Abstract

This paper explored the status quo of gifted education in the Moroccan context. The Moroccan educational system remains subtle with regards to giftedness; thereby necessitating to question the communal understanding of gifted education. This study used a survey based upon open-ended responses on individualistic Moroccan perceptions from the educational field regarding gifted education, addressing giftedness and talents, distinguishing the gifted, valuing giftedness, supporting the gifted as well as raising awareness towards gifted education. These aspects deliver responses to the survey while reporting qualitative data thereby shedding light on the educational and learning resources, per se, in the Moroccan educational context. Tackling the given resources has reflected the trending interests in gifted education in Morocco, in comparison with other Arab countries as per the project led by the WGC in an initiative by Hamdan Bin Rashid Al Maktoum Foundation for Distinguished Academic Performance. Conclusions and implications were thus provided in this study to better serve the gifted education context in Morocco and provide recommendations for further research.

1. Introduction

The Moroccan social structure combines East and West. Due to its geographical location, Morocco has always been open to other cultures, while preserving its own. Between western thoughts stemming from the French colonization and eastern, Islamic and Arabic values of the region, an ethnic identity developed. Social trends of refute and acceptance of either, or both East and West mark a status quo in Morocco. Ethnic awareness and consciousness play a vital role among Moroccan communities.

Moroccans’ awareness towards education and giftedness has been addressed in this study. In this preliminary study, we gauge Moroccans’ perceptions of giftedness in view of the educational setting. The study has relied on a qualitative, open-ended survey and interviews to collate the pertinent views of the survey respondents to education. The survey questions were not in any way random, but rather construed in view of the given learning resources for this study in order to serve the research objectives. The survey questions contributed to six themes: 1. Defining giftedness and talent; 2. Types of talents; 3. Gifted individuals; 4. Giftedness and education; 5. Talent innateness and/or acquisition;6. Identification, awareness, and support of giftedness. The survey responses have revealed answers tallied herein.

Interestingly, the Moroccan educational landscape wavers between modernity and tradition. Since its independence, Moroccan schools have been “an efficient tool towards modernization” (Ennaji, Citation2005). The Ministry of National Education, Early Education, and Athletics urges conducting several initiatives. A variety of sports activities and competitions including handball, volleyball, soccer, track and field were included. Drawing, music and drama were also called upon by the ministry. Through the schooling system, the ministry continues to offer special sections for the distinguished students at the elementary, secondary and high school level. The ministry also ensures that distinguished and genius students participate in the International Olympiad. It is worth noting that recently, in October 2022, the Moroccan university student, Ziad Oumzil won first place in the Mathematics International Olympiad in Bulgaria. Moroccan schools have also established clubs such as the “Audiovisual Club” in Allal Al-Fassi High school in Sale. Moreover, Rabat’s Al Mokhtar Jazoulit School won the title of outstanding school among 92,000 Arab schools for the sixth edition of the Arab Reading Challenge. School clubs also offer Quran memorization and recitation for talented students. Noteworthy, too, The winner of the Google’s GDG Agadr event for Python programming in December 2018 was Iddir Mutea’, at age 11. The GDG event was open to university students; however, Iddir not only managed to attend but also to win the programming competition and hit the news.

The Moroccan society displays paramount attention to cultural heritage. The richness in culture calls upon varied language associations that should be noted. The cultural legacy relies on the use of standard Arabic, Moroccan Arabic and Berber for sociolinguistic functions. In the educational domain, it is worth noting that “Berber language, through its recognition as an official language and through its standardization” has been introduced in the school system (Ennaji, Citation2005). However, each of the languages used in Morocco only fulfills a certain social aspect. For instance, the domains of home and street utilize Moroccan Arabic and Berber, while standard Arabic, primarily used in education, and French may overlap in public administration, media, science and technology both in the public and private sectors (Ennaji, Citation2005). Education in Morocco allowed more individuals to be exposed to the Arabic-French interface.

In tackling the Moroccan educational status quo with regards to giftedness, it is worth referring to studies conducted on other Arab countries in this regard including the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Lebanon, Sudan & Oman.As this research unravels the perceived perceptions behind gifted education in Morocco, previous studies on the aforementioned Arab states have shown distinct results. For instance, the UAE considers the gifted and the talented as the assets of the future. It has recently introduced a general educational reform policy accentuating the needs for students with equal opportunities to achieve goals (Ismail, Alghawi, AlSuwaidi, & Ziegler, Citation2022). In general, the UAE is ahead of other Arab countries in developing gifted education and best practices (Ismail, Alghawi, AlSuwaidi, & Ziegler, Citation2022).In the KSA, gifted students are supported by the Ministry of Education and Mawhiba. The efforts of the KSA still require development in giftedness to better meet students’ needs, motivation and interests (Ismail, Alghawi, AlSuwaidi, & Ziegler, Citation2022). The case of Oman isn’t much different; efforts are made towards a national policy for both gifted education and identification of the gifted. Key results have been referred to in view of planning and investing in gifted education. Yet, like other countries, Oman still seeks to meet the growing needs for gifted education (Hemdan et al., Citation2022; Ismail, Alghawi, AlSuwaidi, & Ziegler, Citation2022). In the Sudanese context, positive outlooks are expressed by the society. There, however, seems to be a lack of evidence documented on gifted education in the Sudanese landscape (Ismail, Alghawi, AlSuwaidi, & Ziegler, Citation2022), just like the Moroccan context. In both Egypt and Lebanon, giftedness is recognized and valued. Gifted education is funded and catered for in Egypt by the government and private sector (Ayoub et al., Citation2022). More budget, though, should be allocated to better serve the gifted in the Egyptian setting. In Lebanon, on the other hand, no regulations are set on dealing or offering gifted education.

