Abstract

This study investigated the epistemic conventions of pedagogical practices in higher education (HE) from the viewpoints of lecturers. Phenomenological design, focusing on semi- structured interview guide, was considered for the study. Through the purposive sampling technique, 15 lecturers from three departments of institution of higher learning were considered for the study. The study utilised emerging themes as an analytic procedure. Analysis focused on two principal domains: Peripheral Academic Writing Practices with focus on Pedagogy (PAWP-P), and Actual Academic Writing Practices focusing on Pedagogy (AAWP-P). In terms of PAWP-P, lecturers considered students’ ability to engage in self-regulated practices such as perusing course outline, concomitant with reading and making their own notes prior to lectures to be momentous pedagogical practices. Also, in tandem with AAWP-P, lecturers placed dialogue, argument, meaning making, and criticality (i.e. analysis, evaluation, and creation) as requisite pedagogic practices in HE. In addressing the pedagogical limitation in Lea and Street’s (1998) academic literacies model, the finding of this study helps to build on the model; hence, in this study, Lea and Street’s (1998) academic literacies model is reconceptualised as academic socialisation, with three developmental overlapping orbitals: electromagnetic wave, normative socialisation and academic literacies socialisation. Management in HE should prioritise the teaching of Information Literacy and Language Literacy courses such as Communicative Skills (variously expressed elsewhere as Use of English, Writing across the Curriculum, General Composition, and Academic Writing).

Public Interest Statement

Lecturers are responsible for shaping the thinking, feelings, and actions of students in higher education. Hence, lecturers determine the ideal pedagogical practices in higher education, and the nature of these practices should be clear to students. However, previous studies have shown that, according to lecturers, students are not appropriating pedagogical requirements in higher education. Therefore, the present study utilizes the academic literacies model propounded by Lea and Street (Citation1998), which has been guiding curriculum development and instructional practices as well as research at the tertiary, secondary, and basic levels to investigate the perspectives of lecturers regarding ideal pedagogical practices in higher education. These pedagogical practices have been grouped into two: what lecturers expect students do before classroom engagement and what they (students) should do during classroom engagement.

1. Introduction

The academic literacies model propounded by Lea and Street (Citation1998) has been guiding curriculum development and instructional practices as well as research at the tertiary (in particular, university), secondary, and basic levels (M. Lea & Street, Citation2006). Lea and Street (Citation1998) conceptualise the academic literacies model into three overlapping strands: study skills (focuses on language and structure), academic socialisation (deals with disciplinary conventions) and academic literacies (addresses identity, power relation and epistemological renditions of various disciplines, and it is multifaceted in nature). The conceptualisations of the generic skills (GS) have informed the development of a core programme, usually considered as English language support in most English-medium universities in the world. Such learning support has variously, and specifically been named as English for Academic Purpose (EAP) and General Composition (GC) or Freshman Composition (FC) (Coffin & Donohue, Citation2012; Gimenez & Thomas, Citation2015). Whereas EAP has its root in the United Kingdom (UK) and in Canada owing to the state of internationalisation of HE, FC or GC, and in recent times, Writing in the Disciplines (WID) emerged from the USA to address students’ writing problems (Bazerman & Russell, cited in Afful, Citation2007). In many tertiary educational institutions in Ghana, EAP and FC are labelled as ‘Communicative Skills (CS) (Afful, Citation2007). In addition, the conceptualisations of academic socialisation (AS) and academic literacies (ALs) have helped in socialising students in meaning making of varied disciplinary fields. This has culminated into lecturers adopting multiple practices such as criticality, logic, reason, dialogue, voice, argument, and digitality (Canagarajah & Canagarajah, Citation2017; Lancaster, Citation2016; Stordy, Citation2015) to influence the “thinking”, “feelings”, and “actions of students” (Barton & Hamilton, Citation1998; Gimenez & Thomas, Citation2015, p. 30).

Thus, previous studies conducted to address practices surrounding students’ writing across the globe seem to shift the focus from the study skills approach to a more blended approach—academic literacies and disciplinarity (Gorska, Citation2018; John, Citation2019; Lea & Street, Citation1998; Wong & Chiu, Citation2018). For example, in a number of studies conducted in the United Kingdom (Lea & Street, Citation1998), it has been observed that academic staff have varied perspectives as to what constitutes “good” academic writing, and therefore, they describe student writing in disciplinary terms. For example, findings from such studies show that while in History the use of evidence is vital, in English, clarity of expressions is paramount. Wong and Chiu (Citation2018) have also revealed from an empirical investigation that university lecturers expect students to be committed to academic writing materials such as the course outline and textbooks. Davison et al. (Citation2017) have, thus, noted that the course outline is influential in the nature of content, teaching methodology, assessment and, by extension, program development and program evaluation. Further, Gorska (Citation2018) has identified that lecturers in the UK emphasise classroom discussion as well as surface features of form. Furthermore, Olsson et al., (Citation2021) have shown that formative feedback, peer assessment, and reflective journaling are useful pedagogical approaches that can be adopted to address AW in HE. The researchers, thus, argue for the strengthening and extension of ALs framework through reflective practice and independent research.

In a related set of studies conducted in the USA and Canada (e.g., Greenfield, Citation2015; Hassel & Ridout, Citation2018; John, Citation2019) findings indicate that the use of multiple literacies approach such as photostory, audio, visual, spatial or gestural, and digital storytelling are more instrumental in enhancing students’ understanding of concepts in the classroom than the traditional mode of using oral words. Also, Greco (Citation2015) and Burke and Hardware (Citation2015) identify that the focus on multiliteracies approach helps students shift from the passive consumption of concepts in the classroom to interactive and active engagement with pedagogical issues. This kind of engagement triggers criticality in students (e.g., Canagarajah & Canagarajah, Citation2017; Lancaster, Citation2016).

