Abstract

An insufficient number of studies investigated the criteria for Arabic letter teaching in schools. Teachers play an integral role in understanding Arabic letters among young children, as it is essential for acquiring reading in the Arabic language early in life. The criteria for teaching letters in a current study include ease of pronunciation, long vowels, short vowels, ease of pronunciation, sound, shape, and letter names. It is important to consider letter teaching as it helps in the early recognition and identification of the language and in performing better academically. The focus of the current study is to explore the orthographic attributes of Arabic letters, how teachers teach these letters, the order and criteria they follow, and the relative difficulty of letter knowledge items within the Arabic alphabet framework. Arabic letter teaching criteria tests were conducted among 80 teachers from Arabic-speaking countries in UAE. These teachers taught Kindergarten, grade 1, and special needs children. The current study’s findings revealed that Arabic letter teaching efforts are dynamic as chi-square results are non-significant, reflecting that teachers’ criteria and order adopted do not depend on teachers’ level of education or their specific area of expertise. Findings show that most teachers who adopt ease of pronunciation of letters in teaching students start with long vowels. Furthermore, results indicated that most teachers introduce Arabic letters, sounds, and shapes when teaching young learners.

Public Interest Statement

![]()

![]() Exploring and analyzing the “orthographic properties” of Arabic letters has been the main goal of the research. The purpose of the paper was to show how teachers are teaching Arabic letters, what standards and procedures they use, and also how challenging the letters acquisition are within the context of the Arabic language. The paper effectively filled a void in the research evidence and raised consciousness about the role of instructors in the education of Arabic letters. The research provides evidence of literacy-related aspects in Arabic. The study’s foremost significant finding was the teacher’s credentials. Different nations establish criteria by which they classify a teacher as qualified in terms of the country’s schooling institutions. Teachers need to be able to inspire, encourage, and provide students with the tools they need to advance their own learning independently. They must also be capable of maintaining a high quality of “teaching and learning” implementation. Finally, the paper came to a conclusion by analyzing the findings, which demonstrated that teachers should start their students’ learning of letters with short vowels to make them easier to pronounce. It also revealed that most educators consider introducing Arabic letters, sounds, and shapes when instructing younger students.

Exploring and analyzing the “orthographic properties” of Arabic letters has been the main goal of the research. The purpose of the paper was to show how teachers are teaching Arabic letters, what standards and procedures they use, and also how challenging the letters acquisition are within the context of the Arabic language. The paper effectively filled a void in the research evidence and raised consciousness about the role of instructors in the education of Arabic letters. The research provides evidence of literacy-related aspects in Arabic. The study’s foremost significant finding was the teacher’s credentials. Different nations establish criteria by which they classify a teacher as qualified in terms of the country’s schooling institutions. Teachers need to be able to inspire, encourage, and provide students with the tools they need to advance their own learning independently. They must also be capable of maintaining a high quality of “teaching and learning” implementation. Finally, the paper came to a conclusion by analyzing the findings, which demonstrated that teachers should start their students’ learning of letters with short vowels to make them easier to pronounce. It also revealed that most educators consider introducing Arabic letters, sounds, and shapes when instructing younger students.

1. Introduction

The need to strengthen teachers’ pedagogical knowledge about the most effective way of teaching and reading the Arabic language to early school children due to a multiple lexicon connection between various dialects and Modern Standard Arabic (MSA) exists. Enhancing this knowledge in teaching curriculum and materials will assist the student in learning to read Arabic letters (Kwaik et al., Citation2018). Failure by teachers to carefully plan the order of teaching the language, the connection, and similarities between the dialects makes it challenging to guide the learners from colloquial Arabic to the MSA.

According to Taha-Thomure (Citation2008), teachers must flexibly teach children reading and writing literacy without emphasizing rules and grammar. Also, they need to precisely but playfully engage the learners during Arabic literacy learning. For learners to master Arabic words, Miles and Ehri (Citation2019) suggested that teachers concentrate on sound and the symbols representing the sound instead of cramming every string of letters. Teachers need to ensure beginner learners synthesize every letter of a word to develop their memory of words. However, Gregory et al. (Citation2021) recommended that attaining Arabic letter knowledge is a long process that teachers must handle objectively without subjecting the learners to speed and fluency. The goal of teachers in this whole process is to give complete knowledge and understanding of letter names with their related sounds.

The current study is propelled by the commendation of Castles et al. (Citation2018) on the need to teach phonics systematically, where a teacher teaches letter-sound together by pronouncing the words. This practice is still uncommon in various learning institutes of Arabic-speaking nations, even though neuroscience and education researchers acknowledge how valuable it is.

1.1. Significance of the study

The study finds its significance in examining the role of teaching Arabic letters to young children within the UAE. It will explore the criteria for teaching the Arabic letter. This will contribute to filling the gap in the empirical literature and increasing awareness regarding the role of teachers in Arabic letter teaching. Other than this, the study will contribute to expanding the empirical literature, due to which it also finds its significance in academic settings. Future researchers can take advantage of the research findings. Besides this, it also finds its significance in social, communal, and educational settings.

1.2. Literature review

1.2.1. Arabic language and its characteristics

Arabic is considered a diglossic language, meaning the language has a linguistic state with two forms of language that are used simultaneously. According to Poyas and Bawardi (Citation2018), the fact that Arabic is a diglossic language affects the ability of new learners to read and write. However, to address these literacy challenges, various techniques are used by teachers. One of these techniques includes focusing on letter-sound recognition at the early stages of education, precisely the preschool stage. By focusing on the strategy of letter-sound recognition, new learners can understand the unique features and characteristics of the Arabic language at an early age.

Arabic language is distinctive and has some unique features. First, it is contextual without many punctuations mark (Saiegh–Haddad, Citation2003). When punctuation marks are used, they are placed differently on the word. For instance, Abu-Chacra (Citation2017) advises that an Arabic comma is placed on top of the word, which is different from an English comma at the end of the term. Secondly, Arabic is written from right to left, unlike most languages (Papadopoulos et al., Citation2014). Arabic is also written in cursive format, making it visually appealing (Zidouri, Citation2010). Third, the Arabic alphabets have three vowels that can be stressed differently to produce six, three long, and three short. Therefore, most Arabic alphabet is consonant (Papadopoulos et al., Citation2014).

Arabic is written in alphabetic systems with all consonants apart from three vowels. The position of the alphabet in the word makes most Arabic alphabets have more than one written form (Zidouri, Citation2010). Arabic is deeply orthographical, requiring beginners to read vowelized terms with shallow orthography, and those experienced can read unvowelized words with deep orthography (Abu-Rabia, Citation2007). These fully vowelized words are mainly used in children’s books, the Quran, and children’s poetry, where they learn how to use the specified phonologically with a simple writing system in which every phoneme is represented with its correct spelling (Fender, Citation2008).

