Abstract

Digital entrepreneurship is an interesting study in developed and developing countries as it plays a radical role in changing the economic landscape and facilitates creativity and innovation efforts for the growth of new entrepreneurs. This study aims to examine how digital entrepreneurship knowledge affects the digital entrepreneurial intentions of students. This research also explores the role of digital entrepreneurial alertness in mediating this relationship. We used a cross-sectional survey with a quantitative approach to convey the proposed hypotheses. A self-administrated survey of universities in Indonesia has participated in this survey. Later, the collected data were estimated using partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) with SmartPLS version 3.0. The results of this study indicate that digital entrepreneurial education and digital entrepreneurial knowledge can promote students’ digital entrepreneurial intentions. The findings also remark a significant effect of digital entrepreneurial alertness as a moderating variable for digital entrepreneurial education, digital entrepreneurial knowledge and students’ digital entrepreneurial intentions. This research provides insights linked to psychological dimensions in the form of digital entrepreneurial knowledge and digital entrepreneurial alertness as one of the predictor variables, as well as mediators for enhancing students’ digital entrepreneurial intention.

Public Interest Statement

As we move further into the digital age, entrepreneurship is evolving alongside it. Digital entrepreneurship presents an exciting opportunity for innovators and businesses to leverage the power of technology to create new products, services, and ways of doing business. Digital entrepreneurship offers a pathway to success and fulfillment for students passionate about creating positive change. Thus, the role of entrepreneurship education cannot be undeniable since entrepreneurship education can help students navigate the challenges of digital entrepreneurship. With their skills, knowledge, and creativity, students have the potential to create a lasting impact on the world.

1. Introduction

Digital entrepreneurship (DE) is a topic of growing interest to many scholars today because of its crucial role in shaping the economic landscape and conventional entrepreneurial paradigms (Dutot & Van Horne, Citation2015; Satalkina & Steiner, Citation2020; Soluk et al., Citation2021). Several studies also recognized the significant advantages offered by DE, including convenience for creativity and the creation of innovations that are essential in entrepreneurship activities (Anim-Yeboah et al., Citation2020; Kraus et al., Citation2018). Therefore, scholars in the sphere strongly concern on the study of DE and how to enhance the number of entrepreneurs taking part in DE. It provides students with opportunities to develop important skills, create job opportunities, and innovate in a rapidly changing world (Alferaih, Citation2022). In doing so, the universities need to respond to this issue by promoting entrepreneurship education as an attempt to initiate new digital business creation among university graduates.

The shift from conventional to digital entrepreneurship is undeniable. This condition brings more opportunities for entrepreneurship to involve digital platforms, especially elaborating the internet, mobile technology, and digital media, that support the development of new business models (Autio et al., Citation2018; Mivehchi, Citation2019). The next advantage of digitalization is that the adoption of innovative technology provides fast-paced information transfer. Through digitization, it makes easier for effective and efficient business processes and activities (Allen, Citation2019; Younis et al., Citation2020). Additionally, digital networks significantly impact research and business development strategies. These opportunities raise digital entrepreneurship prominent and increase the potential for new business creation, primarily in students’ businesses (Kraus et al., Citation2018).

In addition, a number of studies have noted that many opportunities for entrepreneurial activity are stimulated through digitization (Hull et al., Citation2007; Kraus et al., Citation2018). Therefore, entrepreneurs must be aware of and ready to take advantage of these opportunities. In this regard, students also have the same potential to initiate new digital businesses. In digital entrepreneurship activities, various digital competencies are needed to be adaptive and incorporate multiple technologies and digital innovation. Later, digital entrepreneurship education and training can maximize adequate knowledge related to digital entrepreneurship (Nambisan, Citation2017; von Briel et al., Citation2021). Like technological innovation, knowledge gained through digital entrepreneurship education is an essential and strategic resource for increasing established businesses and startups through digital platforms (Richter et al., Citation2017).

Concerning Indonesia, digital entrepreneurship education (DEE) can potentially increase the number of digital entrepreneurs, primarily university graduates. This is essential since unemployment is the main challenge in Indonesia and other countries. A recent survey from Kusnandar (Citation2023) reported that university graduates contribute to approximately 7.99 percent of total unemployment. Additionally, the data from the Indonesian Ministry of Information (Citation2022) indicated that the number of digital entrepreneurs in Indonesia in 2022 is insufficient, amounting to approximately 9.900 entrepreneurs, and the Indonesian government is targeting around 30 million entrepreneurs to switch to digital platforms by 2024. The university graduates are forecasted to be motors in promoting new business creation, primarily from the faculty of economics and students that obtained entrepreneurship education.

Considering these opportunities, the enhancement of students’ digital businesses can have the potential to increase their economic wellbeing. Therefore, this study aims to investigate the influence of digital entrepreneurship education, digital entrepreneurial knowledge, and digital entrepreneurial intention among university students in Indonesia, as well as examine the role of entrepreneurial alertness as a mediator. This present study offers at least three important insights. First, we combine the theories of planned behavior (Ajzen, Citation1991), entrepreneurial human capital (Bates, Citation1990), and social cognitive theory (Bandura, Citation2001) to explain the crucial predictors of intention to become a digital entrepreneur through the university lens. Second, it provides insight into the vital role of digital entrepreneurial alertness as a mediating influence of education and knowledge on the intention to become a digital entrepreneur, whose model has been ignored by scholars in the field of entrepreneurship before. Third, provide critical input to stakeholders and universities in Indonesia to optimize digital entrepreneurship education to increase the number of digital entrepreneurs among university graduates.

