Abstract

The aim of the study is to access the effect of Information and Communication Technology (ICT) usage on Second Cycle Schools (SCSs) student academic performance and its associated challenges in a developing country. To give teachers and students the chance to function in the information age, ICT integration in teaching and learning activities is essential. This study employed a mix method approach to access the effect of ICT usage on SCSs student academic performance and its associated challenges in Ghana. The respondents of this study were chosen using the Yamane formula. A total of one hundred and seventy-two (172) respondents were chosen for this study. Questionnaire and interview guide was used as data collection tool in this study. The study found that the majority of students use mobile phones, computers, the internet/modem, social media, digital cameras, or printers outside of school. The findings again indicated that, ICT usage has improved students’ academic performance. The findings further revealed that students face challenges when using ICT facilities in their learning processes due to limited access to internet connections and the attitude of some teachers when integrating ICT in class. The availability of ICT resources at SCSs and sometimes homes are critical to the success of ICT in SCS education. The study then recommends that parents should make an effort to provide ICT resources for their children. Furthermore, governments of developing countries should make sufficient funds available for providing universal access to ICT to unserved and underprivileged groups.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

The new global economy will have the ability to quickly change society with the use of information and technology. Over the past 10 years, ICT has developed and changed so swiftly that underdeveloped countries have struggled to keep up with the revolution and have lagged behind in communication with wealthier nations. Because it is the foundation of the modern world, understanding ICT and its core concepts is seen as being at the core of education. Technology has the power to revolutionize teaching strategies, classroom settings, and the duties of both students and teachers. Educational institutions can employ ICT to equip students with the knowledge and skills they need for the twenty-first century. As a result, more people throughout the world will have access to education, educational equity, broadcasting of excellent teaching and learning programs, teacher professional development, and the capacity to administer education more successfully will all rise. The three primary difficulties in education—accessibility, inclusion, and standard—can therefore be easily handled by ICT.

1 Introduction

Information and communication technology (ICT) refers to the hardware, software, network, and media components that enable the collection, transport, and processing of data (Hu et al., Citation2018). Information processing, manipulation, and communication are often referred to as ICT. Using these technologies means using social networking sites like Facebook and WhatsApp as well as video-sharing services like YouTube. Projectors, desktops, and printers are also used in communication in addition to computers (Hu et al., Citation2018). The combination of ICT in tuition and learning organizations includes all of these technologies and their application in the handling of Information for educational purposes. Without a doubt, student academic performance is heavily influenced by access to Information. Students now have more information sources. According to Mathivanan et al. (Citation2021), ICT expands communication opportunities within and beyond educational institutions, allowing students, including those underserved by the formal education system, to access new learning opportunities. Being a part of the information society, according to Alderete and Formichella (Citation2016), entails having access to new technologies as well as learning how to use these technologies. This is because ICT is a factor in promoting inclusive practices in an educational system (Furlong & Davies, Citation2012).

ICT has been introduced in schools in advanced states and has improved academic achievement strategies as well as transformed teaching and learning processes (Clark, Citation2015). Others have also concentrated on schools’ attitudes toward effective ICT integration (Ghavifekr & Rosdy, Citation2015). Several studies have been carried out on the influence of these technologies on academic routine (Lau, Citation2017). Using ICT in education, according to research, improves academic performance and students’ attitudes toward academic work (Alderete & Formichella, Citation2016). ICTs have been recognized as critical tools in the delivery of high-quality education. Many countries, including Ghana, have taken significant steps to support the potential of ICTs in the development of a workforce capable of fully participating in a knowledge and information society. As a result, the Ghanaian state, through the Ministry of Education (MoE), implemented ICT in educational policies, ensuring that ICT is taught and studied at all stages of education in Ghana.

The policy is currently being implemented in all primary, secondary and tertiary levels of education across the country. It should be noted, however, that the availability of ICT facilities both within and outside of schools has a substantial influence on the successful implementation of the teaching and learning policy. Consequently, several studies in the field of ICT have been conducted. Bhattacharjee and Deb (Citation2016) focused on the role of ICT in tuition and learning, whereas Gil-Flores et al. (Citation2017) focused on school access to ICT infrastructure. According to Adarkwah (Citation2021), ICT facilitates and accelerates teaching. Without undermining the authors’ efforts, arguably, only a few studies have examined the influence of ICT use on students’ academic routine. This study, therefore, seeks to access the effect of ICT usage on Second Cycle Schools (SCSs) student academic performance and its associated challenges in a emerging country. The study focused on the Jirapa Senior High School (SHS) to offer solutions to the following research questions:

RQ1: What are the available ICT tools and what factors influence the Use of ICT in Second Cycle Schools?

