Abstract

This study reviews the implications of the 2014 reporting regulation for public higher education institutions (PHEIs) in South Africa. Guided by the monitoring and evaluation logical framework model and the theory of change, the research assesses the alignment between the regulation’s outcomes and practical implementation. Employing a Document Analysis methodology, the study examines relevant policy documents, institutional reports, and literature to uncover the link between planned interventions and academic success outcomes within reporting timelines. The study highlights a significant research gap regarding the feasibility of achieving desired improvements within specified timeframes. The proposed recommendation for a strategic six-year plan, coupled with synchronized reporting cycles, offers a structured approach for realistic academic intervention impact evaluation.

1. Introduction

1.1. Preamble

This study is a reflection of the reporting implications of the 2014 regulation for reporting for public higher education institutions (PHEI) in South Africa. This new regulation is designed to improve efficiency, transparency, and accountability in the governance and management of PHEIs in South Africa (Department of Higher Education & Training, Citation2014). While these are well-intended outcomes of the 2014 regulation, this paper ponders the practicality of some of the metrics for assessment of intended outcomes, especially in consideration of timeframes. For instance, from the theoretical perspective of best practices in monitoring and evaluation, it may not be feasible to expect that, within a reporting year, interventions for improvement in students’ success rates lead to substantial improvement in graduation rates within the same reporting year.

The study offers an illustrative examination of the reporting requisites associated with the teaching development grant (TDG). The TDG constitutes earmaked grants allocated to South African PHEIs by the Department of Higher Education and Training (DHET). It serves to facilitate enhancements and capacity development in teaching and learning. While the TDG was succeeded by the university capacity development grant (UCDG) in 2018, it is noteworthy that the foundational objectives and reporting principles have not changed as demonstrated by the ministerial statement on the implementation of the university capacity development programme (Department of Higher Education & Training, Citation2020).

This study is driven by the question of whether the 2014 regulation for reporting by PHEIs in South Africa is fully designed to produce the intended outcomes of improved efficiency, transparency, and accountability. This question was further divided into two sub-questions:

Does the 2014 reporting regulation adequately account for the logical link between interventions and respective result levels following monitoring and evaluation of best practices?

How can planning and reporting at PHEIs be improved with respect to setting realistic performance assessment metrics?

By providing answers to the research questions, the following objectives were sought.

To assess the adequacy of the 2014 regulation for reporting by PHEIs in terms of provision, particularly regarding the effectiveness of recommended metrics of accountability.

To assess the conformity reporting principles of the 2014 regulation with best practices in monitoring and evaluation.

To illustrate possible gaps in the use of certain student enrolment metrics for measuring academic development interventions, particularly with respect to the achievability of respective targets within reporting timelines.

The need for an effective planning and reporting framework for PHEIs is not only necessitated by accountability requirements for the huge state funding investment in PHEIs but also because of the unambiguous strategic development role of PHEIs in the production of knowledge and capable graduates for economic growth (Etzkowitz & Leydesdorff, Citation2000).

In the current national development plan (NDP-2030), the government of South Africa emphasized the strategic importance of the education sector in achieving sustainable development. Therefore, the NDP-2030 has set out striving development targets for the higher education sector, including production of 30,000 artisans per year, increasing participation rates in further education and training colleges to 25%, creating additional learning opportunities for students per year, increasing university science and mathematics entrants to 450,000 by 2030, increasing annual graduation rates to more than 25% by 2030, increasing participation rates for university enrolment to more than 30%, and production of more than 100 doctoral graduates per million per year by 2030 (South African Government, Citation2012). The achievement of these ambitious outcomes calls for an effective accountability and monitoring mechanism for year-on-year performance assessments.

1.2. Significance of the study

This study addresses a significant research gap by examining the practical implications of the 2014 reporting regulation for public higher education institutions (PHEIs) in South Africa. While the regulation aims to enhance efficiency, transparency, and accountability, there exists a gap in understanding the feasibility of achieving these outcomes within the stipulated timeframes. The study uniquely focuses on the realistic alignment between interventions and expected academic outcomes. This study introduces innovation by integrating theoretical best practices in monitoring and evaluation with the practical constraints of the 2014 reporting regulation.

