Abstract

Studies on indigenous education have become popular in recent years. In Indonesia, indigenous education studies are carried out to rediscover a distinctive educational identity. This study aims to describe the indigenous education of children in Java during the Dutch colonial period through a study of children’s literary novels in Vorstenlanden in 1937. This is a qualitative study. The novel under study is titled Bocah Mangkunegaran which is a children’s literary novel by a well-known author at that time, namely Jasawidagda. This novel was chosen because of its journalistic style which combines historical facts with fiction. This novel records events in the colonial era from the point of view of indigenous children who are educated with indigenous education. The results of the study show that indigenous education is one of the efforts of the Javanese people to resist colonialism, western education models, and priyayi social class. Indigenous education for Javanese children emphasizes feeling, soul and character, not just logic and reason. Indigenous education covers: 1) Economic education for non-priyayi people; 2) Character education and schooling for Javanese children; 3) Education on Javanese religiosity (kejawen), mythology, and puppets; 4) Regional education; and 5) Scouting education (padvinder).

1. Introduction

This study highlights the significant role of children’s literary novels within a more contextually relevant educational framework. Particularly, a more in-depth investigation into indigenous educational practices within a children’s literary novel published during the colonial period in Java, Indonesia could serve as a link between imported modern curricula and traditional educational methods. The novel offers valuable insights into indigenous educational techniques, promoting holistic learning by integrating cultural elements, local knowledge, and pertinent values. Understanding the historical context of indigenous education is crucial in fostering diverse perspectives and critical thinking skills within the current educational landscape. The chosen children’s literary novel portrays indigenous education during the Dutch colonial era, conveying essential values such as leadership, courage, and resistance against colonization.

Numerous studies have emphasized the imperative integration of traditional and modern knowledge within educational paradigms influenced by Western educational patterns. In stark contrast to traditional education, Western educational systems underscore secular intellectual development, emphasizing neutral and objective scientific knowledge while compartmentalizing subjects, often neglecting the interconnectedness of diverse subjects and the rich tapestry of local knowledge originating from students’ backgrounds (Jima, Citation2022; Reyhner & Carjuzaa, Citation2017; Yeseraw et al., Citation2023).

For instance, Jima’s (Citation2022) research underscores the significance of integrating indigenous knowledge into the curriculum, particularly focusing on Ethiopia’s Gadaa system. The study highlights the pivotal role of indigenous knowledge in preserving cultural heritage, fostering sustainable development, and enhancing community well-being. It contends that incorporating indigenous knowledge into educational frameworks can deepen understanding, appreciation of local traditions, values, and practices, and empower marginalized communities, promoting social justice (Jima, Citation2022).

Despite the recurring curriculum changes in Indonesia, there persists a tendency to overlook invaluable indigenous educational practices (Muhammedi, Citation2016; Said, Citation2017; Sarwono, Citation2022). Sarwono (Citation2022) advocates for the collaboration between indigenous education and the current Indonesian curriculum to enrich children’s educational experiences. Integrating indigenous knowledge can enhance students’ cultural understanding, history, and local wisdom, fostering values such as mutual respect, diversity, and environmental conservation. While the current curriculum partially incorporates local cultural elements, there remains an inadequacy in comprehensive representation of indigenous knowledge. By complementing the curriculum with indigenous knowledge and practices, a broader and more enriched perspective can be offered to students, allowing them to appreciate their cultural heritage while promoting a deeper understanding of societal diversity (Sarwono, Citation2022).

Indonesia possesses relevant indigenous education potential in the present context. The ideas of Ki Hadjar Dewantara, an Indonesian educational figure, demonstrate their compatibility with modern educational thinking and theories. For instance, Ki Hadjar Dewantara introduced the concept of Tri-Nga, which consists of Ngerti (cognitive), Ngrasa (affective), and Nglakoni (psychomotor), aligning with the well-known Bloom’s Taxonomy encompassing cognitive, affective, and psychomotor aspects. The concepts proposed by Ki Hadjar Dewantara were later implemented in education at Tamansiswa, which was established on 3 July 1922. By way of comparison, Bloom’s Taxonomy was introduced in 1956 by Benjamin Bloom (Arifin & Hermawan, Citation2022; Istiq’faroh, Citation2020; Noventari, Citation2020; Riyanti et al., Citation2022).

In addition, in Java, there is a learning method called ”nyantrik.” The nyantrik method is an instructional approach that originates from Javanese tradition. The term “nyantrik ” in Javanese means “guiding” or “directing.” This method involves a mentor who plays the role of a guide, companion, and giver of directions to individuals or groups in the process of learning and personal development. Typically, the mentor possesses specialized knowledge and skills in a specific field, such as local wisdom, traditional arts, or spiritual practices. Nyantrik emphasizes not only the transfer of knowledge but also direct learning through experiences and the application of cultural values and ethics that have been passed down from generation to generation (Fitriani, Citation2013; Respati, Citation2016; Widhyasa & CANDIASA, Citation2018).

Therefore, there is a need to explore good educational practices from various sources, including through ancient literary works. By studying and understanding indigenous educational practices found in literary works, we can gain deeper insights into indigenous educational practices that are still relevant in today’s era. The examination of indigenous educational practices can make a significant contribution in introducing native educational practices that still hold value and relevance in the context of modern education.

Children’s literary works with indigenous educational values should be explored from the past. One of the intellectual centers in Java in the past was Vorstenlanden. Vorstenlanden was an intellectual center in Java during the Dutch colonial era, and many authors produced literary works during that time. Vorstenlanden referred to the territories of the Jogjakarta Government and the Soerakarta Government. It was a term used in Javanese history starting from 1755 to denote the regions under the authority of the four Javanese monarchies that emerged from the Islamic Mataram Dynasty: the Surakarta Sultanate, the Yogyakarta Sultanate, the Mangkunegaran Principality, and the Pakualaman Principality. These territories were led by a governor (Rouffaer, Citation1931). Evidence of intellectual progress in Vorstenlanden was seen in the establishment of numerous schools in the region. Various schools with Western-style education (Dutch colonial) were present in Vorstenlanden (Bonaventura & Kusumawati, Citation2022). Vorstenlanden also had skilled native literary authors, with Jasawidaga being one of the prominent figures (Widati, Citation2001).

Children’s literature serves as a crucial source for comprehending indigenous education due to its openness in reflecting the values, norms, and everyday life of the society during that period. Its simplicity and age-appropriate approach aid in delivering educational messages clearly, while the narrative content can serve as a robust representation of the worldview and societal mindset of that era, allowing for an in-depth analysis of the values instilled and upheld by the community at that time (Santiago, Citation2020). The scarcity of studies on children’s literary works highlights a significant potential for conducting in-depth research to enrich the landscape of children’s literature studies in Indonesia, particularly in relation to indigenous education embedded within children’s literature. One notable literary work that embodies indigenous educational values is the novel Bocah Mangkunegaran by Jasawidagda. The author of this novel had a strong educational background and relevant experience as a senior teacher during the Dutch colonial era.

Exploring indigenous education within children’s literature from the past holds significant importance in the development of the current curriculum (III & Palmer, Citation1992). Delving into the indigenous educational experiences depicted in historical children’s literature offers profound insights into the values, norms, and educational practices upheld during that period (Almerico, Citation2013). Integrating this understanding into the contemporary curriculum aids in accommodating and honoring cultural diversity while recognizing and strengthening the local cultural identity in education (Pantaleo, Citation2002; Pires, Citation2011; Ross, Citation1994). It also provides students with the opportunity to better understand and appreciate the cultural heritage and traditions inherent in indigenous education, resulting in a more inclusive, relevant, and culturally enriched curriculum (Ross, Citation1994).

The selection of the novel Bocah Mangkunegaran as the subject of research is based on several factors. The author, Jasawidagda, possessed relevant expertise and experience in the field of education during that time. His involvement in teacher organizations and participation in social and political movements during the Dutch colonial era provided him with a deep understanding of the challenges and dynamics of education at that time. Being a senior teacher and actively engaged in various social and political activities in the field of education, his understanding and perspective on education during the Dutch colonial era offer valuable insights into examining the indigenous educational practices embedded within this novel (Rahayu, Citation1997).