The rest of the paper presents the literature review and hypothesis in Section 1, followed by the method and materials in Section 2. Section 3 concerns the result of the study and the discussion in Section 4. The last section deals with conclusions.

2. Literature review

2.1. Digital entrepreneurship education, knowledge and digital entrepreneurial intention

The digital entrepreneurship intention (DEI) model is inseparable from Ajzen’s (Citation1991) theory of planned behavior (TPB) which focuses on how perceived intentions and feasibility can be explained by precursors, such as education, experience, and the environment, which can influence perceptions of feasibility. Ajzen’s intention model assumes that several variables directly affect the intention to perform a particular behavior, while external variables such as demographics and educational background do not directly affect the individual’s intentions (Ajzen, Citation1991; Linan, Citation2004). However, TPB is still considered a relevant and robust theory for explaining DEI. TPB also considers entrepreneurship education as a prominent predictor of entrepreneurial intentions (Hasan et al., Citation2017). This is inseparable from the robust role of education, which not only provides insight into knowledge related to entrepreneurship but also develops attitudes, self-efficacy, and sensitivity to intention.

Therefore, it raises a continuous debate among scholars on whether or not entrepreneurship education can enhance individual intentions for business (Ahmed et al., Citation2020; Linan, Citation2004). It becomes more complex when incorporating the economic and business context in which an individual may have previously practiced entrepreneurship. While a prior study noted that entrepreneurship education is still relatively new and should be adopted in public schools instead of vocational or university-based entrepreneurship (Rauch & Hulsink, Citation2015). It is therefore advisable to understand the noticeable contradictions and to investigate the role of individual experiences and practices in entrepreneurship. Some recent studies believe that entrepreneurship education can provide knowledge and mindsets, which in turn affect innovative activities and risk-taking in business (Karyaningsih et al., Citation2020; Wardana et al., Citation2020). To determine whether students’ behavior has shifted, it would be useful to consider entrepreneurial learning in the dimensions of affective, cognitive, and skills-based outcomes (Ratten & Usmanij, Citation2021; Saptono et al., Citation2021).

With the advancement of digital-based tools, it is crucial for entrepreneurship education to elaborate conventional teaching materials with technology. The shift from conventional entrepreneurship education to digital entrepreneurship intention (DEE) is marked by content adaptation within the framework of equipping students with how to initiate a new business, recognize entrepreneurial opportunities, and initiate a digital business (Nowinski et al., Citation2019; Ratten & Usmanij, Citation2021). DEE provides knowledge about how to build a business on a digital platform and provides a new perspective on what the digital entrepreneurial lifestyle is, how it can be linked to their present way of life, and how its diversity needs to be considered in digital entrepreneurship education (Clinkard, Citation2018).

Some preliminary studies (e.g., Roxas, Citation2014; Younis et al., Citation2020) have reported the important role of DEE in enhancing digital entrepreneurial knowledge (DEK). Referring to entrepreneurial human capital (EHC), the importance of knowledge gained from student entrepreneurship education can promote their intention for entrepreneurship (Karyaningsih et al., Citation2020). Entrepreneurial knowledge has been acknowledged to support students in running their digital businesses, negotiation, product development, and risk assessment (Xie et al., Citation2018; Shane & Nicolaou, Citation2013). In the context of digital entrepreneurship, entrepreneurs with adequate digital knowledge can develop better products or services to meet market tastes and demands. This digital entrepreneur will also be more obedient in dealing with opportunities, carrying change, and employing resources optimally and effectively. Likewise, DEK is built through effective entrepreneurship education and provides students with various digital knowledge (Secundo et al., Citation2021). Recent literature has confirmed the entrepreneurial knowledge that influences the birth of startups and the development of new digital businesses (Xie et al., Citation2018). The connectivity between entrepreneurial knowledge and entrepreneurial intention was revealed by some prior studies (e.g., Richter et al., Citation2017; Tshikovhi & Shambare, Citation2015).

Furthermore, the diversity of approaches in DEE aims to provide a variety of experiences and guide students to learn specific skills and knowledge in real-world settings (Ferreira et al., Citation2018). This diverse approach in DEE also equips students with openness to various changes, a willingness to alter to new circumstances, and the ability to work in a clearly uncertain digital platform environment (Kickul et al., Citation2018). The diversity of approaches also emphasizes the role of cultural differences in learning (Bandera et al., Citation2018; Mukhtar et al., Citation2021). Equally important, Ratten and Usmanij (Citation2021) noted the use of technology in digital entrepreneurship learning, such as the use of robots, artificial intelligence (AI), and automated technology in teaching, so that it is more innovative and stimulates student interest. In DEE, students are also given skills on how to access and utilize big data, which was previously unknown in conventional models (Kickul et al., Citation2018). The use of mobile technology and the internet of things has allowed individuals to retrieve knowledge and learn from any geographic environment.

A prior study by Jena (Citation2020) remarked that an effective DEE, accompanied by systematic practice, has a significant impact on student intentions. The study of Ho et al. (Citation2018); Jena (Citation2020) reported that DEE can affect the performance of entrepreneurs by increasing their profitability, entrepreneurial spirit, entrepreneurial attitude, and survival opportunities. Bischoff et al. (Citation2018) and Ahmed et al. (Citation2020) noted that DEE is still an effective instrument used to increase entrepreneurial activity. Therefore, universities are currently competing to optimize the role of entrepreneurship education to assist their graduates with the specialized knowledge needed for the effective creation and successful sustainment of entrepreneurial activities. However, policies and attempts to enhance entrepreneurial attitudes, intentions, and activities among students are neglected by a lack of shared comprehension of educational goals, content, methodologies, and resources required to enlarge entrepreneurship. Thus, the hypotheses are presented below.

