Abstract

Thanks to the continuous development of artificial intelligence (AI), more and more tools are available to help students to practice their language skills. Nowadays, there are various ways of using AI-driven technology in the process of language learning, one example is the use of chatbots. This pilot study aims to investigate the impact of the conversational chatbot on learning a foreign language and to understand learners’ perceptions of using a chatbot as a complementary language tool. Altogether 58 university students learning English as an applied foreign language with B2 and C1 levels of English proficiency participated in the experiment during the period of one month. The qualitative results show a significant improvement in the student’s language skills thanks to the use of smart AI. Furthermore, the questionnaire survey reveals positive perceptions of this additional learning tool. Therefore, the findings indicate that working with this AI-driven technology can contribute to improving language skills and its perceived usefulness in the process of second language acquisition at the university level.

REVIEWING EDITOR:

1. Introduction

In the era of rapid technological advancement, artificial intelligence (AI) has emerged as a transformative force across different domains, including education. As the younger generation grows up immersed in technology, the integration of AI-driven tools into learning environments is becoming increasingly common (Bean, Citation2018). AI-driven technology is poised to serve as the basic building block of the Fifth Industrial Revolution, revolutionizing the way we teach and learn. One important area in which AI is making significant progress is foreign language (FL) learning (Ziatdinov et al., Citation2024) which, according to Golic (Citation2019), offers various opportunities to improve the advancements, focusing specifically on the use of conversational chatbots to enhance language learning outcomes, an area with limited empirical research.

AI-driven technology holds great promise for addressing the unique challenges associated with FL learning. One of them is the diversity of learners’ learning styles and needs. AI offers the potential for personalized instruction tailored to the preferences and proficiency levels of individual learners, thereby increasing the effectiveness of language learning programs (Klimova et al., Citation2024; Zhang et al., Citation2023). In addition, AI facilitates the automation of performance assessments, allowing educators to gain insight into student progress and more effectively identify areas for improvement. (Fitria, Citation2021; Kim et al., Citation2022; Kuhail et al., Citation2022).

During the last few years, AI has drastically improved different language technologies. In Speech Technology, for instance, the machines have already scored super-human performance. These advancements are also present in several Natural Language Processing tasks such as in Machine Translation, Text Simplification, and Grammatical Error Detection/Correction. These improvements have led to the development of practical applications that are also vastly utilized in Foreign Language (FL) education (Klimova et al., Citation2023; Schmidt & Strassner, Citation2022). Some examples are explicit language teaching (e.g. Duolingo), writing assistants (e.g. Grammarly), translation (e.g. Google Translate and DeepL), and for conversation practice in chatbots, artificial agents, and social robots (in research; EduBot). These applications are used for the development of different language skills (i.e. speaking, writing skills, reading, and listening). Additionally, recent advancements in AI have enabled the creation of more sophisticated chatbots that can engage in more natural and contextually relevant conversations with users, enhancing their potential for language learning (Belda-Medina & Kokošková, Citation2023). This is especially true for the most recent chatbot – ChatGPT that has been challenging the teaching approaches and learning strategies since its first launch in 2022 (Kalyan, Citation2024).

Chatbots seem to be suitable for the development of student’s communication skills, such as speaking and writing, since chatbots enable immediate interaction with their users (Mageira et al., Citation2022; Yin & Satar, Citation2020) and provide almost instant feedback (Dokukina & Gumanova, Citation2020). Furthermore, chatbots provide additional benefits, such as the opportunity to practice a target foreign language at any time and from anywhere without a need to talk to a native speaker, provided that there is access to a form of personal computer, tablet, or smartphone. Some students also prefer using them because talking to such a virtual agent reduces their anxiety about speaking with a real teacher (Haristiani, Citation2019). In addition, chatbots offer another language learning mechanism, e.g. a broader range of expressions and vocabulary or consistent understandable repetition which humans are unlikely to perform, apart from language teachers (Petrović & Jovanović, Citation2021). As empirical research (Belda-Medina & Calvo-Ferrer, Citation2022) suggests, the use of chatbots in FL education has a positive impact on students’ learning results and perceived usefulness, both of which motivate students to learn a foreign language. However, most studies involving chatbots in language learning are limited to specific settings or focus on particular aspects, leaving gaps in understanding the broader impact of these tools. This study contributes to filling that gap by examining both quantitative outcomes and qualitative perceptions among university students in a FL learning context.

While the integration of AI technology in educational settings offers numerous benefits, including enhanced language learning experiences through chatbots, there are certain drawbacks to consider. One such drawback is the lack of human, face-to-face interaction, which can hinder clarification of issues as chatbots may not always respond in a relevant manner. Additionally, ethical concerns surrounding the transparency of personal data and safety may discourage students from using this technology. Issues of inclusivity may also arise, as some accessible chatbots may not be free of charge, particularly their premium versions, presenting a barrier to access for certain students. These concerns highlight the need for educators to address ethical considerations, such as privacy, surveillance, autonomy, bias, and discrimination, to ensure the responsible and equitable use of AI in education (Akgun & Greenhow, Citation2022; Klimova et al., Citation2023; Schmidt & Strassner, Citation2022).

