Abstract

This study aims to investigate the influence of gamification on students’ engagement, learning effectiveness, and satisfaction in higher education, as well as the function of engagement and learning effectiveness in moderating the connection. Data were obtained quantitatively from 306 undergraduate and graduate students in Vietnam who participated in gamified lectures. The links between gamification, student engagement, learning effectiveness, and satisfaction were investigated using structural equation modeling. The results suggested that challenge and enjoyment directly influenced students’ engagement and satisfaction. Additionally, the presence of challenge directly affected learning effectiveness. Engagement and learning effectiveness served as mediators between gamification and students’ satisfaction. Educational institutions, instructors, and academics may use gamification to improve students’ engagement, satisfaction, and learning effectiveness, leading to more inspirational and successful learning experiences in higher education. This study provides significant insights for higher education stakeholders and encourages instructors and institutions to adopt creative teaching methodologies that meet the demands of current students. Adoption of gamification can result in more dynamic and engaging learning environments, which will boost students’ experiences and overall educational quality.

1. Introduction

Currently, traditional one-way teaching methods used in the field of education, also known as 1-way methods, have decreased students’ motivation to learn (Noreen & Rana, Citation2019; Putz et al., Citation2020). Previous studies have indicated that one-way teaching methods tend to focus only on the teacher or teaching content without stimulating the desire to learn among students. Boredom increases students’ dissatisfaction with the training program, teacher, and learning content, consequently affecting their academic performance (Noreen & Rana, Citation2019; Putz et al., Citation2020). Therefore, there is a need for teaching methods that promote students’ and teachers’ satisfaction and enhance students’ learning effectiveness.

An emerging learning method that can help achieve the desired learning outcomes is the gamification of learning (Wang et al., Citation2020; Zainuddin et al., Citation2020). Gamification is regarded as one of the top software trends. Although it is not always recognized, gamification is prevalent in our daily lives (Baptista & Oliveira, Citation2018). Gamification involves the creation of an environment that does not have games but integrates the aspects of games to improve user experience and create engagement (Aparicio et al., Citation2021). Games are essential to human culture and civilization because they boost motivation and connection (Bozkurt & Durak, Citation2018). Gamification has been widely studied and has become a new trend in many fields, such as electronic wallets (Yang et al., Citation2023), business (Elidjen et al., Citation2022), healthcare (Orji & Moffatt, Citation2018), workplaces (Passalacqua et al., Citation2020), or consumer behavior (Tobon et al., Citation2020). According to Cukurova et al. (Citation2020), the evaluation of new technology platforms, such as games, is crucial in the learning process.

Extensive research has explored the implications of gamification in academia (Hakak et al., Citation2019; Yu et al., Citation2021; Zainuddin et al., Citation2020). While many studies have evaluated learning performance and outcomes of incorporating gamification in educational settings (Bai et al., Citation2020; Hanus & Fox, Citation2015; Huang et al., Citation2020), several intriguing issues remain unresolved.

The existing literature has predominantly focused on gamification elements borrowed from specific gaming platforms, such as scores, badges, and leaderboards, which have been shown to affect learning performance and outcomes (Bai et al., Citation2020; Hanus & Fox, Citation2015; Huang et al., Citation2020). However, these studies have overlooked crucial game elements like competitiveness, enjoyment, and challenge, directly and indirectly influence learning effectiveness (Hanus & Fox, Citation2015; López & Tucker, Citation2018; Van Roy & Zaman, Citation2018).

Moreover, although some studies have examined learning performance (Hanus & Fox, Citation2015; López & Tucker, Citation2018) or learning outcomes (Van Roy & Zaman, Citation2018), they have not fully considered learning effectiveness. The inclusion of these elements can help develop a valuable tool for assessing the efficacy of learning technologies, such as online platforms or applications (Amin et al., Citation2022; Chang et al., Citation2021), and provide a comprehensive overview of students’ achievements.

Future research should delve into a more holistic understanding of game elements and learning effectiveness to to harness gamification’s potential in academia. This will enable us to unlock novel and innovative ways to enhance education through gamification, ultimately benefitting both educators and students. Within the context of technology-based education, several studies have examined the impact of technology on students’ satisfaction (Aparicio et al., Citation2019; Pérez-Pérez et al., Citation2020; Wirani et al., Citation2022). While investigating the educational environment with gamification, most studies have primarily focused on motivation (Hanus & Fox, Citation2015; Ortiz‐Rojas et al., Citation2019; Van Roy & Zaman, Citation2018).

Satisfaction and learning effectiveness (or academic performance) are concepts that have been studied a lot in research (Hazzam & Wilkins, Citation2023; Soesmanto et al., Citation2023; Wu et al., Citation2023). However, understanding the impact of learning effectiveness on student learning satisfaction is still very limited, especially in the context of gamification. The question is whether students feel satisfied because of the game or because learning effectiveness is actually improved. El-Sayad et al. (Citation2021) and Hu and Hui (Citation2012) proposed that when students perceive effective learning, they form positive evaluations and experience satisfaction with their learning. However, studies in gamified education have found that the simultaneous direct and indirect influences of gamification features on learning effectiveness are limited. Furthermore, little emphasis has been given to learning effectiveness and engagement as mediators in the association between gamification elements and satisfaction.

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has profoundly influenced several domains, including schooling (Oyedotun, Citation2020). Imran et al. (Citation2023) argue that the pandemic led to substantial changes in education, with an increased emphasis on technology-mediated learning. Owing to this shift, the field of education requires exploration in the post COVID-19 context. Notably, Vietnam had experienced periods of social distancing due to the pandemic, thereby prompting the evaluation of the use of gamification in classrooms before and during the COVID-19 outbreak (López & Tucker, Citation2018; Van Roy & Zaman, Citation2018; Wirani et al., Citation2022). Additionally, the implementation of technology, such as the adoption of e-learning, online surveys, and research, in Vietnamese education has become more prevalent post-pandemic. The use of online platforms for interaction, information exchange, and assignment submissions through learning management systems (LMS) has also increased. Therefore, understanding the impact of gamification elements on students’ satisfaction through learning effectiveness in this new context requires further investigation. Consequently, the following research questions should be addressed:

RQ1:

How do gamification elements, including competitiveness, challenge, and enjoyment, directly affect students’ learning effectiveness?

RQ2:

How do gamification elements, including competitiveness, challenge, and enjoyment, directly and indirectly affect students’ satisfaction?

RQ3:

What are the effects of gamification elements on students’ satisfaction via learning effectiveness and engagement?

This study explored the impact of gamification elements on students’ learning effectiveness, engagement, and satisfaction. Furthermore, it investigated the indirect effect of gamification on students’ satisfaction through engagement and learning effectiveness, especially in the context of post-COVID-19 in Vietnam.