Similarly, in the context of Africa, extant studies (Jonker, 2016; Scholtz, Citation2016; Twagilimana, Citation2013, Citation2017) have shown that academic literacies practices such as encouraging students to take charge of their own learning, while being self-efficacious and observing disciplinarity are very instrumental in students’ literacy development. For example, Scholtz (Citation2016) has identified that lecturers focus considerably on the surface features of form such as language and structure, while paying little or no attention to meaning making, interpretation, and argumentation (Canagarajah & Canagarajah, Citation2017; Lancaster, Citation2016) and criticality (Janks, Citation2010; Lancaster, Citation2016). Hence, Scholtz (Citation2016) proposes the use of the hybrid approach to be at the center of teaching and learning in HE. Again, in Ghana, while Afful (Citation2007) proposes changes in the curriculum of Communicative Skills (also known in several universities as EAP) in favour of ALs approach, Amua-Sekyi (Citation2011) reports that lecturers expect students to be critical in their academic writing practices but this aim is not translated in lecturers’ practices in the classroom.

From the foregoing studies, it can be said that there is a general consensus to shift the focus of generic skills to academic socialisation and ALs approaches. However, it appears that lecturers in Africa face challenges such as inadequate resources in their pedagogical practices (Amua-Sekyi, Citation2011; Scholtz, Citation2016; Twagilimana, Citation2013, Citation2017). In addition, most of these studies Canagarajah and Canagarajah (Citation2017); Lancaster (Citation2016); Lea and Street (Citation1998) seem to focus on assessment practices such as written assignments without considering practices in and outside classroom. Other studies (e.g., Gorska, Citation2018; Tuck, Citation2013) which concentrate on classroom related practices (referred to as Actual Academic Writing Practices, with focus on Pedagogy) fail to consider practices undertaken prior to classroom engagement (referred to in this study as Peripheral Academic Writing Practices, with focus on Pedagogy). Therefore, this study aims to explore lecturers’ consideration of the Ideal Peripheral Academic Writing Practices, with focus on Pedagogy (PAWP-P) as well as Actual Academic Writing Practices focusing on Pedagogy (AAWP-P).

1.1. Lea and Street’s Academic Literacies Model

Lea and Street (Citation1998) sought to build on New Literacies Studies (see Barton & Hamilton, Citation1998; Boughey & McKenna, Citation2017) as well as reading, writing, and literacy as social practices by exploring the contrasting expectations and interpretations of academic staff and undergraduate students regarding written assignments. From the study, Lea and Street (Citation1998) argue for a new approach to challenge the “deficit” model, which has dominated academic writing practices. They argue for epistemological conceptualisations of university courses and student writing in the academic context. This led them to embrace approaches to student writing in the academic context from three overlapping models, namely study skills, academic socialisation and academic literacies.

The study skills model is an autonomous means of acquiring surface features of language such as grammar, punctuation, spelling and sentence structure, which can be transferred to all contexts (M. Lea & Street, Citation2006). The second model, academic socialisation approach, seeks to correct or complement the study skills approach so as to focus on “meaning of the skills involved and attention to broader issues of learning and social context” (Lea & Street, Citation1998, p. 157). Students negotiate or construct knowledge or meaning by recognising conventions that are accepted by expert members of the discourse community. The third model proposed by Lea and Street is the academic literacies model, which according to them, focuses on identity, power relations, institutional factors and epistemological foundations of a given academic discipline (see Janks, 2002a; Janks, Citation2012). The academic literacies model, drawing on New Literacy Studies, is associated with “ideological model of literacy” (Gorska, Citation2018, p. 54).

The ALs model has been criticised (see Lillis, Citation2003; Russell et al., Citation2009) though for its lack of viability and practicality in pedagogical instructions in HE. For example, it is suggested that the ALs model should be developed as a curriculum design in aid of pedagogical instruction (Lillis, Citation2003). Given the criticisms against the ALs model, Lillis (Citation2003) has attempted to provide the pedagogical implications of the ALs approach. Lillis argues “for dialogue, rather than monologue or dialectic to be at the centre of ALs stances and thus, outlines some design implications of a dialogic approach to student writing pedagogy” (p. 192). The dialogic approach, Lillis argues, is based on “talkback instead of feedback, opening up disciplinary content to external interests and influences, and opening up academic writing conventions to newer ways to mean” (pp. 204–205). We argue here that Lillis’ approach is not elaborate and conclusive; hence, the need for further consideration of ALs.

In order to address the criticism leveled against Lea and Street’s ALs models and to develop the model as a curriculum design in aid of pedagogical instruction (see Lillis, Citation2003), we advocate that Lea and Street’s “study skills” should be considered as a “medium of instruction” in pedagogical instruction. In addition, academic socialisation model should be seen as a “regulatory method” of teaching. Equally, academic literacies should be seen as a participatory method of teaching. Thus, a set of univariate skills such as grammar, spelling, punctuation, and structure that are uncontested and transferrable across all disciplines (see, Afful, Citation2007; Ivanič, Citation2004; Scott et al., Citation2007) is considered as a medium of instruction. Also, any approach that requires students to master norms (see John, Citation2019) or acculturate students in the historical, cultural, and political orientations of a particular discipline without considering the epistemological orientations that students bring to the learning environment addresses Lea and Street’s academic socialisation (known in this study as “normative instruction” or “regulatory method of teaching”). On the other hand, any approach that recognises issues of power, identity, criticality and the epistemological orientations that learners bring to the learning environment, while recognising the intellectual freedom of the learner refers to Lea and Street’s academic literacies (also known in this study as “participatory method of teaching” or “academic literacies socialisation”).