Such contrasts and comparisons set the stage for better communicating and emphasizing the educational status quo in view of giftedness in the Moroccan context, a context that has been underexplored. This study comes to offer preliminary indications in hopes to pave the way for further research.

2. Literature review

The literature reviewed for this study has been extant. From one perspective, giftedness and talents have been thoroughly incorporated in this study, while also considering any closely related and relevant studies in the Moroccan context in that respect. Our study also addresses the learning and educational resources. Moreover, relationships and thematic relationships have been drawn from the survey responses in the analysis of this study to focus on the learning and educational resources herein in consideration of gifted education in the Moroccan setting. The pertaining literature with regards to the following themes deduced from the survey questions informing the learning resources given is extensive too:

2.1. Defining giftedness and talent

The Marland’s report presents giftedness in the US, and may very much touch upon the initial interest in the given Moroccan educational context. This theme highlights Renzulli’s three- ring approach regarding creativity and task commitment exhibited in gifted behavior (1978). Gagne’s model is also considered under theme 1 as a “superior natural ability” (2009, 2012). Defining giftedness under theme 1 also entails including exceptionality and excellence (Ziegler & Baker, Citation2013; Ziegler et al., Citation2013).

2.2. Types of talents

This theme is titled as types of talents. In expressing the different types of talents, Gagne’s explanation of talent as subcategory of giftedness (2012). Gardner’s approach on multiple intelligences contributed to the theme’s better addressing of the talents.

2.3. Perceptions about gifted individuals

Intellectual ability is focused upon here. Terman’s views in the early 1920’s cover much of the human ability too. Giftedness has also been referred to as a unique human activity (Witty, Citation1958). From purposefulness, to drive and thus performance, the extant literature serves this theme well.

2.4. The relationship between giftedness and education

Previous research studies referred to include the systematic approach towards academic achievement (Tannenbaum, Citation1983). Theories that have been consulted herein include those of Renzulli (Citation1984) as well as Coleman and Cross (Citation2000), emphasizing on the individual as being identifiable. The study conducted by Liouaeddine et al. (Citation2017) also offered an explanation on outcomes resulting from individual and contextual aspects regarding determinants of academic excellence.

2.5. Is giftedness intrinsic or acquired?

Again, Galton’s work is referred to (1874). Terman’s works have been consulted too. Skills and aptitudes have been presented by Phenix (Citation1964) and later by De Haan (Citation1957). The innateness of giftedness has been discussed by Plomin (Citation1990), Gagné (Citation1993)and Sternberg (Citation1990, Citation1993). However, both Ziegler and Heller (Citation2000) relate that behaviors contribute to talent acquisition.

2.6. Current ways of identifying and supporting giftedness

Significantly, Ziegler’s actiotope approach relates how biological, social and individual adaptations play a role in giftedness (Ziegler et al., Citation2013). According to Ziegler and Heller (Citation2000) a gifted individual will demonstrate high achievement provided that there are no environmental restrictions. Practice and instructional activities as related by Vialle et al. (Citation2021) touch upon key topics in this arena.

It is worth mentioning that there is a plethora of literature on giftedness. Understanding intelligence and giftedness has been explained by Barab and Plucker (Citation2002) as general factors and as related approaches by Spearman 1904, Jensen Citation1998, as well as differentiated models by Thurstone, Citation1938, Guilford, Citation1967; Feldhusen, Citation1998 (as cited in Sternberg & Davidson, Citation2005). Looking at varied approaches, Renzulli’s (Citation1978) three-ring stands out in considering the interaction between above-average ability, creativity and task commitment. Tannenbaum (Citation1983) adopted a systematic approach in outstanding achievement. Gardner (Citation1983) presented the multiple intelligences theory. Sternberg’s (Citation1985, Citation1986) incorporated environmental interactions with regards to giftedness. Also, Sternberg& Davidson (Citation1986) addressed the qualities of giftedness, while Ceci and Nightingale (Citation1990) tackled a bioecological approach towards giftedness along with the role of context. The PASS theory should be noted too (Das et al., Citation1994). All of Colangelo and Davis (Citation2003); Heller et al. (Citation2000) contributed uniquely to the field of giftedness. Gagne also provided a distinction between giftedness and talent (Gagné, Citation2012).

By addressing the different perspectives of giftedness and talent in the literature provided herein, several points have been stressed. Expressions of giftedness also include famous works on human activity pertaining to giftedness (Witty, Citation1958); human characteristics on giftedness (Wallace, Citation1987); learning from performance and experience (Terman & Chase, Citation1920). Prior research tackled the types of talents (Gagné, Citation2012; Gardner, Citation2013). Moreover, exceptionality as well as developing excellence have been uniquely addressed in the extant literature (Ziegler & Baker, Citation2013; Ziegler et al., Citation2013). Additionally, Barab and Plucker (Citation2002) further emphasized that the classroom is merely an avenue where students may somehow prove their talents.

In view of the Moroccan context, prior research has touched upon the cultural richness, multiculturalism and multilingualism (Ennaji, Citation2005). A committee dedicated to reform the educational system in Morocco was formed, and in 1999, King Mohammed VI announced the National Charter for Education and Training. Tradition and modernity have also widened the gap in the educational context (Ennaji, Citation2005). Noteworthy, too, a study on metrological characteristics through a questionnaire which composed 140 items used to test Moroccan students of high school confirmed that the questionnaire was initially intended for Bahraini students (Raissouni et al., Citation2013). Research has also revealed that Moroccan students’ outcomes rely on individualistic and contextual aspects (Liouaeddine et al., Citation2017). Critical thinking skills in the Moroccan educational context have been explored in view of intellectual traits (ethical behavior, autonomy, fair-mindedness, courage, perseverance) universal intellectual standards (accuracy, clarity, relevance, logical sufficiency, depth) and reasoning(purpose, inquiry, information, analysis, inference, interpretation, implications and assumptions) (Maan, Citation2012).