Several studies have been conducted on the works of Jasawidagda, such as the works titled “Kirti Njunjung Drajat” and “Peti Wasijat” (ADELIA, Citation2020; Astuti, Citation2015; Munir, Citation2016; Novtarianggi & Sulanjari, Citation2020; Oktayana, Citation2021; Purwadi, Citation2016; Wahyuni, Citation2015). These studies reveal forms of indigenous resistance against the colonial system and caste in Java. For example, the novel “Kirti Njunjung Drajat” portrays the struggle of Javanese women to obtain education rights amidst the marginalization of women in Javanese culture. The abundance of studies on Jasawidagda’s works demonstrates his significant contribution to well-established and noteworthy literary works during the Vorstenlanden era. Jasawidagda’s works represent the resistance of the common people against the rulers, namely the Dutch and the Priyayi (Novtarianggi & Sulanjari, Citation2020). Jasawidagda was a renowned author of that time and served as a committee member of Algemene Middelbare School (AMS), which was equivalent to a high school (Suwondo, Citationn.d.a)

The novel Bocah Mangkunegaran takes the form of a journalistic novel. This novel is written in Javanese. Several characters, themes, and settings in the novel are representations of the real world. The entire story is set in Vorstenlanden around the years 1910–1930. Bocah Mangkunegaran tells the story of children attending a village school called pamulangan, which is a native school managed and taught by the local community. The children receive education from a great teacher who imparts knowledge about the local region, providing concrete descriptions of its situations and problems. The teacher also guides the children in practical activities such as observing traditional markets, raising ducks, being involved in irrigation management for rice fields, and more. The teacher also encourages students to engage in traditional arts, such as playing the gamelan (a traditional Javanese musical instrument) and singing Javanese songs. The novel also depicts the social situation of Javanese society during that time, including how to handle thieves in the village, customary ceremonies, the exemplary behavior of Javanese kings, and myths within Javanese society. The novel is narrated by a teacher who teaches the real-life struggles of the lower-class people.

Indeed, so far, there is only one in-depth study on the novel Bocah Mangkunegaran. Priyatmoko’s (Citation2018) discusses the Scout or Padvinder movement in shaping the character and independence of Javanese children in the novel Bocah Mangkunegaran, enabling them to resist the colonial powers more fiercely. This study reveals how indigenous education during that period taught values of leadership, bravery, and the spirit of resistance against the colonizers. Through Priyatmoko’s previous research, the important role of the Padvinder movement in shaping the characters of Javanese children to be strong and capable of fighting against the colonizers has been revealed (Priyatmoko, Citation2018).

Other research studies have utilized the novel Bocah Mangkunegaran as a secondary reference to provide a concrete depiction of the pre-Independence era in Indonesia. Barokah’s (Citation2016) on the Sisworini School at Pura Mangkunegaran in Surakarta from 1912 to 1943 uses selected stories from the novel Bocah Mangkunegaran as a comparative illustration of native people’s schools (Barokah, Citation2016). Wibowo’s (Citation2011) on Education and Social Change in Mangkunegaran Surakarta from 1912 to 1940 also includes excerpts from the novel Bocah Mangkunegaran to depict native people’s education and the social changes occurring in Surakarta (Wibowo, Citation2011). Additionally, Ramadhani’s (Citation2019) on the transition from the Kepanduan movement to the Scout movement: The Birth of the Scout Movement in Indonesia from 1959 to 1961 includes selected stories from the novel Bocah Mangkunegaran as an initial reference to the formation of the Scout movement in Indonesia (Ramadhani, Citation2019).

A comprehensive understanding of this literary work could significantly contribute to the development of a more comprehensive and contextually relevant educational approach. Within the context of education in Indonesia, which predominantly emphasizes imported modern curricula, exploring indigenous educational practices depicted in literary works can directly contribute to bridging the gap and stimulating innovative education rooted in local culture and values.

This study also demonstrates how indigenous educational practices can engage children in a more holistic and inclusive learning process, integrating cultural elements, local knowledge, and relevant values. Indigenous education during the colonial era remains highly relevant in the current educational context in Indonesia. In the era of globalization and multiculturalism, learning that integrates local values, culture, and history becomes crucial in developing broader understanding, appreciation of diversity, and fostering critical skills among students. The novel Bocah Mangkunegaran offers a portrayal of indigenous education during the Dutch colonial period that effectively teaches values of leadership, bravery, and the spirit of resistance against the colonizers.

In the current educational context, which is increasingly connected to global and multicultural challenges, introducing indigenous educational practices through literary works such as Bocah Mangkunegaran can provide valuable perspectives on cultural diversity, traditions, and different worldviews. This can inspire more inclusive educational approaches that value diversity and encourage the development of critical thinking, creativity, and problem-solving skills among students. By incorporating indigenous knowledge and practices into education, students can gain a broader understanding of the world, foster cultural appreciation, and develop the ability to navigate and engage with diverse perspectives and experiences. It promotes a more inclusive and culturally sensitive education system that prepares students to thrive in an interconnected and diverse global society.

In this research, an in-depth analysis will be conducted on the novel Bocah Mangkunegaran using a systematic and scientific academic approach. By integrating data from the novel, historical information, and related research, it is expected that this study will provide a more comprehensive understanding of the indigenous educational practices contained within the novel and their relevance in the context of contemporary education.

Based on the above description, a children’s literature novel Bocah Mangkunegaran has been relatively underexplored from various disciplinary perspectives. The novel is an intellectual product from Vorstenlanden in the 1930s. It represents its time period, considering the credibility of its author, who was validated by the royal court, the Dutch colonial authorities, and Balai Pustaka (the first national publisher in Indonesia that still exists today). Furthermore, the novel’s narrative style, employing a journalistic approach, captures factual events of its time and transforms them into fiction. The values of indigenous education will be examined using a postcolonial analysis framework.

2. Literature review

2.1. Historical background of indigenous education in Java

Javanese Island has been a target of world colonization throughout its history due to its strategic location and abundant natural resources. European nations, particularly the Netherlands, began practicing imperialism and colonization in the 17th century by dominating, reconstructing, and controlling Java Island due to its rich natural resources. The European nations established centers of government and trade, established plant nurseries, claimed land, implemented forced cultivation practices, constructed transportation infrastructure for agricultural produce, established factories, and exported their products primarily to European countries (Nuryadi, Citation2017). The reasons for imperialism and colonization on Java Island in the 19th century are explained in William Basil Worsfold’s writing, “Travel Writing: A Visit to Java.” The colonization had a significant impact on the indigenous population in Java, including the field of education, which experienced unfavorable conditions (Nuryadi, Citation2017).

From the 17th to the 19th century, the Javanese society lacked access to formal education. The transformation of education in Java began with the implementation of the Ethical Policy, which aimed to improve the education system by incorporating Western cultural elements (Priyatmoko, Citation2018). An article titled ”Een Eereschuld (Honor Debt)” published in De Gids magazine in 1899 by C. Th van Deventer served as a major catalyst for the emergence of the Ethical Policy, officially proclaimed by the Queen of the Netherlands in 1901. The primary motivation behind this policy was the belief that the Dutch government had a debt of gratitude and a moral responsibility to enhance the welfare of the indigenous population in Indonesia. The Ethical Policy encompassed three programs, including irrigation, transmigration, and education (Fakhriansyah & Patoni, Citation2019).

However, colonial education never had a deliberate intention to improve the welfare of the indigenous population in the colonial territories. Education was only provided for the Priyayi class, the high caste in Java who had connections to the Javanese royal family or worked in Dutch offices (Fakhriansyah & Patoni, Citation2019; Susilo & Isbandiyah, Citation2018). The indigenous population, in general, still faced limited access to education. The education provided was limited to basic and vocational education, aimed at fulfilling the labor needs of the Dutch colonial government.

The condition of education in colonized communities has been examined by Schnellert et al. (Citation2022). The study found that colonial practices have led to the marginalization of indigenous communities and students, where they were unjustly directed towards special education programs and faced systematic prejudice and discrimination within an education system that did not respect their ways of life and knowledge. Decolonizing education is a complex journey that requires long-term commitment (Schnellert et al., Citation2022).