1.2. Pedagogical Implications of Lea and Street’s Academic Literacies Model

Pedagogy has been described as “art or science of teaching” (Alexander as cited in Simpson, Citation2018, p. 4). This definition appears to be too simplistic and, therefore, we draw on Bourn’s (as cited in Simpson, Citation2018) conceptualisation of pedagogy as encompassing two faces. The first focuses on the practice of forms and methods of teaching, and the second addresses issues of meaning and theory about how children learn, how teaching is done, how the curriculum is structured, and how culture is integrally structured within the curriculum.

The implications of these three models to pedagogical instruction are that the study skills approach (medium of instruction) emphasises language: grammar, punctuation, vocabulary, and spelling; structure: introduction, content, conclusion, and sentence structure (cohesion and coherence). Also, the academic socialisation model (regulatory method of teaching) draws on Genre Theory as it ensures that students are inducted and acculturated not within a broader frame of generic skills but within the prototypical use of language—drawing attention to the goals, norms and values that are shared by members of the social community (Hyland, Citation2002). It also harmonises Behaviourist Theory of learning or deficit model, which sees the learner as a “tabula rassa” or an empty jug ready to be filled (Etsey & Ocran, Citation2020; M. Lea & Street, Citation2006). The regulatory method of teaching is rooted in what Freire (Citation2010) refers to as “regulatory pedagogy”. In this approach, the learning environment is characterised by the oppression of students’ voices, memorisation and repetition of facts by students, and domination or authority of teachers (Freire, Citation2010; Lu, Citation2012). As teacher-centered, it focuses on direct instruction, abstractness, teacher clarity, note writing, handouts, monologue, and drills (Amua-Sekyi, Citation2011; Lillis, Citation2003). Freire refers to regulatory pedagogy in his book: “Pedagogy of the Oppressed” as “banking concept of education” (Tsegay, Zegergish, & Ashraf, Citation2020, p. 92).

Furthermore, it is worth noting that the principles of Lea and Street’s ALs (known in this study as “participatory method of teaching”) coincide with the epistemic conventions of cognitivist and constructivist theories of learning. In cognitivism, emphasis is placed on meaningful learning, where new information is linked with previous knowledge (Etsey & Ocran, Citation2020). This is also augmented by Social Cognitivism, which considers the relevance of the link between behavioural, environmental and personal factors in the process of learning (Bandura, Citation1991). Two key principles are emphasised by Bandura: self-efficacy and self-regulation. Olivier (Citation2016, p. 85) considers self-efficacy “as the confidence or personal beliefs that people have about their own abilities to learn or produce certain actions at selected levels”, while self-regulation is seen as “self-generated thoughts, feelings, and actions that are planned and cyclically adopted to attain personal goals” (Schunk & Ertmer cited in Olivier, Citation2016, p. 85). In constructivism, there is a considerable emphasis on support to the learner in order to help him/her to reach the point of independence (Conradie, Citation2009). This draws attention to the concept of andragogy in the teaching and learning process (Merriam, Citation2001), which “is the art and science of helping adults to learn” (Knowles, Citation1980, p. 43). Therefore, students in HE who are oriented towards this type of learning take active part in the learning process, self-direct and self-regulate their learning, create knowledge with the cooperation and collaboration of their teachers and peers.

Again, in participatory method of teaching, Freire’s (Citation2010) participatory pedagogy is worth mentioning. Here, the process of teaching and learning is collectively created by both the teacher and the student. In participatory pedagogy, dialogue (see Lillis, Citation2003 for added emphasis) is seen as the main drive of classroom interaction and that teachers are not seen as the only producers of knowledge but there is mutual growth and development in terms of transmission and assimilation of knowledge (Tsegay, Zegergish, & Ashraf, Citation2020). Hence, in this approach, knowledge sharing operates on the horizontal continuum, where knowledge can be given by teachers to students and vice versa (ibid). Simpson (Citation2018) further argues that teachers who are oriented towards the participatory pedagogy recognise students as persons with knowledge, understanding, feelings and interest; therefore, such teachers expect students to be interactive in classroom discussion, and take initiative in their own learning.

In line with the foregoing discussion, we argue that previous and current thinking has not helped much in appreciating the dynamics and constituents of the term “pedagogy”. In view of this, we redefine pedagogy as the “the process of preparing and adopting useful strategies (either regulatory method of teaching or participatory method of teaching) in order to shape the feelings, thinking, and actions of students within culturally valued knowledge, skills, attitudes through a medium of instruction”. It should be noted from this definition that pedagogy is not an extemporaneous dogmatic way of shaping the knowledge of educands; rather, it is a two-edged sword, which goes through a cautious preparation before the final delivery of knowledge. This process is what is termed in this study as Peripheral Academic Writing Practices with focus on Pedagogy (PAWP-P). After a careful preparation, tutors enter the classroom to deliver the content of their peripheral practices; this is referred to in this study as Actual Academic Writing Practices with focus on Pedagogy (AAWP-P). As tutors engage in both peripheral and actual pedagogical activities, they as well have certain expectations of practices students should engage in before attending lectures (PAWP-P), and what they (students) should exhibit in the classroom (AAWP-P). Noticeably, these theories and concepts are useful for the present study because they do not only provide the direction and focus of the research objectives, but more importantly, they provide the basis for the analysis carried out in this study. That is, the conceptualisations of the study skills approach (medium of instruction), academic socialisation (normative socialisation), and academic literacies (participatory method of teaching) provide the trajectory for the analysis of tutors’ expectations of the two dichotomised practices in HE: PAWP-P and AAWP-P.

2. Research Methods

The study adopted qualitative approach by focusing on the phenomenological design. Qualitative research deals with a number of naturally occurring phenomenon in detail and adopts verbal rather than statistical approaches (Cohen et al., Citation2018). Qualitative approach explores the minds of participants as well as assist researchers to: “understand the world as seen by the respondents” (Patton, Citation2014, p. 21). The phenomenological design was used for this study because we sought to understand how individuals or group of people experience, describe, recall, interpret and make decisions on a particular phenomenon. Thus, the phenomenological design made it possible for us to explore into detail epistemological positions of lecturers regarding the ideal pedagogical practices in HE.

