Abstract

Although the grid management system has been in practice for more than a decade, less is known about the system and satisfaction among the people to whom the system applies. This study answers three questions; (i) what is a grid management system? (ii) How did higher education institutions use it during the pandemic? And (iii) How was the students’ satisfaction with their level of engagement and perceived college support (P_C_S)? A total of 306 international students at Zhejiang Normal University completed an online survey. SPSS 26 and PROCESS macro was used to analyze the results. The results showed a strong positive correlation of P_C_S with students’ engagement (r = 0.635, p < 0.05) and life satisfaction (r = 0.694, p < 0.05), while P_C_S significantly affected students’ engagement (β = 0.540, SE = 0.082, p < 001) and life satisfaction (β = 0.524, SE = 0.082). The system was an imperative means of controlling the spread of the pandemic, with P_C_S playing a critical role in ensuring students’ engagement.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Institutional management is a general concept that includes several approaches to ensuring that things are done within the institution. However, creativity is an imperative element in ensuring that such management is inclusive and operates at the level of the highest satisfaction. A two-way flow of information between the managing team and the managed group, frequent communication, and inclusivity has a significant impact on ensuring satisfaction among the common people. In our case, the Grid Management System (GMS) has helped both, the university management and students at ensuring COVID control, and life satisfaction within the institutions

1. Introduction

On March 12th, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 the global pandemic (WHO, Citation2020b) while governments throughout the world responded by adopting different measures to prevent the spread of the virus (Stephenson et al., Citation2022). As of February 2nd, 2022, more than 380 million global confirmed cases and five million deaths were reported. Europe had the most cases (more than 147 million), followed by America (136 million). The infection rate has been varying regionally, as, by January 13th, 2020 China reported 125 confirmed cases and 80 cases as a weekly increase, while the United States was yet to register a single case. A week later (January 20th, 2020), China reported more than 14,000 cases, and the United States recorded its first two confirmed cases (WHO, Citation2022b).

Chinese governments adopted various strategies, including social distancing, closure of educational institutions, wearing masks, and burning international travel (Xu et al., Citation2020). The efforts yielded better results, as by April 23rd, 2020, China had fewer cases (84,302) compared to the United States (800,926), Spain (208,389) and Italy (187,327; WHO, Citation2020a). On September 8th, 2020, the President of the People’s Republic of China hailed China’s spirit of combating COVID-19 as he honored Zhong Nanshan and other medical professionals as the model virus fighters (ChinaToday, Citation2020). By February 2nd, 2022, more than 3 billion vaccine doses have been distributed and administered throughout the country (WHO, Citation2022a). Table shows cases and vaccination records among the selected countries as of February 4th, 2022.

Table 1. The current situation in five countries with most cases as compared to China

In education institutions, the pandemic resulted in negative psychological feelings like depression and distress, with older students being more psychologically affected (Akhtarul Islam et al., Citation2020). It affected students’ well-being, life satisfaction, and general mental health, with female students being more prone than males (Fute et al., Citation2022). There was also an increase in suicidal thoughts among students over time, while the quality of sleep worsened (Kaparounaki et al., Citation2020). Although several measures of controlling the pandemic have been documented, Grid Management System is yet to receive enough attention. This study describes the system, explores students’ engagement, satisfaction, and institutional support during the implementation of the system.

2. Methods

2.1. Procedure

Literature related to the grid management system was collected and analyzed. Participants participated in an online survey shared using a Chinese data-collection platform (Credamo) from February 2021 to June 2021. The sample included only international students with the challenge of most of them having returned to their country after the outbreak of COVID-19. The Ethics Committee of Zhejiang Normal University’s College of Teacher Education approved the study and followed the Declaration of Helsinki. All the participants voluntarily completed the survey

2.2. Participants

We collected data from international students at Zhejiang Normal University (n = 306) with a response rate of 94.63% (Male = 108, Female = 198). Respondents’ grades of study ranged from bachelors to doctorate, majority being bachelor’s students (57.9%), with the average age of 25.02 years (SD = 5.73). Table below shows a detailed participants’ information.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics for respondents (n = 306)

2.3. Measurement scales

Life satisfaction: Students’ satisfaction with life was measured by Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS), a Portuguese scale developed by Diener, Emmons, Larsen, and Griffin (Citation1985), translated and validated by Carlos Antonio Laranjeira in 2009. It comprises five items rated on a 7-point Likert scale from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 5 (Strongly agree; Laranjeira, Citation2009). The Cronbach’s alpha of this scale in this study was 0.86.