Watson (Citation2011), in his analysis of Arabic words, highlighted that only three-syllable weights exist in Arabic. They include light syllables, usually open; heavy syllables, both open and closed; and super heavy ones, closed or two-ways closed. Moreover, the Arabic language contains several variations for various letters. The location of a letter in a word determines its form (Abandah & Ansari, Citation2009).

1.2.2. Arabic alphabets

The Arabic alphabets have twenty-eight basic letters (Abandah & Ansari, Citation2009). Every Arabic letter has multiple forms, depending on its position in the word, whether at the beginning, middle, or end. Each letter is drawn in an isolated form when written alone and illustrated in three other ways when connected to other letters in the word (Yassin et al., Citation2020). The letters change shape depending on their position in the word.

Apart from having twenty-eight basic letters, Arabic has eighteen different shapes. With the help of diacritical marks, the eighteen shapes that make up the Arabic language express twenty-eight phonetic sounds. The same Arabic letter can form different sounds depending on the position of that particular letter in a word (Yassin et al., Citation2020). This is a unique Arabic letter characteristic that educators and teachers must emphasize when teaching new learners and other individuals interested in knowing the language.

According to Zidouri (Citation2010), Arabic alphabets can be grouped into one-hundred-character shapes, with most characters possessing many similarities and multiple loops and cusps. These alphabets are written from right to left and comprise twenty-eight consonants and six vowels. Three of the six vowels are long, and three are short. Arabic alphabets are not case-sensitive (Papadopoulos et al., Citation2014). These three long vowels, according to Yassin et al. (Citation2020), include/long a, ā: ـَا/denoted by the letter “alif,/long i, ī: ـِي/denoted by yā,” and/long u, ū: ـُو/represented by the letter wāw.

Writing the Arabic language is done in an abjad, a consonantal writing format (Daniels & Share, Citation2017), and writing Arabic runs from right to left. The language’s orthography comprises a double pair of graphic signs, letters arranged horizontally, and diacritic signs arranged vertically (Yassin et al., Citation2020). Most letters enjoy the same structure, with the only difference coming in from where they exist, are placed, and how many dots they have (Eviatar & Ibrahim, Citation2014). The dots are mandatory in Arabic letters forming a vital part of a letter, just like lowercase letters in English, i and j. Letters amounting to fourteen in the form of /ط ظ /ع غ /ف ق /د ذ/ ر ز س ش/ ص ض (a pairs), six خ ج ح (double triplets), and ت ث ب or have a common letter shape referred to as rasm (Yassin et al., Citation2020).

1.2.3. Visual attributes of Arabic letters

Visual attributes of every Arabic letter define letter identification complexity (Wiley & Rapp, Citation2018). Several visual attributes of Arabic letters make it difficult to master, particularly for beginners. Property identification of these attributes will thus be a successful determinant when learners are introduced to reading and learning Arabic early in school. Teachers are expected to help learners identify the more complex letters and spell out the visual attributes of the same.

According to Zidouri (Citation2010), letters may change their form based on their position and whether they are related to the preceding letter. As a result, Arabic orthography introduces errors in letter positioning in words (Yassin et al., Citation2020). Two factors determine the form of letters: the letter’s position in the word and whether it connects with its preceding letters. A combination of connections and placement of letters in the word creates four-letter forms, a word form with a letter at the beginning of the word, in the middle of the word which connects with the preceding letter, and a form of final letters that relate with the initial term, and a form of a letter that do not connect with the primary word (Friedmann & Haddad Hanna, Citation2012). The visual similarity in the shapes of Arabic letters, the number of dots above or below the letter, and the changing forms of letters complicate both reading accuracy and the rate of reading the Arabic language (Ibrahim et al., Citation2013).

1.2.4. Phonological attributes of Arabic letters

There exists a great relationship between sound and Arabic words. Sound is one of the smallest linguistic units. However, the unit greatly impacts the meaning of different words. For this reason, a single word with different phonemes produces different meanings. Arabic words use specific phonemes to produce meaning (Khitam, Citation2019). The Arabic words either use phonemes with heavy articulation or light articulation.

The Arabic letters are complex; hence readers are encouraged to rely on visual rather than morphological processing (Almutiri, Citation2022). Moreover, the orthographical features of these letters produce a visual load that slows down phonological processing. Phonological similarities of Arabic letters require learners to know word connection and dot positioning on the word since the same letter may have different forms depending on its position in the word (Taha, Citation2013).

1.2.5. Reading, reading acquisition, reading difficulties, and dyslexia

Children begin to acquire vocabulary and make sense of it through dialogic reading, which aims to develop vocabulary by reading pictures and then relating it to print (Arnold & Whitehurst, Citation1994). This learning could occur in the home, and school settings as children actively learn from their environment in this stage of development. Another form of reading approach that helps youngsters to enhance fluency, listening comprehension, and expressive language is reading aloud (Arnold & Whitehurst, Citation1994; Willingham, Citation2015). Parents are encouraged to read aloud to their children while they are young. Children must grasp a range of sub-skills to increase their overall reading abilities and progress toward becoming independent readers.

Letter knowledge is essential in literacy acquisition. Children transit to reading and writing more complex orthography that lacks some phonology as they grow, mostly in fourth grade (Hussien, Citation2014). While at tender ages, children learn vowelized scripts more efficiently, and by the end of elementary classes, they can read unvowelized texts. Berninger et al. (Citation2002) investigated that knowledge of spellings children develop along the way is directly linked with word recognition. Proper spelling knowledge leads to appropriate word recognition, which helps a child’s reading comprehension; it equips children with comprehension skills more than listening (Fender, Citation2008).

The complex nature of the Arabic language makes it difficult for learners to learn it in the early years of childhood, especially children with a learning disability, i.e., dyslexia. Children diagnosed with reading disabilities face problems understanding letters, syllables, phonemes, and visuoperceptual understanding of various Arabic letters (Hammond, Citation2013). Providing proper remedial classes to such children using various guided reading strategies is pertinent. These strategies improve visual understanding that facilitates reading comprehension of Arabic literacy.