Overall, as the information provided above maintains, chatbots appear to be useful for FL education. However, research indicates that there is still a lack of empirical research on the use of chatbots in FL education (cf. Belda-Medina & Calvo-Ferrer, Citation2022; Klimova et al., Citation2023). On the basis of the findings described above, there are several research gaps in using chatbots in a foreign language classroom, i.e. a rare effective integration of chatbots into existing educational systems (Baidoo-Anu & Ansah, Citation2023; Montenegro-Rueda et al., Citation2023). In this respect, more examples of best practices should be employed to improve student learning outcomes without diminishing the role of educators (Yu, Citation2024). In addition, the issue of personalization of learning, e.g. meeting student needs and preferences should be considered in depth (Javaid et al., Citation2023). This can be solved by implementing such a chatbot that would tailor learning experiences in real time, adapting to the evolving needs of students to optimize learning outcomes. Finally, evaluation of learning outcomes should be addressed (Essel et al., Citation2024), which would to measure how chatbots impact these outcomes across different subjects and educational levels.

Based on the information from the research studies described above, as well as with the rapid advancement of generative AI, such as ChatGPT, the authors call for a critical evaluation of these new technological tools used for FL educational purposes. They highlight several issues associated with their use, such as providing fast and almost immediate feedback vs. accuracy, reducing anxiety to speak vs. social isolation, making learning more personalized vs. data privacy, or relying immensely on technology vs. a lack of critical thinking. Therefore, there is an urgent need to reflect on these issues and consider and rethink the existing teaching approaches in order to stimulate students to learn a foreign language, as well as to enhance their creative and thinking skills while learning a foreign language.

Therefore, this empirical pilot study aims to bridge these gaps, and more specifically, explore the impact of the conversational chatbot on learning a foreign language and to understand learners’ perceptions of the use of a chatbot as a complementary language learning tool.

To answer the aim of this study, the following research questions were formed:

RQ1: What impact does smart AI-driven technology have on learning a foreign language?

RQ2: What are the learners’ perceptions of using smart AI-driven technology in the process of second language learning?

‘Using AI-driven technology in the process of FL learning can help students expand their language skills’.

2. Methodology

This study used a mixed-methods approach that combined both quantitative and qualitative data collection techniques. Quantitative data were collected through pre-tests and post-tests, which were then analyzed using descriptive statistics. The results gained from pre-tests and post-test provided a baseline to assess improvements in language ability over the study period. Statistically significant differences between the pre-test and post-test results confirmed the impact of the chatbot intervention on language proficiency. The choice of these methods was intended to offer both a general overview of the data and analysis of the experimental outcomes, supporting the replicability of the study. On the other hand, qualitative data was collected from a questionnaire that aimed to capture students’ perceptions of using conversational chatbots as a learning tool. This data was analyzed, interpreted, and categorized to provide insights into the students’ experiences. Different types of data were collected throughout the experiment to facilitate comprehensive analysis and evaluation. This included storing all interactions between users and the chatbot, known as chat logs, which offer valuable insights to improve the performance of the chatbot and understand the language learning process. In addition, responses from pre- and post-testing evaluations were collected to track learning progress over time. In addition, participants provided demographic information such as language proficiency, gender, education, and field of study, which helped to understand how different factors can influence the effectiveness of technology-assisted language learning.

Ethical consideration played a significant role in this study. Data privacy was ensured by implementing strict data protection measures, including access to authorized personnel only and anonymizing personal information to protect participant identities. Informed consent was obtained from all participants, and the study received approval from the Ethics Committee of the University of Hradec Kralove (approval no. 4/2023). The study strictly adhered to GDPR standards to ensure the privacy and protection of participants’ data.

2.1. Research participants

The present pilot study includes a convenience sample of bachelor students from a university in the Czech Republic, mostly studying Informatics and Management. The decision to use the convenience sample was chosen because of the researchers’ dual role as English language teachers at the university, which allowed easy access to students willing to participate in the research. Before the study, all students were given the placement test to find their English proficiency level. Originally, 74 students were tested. They were at different levels of English proficiency, ranging from level B1 to C1 of the Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR). Subsequently, only students with levels B2 and C1 were selected for this experiment. The rationale for choosing these proficiency levels was to ensure a cohort of participants who were sufficiently advanced to engage in meaningful interaction with the chatbot, reducing the risk of misinterpretation due to lower language skills. Focusing on the students with English proficiency levels B2 and C1 ensures a more uniform set of research participants, minimizing variability in language skills for reliable analysis. These proficiency levels correspond to higher-level and advanced language learners who are better prepared to tackle complex language tasks and benefit from interaction with the chatbot. Limiting participants to B2 and C1 levels increases the relevance of the study. Altogether, there were 71 students in both groups. Three students did not finish the experiment for personal reasons, and 10 students did not use the research tool properly or did not use it at all, thus the final number of the research participants was 58. The students were divided into an upper-intermediate group (n1 = 22) and an advanced group (n2 = 36). Their ages ranged from 19 to 21, with a proportion of 78% of males and 22% of females.

2.2. Research procedures

The experiment lasted for four weeks. At the beginning of the research period, the students from both groups were asked to fill in the pre-test on vocabulary and grammar. Consequently, all students were instructed on how to use the research tool, specifically a smart AI chatbot called Alex. The first session was completed directly in the classroom as a familiarization session, in case students had questions about its use. The other sessions were completed outside of the school environment, meaning that the students could work at their own pace. The research participants were supposed to complete three sessions per week. Twice a week, they received notifications in the form of emails so that they did not forget to work with the chatbot. During each session, 1,000 characters had to be reached by the participant to consider it to be completed. Each week, a different topic, such as small talk, TV series, social media, and traveling, was discussed. These topics were tailored to the interests of the students. At the end of the experiment, the post-test was given to the research participants from both groups, which was compared with the pre-test results, to see if using the chatbot helped the students to improve their language skills. The research participants were also asked to complete a qualitative questionnaire that was used to understand the students’ perceptions of the conversational chatbot as an additional learning tool.

