Abstract

The presence of bullying and cyberbullying in Pakistani primary, secondary, and tertiary institutions has been widely studied. The detrimental effects of these forms of aggression on students’ physical, mental, and emotional well-being have been extensively documented. However, there is little literature describing how teachers in their professional institutions have addressed bullying using common approaches. In a cross-sectional survey, we collected data from 454 teachers working in various educational institutions in Pakistan. One-way ANOVAs indicate that severe punitive measures are still the most commonly used strategy by teachers in Pakistan to deal with bullying. We also found that primary school teachers are more likely to involve parents in solving the problems compared to higher educational institutions. Moreover, teachers from rural backgrounds were less likely to punish students and less likely to intervene in bullying incidents. The reasons for these behaviors are discussed in the discussion section. It is recommended that educators be trained to be able to address these issues with other effective strategies, such as empowering victims and counseling bullies more frequently.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

While the prevalence of bullying in Pakistan has been extensively researched and highlighted in numerous evidence-based research studies, there remains a need for further investigation into the common strategies used by teachers to address this issue. This research sheds light on the fact that punishment or sanctions continue to be the most common approach, particularly in educational institutions located in urban areas. Conversely, educators in rural areas are more likely to ignore or avoid incidents of bullying. The study suggests that teacher training should focus on implementing more effective strategies, including counselling for both bullies and victims.

1. Introduction

Healthy adjustment can be defined as the development of adequate skills and personal abilities for appropriately responding to environmental demands (Woodford et al., Citation2014). Healthy living depends on giving equal importance to physical, emotional and overall mental health (Sfeir et al., Citation2022). Numerous factors contribute to the impact on students’ mental health, with bullying being identified as a significant contributor that can leave lasting detrimental effects on an individual’s life and personality. For example, it has been shown that bullying and other forms of peer victimization are positively associated with lower mental health functioning (Lin et al., Citation2020). Bullying is considered an aggressive behavior arising from power imbalances (Burger et al., Citation2015). Researchers affiliated with the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (USA) have conducted a study that found that bullying encompasses a variety of forms of aggression, including both physical and verbal forms (Tappero et al., Citation2017). In bullying, repeated acts of physical, verbal, relational, or electronic abusive behavior (i.e., cyberbullying) are perpetrated by individuals or groups against less powerful peers in an effort to cause physical or psychological harm (Nansel et al., Citation2001). In contemporary terms, the act of intentionally harming others without electronic or digital methods is classified as “traditional bullying”, whereas the deliberate use of technology to inflict harm on others is known as cyberbullying. Traditional bullying can take place in school or in the neighborhood, whereas cyberbullying is a consequence of technological advancements, such as the Internet (Gladden et al., Citation2014). Traditional bullying can manifest itself as verbal, physical, or emotional abuse. In contrast, cyberbullying primarily takes the form of verbal or emotional abuse. Research has highlighted commonalities between traditional and cyberbullying behaviors, such as their unjustified aggression, power imbalances, and persistence over time (Dehue, Citation2013). However, despite these similarities, there are notable differences, as Smith (Citation2012) explains. Cyberbullying necessitates technological expertise, and the perpetrator is often unidentified, which means they do not typically witness the victim’s immediate reaction. Additionally, bystanders’ roles can be complex, and intentions vary compared to traditional bullying. Protecting oneself from cyberbullying proves to be intricate, as hurtful messages or content can be sent to a mobile device, computer, or website at any time and from anywhere, within seconds (Van Geel et al., Citation2014). However, Saleem et al. (Citation2022) stated that artificial intelligence methods have been documented for the automated identification of cyberbullying, which cannot be employed for conventional forms of bullying detection.

The rise of bullying in educational settings globally poses an increasing threat to students’ health (Ferrer-Cascales et al., Citation2019; Waasdorp et al., Citation2017), impacting individuals’ physical and mental health stability (Moore et al., Citation2017). Especially in the adolescent population, bullying and victimization are associated with increasing mental health issues (Inamullah et al., Citation2016; Murshid, Citation2017; Musharraf & Anis-Ul-Haque, Citation2018b; Nickerson, Citation2019; Shamsi et al., Citation2019). The problem becomes more acute in countries in poverty such as Pakistan due to the limited availability of resources to deal with mental health concerns. The presence of bullying and cyberbullying in Pakistani educational institutions has shown to adversely impact students’ physical, mental, and emotional health (Mirza et al., Citation2020; Musharraf & Anis-Ul-Haque, Citation2018b; Naveed et al., Citation2019, Citation2020; Saleem et al., Citation2021). A large body of literature has clearly confirmed that both traditional bullying and cyberbullying have now become commonplace in educational institutions in Pakistan. Bullying occurs at all levels of education, including primary, secondary, higher secondary, and university (Asif, Citation2016; Hakim & Shah, Citation2017; Mahmood & Islam, Citation2017; Magsi et al., Citation2017; McFarlane et al., Citation2017; Rafi, Citation2019; Siddiqui et al., Citation2021).

The existing international literature indicates that teacher-led interventions to address bullying problems have produced mixed results (van Verseveld et al., Citation2019). However, there is a lack of literature in Pakistan regarding the effectiveness of teacher-led intervention programs in curbing bullying and cyberbullying. Consequently, this article attempts to bridge this gap by exploring and contributing to the topic of tackling bullying and cyberbullying through teacher-led interventions in the Pakistani context. In this study, common approaches adopted in professional institutions to combat bullying are described.

1.1. Theoretical framework for the concept of bullying

The complexity of defining bullying is evident in the review of existing literature (Abbas et al., Citation2020). Summarizing existing definitions, Uz and Bayraktar (Citation2019) define bullying as repeated hostile behavior by an individual or group. It involves an imbalance of power and purposeful, conscious actions to intentionally harm the victim. Rigby (Citation2022, p. 2) describes bullying as the “systematic abuse of power”. The socio-ecological model is a framework proposed to explain and understand human development and can be applied to the complex nature of bullying. It considers multiple levels of influence that contribute to bullying behaviors (Swearer & Espelage, Citation2004). The model recognizes that behaviour is not solely an individual issue but shaped by various social and environmental factors (Bronfenbrenner, Citation1979). The elements encompassed in these factors include the personal characteristics of individuals, the dynamics of interpersonal relationships, the social context in which bullying takes place, the policies and practices within educational institutions, and the broader societal influences like media depictions of violence, socio-economic conditions, cultural contexts, and available support systems (Swearer & Espelage, Citation2004). Applying this framework, bullying is a multifaceted issue that requires a comprehensive understanding of the interplay between individual, relational, community, institutional, and societal factors. By considering these different levels of influence, interventions and prevention efforts can be designed to address bullying effectively at multiple levels.

