaching contradict this policy. Empirical evidence has shown that the behaviour of educators, their way of working, the theoretical background they follow, and their specific teaching practices are critical factors that can enhance or undermine the inclusive practices. Table shows the results on educators’ conceptualisation concerning inclusive education where 78.4% of educators agreed that they were aware of inclusive education; but when speaking about the practice, most of the teachers, 49.0% and 11.8% indicated that they were not sure and did not practise inclusive education.

Table 5. Educators Conceptualisation of inclusive education (n = 51)

Table interpreted the results according to accommodation of gifted learners in the inclusive classroom. The interest was on how educators nurtured and accommodated gifted learners in the classroom for all. This was also subdivided into five questions, whereby the study wanted to establish whether or not the educators had the knowledge and skills for identifying and supporting gifted learners and got training on how to work with these learners. A total of 80.3% of educators indicated that they knew about the learners who were mathematically gifted, 6% of them were not sure, while 13.7% did not know. A total of 84.3% of educators voiced that they did not receive training on how to teach gifted learners, while only 11.7% of educators agreed that they received the training and another 4% of them were not sure. In terms of identifying gifted learners, only 18,4% indicated that they know how to identify gifted learners, while 66,4% of educators unanimously denied that they are not sure about the identification of gifted learners. Consequently, 94.1% of teachers claimed higher education institutions should include content and methods on gifted education in their courses.

Table 6. Accommodation of gifted learners in the inclusive classrooms (n = 51)

Table covered teachers’ attitude towards gifted learners. The table was also subdivided into five statements whereby the aim was to establish whether or not the teachers understand the gifted learners and how they learn in their classes, the teachers’ attitudes were also interpreted. The results are presented below where 58% of educators did not see the importance of teaching gifted learners. But on the contrary, 96% of educators preferred to teach gifted learners because they are intelligent. A total of 70.5% of educators had a negative attitude towards gifted learners by describing gifted learners as if they were seeking attention by asking different and difficult questions. So, 50.9% of the educators used to give them too much of work or used them as their assistants, while 68.6% of the educators preferred gifted learners to be separated from the learners who were not gifted. All this information implies that the teachers were still far to accommodate these learners, and on the other side, gifted learners were neglected in the inclusive classrooms.

Table 7. Teachers attitudes towards gifted learners (n = 51)

In Table , the study was interested in teachers’ planning of their lessons. This was subdivided into six statements where the study wanted to establish whether or not teachers were including mathematically gifted learners in their lesson plans. The results show that 54.9% of the respondents planned their lessons without gifted learners in their minds, while 27.5% of educators said yes, they planned their lesson with gifted learners in their mind. In terms of deviating from the set curriculum to cater for the needs of gifted students, 54,5% said it clearly that they teach them at the same pace. That implies that the lesson plans were designed for the whole class as they said in their challenges that overcrowding was a problem, so all the learners were falling in one category of assessment.

Table 8. Teachers’ planning (n = 51)

4. Discussion

In the first research question, the study was interested in understanding the dominant view to inclusive education in the international policy framework as articulated in the Salamanca Statement, Dakar Framework for Action & the Human Rights-Based Approach to Education for All. The results clearly show that the dominant view to inclusive education judged by word-count and their use in context, is that of the narrow view, which is about how to organise and teach special education to students with disabilities. A similar analysis of relevant research databases from 2012 concluded that the dominant use of the term inclusion was in relation to special education and disability (Norwich, Citation2014). Although Magnusson (Citation2019) did not use word count to analyse the targeted documents, his results were similar in that judged by the interpretation of inclusion “visible” in the documents related to The Salamanca Statement, it is quite possible to interpret inclusion narrowly using these documents, i.e., as a matter of placing pupils with disabilities in regular schools and classrooms. Some researchers argue that this dominant view to inclusive education should not be surprising at all given that some aspects of inclusive education date back several hundred years. Inclusive education then was formulated with its roots firmly placed in special education, a connection maintains should be acknowledged. Kluppis (2014) argued that from a historical perspective the project of inclusive education, as coined in The Salamanca Statement, was a project distinct from Education for all.

