Abstract

This study looked at the perceptions of the three practicum actors (prospective teachers, placement school teachers (mentors), and teacher educators (tutors) of the primary teacher education practicum program of the Amhara Region, Ethiopia. To that end, a mixed methods approach with a concurrent design was utilized. The quantitative data were collected from randomly selected 799 participants (290 prospective teachers, 252 placement school teachers, and 257 teacher educators) using a survey questionnaire; while the qualitative data were garnered using interviews and focus group discussions from 60 practicum actors. The data were analyzed quantitatively using mean, standard deviation, one sample t-test, and one-way ANOVA and qualitatively using descriptions and narrations. The findings revealed that although teaching practicum is supposed to be an imperative aspect of teacher learning that is instrumental to putting theories into practice, the overall perception of the three practicum actors was lower than the expected level. By far, student teachers’ and placement school teachers’ level of understanding of the basic assumptions of practicum in line with the reflective practitioner model of teacher education was minimal. Knowledge is still considered as transferring from the teacher to students, learning as receiving, and teaching as a process of transferring knowledge. Hence, continuous awareness creation on the basic assumptions of the reflective practitioner model of practicum and its core values is required. Besides, there should be a structure formed carefully of experts in teacher education to lead the program through strong school-college link and collaborative work of the hosting schools and teacher education colleges.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

This study investigated the perceptions of practicum actors in the pre-service primary teacher education practicum program of the Amhara Region, in Ethiopia. Practicum or actual teaching practice is considered the heart of the teacher education system that enables prospective teachers to develop their actual teaching experience and integrate the theory they are learned in the classrooms with the actual school environment. It is also a key instrument to strengthen the college-school linkage when it is properly executed by the joint efforts of the three actors (prospective teachers, teacher educators, and placement school teachers).

Accordingly, for its full implementation, every practicum actor is in need of understanding his/her roles, and valuing the contributions of the practicum is a timely concern. Therefore, this study prompts policymakers, education experts, researchers, teachers, school leaders, the community, and other pertinent stakeholders in the education sector to provide due emphasis for the integrated execution of the practicum program in CTEs and placement schools.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

The issue of assuring quality education has become one of the major agendas across the globe (Smith, Citation2019; Tadesse & Sintayehu, Citation2022; UNESCO, Citation2017). Many nations are exerting their efforts on the quality of education to get the best out of it (Panigrahi, Citation2013; Solomon & Dawit, Citation2020). The quality of education cannot and never be achieved without having well-prepared teachers in pre-service teachers’ education (Amankwah et al., Citation2017; Fekede & Gemechis, Citation2009; Panigrahi, Citation2013). Indeed, the roles of teachers and their professional development have become a crucial factor in determining whether or not the desired educational objectives are to be achieved (Amankwah et al., Citation2017; Azkiyah & Mukminin, Citation2017; Fullan & Hargreaves, Citation2016; Tadesse & Sintayehu, Citation2022). Thus, teachers professional development has become an effective strategy for quality teaching and learning (Reichenberg & Andreassen, Citation2018), and for the improving the varying needs of society (Sachs, Citation2015).

Cognizant of this fact, there have been tremendous debates and agreements among scholars regarding the ways of preparing competent teachers and on the two major components of pre-service teacher education: the theoretical and the practical aspects (Bhattacharya & Neelam, Citation2018; Ministry of Education, Citation2003; Robinson, Citation2019). Although initial teacher education programs have similar features regarding these two major components of teacher education (Bhattacharya & Neelam, Citation2018; Ministry of Education, Citation2003; Robinson, Citation2019), the basic questions of what it means to be a teacher and to learn to be a teacher led to the existence of two contesting models of teacher education—the traditional applied model (TAM) and the reflective practitioner model-RPM (Robinson, Citation2019). These two models of teacher education have also their own underlying assumptions regarding knowledge, learning, and teaching (Fekede & Gemechis, Citation2009; Robinson, Citation2019). Similarly, the earliest scholars (e.g.,Feiman-Nemser, Citation1990; Tom, Citation1997; Zeichner, Citation1996) have also identified conceptual orientation as one of the major points of departure of teacher education in view of teaching, what teachers need to know (knowledge), and the process of learning. Therefore, knowledge, learning, and teaching (KLT) are the core concepts in determining the nature of teacher education (Azkiyah & Mukminin, Citation2017).

The underlying assumptions of the TAM to teacher education are that: (1) theory comes before practice (theory is first learned and then implemented in the practical setting without questioning, integrating, and giving meaning by the learner). (2) giving primacy to academic knowledge, and (3) not integrating theory and practice (Korthagen et al., Citation2006; Robinson, Citation2019; Tadesse, Citation2006, Citation2014). Thus, the TAM of teacher education assumes knowledge as something transferred from a teacher to a learner; learning as a process of receiving what is transmitted from the teacher to the learner; and teaching as a process of transmitting knowledge from the teacher to the learner. According to this model the teaching practice implementers are expected to understand KLT as per the assumption of the model. Teaching practice is also conducted at the end of the academic year after completing all theories of learning without theorizing or integrating the theory they learnt in the classroom and practice they gained at schools (Korthagen et al., Citation2006; Lunenberg & Korthagen, Citation2009; Tadesse, Citation2014). As a result of criticism against this model of teacher education innovative educators have developed new model for preparing teachers with the different theoretical frame for their profession (Bhattacharya & Neelam, Citation2018; Korthagen & Kessels, Citation1999; Tadesse, Citation2006).

Contrary to the traditional apprentice model of teacher education, the reflective practitioner model assumes that: (1) knowledge is constructed by the learner (not transmitted to the learner). (2) learning is a process of constructing knowledge by the learner; and (3) teaching is a process of facilitating learners’ learning (not transmitting knowledge). Within this model, practicum has become one of the major concerns in preparing competent school teachers (Hamaidi et al., Citation2014) and practicum actors (prospective teachers, teacher educators, and placement school teachers) are expected to have an understanding of such assumptions, which are in essence based on the constructivist learning theory (Tadesse, Citation2006). Thus, those practicum actors (henceforth PAs) are expected to have clear conceptual clarity and better understanding about reflective practicum in general and KLT in particular. To make the practicum program effective and efficient, the main actors of the program should have at least closer level of perceptions and understandings (Mulugeta, Citation2009; Tadesse, Citation2014).

It is through such a clear understanding that prospective teachers can integrate theory and practices (Becker et al., Citation2019) and as a result gained firsthand field experiences (Farrell, Citation2008).

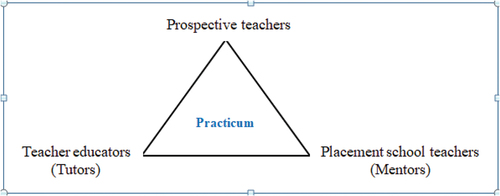

Following the adoption of constructivism in the country’s education system the RPM began to influence the primary teacher education practicum program of Ethiopia to be practiced by the joint efforts of teacher education colleges (CTEs) and placement schools (Dejene et al., Citation2018; Ministry of Education MoE, Citation2009, Citation2011; Mulugeta, Citation2009). As indicated in Figure , the practicum program is designed to be implemented by a triad of PA (Ministry of Education MoE, Citation2011, Citation2021, Citation2022).

