Abstract

Despite an increasing interest in pronunciation instruction in English as a majority language or international lingua franca, less is known about pronunciation learning in non-English minority languages, especially among child learners. Bilingual education programs provide a unique context to address this research gap, as they involve immersive education in minority languages. Teachers in these programs thus are insightful informants. The current study focuses on the context of a Mandarin-English bilingual program in Canada and addresses two research questions: What factors do teachers believe influence students’ Mandarin pronunciation learning? What are teachers’ strategies and needs when teaching Mandarin pronunciation? Semi-structured interviews were conducted with twelve Chinese teachers with diverse language backgrounds. The teachers discussed multifaceted factors that influenced bilingual students’ pronunciation learning, including speech targets, individual factors, and language environments at school and in society. Teachers shared a wide array of pronunciation teaching techniques, although they expressed concerns related to policies and resources. This study demonstrates the complexity of teaching the pronunciation of a minority language, whose speech system is distinctly different from English, in a bilingual classroom setting. It shares teaching strategies among bilingual teachers and identifies future directions for policymaking and research.

Introduction

Pronunciation used to be the ‘Cinderella’ of second language (L2) teaching, unfairly oppressed (Celce-Murcia et al., Citation1996, p. 323; Levis & Sonsaat, Citation2017). Among the increasing discussions on L2 pronunciation instruction in recent decades, many were focused on adult learners (Derwing, Citation2020). It is important to examine child learners’ L2 pronunciation learning to directly observe the developmental process (Flege & Bohn, Citation2021).

There is a variety of contexts for children to learn L2 pronunciation, for example, students can learn a foreign language from classes, and immigrant children can learn the societal majority language from the community. Among these contexts, bilingual education programs provide an opportunity to learn an L2 through immersive input, where subject content is mostly or always delivered in two languages (Baker, Citation2007; Cummins, Citation1979). Some programs enroll only language-majority students (i.e. one-way immersive education), where all students are L2 learners of the language of instruction, and others enroll students with diverse language backgrounds (two-way bilingual education), where some students are L2 learners and others are native or heritage speakers of the language(s) of instruction. As for the language of instruction, in addition to the societal majority language, many programs around the world choose to teach English as an international lingua franca (Jenkins, Citation2007; e.g. Kordíková & Brestenská, Citation2022; Probyn, Citation2001; Richter, Citation2019; Sakamoto, Citation2012), some focus on an immigrant language or local minority language (e.g. French immersion education in Canada, Russian-Hebrew bilingual education in Israel, and Gaelic-English bilingual education in Scotland, Spanish-English bilingual education in the United States; Genesee & Lindholm-Leary, Citation2008; Nance, Citation2020; Schwartz et al., Citation2016), and others have the important function of indigenous language revitalization (e.g. programs in Canada, French Polynesia, New Zealand, Malaysia, Mexico, and South Africa; David et al., Citation2009; Dicks & Genesee, Citation2017; May & Hill, Citation2005; Ngwenya, Citation2010; Paia et al., Citation2015; Riestenberg & Sherris, Citation2018).

When immersed in the majority language in an immigration context, children are often assumed to be able to develop native-like (or at least fully intelligible) L2 pronunciation (Derwing, Citation2020), because it is considered a part of basic interpersonal communicative skills (BICS) which tend to develop at a fast rate (Cummins, Citation1981). However, when the target language does not enjoy a high social status (i.e. not a majority language in the society or an international lingua franca such as English), speech input is limited, and students’ motivation may vary, which can impact children’s learning outcomes (Flege & Bohn, Citation2021; Kennedy & Trofimovich, Citation2017). Therefore, research on children’s pronunciation learning of a non-English minority language, such as an immigrant language, will offer theoretical implications for how factors such as the age of learning, speech input, and motivation impact pronunciation learning.

Existing evidence shows that when most students are L2 learners of the language (i.e. one-way immersion), it is challenging for students to reach high proficiency in pronunciation due to limited opportunities for oral interaction with native-like speakers (Lambert et al., Citation1993; Netelenbos et al., Citation2016; Weich, Citation2023), despite pronunciation being a BICS (Cummins, Citation1981). Compared to such a one-way immersion design, pronunciation studies in a Spanish-English program and a Gaelic-English program indicate that two-way bilingual education can level out the home language differences, as children with diverse backgrounds provide authentic input for each other (Menke, Citation2017; Nance, Citation2020). However, both programs included pairs of Indo-European languages, and the students who were L2 learners still had familial connections or community exposure to Spanish or Gaelic, respectively. More information is needed in various languages with various opportunities for input in the community to verify such results.

In addition to implicit learning through peer interactions, teachers often need to explicitly teach the language forms, including pronunciation, in Language Arts and through incidental support (Dicks & Genesee, Citation2017). However, teachers are often left with few guidelines for pronunciation instruction in bilingual education, and not much is known about how the pronunciation of an immigrant language is taught to children in practice (however, see Ngwenya (Citation2010) and Riestenberg and Sherris (Citation2018) on indigenous language revitalization in South Africa and Mexico). Qualitative data from teachers of an immigrant language is necessary to understand how frontline educators make meanings in and interact with their lived contexts of pedagogical practices (Creswell & Creswell, Citation2023), including their insights, strategies, and needs of pronunciation teaching in bilingual classrooms.

This study provides a unique case of a Chinese-English two-way bilingual program in Western Canada. In this program, 50% of the academic content is delivered in English and the other 50% in Mandarin (a.k.a. Standard Chinese). The program is one of the most highly respected Mandarin bilingual programs in North America (Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada, Citation2013). It attracts not only children with Chinese backgrounds to maintain or learn Mandarin as a heritage language but also children who speak English or other languages at home to learn Mandarin as an additional language for the cognitive, economic, and cultural benefits of being bilingual (Cummins, Citation2017; Wu, Citation2005). By presenting Chinese teachers’ lived experiences with pronunciation teaching, this study depicts the complexity of pronunciation instruction in a minority language, presents teachers’ reflections on factors of pronunciation learning, and adds to evidence of teaching techniques for the worldwide intercultural community of bilingual teachers (Fishman, Citation1976). The following sections introduce our lenses to understand teachers’ discussions, including the factors of pronunciation learning, the challenges of pronunciation teaching and learning, especially in an immigrant language, and an empowering view of teachers’ roles in pronunciation teaching in the context of bilingual education, and pose research questions.

Factors of pronunciation learning in a bilingual education context

Pronunciation learning in a bilingual education context is impacted by multifaceted factors such as the transfer between the speech systems of the first language (L1) and L2, language status of L1 and L2, language input and output in L1 and L2, motivation, and language learning aptitude (MacLeod & Stoel-Gammon, Citation2010; Netelenbos et al., Citation2016; Richter, Citation2019), similar to the factors of bilingual language development (Paradis, Citation2011). Although Paradis (Citation2011) included a wide range of factors under a capping terminology, ‘individual differences’, in this study, L1-L2 transfer and the language environment at large are highlighted as separate categories, i.e. linguistic and social factors, respectively. This is because as opposed to an immigration context (Paradis, Citation2011), in a two-way bilingual program, language transfer between the two languages of instruction and the language environment at school and in society are largely shared among the students and can be discussed at the group level. Therefore, this study adopts three categories of factors for pronunciation learning: linguistic factors, individual factors, and social factors. Each category will be introduced below and guide the organization of teachers’ reflections.