Further, Arabic has some frequently used letters and others that are not commonly used. The frequency of the Arabic alphabet affects language acquisition and simplicity in reading by Arabic learners (Madi, Citation2011). An analysis of Arabic textual scripts such as the Holy Quran revealed the most frequent and less frequent letters. This analysis was done on a large data sample containing over five million letters to get a fair distribution table of Arabic letters for letter frequency analysis. The most frequent Arabic letters were found to be “l,ل” and “a,أ,” while the less frequent letter is “j,ج” (Madi, Citation2011). Regular letters need less time to learn as compared to less frequent letters. Analyzing the frequency of Arabic letters enables educators to make informed decisions while preparing instructional materials for ease of language acquisition and simplicity in reading the Arabic language (Boudelaa et al., Citation2020).

1.2.6. Significance of teachers’ qualification in Arabic literacy

Teachers’ educational qualification affects a child’s Arabic language acquisition capabilities and performance (Al-Muslim et al., Citation2020). Different countries set standards upon which they define a qualified teacher concerning the country’s educational system. Teachers must have the ability to lead and maintain a high standard of teaching and learning delivery and must inspire, motivate and equip learners with independent learning progress (Al-Muslim et al., Citation2020; Ariffin & Al-Muslim, Citation2015).

Teachers’ qualification level determines their preparedness to impart reading skills to learners. Adequate preparation in training equips teachers with knowledge on assessing the cause of reading difficulties in learners (Farhoud, Citation2018). Media literacy taught by training teachers provides them with expertise in guiding learners on using electronic equipment to write Arabic characters (Hobbs, Citation2007). Media learning is essential to learners with disabilities since it helps in active participation, improved attendance, and self-confidence.

A teacher qualification is one of the most vital factors determining how well new learners can read and write the Arabic language. Retnawati et al. (2020) investigated how a teacher’s Arabic skills and knowledge influences new learners’ Arabic fluency and basic vocabulary mastery. When the teacher does not have adequate educational qualifications, learners tend to have difficulties understanding the language content during the learning process. As a result, most of them take a long time to learn how to spell, read or even write certain Arabic words. Therefore, teachers involved in teaching the Arabic language should not only have comprehensive knowledge about the language but also understand the most effective teaching strategies that they can use to enhance language acquisition among new learners who have been enrolled in different institutions. Besides, Arabic teachers ought to know in which order they must teach Arabic letters; based on which criteria.

Most Arabic words always begin with a consonant. Teachers’ knowledge of this unique feature of the Arabic language can play a major role in ensuring that the highest percentage of new learners can acquire Arabic literacy skills at the right time without experiencing so many challenges (Ariffin & Al-Muslim, Citation2015).

1.2.7. Reading approaches used by teachers in UAE

The phonics method is the most commonly used method to enhance reading development among Kindergarten and Grade 1 children. The phonic method is used all over the world, including UAE. In UAE synthetic phonic method is used by teachers for reading Arabic letters in which firstly, teachers teach sounds of letters and then link these broken sounds in the pronunciation of the whole word (Arnold & Whitehurst, Citation1994). In most UAE-based schools, priority is given to “reading for enjoyment”, in which the educator focuses on engaging students in reading classes through unique activities.

According to Armbruster (Citation2010), vocabulary is important in language development. Children learn language by listening to different sounds from their environment and storing repeatedly used sounds and words in their memory. These stored words added to oral knowledge, followed by reading abilities development. Reading skills are also associated with schema formation, logical reasoning, and comprehension (Roskos & Neuman, Citation2014).

In UAE, the government emphasizes fostering a reading culture among young children. For this purpose, they announced the National Reading Law in 2016 (Radan, Citation2016). Many strategies help increase reading habits among children, such as emergent reading, shared reading, reading aloud, and guided reading by parents, teachers, and significant others (Fountas & Pinnell, Citation2012).

Reading Arabic books with children facilitates word acquisition and the development of reading skills among them. Coyne et al. (Citation2004) reported that correctly executing shared reading as a strategy successfully increased the Arabic vocabulary of children with reading challenges. In the United Arab Emirates, children with Learning Disabilities or Dyslexia are getting extra attention after implementing inclusive education planning law. According to this, all learners having learning difficulties must be placed in mainstream schools, and teachers are fully trained to handle their problem areas. The UAE government plays a vital role in educating students with special educational needs and disabilities (SEND), also known as People of Determination (POD), in the UAE. It has taken initiatives to support inclusive education for these students, notably over the last decade. This initiative creates performance responsibility among teachers as it is a challenging goal for them to increase their students’ learning. Teachers’ qualifications, experience, and training play an essential role in providing reading classes to children with reading difficulties (Fountas & Pinnell, Citation2012).

1.3. Theoretical model for the current study

This research investigated Arabic letter teaching using both Al-Burāq Model and teaching Arabic letters (as mentioned in Table ). This model reduces the number of shapes in the old alphabet table from 78 shapes to 32 shapes. The model has been used since 2005 in high schools Arabic Beginners’ classes, professional development, and tertiary education (Grigore, Citation2016. The current study is based on this model, depending upon its implication in some educational settings. Previous studies have given little attention to how teachers handle young learners in Schools within Arabic countries. Such studies have not used the AQAN to understand the effectiveness of Arabic literacy teaching among teachers. The model acknowledges the possibility of up to four forms of shapes of an Arabic letter based on its position in a word. For instance, an Arabic letter could stand independently; it could be joined from right, left, or connected from left and right.

Table 1. Al-Burāq Model of Teaching Arabic Letters (Parrinder, 1990:146)

Using this framework, the study explored teaching the basic letters of the alphabet, where letters can sometimes overlap vertically. Furthermore, the model posited the indefinite shape of Arabic letters in terms of letter height and width. The study explored some of the short vowel letters in a word like Fat-hah to indicate how dynamics Arabic language teachers need to be. In teaching, they need to understand the diacritics of Arabic letters and how the children must learn to write them in strokes at the top or bottom of the letters. Since a separate diacritic placed on letters can alter what a word means, AQAN was used to gauge teaching effectiveness.

1.4. The rationale of the study

Early development plays a vital role in predicting or determining the rest of the child’s life, personality attributes, and achievements. About 85% of the human brain develops in the first five years. According to Blossom and Morgan (Citation2006), the human brain is highly receptive in the early years of life as neural pathways and connections form in this timeframe. As the child experiences or interact with new information, they develop neural connections. These early childhood experiences determine later life experiences either positively or negatively depending upon the nature of the information they stored in their memories. In this regard, parents and teachers play a crucial role in child development, i.e., language acquisition, learning, social competence, emotional understanding, and cognitive development.

Language development is one of the pivotal aspects of child development. According to Blossom and Morgan (Citation2006), in human beings, language development starts before birth, and in a few months after birth, the baby starts to recognize the familiar voices of his primary caregiver and discriminate between them. The order in which a child develops language structures, phonemes, syntax, syllables, and letters are consistent across culture. This universal language acquisition system was proposed by Chomsky (Citation1957), according to which human beings have an innate mechanism called a “language acquisition device”, which helps in learning language across various cultures and dialects.