H1:

DEE positively impacts DEI

H2:

DEE positively impacts DEK

H3:

DEK positively impacts DEI

2.2. Digital entrepreneurial alertness and digital entrepreneurial intention

Entrepreneurial alertness was first coined by Kirzner (Citation1979) as one’s ability to seek new opportunities that others ignore. Entrepreneurial alertness is a dimension of assessment that concerns investigating recent changes, shifts, and information and determining whether they will show business opportunities with potential profit. Entrepreneurial alertness covers some dimensions: scanning and searching for information, linking prior knowledge, and evaluating the presence of a desk business opportunity. Entrepreneurial alertness is part of the entrepreneurial mindset (Cui & Bell, Citation2022). As part of the entrepreneurial mindset, entrepreneurial alertness is an entrepreneurial cognition process that involves scanning and searching for warnings, warning associations and connections, and evaluation and assessment related to opportunity information (Cui & Bell, Citation2022; Tang et al., Citation2012).

Later, entrepreneurial alertness can enhance awareness of opportunities and provide sharp insight into identifying the existence of entrepreneurial opportunities. The process of entrepreneurship begins with the recognition of opportunities. However, prior recognition and awareness of opportunity are also notable factors (Krueger et al., Citation2000). Several studies, for instance, Cui and Bell (Citation2022) and George et al. (Citation2016), reported that the higher a person’s entrepreneurial alertness, the better they will recognize opportunities, even without active involvement to observe or look for them. Furthermore, entrepreneurial alertness works on some capacities and processes, including preliminary knowledge, pattern recognition skills, and information processing (Li et al., Citation2015). Moreover, the knowledge and soft skills that form the basis of this awareness are learned and developed through entrepreneurship education.

A prior study by Cui and Bell (Citation2022) found that scanning for warnings and seeking opportunities is the fruit of learning, as well as experience in the process of developmental cognition. Therefore, entrepreneurship education has an impact on the growth and development of entrepreneurial alertness. The basic theory that strongly explains the connectivity between entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial alertness is the social cognitive theory (SCT) performed by Bandura (Citation2001). SCT revealed an interaction between cognitive variables, environmental dimensions, and human behavior. This individual’s cognitive ability will be stronger with maximum support from parents, educators, peers or the community, and the surrounding environment (Bandura, Citation2001). In summary, SCT states that there are several factors such as environment, inspiration, values, mindset, and behavior that can help predict and evaluate behavior change (Lin & Huang, Citation2008).

Studies on the theme of entrepreneurial alertness were first conducted by Kirzner (Citation1979), who characterized more alert individuals as having “antennae” that allow gap recognition with limited clues. Kirzner (Citation1979) noted that entrepreneurial alertness includes creative and imaginative involvement and can influence the types of transactions that will be proposed in future market periods. A study by Kirzner (Citation1979) pointed out that individuals who have high entrepreneurial alertness consistently scan the environment and are better equipped to find opportunities. Furthermore, the study by Younis et al. (Citation2020) noted that digital entrepreneurship knowledge (DEK) has an effect on digital entrepreneurship intentions (DEI). The study of Dutot and Van Horne (Citation2015) also found the impact of digital entrepreneurial alertness and entrepreneurial characteristics on DEI. Therefore, the hypotheses are presented as follows.

H4:

DEE positively impacts DEA

H5:

DEK positively impacts DEA

H6:

DEA positively impacts DEI

H7:

DEA mediates the impact of DEE and DEI

H8:

DEK mediates the impact of DEE and DEI

H9:

DEA mediates the impact of DEK and DEI

3. Method and materials

This research used a cross-sectional survey with a quantitative approach to deal with the hypothesis formulated earlier through structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). In more precise, this study attempts to confirm how DEE directly affects DEI, and also indirectly through DEA as a moderating variable (see Figure ).

The basic usage of structural equation modelling (SEM) in path analysis with mediation. The causal relationships include both indirect and direct effects, where DEA is a mediator (modified from Tang et al., Citation2012; Vejayaratnam et al., Citation2019).

3.1. Sampling and data collection

Indonesian university students are suitable respondents in this study. The study was performed at selected universities in Malang (East Java), Semarang (Central Java), and Jakarta (West Java). The determination of these universities considering the representativeness of the geographical areas. The determination sample in those universities also considers that Universitas Negeri Malang, Universitas Negeri Semarang, and Universitas Negeri Jakarta have entrepreneurial laboratories. This research incorporated convenience sampling, which is frequently used in entrepreneurship studies (Nowinski et al., Citation2019). We used online surveys with the Microsoft Forms platform to gather data. The research instrument in the form of a questionnaire was distributed to participants using students’ email and WhatsApp group in May—July 2022, and we followed up two weeks later. The respondents of this study were students at several universities in Malang, Semarang, and Jakarta who had attended entrepreneurship education, economic education, and were actively involved in entrepreneurial activities organized by their campuses. The respondents recruited in this study were voluntary, and we will keep their identities anonymous. From the approximately 455 participants who participated in this survey, we found that 411 (90.32 percent) had completed the questionnaires. The complete profile of the participants in this research can be seen in Table .