1.2. Prevalence of bullying in educational institutions in Pakistan

Multiple studies in Pakistan found that bullying and cyberbullying are common antisocial behaviors in educational institutions (Perveen et al., Citation2022; Shahid et al., Citation2022). According to Saleem et al. (Citation2021), cyberbullying is on the rise in Pakistani educational institutions located in urban universities. Earlier studies by Musharraf and Anis-Ul-Haque (Citation2018a) also showed that cyberbullying involves more than 60% of students. In addition to higher education, studies have noted the spread of bullying and cyberbullying in the schooling systems of Pakistan (Burkhart & Keder, Citation2020; Naveed et al., Citation2019). According to Mahmood and Islam (Citation2017) and Shamsi et al. (Citation2019), bullying could happen anywhere at school, including the classroom, playground, bus, bathroom, and cafeteria. Shahzadi, Akram, Dawood, and Bibi (Citation2019) found that more than 50% of students harass their peers and more than 40% are victimized and/or fight to take revenge. Some studies show that both private and public sector schools are involved in bullying (Shahzadi, Akram, Dawood, & Bibi, Citation2019) while others have found that public sector students are more engaged than private sector school students in bullying, victimization and fighting (Shujja et al., Citation2014). A research study conducted in Pakistan has demonstrated that physical bullying diminishes as one progresses through the educational system (Siddiqui, Schultze-Krumbholz, Citation2023). This indicates that physical bullying is more common in primary schools than higher education institutions (Zych et al., Citation2020). Likewise, a study by Rafi (Citation2019) revealed that the probability of cyberbullying victimization diminishes as individuals grow older. Nevertheless, there were no notable variances found in alternative types of bullying, such as social or verbal bullying, across primary, secondary, college, and university-level students (Siddiqui, Schultze-Krumbholz, Citation2023). Based on a study carried out in Pakistan, individuals involved in cyberbullying primarily engage in such behavior to establish their social dominance and undermine others, often stemming from a power imbalance (Abbasi et al., Citation2018). In contrast, several international studies have provided detailed explanations that individuals involved in bullying and cyberbullying tend to exhibit higher levels of mistreatment, anxiety, academic challenges, passive-aggressive behaviors, internalizing and externalizing issues compared to their peers (Burkhart & Keder, Citation2020; Guo, Citation2016). The motivation behind bullying others includes a desire for power and elevated social status, as described by Salmivalli (Citation2010) who also explored the prevalence of bullying incidents and examined them through the lens of social learning theory. Bystanders often imitate the behavior of bullies to tap into the social influence generated by their popularity and out of fear of becoming the next victim themselves among their peers. By modeling the actions of bullies, bystanders aim to gain prominence and popularity, and this inclination is intensified when they repeatedly observe similar experiences. Nevertheless, the investigation of the primary motivations behind students’ involvement in bullying in Pakistan, as well as the variation of these motivations across different educational levels, remains an understudied topic within the context of Pakistan. It is worth noting that Pakistan exhibits significant disparities in educational systems, particularly in rural regions, largely due to feudalism. Feudalism represents a major barrier to the advancement and availability of education in these rural areas (Javaid & Ranjha, Citation2017; Khan et al., Citation2013).

1.3. Strategies for coping with bullying

To handle bullying issues in an educational setting, a cost-effective solution is to professionally train teachers on how to address bullying. In terms of professional development programs for teachers, the assumption is that they are the primary agents capable of modifying the school environment by utilizing their competencies to reduce bullying and victimization (Strohmeier et al., Citation2012). However, teacher-led interventions have shown varying results when it comes to controlling bullying issues (van Verseveld et al., Citation2019). Despite numerous studies conducted internationally, teachers in Pakistan are still only superficially aware of bullying as well as inadequately aware of bullying forms and how to control or intervene in bullying situations (Hakim & Shah, Citation2017). Studies have indicated that there are no satisfactory anti-bullying interventions in educational institutions in Pakistan because the primary goal of education is to achieve grades only (Ahmed et al., Citation2022; Bokhari et al., Citation2022). A frequently applied method to handle disruptive behavior in Pakistani school settings is punishment (Ansari, Citation2022; Niwaz et al., Citation2021; Suleman et al., Citation2013). Some teachers isolate students, while others strike students or apply physical punishment in response to bullying (Niwaz et al., Citation2021). In some schools, students are praised and rewarded for well-organized behavior to get their peers to realize the desirable and the undesirable behavior, and some schools offer single counseling, parent meetings, and organizing lectures on moral conduct with colleagues, while others emphasize establishing rules of discipline and enforcing them (Niwaz et al., Citation2021). Some strategies to engage disruptive students can include assigning them a class leadership role (Niwaz et al., Citation2021).

Earlier research by Hakim and Shah (Citation2017) indicates that in order to control bullying, some schools take measures such as providing a safe physical environment, designing activities and providing clear instructions on how to proceed with them, teaching students about conflict management, providing staff with bullying prevention training, collaborating with parents, assessing the extent of the problem and taking early intervention, increasing supervision by adults and taking reactive measures. Reactive measures are those where actions against bullying are taken once cases are reported or identified to buffer the negative consequences of victimization, helping victims cope through emotional regulation strategies and counseling of the perpetrator (Barlett et al., Citation2021). However, it was observed by the authors that very few schools take initiatives to encourage their students to report bullying incidents. In a study by McFarlane et al. (Citation2017), for example, approximately half of female victims of cyberbullying indicated that they did not come forward due to the religious and cultural stigma of being avoided as immoral. In response to cyberbullying, they adopted a strategy of silence and avoidance regarding the participation in online activities. Given the lack of knowledge about cyberbullying and the inability to rely on the courts/law enforcement organizations, this is not surprising. According to a study carried out in Pakistan, peers are the least inclined to intervene or notify teachers about bullying incidents, despite being a significant factor in bullying (Siddiqui, Schultze-Krumbholz, Citation2023). Gordon (Citation2019) presented several reasons why peers refrain from reporting or disclosing such incidents to adults, including concerns about potential victimization for reporting or intervening, insufficient understanding of how to handle such situations, distrust of adults, prior instruction to avoid such situations, and moral disengagement beliefs.

1.4. Teachers’ perceptions of bullying in Pakistan

Teachers confirm the frequency and school spaces where bullying and harassment is commonly observed (Hassan, Citation2020). However, research indicates that teachers’ knowledge about bullying depends upon qualification, teaching experience and their access to professional development trainings (Shamsi et al., Citation2019; Shujja et al., Citation2014). According to the studies, the majority of teachers lack adequate knowledge (Shamsi et al., Citation2019), many reported verbal or physical constitutes of bullying such as mimicking, pushing, hitting, however, very few possessed the knowledge regarding the emotional aspect of bullying (Shujja et al., Citation2014).