The study’s relevance lies in its potential to inform policy makers and PHEIs in South Africa, by critically evaluating the regulation’s alignment with practical timelines. The study offers insights that can enhance the effectiveness of accountability mechanisms. As the nation pursues ambitious development targets in higher education, the study’s findings can contribute to more feasible planning and policy implementation, aligning reporting measures with the goals of economic growth and knowledge production.

1.3. Research approach

This study employs the document analysis research methodology to investigate the reporting implications of the 2014 regulation for public higher education institutions (PHEIs) in South Africa. According to Bowen (Citation2009), document analysis is a structured process for examining or assessing various types of documents, including both printed and electronic materials (computer-based and Internet-transmitted). Similar to other qualitative research analytical methods, this approach mandates a careful examination and interpretation of data to uncover meaning, attain comprehension, and construct empirical knowledge.

Document analysis is a time-efficient and cost-effective qualitative research method that prioritizes data selection over collection, minimizing the required time investment. The accessibility of public domain documents contributes to its appeal, providing a rich repository of data. However, document analysis faces challenges related to potential insufficient detail and low retrievability, especially within organizational contexts. Documents, not originally intended for research, may lack the depth required to comprehensively address specific research questions. The limitations include the potential for biased selectivity of documents, raising considerations about the representativeness of available documents. These drawbacks underscore the need for researchers to carefully weigh the efficiency and cost-effectiveness of document analysis against its potential limitations, particularly when seeking comprehensive and detailed insights (Bowen, Citation2009).

In the context of this study, document analysis is employed as a method involving a systematic review and interpretation of a diverse array of relevant documents. This comprehensive approach encompasses an in-depth examination of not only the 2014 reporting regulation and associated policy documents but also extends to include institutional reports, academic literature on monitoring and evaluation, and pertinent works within the field of higher education.

The rationale behind choosing document analysis lies in its suitability for assessing the alignment between the intended outcomes of the 2014 reporting regulations, specifically, its objectives of fostering efficiency, transparency, and accountability and the practicality of the recommended metrics within defined timeframes. By employing document analysis, the research aims to facilitate a nuanced exploration of the regulation’s evolution, providing not only a detailed understanding of its contextual intricacies but also shedding light on its implementation within the broader framework of South African higher education.

Through a critical scrutiny of policy documents, institutional reports, and related literature, document analysis emerges as a tool for unearthing potential discrepancies between theoretical objectives and practical realities. This approach not only contributes to a robust understanding of the regulatory landscape but also offers valuable insights into the gaps that may exist between policy intentions and their actual implementation in the dynamic context of South African higher education.

1.4. The public higher education system and the New Public Management

New Public Management (NPM) emerged in the 1980s and 1990s as a management philosophy emphasizing efficiency, accountability, and market orientation in public service delivery. Its influence on universities is substantial, shaping decision-making processes through the promotion of performance metrics and cost-benefit analysis. This market-oriented approach aims to enhance the efficiency and accountability of universities by redirecting focus towards research, innovation, and commercialization, potentially impacting traditional teaching and learning activities.

Enthusiasts of NPM argue for its potential to improve efficiency and accountability in public institutions. Scholars and practitioners contend that applying market-oriented and business principles can lead to cost reduction and improved quality. However, the concept of the ‘middle aging of NPM’, as discussed by Hood and Peters (Citation2004), acknowledges limitations. The initial promise of enhanced efficiency and accountability has not universally materialized, prompting an evolving awareness that NPM may not be a one-size-fits-all solution, necessitating consideration of alternative governance and management approaches in specific contexts such as universities.

According to Thiel and Leeuw (Citation2002), performance measurement in the public sector may lead to unintended consequences such as organizational inflexibility, narrow focus neglecting important aspects, suboptimal decisions favouring individual units over the organization, and potential manipulation of performance metrics for self-enhancement. These unintended consequences can seriously undermine the effectiveness of performance measurement in the public sector.

Critics, on the other hand, assert that NPM has significantly transformed universities, emphasizing marketization, competition, and performance measurement. This transformation has shifted focus from universities’ core functions—teaching, learning, research, and community engagement—towards a narrower emphasis on efficiency, productivity, and commercialization. Boughey and McKenna (Citation2021) argue that this shift may compromise the quality of higher education by diverting attention from teaching and learning and diminishing the academic autonomy of universities.

While NPM garners both support and criticism in university management, a balanced perspective is crucial. The complexity of university governance and management may require a nuanced hybrid model, incorporating positive aspects of NPM while preserving traditional university values.

Further research is needed to investigate the impact of NPM on the quality of higher education. Building on the arguments presented by enthusiasts as well as critics of NPM and provide specific and concrete evidence of how a market-oriented approach may affect teaching, learning, and research quality in universities.

1.5. Background

In South Africa, reporting regulations for public higher education institutions are part of a broader movement towards the implementation of New Public Management (NPM) principles in the public sector. NPM emphasizes efficiency, accountability, and market orientation, and these principles are reflected in the reporting regulations for public higher education institutions in South Africa.

Reporting regulations require public higher education institutions to produce annual reports that detail their financial performance, including revenue and expenses, as well as their performance against key performance indicators (KPIs) related to their core mission and operations. KPIs may include measures of student enrolment, graduation rates, research output, and funding received from external sources (Department of Higher Education & Training, Citation2014).

Reporting regulations are intended to increase the accountability and transparency of public higher education institutions and provide stakeholders with information about the performance of these institutions. This information can be used by the government and other stakeholders to make informed decisions about the allocation of resources and improve the quality of higher education in South Africa. In June 2014, the Minister of the DHET published new reporting regulations for public higher education institutions (PHEI) in accordance with the Higher Education Act, 1997. The 2014 regulations replaced the 2007 regulations for annual reporting by PHEIs in South Africa.

PHEIs are required in the 2014 regulation to prepare and submit a strategic plan; they are also required to prepare and submit an annual performance plan (APP) with clear linkages to the strategic plan. Therefore, the APP is expected to cover annual planning and budgeting, which must be aligned to achieve a strategic plan with a core set of measurable indicators to monitor institutional performance. Cash flow projections of revenue and expenditure for three years are also required (Department of Higher Education & Training, Citation2014).

The reporting aspect is the main focus of this study, as PHEIs are required to prepare and submit annual mid-year performance reports due to submission to DHET by the end of November of the reporting year (year n). The mid-year report is expected to provide progress on predetermined objectives for the current year n. The report is expected to indicate progress up to 30th June of the current year n on enrolment targets as well as progress up to June 30 of year n on financials with respect to budget as in the APP. The council must approve the mid-year report (Department of Higher Education & Training, Citation2014).

The annual report provides a complete assessment of the predetermined objectives for the previous year n-1. The report must include evaluation up to December 31 on enrolment targets for year n-1, as well as evaluation up to December 31 on financials for year n-1. Additional reporting requirements include council statement on sustainability, report of audit committee, report on transformation, report of independent auditor on annual report, list of council members and constituencies, and finally, list of office bearers of council. These reports must be approved by the council and signed by its chairperson and vice chancellor. The annual report of year n-1 is due to submission to the DHET on June 30 of year n (Department of Higher Education & Training, Citation2014).

The main difference between the old regulations is that they only required an annual report. The old regulations did not require an APP with a sector-wide uniform core set of indicators. The old regulations did not require a mid-year report or a strict alignment of plans to budget. More reports/statements from the council are required than in the old regulations. is a compilation of the 12 reports that form the annual report of the DHET required by PHEIs.

Table 1. Annual reporting requirement of DHET.

In summary, the new system is intended for improved accountability, effective spending of public funds, and the measurability of returns on investment in higher education. The new regulation is also designed to ensure the implementation of institutional strategic plans such that the existence of strategic plans would not be for mere compliance but rather actionable documents. The new regulation is designed to enhance the proactive mitigation of risks, particularly financial risks, as one of the requirements is the cash flow projections of revenue and expenditure for three years (Department of Higher Education & Training, Citation2014). This compels management of PHEIs to be conscious of the financial health of the respective PHEIs.

1.6. The reporting templates for annual performance assessment report of the APP

One of the challenges in the PHEIs sector was the lack of clear indication from DHET on the reporting template for fulfilling the reporting demands of the 12 reports required by DHET for annual and mid-year reports of PHEIs. DHET recognized the importance of a standard approach for reporting templates for the purposes of annual/mid-year reports and came up with the following templates (Department of Higher Education & Training, Citation2015).

1.6.1. Reporting on enrolments

Enrolment indicators are based on approved enrolment plans of PHEIs and evaluated by the DHET under four broad strands of Access, Success, Efficiency and Research Output. Standard key performance indicators (KPIs) are applied within the PHEI sector for each strand of enrolment performance, as shown in (Department of Higher Education & Training, Citation2015).

Table 2. Enrolment targets in APP for year n.

1.6.2. Reporting for earmarked grants

Earmarked grants within the PHEIs funding framework are special grants that are ring-fenced for improvement of specific aspects of institutional concern, such as improvement of teaching and learning, increased access to higher education with success, development of certain critical skills, and infrastructure development. shows the recommended template for reporting earmarked grants (Department of Higher Education & Training, Citation2015).

Table 3. Earmarked grants for year n.

The teaching development grant (TDG) is of greater emphasis in this study for illustrating the conceptual perspectives of monitoring and evaluation implications of the new reporting scheme. TDG is based on the rationale that universities that currently have lower success rates with respect to planned enrolments need higher levels of funding to improve their performance (Department of Higher Education & Training, Citation2013). Therefore, the TDG is expected to be used by PHEIs in various academic development initiatives, such as the professional development of academics, curriculum development, and various aspects of student support. A monitoring and evaluation framework that provides a clear linkage between TDG-based projects, for instance, and intended improvement of related access/success indicators is important for a proper understanding of the contribution of the TDG. The same principle applies to other areas of funding and investment in the system.

1.6.4. Revenue and expenditure reporting

is a template for reporting the years cash flow projections of revenue and expenditure. This ensures a continuous insight into the financial health of the respective institutions.

Table 4. Cash flow projections of revenue and expenditure (three years).

Reporting templates for institutional risk reporting, as well as long-term capital expenditure on major capital projects planned over an extended period, were also provided by Department of Higher Education and Training (Citation2015).

In section one of this paper, background information is presented to acquaint the reader with the reporting requirements of the 2014 reporting regulation for PHEIs in South Africa. The following section presents the conceptual aspects of the monitoring and evaluation implications of the new regulations.

2. Monitoring and evaluation theoretical perspectives

2.1. Monitoring and evaluation of educational interventions at public institutions in South Africa

The collapse of apartheid in South Africa in 1994 brought about much-needed reforms in the education sector. The National Plan for Higher Education (Department of Education, Citation2001) put forward measures to redress past inequalities and transform the higher education system. The new measures are intended to provide increased access to higher education and to produce graduates with the skills necessary for the development of the country. The higher education plan also made recommendations for building a high-level research capacity to address the research and knowledge needs of South Africa.

The expansion of access to higher education has necessitated substantial resource investments in the system. The academic autonomy of universities notwithstanding, PHEIs as public institutions are required to comply with public accountability mechanisms of government, such as the requirements of the national treasury for the management of public funds and the principles of the government-wide monitoring and evaluation system (GWMES).

GWMES was approved by the government of South Africa in 2005 to provide a harmonized framework for monitoring and evaluation of the public sector in South Africa. All government departments and public institutions are required to conform to the principles of GWMES as a mechanism for the management of development and public accountability.

2.2. Monitoring and evaluation of educational interventions

Monitoring implies routine tracking and reporting of performance against set targets by collection/collation and analysis of performance data. An evaluation is a periodic assessment of results that can be attributed to mapped resources and activities (Ile et al., Citation2012).

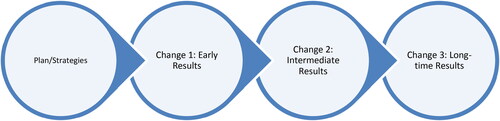

Conceptually, GWMES is guided by the Logical Framework (LF) methodology of the M&E design. The logical framework is a logical approach to designing, planning, executing, and assessing development initiatives that encourages stakeholders to consider the relationships between available resources, planned activities, and desired development destinations.

LF is based on the logic that inputs/resources in the system facilitate activities, the activity processes put-out outputs, the outputs lead to desired outcomes, and the outcomes produce impacts with the highest result level in the hierarchy (Ile et al., Citation2012).

The logical framework model is presented in . Each targeted level in the hierarchy is the result. It is important to understand the desired results at each stage of the development process.

Figure 1. Result hierarchy of the M&E logical framework model.

2.2.1. The theory of change

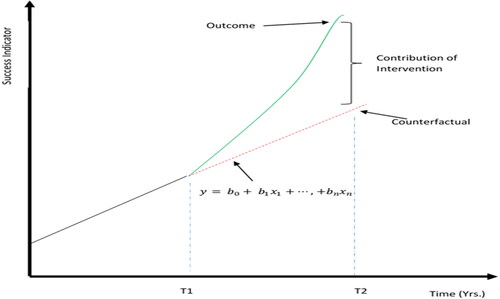

The theory of change in M&E enables practitioners to design plans for development with an embedded understanding of the steps that are linked to respective result levels as the project matures. According to Weiss (Citation1995), ‘theory of change is a way to describe the set of assumptions that explain both the mini-steps that lead to the long term goal and the connections between policy or programme activities and results that occur at each step of the way.’

The theory of change is illustrated in . This theory aids evaluation practitioners in correctly mapping results to the respective phases of development intervention. In some cases, the link between high-level results (outcomes/impact) and the mini-steps required are not clear. This makes the task of evaluating complex initiatives challenging, and the causal relationship between outcomes and interventions may not be logically explainable in such instances. For instance, when reporting on the Teaching Development Grant (TDG), it may not be logical to claim that the TDG for a particular year has led to an improvement in graduation rates in the same year because this would mean attributing a long-term indicator of change to the wrong phase of change.

2.2.2. Analysis of contribution and counterfactual

In order to validate investment in intervention projects for the improvement of certain indicators such as students’ success rates, PHEIs should be able to compare the observed results to those that would have been expected if the intervention had not been implemented. This is known as the analysis of counterfactuals (European Commission, Citation2013).

Analysis of counterfactual is more challenging with qualitative indicators, as the quantification of effects may not be feasible in such cases. Luckily, DHET has provided set of Higher Education Management Information System (HEMIS) indicators that comply with the SMART (Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Realistic, Timely) principles.

is a conceptual illustration of the contribution analysis of an intervention by quantifying the effects of the intervention through a comparison of the outcome and the counterfactual. In , intervention is implemented at time T1, and the outcome of the intervention matures at time T2; if there was no intervention, the trend of the success indicator would have been expected to continue in line with the historical regression equation as projected. The intervention brought about a change in the trend leading to the outcome. The actual contribution of the intervention is not the absolute value of the outcome at T2 but the difference between the outcome and the counterfactual, as illustrated in .

3. Monitoring and evaluation implications for reporting on performance AT PHEIS

Recent research exemplified by studies like Nkonki-Mandleni (Citation2021) underscores the persistent challenges entailed in effectively implementing monitoring and evaluation within the public higher education institutions (PHEIs) sector. This body of work highlights the ongoing complexities and difficulties associated with ensuring successful monitoring and evaluation processes in PHEIs. Reporting on the outcomes of teaching and learning development brought about by the teaching development grant (TDG) is used in this paper to illustrate the M&E considerations due to the 2014 regulations for reporting.

As stated earlier, TDG is based on the rationale that universities that currently have lower success rates with respect to planned enrolments need earmarked teaching development funds for development of teaching to improve their performance (Department of Higher Education & Training, Citation2013). Therefore, the TDG is expected to be used by PHEIs in various academic development initiatives, such as the professional development of academics, curriculum development, and various aspects of student support.

The template provided by DHET, as shown in for reporting on earmarked funding, provides PHEIs with allocated amounts for TDG, Expenditure, Indicator of Success, and a column for explanation of reasons for variation from target (Department of Higher Education & Training, Citation2015). It is not clear what level of indicator of change is required in this report to measure the contribution of the TDG in terms of the monitoring and evaluation hierarchy of results.

3.1. Mapping of result hierarchy

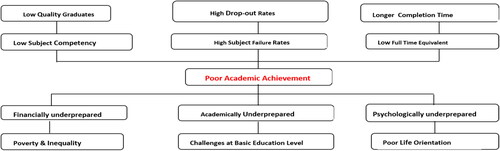

The TGD is intended to sponsor interventions to improve the success rates. depicts the hierarchal result chain for such funding initiatives, assuming that success rates are mainly driven by the pedagogical competency of academics.

Figure 4. Hieratical result chain due to the TDG.

shows the respective maturity timeframes for the resulting levels. Using the analogy of the M&E logical framework, success rates can be categorized as outcome indicators. In terms of the theory of change, a change in success rates as a result of intended intervention could realistically be expected in the intermediate-to long-term period. Therefore, it may not be the best practice to expect that intervention projects for a specific year may yield anticipated outcomes in the same year, following the principles of the theory of change. The reasoning behind this could be further explained by a deeper analysis of the underlying causes of the problem that the intervention is intended to solve.

The TDG is intended to reduce the problem of poor academic achievement of students at a particular PHEI. This problem is multidimensional, with layers of possible underlying causes, as shown in .

Figure 5. Problem analysis.

illustrates that poor academic achievement could be attributable to various dimensions of undergraduate students: financial, academic, and psychological (Council on Higher Education, Citation2013). These dimensions of underpreparedness may further be attributable to other underlying larger societal factors, such as poverty, challenges in basic education, and life orientation. Again, poor academic achievement also has various dimensions of its manifestation, as shown in . Therefore, the PHEI must have a clear understanding of the problem by properly diagnosing the various dimensions of the root causes and the various possible forms of manifestations.

This would ensure better development of intervention mechanisms that are correctly aligned to the respective root causes of the problem and a realistic timeframe and hierarchy of expected results from interventions.

3.2. Planning and reporting framework

The Department of Higher Education and Training provided guidelines for planning and reporting based on 2014 regulations. present summaries of the planning and reporting requirements. However, these guidelines are high-level; therefore, the onus is on each PHEI to seamlessly align these high-level items with operational items in a coherent manner.

In , a brief planning and reporting matrix is presented to elucidate planning and reporting edicts based on monitoring and evaluation principles, particularly the theory of change and result hierarchy. Using reporting on the TDG as an example, illustrates the alignment of result chains from low-level planning and reporting to high-level institutional planning and reporting.

Table 5. Result-based planning & reporting framework.

The first row of contains examples of important variables and considerations for planning and reporting from monitoring and evaluation perspectives. Expected results would have to be feasible and realistic, and KPIs need to conform to the SMART principles and properly align to the correct result hierarchy. It should be clear whether the anticipated change would mature early/immediate, intermediate, or long-term, according to the theory of change. This would inform the realistic setting of targets in the APP and strategic plan, as well as the respective evaluation/assessment reports.

Following the illustrations in , the input result level is the funding value of the TGD, which funds operational activity. This could be considered an early change, and the planning document should be an APP. Reporting on funding should be more frequent, and it is recommended to report quarterly for proper accountability. Summary progress reports on the use of the TDG should also be featured in the mid-year report on the APP as well as the annual assessment report on the APP as prescribed by DHET. The next level of results is expected from operational activities leading to lecturer training. This could also be considered an early result, as most training could be in the form of workshops, conferences, and/or short courses. These operational activities should be documented in departmental/divisional plans, and progress reports should be sent quarterly to the respective line managers within the PHEI. The next result level is the output, which is the actual measurable number of lecturers trained with reference to the set target in the APP, which is an intermediate result.

The expected outcome of the funding, activities, and training is the improvement in students’ academic success rates against targets set in the APP, which is again considered an intermediate result. The impact of improvements in graduation rates is driven by the overall chain of events, as described above. The timing of the framework of PHEIs would be considered a long-term result because graduation outcomes are driven by cumulative outcomes of usually three years or more of academic engagement following cycles of three-year enrolment planning.

4. Conclusion and recommendations

The ever-changing landscape of public higher education demands constant monitoring and adaptation of policies that govern outcomes and ensure accountability. In response, South Africa’s Department of Higher Education and Training (DHET) implemented a set of reporting regulations in 2014 to enhance transparency and accountability within public higher education institutions (PHEIs). While these regulations have made commendable progress in achieving their goals, concerns regarding reporting burdens and the need for a more balanced and meaningful reporting approach have emerged. This necessitates a thorough re-evaluation of the existing framework.

The 2014 regulations marked a significant change, requiring PHEIs to develop intricate annual performance plans aligned with strategic blueprints. This underscores the crucial link between planning and budget allocation and emphasizes the need for their harmonious integration. Additionally, the regulations mandate the submission of mid-year and annual performance reports, necessitating deeper analysis of governance through augmented Council statements.

By positioning the new reporting regulations within the context of monitoring and evaluation models, particularly the logical framework model and theory of change, this study illuminates the logical progression of outcome chains and traces the impact of planned interventions on student success indicators. This structured approach offers a nuanced understanding of how planned development measures influence student achievement.

Based on these findings, the study recommends a forward-looking planning approach that adopts a six-year strategic plan encompassing two enrolment cycles. This extended timeframe allows institutions to comprehensively implement and evaluate the effectiveness of strategic initiatives. Furthermore, the study proposes implementing impact evaluation reports at the end of each six-year cycle to provide a longitudinal perspective on the enduring effects of strategic initiatives. Alongside these reports, annual and mid-year reports serve as vital monitoring tools, enabling continuous tracking of progress towards achieving PHEIs’ strategic plans.

Cultivating a culture of collaboration, cooperation, and capacity building within the higher education landscape is crucial for the success of this proposed approach. The study emphasizes that such a cultural shift is vital for fostering shared insights and best practices across institutions. By embedding this collaborative ethos into the planning and reporting processes, a harmonized and unified approach to addressing challenges and pursuing opportunities within the higher education sector can be established.

Ultimately, the aim of this comprehensive approach is to maximize both academic and social impact, contributing significantly to the broader goals of the higher education sector and the sustainable development of South Africa. By adopting a multi-year strategic planning framework and incorporating both annual evaluations and six-year impact evaluations, institutions can ensure a more deliberate and thoughtful approach to addressing challenges and leveraging opportunities. This, in turn, fosters a robust culture of accountability and continuous improvement.

This study serves as a call for a meticulous re-examination of reporting regulations and planning frameworks within South Africa’s public higher education institutions. By strategically integrating evaluation models and adopting a forward-looking planning horizon, institutions can not only meet the stipulated reporting expectations but also foster a culture of innovation, collaboration, and adaptability. This approach paves the way for a resilient and responsive higher education landscape in South Africa, one that effectively addresses the evolving needs of students, society, and the broader educational ecosystem.

BIOGRAPHY.docx

Download MS Word (23.6 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Remigius C. Nnadozie

R. C. Nnadozie currently holds the position of Director for Institutional Research, Planning, and Quality Promotion at Rhodes University in South Africa. Prior to his role at Rhodes University, he served at Mangosuthu University of Technology (MUT), where his responsibilities included overseeing the monitoring and evaluation of the University’s Strategic and Operational Plans. Additionally, he played a pivotal role in managing institutional research and higher management information systems (HEMIS) at MUT. Before joining MUT, Dr. Nnadozie served as a senior academic development coordinator at the University of Johannesburg, showcasing his expertise in academic development. His career has also encompassed roles as a lecturer at MUT and a researcher at the Human Sciences Research Council (HSRC), where he contributed to scholarly research endeavors. In 2022, Dr. Nnadozie lent his expertise as an audit panel member for the Council on Higher Education (CHE) national audits. Currently, he serves as a Member of the Quality Assurance of Occupational Qualifications Committee (QAOQC) at the South African Quality Council for Trades and Occupations (QCTO). Dr. Nnadozie’s academic background is comprehensive, spanning Applied Mathematics, Statistics, Information Systems, and Science Education. This diverse academic foundation underscores his multidisciplinary approach to research, planning and problem solving.

References

- Boughey, C., & McKenna, S. (2021). Understanding higher education: Alternative perspectives. South Africa.

- Bowen, G. A. (2009). Document analysis as a qualitative research method. Qualitative Research Journal, 9(2), 27–40. https://doi.org/10.3316/QRJ0902027

- Council on Higher Education. (2013). A proposal for undergraduate curriculum reform in South Africa: The case for a flexible curriculum structure. Council on Higher Education.

- Department of Education. (2001). The national plan for higher education. Department of Education.

- Department of Higher Education and Training. (2013). Report of the ministerial committee for the review of the funding of Universities. Department of Higher Education & Training.

- Department of Higher Education and Training. (2014). Regulations for reporting by public higher education institutions in South Africa. Department of Higher Education & Training.

- Department of Higher Education and Training. (2015). Planning and reporting template for 2014 regulations for reporting by public higher education institutions in South Africa. Department of Higher Education & Training.

- Department of Higher Education and Training. (2020). Ministerial statement on the implementation of the university capacity development programme. Department of Higher Education & Training.

- Donaldson, S. I. (2007). Program theory-driven evaluation science. Lawrence.

- European Commission. (2013). Evaluation sourcebook. European Commission.

- Etzkowitz, H., & Leydesdorff, L. (2000). The dynamics of innovation: From national systems and 'Mode 2' to a triple helix of university-industry-government relations. Research Policy, 29(2), 109–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0048-7333(99)00055-4

- Hood, C., & Peters, G. (2004). The middle aging of new public management: Into the age of paradox? Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 14(3), 267–282. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muh019

- Ile, I., Eresia-Eke, C., & Allen-Ile, C. (2012). Monitoring and evaluation of policies, programmes and projects. Van Schaik.

- Nkonki-Mandleni, B. (2021). Monitoring and evaluation for university–community impact in driving transformation agenda. South African Journal of Higher Education, 37(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.20853/37-1-5679

- South Africa Government. (2007). Policy framework for government-wide monitoring and evaluation. The Presidency.

- South African Government. (2012). National development plan 2030. The Presidency.

- Thiel, S., & Leeuw, F. L. (2002). The performance paradox in the public sector. Public Performance & Management Review, 25(3), 267–281. https://doi.org/10.2307/3381236

- Weiss, C. H. (1995). Nothing as practical as good theory: Exploring theory-based evaluation for comprehensive community initiatives for children and families. In J. Connell, A. Kubisch, L. B. Schorr, & C. H. Weiss (Eds.), New approaches to evaluating community initiatives: Concepts, methods, and contexts (pp. 65–92). The Aspen Institute.