Table 1. The characteristics of respondents

3.2. Measurement and data analysis

This adapted the construct and items of questionnaires from a number of relevant literature and studies. To measure DEA, we adopted the 13 items developed by Tang et al. (Citation2012), while to estimate DEK, we adopted six items from the studies of Roxas (Citation2014) and Younis et al. (Citation2020). Furthermore, to measure DEE, we adopted nine items from the study conducted by Hasan et al. (Citation2017). Finally, to test DEI, we used eight items developed in the studies of Linan (Citation2004) and Vejayaratnam et al. (Citation2019). The study employed a Likert scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) to represent the respondent’s answers. Furthermore, the collected data were further tested at various stages, including measurement model, structural model, and hypothesis testing using partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) following the procedures from Hair et al. (Citation2019) and Hair et al. (Citation2020).

4. Results

4.1. Demographic respondents

Table informs that the majority of participants who took part in this survey were female students, as much as 60.83 percent. Capturing from the study level, the participants of this study were also dominated by students in the 2018 batch (53.77 percent), while the rest came from the students of the 2019 batch (46.23 percent). Furthermore, respondents whose parents are entrepreneurs are in the first place (47.45 percent), while the least number are civil servants (9.98 percent). Table also exhibits that the most of respondents are economics education majors (57.17 percent), while the least are accounting majors (11.69 percent). A summary of the characteristics of respondents is presented in Table .

4.2. Outer model evaluation

A series of PLS-SEM procedures from Hair et al. (Citation2020) were used to analyze the collected data. The first procedure of the test is convergent validity. Hair et al (Citation2013, Citation2020). provided a threshold value of loading factor > 0.70 as a condition for the variable to meet convergent validity. As reported in Table , it is known that of the 13 items of the digital entrepreneurship alertness (DEA) variable, 10 of them have a loading factor value (λ) between 0.719 and 0.869 (>0.70), indicating the value is higher than the threshold to meet convergent validity. While the remaining three items (DEA1, DEA4, and DEA5) must be dropped since the loading factor is smaller than 0.70. Furthermore, of the nine items of the digital entrepreneurship education (DEE) variable, five of them passed the threshold (>0.70), indicating to accomplish the convergent validity. At the same time, the remaining DEE items (DEE3, DEE6, DEE8, and DEE9) must be dropped because they are smaller than 0.70. Likewise, of the eight items of the digital entrepreneurship intention (DEI) variable, only one does not meet convergent validity because its value is less than the cut-off value (DEI4 < 0.70). Lastly, like the DEI variable, the digital entrepreneurship knowledge (DEK) variable is also one item that does not pass convergent validity (DEK6 < 0.70).

Table 2. Outer model estimation

The next procedure is discriminant validity evaluation, following the criteria from Fornell and Larcker (Citation1981). The value of cross-loading for each variable should be higher than the cut-off value of 0.70 to meet discriminant validity. Table reports that the cross-loading value of the DEA, DEE, DEK, and DEI variables is higher than the threshold, indicating that to meet discriminant validity criteria. This study also involved the heterotrait-monotrait ratio (HTMT). According to the results of the HTMT test, the variables DEA, DEE, DEI, and DEK have a ratio value of less than 0.90 to accomplish discriminant validity (see Table ).

Table 3. Discriminant Validity

Table 4. Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio

4.3. Inner model evaluation

After testing the outer model, we then tested the inner model, or structural model, according to the opinion of Hair et al (Citation2013, Citation2020). In the inner model test, we performed a series of procedures, including (1) the collinearity test, (2) the R-squared test, (3) the F-squared test, and (4) the Q-squared predictive test. The first procedure of collinearity test is intended to check whether the constellation between the variables tested is collinearity or vice versa (Hair et al., Citation2013). The value of the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) coefficient has met the threshold of less than 5.00 (Hair et al., Citation2013). Based on the examination of the VIF value matched with the VIF threshold (<5.00), it is known that the constellation of the variables we tested did not occur collinearity. Thus, the constellation of variables DEE, DEA, DEK, and DEI did not have collinearity. Table reports the results of the collinearity test, which proves that all indicators of the estimated constructs do not occur collinearity and can be processed in the next inner model analysis.

Table 5. Variance Inflation Factor (VIF)

The following procedure in the inner model is the R-Squared (R2) test, with the aim of seeing the strength or weakness of the prediction of the endogenous latent variables in the model we found. We use the benchmark R2 value as evidence of the power and accuracy of the prediction of endogenous variables to the model (Hair et al., Citation2013). From the R2 estimation, it is understood that DEK has a value of 0.444, which indicates that 44.4 percent of the DEK variant can be performed by DEE with a moderate level of prediction. Furthermore, DEA has an R2 value of 0.753, which indicates that DEE and DEK can explain 75.3 percent of the DEA variance with a strong predictive level. Finally, DEI has an R2 value of 0.738, which remarks that 73.8 percent of the DEI variance can be explained by DEE, DEK, and DEA with a strong predictive level.

The third procedure is to estimate the effect/influence size (f2). In this study, we use the suggestions from Hair et al. (Citation2013), as a threshold value of f2. The f2 estimation shows that DEE and DEK have an effect on DEA at a large/wide level (f2 value = 0.799). Similarly, DEE, DEK, and DEA have an effect on DEI at a large/wide level (f2 value = 0.788). The fourth procedure, the value of Q2 >0 (zero), shows that the model has predictive relevance. On the other hand, the value of Q2 <0 reveals that the model lacks predictive relevance. The calculation remarks that the Q2 value of the DEE, DEK, DEA, and DEI variables is greater than 0, so it can be concluded that the model has predictive relevance.