RQ2: What are the effects of ICT usage on Second Cycle Schools students’ academic performance and its associated challenges?

This study is of three significance: The outcomes of the study and its recommendations will be useful to teachers, parents, policymakers, and educational planners in developing future ICT in education strategies. The research will also aid as a source of reference for other studies on the subject, thereby improving the long-term quality of future research. Furthermore, the study will add to existing knowledge, assisting in closing the gap between the benefits of ICT and their effects on student routine.

This study is organized as follows. Part 2 presents the study framework as well as a comprehensive evaluation of the literature. The study’s methodology, research strategy, sample design, data collection strategy, and analytical approach are covered in Section 3. In Section 4, the outcomes and a discussion of the conclusions were expanded upon. Section 5 contains the study’s conclusion, along with its implications, restrictions, and suggestions for additional research.

2. Literature review

This section provides a summary of the related literature.

2.1. Related literature

In order to reconcile research findings and report for multiple confounds, Skryabin et al. (Citation2015) evaluated data from extensive international databases gathered from 43 states to look at how a student’s Use of ICT affects their accomplishment in pursuing, mathematics, and science. Indicators of academic success that are strongly influenced by family finances include better parental participation, household education levels, and children’ access to smaller class sizes (Barger et al., Citation2019; Tucker-Drob & Bates, Citation2016). The expense of ICT gadgets suggests that it would be difficult to distinguish the academic influence of the two elements, and as a result, socioeconomic position has repeatedly been found to be a valid determinant of academic achievement. The outcomes of Skryabin et al. (Citation2015) revealed that, after taking socioeconomic status and gender into account, a student’s performance in reading and mathematics was positively impacted by how frequently they used ICT for school-related tasks. It is interesting to note that the study also discovered a positive link between a student’s ability to read and their Use of ICT, even for entertainment.

A growing body of evidence exists concerning how ICT affects academic performance in developing countries (Avgerou, Citation2010; Heeks, Citation2010, 2014; Walsham, Citation2017). A student’s general ICT competence is crucial in how they utilize technology. Despite significant moral concerns about students’ increased use of technology, an empirical study by Karamti (Citation2016), who studied the impact of ICT on academic performance in Tunisia, found that Tunisian parents primarily value the importance of ICT to their children’s academic performance.

Al-Ansi et al. (Citation2019) also investigated how information and communication technology (ICT) affected various learning environments in poor nations. They said that information and communication technologies have transformed conventional learning methods into contemporary, interactive settings. They learned once more that ICTs are the driving force behind the educational transformation. ICT has a favorable and considerable influence on high school learning. Except for the devices and tools of ICT, which were negative at the undergraduate level and insignificant at both levels, ICT factors have a positive and significant impact on the learning process at the undergraduate and postgraduate levels.

This affirms that ICT and academic performance are pressing phenomena under study in developing countries. Moreover, according to Emeka and Nyeche (Citation2016), Nigerian families believe that their children’s future performance in school and the workforce is critical to their development of ICT literacy. These data imply that families accept and support the growing use of ICT for educational reasons, notwithstanding some reservations.

The achievement of effective facilitation of student communication, teamwork, and good learning attitudes is attributed to e-learning, according to Rakhyoot (Citation2017) who researched institutional and individual hurdles of e-learning adoption in higher education in Oman, academics’ viewpoints. Also, it was found that online learning is positively connected with better academic performance in a study by Darkwa and Antwi (Citation2021) titled “From Classroom to Online: Comparing the Effectiveness and Student Academic Performance of Classroom Learning and Online Learning in Ghana.”.

A study by Lee and Wu (Citation2012) on the impact of individual differences in the inner and outer states of ICT on participation in online reading activities and PISA 2009 reading literacy found the following: Examining the connection between traditional and digital literacy, it was argued that effective ICT use gives students more control over their education and promotes cognitive processes that are good for helping them develop learning skills like self-assurance, communication, critical thinking, and problem-solving. In order to quantify these effects in Swedish primary school pupils, Genlott and Grönlund (Citation2016) compared the academic outcomes of students with varied degrees of access to an e-learning platform. They discovered that those who used the collaborative functions had this effect much more visibly and those with better platform accessibility indicated greater academic performance. This backs up Y. H. Lee and Wu’s (Citation2012) study, which shown that e-learning techniques can improve learning abilities in general and even more so when ICT is specifically utilized to foster cooperation.

Within the framework of academic learning, the impact of a child’s everyday interactions with technology has grown in importance as a research area, demonstrating the intrinsic learning capacity of ICT use.