In line with the purposive sampling technique, 15 lecturers were sampled from three departments, namely English, History and Religion. This sampling technique helped us to focus on lecturers who handled undergraduate students, and therefore, by virtue of their position, had in-depth knowledge about ideal pedagogical practices of undergraduate students (see, for example, Cohen et al., Citation2018). Primary data was obtained from lecturers with the use of semi-structured interview guide. The primary source of data was corroborated with secondary source of data such as documents (60 course outlines; 20 from each department). Participants’ responses were tape-recorded and transcribed to help analysis. In order to ensure trustworthiness of the data, we engaged the participants in a long conversations by probing the participants’ responses; and also, copies of the transcribed data were given to the participants to certify the accuracy of their responses. Thematic analysis was used. Given that this study involved human participants, ethical clearance was obtained from the Institutional Review Board, University of Cape Coast—ID (UCCIRB/CES/2021/79). In order to ensure strict adherence to matters of anonymity and confidentiality, we used pseudonyms to represent the names of lecturers such as ENG L1 for the first English lecturer interviewed, HIS L1 for the first History lecturer interviewed and RHV L1 for the first Religion lecturer interviewed in that order.

3. Results

This study sought to find out the epistemological orientations of lecturers in terms of what constitutes the ideal pedagogical practices in HE. In all, two research questions guided the study, which covered the following themes: peripheral pedagogical academic writing practices of lecturers and actual academic writing practices of lecturers.

3.1. Peripheral pedagogical academic writing practices of lecturers

An examination of the interview data reveals a number of activities that undergraduate students are required to do before they attend lectures. The activities include undergraduate students acquainting themselves with the course outline, engaging in self-regulated reading and self-reflected note making. These are discussed in the sections that follow.

One of the themes identified in the interview data is students’ familiarisation with the course outline. Familiarisation with the course outline suggests continuous reading of the course outline to get to know the contents, dynamics and requirements of the course under consideration. An ideal course outline provides course description, course objectives, topics to be treated each week, the various reference materials or sources of information for the content of the course, and lastly course requirements (see, for example, Davison et al., Citation2017). In all the three disciplinary fields, the lecturer-participants project students’ familiarisation with the course outline as one of the activities students are required to demonstrate prior to classroom engagement. In fact, responses from the lecturer-participants emphasise that the course outline is a pedagogical material. The interview data confirm that the preparation of the course outline in itself is tantamount to executing a portion of the pedagogic instruction for the semester. The following extracts elucidate this point further:

Extract 1

Well, before the beginning of the semester, course outline is prepared, which is made available to the students. So, what I expect them to do before coming to class is to read the course outline and know a particular topic that we are going treat on a particular day. For example, on the course outline, the student knows that for this day, you are going to treat topic A, and topic A has this and that as the reading materials to use. (ENG L1)

Extract 2

In the first place, I would have given the students a course outline, detailing what the course is about. And I typically make available course materials like power point, or textbooks and so before class, I expect the student to know the topic for the day. (RHV L1)

Extract 3

If I give out my course outline, I have done 30% of teaching and learning for the semester. By giving it out and explaining the component of the course, the objectives, the expectations, and mode of assessment, I have done 30% of the work. (HIS L2)

The foregoing extracts (1–3) reveal that in HE, the course outline is a prerequisite of the teaching and learning process, and that undergraduate students are expected to be familiar with its contents. This is common among all the disciplinary fields; that is, the course outline forms the core of the curriculum of HE.

Self-regulated reading is one of the themes identified in the responses of the lecturer-participants. The concept of self-regulated reading used here means students’ interest and personal beliefs to search and read on their own without direct information generated or produced by the lecturer. Therefore, given that the course outline captures the topics and the materials required for the semester, lecturers expect students to do their own reading before coming to class. For example, when asked what lecturer-participants expected from their students before they (students) came to class, this is what one of the respondents said: So in that case, I expect that students read on that particular topic before coming to class (ENG L1). Additional comments that corroborated this comment included:

Extract 4

I prefer a discussion method so I don’t expect my students to come to class with an empty head. You come to class, having read what we are to do today so that when we are discussing, there would be a good flow (RHV L1)

Extract 5

I expect them to read because with the course outline, 50% of the work has been done by the lecturer. The university is not a place where you will be spoon fed. You have the course outline. If unit one is what we are going to do, I expect you to read before coming. This is why the reading list is on the course outline to guide you. So you read before you come to class. So when you come to class, I may begin by asking questions and continue from there. (HIS L1)

As noted in the foregoing extracts (4–5), undergraduate students are expected to engage in self-regulated reading before attending class, which, in the view of the lecturers, is directed towards useful and productive discussions in class.

Owing to this expectation, content analysis, particularly of the course requirements in the course outline, was conducted. The analysis of the course requirements across the three disciplines (English, Religion, and History) reveals disciplinary variations. For instance, while English lecturers consciously describe the need for students to read the course outline before going to class, as found in Extracts 6–8, Religion and Human Values and History lecturers do not adopt this approach. That is, while History lecturers do not include any course requirement, Religion and Human Values lecturers focus on class attendance and participation.

Extract 6

You are expected to read the assigned reading before coming to class. Note that university students, you are expected to take initiative in learning. Reading the assigned reading before class will help you to understand the class discussion better. We will not read the assigned reading in class; however, illustrations, discussions and quizzes may be based on the reading (END1).

Extract 7

This course will comprise lectures, student-led seminars and discussions. Students will be expected at these meetings to express their own ideas about what they have read (END12).

Extract 8

Two hour sessions: class held every week as lecture-seminar sessions, key issues and debates will be introduced and discussed, with readings assigned to students from relevant books and journal articles. Students will be encouraged to do the basic readings before class … . (END11).

