Abstract

The hidden curriculum has proven to be a challenging concept to understand and define. However, it remains an integral part of the curriculum within higher education. The literature reviewed addresses the development and different perspectives of the hidden curriculum. Specific focus was given to the hidden curriculum in private higher education, as the hidden curriculum is subjective and situational. The curriculum as the foundation of the hidden curriculum, the influence of the world of work as well as the lecturer on the hidden curriculum were further dimensions that were considered, to enable a conceptual framework of the hidden curriculum in private higher education. The conceptual framework was developed by making use of a concept mapping methodology. The conceptual framework outlines the interplay of different elements on the hidden curriculum, thereby demonstrating the relational and dynamic nature of the hidden curriculum. The framework also identifies the need for further research to enable a more holistic understanding of the hidden curriculum within private higher education.

Public interest statement

The hidden curriculum is an ever-present concept within the higher education setting. Within the classroom setting, it constitutes teachings that students are exposed to over above the formal curriculum. The hidden curriculum has the potential to shape students’ development of skills, values, and competencies. However, lecturers are often unaware of the notion of the hidden curriculum, and their (often) implicit ‘teaching’ thereof. Therefore, the hidden curriculum’s potential (and power) is often overlooked. This article uncovers the hidden curriculum, in specifically the private higher education setting. The aim of the article is to make the hidden curriculum less implicit, demonstrate its importance and value, in hopes of moving towards a more deliberate implementation of the hidden curriculum in higher education.

Introduction

Students often learn more from teaching (and the educational setting) than the subject-related knowledge that they are required to learn (Dewey, Citation1916, Citation1938; Hongmei, Citation2019; Nahardani et al., Citation2022). We have often reflected on what students are taught, over and above subject knowledge. Even though the hidden curriculum (Jackson, Citation1968) seems present throughout all levels of education (Ahola, Citation2000; Jones & Young, Citation1997; Margolis, Citation2001; Pitts, Citation2003; Sambell & McDowell, Citation1998; Semper et al., Citation2018), it has been a concept that has remained challenging to define and understand (Koutsouris et al., Citation2021; Thielsch, Citation2017). Preliminary reading and informal conversations with colleagues highlighted that many lecturers do not know that the hidden curriculum exists (a notion also supported by Bitzer & Botha, Citation2011; Pitts, Citation2003; Semper et al., Citation2018). More concerning is that such lecturers then also do not know what they potentially teach their students through the hidden curriculum.

The hidden curriculum exists of values, norms, and beliefs, amongst others, that are not documented or part of the official teaching, but that students are exposed to in the classroom (Uleanya, Citation2022). A hidden curriculum is a tool that should be utilised in the development of skills and competencies in students—skills and competencies that they need to enter the workforce (Gray, Citation2016; James, Citation2018). The hidden curriculum furthermore aids in the development of social and emotional learning (Maynard et al., Citation2022). The hidden curriculum, therefore, needs to be conceptualised properly to be understood and harnessed deliberately by lecturers in their teaching, which does not currently seem to be the case. The hidden curriculum can furthermore be used to help students develop over and above the formally taught curriculum so that they can develop into employable graduates and contributing citizens of society.

Kujawska-Lis and Lis-Kujawski (Citation2005), in their study on the hidden curriculum in private higher education, states that the hidden curriculum should be referred to per institution, keeping in mind that institutions function in a given time and place, among given people. The hidden curriculum can be analysed through discovering and interpreting various aspects of educational practices within institutions. It is therefore relevant to consider the public or private (non-public) nature of the institution, as the institutional goals might differ. The aim of a private higher education institution is financial gain through selling educational services, it participates in a market system and competes for “clients” with public higher education institutions (Kujawska-Lis & Lis-Kujawski, Citation2005).

The first step to utilise the hidden curriculum effectively in private higher education is to have a better understanding of what the concept entails. In this study, literature was reviewed to understand the origins of the concept of the hidden curriculum and how it has developed over time, as well as the different factors that influence the hidden curriculum. The hidden curriculum is highly flexible and contextual, and the definition and enactment of the hidden curriculum often differ from the time and location that it was enacted (Margolis, Citation2001; Nahardani et al., Citation2022; Thielsch, Citation2017). Given the situational nature of the hidden curriculum, it was appropriate to adopt a process of concept mapping to enable the development of a conceptual framework of the hidden curriculum in private higher education (Maxwell, Citation2013). The objective of the study, therefor, was to uncover the hidden curriculum through creating a visual representation of the conceptual framework of the hidden curriculum that can be used to provide a simple, accessible overview; something that was found lacking in the current literature on the hidden curriculum. The framework forms a useful conceptual tool for future empirical research, to further support and inform a more holistic understanding of the hidden curriculum within specifically private higher education.

Methodology

Concept mapping, introduced by Trochim (Citation1989), was used to develop the conceptual framework. According to Maxwell (Citation2013), concept mapping enables the development and clarification of theory through organising and representing ideas stemming from a specific concept (the hidden curriculum) (Machado & Amélia Carvalho, Citation2020; Rosas & Kane, Citation2012); that ultimately enables the development and presentation of a conceptual framework (Conceição et al., Citation2017; Maxwell, Citation2013).

The first step in the preparation of a concept map is to decide on an appropriate research question to ultimately enable the developed conceptual framework to answer the research question (Vaughn et al., Citation2017). Given that the hidden curriculum has proven to be a challenging topic to define and understand (Koutsouris et al., Citation2021; Thielsch, Citation2017), the research question for creating the conceptual framework was:

What does the existing literature tell us about the hidden curriculum, specifically the teaching of the hidden curriculum within private higher education?

The meaning created in the concept map is subjective, seeing as that concept maps are created in response to understanding a particular phenomenon (Wilson et al., Citation2016). Maxwell (Citation2013) outlines the process to follow when developing a concept map. Below is the approach that was adopted for this study:

In accordance with Wilson et al. (Citation2016), the main concepts relevant to the study were generated. Reference was made to the literature reviewed and the key concepts on the hidden curriculum (discussed above) to help identify the key ideas in the literature. The main concepts are developed by using the main ideas that would come to mind when discussing the topic with another person.

Once the main concepts were generated, it was questioned how these concepts are related. The overlapping circles represent the interplay between concepts or events. There was a constant reflection regarding what the overlaps between concepts stand for.

Different ways of putting the concepts and arrows together were brainstormed. The diagram can be done by hand or through computer programs as stated by Conceição et al. (Citation2017). Draft versions of the concepts were drawn by hand, before building it manually on a computer programme (Microsoft PowerPoint).