Furlong and Davies (Citation2012) conduct a substantial mixed-methods reading that employs in-depth qualitative analysis to provide persuasive evidence for the benefits of ICT use environments in United Kingdom. According to Furlong and Davies’ theory, quasi-formal and incidental learning, such as studying while having fun and unwinding, have replaced the previous categories of formal and informal learning, like schoolwork and homework. As a result of incorporating digital knowledge into daily living, this tends to suggest that children are continuously learning through their daily encounters with technology rather than merely through concentrated and scheduled work at school. This claim that continued digital learning improves student progress in reading, mathematics, and science is supported by research by Skryabin et al. (Citation2015) who used data from 120 countries, including developing nations like Ghavifekr and Rosdy (Citation2015). This phenomena, according to Furlong and Davies (Citation2012), is a blurring of the lines between home and school. They further contend that this is because ICT literacy abilities are predominantly gained at home. This shows that using ICT may improve a student’s overall capacity for learning, including leisure pursuits like social networking and web browsing (Wittwer & Senkbeil, Citation2008; Lee & Wu, Citation2013).

The relevance of the context and connections of a student’s ICT use is typically disregarded or treated as a minor issue in prior studies. Wittwer and Senkbeil (Citation2008) examined 4,660 German pupils and found that neither access to or Use of a computer had any bearing on a student’s performance on a mathematics test, illuminating the intricacy of the relationship. The fact that pupils who used computers independently displayed greater problem-solving skills lends weight to the hypothesis that improved ICT use may be a moderating feature for overall academic achievement. Hu et al. (Citation2018) revealed in a substantial global study that utilizing ICT for school was linked with lower routine in science, reading, arithmetic, and literacy. The authors hypothesized that ICT acts as a source of distraction through social and digital media as a result of this results.

However, they do not consider the whole context of e-learning as defined by Rakhyoot (Citation2017), who use the ICT milieu as a proxy for informal learning. Other research have confirmed these findings, such as Heeks (Citation2010) and Comi et al. (Citation2017). Secondary research findings from the same study, which showed a correlation between recreational ICT use and better scores on having read and science indices, made this evident(Hu et al., Citation2018). Further research found that stronger academic achievement was substantially correlated with increased ICT interest, ICT competence, and ICT autonomy. Therefore, this study aims to determine how ICT usage affects SCS students’ academic performance and the difficulties that come with it in a developing nation, specifically Ghana.

2.2. Theoretical framework

The research used the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) developed by Davis, Bagozzi, and Warshaw in 1989 as its guiding hypothesis. The two elements that influence whether potential customers will accept a computer system are perceived usefulness and perceived user-friendliness, according to the TAM depicted in Figure .

2.2.1. Definition of constructs

External Variables in this study illustrate the challenges faced by students who try to integrate new technologies into their academics from sources they have no control over. These challenges include limited availability and network connectivity, a lack of adequate training, a lack of time, and incompetent student, as well as schools with limited ICT resources.

Perceived Usefulness in this study is the extent to which a student thinks using a specific ICT tool would improve their academic performance. Again, Perceived Usefulness refers to whether or not students think the tool will be helpful for their academic work.

Perceived Ease-Of-Use in this study indicates how much a student perceives using a specific ICT tool in their academics would be effortless (Davis et al., Citation1989). The barriers will be overcomed if the said ICT tool is simple to use. No student will have a positive attitude toward the tool if it is difficult to use and complex.

Attitude Towards Use in this reading refers to a student’s positive or negative feelings about using a specific ICT in their academics. The ease with which students can use ICT tools both individually and in the classroom influences their views and attitudes towards the usage of the tool which may lead to their academic performance.

Behavioral Intention in this study is the degree to which students make conscious decisions to engage in or refrain from using a specific ICT tool use.

3. Research methodology

This study accessed the effect of ICT usage on SCSs students’ academic performance and its associated challenges in a developing country specifically Ghana with a focus on the Jirapa SHS located in the upper west region of Ghana. The study used a mixed-method to achieve its objectives. The mixed-method approach was to allow for large objectives of breadth and depth of understanding, as well as strengthening (Dopp et al., Citation2019). The quantitative method entailed gathering statistical Information on students’ academic performance. In this study, the qualitative method was used to gather data on students’ attitudes toward the Use of ICT in tuition and learning activities. The inclusion of a qualitative approach alongside a quantitative approach is motivated by the fact that students benefit differently from the Use of ICT in their academics. The respondents of this reading were the final-year students of the Jirapa SHS. The respondents of this study were chosen using the Yamane formula, taking into account the study’s representative population to be studied to represent them proportionally. The total number of final-year students is 172 (Field survey, 2022). The Yamane formula is mathematically defined as:

n = N/(1 + N (e) ^2) where

n = is the required sample size.