Extract 9

Students will undertake private readings and directed readings of selected relevant texts—scholarly articles, journalistic articles, and book … (HDN16).

As can be seen from the extracts above (6–9), the requirement to read beforehand is more predominant among English lecturers than in History and Religion.

Apart from self-directing their own learning by engaging in careful reading, lecturers consider it an ideal pedagogical practice for students to produce their own knowledge through self-regulated note making. Self-regulated note making is the process whereby students spend time to read and control their thoughts, reflect on the information they have read, sieve through the information and write down salient points that are related to the topics or content captured in the course outline (Olivier, Citation2016). Consequently, the interview data highlight students’ ability to make their own notes before going to class. One of the respondents articulated: I also expect them to make their own notes before class (RHV L1). A more elaborated comment is offered by one of the respondents in Extract 10:

Extract 10

So while reading, I expect that they make their own notes so that before coming to class, you are more or less armed with something and then I will come and stand before them and explain that today, we are talking about this particular topic. This particular topic deals this issue, and since the student has made their own notes, he/she can refer to this note that he has written and ask questions that may contribute significantly to the class discussion, which makes the class interactive (ENG L1)

Extract 10 shows that undergraduate students are expected to engage in self-efficacy and self-regulation practices before they attend lectures.

3.2. Actual academic writing practices with focus on pedagogy

Further analysis of the interview data suggests that what lecturers across the three disciplinary fields, namely English, Religion and History consider ideal pedagogical practices are not different, as they express similar epistemological positions regarding the requirements of AW practices in HE. Thus, the themes from the interview data compel undergraduate students to adopt a multifaceted approach such as listening and making contributions, taking notes, and asking useful questions in class.

One of the themes from the interview data is class discussion. All the lecturers in the three disciplines interviewed expected students to pay attention and contribute in class. Apparently, this particular theme is sequel to the preceding theme discussed, where students are expected to read before class. The rationale is to engage the students in class discussion rather than lecturing. In classroom discussion, undergraduate students are expected to ask useful questions. Take, for example, Also, I expect them to ask good questions. I want them to participate in class (HIS L3). The following extracts further provide support to this theme:

Extract 11

This is university, so we don’t necessarily expect students to be copying notes at lectures. I will generate knowledge. We don’t just impact knowledge. So just sitting down and copying notes is not proper. So I engage the students in discussions. (ENG 3)

Extract 12

I make them engage in discussion and guide them to form groups in order to reflect on the issues discussed in class (HIS 2); I sometimes want them to listen and pay attention and contribute to the discussion (RHV 4).

Extract 13

The students will undertake private readings and directed readings of selected relevant texts—scholarly articles, journalistic articles, and books—and have in class discussions on various aspects of the concerns of the course (HDN16).

The extracts (11–13) given above reject the reliance on note copying in class and focuses on classroom discussion, where students are required to actively participate. This theme is strongly replicated by the course outline, as under course requirements in the course outline, the learner is obliged to attend classes regularly and partake in class discussion. What is interesting is the award of marks in the course outline, as shown in the extracts below:

Extract 14

Students who will attend all the lectures till the end of the module will be awarded a bonus mark (RHV DN1). Marks are allotted for class participation, as captured on the course outline (see appendix RHV DN1).

Extract 15

Regular class attendance is required. Attendance and participation will influence the circulation of the final grade. Students are strongly advised to come to class prepared and ready to engage in discussions (EDN12).

Strikingly, the award of marks depicts the kind of importance that lecturers attach to students’ participation in class.

An additional theme identified in the interview data is self-reflective note making. Self-reflective note making is the situation whereby students pay attention and listen to lecturers’ lesson delivery, while reflectively sieving through the flow of information and noting down salient points for future reference. This is visible in the systematic justification of the participants, as seen in the following extracts:

Extract 16

It is not compulsory for the student to take note but if it happens that there is an important information that I need the student to take note of, I do tell them to take note. So in that case, I am telling them to put something down, which is note copying. But then as a lecturer, I will not expect students to ask me to give them notes. Rather, I expect students to make their notes from all that is said in class. (ENG L1)

Extract 17

But … I encourage them to try as much as possible to write as much as they can. When you get back, you look at what you wrote and then you organise it for your understanding of the concept. (RHV L1)

Extracts 16 and 17 suggest that lecturers consider note taking as necessary in their engagement with students.

4. Discussion

The study explored lecturers’ position on ideal pedagogical practices in HE through interview, and supplemented by course outline. In relation to PAWP-P, results from the study indicated that all the lecturers in the three disciplinary fields expected students to acquaint themselves with the course outline, engage in self-regulated reading, and self-reflected note making before attending lectures. Also, regarding AAWP-P, all the lecturers considered class discussion, active participation in class and self-reflected note making to be ideal pedagogical practices in HE.

First, the issue of students’ acquaintances with the course outline suggests that the course outline forms the core of the curriculum of HE. For example, Davison et al . (Citation2017) have noted that the course outline is influential in the nature of content, teaching methodology, assessment and by extension program development and program evaluation. Students are, therefore, expected to consider the course outline as a scaffolding material, which helps them to identify some useful academic materials to guide them in independent learning. This scaffolding material (course outline) reflects academic literacies by Lea and Street (Citation1998) and by extension, the constructivists’ pedagogical practices, and particularly participatory method of teaching, which addresses the collaborative creation of knowledge by both the teacher and the student. Wong and Chiu (Citation2018) have also revealed from an empirical investigation that university lecturers expect their students to be committed to academic writing materials such the course outline and textbooks. Also, the issues of self-regulated reading and note making align with Lea and Street’s (Citation1998) academic literacies model as well as Bandura’s (Citation1991) self-efficacy and self-regulation in cognitivism. In addition, these issues correspond with PAWP-P described in this study. These concepts (self-efficacy and self-regulation) are respectively seen as “the confidence or personal beliefs that people have about their own abilities to learn or produce certain actions at selected levels”; and “self-generated thoughts, feelings, and actions that are planned and cyclically adopted to attain personal goals” (Schunk & Ertmer cited in Olivier, Citation2016, p. 85).