The limited access to education for the majority of indigenous communities in Indonesia has given rise to the concept of indigenous education as a means of survival. Priyatmoko (Citation2018) states that indigenous education, organized in village schools (pamulangan), has sparked the awareness of indigenous communities about their plight of injustice. The ideas and implementation of this education reflect original intellectual capacity and have proven to be effective in overcoming the restrictions imposed by colonizers. For instance, the mobilization of Javanese children through the Javaansche Padvinders Organisatie (JPO), Padvinder is the Dutch word for a member of the Scouting movement, similar to a Boy Scout or Girl Scout, which was established by the Javanese ruler as an effort to educate indigenous children about unity and resistance against the colonizers through the organization. In the colonial context, these educational practices not only help indigenous communities to survive but also inspire intellectual resistance against the colonizers (Priyatmoko, Citation2018).

Essentially, the Javanese community has possessed rich indigenous knowledge in various fields, including agriculture, arts, music, and culture. Through the implementation of the Ethical Policy (Politik Etis), the indigenous population became involved in education. However, the education introduced by the Dutch government differed from the traditions of the indigenous community as it was based on Western-style education. Therefore, Western-style education was adapted to the cultural context of the community, such as the use of local languages like Sundanese and Javanese instead of the Dutch language (Vikasari, Citation2012).

Indigenous education began to take shape following the implementation of the Ethical Policy. Private schools, managed by foundations such as Muhammadiyah, emerged as a result. Muhammadiyah was established on 18 November 1912 by Kyai Haji Ahmad Dahlan and marked the beginning of Muhammadiyah schools. Additionally, there was the establishment of Taman Siswa (1922) by Ki Hajar Dewantara and Madrasah schools (Syarif, Citation2019). These schools combined Western educational patterns with Javanese customs and traditions, aiming to create a synthesis between the two.

2.2. Children’s literature novels in Vorstenlanden in the 1930s

It is regrettable that the exploration of children’s literature in Indonesia remains markedly constrained. Current studies on Indonesian children’s literature predominantly emphasize the formal aspects and temporal scope of such literary works. Oejeng Soewargana addressed the evolution of reading materials intended for Indonesian children; however, the substance of the content does not correspond with the title. Instead, the focus is on delineating the characteristics and genres of appropriate reading materials for children (Soewargana, Citation1973). The writing does not delve into the development and progression of children’s reading materials in Indonesia. Additionally, Rusman Sutiasumarga briefly examines the role of Balai Pustaka (the state publishing house) in the development of children’s reading materials and family-oriented publications, as well as the work of the Commissie vor de Inlandsche School en Volkslectuur (Sutiasumarga, Citation1973).

The scarcity of studies on children’s literature in Indonesia can be attributed, in part, to the intellectual stigma in Java during that time, which regarded children’s literature as insignificant. Children’s literary works in Vorstenlanden in the 1930s were considered to be of low quality by Javanese intellectuals of that period. Children’s literature was seen as peripheral reading material and not even recognized as literary works (Quinn, Citation1992). Most of the children’s literary works produced during that time were packaged in small and simple books, giving the impression of being of lower quality. This perception arose because the content primarily focused on moral lessons and lacked significant literary value, leading it to be seen merely as textbooks for schoolchildren (Prawoto, Citation1993; Ras, Citation1985; Suwondo, Citationn.d.-a; Widati, Citation2001). However, some of these works are still studied within adult literature. The works often discussed include “Jarot” by Jasawidagda and “Kanca Anyar” by Soeratman Sastradiardja. “Jarot” and “Kanca Anyar” contain themes of resistance against the Priyayi (Javanese aristocracy) and the Dutch. One of these children’s literary works is Bocah Mangkunegaran by Jasawidagda. The children’s novel Bocah Mangkunegaran is chosen precisely because there has been no study conducted on this particular children’s literary work.

The field of children’s literature research worldwide has shown rapid development. Hundreds of studies on children’s literature from various parts of the world have been published (Yanti & Rosmansyah, Citation2019). Various aspects of children’s literature have been extensively studied, including children’s voices, genres of children’s literature, forms of children’s literature, children’s literature in education, the benefits of children’s literature, and more (Akinyemi, Citation2003; Azhar, Citation2015; Manly, Citation2018; Rajabov & Jalilova, Citation2021; Santiago, Citation2020; Tehseem & Khan, Citation2015; von; Merveldt, Citation2015). Ideological studies have also been conducted in children’s literature, such as feminist studies in children’s literature (Santiago, Citation2020). Study after study has made significant contributions to the field of children’s literature. Research on classical children’s literature has been conducted by Hinderer, who curated children’s literature with the theme of “racing” in America from 1930 to 1945 (Hinderer, Citation2016). Evans also examined classical children’s literature in England used as children’s reading material from 1550 to 1800 (Evans, Citation2018). Children’s literature with indigenous educational values has been studied by Akinyemi in Yoruba-language children’s literature (a local language in West Africa) (Akinyemi, Citation2003).

Furthermore, there are studies that interconnect indigenous education, children’s literature, and curriculum. Research conducted by McCarty and Lee emphasizes the significance of a critical education approach that upholds culture to fortify the sovereignty of indigenous education. Meanwhile, Cajete’s research delves into the ecology of indigenous education, emphasizing the interconnectedness of nature and culture as an integral part of learning. Meyer’s study highlights the importance of diverse resources from the Native American perspective within the curriculum, particularly in children’s literature, leveled readers, and social studies curriculum. Overall, this collective body of research advocates for the inclusion of indigenous values, culture, and perspectives within the educational curriculum to strengthen the sovereignty of indigenous education (Cajete, Citation1994; McCarty, Citation2002; Meyer, Citation2011). However, these studies were not specific to the Indonesian context. There is still great potential for researching classical children’s literature with indigenous education in Indonesia.

During the 1930s, Javanese intellectuals held a prevailing perception that the children’s literature works in Vorstenlanden were of low quality and did not qualify as literary works. The majority of children’s literature produced during that period were presented in compact and uncomplicated book formats, thereby creating an impression of inferior quality. This perception stemmed from the fact that the content primarily comprised moral teachings, lacking substantial literary value. Consequently, these works were regarded solely as instructional materials for school children (Ras, Citation1985). Consequently, Javanese literary scholars neither acknowledged them as literature nor considered them anything beyond mere reading material. In contrast, only traditional written works in the form of macapat songs were regarded as literature.

The literary works that gained recognition from the royal and Dutch colonial authorities were published by Balai Pustaka. Balai Pustaka, established on 15 August 1908 under the name “Commission for People’s Reading” (Commissie voor de Inlansche School en Volkslectuur) by the Dutch East Indies government, served as a book publishing company. In addition to publishing novels targeted at adult readers, Balai Pustaka also produced various types of children’s novels (Fitriana, Citation2019; Hutomo et al., Citation1988). Aligning with the aforementioned viewpoint, many prose works comprising novels published by Balai Pustaka exhibit a prevalent stylized nature. Numerous humorous anecdotes and scenes are condensed into a series of biographical narratives, aiming to impart moral education to school children. Within this context, prose works such as “Durcara Arja” and “Trilaksila” are referred to as novels due to their substantial length and incorporation of Western-style narrative elements (George Quinn, Citation1995). Furthermore, during the transitional phase of modern Javanese literature, tembang were authored and published to cater to the educational needs of school children during that era. Notable examples of such works include “Kakarangan” (1873) composed by Astranagara, “Wacan” (1883) composed by Kramaprawira, and “Carita Becik” (1881) composed by Reksatenaja (Christantiowati, Citation1996). Children’s literary works in the form of novels in the 1930s were not considered to have noble values like literary works for adults. Therefore, at this time it is difficult to find classic children’s literature books in good condition.

2.3. Indigenous education

Indigenous education is an educational approach that is deeply embedded in the life and culture of local communities. It recognizes the unique perspectives, worldviews, cultural practices, and traditions of indigenous people, and considers them integral to the process of individual learning and development (Battiste, Citation2005; Keane et al., Citation2017; McCarty, Citation2003).

Indigenous knowledge systems and practices have been transmitted across generations for thousands of years through rituals, storytelling, observation, listening, weaving, creation, hunting, farming, cooking, and dreaming, among other means. Traditional forms of indigenous education persist in local contexts. In response to the erosion and loss of indigenous knowledge resulting from processes of colonialism, globalization, and modernization, various new forms of indigenous education have emerged in different parts of the world (Biermann & Townsend-Cross, Citation2008; Nakata, Citation2003; Steinhauer, Citation2002).