Indeed, our study uniquely tackles gifted education in Morocco and its status quo. This research addresses the survey questions’ responses to draw thematic patterns labelled as themes in this study to highlight key issues relevant so as to inform the learning resources.

3. Learning resources explorations: Theory and practice

The purpose of this study is to explore the status of gifted education in Morocco from a learning resource perspective. Theoretically, learning and educational resources resemble a bridge to learning goals. As in any educational setting, educational and learning resources are prime (Ziegler, Citation2005). These two components have become essentially important in the Arab countries (Ismail, Alghawi, & AlSuwaidi, Citation2022).

For this current study, the learning resources shed light on key aspects. Moroccan students’ goals, motivation, aptitude, attentional level and achievement have been enlisted herein as educational resources. They have also been referred to as results according to Ismail, Alghawi, and AlSuwaidi (Citation2022), that comprise Actional, Organismic, Telic, Episodical, and Attentional aspects. Moroccan students’ participation in international exams like Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) as well as Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS) have been noted. It is worth noting that the TIMSS and PIRLS reports of 2011 showed that more than 25%of Moroccan students had low academic achievements and that the achievement in Morocco was unreliable to be measured (Liouaeddine et al., Citation2017).

Notably, too, the first STEM school(named STM) has opened just recently in Morocco, located in Fez, in March 2022. According to the STM school’s website, it incorporates Moroccan education with an international educational approach from pre school to high school. The new institution called the STM school adopts a tri-linguistic (Arabic, French, English) approach, with English being the main language at use. The school also promises to offer a wide variety of extracurricular activities to nurture students’ abilities, interests and talents. The STM school also envisions becoming Morocco’s leading tri-linguistic school while delivering innovation and excellence. No further details are provided on the school’s website.

In order to achieve a learning goal, both learning and educational resources and/or capitals are needed. It is worth noting that resources or capitals are means that can be used towards achieving specific objectives (Chandler & Ziegler, Citation2017; Ziegler & Baker, Citation2013). The learning and educational capital approach was presented by Ziegler and Baker (Citation2013)(as cited in Ismail, Alghawi, AlSuwaidi, & Ziegler, Citation2022) who communicate the educational status quo explored in the Arab countries including United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Lebanon, Sudan & Oman.

Learning resources have been classified as (endogenous) pertaining to matters “within” the individual, and educational resources as (exogenous) which are external to the individual but within the environment (Ziegler, Citation2005; Ziegler & Baker, Citation2013). In order for learning to take place, these two components (endogenous and exogenous) are expected to be present. Understanding these two resources enhance understanding gifted education. Educational capitals or resources include 1. Economic Educational Capital, 2. Cultural Educational Capital, 3. Social Educational Capital, 4. Infrastructural Educational Capital, 5. Didactic Educational Capital. Learning capitals or resources, on the other hand, comprise Actional Learning Capital, 2. Organismic Learning Capital, 3. Telic Learning Capital, 4. Episodical Learning Capital, 5. Attentional Learning Capital.

In theory, the significance of tackling these resources separately contributes towards conceptualizing a perception as a whole. In practice, however, these resources have been viewed in consideration of the study survey responses. Individualistic responses indicate how and why resources are practical in one sense and theoretical in another. In order to do so, the method is explained below.

4. Method

This study explored the existing situation of gifted education in Morocco from the perspective of learning resources. The choice of the implemented methodology was mainly informed by the purpose of the study. Thus, this study follows the qualitative approach. This approach has been selected for the following reasons: 1.The research idea is underexplored in the Moroccan educational context.2. The extant literature for the Moroccan setting doesn’t provide similar or parallel concepts as collated from the extracted survey themes below. This approach is used to make connections and deduce results as well as to synthesize an understanding of the given study.

The current study collected qualitative data through open-ended survey questions via interviews and emails. The survey questions were prepared in English and translated into Arabic to meet respondents’ needs. The study targeted 40 participants in Morocco. The study began with 8 personal interviews. The researchers interviewed Moroccan professors and educational professionals to collate survey responses. The remaining 32 participants received the survey via email. However, only 15 participants responded to the survey, so a total of 23 responses were tallied. This study’s survey targeted university faculty, educational staff, school teachers and principals as well as students from different backgrounds. The survey questions were not random, but contributed to the objective of the study by informing the given learning resources. The questions were carefully tailored to deliver to the learning resources tackled in this research. The survey comprised 8 questions. The questions addressed personal definitions of giftedness and talent, the types of talents, and individual perceptions about gifted persons. Other questions were posed on whether talent is intrinsic or acquired; whether there is a relationship between giftedness and education, whether the Moroccan communities distinguish, identify and support gifted individuals. Respondents were also requested to share their opinions on how to raise awareness in their communities regarding giftedness and point out how their communities should nurture and support the gifted.

The insights provided by the qualitative data shared in the given responses have become a motivation to conduct further exploration towards a better understanding of giftedness and gifted education within the Moroccan context in view of the learning and educational resources. The narrative comments have aided in alluding to the given findings below. Interestingly, the survey results have contributed to other relevant topics of interest.

5. Results and discussion

This study’s survey was originally prepared in English and Arabic for the respondents’ convenience by the research author. Arabic responses were then translated into English by the research author for the purposes of this study. The survey was set off by 8 personal interviews. However, for the convenience of the remaining respondents, the survey questionnaire was then sent as Google form via email. The Google form indicated the demographic information of the total 23 respondents as follows: 60.9%, 14 out of 23 respondents, were female, and 39.1%,the remaining 9 respondents were male. The respondents’ ages varied from 20 years to over 50 years, while their educational backgrounds varying from a bachelor’s degree(18.2%), a master’s degree(36.4%), higher diploma (27.3%), and a PhD(18.2%). Moroccan respondents were students, teachers, principals, college instructors and professors at different institutions.