Furthermore, the concepts of discussion (where students interact and share their ideas in class), and self-reflected note making (where students sieve through the myriad of ideas presented in the classroom and write down the most useful ones for future reference) are situated within AAWP-P. Again, these concepts and practices accord with academic literacies theory (particularly academic socialisaion and academic literacies) that frames this study. That is, Janks (Citation2002) has shown that, in the academic literacies and academic socialisation, emphasis is placed on the student’s ability to argue, critique and project their own voice (criticality) in their various disciplines. In a similar study, Gorska (Citation2018) found that UK lecturers emphasise classroom discussion in their pedagogical instructions. The commonalities (i.e., students taking initiative in their own learning and being critical) among the lecturers’ responses across the three disciplinary fields in this study and that of previous studies (Canagarajah & Canagarajah, Citation2017; Janks, Citation2002, M. Lea & Street, Citation2006) suggest that these concepts (i.e., ideology, criticality, and learner freedom) have become ubiquitous pedagogical conventions in institutions of higher learning.

It appears from the foregoing discussion that the concepts of normative socialisation, regulatory pedagogy or regulatory method of teaching are unimportant in the pedagogical actualities of institution of higher learning. For example, evidence from studies (e.g., Lancaster, Citation2016; Lea & Street, Citation1998) favours issues of meaning making, interpretation, argument and criticality. In Ghana, Afful (Citation2007) proposes changes in the curriculum of EAP, in favour of ALs approach, while Amua-Sekyi (Citation2011) reports that lecturers expect students to exhibit criticality in their academic writing practices. We, however, contend that the epistemic formalities of EAP, WID, CS such as language and structure are extremely important without which the novelties prescribed in ALs model or participatory pedagogy cannot be realised, as it serves as a medium through which the principles of ALs are addressed. Again, the concept of “reading” emphasised in the lecturers’ responses, is situated in the normative socialisation, where students are seen as consumers of knowledge (see Hyland, Citation2002).

Moreover, the comments by the lecturer-participants (see Extract 10) suggest that the normative socialisation concept of reading, listening and paying attention helps build academic literacies concept of meaning making, argument and criticality. Similarly, earlier researchers (see, for example, Guerriero, Citation2014; Hooks, Citation2010; Zepke, Citation2013) have noted that self-regulated reading builds the confidence of students and aids in participatory pedagogy. A similar observation is proffered by Amua-Sekyi (Citation2011) that lecturers express difficulties in engaging students in class discussion due to students’ failure to read before class. Finally, the reference of students to read articles from scholarly journals shows that they consider digital literacy to be a vital pedagogical practice in HE.

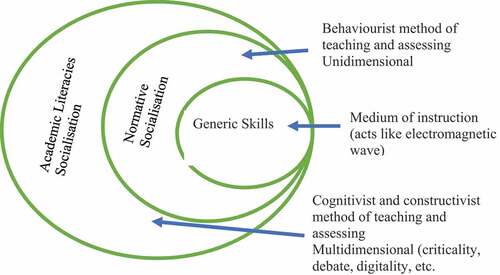

From the foregoing discussion, Lea and Street’s (Citation1998) academic literacies model can be reconceptualised. Reiteratively, in order to address the pedagogical limitations in Lea and Street’s (Citation1998) academic literacies model (see Lillis, Citation2003), we propose that the model should be renamed academic socialisation model. This means that HE is seen as a social world, where individuals are academically socialised differently. This model has three developmental overlapping academic writing orbitals: generic skills (considered as an electromagnetic wave), normative socialisation (regulatory pedagogy) and academic literacies socialisation (participatory pedagogy). We consider generic skills approach as electromagnetic wave because it is uncontestably transferable across all disciplinary fields, and it also helps build the skills of meaning making, argument and criticality. This is because if students lack proficiency in language and structure (GS), they cannot effectively engage in instructional discourse, build their own argument, reason well in the language, and project their own voice in classroom discourse. Thus, if grammatical structures such as punctuation, preposition, cohesion and coherence are poorly constructed, it largely affects meaning making. This means that language is the grounds for making meaning and building arguments in every discipline. Normative socialisation is considered because students are made to observe norms or conventions within their various disciplines. Academic literacies socialisation is used here because students are socialised not within a predefined set of norms in their disciplines, but within a multivariate set of skills, including meaning making, argument, criticality and digitality. This is illustrated in Figure .

5. Authors’ construct (2023)

These three orbitals are developmental and overlapping because normative socialisation is used as a pedagogical method to instruct learners in the medium of instruction (language and structure). This is where learners are submissively inducted within the norms of language. Learners accept the letters of the alphabet from A-Z and the accompanying amalgamation of these letters into words, phrases, sentences, paragraphs, and finally texts without having to question its reality. The electromagnetic wave of language (generic skills approach in the academic literacies model) are used to induct students in the principles of normative socialisation such as using language to help students to understand how lawyers, economists, and doctors write (disciplinary norms). The focus on academic literacies socialisation, where students take charge of their own learning by doing their own reading and making their own notes will give them the impetus to act independently in order to become knowledge generators and not merely consumers of knowledge (John, Citation2019). Thus, each model helps build knowledge in the other model, thereby explaining the developmental overlap of the model.

Furthermore, based on the results of the PAWP-P and AAWP-P presented in this study, it can be hypothesised that the kind of practices that students engage in prior to classroom discourse (known as PAWP-P) will influence the nature of instructional discourse in the classroom (referred to as AAWP-P). That is, if students commit themselves to reading the course outline, engage in reading, and make their own notes, it will enable lecturers to effectively utilise interactive instructional discourse or discussion in the classroom (see Extract 4), where students will have the capacity to ask useful questions and participate actively in the lesson (see Extract 10). However, if students fail to familiarise themselves with course outline by identifying certain crucial materials, read and make their own notes, it will limit their ability to ask useful questions and contribute meaningfully to the topic under consideration.