Indigenous education plays a pivotal role in fostering cultural continuity among children. It provides them with opportunities to explore both traditional and innovative ways of maintaining a connection to their region. Moreover, it encourages critical thinking in addressing the novel challenges and threats faced by their communities. Consequently, young individuals become supportive of their elders in safeguarding their culture and territory, facilitating positive changes deeply rooted in their ancestral heritage, while demonstrating adaptability and resilience (McCarty & Nicholas, Citation2012).

Furthermore, indigenous education equips children with a profound understanding of intricate concepts and philosophies. It enhances their pride in their unique identities and cultures while promoting a broader comprehension of the diverse cultures across the globe. This generates a heightened sense of shared destiny and contributes to the burgeoning indigenous rights movement (McCarty & Nicholas, Citation2012).

In summary, indigenous education serves as a potent tool for empowering indigenous children, preserving cultural heritage, and advancing social justice. It recognizes and values indigenous knowledge and traditions, empowering young individuals to navigate the complexities of the modern world while remaining firmly rooted in the wisdom passed down through generations.

2.4. Post-colonial

Post-colonialism refers to a set of ideas that focuses on the relationship between culture and imperialism. Imperialism is defined as the practice, theory, and attitude of a dominant center controlling a distant territory, which goes beyond colonialism in terms of establishing settlements (Kincaid, Citation2005; Said, Citation2003). Post-colonialism encompasses three main meanings: (a) the end of colonial empires worldwide, (b) writings related to colonial experiences, and (c) theories used to analyze post-colonial issues. The emergence of post-colonial theory was triggered by the Commonwealth’s attempt to study the effects of British colonization (Barry, Citation2020).

In his book Orientalism, Edward Said argues that colonial discourses had a dominant influence over the Eastern world. The West regarded the East as a valuable resource to be exploited. In this utilization process, the West equated the East with the West in terms of politics, socio-economics, lifestyle, and culture (Said, Citation2012). Said suggests that this domination was not solely political but also cultural, reflecting the peculiarities of Dutch colonial politics known as “devide et impera” (divide and conquer), which established political, economic, social, and cultural orders. Socially, this was manifested through the imposition of the colonial social stratification system on top of the pre-existing feudal social stratification. Culturally, the colonial government allowed local people to maintain their language, literature, and interactional patterns. However, in the realm of modern literature, Javanese society faced the challenge of colonial hegemony, similar to other colonized societies, which involved the infusion of colonial ideology into their literary works. Said argues that post-colonialism focuses on studying the relationship between colonizers and colonized countries during and after the colonial period (Said, Citation2007), providing paradigms, methods, and tools for understanding power relations.

Orientalism, as described by Edward Said, diagnoses how imperialism operates in discourse concerning intellectuals and culture. Important concepts in post-colonial studies include diaspora, hybridity, ambiguity, mimicry, mestizaje, and creolization, as discussed by Young (Citation2012).

Mimicry, a concept introduced by Homi K. Bhabha, is crucial in post-colonial studies. Foulcher (Citation1995: 105) explains that Bhabha views mimicry as the imitation of European subjectivity within a “impure” colonial environment, reconfigured in response to the sensibilities and anxieties of colonialism. Faruk (Citation2007: 6) suggests that there is a potential for mockery of the colonizers through the act of impersonation by the colonized society, as they do not fully replicate the model offered by the colonizers. Mimicry possesses the power to challenge colonial authority (Huddart, Citation2006: 122–123). Additionally, Bhabha reveals that mimicry unveils something different beneath the surface of what the natives present.

3. Method

This was a qualitative study. Qualitative study is conducted to synthesize documents of cultural observations, new insights, and differences of opinion about individual and social complexities and art as an embodiment of human meaning, and/or criticism of existing social orders and the initiation of social justice (Kim et al., Citation2017; Lambert & Lambert, Citation2012; Merriam, Citation2009; Stanley, Citation2014).

The data collection process for this study was conducted in two distinct phases. Firstly, data from the novel source was gathered through literary analysis in a designated space. Additionally, field interviews were conducted with relevant informants located in Surakarta and Yogyakarta, previously known as Vorstenlanden. In-depth interviews with these informants were conducted in February 2023 with a specific objective of comprehending the issues present within the novel, which serves as the primary data source for this research. The interviews aimed to explore the connections between the depiction of social and cultural issues within the novel and their relevance to real-life situations. The selection of interview informants was based on their expertise in Javanese history and literature research, their proficiency in these fields, and their involvement as scholars and cultural figures in the history of Surakarta and Javanese Literature. The identities of these sources are detailed in the subsequent table, and they explicitly expressed their preference for anonymity through the use of initials or maintaining confidentiality. The informant information can be seen in the following Table .

Table 1. Interview Informants

The dataset under examination in this research comprises textual materials sourced from children’s literature novels originating from Vorstenlanden in the 1930s. The novel selected for comprehensive analysis is “Bocah Mangkunegaran” by Jasawidagda, primarily chosen for its incorporation of indigenous educational elements. Notably, this particular children’s literature work has not been subject to prior interdisciplinary scrutiny. It represents an intellectual product of Vorstenlanden during the 1930s, bearing the endorsement of both the kingdom and the Dutch colonial authorities, along with Balai Pustaka’s recognition.

The qualitative data analysis process adhered to the four stages as proposed by Miles and Huberman, encompassing data collection, data reduction, data display, and the eventual drawing of conclusions or verification, as elucidated by Brinkmann (Citation2009). The research team initiated the analysis by systematically organizing the amassed data, culminating in the interpretation and subsequent deduction of conclusions rooted in the scrutinized information.

4. Findings and discussion

The context depicted in the novel Bocah Mangkunegaran highlights the Javanese society of the 1930s, characterized by social class divisions. Javanese society was classified based on various factors, such as land ownership, which held significant value during that period. Consequently, social classes emerged based on the ownership of land. Apart from land ownership, social class divisions were also influenced by the nobility of individuals, which in turn impacted the education opportunities available to their descendants. This study focuses on the division of social class specifically concerning the rights to education. The social class division related to education rights can be categorized into two groups: the priyayi class and the kawula alit class (commoners). The priyayi class comprises the ruling Javanese kings, their descendants, and relatives.

As the Dutch East Indies government had an increasing need for the management of the native bureaucracy, individuals outside the royal family were given the opportunity to attain certain administrative positions within the government bureaucracy. This was made possible through education and the ability to speak Dutch. For instance, positions such as clerks, prosecutors, tax officers, teachers, and paramedics were generally attainable after completing their education. However, they were still restricted from occupying high-ranking positions such as regents. In other words, intelligence, skills, or diplomas alone were not sufficient qualifications to become a regent. An individual also had to possess a noble lineage. Consequently, the priyayi group further evolved into two tiers: the high priyayi class (consisting of individuals with noble descent) and the low priyayi class (comprising priyayi based on educational background).

Non-priyayi communities have limited access to formal schools created by the Dutch. There is no formal mechanism through which lower class children can access formal education. Children from the lower class can pursue formal education on the basis of luck. For example, the closeness of their parents to the Dutch and the kingdom would give their children the privilege to receive formal education.

The limited opportunities for changing fate or ascending in social class contribute to a sense of hopelessness among the lower classes in Java. As a form of resistance, the lower class equips their children through indigenous education, which is initiated by the village community. This educational approach takes place in pamulangan desa schools, where lower-class children in rural areas are taught by individuals considered intelligent and appointed by village officials. The novel Bocah Mangkunegaran provides a glimpse into the lives of these lower-class children attending pamulangan desa schools, which can be seen as a response to the Dutch educational hegemony by emphasizing indigenous education.

Bocah Mangkunegaran is a historical novel that incorporates factual information. It employs a journalistic storytelling style and is complemented by hand-drawn illustrations and photographs, enhancing its authenticity. The novel primarily revolves around the experiences of children and teachers in pamulangan desa schools, adopting a child’s perspective. The story’s contents revolve around the everyday lives of Javanese children in pamulangan desa classes, which are intertwined with various learning materials such as history, folklore, mythology, puppetry, art, geography, local landmarks, and the economy. The context of the pamulangan desa classes showcases the characteristics of indigenous education, encompassing economic education for non-priyayi individuals, character education and schooling for Javanese children, education on Javanese religiosity (kejawen), mythology, and puppetry, regional education and local history, as well as scouting education (padvinder).