The use of the terms “dominant narrow view” to us does not suggest absence of the “broader view” to inclusive education in the policy frameworks. It simply points to a lack of coherence in that special education has received too much attention within inclusive education at the expense of the broader view. Empirical evidence has shown that lack of coherence weakens the policy; hence, the expectation is that all levels of the education systems and their environments support and promote the intentions and practices of inclusive education from top international policy to national policy, to teacher-practices and student experiences. Given this dominant narrow view to inclusive education, the research literature presents several obvious explanations about implementation difficulties. Certain practices can be predicted because a correlation exists between the ideology predominant in a society and its approach to disability and inclusive education. With an increasing demand to differentiate due to diversity in inclusive classrooms, there is some concern that early misuses of differentiation can actually make the regular classroom a less challenging place for gifted children (Hertberg-Davis, Citation2009). Misunderstanding about differentiation from a narrow view, that it is about scaffolding for disabled or struggling learners, has resulted in critics arguing that the intellectual needs of gifted learners will not be met sufficiently in the mixed ability classroom. Reality is that teachers who take a “narrow view” to inclusive education will make few if any accommodations or differentiate for gifted learners in these mainstream classrooms. These findings suggest that gifted learners will not develop to their full potential in the current inclusive setup in South African schools.

Consistent with these findings, the partial progress made with respect to the EFA goals so far has revealed that a holistic vision and approach to the right to lifelong learning opportunities is essential for achieving inclusive and equitable societies. The narrow view to inclusive education identified in the documents that were analysed in this study implies a revised educational policy agenda, at the international, national, and local levels. Milne and Mhlolo (Citation2021) talked about loose and tight coupling citing the OECD’s (2014) concern that loosely coupled systems have a tougher time bringing about reform initiatives and are often typified by an endless parade of new and sometimes conflicting policies, without building the capacity to meet them. Similarly, Sayed and Jansen (Citation2001) explain that, while South African educational policies have been highly praised throughout the world owing to their dazzle, these policies are seldom brought to practice. In addition, Colebatch (Citation2002) perceives implementation as a process of transforming educational policy into practice and the achievement of the desired goal of any public intention is the hallmark of policy realisation. This means paying more attention and intricately linking equity and quality issues and comprehensively addressing the underlying causes of exclusion. A revised approach to educational policy also requires a close consideration of the impacts on socially disadvantaged groups such as gifted students; such prioritization must be solidly grounded on universal frameworks and embedded in a moral mandate, common to all educational provisions and aimed at attaining high performances.

Inclusive education: the way of the future was also the challenging topic discussed at the 48th session of the International Conference on Education (ICE), held in Geneva on 25–28 November 2008. The challenge was certainly accepted with determination and vigour by over 1,500 participants, including representatives from Ministries of Education, international organizations, non-governmental organizations, and civil society. An analysis done at this 48th Session of the UNESCO International Conference of Education, by the International Bureau of Education committee also arrived at similar findings (UNESCO Citation2009). The committee analysed the content of 129 messages from Minsters of Education across the globe (36 from developed countries, 86 from developing countries and 7 from countries in transition) in order to determine (i) what kinds of issues and/or topics related to inclusive education are considered as the most relevant by the Ministers; (ii) what priority groups affected by exclusion are mentioned in their messages; and (iii) what key measures and action areas are evoked in conjunction with inclusive education.

In terms of specific social groups affected by exclusion the ministers’ messages showed the following prioritisation: 64% SEN, 27% minorities, 26% the poor, 19% girls/women, 16% dropouts, 16% migrants, and 14% out of school children. The analysis clearly shows that SEN students are the type of excluded population most referred to in almost all the Ministers’ messages. The IBE committee concluded that a high degree of consensus exists across regions and country groupings around students with special educational needs (SEN) as “the” priority group for any inclusive education policy. Nowhere do we see gifted students as an excluded group in any of the ministers’ messages. Additionally, even if SEN students were sometimes mentioned together with other marginalized groups, a good number of ministers’ statements only referred to SEN students as the excluded group.