N = the population size of the four classes

e = Allowable error (which in this study was pegged at 0.05)

As a result, the sample size was calculated as follows:

.n = 172/(1 + 172(0.0025))

n = 172/(1 + 0.43)

n = 172/1.43

n = 120.27972

n = 120

This indicates the number of study respondents. The study’s respondents were classified using a “Yes” or “No” card. Students who chose “Yes” were interviewed, whereas those who chose “No” were not. Both a questionnaire and an interview guide were used in the study to gather data. In order to gather data from the study partakers, a questionnaire and an interview guide with open-ended questions were both used in this study. There were various sections on both the questionnaire and the interview guide. Data on the sociodemographic characteristics of the pupils were gathered in the first segment. The different uses of ICT were covered in the second section. In the third portion, there were interviews concerning how ICT facilities are used and run. The fourth segment covered the elements that affect how well students learn when utilizing ICT resources, and the fifth section concentrated on the difficulties that come with ICT use. The Information was gathered between June 2022 and November 2022.

Both qualitative and quantitative analyses of the data collected were done. In order to assess the qualitative data and reoccurring pattern, thematic analysis was applied. In order to produce structured responses or meaning within the data, identification was begun in order to recognize the key themes in the study’s data. The collected data were checked for consistency. The data was presented using frequency tables, pie charts, and bar charts.

4. Results and discussion of findings

4.1. Respondents’ Demographic Characteristics

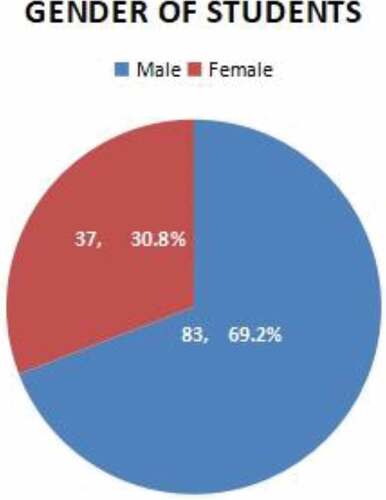

Data was collected from only final-year students of Jirapa SHS in the Jirapa District.

Table shows the age distribution of the students. According to the data 9 (7.5%) of the students were between the ages of eleven and fifteen (11–15). The majority of the students representing 90 (75%) fell within the sixteen to twenty (16–20) age bracket and the remaining 21 (17.5%) fell in the above 21 years bracket. The majority of students are among the ages of 16 and 20, according to the findings of the preceding analysis.

Question 1: What are the available ICT tools and what factors influence the Use of ICT in Second Cycle Schools?

The study found that 30.0% of the students have mobile phones which were the commonest ICT facilities available, and 18.3% of students have computers. Also, 0.8% have a digital camera as the least ICT facilities, and 1.8% have Internet or modems connected to their ICT facilities. Computers and mobile phones were (15.8%); 12.5% have computers and internet and 3.3% have computers, mobile phones, and the Internet. In all, students were privileged to have these ICT facilities to aid their studies. Furthermore, according to the findings, many of the students have access to a computer and often use it to develop computer skills; yet, only a few of the students have access to the internet through an internet café.

Table 1. Age Characteristics of the Respondent

Regarding the features that effect the Use of ICT in Jirapa SHS, students were asked if they utilize these ICT facilities in their academics, to help foster learning or make learning easy for them. Their response is presented in .

Table 2. Available ICT Tools

Table 3. Do you use computers for your academic activities?

Table depicts how computers are used in the student learning process. The outcomes exposed that the majority of the students, as many as 76 students (63.3%), use computers, while 44 of these students (36.7%) do not. To conclude, the majority of students use these computers for academic purposes.

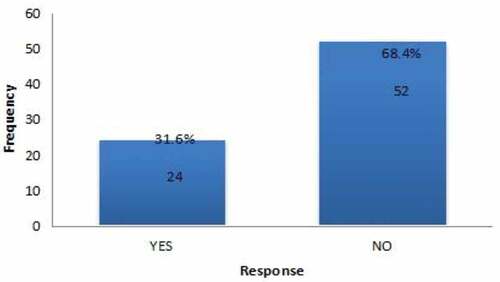

Students were further asked whether they have an internet connection to the computers and the results revealed that most of the students who have these computers are not connected to the internet. Twenty-four (31.6%) of the students who use computers are connected to the internet while fifty-two (68.4%) do not have internet access. This response is represented in the bar chart below.