2. Theoretical frameworks

2.1. Self-determination theory

The self-determination theory, proposed by Deci and Ryan (Citation1985), emphasizes intrinsic motivation and self-actualization. It identifies three key drivers of human motivation: autonomy, relatedness, and competence. When these factors are fulfilled, individuals are strongly motivated to pursue personal goals, leading to improved academic performance and satisfaction. Conversely, inadequate fulfillment of these elements reduces motivation and self-actualization, which affects learning efficiency and learner’s satisfaction. The present study applied this theory to explore the role of gamification elements in promoting learner autonomy, enhancing learning effectiveness, and creating higher student satisfaction in a gamified environment. Moreover, to attain the objectives of enhanced learning effectiveness and student satisfaction, it is imperative for students to establish connections with their peers through their proficiency and by engaging in challenging and competitive activities within gamified classrooms.

2.1.1. Gamification for students’ engagement: A framework

Based on Landers’s (Citation2014) theory of gamified learning, Rivera and Garden (Citation2021) have established a practical framework to analyze students’ involvement when gamification is used in the classroom. This paradigm explains how gamification affects students’ engagement and, consequently, their learning outcomes. The study created a gamification framework for increasing students’ engagement by combining the existing knowledge on their engagement and gamification. This approach enables educators to methodically build gamified learning experiences by carefully selecting appropriate game features that fit with the desired experiences of students and the subsequent consequences on their engagement. Although the primary focus is on learning outcomes, the gamification framework can potentially improve students’ happiness and progress in various educational environments and subject areas. The present study utilized the existing theory to complement and explain the context of gamification in the classroom, where gamified elements serve as factors that influence students’ learning effectiveness through engagement.

2.2. Hypotheses development

2.2.1. Satisfaction

Satisfaction is a significant aspect of a student’s experience concerning the acquisition and use of technology (Wirani et al., Citation2022). This encompasses a myriad of elements that contribute to the holistic satisfaction of students and assumes a substantial role in the evaluation of their academic performance and learning achievements (El-Sayad et al., Citation2021). Educational institutions regard students’ satisfaction as an important measure of a student’s entire academic experience and accomplishment (Rajabalee et al., Citation2020). Prioritizing students’ happiness has become essential for institutions in today’s competitive educational landscape as they seek to recruit and retain students (Santos et al., Citation2020). Several studies have investigated students’ happiness as an acquired component in the gamification process in the classroom (Sailer et al., Citation2017; Wirani et al., Citation2022; Xi & Hamari, Citation2019). According to the existing literature, educational gamification strives to increase students’ satisfaction by making learning interesting, engaging, and motivating by integrating game aspects and mechanics in the learning process. Understanding the elements influencing students’ happiness, such as the use of technology and gamification tactics, is critical for building successful and engaging learning experiences (Wirani et al., Citation2022). Educators and institutions can create supportive environments that foster motivation, engagement, and, ultimately, academic success by addressing and catering to students’ satisfaction levels.

2.2.2. Learning effectiveness

According to Panigrahi et al. (Citation2021), learning effectiveness refers to the desired knowledge, understanding, and skills that learners are expected to acquire and demonstrate upon completing a learning process. Panigrahi et al. (Citation2021) stated that it goes beyond the simple measurement of performance or outcomes and focuses on learners’ achievements and the extent to which they meet instructors’ expectations, such as grades. This concept is particularly relevant for evaluating the efficacy of learning technologies, such as online platforms or applications (Amin et al., Citation2022; Chang et al., Citation2021). Measuring learning effectiveness is essential in assessing the development of learning behavior, which encompasses multiple facets (Xia, Citation2022). Therefore, the adoption of comprehensive and appropriate technologies, methods, and tools is essential for facilitating a flexible and effective learning process (Matzavela & Alepis, Citation2021). By considering learning effectiveness, educators and instructional designers can evaluate the overall impact and success of educational technologies, thereby leading to continuous improvement and enhanced learning experiences for students.

Rajabalee et al. (Citation2020) investigated online learning and discovered that student satisfaction is an important measure of a student’s entire learning experience and accomplishment, which is reflected in the learning outcomes. It demonstrates a strong link between students’ learning effectiveness and satisfaction. El-Sayad et al. (Citation2021) and Hu and Hui (Citation2012) demonstrated the influence of students’ learning effectiveness on their learning satisfaction in the context of educational technology application. Consequently, we propose the following:

H1:

Learning effectiveness directly impacts satisfaction.

2.2.3. Engagement

Learning engagement is defined by Li et al. (Citation2023) as a combination of intentional and purposeful behaviors and responses. Hanaysha et al. (Citation2023) proposed the notion of “student engagement,” which quantifies the time and effort students devote in educational pursuits to contribute to their intended academic accomplishments. Furthermore, Aliabadi and Weisi (Citation2023) and Hanaysha et al. (Citation2023) define student involvement as the sum of students’ psychological, cognitive, emotional, and behavioral reactions to the learning process. This includes their participation in academic and social activities, both inside and outside of the classroom, with the goal of obtaining successful learning outcomes. Academic engagement refers to the level of effort invested by students to perform well and achieve their goals (Panigrahi et al., Citation2021). Research conducted by Leftheriotis et al. (Citation2017) explored the concept and impact of gamification. In their field study, students actively participated in an extracurricular activity using an interactive display application. The findings highlighted the positive effects of gamification in enhancing user engagement. This aligns with the perspective presented by Weintrop et al. (Citation2016) that emphasizes the importance of creating an ideal gaming environment that fosters user engagement. Additionally, Landers et al. (Citation2017) suggested competitiveness as a factor of gamification that increases engagement.

The higher the student’s learning engagement, the better their academic achievement (Oubibi et al., Citation2023). Leftheriotis et al. (Citation2017) also demonstrated a substantial link between students’ involvement and academic results. According to Panigrahi et al. (Citation2021), multidimensional involvement, such as behavioral engagement, emotional engagement, and cognitive engagement, has significantly affected academic performance. They found that all aspects of engagement have an impact on students’ learning effectiveness by improving their classroom participation, awareness, attitudes, and psychological well-being. Additionally, Rajabalee et al. (Citation2020) found a correlation between engagement in the classroom and student performance. In the context of technology, El-Sayad et al. (Citation2021) and Hu and Hui (Citation2012) demonstrated that students’ learning effectiveness is influenced by their learning engagement. Although several studies have been conducted in the context of gamification, they did not find the impact of engagement on learning performance (Hanus & Fox, Citation2015; Ortiz‐Rojas et al., Citation2019). Rivera and Garden (Citation2021) argued that students’ engagement affects their learning effectiveness in the context of gamification. However, the above studies only studied students’ performance and not learning effectiveness. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H2:

Engagement has a direct and positive impact on learning effectiveness.