Linguistic factors

Pronunciation learning is impacted by the phonological or phonetic similarities between the L1 and L2. For example, the Speech Learning Model (Flege & Bohn, Citation2021) hypothesized that learners perceive an L2 phonetic (speech sound) category based on its most similar L1 counterpart and gradually establish its own phonetic category (e.g. an English-L1 learner of French might assimilate the French /p/ to the English /p/ although these two sounds can be slightly different in their phonetic details). The Perceptual Assimilation Model (Best & Tyler, Citation2007) hypothesized that learners distinguish the L2 phonemic contrasts (contrastive sound pairs that can differentiate word meanings, e.g. /b/ and /p/ in ‘bay’ and ‘pay’ in English) using L1 contrasts. Meanwhile, the universal difficulty of the L2 sounds also plays a role: Speech sounds that are easier to acquire are usually the ones that are easier to articulate, occur in most world languages, and develop earlier among young children (Kent, Citation1992; McLeod & Crowe, Citation2018). Speech sounds that are hard to acquire would pose challenges for both L1 and L2 learning children (Major, Citation2001).

Individual factors

L2 learners’ age of acquisition is an important individual factor: An earlier age of acquisition has been related to better L2 pronunciation learning outcomes (Flege, Citation1995), i.e. ‘earlier is better’ (p. 233). However, recent evidence suggests that age of acquisition is not the sole individual factor of L2 pronunciation learning, as pronunciation learning is impacted by the quantity and quality of input received by the individual learner, including the length of exposure, the current amount of exposure, the opportunity of output, and the authenticity of the input (Flege & Bohn, Citation2021). Furthermore, pronunciation learning is impacted by a wide array of other individual factors. For example, language learning aptitude measured by associative memory (novel correspondence between objects and names) and phonological coding (novel correspondence between sounds and symbols) predicted learners’ development of accuracy, comprehensibility, and fluency of L2 speech production (Robinson, Citation2005; Saito et al., Citation2019). In addition, L2 learners’ motivation and cognitive attitudes (i.e. the awareness of linguistic and practical values of L2 pronunciation learning) predicted their active use of learning strategies to improve their L2 pronunciation (Sardegna et al., Citation2018).

Social factors

Input and motivation are related to language status in the wider society. When being bilingual is of high value in educational, professional, and social contexts, learners have plentiful opportunities to use both languages, self-identify as dual-lingual speakers, and demonstrate balanced pronunciation competence (e.g. French-English bilingualism in Ontario, Canada, MacLeod & Stoel-Gammon, Citation2010). On the other hand, when one language is a minority language, pronunciation attrition or incomplete learning may occur (Chang et al., Citation2011; Flege et al., Citation1995).

Previous evidence of teaching English as an L2 or international lingua franca indicated that teachers were able to consciously reflect on and utilize these multifaceted factors, including comparing L1 and L2 speech systems, promoting L2 learners’ motivation, and taking culture and exposure into consideration when teaching a minority language (Banda, Citation2000; Couper, Citation2021; Probyn, Citation2001). The current study investigates how these factors are understood by teachers of young children learning a non-English minority language and utilized in their teaching practices in a bilingual school setting.

Challenges in pronunciation teaching

With the understanding that pronunciation teaching of non-English minority languages is a distinctive issue, English teachers’ perspectives can provide insights into the challenges in pronunciation teaching. Teachers of adult English L2 learners reported a reluctance to teach pronunciation due to limited resources and insufficient knowledge (MacDonald, Citation2002). Teachers embraced the intelligibility principle in theory but tended to set nativeness as a goal in practice (Jenkins, Citation2007; Levis, Citation2020). Their instruction techniques consisted mainly of form-focused instruction (FFI, Spada & Lightbown, Citation2008) such as practice and repetition (Baker, Citation2014; Foote et al., Citation2011; Murphy, Citation2011) and less communicative language teaching approaches (CLT, Littlewood, Citation2011).

In terms of teaching pronunciation to children, Couper (Citation2021) surveyed teachers of child L2 learners in Uruguay and New Zealand, where English is taught as an international lingua franca and a majority L2, respectively. The results of this survey study were similar to the reports of teachers of adult L2 learners (MacDonald, Citation2002; Murphy, Citation2011) in that they lacked confidence in pronunciation teaching due to limited knowledge of phonetics and phonology. Their pronunciation instruction was limited by time, textbooks, and curricula. In addition, non-native English teachers had concerns about their own pronunciation (see also, Çağatay, Citation2021).

In the context of bilingual education for school-aged children that involves a non-English minority language, similar to the English teachers reviewed above, needs for resources and training in pronunciation teaching were reported (Pérez Cañado, Citation2016; Wisecup, Citation2017), as well as the particular struggles to promote the use of the minority language (Estrada & Chacón, Citation2015). Therefore, pronunciation teaching of a minority language in English-dominant environments involves an additional level of complexity compared to teaching English as an L2 due to the target language’s minority status compared to English as a local majority language or an international lingua franca. The current study aims to present and investigate such complexity and challenges from teachers’ perspectives. Due to the focus on the Chinese bilingual program in Western Canada, the next section introduces the specific challenges of teaching and learning Mandarin pronunciation in Western Canada, an English-dominant environment.

The challenges of teaching and learning Mandarin pronunciation in Canada

Learning Mandarin pronunciation in Western Canada can be particularly challenging because Mandarin is very different from English in its phonology. Mandarin is a tonal language where four lexical tones () differentiate word meanings. Therefore, inaccurate productions of tones may lead to miscommunication. In addition to tones, Mandarin has unique speech sounds. Its consonant inventory includes voiceless sibilant fricatives (and corresponding affricates) at three places, i.e. alveolar [s], alveopalatal [ɕ], and retroflex [ʂ], compared to only two in English, i.e. alveolar [s] and postalveolar [ʃ] (Li & Munson, Citation2016). The vowel inventory includes rounded front-closed vowel [y], back-mid-closed vowel [ɤ], and apical vowels [ɿ] and [ʅ], which are not present in English (Lee-Kim, Citation2014).

Table 1. Mandarin lexical tones. The four tones were produced by a female Mandarin speaker, and fundamental frequency (f0) was extracted using Praat.

Mandarin pronunciation is also difficult due to its logographic orthography, for learners can access little pronunciation information through written materials (Chen et al., Citation2004). To facilitate language and literacy development, Pīnyīn, the official romanized transcription system of Mandarin, is widely used in teaching Mandarin in Mainland China and worldwide. The bilingual program has adopted Pīnyīn in its current curriculum design. The curriculum indirectly addresses pronunciation through the learning of letter-sound relationships of Pīnyīn and does not directly address pronunciation instruction (Alberta Education, Citation2006).