This research adopted thematic coding for its qualitative data derived from the interviews and Google form responses. Data was analyzed in an inductive manner, guided by the research questions and sensitizing concepts. Analysis included constant comparison of codes, identification of emergent themes, memo-writing about category and theme development. Many researchers (Chametzky, Citation2013; Glaser, Citation1978, Citation1992, Citation1998; Glaser & Strauss, Citation1967; Stern & Porr, Citation2011) have greatly discussed memos and memo-writing. Memo writing in this study served the purpose and the open-coding process began by independently reading the data to become familiar with it; first, through an unstructured reading of the narrative data before a second reading, where the researcher wrote open codes. This process allowed for emerging phenomena to arise from the raw data and was guided by Glaser and Strauss (Citation1967) constant comparative approach. According to Glaser (Citation1978), “Comparing the apparently non-comparable increases the broad range of groups and ideas available to the emerging theory”.During the comparative process, the researcher had access to the narrative data and the survey questions. The questions and narratives drew the researcher’s attention to contextual issues, important findings, and background ideas which informed the data analysis. These materials served as sensitizing concepts, offering the study a sense of direction while making sense of the data (Patton, Citation2015). Through the broad categories, codes were identified and defined for the survey responses. Next, the researcher refined the categories while paying close attention to recurring points (Stern & Porr, Citation2011) and “related categories” (Glaser, Citation1998: p. 138). To systematically analyze the data for this publication, a further round of focused and selective coding (Bogdan & Biklen, Citation2007; Charmaz, Citation2006) was conducted. As data analysis continued, notes and tables were generated to organize, synthesize, differentiate, and compare patterns in the data. Codes developed the themes selected herein, and where appropriate, themes were compared code by code in order to offer clarifications. In summary, the coding of the data into generated themes took place in two stages: an initial exploratory one and a more advanced one. Further interpretation was conducted by the researcher. The thematic coding structure depended on the data found. Deduced themes communicated the findings as per the given learning and educational resources for this study as demonstrated below in Table .

Table 1. Educational and learning capitals in view of the survey themes deduced from the survey responses for the Moroccan educational setting

5.1. Survey Themes

Survey questions were particularly and carefully structured to inform the given learning resources of the study. Responses to the survey questions have indicated recurrent patterns that have been categorized as themes in this study. Themes 1–6 (as seen in Table ) have been meticulously and thoroughly deduced from the survey responses. These themes have uniquely touched upon the given resources as illustrated in Table . The survey respondents’ answers inform some resources more than others. The most recurrent theme is theme 3, followed by theme 2 and theme 4. The least recurrent theme is theme 6(identification, awareness and support of the gifted). Thus, the table demonstrates the relationship between the given resources and the study themes deduced from the survey responses. All the study themes from 1–6 are explained below.

5.2. Theme One: Defining giftedness and talent

Giftedness and talent have been examined and reexamined time and again throughout history thereby embodying a plethora of research claims. Among the prominent definitions in the extant literature and one that many school systems allude to is the one that was provided by the US office of Education and presented in the Marland (Citation1972) Report stated as follows:

Gifted and talented children are those identified by professionally qualified persons, who, by virtue of outstanding abilities, are capable of high performance. These are children who require differentiated educational programs and/or services beyond those normally provided by the regular school program in order to realize their contribution to self and society”)p. IX). (as cited in Passow, Citation1981)

In this context, the Marland report is a 1972 report to the Congress of the United States by S. P. Marland, offers definition of giftedness of children. Notably, it is the first national report on gifted education. The Marland’s report highlights the spark of giftedness in the US, and may very much relate to the initial interest in the given Moroccan educational setting.

Theoretical research models have uniquely treated giftedness. Such models include Renzulli ‘s and Gagne’s works. Renzulli’s three- ring approach stresses that students who possess above average ability, creativity and task commitment exhibit gifted behavior (1978). Gagne’s model, on the other hand, considers giftedness as a “superior natural ability” and talent a skill that has been developed extremely well (2009). Gagne also offers components including gifts, talents, and two types of intra-personal as well as environmental catalysts (2012). It is also worth mentioning that Gagné (Citation2012) stresses that there is a distinction between giftedness and talent; whereby he clarifies that giftedness indicates the possession and application of distinguished natural skills or aptitudes, in at least one specific skill area, in a way that places the individual among the top of his/her peers. In contrast, talent, according to Gagne, marks the control of skills that are developed called competencies, as in practical knowledges and skills, whereby the individual stands out among his peers in at least one specialty of academic, technical, artistic or sport activities.

Along these lines, our study survey respondents were asked to define giftedness and talent in Arabic. Responses, which have been translated into English for the purpose of our study, were different; however, recurrent terms used by respondents were “distinction” and “excellence” when both addressing a gifted and/or talented person. Significantly, these responses parallel previous studies asserting the role of exceptionality and excellence in giftedness (Ziegler & Baker, Citation2013; Ziegler et al., Citation2013).

Our respondents mainly view a gifted individual as someone who is highly intelligent, holds a special trait, reflects skills and potential setting him/her apart from the rest, stands out among the crowd in several aspects with one very particular distinctive aspect. These responses were interchangeably used for both gifted and talented individuals. Other responses plainly called giftedness intelligence. It is also worth mentioning a particular response stating that “giftedness and talent can be a reason for someone’s fame in his/her community or even internationally.”

5.3. Theme two: The Types of Talents

The current study’s survey also tackled the types of talents. Respondents’ answers reflected variable views. In general, most respondents focused on talents related to school subjects such as math and science. This correlates with previous research findings related to the Moroccan context explaining that scientific subjects are mainly taught in Arabic in elementary school, while higher education is taught in French(the second spoken language) and that lower achievement in mathematics and chemistry was scored by students speaking Arabic at home(Liouaeddine, Citation2017).Responses also specified linguistic talents, vocal talents, sports talents. Other reiterated responses included drama, art and drawing, singing as well as dancing. Mentions in responses also described types of talent as intellectual, cultural, creative and innovative talents. An interesting response also expressed political talents as another type of talent, while another respondent claimed that talents are simply unlimited.