To acquaint prospective teachers with the necessary knowledge and skill of teaching and learning, the current structure of the practicum in Ethiopia is designed and provided in four phases (practicum I-IV). The first phase of the practicum named “School Observation” (SO) is designed to provide student teachers with general knowledge of the school experience through focused SO in which prospective teachers are expected to observe the school environment and the classroom teaching-learning process once a week for four weeks in a semester-second year first semester (Ministry of Education MoE, Citation2011). The second phase is “Working under the Mentor” (WUM), and is aimed at enhancing the learners’ understanding of the planning and lesson delivery process along with the evaluation of instructional media. This is a second-year second-semester school experience in which prospective teachers are expected, mainly, to perform two tasks: observing in the class and evaluating materials including textbook (student textbook) evaluation against the evaluation criteria (Ministry of Education MoE, Citation2011). The third phase of the practicum is “Assisting the Mentor” (AM) with the overall objective of providing prospective teachers with practical skills by way of exposing them to important opportunities, such as how classrooms operate, how lessons can be delivered, and how classrooms can be managed (Ministry of Education MoE, Citation2011). The last phase is “Actual or Independent Teaching” (IT)-a third-year second-semester school experience that helps prospective teachers practice the actual teaching in the normal classroom with the preparation of a lesson plan in conjunction with the classroom teacher, but which gradually decreases leading to prospective teachers independent lesson plan preparation. Moreover, in all these phases, prospective teachers are also expected to prepare a portfolio and conduct reflections while teacher educators and placement school teachers are expected to support, provide constructive feedback, and finally make an assessment (Ministry of Education MoE, Citation2011, Citation2015, Citation2020). Therefore, PAs are expected to understand KLT with in line with the assumption of reflective model. This is because their way of understanding will determine the effectiveness of practicum implementation process. In this regard, Azkiyah and Mukminin (Citation2017) investigated that KLT are not only the core issues in determining the nature of teacher education but also key concepts that need to be understood. Graham (Citation2006) indicated that shared understanding is needed among all parties for practicum to be successful. Effective practicum practice is characterized by the tight integration of theory and practice (Darling-Hammond et al., Citation2020; Darling-Hammond, Citation2006; Zeichner, Citation2010) and full support from teacher educators and placement school teachers (Tang, Citation2003) all need shared understanding.

Nevertheless, the execution of the practicum program across the globe has faced several problems including confusion about conceptual clarity by PAs. For instance, a research finding in New Zealand showed that teacher educators and mentors lack shared expectations and understanding of the practicum (Haigh & Tuck, Citation1999). Harrison (Citation2007) and Bradbury and Koblla (Citation2008) identified that one of the significant impediments to successful practicum experiences is a lack of congruence in conceptualizing their respective roles by PA. Similarly, Zeichner (Citation2010) found out that there is still a theory-practice gap due to the continuation of the traditional methods of teaching and as a result the intention of bringing the classroom to the field and the field to the classroom is not materialized. Barone et al. (Citation1996) also have identified the continuation of old and insufficient support to prospective teachers as the challenge of practicum. Therefore, there is a need to investigate the level PAs’ understanding of reflective practicum in primary teacher education program in Ethiopia.

1.2. Problem statement

With the adoption of the constructivist-oriented teacher education program in Ethiopia in 2003, the RPM to teacher education emerged in teacher education programs (Dejene et al., Citation2018; Ministry of Education MoE, Citation2009; Mulugeta, Citation2009) and practicum seems to influence the education system of the country (Hussein, Citation2011; Ministry of Education MoE, Citation2009, Citation2011, Citation2015, Citation2018; Mulugeta, Citation2009). As a result of the introduction of constructivist learning theory, including practicum, the basic assumptions of KLT have also changed over time as opposed to the TAM (Gebeyaw, Citation2022; Ministry of Education, Citation2003; Mulugeta, Citation2009).

Further, practicum was designed as one of the strategies to support teacher education so as to achieve teachers’ competency set in the policy (Fekede, Citation2010). It is also believed that the practical arts of teaching can best be learned from teachers and in schools (Ministry of Education MoE, Citation2011). To that end, among the three major categories of courses that were offered in teacher education programs, the practicum program still has continued in Ethiopia as one major component in the new teacher education curriculum framework ((Citation2018), Citation2020, Citation2021, Citation2022). In line with meeting the assumptions of practicum within the RPM, the responsibility of preparing prospective teachers in Ethiopia has been given to teacher education universities for secondary school and the teacher education colleges for primary and middle schools (Ministry of Education MoE, Citation2011). While teacher education universities are under the control of the Ministry of Education, CTEs are under Regional Education Bureaus (REBs). Thus, it is the responsibility of CTEs to prepare teachers for primary and middle schools considering the respective regional contexts. In the context of the Amhara Region where this study was conducted, delivery of teacher education programs has been given to CTEs under the Amhara Region Education Bureau (AREB).

However, studies in the Ethiopian context revealed that the preparation of qualified teachers in general and the process of practicum implementation, in particular, have not been successful for various reasons (Desta, Citation2018; Ministry of Education MoE, Citation2011, Citation2018; Mulugeta, Citation2009; Tadesse, Citation2006, Citation2019). The findings of Tadesse (Citation2006) explored that there have been problems related to loose school-college links and misconceptions of the basic expectations of practicum within the reflective practitioner model of teacher education. Concerning the misunderstandings of the basic assumptions of practicum, a study conducted by Dejene et al. (Citation2018) designated that prospective teachers joined teacher education programs with a behaviorist orientation. Dawit (Citation2008), (Citation2011), Mulugeta (Citation2009), Rorrison (Citation2011), attributed the issue of poor implementation of practicum to the lack of conceptual clarity among major practicum actors; the poor organization in teacher education programs and schools, and poor program structuring. This implies that the success or failure of the practicum experience is dependent on the perceptions or understandings of its actors.

Given that the practicum within the RPM has become a critical component of the teacher program (Darling-Hammond, Citation2006), it is important to examine the way in which PAs perceive and understand practicum in terms of KLT in the Ethiopian context. Besides, there is a dearth of local research that tries to examine the level of understanding of the basic assumptions of RPM of practicum in Amhara Region CTEs. Consequently, investigating the perceptions of PAs on the basic assumptions of practicum, within an RPM and constructivist theory of learning, vis-à-vis KLT is a timely concern. Therefore, the main purpose of this study was to examine PAs’ perceptions (the way they understand KLT) in CTEs of Amhara Region, Ethiopia. To that end, the following leading questions were raised:

How do practicum actors (prospective teachers, placement school teachers, and teacher educators) perceive the basic assumptions of practicum visa-vise knowledge, learning, and teaching along the reflective practitioner model?

Is there a statistically significant difference among practicum actors in their perceptions of the basic assumptions of practicum along the reflective practitioner model?

2. Literature review

2.1 Conceptions of practicum

The process of preparing competent teachers and practicum has been different for different models of teacher education due to the philosophical underpinnings of these models (Fekede & Gemechis, Citation2009; Tezgiden Cakcak, Citation2015; Tom, Citation1997; Zeichner, Citation1993). Within the RPM practicum-the practical aspect of teacher education is a valuable hands-on professional learning experience and one of the major concerns in preparing competent school teachers (Hamaidi et al., Citation2014; Zeichner, Citation2010). It is vital to bridge the gap between what student teachers have learned in the program and the reality of teaching practice in schools (Darling-Hammond, Citation2006). It provides prospective teachers with relevant practical experiences in teaching by integrating theory and practice (Korthagen et al., Citation2006; Lunenberg & Korthagen, Citation2009; Ulvik & Smith, Citation2011). It also helps prospective teachers to manifest the pedagogical competence they have learned in the classroom (Azkiyah & Mukminin, Citation2017). As the construction of practice knowledge is possible by integrating theory and practice, the purpose of the practicum is to give pre-service teachers opportunities to get acquainted with the practice of their future profession and learn about teachers’ work (Männikkö-Barbutiu et al., Citation2011).

This practicum also permits pre-service teachers to experience diverse teaching systems and exposes them to a variety of teacher roles, school activities, and familiarity with its organizational structure (Maskit & Mevarch, Citation2013). In order to integrate theory and practice, understanding the practicum and its assumptions is vital. Accordingly, there is a need to ensure that practicum is a valuable professional learning experience that needs theoretical understanding and practical engagement in an integrated manner.