The current study investigates the phenomenon of Arabic letter learning in the context of teaching attributes. Some factors interplay in teaching Arabic letters to young children. Teachers’ understanding of these factors is fundamental to incorporating them into their Arabic literacy classes. Even though the orthographic nature of the Arabic language makes it difficult for new learners to understand it, certain mechanisms can be used to promote the understanding of the Arabic language among new learners. According to Tibi et al. (Citation2021), understanding orthographic regularities is one of the critical strategies teachers can use to improve new learners’ understanding of the Arabic language.

Learners’ knowledge of the Arabic phonological structure of language reveals their reading ability at an early age (Saiegh-Haddad & Taha, Citation2017). Children who have difficulties in phonological processing, i.e., dyslexia, face difficulty learning various sounds pronounced specifically with certain letters (Hammond, Citation2013). These children have problems learning phonemes attached to various letters. Impairment in the phonological representation of Arabic letters in a learner is an early indicator of developmental dyslexia. For this reason, there is a strong need to train teachers teaching in Kindergarten, grade one, and special education centers in the UAE so that they can understand the problems faced by children with reading difficulties.

Research conducted by Al-Sulaihim and Marinis (Citation2017) indicates that phonological awareness is extensively linked to literacy. Through phonological awareness, children can be in a position to blend and segment words into their components, such as phonemes and syllables. Thus, phonological awareness is a practical aspect of language acquisition, especially for beginners.

Besides phonological awareness, letter knowledge is another important aspect of children’s reading and writing of Arabic (Al-Sulaihim & Marinis, Citation2017). For this reason, learners cannot understand how to read and write the Arabic language if they do not know the alphabet. These two factors determine each other. Alphabet knowledge makes learners develop phonological skills that they need for them to have a comprehensive understanding of the Arabic language. In the present study, our objective is to explore the role of teacher’s qualification and their literacy practices which they commonly apply in teaching Arabic to Kindergarten, grade 1, and special needs children.

2. Method

2.1. Research questions

Do teachers who adopt ease of pronunciation of letters criteria also start with short vowels and then long vowels?

Does the teacher’s major teaching area define how they introduce a letter, sound, and shape?

Do teachers’ qualifications correlate with the criteria and order they teach Arabic letters?

Answers to these questions are essential in understanding the features of Arabic letters and how teachers handle Arabic teaching among kindergarten, grade 1, and special needs children.

2.2. Hypotheses

HO – A teacher’s education level is not related to the criteria and order they use to teach Arabic.

H1 – A teacher’s education level is related to the criteria and order they use to teach Arabic.

2.3. Approach and research type

The research approach followed within the study is the quantitative approach. The quantitative research approach is based on the statistical analysis of the research variables and finding the statistical patterns within the findings. Quantitative research helps in the determination of the research outcomes as well as in finding out the correlation between variables with descriptive analysis. Besides this, the study is based on the cross-sectional approach, which allows the researcher to gather data from a specific location and time. The targeted geographical area of the study is within the UAE. At the same time, the type of research is primary data collection.

2.4. Sampling technique

The current study used a purposive sampling technique. A non-probability sampling in which units are selected based on certain characteristics required for the sample. The researcher collects the data from those teachers that can provide the best information to achieve the study’s objectives. The teachers selected for the study were those who have taught Arabic to kindergarten, grade 1, and special needs children for the past few years.

2.5. Participants

Teachers who participated in the present study teach Kindergarten, grade 1, and special needs children in various schooling systems. Teachers belong to five Emirates of UAE, i.e., Abu Dhabi, Dubai, Fujairah, Sharjah, and Ras Al-Khaimah. 110 teachers were approached from the document provided by the Ministry of Education containing a list of teachers in public and private schools in UAE.

One of the key ethical aspects considered during the research is ensuring participants have free will to participate in this research for this purpose. A dually signed consent form is taken from them. Moreover, permission is also taken from the higher authorities of schools, i.e., principals. School administration assigned a teacher who helped the researcher to begin the recruiting until the required sample size was reached. Of all the questionnaires distributed, those who managed to complete and return them were 80 teachers, accounting for a response rate of 72.7%.

All the teachers involved in this study were from Arabic-speaking countries such as Emirates, Jordan, Egypt, Sudan, and Tunisia. However, all of them were teachers within the Emirates. Based on teachers’ majors, it is worth noting that the teachers who participated in this study were either Arabic teachers or special education teachers. The demographic characteristics of the participants are indicated in Table below.

Table 2. Demographic Characteristics of the Current Study Sample of Teachers (N = 80)

The above table shows that most teachers in the current study have age ranges between 31–40 years. Most of them reside in Dubai and Sharjah. 60% of teachers have Arabic as their major area of education, while 40% are special education teachers. 85% of teachers have a Bachelor’s level of education.

2.6. Instruments

Letter teaching was evaluated with a spreadsheet consisting of 32 letters randomly inserted. Teachers were then asked to demonstrate how they teach Arabic letters in their classrooms. It is worth mentioning how dynamic Arabic letters are in changing shapes based on where they are in a word and any connections they have with any other letter. Teachers were asked to identify the letters that continuously change shape and create problems for learners to remember. Every letter that had different shapes was allocated short vowels above them. By these, the teachers would express how they expected the learners to produce letter sounds instead of letter names. Teachers were also asked how they introduce short vowels against long vowels. Hence, this task included 28 consonant letters within the Arabic alphabet.

2.7. Procedure

The researcher administered all the questions online via email to every participating teacher. Each teacher’s response was evaluated to determine the pattern of answering the questionnaires. Apart from the specific questions, the researcher also interviewed the teachers to get first-hand and in-depth information about the teaching criteria they commonly apply in Arabic letters. The researcher assured the participants to honestly report their teaching methods and strategies and demonstrate how they do it in class. Every participant can leave the interview anytime if they feel uncomfortable. There were no strict criteria for exclusion. Interviews were conducted in the Arabic language as all the teachers were familiar with it.

3. Results

Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS-IBM) was used for data analysis. The data analysis conducted a cross-tabulation of categorical variables and a chi-square test of independence between variables.

3.1. Descriptive statistics

Letter teaching fell between 4 and 23 (M = 18.57, SD = 621), letters sound and shape score was between 0 and 32 (M = 28.49, SD = 14.15), and short vs long vowels from 0 to 19 (M = 14.08, SD = 7.64). The three measures were established to have no significant correlations between letter teaching scoring (r = .33), letters’ sound and shape (r = .25), and vowels (r = .17).

3.2. Ease of pronunciation

The first research question was to investigate whether teachers who adopt ease of pronunciation of letters criteria also start with short vowels and then long vowels. To answer question one, a cross-tabulation analysis below was used for two categorical variables, ease of pronunciation of letters and teachers who begin by introducing short and long vowels.

The above cross table shows that most of the teachers who adopt ease of pronunciation of letters do not start with short and then long vowels. Most teachers start teaching Arabic letters with long vowels instead of short vowels, and the results are indicated in Table below.

Table 3. Ease of Pronunciation of Letters vs Short Vowels and then Long Vowels (N = 80)

3.3. Teacher’s major area of teaching expertise

Teachers’ major was divided into two subcategories, i.e., Arabic teachers and Special education teachers. This constituted the second research question which investigated whether the teachers’ major defines how they introduce letters, sounds, and shapes. An analysis of a cross-tabulation of categorical variables was performed, and the results are indicated in Table below.

Table 4. Teacher’s Major Area of Teaching Expertise vs Introduction to Letter, Sound, and Shape (N = 80)

Above table shows that Arabic and special education teachers follow the same method in introducing and defining sounds, letters, and shapes to young children. Teachers’ major areas of education do not define how they introduce the letters, sounds, and shapes to their students.

3.4. Teachers’ level of education Vs criteria and order

A chi-square test of independence is performed to analyze the relationship between teachers’ level of education and the order or criteria followed by them in Arabic literacy classes. In choosing a chi-square test for independence researcher ensured that the data met two assumptions of non-parametric testing. Verma and Abdel-Salam (Citation2019) state that ensuring that data passes the two assumptions makes using a chi-square test appropriate. The assumptions included that the variables under test were categorical data or measured at the ordinal level and that the level of education comprised several independent variables, and the results are indicated in Table below.

Table 5. Chi-square test of independence between teacher’s level of education and Criteria and order they Use to Teach Arabic Letters (N = 80)

From the chi-square analysis above, the Pearson chi-square value is 1.20. The significance p-value is less than .05, indicating that the chi-square test of independence is non-significant. The null hypothesis is accepted that the teacher’s education level does not determine the criteria and order they use to teach Arabic letters to young students. This suggests a non-significant relationship between the two variables. Thus, the variables of the teacher’s education level (either graduate or master’s) and teaching criteria and order have no significant association.

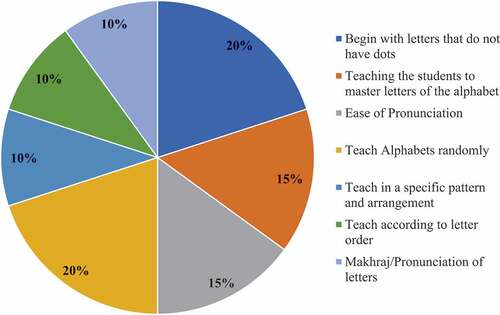

In the order of teaching Arabic letters, the study reflects that most teachers begin with letters that do not have dots while others randomly teach Arabic letters. 20% of the teachers begin teaching letters according to their shape by starting with the letters that do not have dots. These teachers begin with letters that are in the form of a semi-circle and not a full circle since they are easy for visual perception (Dal-Raa’-Lam-Waw د-ر-ل-و). After that, they teach the letters since the beginning of completing the circle is in the letter (“Eain-Haa” ع-ح). The next letter that follows would be (Meem-Haa’ مـ -هـ, and it is circular, there is a similarity between the two letters Meem-Haa’ مـ -هـ - and their opposite is a letter Kafـ - and letter Alif-كـ أ). What follows would be (Seen س, which has three teeth and a half-circle, and then we start with a similar letter Sheen ش by adding dots). After this stage with the letter (Sheen ش), the teachers proceed to teach the letters with dots under the letter, which are as follows (Baa’-Yaa’-Jeem ب - يـ - ج) and then the letters that have a circle and include points such as (Faa’-Khaf ف – ق). Then comes the letter (Taa’ ت and its siblings, which are the following letters (Taa’-Noon- Zain-Khaa’-THal-Thaa’ ت – ن – ث – ذ – خ – ز) and after marking the letters with the upper points, the remaining letters are taught such as (Ssaad-Tt-uh-Ddad-Tthhad ص – ض – ط – ظ), and the results are indicated in Figure above.

Similarly, 20% of the teachers teach letters of the alphabet randomly. This indicated that teaching the alphabet at this stage is conducted randomly. This method is based on a plan issued by the Ministry of Education, and teachers are guided to implement and adhere to it. Some teachers revealed in their assessment that they teach literal lengthening of the letters. At first, the students recognize the sound of the letter (phonemic awareness skill), then the shape of the letter, the position of the letter, the vowels, and the long vowels. Results show that the teaching of letters is done in an unorganized manner. However, letters that are similar in shape follow each other. The order of the letters is as follows:

(ب/ت/ث/ح/خ/ر/ز/ط/ظ/ف/ه/ي/أ/ج/د/ذ/س/ش/ص/ض/ع/غ/ق/ك/ل/م/ن/و)

(Baa’-Taa’-Thaa’-Haa’-Khaa’-Raa’-Zain-tt-uh-Tthhad-Faa’-Haa’-Yaa’-Alif-Jeem-Seen-Sheen-Ssaad-Ddad-‘Eain-Ghain-Khaf-Kaf-Lam-Meem-Noon-Waw).

4. Discussion

The study aimed to investigate the teaching of Arabic letters in kindergarten, grade 1, and special needs centers in the UAE. The study’s primary aim is to explore how teachers start teaching according to the ease of pronunciation of letters and how they introduce short and long vowels in their classrooms. Also, it investigated the relationship between teachers’ majors and how they introduce letter sounds and shapes. Finally, the study tested the null hypothesis that teachers’ education level does not determine the criteria and order they use to teach Arabic. Alrashidi and Phan (Citation2015) went against the argument proposed in the null hypothesis by stating that teachers’ education level determines the criteria and the order to teach Arabic. Maskor et al. (Citation2016) also supported the previous claim by stating that the teacher’s education level and experience play a part in defining their Arabic vocabulary and teaching Arabic. Akasha (Citation2013) also supported the previous argument by stating that teachers’ experience and education level contribute to determining the criteria to help students learn the Arabic language. Austin et al. (Citation2014) also claimed that teachers’ work experiences and educational level in the UAE help strategize their teaching stance and help students learn the Arabic language.

Despite several studies investigating the pronunciation of Arabic letters, few focused on the relationship between ease of pronunciation and the introduction of short and long vowels. Based on the Al-Burāq model of teaching Arabic letters, the present study’s findings revealed that most teachers who adopt the ease of pronunciation of letters start with long rather than short vowels. Also, Al-Busaidi and Al-Saqqaf (Citation2015) argued that among long and short vowels, Arabic teachers prefer to use short vowels to assist the students in learning the Arabic language. The researcher claimed that this approach makes the students learn efficiently. Some Arabic letters present children with pronunciation difficulties. Despite the known problem, a few teachers in the current study seem to prioritize this. The study established that most teachers who adopt ease of pronunciation of letters do not start with short vowels. The short vowels in Arabic are categorized into three: (i) fatha (َa), (ii) damma(ُu), (iii), and kasra (ِi). Those who start teaching with long vowels acknowledge that some sounds of long vowels make it simpler for children to understand. The results contradict other literature by Hackett (Citation2014), which argued that it is effective for teachers to start children with short vowels before the long ones. One of the reasons is that short vowels are the most common for children to interact with the initial stages. Al-Samawi (Citation2014) also researched analyzing the Arabic vowels and the teacher’s role in helping students learn these vowels. The findings also confirmed that they use short vowels more easily than long.

This research further revealed that whether a teacher is an Arabic teacher or a special education teacher does not determine how they introduce letters, sounds, and shapes. However, Jaafar et al. (Citation2014) opine that special education teachers have experience handling students’ problems with sounds, numbers, and letters compared to Arabic teachers who only teach normal students. These teachers can better understand the method through which they can introduce letters.

Similarly, Torana et al. (Citation2010) studied that if special education teachers do not undergo enough training, they are likely to suffer confidence blows and may not effectively introduce letter sounds and shapes to children with autism and other language disorders. Teachers who give clear instructions acknowledge that it is only after a child can quickly identify and name letters that they can effectively learn the sounds and spellings of such letters. The findings are consistent with other research works of Piasta (Citation2014), citing that early learners seem to gain alphabetic knowledge, beginning with letter names, then letter shapes, and finally letter sounds. Jones et al. (Citation2013) also supported the current research findings by stating that early learners are more likely to gain alphabetical knowledge, the shapes of the letters, their discrimination, and their sounds. Labat et al. (Citation2014) also supported the previous argument by stating that teachers prefer to assist the learners based on alphabetic principles that start with teaching the students letter names followed by letter sounds and shapes. Roberts et al. (Citation2018) also dictated that preschoolers prefer alphabet learning to assist learners in learning, followed by letter name and sound instruction. It helps in improving the effectiveness of learning languages. Tibi et al. (Citation2022) added within the previous argument that the learners gain Arabic letter knowledge in Kindergarten by following a certain pattern and helping the students learn the letter’s shape and sound.

5. Conclusion

Major findings of this research state that teachers’ education level does not determine the criteria and order they use to teach Arabic letters. Most teachers in the UAE are bachelor’s degree holders, while a few have master’s degree education. Findings reflect that teachers follow dynamic criteria and order through which they handle their Arabic literacy classes, regardless of their level of education. These findings of our study are not in line with the existing literature, which suggests that teachers’ educational level enhances their teaching effectiveness as it increases teachers’ knowledge in the following order of Arabic letters (Kamaruddin & Patak, Citation2018). In our study, some teachers preferred the ease of letter pronunciation, while others taught the letters randomly. Furthermore, few teachers initiate the teaching process with letters without dots, while some prefer to start with long vowel letters. Piasta (Citation2014) also supported the previous claim by stating that children prefer to get alphabetical knowledge first, followed by other learning stages.

5.1. Implications of the current study

One of the key areas for future studies is the most effective strategies teachers can use to promote Arabic literacy. Based on the study’s results, the unique nature of the Arabic language leads to difficulties during the teaching and learning process. The orthographic nature of the language makes new learners delay gaining the skills they need to read and write the Arabic language. Therefore, in the future, researchers should focus on exploring the most effective teaching strategies that kindergarten teachers can consider to ensure that children can gain Arabic literacy without experiencing many difficulties.

This study comes with some implications for the teaching profession. The current findings can contribute to enlightening instructional practices so that teachers can focus on letters that present difficulties to learners. Teachers can make arrangements to teach these letters separately before handling them in recurring roots and words. Also, when teachers acknowledge the importance of issuing different instructions based on the alphabetical needs of their learners, children will have a strong beginning in acquiring education. This would be more beneficial for children with reading disabilities and dyslexia. These instructional strategies that work in the UAE-based educational systems can be replicated in other countries of the Arab world to support reading acquisition in the early years of a child’s life.

5.2. Suggestions and limitations of the study

This research offers a ground for future researchers based on which further experimental studies can be planned. The sample size for the study was very small; further studies can be planned on the large size to get a more accurate picture of literacy patterns followed by teachers teaching the Arabic language. Comparative studies must be conducted to investigate the teaching criteria followed by the teachers teaching normal children and those with disabilities. Such findings are beneficial in the policy-making and monitoring of educational institutes. Finally, even though there are several criteria and orders for teaching Arabic letters, this study concentrated on a few aspects of this variable. Future studies should be directed toward analyzing more criteria for teaching Arabic letters.

Future research will consider these limitations to enhance the scope of the study. It will consider the involvement of a larger sample size to enhance the generalizability of the study. Also, rather than targeting only UAE, other countries will be considered to imply the findings cross-culturally. It will also consider analyzing more criteria for teaching Arabic letters for better policy-making in educational settings.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to Participant

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The author is very thankful to all the associated personnel in any reference that contributed in/for the purpose of this research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Mahmoud Gharaibeh

Gharaibeh Mahmoud is an assistant professor at Al Ain University in the United Arab Emirates; he has served in various academic works (Assistant Professor, Academic Advisor, Special Education Teacher) and faculty positions for over six years. He teaches courses related to special education and works with accreditation compliance/self-study projects at the university and school levels. He joined many committees at the university. His experience also includes participation in national and international conferences. He has many publications in high-quality Scopus Journals. Dyslexia and Reading Difficulties, Autism and Developmental Disabilities.

Abed Alrazaq Alhassan

Abed Alrazaq Alhassan is an Associate Professor at Al Balqa Applied University-Education Department, Irbid, Jordan; he has served in various academic works (Associate Professor, Academic Advisor, Special Education Teacher) and faculty positions for over 10 years. He teaches courses related to special education and works with accreditation compliance/self-study projects at the university and school levels. He joined many committees at the university. His experience also includes participation in national and international conferences. He has many publications in high-quality Scopus Journals. Education Teachers; Resource Room Learning Difficulties, Educational Supervisors, Associate professor, Member of Jordan Learning Difficulties Center, President of Charitable Society, School Theatre Writer and Director. Ph.D. (Special education) the University of Jordan, Master (special education), Bachelor, Higher Diploma (special education), Diploma. learning disabilities, Autism and Developmental Disabilities.