6. Conclusion and recommendations

Students’ success or their transition from one level to another level in the contemporary epistemologies of HE depends on their ability to participate in class discussion, build argument, and be critical. This implies that lecturers will not expect HE students to be passive in class and copy notes copiously from the lecturer as well as reproduce facts and replicate lecture notes in assignment or examination. For HE students to build argument and not uncritically follow norms, they should try to take charge of their own learning by acquainting themselves with the course outline, engaging in self-regulated reading and note making. This means that students are considered as co-generators or producers of knowledge with their lecturers and not mere consumers of knowledge. There is the likelihood that students will become passive in class if they fail to engage in the PAWP-P identified in this study.

Again, it can be concluded that students’ lack of digital literacy and proficiency in the regularities of electromagnetic wave (generic skills) of language will serve as a hindrance to their engagement in argument, debate and criticality, which seem to be core literacy practices in all disciplines of HE across the globe. This will limit their ability to developmentally progress in the academia. Therefore, HE is not a place, where students are taught to appreciate the fundamentals of language. Rather, the teaching of the concepts in the electromagnetic wave of language (identified in programmes such as EAP, WID, CS) in HE helps to enhance the already acquired proficiency at the pre-tertiary schools in order to help HE students engage in “critical reading and writing”. Further, lack of digital literacy will not help students to search and obtain quality information on the internet in order to read before attending lectures. Furthermore, the expectation of lecturers for students to read and make their own notes will inculcate in the students the ability to question and critique the existing knowledge within their various disciplines, which will enable them to develop novel knowledge and redesign existing knowledge.

Also, pedagogically, lecturers should try to sensitise students about the need to take initiative in generating their own knowledge; and lecturers who produce copious information (in the form of pamphlets, handouts, etc.) on the topics to be treated for the semester can be encouraged to minimise such practices. Moreover, management of institutions of higher learning should prioritise the teaching of Information Literacy in Level 100 in order to give students ample time to internalise the skills of searching and retrieving information from the internet so as to enhance their digital literacy in order to help them to generate their own information. Again, the teaching of Communicative Skills (known elsewhere as EAP, WID, etc.), should be increased to two academic years to enable students to internalise knowledge of the electromagnetic wave of language; or entrance examinations should be written in English before entry into the university, especially universities in Ghana, where English is used as a second language. This will help lecturers in the various disciplines to pay considerable attention to the development of disciplinary knowledge and students’ criticality and not to waste time on students’ use of language in their (students) writing. Finally, this study considered lecturers’ view on ideal writing practices, future research can consider students’ preferences for what lecturers consider ideal pedagogical practices in HE.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate academic and non-academic staff of the Departments of English, History and Religion and Human Values in the University of Cape Coast for their assistance and support during data collection.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings are embeded in the study.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Tabiri Francis

Tabiri Francis is an Assistant Lecturer at the Department of Arts Education, University of Cape Coast. His research interests include Academic Writing (AW), Academic Literacies Studies (ALS), Curriculum Studies (CS), Teaching English as a Second Language, and Critical Genre Studies (GS).

Joseph Benjamin Archibald Afful

Joseph Benjamin Archibald Afful is Full Professor of Applied English Linguistics at the Department of English, University of Cape Coast. His research interests include Academic Literacies Studies/English for Academic and Publishing Purposes, Genre Studies, Grammar of Interpersonality, and Naming and Address Practices.

References

- Afful, J. B. A. (2007). Academic literacy and communicative skills in the Ghanaian university: A proposal. Nebula, 4(3), 141–15. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/26469976

- Amua-Sekyi, E. K. (2011). Developing criticality in the context of mass higher education: Investigating literacy practices on undergraduate courses in Ghanaian universities. Unpublished doctoral thesis, University of Sussex. http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/

- Bandura, A. (1991). Social cognitive theory of self-regulation. Organizational Behaviour and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 248–287. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90022-L

- Barton, D., & Hamilton, M. (1998). Local literacies. Routledge.

- Boughey, C., & McKenna, S. (2017). Analysing an audit cycle: A critical realist account. Studies in Higher Education, 42(2), 963–975. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2015.1072148

- Burke, A., & Hardware, S. (2015). Honouring ESL students’ lived experiences in school learning with multiliteracies pedagogy. Language, Culture & Curriculum, 28(2), 143–157. https://doi.org/10.1080/07908318.2015.1027214

- Canagarajah, S., & Canagarajah, S. (2017). The Taylor and Francis handbook of migration and language. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315754512

- Coffin, C., & Donohue, J. P. (2012). Academic literacies and systemic functional linguistics: How do they relate? Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 11(1), 64–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2011.11.004

- Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2018). Research methods in education (8th ed.). Routledge Falmer. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315456539

- Conradie, T. (2009). Scaffolding an intervention for essay writing. Journal for Language Teaching, 43(2), 37–49. https://doi.org/10.4314/jlt.v43i2.56970

- Davison, D., Beach, R., Bowen, M., Daar, K., Sampat, M., & Wely, M. (2017). The course outline of record: A curriculum reference guide revisited. Retrieved from courseoutlineofrecordrevisited20171.pdf.

- Etsey, K., & Ocran, J. S. (2020). English methodology. University of Cape Coast Press.

- Freire, P. (2010). Pedagogy of the oppressed. The Continuum International Publishing Group Inc.