Beyond the linguistic and literacy complexities, the program’s composition of student population is diverse in the immigration context (Liu, Citation2020). Different waves of Chinese diasporas who arrived in Canada at various times may speak different Chinese fāngyán (regional variations of Chinese dialects) with drastically different speech systems, although the number of Mandarin speakers increased in recent decades (Duff & Doherty, Citation2019). Consequently, the bulk of the student population is somewhat connected to Chinese heritage but exposed to English at home (e.g. second- or third-generation children of non-Mandarin fāngyán speakers), followed by L1-speakers of Mandarin, other fāngyán, and a few other languages.

In summary, teachers are challenged by not only the generic difficulties of teaching pronunciation in a minority language but also Mandarin’s unique speech system and the diverse student population. This study provides a qualitative analysis of how teachers have experienced and addressed the challenges of Mandarin pronunciation teaching in Canada and developed strategies to promote bilingual students’ pronunciation learning.

An empowering view of teachers’ role

There are different approaches to understanding the complex and challenging issues in bilingual education. One approach is to analyze the problems in the system and advocate for improvements. For example, Duff and Doherty (Citation2019) criticized the ill-designed curricula, unnatural classroom interactions, and lack of teaching resources in Chinese bilingual education.

On the other hand, Menken and García (Citation2010) took an empowering view of teachers’ roles. Teachers are active policymakers in the classroom and use their own intuition, knowledge, experience, and reflections to negotiate between language education policies and their practices. For example, Estrada and Chacón (Citation2015) demonstrated how a teacher struggled to promote the students’ use of Spanish in the United States by maintaining Spanish use in the whole class and prioritizing interactions in small groups. Schwartz et al. (Citation2016) interviewed educators in a Mandarin-English bilingual school in Canada and a Russian-Hebrew bilingual preschool in Israel. Challenged by the lack of resources and the shifting curriculum designs, teachers adopted flexible classroom practices (e.g. code-switching), collaborated with teachers of the other language to facilitate cross-linguistic transfer, and managed the curriculum innovatively to best support student learning. Instead of focusing on the challenges and problems in bilingual education practices (Duff & Doherty, Citation2019), these studies emphasized teachers’ active roles in bilingual classrooms and presented practical evidence by, from, and for frontline educators.

This study adopts this empowering lens in pronunciation teaching in bilingual education contexts. We believe teachers possess an insightful understanding of pronunciation learning and are able to address the challenges with techniques and strategies. Specifically for the Chinese bilingual program in the current study, despite the challenge of learning Mandarin in an English-dominant society, the program has thrived over the past four decades, starting in only two elementary schools in 1982 and continually expanding to be offered in 14 schools (7 elementary, 4 junior high, and 3 high schools) across the city in 2023 (ECBEA, n.Citationd.). One important factor for such success was considered to be the availability of diverse Chinese language teachers with high professionalism and strong Mandarin competence (Liu, Citation2020). There is a rigorous standard of teaching qualifications and Mandarin proficiency during teacher recruitment. Thus, we believe it is especially informative to present this case and share the successful experiences of the teachers with other researchers and bilingual teachers.

The current study

The current study presents teachers’ perspectives of teaching the pronunciation of a minority language, specifically, in a Chinese-English two-way bilingual program in Alberta, Canada. This study poses two research questions: What factors do teachers believe influence students’ Mandarin pronunciation learning? What are teachers’ strategies and needs when teaching Mandarin pronunciation? Based on the lenses introduced above, we believe teachers, as powerful frontline practitioners, have an insightful understanding of students’ bilingual learning. Although they are faced with the complexity and challenges of teaching the pronunciation of a minority language, we believe teachers are resourceful informants with practical strategies. This study aims to share these strategies and advocate for teachers’ needs in their teaching practice.

Method

The study has obtained ethics approval from the Research Ethics Board at the University of Alberta (Pro00075638). The thematic data analysis approach was adopted, where researchers engaged with the data, coded data extracts, categorized codes, and then conceptualized the themes (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006; Peel, Citation2020). The report of methods and findings is guided by COREQ (Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research, Tong et al., Citation2007). See Supplemental Material A for the full checklist.

Participants

Voluntary and snowball sampling methods were used to recruit twelve teachers from three elementary schools. Interviewees had diverse language backgrounds, educational backgrounds, and teaching experiences. Each teacher was assigned a pseudonym. Because the Chinese bilingual program is a rather small community with a limited number of teachers, specific information about their language, educational, or teaching experiences can be identifying. Therefore, individual teachers’ information was omitted to protect participants’ confidentiality. As an aggregated description, participants’ L1s included not only Mandarin but Cantonese and other Chinese fāngyán. Seven teachers were exposed to Mandarin from birth, and the others started to learn Mandarin at school age. Among the latter, three were native speakers of another Chinese language or fāngyán, and two were native speakers of English who later attended the Chinese bilingual program. Among the twelve teachers, eight self-rated their Mandarin to be ‘very fluent’, three ‘quite fluent’, and one ‘somewhat fluent’. No one self-rated their Mandarin to be ‘limited fluency’ or ‘not fluent’. Teachers were each teaching one of the grades from kindergarten to grade five, but most teachers had experience teaching other grades. The years of teaching ranged from one to more than twenty years. Teachers received varying amounts of training in education, Mandarin teaching, and L2 teaching from a variety of sources. Among them, five teachers received specific training in teaching Mandarin through degree programs, university courses, or professional development (PD). It should be mentioned that Chinese teachers in this program have to hold a local teaching certificate (Liu, Citation2020). In the earlier years of the program, most teachers were immigrants from Mainland China who were certified to teach in Alberta. In recent years, more teachers obtained their Bachelor’s degree in Education in Canada. In either case, teachers were not mandated to have formal training in teaching Mandarin, teaching L2s, teaching pronunciation, or phonology and phonetics.

Interviewer

The interviewer was the first author of the paper. They had research experiences in phonetics and child language development. They were familiar with school settings through research activities but did not have work or learning experience in bilingual education. They were native in Mandarin and proficient in English.

Interviews

Semi-structured interviews were conducted in the schools. General guidelines (Supplemental Material B) were used, but teachers were encouraged to discuss each topic in an open-ended style. Each interview was conducted in the teacher’s preferred language and lasted 15 to 42 minutes. Interviews were audio-recorded with a Zoom H1n digital recorder.

Transcription

The recordings were each transcribed by one of three Mandarin-L1 transcribers who were proficient in English. Mandarin interviews were translated into English. Each transcript was reviewed by another transcriber. The first author was either the transcriber or reviewer of all transcripts.

Thematic analysis

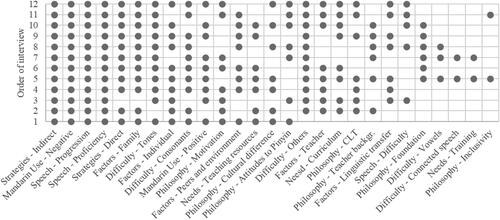

Conventional thematic analysis was used, where codes and themes emerged from the text. An initial codebook was developed after reading the transcripts several times. The first author and a research assistant independently coded the transcripts in NVivo 12. The first round of coding reached a weighted average agreement of 98.81% and a weighted average κ of 0.72, interpreted as ‘good agreement’. A full consensus was reached through discussion. The initial and final codebooks are documented (Supplemental Material C). The codes were reanalyzed into themes, and a mind map was presented to facilitate understanding (). The organization is based on the three levels of pronunciation learning factors and the challenges and strategies of teaching pronunciation in minority languages discussed in the introduction.