The links between concepts can represent several things, and the meaning thereof is not distinguishable by just looking at the map (Bal et al., Citation2010). A narrative or memo of the concept map was therefore adopted to clarify and interpret the map properly (Maxwell, Citation2013).

There are possible limitations when developing a conceptual framework. Becker (Citation2007) cautions that using existing literature to develop a conceptual framework can easily lead to misrepresentations in the way that the research is framed, as well as certain conceptualisations and implications being overlooked by the researcher. Researcher subjectivity (Conceição et al., Citation2017) is present with the identification of key concepts and the establishment of relationships between the concepts as it is all dependent on the researcher’s perspective. Possible limitations were addressed in this study by providing a narrative to the developed conceptual framework and outlining what the overlaps between the concepts represent. The current contextual framework meant that private higher education and the lecturer element of the hidden curriculum are the dimensions that were focused on when relevant literature was consulted.Footnote1

Identifying the key concepts of the hidden curriculum

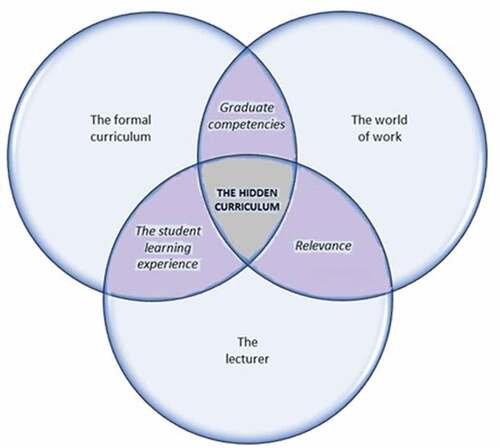

Relevant concepts that were considered to enable the concept mapping and the presentation of a conceptual framework (Figure ), were the curriculum as the foundation of the hidden curriculum, the development of the hidden curriculum, the world of work as an influence on the hidden curriculum, as well as the lecturer influence on the hidden curriculum. The various concepts discussed below, assisted to identify and understand the hidden curriculum and the position thereof within specifically private higher education.

The curriculum

The notion of curriculum incorporates a wide variety of concepts (Mgqwashu, Citation2016) that is centred on the totality of the student experience that occurs within the educational context (Kelly, Citation2009; Pinar, Citation2004). The term “curriculum” has its origins in Latin and can be translated as a “course to be run” (Bitzer & Botha, Citation2011, 60) or more figuratively, a journey of learning (Ross, Citation2000). The term curriculum was first used by the University of Glasgow in 1633 to refer to the intended “course of study” and developed to describe the complete course of study and particular courses and their content (Kennedy, Citation2018). A curriculum is broadly regarded as what is worth experiencing, doing, and being (Parkay & Hass, Citation2000), therefore a curriculum is “what counts as valid knowledge” (Bernstein, Citation1975: 85). Tyler (Citation1949) structured the notion of a curriculum as the mechanism that addresses the needs, concerns, and objectives of the educational leaders and communities within which they work. Taba (Citation1962) and Schwab (Citation1969) extended the notion of the curriculum to also incorporate philosophical and psychological perspectives; the curriculum being regarded as a social and political activity that requires judgement and action.

A curriculum exists to shape society and should serve the public good, it reflects the relations between education and society; and led to human nature being introduced as a focal point in curriculum planning (Costandius & Bitzer, Citation2015; Young, Citation1971). Bernstein (Citation2000) summarises that a curriculum is determined by certain choices in a specific educational setting. A curriculum is therefore contextual and must always be interpreted within a specific ideological process (Smith, Citation2000). Ideology refers to a set of ideas, beliefs, and values that emerge from an identified interest group (Barthes, Citation2018; Bovill & Woolmer, Citation2019). White (Citation1983) pointed out that there is no ideologically and politically innocent curriculum, and that any curriculum definition is inextricably linked to issues of social class, culture, gender, and power (Barthes, Citation2018; Bitzer & Botha, Citation2011).

Researching, understanding, and thinking critically about the curriculum is therefore crucial (Barnett, Citation2009; Council on Higher Education CHE, Citation2016; Shay, Citation2015), as it is no different in thinking about the kind of world we want to bring about, and the kind of student development that would be fitting for such a world (Bitzer & Botha, Citation2011). A curriculum forms the bridge between education and the world of work and is understood to be an educational vehicle that promotes student development (Barnett, Citation2009). However, the curriculum remains a concept that is hard to define (Pitts, Citation2003; Smith, Citation2000).

Furthermore, the curriculum has been a contested topic within higher education in recent times, there have been continuous discussions regarding curriculum transformation (Shay, Citation2015; Barnett, Citation2009; Mkabile-Masebe, Citation2017; Mgqwashu, Citation2016; Le Grange, Citation2016; Hall & Smyth, Citation2016) and the need for a curriculum to remain relevant in terms of what it proposes to achieve. A curriculum in higher education needs to constantly develop, transform and address the existing inequality in higher education as a curriculum is a channel that enables effective response to the ever-changing needs of students and society (Bovill & Woolmer, Citation2019; Department of Higher Education and Training, Citation2014; Shay, Citation2015). A curriculum should aim to be relevant, responsible, accessible, and appropriately scaffolded (Shay, Citation2015), as well as developing appropriate employability skills (Speight et al., Citation2013). Certain other pressures also currently exist on the formal curriculum: social relevance, sustainable development, the impact of the Fourth Industrial Revolution on learning, responsiveness to the world of work, and incorporating the need for entrepreneurship education (Department of Higher Education and Training Citation2017; Lange, Citation2017). In a South African context, a curriculum should aim to contribute to the education and holistic development of students (Bitzer & Botha, Citation2011; Mgqwashu, Citation2016). Studying consists of more than subject knowledge; students are instrumental in the process of knowledge building (Bovill & Woolmer, Citation2019), the obtaining of higher-order skills (Green et al., Citation2009), and the development of values (Mckimm & James Barrow, Citation2009). Barnett (Citation2009) argues that a curriculum should consist of a culmination between knowledge and skills. However, a third aspect in any curriculum is required, that of a student being and becoming. A curriculum should enable students to build their identity (Lange, Citation2017) to enable them to participate as responsible and contributing citizens in society, the economy, and political life (Hall & Smyth, Citation2016). It is evident that a curriculum is a complex system consisting of many elements. The curriculum should aim to create understandings and practices that initiate life-long learning. A curriculum, therefore, has far-reaching applications over and above that of subject-related knowledge, and it is noticeable that some aspects of curriculum development in students might go unnoticed or be hidden. A curriculum is not only what is written on paper, but also involves where and how it plays out on the ground (Bitzer & Botha, Citation2011). It is, therefore, crucial to distinguish between the curriculum as approved by an institution, and the curriculum as experienced by the student (Barnett, Citation2009; Le Grange, Citation2016; Bovill & Woolmer, Citation2019).