Throughout the research period, various strategies were used to engage participants with the chatbot Alex. The chatbot was carefully tailored to meet the specific needs and preferences of participants, supporting a sense of relevance and personalization. Interactive activities, such as engaging conversations on diverse and interesting topics, were integrated to maintain participant interest. Research participants were provided with timely and prompt feedback, which facilitated continuous learning and improvement. In addition, clear and transparent communication regarding the use of participants’ data was maintained, with privacy policies in place to protect participants’ information. Regular updates were provided to keep research participants informed on project progress, which promoted a sense of involvement. In addition, participants were motivated through special points that were added to their end-of-semester evaluation, which encouraged active participation and sustained engagement in the research.

2.3. Research instrument

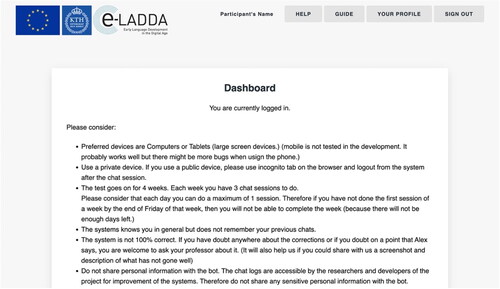

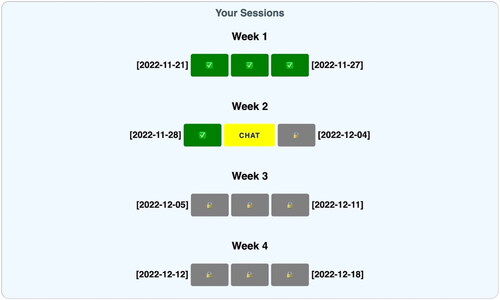

The Alex chatbot is designed for having conversations with learners of English as a second language at different levels of proficiency. This chatbot is a web-based Flask application written with Python and deployed on a private server of the KTH Royal Institute of Technology. The user interface of the chatbot enjoys an intuitive design to deliver the objectives of this experiment including Sign Up/Sign In, Dashboard, Profile, and Chat pages. Upon signing up participants are redirected to the page containing the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) page including the informed consent form for the participants. Later on, the participants could sign in and see their dashboard using their credentials. The dashboard contained some general notices about the experiment (shown in ) and information about the chat sessions that the participants had to finish (shown in ). They were limited to one chat session per day and a maximum of three chats per week to have the same amount of experience with the chatbot among the participants. The chatbot used the GPT-3 (Brown et al., Citation2020) language model for natural language understanding and generation and Gramformer (Bryant et al., Citation2017) and T5 (Rothe et al., Citation2021) for grammatical error detection. The interaction starts with the assistant initiating a dialogue by asking a direct question to the users. The users’ answers are checked through two sophisticated grammar error detection systems to identify and correct any inaccuracies. If errors are detected, the conversation will seamlessly move into a correction phase and offer users various types of feedback for improvement. Users then rate each response as < good > or < bad>, with the initial assignment of feedback types being random. At the time of the research, the project was in the process of crowdsourcing data to refine the underlying model that dictates the timing and nature of providing corrective feedback. In the future, it is envisioned that ongoing machine-learning techniques will be used to tailor this model to each user’s unique learning journey based on their individual experiences (Kamelabad, Citation2022).

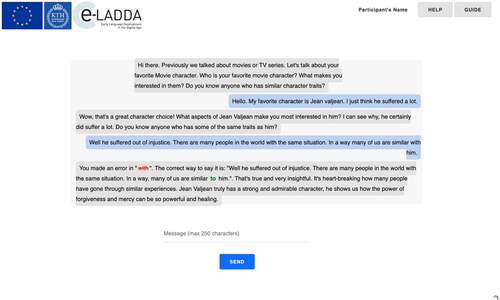

At the beginning of each chat session, Alex greeted the participants and introduced a new topic that they could talk about during that day. The topic of each session was decided beforehand and it was the same for all the participants. But the chats were open domain, and the primary scenario was only the opening. After that, the participants could choose which direction should the conversation go. An example of part of a chat session is shown in . When a user made some mistake, Alex would show them the mistake and the corrections.

3. Results

For this study, a mixed-method approach was chosen. By combining quantitative and qualitative methodologies, the study aims to provide a complex understanding of the impact of conversational chatbots on FL learning. The quantitative approach allows for the systematic measurement of language learning outcomes, examining changes in language proficiency levels before and after the intervention. Statistical analysis allows for the identification of significant improvements in language proficiency, providing empirical evidence of the effectiveness of the chatbot intervention. On the other hand, the qualitative approach digs deeper into learners’ perceptions, attitudes and experiences with the chatbot, offering insights into the nuances of its usefulness and usability. Through the analysis of qualitative data, the study reveals students’ interactions with the chatbot and sheds light on its strengths and limitations. By triangulating the findings from the quantitative and qualitative sections, the research aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of the role of conversational chatbots in improving FL learning and to inform the development of evidence-based pedagogical strategies.

3.1. Quantitative approach to research

Based on the results obtained from the placement tests, it can be concluded that two different groups of students participated in this experiment, specifically, upper-intermediate students (n1 = 22) and students with an advanced level of English (n2 = 36). Both groups, altogether 58 students, used the conversational chatbot in their process of FL learning, in an out-of-school environment. In order to measure the impact of the additional learning tool on FL learning, the post-tests and pre-tests were revealed and the results obtained from them were compared. A comparison of the pre-test and post-test results in the upper-intermediate group is illustrated in below. The results of the advanced group are provided in below. Based on the data from these tables, it can be concluded that both groups of students achieved significantly higher results in the post-tests, i.e. after the smart AI-driven technology intervention than in the pre-tests.