4.1. Economic education for non-priyayi people

In the novel “Bocah Mangkunegaran,” children are instructed to cultivate modest aspirations that align with the societal demands. This humble ideal carries a profound purpose: to instill an awareness of their position within the lower strata of society. However, the earlier individuals comprehend this reality, the more likely they are to develop resourceful survival mechanisms. It is anticipated that this creative way of life will facilitate the transformation of the prevailing social class and feudalistic system, enabling the establishment of a self-sufficient grassroots economy.

In the interviews with the historian HP (2023), we gain valuable insights into the historical backdrop of economic exploitation, social disparity, and resilience within this era. Economic inequality was widespread, characterized by a narrow elite’s consolidation of extensive land holdings and wealth. Nevertheless, Javanese communities actively participated in localized economic endeavors, such as small-scale agriculture, craftsmanship, and trade, as endeavors aimed at attaining economic autonomy and self-sufficiency.

“Local economic initiatives were vital for the survival and resilience of Javanese communities. They represented a pathway to reclaim economic agency and preserve cultural practices in the face of colonial dominance.” (HP, 2023)

“It is essential to acknowledge the resilience of the Javanese people. They navigated the complexities of colonial economic pressures while innovatively preserving their cultural heritage and economic self-sufficiency.” (HP, 2023)

In light of the interview excerpt, Mr. HP asserts that the economic history of Dutch colonial Java, as portrayed in “Bocah Mangkunegaran,” encapsulates a nuanced narrative encompassing themes of exploitation, inequality, and resilience. It is evident that local economic initiatives surpassed mere survival strategies, serving as a conduit for the preservation of cultural identity and a means of contesting the dominant economic hierarchy imposed by Dutch colonial authorities. These insights provide invaluable historical context for a comprehensive understanding of the economic milieu of the period and the enduring determination of the Javanese populace.

The crux of this transformation resides in the promotion of independent entrepreneurship, which empowers the lower-class population to reshape their economic circumstances. By relying on an entrepreneurial-driven people’s economy, they challenge the existing social hierarchy rooted in hereditary (priyayi) privileges, Dutch nobility, and land ownership. Non-priyayi students, even though unable to ascend to the priyayi class, can still aspire to economic advancement through ventures such as duck farming. The simplicity of these ideals is exemplified when the teacher in the village simulation illustrates the income generated by duck breeders, as depicted in the following excerpt.

Javanese text:

Coba, tak petungake grambyangan pamêtune wong ngingu bèbèk. Kowe kuwat angon bèbèk 60. Watake bèbèk kuwi sêsasi têrus ngêndhog, sêsasi ora, dadi racake kowe sadina olèh êndhog 30. Êndhog siji tak gawe rêga 2 sèn, dadi 30 rêga 6 kêthip. Kanggo ragad ingon jagung, dhêdhak, 1 kêthip. Dadi kowe sadina rak duwe pamêtu satêngah rupiyah, sêsasi 15 rupiyah, mèh padha karo blanjaku. (Bocah Mangkunegaran, 1937, 54)

Translation:

Let’s try to calculate the income of the people who raise ducks. You can raise 60 ducks. In one month, ducks can lay 30 eggs. You sell one egg for 2 cents, so 30 eggs mean 6 kethip. The cost of buying the food is 1 kethip. So, in a day, you earn half a rupiah, in a month 15 rupiah, almost the same as your salary as a teacher. (Bocah Mangkunegaran, 1937, 54)

At the heart of this transformation lies the promotion of autonomous entrepreneurship, endowing the lower socio-economic strata with the agency to reconfigure their economic circumstances. By nurturing an entrepreneurial-oriented grassroots economy, they actively contest the prevailing social hierarchy entrenched in hereditary (priyayi) privileges, Dutch aristocracy, and land ownership. Importantly, this economic paradigm extends its reach to non-priyayi students who, despite being precluded from ascending to the priyayi class, can nonetheless aspire to economic advancement through ventures such as duck farming. The simplicity of these principles finds a poignant illustration in a simulated village scenario, wherein an instructor computes the revenue generated by duck raisers: “Let us endeavor to compute the earnings of those engaged in duck farming. Consider the possibility of raising 60 ducks. Over the course of one month, these ducks can yield 30 eggs. Given the market rate of two cents per egg, the total revenue from 30 eggs amounts to 6 kethip. Deducting the expenses for purchasing feed at 1 kethip, one can deduce that daily earnings stand at half a rupiah, resulting in a monthly sum of 15 rupiahs—nearly equivalent to a teacher’s salary”

The teacher in the quote shows efforts to motivate children to be independent through livestock business. Students in pamulangan desa are also taught to observe types of work in the market and at home. Traditional markets are considered as centers of indigenous economic activity. In the market, various people’s economic activities can be observed. One of the students observes a chicken blantik or a chicken broker. Children observe the process of price negotiation, seller-buyer gimmicks, and the amount of profit, as shown in the following quote.

Javanese text:

Jam sadasa pêkên mèh bibar. Ayamipun Pak Suta taksih jangkêp 30. Wontên bakul saking Wanagiri. Punika rêmbagipun radi dangu. Ayam 30 lajêng dipun gêbag radin katumbas f 5.-.

Petangan bathinipun Pak Suta:pajêngan: f 0.30 + f 0.75 + f 5.-= f 6.05kilakan: f 3.50 + f 0.25 = f 3.75dados bathi : f 2.30. (Bocah Mangkunegaran, 1937, 96)

Translation:

At ten o’clock, the market will close. Mr. Suta still has 30 chickens. There is a seller from Wanagiri. The process of buying and selling this time is a bit long. In the end, 30 chickens were bought and purchased at a price of f 5,-.The calculation of Mr. Suta’s profit:Sales: f 0.30 + f 5 = f 6.05Wholesale: f 3.50 + f 0.25 = f 3.75Gain: f 2.30. (Bocah Mangkunegaran, 1937, 96)

The passage highlights the teacher’s endeavor to promote children’s independence through involvement in livestock businesses. Within the pamulangan desa setting, students learn to observe different work activities, both in markets and households, with traditional markets serving as hubs of local economic activity. In these marketplaces, students witness a variety of economic practices, including a specific instance where one student observes a chicken broker, closely examining aspects such as price negotiation, seller-buyer interactions, and profit calculation.

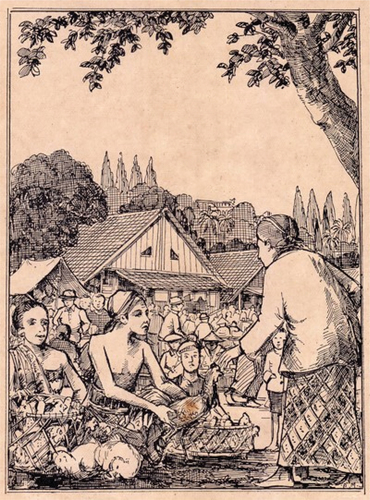

Figure in the novel “Bocah Mangkunegaran” illustrates the immersive approach of indigenous education within pamulangan desa. It portrays the students’ exposure to various economic activities, especially in traditional markets that serve as local economic hubs. The depiction of a student observing a chicken broker highlights the practical learning experiences aimed at promoting independence and economic understanding. Through these observations, students gain insights into price negotiation, seller-buyer interactions, and profit calculation, which are integral aspects of their education within the indigenous system. This illustration underscores the role of pamulangan desa in equipping students with real-world skills while preserving traditional economic practices.

Figure 1. Illustration in the novel about market atmosphere (Bocah Mangkunegaran, Jasawidagda, Citation1937, 95).

In addition to the market, household economic activities also serve as the foundation of the people’s economy. These businesses, often passed down through generations, include occupations such as blacksmithing. One of the students, Besi, was the son of a blacksmith. In the village simulation, the teacher encouraged Besi to closely observe his father’s work and compare it with other blacksmiths, seeking gaps or innovative techniques that could later become his specialized knowledge. Another child was assigned to observe the river’s flow. Understanding the natural flow of the river was essential for manipulating it effectively, particularly for irrigation purposes in the rice fields. This child was entrusted with the duties of a jagatirta, responsible for managing the water resources.