The hidden curriculum

In the late 20th century, global institutional transformation led to the uncovering (and increased importance) of the hidden curriculum, whereby the curriculum can sometimes unintentionally convey messages and specifically support inequalities such as race, class, and gender (Costandius & Bitzer, Citation2015). Bitzer and Botha (Citation2011) refer to the hidden curriculum as the element of the curriculum that is the difference between what is formally included in curriculum documents and policies and what is happening during classroom interaction. The hidden curriculum has developed extensively in terms of the understanding of the concept. One feature that has become clear is that the hidden curriculum is an irreplaceable component of the curriculum, and a valuable resource in teaching and learning (Hongmei, Citation2019). The curriculum is therefore an important starting point in the understanding of the hidden curriculum. The curriculum is a determining factor in the student learning experience and social relationships that exist within the learning environment. The student learning experience and social relationships within the classroom are regarded as the conceptual origin of the hidden curriculum (Dewey’s (Citation1938) principle of experience). The way the curriculum plays out in the classroom is what creates and develops the hidden curriculum. Yet the hidden curriculum continued to incorporate a broad range of ideas (Kentli, Citation2009), and there is no consensus on the exact definition of the term (Semper et al., Citation2018). It is, therefore, necessary to consider the origins and development of the concept, as well as the influence that various factors have on the experience and understanding of the hidden curriculum. Literature reviewed enabled the presentation of a conceptual framework of the hidden curriculum in private higher education, demonstrating the importance of the various factors influencing our understanding and enactment of the hidden curriculum.

Dewey (Citation1916) explored the broad idea of a hidden curriculum in his book Democracy and Education where he noticed certain patterns evolving and trends developing in public schools. He put forward the view of “collateral learning” and the “principle of experience” (Dewey, Citation1934, Citation1938) holding that what students learn from the formal learning experience is only part of learning (Hongmei, Citation2019). Learning experiences arise not only from the transmission of abstract ideas but also from social relationships (Semper et al., Citation2018). Freire (Citation1970) and Vygotsky (Citation1978) are key advocates of the importance of social relationships in learning. The result of collateral learning is knowledge acquired unconsciously, and the function thereof can sometimes even succeed that of formal learning (Hongmei, Citation2019; Jansen, Citation2018). There are experiences generated during formal learning, such as principles, emotions, attitudes, interests, values, and acquiring the will to learn. It is argued that these skills are timeless and can bring about lifelong learning (Hongmei, Citation2019).

The hidden curriculum, as a concept, was formulated by Jackson (Citation1968) in his book Life in Classrooms, in the secondary school environment, as a response to mass-schooling in the 1950s and onwards that proved to be ineffective in eliminating class, racial, and gender inequalities. Schools seemed to play a role in reinforcing these divides. He argued that education needs to be understood as a socialisation process and that institutional expectations (the hidden curriculum) are equally as important as academic expectations when assessing the demands of school life (Jackson, Citation1968). Jackson (Citation1968) referred to the hidden curriculum as rules and regulations that regulate classroom life. It is evident, however, that the hidden curriculum has its origins in the inequalities and social norms that existed in the school environment.Footnote2 The hidden curriculum was referred to as the way that classroom experience unfolded in practice.

Snyder’s (Citation1971) book The Hidden Curriculum brought about the first inquiry of the hidden curriculum within higher education. Snyder addressed the question of why students turn away from education. He believed that the majority of campus conflict and students’ anxiety was caused by a mass of unstated academic and social norms, that prevented students to develop independently or think creatively. Snyder demonstrated the hidden curriculum to exist, and that it supplements (and often overshadows) the formal curriculum. Snyder’s research convinced him that the hidden curriculum provides the basis for student self-esteem and subsequent career performance, and lecturers play a crucial role. Lecturers’ attitudes towards the role of education (producing daring thinkers or merely producing competent technicians) can have a significant impact on the delivery and experience of the hidden curriculum (Makowski, Citation1971). Thereafter, the concept of the hidden curriculum was quickly taken up by educational scholars to address the issue of the “non-academic functions and effects” of schooling (Martin, Citation1976; Semper et al., Citation2018).

However, the concept of the hidden curriculum was still mainly researched at a primary and secondary school level (Margolis, Citation2001). It was generally assumed that the hidden curriculum mainly existed at the school level since students are younger and when they reach higher education they are already formed in their thinking and behaviour (Semper et al., Citation2018). Bergenhenegouwen (Citation1987) changed this viewpoint and positioned the hidden curriculum as a crucial element of higher education. He defined the hidden curriculum as “what is implied in the principles and organization of the education, and the patterns of communication and interaction in school” (Bergenhenegouwen, Citation1987:535). He refers to the phenomenon of the hidden curriculum as “implicit education”, including everything that is learnt beyond what is considered the official learning result. In higher education, the hidden curriculum can be described as informal and implicit demands of study and study achievements that need to be met (Bergenhenegouwen, Citation1987). These informal and implicit demands relate to skills and qualities that will give students a proper study attitude, good mentality, and scientific outlook. Bergenhenegouwen (Citation1987) explained these informal demands of study as follow:

Intellectual reasoning and logical argumentation: students learn to show a business-like and detached attitude concerning the subjects of study. Study subjects should be raised beyond the students’ worldview and position.

Abstraction: students learn to master theoretical constructions, professional jargon, and abstract concepts. This is the way the subject is taught and often assessed.

Independent thinking: students learn confidence and giving little or no evidence of anxiety, nervousness, or feelings of uncertainty.

Motivation: satisfaction is gained from achieving more and getting better results than others. Achievement fosters competitiveness and a sense of self-esteem.