Lastly, we perform a goodness of fit model in a fixed manner based on the research findings. Hair et al (Citation2013, Citation2020). provided the rule of thumb for the goodness of fit, namely Cronbach’s Alpha (α) > 0.70, composite reliability (CR) > 0.70, and Average Variance Extracted (AVE) > 0.50. The information in Table deals with the model of fit and it shows that the values of, CR, and AVE of our model meet the threshold of the model fit. Thus, our structural and measurement model can be stated as good or fit.

Table 6. Evaluation Result of Goodness of Fit for Outer Model

4.4. Hypothesis testing

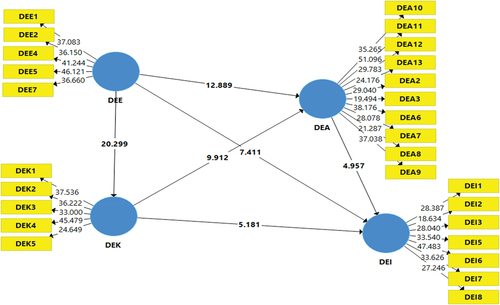

We tested the hypothesis referring to the results of the model using the SEM-PLS bootstrap resampling method. In testing the hypothesis, we used a t-test threshold where t-count >1.645 with one-tailed, and p-value <0.050. Testing the indirect relationship between variables, we refer to Preacher and Hayes (Citation2008) that there is a mediating effect if the lower level (LL) 5% and upper level (UL) 95% do not exceed 0. Table and Figure informs that all the hypotheses we tested accepted, because (t-value ranges from 4.479–20.299 1.645 and p-value 0.000 < 0.050). Table and Figure also informs that of the nine hypotheses tested, the highest t value is on the effect of DEE on DEK (20,299), while the lowest t value is on the indirect effect of DEE on DEI through DEA. Based on Table , it is also known that DEA was successful in mediating the effect of DEE and DEK on DEI. Similarly, DEK was successful in mediating the effect of DEE on DEA and on DEI.

Table 7. The Summarize of Hypothesis Testing

The structural model is performed using Smart PLS. The abbreviation used in this model, including DEI (digital entrepreneurial intention), DEA (Digital entrepreneurship alertness), DEE (Digital entrepreneurship education), and DEK (Digital entrepreneurial knowledge)

5. Discussions

This research attempted to investigate how digital entrepreneurship education (DEE) influences digital entrepreneurial intention (DEI) directly or mediated by digital entrepreneurial knowledge (DEK) and digital entrepreneurial alertness (DEA). We put forward nine hypotheses, and all of them were accepted. Thus, the discussions of this study are presented below.

The first result demonstrates that DEE has an effect on the DEI of university students in Indonesia. The findings of this study strengthen the majority of scholars in the developed countries who study the constellation of DEE against DEI (e.g., Hasan et al., Citation2017; Linan et al., Citation2018; Linan, Citation2004), as well as in the Indonesian context (Karyaningsih et al., Citation2020; Saptono et al., Citation2021). The results are also in line with the findings of Nowinski et al. (Citation2019); Ratten and Usmanij (Citation2021), which remarked that DEE has an effect on DEI. The rationale behind this finding is that DEE has the biggest influence on students’ decisions to become digital entrepreneurs. In this regard, DEE not only equips them with knowledge related to digital platforms as a business environment but also provides a set of skills for establishing a digital-based business. The findings confirmed social cognitive theory, which suggests some theoretical underpinning for this relationship. In summary, this study offers to maintain DEE as an effective predictor of DEI for university students.

In addition to influencing DEI, the empirical results of this present study show that DEE has a significant role in influencing DEK and DEA. DEE covers both materials related to the basic concepts of entrepreneurship and elaborates on digitalization in dealing with the digital market in the fourth industrial era. Therefore, students who enroll in DEE will acquire knowledge in entrepreneurship (DEK), and this finding confirms some consensus that shows this relationship (e.g., Cui & Bell, Citation2022; Linan et al., Citation2018; Roxas, Citation2014). On the other hand, DEE provides students with a set of knowledge related to entrepreneurship. The basic materials of entrepreneurship education (e.g., business, opportunities, digital entrepreneurship, funding, market search) can promote students’ alertness to new digital business opportunities. This study extends entrepreneurial human capital (Bates, Citation1990), in which DEE promotes better understanding, knowledge (DEK), and alertness (DEA). The findings reinforce the previous study of Younis et al. (Citation2020) and offer insight into DEE being an effective predictor of DEK and DEI among university students in Indonesia.

Later, this result also indicates that there is a robust link between DEA and the DEI of Indonesian university students. The finding reinforces a number of preliminary works (e.g., Cui & Bell, Citation2022; George et al., Citation2016; Tang et al., Citation2012), which found a positive effect of this relationship. As part of the entrepreneurial mindset, DEA deals with the cognition process by scanning and searching for warnings, warning associations and connections, and evaluation and assessment related to opportunity information. This means that DEA is the ability to have sharp insight in identifying the existence of entrepreneurial opportunities. The process of entrepreneurship begins with the recognition of opportunities. This confirms some relevant studies by Cui and Bell (Citation2022) and George et al. (Citation2016), who noted that the greater an individual’s DEA, the more likely they are to succeed in initiating a business, including the intention of entrepreneurship with a digital platform.