Despite this dominant narrow view to inclusive education, what the researchers also found interesting in the analysis of the Ministers’ message was a recurring topic throughout the statements of the need to face the challenges of the 21st century knowledge-based economy (KBE) and the importance of educating responsible citizens that have the necessary competencies for entering the labour market, participating in society, and contributing to its development. This rationale is key to the economic function of education and STEM skills are prioritised in this regard based on empirical evidence. For example, findings from a 25-Year Longitudinal Study of Elite STEM Graduate Students confirmed that innovations from occupations in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) fuel the engines of modern economies (McCabe et al., Citation2020). However, the truly extraordinary advances in STEM have not been the work of typical individuals in the STEM workforce. Rather, rare, talented, and committed individuals within STEM have produced such advances. Individuals who pursue STEM disciplines have a different intellectual problem-solving orientation; they approach learning, work, and novel challenges with a different configuration of talents. They possess a different intellectual design space for problem solving and creative thought. Both STEM leaders and non-leaders have well-defined STEM interests and were mathematically talented. So while giftedness in general should be valued in the broader inclusive view, the need for talent development of the mathematically gifted students is even more pressing in the 21st century KBE. Given this centrality of mathematics in all sciences, longitudinal studies have shown that mathematically gifted individuals have the potential to become the critical human capital needed for driving modern day economies (Lubinski & Benbow, Citation2021). Driven by such results, the potential contribution of the mathematically gifted and talented to self, family, nation, and the global economy is becoming increasingly important more than ever before; hence, policy makers and the leaders of business and finance express a growing interest in gifted education in its various formats. In South Africa, a report by a task team, which investigated the challenges in Mathematics Science and Technology Education (MSTE) or (STEM) pointed to a section 5.2 (p47) which focused on specific areas where particular intervention had been identified, as necessary. In section 5.2.2. (p48) and with specific reference to “Talent Search & Development”—the task team observed that more often than not, provincial education departments seem to focus on underperforming schools to the neglect of gifted learners and learners with MST potential (DOE, Citation2013).

The third and final research question focused on teacher perceptions and practices about inclusive education with a special attention to gifted students. In designing the classroom checklist, there was particular interest to see how the teacher differentiated the content in terms of planning, pacing, task variety and cognitive demand levels. This decision was based on empirical evidence showing that intellectual giftedness is most closely related to the need for differentiation in the academic curriculum. Specifically, it is necessary to be vigilant in scrutinising how deficit assumptions (such as the narrow view to inclusive education) may influence perceptions about certain students, e.g., disabled, and gifted. Design, selection and use of particular teaching approaches and strategies arise from perceptions about learning and learners. In this respect, even the most pedagogically advanced methods are likely to be ineffective in the hands of those who implicitly or explicitly subscribe to a belief system that regards some students (disabled), at best, as disadvantaged and in need of fixing, or, worse as deficient and beyond fixing. The results from the analysis show that teachers planned and taught students following a one-size-fits-all teacher centred approach. Educators did not deviate from the set curriculum in order to cater for the needs of gifted learners. Similar studies, e.g., Vialle & Rogers (2009) found that students wanted student-centred learning, enrichment/extension, and support, but what teachers provided was teacher directed learning. In a similar South African study by Stofile (Citation2008), results showed that at the school level, the majority of the mainstream teachers and parents understood inclusion to be a system that seeks to integrate learners with disabilities and other learners with special needs into the mainstream schools. All these understandings focused on the disability aspect of inclusion as a defining feature.

This paper concludes by pointing to an urgent need for a broader concept of inclusive education to be articulated in both the international and national policy frameworks. The view is that the move towards a broader conceptualisation of inclusion would be consistent with the demands of the 21st knowledge-based economy. The focus on the importance of “21st century” skills has enriched current thinking on educational policies, content and methods, and mathematically gifted students are central to these debates. The underlying and often implicit rationale is the need for creativity and entrepreneurship for greater competitiveness in a knowledge-based-economy. This rationale is key to the economic function of education. Almost two decades ago, Renzulli & Reis (Citation1991:34) closed their critical review of an ongoing educational reform by stating that: “Talent development is the “business” of our field, and we must never lose sight of this goal, regardless of the direction that reform efforts might take”. Gagne (Citation2011) would slightly modify that statement by describing schools’ “business” as academic talent development. According to Gagné, this does not deny openness to other forms of talent development (e.g., in arts or sports), but it identifies academic pursuits as the core mission of schools, and academic talent development (ATD) as the school system’s specific mission with regard to its academically talented students.