Several studies since Bergenhenegouwen (Citation1987) recognise the presence and importance of the hidden curriculum at a higher education level (Ahola, Citation2000; Jones & Young, Citation1997; Margolis, Citation2001; Pitts, Citation2003; Sambell & McDowell, Citation1998; Semper et al., Citation2018). For example, in medical education, the hidden curriculum helps shape the moral component (Lempp & Seale, Citation2004; Ssebunnya, Citation2013; Yüksel, Citation2005), the development of humanism (Martimianakis et al., Citation2015), and professionalism (Hafferty & Castellani, Citation2009); while in management education, ethical practices were introduced and promoted by using the hidden curriculum (Blasco, Citation2012; McCabe & Klebe Trevino, Citation1995). In a study on the hidden curriculum in a university music department, it was highlighted that the responsibility of the lecturer goes far beyond the “official” curriculum (Pitts, Citation2003). It is evident that the academic, social, and personal development of students are closely intertwined. Pitts (Citation2003) further states that the development of students through the hidden curriculum should be approached consciously, as existing social norms within education can often prevent independent and creative thinking. It is also clear that the lessons learnt from the hidden curriculum can be a contributing factor to students’ future career performance.

The hidden curriculum enables valuable insights into the implicit aspects of educational settings and encourages insight into the interactional nature of education (Semper et al., Citation2018). The hidden curriculum has proven to be critical to the teaching and learning of values and ideologies (Margolis, Citation2001). Portelli (Citation1993) identified four major meanings of the hidden curriculum concept, including the unofficial or implicit expectations, values, norms, and messages conveyed by school actors; the unintended learning outcomes; the implicit messages stemming from the structure of schooling; and/or the criteria that the students identify as important to meet to be rewarded. The central idea remains that the hidden curriculum is always concerned with expressing a relationship (Semper et al., Citation2018).

The literature reviewed so far points to the hidden curriculum being a highly flexible system, taking on slightly different meanings, depending on the institution and the type of students that it refers to (Margolis, Citation2001; Thielsch, Citation2017). Sambell and McDowell (Citation1998) hold the view that the hidden curriculum is what is implicit and embedded in educational experiences in contrast with the formal statements about the curriculum and the surface factors of educational interactions. At a micro-level, the hidden curriculum is expressed in terms of the distinction between what is meant to happen (what is officially stated in the curriculum), and what lecturers and students do and experience. The hidden curriculum can therefore be understood as the difference between what is explicitly taught in institutions, and the reality of what students learn. In higher education specifically, this can consist of the values and beliefs of the institution and beliefs of the lecturer that are transmitted to the student, thereby affecting what the student learns, over and above the formal curriculum (Uleanya, Citation2022; Winter & Cotton, Citation2012). A similar definition suggests that the hidden curriculum is a side-effect of education, lessons that are learned but not openly intended, such as the transmissions of norms, values, and beliefs conveyed in the classroom and social environment (Kujawska-Lis & Lis-Kujawski, Citation2005); or the “climate” of the classroom (Çengel & Türkoğlu, Citation2016). Through the hidden curriculum, students pick up an approach to living and an attitude to learning.

In one of the few empirical studies on the practice of the hidden curriculum, Gair and Mullins (Citation2001) researched the hidden curriculum experience at a higher education institution in the United States of America. Their research confirmed the wide variety of notions that the hidden curriculum incorporates. Gair and Mullins (Citation2001) identified certain themes regarding the understanding of the hidden curriculum: Firstly, the hidden curriculum is not hidden at all but is enacted effortlessly in the manner that the university functions on a daily basis. This hints at the notion that the hidden curriculum needs to be uncovered deliberately to think about the messages that the institution conveys through the hidden curriculum. Secondly, the physical environment of the university conveys a hidden curriculum, an example being certain architectural structures being regarded to honour certain histories and convey political agendas. Tor (Citation2015) confirms the existence of the hidden curriculum within the physical environment of an institution, an aspect that was also prevalent during the #feesmustfall movement in South Africa (Koutsouris et al., Citation2021; London, Citation2017). Thirdly, the hidden curriculum is mediated through human beings. Semper et al. (Citation2018) confirms this relational nature of the hidden curriculum and the notion that lecturers and students are important role players in the understanding and enactment of the hidden curriculum. Fourthly, certain practices, missions, cultures, perspectives, attitudes and ideologies that are regarded as acceptable in a specific institutional environment. This demonstrates that the hidden curriculum is subjective and should be researched within a specific institutional context. Gair and Mullins (Citation2001) provided important literature to further the understanding of the hidden curriculum, however, there is a need for more current, contextual research on the hidden curriculum. The hidden curriculum is subjective and dynamic, and more recent research can assist in a more holistic understanding of the hidden curriculum. Furthermore, given the hidden curriculum functions per institution, the public or private nature of higher education institutions are relevant to consider, as the structure and the goals of public and private institutions differ

Contextualising the hidden curriculum within private higher education

Martin (Citation1976) presented the idea that there is no universal hidden curriculum, but that the hidden curriculum is subjective and situational. When the defining characteristics of the hidden curriculum (such as setting, learning activities) change, so too will the hidden curriculum. Gair and Mullins (Citation2001) confirm the notion that the hidden curriculum is enacted and experienced in a specific institutional environment and considering a different kind of educational institution provides necessary contextualisation to further the understanding of the hidden curriculum. Kujawska-Lis and Lis-Kujawski (Citation2005), in their study on the hidden curriculum in private higher education, confirm that the hidden curriculum should be referred to per institution, keeping in mind that institutions function in a given time and place, among given people. The hidden curriculum can be analysed through discovering and interpreting various aspects of educational practices within institutions. It is therefore relevant to consider the public or private (non-public) nature of the institution, as the institutional goals differ. The aim of a private higher education institution is financial gain through selling educational services, it participates in a market system and competes for “clients” with public higher education institutions (Chan, Citation2016; Kujawska-Lis & Lis-Kujawski, Citation2005).

The author’s context and therefor the context of this study is that of a lecturer in a private higher education institution. It is practice for the private higher education institution that contextualises this study to appoint lecturers with industry experience in their field, and these lecturers often teach part-time and continue to work in industry whilst lecturing. This provides lecturers in private higher education institutions with a unique opportunity to connect the world of work with the classroom. Part of the vision of the private higher education institution is to develop employable graduates, and it is believed that lecturers with industry experience will assist with the development of graduate competencies, as they are able to bring unique experiences from the world of work into the classroom, a dimension that lecturers within public higher education institution traditionally do not possess Wiranto and Slameto (Citation2021) confirm both the unique use and importance of lecturers with professional experience within private higher education settings.