2.2.4. Gamification and its elements

Among the several definitions available in the literature, we recognized gamification as the use of game-design features in non-gaming situations (Baptista & Oliveira, Citation2018). Gamification is an approach to increasing user engagement and happiness by incorporating game dynamics into non-game scenarios (Anunpattana et al., Citation2021). It has been widely used in various fields, including education (Hitchens & Tulloch, Citation2018; Laine & Lindberg, Citation2020; Surendeleg et al., Citation2014), health (Chen et al., Citation2014; Cotton & Patel, Citation2019), marketing (Hamari et al., Citation2018; Mitchell et al., Citation2020), and business (Deterding et al., Citation2011). Gamification holds the potential to enhance educational learning outcomes by offering immediate incentives as well as long-term educational advantages (Dicheva et al., Citation2017; Sanchez et al., Citation2020).Gamification differs from game-based learning and serious games in that it combines game aspects without changing the learning process into a full game (Rivera & Garden, Citation2021). We used a modified version of Landers’ definition of gamification in this study, which refers to the application of game qualities outside of a gaming setting to improve learning (Landers, Citation2014). Elements of gamification included in the present study were challenge, competitiveness, and enjoyment, all of which led to a more engaging and successful learning experience.

2.2.4.1. Enjoyment

Baptista and Oliveira (Citation2018) stated that gamification creates enjoyment. Enjoyment is a crucial aspect of gamification, defined as the positive emotion experienced by individuals when they surpass personal limits and accomplish new tasks (Zhang & Tsung, Citation2021). It is derived from the pleasure of using technology (Aparicio et al., Citation2019). The selection of an appropriate game platform enhances user engagement and enjoyment (Weintrop et al., Citation2016). Gamification should incorporate emotional energy to provide learners with a sense of enjoyment and motivation (Aparicio et al., Citation2019). It is often associated with a perception of enjoyment, which is recognized as a key element (Mitchell et al., Citation2020; Wirani et al., Citation2022).

2.2.4.2. Challenge

Challenges are a fundamental component of game mechanics that positively influence the “motion in mind” concept, as supported by a quantitative study on challenge-based gamification (Anunpattana et al., Citation2021). This approach allows precise examination of the elements that contribute to learning and yield specific outcomes (Anunpattana et al., Citation2021). Furthermore, research suggests that challenge design principles have a higher potential to engage a diverse range of players compared to other principles (Legaki et al., Citation2020). Leftheriotis et al. (Citation2017) and Rivera and Garden (Citation2021) stated that gamification in learning can incorporate challenges. Hence, in this study, we acknowledged challenge as a significant element of gamification in educational settings.

2.2.4.3. Competitiveness

Competitive students in educational settings are generally characterized as individuals who value and actively participate in competitive activities (Weissman et al., Citation2022). In gamified learning environments, the introduction of competitiveness creates a motivational atmosphere where individuals set goals to win and exert efforts to achieve them (Acquah & Katz, Citation2020; Landers et al., Citation2017). Landers et al. (Citation2017) highlighted that individuals with higher goal commitment tend to outperform others in competitive settings that incorporate leaderboards. Leftheriotis et al. (Citation2017) and Weintrop et al. (Citation2016) suggested that students compete with one another when game elements are incorporated into classroom activities, thereby demonstrating competitiveness to be an inherent factor in gamification.

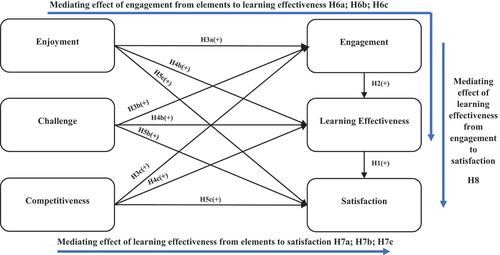

In the study on gamification factors and engagement, Leftheriotis et al. (Citation2017) discussed the influence of the gamification context on user engagement. They also emphasized the significance of game design in creating challenges and fostering competitiveness. Moreover, the level of enjoyment plays a crucial role in influencing user engagement in a gamified environment (Suh et al., Citation2018). Several studies on gamification in educational settings have highlighted the positive effects of gamification on students’ learning effectiveness and user satisfaction (Ortiz‐Rojas et al., Citation2019; Rivera & Garden, Citation2021; Wirani et al., Citation2022). Game elements, including competitiveness, challenges, and enjoyment, have been identified as integral components of gamification (Leftheriotis et al., Citation2017; Weintrop et al., Citation2016; Wirani et al., Citation2022). They directly affect user satisfaction and engagement, as verified by Landers’s research (Landers, Citation2014), and indirectly and directly influence students’ learning effectiveness (Rivera & Garden, Citation2021). Based on these findings, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H3a, H3b, H3c:

Enjoyment, challenge, and competitiveness have a direct and positive impact on user engagement.

H4a, H4b, H4c:

Enjoyment, challenge, and competitiveness have a direct and positive impact on learning effectiveness.

H5a, H5b, H5c:

Enjoyment, challenge, and competitiveness have a direct and positive impact on user satisfaction.

The study conducted by Rivera and Garden (Citation2021) and Landers (Citation2014) on gamification in the educational context highlighted the process from gamification factors to learning outcomes, which involves the mediating role of user engagement as attitudes. Rajabalee et al. (Citation2020) suggested that engagement, satisfaction, and learning performance are interrelated in the learning process. The process of learning, beginning from learning engagement to learning effectiveness and resulting in learning satisfaction, has been extensively explored in the context of technology-enhanced learning (El-Sayad et al., Citation2021; Hu & Hui, Citation2012). In the present study, we aimed to investigate the differential roles of mediation when examining the direct and indirect effects of gamification factors on students’ engagement, learning effectiveness, and satisfaction. Therefore, the following intermediate hypotheses are proposed:

H6a, H6b, H6c:

Enjoyment, challenge, and competitiveness indirectly affect learning effectiveness through engagement.

H7a, H7b, H7c:

Enjoyment, challenge, and competitiveness indirectly impact satisfaction through learning effectiveness.

H8:

Engagement indirectly impacts satisfaction through learning effectiveness.

A conceptual model diagram is presented in Figure .

3. Methodology

3.1. Research context

The global gamified learning market has grown significantly, with an estimated worth of around $11 billion in 2021, and it is projected to exceed $29.7 billion by the end of 2026, boasting a substantial CAGR of 21.9% (MarketsandMarkets, Citation2022).

This substantial growth underscores the heightened interest in gamification elements within educational practices. Gamification, which involves integrating game-design principles into non-game contexts, has gained prominence as an innovative pedagogical approach. It enhances student engagement and provides an interactive learning experience.