Figure 1. A mind map for the themes emerged from teacher interviews.

Saturation

shows when each of the 27 codes was mentioned. The first five teachers had already mentioned all the codes. Each teacher mentioned 15 to 24 codes. Four codes were mentioned by all teachers. Twenty codes were mentioned by more than six teachers. Each code was mentioned by at least two teachers. This suggests that all concepts were repeated multiple times and new concepts were unlikely to emerge with a larger sample (Trotter, Citation2012).

Result

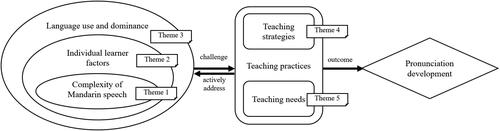

Five themes emerged: (1) Mandarin pronunciation learning is difficult but progressive; (2) Pronunciation learning is impacted by multiple individual factors; (3) The societal majority language impacts the bilingual space at school; (4) Teachers incorporate direct and indirect techniques to teach Mandarin pronunciation; (5) Teachers express concerns and needs about teaching pronunciation in bilingual classrooms. The first three themes discussed how teachers reflected on the impacts of linguistic, individual, and social factors. The last two themes highlighted teachers’ powerful roles but also advocated for their needs.

Mandarin pronunciation learning is difficult but progressive

Developmental trajectories of Mandarin speech

Most of our teachers believed that students’ Mandarin skills progressed across grade levels as their pronunciation ‘gets better (Teacher On)’, and ‘their ability to express themselves is growing (Teacher Yi)’. Meanwhile, some teachers pointed out that students’ pronunciation progressed slower in higher grades:

It is certain that their Chinese will improve, but when you leave the Chinese environment, you actually have limited room for improvement … Their growing speed will slow down. (Teacher Hsu)

I think they are better in tones in the lower grades. As they slowly advance to higher grades, it seems that they forget about the tones. (Teacher Feng)

Challenging speech units

Despite the generally progressive learning trajectory, teachers agreed that Mandarin pronunciation was challenging and identified speech units that were difficult to articulate.

Tones were mentioned by most teachers. Tones can be challenging for learners from an English-dominant environment since they cannot be assimilated directly into English categories (Best & Tyler, Citation2007; Flege & Bohn, Citation2021). English speakers may perceive tones as uncategorized speech units, nonlinguistic melodies, or intonations, which do not bear as much linguistic significance (So & Best, Citation2010), as recognized by teachers:

Sometimes, they just shrug and tell you that they can’t hear anything, there’s no difference at all. (Teacher Feng)

[T]he tone, aww … it’s hard for them! … they feel like they’re saying it, … but they’re not … I find it’s hard for them to [perceive the difference] because it’s not in English. (Teacher Young)

In addition to tones, teachers mentioned challenging speech sounds. Teachers’ reflections were compared with Lin and Johnson (Citation2010), which investigated Mandarin speech sound patterns in bilingual students in an English immersion program in Taiwan (Supplemental Material D). Teachers nominated challenging consonants that were comparable to the empirical findings, including the alveolo-palatal fricatives and affricates j q x /tɕ tɕʰ ɕ/ and retroflex fricatives and affricates zh ch sh r /tʂ tʂʰ ʂ ʐ/. In contrast, j q x are established before two years of age in Mandarin-L1 children (Zhu, Citation2002). Bilingual students’ speech development does not seem to follow the trajectory of monolingual children, which can be attributed to cross-linguistic influence (Meziane & MacLeod, Citation2020). Nonetheless, teachers gave fewer examples of challenging vowels, and their observations did not match previous empirical data. For example, teachers mentioned difficulties in the apical vowel /ʅ/ and the rhotic vowel /ɚ/, which were not documented among bilingual children in a Mandarin-majority context (Lin & Johnson, Citation2010). Therefore, further investigation into vowel patterns in bilingual children is warranted.

Meanwhile, when asked about challenging speech units for the children to pronounce, teachers mentioned issues that are not pronunciation-related. For example, they reported that students used the English letter ‘c’ to transcribe k in Pīnyīn. It appeared that teachers had difficulties pinpointing specific speech sounds using phonological or phonetic terms. Instead, in their reflections, pronunciation learning is a ‘by-product’ of learning Pīnyīn. Since Mandarin pronunciation was only addressed through Pīnyīn in the curriculum, and teachers were not required to receive training in phonology or phonetics, such an association among teachers is not surprising.

In summary, the first theme discussed the development and difficulties in students’ Mandarin pronunciation. The developmental trajectories were generally progressive but might also experience plateauing. Specific examples of challenging speech units were discussed, which suggested the impacts of the phonetic (dis)similarities between L1 and L2 speech systems as well as the universal difficulty of the targets. In addition to linguistic factors, bilingual speech is also impacted by individual factors of the learners, discussed in the next theme.

Pronunciation learning is impacted by multiple individual factors

Family language environment

The effect of family backgrounds was frequently mentioned. Teachers reported that students with no Mandarin background would be influenced by English in their speech learning. Moreover, teachers considered the impacts of Chinese fāngyán. Some stressed fāngyán’s differences from Mandarin, and others highlighted its facilitative effect due to the shared linguistic and cultural features. These different foci may be related to teachers’ own language backgrounds. Compare the statements of Teacher Gwok and Teacher Hsu who were native speakers of Cantonese and Hokkien, respectively, and Teacher Yi who was native in Mandarin:

If they already speak Cantonese, … tones are no problem for them. (Teacher Gwok)

Overall, it is Asian children [who are better at Mandarin speech] … He can relate. (Teacher Hsu)

They actually have a lot of Chinese culture components and Chinese language components in their minds, but because they use a fāngyán [other than Mandarin] … they are affected by it in … pronunciation. (Teacher Yi)

He is not likely to learn according to the teacher’s accent … It is not like his family, … every day, 24 hours a day, with mom and dad. (Teacher Bai)

[If] his family doesn’t speak Chinese, nor does his friends, he has no opportunity to speak Chinese except speaking with Chinese teachers in class every half day. You don’t have so many people in the end. (Teacher Jia)

Once you [parents] stop speaking the mother tongue to him, the mother tongue of your children will soon disappear … we will always … tell the parents to emphasize speaking Chinese with them at home, or whatever the language is. (Teacher Hsu)

The diversity in the student population means not all students have family support in Mandarin at home. Teachers recognized that students in the two-way bilingual program are ‘completely different (Teacher Liu)’ from students in China, and ‘overseas Chinese teaching is not the same as domestic Chinese teaching (Teacher Yi)’. Teachers seemed to have differentiated expectations for students without a Mandarin background and provided support as needed. ‘[W]e also allow you to enter the school, and then gradually and continuously help … through teaching. (Teacher Yi)’. They often emphasized how students with non-Mandarin backgrounds could also make significant achievements in Mandarin, where motivation and learner aptitudes played a role and sometimes compensated for the lack of home input.