Talent has been varyingly discussed in the extant literature. According to Gagné (Citation2012) talent, “occasionally” is treated like a sub category of giftedness. Modern talent theories favor domain-specific conceptions as resembled by, for instance, Gardner’s multiple intelligence model, as indicated via verbal- linguistic intelligence; logical -mathematical intelligence; spatial- visual intelligence; bodily-kinesthetic intelligence; musical intelligence; interpersonal intelligence; intrapersonal intelligence; naturalist and existential intelligence (Gardner, Citation2013). Addressing these intelligences definitely enriches the students’ learning process and offers a comprehensive, pluralized approach towards learning and teaching.

Noteworthy, too, in discussing talent, its development needs to be addressed too. Talent development, very often, regards groups of people reflecting significant performance(Gershon et al., 1996; Roecker et al., 1998).

To better enlist our respondents’ answers, the following have been indicated to better display artcistic skills, academic achievemnt and other skills.

5.4. Theme three: Perceptions about gifted individuals

This question received much interest from the respondents. Answers varied from abstract traits and/or characteristics a gifted person may possess to specific names of persons. Among the names of gifted individuals stated is that of Rachid Yazami, a Moroccan scientist, engineer, and inventor. He is best known for his critical role in the development of the graphite anode (negative pole) for lithium-ion batteries and his research on fluoride ion batteries (Wikipedia.com). Other interesting names included Sheikh Al Sha’arawi for his simple interpretations of the Quran verses; Ibn Taymiyyah for his publications. Ibn Taymiyyah is a “polarizing figure in his own times and in the centuries that followed, Ibn Taymiyyah has emerged as one of the most influential medieval writers in contemporary Sunni Islam”(Wikipedia.com). Furthermore, respondents personified giftedness through examples they shared on their siblings who had one become a pianist and another an artist without taking any classes to learn musical notes nor drawing.

In abstract form, what respondents communicated with regards to a gifted individual has been displayed in a Venn diagram () to better illustrate the notions and their relationship.

Accordingly, a gifted person has been the focus of many studies. Notably, since 1874, Galton researched superior intellectual ability be referring to characteristics that included” tremendous energy, good health, independence, purposefulness, dedication, vivid imagination, fluent mental association and a drive powerful enough to overcome internal or external constraints” (as cited in Wallace, Citation1987). A unique expression defines giftedness as “performance in a potentially valuable line of human activity (Witty, Citation1958). Moreover, Terman, in the early 1920's, expressed that a gifted person is “someone with an extraordinary ability to exercise sensitive judgement in solving problems in adapting to new situations, learning from performance and experience (Terman & Chase, Citation1920). Indeed, much of the survey respondents’ answers are in line with much of the above definitions. Furthermore, Gardner questions if students can achieve excellence in anything, if they lack a sense of purpose or direction. He, therefore, argues for a more abstract denotation towards talent in the sense that it can be serviced for truth or justice or beauty, all intertwined with the concept of responsibility (1961,1984).

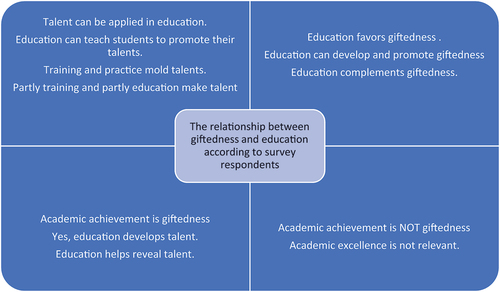

5.5. Theme 4: The relationship between giftedness and education

In addressing the learning resources given in this study, a relationship between giftedness and education has been questioned. The study posed this question to respondents in order to collate their relative responses in drawing conclusions. Respondents clearly reflected neat responses with a solid “no” answer to multiple assertive responses. It is worth noting, though, the respondents clearly used “giftedness” and “talent” interchangeably in this given question. Like all the responses drawn, they have been translated from Arabic to English. The responses and their relationship are better resembled in the matrix below () as clarified by the researchers:

Diagram 5. Demonstrates the relationship between giftedness and education according to respondents’ survey answers as clarified by the researchers.

Since society may consider outstanding academic achievement part of giftedness and vice versa, it is worth mentioning that Tannenbaum (Citation1983) who followed a systematic approach for outstanding achievement highlighted 1. General ability, 2. Special ability 3.non-intellective factors 4. Environmental factors 5. Chance factors. Barab and Plucker (Citation2002), on the other hand, stress that the classroom is rather the domain in which society relies on in hopes to figure out, understand and identify talent, and they recommend that educators construct social contexts in which students and demonstrate their gifted behavior (as cited in Sternberg & Davidson, Citation2005)

The relationship between education and giftedness shed light on several theories. Such statements accentuate theories of Renzulli (Citation1988) as well as Coleman and Cross (Citation2000), which focus on the individual as being identifiable as gifted rather than emphasizing environments where gifted individuals thrive. Interestingly, too, Walberg and Paik communicate that giftedness should be productive so as to “include will power, perseverance through difficulties, sufficient independence to originate and sustain new ideas despite others’ objections, and deep knowledge and mastery of a specialized field” (as cited in Sternberg & Davidson, Citation2005). Certainly, the knowledge and mastery of a field are very much related to education and educational attainment. Moreover, as per the Moroccan context, the students’ outcomes are influenced by individual and contextual aspects reflecting determinants of academic excellence touching on gender, family environment and peer effect (Liouaeddine et al., Citation2017).