This form of grassroots business is regarded as a means of achieving economic independence. While formal schools, following the Dutch education system, focus on theoretical studies, public education emphasizes practical knowledge that is directly applicable within the local context. Ashcroft (2001:20) suggests that resistance or struggle can take various forms, not limited to overt or radical resistance but also encompassing passive resistance. Passive resistance can be achieved through the preservation of identity and culture. In the Bocah Mangkunegaran novel, the Javanese people employ mimicry by imitating the educational process imposed by the colonizers, yet their focus remains on survival during the era of Dutch colonialism.

The author of the novel possesses a deep understanding of Javanese syncretism, which does not prioritize materialistic pursuits. Javanese culture discourages the accumulation of wealth and material possessions. Instead, values such as self-sufficiency hold great significance, whereby individuals are willing to spend money to maintain their position of authority. Through children’s literature novels, the author aims to challenge the Javanese paradigm. The Bocah Mangkunegaran novel illustrates the efforts made to survive and attain authority through the path of the people’s economy. Children are encouraged to comprehend the economic system that will guide them towards happiness and a life of sufficiency.

The novel depicts the people’s economy as a form of resistance through indigenous education. The author’s foresight recognizes that the Javanese people’s limited understanding of the economic system could be exploited by colonialists who would exert control through economic means. This passive and subtle resistance is manifested in the novel. Through children’s stories within the novel, education about the people’s economy is imparted with the aim of transforming the fate of future generations. Practical knowledge of the people’s economy is directly taught in the workplace, eschewing theoretical education. Children are accustomed to engaging in apprenticeships, known as “nyantrik ,” where they observe and actively participate in their chosen occupations.

4.2. Character education and schooling for Javanese Children

Pamulangan desa is a special school established for indigenous children from the lower class. It originated through the collective efforts of the villagers and the village community. This school is a form of mimicry, inspired by the educational institutions established by the Dutch colonialists in Vorstenlanden. The Dutch education system was exclusively accessible to the nobility, priyayi class, and royalty. Indigenous communities looked to Dutch educational institutions as a model for creating their own village schools, known as pamulangan desa.

The process of mimicry involved imitating the educational system, encompassing both the process and technical implementation of education. As a form of passive resistance, pamulangan desa retained its distinctiveness by diverging from the Dutch curriculum. In addition to the limited access to curriculum resources, the cultural values within pamulangan desa were deemed influential in nurturing a strong sense of attachment among the colonized population. The curriculum of pamulangan desa is built upon indigenous values, which serve as the foundation for the educational approach. Indigenous identity is further reinforced through the incorporation of local customs and character education in all learning activities.

Figure in the novel “Bocah Mangkunegaran” portrays the essence of indigenous education within pamulangan desa. The classroom’s simple woven bamboo structure symbolizes its divergence from the Dutch colonial curriculum, signifying passive resistance. Indigenous identity is reinforced through the incorporation of native values, customs, and character education, forming the foundation of the curriculum and fostering a strong cultural attachment among the indigenous students and teachers. This illustration underscores the role of pamulangan desa in preserving and transmitting cultural values despite colonial challenges.

Figure 2. Illustration in the novel about pamulangan desa (Bocah Mangkunegaran, Jasawidagda, Citation1937, 72).

Character education in this context encompasses the use of emotions, mythology, local wisdom, politeness, manners, mysticism, and local religiosity, surpassing the sole reliance on logic and reason. Logic and reason are considered secondary to character and moral education. In the novel Bocah Mangkunegaran, children are depicted as actively participating in village events. They engage in chanting gendhing (Javanese songs) and rewang (collaborative work), which serve to instill a sense of their role within society. They are taught to prioritize communal and environmental concerns over individual interests. Community well-being takes precedence over personal gains. This stands in contrast to the concept of modern education, which often promotes competition, monopolization, and a capitalist mindset.

In an interview with GAU (2023), the Javanese historian, it was revealed that Pamulangan desa is a unique school designed for indigenous children from lower-class backgrounds. It was established through the joint efforts of villagers and the local community, inspired by Dutch colonial educational institutions in Vorstenlanden, which were exclusive to nobility and royalty. This mimicry, as a form of passive resistance, involved replicating certain aspects of the Dutch education system while maintaining distinctiveness by diverging from the Dutch curriculum. Pamulangan desa, with limited curriculum resources, emphasizes indigenous cultural values in education, focusing on principles like “sepi ing pamrih” (absence of negative intentions) and uses different language registers (ngoko, kromo, kromo inggil) to reinforce indigenous identity and cultural nuances within the educational context.

Figure depicts an image of a female puppet named Dewi Sri. Javanese wayang characters, sharp noses, long hair, full of accessories and jewelry, ornaments with headbands, arm bracelets, necklaces, and batik cloth on his waist. Dewi Sri is the goddess of fertility in Javanese agricultural mythology.

Figure 3. illustration of the novel, the figure of Dewi Sri in a poppet (Bocah Mangkunegaran, Jasawidagda, Citation1937, 30).

The Javanese people adhere to certain attitudes and principles in their way of life, which are essential for social harmony. These principles include “sepi ing pamrih,” which signifies the absence of negative intentions, harmonious coexistence, respectfulness, vigilance, trust, sincerity, prasaja (simplicity), bekti (devotion), and andhap asor (humility).

The value of andhap asor is reflected in the use of different language registers within the novel. There are three levels of language: ngoko, kromo, and kromo inggil. Ngoko language is used when children converse among themselves. Kromo language is employed when children interact with older children or adults. Kromo inggil is reserved for conversations between children and parents, teachers, aristocrats, or kings. Kromo inggil is also used when discussing matters pertaining to royalty or the priyayi class.

In the novel Bocah Mangkunegaran, students are taught to demonstrate care and respect towards mature adults. They are instructed to maintain a quiet demeanor and attentively listen during ancestral prayers conducted in the ritual of a clean village. One child, however, succumbs to temptation and disobeys the norms of decency by glancing at the ingkung (chicken for offerings in traditional ceremonies) while praying. Unable to resist, the child proceeds to cut a portion of the ingkung, taking the largest piece for themselves while their peers receive smaller portions. This act is viewed as a violation of ethical norms and is deemed unfair, as it disregards the well-being of others.

Many prevailing educational systems promote individualism, reinforcing the notion that personal development and progress come from pursuing one’s self-interests. Furthermore, national education systems often emphasize materialism, perpetuating the belief that human beings are separate from nature and that all resources on Earth exist solely for human benefit. This perspective prioritizes wealth accumulation as the primary means to achieve life satisfaction and happiness.

4.3. Javanese religious education (Kejawen), mythology, and puppet

The predominant form of Javanese religiosity is known as abangan or kejawen. Abangan or kejawen groups place emphasis on the animistic aspects of Javanese syncretism, which is often associated with rural or peasant communities. Ancestor worship is a significant manifestation of Javanese religiosity. Ancestors, known as close ancestors or danyang in villages, are believed to be a source of power and are considered the bestowers of the cultural and civilizational foundations that sustain the community. It is believed that ancestors continue to exert influence on the living.

In the novel Bocah Mangkunegaran, students in pamulangan desa are taught the Javanese ritual dedicated to Dewi Sri (Dewi Sri is a goddess in Indonesian mythology associated with rice, fertility, and agricultural abundance). Dewi Sri symbolizes prosperity for farmers. The Javanese belief holds that the success of agricultural endeavors is attributed to Dewi Sri, who provides assistance to the common people. Indigenous education instills in Javanese children a sense of optimism regarding self-reliance through submission to nature. Nature operates under its own mechanisms, and by surrendering to nature, individuals can place their hope in the strength of their ancestors rather than relying on other human beings. Within the context of colonialism, this religiosity serves to alleviate the fear of colonialists, as Javanese people can still draw upon the power of their ancestors and deities.

The Javanese religiosity fosters introspection and a profound awareness of human vulnerabilities. Javanese people acknowledge that the course of life is shaped by the divine and the forces of nature, adopting a fatalistic attitude. This surrender to the divine will is known as nrima ing pandum, which means accepting what is given, and sumeleh, which means making peace with the circumstances one experiences. These beliefs and attitudes have enabled the Javanese to find contentment and derive enjoyment from life even amidst the challenges of Dutch colonialism.