Other factors of Mandarin speech learning

Teachers highlighted motivation as a factor and used effort and participation as indicators: ‘If you are not interested, … it is difficult to improve (Teacher Bai)’. ‘The English families are … very motivated to use whatever [activities] I get them (Teacher Young)’. ‘If he takes time to practice, he can speak very well (Teacher Yi)’. Language learning motivation can be divided into instrumental and integrative motivations, which reflect the desire to achieve specific goals and to achieve social integration through L2, respectively (Gardner & Lambert, Citation1972). Based on the teachers’ reflections, instrumental motivation was rare in these young students, which is in line with survey-based research (Xu & Case, Citation2015).

Language learning aptitude was another factor identified by the teachers:

Unless the children’s innate language talent is strong, it is not so easy to learn Chinese here. (Teacher Jia)

For language, … comprehension, I think still there are differences. Some children actually don’t have any background to speak Chinese or any other Asian language. However, they have a way to catch the points. (Teacher Hsu)

In addition to these learner factors, teachers highlighted their own language backgrounds as a factor. Here is a quote from a Mandarin-L1 teacher:

I think that if they learn from Chinese teachers who are native speakers of Chinese, as the teachers will subconsciously speak Chinese to them a lot, their progress in Chinese will be faster. (Teacher Jia)

With a variety of teachers, … [students] will not be influenced by a particular accent of teachers across six years. (Teacher Bai)

I learned Chinese and English bilingually, so I think [of] how the teacher used to encourage us to learn before. I still remember some homework or some projects … Maybe I can teach them these again. (Teacher Gwok)

Many of us … used to learn Chinese here … So when seeing us, many parents will say: ‘You know, in fact, learning Chinese also has a successful side’. (Teacher Lee)

In this section, we presented several individual factors of pronunciation learning, including family language environment, motivation, and L2 aptitudes, as well as teacher effects. In addition to these individual factors, teachers also reflected on the social factor of language environments, which is discussed in the next theme.

The societal majority language impacts the bilingual space at school

Bilingual education is impacted by the language environments of the school and the broader society (Baker, Citation2007; MacLeod & Stoel-Gammon, Citation2010). This section will discuss how a bilingual space is created at school, and how it is affected by the surrounding environment.

The environment at school

The merit of the two-way bilingual design lies in the additive bilingual conceptualization and the interactions among peers from diverse backgrounds (Dicks & Genesee, Citation2017; Menke, Citation2017; Nance, Citation2020). Teachers suggested that the program provided access to knowledge and social interactions for new immigrant children, promoted heritage speech maintenance, and supported L2 pronunciation learning of non-Mandarin students, which matched the functions of two-way bilingual programs listed in Wu (Citation2005).

With diverse students fulfilling a variety of linguistic and academic goals at school, a unique bilingual space was established, where students spontaneously provided authentic language environments for each other.

She came from … Chinese family but not Mandarin-speaking, but she would speak to the other friend in Mandarin because that friend doesn’t speak much English. (Teacher On)

They’re more willing to [use Mandarin], they feel more comfortable maybe, when there are some Mandarin-speaking kids around. (Teacher Young)

However, Schwartz et al. (Citation2016) suggested that to achieve language balance, the language-majority and -minority students should be around the same number. In this program, ‘only one student in my class speaks Chinese at home (Teacher Jia)’, ‘many parents are second-generation (Teacher Ding)’, and ‘one of them is from South Korea, and then many of them are mixed-race (Teacher Lee)’. With such diversity, students eventually resorted to English as a lingua franca at school, which is related to the language status of English in the community.

The environment of society

English dominance in the community has inevitably sneaked into the school environment. Although 50% of the class content was delivered in Mandarin, the broader school environment was unbalanced: ‘Not all the lunch supervisors will speak Chinese, so it is difficult to require [Mandarin use]… The assembly of the school, and the announcement of the school, they are all in English (Teacher Cheng)’. Also due to English’s majority status, ‘the older siblings will speak English to them’, ‘parents begin to pick up English as well (Teacher Ding)’, and ‘the videos they watch are in English (Teacher Lee)’. Consequently, students ‘still tend to speak English (Teacher Cheng)’.

Meanwhile, the social factor interacted with the factors reviewed in the first two themes. Teacher Hsu described, ‘Once you said to use Chinese, everyone will be silent even though they talked loudly just now’, because Mandarin was linguistically challenging and ‘they don’t have this language at all’. In addition, students lost motivation for using Mandarin because ‘I [the student] will use English anyway. Why should I use Chinese?’ It appeared that the development of students’ Mandarin pronunciation skills, the willingness to speak Mandarin, and a balanced bilingual environment cyclically impacted each other.

It became clear that tensions existed between the language environments at school and in the community. Two-way bilingual education did not magically promote the minority language. Instead, teachers took active and purposeful efforts to maintain the bilingual space. To improve students’ Mandarin pronunciation skills and encourage Mandarin use, teachers adopted a variety of techniques and strategies, which are reviewed in the next theme.

Teachers incorporate direct and indirect strategies to teach pronunciation

Previous checklist-based surveys suggested that pronunciation teaching techniques lacked innovation and diversity in practice (Foote et al., Citation2011; Murphy, Citation2011). Our study used a semi-structured interview method and elicited open-ended discussions to identify the techniques used. The node of ‘teaching strategies’ was further divided into two categories: direct strategies, which directly targeted speech forms (i.e. Form-Focused Instruction or FFI), and indirect strategies, which contextualized speech learning in meaningful activities (i.e. Communicative Language Teaching or CLT). To share teachers’ insights among researchers and fellow educators, full quotes are presented in Supplemental Material E.

Direct strategies of Mandarin speech teaching

Teachers used a variety of techniques to address speech forms directly. Letting students repeat after models and directly correcting their errors, which were often reported in previous literature (Foote et al., Citation2016; Murphy, Citation2011), constituted only a part of their responses. Although teachers emphasized the importance of repetitive practice, they were aware that this was ‘not rote memorization (Teacher Liu)’ in traditional pronunciation teaching (Isaac, 2009). Instead, they highlighted its functional importance, that it could improve fluency (Teacher Jia), familiarize students with the ‘flow of speech (Teacher Liu)’, and reinforce learning outcomes (Teacher Bai). In addition, teachers provided listening materials to exemplify ‘the correct pronunciation (Teacher Liu)’ and exaggerated their models for students ‘to hear it clearly (Teacher Lee)’. Meanwhile, they provided multimodal cues, including but not limited to visual cues (e.g. graphic illustrations of tones), tactile cues (e.g. feeling the articulators), gestural cues (e.g. using hands to demonstrate articulatory gestures), and written cues (e.g. Pīnyīn).

The richer inventory of direct strategies in this study may be attributed to three reasons. First, some of our teachers received training in L2 teaching and Mandarin teaching from a wide range of sources, such as university courses and PD sessions. Some discussed what they learned from linguistic courses and readings in phonetics and phonology (e.g. Teacher On and Teacher Yi), which is different from Couper’s (Citation2021) report on teachers’ lack of knowledge in these areas. Therefore, some teachers were equipped with specific knowledge to teach pronunciation explicitly. Second, most of our teachers were L2 learners of English. In East Asia, English is often taught as a foreign language (Tokumoto & Shibata, Citation2011) with a large proportion of FFI. Teachers might have translated their own learning experiences into teaching skills. Third, the Mandarin speech system is so different from English that teachers would not expect it to be ‘picked up’. This forced teachers to adopt explicit teaching techniques. For example, Teacher Feng reflected that students ‘couldn’t hear the difference [between tones] very well’, so they had to ‘use gestures to tell them’.