The world of work influencing the hidden curriculum

Semper et al. (Citation2018) illustrate the current relevance of the hidden curriculum in higher education: Higher education has been an area of focus recently due to the shift being made towards a system of efficiency, standardisation, productivity, and the reproducing of social and economic inequalities (Bennett & Brady, Citation2014; Zajda & Rust, Citation2016). Students are regarded as human capital and curriculum delivery is understood as value-neutral and has become a system of testable knowledge, performable skills, and competencies that are assessed through explicit learning objectives (Lundie, Citation2016; Mark & Peters, Citation2005). Therefore, there has been an increasing aim to standardise the objectives and outcomes of learning, with the result that higher education is being tailored to meet the demands of the labour market (Karseth & Dyrdal Solbrekke, Citation2016; Zajda & Rust, Citation2016). Education then becomes a matter of purely technical transmission of knowledge, and the teacher-student relationship can easily be disregarded or ignored. It is impossible to eliminate the lecturer and the student from the learning equation (Semper et al., Citation2018). The lecturer’s features, experiences and relationships, differences in learning contexts, and the rich diversity of unexpected, “collateral learning” can result from the encounter between lecturer and student (Dewey, Citation1938).

There is a “distance” between education and life, and the hidden curriculum can be used to bridge that distance (Semper et al., Citation2018). A greater focus should be placed on the hidden curriculum: Lecturers should be made aware that their teaching is a personal issue that can assist in building the interpersonal relationship between lecturers and students. Being aware of the hidden curriculum within higher education will also help to achieve the learning outcomes that are relevant and needed (Semper et al., Citation2018). Many aspects of the curriculum are “hidden”, not just in their messages but in their effects; and the responsibility of ensuring that these are sustaining and enhancing students’ confidence, self-esteem, and development are worthy of greater attention (Pitts, Citation2003). To reveal the hidden curriculum is to research it through discovering, analysing, and interpreting various aspects of the educational practices within the institution (Kujawska-Lis & Lis-Kujawski, Citation2005; Tor, Citation2015). To achieve this aim, researchers analyse the teaching processes and look at the policies of higher education institutions (Kujawska-Lis & Lis-Kujawski, Citation2005).

The hidden curriculum is an irreplaceable and valuable resource in teaching and learning. The hidden curriculum is furthermore embedded in all educational experiences. Through the hidden curriculum, students pick up an approach to living and an attitude to learning, which in turns prepare them for the world of work and the development into contributing citizens of society—which can be summarised as the learning experiences being “relevant” and enables students to be prepared for life. From the literature reviewed on the nature and purpose of the hidden curriculum (Ahola, Citation2000; Blasco, Citation2012; Gray, Citation2016; Hafferty & Castellani, Citation2009; Hongmei, Citation2019; James, Citation2018; Semper et al., Citation2018), I propose that there is a relationship between the “world of work” and the “hidden curriculum”. These skills that students need to develop, can furthermore be used to inform the type of hidden curriculum that lecturers teach.

The lecturer influencing the hidden curriculum

The hidden curriculum is transferred in various ways (Portelli, Citation1993). Lecturer conduct is one of the key factors that determine the hidden curriculum (Bitzer & Botha, Citation2011; Hongmei, Citation2019; Knowles, Citation1973; Peters, Citation1966). Material aspects that transmit the hidden curriculum include textbooks, buildings, classroom layout, and campus environment (Tor, Citation2015). The spiritual aspect of hidden curriculum transmission includes ideology, style of study, and lecturers’ educational philosophy, knowledge outlook, values, teaching guidance, and teaching style (Hongmei, Citation2019). The spiritual aspect is determined by the interpersonal relationships between lecturers and students. Lecturers convey social and moral messages through punishment and reward that they set up and by way of the influence that they have (Yüksel, Citation2005). Margolis (Citation2001:106) describes this as lecturers being the “discourse of authority”, an authorised language in itself. Lecturers, therefore, bear pedagogic authority. An example from Tyson (Citation2014) is lecturers that teach students how to speak to others in a polite and respectful tone. It is evident that lecturers play a crucial role in the manifestation of the hidden curriculum and were, therefore, an important dimension to research to enable a more holistic understanding of the hidden curriculum. It is valuable that lecturers should understand the important role they (and the transmission of the hidden curriculum) play in developing their students into daring thinkers.

James (Citation2018), although writing from the school perspective, provides valuable insight into the teaching of the hidden curriculum and that it is essential in developing the necessary graduate competencies. Employers require soft skills such as grit, resilience, self-mastery, communication, and emotional intelligence. Teaching social, emotional, and behavioural skills can provide students with the competencies that they need to be professionally (and personally) fulfilled in the future (James, Citation2018). It is imperative to promote effective teaching (of the hidden curriculum) so that students can be provided with a holistic learning experience (Feng & Wood, Citation2012). Making the hidden curriculum explicit through the mission and vision statement of the institution is not enough (Orón Semper and Blasco 2018), it is necessary to assess the lecturer enactment of the hidden curriculum through lecturer reflection (Smith-Han, Citation2013) and analysing teaching processes. Given the dynamic nature of the hidden curriculum, it is furthermore shaped by lecturers sharing their understanding and experience of the hidden curriculum in their classroom.

Student experiences illustrated that the hidden curriculum consist of attitudes, beliefs, and values that are picked up in class (Ahola, Citation2000). Examples such as enthusiasm, perseverance, time management, and critical thinking were mentioned in the research. The hidden curriculum furthermore seems to draw attention to what higher education students are expected not just to “do” but most importantly to “be” (Koutsouris et al., Citation2021). The hidden curriculum, therefore, impacts the student learning experience and the social relationships that exist in the learning environment, and that in turn informs and extends our understanding of the hidden curriculum. Through the skills that were mentioned, the lecturer also has the potential to utilise the hidden curriculum to develop much-needed graduate competencies to prepare students for life and enabling them to become contributing citizens to society (Gray, Citation2016; James, Citation2018).