Practicum within the RPM has different underpinning assumptions and ways of implementations (Fekede & Gemechis, Citation2009; Tezgiden Cakcak, Citation2015). Scholars have identified conceptual orientation as one of the major points of departure of teacher education program in view of teaching, learning, what teachers need to know (knowledge) and the process of learning to teach (Feiman-Nemser, Citation1990; Tom, Citation1997; Zeichner, Citation1993). Similarly, within the constructivist theory, the reflective practicum assumes KLT very differently from the traditional model (Lunenberg & Korthagen, Citation2009; Robinson, Citation2019). Thus, KLT are not only the core issues in determining the nature of teacher education but they are also key concepts that need to be understood. The basic assumptions of practicum in terms of KLT have become mandatory as the nature of understanding these variables depends on the type of teacher educator model (Tadesse, Citation2006; Tezgiden Cakcak, Citation2015). Within the RPM Knowledge is considered as construction of the learner with his/her way and context (Dewey, Citation1938; Tadesse, Citation2006). Only theoretical knowledge is not enough to prepare competent teachers (Lingam, Citation2004; Williams, Citation1994) implying that construction of knowledge by the learner is critically important and pre-scribed/theoretical knowledge is not enough to prepare effective prospective teachers. Moreover, it is not enough to read about teaching or to observe others teach, as practical knowledge and wisdom are held by the individual (Ulvik & Smith, Citation2011). Similarly, learning is a process of construction of knowledge by the learner, and it is not receiving knowledge from teachers. Teaching is considered as a context-sensitive and creative intellectual activity in which teachers actively seek solutions to their everyday problems; not a routine sequence of pre-determined acts (Dewey, Citation1938). He further distinguished reflective teachers as they are open-minded, responsible, and whole-hearted. Thus, teachers need to be producers of knowledge offering solutions to the problems in their own setting (Zeichner & Liston, Citation1996). They are autonomous decision makers who learn to teach through practicing teaching and reflecting on their practice (Schön, Citation1987). Based on these understandings the present study attempted to investigate PA’s level of understanding of reflective practicum in terms of KLT.

2.2. Practicum actors’ perceptions

Understanding the basic theoretical assumptions of the practicum enables PAs how to use the theory as a powerful tool/frame of reference to analyze critically daily problems for direct application (Gordon, Citation2007). The teaching practicum was grasped as a vigorous facet of teacher learning by the three PAs and the process was felt to be influential to put theories into practice (Chan et al., Citation2019). Thus, during practicum practice, prospective teachers are expected to integrate theoretical knowledge of the institutions with practical knowledge of the hosting schools, through the support of placement school teachers and teacher educators who are expected to support prospective teachers (Tadesse, Citation2014). In order to deliver such practical activities, each PA need to understand what reflective practicum is. Shared understanding among all PAs has been identified as one of the basic elements of the effective practicum implementation process (Graham, Citation2006). Meaning full support from teacher educators and placement school teachers as well as a strong collaborative partnership are also identified as components of effective practicum practices (Darling-Hammond, Citation2006; Graham, Citation2006; Tang, Citation2003).

However, it seems that PAs have limitations in understanding the basic theoretical assumptions of reflective practicum that caused failure to integrate theory and practice during practicum experience (Mulugeta, Citation2009; Rorrison, 2008; Tadesse, Citation2014). Teaching practicum is a real challenge for pre-service teachers because their performance during teaching practicum will foreshadow the future success of the pre-service teachers (Chan et al., Citation2019). Kvernbekk (Citation2001) also emphasized that prospective teachers´ experiences have limitations in inducing a theoretical knowledge search. Further, Gordon (Citation2007) viewed that learners have a widespread misconception on how to put the theory into practice since pre-service teachers are not offered real opportunities to develop their reflective capacity (Mattsson et al., Citation2011).

Similarly, in Ethiopia, there are misconceptions about practicum and its roles by its main actors (Fekede, Citation2010; Ministry of Education MoE, Citation2011) due to the persistence of the TAM of education (Mulugeta, Citation2009). This implies that there has been a mismatch between the intention and reality as Rorrison (Citation2011) found out there has been very little awareness of educational paradigms among actors. Similarly, Graham (Citation2006) indicated that a good practicum needs a shared understanding among all parties. Therefore, the perceptions and understandings of the three practicum actors on the practicum program in line with the reflective practitioner model need to be investigated in terms of KLT.

Thus, to make the practicum program effective and efficient, the main actors of the program should have at least closer perceptions and understandings (Mulugeta, Citation2009; Tadesse, Citation2014). Besides, the program should be guided by clear and transparent criteria and assessment mechanisms that all actors need to have understood equally. Otherwise, the assessors’ (mainly teacher educators and placement school teachers) beliefs, knowledge of the subject, experience and expectation, likes and dislikes seem to impact the assessment of the prospective teachers that would push them to negatively perceive the value of practicum and the teaching profession at large. Consistent with this, Aspden (Citation2017) found that there was a lack of transparency in the expectations of the assessors, assessment criteria, in the judgment of the learning of the prospective teachers as a result of lack of understanding. Tadesse (Citation2014) also investigated the negative feelings prospective teachers developed during their practicum as a result of the ill-treatment and poor mentoring and tutoring they received from their placement school teachers (mentors) and teacher educators (tutors) due to lack of understanding of reflective practicum. Unlike the findings of this study, theoretically, effective practicum practice is considered by the tight integration of theory and practice (Darling-Hammond, Citation2006; Zeichner, Citation2010), in which meaning full support from teacher educators and placement school teachers (Tang, Citation2003) and strong collaborative partnership (Darling-Hammond, Citation2006) all need shared understanding among practicum actors.

3. Theoretical frameworks of the practicum

Teacher training programs across the world place great emphasis on practical training of pre-service teachers aimed to best prepare them for a classroom of students to improve their teaching skills (Hamaidi et al., Citation2014; Saied & Rusu, Citation2022) and their ability to link between theoretical and practical knowledge in order to develop their professional self-efficacy (Gardiner, Citation2011). According to Anderson and Stillman (Citation2013), the practicum is often perceived as the most meaningful component in educational training.

The practicum, as an RPM, is rooted in John Dewey’s reflective thinking of constructivist ideology (Dewey, Citation1910, Citation1938). Reflective thinking is therefore a process of noticing and describing confounding experiences, imagining other possible ways of handling the situation, and finally testing the consequences obtained from the analytical phase in actual practice (Rodgers, Citation2002). Constructivists believe in the existence of multiple realities, which depend on individuals’ own interpretation that in turn is highly informed by his/her background (Alemayehu, Citation2022). According to the constructivists’ theory learners would be given the opportunity to deal with real-life problems during the teaching and learning process, construct knowledge, and integrate theory and practice (Gebeyaw, Citation2022; Mulugeta, Citation2009). Accordingly, the RPM of constructivism also favors the integration of theory and practice (Korthagen et al., Citation2006; Lunenberg & Korthagen, Citation2009).

Constructivism, through which practicum is rooted (Dejene et al., Citation2018; Ministry of Education MoE, Citation2009; Mulugeta, Citation2009) also believes in the construction of knowledge by the learner through his/her active involvement and views learning from the contexts of constructing knowledge through interaction. Therefore, within the RPM, practicum has become one of the major concerns in preparing competent school teachers (Hamaidi et al., Citation2014; Robinson, Citation2019), and the policy documents of Ethiopia have also clearly recognized it as one facet of the country’s teacher education system adapted constructivism philosophy. For instance, in the existing Curriculum Framework for Ethiopian Education (2009) and Education Policy (Ministry of Education MoE, Citation2020), learner experiences are placed at the core of the learning process, and teaching and learning in the existing curriculum is grounded on a constructivist viewpoint.

Thus, the theoretical framework that guided this study was a constructivist theory that views KLT in reflective practicum. Accordingly, the task of integrating theory and practice demands PAs to understand the theoretical part of teacher education in line with the RPM since theory, practical wisdom, and experience are seen in this model as an integrated process of theorizing (Korthagen et al., Citation2006; Lunenberg & Korthagen, Citation2009). Further, the teaching practicum is vital to bridge the gap between what student teachers have learned in the program and the reality of teaching practice in schools (Darling-Hammond, Citation2006), and to provide prospective teachers with relevant practical experiences in teaching (Ulvik & Smith, Citation2011). It is also intended to build prospective teachers’ pedagogical competence by providing opportunities for them to apply knowledge, skills, and values they have learned in the classroom and to act out their theoretical knowledge, and connect theory and practice (Azkiyah & Mukminin, Citation2017).