The illustration of Dewi Sri, the Javanese goddess of fertility, in the novel “Bocah Mangkunegaran” encapsulates the indigenous educational emphasis on the intrinsic connection between nature, spirituality, and Javanese cultural identity. Presented in traditional Javanese wayang style, Dewi Sri symbolizes the pivotal role of agricultural abundance in Javanese society, reinforcing the notion that prosperity and self-reliance are intertwined with nature and ancestral strength. In the context of colonialism, this portrayal illustrates the resilience of Javanese youth, as they draw inspiration from indigenous beliefs to confront external challenges, perpetuating a profound cultural heritage that transcends adversity.

In an interview with AH (2023), a Javanese Spiritual Leader, Pastor, and Cultural Scholar, it was elucidated that the prevailing form of Javanese religiosity is commonly referred to as abangan or kejawen. These groups prioritize the animistic facets of Javanese syncretism, particularly prevalent in rural and peasant communities. Ancestral reverence holds paramount significance in Javanese religiosity, where ancestors, known as close ancestors or danyang in village contexts, are perceived as founts of power and custodians of the cultural and civilizational underpinnings that sustain the community. It is firmly believed that ancestors continue to wield influence over the living. Javanese religiosity engenders introspection and a profound recognition of human vulnerabilities. Javanese individuals acknowledge that the course of life is shaped by divine forces and the workings of nature, leading to the adoption of a fatalistic attitude.

In addition to Dewi Sri, the novel delves into various other myths and traditions, including the Mandhasiya ceremony. The purpose of the Mandhasiya ceremony is to purify the village and safeguard it from disasters. During each ceremony, offerings are made to the ancestors and Prabu Baka, the mythical giant credited with bestowing fertility upon the land following his demise.

Students in pamulangan desa are also instructed to offer prayers at ancestral graves as an act of reverence towards their predecessors. This indigenous education serves as a source of motivation for indigenous children, encouraging them not to relent in their struggle against colonial injustices through ancestral narratives that depict resistance against colonialism.

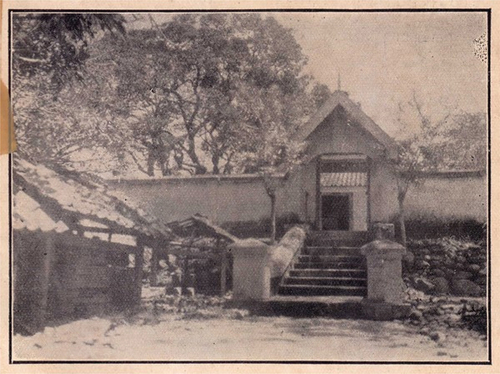

Figure depicts the practice within pamulangan desa where students pay homage and offer prayers at ancestral graves, symbolizing their reverence for ancestors and their commitment to resist colonial injustices. The image portrays ancestral graves enclosed by a wall with a single door, surrounded by trees, creating a solemn atmosphere. This ritual underscores the essence of indigenous education by emphasizing the link between cultural heritage, identity, and the determination to confront colonial oppression.

Figure 4. Illustration in the novel ancestral graves (Bocah Mangkunegaran, Jasawidagda, Citation1937, 18).

The novel explores the children’s fascination with shadow puppets, a prominent theme in Bocah Mangkunegaran. One of the central characters, Marija, aspires to become a skilled shadow puppeteer. In one chapter titled “Raden Wrekudara,” Marija undergoes training to master the art of puppetry. Marija captivates the other children with their puppetry skills, particularly in presenting a puppet story highlighting Raden Wrekudara’s supernatural abilities.

Shadow puppetry is a popular traditional performance in Indonesia. These shows convey various philosophical and life teachings. Shadow puppets serve as an effective medium for imparting knowledge among the local population. Notably, the Wali Sanga (Wali Sanga refers to the nine Islamic saints who played a significant role in the spread of Islam in Java, Indonesia), a group of Islamic scholars, employed puppets as a means of spreading Islam in Java. Moreover, puppetry was utilized during the people’s struggle against colonialism. In these instances, Dutch characters were depicted as giant figures in puppet stories to ensure their safety. One renowned story depicting the resistance against colonialism is the ”Babad Diponegoro.” This chronicle introduces the concept of a just queen who will rescue the people from the colonial oppressors. The depiction of the just queen symbolizes hope amid the chaotic conditions faced by society, with Prince Diponegoro representing a figure who is expected to restore order during turbulent times.

The prevailing Javanese religiosity, known as abangan or kejawen, emphasizes the animistic elements of Javanese syncretism, particularly within rural communities. Ancestor worship holds a central role, with ancestors seen as sources of power and cultural foundations. This belief persists in the idea that ancestors continue to influence the living. Javanese religiosity fosters introspection, acknowledging life’s course is shaped by divine forces and nature, resulting in a fatalistic attitude. These beliefs and rituals motivate indigenous children to resist colonial injustices through ancestral narratives and cultural practices. The novel “Bocah Mangkunegaran” explores various aspects of Javanese culture, including shadow puppetry, which serves as a vehicle for conveying philosophical teachings and historical resistance against colonialism.

4.4. Regional education

In the novel “Bocah Mangkunegaran,” the children are provided with an understanding of their local surroundings, including detailed maps and pictures of the respective areas. Due to limited access to knowledge sources, indigenous children often lack an understanding of their territorial boundaries. Their exposure to other regions is greatly limited, especially in 1930s Java when transportation options were scarce. Motorbikes and horse-drawn carriages were primarily used by aristocrats and colonialists, while indigenous people relied on walking or bicycles, which imposed significant spatial limitations. The novel intentionally presents concrete local and regional knowledge. The author, Jasawidagda, deliberately includes descriptions and illustrations of the areas surrounding Vorstenlanden. Each area depicted in the novel is accompanied by hand-drawn illustrations or photographs, providing visual context. Moreover, the descriptions highlight the valuable natural resources found within these regions. This can be seen in the following quote.

Javanese text:

“Ing Baturêtna. Sisih kidul: pagunungan gamping, padha didhudhuki diusung mênyang Baturêtna, dikirimake marang liya panggonan mêtu sêpur. Sisih wetan: watune warna-warna, mulane ana kapanewon aran, Batuwarna. Watu mau sing cilik-cilik kêna digosok kanggo kalung, mata ali-ali, bênik, warnane ana sing biru, kuning, abang, wungu, kaya akik. Malah ing bawah Tirtamaya ana gunung sing isi têmbaga, tau dipêlik băngsa Jêpang”. (Bocah Mangkunegaran, Jasawidagda, Citation1937, 38)

Translation:

In Baturetna, to the south: mountains of limestone are often excavated and transported to Baturetna, then sent to various areas by train. To the east: various types of rocks, so there is a Kapanewon (district) named Batuwarna. Colorful stones, the small ones were rubbed into necklaces, eye rings, buttons. The colors were blue, yellow, red, purple, like agate. In fact, under Tirtamaya there is a mountain filled with copper, which was once excavated by the Japanese. (Mangkunegaran Boy, 1937, 38)

Javanese text:

“Beda karo bawah kabupatèn kutha Mangkunagaran: ana pabrike gula têbu ing Calamadu lan ing Tasikmadu. Sisih wetan ana pabrik kopi lan sêrat nanas, yaiku ing Majagêdhang. Ing Matesih bêcik bangêt tandurane pari”. (Bocah Mangkunegaran, Jasawidagda, Citation1937, 39)

Translation:

It is different from the area under the Mangkunegaran City region: there are sugar cane factories in Calamadu and in Tasikmadu. To the east there are coffee and pineapple fibers, namely in Majagedhang. In Matesih it is very good to plant rice. (Mangkunegaran Boy, 1937, 39)

Javanese text:

“Pangupajiwane wong-wong desa kajaba têtanèn, iya sok nyambutgawe manut bakal kaananing bumine kono. Kaya ta wong Wuryantara dhewe banjur anggarap barang padhas. Wong Manyaran gawe topèng saka kayu waru, malah akèh sing bisa gawe wayang. Wong bawah Tirtamaya bisa anggosok watu. Wong Jatisrana gawe barang pring: kurungan, caping sapêpadhane. Wong Matesih kulina ambathik, sapiturute”. (Bocah Mangkunegaran, 1937, 39)