Mapping the hidden curriculum in private higher education

As literature demonstrated above, hidden curriculum in the context of private higher education is built on the overlap between the interplay between the formal curriculum, the world of work, and the lecturer as the catalyst between these core elements that influence the enactment and experience of the hidden curriculum. The relational and reciprocal nature of the hidden curriculum is demonstrated as the hidden curriculum is dynamic, subjective, and often takes on slightly different meanings depending on the time and place it is enacted. The hidden curriculum is made visible through students’ learning experiences through the lecturer’s enactment of the formal curriculum. The hidden curriculum provides the teaching of relevant skills through the lecturer’s understanding and experience of the world of work (which is emphasised in private higher education as described in the contextualisation provided above). The development of graduate competencies is a key component of the hidden curriculum, and the development of graduate competencies is supported when the formal curriculum and the world of work meet in a meaningful way (as enacted by the lecturer’s input and industry experience that is unique to private higher education institutions). Figure illustrates that if there is a balanced harmony between these different elements within a private higher education context, the hidden curriculum can make a meaningful contribution to student learning and development, the development of much-needed graduate competencies, and the lecturer’s teaching experience/professional development. This furthermore demonstrates the importance of uncovering and enacting the hidden curriculum within different educational settings. The conceptualising of the hidden curriculum (Figure ) is presented below:

The hidden curriculumFootnote3 is an irreplaceable element in the enactment of the curriculum, and a valuable resource in teaching and learning. The lecturer forms an integral part of the enactment of the curriculum. Furthermore, the world of work requires students to learn relevant skills and competencies. These skills and competencies can be demonstrated and incorporated into the classroom through hidden curriculum teaching. This illustrates the need to place the hidden curriculum in greater focus in higher education and make the hidden curriculum more explicit within higher education so that the hidden curriculum can be used more deliberately and effectively.

Outward of the hidden curriculum, the shape that is formed between graduate competencies, relevance, and the student learning experience make up the student or student development in higher education. The formal curriculum refers to skills and knowledge that students should attain. These skills and knowledge should aid in the holistic development of students, be relevant, and foster lifelong learning. The world of work is a valuable tool in ascertaining the skills and knowledge that are crucial graduate competencies that students need to successfully enter the workplace. The world of work influences the relevance and responsiveness of the curriculum. There is an identified gap between the world of work and the curriculum, and the hidden curriculum can be used to bridge that gap. The lecturer demonstrates the important role that the lecturer plays, over and above that of the formal curriculum. Lecturers with industry experience are able to identify, demonstrate and teach relevant skills to students through the hidden curriculum. The lecturer forms a central part of the social relationships in the classroom, the “the principle of experience” and overall student development. Lecturers are valuable tools in the teaching of relevant competencies that students require to be professionally and personally fulfilled.

Conclusions

The literature reviewed provided a theoretical framework for the understanding of the hidden curriculum. The context of this study was the hidden curriculum in private higher education. Specific focus was given to the curriculum as the foundation of the hidden curriculum, the hidden curriculum in higher education, the world of work as an influence on the hidden curriculum, and the lecturer as an influence on the hidden curriculum. Reviewing literature on the key concepts of the hidden curriculum enabled me to adopt a process of concept mapping to create a conceptual framework of the hidden curriculum. The conceptual framework (Figure ) illustrates the importance and relevance of the hidden curriculum in a private higher education setting. I argued that the lecturer enactment of the hidden curriculum can develop much-needed graduate competencies to enable students to develop into contributing citizens of society. It is evident that the hidden curriculum can make a meaningful contribution to student learning and development, the development of graduate competencies, and the lecturer’s teaching experience/professional development. The hidden curriculum should therefore be uncovered and harnessed deliberately. Further empirical research on the enactment and experience of the hidden curriculum is necessary to enable a more holistic understanding of the hidden curriculum.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Nina Rossouw

Nina Rossouw Lecturers teach more than the subject content they are required to teach. As John Dewey stated, learning is a social experience that reaches far wider than the formal curriculum. As a lecturer and student in higher education, the potential of the curriculum form part of the key research activities that the author is interested in. Higher education, and the curriculum, can play an integral role in the holistic development of students, if harnessed deliberately. With the recent trend of higher education being more focused on testable knowledge, the development of certain key values and competencies becomes even more relevant and remain important to incorporate into higher education. Furthermore, there has been a growing disparity between higher education and the world of work, and it is argued that the hidden curriculum can be instrumental to remedy this disparity, and to assist in the development of values and competencies.

Notes

1. It should be noted that notions of the hidden curriculum exist throughout educational literature, however, for this study, the focus was on literature that specifically addressed the hidden curriculum in higher education.

2. Literature consulted demonstrated the wide-reaching negative connotation of the hidden curriculum. However, the position has since shifted. The focus of this study was to understand the value that enhanced hidden curriculum awareness can bring to teaching.

3. Terms in italics refer to concepts presented in the framework (Figure ).

references

- Ahola, S. 2000. “Hidden curriculum in higher education: Something to fear for or comply to?” In Innovations in Higher Education Conference., 1–15. Helsinki: University of Turku.

- Bal, A. S., Campbell, C. L., Joseph Payne, N., & Pitt, L. (2010). Political ad portraits: A visual analysis of viewer reaction to online political spoof advertisements. Journal of Public Affairs, 10(4), 313–328. https://doi.org/10.1002/pa.366

- Barnett, R. (2009). Knowing and becoming in the higher education curriculum. Studies in Higher Education, 34(4), 429–440. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070902771978

- Barthes, A. 2018. “The hidden curriculum of sustainable development: The case of curriculum analysis in France.” Journal of Sustainability Education. http://www.susted.com/wordpress/content/the-hidden-curriculum-of-sustainable-development-the-case-of-curriculum-analysis-in-france_2018_04/.

- Becker, H. S. (2007). Writing for social scientists: How to start and finish your thesis, book or article. University of Chicago Press.

- Bennett, M., & Brady, J. (2014). A radical critique of the learning outcomes assessment movement. Radical Teacher, 100(100), 146–152. https://doi.org/10.5195/rt.2014.171

- Bergenhenegouwen, G. (1987). Hidden curriculum in the university. Higher Education, 16(5), 535–543. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00128420

- Bernstein, B. (1975). Class, codes and control: Towards a theory of educational transmission. Routledge.

- Bernstein, B. (2000). Pedagogy: Symbolic control and identity: Theory, research and critique. Rowman & Littlefield.

- Bitzer, E., & Botha, N. (2011). Curriculum inquiry in South African higher education. SUN PRESS. https://doi.org/10.18820/9781920338671

- Blasco, M. (2012). Aligning the hidden curriculum of management education with PRME: An inquiry-based framework. Journal of Management Education, 36(3), 364–388. https://doi.org/10.1177/1052562911420213

- Bovill, C., & Woolmer, C. (2019). How conceptualisations of curriculum in higher education influence student-staff co-creation in and of the curriculum. Higher Education, 78(3), 407–422. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-018-0349-8

- Çengel, M., & Türkoğlu, A. (2016). Analysis through hidden curriculum of peer relations in two different classes with positive and negative classroom climates. Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice, 16(6), 1893–1919. https://doi.org/10.12738/estp.2016.6.0103

- Chan, R. Y. (2016). Understanding the purpose of higher education: An analysis of the economic and social benefits for completing a college degree. Journal of Education Policy, Planning and Administration, 6(5), 1–41.