In contrast to previous studies conducted in Indonesia (e.g., Karyaningsih et al., Citation2020; Saptono et al., Citation2021), our study presents new insights into the mediating roles of DEK and DEA for university students. The study found that DEK and DEA were successful in mediating the effect of DEE on DEI. The findings are reasonable because, with the roles of DEK and DEA, DEE has a stronger influence on the DEI of university students. This implies that DEI that is implemented effectively will increase students’ knowledge of digital entrepreneurship, and the increase in DEA will enhance the DEI of university students. The robust mediating roles of DEK and DEA in this research suggest that universities must manage DEE in a variety of ways. The diversity of approaches in DEE, in addition to providing a variety of experiences, also guides students to learn specific skills and knowledge in real-world settings (Ferreira et al., Citation2018).

In addition, the approach in DEE also equips students with openness to various changes, willingness to adapt to new circumstances, and, most importantly, the ability to work in a clearly uncertain digital platform environment (Kickul et al., Citation2018). No less importantly, the use of technology in digital entrepreneurship learning, such as the use of robots, artificial intelligence (AI), and automated technology in teaching, promotes innovation and stimulates student interest. Through DEE, students also acquire skills on how to access and utilize big data, which were ignored in conventional entrepreneurship education models. The utilization of mobile technology and the internet of things has allowed students to unlock knowledge and learn from any geographic location. This finding extends the theory of planned behavior by explaining how the intention of entrepreneurship can be promoted by several antecedent factors.

6. Conclusion

This current study aimed to examine how digital entrepreneurship education (DEE) and digital entrepreneurial knowledge (DEK) affect the digital entrepreneurial intentions (DEI) of Indonesian university students. Also, it investigated the mediation role of digital entrepreneurial alertness (DEA) in understanding the relationship between variables. The results of this study provide important notes on how psychological aspects (e.g., DEK and DEA) are able to become predictor variables as well as strong mediators for increasing students’ digital entrepreneurial intention. This study found that DEE was the dominant predictor of increases in DEK, DEA, and DEI. In addition, there is a robust link between DEA and DEI among university students in Indonesia. Thus, the findings provide theoretical implications regarding the involvement of entrepreneurial human capital theory and social cognitive theory in increasing the quantity and quality of students at various universities entering digital platform-based business establishments.

For practical implications, this study recommends elaborated digital entrepreneurship education using a diverse approach, such as the use of various technological means, artificial intelligence, highway data, and several supports in digital-based business activities. With this model, entrepreneurship education provides various knowledge and skills related to digital-based businesses. Like other papers, the limitation of our study is that it does not involve a full model of the theories of planned behavior, social cognitive theory, and entrepreneurial human capital. As a consequence, we cannot recommend in detail which predictors should receive special attention and have more impact than DEE on DEI. The further limitation is that we solely involve selected public universities in Indonesia in the areas of Jakarta, Semarang, and Malang, which limits generalizability. Thus, further research can involve more universities in various regions of Indonesia so that the research results can be generalized. Finally, our study solely took samples of students in management, economics, and accounting study programs. Future scholar scans will also involve students in various study programs so that the findings are more detailed, robust, and generalizable.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the Faculty of Economics, Universitas Negeri Jakarta, Indonesia to support this research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Agus Wibowo

Agus Wibowo is an associate professor of entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurship at the Faculty of Economics, Universitas Negeri Jakarta, Indonesia. His research interests include entrepreneurship, entrepreneurship education, and education.

Bagus Shandy Narmaditya

Bagus Shandy Narmaditya is an assistant professor of economics education at the Faculty of Economics and Business at Universitas Negeri Malang, Indonesia.

Ari Saptono

Ari Saptono is a professor of economic education assessment at the Faculty of Economics at Universitas Negeri Jakarta, Indonesia. His research interests include entrepreneurship education, entrepreneurship, and educational assessment.

Mohammad Sofwan Effendi

Mohammad Sofwan Effendi is an associate professor in education and educational management at the Faculty of Economics, Universitas Negeri Jakarta, Indonesia. His research interests include entrepreneurship, entrepreneurship education, and education.

Saparuddin Mukhtar

Saparuddin Mukhtar is a professor specializing in economics, small and medium enterprises, and entrepreneurship at the Faculty of Economics, Universitas Negeri Jakarta, Indonesia.

Muhammad Hakimi Mohd Shafiai

Muhammad Hakimi Mohd Shafiai is an associate professor of entrepreneurship, Islamic economics, and Islamic social finance at the Faculty of Economics and Management, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, Malaysia.

References

- Ahmed, T., Chandran, V. G. R., Klobas, J. E., Liñán, F., & Kokkalis, P. (2020). Entrepreneurship education programmes: How learning, inspiration and resources affect intentions for new venture creation in a developing economy. The International Journal of Management Education, 18(1), 100327. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2019.100327

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-59789190020-T

- Alferaih, A. (2022). Starting a new business? Assessing university students’ intentions towards digital entrepreneurship in Saudi Arabia. International Journal of Information Management Data Insights, 2(2), 100087. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jjimei.2022.100087

- Allen, J. P. (2019). Digital entrepreneurship. Routledge.

- Anim-Yeboah, S., Boateng, R., Awuni Kolog, E., Owusu, A., & Bedi, I. (2020, April). Digital entrepreneurship in business enterprises: A systematic review. In Conference on e-Business, e-Services and e-Society (pp. 192–203). Springer, Cham.