Accordingly, the RPM has the underpinning conventions of active roles of prospective teachers (Azkiyah & Mukminin, Citation2017; Tvinamuana, Citation2007) and recognizing the value of teaching (Goodwin, Citation2020; Loughran, Citation2006). Such basic issues are implicitly or explicitly related to the type of knowledge a learner should learn; the way she/he should be taught and learned; and the essence of KLT (Robinson, Citation2019). Therefore, these three major issues of teacher education program (KLT) need to be conceptualized by stakeholders of the education realm in general and teacher education practicum in particular.

4. Method

4.1. Approach and design of the study

For this study, a mixed methods approach with a concurrent design was employed in which quantitative data were obtained from the three PAs through questionnaire and qualitative data were also collected from three groups using interviews and FGDs. Mixed methods approaches use procedures for collecting, analyzing and mixing both types of data in a single study (J. Creswell, Citation2014; J. W. Creswell & Creswell, Citation2018; Pallant, Citation2016). Due to its strong power in providing informative, complete, balanced, and useful research results that will help a better understanding of the problem than either quantitative or qualitative designs (Ary et al., Citation2010; J. Creswell & Plano Clark, Citation2007; J. Creswell, Citation2012; Miles & Huberman, Citation1994; Pallant, Citation2016) the researchers have chosen the mixed method approach and the concurrent design.

4.2 Sample of the study

In the Amhara Region of Ethiopia, there are 10 teacher education colleges (CTEs). From these, four CTEs, namely Dessie, Woldia, Debremarkos, and Injibara CTEs, were selected through a simple random sampling technique. Moreover, three placement full-cycle primary and middle schools that are located near each sample CTE (a total of 12 schools) were purposely selected. To choose participants from these institutions, the researchers had obtained lists of people from each organization (4 CTEs and 12 hosting schools) and select participants using simple random sampling techniques after the sample size for each group was decided using the sample size determination table of Krejcie and Morgan (Citation1970). This sampling technique was employed as it allows participants to have equal chance to be included in the study. As can be seen from Table , a total of 918, i.e. 375 (57%) of PTs, 269 (72%) of TEDs, and 274 (44%) of MERs were selected to participate, and questionnaires were distributed. From these, 69 papers were not returned, and 50 others were not qualified to be included in the analysis. But, it was only 799 questionnaires that were properly filled were employed for the data analysis processes.

Table 1. Sample size of respondents

As a result, for the quantitative data, about 799 participants from the three practicum actors, i.e., 257 teacher educators (tutors) (212 males and 45 females) and 290 third-year prospective teachers from different departments of the sample CTEs (220 males and 70 females) and 252 teachers (137 males and 115 females) who were selected through a simple random sampling were included in the study. Third-year prospective teachers were purposely selected over first-year and second-year college students since they passed through the practices of all the four phases of practicum programs.

On the other hand, qualitative data were also collected using interviews and FGDs from purposely selected 60 informants who are believed to have rich information. Consequently, for FGDs 24 (8 from the three groups) participants were included. Similarly, 36 participants of the three groups (12 prospective teachers, 24 school mentors and 24 teacher educators) were participated in interviews. The qualitative data obtained using FGDs and interviews were used to cross-validate results.

4.3 Data collection instruments

For the purpose of this study, the following data collection instruments were employed. Questionnaire: A close-ended survey questionnaire with a total of 14 items (four for knowledge, five for learning the rest five for teaching) was used as main instrument to collect data on the perception of the three practicum actors in the primary teacher education practicum program and its components (KLT). The questionnaire was adapted from the Ministry of Education Practicum Guide (Ministry of Education, Citation2003) which was prepared based on the reflective practitioner approach and by considering global literatures on reflective practicum. It was adapted by considering the national guideline of the country and the review of related literature that focuses on reflective practicum and constructivism. Consequently, items were carefully formulated to measure PAs’ perceptions in terms of the three sub-scales (KLT). The adaptation was made in accordance with the conception of the KLT within a constructivist theory, which is the foundation of the Ethiopian education system. For example, items, such as “knowledge is objective that can be transmitted to learners by the teacher’’ and “Knowledge is acquired when learners are engaged in meaningful activities”’ were formulated to measure PAs perception of knowledge. Items intended to measure PAs’ perception of teaching and learning were also formulated the same way items for knowledge were formulated. To measure learning items such as “learning is listening to what knowledgeable teachers teach” and “learning is integrating theory and practice” were included. To measure teaching items such as “teaching is a process of facilitating students learning by the teacher” and “teaching is a process of transmitting knowledge to the learner by the teacher” were considered.

All of the items were carefully evaluated for their reliability and validity. After the validity and reliability of the instrument was tested, it was finally employed to collect the required data from the three actors. A total of 799 questionnaires for 257 teacher educators, 290 3rd year prospective teachers, and 252 school mentors have responded based on a five likert-scale range from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) that qualify for analysis. The high scores (with a maximum value of 5) represented better perception and low scores (a minimum value of one) indicated poor perceptions. The questionnaire consisted of two sections. Section one is about the demographic variable of respondents and section two focused on perceptions of PAs.

Interviews: Semi-structured interview guides were employed to the three PAs to probe further information about their perceptions of the practicum and its sub-components. Accordingly, 36 information-rich participations (24 teacher educators, 24 school mentors and 12 prospective teachers) were selected through purposive sampling for the interview. The interview guide with five items was prepared and employed. The purpose of using interview was to get further and detail information about actors’ understanding of KLT in line with the assumptions of RPM. The interviews were audio-recorded based on the consent of the informants.

Focus Group Discussions (FGDs): Besides using one-to-one interviews, the researchers also employed FGDs to collect data on the perceptions of PAs about their understanding of reflective practicum and to triangulate with the data collected through other instruments. As Bryman (Citation2012) expounds, FGDs can be used to collect data on the basis of shared understanding from several individuals. Accordingly, in the target CTEs, a group of 24 participants (8 teacher educators) including department heads from six departments (Professional Studies, Natural Science, Social Science, Language, Mathematics, and Aesthetics departments) and 8 school mentors and 8 prospective teachers were involved in FGDs.

4.4. Instrument validity and reliability

4.4.1 Validity

The survey questionnaire, which was adapted to measure the three constructs (KLT), was exposed to different bodies and made to pass through steps for validation. To test the survey items for face and content validity, two university instructors, who have rich professional experiences in teacher education, and one of them carried out his dissertation on practicum have evaluated the instrument. Their comments were carefully organized by the researchers, and major issue was included. Based on the feedback suggested, the researchers attempted to make corrections related to language, item length, and lay out of the questionnaire.

4.4.2 Reliability

Reliability is one of the most important aspects of measurement indicating the consistency of the instruments (Pallant, Citation2016). To that end, the reliability of the survey instrument was conducted with 32 prospective teachers, 25 school mentors, and 30 teacher educators who didn’t participate in the main study. To check the internal consistency of the instrument, Cronbach alpha coefficient was employed and, the overall alpha value of the instrument was 0.87, which is quite reliable and acceptable for the study. Straub et al. (Citation2004); Hinton et al. (Citation2014) and Muijs (Citation2004) suggested that the level of reliability ranging from.70 to .90 and above as high reliability. Such high reliabilities might have been gained as a result of making the instrument clear and simple and the clear orientations on the purposes of the study and respondents familiarity of the constructs (Yallew, Citation2017).

4.5. Techniques of data analysis

In this study, both quantitative and qualitative data analysis techniques were employed. Consequently, to examine the status of PAs’ perceptions on KLT mean, standard deviation, and one sample t-test were used. Moreover, to examine whether there are significant differences among the perceptions of the three PAs in understanding the basic assumptions of practicum, one-way ANOVA was employed. The qualitative data collected through interviews and FGDs were analyzed qualitatively using descriptions and narrations. Finally, both types of analyzed data were integrated and discussed together using a review of related literature and major findings were drawn.