Engagement: The study adopted Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES), revised and validated by Li Xiying in 2010. It consists of 17 items rated on a 7-points Likert scale from 0 (Never) to 7 (Always). The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of the scale in this study was 0.95.

Perceive college support: Students perceived college support was measured using the Perceived Organizational Support (POS) scale that comprises eight items measured on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (Strongly agree) to 5 (Strongly disagree; Eisenberger et al., Citation1986). In this particular survey, the Cronbach’s alpha of this scale was 0.90.

3. Results

3.1. Qualitative results: The description of the grid management system

A grid management system is a bi-directional administration approach that divides the urban communities into discrete management units. As part of the broader administrative region, grids are smaller groups of people within their geographical localities (Mittelstaedt, Citation2021). The term “grid” is developed from “baojia system” (保甲制) employed during the Song dynasty in the 11th century. Baojia involved communities divided into jia (甲), consisting 10 families based on their geographical and social context (i.e., urban density). Leader collected information, spread knowledge and information, and liaised with other leaders (CMP, Citation2021). They also worked vertically and horizontally as bridging agents of information flow between grid leaders, members, and the immediate top management unit (CMP, Citation2018). The system was for providing service and resolving conflicts before they escalated to a larger scale of social unrest (Yongshun, Citation2018).

3.2. The grid management system at Zhejiang Normal University

At Zhejiang Normal University each grid comprised almost ten grid members (students). Four major streets surround the university, namely (Luojiatan, 罗家谈) in the south, Beimen (北门) in the north, (Gaosun Lu, 高村路) in the East, and New York in the west side of the university. Each college formed several grids in the four streets to manage students of a particular college. Above the college administration level, the university central management unit monitored all the colleges. The college also provided grid members with the necessary information, seminar training, and material support to promote the well-being of all college members. The flow of information was bi-directional (Figure ) because colleges reported to the university administration. On the second, the university administration communicated to students through their respective colleges, superior leaders, and down-to-the-grid leaders.

Figure 1. Caption: The bi-directional approach of communication in a grid system.

There were three management unit levels in the college of teacher education. From the bottom, grid members communicated and received information from the college through grid leaders. Each grid had one grid leader who acted as a communication bridge between grid members and immediate superiors. While grid leaders were selected from among the grid members, immediate superiors (leaders) were among the college staff. Two superior leaders worked at the teacher education college as a communication bridge between grid leaders and the college administration. The college management was practically under one person who worked as an intermediating link between the college students and the university administration. Figure shows the bi-directional nature of the grid system in a hierarchical order of different leadership units.

Paths’ A1’, “B1”, and “C1” show a direct top-down flow of information, knowledge, and service from the college and immediate superiors to grid members (team) and grid leaders. In contrast, paths’ A2’, “B2”, and C2 show a bottom-up flow of information, request, or complaints from grid team members and grid leaders to immediate superiors and college administration. These two-way direct flows of information and services are explicitly employed in a case where the immediate superiors and the grid leaders, for one reason or the other, are either not accessible or fail to address students’ concerns to the college or college’s concern to students. In another case, grid leaders will also communicate about any issue in their grids. Topics may range from strategies to handle the newly emerged issue within grids or ways to improve services to grid members.

3.3. Controlling the spread of coronavirus by using a grid management system

Prevention measures have been at the heart of COVID-19 control throughout China. Studies have indicated that the delay of control measures by one, two, or three weeks in China would increase the number of infections by 3, 7, and 18 times respectively (Lai et al., Citation2020). In Hubei specifically, without implementing mandatory measures like ‘the closure of cities for the first five days, the epidemic scale would triple in China (Meng et al., Citation2022; Yang et al., Citation2020). Zhejiang Normal University is one of the Chinese educational institutions which employed several necessary measures, including a grid management strategy to control the spread of the pandemic among students.