References

- Abandah, R., & Ansari, S. (2009). Novel moment features extraction for recognizing handwritten Arabic letters. Journal of Computer Science, 5(3), 226–18. https://doi.org/10.3844/jcssp.2009.226.232

- Abu-Chacra, F. (2017). Punctuation and handwriting. Journal of Arabic, 12–16. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315620091-3

- Abu-Rabia, S. (2007). The role of morphology and short vowelization in reading Arabic among normal and dyslexic readers in grades 3, 6, 9, and 12. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research, 36(2), 89–106. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10936-006-9035-6

- Akasha, O. (2013). Exploring the challenges facing Arabic-speaking ESL students & teachers in middle school. Journal of ELT and Applied Linguistics (JELTAL), 1(1), 12–31.

- Al-Busaidi, S., & Al-Saqqaf, A. H. (2015). English spelling errors made by Arabic-speaking students. English Language Teaching, 8(7), 181–199. https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v8n7p181

- Al-Muslim, M., Fadzli Ismail, M., Ab Ghani, S., Nawawi, Z., Abdul Rahman, M., & NazriRostam, M. (2020). What are the features of quality for Arabic teachers agreed by students and teachers?. Journal of Education and E-Learning Research, 7(1), 56–63. https://doi.org/10.20448/journal.509.2020.71.56.63

- Almutiri, S. (2022). A plea for teaching English as second or foreign language through its native speakers’ culture. International Journal of English Linguistics, 11(1), 93–102. https://doi.org/10.5539/ijel.v11n1p93

- Alrashidi, O., & Phan, H. (2015). Education context and English teaching and learning in the kingdom of Saudi Arabia: An overview. English Language Teaching, 8(5), 33–44. https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v8n5p33

- Al-Samawi, A. M. (2014). Vowelizing English consonant clusters with Arabic vowel points (Harakaat): Does it help Arab learners to improve their pronunciation. International Journal of English and Education, 3(3), 263–282. http://ijee.org/yahoo_site_admin/assets/docs/25.184145242.pdf

- Al-Sulaihim, N., & Marinis, T. (2017). Literacy and phonological awareness in Arabic speaking children. Arab Journal of Applied Linguistics, 2(1), 74–90. Retrieved from. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1207977.pdf

- Ariffin, Z., & Al-Muslim, M. (2015). The quality of Arabic language teachers in Malaysia: Facing the fundamental issues. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences. https://doi.org/10.5901/mjss.2015.v6n1p544

- Armbruster, B. B. (2010). Put reading first: The research building blocks for teaching children to read: Kindergarten through grade 3 (Vol. 3). The National Institute for Literacy.

- Arnold, D. S., & Whitehurst, G. J. (1994). Accelerating language development through picture book reading: A summary of dialogic reading and its effect. https://doi.org/10.1177/002221948401701005

- Austin, A. E., Chapman, D. W., Farah, S., Wilson, E., & Ridge, N. (2014). Expatriate academic staff in the United Arab Emirates: The nature of their work experiences in higher education institutions. Higher Education, 68(4), 541–557. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-014-9727-z

- Berninger, V. W., Vaughan, K., Abbott, R. D., Begay, K., Coleman, K. B., Curtin, G., Hawkins, J. M., & Graham, S. (2002). Teaching spelling and composition alone and together: Implications for the simple view of writing. Journal of Educational Psychology, 94(2), 291–304. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.94.2.291

- Blossom, M., & Morgan, J. L. (2006). Does the face say what the mouth says? A study of infants’sensitivity to visual prosody in Proceedings of the 30th Annual Boston UniversityConference on Language Development. Somerville: MA.

- Boudelaa, S., Perea, M., & Carreiras, M. (2020). Matrices of the frequency and similarity of Arabic letters and allographs. Behavior Research Methods, 52(5), 1893–1905. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-020-01353-z

- Castles, A., Rastle, K., & Nation, K. (2018). Corrigendum: Ending the reading wars: Reading acquisition from novice to expert. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 19(1), 93. https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100618786959

- Chomsky, N. (1957). Syntactic Structures. Mouton.

- Coyne, M. D., Simmons, D. C., Kame’enui, E. J., & Stoolmiller, M. (2004). Teaching vocabulary during shared storybook readings: An examination of differential effects. Journal of Exceptionality, 12(3), 145–162. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327035ex1203_3

- Daniels, P. T., & Share, D. L. (2017). Writing system variation and its consequences for reading and dyslexia. Scientific Studies of Reading, 22(1), 101–116. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888438.2017.1379082

- Eviatar, Z., & Ibrahim, R. (2014). Why is it hard to read Arabic? In E. Saiegh-Haddad & R. M. Joshi, Handbook of Arabic Literacy pp. 77–96. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-8545-7_4

- Farhoud, M. A. (2018). The use of Arabic language teachers in smart schools the use of smart board by the Arabic language teachers. M. Alustath Journal for Human and Social Sciences, 227(3), 223–244. https://doi.org/10.36473/ujhss.v227i3.781

- Fender, M. (2008). Spelling Knowledge and Reading Development: Insights from Arab ESL Learners. Reading in a Foreign Language, 22, 19–42.

- Fountas, I. C., & Pinnell, G. S. (2012). Guided reading: The romance and the reality. The Reading Teacher, 66(4), 268–284. https://doi.org/10.1002/TRTR.01123

- Friedmann, N., & Haddad Hanna, M. (2012). Letter position dyslexia in Arabic: From form to position. Behavioural Neurology, 25(3), 193–203. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/296974

- Gregory, L., Taha-Thomure, H., Kazem, A., Bonni, A., Elsayed, M., & Taibah, N. (2021). Advancing Arabic Language Teaching & Learning: A path to reducing learning poverty in the MENA. World Bank Group.

- Grigore, G. (2016). Fuṣḥāarabic VocabularyBorrowed by Mardini Arabic via Turkish. Approaches to the History and Dialectology of Arabic in Honor of Pierre Larcher: Papers in Honor of Pierre Larcher, 435.

- Hackett, J. (2014). Roger Bacon. In Medieval Philosophy of Religion (pp. 151–166). Routledge.

- Hammond, Z. (2013). Culturally Responsive Teaching and the Brain. Corwin.