5.6. Theme 5: Intrinsic versus acquired

As early as 1874, Galton defined superior intellectual “ability” entailing tremendous energy, good health, independence, purposefulness, dedication, vivid imagination, fluent mental associations as well as powerful drive to overcome any internal or external constraints. Later in the 1920’s, Terman also referred to giftedness as an “ability” displaying sensitive judgment to solving problems, adapting to new situations, as well as learning from performance and experience. He also claimed that a gifted person has high levels of general intelligence (as cited in Wallace, Citation1978). Significantly, innate gift variables (intellectual, creative, socio-affective, and sensory-motor aptitudes) have been discussed by Gagné (Citation1993) and Sternberg (Citation1990, Citation1993). Thus, giftedness, according to Plomin (Citation1990) can be viewed as innate, intrinsic and genetically determined. Gifts are psychologically ascertained entities manifested in “one single trait, or a perceptual ability, or an entire set of traits”, according to Ziegler and Heller (Citation2000).

Research has also pointed out other the acquisition of talents. Researchers have stated that behaviors lead to achievement towards acquisition of talent (Ziegler & Heller, Citation2000). Previous studies by Tannenbaum have also viewed talents via achievement and potential for achievement (as cited in Ziegler & Heller, Citation2000). Skills and aptitudes have been presented by Phenix (Citation1964) and later by De Haan (Citation1957) who both emphasized the notion of excellence. As “pursuit of excellence” made way in the US, a true revival towards gifted and talented issues was witnessed (Tannenbaum, Citation2000).

Most of the survey responses show a consensus on giftedness being intrinsic or acquired. Respondents majorly consider giftedness to be innate and intrinsic. Not a single response solely indicated the acquisition of talent. Responses stating acquisition of talent incorporated both the intrinsic and acquired aspects of talent. “Both” intrinsic and acquired was a common answer among respondents explaining that individuals are born with certain gifts that need to be developed. In fact, talent development was a huge factor in the survey responses. A typical answer indicated that giftedness is intrinsic but must be developed by practice, training, education, etc. Notes were also made on how family, school and society help mold and develop talents. An interesting response is referred to whereby the respondent clarified that “a gift is innate” while “a talent is acquired”.

5.7. Theme 6: Current ways of identifying and supporting giftedness

The role of family, school and peers cannot be denied in anyone’s development. Other dominant factors affecting human development include cultural beliefs, political and economic situations, etc … As such gifted youth, throughout their development, are indeed impacted by all these aspects. It is of much importance to refer to Ziegler’s actiotope approach to better relate how biological (carried by the human species), social (carried by social associations) and individual adaptations (carried by individuals) play a role in giftedness (Ziegler et al., Citation2013). Our study has addressed separate questions on each of the identification of the gifted in Morocco, the awareness towards giftedness, as well as supporting giftedness. Deliberate practice and instructional activities as expressed by Vialle et al. (Citation2021) resonate in this regard. However, from the drawn thematic relationships from the given responses, the answers to these three questions have been combined under one main theme titled theme 6 to better meet the needs of this study.

According to Ziegler and Heller (Citation2000) if someone is gifted, he/she will demonstrate high achievement as long as he/she isn’t restricted by environmental factors. Interestingly, too, Walberg and Paik communicate that giftedness should be productive so as to “include will power, perseverance through difficulties, sufficient independence to originate and sustain new ideas despite others’ objections, and deep knowledge and mastery of a specialized field” (as cited in Sternberg & Davidson, Citation2005)

Survey respondents relate that society acknowledges the gifted, while others claim that different societies value giftedness distinctly. A respondent clearly stated that Morocco recognizes talents in the following order: sports, arts and crafts, intellectual activities. This statement is noteworthy particularly that we have just witnessed a huge leap in the history of Moroccan sports as the Moroccan National Soccer team has just recently played in the semifinals for the FIFA World Cup. Therefore, this statement holds to be true among other respondents’ opinions who stressed that the activity of sports has gained most attention among other talents in the Moroccan landscape.

It’s worth noting too that some respondents see there is no societal awareness when it comes to gifted education. More than one respondent agree that Western countries show more interest in gifted individuals when compared with the Moroccan context. Respondents also agree on raising awareness by establishing institutions that foster giftedness. Also encouraging parents, families and schools to seek awareness and help spread the culture of giftedness. Conducting workshops, seminars and training sessions have also been suggested by respondents.

In all, thematic coding of the survey responses have contributed to the 6 main themes listed above: 1. Defining giftedness and talent 2. Types of talents 3. Perceptions about gifted individuals 4. The relationship between giftedness and education 5. Intrinsic versus acquired 6. Current ways of identifying and supporting giftedness. Addressing these themes have served to draw upon the learning resources as required to be highlighted herein within the Moroccan educational landscape.

Thus, the above derived themes of this study inform the learning resources given as earlier displayed in Table .

6. Recommendations

The Moroccan current educational setting calls upon further encouragement and guidance for the gifted and talented students. Higher awareness levels towards gifted education is strongly urged. When compared with other Arab nations, more is needed in the Moroccan educational arena in terms of providing and nurturing giftedness.

Future studies can tackle rural and urban Moroccan areas distinctly. Also, more studies

can be conducted on Morocco’s gifted education status to better address the educational capital by increasing the number of initiatives towards giftedness, enrichment programs, and the number of students participating in gifted education programs. Upcoming studies can include non-Moroccan views on the educational status in Morocco. Future studies can offer a comparison between the public and private educational opportunities with regards to giftedness in Morocco. Further questions can incorporate mentees and mentors in the Moroccan context. The role of parents’ level of education can be better focused on to better understand gifted students’ home environments in Morocco. Health and fitness in the Moroccan schools may be addressed in view of giftedness in the educational system. There is an urging need to conduct further studies on giftedness in the Moroccan landscape. From the given themes above, it is highly recommended to conduct research to clarify the contrast between the talented and the gifted, as both terms were used interchangeably among the research respondents in the Moroccan context.There is an indicated scarcity on issues pertaining to the gifted in the Moroccan educational setting. There is also scarcity in documented evidence from educational authorities.