The number and percentage of places where pupils have access to ICT resources are displayed in Table . As was already said, the majority of students who lacked access to ICT resources at home were able to use them in different public spaces. ICT is available to 42.5% of these kids in the classroom. Additionally, 17.5% of students have access to ICT at either their friend’s or the school’s location, 10.8% of students have access to ICT at the Internet café, 0.8% of students have access to ICT at the community library and other sites. It was also discovered that 10% of these students had access to these facilities at both their friend’s home and the internet cafe, while only 8.3% of these students had access to these facilities at either their friend’s home or the school.

Table 4. Access to ICTs Outside the Home

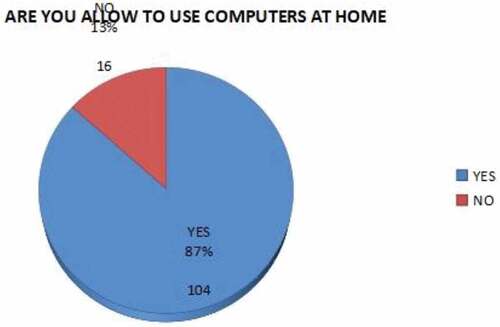

In conclusion, the majority of students have access to ICT amenities at the school, making it a good place for teachers to intensify their teaching for the benefit of students. Students used ICT tools from various locations, and the researcher wants to know if their parents allow them to use these facilities. This was revealed by the survey depicted in the figure below.

Figure shows that, if some parents cannot afford ICT facilities for their children, they encourage and allow them to use them for learning purposes in various locations for their academic purposes. Figure shows that 104 students (87%) said their parents allowed them to use ICT facilities, while the remaining 16 students (13%) said their parents do not allow them to use ICT facilities at all. As a result, one can conclude that the majority of students use ICT facilities to change their learning attitude and thus improve their performance.

According to Table , 112 (90.7%) of respondents answered positively to the question of whether they use the pieces of equipment for learning. The remaining 8 (9.3%) responded negatively. Figure portrays that the majority of participants are enthusiastic about the Use of ICT technologies. It can be concluded that students use this equipment to help them learn more easily and to improve their self-learning.

Table 5. Do you use ICT Facilities for Learning

5.2. Question 2: What are the effects of ICT usage on student academic performance?

Because the majority of students use ICT facilities for learning and because their parents have given them permission to use them, the study aims to examine the consequences of ICT usage on student academic achievement. To measure the effect of ICT on students’ learning motivation and performance, a five-point Likert scale was created. The scaled-ranked responses were arranged in ascending order, beginning with 1 (Never improved) and ending with 5 (Never improved). (This has greatly improved).

In the area of willingness to learn on their own, 33.6% of the students shown in Table stated that ICT had significantly increased’ 45.5% of respondents’ willingness to learn on their own. However, 10.9% of students disagreed with the report. In addition, 5.5% of respondents said that ICT had “never increased their willingness to learn on their own.”

Table 6. Willingness to learn on your own

The study also sought to ascertain how frequently students use computers and the Internet to conduct research for writing assignments. The Use of computers and the Internet improved students’ performance significantly, according to 30.8% of students. In addition, 44.2% thought that using computers and the Internet to find Information had “improved” their performance. However, 8.3% were neutral, meaning they couldn’t say whether using computers and the internet improved their learning or not, and 10% said that using computers and the Internet to seek Information had “never improved” their performance. It can be concluded that more than half of the student’s academic performance has improved as a outcome of the availability and Use of ICT facilities.

Table revealed that 25.0% of students improved in their ability to use word processing applications to type as a result of home access. Furthermore, 44.2% of students reported that having home access had “improved” their performance and ability to type on word processors. However, 8.3% indicated that access to ICT at home had ‘not improved their performance in using word processors. According to the data, access to and Use of ICT facilities has had a significant inspiration on student performance because more students can now use a word processor to produce documents on their own.

Table 7. Using word processing application to type letters

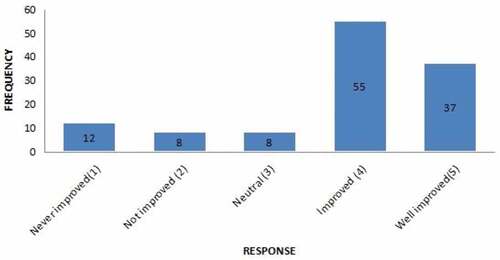

According to Table , 12 (10%) and 8 (6.7%) of respondents say that using computers has never and has not improved their ICT learning, respectively. 8 students (6.7%) were neutral, while 55 (45.8%) improved their ability to learn on their own with the help of ICT. According to the data presented above, the majority of respondents believed that computers helped them to learn on their own without any assistance from anyone.