The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the adoption of gamified learning solutions as educators sought engaging tools for remote and hybrid learning. Consequently, understanding how gamification elements impact learning effectiveness and student satisfaction, especially in a post-COVID-19 landscape, has become crucial.

As the gamified learning market expands, research on the effects of elements such as competitiveness, challenge, and enjoyment is increasingly relevant. These studies aim to uncover how these elements enhance learning outcomes, engagement, and satisfaction. Insights gained from such research inform the design of more effective gamified educational strategies tailored to meet the evolving needs of modern learners.

3.2. Measurement

The first section of the questionnaire comprised items about the variables used in this study. Competitiveness (CO) and Satisfaction (SA) included three observed variables, while Enjoyment (ENJ) and Challenge (CH) included four observed variables, measured using three subscales from Wirani et al. (Citation2022). Learning Effectiveness (EP) included three subscales developed by Damnjanovic et al. (Citation2015). The five subscales of Engagement (ENG) were developed by Kamboj et al. (Citation2020). All items were rated on a five-point Likert scale ranging from (1) strongly disagree to (5) strongly agree.

Therefore, this study measured 26 observed variables under eight distinct subscales. Demographic variables were collected at the end of the questionnaire. The five-point Likert scale was used to assess participants’ level of agreement or disagreement with the observable factors. Competitiveness, satisfaction, enjoyment, challenge, learning effectiveness, and engagement were the latent variables in this study.

3.3. Sampling and data collection

The hypotheses were tested using an accessible non-probability sample of students who had experienced applied game-based classes. An experimental study was conducted at universities using online surveys. The questionnaire was designed using Google Forms and sent to survey participants through social networking sites, including Zalo and Facebook. A questionnaire was developed for the survey using structures and overview terms from the literature. A back-translation approach was employed accurately describe the questionnaire in the target language (Tyupa, Citation2011). A proficient native speaker has meticulously examined the ultimate iteration of the survey to mitigate the potential for response bias and provide precise responses to the inquiries The questionnaire included content in Vietnamese along with English to ensure accurate understanding. Participants were selected from two sources: Students, postgraduate students, and former students of universities in Ho Chi Minh City and Hanoi, the two largest and most university-concentrated cities in Vietnam. University students, postgraduates, and former students at universities were considered appropriate participants for this study because they were allowed to use technology for learning, which was limited to primary and secondary school students due to education policies in Vietnam. Moreover, this group of participants could perceive and evaluate the application of games to learning. To counteract non-response bias, the participants were informed about the study’s aims and the confidentiality of their data. A pilot test with 50 participants was undertaken before the final survey to verify the structure and validity of the survey. Google Forms was used to conduct the survey. First, we introduced game-based teaching in the classroom along with examples of educational electronic games such as Kahoot!, Slido, and Quizziz. Then, participants were asked to confirm their participation in game-based classes by answering whether they had participated in game-based classes. Those who answered “yes” continued to answer the next questions, while those who answered “no” were asked to withdraw from the survey. Of the 379 survey participants, 306 (80.74%) had participated in game-based teaching in the classroom. Table provides detailed information about the characteristics of the participants.

Table 1. Demographic profile of respondents

3.4. Measurement model and structural model assessment

SEM allows researchers to model and estimate complicated interactions between several dependent and independent variables simultaneously. Furthermore, SEM considers measurement errors in observed variables. Therefore, SEM was used in this study. Statistical analysis results were used to evaluate measurement and structural models and discover theoretical linkages. The measurement model was initially validated using reliable, convergent, and discriminant validation. SEM was used to evaluate the structural model and predicted connections. We established the measurement’s reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity. Structural paths and their significance were examined to accept or reject the proposed hypotheses. SEM facilitated a holistic understanding of interactions and interdependencies between theoretical constructs. In summary, SEM proved invaluable for analyzing complex associations among latent variables in this study. Furthermore, this study used VAF (Mediation analysis-variance accounts for) to explain the mediating role suggested by Preacher and Hayes (Citation2008).

4. Results

4.1. Assessment of multicollinearity and common method bias

The issue of potential multicollinearity and common method bias (CMB) was analyzed in this study using the VIF technique. A critical problem is indicated when a formative indicator’s VIF value exceeds 5; lower values can also indicate problems. Ideally, VIF values should be roughly equivalent to or less than 3 for optimal results (Hair et al., Citation2019). However, all structures had VIF values ranging from 1.605–3.066, confirming the model’s lack of multicollinearity and CMB issues. The use of cross-sectional data often leads to uneven relationships between variables as it tends to induce notable methodological discrepancies that can overshadow the precision of the study outcomes (Fuller et al., Citation2016). Researchers typically adopt Harman’s single-factor test as an exploratory technique for measuring common method bias by examining intercorrelations between items representing diverse constructs under investigation (Podsakoff et al., Citation2003). Analysis of a single-factor structure indicates that no one factor explains most variance; only about 48.702% or less than half is explained by the first factor examined in this analysis (Podsakoff et al., Citation2003). Furthermore, the absence of shared methodological prejudices was identified in the data. Consequently, no common biases were discovered in the present study.

4.2. Assessment of the measurement model

The following approaches were used to evaluate the measurement model. Initially, Cronbach’s alpha was used to assess the internal consistency of each construct’s elements shown in Table . The minimal threshold for Cronbach’s coefficients was 0.6 (Hair et al., Citation2019), while the coefficients in this study varied from 0.792–0.908. The build reliability was then measured using composite reliability, with a minimum criterion of 0.6 (Hair et al., Citation2019). Table shows that in this study, construct reliability scores varied from 0.800–0.910. Convergent validity was determined using factor loadings and the average variance extracted (AVE), with a minimum criterion of 0.7 for outer loadings (Hair et al., Citation2014). Table also shows the outer loading values varied from 0.743–0.906. The AVE was used to evaluate the discriminant validity of the measures, with a minimum threshold of 0.5 (Hock et al., Citation2010). The AVE values varied from 0.642–0.789, above the 0.5 threshold (Hair et al., Citation2010). Furthermore, in Table , the square root of a construct’s AVE should be bigger than its bivariate correlation with other constructs in the model to establish discriminant validity (Hair et al., Citation2010). The AVE’s square roots (diagonal parts in bold) varied from 0.801–0.889. These results showed that the correlation of each variable was less than the square root of the AVE, and the indicators for each variable had appropriate discriminant validity.

Table 2. Constructs with items and reliability and validity

Table 3. Results of test for discriminant validity

4.3. Assessment of the structural model

Considering the model’s complexity and the need to examine the connections between the elements, the SEM method was employed using the maximum likelihood approach. The following were the findings of the testing model: SRMR = 0.058 and Chi2 = 733.333. According to Hair et al. (Citation2010), all model fit indices were above the required values, suggesting that the measurement model was suitable for the obtained data.

We used the structural equation model to analyze the structural model and describe the link between the hypotheses. We used the coefficient of determination (R2) and cross-intercept of the retention difference (Q2) by bootstrapping for the sampling test to evaluate the structural model (Hair et al., Citation2010). R2 revealed that three dependent variables, including engagement, learning effectiveness, and satisfaction, were explained with rates of 0.495, 0.501, and 0.602, respectively, in this study. The Q2 value was then calculated using the blindfolding command in the next step. Q2 results were 0.481, 0.36, and 0.494 for engagement, learning effectiveness, and satisfaction, respectively.

5. Conclusion, discussion and managerial implications

5.1. Conclusion

In conclusion, the findings of this study shed light on the intricate relationship between gamification elements, specifically competitiveness, challenge, and enjoyment, and their impact on students’ learning effectiveness, satisfaction, and engagement.

Regarding RQ1, competitiveness and enjoyment were not found to have a direct effect on learning effectiveness. However, challenge emerged as a significant factor positively influencing learning effectiveness. Students appeared to benefit from gamified learning environments that presented them with challenging tasks and activities.

For RQ2, competitiveness was observed not to have a direct or indirect effect on satisfaction. In contrast, enjoyment and challenge were shown to exert a direct influence on both engagement and satisfaction, highlighting its role in enhancing students’ overall experience and contentment with gamified learning.

Finally, for RQ3, it was revealed that challenge had a positive impact not only on learning effectiveness but also on satisfaction and engagement. This suggests that when students are presented with challenging tasks in gamified settings, it contributes to not only their academic achievements but also their overall satisfaction with the learning experience emphasizing the importance of creating challenge and engaging gamified learning environments to enhance students’ satisfaction levels. Furthermore, enjoyment was not found to indirectly affect satisfaction through its influence on engagement and learning effectiveness.

In summary, competitiveness may not directly impact learning effectiveness or satisfaction, but challenge and enjoyment play significant roles in shaping students’ learning outcomes and overall satisfaction within gamified educational contexts. Moreover, challenge also contributes to increased engagement, highlighting its multifaceted positive impact on the learning process. These insights can inform the design and implementation of gamified educational strategies to optimize students’ learning experiences.

5.2. Discussion

Technology has become significant in improving the quality of education and training (Giannakos et al., Citation2014; Yazdani et al., Citation2023). Notably, gamification has received considerable attention as a tool for shaping the educational environment (Rivera & Garden, Citation2021; Wirani et al., Citation2022). The present study used a survey to investigate the effects and implications of gamified elements, including CH, ENJ, and CO on ENG, SA, and EP as well as their mediating functions.

The findings shown in Table and Figure suggest that, of the gamification elements, CO had no direct effect on ENG (p = 0.381), SA (p = 0.358), or EP (p = 0.394). ENJ did not have a direct impact on EP (p = 0.309), but it directly influenced SA (β = 0.369) and ENG (β = 0.373). CH directly influenced EP (β = 0.290), SA (β = 0.199), and ENG (β = 0.435). In the context of gamification, this study demonstrated that learning effectiveness was not improved when the games generated competitiveness and enjoyment, but it improved when they presented challenges. Additionally, learner satisfaction is significantly enhanced when the gamified classroom context generates more enjoyment than challenges. However, this study showed that engagement was derived more from challenges than enjoyment in the gamified classroom context. Furthermore, it confirms that ENG had a direct and substantial influence on EP (β = 0.495), which had a direct and significant impact on SA (β = 0.389).

Table 4. Hypothesis testing and intermediate evaluation

The test of mediation roles revealed that EP acted as a partial mediating factor in the impact of ENG (VIF = 49.94%) and CH (VIF = 33%) on satisfaction. Additionally, ENG acted as a partial mediating factor in the impact of ENJ (VIF = 61%) and CH (VIF = 43.57%) on EP (Hair et al., Citation2019). This indicates that part of the influence of CH and ENG on SA depended on EP, and part of the influence of ENJ and CH on EP depended on ENG (Hair et al., Citation2019).

5.3. Implications

5.3.1. Theoretical implications

The COVID-19 pandemic had a tremendous impact on schooling (Oyedotun, Citation2020). According to Imran et al. (Citation2023), the pandemic resulted in considerable changes in schooling, with a stronger emphasis on technology-mediated learning. This transition mandates research in the field of education in the post-COVID-19 era. During the COVID-19 pandemic, social distancing tactics in Vietnam led to assessments of gamification in schools before and during the pandemic (López & Tucker, Citation2018; Van Roy & Zaman, Citation2018; Wirani et al., Citation2022). Furthermore, since the pandemic, there has been a boom in e-learning, online surveys, and research in Vietnamese education. The usage of online platforms for engagement, knowledge sharing, and assignment submissions through LMS has also increased significantly.

Several studies have investigated the influence of technology on education (Aparicio et al., Citation2019; Pérez-Pérez et al., Citation2020; Wirani et al., Citation2022). Motivation has been the primary focus of these studies in the educational gamification environment (Hanus & Fox, Citation2015; Ortiz‐Rojas et al., Citation2019; Van Roy & Zaman, Citation2018). Students’ knowledge of the efficacy of their learning and favorable assessments contribute to their satisfaction (El-Sayad et al., Citation2021; Hu & Hui, Citation2012). Few studies, however, have examined the influence of gamification elements on students’ learning effectiveness and engagement (Ortiz-Rojas et al., Citation2019). The VAF method’s usefulness and effects in educational gamification are yet to be completely investigated. The current study furnishes a more comprehensive perspective on the direct and indirect effects of gamification elements on students’ learning effectiveness, engagement, and satisfaction in the post-COVID-19 context in Vietnam.

5.3.2. Managerial implications

Assessing learning effectiveness is necessary considering the impact of technology on education (Amin et al., Citation2022; Chang et al., Citation2021; Xia, Citation2022). Educational institutions regard students’ satisfaction as an important measure of a student’s entire academic experience and accomplishment (Rajabalee et al., Citation2020). A few studies on gamification in educational settings have highlighted the positive effects of gamification on students’ learning effectiveness, engagement, and satisfaction (Leftheriotis et al., Citation2017; Ortiz‐Rojas et al., Citation2019; Rivera & Garden, Citation2021; Wirani et al., Citation2022). However, there is very little research that clearly connects game elements to satisfaction through learning effectiveness and engagement. Furthermore, the results of this study also have differences leading to the following management implications:

Importance of Challenges: This study emphasized the significance of incorporating challenges in gamified learning environments. Meaningful and stimulating challenges positively impact learning effectiveness, satisfaction, and engagement. Educators should design educational games that provide challenging experiences to enhance learning.