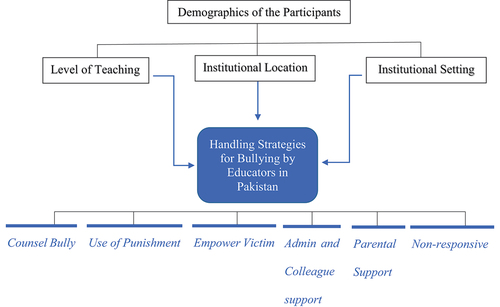

Teachers are the most important actors who can influence the whole school environment by initiating action against bullying and victimization through their competencies (Strohmeier et al., Citation2012). A constant presence of teachers in classrooms throughout the school day also allows students to seek help when they experience or observe bullying or victimization. When designing a teacher-led intervention, it is critical to obtain information from teachers about bullying in institutions and to solicit their opinions about common strategies they use to address bullying. With this goal in mind, this study was designed to obtain the necessary information from teachers as a prerequisite before designing and implementing a teacher-led intervention program (Sohanjana Antibullying Intervention; Siddiqui, Schultze-Krumbholz, Citation2023). In the context of Pakistani educational institutions literature on intervention strategies of teachers is still scarce. The main aim of the present study is to describe how Pakistani teachers combat bullying in their professional institutions to provide a starting point for teachers’ professional development approaches. Furthermore, we investigated the effect of educational and institutional settings on different categories of bullying intervention strategies. For the frame work of the study refer to Figure .

1.5. Research questions of the study

The research study is designed to answer the following research questions:

How do educators in Pakistan respond when bullying occurs?

How do strategies for addressing bullying differ between educators in rural and urban settings and across various educational levels?

2. Methods

Teachers’ perceptions of bullying and common strategies for controlling it are explored in this article. To collect data, the Handling Bullying Questionnaire by Bauman et al. (Citation2008) was used in a cross-sectional survey approach. The aim of the overall research project was to develop a comprehensive contextualized antibullying intervention for teachers in Pakistani educational institutions, for which the present study was conducted as part of a baseline need assessment.

2.1. Participants and sampling technique

A questionnaire survey was conducted online using Google forms. In order to collect data over 1,000 forms were sent to educators working at different educational institutions in Pakistan. Teachers were also asked to pass on the link to the questionnaire to their colleagues in order to facilitate the research and collect the maximum amount of data for interpretation.

The majority of participants were from the provinces of Sindh and Punjab, and the rural and urban areas within these provinces were very much reflected in the sample. According to the APA’s ethical code, researchers adhered to the basic ethical principles as far as teachers were involved and voluntariness of participation was ensured. The purpose of the study was explained to educators and they had the option to withdraw. In addition, a statement of anonymity, free participation, planned use of data, and the right to end participation without negative consequences was provided to the participants in the introduction part of the survey. They explicitly agreed to these study conditions by clicking the “Agree” button (opt-in) at the beginning of the online survey. A summary of the demographics of the participants is shown in Table .

Table 1. Demographics

2.2. Measure

For data collection along with the demographic questions (see Table ), the items of the Handling Bullying Questionnaire (developed by Bauman et al., Citation2008; and validated by; Shahzadi, Akram, Dawood, & Ahmad, Citation2019) were used. The questionnaire assesses the prevailing approaches employed by educators in institutions to address bullying incidents. This tool is a relatively recent development and has undergone validation in numerous international research studies (Burger et al., Citation2015; Grumm & Hein, Citation2013; Novocký et al., Citation2021; van der Zanden et al., Citation2015), including a study conducted in Pakistan by Shahzadi, Akram, Dawood, and Ahmad (Citation2019). The questionnaire consisted of 22 items on a 5-point Likert Scale (1= I definitely would not, 5= I definitely would). A scenario presented at the beginning of the questionnaire asked teachers if they had seen a 12-year-old student being repeatedly bullied verbally and socially and as a consequence feeling isolated and showing emotional outbursts, how would they react to handle this situation? In response to the situation, there were many statements which were grouped and analyzed. Example statements are I would ask the school counsellor/owner to intervene, I would make sure the bully was suitably/appropriately punished etc.

2.3. Data analysis

Data analysis was conducted using SPSS version 27 and AMOS version 24. Exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses were computed. Data were analyzed through descriptive statistics and a one-way ANOVA. Normality can have serious effects in small samples, but the impact diminishes as the sample size reaches 50 according to de Winter et al. (Citation2009). Since each sample contains a large number of observations (n = 454), the sampling distribution of the mean was assumed to be normal.

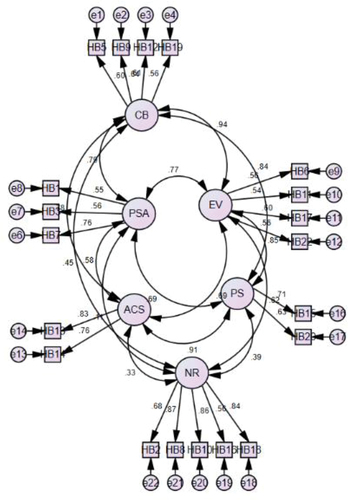

2.4. Factor analysis, reliability, validity and model fitness

The original questionnaire was based on 22 questions, however after confirmatory factor analysis 2 items (item 4 and item 21) were removed. Factor loadings are shown in Figure and frequencies of responses are shown in Table . For every construct, Cronbach’s α is higher than 0.5, indicating that the subscales are reliable (Cronbach, Citation1951) and Average Variance Extracted (AVE) is 66% confirming that the instrument is valid for testing. Further, indicators of model fit show that the model fits the data well (CFI = .911, GFI = .903, AGFI = .868, IFI = .912, RMSEA = .068, PCFI = .743, PNFI = .713). The final questionnaire used in the subsequent analyses consisted of 20 items and was divided into six subscales: “Counselling Bully” (4 items, Cronbach’s α = 0.69), “Informing admin and colleagues and getting support from them” (2 items, Cronbach’s α = 0.78), “Involving parents of both bully and victim and getting support from them” (2 items, Cronbach’s α = 0.62), “Counselling and empowering the victim to stand and defend against bully” (4 items, Cronbach’s α = 0.65), “Taking no responsibility by assuming that students can resolve it by themselves” (5 items, Cronbach’s α = 0.88), and “Using punishments and strict action against the bully” (3 items, Cronbach’s α = 0.65).

Figure 2. Factor Analysis for the Handling Bullying Questionnaire; CB = Counselling Bully, ACS = Admin and Colleague Support; PS=Parental Support; EV= Empowering Victim; NR= No Responsibility/Non-responsive; PSA=Punishment and Strict Action.

Table 2. Details of questionnaire and frequencies of responses

3. Results

3.1. Frequency of strategies used to control bullying

The primary purpose of this study was to determine what types of strategies are most commonly used in dealing with bullying. The descriptive results show that punishment (mean = 4.4383) is still the most common strategy used by teachers in Pakistan to deal with bullying (see Table ).