- Autio, E., Nambisan, S., Thomas, L. D., & Wright, M. (2018). Digital affordances, spatial affordances, and the genesis of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 12(1), 72–95. https://doi.org/10.1002/sej.1266

- Bandera, C., Collins, R., & Passerini, K. (2018). Risky business: Experiential learning, information and communications technology, and risk-taking attitudes in entrepreneurship education. The International Journal of Management Education, 16(2), 224–238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2018.02.006

- Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.1

- Bates, T. (1990). Entrepreneur human capital inputs and small business longevity. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 72(4), 551–559. https://doi.org/10.2307/2109594

- Bischoff, K., Volkmann, C. K., & Audretsch, D. B. (2018). Stakeholder collaboration in entrepreneurship education: An analysis of the entrepreneurial ecosystems of European higher educational institutions. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 43(1), 20–46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-017-9581-0

- Clinkard, K. (2018). Are employability and entrepreneurial measures for higher education relevant? Introducing AGILE reflection. Industry and Higher Education, 32(6), 375–390. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950422218808625

- Cui, J., & Bell, R. (2022). Behavioural entrepreneurial mindset: How entrepreneurial education activity impacts entrepreneurial intention and behaviour. The International Journal of Management Education, 20(2), 100639. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2022.100639

- Dutot, V., & Van Horne, C. (2015). Digital entrepreneurship intention in a developed vs. emerging country: An exploratory study in France and the UAE. Transnational Corporations Review, 7(1), 79–96. https://doi.org/10.5148/tncr.2015.7105

- Ferreira, J. J., Fayolle, A., Ratten, V., & Raposo, M. (2018). Introduction: The role of entrepreneurial universities in society. In Entrepreneurial universities. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(3), 382. https://doi.org/10.2307/3150980

- George, M. N., Parida, V., Lahti, T., & Wincent, J. (2016). A systematic literature review of entrepreneurial opportunity recognition: Insights on influencing factors. International Entrepreneurship & Management Journal, 12(2), 309–350. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-014-0347-y

- Hair, J. F., Jr., Howard, M. C., & Nitzl, C. (2020). Assessing measurement model quality in PLS-SEM using confirmatory composite analysis. Journal of Business Research, 109, 101–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.11.069

- Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2013). Partial least squares structural equation modeling: Rigorous applications, better results and higher acceptance. Long Range Planning, 46(1–2), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2013.01.001

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203

- Hasan, S. M., Khan, E. A., & Nabi, M. N. U. (2017). Entrepreneurial education at university level and entrepreneurship development. Education+ Training, 59(7/8), 888–906. https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-01-2016-0020

- Ho, M. H. R., Uy, M. A., Kang, B. N., & Chan, K. Y. (2018). Impact of entrepreneurship training on entrepreneurial efficacy and alertness among adolescent youth. In Jesus de la, F. (Ed.), Frontiers in education (Vol. 3, p. 13). March. Frontiers Media SA.

- Hull, C. E., Caisy Hung, Y. T., Hair, N., Perotti, V., & DeMartino, R. (2007). Taking advantage of digital opportunities: A typology of digital entrepreneurship. International Journal of Networking and Virtual Organisations, 4(3), 290–303. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJNVO.2007.015166

- Jena, R. K. (2020). Measuring the impact of business management Student’s attitude towards entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial intention: A case study. Computers in Human Behavior, 107, 106275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106275

- Karyaningsih, R. P. D., Wibowo, A., Saptono, A., & Narmaditya, B. S. (2020). Does entrepreneurial knowledge influence vocational students’ intention? Lessons from Indonesia. Entrepreneurial Business and Economics Review, 8(4), 138–155. https://doi.org/10.15678/EBER.2020.080408

- Kickul, J., Gundry, L., Mitra, P., & Berçot, L. (2018). Designing with purpose: Advocating innovation, impact, sustainability, and scale in social entrepreneurship education. Entrepreneurship Education and Pedagogy, 1(2), 205–221. https://doi.org/10.1177/2515127418772177

- Kirzner, I. M. (1979). Perception, Opportunity and Profit. University of Chicago Press.

- Kraus, S., Palmer, C., Kailer, N., Kallinger, F. L., & Spitzer, J. (2018). Digital entrepreneurship: A research agenda on new business models for the twenty-first century. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 25(ahead–of–print), 353–375. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEBR-06-2018-0425

- Krueger, N. F., Jr., Reilly, M. D., & Carsrud, A. L. (2000). Competing models of entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Business Venturing, 15(5–6), 411–432. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(98)00033-0

- Kusnandar, V. B. (2023). Number of Open Unemployment Based on Graduated Education Level. Retrieved from https://databoks.katadata.co.id/

- Linan, F. (2004). Intention-based models of entrepreneurship education. Piccolla Impresa/Small Business, 3(1), 11–35.

- Linan, F., Ceresia, F., & Bernal, A. (2018). Who intends to enroll in entrepreneurship education? Entrepreneurial self-identity as a precursor. Entrepreneurship Education and Pedagogy, 1(3), 222–242. https://doi.org/10.1177/2515127418780491

- Lin, T. C., & Huang, C. C. (2008). Understanding knowledge management system usage antecedents: An integration of social cognitive theory and task technology fit. Information & Management, 45(6), 410–417. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2008.06.004

- Li, Y. U., Wang, P., & Liang, Y. J. (2015). Influence of entrepreneurial experience, alertness, and prior knowledge on opportunity recognition. Social Behavior & Personality: An International Journal, 43(9), 1575–1583. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2015.43.9.1575

- Ministry of Information. (2022). SMEs Upgrade Class—SMEs Go Digital. Retrieved from https://www.kominfo.go.id

- Mivehchi, L. (2019). The role of information technology in women entrepreneurship (the case of e-retailing in Iran). Procedia Computer Science, 158, 508–512. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2019.09.082