Role of Enjoyment: Enjoyment directly affects satisfaction and engagement. Creating an enjoyable learning environment contributes to higher levels of learner satisfaction and engagement. Educators should focus on incorporating elements that promote enjoyment and create a positive learning experience.

Competitiveness: This study found no direct impact of competitiveness on satisfaction, learning effectiveness, and engagement. Educators should carefully consider the role of competition in gamified learning environments. While some learners may thrive in competitive settings, it is essential to balance competition with other factors that enhance learners’ satisfaction.

Engagement: This study highlighted the crucial role of engagement in achieving learning effectiveness in a gamified context. Engagement was a significant mediator between the creation of challenges and learners’ enjoyment in a gamified classroom. The role of engagement should be observed and prioritized when implementing specific games in the classroom.

Learning Effectiveness: Similar to engagement, learning effectiveness played both a direct and significant intermediary role in learner satisfaction within a gamified context. The study demonstrated that achieving good learning effectiveness generated learner satisfaction in a gamified environment. Furthermore, learning effectiveness was attained when games created challenging experiences in the classroom.

Adjusting Gamification Elements: The results emphasized the importance of customizing gamification elements to align with specific learning goals, contexts, and learner profiles. Organizations and educators should tailor gamification strategies to meet the individual needs and preferences of learners and program objectives.

Therefore, this study provides valuable insights into the impact of gamification elements on learning effectiveness and learner satisfaction. By understanding these implications, educators can make informed decisions when integrating gamification into their teaching and training practices, thereby ultimately enhancing learners’ learning experience, satisfaction, and outcomes.

6. Limitations of the study

This study still has some limitations in terms of sample size, the objective impact of external factors, limitations in mediating factors when evaluating the impact of game elements on satisfaction, and lack of control group, specifically as follows:

Sample Size and Generalization: The present study included a specific sample of Vietnamese learners, and the findings may not be applicable to other groups or educational situations. A larger and more diverse sample would offer a more complete picture of the role of gamification elements in influencing students’ learning effectiveness.

External Factors: This study did not consider external factors that might impact gamification success, such as past gaming experience, individual learning styles, or instructional design quality. These variables have the potential to confound the link between elements of gamification and learning outcomes.

Limitations of Gamification Elements and Intermediate Factors: This study focused on a specific set of gamification elements, namely challenges, enjoyment, and competition. Other related factors, such as rewards, feedback, or social interaction, were not investigated. The inclusion of a broader range of gamification elements would yield a more comprehensive understanding of their impact on learning effectiveness. Additionally, intermediate factors, such as intrinsic motivation and extrinsic motivation in the research of Ortiz‐Rojas et al. (Citation2019) and Hanus and Fox (Citation2015), need to be considered when applying gamification in education.

Lack of a Control Group: This study did not include a control group without gamification experience. A comparison with traditional teaching methods would provide a better evaluation of the unique and effective contributions of gamification in enhancing learning outcomes.

Self-selection Bias: The participants in the study may have self-selected to engage in gamified learning activities, leading to potential inherent biases. Learners who are already motivated or have an interest in gamification methods may have participated and potentially influenced the outcomes.

These limitations should be considered when interpreting the findings. Future research should address these limitations and further explore the impact of gamification in educational environments./.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Acquah, E. O., & Katz, H. T. (2020). Digital game-based L2 learning outcomes for primary through high-school students: A systematic literature review. Computers & Education, 143, 103667. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2019.103667

- Aliabadi, R. B., & Weisi, H. (2023). Teachers’ strategies to promote learners’ engagement: Teachers’ talk in perspective. International Journal of Educational Research Open, 5, 100262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedro.2023.100262

- Amin, J., Sharif, M., Gul, N., Kadry, S., & Chakraborty, C. (2022). Quantum machine learning architecture for COVID-19 classification based on synthetic data generation using conditional adversarial neural network. Cognitive Computation, 14(5), 1677–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12559-021-09926-6

- Anunpattana, P., Khalid, M. N. A., Iida, H., & Inchamnan, W. (2021). Capturing potential impact of challenge-based gamification on gamified quizzing in the classroom. Heliyon, 7(12), e08637. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e08637

- Aparicio, G., Iturralde, T., & Maseda, A. (2021). A holistic bibliometric overview of the student engagement research field. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 45(4), 540–557. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2020.1795092

- Aparicio, M., Oliveira, T., Bacao, F., & Painho, M. (2019). Gamification: A key determinant of massive open online course (MOOC) success. Information & Management, 56(1), 39–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2018.06.003

- Bai, S., Hew, K. F., & Huang, B. (2020). Does gamification improve student learning outcome? Evidence from a meta-analysis and synthesis of qualitative data in educational contexts. Educational Research Review, 30, 100322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2020.100322

- Baptista, G., & Oliveira, T. (2018). Gamification and serious games: A literature meta-analysis and integrative model. Computers in Human Behavior, 92, 306–315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.11.030

- Bozkurt, A., & Durak, G. (2018). A systematic review of gamification research: In pursuit of homo ludens. International Journal of Game-Based Learning (IJGBL), 8(3), 15–33. https://doi.org/10.4018/IJGBL.2018070102

- Chang, J. Y. F., Wang, L. H., Lin, T. C., Cheng, F. C., & Chiang, C. P. (2021). Comparison of learning effectiveness between physical classroom and online learning for dental education during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Dental Sciences, 16(4), 1281–1289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jds.2021.07.016

- Chen, F. P., Chang, C. M., Hwang, S. J., Chen, Y. C., & Chen, F. J. (2014). Chinese herbal prescriptions for osteoarthritis in Taiwan: Analysis of national health insurance dataset. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 14(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6882-14-91

- Cotton, V., & Patel, M. S. (2019). Gamification use and design in popular health and fitness mobile applications. American Journal of Health Promotion, 33(3), 448–451. https://doi.org/10.1177/0890117118790394

- Cukurova, M., Zhou, Q., Spikol, D., & Landolfi, L. (2020) Modelling collaborative problem-solving competence with transparent learning analytics: Is video data enough? LAK '20. In C. Rensing & H. Drachsler (Eds.), Proceedings of the Tenth International Conference on Learning Analytics & Knowledge (pp. 270–275). Association for Computing Machinery (ACM).

- Damnjanovic, V., Jednak, S., & Mijatovic, I. (2015). Factors affecting the effectiveness and use of Moodle: Students’ perception. Interactive Learning Environments, 23(4), 496–514. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2013.789062

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). The general causality orientations scale: Self-determination in personality. Journal of Research in Personality, 19(2), 109–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/0092-6566(85)90023-6

- Deterding, S., Sicart, M., Nacke, L., O’Hara, K., & Dixon, D. (2011). Gamification. using game-design elements in non-gaming contexts. In CHI’11 extended abstracts on human factors in computing systems (pp. 2425–2428).