Indirect strategies of Mandarin speech teaching

Teachers assigned equal emphasis, if not more, to CLT and used indirect strategies to teach pronunciation in meaningful contexts. First, teachers adopted classroom policies and reward systems to encourage Mandarin use. This was different from practicing with adult learners, who usually have stronger instrumental or integrative motivations to learn a minority language (Baker et al., Citation2011). However, the extrinsic requirements and rewards would not be enough to promote continuous learning (Noels et al., Citation2000), and other strategies were incorporated to promote intrinsic motivations.

Second, teachers used multimedia resources to teach Mandarin speech. These not only provided culturally authentic materials but addressed the young learners’ motivations, particularly integrative motivations. This is appropriate for child learners because they are seldom encouraged by instrumental motivations (Xu & Case, Citation2015) – As Teacher On recognized, ‘They are not gonna tell me “I wanna learn Mandarin because it’s good for my job’’’. Instead, they stated, ‘They think, “Oh, Mandarin-speaking, there are cool TV shows”. And they want to understand it’. Teacher Gwok let the students ‘listen to the songs that I used to listen to when I was a child … They like them, really. Then you will see some foreign children … find out on YouTube to sing’. Through the long list of songs they provided, it became clear that the songs were not simply a teaching tool but were attached to cultural memories shared amongst Chinese communities around the world, which were passed down intergenerationally and passed around interculturally through teaching practices.

Third, teachers taught Mandarin pronunciation through meaningful activities. Skills were practiced through language and literacy activities such as daily conversations, personal narratives, and reading. In addition, pronunciation was practiced in other subject areas such as health and mathematics, which were taught in Mandarin by the curriculum design (Alberta Education, Citation2006). For example, students watched ‘videos related to health science’ to ‘learn the subject but also learn the language (Teacher Ding)’ and recorded videos in Mandarin to ‘tell … how to do addition (Teacher Bai)’.

In summary, teachers presented powerful toolkits of direct and indirect pronunciation teaching strategies. They flexibly and innovatively negotiated between curriculum-adopted CLT (Alberta Education, Citation2006) and the efficiency of FFI (Isaacs, Citation2009) to achieve the expected learning outcomes. Using these strategies, teachers not only addressed specific speech difficulties but also encouraged students’ motivation and language use.

Teachers express concerns and needs about teaching pronunciation in bilingual classrooms

Despite the powerful roles teachers played, they were limited by the resources provided by the educational system. First, the optimal amount of immersion may be revisited. ‘Time is limited’ was repetitively brought up. Teacher Bai elaborated, ‘The Chinese-English bilingual [program] is not the same as … 100% immersive teaching … This is two-way bilingual, 50% in our class, but … after you leave the classroom, your environment is an English world’. Results in French immersion suggested that more immersion in the minority language was related to better learning outcomes (Genesee, Citation2004). More evidence of bilingual education in Mandarin and other minority languages is needed to decide the optimal proportion of immersion.

Second, teachers reflected on the curriculum design. In the curriculum, pronunciation is only addressed through the sound-symbol system, i.e. Pīnyīn, in grades one and two, and the focus is switched to Chinese characters in order to facilitate reading without reliance on Pīnyīn (Alberta Education, Citation2006), which is in line with the curriculum for Mandarin-L1 students in Mainland China (MOE P.R.China, Citation2012). However, given the diverse student population, spoken language proficiency should not be assumed (Duff & Doherty, Citation2019). Pronunciation may be considered as an explicit goal instead of an indirect goal that is often attached to Pīnyīn, especially for the students who are L2 learners of Mandarin, and students ‘should … first know how to pronounce (Teacher Liu)’. In addition, a continuous focus on pronunciation may help teachers justify the incidental pronunciation instruction in higher grades without feeling reluctant that they are ‘no longer supposed to learn Pīnyīn (Teacher Cheng)’.

Third, teachers reflected on their needs in teaching materials. ‘There’s no fixed textbook in North America (Teacher Bai)’. Therefore, teachers ‘could be flexible in teaching (Teacher Yi)’ and avoid the cultural inappropriateness of imported textbooks (Duff & Doherty, Citation2019). However, it also meant that teachers had to design lessons by themselves, and ‘the workload is relatively large (Teacher Bai)’. In addition to textbooks, teachers reported that the multimedia resources online were ‘not so accurate’, ‘not so appropriate (Teacher Yi)’, and sometimes ‘could only be used in China (Teacher Feng)’. Therefore, we advocate for teaching materials that are accessible, accurate, and age- and culturally appropriate for bilingual children in Canada.

Fourth, PD opportunities in pronunciation instruction can be provided considering teachers’ diverse backgrounds. Teacher Gwok stated, ‘Our mother tongue is almost English … So I think if we can have more training classes, let us go every year, we can learn more’. Meanwhile, teachers emphasized that instead of theoretical knowledge, they were interested in ‘how to apply them in practical use (Teacher Yi)’, i.e. ‘something that I can use right away (Teacher Gwok)’. This is in line with the evidence based on teacher surveys that bilingual teachers across the world are in need of training in teaching pronunciation (Couper, Citation2021; Pérez Cañado, Citation2016).

Discussion

This study presented teachers’ discussions on Mandarin pronunciation teaching and learning in a two-way bilingual program in Canada. Five themes emerged from the interviews (). The first three themes addressed the research question on teachers’ understanding of students’ Mandarin pronunciation learning. Teachers shared reflections on how Mandarin pronunciation was impacted by linguistic, individual, and social factors. The last two themes addressed the research question on teachers’ strategies and needs. Teachers reported using both direct and indirect strategies and expressed the need for more teaching time, improved curriculum design, practical PD opportunities, and teaching materials.

Findings in the first three themes confirm the challenges in pronunciation teaching (Couper, Citation2021; MacDonald, Citation2002; Murphy, Citation2011) and provide further evidence on teaching a non-English minority language (Estrada & Chacón, Citation2015; Pérez Cañado, Citation2016; Wisecup, Citation2017). In the first theme, teachers discussed the linguistic differences between Mandarin and English and therefore, lexical tones and unique speech sounds in Mandarin were challenging to teach and learn. These observations align with bilingual speech theories and empirical studies (Best & Tyler, Citation2007; Flege & Bohn, Citation2021). In the second and third themes, teachers reflected on individual factors and social factors of students’ pronunciation learning, including students’ home language backgrounds, motivation, language aptitude, teachers’ language models and language policies, and the language environment at school and in society. These reflections align with multilayered factors of bilingual language development (Paradis, Citation2011) and the importance of speech input across a variety of social contexts (Flege & Bohn, Citation2021). Such findings indicate that teachers of the bilingual program were able to provide insightful reflections on students’ pronunciation learning that were in accordance with theories and their lived experiences.