- Conceição, S. C. O., Samuel, A., Yelich Biniecki, S. M., & Carter, J. (2017). Using concept mapping as a tool for conducting research: An analysis of three approaches. Cogent Social Sciences, 3(1), 1404753. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2017.1404753

- Costandius, E., & Bitzer, E. (2015). Engaging higher education curricula - a critical citizenship perspective. SUN PRESS. https://doi.org/10.18820/9781920689698/03

- Council on Higher Education (CHE). 2016. South African Higher Education reviewed: Two Decades Of Democracy. Council on Higher Education: Pretoria.

- Department of Higher Education and Training. 2014. White paper for post-school education and training.

- Department of Higher Education and Training. (2017). Draft National Plan for Post-School Education and Training. Pretoria.

- Dewey, J. (1916). Democracy and education. MacMillan.

- Dewey, J. (1934). Art as experience. Penguin Publishing Group.

- Dewey, J. (1938). Experience and education. Simon & Schuster.

- Feng, S., & Wood, M. (2012). What makes a good university lecturer? Students’ perceptions of teaching excellence. Journal of Applied Research in Higher Education, 4(2), 142–155. https://doi.org/10.1108/17581181211273110

- Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. The Continuum International Publishing Group Inc. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203891315-58

- Gair, M., & Mullins, G. (2001). Hiding in plain sight. In E. Margolis (Ed.), The hidden curriculum in higher education (pp. 21–41). Routledge.

- Grange, L. L. (2016). Decolonising the university curriculum. South African Journal of Higher Education, 30(2), 216–233. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351061629-14

- Gray, A. 2016. “The 10 skills you need to thrive in the fourth industrial revolution.” World Economic Forum, https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2016/01/the-10-skills-you-need-to-thrive-in-the-fourth-industrial-revolution/.

- Green, W., Hammer, S., & Star, C. (2009). Facing up to the challenge: Why is it so hard to develop graduate attributes? Higher Education Research & Development, 28(1), 17–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360802444339

- Hafferty, F. W., & Castellani, B. (2009). The hidden curriculum: A theory of medical education. In C. Brosnan & B. S. Turner (Eds.), Handbook of the sociology of medical education. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203875636

- Hall, R., & Smyth, K. (2016). Dismantling the curriculum in higher education. Open Library of Humanities, 2(1), 1–28.

- Hongmei, L. (2019). The significance and development approaches of hidden curriculum in college English teaching. Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, 286, 262–265.

- Jackson, P. W. (1968). Life in classrooms. Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

- James, B. D. 2018. “Why you need to know about the ‘hidden curriculum’, and how to teach it.” TES. https://www.tes.com/news/why-you-need-know-about-hidden-curriculum-and-how-teach-it-sponsored-article.

- Jansen, J. 2018. “There’s the CAPS … and then the dangers of SA’s ‘hidden curriculum.’” Daily Dispatch. https://www.dispatchlive.co.za/news/opinion/2018-02-08-theres-the-caps–and-then-the-dangers-of-sas-hidden-curriculum/#.

- Jones, T., & Young, G. A. (1997). Classroom dynamics: Disclosing the hidden curriculum. In A. I. Morey & M. Kitano (Eds.), Multicultural course transformation in higher education: A broader truth (pp. 89–103). Allyn and Bacon.

- Karseth, B., & Dyrdal Solbrekke, T. (2016). Curriculum trends in European higher education: The pursuit of the humboldtian university ideas. In S. Slaughter & B. J. Taylor (Eds.), Higher education, stratification, and workforce development: Competitive advantage in Europe, the US, and Canada (pp. 215–233). Springer International Publishing.

- Kelly, A. V. (2009). The curriculum: Theory and practice. Sixth. SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Kennedy, S. (2018). Educational technology and curriculum. ED-Tech Press.

- Kentli, F. D. (2009). Comparison of hidden curriculum theories. European Journal of Educational Studies, 1(2), 83–88.

- Knowles, M. (1973). The adult learner: A neglected species. Gulf Publishing Company.

- Koutsouris, G., Mountford-Zimdars, A., & Dingwall, K. (2021). The ‘ideal’ higher education student: Understanding the hidden curriculum to enable institutional change. Research in Post-Compulsory Education, 26(2), 131–147. https://doi.org/10.1080/13596748.2021.1909921

- Kujawska-Lis, E., & Lis-Kujawski, A. (2005). Two cheaters’ game. The hidden curriculum in private (non-public) institutions of higher education. In M. Misztal & M. Trawiński (Eds.), Studies in teacher education : Psychopedagogy (pp. 22–30). Wydawnictwo Naukowe Akademii Pedagogicznej.

- Lange, L. (2017). 20 years of higher education curriculum policy in South Africa. Journal of Education, (68), 31–57.

- Lempp, H., & Seale, C. (2004). The hidden curriculum in undergraduate medical education: Qualitative study of medical students’ perceptions of teaching. British Medical Journal, 329(7469), 770–773. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.329.7469.770

- London, T. 2017. “South African universities won’t change unless mindsets start to shift.” The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/south-african-universities-wont-change-unless-mindsets-start-to-shift-71023.

- Lundie, D. (2016). Authority, autonomy and automation: The irreducibility of pedagogy to information transactions. Studies in Philosophy and Education, 35(3), 279–291. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11217-016-9517-4

- Machado, C. T., & Amélia Carvalho, A. (2020). Concept mapping: Benefits and challenges in higher education. The Journal of Continuing Higher Education, 68(1), 38–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/07377363.2020.1712579

- Makowski, A. (1971). The hidden curriculum. The Tech. January 20, 1971. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.331.7524.1056

- Margolis, E. (2001). The hidden curriculum in higher education. (E. Margolis, Ed.). Routledge.

- Mark, O., & Peters, M. A. (2005). Neoliberalism, higher education and the knowledge economy: From the free market to knowledge capitalism. Journal of Education Policy, 20(3), 313–345. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680930500108718

- Martimianakis, M. A., Michalec, B., Lam, J., Cartmill, C., Taylor, J. S., & Hafferty, F. W. (2015). Humanism, the hidden curriculum, and educational reform: A scoping review and thematic analysis. Academic Medicine, 90(11), S5–13. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000894

- Martin, J. R. (1976). What should we do with a hidden curriculum when we find one? Curriculum Inquiry, 6(2), 135–151. https://doi.org/10.1080/03626784.1976.11075525

- Maxwell, J. A. (2013). Conceptual framework. In Bickman, L., Rog, D. (Eds.), Qualitative research design: An interactive approach (pp. 39–72). SAGE Publications Inc.