- Dicheva, D., Irwin, K., & Dichev, C. (2017). OneUp learning: A course gamification platform. Games and Learning Alliance: 6th International Conference, GALA 2017, Lisbon, Portugal, December 5–7, 2017, Proceedings 6 (pp. 148–158). Springer International Publishing.

- Elidjen, E., Pertiwi, A., Mursitama, T. N., & Beng, J. T. (2022). How potential and realized absorptive capacity increased ability to innovate: The moderating role of structural ambidexterity. VINE Journal of Information and Knowledge Management Systems, (ahead-of-print). https://doi.org/10.1108/VJIKMS-12-2021-0298

- El-Sayad, G., Md Saad, N. H., & Thurasamy, R. (2021). How higher education students in Egypt perceived online learning engagement and satisfaction during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Computers in Education, 8(4), 527–550. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40692-021-00191-y

- Fuller, C. M., Simmering, M. J., Atinc, G., Atinc, Y., & Babin, B. J. (2016). Common methods variance detection in business research. Journal of Business Research, 69(8), 3192–3198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.12.008

- Giannakos, M. N., Jones, D., Crompton, H., & Chrisochoides, N. (2014). Designing playful games and applications to Support Science centers learning activities. Universal Access in Human-Computer Interaction. Universal Access to Information and Knowledge: 8th International Conference, UAHCI 2014, Held as Part of HCI International 2014, Heraklion, Crete, Greece, June 22-27, 2014, Proceedings, Part II 8 (pp. 561–570). Springer International Publishing.

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2014). Multivariate Data Analysis (7th ed.). Pearson Education.

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203

- Hakak, S., Noor, N. F. M., Ayub, M. N., Affal, H., Hussin, N., Ahmed, E., & Imran, M. (2019). Cloud-assisted gamification for education and learning–recent advances and challenges. Computers & Electrical Engineering, 74, 22–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compeleceng.2019.01.002

- Hamari, J., Hassan, L., & Dias, A. (2018). Gamification, quantified-self or social networking? Matching users’ goals with motivational technology. User Modeling and User-Adapted Interaction, 28(1), 35–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11257-018-9200-2

- Hanaysha, J. R., Shriedeh, F. B., & In’airat, M. (2023). Impact of classroom environment, teacher competency, information and communication technology resources, and university facilities on student engagement and academic performance. International Journal of Information Management Data Insights, 3(2), 100188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jjimei.2023.100188

- Hanus, M. D., & Fox, J. (2015). Assessing the effects of gamification in the classroom: A longitudinal study on intrinsic motivation, social comparison, satisfaction, effort, and academic performance. Computers & Education, 80, 152–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2014.08.019

- Hazzam, J., & Wilkins, S. (2023). The influences of lecturer charismatic leadership and technology use on student online engagement, learning performance, and satisfaction. Computers & Education, 200, 104809. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2023.104809

- Hitchens, M., & Tulloch, R. (2018). A gamification design for the classroom. Interactive Technology & Smart Education, 15(1), 28–45. https://doi.org/10.1108/ITSE-05-2017-0028

- Hock, C., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2010). Management of multi-purpose stadiums: Importance and performance measurement of service interfaces. International Journal of Services Technology and Management, 14(2–3), 188–207.

- Huang, R., Ritzhaupt, A. D., Sommer, M., Zhu, J., Stephen, A., Valle, N., & Li, J. (2020). The impact of gamification in educational settings on student learning outcomes: A meta-analysis. Educational Technology Research & Development, 68(4), 1875–1901. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-020-09807-z

- Hu, P. J. H., & Hui, W. (2012). Examining the role of learning engagement in technology-mediated learning and its effects on learning effectiveness and satisfaction. Decision Support Systems, 53(4), 782–792. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dss.2012.05.014

- Imran, R., Fatima, A., Salem, I. E., & Allil, K. (2023). Teaching and learning delivery modes in higher education: Looking back to move forward post-COVID-19 era. The International Journal of Management Education, 21(2), 100805. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2023.100805

- Kamboj, S., Rana, S., & Drave, V. A. (2020). Factors driving consumer engagement and intentions with gamification of mobile apps. Journal of Electronic Commerce in Organizations (JECO), 18(2), 17–35. https://doi.org/10.4018/JECO.2020040102

- Laine, T. H., & Lindberg, R. S. (2020). Designing engaging games for education: A systematic literature review on game motivators and design principles. IEEE Transactions on Learning Technologies, 13(4), 804–821. https://doi.org/10.1109/TLT.2020.3018503

- Landers, R. N. (2014). Developing a theory of gamified learning: Linking serious games and gamification of learning. Simulation & Gaming, 45(6), 752–768. https://doi.org/10.1177/1046878114563660

- Landers, R. N., Bauer, K. N., & Callan, R. C. (2017). Gamification of task performance with leaderboards: A goal setting experiment. Computers in Human Behavior, 71, 508–515. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.08.008

- Leftheriotis, I., Giannakos, M. N., & Jaccheri, L. (2017). Gamifying informal learning activities using interactive displays: An empirical investigation of students’ learning and engagement. Smart Learning Environments, 4(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40561-017-0041-y

- Legaki, N. Z., Xi, N., Hamari, J., Karpouzis, K., & Assimakopoulos, V. (2020). The effect of challenge-based gamification on learning: An experiment in the context of statistics education. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 144, 102496. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhcs.2020.102496

- Li, L., Zhang, R., & Piper, A. M. (2023). Predictors of student engagement and perceived learning in emergency online education amidst COVID-19: A community of inquiry perspective. Computers in Human Behavior Reports, 12, 100326. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chbr.2023.100326

- López, C., & Tucker, C. (2018). Toward personalized adaptive gamification: A machine learning model for predicting performance. IEEE Transactions on Games, 12(2), 155–168. https://doi.org/10.1109/TG.2018.2883661

- MarketsandMarkets. (2022). Gamification market by component, organization size, application (marketing, sales, HR, Support, and development), deployment mode, vertical (retail, banking, government, healthcare, education, travel and hospitality), and region - global forecast to 2026.

- Matzavela, V., & Alepis, E. (2021). M-learning in the COVID-19 era: Physical vs digital class. Education and Information Technologies, 26(6), 7183–7203. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-021-10572-6

- Mitchell, R., Schuster, L., & Jin, H. S. (2020). Gamification and the impact of extrinsic motivation on needs satisfaction: Making work fun? Journal of Business Research, 106, 323–330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.11.022

- Noreen, R., & Rana, A. M. K. (2019). Activity-based teaching versus traditional method of teaching in mathematics at elementary level. Bulletin of Education and Research, 41(2), 145–159.