4.6. Ethical considerations

In order to collect data from CTEs and schools, a support letter was given from Bahir Dar University, college of education and behavioral sciences. Based on the given support letter, the researchers collected data from the sample CTEs and schools. The data collected from teacher educators, prospective teachers, and teacher educators were based on the informed consent of the participants and the institutions. Moreover, the interview and FGD data were also recorded using a tape recorder after the researchers received consent from all the respondents. In order to maintain the trustworthiness and confidentiality of respondents, the interpreted qualitative data were coded using letters and numbers.

5. Results

5.1. Practicum Actors’ (PAs) perception of the basic assumptions of practicum

This part of the study presents both quantitative and qualitative results of one of each individual actors and their overall perception.

5.1.1. Results of one sample t-test on overall actors’ perception of practicum

One sample t-test is a statistical hypothesis testing technique in which the mean of a sample is tested against a hypothesized value or population mean. It is used to determine whether the difference between the sample mean (calculated mean) and the hypothesized value of the population mean (expected mean or critical value). In this case, the expected mean value (3.0) is obtained in order to determine whether the responses of the perceptions of the sample PAs are below or above the expected or hypothesized results. Thus, as can be seen from Table , the summarized result of one sample t-test showed that prospective teacher’ and placement school teachers’ perceptions of the basic assumptions of practicum were lower than the hypothesized population mean or expected mean value of 3.0. However, the teacher educators’ result revealed that the overall mean value was found to be average (M = 3.05) which was nearly equal to the average value of the expected mean (3.0). Table , further portrayed that there is a statistically significant difference between the expected mean value and the actual perception mean score of each group. The overall perception of the three actors altogether (prospective teachers, placement school teachers and teacher educators) was also compared and found to be low (M = 2.56), which is below the expected mean value of 3.0.

Table 2. One sample t-test on the overall perception of practicum actors

One sample t-test was also employed to determine the perception of each practicum actor on each subscale about the basic assumptions of practicum along the reflective practitioner model on a one to five scale. The results for each practicum actor’s on each subscale are presented below.

a. Prospective teachers’ perception

The overall perception of prospective teachers about the basic assumptions of practicum was compared with the expected mean of (3.0) using a one-sample t-test. The result showed that the overall mean score of prospective teachers’ perceptions about the practicum program (M = 1.89) was low, compared to the expected mean (t=- 65.68, df = 289, p = .000). Similarly, prospective teachers were also requested to respond to their conceptions about KLT in line with the constructivists’ RPM. Unfortunately, the aggregate result of prospective teachers’ perception of what knowledge means to them (M = 1.81) (t=- 50.50, df = 289, p = .000), what learning is to them (M = 1.69) (t = −49.39, df = 289, p = .000), and what teaching means to them (M = 2.17) (t = −42.56, df = 251, p = .000) were low compared to the expected mean.

In order to further understand PTs’ perceptions about the basic assumptions of the practicum and their level of understanding of KLT interviews and FGD were conducted with prospective teachers. However, the interview reports of PTs indicated that although teaching practicum was seen as an important aspect of teacher learning by prospective teachers in the study, and the process was felt to be instrumental to put integrate theory and practice, prospective teachers’ level of understanding of KLT is still on the traditional teacher-centered approaches. For instance, the interviewed prospective teachers considered knowledge as something to be given by their teachers or objectively transmitted to learners by the teacher. Except for a few prospective teachers that tried to explain KLT along the reflective practitioner model, the spirit of the majority of respondents was to consider knowledge as objective, acquired from pre-defined specific contents and learning as a process of receiving and absorbing knowledge, studying and memorizing concepts, and finally passing paper and pencil exams with good marks

Besides, according to the FGD responses of PTs, in many placement schools they are assigned for practicum, concepts, such as integrating theory and practice construction of knowledge understanding by contextualizing have never been spoken of. Instead, words such as carefully listening to teachers’ teaching, imitating their teaching style, and doing activities to pass to the next level prevail. They are informed by their mentors that teaching is considered as transmitting knowledge, facts, and concepts by the teacher and the role of students is to receive that information. For this, lecturing was mentioned frequently as a strategy prospective teachers would like to apply in classroom teaching practices.

In conclusion, interview and FGD results of prospective teachers showed that although they believed the practicum program is good to improve their actual or practical teaching experiences and school exposure, they didn’t have the expected level of understanding of KLT despite many courses that have been given in CTEs. Generally, what they have tried to explain about the concepts of KLT was related to the traditional model of teacher education, which probably might have come from their previous school experiences and their previous teachers.

b. Placement school teachers’ perceptions

As it can be portrayed in Table , the perception of placement school teachers about the basic assumptions of practicum was low. The one-sample t-test result showed that the mean score of placement school teachers in their perceptions of practicum was low (M = 2.10), compared to the expected mean (3.00) (t=- 42.56, df = 251, p = .000). Looking the sub-scales of reflective practicum Table also portrayed that the mean value of the placement school teachers’ perception of knowledge was 1.95 (t=- 42.53, df = 251, p = .000), learning was 2.09 (t = −42.56, df = 251, p = .000), and teaching was 2.26 (t = −35.75, df = 251, p = .000). This revealed that placement school teachers’ level of understanding of knowledge, teaching, and learning is not in line with the assumptions of the reflective practitioner model.

Table 3. One sample t-test result on the perceptions of the three actors on the sub-scales of practicum

To crosscheck their understandings of KLT, interviews and FGD were also conducted with placement school teachers. The interview results of the majority of the placement school teachers (mentors) showed that placement school teachers have strong belief on the role of practicum to improve PTs knowledge and skill. However, there are misconceptions in their understandings of the basic assumptions of KLT and the practice of practicum in line with the reflective model of teacher education. Almost the majority of placement school teachers tend to view practicum practices in line with the TAM of teacher education. The shared understandings of the participants in the FGD also disclosed similar findings. Their view is still dominated by the teacher-centered teaching approach and viewed knowledge as something to be objectively transferred from the teacher to students, teaching as imparting knowledge, and learning as receiving or absorbing knowledge. As a result of their lack of clear awareness and misconceptions on the purpose of practicum, many placement school teachers consider the assigned prospective teachers as supporters of their program to reduce their teaching loads.

c. Teacher educators’ perceptions

Using one sample t-test, teacher educators’ perceptions and their overall understanding of the KLT were analyzed. The result in Table showed that the overall mean of teacher educators’ perception of the reflective practitioner model of practicum was found to be moderate (3.05) (t = 5.18, df = 256). Nonetheless, the mean score of their perception of what knowledge means was 2.87 (t = −5.01, df = 256, p = .000), whereas the mean score of what learning means to them was found to be 2.95 (t = −2.20, df = 256, p = .029), and teaching 3.32 (t = −5.18, df = 256, p = .000). The results unveiled that although their perceived understanding of what teaching means in line with the constructivist thoughts was relatively higher, their belief and understanding of what knowledge and learning still adhere to the traditional positivist approach.

Data collected through the interview and the FGD also has revealed that the majority of teacher educators have a relatively better understanding of the conceptions of the current practicum. Regarding their conceptions on the KLT, most of the respondents tried to say the words “construction of knowledge”, “facilitating and supporting learning,” and “theory-practice connection” but when researchers posed questions as to how they use them during the instructional process, they tended to use more on the concepts of the traditional applied model. During their interviews, for instance, three of the respondents of teacher educators have the following responses when asked to define practicum:

Practicum is to display the knowledge of prospective teachers to students in schools…it is the way prospective teachers learn much knowledge. When they come to the college they show it practically by applying what they have learned through reflection (NST1, SST2 & MAT1).