7. Conclusion

This study explored the educational status quo with regards to gifted education in Morocco. In brief, the current study is the first of its kind for the Moroccan context since it relied on a learning resource theoretical model to tackle the existing situation of gifted and talented education in the Moroccan setting in view of the study survey responses. This purposeful study may enlighten authorities and policymakers in reviewing the status quo of gifted education from different perspectives. When evaluating gifted education and the pertinent outcomes, it is necessary to realize the role of both internal and external factors that respectively affect the individual such as motivation, goals, experience, attention, and environmental factors such as the surrounding “society” of teachers, parents, caregivers, materials, instructional and infrastructural needs,etc.

Certainly, the current status quo of the Moroccan educational setting calls upon further awareness, knowledge, and appreciation of gifted education. Giftedness is in itself a culture of its own; and like any culture, it should be represented, respected, valued, and appreciated.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Luma Alsalah

Luma Alsalah is an English language instructor at the College of Graduate Studies at Arabian Gulf University, Bahrain. She earned her MA in English from Wichita State University. She has taught several writing courses at different universities in the USA. She taught writing and piloted research skills courses at the US Navy Base in Bahrain. She also conducted courses for the Navy in Kuwait and Qatar. Luma is also the editor of the College of Graduate Studies Newsletter at Arabian Gulf University which is a social platform targeting unique themes in every issue while interviewing prominent figures in society. She also conducts regional workshops on scientific writing, research skills and public speaking. She has participated in several conferences. Her research interests are multidisciplinary focusing on language and the mind, language acquisition, language and intelligence, language and creativity, language and wisdom, sociolinguistics, linguistic uses across varied fields.

Nadia Tazi

Nadia Tazi, Professor of cognitive social psychology, and learning disabilities at Mohammad V University, Morocco, and Prof in learning disabilities at Arabian Gulf University in Bahrain. She was the head of the Learning Disabilities Department during 2013/2015. Currently, she is the coordinator of the learning disabilities program and autism program, supervising master’s degree and PhD theses. She is also the external examiner in many universities in Morocco, Bahrain and abroad. She has participated in several conferences in Morocco, Canada, Kuwait, Jordan, Thailand, Malaysia, etc … Prof Nadia has also published research in psychology and special education in Arabic, French, English; participated in psychological and social research projects with the Ministry of education in Morocco, and presented various workshops in special education and psychology. Current Research Interests: The contribution of psychology and educational science in addressing current educational issues; Cognitive Behavioral approach; Gifted Students with Learning Disabilities; Youth Issues. Prof Nadia is also involved in the cooperation between researchers and academics around the globe through the research team at AGU.

References

- Ayoub, A. E. A., Abdulla Alabbasi, A. M., & Morsy, A. (2022). Gifted education in Egypt: Analyses from a learning-resource perspective. Cogent Education, 9(1), 2082118. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2022.2082118

- Barab, S. A., & Plucker, J. (2002). Smart people or smart contexts? Talent development in an age of situated approaches to learning and thinking. Educational Psychologist, 37(3), 165–15. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15326985EP3703_3

- Bogdan, R. C., & Biklen, S. K. (2007). Qualitative research for education: An introduction to theory and methods. (5th ed.). Allyn & Bacon.

- Ceci, S. J., & Nightingale, N. N. (1990). The entanglement of knowledge and process in development: Toward a tentative framework for understanding individual differences in intellectual development. In Interactions among aptitudes, strategies, and knowledge in cognitive performance (pp. 29–46). Springer New York. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4612-3268-1_4

- Chametzky, B. (2013). Generalizability and offsetting the affective filter. Grounded Theory Review, 12. http://groundedtheoryreview.com

- Chandler, K. L., & Ziegler, A. (2017). Learning resources in gifted education. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 40(4), 307–309. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162353217735148

- Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. Sage Publications.

- Colangelo, N., & Davis, G. A. (2003). Handbook of gifted education (3rd ed.). Allyn & Bacon.

- Coleman, L. J., & Cross, T. L. (2000). Social-emotional development and the personal experience of giftedness. International Handbook of Giftedness and Talent, 2, 203–212.

- Das, J. P., Naglieri, J. A., & Kirby, J. R. (1994). Assessment of cognitive processes: The PASS theory of intelligence. Allyn & Bacon.

- Davidson, J. E., & Sternberg, R. J. (1986). Smart problem solving.Metacognition in educational theory and practice.

- De Haan, R. F. (1957). Identifying gifted children. The School Review, 65(1), 41–48. https://doi.org/10.1086/442374

- Dihi, M., & Bouamri, A. (2018). The effects of a creativity training program on students’ initial perceptions of creativity: The case study of Mohamed First University, Morocco. Arab World English Journal, 9(2), 364–378. https://doi.org/10.24093/awej/vol9no2.24

- Elbouhssini, A. (2022). Self-esteem and creativity in moroccan primary education: A comparative study between state-run and private school students of EL-Kelaa Des Sraghna as a case study. Journal of Social Sciences Advancement, 3(2), 73–80. https://doi.org/10.52223/JSSA22-030203-34

- Ennaji, M. (2005). Multilingualism, cultural identity, and education in Morocco. Springer Science & Business Media.

- Feldhusen, J. F. (1998). A conception of talent and talent development.

- Gagné, F. (1993). Constructs and models pertaining to exceptional human abilities.

- Gagné, F. (2012). From gifted inputs to talented outputs. Fundamentals of Gifted Education: Considering Multiple Perspectives, 56.

- Gardner, H. (1983). Multiple intelligences (2nd ed.). Basic Books.