In light of these long-standing observations, the purpose of education should be revisited in line with a renewed vision of sustainable human, economic and social development that is both equitable and viable. Education can, and must, contribute to this new vision of sustainable global development. In this regard, an empowering inclusive education is one that builds the human resources we need to be productive, to continue to learn, to solve problems, to be creative, and to live together and with nature in peace and harmony. When nations ensure that such an education is accessible to all throughout their lives, a quiet revolution is set in motion: education becomes the engine of sustainable development and the key to a better world. To this end, a broadened concept of inclusive education can be viewed as a general guiding principle to strengthen education for sustainable development, lifelong learning for all and equal access of all levels of society to learning opportunities so as to implement the principles of inclusive education.

Author contributions

MJN collected data in the schools. MKM collected data from the international and national documents. MKM conceptualised the paper. Both authors wrote and reviewed the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

This study is supported financially by the National Research Foundation (NRF) through Thuthuka Project – TTK150721128642, UNIQUE GRANT NO:99419. The results, conclusions and recommendations expressed in this study will be for the authors and will not reflect the views of the National Research Foundation.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

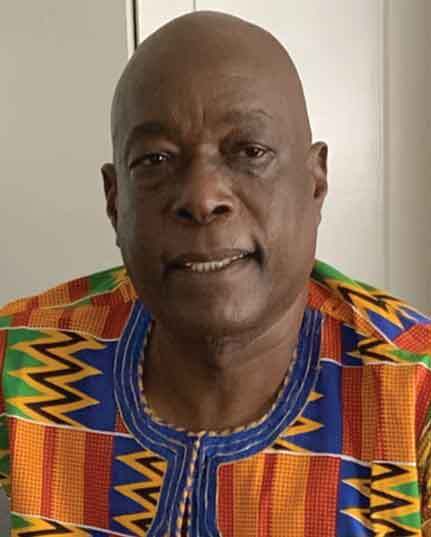

Michael Kainose Mhlolo

Prof Michael Kainose Mhlolo holds a PhD in Mathematics Education from the University of the Witwatersrand – Johannesburg. He is a Full Professor and a rated researcher on the South African National Research Foundation [NRF] system. He is a member of the World Council for Gifted and Talented Children [WCGTC]. He is also an executive committee member of the International Group for Mathematical Creativity & Giftedness [MCG]. He has a cumulative total of 37 years experience in education and his niche area of research is in giftedness in general and mathematical giftedness in particular.

Maleshoane Jeanette Ntoatsabone

Mrs Maleshoane Jeanette Ntoatsabone is a PhD candidate under the supervision of Prof Mhlolo. This paper was conceptualised from the candidate’s thesis which has just been submitted for external examination. This is part of the work we are doing on the research project on gifted education in South Africa.

References

- Arduin, S. (2015). A review of the values that underpin the structure of an education system and its approach to disability and inclusion. Oxford Review of Education, 41(1), 105–20.

- Barroco, S. M. S. (2018). Vygotsky’s theories on defectology: Contributions to the special education of the 21st century. Educacao (Porto Alegre), 41(3), 374–384.

- Betiku, O. F. (1999). Resources for the effective implementation of the 2 and 3 dimensional mathematical topics at the Junior and Senior secondary school levels in the Federal Capital Territory, Abuja. Nigerian Journal of Curriculum Studies, 6(2), 49–52.

- Brunsson, N. (2000). The irrational organisation: Irrationality as a basis for organisational action and change.

- Colebatch, H. H. (2002). Policy (2nd ed.). Buckingham. Open University Press.

- Daniels, E. A. (2012). Sexy versus strong: What girls and women think of female athletes. Journal of Applied Development Psychology, 33(4), 79–90.

- DBE, (2019). Annual report 2018/2019. Pretoria, Department of Basic Education. https://nationalgovernment.co.za/department_annual/265/2019-department-of-basic-education-(dbe)-annual-report.pdf

- DOE. (2013). The ministerial task team report on: Investigation into the implementation of maths, science & technology education (Ministerial). Department of Basic Education.