Table 8. Helping you learn without assistance

Regarding the challenges concerning ICT use in tuition and learning, Table shows that 11 students (9.1%) responded that insufficient ICT teachers in school are a challenge to them because teachers are few in comparison to the student population, whereas 20 (16.7%) say teachers’ attitude toward teaching ICT is a challenge to them when using ICT in learning. 8 (6.7%) students say their challenge is a lack of ICT tools and equipment, while 17 (14.2%) students say a lack of educational software is a challenge because they do not have access to the internet. Lack of internet access is cited by 33 (27.5%) of students as their major challenge in using ICT in learning processes, while power fluctuations are cited by 16 (13.3%). Inadequate sockets and furniture are also a challenge for other students when using ICT in learning processes, with 7.5% and 5% responding, respectively. The conclusion is that the most significant challenge for students when using ICT for learning is a lack of internet access.

Table 9. Challenges with the Use of ICT in Learning Processes

4.3. Discussion of Findings

4.3.1. Available and Factors Influencing the Use of ICT Tools

The study discovered that ICT facilities were either limited or insufficient. Mobile phones and computers were the most commonly used ICT facilities in the sampled homes. Other ICT resources, such as digital cameras, printers, and Internet or modems, were limited. The availability of ICT facilities was unequal, resulting in those with ICT facilities benefiting more in performing ICT-related skills in school, as evidenced by the greater number of students who had and used these facilities for learning. The accessibility and Use of ICT equipment motivate students to learn more quickly and easily, and it is beneficial to their academic performance. When students have access to ICT equipment, they use it to conduct research or to search the internet for answers.

Learning ICT skills prepares students for a working world that increasingly demands such skills. Students, according to the responses, used these ICT facilities for learning rather than just having them. Some people have these resources but do not make effective Use of them in their studies, however, this was not the case in this reading. Parents also played an relevant role in allowing their children to use these facilities and, to some extent, in allowing them to use these facilities at different locations, such as friends’ homes, internet cafes, and schools. According to the findings of the study, this increased students’ motivation to use the ICT facilities to learn.

4.3.2. Effects of ICT Usage on Student Academic Performance

It was clear that ICT resources enhanced student learning. Using ICT facilities attracted the interest of the majority of students in learning. Furthermore, their ability to search for Information on a computer and the Internet to complete their task had improved. It was also exposed that the majority of students’ ability to use word processing applications to type documents such as letters, which had previously been lacking, had improved since the majority of them could type on their own. Furthermore, using a tutorial to clarify a school-taught concept was the most effective way to understand it. It was once again observed that ICT facilities assist students in erudition without assistance in school and sometimes at home.

4.3.3. Challenges Associated with the Use of ICT in Learning Processes

According to the study’s outcomes, students face a variety of challenges when using ICT in the learning procedure. The majority of students, as evidenced by their responses, believe that the most significant challenges they face when using ICT in learning are insufficient internet access and some teachers’ attitudes toward teaching ICT. There were also minor challenges such as a lack of ICT teachers, educational software, and ICT tools and equipment, which were deemed minor based on the data collected. It was exposed that the trials most students have with an internet connection do not aid in their learning processes, affecting their performance as expected when using ICT in the learning processes.

5. Conclusion

The aim of the study is to access the outcome of ICT usage on SCS students’ academic performance and its associated challenges in a developing country. The study concluded that the availability of ICT resources at SCSs and sometimes homes are critical to the success of ICT in SCS education. ICT can help students understand complex processes by using simulations. According to Börner et al. (Citation2019), ICT can be used to provide visualization and variations in a variety of disciplines. The impact of ICT use on students’ academic routine is significant. This finding was consistent with Samerski (Citation2018), who stated that future ICT may enable Ivan Illich’s early 1970s de-schooling movement. Although well-structured classroom instruction cannot be substituted, the home and society have a significant impact on student attitudes and performance. Some studies have argued that home influence is powerful enough to undermine school effectiveness (Comi et al., Citation2017; Kumashiro, Citation2015).

5.1. Recommendations

The study recommends that parents should make an effort to provide ICT resources for their children, such as computers, internet access, and printers among others. Adequate ICT provision for their wards will enhance student motivation to learn. This will improve their learning performance and motivation significantly.

Again, regular monitoring and evaluation of ICTs in educational policy are required to assess policy implementation progress and weaknesses. This will provide policymakers with feedback that will help them plan the integration of ICT into education.

Furthermore, governments of developing countries should make sufficient funds available for providing universal access to ICT to unserved and underprivileged groups. The governments of developing countries should expand their Community Information Centres (CICs) in rural and urban areas to provide students with easy access to ICT services.