The fourth theme suggests that, in addition to observations and reflections, teachers were able to actively use teaching strategies to address the complexity of pronunciation learning. This provides further evidence that teachers are active policymakers in bilingual education who take advantage of their intuition, experience, and reflections to negotiate between language education policies and their daily practices (Menken & García, Citation2010). The next paragraphs provide two examples of how teachers performed such negotiations:

The curriculum promoted CLT approaches (Alberta Education, Citation2006; Littlewood, Citation2011), but FFI was considered more efficient when teaching pronunciation that was challenging for students (Isaacs, Citation2009; Spada & Lightbown, Citation2008). Therefore, teachers adopted a wide array of direct and indirect strategies that incorporated both FFI and CLT, ranging from articulatory cueing for a specific speech sound to the use of multimedia and games in classroom activities (Supplemental Material E). Such findings are different from previous evidence that teachers’ pronunciation teaching strategies lacked innovation and diversity (Foote et al., Citation2011; Murphy, Citation2011) and that classroom interactions in Mandarin bilingual programs were unnatural and bookish (Duff & Doherty, Citation2019). Instead, teachers were able to flexibly and innovatively choose from a variety of pronunciation strategies to address students’ learning needs and meet the curriculum’s goal of functional bilingualism (Alberta Education, Citation2006).

The program was designed to provide bilingual education for any students despite their language backgrounds (ECBEA, n.d.), but it was challenging to deliver a bilingual program to students with different levels of proficiency (Schwartz et al., Citation2016). Therefore, teachers provided gradual and continuous support without assuming the students’ proficiency and strived to balance the bilingual space by encouraging communication in Mandarin. It has been suggested that L2 learners and heritage speakers can learn in the same classroom, but further teacher training is necessary to prepare teachers for teaching multilevel and diverse groups (Duff & Doherty, Citation2019). The bilingual program in this study seems to provide a positive example where the teachers spontaneously and flexibly used teaching strategies to teach diverse groups of learners. To our knowledge, this is the first study to provide such evidence from an empowering perspective in bilingual education that focuses on pronunciation learning (see Estrada & Chacón, Citation2015; Schwartz et al., Citation2016 for studies on language learning).

Nonetheless, it is important to acknowledge teachers’ challenges and needs in their teaching practices discussed in the fifth theme and advocate for improvements. Several implications for policymakers at the systemic level can be considered to facilitate pronunciation teaching and learning in bilingual education. When designing the curriculum, policymakers can consider the optimal proportion of immersion and increase the time of exposure to the minority language (Genesee, Citation2004). They can also address pronunciation as an explicit learning goal and revisit the timeline of pronunciation goals so that it can be taught early and continuously (c.f., a French immersion curriculum where pronunciation is continually addressed in higher grade levels, Alberta Education, Citation2008). Extra support may benefit L2 learners who do not have the same level of support at home to promote additive bilingualism beyond heritage language maintenance (Cummins, Citation2017; Liu, Citation2020; Wu, Citation2005). In addition, teaching resources and PD in pronunciation instruction are frequently called for in the current and previous studies (Couper, Citation2021; Estrada & Chacón, Citation2015; Wisecup, Citation2017). Policymakers can provide accessible and appropriate teaching resources and PD training to facilitate teachers’ practice. To achieve this goal, the strategies teachers shared in this study (Supplemental Material E) can serve as a starting point for PD programs that involve phonological and phonetic knowledge and practical methods to teach pronunciation (Kochem, Citation2022; Murphy, Citation2017).

Limitations

It is essential to acknowledge the limitations of the current study. For example, the current study focuses on teaching an immigrant language in an English-dominant environment and does not involve an exhaustive literature review on pronunciation teaching in educational programs around the world. The Mandarin-English bilingual program in this study is only one example of programs where languages whose speech systems are uniquely different are being taught, acknowledging that many bilingual education programs involve other typologically unique languages. In addition, the current study includes only interview data without triangulation using other sources of data (e.g. educational policy analysis or classroom observation, Molbæk & Kristensen, Citation2020), and teachers’ self-report may not completely match their classroom practice (Foote et al., Citation2016).

Future research directions

Several future research directions are identified through the findings in the current study. Considering the diversity of world languages, pronunciation learning in non-English minority languages has been understudied compared to the learning of English as an international lingua franca (Kordíková & Brestenská, Citation2022; Probyn, Citation2001; Richter, Citation2019). In this study, teachers qualitatively reflected on students’ pronunciation learning, yet quantitative data on this topic is rare (e.g. Meckelborg et al., Citation2024; Menke, Citation2017; Nance, Citation2020; Netelanbos et al., Citation2016). Therefore, several research needs are identified based on the findings of this study. First, more developmental studies in a variety of minority languages are needed to examine the trajectory of pronunciation learning, i.e. whether bilingual students improve their pronunciation skills and whether the L2 learners can catch up to the L1-speaking students. Second, teachers discussed the important roles of students’ home language environment and learning motivation. Future research should investigate parents’ and children’s motivations for pronunciation learning and their language interaction (Paradis, Citation2011; Sardegna et al., Citation2018; Van Mensel & Deconinck, Citation2019). Third, teachers discussed the effects of teachers’ language backgrounds. Evidence suggested that English teachers’ status of nativeness did not impact speech learning outcomes (Levis et al., Citation2016), but the study was conducted among adult learners in the United States where English was the majority language. Studies are needed in minority languages and should consider not only the pronunciation outcomes but also the social and cultural values of native and non-native teachers. Finally, teachers reported using a variety of CLT and FFI techniques, but further research is needed to decide the effectiveness of the integration of these approaches (e.g. Isaacs, Citation2009).

In conclusion, the current study is among the first to investigate teaching and learning the pronunciation of an immigrant language through bilingual education in an English-dominant environment. It highlights teachers’ powerful role in bilingual education practices and provides important implications for educators and policymakers. It is important to acknowledge that teachers’ strategies shared in this study emerged from their lived experiences in a bottom-up manner, featuring individual differences. Nonetheless, this study celebrates teachers’ insights and initiatives and shares their successful experiences with the community of bilingual teachers worldwide (Fishman, Citation1976), who might be faced with similar challenges of teaching pronunciation of a minority language. Therefore, we advocate for knowledge sharing among educators, increased attention to research on pronunciation teaching, and improved language education policies and programming to support students’ bilingual development. After all, the merits of two-way bilingual education and the powerful role of bilingual teachers need to be supported by evidence-based policies and resources, where the development of bilingual education programs is viewed as a collaborative and dynamic process.

Supplementary Materials.docx

Download MS Word (38.3 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the schools, principals, and teachers who organized and participated in the interviews. Thanks to the Edmonton Chinese Bilingual Education Association (ECBEA) for their continued dedication to bilingual education and research. Thanks to Maria Pollock, Xiaozhu Chen, and Minjia Tao for their help with interview transcription and coding. Thanks to Dr. Andrea A. N. MacLeod for providing valuable insights during early discussions of this study and providing advice and suggestions for a poster presentation that was related to this manuscript. Thanks to Yina Liu for suggestions on the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Youran Lin

Youran Lin is a graduate from the combined MScSLP/PhD program and a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Alberta. Youran is interested in speech and language development in bilingual children with and without speech and language disorders and cultural and linguistic diversity in the field of speech-language pathology.