Table 1. Comparison of the pre-test and pos-test results in the upper-intermediate group.

Table 2. Comparison of the pre-test and post-test results in the advanced group.

In addition, an improvement in individuals was assessed. The students’ results in the pre-tests and post-test were compared. Regarding the results of the comparison test, it can be assumed that there were significant differences between the results of individual students in the pre-tests and post-test. As the results attained in the post-test were higher, the findings confirm that the use of the chatbot helped students to expand their language skills and structures, specifically vocabulary and grammar.

Statistical analysis, involving comparison of the pre- and post-test results within each group, was chosen because it allows changes to be examined over time, providing insight into the effectiveness of the intervention. By comparing the average pre- and post-intervention scores, it can be determined whether there was a significant improvement in language proficiency as a result of using the chatbot. The reason for choosing this statistical test lies in its ability to detect differences between two related groups, making it suitable for assessing the impact of the chatbot on students’ language learning outcomes.

Based on the findings provided above, it is clear that the implementation of smart artificial intelligence in the process of FL learning was effective, as both groups, the upper-intermediate and advanced groups, reached better results in the post-tests than in the pre-tests. The results are therefore in line with the hypothesis of this study.

3.2. Qualitative approach to research

The individual statements from the qualitative questionnaire survey were analyzed and divided into six different categories. The first category provides general information on the use of AI-driven technology; the second category deals with students’ perceptions of the usefulness of the chatbot; the third category consists of statements related to ease of use; the fourth category concerns the enjoyment of using smart artificial intelligence in the learning process; the fifth category provides information on students’ preferences in the process of FL learning; and the sixth category portrays advantages and disadvantages of the chatbot, based on the student’s perceptions.

3.2.1. General information

Based on the results of the questionnaire survey, 85% of the students have never used a chatbot other than Alex, which means that for the majority of the students, this was the first experience using this kind of artificial intelligence in the process of FL learning. 58 research participants (100%) worked with Alex three times a week and completed all 12 sessions over a 4-week research period. The findings show that 57% of them preferred working at home and the rest of them decided to work at various places. 60% of the students completed the sessions at different times during the research period, however, 40% of them used the chatbot in the evening before going to bed. The findings also indicate that chatting with Alex took from 5 to 20 minutes, which was perceived positively. Only 3% of the research participants reported that completing one session took more than 20 minutes. All students worked individually, however, 43% of the research participants admitted the use of a machine translation application (MTA) when having a chat with Alex. MTA was normally used when unfamiliar words and phrases occurred in the text.

3.2.2. Perceived usefulness

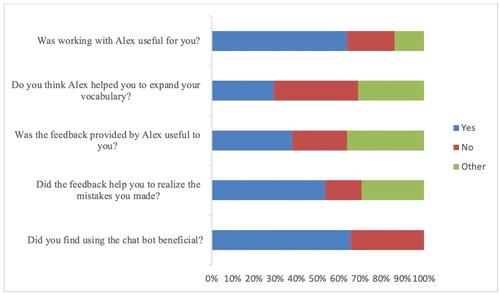

Regarding the students’ perceptions of the usefulness of AI (), 64% of the research participants found chatting with Alex useful, mainly due to the possibility to practice their writing skills, conversational skills, and gaining new knowledge through interesting topics. One of the participants expressed, ‘Chatting with Alex was really helpful for me to practice my writing skills. I enjoyed the conversations and learned a lot from them’. Despite the high level of positive perceptions on the usefulness of Alex, as many as 22% of the students did not find using the chatbot useful because, according to them, it did not work properly and it often made mistakes. As one of the participants stated, ‘I didn’t find using the chatbot useful. It didn’t work well and it often provided wrong answers’. Another participant wrote, ‘It was frustrating when it couldn’t understand what I was trying to say’. This additional learning tool was found useful to some extent by 14% of the respondents. ‘Alex was somewhat useful to me’, stated one of the students. Another student explained, ‘It didn’t help me to improve my vocabulary much, but I enjoyed the opportunity to practice my conversational skills’. It was stated by 40% of the students that using the chatbot did not help them to expand their vocabulary, or it helped them just a little bit (31%), as familiar vocabulary was mostly used while completing the sessions. Up to 53% of the respondents believed that the feedback provided by Alex was useful because, thanks to it, they became aware of mistakes. It also helped them to learn from their own mistakes. ‘The feedback provided by Alex was really helpful. It helped me to understand my mistakes and I could learn from them’, noted one of the research participants. 66% of the research participants agreed that using AI was beneficial because it supported their language skills. However, 34% of the students believe that the application needs to be improved in order to be truly beneficial in the process of FL learning. ‘The application needs to be improved to benefit English learning’, expressed one participant.

3.2.3. Perceived ease of use

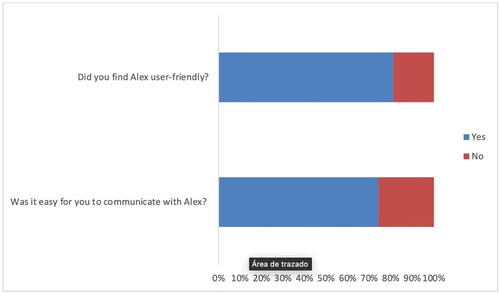

The results of the questionnaire survey showed that 81% of the research participants found Alex user-friendly, although it should be improved for future use. One of the participants mentioned, ‘I found Alex to be quiet user-friendly, but there are still areas where it could be improved’. On the other hand, 19% of the students did not find the application to be user-friendly because it often did not complete the sentences and ideas. They also disliked the small text field, which did not allow them to check all the written text. Because of this shortcoming, they often made mistakes in written communication. One of the participants expressed, ‘I didn’t find the application to be user-friendly. Small text field made it difficult for me to communicate with chatbot. I often ended up making mistakes because of this issue’. However, 74% of the research participants reported easy communication with Alex and they compared it to interacting with humans. One student stated, ‘Communicating with Alex was surprisingly easy for me. If felt almost like talking to another person’. On the contrary, according to 26% of the students, easy communication was not possible because of frequent technical issues. One of the participants shared, ‘I didn’t find communication with Alex to be easy at all because technical issues and unfinished sentences made it frustrating to use’. Students’ perception of ease of use is illustrated in .

3.2.4. Level of interest

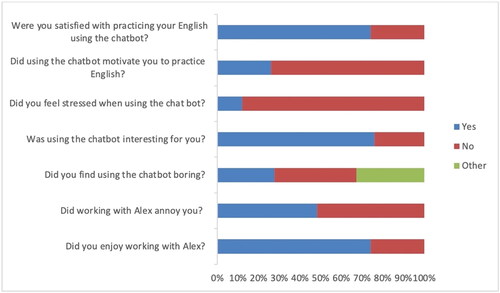

The findings of the questionnaire survey revealed that 74% of the research participants were satisfied with practicing English using the chatbot, mainly because it was a new and fun experience. One student expressed, ‘It was a fun and new experience for me. I have never used chatbot before in English learning’. On the contrary, 27% of the students were not satisfied with the use of the application because of incorrect feedback provided. One of the participants mentioned, ‘I wasn’t satisfied with the application because feedback provided was often incorrect’. Up to 74% of the students reported that using the chatbot did not motivate them to learn English. On the other hand, 21% of the students were motivated, mainly because using the application gave them the opportunity to practice their conversation skills. One research participant stated, ‘I felt motivated to learn English because Alex provided me with a platform to practice my conversation skills’. The majority of the students, specifically 88%, said that they did not feel stressed when having a conversation with Alex because it was friendly and, surprisingly, got the jokes. ‘I didn’t feel stressed at all while using the chatbot’ and ‘It was friendly and understood jokes’, shared participants. Up to 12% of the research participant felt stressed because they often forgot to complete the sessions. They also felt stressed when the chatbot did not finish the sentences and, therefore, it was difficult to understand it. According to 28% of the respondents, using a chatbot in the process of English learning was tedious thanks to the repetitive and boring questions. However, up to 74% of the students reported that they enjoyed using the chatbot as a learning tool, mainly because of the interesting choice of topics and Alex’s opinions on those topics. ‘I enjoyed using chatbot because of the interesting topics. Alex was able to give opinion on everything. It felt like I was having a conversation with a real person’, noted one of the participants. Many students agreed that they felt as if they were writing with a real person rather than with a smart AI-driven technology. This experience was described as interesting by 76% of the research participants. provides information on students’ interest in using AI-driven technology in the process of FL learning.

3.2.5. Learning preferences

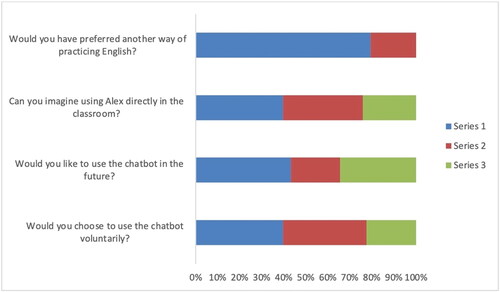

Based on the data released from the questionnaire survey, the findings indicate that up to 79% of the students would choose another way of practicing English. One of the participants mentioned, ‘I prefer other methods for practicing English rather than using the chatbot’. The most frequently mentioned options were talking to a native speaker, watching TV shows, reading books, gaming, or using different platforms, such as Duolingo or Kahoot. It was reported that 36% of the students could not imagine using Alex directly in the classroom because they find it weird, boring, or distracting. On the other hand, 40% of the research participants could imagine using the chatbot in the school setting, and 24% might be able to imagine it if Alex was improved. 43% of the students agreed that, in the future, they would choose to use the application to practice reading, writing, and conversation. ‘I would consider using the chatbot for practicing English in the future’, noted one participant. 22% of them would not like to use the chatbot, and up to 35% would choose Alex if it was improved. 40% of the research participants reported they would voluntarily choose the chatbot only because they were curious to see how it worked. One of the students mentioned, ‘I would try the chatbot out of curiosity’. 38% would not choose it, and the rest of the students (22%) would use this chatbot to practice another language. Students’ learning preferences are presented in .

3.2.6. Perceived advantages and disadvantages

The results show that advantages perceived by the students represent an interesting way of practicing language. One student noted, ‘Using Alex was really interesting’. Additionally, students appreciated the interesting topics and, surprisingly smart answers to questions given. Another participant stated, ‘I enjoyed discussing topics with the chatbot and was impressed by its smart responses’. Ease of use was also highlighted as an advantage. ‘Using Alex was easy. It made learning English more convenient’, mentioned one of the students. Furthermore, students found it to be an innovative way of practicing language. ‘Using the chatbot felt like fresh and innovative approach’, noted a participant. Quick responses given by Alex were also appreciated. ‘I liked how quickly the chatbot answer my questions’, shared a participant. Additionally, students found the questions understandable, leading to easy communication with the chatbot. ‘The questions were clear and easy to understand’, expressed another participant. Feedback provided by the chatbot was also perceived as an advantage, as one of the participants noted, ‘The feedback helped me to improve my language skills’. On the contrary, the most frequently mentioned disadvantages were unfinished sentences and, therefore, misunderstanding in communication. ‘Alex often left sentences unfinished. It wasn’t easy then to follow the conversation’. Repetitive questions were also highlighted as a disadvantage. ‘I found the repetitive questions to be boring’, shared one of the students. Frequent technical issues were another common disadvantage mentioned by research participants. ‘Technical issues often disrupted my interaction with Alex’, expressed another student. Inadequate correction of the mistakes was also mentioned. ‘The chatbot didn’t always correct my mistakes accurately’, noted one of the participants. Poor interactivity was perceived as a disadvantage as well. ‘The chatbot didn’t ask me questions which made the conversation feel robotic’, shared another participant. Furthermore, students found layout to be inconvenient. ‘The layout of the chatbot was not user-friendly’, mentioned one of the students. Lastly, the requirement to meet a certain number of characters was seen as a disadvantage. ‘Having to meet certain number of characters felt unnecessary’, expressed another participant. Perceived advantages and disadvantages are portrayed in below.

Table 3. Perceived advantages and disadvantages of ‘Alex’.

In conclusion, the results of the qualitative analysis indicate the usefulness of the conversational chatbot in the process of FL learning, as it can help students to practice their conversation skills and provide them with feedback in case of mistakes. The application is considered to be user-friendly and enables easy and understandable communication with smart AI-driven technology. It was reported that the use of the chatbot was satisfying and enjoyable, mainly because of its innovative nature and carefully selected topics. Frequent technical problems (e.g. the fact that this piloted version of the chatbot did not sometimes work properly and therefore students were not able to run it at the designated time), and incomplete sentences were considered to be the biggest drawbacks of the chatbot, however, most of the students would choose Alex in the future to practice their language skills if its shortcomings were removed.

4. Discussion

Overall, the findings of this study reveal that the use of chatbots in the process of FL learning is useful since students’ achievement results increased at least by 10-15% after using the chatbot ( and ). This is in line with a research study by Mahmoud (Citation2022) whose university students, beginners in learning English as a foreign language, scored worse in the pre-test than in the post-test (i.e. in the pre-test, nearly 87% of the learners received C and 18% got B, while in the post-test 62% of the students received A and 38% got B). Furthermore, Jeon (Citation2021) in his study conducted among 58 Korean twelve-year-old learners and aimed at FL vocabulary acquisition demonstrated that the students in the experimental group outperformed students in the control group both in the oral and written performance when using the chatbot for learning new FL words and phrases. Similarly, Lee et al. (Citation2022) state that their 38 university students also improved their academic performance. Nghi et al. (Citation2019) state that the use of chatbots in FL classes is a useful tool that helps students practice language skills. Thus, the results indicate that students of any age and at any level of FL can benefit from using a chatbot for FL learning. The results align with the results of the previous research in language learning that suggest that interactive and engaging methods with chatbots can lead to improved learning outcomes by providing a low-stress environment for practice (Essel et al., Citation2022). The findings also correspond to the results of the study conducted by Kuhail et al. (Citation2022), which found that learning was most effective when learners were given guided support, similar to the feedback provided by chatbot. Moreover, the findings from this study support the constructivist theory which emphasizes the active role of learners in constructing their knowledge, as chatbots encourage active engagement and dialog.

In addition, almost all research studies (Belda-Medina & Calvo-Ferrer, Citation2022; Haristiani, Citation2019; Klimova et al., Citation2023; Schmidt & Strassner, Citation2022) agree that the use of chatbots in the process of FL learning is engaging, motivating and fun. These findings were also confirmed by this empirical pilot study because 74% of the students were satisfied with practicing English using the chatbot and they considered the use of chatbots for their language learning entertaining and innovative. 85% of them admitted to not using this AI technology before. For example, Petrović and Jovanović (Citation2021) suggest that students may engage in the use of chatbots for FL learning even more if this AI technology remembers past questions and level of language use. This indicates that the more personalized the chatbot is, the more motivated students are, and thus, they may achieve better learning results. Students’ interest in using the chatbot in this pilot study might have been also connected with the fact that they found the AI-driven technology easy to use (81%) and they also liked the selected topics of their conversation. Furthermore, they appreciated automated feedback on their language mistakes, which is a very important aspect when learning a foreign language (cf. Dokukina & Gumanova, Citation2020).

The practical applications from these findings suggest that chatbots can be used to supplement traditional language learning methods, offering learners a chance to practice language skills outside the classroom. This support the development of more flexible, technology-based educational strategies. Given the increasing importance of personalized learning, these results offer valuable insights for educators looking to create engaging and effective language learning tools. The fact that chatbots can provide real-time feedback and foster a conversational environment contributes to their potential as a supplementary learning tool.

Although students found talking to Alex (the chatbot) as chatting with a human being, they would not prefer this style of learning (79% of students) and would rather choose to talk to a human being, in this case, a native speaker or watching a video. This has been confirmed also by Belda-Medina and Calvo-Ferrer (Citation2022) in their study conducted among Spanish and Polish learners of English who would prioritize human-to-human over human-to-chatbot communication. In addition, there are other drawbacks students complain about in this pilot study, such as frequent technical issues and incomplete sentences causing misunderstanding in communication. This has been also highlighted in a study by Mahmoud (Citation2022) in which 72% of students reported that chatbots might sometimes be inaccurate in their replies because they seem mechanistic and repetitive in their responses.

The results of this research provide valuable insights into the potential impact of AI-based language learning tools on pedagogical practice. Specifically, this study highlights the effectiveness of integrating chatbots into language learning environments to improve students’ language proficiency. Educators can take advantage of these findings by incorporating AI-driven chatbots into their teaching methodologies, with the following recommendations:

Adapt interactions with chatbots to match students’ language proficiency level and learning objectives.

Emphasize feedback and error correction, encouraging active collaboration with chatbots to reinforce the importance of these aspects in language learning.

Provide timely and constructive feedback to help learners identify and effectively correct language errors.

Incorporate chatbot activities into lessons to complement traditional teaching methods, offer students interactive opportunities to practice language skills, and enhance learning beyond formal lessons.

By implementing these recommendations, educators can optimize the integration of AI-driven chatbots into language learning environments, ultimately improving students’ language learning experiences and outcomes.

A limitation of this pilot study is considered to be the small sample size, as the research participants were students from the same faculty. Therefore, future studies should aim to address these limitations by including a more diverse sample of participants, possibly from different faculties or universities, to ensure the generalizability of the findings. In addition, examining the impact of the AI learning tool on students of different ages and levels of language proficiency would contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of its effectiveness. In addition, extending the duration of the study would allow for a deeper exploration of the long-term effects of using AI tools in the FLL process. By addressing these questions, future research can provide a more differentiated and reliable assessment of the potential benefits and limitations of technologies using artificial intelligence in education.

5. Conclusion

The use of smart AI-driven technology is becoming increasingly popular among English language learners. These days, chatbots are used to practice language skills, including conversational skills, by simulating real conversations, which is considered a great way to improve fluency and confidence when speaking a foreign language. One of the biggest advantages of chatbots is considered easy accessibility outside the school environment. Therefore, learners can practice their language skills anywhere and at their own pace. Despite certain drawbacks (e.g. technical issues and incorrect and incomplete utterances) in the use of chatbots for FL learning, the findings of this study also reveal that using smart AI-driven technology in the process of FL learning can help students to improve their language skills through an innovative and fun way of learning. Nevertheless, as research also indicates to ensure the effectiveness of the use of chatbots in FL education, more research studies are needed in this respect, as well as careful attention should be paid to ethical issues when developing, implementing, and using AI-driven technologies for educational purposes.

The findings from this pilot study indicate that conversational chatbots can significantly improve foreign language acquisition among university students. The chatbot, through simulated dialogues, provided an interactive and engaging means of practicing language skills, leading to measurable improvements in both vocabulary and grammatical proficiency. Despite these positive outcomes, the study also revealed several limitations and areas for improvement. Future studies should particularly consider extending the duration to observe longer-term effects of chatbot interactions on language learning. Additionally, expanding the sample to include students from various academic backgrounds and proficiency levels would provide a more comprehensive understanding of the chatbot’s effectiveness across diverse learning contexts. In addition, future iterations of this research should focus on improving the quality of interactions between the chatbot and users. This includes refining the chatbot’s natural language processing capabilities to handle more complex, refined conversations and reduce the occurrence of irrelevant or incorrect responses. Furthermore, future research should focus on investigating the use of chatbots for learning multiple languages or for use in multilingual contexts could also be fruitful. This includes assessing the chatbot’s ability to handle cultural nuances and idiomatic expressions, which are crucial for advanced language proficiency. Finally, as AI-driven learning tools become more ubiquitous, it is vital to conduct ongoing research into the ethical implications, particularly concerning data privacy and security.

Acknowledgement

This study was supported by the SPEV project 2024, run at the Faculty of Informatics and Management of the University of Hradec Kralove, Czech Republic. The authors thank Ondřej Doubek and Jan Zábranský for their help with data processing.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Petra Polakova

Petra Polakova is an Assistant Professor at the Department of Applied Linguistics at the Faculty of Informatics and Management, University of Hradec Kralove, where she teaches Professional English. Her expertise includes second language acquisition. In her work, she focuses on the impact of technologies on second language acquisition.

Blanka Klimova

Blanka Klimova is a Professor at the Department of Applied Linguistics and also head of the department at the Faculty of Informatics and Management, University of Hradec Kralove. Her expertise includes L2A with a special focus on applied linguistics and psycholinguistics.

References

- Akgun, S., & Greenhow, C. (2022). Artificial intelligence in education: Addressing ethical challenges in K-12 settings. AI and Ethics, 2(3), 431–440. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43681-021-00096-7

- Baidoo-Anu, D., & Ansah, L. O. (2023). Education in the era of generative artificial intelligence (AI): Understanding the potential benefits of ChatGPT in promoting teaching and learning. Journal of AI, 7(1), 52–62.

- Bean, S. (2018). Generations divide on the role of Artificial Intelligence in the workplace. Retrieved January 23, 2023, from https://workplaceinsight.net/generations-divide-on-the-role-of-artificial-intelligence-in-the-workplace/

- Belda-Medina, J., & Calvo-Ferrer, J. R. (2022). Using chatbots as AI conversational partners in language learning. Applied Sciences, 12(17), 8427. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12178427

- Belda-Medina, J., & Kokošková, V. (2023). Integrating chatbots in education: Insights from the Chatbot-human interaction satisfaction model (CHISM). International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 20(1), 20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-023-00432-3

- Brown, T. B., Mann, B., Ryder, N., Subbiah, M., Kaplan, J., Dhariwal, P., et al. (2020). Language models are few-shot learners. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2005.14165

- Bryant, C., Felice, M., & Briscoe, T. (2017). Automatic annotation and evaluation of error types for grammatical error correction [Paper presentation]. The 55th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), Proceedings of Association for Computational Linguistics, Vancouver, Canada, 793–805. https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/P17-1074

- Dokukina, I., & Gumanova, J. (2020). The rise of chatbots – new personal assistants in foreign language learning. Procedia Computer Science, 169, 542–546. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2020.02.212

- Essel, H. B., Vlachopoulos, D., Essuman, A. B., & Amankwa, J. O. (2024). ChatGPT effects on cognitive skills of undergraduate students: Receiving instant responses from AI-based conversational large language models (LLMs). Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 6, 100198.

- Essel, H. B., Vlachopoulos, D., Tachie-Menson, A., Johnson, E. E., & Baah, P. K. (2022). The impact of a virtual teaching assistant (chatbot) on students’ learning in Ghanaian higher education. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 19(1), 19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-022-00362-6

- Fitria, T. N. (2021). The use of technology based on artificial intelligence in English teaching and learning. The Journal of English Language Teaching in Foreign Language Context, 6(2), 213–223.

- Golic, Z. (2019). Finance and artificial intelligence: The fifth industrial revolution and its impact on the financial sector. Zbornik Radova Ekonomskog Fakulteta u Istočnom Sarajevu, 19, 67–81.

- Haristiani, N. (2019). (). Artificial Intelligence (AI) chatbot as language learning medium: An inquiry. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 1387.

- Javaid, M., Haleem, A., Singh, R. P., Khan, S., & Khan, I. H. (2023). Unlocking the opportunities through ChatGPT Tool towards ameliorating the education system. BenchCouncil Transactions on Benchmarks, Standards and Evaluations, 3(2), 100115–101016. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tbench.2023.100115

- Jeon, J. (2021). Chatbot-assisted dynamic assessment (CA-DA) for L2 vocabulary learning and diagnosis. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 36(7), 1338–1364. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2021.1987272

- Kalyan, K. S. (2024). A survey of GPT-3 family large language models including ChatGPT and GPT-4. Natural Language Processing Journal, 6, 100048. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nlp.2023.100048

- Kamelabad, M. A. (2022). Personalized conversational agent for second language learning. Early Language Development in the Digital Age. https://www.e-ladda.proj.kth.se/research/projects/personalized-agent

- Kim, J., Lee, H., & Cho, Y. H. (2022). Learning design to support student-AI collaboration: Perspectives of leading teachers for AI in education. Education and Information Technologies, 27(5), 6069–6104. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-021-10831-6

- Klimova, B., Pikhart, M., & Al-Obaydi, L. H. (2024). Exploring the potential of ChatGPT for foreign language education at the university level. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1269319. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1269319

- Klimova, B., Pikhart, M., Polakova, P., Cerna, M., Yayilgan, S. Y., & Shaikh, S. (2023). A systematic review on the use of emerging technologies in teaching English as an applied language at the university level. Systems, 11(1), 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems11010042

- Kuhail, M. A., Alturki, N., Alramlawi, S., & Alhejori, K. (2022). Interacting with educational chatbots: A systematic review. Education and Information Technologies, 28(1), 973–1018. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-022-11177-3

- Lee, Y. F., Hwang, G. J., & Chen, P. Y. (2022). Impacts of an AI-based chatbot on college students’ after-class review, academic performance, self-efficacy, learning attitude, and motivation. Educational Technology Research and Development, 70(5), 1843–1865. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-022-10142-8

- Mageira, K., Pittou, D., Papasalouros, A., Kotis, K., Zangogianni, P., & Daradoumis, A. (2022). Educational AI chatbots for content and language integrated learning. Applied Sciences, 12(7), 3239. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12073239

- Mahmoud, R. H. (2022). Implementing AI-based conversational chatbots in EFL speaking classes: an evolutionary perspective. Retrieved January 24, 2023, from https://assets.researchsquare.com/files/rs-1911791/v1/b6bfdf42-0bef-47f0-90c7-439ff627eb91.pdf?c=1660184054

- Montenegro-Rueda, M., Fernández-Cerero, J., Fernández-Batanero, J. M., & López-Meneses, E. (2023). Impact of the implementation of ChatGPT in education: A systematic review. Computers, 12(8), 153. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers12080153

- Nghi, T. T., Phuc, T. H., & Thang, N. T. (2019). Applying Ai chatbot for teaching a foreign language: an empirical research. International Journal of Scientific & Technology Research, 8, 12.

- Petrović, J., & Jovanović, M. (2021). The role of chatbots in foreign language learning: the present situation and the future outlook. Studies in Computational Intelligence, 973, 313–330.

- Rothe, S., Mallinson, J., Malmi, E., Krause, S., & Severyn, A. (2021). A simple recipe for multilingual grammatical error correction. arXiv:2106.03830 [cs]. http://arxiv.org/abs/2106.03830

- Schmidt, T., & Strassner, T. (2022). Artificial intelligence in foreign language learning and teaching. Anglistik, 33(1), 165–184. https://doi.org/10.33675/ANGL/2022/1/14

- Yin, Q., & Satar, M. (2020). English as a foreign language learner interactions with chatbots: Negotiation for meaning. International Online Journal of Education and Teaching, 7(2), 390–410.

- Yu, H. (2024). The application and challenges of ChatGPT in educational transformation: New demands for teachers’ roles. Heliyon, 10(2), e24289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e24289

- Zhang, R., Zou, D., & Cheng, G. (2023). A review of chatbot-assisted learning: Pedagogical approaches, implementations, factors leading to effectiveness, theories, and future directions. Interactive Learning Environments, 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2023.2202704

- Ziatdinov, R., Atteraya, M. S., & Nabiyev, R. (2024). The Fifth Industrial Revolution as a transformative step towards society 5.0. Societies, 14(2), 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc14020019