Abstract

The aim of this research was to examine different variables as mediators of intrinsic motivation levels in a representative sample of 3049 Spanish students. The research design was quantitative, non-experimental, descriptive, cross-sectional and ex post facto, using as main instrument the Educational Motivation Scale-Short Form. Outcomes reveal greater levels of self-determined motivation in non-national students and found that intrinsically oriented goals favoured academic achievement. Likewise, educational centre type acted as a modulating factor, with higher motivation scores being found to exist at public centres. Finally, greater motivational development could be determined in vocational training compared to that seen in baccalaureate studies. Overall findings lead to the interpretation of important practical implications. The value attributed to the practical component of teaching and professional practice indicates that they represent key elements of professional training which favour motivation. Along these same lines, the more favourable motivation seen in foreign students suggests that certain sociocultural values characterise these individuals which place value on educational opportunities.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

Students motivation has become a recurring variable of interest in research studies in the ambit of education and training in recent decades. Although, the majority of these studies have considered it more as a modulating variable in relation to the development of student academic performance, skill improvement and learning outcomes (Wigfield et al., Citation2012). In other words, motivation is linked to a series of dependent variables or the expected outcome variables of these training processes, depending on the concept of education itself and the purpose attributed to it by different streams of thought and authors (Shane et al., Citation2003; Vansteenkiste et al., Citation2006).

Nonetheless, current conceptions of education consider motivation to be a complex construct in which multiple variables converge or on which they depend. These variables include personal development, self-esteem, self-concept, emotional intelligence (Abellán-Roselló, Citation2018; Usán & Salavera, Citation2018), cognitive and meta-cognitive skills applied to learning processes (Moreno et al., Citation2018), use of study techniques (Sandoval-Muñoz et al., Citation2018, Citation2018), and social relationships and integration in learning groups and communities (Rivas & Perero, Citation2018). Given this, relating student motivation with one single variable could be considered to give a limited perspective. For this reason, motivation should start to be considered as an educational value or desirable goal of education, with an influence that has been demonstrated beyond doubt on all of the aforementioned variables (Brunstein & Heckhausen, Citation2008; Hallam, Citation2009).

The concept of motivation is considered in the present research, in line with that proposed by Weiner (Citation2013), who establishes that motivation can be defined as the internal energy that a subject mobilizes to achieve an objective, which will depend on internal and external factors. These behaviours can have a positive intention, with the aim of obtaining some type of benefit. Alternatively, they can have negative consequences. Positive motivations of individuals towards the required actions or behaviours of formative processes are of special interest (Karlen et al., Citation2019).

Examination of the origin of motivation has covered diverse theories and approaches from different epistemological standpoints, although, in a general sense, Peters (Citation2015) points to four main theories which pertain to the behaviour resulting from motivation. Firstly, content theory proposes that motivation is linked to hierarchical needs and the need to satisfy them. Secondly, incentive theory proposes that motivation results from a certain stimulus, incentive or reinforcer which impacts upon a particular behaviour in a positive way. Thirdly, drive reduction theory argues that basic fundamental needs, such as those related to thirst or hunger, drive individual to perform actions to address them. Finally, cognitive dissonance theory manifests that individuals strive to reduce the dissonance they feel with the world around them, with this leading them to perform determined actions to this end (Dweck, Citation2017; Peters, Citation2015).

1.2. Motivation and self-determination theory (SDT)

In general, most research papers and manuals on the Self-Determination Theory in the psychological context address the scheme of the continuous line or “continuum”. This theory establishes that motivation in carrying out a task, action or behavior forms a continuous line, which varies depending on the level of self-determination (Castro-Sánchez et al., Citation2023; Deci & Ryan, Citation2012). In this way, in the most self-determined zone, intrinsic type motivations can be established, which are those in which the behavior is initiated, maintained or carried out for self-interest and the satisfaction generated (Roth et al., Citation2019). The middle zone of the model is defined by extrinsic motivations, which are characterized by the impulse of behavior in exchange for a reward or recognition (Deci & Ryan, Citation2008). This section can be broken down into four types of motivations, which also differ in level of self-determination. First, there are the integrated extrinsic motivations, which are characterized by being integrated into the lifestyle of the human being. Subsequently, the identified extrinsic motivations are observed, because when performing a task, the subject identifies with the benefits that it brings (Hayenga & Corpus, Citation2010; Ryan & Deci, Citation2000; Vansteenkiste et al., Citation2006).

