Abstract

This study investigated how online learning, mandated for tertiary education over one year in Malaysia since March 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic, impacted students’ perceived learning performance and psychological well-being. This study focused on the relationship between academic motivation, psychological engagement (enthusiasm, perseverance, and reconciliation), and their impact on perceived learning performance and psychological well-being, with psychological engagement acting as a mediator. This study collected survey responses from 288 students at 49 higher learning institutions in Malaysia using purposive sampling in March 2022. The results revealed that intrinsic motivation is the sole predictor of enthusiasm engagement. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations jointly influence perseverance engagement, while reconciliation is significantly affected by all three types of motivations. The mediation analysis results suggest that enthusiasm engagement mediates the relationship between intrinsic motivation and two outcome variables. Furthermore, perseverance engagement mediates the relationship between both intrinsic and extrinsic motivations with the two outcome variables. In contrast, reconciliation serves as a mediator for the relationship between amotivation and learning performance, as well as the relationship between extrinsic motivation and both learning performance and psychological well-being. Overall, the study highlights the importance of academic motivation and psychological engagement in online learning in tertiary education.

1. Introduction

Many countries enforced lockdown or movement control to cope with the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, and physical classes also ceased during these periods. The switch from face-to-face classes to online learning was sudden to ensure the continuity of learning in education. Online learning was the sole delivery mode for higher education in Malaysia for about two years due to several phases of movement control order (MCO) enforced in the country, starting from 18 March 2020. Mental Health Foundation (n.d.) reported that one out of five youth might struggle with a mental health issue any year, and 75% of mental health problems are rooted in 24 years old. The switch from secondary school to higher education is considered a significant change in one lifetime. Tertiary education, with less academic support than secondary school, incurred higher psychological distress and severe mental illness among the tertiary students than the general population (Trpcevska, Citation2017). Digital learning is a flexible, creative, and engaging teaching platform. However, learners who need constant motivation and a structured learning environment may not be able to follow the pace of online learning, thus swiftly magnifying their anxiety and stress levels (Rimmer, Citation2020).

Researchers in various countries have studied the psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on university students regarding mental health status (Chen et al., Citation2020; Huckins et al., Citation2020), anxiety level (Wang et al., Citation2020), and change of behaviour (Patsali et al., Citation2020). Previous studies divulge that the pandemic has plunged tertiary students’ stress and anxiety into a worrying situation. There were a few articles found in the Malaysian context. Sundarasen et al. (Citation2020) reported that 6.6% and 2.8% of Malaysian university students experienced moderate to severe and most extreme anxiety levels, respectively, based on Zung’s self-rating anxiety scale (SAS). On the other hand, Irfan et al. (Citation2021) found a higher anxiety level among Malaysian tertiary students, in which 31.1% experienced moderate and 26.1% severe anxiety based on the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale 7-item (GAD-7). Al-Kumaim et al. (Citation2021), using a qualitative method, explored online learning challenges faced by university students during COVID-19; they found that 67.1% feel stress during COVID-19 lockdown. Nevertheless, the previous studies (Al-Kumaim et al., Citation2021; Irfan et al., Citation2021; Sundarasen et al., Citation2020) focused more on socioeconomic determinants and descriptive analysis instead of causal analysis and their data collection during the first phase of the online learning period (April to July 2020).

Students’ high dropout and failure in COVID-19 pandemic and online learning have raised concerns to the public. Seventeen thousand six hundred thirteen (17,613) tertiary students dropped out from public universities in 2021 (Free Malaysia Today, Citation2022). Academic engagement plays a vital role in fostering students’ attention and interest in the study, encouraging success and retention; it reduces absenteeism and dropouts due to tedium (Vayre & Vonthron, Citation2017). The relationships between academic motivation, psychological engagement, well-being, and learning performance in online learning have not been scrutinised thoroughly in Malaysian tertiary students.

Kotera and Ting (Citation2021) suggest positive psychological constructs concerning the mental health of Malaysian students, based on 153 students majoring in humanities at a Malaysian university. They reported that amotivation and engagement directly impact mental health; in contrast, well-being and self-compassion negatively impact mental health. Out of these, self-compassion plays a dominant role in mental health. We could only find Kotera and Ting (Citation2021) use positive constructs for well-being in Malaysia. However, well-being is one of the predictors, and the outcome is mental health. Besides, their data collection was before the pandemic and was not from the online learning perspective. Besides, their study treated engagement as a single construct using the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale for Students (UWESS). In contrast, our study assessed psychological engagement in three domains, namely enthusiasm engagement (affective), perseverance engagement (behavioural) and reconciliation engagement (cognitive) and explored their mediating role. This study elucidates how each dimension of engagement contributes to well-being and perceived learning performance amongst tertiary students.

Perceived learning performance is a metric that gauges how students feel about learning overall through intangible indicators like involvement, satisfaction, and attitude (Li et al., Citation2018; Vo et al., Citation2017). Since learning helps students gain information that they can apply to real-world circumstances, subjective metrics are an excellent way to gauge students’ overall attitude toward learning (Anthonysamy et al., Citation2019). Therefore, it is becoming increasingly important to consider students’ perceived learning performance in online learning settings.

This study focuses on synchronous online learning adopted by Malaysian higher education during the COVID-19 pandemic. In synchronous online learning, the instructor and the students in the course are logged on simultaneously and communicate directly via virtual classrooms and video conferencing, following a pre-scheduled timetable. The purpose of this study is to profile the motivation, engagement, well-being and learning performance of Malaysian tertiary students in the later phase of the pandemic.

This research aims to develop a framework for the impact of online learning on Malaysian university students’ psychological well-being and perceived performance. The antecedent variables are motivation and psychological engagements. The main objective of this research is to assess the impact of university students’ academic motivation and psychological engagement in online learning on psychological well-being and perceived performance. The specific objectives are:

to examine the influence of academic motivation on the psychological engagement in online learning among Malaysian tertiary students.

(2) to investigate how psychological engagement in online learning influences psychological well-being and perceived performance among Malaysian tertiary students.

(3) to determine if psychological engagement mediates academic motivation, psychological well-being, and perceived performance in online learning among Malaysian tertiary students.

2. Literature review

2.1. Self-determination theory and academic motivation

Kusurkar et al. (Citation2011) reviewed motivation as an exogenous and endogenous variable in various studies and literature in medical education. Their meta-analysis indicated that motivation is a substantial predictor of academic success, retention in studies, and well-being. Hartnett (Citation2016) identified that motivation is critical in developing and sustaining a sense of community and achievement in online learning contexts. Self-determination theory (SDT) has been used to research online learning situations. There are three categories of human motivation according to SDT, namely intrinsic motivation, extrinsic motivation and amotivation. Hsu et al. (Citation2019) defined intrinsic motivation as an act to perform due to its enjoyment, optimal challenges and pleasing; extrinsic motivation as an act to perform due to the expectation of different outcomes; and amotivation as the lack of initiative to perform.

Vallerand et al. (Citation1992) developed a measurement construct for intrinsic, extrinsic, and amotivation known as the academic motivation scale. Recent studies that employed the academic motivation scale were Bailey and Phillips (Citation2016) and Trpcevska (Citation2017) in Australia, and Kotera and Ting (Citation2021) in Malaysia. Kotera and Ting (Citation2021) reported that well-being positively correlates with engagement and intrinsic motivation. Bailey and Phillips (Citation2016) claimed that subjective well-being is associated with intrinsic motivation; extrinsic motivation does not affect academic performance as they predicted it should but is associated with meaning in life.

2.2. Psychological engagement in online learning

Although increasing concerns about student engagement, its definitions have not reached a scholarly consensus. Bowden et al. (Citation2019) studied engagement in four- dimension measures, i.e., affective, social, cognitive, and behavioural and their respective role and influences on student well-being, self-esteem, self-efficacy, transformative learning and institutional reputation. This study adopts Vayre and Vonthron’s (Vayre & Vonthron, Citation2017) approach, which considers engagement as a three-dimensional concept (enthusiasm, perseverance, reconciliation) related to affective, behavioural, and cognitive with the following definitions:

enthusiasm (affective dimension) refers to an individual’s inclination and interest toward the engagement and the energy and esprit characterizing engagement.

perseverance (behavioural dimension) refers to an individual’s efforts and actions in pursuing the required engagement regardless of the hardship encountered.

reconciliation (cognitive dimension) refers to an individual’s capacity to realize that to gain the full benefits of engagements, one needs to overcome difficulties and give up certain things.

There is growing interest in tertiary student well-being, but how it relates to engagement has not been well studied (Boulton et al., Citation2019). Prior research on the effects of student engagement and well-being either focused on a face-to-face teaching environment or a specific course, campus, or university, e.g., Boulton et al. (Citation2019) at a university campus in the United Kingdom; Kotera and Ting (2019) on undergraduate students majoring in humanities subjects at a Malaysian University; and Bowden et al. (Citation2019) on a business faculty of a renowned university in Australia. Boulton et al. (Citation2019) “s study indicated that engagement positively influenced happiness but surprisingly negatively influenced academic outcomes. Kotera and Ting (Citation2021) concluded that amotivation, engagement, self-compassion, and well-being jointly affected student mental health. Vayre and Vonthron (Citation2017) affirmed that students” engagement in the distance and online learning positively affects their learning quality, success, satisfaction, and personal development and is negatively associated with dropout.

2.3. Perceived learning performance

Students are the main players in education. Student growth in higher education is therefore of paramount concern to any university and a key factor in the overall performance of the university. Online learning can assist students in a variety of ways, including expanding and maximising their learning independence and classroom involvement, which has a significant impact on their academic performance and achievements (Hamdan & Amorri, Citation2022). The online learning experience showed that the didactic teaching approach is no longer successful since students were more involved in the learning process than in traditional teaching (Hope et al., Citation2021). They no longer view teachers as the exclusive knowledge source, but rather as learning facilitators, and they view online learning from many internet sites as their primary information source. These developments and progress of online learning are fuelled by perceived learning. When pupils have a meaningful learning experience, it is seen as personal growth. Meaningful learning is considered important when it helps a learner grasp a subject better.

Learning performance is an ongoing shift in students’ attitudes and skills that promote long-term information retention and transfer as determined by arbitrary standards (Soderstrom & Bjork,Citation2015). It is becoming increasingly important to include students’ perceived learning performance when evaluating online learning settings. The learning performance of students can be evaluated based on their learning experience, learning environment, and learning outcomes (Anthonysamy et al., Citation2019; Zhu, Citation2012). Student retention in online learning settings may be improved by perceived learning performance. However, there is no research on the variables influencing students’ learning performance in online classes during the COVID-19 pandemic (Rajabalee & Santally, Citation2020).

2.4. Psychological well-being

Psychological well-being should be distinguished from mental health and not used interchangeably (Akin, Citation2008; Wilkinson & Walford, Citation1998). Many researchers tense to use negative constructs for psychological well-being. For instance, Al-Salman et al. (Citation2022) explored the impact of digital tools on Jordanian university students’ well-being during COVID-19; the psychological well-being constructs like ”Prolonged use of e-learning tools often lead to boredom, nervousness and tension” was used. Trpcevska (Citation2017) remarked that a shift in the measurement of psychological well-being emphasised positive functions and protective factors rather than psychological distress and dysfunction. A psychological health person in positive constructs does not mean a person free of depression or anxiety but a person with a high level of resilience, social connections, and positive spirituality (Trpcevska, Citation2017). See, and Chuah (Citation2015) stated that a person with healthy well-being has a purpose in life, is sociable and capable of achieving their goals. Bailey and Philips use satisfaction in life, the presence of positive mood and the absence of negative mood to measure subjective well-being in their study conducted in Australia. Like Kotera and Ting (Citation2021), this study uses the Short Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale (SWEMWBS; Stewart-Brown et al., Citation2009) to measure psychological well-being.

3. Research methodology

3.1. Hypothesis development

This study examines the direct impact of academic motivation on psychological engagement, i.e. enthusiasm (affective), perseverance (behavioural) and reconciliation (cognitive) in online learning among Malaysian tertiary students. Hence the following hypotheses are put forward:

Hypothesis 1: Academic motivation influences the enthusiasm engagement of tertiary students toward online learning.

Hypothesis 2: Academic motivation influences the perseverance engagement of tertiary students toward online learning.

Hypothesis 3: Academic motivation influences the reconciliation engagement of tertiary students toward online learning.

Secondly, this study examines the impact of psychological engagement on perceived learning performance and psychological well-being in online learning among Malaysian tertiary students. Therefore, we develop the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 4: Psychological engagement influences the perceived learning performance of tertiary students towards online learning.

Hypothesis 5: Psychological engagement influences the psychological well-being of tertiary students towards online learning.

Lastly, this study examines the mediating role of psychological engagement on academic motivation with perceived learning performance and psychological well-being in online learning among Malaysian tertiary students. Hence the following hypotheses are proposed:

Hypothesis 6: Psychological engagement mediates the relationship between intrinsic motivation and perceived learning performance.

Hypothesis 7: Psychological engagement mediates the relationship between intrinsic motivation and psychological well-being.

Hypothesis 8: Psychological engagement mediates the relationship between extrinsic motivation and perceived learning performance.

Hypothesis 9: Psychological engagement mediates the relationship between extrinsic motivation and psychological well-being.

Hypothesis 10: Psychological engagement mediates the relationship between amotivation and perceived learning performance.

Hypothesis 11: Psychological engagement mediates the relationship between amotivation and psychological well-being.

While predicted outcomes consist of a single construct, academic motivation and psychological engagement are multiple constructs. Academic motivation comprises intrinsic motivation, extrinsic motivation and amotivation. Psychological engagement includes enthusiasm, perseverance, and reconciliation. The research framework is shown in Figure .

Figure 1. Research Framework.

3.2. Questionnaire designs and sampling method

This study applied the primary data collection method via self-administrative questionnaires created in the google form. The questionnaire provided to respondents consists of five primary sections. Section A consists of demographic and online learning experiences; respondents with synchronous online learning experiences during the pandemic proceed to the next section, while those without will directly submit the form. The first 244 respondents who leave a valid student email will receive an RM5 Touch NGO eWallet reload pin as a token of appreciation. Section B is optional for those who wish to receive the token of appreciation to provide their student email address for clarification. Then, sections C to E concern the constructs measurements of this study. Table tabulates the source of measurement constructs adapted in this study.

Table 1. Measurement Constructs of this study

All measurement constructs are rated based on a 5-Likert scale. Respondents rate themselves on the Academic Motivation Scale (AMS) to indicate to what extent the construct corresponds to why they study in university, 1 (do not correspond at all) to 5 (correspond exactly). The adapted AMS comprises intrinsic motivation (to know, toward accomplishment), extrinsic motivation (identified, introjected, and external regulation), and amotivation. For psychological engagement, respondents are to indicate to what extent the construct characterizes them, from 1 (do not characterize at all) to 5 (completely characterizes me) on three engagement dimensions: enthusiasm, perseverance, and reconciliation. For psychological well-being, respondents are to rate from 1 (none of the time) to 5 (all the time) on seven measurement constructs of the Short Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale (SWEMWBS) that describe their experience over the last two weeks. For perceived learning performance, respondents rate their level of agreement with each statement, from 1, strongly disagree, to 5, strongly agree.

This study employs purposive and convenience sampling methods for data collection. We disseminated the survey link via email, google classroom and social networking platforms like WhatsApp, Messenger, and Xiao Hong Shu. Purposive sampling ensures the respondents are full-time tertiary students aged 18 years or older with synchronous online learning experiences during the pandemic. The data collection took place from 11 March 2022–20 March 2022, over a year of enforcement in online learning in Malaysia (Palansamy, Citation2020; Ross, Citation2021). The G*Power provides a suggested minimum sample size of 146. Two hundred ninety respondents participated in this survey, omitting two respondents without an online learning experience, leaving 288 valid respondents. These 288 respondents are tertiary students with online learning experiences from 19 public and 30 private tertiary institutions, including universities and colleges in Malaysia.

4. Data analysis

4.1. Descriptive analysis

This study conducted descriptive analysis via SPSS version 28. Table summarises the respondents’ demographic profiles. 99% of respondents were 18–24, with an average age of 20.7. Female respondents constitute 65%, and 58% are Chinese. Private university students comprise 69%, 62% are undergraduates, and 76% have more than one year of an online learning experience. Of the field of study, about 46% from social science, 43% from technical sciences and the rest from health and biological sciences. This study has more female respondents, reflecting Malaysia’s and the worldwide trend of women being dominant in higher education (Statista, Citation2022).

Table 2. Demographics and general information

Table depicts the average and dispersion rating obtained for latent variables used in this study. All variables obtained ratings towards agreement (> 2.5) except for amotivation.

Table 3. Average scores and dispersion

Extrinsic motivation scored the highest agreement and lowest dispersion among all variables, with a mean value of 4.20 and a standard deviation of 0.55, followed by intrinsic motivation with a mean value of 4.13 and a standard deviation of 0.60. The descriptive shows that most respondents are motivated by extrinsic and intrinsic factors to study at universities, and it coincided with the lowest mean (2.23) obtained by amotivation.

For psychological engagement dimensions, perseverance engagement obtained a slightly higher mean (3.92) than reconciliation (3.90), whereas enthusiasm scored the lowest agreement (3.63). Respondents were inclined to agree more on perceived learning performance than psychological well-being among the two outcome variables.

4.2. Measurement constructs’ validation

Smart-PLS is used to validate the measurement constructs and examine the structural model. According to Hair et al. (Citation2019), PLS-SEM is suitable for predicting the theoretical framework with complexity and the need for latent variable scores for further analysis. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations are two higher-order constructs with the disjoint two-stage approach in this study. In the first stage, intrinsic motivation dimensions—to know (IMK) and toward accomplishment (IMC), and extrinsic motivation -identified (EMD), introjected (EMT) and external regulation (EMR), together with amotivation are connected directly to psychological engagement, then psychological engagement to two endogenous variables. Figure displays the PLS diagram.

Figure 2. Stage one of the disjoint two-stage approach.

We tabulate the results of the convergent validation criterion in Table . Convergent validity requires a minimum threshold of 0.7 for composite reliability, and AVEs for all latent constructs exceed the minimum threshold of 0.5 (Hair et al., Citation2017). As shown in Table , composite reliability ranges from 0.826 to 0.949, and AVEs range from 0.547 to 0.824. Both criteria exceed the minimum threshold. This study performed Fornell-Larker, cross-loading, and HTMT tests for discriminant validation. As the HTMT criterion is the most stringent, we only tabulate the HTMT criterion’s result as in Table . The highest HTMT value is 0.878, below the 0.90 thresholds stated by Henseler et al. (Citation2015); therefore, we validated the discriminant of latent variables.

Table 4. Convergent validity

Table 5. Discriminant Validity by Heterotraid-Monotrait (HTMT) Criterion

In the second stage, we use latent variable scores of lower-order constructs (IMC, IMK, EMD, EMT, EMR) from stage one to measure intrinsic motivation (IM) and extrinsic motivation (EM) variables, respectively. Then these two higher-order components (HOC) are used in the path model for further analysis. Tables tabulate the higher-order constructs’ convergent and discriminant validation (HTMT criterion). In Table , the HOC’s composite reliability values are above 0.7, and AVEs are above 0.5, which fulfilled the convergent requirement set by Hair et al. (Citation2017). Besides, the highest HTMT value in Table is 0.779, and the bias-corrected confidence intervals are free from a value of 1 (Henseler et al., Citation2015). Therefore, we validated the discriminant of latent variables for HOC.

Table 6. HOC’s convergent validation

Table 7. HOC’s Discriminant Validity by Heterotraid-Monotrait (HTMT) Criterion

Table shows the structural model’s assessment of the direct effects, and Figure portrays the structural model with the HOC constructs. For hypothesis 1, the results revealed that intrinsic motivation is the sole predictor of enthusiasm engagement with a beta value of 0.252 (p-value <0.01). Based on the R square value, academic motivation explains about 12% of the variation in enthusiasm engagement. For hypothesis 2, intrinsic and extrinsic motivation jointly influence perseverance engagement. Based on the beta value, intrinsic motivation has a slightly higher impact on perseverance engagement than extrinsic motivation. Academic motivation accounts for a 23% variation in perseverance engagement. For hypothesis 3, reconciliation is significantly affected by all three types of motivations, with extrinsic motivation having the most significant influence (B = 0.382, p < 0.05). The variation in academic motivation explains about 23.5% of the variation in reconciliation engagement.

Figure 3. Overview of structural model.

Table 8. Structural model’s assessment of the direct effects

For hypotheses 4 and 5, all hypotheses are supported with a p-value less than 0.01. All three dimensions of engagements jointly explained 53.5% of the variation in perceived learning performance and 41.5% of psychological well-being. Enthusiasm engagement is the most significant predictor of perceived learning performance and psychological well-being, with beta values of 0.368 and 0.283, respectively.

All Q2 values are above 0, so we conclude that our model demonstrates good predictive relevance (Hair et al., Citation2017). Cohen (Citation1988) defined f2 values of 0.02, 0.15, and 0.35 as a small, medium, and large effect sizes, respectively. In this study, 11 out of 15 hypotheses have small f2 effect sizes on the endogenous variable, whereas H4a has f2 > 0.15; this shows that enthusiasm engagement has a medium effect on learning performance.

4.3. Analysis of mediation effect

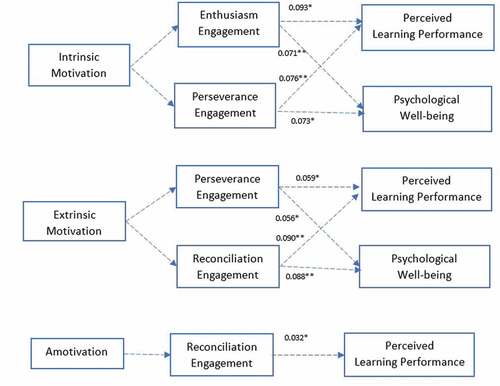

Table summarises the indirect effects of the mediation analysis, and Figure provides an overview of significant mediation effects. For hypotheses 6 and 7, intrinsic motivation indirectly affects perceived learning performance and psychological well-being through enthusiasm engagement and perseverance engagement, respectively.

Figure 4. Overview of significant mediation effects.

Table 9. Structural model’s indirect effects

For hypotheses 8 and 9, extrinsic motivation indirectly affects perceived learning performance and psychological well-being through perseverance engagement and reconciliation engagement, respectively. For hypothesis 10, amotivation indirectly affects perceived learning performance through reconciliation engagement. For hypothesis 11, there is no mediation effect on amotivation and psychological well-being.

In other words, mediation analysis revealed that enthusiasm engagement mediates intrinsic motivation’s relationship with perceived learning performance, and psychological well-being, respectively. Perseverance engagement mediates the relationship of intrinsic and extrinsic motivations with learning performance and psychological well-being, respectively. Interestingly, reconciliation mediates the relationship between extrinsic motivation and amotivation with learning performance but not intrinsic motivation. Besides, reconciliation mediates the relationship between extrinsic motivation and psychological well-being.

5. Discussions

This study investigates the impact of online learning on tertiary students’ perceived learning performance and psychological well-being. The prolonged COVID-19 pandemic has forced students to adapt to online learning for more than one year. The hypotheses established in this study helped address the research questions. This study’s findings indicated ten significant relationships and one insignificant relationship.

For the first objective, this study examines the direct impact of academic motivation on psychological engagement, i.e., enthusiasm (affective), perseverance (behavioural) and reconciliation (cognitive) in online learning among Malaysian tertiary students. Specifically, this study discovered that enthusiasm engagement is mainly influenced by intrinsic motivation, whereas perseverance engagement is affected by intrinsic and extrinsic motivations. Reconciliation engagement is affected by all motivations. This study revealed that academic motivation strongly influences reconciliation engagement (cognitive dimension in acknowledgement of difficulties of studies in various subject matters) which is much required in tertiary education, mainly on cognitive learning aspect, and recognizing the challenges and responsibilities of studies in academic learning through online learning. Besides, intrinsic motivation derived from a student’s internal drive and pursuit positively affects three domains of psychological engagement in online learning (Peng, Citation2021; Saeed & Zyngier, Citation2012) . For Malaysian tertiary students, extrinsic motivation and amotivation have partially supported correlations with the psychological engagement of online learning.

Most respondents believe that amotivation does not apply to them, demonstrating their continued belief in the value of higher education and their concern for their studies (De Agrela Gonçalves Jardim et al., Citation2017; Dandy & Bendersky, Citation2014). It is encouraging that most responders to this study had high intrinsic drives. The main reason people pursue tertiary education is the joy and satisfaction of discovering new things and outdoing oneself in personal achievements. The respondents gave extrinsic motivation the highest mean score. Better career options, pay, and a prominent job later in life match the external attractions motivating students to enrol in college or university. It has a tremendous impact on persistence and reconciliation engagements.

For the second objective, results showed that all three domains of psychological engagement (enthusiasm, perseverance, and reconciliation) significantly influence perceived learning performance and psychological well-being. Among these, enthusiasm (affective) engagement is the top predictor of perceived learning performance and psychological well-being, followed by perseverance (behavioural) engagement and reconciliation (cognitive) engagement. Despite its essential role, respondents in this study felt moderately enthusiastic about their study in online learning. Affective engagement involves students’ moods, and emotions are strategically crucial for learning. The finding highlights the importance of designing online learning experiences that are engaging, interactive, and supportive and addressing any issues that may be impacting students’ experiences and outcomes as highlighted by Gillett-Swan (Citation2017) and SchorlarLMS (Citation2020) on the importance of engaging content in e-learning.

Higher education institutions could implement the following strategies to enhance students’ enthusiasm for their studies: (a) active and engaging pedagogy: encourage instructors to use dynamic and engaging pedagogical approaches, such as hands-on activities, group work, and real-world projects, which can help to increase students’ motivation and engagement (Gillett-Swan, Citation2017; Martin & Bolliger, Citation2018; Peng, Citation2021). (b) student-centred learning: adopt a student-centred approach to learning, where students are given more control over their learning experience and encouraged to pursue their interests and passions. It helps to increase students’ intrinsic motivation and engagement (Gillett-Swan, Citation2017). (c) personalized feedback: provide students with timely, personalized feedback on their work to help them understand their strengths and weaknesses and track their progress (Martin & Bolliger, Citation2018). (d) technology integration: integrate technology, such as gamification and learning management systems, into the learning experience to increase interactivity and engagement. (e) opportunities for collaboration: foster a supportive learning community by providing opportunities for students to work together on projects, engage in peer-to-peer learning, and participate in extracurricular activities (Martin & Bolliger, Citation2018; Moodley et al., Citation2022) . (f) positive Relationships: encourage positive relationships between instructors and students, and between students themselves, by promoting a culture of respect, support, and inclusiveness (Moodley et al., Citation2022; g) recognition and rewards: recognize and reward students’ achievements and contributions inside and outside the classroom to help build their sense of accomplishment and pride in their work.

For the third objective, mediation analysis indicates that psychological well-being is impacted by intrinsic motivation mediated by enthusiasm and perseverance; it is also influenced by extrinsic motivation mediated by perseverance and reconciliation engagements. Perceived learning performance is affected by intrinsic motivation via enthusiasm and perseverance engagements, extrinsic motivation via perseverance and reconciliation engagement, and amotivation via reconciliation engagement. After enforcing online learning for more than a year, this study revealed that most respondents could adapt well to the teaching methods and master their classwork in online learning and agreed that there is an improvement in their academic performance in online learning.

Psychological well-being scores the lowest mean among all variables in descriptive analysis, excluding amotivation. The respondents of this study often but not always feel optimistic about the future, feel valuable and relaxed, and have clear minds, indicating that the students are facing challenges impacting their mental health and overall well-being. There could be various reasons, such as stress and anxiety related to their studies, social isolation, lack of support, or difficulty balancing their academic and personal responsibilities (Mofatteh, Citation2020). The tertiary institutions may provide resources and support for mental health, promote healthy coping strategies, and create a more supportive and inclusive learning environment. Additionally, tertiary institutions can encourage students to take care of their mental health by offering programs and activities that promote wellness, such as mindfulness classes.

Leong (Citation2022) reports an alarming situation as high as 72.1 % of Malaysian secondary school leavers were not motivated to further their studies and are more inclined to involve themselves in gig platforms. One reason is that they believe good academic performance does not necessarily guarantee a better job or income. This trend is worrying as it will create a shortage of high-skilled workforces and affect national growth in the long run. Schools can help foster intrinsic motivation and self-satisfaction in studies among teenagers, improving their academic performance and overall well-being by creating a supportive and engaging learning environment. Firstly, schools may provide autonomy opportunities for students to take control of their learning by allowing them to choose the topics they study, the projects they work on, and how they demonstrate their understanding of the material might foster motivation. The learning experience should be relevant to students’ lives and interests by incorporating real-world examples and problems and connecting the material to their future goals and aspirations. Helping students see the value and purpose of their studies by linking the material to critical societal issues and by highlighting the impact they can have in their communities and the world. Consequently, students should be encouraged to focus on their progress and growth by setting achievable goals, providing regular feedback, and recognizing their achievements. Encouraging active engagement and fostering positive relationships are also essential to promote a culture of respect, support, and inclusiveness.

6. Conclusions

This study examines tertiary students’ perceptions of academic motivation, engagement, psychological well-being, and perceived learning performance in online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Results from the primary data collected two years after the Movement Control Order (MCO) during the COVID-19 pandemic suggest that the students had become familiar with synchronous online learning. The research framework proposed in this study has moderate explanatory power to predict perceived learning performance (53.5%) and psychological well-being (41.5%). This study applied a quantitative approach and employed the disjoint two-stage approach of PLS-SEM for structural model validation. This study found that psychological engagement significantly influences perceived learning performance and well-being, with enthusiasm being the top predictor.

Additionally, academic motivation, particularly intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, predicted well-being through mediation by engagement in online learning environments. Furthermore, perceived learning performance is influenced by academic motivation, with mediation by psychological engagement (one or two dimensions of engagement) in online learning environments. Overall, this study contributes to understanding students’ learning performance and well-being in Malaysia’s tertiary education context. It can be a reference for tertiary institutions planning to embark in synchronous online teaching as part of their future strategies.

While the results of this study provide valuable insights into the online learning experiences of full-time tertiary students in Malaysia during the later phase of the COVID-19 pandemic, there are several limitations to consider. First, the study only examines synchronous online learning, and the findings might not be generalised to other online learning types and situations. Additionally, the study uses cross-sectional data, which limits its ability to measure the long-term effects of online learning on students’ academic performance and well-being. Furthermore, the data is based on self-report measures that are undoubtedly vital in assessing students’ emotions, feelings, and motivations towards learning; however, it is subject to memory distortions and may not fully capture the complexity of students’ experiences (Pekrun, Citation2020). As such, future research may incorporate qualitative data to validate the results further to overcome the shortcoming of self-report measures (Fabriz et al., Citation2021).

Given that online learning has become an increasingly prevalent mode of education during the pandemic, examining its impact on students’ perceived learning performance and psychological well-being is essential. Future research could explore the effectiveness of different online learning experiences, such as synchronous versus asynchronous approaches, and explore tertiary students’ resilience, coping mechanisms, and other psychological attributes related to psychological well-being and learning performance. One promising area of investigation is students’ psychological engagement, including enthusiasm, perseverance, and reconciliation, which could be studied through qualitative perspectives. Additionally, it would be valuable to investigate how students engage with online learning tools, such as ChatGPT and other collaborative, interactive, and visualisation tools.

Ethical clearance

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Multimedia University, Malaysia (EA0132022)

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Akin, A. (2008). The scales of psychological well-being: A study of validity and reliability. Educational Sciences: Theory and Practice, 8(3), 741–20. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ837765

- Al-Kumaim, N., Alhazmi, A., Mohammed, F., Gazem, N., Shabbir, M., & Fazea, Y. (2021). Exploring the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on university students’ learning life: An integrated conceptual motivational model for sustainable and healthy online learning. Sustainability, 13(5), 2546. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13052546

- Al-Salman, S., Haider, A. S., & Saed, H. (2022). The psychological impact of COVID-19’s e-learning digital tools on Jordanian university students’ well-being. The Journal of Mental Health Training, Education and Practice, 17(4), 342–354. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMHTEP-09-2021-0106

- Anthonysamy, L., Koo, A. C., & Hew, S.-H. (2019). Development and validation of an instrument to measure the effects of self-regulated learning strategies on online learning performance. Journal of Advanced Research in Dynamical & Control Systems, 11(10), 1093–1099. https://doi.org/10.5373/JARDCS/V11SP10/20192910

- Bailey, T. H., & Phillips, L. J. (2016). The influence of motivation and adaptation on students’ subjective well-being, meaning in life and academic performance. Higher Education Research & Development, 35(2), 201–216. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2015.1087474

- Boulton, C. A., Hughes, E., Kent, C., Smith, J. R., Williams, H. T. P., & Della Giusta, M. (2019). Student engagement and wellbeing over time at a higher education institution. PLoS ONE, 14(11), e0225770. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0225770

- Bowden, J. L.-H., Tickle, L., & Naumann, K. (2019). The four pillars of tertiary student engagement and success: A holistic measurement approach. Studies in Higher Education, 45(8), 1737–1745. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2019.1672647

- Chen, R., Liang, S., Peng, Y., Li, X., Chen, J., Tang, S., & Zhao, J. (2020). Mental health status and change in living rhythms among college students in China during the COVID-19 pandemic: A large-scale survey. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 137, 110219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2020.110219

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Erlbaum.

- Dandy, K. L., & Bendersky, K. (2014). Student and faculty beliefs about learning in higher education: Implications for teaching. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 26(3), 358–380. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1060843

- David, A. (2022, June 3). Micro-credentials portal to boost lifelong education. New Straits Times. https://www.nst.com.my/news/nation/2022/06/801960/micro-credentials-portal-boost-lifelong-education

- de Agrela Gonçalves Jardim, M., da Silva Junior, G., & Alves, M. (2017). Values in students of higher education. Creative Education, 8(10), 1682–1693. https://doi.org/10.4236/ce.2017.810114

- Fabriz, S., Mendzheritskaya, J., & Stehle, S. (2021). Impact of synchronous and asynchronous settings of online teaching and learning in higher education on students’ learning experience during COVID-19. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 733554. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.733554

- Free Malaysia Today. (2022, March 3). Over 17,000 dropped out of govt varsities last year, says minister. https://www.freemalaysiatoday.com/category/nation/2022/03/03/over-17000-dropped-out-of-govt-varsities-last-year-says-minister/

- Gillett-Swan, J. (2017). The challenges of online learning: Supporting and engaging the isolated learner. Journal of Learning Design, 10(1), 20. https://doi.org/10.5204/jld.v9i3.293

- Hair, J. F., Hult, T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). SAGE Publication, Inc.

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203

- Hamdan, K., & Amorri, A. (2022). The impact of online learning strategies on students’ academic performance. In Mahrul, M., & Shohel, C. (Eds.), E-Learning and digital education in the twenty-First century. IntechOpen. https://www.intechopen.com/chapters/74314

- Hartnett, M. (2016). The importance of motivation in online learning. In: motivation in online education. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-0700-2_2

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

- Hope, D., Davids, V., Bollington, L., & Maxwell, S. (2021). Candidates undertaking (invigilated) assessment online show no differences in performance compared to those undertaking assessment offline. Medical Teacher, 43(6), 646–650. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2021.1887467

- Hsu, H.-C. K., Wang, C. V., & Levesque-Bristol, C. (2019). Re-examining the impact of self-determination theory on learning outcomes in the online learning environment. Education and Information Technologies, 24, 2159–2174. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-019-09863-w3

- Huckins, J., da Silva, A., Wang, W., Hedlund, E., Rogers, C., Nepal, S., Wu, J., Obuchi, M., Murphy, E., Meyer, M., Wagner, D., Holtzheimer, P., & Campbell, A. (2020). Mental health and behavior of college students during the early phases of the COVID-19 pandemic: Longitudinal smartphone and ecological momentary assessment study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(6), e20185. https://doi.org/10.2196/20185

- Irfan, M., Shahudin, F., Hooper, V. J., Akram, W., & Abdul Ghani, R. B. (2021). The psychological impact of coronavirus on university students and its socio-Economic Determinants in Malaysia. Inquiry, 58, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1177/00469580211056217

- Kerzˇič, D., Alex, J. K., Pamela Balbontı´n Alvarado, R., Bezerra, D. D. S., Cheraghi, M., Dobrowolska, B., Aristovnik, M. E., França, T., González-Fernández, B., Gonzalez-Robledo, L. M., Inasius, F., Kar, S. K., Lazányi, K., Lazăr, F., Machin-Mastromatteo, J. D., Marôco, J., Marques, B. P., Mejía-Rodríguez, O., Méndez Prado, S. M., … Fagbamigbe, A. (2021). Academic student satisfaction and perceived performance in the elearning environment during the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence across ten countries. PLoS ONE, 16(10), e0258807. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0258807

- Kotera, Y., & Ting, S. H. (2021). Positive psychology of Malaysian university students: Impacts of engagement, motivation, self-Compassion, and well-being on mental health. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 19(1), 227–239. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-019-00169-z

- Kusurkar, R. A., Ten Cate, T. H. J., Van Asperen, M., & Croiset, G. (2011). Motivation as an independent and a dependent variable in medical education: A review of the literature. Medical Teacher, 33(5), e242–e262. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2011.558539

- Leong, A. (2022). 72% of spm graduates prefer to be influencers, E-Hailing drivers than pursuing higher education. The Rakyat Post . https://www.therakyatpost.com/news/2022/08/03/72-of-spm-graduates-prefer-to-be-influencers-e-hailing-drivers-than-pursuing-higher-education/

- Li, J., Ye, H., Tang, Y., Zhou, Z., & Hu, X. (2018). What are the effects of self-regulation phases and strategies for Chinese students? A meta-analysis of two decades research of the association between self-regulation and academic performance. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1–13. 9(DEC). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00001

- Martin, F., & Bolliger, D. U. (2018). Engagement matters: Student perceptions on the importance of engagement strategies in the online learning environment. Online Learning, 22(1). https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v22i1.1092

- Mental health Foundation. (no date). Children and young people: statistics. https://www.mentalhealth.org.uk/statistics/mental-health-statistics-children-and-young-people)

- Mofatteh, M. (2020). Risk factors associated with stress, anxiety, and depression among university undergraduate students. AIMS Public Health, 8(1), 36–65. https://doi.org/10.3934/publichealth.2021004

- Moodley, K., van Wyk, M., Robberts, A., & Wolff, E. (2022). Exploring the education experience in online Learning. International Journal of Education and Development Using Information and Communication Technology, 18(1), 146–163. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1345319

- Palansamy, Y. (2020). Higher education ministry: All university lectures to be online-only until end 2020, with a few exceptions. Malay Mail. https://www.malaymail.com/news/malaysia/2020/05/27/higher-education-ministry-all-university-lectures-to-be-online-only-until-e/1869975

- Patsali, M. E., Mousa, D.-P. V., Papadopoulou, E. V. K., Papadopoulou, K. K. K., Kaparounaki, C. K., Diakogiannis, I., & Fountoulakis, K. N. (2020). University students’ changes in mental health status and determinants of behavior during the COVID-19 lockdown in Greece. Psychiatry Research, 292, 113298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113298

- Pekrun, R. (2020). Self-Report is indispensable to assess students’ learning. Frontline Learning Research, 8(3), 185–193. https://doi.org/10.14786/flr.v8i3.637

- Peng, C. (2021). The academic motivation and engagement of students in English as a foreign language classes: Does teacher praise matter? Frontiers in Psychology, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.778174

- Rajabalee, Y. B., & Santally, M. I. (2020). Learner satisfaction, engagement and performances in an online module: Implications for institutional e-learning policy. Education and Information Technologies. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-020-10375-1

- Rimmer, S. (2020), Exploring online learning and student mental health, Association of Colleges. Accessed 25 November 2020. https://www.aoc.co.uk/exploring-online-learning-and-student-mental-health

- Ross, J. (2021). Universities shuttered across Malaysia as third covid wave hits. Times Higher Education. https://www.timeshighereducation.com/news/universities-shuttered-across-malaysia

- Saeed, S., & Zyngier, D. (2012). How motivation influences student engagement: A qualitative case study. Journal of Education and Learning, 1(2). https://doi.org/10.5539/jel.v1n2p252

- SchorlarLMS. (2020, September 24). The importance of engaging content in eLearning. https://www.scholarlms.com/the-importance-of-engaging-content-in-elearning/

- See, C. M., & Chuah, J. Y. (2015). Mental health and wellbeing of the undergraduate students in a research university: A Malaysian experience. Social Indicators Research, 122(2), 539–551. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-014-0704-9

- Soderstrom, N. C., & Bjork, R. A. (2015). Learning versus performance: An integrative review,Perspectives on Psychological Science,10(2), 176–199. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691615569000

- Statista. (2022, Nov 9). Number of students enrolled in public higher education institutions in Malaysia from 2012 to 2020, by gender. https://www.statista.com/statistics/794845/students-in-public-higher-education-institutions-by-gender-malaysia/

- Stewart-Brown, S., Tennant, A., Tennant, R., Platt, S., Parkinson, J., & Weich, S. (2009). Internal construct validity of the Warwick-Edinburgh mental well-being scale (WEMWBS): A rasch analysis using data from the Scottish health education population survey. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 1(7), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-7-15

- Sundarasen, S., Chinna, K., Kamaludin, K., Nurunnabi, M., Baloch, G. M., Khoshaim, H. B., Hossain, S. F. A., & Sukayt, A. (2020). Psychological Impact of COVID-19 and lockdown among university students in Malaysia: Implications and policy recommendations. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17, 6206. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17176206

- Trpcevska, L. (2017). Predictors of psychological well-being, academic self-efficacy and resilience in university students, and their impact on academic motivation. [PhD Dissertation, Victoria University]. Victoria University Eprints Repository. https://vuir.vu.edu.au/34676/

- Vallerand, R. J., Pelletier, L. G., Blais, M. R., Brie‘re, N. M., Sene´ Cal, C. B., & Vallie‘res, E. F. (1992). The Academic Motivation Scale: A measure of intrinsic, extrinsic, and amotivation in education. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 52(4), 1003–1019. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164492052004025

- Vayre, E., & Vonthron, A.-M. (2017). Psychological engagement of students in distance and online learning: Effects of self-Efficacy and psychosocial processes. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 55(2), 197–218. https://doi.org/10.1177/0735633116656849

- Vo, H. M., Zhu, C., & Diep, N. A. (2017). The effect of blended learning on student performance at course-level in higher education: A meta-analysis. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 53, 17–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2017.01.002

- Wang, Z., Yang, H., Yang, Y., Liu, D., Li, Z., Zhang, X., Zhang, Y., Shen, D., Chen, P., Song, W., Wang, X., Wu, X., Yang, X., & Mao, C. (2020). Prevalence of anxiety and depression symptom, and the demands for psychological knowledge and interventions in college students during COVID-19 epidemic: A large cross-sectional study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 275, 188–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.06.034

- Wilkinson, R. B., & Walford, W. A. (1998). The measurement of adolescent psychological health: One or two dimensions? Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 27(4), 443–455. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022848001938

- Zhu, C. (2012). Student satisfaction, performance, and knowledge construction in online collaborative learning. Educational Technology & Society, 15(1), 127–136. http://www.jstor.org/stable/jeductechsoci.15.1.127