Table 3. Descriptive statistics

3.2. Influence of school demographics on use of bullying strategies

To determine the demographic differences in the use of different strategies to intervene in bullying incidents, one-way ANOVAs were conducted. According to de Winter et al. (Citation2009) a sample greater than n = 30 can be considered to be normally distributed. Hair et al. (Citation2010) and Byrne (Citation2010) argue that data is considered to be normally distributed if skewness is between ‐2 to + 2 and kurtosis is between ‐7 to + 7. In the present study skewness and kurtosis values are within the suggested range, so it is assumed that normal distribution is achieved (refer to Table ). Due to the absence of a definitive test, researchers have made concerted efforts to minimize potential biases and dependencies among observations. It was assumed that there are no hidden relationships or correlations between the variables as data were collected using a valid statistical sampling method. In addition, the data collection process ensured that there were no identifiable systematic relationships or connections between the observations within each group.

Levene’s test was also used to assess the equality of variances. For post hoc analysis, the choice of either the Tukey or Games-Howell method depended on the significance value obtained from Levene’s test. The Tukey method was used when the Levene test was not significant, while the Games-Howell method was used when the Levene test was significant. Unlike Tukey’s test, the Games-Howell test does not assume equal variances or sample sizes, making it a suitable alternative.

A significant difference was found in parental support at the different levels of instruction (primary, secondary, higher secondary, and university) (see Table ). Post-hoc analysis using the Games-Howell method revealed a significant difference in terms of parental support between primary (N = 101, mean = 4.4901, Std. Deviation = 0.6993) and university levels of teaching (N = 107, mean = 4.186, Std. Deviation = 0.8054) (see Table ) indicating that university educators are less likely to involve parents in handling bullying situations.

Table 4. ANOVA independent variable: Teaching level (primary, secondary, higher secondary, university)

Table 5. Post Hoc (Multiple comparisons)

To determine the effect of institutional location (urban, rural, and sub-urban) on bullying intervention, a one-way ANOVA was conducted and revealed a significant difference in terms of punishment as a strategy and showing no response by the teacher (refer to Table ). Post-hoc analysis using the Tukey method results for punishment indicated a significant difference in using punishment among teachers from remote areas (N = 63, mean = 4.17, Std. Deviation = 0.757) and urban institutions (N = 364, mean = 4.49, Std. Deviation = 0.684), with teachers from urban educational institutions more frequently using punishment as a bullying intervention (refer to Table ). In addition, using Games-Howell post hoc analysis a significant difference was found between teachers from rural areas (N = 63, mean = 3.64, standard deviation = 1.08) and urban areas (N = 364, mean = 3.09, standard deviation = 1.23) indicating that no response or ignoring bullying incidents takes place more often in rural schools (refer to Table ).

Table 6. ANOVA independent variable: Institutional location (Urban, rural, sub-urban)

Table 7. Post Hoc (Multiple comparisons)

Finally, the influence of institutional setting (public, private, semi-private) on bullying strategies was tested using one-way ANOVA, but no significant difference in terms of institutional setting was observed (p-value > 0.05).

4. Discussion

Philosophies and ideologies behind anti-bullying strategies vary among different cultures and educators. One of the main purposes of this research study was to identify the common beliefs and strategies of educators in Pakistan to respond to bullying incidents. Some strategies are based on the belief that demoralizing behavior can be controlled through punishments where educators believe that the severity of sanctions for bullying behavior serves as an effective deterrent (Roberge, Citation2012). There are studies that report that to control bullying and undesirable behaviors, strict and punitive measures are considered an effective strategy (Ahmed et al., Citation2022; Patchin & Hinduja, Citation2018). However, in other research-based studies, punitive interventions such as detention, suspension, or informing parents were not found to be as effective as hypothesized (Ayers et al., Citation2012). In addition, the risk of harsh punishment discourages students from reporting bullying incidents. Similarly, strict zero-tolerance policies have been shown to be ineffective in reducing bullying, even when the bully is expelled from the institution (Berlowitz et al., Citation2017). Research has also clearly demonstrated that students will not improve their behavior in the long term if the change is based on fear rather than insight (Oxley, Citation2021). In addition, the removal of the bully could further complicate his/her developmental direction, since bullying behaviors can be an early marker of other associated behavioral and developmental problems. In the present study, a majority of respondents believe that punishment is the most effective method for controlling bullying in educational institutions. This is in line with previous research studies (Ansari, Citation2022; Niwaz et al., Citation2021; Suleman et al., Citation2013). An explanation might be that for discipline purposes, children are normally rewarded and lightly penalized in Islamic society (Nazri et al., Citation2005) and punishing students for any immoral act is a conventional and acceptable practice in Pakistan’s society. However, many researchers have recommended that instead of punishing and taking strict punitive actions, it is important to understand the motivation of the perpetrator(s) and encourage them to act positively in their relations with others (Rigby & Griffiths, Citation2018). Based on the humanistic approach it is concluded that the implementation of antibullying policies should not start with severe sanctions or penalties and educators should be provided with training to use other strategies instead of directly starting with punishments.

One major difference was also found between rural and urban teachers regarding their belief in punishing students for bullying. Surprisingly, teachers from urban schools preferred punishment more often as compared to teachers from rural schools. In Pakistan there are huge differences in educational setups, especially in rural areas, because of feudalism which is also one of the main obstacles to promotion and accessibility of education in rural areas (Javaid & Ranjha, Citation2017; Khan et al., Citation2013). The majority of participants in the study were from the Sindh and Punjab regions, where feudalism is still a common practice. We assume that the influence of feudal lords in these regions may be a contributor to the observed variations. Students who have access to education in rural areas are more likely to be from elite family backgrounds such as from feudal lords and are usually considered influential in their areas. One possible explanation for the differences could be that teachers in rural areas may be reluctant to take harsh punitive measures against students from privileged backgrounds out of fear or apprehension. In the same line, ignoring bullying incidents more often, as shown in our data, may be a good strategy for rural teachers to avoid negative consequences from sanctioning influential students. Also, some studies reported that behavioral problems are more common among students from urban backgrounds (Nelson et al., Citation2010; Springer et al., Citation2006). There is a possibility that due to less cases from rural backgrounds, teachers are not frequently using punishment as a strategy and thus are less in favor of taking actions against students through strict penalties. However, repeated perpetration of aggressive behaviors by urban students may make it difficult for urban teachers to use other time-consuming strategies. Another possible reason for this difference may be the large number of students per class in urban education systems, making it difficult for teachers to handle bullying repeatedly with other strategies due to a lack of time and a large number of commitments (Ejaz & Mallawaarachchi, Citation2022). Moreover, the focus of education in Pakistan, especially in urban areas, is on achieving good grades (Ahmed et al., Citation2022) and to that aim, there is a possibility that teachers are reluctant to spend more time on the behavioral development of children through counselling or other strategies, hence punishing a child seems the effortless and prompt strategy. However, subsequent empirical studies have revealed that punitive measures are not as effective as previously assumed in addressing bullying issues (Ayers et al., Citation2012).