5.2. Suggestions for Future Studies

A mixed-methods style was used in this study. Other studies in developing countries can use different methods in a similar study. Additionally, this study was limited to SCS students. Other stakeholders at various educational levels in other developing economies may be included in future studies. Future research can include case studies from various developing economies in a similar study. Furthermore, future research in this field can combine both public and private SCSs, as well as a larger sample size.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate everyone who agreed to participate in the study and gave their informed consent. We also acknowledge the assistance of the Takoradi Technical University and Pentecost University Research Ethics Boards in obtaining their support and consent for the conduct of this work.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ronald Osei Mensah

Ronald Osei Mensah, is an Assistant Lecturer with the Social Development Section, Takoradi Technical University, Takoradi, Ghana and a PhD Candidate with the Department of Sociology and Anthropology, University of Cape Coast, Ghana. He has cross-cutting research experience in the area of Sociology of Education, Sociology of Law and Criminal Justice, Social Justice, Media Studies and African History.

Charles Quansah is a Geographical expert and specialist in rural development. He holds PhD in Geography from the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST), Ghana. His research interest cuts across pedagogical geography, land formation, oceanography, and climatology.

Bernice Oteng is the Head of Social Science Department, Accra College of Education, Ghana. She holds PhD in Education (Curriculum and Instructional Studies) from the University of South Africa-UNISA, Pretoria. Her research interests are into Social Studies Education, Social Studies Methodology, Adult Education, Curriculum and Assessment, and Sociology of Education.

Joshua Nii Akai Nettey is a computer scientist by profession and a Lecturer with Pentecost University, Ghana. He has Master of Philosophy in Management Information Systems. He conducts research in artificial intelligence, computer forensics, information systems and computer communication networks.

Charles Quansah

Charles Quansah is a Geographical expert and specialist in rural development. He holds PhD in Geography from the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST), Ghana. His research interest cuts across pedagogical geography, land formation, oceanography, and climatology.

Bernice Oteng is the Head of Social Science Department, Accra College of Education, Ghana. She holds PhD in Education (Curriculum and Instructional Studies) from the University of South Africa-UNISA, Pretoria. Her research interests are into Social Studies Education, Social Studies Methodology, Adult Education, Curriculum and Assessment, and Sociology of Education.

Joshua Nii Akai Nettey is a computer scientist by profession and a Lecturer with Pentecost University, Ghana. He has Master of Philosophy in Management Information Systems. He conducts research in artificial intelligence, computer forensics, information systems and computer communication networks.

Bernice Oteng

Bernice Oteng is the Head of Social Science Department, Accra College of Education, Ghana. She holds PhD in Education (Curriculum and Instructional Studies) from the University of South Africa-UNISA, Pretoria. Her research interests are into Social Studies Education, Social Studies Methodology, Adult Education, Curriculum and Assessment, and Sociology of Education.

Joshua Nii Akai Nettey

Joshua Nii Akai Nettey is a computer scientist by profession and a Lecturer with Pentecost University, Ghana. He has Master of Philosophy in Management Information Systems. He conducts research in artificial intelligence, computer forensics, information systems and computer communication networks.

References

- Adarkwah, M. A. (2021). “I’m not against online teaching, but what about us?”: ICT in Ghana post Covid-19. Education and Information Technologies, 26(2), 1665–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-020-10331-z

- Al-Ansi, A. M., Suprayogo, I., & Abidin, M. (2019). Impact of information and communication technology (ICT) on different settings of learning process in developing countries. Science and Technology, 9(2), 19–28. https://doi.org/10.5923/j.scit.20190902.01

- Alderete, M. V., & Formichella, M. M. (2016). The effect of ICTs on academic achievement: The Conectar Igualdad programme in Argentina. Cepal Review.

- Avgerou, C. (2010). Discourses on ICT and development. Information Technologies and International Development, 6(3), 1–18. http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/35564/

- Barger, M. M., Kim, E. M., Kuncel, N. R., & Pomerantz, E. M. (2019). The relation between parents’ involvement in children’s schooling and children’s adjustment: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull, 145(9), 855–890. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000201

- Bhattacharjee, B., & Deb, K. (2016). Role of ICT in 21st century’s teacher education. International Journal of Education and Information Studies, 6(1), 1–6. http://www.ripublication.com

- Börner, K., Bueckle, A., & Ginda, M. (2019). Data visualization literacy: Definitions, conceptual frameworks, exercises, and assessments. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116(6), 1857–1864.