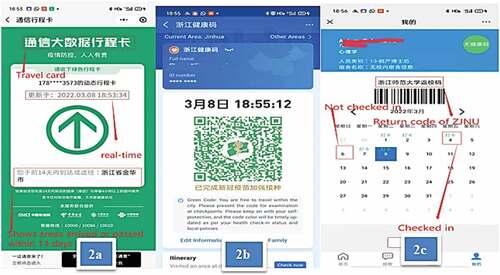

With the grid management strategy, controlling students’ unnecessary movement was possible. Alipay, WeChat, and other university databases were vital during the pandemic in prohibiting students from intermingling with other people from outside the city. As shown in Figure , a traveling code (通信大数据行程卡) was integrated into WeChat for recording students’ travel history within a specific period. Zhejiang health code (浙江健康码) shown in Figure was integrated with Alipay for recording and updating students’ health status. The code automatically changed into different colors in response to a student’s health status, especially when the subject’s Alipay information matches the traveling history. Figure shows a well-designed online students’ daily check-In form (浙江师范大学返校码) in which students were supposed to fill in their health and traveling-related information daily, including reporting any experience of abnormal health conditions like temperature rising. The college provided each grid member (students) with a free thermometer to ensure the accuracy of information filled in a daily check-in.

Grids leaders encouraged, motivated, and reminded every student to participate in the daily check-in by trustfully filling out each item. Leaders had access to sub-units of the general database regarding students’ records of check-in and reminded (by phone calls) each student to check in every day before midnight. All grid members were supposed to screenshot their health code (Figure ) and travel code (Figure ) and send them to grid leaders, who will also send them to the college administration through their immediate superiors (leaders). In a case where the college identified rules violation, the college leaders directly called the specific student to give a warning. Figure shows the online control system for traveling and health records.

Each grid had a WeChat group in which all the critical notices regarding COVID-19 control were published. The college published the updated list of cities and provinces (daily) that were in critical condition of infection and not safe to visit. Through superior leaders and grid leaders, the college encouraged grid members to avoid unnecessary movement or inform the college management through their grid leaders in case there is a need to travel to any city (except at-risk cities). The use of masks was highly encouraged, and the college distributed free masks to each grid member. The daily release of accurate pandemic-related information by the university overpowered the influence of rumors which would psychologically affect students (Rocha et al., Citation2021; Tasnim et al., Citation2020). The grid management system was a mechanism through which the university’s top-management staff indirectly contacted each student daily. The university knew each student’s daily temperature, travel history, and mental state through a grid system.

3.4. Quantitative results: Students’ perception, engagement, and life satisfaction

3.3.1. Confirmatory factor analysis

To test our hypotheses, we conducted the discriminant validity of the measurement model for parenting method, learning engagement, and academic achievement using a series of confirmatory factor analyses CFAs, GFI, SRMR, TLI, RMSEA, and ECVI. More details are in Table .

Table 3. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) results

3.5. Correlation and descriptive results

We ran the correlation analysis between variables, including respondents’ biographical information (age, gender, and learning grades), and our three main variables; students’ perceived college support (P_C_S), engagement in grid management strategy, and their life satisfaction during the pandemic. The results indicated a strong and positive correlation of students’ P_C_S to their engagement (r = 0.635, p < 0.05), and life satisfaction (r = 0.694, p < 0.05). Students’ engagement had also strong and positive correlation with students’ satisfaction (r = 0.542, p < 0.05). Table below shows all the correlation results in detail, especially the weak correlation between students’ biographies and the three main variables. Students’ scores for their P_C_S (M = 4.09, SD = 0.85), engagement (M = 3.96, SD = 0.77), and life satisfaction (M = 4.31, SD = 0.76) were all above the average.

Table 4. Correlation results of variables (N = 306)

3.6. The effect of students’ perceived college support and engagement on their life satisfaction

The regression analysis showed a high positive and significant effect of perceived college support (β = 0.524, SE = 0.082) and a relatively lower and statistically insignificant but positive effect of students’ engagement (β = 0.169, SE = 0.091) on students’ life satisfaction during the pandemic. All these results are at the confidence level of 95%. Table below displays more details on the impacts of students’ perceived college support and engagement on their general life satisfaction.

Table 5. Impact of perceived college support and students’ engagement on life satisfaction

4. Discussion

College support during the pandemic, primarily through the grid management strategy, was imperative for students’ life satisfaction. Students who felt high support from the college reported high life satisfaction. The effect of perceived college support on students’ life satisfaction was high and positive, aligning with our first hypothesis. The findings are in line with the previous studies before the outbreak of the pandemic on the importance of organizational support (Chatzittofis et al., Citation2021; Farooqi et al., Citation2019; Oubibi et al., Citation2022). However, the current study adds new findings related to the complications brought out by the pandemic. College support at Zhejiang Normal University played an important role during the implementation of the grid management system and in the promotion of students’ life satisfaction

The findings supported the hypothesis, which proposed P_C_S’s significant and positive contribution to students’ life satisfaction. However, the assumption was not supported regarding the effect of students’ engagement on their life satisfaction as the findings showed statistically insignificant results. The findings are also in line with the previous literature, which proposed that student engagement at school strongly correlates with their life satisfaction (Cleofas, Citation2020; Farooqi et al., Citation2019). Students are encouraged to engage in all the curricular and non-curricular activities for life satisfaction and academic achievement (Rajabalee & Santally, Citation2021), which is the rationale for being at school.