- Gagne, F. (2011). Academic talent development and the equity issue in gifted education. Talent Development & Excellence, 3(1), 3–22.

- Hardy, I., & Woodcock, S. (2015). Inclusive education policies: Discourses of difference, diversity and deficit. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 19(2), 141–164.

- Haug, P. (2017). Understanding inclusive education: Ideals and reality. Scandinavian Journal of Disability, 19(3), 206–217.

- Herberg Davis, H. (2009). Myth 7: Differentiation in the regular classroom is equivalent to gifted programs and is sufficient: Classroom teachers have the time, the skill and the will to differentiate adequately. The Gifted Child Quarterly, 53(4), 251–253.

- Jansen, J. D. (2001). Explaining change and non-change in education after apartheid. In Y. Sayed & J. Jansen (Eds.), Implementing education policies: The South African experience (pp. 250–271). University of Cape Town Press.

- Kokot, S. J. (2011). Addressing giftedness. In E. Lansberg, D. Kruger, & N. Nel (Eds.), Addressing barriers to learning: A South African perspecitive (2nd) ed.). (pp. 501–526). Van Schaik.

- Krippendorff, K. (1980). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology. Sage.

- Lubinski, D., & Benbow, C. P. (2021). Intellectual precocity: What have we learned since terman. Gifted Child Quarterly, 65(1), 3–28.

- Magnusson, G. (2019). An amalgam of ideals - images of inclusion in the Salamanca statement. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 23(7–8), 677–690.

- McCabe, K. O., Lubinski, D., & Benbow, C. P. (2020). Who shines most among the brightest? A 25-year longitudinal study of elite STEM graduate students. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 119(2), 390–416.

- Milne, A., & Mhlolo, M. K. (2021). Lessons for South Africa from Singapore’s gifted education – a comparative study. South African Journal of Education, 41(1). https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v41n1a1839

- Norwich, B. (2014). Recognising value tensions that underlie problems in inclusive education. Cambridge Journal of Education, 1–16.

- Oswald, M., & de Villiers, J. M. (2013). Including the gifted learner: Perceptions of South African teachers and principals. South African Journal of Education, 33(1):1–21.

- Renzulli, J. S., & Reis, S. M. (1991). The reform movement and the quiet crisis in Gifted Education. The Gifted Child Quarterly, 35(1), 26–35.

- Rimm, S. B., Siegle, D., & Davis, G. A. (2018). Education of the gifted and talented. Pearson Education.

- Stofile, S. Y. (2008). Factors affecting the implementation of inclusive education policy: A case study in one province in South Africa. Unpublished Doctoral Thesis. University of Western Cape.

- Stubbs, S. (2008). Inclusive education - where there are few resources. The Atlas Alliance.

- Tanenbaum, C. (2016). STEM 2026: A vision for innovation in STEM Education. American Institute for Research, U.S. Department of Education and Office of Innovation and Improvement. https://innovation.ed.gov/what-we-do/stem/

- Thomas, G. (2013). A review of thinking and research about inclusive education policy, with suggestions for a new kind of inclusive thinking. British Educational Research Journal, 39(3), 473–490.

- UNESCO, (1994). The Salamanca Statement and Framework for Action on Special Needs Education.

- UNESCO. (2009). Inclusive Education: The way of the future. Paris: International Bureau of Education.

- Vik, S., & Somby, H. M. (2018). Defectology and inclusion. Issues in Early Education, 3(42), 94–102.

- Vygotsky, L. (1993). The fundamentals of defectology. In R. W. Rieber & A. S. Carton (Eds.), The collected works of L. S. vygotsky (Vol. 2, pp. 29–93). Plenum Press.

- Vygotsky, L. (1995). Problems of defectology. Prosvecshenie Press.

- Vygotsky, L. (2004). Imagination and creativity in childhood. Journal of Russian and East European Psychology, 42(1), 7–97.

- Xolo, S. (2007). Developing the potential of the gifted disadvantaged in South Africa. Gifted Education International, 23(2), 201–206.