Another interviewee (MAT2) mentioned that “for me, practicum means the testing ground of students [prospective teachers] if they have the ability to apply their knowledge from the college. Finally, we give them marks without proper follow-up because we are busy.” The different FGDs conducted with teacher educators also informed that their discussions were not deep rather were at a surface level. Besides, like placement school teachers and student teachers, a significant number of teacher educators also believed that learning is absorbing knowledge from teachers’ delivered information. The discussion also indicated that the proper understanding of theorizing the practicum program was not well understood, and knowledge construction by the learners themselves in their actual working environment [placement schools] is missed.

5.2 Results of one-way ANOVA

A one-way ANOVA comparison between and within in Table disclosed that there was a statistically significant difference among the practicum actors on their the perceptions about the reflective practitioner model of practicum at (F (2, 796) = 1229.55, p = .000) and the effect size calculated using eta squared to see the strength of differences in mean scores between the groups was moderate (0.50).

Table 4. One way ANOVA result comparing the perceptions of practicum actors

To further see the statistically significant difference among the three practicum actors, a Tukey Post-Hoc analysis was made.

The Tukey test result in Table depicted that although the three actors’ mean score is below the expected mean (3.0), the mean scores of placement school teachers (M = 2.00, SD =.252) and prospective teachers (M = 2.02, SD =.293) were low in their perception of practicum and in their understandings of the conceptions of KLT compared to the mean scores of teacher educators (M = 2.00, SD=.252). This result indicated that much remains to be done, particularly on the placement of school teachers and prospective teachers, as well as on teacher educators on their perceptions and understandings of the current practicum program.

Table 5. Mean comparisons of the practicum actors’ perceptions using Tukey Post-Hoc Analysis

6. Discussion

Investigating the level of PAs’ perception of the basic assumptions of the practicum in line with the RPM was the main focus of the study. Although conceptual clarity is an important aspect of reflective practicum and this is reinforced by researchers (e.g., Azkiyah & Mukminin, Citation2017; Bhattacharya & Neelam, Citation2018; Mtika, Citation2011; Robinson, Citation2019; Tadesse, Citation2014), the findings showed that the overall perceptions of the three practicum actors on the practicum program and its basic assumptions along the RPM were low.

Most specifically, prospective teachers and placement school teachers did not properly understand the basic assumptions of the RPM of practicum and as a result, their perception of the relevance of practicum was minimal. In other words, they viewed knowledge as not something constructed by the learner through interacting with the environment, but something to be transferred from the teacher to the learner. They also have the understanding of teaching as a process of transmitting knowledge and learning as receiving information. The qualitative results also proved that practicum actors’ understanding were not fully based on the RPM. They still believed that the teacher-dominated traditional applied model is important and widely applied in schools and CTEs. These findings are consistent with other studies (e.g. Mulugeta, Citation2009) which confirmed that there has been a problem with conceptual clarity by implementers. A study by Mulugeta (Citation2009) and Tadesse (Citation2014) also concluded that major conceptual factors have affected the implementation of the program. Conceptual clarity problems will affect the quality mentoring in placement schools and tutoring in CTEs that will in turn negatively affect prospective teachers’ perceptions of their practicum program. Consistent with this finding, Ulvik and Smith (Citation2011) found that the provision of quality mentoring in terms of appropriate feedback, autonomy, and responsibility given to the prospective teachers, will develop a feeling of inclusion in the school culture among prospective teachers. Practicum is believed to integrate the theory-practice link, however, as Zeichner (Citation2010) revealed, there has been a lack of connection between the university [CTEs] based and field experience due to the academic hierarchy and lack of conceptual clarity. Since, the aim of the practicum is to develop prospective teachers as creative, reflective, vibrant, and dynamic individuals who are aware of the effective teaching and learning processes, the school and community contexts, and the educational values of their learning and practice, a good practicum takes the process beyond the classrooms’ walls to the whole school as a community, and to the exploration of the community all needs understanding the basic conceptions of reflective practicum (Schulz, Citation2005; Tadesse, Citation2019). However, the results of this study proved that the basic assumptions of reflective practicum and the subscales (KLT) were not understood by practicum actors. But, as Azkiyah and Mukminin (Citation2017) KLT are not only the core issues in determining the nature of teacher education but also key concepts that need to be understood.

Although teaching practicum was grasped as a vigorous facet of teacher learning by the three practicum actors and the process was felt to be influential to put theories into practice (Chan et al., Citation2019), the joint work of the three actors, their mutual understanding of the roles of the practicum, and their beliefs on practicum was minimal. The three actors still profoundly relied on the traditional transmissive and teacher-dominated teaching-learning and knowledge transmission processes, which is contrary to the basic assumptions of the current practicum in Ethiopia. Some teacher educators and most prospective teachers and placement school teachers failed to understand that placement schools are true demonstration sites for the prospective graduates to change the theory they have learned in CTEs into practice. Lack of the required level of understanding by practicum actors meant that the way of supporting, tutoring, and follow-up by mentors and teacher educators were not as expected to be

The second finding was related to the statistically significant difference among the three practicum actors’ perceptions in understanding the basic assumptions of practicum. The findings disclosed that placement school teachers and prospective teachers were far below the expected mean in their perceptions of practicum and in their understandings of the conceptions of KLT compared to teacher educators. Although reflective practicum is expected to be practiced by the three actors who have nearly common feelings and understandings about the program, the result indicated deviations in the side of placement school teachers and prospective teachers. This result is consistent with the findings of Mulugeta (Citation2009) who found out that participants of practicum had different levels of beliefs, which proved to be statistically significant indicating that the teacher educators had stronger beliefs about constructivist pedagogy than either the student teacher or the cooperating teachers.

Teaching practicum is a real challenge for pre-service teachers as their performance during this time will foreshadow the future success of the pre-service teachers (Chan et al., Citation2019). However, to make the practicum program effective and efficient, the main actors of the program should have at least closer perceptions and understandings (Mulugeta, Citation2009; Tadesse, Citation2014). Besides, the program should be guided by clear and transparent criteria and assessment mechanisms that all actors need to have understood equally. Otherwise, the assessors’ (mainly teacher educators and placement school teachers) beliefs, knowledge of the subject, experience and expectation, likes and dislikes seem to impact the assessment of the prospective teachers that would push them to negatively perceive the value of practicum and the teaching profession at large. Consistent with this, Aspden (Citation2017) found that there was a lack of transparency in the expectations of the assessors, assessment criteria, in the judgment of the learning of the prospective teachers as a result of lack of understanding. Tadesse (Citation2014) also investigated the negative feelings prospective teachers developed during their practicum as a result of the ill-treatment and poor mentoring and tutoring they received from their placement school teachers (mentors) and teacher educators (tutors) due to lack of understanding of reflective practicum. Similarly, Graham (Citation2006) indicated that a good practicum needs a shared understanding among all parties. Unlike the findings of this study effective practicum practice is considered by the tight integration of theory and practice (Darling-Hammond, Citation2006; Zeichner, Citation2010), in which meaning full support from teacher educators and placement school teachers (Tang, Citation2003) and strong collaborative partnership (Darling-Hammond, Citation2006) all need shared understanding among practicum actors.

7. Conclusions and implications

7.1. Conclusions

Teaching practicum was seen as an important aspect of teacher learning and the process was caressed to be instrumental to put theories into practice. It is also true that an effective practicum is played by a triad of players or actors (prospective teachers, placement school teachers, and teacher educators) who have common awareness and understanding of the program. However, the findings investigated that the overall perceptions/understandings of the three practicum actors were below the expected level, informing that KLT were not understood in line with the RPM.

Looking at each actor’s perception, compared to teacher educators who have an average level of understanding, prospective teachers’ and placement school teachers’ understandings of the current practicum program were low. This reveals that the traditional applied model of teacher education has still dominated their perceptions. That is, knowledge is still considered as transferring from the teacher to students, learning as receiving or absorbing rather than constructing on their own, and teaching as a process of conveying information. As the findings further depicted, the conceptions of the traditional applied model of teacher education have been prevailing over the intended reflective practitioner model of practicum, showing the existence of a clear mismatch between practicum actors’ real understanding and the intention of the practicum program. Accordingly, being overwhelmed by such misunderstanding will have its own negative impact on the practice of practicum. Yet, no attempts were made by concerned bodies to curve such misunderstanding among practicum actors in general and the prospective teachers and placement school teachers in particular.

7.2. Implications

The wider gaps in the perceptions among the three practicum actors will affect the practice and effectiveness of the practicum program in CTEs of the Amhara Region in Ethiopia. Since teaching practicum is seen as an important program in integrating theoretical knowledge with practical knowledge, and develop knowledge about teaching (Shulman, Citation1986), and provide them with relevant practical experiences in teaching (Ulvik & Smith, Citation2011), curving the practicum actors’ beliefs, perceptions and understandings in line with the reflective practitioner model is a timely concern rather than relying on the old model of teaching. Accordingly, to assuage the perception of the practicum actors: (1) There should be a structure formed carefully of experts in teacher education to lead the practicum program through continuous capacity building for all actors and accountability for failure as a result of disregarding the program by all actors. (2) The continuous capacity-building program by all CTEs should be in place and given due emphasis to the extent that practicum actors grasp and well understand the basic assumptions of teacher education programs in general and practicum in particular. (3) At the school cluster level (the existing structure that considers and supports 3–7 schools through a supervisor), there should be a training center for placement school teachers run by an expert or experts to equip them with conceptual clarity and enable them properly support the practicum program. This level of experts will train not only placement school teachers but it will also help prospective teachers and teacher educators in filling the gap caused by conceptual clarity about reflective practicum. (4) In order for the three practicum actors to develop shared understandings and closer perceptions about the purposes of practicum and its assumptions, they have to jointly work among each other and thereby strengthen the college-school links.

8. Limitations of the study

Despite this study employing a mixed methods approach and concurrent design that can help to collect both the quantitative and qualitative data at a time, it should be deliberated in light of some limitations. First, as the current study followed a concurrent design, it has limitations to address the root causes for the low perceptions of the three practicum actors. Second, considering the samples of the study from three different actors may affect the result due to the actors’ differences in their setting and understanding of the practicum. Third, the four phases of the curriculum (school observation, assisting the mentor, working under the mentor and actual teaching) were not treated separately, which should be considered in future studies.

Availability of data and materials

The data sets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author (s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Seid Beshir

Seid Beshir is a Ph.D. Candidate in Curriculum and Instruction at Bahir Dar University, Ethiopia. He has a great interest in conducting research on teacher education, curriculum and teacher professional development.

Asrat Dagnaw Kelkay

Asrat Dagnaw Kelkay is an Associate Professor in the field of Curriculum and Instruction at Bahir Dar University. He has a great interest in conducting research and also published several articles in the field of education, curriculum, and instruction and wants to proceed to publish in those and related fields.

Tadesse Melesse

Tadesse Melesse is an Associate Professor in Education (Curriculum & Instruction) at Bahir Dar University, Ethiopia. His caliber in research made him publish many articles related to differentiated instruction, professional development, school improvement, indigenous knowledge, school climate, curriculum studies, education policy, and teacher education. He further braces his experiences in his future research engagement.

References

- Alemayehu, H. (2022). The effects of citizenship conceptions and pedagogical beliefs on civics and ethical education teachers’ classroom practices in secondary schools of Addis Ababa city ( Ph.D. Dissertation), Bahir Dar University

- Amankwah, F., Oti-Agyen, P., & Sam, F. (2017). Perception of pre-service teachers’ towards the teaching practice programme in college of technology education, University of Education, Winneba. Journal of Education and Practice, 8(4), 13–21.

- Anderson, L., & Stillman, J. (2013). Student teaching’s contribution to pre-service teacher development: A review of research focused on the preparation of teachers for urban and high-needs contexts. Review of Educational Research, 83(1), 3–69. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654312468619

- Ary, D., Jacobs, L., & Sorensen, C. (2010). Introduction to research in education ((8th ed.). Cengage. Learning.

- Aspden, K. (2017). The complexity of practicum assessment in teacher education: An examination of four New Zealand case studies. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 42(12), 128–143. https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2017v42n12.8

- Azkiyah, S., & Mukminin, A. (2017). In Search of teaching quality of EFL student teachers through teaching Practicum: Lessons from a teacher education program. C E P S Journal, 7(4), 105–124. https://doi.org/10.26529/cepsj.366

- Barone, T., Berliner, D., Blanchard, J., Casanova, U., & McGown, T. (1996). A future for teacher education: Developing a strong sense of professionalism. In J. Sikula (Ed.), Handbook of research on teacher education (4th ed., pp. 1108–1149). Macmillan Library Reference USA.

- Becker, E., Waldis, M., & Staub, F. (2019). Advancing student teachers’ learning in the teaching practicum through content-focused coaching: A field experiment. Teaching and Teacher Education, 83, 12–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2019.03.007

- Bhattacharya, S., & Neelam, N. (2018). Perceived value of internship experience: A try before you leap. Higher Education, Skills and Work-Based Learning, 8(4), 376–394. https://doi.org/10.1108/HESWBL-07-2017-0044

- Bradbury, L., & Koblla, J. T. (2008). Borders to cross: Identifying sources of tension in mentor-intern relationships. Teaching and Teacher Education, 24(8), 2132–2145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2008.03.002

- Bryman, A. (2012). Social research methods ((4th ed.). Oxford University Press Inc.

- Chan, G., Yunus, M., & Embi, M. (2019). Beliefs: Quality teaching practicum vs quality teachers. International Journal of Pedagogy and Teacher Education (IJPTE), 3(1), 51–63. https://doi.org/10.20961/ijpte.v3i1.26210

- Creswell, J. (2012). Educational Research. Planning, conducting and evaluating research (4th ed.). Pearson Education, Ltd.

- Creswell, J. (2014). Research Design: Qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approach (4th ed.). SAGE Publications, Inc.

- Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. Sage.

- Creswell, J., & Plano Clark, V. (2007). Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research. Sage.

- Darling-Hammond, L. (2006). Powerful teacher education: Lesson from exemplary programs. Jossey-Bass.

- Darling-Hammond, L., Flook, L., Cook-Harvey, C., Barron, B., & Osher, D. (2020). Implications for educational practice of the science of learning and development. Applied Developmental Science, 24(2), 97–140. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888691.2018.1537791

- Dawit, M. (2008). Reflections on the teacher education system overhaul (TESO) program in Ethiopia: Promises, pitfalls, and propositions. Journal of Educational Change, 9(3), 281–304. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-008-9070-1

- Dejene, W., Bishaw, A., Dagnew, A., & Boylan, M. (2018). Preservice teachers’ approaches to learning and their teaching approach preferences: Secondary teacher education program in focus. Cogent Education, 5(1), 1502396. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2018.1502396

- Desta, G. (2018). Practicum implementation of secondary school mathematics teacher education: Experiences from partner schools of Addis Ababa University ( MA Thesis), Addis Ababa University.

- Dewey, J. (1910). Science as subject-matter and as method. Science, 31(787), 121–127. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.31.787.121

- Dewey, J. (1938). Experience and education. Macmillan.

- Farrell, T. (2008). ‘Here’s the book, go teach the class’ ELT practicum support. RELC Journal, 39(2), 226–241. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033688208092186

- Feiman-Nemser, S. (1990). Conceptual orientations in teacher education. National Center for Research on Teacher Education.

- Fekede, T. (2010). Understanding undergraduate students’ practicum experience: A qualitative case study of Jimma University. Ethiopian Journal of Education and Sciences, 5(1). https://doi.org/10.4314/ejesc.v5i1.56311

- Fekede, T., & Gemechis, F. (2009). Practicum experience in teacher education. Ethiopian Journal of Education and Sciences, 5(1), 107–116. https://doi.org/10.4314/ejesc.v5i1.56316

- Fullan, M., & Hargreaves, A. (2016). Bringing the profession back in. Learning Forward.

- Gardiner, W. (2011). Mentoring in an urban teacher residency: Mentors’ perceptions of yearlong placements. The New Educator, 7(2), 153–170. https://doi.org/10.1080/1547688X.2011.574591

- Gebeyaw, T. (2022). Exploring upper primary school science teachers’ beliefs, self-perceived competences, and classroom practices related to context-based teaching and learning in East Gojjam Administrative Zone ( Ph.D. Dissertation), Bahir Dar University

- Goodwin, A. (2020). Teaching standards, globalization and conceptions of teacher professionalism. European Journal of Teacher Education, 44(1), 5–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2020.1833855

- Gordon, M. (2007). How do I apply this to my classroom? Relating theory to practice. In T. O’ Brien (Eds.), Bridging theory and practice in teacher education (pp. 119–131). Brill.

- Graham, C. (2006). Blended learning systems. The handbook of blended learning: Global perspectives, local designs. Pfeiffer Publishing.

- Haigh, M., & Tuck, B. (1999). Assessing student teachers performance in practicum. Paper presented at the NZARE/AARE Conference, Melbourne, Australia.

- Hamaidi, D., Al-Shara, I., Arouri, Y., & Awwad, F. (2014). Student - teacher’s perspectives of practicum practices and challenges. European Scientific Journal, 10(13), 191–214.

- Harrison, J. (2007). The assessment of ITT standard one, professional values and practice: Measuring performance or what? Journal of Education for Teaching, 33(3), 323–340. https://doi.org/10.1080/02607470701450460

- Hinton, P., McMurray, I., & Brownlow, C. (2014). SPSS explained. Routledge.

- Hussein, J. W. (2011). Impediments to educative practicum: The case of teacher preparation in Ethiopia. Research in Post-Compulsory Education, 16(3), 333–355. https://doi.org/10.1080/13596748.2011.602244

- Kevernbekk, T. (2001). Pedagogy and professionality of teachers. Oslo. Gyldendal.

- Korthagen, F., & Kessels, J. (1999). Linking theory and practice: Changing the pedagogy of teacher education. Educational Researcher, 28(4), 4–17. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X028004004

- Korthagen, F., Loughran, J., & Russell, T. (2006). Developing fundamental principles for teacher education programs and practices. Teaching and Teacher Education, 22(8), 1020–1041. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2006.04.022

- Krejcie, R., & Morgan, D. (1970). Determining sample size for research activities. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 30(3), 607–610. https://doi.org/10.1177/001316447003000308

- Lingam, G. I. (2004). Teacher preparation for the world of work: A study of pre-service primary teacher education in Fiji. Unpublished PhD thesis, Griffith University,

- Loughran, J. (2006). A response to ‘Reflecting on the self’. Reflective Practice, 7(1), 43–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623940500489716

- Lunenberg, M., & Korthagen, F. (2009). Experience, theory, and practical wisdom in teaching and teacher education. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 15(2), 225–240. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540600902875316

- Männikkö-Barbutiu, S., Rorrison, D., & Zeng, L. (2011). Memorable encounters: Learning narratives from pre-service teachers´ practicum. In M. Mattsson, T.V. Eilertson & D. Rorrison (Eds.), A practicum turn in teacher education (pp. 45–66). Brill.

- Maskit, D., & Mevarch, Z. (2013). Another way is possible: Teacher training based on the peer-to-peer model in a professional development sample. Dapim, 56, 15–34.

- Mattsson, M., Eliernsen, T., & Rorrison, D. (2011). A practicum turn in teacher education. Sense publisher.

- Miles, M., & Huberman, M. (1994). In Quantitaive Data Analysis: A Sourcebook of New Methods. SAGE Publication.

- Ministry of Education. (2003). Teacher education system overhaul (TESO) Handbook. MoE, Addis Ababa.

- Ministry of Education (MoE). (2009). Continuous professional development for primary and secondary school teachers, leaders, and supervisors in Ethiopia: The Framework. Ministry of Education.

- Ministry of Education (MoE). (2011). Postgraduate diploma in teaching (PGDT), Practicum Implementation Provisional Guideline. FDRE, Ministry of Education of Ethiopia.

- Ministry of Education (MoE). (2015) . Education sector development programme V (ESDP V): Programme. the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia. Ministry of Education, Addis Ababa.

- Ministry of Education (MoE). (2018) . Ethiopian education development roadmap: An integrated executive summary. Addis Ababa. Ministry of Education.

- Ministry of Education (MoE). (2020) . The new education and training policy (draft). Addis Ababa. Ministry of Education.

- Ministry of Education (MoE). (2021) . Education sector development programme VI (ESDP VI): Programme (2020/21- 2024/25The Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia. Ministry of Education, Addis Ababa.

- Ministry of Education (MoE). (2022) . The new curriculum development framework for general education. Ministry of Education. Addis Ababa.

- Mtika, P. (2011). Trainee teachers’ experiences of teaching practicum: Issues, challenges, and new possibilities. Africa Education Review, 8(3), 551–567. https://doi.org/10.1080/18146627.2011.618715

- Muijs, D. (2004). Doing Quantitative Research in Education with SPSS. Sage Publications. https://doi.org/10.18276/ejsm.2016.20-01

- Mulugeta, T. (2009). Evaluation of implementation of the paradigm shift in EFL teacher education in Ethiopia. Addis Ababa University. http://etd.aau.edu.et/handle/123456789/28311

- Pallant, J. (2016). SPSS Survival Manual (5th ed.). McGraw-Hill Education.

- Panigrahi, R. (2013). Perception of secondary school stakeholders towards women representation in educational leadership in Harari Region of Ethiopia. International Women Online Journal of Distance Education, 2(1), 27–43.

- Reichenberg, M., & Andreassen, R. (2018). Comparing Swedish and Norwegian teachers’ professional development: How human capital and social capital factor into teachers’ reading habits. Reading Psychology, 39(5), 44467. https://doi.org/10.1080/02702711.2018.1464530

- Robinson, M. (2019). Conceptions and models of teacher education. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.013.571

- Rodgers, C. (2002). Defining reflection: Another look at John Dewey and reflective thinking. Teachers College Record, 104(4), 842–866. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146810210400402

- Rorrison, D. (2011). Border crossing in practicum research: Reframing how we talk about practicum learning. In M. Mattsson, T. V. Eilertsen, & D. Morrison (Eds.), A practicum turn in teacher education. Brill.

- Sachs, J. (2015). Teacher professionalism: Why are we still talking about it? Teachers and Teaching, 22(4), 413–425. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2015.1082732

- Saied, J., & Rusu, A. (2022). Theoretical overview of the practicum programs for special education pre-service teachers. In I. Albulescu & C. StanEds., Education, Reflection, Development(v.2).European Proceedings of Educational Sciences, pp. 609–616. European Publisherhttps://doi.org/10.15405/epes.22032.61

- Schön, D. A. (1987). Educating the reflective practitioner: Toward a new design for teaching and learning in the professions. Jossey-Bass.

- Schulz, R. (2005). The Practicum: More than practice. Canadian Journal of Education, 28(1 & 2), 147–167. https://doi.org/10.2307/1602158

- Shulman, L. (1986). Those who understand: Knowledge growth in teaching. Educational Researcher, 15(2), 4–14. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X015002004

- Smith, M. (2019). Sensory integration: Theory and practice. FA Davis.

- Solomon, M., & Dawit, M. (2020). The contribution of placement school experiences to prospective teachers’ multicultural competence development: Ethiopian Secondary Schools in Focus. Journal of Education and Learning, 14(1), 15–27. https://doi.org/10.11591/edulearn.v14i1.14272

- Straub, D., Boudreau, M., & Gefen, D. (2004). Validation guidelines for is positivist research. Communications of the Association for Information Systems, 13. https://doi.org/10.17705/1CAIS.01324

- Tadesse, M.(2006). The practices and challenges of the practicum program. the case of Dessie college of teacher education ( Unpublished Master’s Thesis), Addis Aaba University.

- Tadesse, M. (2014). Assessment on the implementation of the pre-service practicum program in teacher education colleges. Journal of Education and Practice, 5(20), 97–110.