5. Limitations of the study and suggestions for further studies

The study involved only international students from Zhejiang Normal University. Only 306 students responded to this survey because most returned to their home countries early after the coronavirus outbreak. All the respondents of this study were in the university throughout the pandemic period and participated in all the activities within their respective grids. However, students who completed the online survey provided complementary information to the pieces of literature reviewed about the grid system. In the future, the number of respondents can be added more, primarily when a study is conducted in a university with enough international students.

6. Conclusion

The grid management system has proven to be one of the best strategies for managing an enormous population in higher education institutions. However, institutional support is imperative for effective and successful system implementation. When the system operates effectively, addressing students’ affairs like services, security, and control of students’ movement during the pandemic becomes easy. The system works smoothly even when the proportion of students and university staff is imbalanced. Institutional support positively contributes to students’ engagement with the design and general life satisfaction. The grid management system aimed to control the spread of the coronavirus among international and native students in China. The results in this study reveal the effectiveness of the system and its effects on students’ life satisfaction

Ethics statement

Ethics approval was granted by the Ethics Committee of the local University’s College of Teacher Education (Protocol code: 20,210,069) approved in 2021.04.01.

Consent to participate

All participants participated in this study in a voluntary basis. No any amount of money was paid for their participation. Participant read and signed a consent form prior to their participation. The form stated their right to withdraw any of their contribution at any point of the research process if they felt to do so.

Authors’ contribution

All the authors fully participated in accomplishing this article. A.F. and M.O. designed the study and analyzed the data by using SPSS, wrote the first draft of the manuscript, worked on ethical approval and collected all the information from the college. S.H.A.A prepared all the figures. A.A.L and N.M.A.V collected data from students and coded them before importing into SPSS for analysis. J.Z and B.S proofread the manuscript and prepared the last version of the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Antony Fute

Antony Fute is currently a research fellow at Zhejiang Normal University (China). He is an expert in the field of International and Comparative Education studies (policy studies), linguistics, and psychology. Dr. Fute has published a number of research papers, conference proceedings, and book chapters in areas of education policy, psychology, and ICT in education. He is more interested on education opportunities among the socially disadvantaged groups.

References

- Akhtarul Islam, M., Barna, S. D., Raihan, H., Khan, N. A., & Tanvir Hossain, M. (2020). Depression and anxiety among university students during the COVID-19 pandemic in Bangladesh: A web-based cross-sectional survey. PLoS ONE, 15(8), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0238162

- Chatzittofis, A., Constantinidou, A., Artemiadis, A., Michailidou, K., & Karanikola, M. N. K. (2021). The Role of Perceived Organizational Support in Mental Health of Healthcare Workers During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Study. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.707293

- ChinaToday. (2020). Xi hails China’s COVID-19 combat spirit as model virus fighters honored. China Today. http://www.chinatoday.com.cn/ctenglish/2018/zdtj/202009/t20200909_800220270.html

- Cleofas, J. V. (2020). Student involvement, mental health and quality of life of college students in a selected university in Manila, Philippines. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 25(1), 435–447. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673843.2019.1670683

- CMP. (2018). China under the Grid. China Media Project. https://chinamediaproject.org/2018/12/07/china-under-the-grid/#:~:text=The.term.%E2%80%9Cgrid.management%E2%80%9D.is.a.neologism.in,jia.combined.to.form.a.single.bao.%28%E4%BF%9D%29

- CMP. (2021). Grid Based management. China Media Project. https://chinamediaproject.org/the_ccp_dictionary/grid-based-management/

- Eisenberger, R., Huntington, R., Hutchison, S., & Sowa, D. (1986). Eisenberger 1986 JAppPsychol POS original article. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71(3), 500–507. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.71.3.500

- Farooqi, M. T. K., Ahmed, S., & Ashiq, I. (2019). Relationship of Perceived Organizational Support with Secondary School Teachers’ Performance. Bulletin of Education and Research, 41(3), 141–152. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1244691