- Gimenez, J., & Thomas, P. (2015). A framework for usable pedagogy: Case studies towards accessibility, criticality and visibility. In T. Lillis, K. Harrington, M. Lea, & S. Mitchell, Eds. Working with academic literacies: Case studies towards transformative practice, perspectives on writing (pp. 25–44). Retrieved fromhttp://wac.colostate.edu/books/lillis/https://doi.org/10.37514/PER-B.2015.0674.2.01

- Gorska, F. W. K. 2018 Ways with writing: An ethnographically oriented study of student writing support in higher education in the UK. Unpublished doctoral thesis. King’s College London

- Greco, D. C. (2015). Multimodality into Schools. Unpublished master’s thesis, State University of New York.

- Greenfield, J. S. (2015). Beyond information: College choice as a literacy practice. Unpublished doctoral thesis, City University of New York.

- Guerriero, S. (2014). Teachers’ pedagogical knowledge and the teaching profession. Teaching & Teacher Education, 2(1), 7. http://www.oecd.org/edu/ceri/Background/document

- Hassel, S., & Ridout, N. (2018). An investigation of first-year students’ and lecturers’ expectations of university education. Frontier in Psychology, 8, 2218. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02218

- Hooks, B. (2010). Teaching critical thinking: Practical wisdom. Routledge.

- Hyland, K. (2002). Specificity revisited: How far should we go now? English for Specific Purposes, 21(4), 385–395. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0889-4906(01)00028-X

- Ivanič, R. (2004). Discourses of writing and learning to write. Language and Education, 18(3), 220–245. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500780408666877

- Janks, H. (2010). Literacy and power. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203869956

- Janks, H. (2012). The importance of critical literacy. English Teaching: Practice & Critique, 11(1), 150–163. http://education.waikato.ac.nz/research/files/etpc/files/2012v11n1dial1.pdf

- John, A. M. (2019). ESL teachers’ experiences and perceptions of developing multilingual learners’ academic literacies. Unpublished doctoral thesis, Indiana University of Pennsylvania.

- Knowles, M. S. (1980). The modern practice of adult education: From pedagogy to andragogy (2nd ed.). Cambridge Books.

- Lancaster, Z. (2016). Expressing stance in undergraduate writing: Discipline specific and general qualities. Journal of English for Specific Purposes, 23, 16–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2016.05.006

- Lea, M., & Street, B. (2006). The academic literacies model: Theory and applications. Theory into Practice, 45(4), 368–377. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15430421tip4504_11

- Lea, R., & Street, V. B. (1998). Student writing in higher education: An academic literacies approach. Studies in Higher Education, 23(2), 157–166. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079812331380364

- Lillis, T. (2003). Student writing as academic literacies: Drawing on bakhtin to move from critique to design. Language and Education, 17(3), 192–207. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500780308666848

- Lu, J. (2012). Autonomous learning in tertiary university EFL teaching and learning of the people’s republic of China. International Journal of Information and Education Technology, 2(6), 608–610. https://doi.org/10.7763/IJIET.2012.V2.215

- Merriam, S. B. (2001). Andragogy and self-directed learning: Pillars of adult learning theory. New Directions for Adult & Continuing Education, 89(89), 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1002/ace.3

- Olivier, L. (2016). The effect of an academic literacy course on first-year student writing: A case study. Unpublished doctoral thesis, North-West University,

- Olsson, E. M., Gelot, L., Karlsson Schaffer, J., & Litsegård, A. (2021). Teaching academic literacies in international relations: Towards a pedagogy of practice. Teaching in Higher Education, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2021.1992753

- Patton, M. Q. (2014). Qualitative research & evaluation methods: Integrating theory and practice (4th ed.). Sage.

- Russell, D., Lea, M., Parker, J., Street, B., & Donahue, T. (2009). Exploring notions of genre in academic literacies and writing across the curriculum: Approaches across countries and contexts. In C. Bazerman, A. Bonini, & D. Figueiredo, Eds. Genre in a changing world: Perspectives on writing. WAC Clearinghouse/Parlor Press (pp. 397–350). https://doi.org/10.37514/PER-B.2009.2324.2.20

- Scholtz, D. (2016). Improving writing practices of students’ academic literacy development. Journal for Language Teaching, 50(2), 37–55. https://doi.org/10.4314/jlt.v50i2.2

- Scott, M., Bloommaert, J., Street, B., & Turner, J. (2007). Academic literacies: What have we achieved and where to from here? Journal of Applied Linguistics, 4(1), 137–148. https://doi.org/10.1558/japl.v4i1.137

- Simpson, J. (2018). Participatory pedagogy in practice: Using effective participatory pedagogy in classroom practice to enhance pupil voice and educational engagement. Global Learning Programme (GLPS).

- Stordy, P. Taxonomy of literacies. (2015). Journal of Documentation, 71(3), 456–476. Retrieved from. https://doi.org/10.1108/JD-10-2013-0128

- Tsegay, M. S., Zegergish, M. Z., & Ashraf, M. A. (2020). Pedagogical practices and students’ experiences in Eritrean higher education institutions. Higher Education for the Future, 5(1), 90–103. https://doi.org/10.1177/2347631117738653

- Tuck, J. (2013). An exploration of practice surrounding student writing in the disciplines in UK higher education from the perspectives of academic teachers. Unpublished doctoral thesis, The Open University,

- Twagilimana, I. (2013). Conceptualisation and teaching of academic writing in an ESL context: A case study with first year university students. Unpublished doctoral thesis, University of the Witwatersrand,

- Twagilimana, I. (2017). Teaching academic writing to first year university students: A case study of feedback practices at the former National University of Rwanda. Rwanda Journal, Series A: Arts and Humanities, 2(1), 75–100. https://doi.org/10.4314/rj.v2i1.6A

- Wong, B., & Chiu, T. Y. (2018). University lecturers’ construction of the ‘ideal’ undergraduate student. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 44(1), 54–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2018.1504010

- Zepke, N. (2013). Student engagement: A complex business supporting the first year experience in tertiary education. The International Journal of the First Year in Higher Education, 4(2), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.5204/intjfyhe.v4i2.183