- Orji, R., & Moffatt, K. (2018). Persuasive technology for health and wellness: State-of-the-art and emerging trends. Health Informatics Journal, 24(1), 66–91. https://doi.org/10.1177/1460458216650979

- Ortiz‐Rojas, M., Chiluiza, K., & Valcke, M. (2019). Gamification through leaderboards: An empirical study in engineering education. Computer Applications in Engineering Education, 27(4), 777–788. https://doi.org/10.1002/cae.12116

- Oubibi, M., Chen, G., Fute, A., & Zhou, Y. (2023). The effect of overall parental satisfaction on Chinese students’ learning engagement: Role of student anxiety and educational implications. Heliyon, 9(3). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e12149

- Oyedotun, T. D. (2020). Sudden change of pedagogy in education driven by COVID-19: Perspectives and evaluation from a developing country. Research in Globalization, 2, 100029. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resglo.2020.100029

- Panigrahi, R., Srivastava, P. R., & Panigrahi, P. K. (2021). Effectiveness of e-learning: The mediating role of student engagement on perceived learning effectiveness. Information Technology & People, 34(7), 1840–1862. https://doi.org/10.1108/ITP-07-2019-0380

- Passalacqua, M., Léger, P. M., Nacke, L. E., Fredette, M., Labonté-Lemoyne, É., Lin, X., & Sénécal, S. (2020). Playing in the backstore: Interface gamification increases warehousing workforce engagement. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 120(7), 1309–1330. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMDS-08-2019-0458

- Pérez-Pérez, M., Serrano-Bedia, A. M., & García-Piqueres, G. (2020). An analysis of factors affecting students perceptions of learning outcomes with Moodle. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 44(8), 1114–1129. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2019.1664730

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

- Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40(3), 879–891. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.40.3.879

- Putz, L. M., Hofbauer, F., & Treiblmaier, H. (2020). Can gamification help to improve education? Findings from a longitudinal study. Computers in Human Behavior, 110, 106392. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106392

- Rajabalee, B. Y., Santally, M. I., & Rennie, F. (2020). A study of the relationship between students’ engagement and their academic performances in an eLearning environment. E-Learning & Digital Media, 17(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/2042753019882567

- Rivera, E. S., & Garden, C. L. P. (2021). Gamification for student engagement: A framework. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 45(7), 999–1012. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2021.1875201

- Sailer, M., Hense, J. U., Mayr, S. K., & Mandl, H. (2017). How gamification motivates: An experimental study of the effects of specific game design elements on psychological need satisfaction. Computers in Human Behavior, 69, 371–380. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.12.033

- Sanchez, D. R., Langer, M., & Kaur, R. (2020). Gamification in the classroom: Examining the impact of gamified quizzes on student learning. Computers & Education, 144, 103666. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2019.103666

- Santos, G., Marques, C. S., Justino, E., & Mendes, L. (2020). Understanding social responsibility’s influence on service quality and student satisfaction in higher education. Journal of Cleaner Production, 256, 120597. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.120597

- Soesmanto, T., Vu, X. B. B., & Kariyawasam, K. (2023). Evaluation of the mixed-mode teaching design upon students’ learning satisfaction and academic performance in an introductory economics course. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 77, 101253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2023.101253

- Suh, A., Wagner, C., & Liu, L. (2018). Enhancing user engagement through gamification. Journal of Computer Information Systems, 58(3), 204–213. https://doi.org/10.1080/08874417.2016.1229143

- Surendeleg, G., Murwa, V., Yun, H. K., & Kim, Y. S. (2014). The role of gamification in education–a literature review. Contemporary Engineering Sciences, 7(29), 1609–1616. https://doi.org/10.12988/ces.2014.411217

- Tobon, S., Ruiz-Alba, J. L., & García-Madariaga, J. (2020). Gamification and online consumer decisions: Is the game over? Decision Support Systems, 128, 113167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dss.2019.113167

- Tyupa, S. (2011). A theoretical framework for back-translation as a quality assessment tool. New Voices in Translation Studies, 7(1), 35–46.

- Van Roy, R., & Zaman, B. (2018). Need-supporting gamification in education: An assessment of motivational effects over time. Computers & Education, 127, 283–297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2018.08.018

- Wang, P., Zheng, X., Li, J., & Zhu, B. (2020). Prediction of epidemic trends in COVID-19 with logistic model and machine learning technics. Chaos, Solitons & Fractals, 139, 110058. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chaos.2020.110058

- Weintrop, D., Beheshti, E., Horn, M., Orton, K., Jona, K., Trouille, L., & Wilensky, U. (2016). Defining computational thinking for mathematics and science classrooms. Journal of Science Education and Technology, 25(1), 127–147. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10956-015-9581-5

- Weissman, D. L., Elliot, A. J., & Sommet, N. (2022). Dispositional predictors of perceived academic competitiveness: Evidence from multiple countries. Personality and Individual Differences, 198, 111801. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2022.111801

- Wirani, Y., Nabarian, T., & Romadhon, M. S. (2022). Evaluation of continued use on Kahoot! as a gamification-based learning platform from the perspective of Indonesia students. Procedia Computer Science, 197, 545–556. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2021.12.172

- Wu, Y., Xu, X., Xue, J., & Hu, P. (2023). A cross-group comparison study of the effect of interaction on satisfaction in online learning: The parallel mediating role of academic emotions and self-regulated learning. Computers & Education, 199, 104776. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2023.104776

- Xia, X. (2022). Diversion inference model of learning effectiveness supported by differential evolution strategy. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 3, 100071. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeai.2022.100071

- Xi, N., & Hamari, J. (2019). Does gamification satisfy needs? A study on the relationship between gamification features and intrinsic need satisfaction. International Journal of Information Management, 46, 210–221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2018.12.002

- Yang, X., Yang, J., Hou, Y., Li, S., & Sun, S. (2023). Gamification of mobile wallet as an unconventional innovation for promoting Fintech: An fsQCA approach. Journal of Business Research, 155, 113406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2022.113406

- Yazdani, M., Pamucar, D., Erdmann, A., & Toro-Dupouy, L. (2023). Resilient sustainable investment in digital education technology: A stakeholder-centric decision support model under uncertainty. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 188, 122282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2022.122282

- Yu, Z., Gao, M., & Wang, L. (2021). The effect of educational games on learning outcomes, student motivation, engagement and satisfaction. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 59(3), 522–546. https://doi.org/10.1177/0735633120969214

- Zainuddin, Z., Shujahat, M., Haruna, H., & Chu, S. K. W. (2020). The role of gamified e-quizzes on student learning and engagement: An interactive gamification solution for a formative assessment system. Computers & Education, 145, 103729. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2019.103729

- Zhang, L., & Tsung, L. (2021). Learning Chinese as a second language in China: Positive emotions and enjoyment. System, 96, 102410. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2020.102410