Continuing with the intermediate zone of extrinsic motivation, in third place is introjected extrinsic motivation; in which the human being performs an activity to avoid a negative consequence or feeling. External extrinsic motivation represents the less self-determined motivation of the middle zone, being defined by those behaviors motivated by external rewards. Finally, amotivation will be found in the least self-determined area of the continuum, implying the absence of motivation (Cheng, Citation2019; Ryan & Deci, Citation2017). Thus, two main types of motivation are typically recognised. The first of these is intrinsic motivation, which is born out of the individual’s desire for need satisfaction and self-determination or independence when striving to achieve a reward. It places a high value on individual internal commitment for achieving goals proposed by the individual themselves. The second type of motivation is extrinsic. Here, the origin of the development of behaviours or actions induced by the group or environment is external. This type of motivation is weaker that those mentioned previously as it is not based on internal commitment.

It is, therefore, opportune to propose a study with the aim of analysing motivation, both internal and external, as an outcome variable in itself which is desirable for appropriate development of formative processes. Further, the present study will examine motivational development as a function of other typically considered variables in studies on academic performance and learning outcomes (Heckhausen & Heckhausen, Citation2008; Meece et al., Citation2006).

Based on the above, some current studies have shown the relationship between motivation and academic performance. In this sense, it has been shown how the psychological training of the adolescent student, determined through their effectiveness, resilience, optimism and hope, is positively associated with the three basic needs of motivation -the need for autonomy being the most decisive-, associating these two dimensions of directly with academic performance in various disciplines -mathematics, language, science or history- (Carmona-Halty et al., Citation2019). In a similar way, Lu et al. (Citation2017) also carried out a study on adolescents, also including parental control and academic self-concept. It was possible to show that an increase in the motivation was associated with an increase in self-concept, while parental control decreased self-concept and needs by subtracting autonomy and competence.

Currently, basic psychological needs have also been considered in higher education. It has been shown how these are associated with the emotional regulation capacity of Spanish university students, specifying how cognitive reappraisal is positively associated with the three needs, or how an increase in expressive suppression implies a decrease in the needs for competence or relationship (Chacón-Cuberos et al., Citation2019). Another example is the study developed by Karimi and Sotoodeh (Citation2019), which analyzes the effect of the three needs on the academic performance and the level of motivation of university students of agriculture. In this case, it was observed that the satisfaction of each of them favored both factors, with the need for autonomy being the most relevant for intrinsic motivation.

The present study establishes as a research problem the development of low levels of motivation in educational contexts, and especially, in those educational stages in which the transition to higher education or working life will occur. Specifically, motivation levels may fluctuate according to various factors, such as mother tongue, age, family climate, teaching methodology or student expectations (Heo & Han, Citation2018; Krou et al., Citation2021; Wypych et al., Citation2018). Therefore, the following research question is established: Is there a relationship between sociodemographic and academic factors and the motivation developed by young people in post-compulsory secondary education?

The aim of the present study is to examine levels of motivation in students undertaking post-compulsory secondary education and consider potential differences as a function of sociodemographic and academic factors. With regards to the former, gender, age and origin (nationals or foreigners in the process of reception or social integration in Spain) are considered. With regards to the latter, centre type and students’ educational stage or level are considered.

Based on all the above, two unilateral alternative hypotheses are established:

Hypothesis 1 (H1): Non-national students will have higher levels of intrinsic motivation, which will be mediated by their need for academic achievement to achieve a future job.

Hypothesis 2 (H2): Students in higher educational stages will have higher levels of intrinsic motivation, mediated by experiences closer to the professional world.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Design and participants

The present research follows a quantitative, descriptive and cross-sectional design. In the same way, it concerns an ex post-facto study that is univariate in nature given that it considers only educational motivation as a single dependent variable. The sample was made up of a total of 3049 students [♂ = 1407 (46.1%); ♀ = 1642 (53.9%)] undertaking post-compulsory non-university education in the autonomous region of Andalusia (Spain). Participants were aged between 15 and 58 years (M = 19.60; SD = 19.60). Specifically, the study sample was composed of 1850 students enrolled on vocational training ([VT] 60.7%) and 1199 baccalaureate students (39.3%) who were undertaking the aforementioned studies during the 2020/2021 academic year at public institutions.

When selecting the final study sample, the following inclusion criteria were applied: Eligible students must a) be enrolled on at least 60% of all modules to be delivered in in-person sessions; b) regularly attend classes pertaining to one of the educational stages being evaluated. On the other hand, participants were not considered eligible if they met one or more of the following exclusion criteria: a) Present with any pathology that impeded completion of the questionnaire; b) incorrectly complete any of the scales in a way that impeded correct analysis, this could refer to blank responses or marking multiple boxes instead of providing a single response. Finally, it serves to highlight that, according to the Andalusian Institute of Statistics and Cartography, 113,312 students were estimated to be undertaking vocational training (VT) during the 2020/2021 academic year, assuming a 1.4% margin of error for PQ = 0.90 and a confidence level of 95%. Likewise, the margin of error was 1.7% for PQ = 0.90 for students undertaking baccalaureate studies (n = 112,817), assuming the same confidence level.

2.2. Instruments

Educational motivation scale-short form, adapted by Expósito-López et al. (Citation2021) from the educational motivation questionnaire (EME) validated by Nuñez et al. (Citation2005) for use in compulsory secondary education. The short version of the scale is composed of a total of 19 items (e.g., 1. Because I need, at least, baccalaureate qualifications to find a well-paid job) which are rated along a seven-point Likert scale were 1 = “doesn’t correspond at all” and 7 = “totally corresponds”. This version of the scale comprises a total of four dimensions, with these determining different levels of motivation for undertaking vocational training or baccalaureate studies: Amotivation (items 4, 8, 12 and 17), externally regulated extrinsic motivation (items 1, 10 and 14), internally regulated extrinsic motivation (items 5, 6, 9, 13, 18 and 19) and intrinsic motivation (items 2, 3, 7, 11, 15 and 16). In the original study, internal consistency of the measure was established with α values of between 0.73 and 0.88. The short form of the measure produced α values of between 0.80 and 0.87, these being higher than the original values. In the present study, internal consistency of the overall scale was established as α = 0.83, this being adequate.

Ad hoc questionnaire for the recording of sociodemographic and academic variables. For this, nominal variables were employed to describe the following attributes: Sex (1 = male; 2 = female), nationality (1 = Spanish; 2 = other), academic year (1 = first; 2 = second), institution type (1 = public; 2 = mixed funding/private).

2.3. Procedure

The present research was derived from outcomes obtained from the R + D project referenced [Complete with the data of the R + D + i project described in the title page]. Further, the present research work received positive approval from the Ethics Committee of the University of [Anonymous] (reference: XXXX/CEIH/2020).

Data collection was performed at educational institutions delivering vocational training and baccalaureate studies in the eight provinces of the autonomous region of Andalusia during the 2020/2021 academic year. Firstly, directors of each institution were contacted via an information pack developed by the project’s principal researcher (PI). This pack contained a letter which provided details about the nature of the study, its objectives and the way in which data would be handled.

Once approval was received from directors of the institutions, the aforementioned questionnaires were administered in-person to participants. Data collections was performed at all times with the presence of a researcher assigned to the project, alongside the tutor responsible for each student group. This was done with the aim of ensuring the correct completion of scales and to resolve doubts. This process took place with total normality, applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria described above prior to administration and without any notable incidents.

Finally, it serves to indicate that student anonymity was guaranteed at all times by ensuring that scales were completed individually and anonymously, and respecting their right to confidentiality. It is also important to indicate that the present work complied with the ethical norms for research established by the Declaration of Helsinki (1975) and later updated in Brazil (2013).

2.4. Data analysis

Statistical analysis was performed via the program IBM SPSS® version 25.0. Basic descriptive analysis was performed according to frequencies and means, employing measures of dispersion (asymmetry and kurtosis) in order to check data normality in each employed scale. In order to determine statistically significant differences, t-test and one-way ANOVA analyses were used, depending on the nature of the variables under examination. Likewise, the Levene test was used to check the homogeneity of variance and Bonferroni provided the post-hoc test to determine between-group differences. A univariate linear model was developed, from which the percentage of explained variance and effect size of each variable was estimated via eta-squared. Finally, it is important to point out that internal consistency of the instruments was examined through the Cronbach alpha coefficient, with reliability indices being set at 95%.

3. Results

Table presents the general univariate linear model. This model examines intrinsic motivation as a dependent variable in students. Further, extrinsic-type motivations that are both externally and internally regulated are considered, whilst academic variables (academic year, nationality and studies) are included as factors. Firstly, it serves to highlight that the Levene equality of variances test produced a p-value of 0.142, meaning that the null hypothesis is accepted and equality of variance is assumed, in other words, the data is homogeneous. Likewise, the adjusted R2 values was 0.472, suggesting that 47% of total variance could be explained by the developed model. This can be considered to be acceptable, even more so in study fields linked to human behavioural sciences such as is the case in the present study which seeks to explain the development of motivation in young people.

Table 1. Univariate linear model-inter-individual effects

When analysing the significance and effect size associated with variables included in the model, significant outcomes were observed for both types of extrinsic motivation (p < 0.05), with the internally regulated form of extrinsic motivation being much more influential and producing a large effect size (µ2 = 0.408). With regards to factors, significant outcomes, although with a weak effect size, were observed for nationality (p < 0.05; µ2 = 0.003), with no independent relationships being found with regards to educational stage or type of institution. Nonetheless, the interaction between educational stage and institutional type was observed to be significant, as was the interaction between the three academic factors. In both cases, small effect sizes were shown (p < 0.05; µ2 = 0.004 y µ2 = 0.002, respectively; Table ).

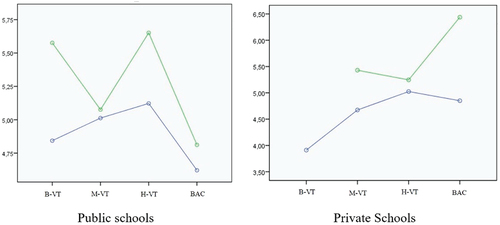

Table and Figure present descriptive data and, specifically, the mean differences between factors included in the model. Following review of the model intersections associated with significant outcomes, higher mean values can be observed for intrinsic motivation types at all educational stages in non-national students relative to Spanish students. Another relevant finding resides in the levels of motivation developed at the different motivational stages, specifically, motivation increases between educational stages with regards to vocational training, whilst the lowest motivational levels are seen in baccalaureate students. At private institutions, the same tendency is observed in national students, with motivation increasing as educational stage increases in non-national students.

Figure 1. Caption-Estimated marginal means according to nationality, educational stage and institutional type

Table 2. Descriptive statistics pertaining to the linear model

4. Discussion

The study of educational motivation has acquired great weight in the international scientific literature, especially in relation to post-compulsory educational stages. Amongst other reasons for this, these stages mark the point at which adolescence comes to an end and adulthood begins, making it a turning at which future work skill development is established to enable effective insertion of the young person into the workplace (Bandaranaike, Citation2018; Chacón-Cuberos et al., Citation2021). In this sense, analysis of the factors behind the development of self-determined motivations is of vital importance as this motivation will act as a protective factor against school dropout, ensuring appropriate academic performance and job opportunities in young people. The present study aimed to analyse the way in which diverse academic and social factors, such as institutional type, educational stage or place of origin, influence the motivational development of young people enrolled on vocational training or baccalaureate courses. Some of the studies conducted along similar lines and to have laid the foundations for the present work include those conducted by Alonso-Tapia and Simón (Citation2012), Dickson et al. (Citation2018), Expósito-López et al. (Citation2021), and Lesjak et al. (Citation2015), and Rodríguez-Esteban and Vidal (Citation2020).

With regards to the educational stage being undertaken by the student, the linear model determined that non-national students had higher levels of intrinsic motivation at all stages relative to national students. This finding is of great relevance and deserves to be analysed and placed into context. Concretely, some authors report greater academic failure in young people who come from other countries, especially, at earlier stages (Wiseman, Citation2012). The existence of certain barriers for non-national students can be assumed, such as having to master the local language or being presented with highly complex socioeconomic situations following a change of country (Baklashova & Kazakov, Citation2016). Indeed, Kazakova and Shastina (Citation2019) add to these issues, a reduced sense of home and incapacity to adapt themselves to new routines or feel secure. Nonetheless, at later educational stages, these students develop greater intrinsic mechanisms which are, especially, linked to goal achievement satisfaction, vocation or the development of mastery-oriented climates (Alonso-Tapia & Simón, Citation2012; Chue & Nie, Citation2016; González-Benito et al., Citation2021). Generally speaking, foreign students, who in the present sample came from socially unfavourable settings and were undergoing a process of social integration, possessed more transcendental perspectives towards education. Seeing it as an avenue towards potential life change. In contrast, Kazakova and Shastina (Citation2019) established that the fulfilment of obligations, achievement of parental expectations and being granted access to a recognised university acted as conditioners of motivation in local students. All of these aspects adhere to extrinsic mechanisms, whether internally or externally regulated, which confer education with a positive value but as an assumed right that can be taken advantage of at any time (Treviño-Villarreal & González-Medina, Citation2022).

In consideration of the type of educational institution at which courses were being undertaken, a general trend could be observed towards an increase in intrinsic motivation with the level of vocational training at public institutions. Nonetheless, motivational levels dropped in the case of baccalaureate courses, particularly amongst national students. These premises may be explained by the characteristics of the training curriculum themselves at these two stages. In Spain, higher and intermediate level vocational training exceeds 240 hours of professional practice, whilst, at the basic level, around 150 hours are dedicated to such activities (Navas et al., Citation2021). In contrast, there is a total absence of teaching time dedicated to professional practice in baccalaureate courses, with this being a factor that could act to decrease levels of intrinsic motivation. VT students get a glimpse of a professional future that is heavily oriented towards their studies and closer in time, whilst their baccalaureate counterparts who are still undergoing highly general training processes, must still experience a long process of university degree and/or postgraduate training, in some cases, with much longer timeframes (Acosta et al., Citation2019). Indeed, Van Harsel et al. (Citation2020) argued that some students who engage in vicarious learning, or have the opportunity to go out into the world during their learning process (Olmos & Más, Citation2017), develop goals that are more in line with reality, more vocational and more internally directed.

In exchange, intrinsic motivation was shown to increase between stages at private institutions, with far less difference emerging between baccalaureate and VT students. This being said, national students are less motivated, showing the same trend as that presented above. With regards to the aforementioned, it could be concluded that baccalaureate students at private institutions reach higher levels of motivation due to the characteristics of the institution itself, and teaching approaches and methods (Rodríguez et al., Citation2019). Firstly, private institutions have a much lower group-class ratio. This allows for more personalised attention and better follow-up of student learning processes, leading to better performance and lower dropout (Arufe-Giráldez et al., Citation2017; Llera & Pérez, Citation2012). Further, many institutions under private ownership have agreements with universities which could facilitate access to these same universities, favouring identified or introjected motivations in baccalaureate students (Ghanizadeh & Rostami, Citation2015). Finally, the student profile of students at these educational institutions comprises greater levels of attention from teachers (with the teaching body also being subjected to greater control), families with higher financial incomes and socio-cultural levels, and greater supply of didactic and technological resources at the institution (Fack & Grenet, Citation2010; Kim et al., Citation2018).

In line with that presented, moderate levels of motivation at public institutions were higher than at private institutions, with less variability and a smaller standard deviation. This leads to the conclusion that levels of intrinsic motivation at publicly owned institutions, in addition to being generally higher, tend to stay more constant and homogenous over time. Macebón et al. (Citation2012) concluded from data obtained from PISA reports that public institutions are more effective than private ones. These findings may be explained by higher levels of intrinsic motivation, this being associated with reduced dropout, greater self-efficacy and better academic performance (Gu et al., Citation2017; Liu et al., Citation2020). In a similar sense, it could be established that, at public institutions, motivational climates more oriented towards mastery could be developed, in contrast to other motivational types which are more linked to performance or ego and can reinforce extrinsic goals (Kim, Citation2021; Randall et al., Citation2019).

It should also be indicated that both internally regulated and externally regulated extrinsic motivations held a specific relationship with intrinsic motivations, with stronger relationships emerging in the case of the former. In explanation of these findings, Diseth et al. (Citation2020) established that young peoples’ academic performance mainly correlates with self-determined motivational types, although certain dimensions of extrinsic motivational types were also correlated with performance. In the case of the latter, the difficulty of the work to be performed, dependence and teacher rewards should be considered. Some previous research works have also demonstrated that motivation has a multi-factor component. It is determined by a sum of factors characterised by different degrees of self-determination, making consideration of these factors essential in the design of any type of educational action (Gu et al., Citation2017; Ryan & Deci, Citation2020).

As main conclusions, it should be noted that hypothesis 1 must be accepted, since the national students were those who presented lower levels of intrinsic motivation. This can be justified by the greater need of the non-national student to find educational opportunities, access scholarships and find a good job. Second, hypothesis 2 is rejected, since high school students presented lower levels of intrinsic motivation. This premise is justified by the greater practical and experiential component that professional training has in Spain, generating higher levels of motivation. In addition, it should be noted that, on average, the levels of intrinsic motivation were higher in public schools, with less homogeneous data being found in private schools.

Finally, it is essential to mention some of the main limitations of the present research work. The sample was highly representative; however, it was not homogeneously distributed with regards to the different strata examined. Thus, it would be of interest to carry out random stratified sampling with the aim of addressing this limitation. It would also be useful to include further additional variables alongside the analysed dependent variables in order to favour understanding of the phenomenon. Some of the most interesting of these potential extra variables include academic performance, family functioning and the length of time the student has been within the educational system. In conclusion, limitations implicit to the design methodology employed should also be highlighted. A descriptive and cross-sectional approach was taken which is highly effective for identifying the state of the issue but impedes causal relationships between variables of interest from being uncovered.

Two relevant practical implications at the educational level can be highlighted based on the reported findings. First, it was observed that the level of intrinsic motivation decreased in baccalaureate with respect to professional training. Among other reasons, this may be due to the characteristics of this educational stage, since in baccalaureate there are no professional practices. For this reason, it is of vital importance that students can have contact with the labor market and the professional activity for which they are being trained. In this way, they could acquire many abilities and skills in a real, contextualized and professional way, improving the educational experience and their intrinsic motivation. Another practical implication lies in the lower levels of motivation shown by students of Spanish origin. It is essential that a diagnosis of the reasons associated with these lower levels of self-determination be carried out, so that actions can be put into practice that help improve it, and therefore, enhance academic performance and avoid school dropout.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abellán-Roselló, L. (2018). Motivación escolar y aprendizaje en la Educación Secundaria Obligatoria. Ciencia & futuro, 8(2), 111–12.

- Acosta, J. L. B., Navarro, S. M. B., Gesa, R. F., & Kinshuk, K. (2019). Framework for designing motivational augmented reality applications in vocational education and training. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 35(3), 102–117. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.4182

- Alonso-Tapia, J., & Simón, C. (2012). Differences between immigrant and national students in motivational variables and classroom-motivational-climate perception. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 15(1), 61–74. https://doi.org/10.5209/rev_sjop.2012.v15.n1.37284

- Arufe-Giráldez, V., Chacón-Cuberos, R., Zurita-Ortega, F., Lara-Sánchez, A., & Castro-García, D. (2017). Influencia del tipo de centro en la práctica deportiva y las actividades de tiempo libre de escolares. Revista Electrónica Educare, 21(1), 105–123. https://doi.org/10.15359/ree.21-1.6

- Baklashova, T. A., & Kazakov, A. V. (2016). Challenges of International Students’ Adjustment to a Higher Education Institution. International Journal of Environmental and Science Education, 11(8), 1821–1832. https://doi.org/10.12973/ijese.2016.557a

- Bandaranaike, S. (2018). From research skill development to work skill development. Journal of University Teaching & Learning Practice, 15(4), 7. https://doi.org/10.53761/1.15.4.7

- Brunstein, J. C., & Heckhausen, H. (2008). Achievement motivation. In Motivation and action (pp. 221–304). Springer Link.

- Carmona-Halty, M., Schaufeli, W. B., Llorens, S., & Salanova, M. (2019). Satisfaction of basic psychological needs leads to better academic performance via increased psychological capital: A Three-wave longitudinal study among high school students. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 2113. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02113

- Castro-Sánchez, M., Cuberos-Gámiz, E., Lara-Sánchez, A. J., & García-Mármol, E. (2023). Basic psychological needs according to academic and healthy factors in adolescents from Granada. Journal of Sport and Health Research, 15(1), 87–96. https://doi.org/10.58727/jshr.98642

- Chacón-Cuberos, R., Expósito-López, J., de la Guardia, J. J. R. D., & Olmedo-Moreno, E. M. (2021). Skills for Future Work (H2030): Multigroup Analysis in Professional and Baccalaureate Training. Research on Social Work Practice, 31(7), 758–769. https://doi.org/10.1177/10497315211002646

- Chacón-Cuberos, R., Olmedo-Moreno, E. M., Lara-Sánchez, A. J., Zurita-Ortega, F., & Castro-Sánchez, M. (2019). Basic psychological needs, emotional regulation and academic stress in university students: A structural model according to branch of knowledge. Studies in Higher Education, 46(7), 1421–1435. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2019.1686610

- Cheng, W. (2019). How intrinsic and extrinsic motivations function among college student samples in both Taiwan and the US. Educational Psychology, 39(4), 430–447. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2018.1510116

- Chue, K. L., & Nie, Y. (2016). International students’ motivation and learning approach: A comparison with local students. Journal of International Students, 6(3), 678–699. https://doi.org/10.32674/jis.v6i3.349

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2008). Self-determination theory: A macrotheory of human motivation, development, and health. Canadian Psychology, 49(3), 182–185. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012801

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2012). Self-determination theory. In P. A. M. Van Lange, A. W. Kruglanski, & E. T. Higgins (Eds.), Handbook of theories of social psychology (pp. 416–436). Sage Publications Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446249215.n21

- Dickson, A., Perry, L. B., & Ledger, S. (2018). Impacts of International Baccalaureate programmes on teaching and learning: A review of the literature. Journal of Research in International Education, 17(3), 240–261. https://doi.org/10.1177/1475240918815801

- Diseth, Å., Mathisen, F. K. S., & Samdal, O. (2020). A comparison of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation among lower and upper secondary school students. Educational Psychology, 40(8), 961–980. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2020.1778640

- Dweck, C. S. (2017). From needs to goals and representations: Foundations for a unified theory of motivation, personality, and development. Psychological Review, 124(6), 689–719. https://doi.org/10.1037/rev0000082

- Expósito-López, J., Romero-Díaz de la Guardia, J., Olmedo-Moreno, E. M., PistónRodríguez, M. D., & Chacon-Cuberos R. (2021). Adaptation of the educational motivation scale into a short form with multigroup analysis in a vocational training and baccalaureate setting. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 1682. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.663834

- Fack, G., & Grenet, J. (2010). When do better schools raise housing prices? Evidence from Paris public and private schools. Journal of Public Economics, 94(1–2), 59–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2009.10.009

- Ghanizadeh, A., & Rostami, S. (2015). A Dörnyei-inspired study on second language motivation: A cross-comparison analysis in public and private contexts. Psychological Studies, 60(3), 292–301. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12646-015-0328-4

- González-Benito, A., López-Martín, E., Expósito-Casas, E., & Moreno-González, E. (2021). The relationship of student academic motivation and perceived self-efficacy with academic performance in distance learning university students. RELIEVE, 27(2), 2. http://doi.org/10.30827/relieve.v27i2.21909

- Gu, J., He, C., & Liu, H. (2017). Supervisory styles and graduate student creativity: The mediating roles of creative self-efficacy and intrinsic motivation. Studies in Higher Education, 42(4), 721–742. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2015.1072149

- Hallam, S. (2009). Motivation to learn. In The Oxford handbook of music psychology (pp. 285–294). Oxford University Press.

- Hayenga, A. O., & Corpus, J. H. (2010). Profiles of intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: A person-centered approach to motivation and achievement in middle school. Motivation and Emotion, 34(4), 371–383. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-010-9181-x

- Heckhausen, J. E., & Heckhausen, H. E. (2008). Motivation and action. Cambridge University Press.

- Heo, J., & Han, S. (2018). Effects of motivation, academic stress and age in predicting self-directed learning readiness (SDLR): Focused on online college students. Education and Information Technologies, 23(1), 61–71. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-017-9585-2

- Karimi, S., & Sotoodeh, B. (2019). The mediating role of intrinsic motivation in the relationship between basic psychological needs satisfaction and academic engagement in agriculture students. Teaching in Higher Education, 25(8), 959–975. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2019.1623775

- Karlen, Y., Suter, F., Hirt, C., & Merki, K. M. (2019). The role of implicit theories in students’ grit, achievement goals, intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, and achievement in the context of a long-term challenging task. Learning and Individual Differences, 74, 101757. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2019.101757

- Kazakova, J. K., & Shastina, E. M. (2019). The impact of socio-cultural differences on formation of intrinsic motivation: The case of local and foreign students. Learning and Motivation, 65, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lmot.2018.10.001

- Kim, S. (2021). Education and public service motivation: A longitudinal study of high school graduates. Public Administration Review, 81(2), 260–272. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.13262

- Kim, Y., Joo, H. J., & Lee, S. (2018). School factors related to high school dropout. KEDI Journal of Educational Policy, 15(1), 59–79.

- Krou, M. R., Fong, C. J., & Hoff, M. A. (2021). Achievement motivation and academic dishonesty: A meta-analytic investigation. Educational Psychology Review, 33(2), 427–458. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-020-09557-7

- Lesjak, M., Juvan, E., Ineson, E. M., Yap, M. H., & Axelsson, E. P. (2015). Erasmus student motivation: Why and where to go? Higher Education, 70(5), 845–865. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-015-9871-0

- Liu, Y., Hau, K. T., Liu, H., Wu, J., Wang, X., & Zheng, X. (2020). Multiplicative effect of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation on academic performance: A longitudinal study of Chinese students. Journal of Personality, 88(3), 584–595. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12512

- Llera, R. F., & Pérez, M. M. (2012). Colegios concertados y selección de escuela en España: Un círculo vicioso. Presupuesto y Gasto público, 67, 97–118.

- Lu, M., Walsh, K., White, S., & Shield, P. (2017). The associations between perceived maternal psychological control and academic performance and academic self-concept in Chinese adolescents: The mediating role of basic psychological needs. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 26(5), 1285–1297. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-016-0651-y

- Mancebón, M. J., Calero, J., Choi, Á., & Ximénez-de-Embún, D. P. (2012). The efficiency of public and publicly subsidized high schools in Spain: Evidence from PISA-2006. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 63(11), 1516–1533 .

- Meece, J. L., Glienke, B. B., & Burg, S. (2006). Gender and motivation. Journal of School Psychology, 44(5), 351–373. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2006.04.004

- Moreno, A. E., Rodríguez, J. V. R., & Rodríguez, I. R. (2018). La importancia de la emoción en el aprendizaje: Propuestas para mejorar la motivación de los estudiantes. Cuaderno de pedagogía universitaria, 15(29), 3–11. https://doi.org/10.29197/cpu.v15i29.296

- Navas, A. A., Abiétar, M., Bernad, J. C., Córdoba, A. I., Giménez, E., & Meri, E. (2021). Implicación del estudiantado en Formación Profesional: Análisis diferencial en la provincia de Valencia. Revista de Educación, 394. https://doi.org/10.7203/puv-oa-329-5

- Núñez, J. L., Martín-Albo Lucas, J., & Navarro, J. G. (2005). Validación de la versión española de la echelle de motivation en education. Psicothema, 17, 344–349. https://doi.org/10.1174/021093910790744590

- Olmos, P., & Mas, O. (2017). Perspectiva de tutores y de empresas sobre el desarrollo de las competencias básicas de empleabilidad en el marco de los programas de formación profesional básica. Educar, 53(2), 0261–284. https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/educar.870

- Peters, R. S. (2015). The Concept of Motivation. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315712833

- Randall, E. T., Shapiro, J. B., Smith, K. R., Jervis, K. N., & Logan, D. E. (2019). Under pressure to perform: Impact of academic goal orientation, school motivational climate, and school engagement on pain and somatic symptoms in adolescents. The Clinical Journal of Pain, 35(12), 967–974. https://doi.org/10.1097/ajp.0000000000000765

- Rivas, H. C. P., & Perero, S. G. V. (2018). Motivación laboral. Elemento fundamental en el éxito organizacional. Revista Scientific, 3(7), 177–192. https://doi.org/10.29394/scientific.2542-2987.2018.3.7.9.177-192

- Rodríguez, L. J., Areces, D., Suárez, J., Cueli, M., & Muñiz, J. (2019). Qué motivos tienen los estudiantes de Bachillerato para elegir una carrera universitaria? Journal of Psychology and Education, 14(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.23923/rpye2019.01.167

- Rodríguez-Esteban, A., & Vidal, J. (2020). Influence of educational factors on the education-job match in men and women. RELIEVE, 26(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.7203/relieve.26.1.16499

- Roth, G., Vansteenkiste, M., & Ryan, R. M. (2019). Integrative emotion regulation: Process and development from a self-determination theory perspective. Development and Psychopathology, 31(3), 945–956. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0954579419000403

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. Guilford Publications. https://doi.org/10.1521/978.14625/28806

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2020). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation from a self-determination theory perspective: Definitions, theory, practices, and future directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 61, 101860. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2020.101860

- Sandoval-Muñoz, M. J., Mayorga-Muñoz, C. J., Elgueta-Sepúlveda, H. E., Soto-Higuera, A. I., Viveros-Lopomo, J., & Riquelme Sandoval, S. V. (2018). Compromiso y motivación escolar: Una discusión conceptual. Revista educación, 42(2), 66–79. https://doi.org/10.15517/revedu.v42i2.23471

- Shane, S., Locke, E. A., & Collins, C. J. (2003). Entrepreneurial motivation. Human Resource Management Review, 13(2), 257–279. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1053-4822(03)

- Treviño-Villarreal, D. C., & González-Medina, M. A. (2022). Parental involvement and educational achievement: A consideration of this relationship in baccalaureate students. RELIEVE, 28(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.30827/relieve.v28i1.23786

- Usán, P., & Salavera, C. (2018). Motivación escolar, inteligencia emocional y rendimiento académico en estudiantes de educación secundaria obligatoria. Actualidades en Psicología, 32(125), 95–112. https://doi.org/10.15517/ap.v32i125.32123

- van Harsel, M., Hoogerheide, V., Verkoeijen, P., & van Gog, T. (2020). Examples, practice problems, or both? Effects on motivation and learning in shorter and longer sequences. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 34(4), 793–812. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.3649

- Vansteenkiste, M., Lens, W., & Deci, E. L. (2006). Intrinsic versus extrinsic goal contents in self-determination theory: Another look at the quality of academic motivation. Educational Psychologist, 41(1), 19–31. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep4101_4

- Weiner, B. (2013). Human motivation. Psychology Press.

- Wigfield, A., Cambria, J., & Eccles, J. S. (2012). Motivation in education. The Oxford Handbook of Human Motivation, 463–478. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195399820.013.0026

- Wigfield, A., Eccles, J. S., Schiefele, U., Roeser, R. W., & Davis-Kean, P. (2006). Development of achievement motivation. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 10.1002/9780470147658.chpsy0315

- Wiseman, A. W. (2012). The impact of student poverty on science teaching and learning: A cross-national comparison of the South African case. American Behavioral Scientist, 56(7), 941–960. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764211408861

- Wypych, M., Matuszewski, J., & Dragan, W. Ł. (2018). Roles of impulsivity, motivation, and emotion regulation in procrastination–path analysis and comparison between students and non-students. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 891. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00891