- Hobbs, R. (2007). Approaches to instruction and teacher education in media literacy. Higher Education Research & Evaluation, 58–64. https://doi.org/10.2307/416059

- Hussien, A. M. (2014). The effect of learning English (L2) on learning of Arabic literacy (L1) in primary school. Journal of International Education Studies, 7(3). https://doi.org/10.5539/ies.v7n3p88

- Ibrahim, R., Khateb, A., & Taha, H. (2013). How does type of orthography affect reading in Arabic and Hebrew as first and second languages? Open Journal of Modern Linguistics, 03(01), 40–46. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojml.2013.31005

- Jaafar, N., Raus, N. M., Muhamad, N. A., Ghazalid, N. M., Amat, R. A., Hassan, S. N., Hashim, M., Tamuri, A. H., Salleh, N. M., & IsaHamzah, M. (2014). Quran education for special children: Teacher as “Murabbi”. Journal of Creative Education, 5(7), 435–444. https://doi.org/10.4236/ce.2014.57053

- Jones, C. D., Clark, S. K., & Reutzel, D. (2013). Enhancing alphabet knowledge instruction: Research implications and practical strategies for early childhood educators. Early Childhood Education Journal, 41(2), 81–89. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-012-0534-9

- Kamaruddin, K., & Patak, A. A. (2018). The role of Islamic education teachers in instilling student discipline. International Journal on Advanced Science, Education, and Religion, 1(2), 15–26. https://doi.org/10.33648/ijoaser.v1i2.9

- Khitam, A. K. (2019). Phonological Dimension of the Arabic Words: The Intimate Relation between Sound and Meaning in the Arabic Words. Arabic: Journal of Arabic Studies, 4(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.24865/ajas.v4i1.147

- Kwaik, K. A. K., Motaz, S., Stergios, C., & Simon, D. (2018). A Lexical Distance Study of Arabic Dialects. The 4th International Conference on Arabic Computational Linguistics UAE . Retrieved on May 2018 from https://pdf.sciencedirectassets.com

- Labat, H., Ecalle, J., Baldy, R., & Magnan, A. (2014). How can low-skilled 5-year-old children benefit from multisensory training on the acquisition of the alphabetic principle? Learning and Individual Differences, 29, 106–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2013.09.016

- Madi, M. (2011). A study of Arabic letter frequency analysis. Retrieved from http://www.intellaren.com/articles/en/a-study-of-arabic-letter-frequency-analysis

- Maskor, Z., Baharudin, H., Lubis, M., & Yusuf, N. (2016). Teaching and Learning Arabic Vocabulary: From a Teacher’s Experiences. Creative Education, 7(03), 482–490. https://doi.org/10.4236/ce.2016.73049

- Miles, K. P., & Ehri, L. C. (2019). Orthographic mapping facilitates sight word memory and vocabulary learning. Reading Development and Difficulties, 63–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-26550-2_4

- Papadopoulos, P. M., Ibrahim, Z., & Karatsolis, A. (2014). Teaching the Arabic alphabet to kindergarteners - Writing activities on paper and surface computers. Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Computer Supported Education, 1, 433–439. https://doi.org/10.5220/0004942204330439

- Piasta, S. B. (2014). Moving to assessment guided differentiated instruction to support young children’s alphabet knowledge. Journal of Reading Teacher, 68(3), 202–211. https://doi.org/10.1002/trtr.1316

- Poyas, Y., & Bawardi, B. (2018). Reading literacy in Arabic: What challenges 1st-grade teachers face. L1 Educational Studies in Language and Literature, 18(Running Issue), 57–70. https://doi.org/10.17239/L1ESLL-2018.18.01.11

- Radan, S. (2016). UAE announces law on reading. Retrieved on February 14, 2018, from Khaleej times: https://www.khaleejtimes.com/nation/government/uae-announces-law-onreading-month-for-reading

- Roberts, T. A., Vadasy, P. F., & Sanders, E. A. (2018). Preschoolers’ alphabet learning: Letter name and sound instruction, cognitive processes, and English proficiency. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 44, 257–274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2018.04.011

- Roskos, K., & Neuman, S. B. (2014). Best practices in reading: A 21st-century skill update. The Reading Teacher, 67(7), 507–511. https://doi.org/10.1002/trtr.1248

- Saiegh–Haddad, E. L. I. N. O. R. (2003). Linguistic distance and initial reading acquisition: The case of Arabic diglossia. Applied Psycholinguistics, 24(3), 431–451. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0142716403000225

- Saiegh-Haddad, E., & Taha, H. (2017). The role of morphological and phonological awareness in the early development of word spelling and reading in typically developing and disabled Arabic readers. Journal of Dyslexia, 23(4), 345–371. https://doi.org/10.1002/dys.1572

- Taha, H. Y. (2013). Reading and spelling in Arabic: Linguistic and orthographic complexity. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 3(5). https://doi.org/10.4304/tpls.3.5.721-727

- Taha-Thomure, H. (2008). The status of Arabic language teaching today. Education, Business and Society: Contemporary Middle Eastern Issues, 1(3), 186–192. https://doi.org/10.1108/17537980810909805

- Tibi, S., Edwards, A. A., Kim, Y. S. G., Schatschneider, C., & Boudelaa, S. (2022). The contributions of letter features to Arabic letter knowledge for Arabic-speaking kindergartners. Scientific Studies of Reading, 26(5), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888438.2021.2016769

- Tibi, S., Fitton, L., & McIlraith, A. L. (2021). The development of a measure of orthographic knowledge in the Arabic language: A psychometric evaluation. Applied Psycholinguistics, 42(3), 739–762. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0142716421000035

- Torana, H., Yasina, M. H. M., Chiria, F., & Tahara, M. M. (2010). Monitoring progress using the individual education plan for students with autism. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 7, 701–706. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.10.095

- Verma, J., & Abdel-Salam, A. (2019). Testing statistical assumptions in research. John Willey & Sons Inc.

- Watson, J. C. (2011). Word stress in Arabic. The Blackwell Companion to Phonology, 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444335262.wbctp0124

- Wiley, R. W., & Rapp, B. (2018). From complexity to distinctiveness: The effect of expertise on letter perception. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 26(3), 974–984. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-018-1550-6

- Willingham, D. T. (2015). Raising kids who read: What parents and teachers can do. Jossey Bass Ltd.

- Yassin, R., Share, D. L., & Shalhoub-Awwad, Y. (2020). Learning to spell in Arabic: The impact of script-specific visual-orthographic features. Journal O fFrontiers in Psychology, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.02059

- Zidouri, A. (2010). On multiple typeface Arabic script recognition. Research Journal of Applied Sciences, Engineering and Technology, 2(5), 428–435. Retrieved from. https://www.academia.edu/download/68429216/On_Multiple_Typeface_Arabic_Script_Recog20210731-13675-1e7wp4v.pdf