- Fute, A., Oubibi, M., Sun, B., Zhou, Y., & Xiao, W. (2022). Work Values Predict Job Satisfaction among Chinese Teachers during COVID-19: The Mediation Role of Work Engagement. Sustainability, 14(3), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031353

- Kaparounaki, C. K., Patsali, M. E., Mousa, D. P. V., Papadopoulou, E. V. K., Papadopoulou, K. K. K., & Fountoulakis, K. N. (2020). University students’ mental health amidst the COVID-19 quarantine in Greece. Psychiatry Research, 290, 113111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113111

- Lai, S., Ruktanonchai, N. W., Zhou, L., Prosper, O., Luo, W., Floyd, J. R., Wesolowski, A., Santillana, M., Zhang, C., Du, X., Yu, H., & Tatem, A. J. (2020). Effect of non-pharmaceutical interventions to contain COVID-19 in China. Nature, 585(7825), 410–413. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2293-x

- Laranjeira, C. A. (2009). Preliminary validation study of the Portuguese version of the satisfaction with life scale. Psychology, Health and Medicine, 14(2), 220–226. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548500802459900

- Larsen, R. J., Diener, E., & Emmons, R. A. (1985). An evaluation of subjective well-being measures. Social Indicators Research, 17, 1–18.

- Meng, X., Guo, M., Gao, Z., Yang, Z., Yuan, Z., & Kang, L. (2022). The effects of Wuhan highway lockdown measures on the spread of COVID-19 in China. Transport Policy, 117, 169–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2022.01.011

- Mittelstaedt, J. C. (2021). The grid management system in contemporary China: Grass-roots governance in social surveillance and service provision. China Information, 2–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/0920203X211011565

- Oubibi, M., Fute, A., Xiao, W., Sun, B., & Zhou, Y. (2022). Perceived Organizational Support and Career Satisfaction among Chinese Teachers: The Mediation Effects of Job Crafting and Work Engagement during COVID-19. Sustainability (Switzerland), 14(2), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14020623

- Rajabalee, Y. B., & Santally, M. I. (2021). Learner satisfaction, engagement and performances in an online module: Implications for institutional e-learning policy. Education and Information Technologies, 26(3), 2623–2656.

- Rocha, Y. M., de Moura, G. A., Desidério, G. A., de Oliveira, C. H., Lourenço, F. D., & de Figueiredo Nicolete, L. D. (2021). The impact of fake news on social media and its influence on health during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. Journal of Public Health (Germany), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-021-01658-z

- Stephenson, E., O’Neill, B., Kalia, S., Ji, C., Crampton, N., Butt, D. A., & Tu, K. (2022). Effects of COVID-19 pandemic on anxiety and depression in primary care: A retrospective cohort study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 303, 216–222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2022.02.004

- Tasnim, S., Hossain, M. M., & Mazumder, H. (2020). Impact of rumors or misinformation on Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) in social media. Journal of Preventive Medicine and Public Health, 53, 171–174. https://doi.org/10.3961/jpmph.20.094

- WHO. (2020a). Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): Situation Report. World Health Organization.

- WHO. (2020b). WHO announces COVID-19 outbreak a pandemic. The World Health Organization. https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/health-emergencies/coronavirus-covid-19/news/news/2020/3/who-announces-covid-19-outbreak-a-pandemic

- WHO. (2022a). China situation. The World Health Organization. https://covid19.who.int/region/wpro/country/cn

- WHO. (2022b). WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard: Situation by region, country, territory and area. The World Health Organization. https://covid19.who.int/table

- Xu, T. L., Ao, M. Y., Zhou, X., Zhu, W. F., Nie, H. Y., Fang, J. H., Sun, X., Zheng, B., & Chen, X. F. (2020). China’s practice to prevent and control COVID-19 in the context of large population movement. Infectious Diseases of Poverty, 9(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40249-020-00716-0

- Yang, Z., Zeng, Z., Wang, K., Wong, S. S., Liang, W., Zanin, M., Liu, P., Cao, X., Gao, Z., Mai, Z., Liang, J., Liu, X., Li, S., Li, Y., Ye, F., Guan, W., Yang, Y., Li, F., Luo, S., … He, J. (2020). Modified SEIR and AI prediction of the epidemics trend of COVID-19 in China under public health interventions. Journal of Thoracic Disease, 12(3), 165–174. https://doi.org/10.21037/jtd.2020.02.64

- Yongshun, C. (2018). Grid Management and Social Control in China. The Asia Dialogue. https://theasiadialogue.com/2018/04/27/grid-management-and-social-control-in-china/