Translation:

The livelihood of villagers apart from being farmers really depends on the circumstances or conditions of the area they live in. Like the Wuryantara people, their livelihood is working on items from padas stone. The Manyaran people make masks from waru wood, many of them are also capable of making puppet. People under Tirtamaya are able to rub stones. Jatisrana people make handicrafts from bamboo: bird and chicken cages, hats, and so on. The Matesih people are used to making batik, and so on. (Bocah Mangkunegaran, 1937, 39)

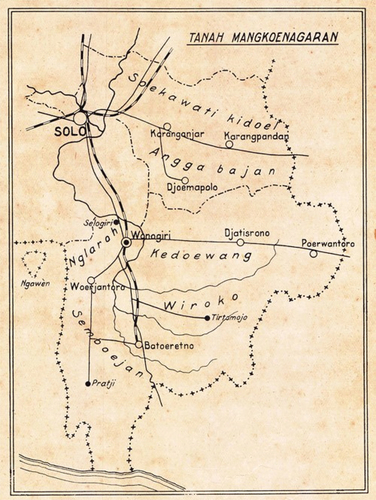

Figure , featuring an ancient map of the Mangkunegaran Kingdom, functions as a tangible manifestation of the indigenous educational principles elucidated in the novel “Bocah Mangkunegaran.” This visual aid operates as a didactic instrument within the narrative, complementing the cited excerpts that underscore the significance of imparting indigenous wisdom to young learners. Jasawidagda, the author, purposefully integrates intricate portrayals of the diverse regions surrounding Vorstenlanden in the text, often accompanied by hand-drawn illustrations or photographs. These elements provide a contextual framework, connecting indigenous children with their immediate surroundings. These descriptions not only offer insights into the geographical landscapes but also accentuate the richness of natural resources within these areas, including references to limestone mountains, vibrant stones, and copper deposits. This localized knowledge serves a dual purpose: acquainting indigenous children with their ancestral territories, thereby nurturing a profound sense of attachment and belonging, and equipping them to cherish and safeguard their cultural and environmental legacy, thereby instilling an awareness of the value of their surroundings beyond their immediate experiences. Consequently, the novel emerges as a pivotal tool in fostering a profound bond between youthful readers and their local milieu, thereby catalyzing the preservation of their heritage in the face of potential external threats and exploitation.

Figure 5. Novel illustration, map of the Mangkunegaran area (Bocah Mangkunegaran, 1937, 37).

The significance of local attachment and understanding for indigenous communities cannot be overstated. However, these communities often find themselves embroiled in territorial disputes, with their lands subject to claims by more influential actors, including colonial powers. The novel “Bocah Mangkunegaran” endeavors to underscore the vital importance of indigenous territories. Its author, Jasawidagda, meticulously highlights the natural resources abundant in each region while emphasizing the necessity of safeguarding them against various threats. Through the medium of territorial education, the novel provides indigenous communities with a tangible map of the archipelago, a tool they can employ to reclaim their ancestral lands from colonial forces. Gradually, this educational approach plants the seeds of resistance against colonialism, nurturing an awareness of the paramount significance of protecting their local territories.

To validate the historical accuracy of the information presented in the text, comprehensive interviews were conducted with historian HP (2023). According to Mr. HP, the passages extracted from “Bocah Mangkunegaran” faithfully depict the geographical and economic landscape of the Mangkunegaran region during the 1930s. His assessment corroborates that Baturetna was renowned for its limestone mining activities, with the extracted limestone indeed being transported by train to various destinations. Moreover, Mr. HP confirmed the existence of sugar cane factories in Calamadu and Tasikmadu, as explicitly detailed in the text. Additionally, he asserted that the descriptions of different villages and their distinctive economic activities, such as the craft of creating masks from waru wood in Manyaran and the practice of batik-making in Matesih, accurately mirror the prevailing local livelihoods of that era. He underscored the immense value of such precise, region-specific details in shedding light on the historical and cultural milieu of the time. In conclusion, Mr. HP authoritative analysis substantiates the historical veracity of the passages, confirming their fidelity to the actual circumstances in the Mangkunegaran region during the 1930s and offering invaluable insights into the indigenous way of life during that period.

In the novel “Bocah Mangkunegaran,” there is a deliberate emphasis on imparting a comprehensive understanding of local territories to indigenous children. During the 1930s in Java, when transportation options were limited for indigenous communities, their exposure to different regions was constrained. Consequently, indigenous children often had a limited awareness of their own territorial boundaries. To bridge this knowledge gap, the novel provides explicit, region-specific information, accompanied by detailed maps and illustrations. The author, Jasawidagda, takes great care in depicting the areas surrounding Vorstenlanden, underlining the abundant natural resources within these regions. This knowledge assumes critical importance as indigenous territories are frequently subjected to disputes, with powerful entities, including colonialists, asserting claims over these lands. By accentuating the significance of these territories and the imperative of safeguarding them, the novel imparts a profound sense of belonging to its young readers and cultivates an increasing awareness of the importance of preserving their local lands. Through territorial education, the novel strategically sows the seeds of resistance against colonial forces, fostering a heightened appreciation for and dedication to the protection of their indigenous territories.

4.5. Scouting education (Padvinder)

In the novel “Bocah Mangkunegaran,” there is a dedicated chapter titled “Padvinder” that explores the concept of scouting. Additionally, the writer incorporates elements of scouting sporadically throughout other chapters. For instance, during events such as the inauguration of a monument or the opening of a football match attended by Mangkunagara VII, the scouting group is present to accompany the king. Jasawidagda, as the author, intends to provide readers with an understanding of the aims and objectives of scouting.

Scouting aims to raise awareness among the younger generation about the injustices faced by the people. They are taught to be prepared to assist the common people. Scouting is envisioned as one of the avenues for youth to participate in the struggle against the colonialists. The following excerpt from the novel describes the responsibilities of the scouting group.

Javanese text:

Para padpindêr dituntuni nindakake pagawean warna-warna, supaya pêcah nalare, wêruh ing bênêr, wêruh tatakrama, lan patrap warna-warna kanggo sarana têtulung wong liya. Para padpindêr tansah diprêdi bêciking kalakuane. Iku ora mung mandhêg ana ing pitutur bae, kudu ngêcakake têmênan. Akèh bangêt kêtatalane, kaya ta: wis tau jam siji awan ana omah kobong, rame swarane titir. Para padpindêr lagi bae budhal saka pamulangan, lali luwene, padha mlayu tandang panggonan sing kobongan, ngrewangi golèk banyu sapêpadhane. (Bocah Mangkunegaran, 1937, 108)

Translation:

Padvinders are taught various kinds of skills so that they are smart, able to distinguish between right and wrong, understand manners, and various knowledge that is used to help others. Padvinders need to behave. The behavior does not just stop at speech, but must be applied in everyday life. There are many roles of the padvinder, such as: once at one in the afternoon there was a fire, a lot of people making loud clang, a warning sign of danger. The padvinders had just finished training, they ignored their hunger and ran to the location of the fire to help, they helped to find water and made every effort to put out the fire. (Mangkunegaran Boy, 1937, 108)

Javanese text:

Ana padpindêr esuk-esuk mangkat sakolah. Nalika kuwi mêntas udan, blumbang-blumbang kêbak banyu. Padpindêr mau wêruh bocah kêcêmplung, glagêpan ana blumbang, gèk kalêlêb, gèk mancungul. Ora sarănta padpindêr mau banjur anggêbyur ing blumbang nglangèni bocah mau. Klakon bocahe slamêt, andadèkake bungahe wong tuwane. Cêkake akèh bangêt tindake padpindêr atêtulung ing liyan. Ngajèni bangêt marang titah sing luwih ringkih, kaya ta: kewan cilik-cilik. Kêpêthuk wong wadon utawa kaki-kaki, enggal nyimpangi. Trêkadhang nuntun wong picak. Saya yèn mung ditakoni ngêndi omahe si anu, dalane mêtu ngêndi. Dhangan bangêt anuduhake, malah yèn prêlu banjur ngêtêrake. (Bocah Mangkunegaran, 1937, 108)

Translation: