Abstract

Since the outbreak and spread of COVID-19 all over the world, many countries, including China, are taking measures for epidemic prevention and control, and some measures require citizens to provide personal privacy information. In the era of big data, it is worth paying attention to how people view the collection of personal privacy data under the special background that China collects personal information to better fight against the COVID-19 epidemic. In particular, it is of great significance and value to explore the privacy concept of Chinese higher education groups, the most important participants in the era of big data in China. This study focuses on the privacy concept of Chinese higher education groups under the background of COVID-19 epidemic, and higher education groups from 19 provinces, 4 municipalities and 4 autonomous regions are selected as research samples. Through questionnaire survey and statistical analysis, individual privacy sensitivity, individual privacy deliver willingness, individual privacy security and other issues of Chinese higher education groups under the COVID-19 epidemic situation are discussed. And this study tries to explore the influencing factors behind it. It is found that Chinese higher education groups generally have high privacy sensitivity and high perception of privacy risk. However, in the special period of fighting against the COVID-19 epidemic, Chinese higher education groups generally have a high willingness to deliver private information and a high privacy security. In addition, education level, discipline background and parents’ education level are important factors affecting the privacy concept of Chinese higher education groups.

Public Interest Statement

This study focuses on the privacy concept of Chinese higher education groups under the background of COVID-19 epidemic. Through questionnaire survey and statistical analysis, individual privacy sensitivity, individual privacy deliver willingness, individual privacy security and other issues of Chinese higher education groups under the COVID-19 epidemic situation are discussed. And this study tries to explore the influencing factors behind it. It is found that Chinese higher education groups generally have high privacy sensitivity and high perception of privacy risk. However, in the special period of fighting against the COVID-19 epidemic, Chinese higher education groups generally have a high willingness to deliver private information and a high privacy security. In addition, education level, discipline background and parents’ education level are important factors affecting the privacy concept of Chinese higher education groups.

Introduction

Since COVID-19 suddenly broke out and spread rapidly around the world, the economic development, medical system and social stability of all countries in the world have suffered unprecedented and severe challenges. Compared with the previous large-scale infectious diseases, COVID-19 shows stronger transmission, which makes tracking and timely disclosure of the trajectory of infected persons and potential infected persons to the public become an important part of anti-epidemic measures in some countries. And some studies have pointed out that in various measures to deal with COVID-19, the method of using people’s private location data has played an important role (Ekong et al., Citation2020). On the one hand, individuals have the right to be free from unlimited collection, storage, use and transmission of personal data; on the other hand, for the sake of national public security and interests under the epidemic prevention and control, appropriate concession of personal privacy information rights is also the need of the country and society in a special period.

To some extent, under the pressure of fighting COVID-19, the government must readjust its priorities, putting the safety and well-being of the public in the first place, while the privacy of individual data may be forced into an important concession. The most common example is that some governments recognize COVID-19 as a special case, in which sensitive data can be collected to protect public health (Global Privacy Assembly, Citation2020). Some studies have pointed out that in an emergency, even if the measures to prevent and control COVID-19 directly affect the rights and freedoms of individuals, the government is willing and allowed to take extraordinary measures to combat the epidemic; And on the individual level, citizens seem to be turning to protect public health rather than personal privacy (Newlands et al., Citation2020). Although preventive measures such as movement restriction, isolation, closure of public places and schools, and blockade are necessary to control the spread of infectious diseases such as COVID-19, the degree of restriction and access to individual privacy requires ethical justification (Gostin et al., Citation2003). Some countries have issued relevant laws and regulations to ensure that citizens’ privacy information will not be leaked in the process of preventing and controlling COVID-19.

During China’s fight against COVID-19, the active cooperation of Chinese people with the state’s tracking and obtaining of their private information is the key to the success of China’s fight against the epidemic. In the era of big data, under the special background that China collects public personal information to better fight against the COVID-19 epidemic, people’s views on the collection of personal privacy data are worthy of attention, especially the privacy concept of the forefront of new thought——higher education groups. Through questionnaire survey and statistical analysis, this study discussed the privacy sensitivity, privacy deliver willingness, privacy security and other privacy concept issues of Chinese higher education groups under the background of COVID-19, and analyzed the important influencing factors of their privacy concept, in order to fill the research gap and provide some reference for research in related fields.

Literature Review

Research on the Influencing Factors of Privacy Concept

As for the influencing factors of individual privacy concept, the research mainly focuses on the following three aspects. First, the types of privacy information. Some studies have pointed out that people have different sensitivity to social media updates or consumption patterns. For some people, these data are highly private, while for others, they are non-private (Eurobarometer, Citation2011). Second, the purpose of privacy. Some studies have pointed out that people will evaluate the use of privacy data and weigh the benefits that providing privacy data may bring to them. When these benefits are directly related to individuals (such as medical services and business income), most people are willing to share their privacy data with organizations that ask them to provide personal privacy information, but asking for too much data will soon lead to a feeling of being monitored instead of being served (Acquisti et al., Citation2013). Third, who collects privacy. Data from Eurobarometer in 2011 shows that when it comes to the most sensitive data, people all over Europe trust medical institutions and banks the most, while social media and search engines are the least trusted, and sometimes they are even regarded as a threat to individual privacy (BCG Boston Consulting Group, Citation2012). In the current research on privacy concept, generally speaking, gender, age and education level are common demographic factors to explore privacy concept:

Gender-related. Generally speaking, compared with men, women will perceive more potential risks and report more privacy issues. Studies have shown that women are more concerned about information privacy than men. Women are also relatively reluctant to discuss their personal information on the Internet (Fogel & Nehmad, Citation2009). However, some studies have pointed out that although men are more interested in the Internet and have higher computer skills than women, gender has nothing to do with the privacy of electronic information (Chen & Rea, Citation2004).

Age-related. Previous studies have shown that a person’s age will affect his or her privacy (Li et al., Citation2011). There are also studies reporting that age is positively related to privacy issues on the Internet (Janda & Fair, Citation2004). Young people have fewer privacy issues than older people because they are young, often less wealthy, and have not yet established reputations (Chen et al., 2001). As a result, young people take more risks from privacy leaks when making decisions (Ji & Lieber, Citation2010). Some studies focus on personal privacy-related protection behaviors to study the concept of privacy. For example, some studies have studied whether people read company privacy protection policies, and found that age is positively correlated with whether a person reads privacy protection policies (Milne & Culnan, Citation2004).

Education level- related. To some extent, educated people may pay more attention to the protection of privacy. Among the related researches on privacy concepts, some studies have recognized that learning has a positive impact on improving privacy literacy. Some studies have shown that the low level of privacy knowledge is related to the lack of efforts to protect privacy, and it is proved that there is a positive effect between learning privacy-related knowledge and improving one’s privacy literacy (Urban & Hoofnagle, Citation2014). In addition, some studies have explored whether people read the company’s privacy protection policies, and found that people’s education level is negatively correlated with their reading of privacy protection policies (Milne & Culnan, Citation2004).

Research on the Individual Privacy Concept in the Context of COVID-19 Pandemic

Some studies have pointed out that privacy issue is a contextual concept, that is, different backgrounds will produce different privacy issues (Pool et al., Citation2022). And social emergencies such as COVID-19 pandemic have made the traditional “public-private dualism” privacy concept face more severe impact and challenges. The COVID-19 pandemic has led to a rapid increase in the generation, collection, utilization, analysis, storage, distribution, mining, aggregation and transmission of personal data. The outbreak of COVID-19 in the world has created the scene of “boundary turbulence”, the concept of which was first put forward by Petronio in 2002, namely “people are unable to collectively develop, execute, or enact rules guiding permeability, ownership, and linkages” (Petronio, Citation2002). Under the social background of this “boundary turbulence”, the changes of privacy patterns have become more drastic, and the great changes of privacy concepts have followed. A study from South Korea pointed out that there was a privacy paradigm shift after the worldwide COVID-19 pandemic, which included the following four aspects: (1) The diversity and quantity of personal data collection increased significantly; (2) The privacy information is transferred from centralized storage architecture to decentralized/hybrid storage; (3) The dynamic change in the meaning of personal privacy; (4) The change of factors threatening personal privacy security in the health sector; (5) The change of the situation threatening personal privacy security (Majeed & Hwang, Citation2021).

With the change of privacy paradigm, the privacy concept of individuals living in the special social context of the global spread of COVID-19 has also changed to varying degrees. During the special period of COVID-19 pandemic worldwide, tracking programs such as Contact Tracking Mobile Application (CTMA) are widely used to identify and track infected persons and potential infected persons. A study covering almost all of the United States shows that individuals’ intention to install CTMA is influenced by factors such as privacy issues and privacy protection measures, and their high privacy concerns can explain the low utilization rate of CTMA (Hassandoust et al., Citation2021). A study of subjects from France, Australia and the United States shows that during the COVID-19 pandemic, concerns about privacy have slowed the adoption of “contact tracing apps” for smartphones in the three countries (Chan & Saqib, Citation2021). Although some studies have shown that privacy concerns have caused some concern about the implementation of measures to control the COVID-19 epidemic, it is worth noting that some studies also point out that people will weigh personal privacy against issues related to social well-being. A study pointed out that in South Korea, people’s acceptance of most COVID-19 control measures is significantly higher, because the strong collectivist tendency makes South Koreans weigh privacy issues against social well-being, and give priority to public safety, so they have a higher acceptance of COVID-19 control measures (Kim & Kwan, Citation2021).

Research on the Particularity of Higher Education Groups’ Privacy Concept

Nowadays, the value of big data has been discovered by more people, and the protection of individual privacy under the background of big data has attracted more attention. The development history of the Internet in China is relatively short. In the late 1980s, the Internet started in China, and in the late 1990s, the Internet really entered the life of every Chinese people. It can be said that the Internet in China developed and grew together with the current college students. The Internet is an important data source of big data, and college students are the main participants in the Internet era, so college students can be regarded as one of the important groups participating in the era of big data. Studies have pointed out that higher education groups, namely college students, are important beneficiaries and victims of the era of big data (Y. Y. Wang & Liu, Citation2017). Higher education groups have advanced ideas and high acceptance of new things. Compared with other social groups, higher education groups have a higher rate of digital products ownership and a stronger sense of dependence on the Internet and big data, resulting in more attention to the issue of personal data privacy and security. Research on privacy concept of higher education groups has its important group research significance and value.

Through the analysis of previous literature, it can be found that there is still no conclusion on the relationship between the privacy concept and demography. Previous studies rarely discuss the privacy concept of higher education groups, and there is a research gap in the research of privacy concept of higher education groups in the era of big data. In the era of big data, under the special background of the COVID-19 epidemic, discussion of the collection and protection of individual privacy data information is more valuable than ever before. In particular, it is of research significance and value to explore the privacy concept of higher education groups, the most important participants in the era of big data. Therefore, this study focuses on discussing the privacy concept of Chinese higher education groups under the special social background of the global spread of COVID-19, and analyzes its characteristics and causes behind it. In view of this, the following research questions are raised in this study: (1) What about the degree of privacy risk perception among higher education groups in the context of the fight against COVID-19? What about their privacy deliver willingness? What about their privacy security? (2) What factors will affect the privacy concept of higher education groups and their willingness to deliver private information during the COVID-19 pandemic?

Research Method

“Privacy concept” is a subjective measure, and people in different educational levels and social environments have different degrees of cognition and perception of it. The study on the privacy concept of Chinese higher education groups under the COVID-19 epidemic can focus on the measurement dimensions of “personal privacy sensitivity”, “personal privacy information deliver willingness”, “personal privacy security” and so on. The investigation on the potential influencing factors of privacy concept of Chinese higher education groups under the COVID-19 epidemic mainly focuses on the following two objective factors: first, the direct influence of personal factors (educational level, discipline background) on individual privacy concept; the second is the influence of external factors (parents’ education level, major public security events such as the COVID-19 outbreak) on individual privacy concept. This study investigates quantitative data on issues such as privacy risk perception and willingness to deliver privacy information among Chinese higher education groups under the COVID-19 epidemic.

Questionnaire Design

In order to investigate the degree of privacy risk perception of Chinese higher education groups, their willingness to deliver private information and the influencing factors under the COVID-19 epidemic, this study designed and compiled a questionnaire entitled “Survey of Chinese higher education groups’ privacy concept during the COVID-19 epidemic”. The survey selected four research dimensions of individual privacy sensitivity, individual privacy deliver willingness, individual privacy security, and individual privacy concept influence factors. In order to ensure the validity and scientificity of the research, the questionnaire used in the research was compiled on the basis of mature questionnaires in previous studies (Wan & Zhang, Citation2020; Z. Wang & Zhao, Citation2014), according to the characteristics of this research question. The choices of the questions in the questionnaire were given on Likert’s seven-level scale, namely, the scale options were “very consistent”, “consistent”, “relatively consistent”, “general”, “relatively inconsistent”, “inconsistent” and “very inconsistent”. The corresponding score was 7 points, 6 points, 5 points, 4 points, 3 points, 2 points, and 1 point. The more consistent the answer is, the higher the corresponding score is, and the more likely it is to happen. This questionnaire survey was conducted online and offline simultaneously, and data was collected through professional research websites.

Analysis Tools

For the collected valid questionnaires (N = 470), SPSS 23 statistical software was used to process and statistically analyze the collected valid data.

According to the questionnaire designed by the author, the Descriptive Analysis was given to the measurement dimensions such as “individual privacy sensitivity”, “individual privacy deliver willingness” and “individual privacy security” based on Likert’s seven-level scale, and the concentration characteristics and volatility characteristics of the data were calculated. In view of the fact that descriptive analysis is usually used to analyze the basic cognitive situation of scale data, this study attempts to describe the overall privacy concept of Chinese higher education groups during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Meanwhile, in order to understand the potential influencing factors (educational level, discipline background, parents’ education level, etc.) of Chinese higher education groups’ privacy perceptions under the COVID-19 pandemic, Correlation Analysis was used in this study. The influence degree of different variables on individual privacy concept was explored. It mainly analyzes the deterministic relationship between variables, and detects whether there is correlation between two or more variables and the degree of correlation between them. The higher the correlation coefficient between variables, the stronger their correlation is. In this part, Pearson Product-Moment Correlation was used to analyze the correlation among variables.

Sample Selection

Random sampling method was used in this study to select individuals with higher education from 19 provinces, 4 municipalities directly under the Central Government and 4 autonomous regions in China, including junior college students, undergraduates, postgraduates and doctoral students, as research samples to participate in the survey. All the selected subjects volunteered to participate in the survey.

The sample selection of this study comprehensively considered the differences and representativeness of the regions and educational backgrounds of the subjects. A total of 500 questionnaires were distributed and collected, of which 470 were valid, with an effective rate of 94.00%. The demographic structure of the sample is shown in the following table (see Table ).

Table 1. Sample demographics

Research Hypothesis

H1:

Chinese higher education groups generally have high privacy sensitivity and high perception of privacy risk.

H2:

In the special period of the fight against the COVID-19 outbreak, Chinese higher education groups generally have a high willingness to deliver their privacy information.

H3:

In the special period of the fight against the COVID-19 outbreak, Chinese higher education groups have a high privacy security.

H4:

The privacy sensitivity of Chinese higher education groups is greatly influenced by their parents’ education level.

H5:

The willingness of Chinese higher education groups to deliver privacy information is influenced by education level, discipline background and parents’ education level.

Research Findings

Privacy Sensitivity of Higher Education Groups

This study makes a statistical analysis of the constituent dimensions of privacy concepts in the survey samples, and the statistical results of individual privacy sensitivity is shown in the following table (see Table ).

Table 2. Individual privacy sensitivity of subjects

Regarding the question of “in the information society, some concession of personal privacy is required in exchange for living convenience”, the views held by the subjects are shown in the following table (see Table ).

Table 3. Views of exchange personal privacy for living convenience

As shown in the table, there are only 8 subjects who said that they didn’t notice the phenomenon that “in the information society, some concession of personal privacy is required in exchange for living convenience”, accounting for only 1.70%, which shows that this phenomenon has been widely noticed by the public, and the number of subjects who expressed “worry” about this phenomenon is much higher than that who expressed “happiness”. The proportion of “worried” samples in the research samples is close to 70%, which shows that the public is cautious and sensitive about this issue to a large extent.

The research results show that higher education groups generally pay high attention to privacy and have high privacy sensitivity, indicating that Chinese higher education groups have a high perception of privacy risk in the special period of the fight against the COVID-19 outbreak.

Privacy Deliver Willingness of Higher Education Groups

Regarding the question of “whether there is a change in the perception of personal data privacy after the outbreak of COVID-19”, the views held by the subjects are shown in the following table (see Table ).

Table 4. Views of personal data privacy after the outbreak of COVID-19

As shown in the table, more than 70% of the subjects said that the COVID-19 outbreak changed their views on the privacy of their personal data. Among the changes, 41.49% of the subjects said that the privacy of personal data needs to be compromised to a certain extent when public security is involved, another 31.70% of the subjects said that they were more convinced than before that personal data belonged to personal property and needed to be respected and protected.

Regarding the attitude of “the government needs citizens to provide certain personal information to facilitate the prevention and control of the COVID-19 epidemic”, the views held by the subjects are shown in the following table (see Table ).

Table 5. Views of delivering personal information to government for COVID-19 prevention and control

As shown in the table, the number of subjects with negative attitudes (“not quite agree” and “strongly disagree”) is far less than that with positive attitudes (“comparative agree” and “highly agree”), indicating that the majority of the public supports the need to provide personal privacy information to promote the solution of major public security incidents.

Moreover, this study conducted a statistical analysis on the privacy deliver willingness of the subjects in the special period of COVID-19 prevention and control, and the statistical results are shown in the following table (see Table ).

Table 6. Privacy deliver willingness in the period of COVID-19 prevention and control

As shown in the table, subjects generally have a high willingness to deliver personal privacy information in the prevention and control of COVID-19.

Regarding the question of “the influencing factors of voluntarily providing personal privacy data to protect social public interests”, the views held by the subjects are shown in the following table (see Table ).

Table 7. Factors of voluntarily providing personal privacy data to protect social public interests

As shown in the table, among the subjects, the most important factors that make them voluntarily provide personal privacy data to maintain public safety are civil obligation and government trust, the second important factors are social responsibility and public welfare, while conformity and fear of punishment have relatively weak influences. It can be seen that higher education groups have a strong willingness to actively undertake civic obligations and a high degree of trust in the government.

To sum up, the research results show that, despite the high privacy sensitivity and high perception of privacy risk among Chinese higher education groups, they generally have a high willingness to deliver privacy information during the special period of fighting against the COVID-19.

Privacy Security of Higher Education Groups

This study makes a statistical analysis on the privacy security of the subjects in the special period of fighting against the COVID-19 outbreak, and the statistical results are shown in the following table (see Table ).

Table 8. Personal privacy security in COVID-19 prevention and control

As shown in the table, most of the subjects believed that relevant departments could protect public privacy information in the prevention and control of COVID-19, the government could reasonably control the risk of public privacy disclosure, and the current privacy collection policy could bring them a sense of security.

The research results show that in the special period of fighting against the COVID-19 outbreak, Chinese higher education groups have a high sense of privacy security, and they believe that the security of the public’s privacy information can be guaranteed under the situation of epidemic prevention and control by collecting citizens’ personal information.

Factors Influencing Privacy Sensitivity of Higher Education Groups

Among the 470 valid samples collected, 249 males and 221 females were involved. The basic information of potential influencing factors of individual privacy concept is shown in the table below (see Table ).

Table 9. Basic information about the potential influencing factors of individual privacy concept

The correlation analysis of individual privacy sensitivity is shown in the following table (see Table ), and all correlation coefficients are<0.75, indicating that there is no multicollinearity among variables. Among them, there is a significant positive correlation between parents’ education level and individual privacy sensitivity, which indicates that individual privacy sensitivity is deeply influenced by parents’ education level.

Table 10. Individual privacy sensitivity of subjects

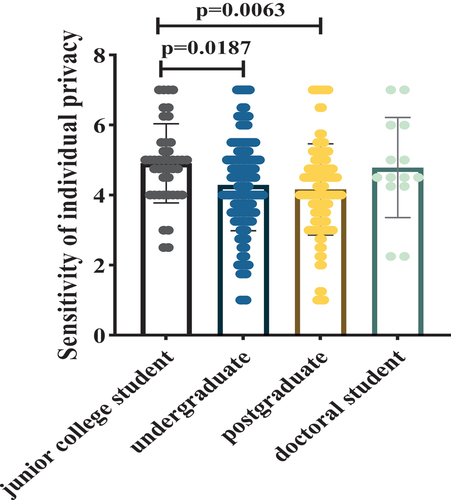

It is worth noting that in the process of exploring the correlation between “educational level” and individual privacy sensitivity, this study divided the subjects into four groups: junior college students, undergraduate students, postgraduates and doctoral students, and examined whether there were significant differences in pairs. The results are shown in the following figure (see Figure ). It can be found that there are some differences between the “junior college student” group and the “undergraduate” group, and there are significant differences between the “junior college student” group and the “postgraduate” group. While there is almost no difference between the “undergraduate” group and the “postgraduate” group. Moreover, the average privacy sensitivity of the “junior college student” group is higher than that of “undergraduate” and “postgraduate”, but there is little difference between the “undergraduate” group and the “postgraduate” group. This may be because the difference between the level of undergraduate education and the level of postgraduate education is less than the difference between the level of junior college education and the two.

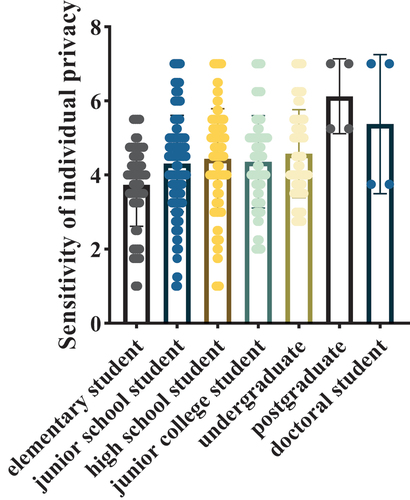

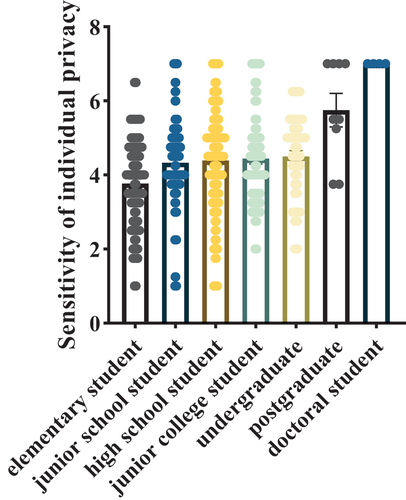

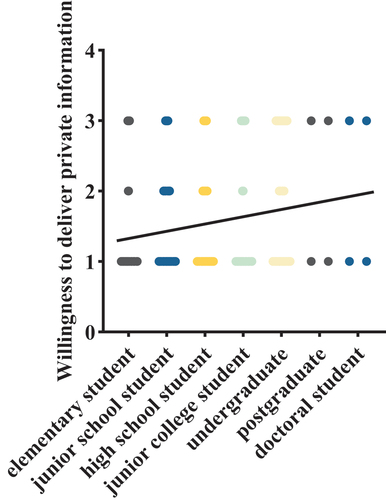

In addition, in the process of exploring the correlation between father’s education level, mother’s education level and privacy sensitivity of individuals, this study divided the education level of subjects’ parents into several groups, such as elementary students, junior school students, high school students, junior college students, undergraduates, postgraduates, doctoral students. The results are shown in the following charts. It can be found that in terms of father’s educational level, there is a significant difference of the “elementary student” group with the “junior school student” group (p = 0.0354), with the “high school student” group (p = 0.0078), with the “undergraduate” group (p = 0.0056), and with the “postgraduate” group (p = 0.0058) (see Figures ). While, in terms of mother’s educational level, there are significant differences between the “elementary student” group and other groups, and there is a significant difference of the “junior school student” group with the “postgraduate” group and the “doctoral student” group, a significant difference of the “high school student” group with the “postgraduate” group and the “doctoral student” group. Also, there is a significant difference between the “junior college student” group and the “doctoral student” group, a significant difference between the “undergraduate” group and the “doctoral student” group (see Figures ). The research results show that there is a significant positive correlation between parents’ education level and individual privacy sensitivity, and the privacy awareness degree and privacy risk perception of Chinese higher education groups are deeply affected by parents’ education level.

Factors Influencing Privacy Deliver Willingness of Higher Education Groups

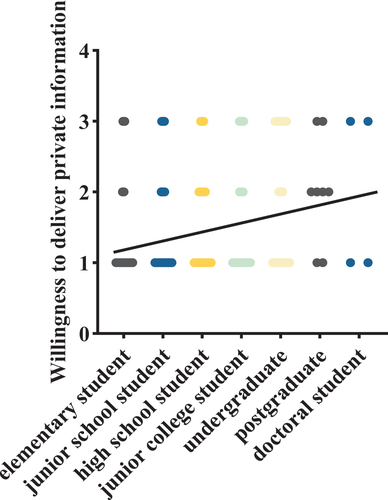

The correlation analysis of individual’s willingness to deliver private information is shown in the following table (see Table ), and all correlation coefficients are<0.75, indicating that there is no multicollinearity among variables. Among them, there is a significant positive correlation of individual’s willingness to deliver private information with father’s education level (see Figure ), with mother’s education level (see Figure ), and with discipline background (see Figures ). While, there is no correlation between educational level and individual’s willingness to deliver private information.

Figure 6. Effects of father’s educational level on subject’s willingness to deliver private information.

Figure 7. Effects of mother’s educational level on subject’s willingness to deliver private information.

Table 11. Factors on willingness to deliver private information

Taking the correlation between “father’s education level” and “individual’s willingness to deliver private information” as an example, this study still classifies father’s education level to several groups, and examines whether there are significant differences in pairs. It can be found that there is a significant difference between the “elementary student” group and the “undergraduate” group (p = 0.0005), a significant difference between the “junior school student” group and the “undergraduate” group (p = 0.0114), and a significant difference between the “high school student” group and the “undergraduate” group (p = 0.0055). Therefore, the educational level of parents will have a certain impact on the individual’s willingness to deliver private information.

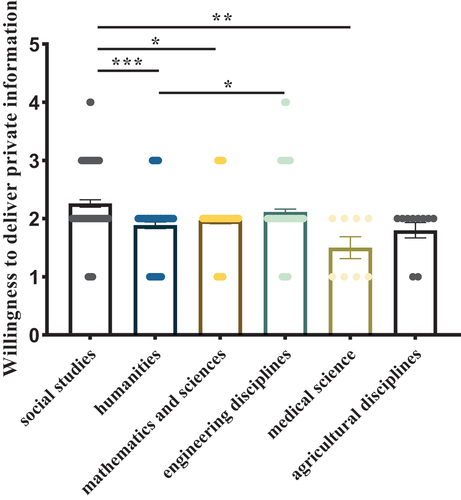

In addition, in the process of exploring the correlation between discipline background and individual’s willingness to deliver private information, this study divided the subjects’ discipline background into six groups: social studies, humanities, mathematics and sciences, engineering disciplines, medical science, as well as agricultural disciplines. The results are shown in the following figures (see Figures ). It can be found that individual’s willingness to deliver private information is affected by the difference of discipline background.

Discussion

Previous studies have shown that, privacy sensitivity reflects the degree to which individuals are informed and know about the practices of other related organizations on their personal privacy (Malhotra et al., Citation2004). This study found that Chinese higher education groups are generally sensitive to personal privacy issues. They are very concerned about their private information and how their private information will be used, and they are cautious about their private information being used by other people or other organizations. However, when it comes to issues related to social welfare and public interests, for example the prevention and control of COVID-19 epidemic, the vast majority of Chinese higher education groups showed their willingness to support the initiative of delivering personal privacy information for helping epidemic prevention. They are often willing to provide their private information to the government and have a high sense of privacy security. The study also found that the privacy concept of Chinese higher education groups is greatly influenced by their education level, their discipline background and their parents’ education level. After comprehensive analysis, this study thinks that there are several reasons to explain this phenomenon.

The deep influence of the education power of cultural environment on the privacy concept of Chinese higher education groups. Culture can be defined as common behavioral patterns and cognitive structures, so culture shapes the way people perceive, think about and act in society (Heine, Citation2010). Education itself is a special cultural phenomenon. On the one hand, it is a means of transmitting and deepening culture. On the other hand, its practitioners and practices themselves reflect the characteristics of culture. Privacy is a cultural phenomenon, and different cultures have different understandings of privacy. In the cross-cultural research on privacy concept, the cultural framework of collectivism-individualism is generally used to compare and explain the differences. As some researchers believe, collectivist and individualistic values contribute more than social values in explaining differences in moral behavior (Ralston et al., Citation2014). Individualism is closely related to self-enhancement, while collectivism pays more attention to the status and well-being of social groups (Markus & Kitayama, Citation1991; Stone-Romero & Stone, Citation2002). A study covering the “privacy calculus” of people social networks sites in five countries shows that people from collectivist-oriented countries place greater emphasis on privacy risks than those from individualist-oriented countries, and attach more importance to safeguard and protect collective interests and security (Trepte et al., Citation2017). Chinese culture emphasizes collectivism and advocates collective value orientation and specific actions. Therefore, although Chinese higher education groups generally pay high attention to privacy and have a high perception of privacy risks, when it comes to issues related to public welfare, such as the prevention of COVID-19, Chinese higher education groups often show willingness to provide their private information, because it is important for them to ensure collective security. In addition, the reproduction of the family itself is also the inheritance and development of culture. Parents’ cultural cognition will influence their children’s way of thinking imperceptibly, which also provides evidence that the privacy concept of Chinese higher education groups is deeply influenced by their parents’ education level.

The profound influence of parents’ experience or past experience on the privacy concept of Chinese higher education groups. As each country has its own specific experience in the control of infectious diseases, Chinese higher education groups' acceptance of disease control measures including COVID-19 is related to their parents’ experience or their own past experience. A recent cross-cultural study covering the United States and South Korea indicates that the South-Korean government can implement COVID-19 control measures that using citizens’ private information without facing serious public opposition. One of the reasons is the painful lesson brought by Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) in South Korea in 2015 (Kim & Kwan, Citation2021). In the course of social development in China, there is also a group experience similar to South Korea. For example, the Wenchuan earthquake in China in 2008 left a painful memory for the Chinese people, and in the process of fighting against catastrophic natural disasters, the determination and response measures of the China government left a deep impression on Chinese people at that time. People living in one country often share similar cultures and past experiences, so a person’s response to a certain threat may be similar to others in the same country. The Chinese government has played an important role in coping with social crises in the past, and Chinese people have a relatively high degree of trust in national measures (Wu et al., Citation2021). Therefore, in the special period of fighting the COVID-19 epidemic, Chinese higher education groups generally have a high willingness to deliver their private information and have a high sense of privacy security.

The important influence of higher education experience on the privacy concept of Chinese higher education groups. Generally speaking, systematic education is contributes to the formation of individual value (Coenders & Scheepers, Citation2003). Learning and living experience in school is crucial to the formation of a person’s concept. For a person, receiving long-term and high-quality education means that a person’s concept can be shaped at a deeper level. Studies have proved that more education can promote individuals to develop a more enlightened world outlook (Brewster & Padavic, Citation2000), and people with higher education experience, in particular, tend to understand issues in a non-biased and relatively comprehensive manner (Pascarella et al., Citation1996; Vogt, Citation1997). Furthermore, some studies have shown that the experience of higher education plays a decisive role in formation of personal values compared with the experience from basic education and secondary education (Brooks & Weber, Citation2022). Compared with other groups, China’s higher education groups are better able to recognize and understand the risk of COVID-19, as well as the importance of delivering personal privacy information (including citizens’ health information and travel track) for the prevention and control of COVID-19, which helps to solve the social crisis to a certain extent.

Conclusion

Nowadays, the value of big data has been discovered by more and more people, and the protection of individual privacy under the background of big data has attracted more and more attention. Under the special background that China collects individual privacy information to better fight against the COVID-19 epidemic, it is worth paying attention to Chinese citizens’ views on the collection of personal privacy data. In particular, it is of research significance and value to explore the privacy concepts of Chinese higher education groups. At present, there are few research achievements in this field. Therefore, this study focuses on the special social background of the fight against the COVID-19, explores the privacy concept of Chinese higher education groups, analyzes its characteristics and causes behind it, and tries to provide some reference value for research in related fields.

With higher education groups from 19 provinces, 4 municipalities directly under the Central Government and 4 autonomous regions in China as research samples, this study discussed the privacy sensitivity, privacy deliver willingness, privacy security and other privacy concept issues of Chinese higher education groups under the background of the COVID-19 epidemic. This study finds that Chinese higher education groups are very concerned about their private information and what kind of their private information will be used, and they are cautious about others or other organizations using their private information. It can be said that Chinese higher education groups generally have high privacy sensitivity and high perception of privacy risks. However, in the special period of fighting against the COVID-19 outbreak, Chinese higher education groups generally have a high willingness to deliver private information and have a high sense of privacy security. In addition, education level, disciplinary background and parents’ education level are important factors affecting the privacy concept of Chinese higher education groups.

It should be noted that the scope of privacy in the era of big data has expanded, especially during the special social period of the fight against COVID-19. Facing the dual pressures of safeguarding public interests and respecting personal privacy, balancing interests is a serious challenge for epidemic prevention and control. In the context of big data, this study believes that relevant institutional measures can be further established and improved to better seek the development mode of big data technology implementation and individual privacy information protection. For example, in the field of higher education, educators should adhere to the principle of correct guidance to let students understand that the privacy state under special social background is different from the normal state of the society, so as to prevent college students from expanding their privacy state. In addition, educators should hold an objective and fair attitude and should not discriminate against some students with special experiences and sensitive information.

Due to the limitations of some subjective and objective factors, there are some shortcomings in this study. For example, the time span of the data samples obtained from the survey is relative short, the subjects are mostly concentrated in the age span of 18–29 years old, and the selected samples do not involve the dimension of occupation, which need to be further explored in future studies to deepen the research.

Correction

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Acknowledgments

We would like to extend our sincere gratitude to our colleagues for their useful suggestions to improve this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Yiting Wen

Yiting Wen is a PhD candidate of moral education in the Center for Ideological and Political Education at Northeast Normal University, People’s Republic of China. His research interests include values education and higher education in China.

Qinghua Cao

Qinghua Cao is an assistant professor at Nanjing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics, People’s Republic of China. She graduated from Center for Ideological and Political Education at Northeast Normal University. Her research interests include youth education, values education and moral education.

Di Gao

Di Gao is a full professor of moral education in the Center for Ideological and Political Education at Northeast Normal University, People’s Republic of China. His research interests include core values, moral culture and soft power.

References

- Acquisti, A., John, L. K., & Loewenstein, G. (2013). What is privacy worth? The Journal of Legal Studies, 42(2), 249–18. https://doi.org/10.1086/671754

- BCG (Boston Consulting Group). (2012). The value of our digital identity. Liberty Global, Inc. Retrieved December 2, 2022, from http://www.libertyglobal.com/PDF/public-policy/The-Value-of-Our-Digital-Identity.pdf

- Brewster, K. L., & Padavic, I. (2000). Change in gender-ideology, 1977–1996: The contributions of intracohort change and population turnover. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 62(2), 477–487. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2000.00477.x

- Brooks, C., & Weber, N. (2022). Liberalization, education, and rights and tolerance attitudes. Social Science Research, 101, 102620. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2021.102620

- Chan, E. Y., & Saqib, N. U. (2021). Privacy concerns can explain unwillingness to download and use contact tracing apps when COVID-19 concerns are high. Computers in Human Behavior, 119, 106718. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2021.106718

- Chen, K., & Rea, A. I., Jr. (2004). Protecting personal information online: A survey of user privacy concerns and control techniques. Journal of Computer Information Systems, 44(4), 85–92.

- Coenders, M., & Scheepers, P. (2003). The effect of education on nationalism and ethnic exclusionism: An international comparison. Political Psychology, 24(2), 313–343. https://doi.org/10.1111/0162-895X.00330

- Ekong, I., Chukwu, E., & Chukwu, M. (2020). COVID-19 mobile positioning data contact tracing and patient privacy regulations: Exploratory search of global response strategies and the use of digital tools in Nigeria. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 8(4), e19139. https://doi.org/10.2196/19139

- Eurobarometer. (2011). Attitudes on data protection and electronic identity in the European Union-Special Eurobarometer survey 359. Retrieved December 2, 2022, from https://www.eubusiness.com/topics/internet/data-protection-11/

- Fogel, J., & Nehmad, E. (2009). Internet social network communities: Risk taking, trust, and privacy concerns. Computers in Human Behavior, 25(1), 153–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2008.08.006

- Global Privacy Assembly. (2020). GPA COVID-19 Taskforce: Compendium of best practices in response to COVID-19. Retrieved December 2, 2022, from https://www.pcpd.org.hk/english/news_events/media_statements/files/compendium.pdf

- Gostin, L. O., Bayer, R., & Fairchild, A. L. (2003). Ethical and legal challenges posed by severe acute respiratory syndrome: Implications for the control of severe infectious disease threats. Jama, 290(24), 3229–3237. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.290.24.3229

- Hassandoust, F., Akhlaghpour, S., & Johnston, A. C. (2021). Individuals’ privacy concerns and adoption of contact tracing mobile applications in a pandemic: A situational privacy calculus perspective. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 28(3), 463–471. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocaa240

- Heine, S. J. (2010). Cultural psychology. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Janda, S., & Fair, L. L. (2004). Exploring consumer concerns related to the internet. Journal of Internet Commerce, 3(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1300/J179v03n01_01

- Ji, P., & Lieber, P. S. (2010). Am I safe? Exploring relationships between primary territories and online privacy. Journal of Internet Commerce, 9(1), 3–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332861.2010.487413

- Kim, J., & Kwan, M. P. (2021). An examination of people’s privacy concerns, perceptions of social benefits, and acceptance of COVID-19 mitigation measures that harness location information: A comparative study of the US and South Korea. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information, 10(1), 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi10010025

- Li, H., Sarathy, R., & Xu, H. (2011). The role of affect and cognition on online consumers’ decision to disclose personal information to unfamiliar online vendors. Decision Support Systems, 51(3), 434–445. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dss.2011.01.017

- Majeed, A., & Hwang, S. O. (2021). A comprehensive analysis of privacy protection techniques developed for COVID-19 Pandemic. IEEE Access, 9, 164159–164187. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/9627089

- Malhotra, N. K., Kim, S. S., & Agarwal, J. (2004). Internet users’ information privacy concerns (IUIPC): The construct, the scale, and a causal model. Information Systems Research, 15(4), 336–355. https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.1040.0032

- Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (1991). Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review, 98(2), 224. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.98.2.224

- Milne, G. R., & Culnan, M. J. (2004). Strategies for reducing online privacy risks: Why consumers read (or don’t read) online privacy notices. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 18(3), 15–29. https://doi.org/10.1002/dir.20009

- Newlands, G., Lutz, C., Tamò-Larrieux, A., Villaronga, E. F., Harasgama, R., & Scheitlin, G. (2020). Innovation under pressure: Implications for data privacy during the Covid-19 pandemic. Big Data & Society, 7(2), 2053951720976680. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951720976680

- Pascarella, E. T., Edison, M., Nora, A., Hagedorn, L. S., & Terenzini, P. T. (1996). Influences on students’ openness to diversity and challenge in the first year of college. The Journal of Higher Education, 67(2), 174–195. https://doi.org/10.2307/2943979

- Petronio, S. (2002). Boundaries of privacy: Dialectics of disclosure. Suny Press.

- Pool, J., Akhlaghpour, S., Fatehi, F., & Gray, L. C. (2022). Data privacy concerns and use of telehealth in the aged care context: An integrative review and research agenda. International Journal of Medical Informatics, 104707, 104707. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2022.104707

- Ralston, D. A., Egri, C. P., Furrer, O., Kuo, M. H., Li, Y., Wangenheim, F., Weber, M. … Weber, M. (2014). Societal-level versus individual-level predictions of ethical behavior: A 48-society study of collectivism and individualism. Journal of Business Ethics, 122(2), 283–306. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1744-9

- Stone-Romero, E. F., & Stone, D. L. (2002). Cross-cultural differences in responses to feedback: Implications for individual, group, and organizational effectiveness. In Research in Personnel and Human Resources Management (pp. 275–331). Emerald Group Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0742-7301(02)21007-5

- Trepte, S., Reinecke, L., Ellison, N. B., Quiring, O., Yao, M. Z., & Ziegele, M. (2017). A cross-cultural perspective on the privacy calculus. Social Media+ Society, 3(1), 2056305116688035. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305116688035

- Urban, J. M., & Hoofnagle, C. J. (2014). The privacy pragmatic as privacy vulnerable. Proceedings of the Symposium on Usable Privacy and Security (SOUPS), Menlo Park, CA.

- Vogt, W. P. (1997). Tolerance & education: Learning to live with diversity and difference. Sage Publications.

- Wang, Y. Y., & Liu, X. Y. (2017). 大数据时代下个人隐私将面临的新问题及防护对策研究——以大学生群体为切入点[new problems of personal privacy in the era of big data and protective countermeasures——Starting from College Students]. Journal of Tsitsihar College, 5, 78–79.

- Wang, Z., & Zhao, H. (2014). 大数据时代个人数据的隐私顾虑研究——基于调研数据的分析[privacy concerns of personal data in the era of big data——based on the analysis of survey data]. Information Theory and Practice, 11, 26–29.

- Wan, L., & Zhang, Y. (2020). 国内外隐私素养研究现状分析[analysis of research status of privacy literacy at home and abroad]. Library and Information Service, 64(12), 144–150.

- Wu, C., Shi, Z., Wilkes, R., Wu, J., Gong, Z., He, N., Xiao, Z., Zhang, X., Lai, W., Zhou, D., Zhao, F., Yin, X., Xiong, P., Zhou, H., Chu, Q., Cao, L., Tian, R., Tan, Y., Yang, L. … Nicola Giordano, G. (2021). Chinese citizen satisfaction with government performance during COVID-19. Journal of Contemporary China, 30, 930–944. https://doi.org/10.1080/10670564.2021.1893558