The third major finding of the present study is that involving parents to control bullying related behaviors decreases when students are matured enough and engaged with university studies. The transition from high school or secondary school to university requires students to integrate into adult life, including increasing responsibility for themselves, independence in their decisions, and financial independence. The development of this independence entails a gradual detachment from parents, so that as adolescents gain more confidence and experience in their ventures, they move from parental dependence to independence. Similarly, during this transition phase, parental interaction with faculty and administrators at the university level decreases significantly (Lowe & Dotterer, Citation2018). However, there are studies that suggest parental involvement is appropriate for the developmental phase of emerging adulthood and the context of the transition to university (Lowe & Dotterer, Citation2018). Also, a mixed methods study conducted in Pakistan found that university-level students prefer to solve their problems independently without involving their parents, but there is also evidence that parent involvement in addressing misbehavior or bullying has led to positive outcomes compared to institutional efforts alone (Cross et al., Citation2018; Van Niejenhuis et al., Citation2020). A similar difference was observed in data in which university instructors rarely involved parents in addressing bullying issues (Gaffney et al., Citation2021; Kolbert et al., Citation2014). However, most studies involving parents in anti-bullying interventions were conducted at the school level. There are hardly any studies about involving parents in antibullying policies (Chen et al., Citation2021) at the university level and this area still needs more research.

5. Conclusion

Various previous studies have reported the prevalence of bullying and cyberbullying within educational institutions in Pakistan (Naveed et al., Citation2020; Saleem et al., Citation2021; Siddiqui, Schultze-Krumbholz, Citation2023). However, there remains a lack of research on teachers’ common strategies to address antisocial behavior (Siddiqui, Kazmi, et al., Citation2023). The current study suggests that while punishment is not deemed an appropriate approach, it is still employed more frequently by teachers, particularly those in urban areas. Additionally, teachers in rural regions tend to ignore the situation, influenced by societal norms and challenges. The strategy of involving parents to address bullying was the least used strategy among university teachers. Furthermore, despite significant differences between public and private sector institutions in Pakistan, the current study did not find any significant differences in the use of anti-bullying strategies among teachers from public, private or semi-private educational institutions. This research suggests that despite international interventions advocating for more productive and effective strategies such as counseling, teachers in Pakistan lack the necessary skills and require training to comprehend the importance of and implement more effective approaches that address the root causes of these issues.

5.1. Implications

The incorporation of legislative and punitive measures against bullying and aggression requires careful consideration across different cultures. Physical punishment is also considered harmful by Islam which is the most practiced religion in the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, which prohibits penalties and only allows it as a last resort. The use of sanctions and penalties has produced varying results across cultures and is a gray area of research. Teachers in Pakistan, however, regularly resort to this strategy. To tackle these issues in institutions and to create a conducive learning environment, educators should be trained to use other effective strategies such as empowering victims and counselling bullying more frequently. A proven method to control antisocial and bullying behavior is counseling, but unfortunately the ability to counsel and communicate is not taught formally to teachers (Esere & Mustapha, Citation2018; Ferris et al., Citation2021; Ullah et al., Citation2011; Waasdorp et al., Citation2021). Therefore, it is common for teachers to avoid these issues altogether while others get in over their heads due to a lack of training and feeling unprepared. Consequently, researchers recommend that teachers undergo training regarding counseling and communication to handle bullying with more expertise (Ullah et al., Citation2011).

5.2. Limitations

A self-report questionnaire was used for data collection in the present study because it is an efficient and economically cost-effective method; however, it was not considered ideal because the resulting data may be inaccurate due to recall issues. Rovai et al. (Citation2014) noted that self-reports are among the least reliable measurement tools, but in the absence of alternatives and to identify faculty responses, participants checked-off responses are considered accurate. It is recommended that multiple measures be used for each construct to obtain more reliable results.

6. Ethics declarations

6.1. Ethical statement

The researchers followed basic ethical principles and the APA’s ethical code. The study took place outside of online classes and during students’ leisure time. Participants were adults who gave their informed consent and the questionnaire did not relate to their own victimization experiences thus the probability of re-victimization was low. Ethical review and approval were not required for the study on human participants in accordance with local legislation and institutional requirements. The entire study and questionnaire were reviewed by the second author’s research team consisting of educational psychologists and educationalists and two educators from a private university in the Metropolis City of Pakistan who are well acquainted with the educational system of Pakistan. The team of reviewers found no potential conflict of interest or harm to participants, nor any activities that went beyond the ethical code of conduct.

6.2. Informed consent

The participants gave informed consent using an online forum, which can be considered written consent. They were provided with information about the study’s purpose, the statement of anonymity, the option to participate freely, the intended use of the data, and the right to withdraw from the study without negative repercussions. After reading and acknowledging these conditions, the participants explicitly agreed to them by clicking the “Agree” button at the beginning of the online survey. This process ensured that informed consent was obtained in accordance with ethical guidelines and federal legislation.

Acknowledgement

The researchers acknowledge the support from the German Research Foundation and the Open Access Publication Fund of TU Berlin.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Sohni Siddiqui

Sohni Siddiqui, an external researcher and doctoral candidate at the Department of Educational Psychology, Technische Universität Berlin, focuses her research on the professional development of teachers to address issues related to antisocial bullying and cyberbullying in educational settings.

Anja Schultze-Krumbholz

Prof. Dr. Anja Schultze-Krumbholz is currently serving as a visiting professor and deputy head of the Department of Educational Psychology at TU Berlin. Her current research focuses are in the areas of social and emotional competence in children and adolescents, aggression in children and adolescents, bullying and cyberbullying, prevention of aggression in schools and evaluation of prevention and intervention measures in schools.

Preeta Hinduja

Preeta Hinduja serves as a visiting faculty member at different universities in the metropolis city of Karachi, Pakistan. She has completed an M.Phil. in Education from Iqra University, Karachi, Pakistan, where she is continuing her Ph.D. in Education. Her research interests include assessment and evaluation, educational psychology and teacher education.

References

- Abbas, N., Ashiq, U., & Iqbal, M. (2020). Teachers’ perceived contributing factors of school bullying in public elementary schools. Journal of Educational Research, 23(1), 19–21.

- Abbasi, S., Naseem, A., Shamim, A., & Qureshi, M. A. (2018, November). An empirical investigation of motives, nature and online sources of cyberbullying. In 2018 14th International Conference on Emerging Technologies (ICET) (pp. 1–6). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICET.2018.8603617

- Ahmed, B., Yousaf, F. N., Ahmad, A., Zohra, T., & Ullah, W. (2022). Bullying in educational institutions: College students’ experiences. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2022.2067338

- Ansari, M., (2022). Corporal punishment as a culture. https://www.dawn.com/news/1667931

- Asif, A. (2016). Relationship between bullying and behavior problems (anxiety, depression, stress) among adolescence: Impact on academic performance. MedCrave Group LLC.

- Ayers, S. L., Wagaman, M. A., Geiger, J. M., Bermudez-Parsai, M., & Hedberg, E. C. (2012). Examining school-based bullying interventions using multilevel discrete time hazard modeling. Prevention Science, 13(5), 539–550. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-012-0280-7

- Barlett, C. P., Simmers, M. M., & Seyfert, L. W. (2021). Advances in the cyberbullying literature: Theory-based interventions. In F. W. Michelle & B. S. Lawrence (Eds.), Child and adolescent online risk exposure (pp. 351–378). Academic Press.

- Bauman, S., Rigby, K., & Hoppa, K. (2008). US teachers’ and school counsellors’ strategies for handling school bullying incidents. Educational Psychology, 28(7), 837–856. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410802379085

- Berlowitz, M. J., Frye, R., & Jette, K. M. (2017). Bullying and zero-tolerance policies: The school to prison pipeline. Multicultural Learning and Teaching, 12(1), 7–25. https://doi.org/10.1515/mlt-2014-0004

- Bokhari, U., Shoaib, U., Ijaz, F., Aftab, R. K., & Ijaz, M. (2022). Effects of bullying on the mental health of adolescents. The Professional Medical Journal, 29(7), 1073–1077. https://doi.org/10.29309/TPMJ/2022.29.07.5792

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Harvard university press.

- Burger, C., Strohmeier, D., Spröber, N., Bauman, S., & Rigby, K. (2015). How teachers respond to school bullying: An examination of self-reported intervention strategy use, moderator effects, and concurrent use of multiple strategies. Teaching and Teacher Education, 51, 191–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2015.07.004

- Burkhart, K., & Keder, R. D. (2020). Bullying: The role of the clinician in prevention and intervention. In Clinician’s toolkit for children’s behavioral health (pp. 143–173). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-816024-4.00007-3

- Byrne, B. M. (2010). Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. Routledge.

- Chen, Q., Zhu, Y., & Chui, W. H. (2021). A meta-analysis on effects of parenting programs on bullying prevention. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 22(5), 1209–1220. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838020915619

- Cronbach, L. J. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika, 16(3), 297–334. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02310555

- Cross, D., Lester, L., Pearce, N., Barnes, A., & Beatty, S. (2018). A group randomized controlled trial evaluating parent involvement in whole-school actions to reduce bullying. The Journal of Educational Research, 111(3), 255–267. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.2016.1246409

- Dehue, F. (2013). Cyberbullying research: New perspectives and alternative methodologies. introduction to the special issue. Journal of Community and Applied Social Psychology, 23(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.2139

- de Winter, J. C. F., Dodou, D., & Wieringa, P. A. (2009). Exploratory factor analysis with small sample sizes. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 44(2), 147–181. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273170902794206

- Ejaz, N., & Mallawaarachchi, T. (2022). Disparities in economic achievement across the rural–urban divide in Pakistan: Implications for development planning. Economic Analysis and Policy, 77, 487–512. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eap.2022.11.023

- Esere, M. O., & Mustapha, M. L. (2018). Counselling strategies for modifying bullying behaviour in Nigerian schools. KIU Journal of Humanities, 3(2), 249–264. https://www.ijhumas.com/ojs/index.php/kiuhums/article/view/316

- Ferrer-Cascales, R., Albaladejo-Blázquez, N., Sánchez-SanSegundo, M., Portilla-Tamarit, I., Lordan, O., & Ruiz-Robledillo, N. Effectiveness of the TEI program for bullying and cyberbullying reduction and school climate improvement. (2019). International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(4), 580. Article 580. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16040580

- Ferris, P. A., Tilley, L., Stevens, F., & Tanchak, S. (2021). The roles of the counselling professional in treating targets and perpetrators of workplace bullying. In D. Premilla, N. Ernesto, B. Elfi, C. Bevan, H. Karen, H. Annie, & G. M. Eva (Eds.), Pathways of job-related negative behaviour (Vol. 2, pp. 447–475). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-0935-9_16

- Gaffney, H., Ttofi, M. M., & Farrington, D. P. (2021). What works in anti-bullying programs? Analysis of effective intervention components. Journal of School Psychology, 85, 37–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2020.12.002

- Gladden, R. M., Vivolo-Kantor, A. M., Hamburger, M. E., & Lumpkin, C. D. (2014). Bullying Surveillance among Youths: Uniform Definitions for Public Health and Recommended Data Elements. Version 1.0. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- Gordon, S. (2019). Reasons why bystanders do not speak up. Available from: https://www.verywellfamily.com/reasons-why-bystanders-remain-silent-460741

- Grumm, M., & Hein, S. (2013). Correlates of teachers’ ways of handling bullying. School Psychology International, 34(3), 299–312. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034312461467

- Guo, S. (2016). A meta‐analysis of the predictors of cyberbullying perpetration and victimization. Psychology in the Schools, 53(4), 432–453. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.21914

- Hair, J., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.). Pearson Educational International.

- Hakim, F., & Shah, S. A. (2017). Investigation of bullying controlling strategies by primary school teachers at District Haripur. Peshawar Journal of Psychology & Behavioral Sciences (PJPBS), 3(2), 165–174. https://doi.org/10.32879/pjpbs.2017.3.2.165-174

- Hassan, S., (2020) Friends and teachers asked to stand up against bullying. dawn.com/news/1534263

- Inamullah, H. M., Irshadullah, M., & Shah, J. (2016). An investigation to the causes and effects of bullying in secondary schools of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. The Sindh University Journal of Education-SUJE, 45(1), 67–86.

- Javaid, U., & Ranjha, T. A. (2017). Feudalism in Pakistan: Myth or reality/challenges to feudalism. Journal of the Research Society of Pakistan, 54(1), 227–235. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3805954

- Khan, J., Dasti, H. A., & Khan, A. R. (2013). Feudalism is a major obstacle in the way of social mobility in Pakistan. Journal of the Research Society of Pakistan, 50(1), 135–148.

- Kolbert, J. B., Schultz, D., & Crothers, L. M. (2014). Bullying prevention and the parent involvement model. Journal of School Counseling, 12(7), 1–20. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1034733

- Lin, M., Wolke, D., Schneider, S., & Margraf, J. (2020). Bullying history and mental health in university students: The mediator roles of social support, personal resilience, and self-efficacy. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10(960). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00960

- Lowe, K., & Dotterer, A. M. (2018). Parental involvement during the college transition: A review and suggestion for its conceptual definition. Adolescent Research Review, 3(1), 29–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40894-017-0058-z

- Magsi, H., Agha, N., & Magsi, I. (2017). Understanding cyber bullying in Pakistani context: Causes and effects on young female university students in Sindh province. New Horizons, 11(1), 103–110.

- Mahmood, S., & Islam, S. (2017). Bullying at high schools: Scenario of Dhaka City. Journal of Advanced Laboratory Research in Biology, 8(4), 79–84.

- McFarlane, J., Karmaliani, R., Khuwaja, H. M. A., Gulzar, S., Somani, R., Ali, T. S., Somani, Y. H., Bhamani, S. S., Krone, R. D., Paulson, R. M., Muhammad, A., & Jewkes, R. (2017). Preventing peer violence against children: Methods and baseline data of a cluster randomized controlled trial in Pakistan. Global Health Science and Practice, 5(1), 115–137. https://doi.org/10.9745/GHSP-D-16-00215

- Mirza, M. S., Azmat, S., & Malik, S. Z. (2020). A comparative study of cyber bullying among online and conventional students of higher education institutions in Pakistan. Journal of Educational Sciences and Research, 7(2), 87–100. https://jesar.su.edu.pk/uploads/journals/Article_74.pdf

- Moore, S. E., Norman, R. E., Suetani, S., Thomas, H. J., Sly, P. D., & Scott, J. G. (2017). Consequences of bullying victimization in childhood and adolescence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World Journal of Psychiatry, 7(1), 60–76. https://doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v7.i1.60

- Murshid, N. S. (2017). Bullying victimization and mental health outcomes of adolescents in Myanmar, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka. Children and Youth Services Review, 76, 163–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.03.003

- Musharraf, S., & Anis-Ul-Haque, M. (2018a). Cyberbullying in different participant roles: Exploring differences in psychopathology and well-being in university students. Pakistan Journal of Medical Research, 57(1), 33–39.

- Musharraf, S., & Anis-Ul-Haque, M. (2018b). Impact of cyber aggression and cyber victimization on mental health and well-being of Pakistani young adults: The moderating role of gender. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 27(9), 942–958. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926771.2017.1422838

- Nansel, T. R., Overpeck, M., Pilla, R. S., Ruan, W. J., Simons-Morton, B., & Scheidt, P. (2001). Bullying behaviors among US youth: Prevalence and association with psychosocial adjustment. Journal of the American Medical Association, 285(16), 2094–2100. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.285.16.2094.Ni

- Naveed, S., Waqas, A., Aedma, K. K., Afzaal, T., & Majeed, M. H. (2019). Association of bullying experiences with depressive symptoms and psychosocial functioning among school going children and adolescents. BMC Research Notes, 12(1), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-019-4236-x

- Naveed, S., Waqas, A., Shah, Z., Ahmad, W., Wasim, M., Rasheed, J., & Afzaal, T. (2020). Trends in bullying and emotional and behavioral difficulties among Pakistani schoolchildren: A cross-sectional survey of seven cities. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10, 976. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00976

- Nazri, M. K. N. Z., Ahmad, M., Yusoff, A. M., Amin, F. M., & Ishak, M. M. (2005). The concept of rewards and punishments in Sahih Bukhari with special reference to kitab Al-Adab. Jurnal Usuluddin, 22, 105–120. https://bit.ly/3OU1rAn

- Nelson, D. M., Coleman, D., & Corcoran, K. (2010). Emotional and behavior problems in urban and rural adjudicated males: Differences in risk and protective factors. Victims and Offenders, 5(2), 120–129. https://doi.org/10.1080/15564881003640710

- Nickerson, A. B. (2019). Preventing and intervening with bullying in schools: A framework for evidence-based practice. School Mental Health, 11(1), 15–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-017-9221-8

- Niwaz, A., Khan, K., & Naz, S. (2021). Exploring teachers’ classroom management strategies dealing with disruptive behavior of students in public schools. Ilkogretim Online, 20(2), 1596–1617. https://doi.org/10.17051/ilkonline.2021.02.181

- Novocký, M., Dulovics, M., & Petrík, Š. (2021). Monitoring elementary school teachers’ approaches to handling bullying among students. New Educational Review, 65(3), 213–223. https://doi.org/10.15804/tner.21.65.3.17

- Oxley, L. (2021). Alternative approaches to behaviour management in schools: Diverging from a focus on punishment [ Doctoral dissertation], University of York.

- Patchin, J. W., & Hinduja, S. (2018). Deterring teen bullying: Assessing the impact of perceived punishment from police, schools, and parents. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice, 16(2), 190–207. https://doi.org/10.1177/1541204016681057

- Perveen, S., Kanwal, M., & Bibi, H. (2022). Bullying and harassment in relation to mental health: A closer focus on education system. Journal of Educational Research and Social Sciences Review (JERSSR), 2(1), 32–38. https://ojs.jerssr.org.pk/index.php/jerssr/article/view/53/24

- Rafi, M. S. (2019). Cyberbullying in Pakistan: Positioning the aggressor, victim, and bystander. Pakistan Journal of Psychological Research, 34(3), 601–620. https://doi.org/10.33824/PJPR.2019.34.3.33

- Rigby, K. (2022). Theoretical perspectives and two explanatory models of school bullying. International Journal of Bullying Prevention. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42380-022-00141-x

- Rigby, K., & Griffiths, C. (2018). Addressing traditional school-based bullying more effectively. In C. M. Marilyn & B. Sheri (Eds.), Reducing cyberbullying in schools (pp. 17–32). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-811423-0.00002-X

- Roberge, G. D. (2012). From zero tolerance to early intervention: The evolution of school anti-bullying policy. Journal of Education Policy, 1(5), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.22230/ijepl.2011v6n5a305

- Rovai, A. P., Baker, J. D., & Ponton, M. K. (2014). Social science research design and statistics: A practitioner’s guide to research methods and IBM SPSS analysis (2nd ed.). Watertree Press.