- Clark, K. R. (2015). The effects of the flipped model of instruction on student engagement and performance in the secondary mathematics classroom. Journal of Educators Online, 12(1), 91–115. https://doi.org/10.9743/JEO.2015.1.5

- Comi, S. L., Argentin, G., Gui, M., Origo, F., & Pagani, L. (2017). Is it the way they use it? Teachers, ICT and student achievement. Econ. Educ. Rev, 56, 24–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2016.11.007

- Darkwa, B. F., & Antwi, S. (2021). From classroom to online: comparing the effectiveness and student academic performance of classroom learning and online learning. Open Access Library Journal, 8, e7597. https://doi.org/10.4236/oalib.1107597

- Davis, F. D., Bagozzi, R. P., & Warshaw, P. R. (1989). User acceptance of computer technology: A comparison of two theoretical models. Management Science, 35(8), 982–1003. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.35.8.982

- Dopp, A. R., Mundey, P., Beasley, L. O., Silovsky, J. F., & Eisenberg, D. (2019). Mixed-method approaches to strengthen economic evaluations in implementation research. Implementation Science, 14(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-018-0850-6

- Emeka, U. J., & Nyeche, O. S. (2016). Impact of internet usage on the academic performance of undergraduates students: A case study of the university of Abuja, Nigeria. International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, 7(10), 1018–1029. http://www.ijser.org

- Furlong, J., & Davies, C. (2012). Young people, new technologies and learning at home: Taking context seriously. Oxf. Rev. Educ, 38(1), 45–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2011.577944

- Genlott, A. A., & Grönlund, Å. (2016). Closing the gaps–Improving literacy and mathematics by ict-enhanced collaboration. Comput. Educ, 99, 68–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2016.04.004

- Ghavifekr, S., & Rosdy, W. A. W. (2015). Teaching and learning with technology: Effectiveness of ICT integration in schools. International Journal of Research in Education and Science, 1(2), 175–191. https://doi.org/10.21890/ijres.23596

- Gil-Flores, J., Rodríguez-Santero, J., & Torres-Gordillo, J. J. (2017). Factors that explain the Use of ICT in secondary-education classrooms: The role of teacher characteristics and school infrastructure. Computers in Human Behavior, 68, 441–449. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.11.057

- Heeks, R. (2010). Do information and communication technologies (ICTs) contribute to development? Journal of International Development, 22(5), 625–640. https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.1716

- Hu, X., Gong, Y., Lai, C., & Leung, F. K. S. (2018). The relationship between ICT and student literacy in mathematics, reading, and science across 44 countries: A multilevel analysis. Computers & Education, 125, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2018.05.021

- Karamti, C. (2016). Measuring the impact of ICTs on academic performance: Evidence from higher education in Tunisia. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 48(4), 322–337. https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2016.1215176

- Kumashiro, K. K. (2015). Bad teacher! How blaming teachers distorts the bigger picture: How blaming teachers distorts the bigger picture. Teachers College Press.

- Lau, W. W. (2017). Effects of social media usage and social media multitasking on the academic performance of university students. Computers in Human Behavior, 68, 286–291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.11.043

- Lee, Y. H., & Wu, J. Y. (2012). The effect of individual differences in the inner and outer states of ICT on engagement in online reading activities and PISA 2009 reading literacy: Exploring the relationship between the old and new reading literacy. Learning and Individual Differences, 22(3), 336–342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2012.01.007

- Mathivanan, S. K., Jayagopal, P., Ahmed, S., Manivannan, S. S., Kumar, P. J., Raja, K. T., and Prasad, R. G. (2021). Adoption of e-learning during lockdown in India. International Journal of System Assurance Engineering and Management, 1. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13198-021-01072-4

- Rakhyoot, W. A. A. (2017). Institutional and individual barriers of e-learning adoption in higher education in Oman, academics’ perspectives. University of Strathclyde.

- Samerski, S. (2018). Tools for degrowth? Ivan Illich’s critique of technology revisited. Journal of Cleaner Production, 197, 1637–1646. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.10.039

- Skryabin, M., Zhang, J., Liu, L., & Zhang, D. (2015). How the ICT development level and usage influence student achievement in reading, mathematics, and science. Comput. Educ, 85, 49–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2015.02.004

- Tucker-Drob, E. M., & Bates, T. C. (2016). Large cross-national differences in gene_ socioeconomic status interaction on intelligence. Psychol. Sci, 27, 138–149. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797615612727

- Walsham, G. (2017). ICT4D research: Reflections on history and future agenda. Information Technology for Development, 23(1), 18–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/02681102.2016.1246406

- Wittwer, J., & Senkbeil, M. (2008). Is students’ computer use at home related to their mathematical performance at school? Comput. Educ, 50, 1558–1571. https://doi.org/10.1016/j0268

- Wu, H. K., Lee, S. W. Y., Chang, H. Y., & Liang, J. C. (2013). Current Status, Opportunities and Challenges of Augmented Reality in Education. Computers & Education, 62, 41–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2012.10.024