- Gardner, H. (2013). Frequently asked questions—Multiple intelligences and related educational topics. https://howardgardner01.files.wordpress.com/2012/06/faq_march2013.pdf

- Glaser, B. (1978). Theoretical sensitivity. Sociology Press.

- Glaser, B. (1992). Basics of grounded theory analysis. Sociology Press.

- Glaser, B. (1998). Doing grounded theory: Issues and discussions. Sociology Press.

- Glaser, B., & Strauss, A. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Sociology Press.

- Guilford, J. P. (1987). Creativity:Yesterday, today and tomorrow. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 1(1).

- Heller, K. A., Mönks, F. J., Subotnik, R., & Sternberg, R. J. (Eds.). (2000). International handbook of giftedness and talent.

- Hemdan, A. H., Ambusaidi, A., & Al-Kharusi, T. (2022). Gifted education in oman: Analyses from a learning-resource perspective. Cogent Education, 9(1), 2064410. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2022.2064410

- Ismail, S. A., Alghawi, M. A., & AlSuwaidi, K. A. (2022). Gifted education in United Arab Emirates: Analyses from a learning-resource perspective. Cogent Education, 9(1), 2034247. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2022.2034247

- Ismail, S. A., Alghawi, M. A., AlSuwaidi, K. A., & Ziegler, A. (2022). Gifted education in Arab countries: Analyses from a learning-resource perspective. Cogent Education, 9(1), 2115620. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2022.2115620

- Jense, A. R. (1998). The g factor and the design of edcuation. Intelligence, Instruction, and Assessment. Theory Into ractice, 111–131.

- Liouaeddine, M., Bijou, M., & Naji, F. (2017). The main determinants of Moroccan students. Outcomes, 5(4), 367–383. https://doi.org/10.12691/education-5-4-5

- Maan, N. A. (2012). Critical thinking and the Moroccan educational context. Almadrssa Al-Maghribiya 4, 5, 26–48.

- Marland, S. (1972). Education of the gifted and talented: Report to the congress of the United States by the U.S. Commissioner of Education. U. S. Government Printing Office.

- Passow, A. H. (1981). The nature of giftedness and talent. Gifted Child Quarterly, 2

- Patton, M. Q. (2015). Qualitative research and evaluation methods (4th ed.). Sage.

- Phenix, P. H. (1964). Man and his becoming. Rutgers University Press.

- Plomin, R. (1990). Nature and nurture: An introduction to human behavioral genetics. Thomson Brooks/Cole Publishing Co.

- Raissouni, A., Benelazmia, A., & Raissouni, N. (2013). Critical review of a quationnaire of diagnostic of gifted children abilities in the light of DMGT 2.0(Case of Moroccan students). International Journal of Advanced Research in Education, 1(1), 08–16.

- Renzulli, J. S. (1978). What makes giftedness? Reexamining a definition. Phi Delta Kappan, 60(3), 5–10. https://doi.org/10.1177/001698628102500102

- Renzulli, J. S. (1984). The triad/revolving door system: A research-based approach to identification and programming for the gifted and talented. Gifted Child Quarterly, 28(4), 163–171. https://doi.org/10.1177/001698628402800405

- Renzulli, J. S. (1988). A decade of dialogue on the three ring conception of giftedness. Roeper review, 11(1), 18–25.

- Sternberg, R. J. (1985). Beyond IQ : A Triarchic theory of human intelligence. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-009-4406-0_9

- Sternberg, R. J. (1990). Metaphors of mind: Conceptions of the nature of intelligence. Cambridge University Press.

- Sternberg, R. J. (1993). Sternberg triarchic abilities test. European Journal of Psychological Assessment.

- Sternberg, R. J., & Davidson, J. E. (Eds.). (2005). Conceptions of giftedness (Vol. 2). Cambridge University Press.

- Stern, P., & Porr, C. (2011). Essentials of accessible grounded theory. Left Coast Press.

- Tannenbaum, A. J. (1983). Gifted children: Psychological and educational perspectives. Macmillan Publishing Company.

- Tannenbaum, A. J. (2000). A history of giftedness in school and society. International Handbook of Giftedness and Talent, 2, 23–53.

- Terman, L. M., & Chase, J. M. (1920). The psychology, biology and pedagogy of genius. Psychological Bulletin, 17(12), 397. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0073715

- Thurstone, L. L. (1938). Primary mental abilities.Psychometric monographs.

- Vialle, W., Stoeger, H., & Ziegler, A. (2021). Editorial: Advanced learning. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 712661. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.712661

- Wallace, B. (1987). An exploration of some definitions of giftedness. Gifted Education International, 4(3), 136–138. https://doi.org/10.1177/026142948700400302

- Wallace, C. S. (1987). Experience and brain development. Child Developmet.

- Witty, P. (1958). Who are the gifted?

- Ziegler, A. (2005). The actiotope model of giftedness. In R. Sternberg & J. E. Davidson (Eds.), Conceptions of giftedness (pp. 411–434). Cambridge University Press.

- Ziegler, A., & Baker, J. (2013). Talent development as adaptation: The role of educational and learning capital: Albert Ziegler and Joseph Baker. In Exceptionality in East Asia (pp. 33–54). Routledge.

- Ziegler, A., & Heller, K. A. (2000). Conceptions of giftedness from a meta-theoretical perspective. International Handbook of Giftedness and Talent, 2, 3–21.

- Ziegler, A., & Stoeger, H. (2017). Systemic gifted education: A theoretical introduction. Gifted Child Quarterly, 61(3), 183–193. https://doi.org/10.1177/0016986217705713

- Ziegler, A., Vialle, W., & Wimmer, B. (2013). The actiotope model of giftedness. Exceptionality in East Asia Explorations in the Actiotope Model of Giftedness, 1–17.