- Saleem, S., Khan, N. F., & Zafar, S. (2021). Prevalence of cyberbullying victimization among Pakistani Youth. Technology in Society, 65, 101577. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2021.101577

- Saleem, S., Khan, N. F., Zafar, S., & Raza, N. (2022). Systematic literature reviews in cyberbullying/cyber harassment: A tertiary study. Technology in Society, 70, 102055. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2022.102055

- Salmivalli, C. (2010). Bullying and the peer group: A review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 15(2), 112–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2009.08.007

- Sfeir, M., Akel, M., Hallit, S., & Obeid, S. (2022). Factors associated with general well-being among Lebanese adults: The role of emotional intelligence, fear of COVID, healthy lifestyle, coping strategies (avoidance and approach). Current Psychology, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02549-y

- Shahid, M., Rauf, U., Sarwar, U., & Asif, S. (2022). Impact of bullying behavior on mental health and quality of life among pre-adolescents and adolescents in Sialkot-Pakistan. Pakistan Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, 10(1), 324–331. https://doi.org/10.52131/pjhss.2022.1001.0200

- Shahzadi, N., Akram, B., Dawood, S., & Ahmad, F. (2019). Translation, validation and factor structure of the handling bullying questionnaire in Pakistan. Pakistan Journal of Psychological Research, 34(3), 497–510. https://doi.org/10.33824/PJPR.2019.34.3.27

- Shahzadi, N., Akram, B., Dawood, S., & Bibi, B. (2019). Bullying behavior in rural area schools of Gujrat, Pakistan: Prevalence and gender differences. Pakistan Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 17(1), 25–30. https://gcu.edu.pk/pages/gcupress/pjscp/volumes/pjscp20191-4.pdf

- Shamsi, N. I., Andrades, M., & Ashraf, H. (2019). Bullying in school children: How much do teachers know? Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care, 8(7), 2395–2400. https://doi.org/10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_370_19

- Shujja, S., Atta, M., & Shujjat, J. M. (2014). Prevalence of bullying and victimization among sixth graders with reference to gender, socio-economic status and type of schools. Journal of Social Sciences, 38(2), 159–165. https://doi.org/10.1080/09718923.2014.11893246

- Siddiqui, S., Kazmi, A. B., & Kamran, M. (2023). Teacher professional development for managing antisocial behaviors: A qualitative study to highlight status, limitations and challenges in educational institutions in the metropolis city of Pakistan. Frontiers in Education, 8. Article 177519. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2023.1177519

- Siddiqui, S., Kazmi, A. B., & Siddiqui, U. N. (2021). Internet addiction as a precursor for cyber and displaced aggression: A survey study on Pakistani youth. Addicta: The Turkish Journal on Addictions, 8(1), 73–80. https://doi.org/10.5152/ADDICTA.2021.20099

- Siddiqui, S., Schultze-Krumbholz, A. (2023). Bullying prevalence in Pakistan’s educational institutes: Preclusion to the framework for a teacher-led antibullying intervention. PLoS ONE, 18(4), e0284864. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0284864

- Siddiqui, S., Schultze-Krumbholz, A., & Kamran, M. (2023). Sohanjana antibullying intervention: Culturally and socially targeted intervention for teachers in Pakistan to take actions against bullying. European Journal of Educational Research, 12(3), 1523–1538. https://doi.org/10.12973/eu-jer.12.3.1523

- Smith, P. K. (2012). Cyberbullying and cyber aggression. In R. J. Shane, B. N. Amanda, J. M. Matthew, & J. F. Michael (Eds.), Handbook of school violence and school safety (pp. 111–121). Routledge.

- Springer, A. E., Selwyn, B. J., & Kelder, S. H. (2006). A descriptive study of youth risk behavior in urban and rural secondary school students in El Salvador. BMC International Health and Human Rights, 6(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-698X-6-3

- Strohmeier, D., Hoffmann, C., Schiller, E.-M., Stefanek, E., & Spiel, C. (2012). ViSC social competence program. New Directions for Youth Development, 133(133), 71–84. https://doi.org/10.1002/yd.20008

- Suleman, Q., Aslam, H. D., Ali, N., Hussain, I., & Ambreen, S. (2013). Techniques used by secondary school teachers in managing classroom disruptive behaviour of secondary school students in Karak District, Pakistan. International Journal of Learning and Development, 3(1), 236–256. https://doi.org/10.5296/ijld.v3i1.3403

- Swearer, S. M., & Espelage, D. L. (2004). Introduction: A social-ecological framework of bullying among youth. In Dorothy, L. E., & Swearer, S. M. (Eds.), Bullying in American schools (pp. 23–34). Routledge.

- Tappero, J. W., Cassell, C. H., Bunnell, R., Angulo, F. J., Craig, A., Pesik, N., Dahl, A. B., Ijaz, K., Jafari, H., Martin, R., & Global Health Security Science Group. (2017). US centers for disease control and prevention and its partners’ contributions to global health security. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 23(13), S5–S14. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2313.170946

- Ullah, M. H., Khan, M. N. U., Murtaza, A., & Din, M. N. U. (2011). Staff development needs in Pakistan higher education. Journal of College Teaching & Learning (TLC), 8(1), 19–24. https://doi.org/10.19030/tlc.v8i1.982

- Uz, R., & Bayraktar, M. (2019). Bullying toward teachers and classroom management skills. European Journal of Educational Research, 8(2), 647–657. https://doi.org/10.12973/eu-jer.8.2.647

- van der Zanden, P. J., Denessen, E. J., & Scholte, R. H. (2015). The effects of general interpersonal and bullying-specific teacher behaviors on pupils’ bullying behaviors at school. School Psychology International, 36(5), 467–481. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034315592754

- Van Geel, M., Vedder, P., & Tanilon, J. (2014). Relationship between peer victimization, cyberbullying, and suicide in children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatrics, 168(5), 435–442. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.4143

- Van Niejenhuis, C., Huitsing, G., & Veenstra, R. (2020). Working with parents to counteract bullying: A randomized controlled trial of an intervention to improve parent‐school cooperation. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 61(1), 117–131. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjop.12522

- van Verseveld, M. D., Fukkink, R. G., Fekkes, M., & Oostdam, R. J. (2019). Effects of antibullying programs on teachers’ interventions in bullying situations. A meta‐analysis. Psychology in the Schools, 56(9), 1522–1539. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22283

- Waasdorp, T. E., Fu, R., Perepezko, A. L., & Bradshaw, C. P. (2021). The role of bullying-related policies: Understanding how school staff respond to bullying situations. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 18(6), 880–895. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405629.2021.1889503

- Waasdorp, T. E., Pas, E. T., Zablotsky, B., & Bradshaw, C. P. Ten-year trends in bullying and related attitudes among 4th-to 12th-graders. (2017). Pediatrics, 139(6), e20162615. Article e20162615. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-2615

- Woodford, M. R., Han, Y., Craig, S., Lim, C., & Matney, M. M. (2014). Discrimination and mental health among sexual minority college students: The type and form of discrimination does matter. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health, 18(2), 142–163. https://doi.org/10.1080/19359705.2013.833882

- Zych, I., Ttofi, M. M., Llorent, V. J., Farrington, D. P., Ribeaud, D., & Eisner, M. P. (2020). A longitudinal study on stability and transitions among bullying roles. Child Development, 91(2), 527–545. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13195