- Mukhtar, S., Wardana, L. W., Wibowo, A., Narmaditya, B. S., & Cheng, M. (2021). Does entrepreneurship education and culture promote students’ entrepreneurial intention? The mediating role of entrepreneurial mindset. Cogent Education, 8(1), 1918849. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2021.1918849

- Nambisan, S. (2017). Digital entrepreneurship: Toward a digital technology perspective of entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship: Theory & Practice, 41(6), 1029–1055. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12254

- Nowinski, W., Haddoud, M. Y., Lancaric, D., Egerova, D., & Czegledi, C. (2019). The impact of entrepreneurship education, entrepreneurial self-efficacy and gender on entrepreneurial intentions of university students in the Visegrad countries. Studies in Higher Education, 44(2), 361–379. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2017.1365359

- Nowinski, W., Haddoud, M. Y., Lančarič, D., Egerová, D., & Czeglédi, C. (2019). The impact of entrepreneurship education, entrepreneurial self-efficacy and gender on entrepreneurial intentions of university students in the Visegrad countries. Studies in Higher Education, 44(2), 361–379. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2017.1365359

- Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40(3), 879–891. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.40.3.879

- Ratten, V., & Usmanij, P. (2021). Entrepreneurship education: Time for a change in research direction? The International Journal of Management Education, 19(1), 100367. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2020.100367

- Rauch, A., & Hulsink, W. (2015). Putting entrepreneurship education where the intention to act lies: An investigation into the impact of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial behavior. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 14(2), 187–204. https://doi.org/10.5465/amle.2012.0293

- Richter, C., Kraus, S., Brem, A., Durst, S., & Giselbrecht, C. (2017). Digital entrepreneurship: Innovative business models for the sharing economy. Creativity and Innovation Management, 26(3), 300–310. https://doi.org/10.1111/caim.12227

- Roxas, B. (2014). Effects of entrepreneurial knowledge on entrepreneurial intentions: A longitudinal study of selected South-east Asian business students. Journal of Education & Work, 27(4), 432–453. https://doi.org/10.1080/13639080.2012.760191

- Saptono, A., Wibowo, A., Widyastuti, U., Narmaditya, B. S., & Yanto, H. (2021). Entrepreneurial self-efficacy among elementary students: The role of entrepreneurship education. Heliyon, 7(9), e07995. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e07995

- Satalkina, L., & Steiner, G. (2020). Digital entrepreneurship and its role in innovation systems: A systematic literature review as a basis for future research avenues for sustainable transitions. Sustainability, 12(7), 2764. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12072764

- Secundo, G., Gioconda, M. E. L. E., Del Vecchio, P., Gianluca, E. L. I. A., Margherita, A., & Valentina, N. D. O. U. (2021). Threat or opportunity? A case study of digital-enabled redesign of entrepreneurship education in the COVID-19 emergency. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 166, 120565. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2020.120565

- Shane, S., & Nicolaou, N. (2013). The genetics of entrepreneurial performance. International Small Business Journal, 31(5), 473–495.

- Soluk, J., Kammerlander, N., & Darwin, S. (2021). Digital entrepreneurship in developing countries: The role of institutional voids. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 170, 120876. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2021.120876

- Tang, J., Kacmar, K. M. M., & Busenitz, L. (2012). Entrepreneurial alertness in the pursuit of new opportunities. Journal of Business Venturing, 27(1), 77–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2010.07.001

- Tshikovhi, N., & Shambare, R. (2015). Entrepreneurial knowledge, personal attitudes, and entrepreneurship intentions among South African Enactus students. Problems and Perspectives in Management, 13(1), 152–158. https://www.businessperspectives.org/index.php/journals/problems-and-perspectives-in-management/issue-1-cont-4/entrepreneurial-knowledge-personal-attitudes-and-entrepreneurship-intentions-among-south-african-enactus-students

- Vejayaratnam, N., Paramasivam, T., & Mustakim, S. S. (2019). Digital Entrepreneurial Intention among Private Technical and Vocational Education (TVET) Students. The International Journal of Academic Research in Business & Social Sciences, 9(12), 110–120. http://dx.doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v9-i12/6678

- von Briel, F., Recker, J., Selander, L., Jarvenpaa, S. L., Hukal, P., Yoo, Y., Lehmann, J., Chan, Y., Rothe, H., Alpar, P., Fürstenau, D., & Wurm, B. (2021). Researching digital entrepreneurship: Current issues and suggestions for future directions. Communications of the Association for Information Systems, 48(1), 284–304. https://doi.org/10.17705/1CAIS.04833

- Wardana, L. W., Narmaditya, B. S., Wibowo, A., Mahendra, A. M., Wibowo, N. A., Harwida, G., & Rohman, A. N. (2020). The impact of entrepreneurship education and students’ entrepreneurial mindset: The mediating role of attitude and self-efficacy. Heliyon, 6(9), e04922. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04922

- Xie, K., Song, Y., Zhang, W., Hao, J., Liu, Z., & Chen, Y. (2018). Technological entrepreneurship in science parks: A case study of Wuhan Donghu High-Tech Zone. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 135, 156–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2018.01.021

- Younis, H., Katsioloudes, M., & Al Bakri, A. (2020). Digital entrepreneurship intentions of Qatar university students motivational factors identification: Digital entrepreneurship intentions. International Journal of E-Entrepreneurship and Innovation (IJEEI), 10(1), 56–74. https://doi.org/10.4018/IJEEI.2020010105