- Maynard, E., Warhurst, A., & Fairchild, N. (2022). Covid-19 and the lost hidden curriculum: Locating an evolving narrative ecology of schools-in-Covid. Pastoral Care in Education, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/02643944.2022.2093953

- McCabe, D. L., & Klebe Trevino, L. (1995). Cheating among business students: A challenge for business leaders and educators. Journal of Management Education, 19(2), 205–218. https://doi.org/10.1177/105256299501900205

- Mckimm, J., & James Barrow, M. (2009). Curriculum and course design. British Journal of Hospital Medicine, 70(12), 714–717. https://doi.org/10.12968/hmed.2009.70.12.45510

- Mgqwashu, E. (2016). Universities can’t decolonise the curriculum without defining it first. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/universities-cant-decolonise-the-curriculum-without-defining-it-first-63948

- Mkabile-Masebe, B. (2017). Curriculum transformation in higher education : A paradigm shift towards transformative learning. Walter Sisulu University.

- Nahardani, S. Z., Rastgou Salami, M., Hasan Keshavarzi, M., & Mirmoghtadaie, Z. (2022). The hidden curriculum in online education is based on systematized review. Shiraz E Medical Journal, 23(4). https://doi.org/10.5812/semj.105445

- Parkay, F. W., & Hass, G. (2000). Curriculum planning: A contemporary approach (7th editio ed.). Allyn and Bacon.

- Peters, R. S. (1966). Ethics and education. Routledge.

- Pinar, W. F. (2004). What is curriculum theory?. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Pitts, S. (2003). What do students learn when we teach? An investigation of the ‘hidden’ curriculum in a university music department. Arts & Humanities in Higher Education, 2(3), 281–292. https://doi.org/10.1177/14740222030023005

- Portelli, J. P. (1993). Exposing the hidden curriculum. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 25(4), 343–358. https://doi.org/10.1080/0022027930250404

- Rosas, S. R., & Kane, M. (2012). Quality and rigor of the concept mapping methodology: A pooled study analysis. Evaluation and Program Planning, 35(2), 236–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2011.10.003

- Ross, A. (2000). Curriculum: Construction and critique (1st editio ed.). Falmer Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004

- Sambell, K., & McDowell, L. (1998). The construction of the hidden curriculum: Messages and meanings in the assessment of student learning. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 23(4), 391–402. https://doi.org/10.1080/0260293980230406

- Schwab, J. J. (1969). The practical: A language for curriculum. The School Review, 78(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1086/442881

- Semper, O., Víctor, J., & Blasco, M. (2018). Revealing the hidden curriculum in higher education. Studies in Philosophy and Education, 37(5), 481–498. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11217-018-9608-5

- Shay, S. (2015). Curriculum reform in higher education: A contested space. Teaching in Higher Education, 20(4), 431–441. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2015.1023287

- Smith, M. 2000. “Curriculum theory and practice.” The Encyclopedia of Pedagogy and Informal Education. www.infed.org/biblio/b-curric.htm.

- Smith-Han, K. (2013). The hidden curriculum - what else are students learning from your teaching? Akoranga: The Periodical About Learning and Teaching, 21(09).

- Snyder, B. R. (1971). The hidden curriculum. Knopf.

- Speight, S., Lackovic, N., & Cooker, L. (2013). The contested curriculum: Academic learning and employability in higher education. Tertiary Education and Management, 19(2), 112–126. https://doi.org/10.1080/13583883.2012.756058

- Ssebunnya, G. M. (2013). Beyond the hidden curriculum: The challenging search for authentic values in medical ethics education. South African Journal of Bioethics and Law, 6(2), 48. https://doi.org/10.7196/sajbl.267

- Taba, H. (1962). Curriculum development: Theory and practice. Harcourt Brace and World.

- Thielsch, A. (2017). Approaching the invisible: Hidden curriculum and implicit expectations in higher education. Journal for Higher Education Development, 12(4), 167–187. https://doi.org/10.3217/zfhe-12-04/11

- Tor, D. (2015). Exploring physical environment as hidden curriculum in higher education: A grounded theory study. Middle East Technical University. https://doi.org/10.3923/ijss.2017.32.38

- Trochim, W. M. (1989). An introduction to concept mapping for planning and evaluation. Evaluation and Program Planning, 12(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/0149-7189(89)90016-5

- Tyler, R. W. (1949). Basic principles of curriculum and instruction. University of Chicago Press.

- Tyson, C. (2014). The hidden curriculum. Inside Higher Ed. https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2014/08/04/book-argues-mentoring-programs-should-try-unveil-colleges-hidden-curriculum

- Uleanya, C. (2022). Hidden curriculum versus transition from onsite to online: A review following COVID-19 pandemic outbreak. Cogent Education, 9(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2022.2090102

- Vaughn, L. M., Jones, J. R., Booth, E., & Burke, J. G. (2017). Concept mapping methodology and community-engaged research: A perfect pairing. Evaluation and Program Planning, 60, 229–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2016.08.013

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: Development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press.

- White, D. (1983). After the divided curriculum. Victorian Teacher, 12(1), 6–7.

- Wilson, J., Mandich, A., & Magalhães, L. (2016). Concept mapping: A dynamic, individualized and qualitative method for eliciting meaning. Qualitative Health Research, 26(8), 1151–1161. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732315616623

- Winter, J., & Cotton, D. (2012). Making the hidden curriculum visible: Sustainability literacy in higher education. Environmental Education Research, 18(6), 783–796. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2012.670207

- Wiranto, R., & Slameto, S. (2021). Alumni satisfaction in terms of classroom infrastructure, lecturer professionalism, and curriculum. Heliyon, 7(6), e06679. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e06679

- Young, M. (1971). Knowledge and control: New directions for the sociology of education. Collier-Macmilllan.

- Yüksel, S. (2005). Kohlberg and hidden curriculum in moral education: An opportunity for students ’ acquisition of moral values in the New Turkish primary education curriculum. Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice, 5(2), 329–339.

- Zajda, J., & Rust, V. (2016). Globalisation and higher education reforms. Springer.