Fangfang Li

Fangfang Li is a professor in the Psychology Department at the University of Lethbridge, a phonetician, and a developmental psychologist. Fangfang’s research interests include sensorimotor development of speech sounds in preschool-aged children, gendered speech, and the speech development of English-French and English-Chinese bilinguals in Alberta, Canada.

Karen E. Pollock

Karen E. Pollock is a professor in the Department of Communication Sciences and Disorders at the University of Alberta. Karen’s research interests include speech development in children learning a second language, speech-language acquisition in children adopted internationally, and vowel errors produced by young children with and without speech sound disorders.

References

- Alberta Education. (2006). Chinese language arts kindergarten to Grade 9. International Languages, Programs of Study. Retrieved from https://education.alberta.ca/international-languages-k-6/programs-of-study/

- Alberta Education. (2008). Programme d’éducation pour la maternelle. French Language Arts (M à 12), Programmes d‘études. Retrieved from https://education.alberta.ca/french-language-arts-m-%C3%A0-12/programmes-d%C3%A9tudes/

- Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada. (2013). Canada’s Asia challenge: Creating competence for the next generation of Canadians. Retrieved from http://www.asiapacific.ca/sites/default/files/filefield/asia_competence_tf_-_final_revised_report.pdf

- Baker, A. (2014). Exploring teachers’ knowledge of second language pronunciation techniques: Teacher cognitions, observed classroom practices, and student perceptions. TESOL Quarterly, 48(1), 136–163. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.99

- Baker, C. (2007). Becoming bilingual through bilingual education. In P. Auer & W. Li (Eds.), Handbook of multilingualism and multilingual communication (pp. 131–152). Walter de Gruyter.

- Baker, C., Andrews, H., Gruffydd, I., & Lewis, G. (2011). Adult language learning: A survey of Welsh for Adults in the context of language planning. Evaluation & Research in Education, 24(1), 41–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500790.2010.526204

- Banda, F. (2000). The dilemma of the mother tongue: Prospects for bilingual education in South Africa. Language Culture and Curriculum, 13(1), 51–66.

- Best, C. T., & Tyler, M. (2007). Nonnative and second-language speech perception. Nonnative and second-language speech perception: Commonalities and complementarities. In M. J. Munro & O.-S. Bohn (Eds.), Second language speech learning: The role of language experience in speech perception and production (pp. 13–34). John Benjamins.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Çağatay, S. (2021). Identity clashes of EFL instructors in Turkey with regard to pronunciation and intonation in English. International Journal of Curriculum and Instruction, 13(3), 2557–2584.

- Celce-Murcia, M., Brinton, D. M., & Goodwin, J. M. (1996). Teaching pronunciation: A reference for teachers of English to speakers of other languages. Cambridge University Press.

- Chang, C. B., Yao, Y., Haynes, E. F., & Rhodes, R. (2011). Production of phonetic and phonological contrast by heritage speakers of Mandarin. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 129(6), 3964–3980. https://doi.org/10.1121/1.3569736

- Chao, Y.-R. (1930). A system of tone letters. Le Maître Phonétique, 8(45), 24–27.

- Chen, X., Anderson, R. C., Li, W., Hao, M., Wu, X., & Shu, H. (2004). Phonological awareness of bilingual and monolingual Chinese children. Journal of Educational Psychology, 96(1), 142–151. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.96.1.142

- Copland, F., & Yonetsugi, E. (2016). Teaching English to young learners: Supporting the case for the bilingual native English speaker teacher. Classroom Discourse, 7(3), 221–238. https://doi.org/10.1080/19463014.2016.1192050

- Couper, G. (2021). Pronunciation teaching issues: Answering teachers’ questions. RELC Journal, 52(1), 128–143. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033688220964041

- Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2023). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (6th ed.). SAGE publications.

- Cummins, J. (1979). Linguistic interdependence and the educational development of bilingual children. Review of Educational Research, 49(2), 222–251. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543049002222

- Cummins, J. (1981). Empirical and theoretical underpinnings of bilingual education. Journal of Education, 163(1), 16–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/002205748116300104

- Cummins, J. (2017). Teaching for transfer in multilingual school contexts. Bilingual and Multilingual Education, 1, 103–116.

- David, M. K., Cavallaro, F., & Coluzzi, P. (2009). Language policies-impact on language maintenance and teaching: Focus on Malaysia, Singapore, Brunei and the Philippines. Linguistics Journal, 4, 155–191.

- Derwing, T. M. (2020). Integrating multiple views and multiple disciplines in the understanding of child bilingualism and second language learning. In F. Li, K. E. Pollock, & R. Gibb (Eds.), Child bilingualism and second language learning: Multidisciplinary perspectives (pp. 29–41). John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- Derwing, T. M., Fraser, H., Kang, O., & Thomson, R. I. (2014). L2 accent and ethics: Issues that merit attention. In A. Mahboob & L. Barratt (Eds.), Englishes in multilingual contexts (pp. 63–80). Springer.

- Dicks, J., & Genesee, F. (2017). Bilingual education in Canada. In O. García, A. M. Y. Lin, & S. May (Eds.), Bilingual and multilingual education (pp. 453–467). Springer.

- Duff, P., & Doherty, L. (2019). Learning Chinese as a heritage language: Challenges, issues and ways forward. In C-R. Huang, Z. Jing-Schmidt, & B. Meisterernst (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of Chinese applied linguistics (pp. 149–164). Routledge.

- Edmonton Chinese Bilingual Education Association (ECBEA). (n.d). About the program. Edmonton Chinese Bilingual Education Association. Retrieved from https://www.ecbea.org/about-the-program/

- Estrada, P. L., & Chacón, A. M. (2015). A teacher’s tensions in a Spanish first grade two-way bilingual immersion program. Revista Portuguesa de Educação, 28(2), 211–229. https://doi.org/10.21814/rpe.7752

- Fishman, J. A. (1976). Bilingual education: An international sociological perspective. ERIC.

- Flege, J. E. (1995). Second language speech learning: Theory, findings, and problems. In W. Strange (Ed.), Speech perception and linguistic experience: Issues in cross-language research (pp. 233–277). York Press.

- Flege, J. E., & Bohn, O.-S. (2021). The revised speech learning model (SLM-r). In R. Wayland (Ed.), Second language speech learning: Theoretical and empirical progress (pp. 3–83). Cambridge University Press.

- Flege, J. E., Munro, M. J., & MacKay, I. R. (1995). Factors affecting strength of perceived foreign accent in a second language. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 97(5 Pt 1), 3125–3134. https://doi.org/10.1121/1.413041

- Foote, J. A., Holtby, A. K., & Derwing, T. M. (2011). Survey of the teaching of pronunciation in adult ESL programs in Canada, 2010. TESL Canada Journal, 29(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.18806/tesl.v29i1.1086

- Foote, J. A., Trofimovich, P., Collins, L., & Urzúa, F. S. (2016). Pronunciation teaching practices in communicative second language classes. The Language Learning Journal, 44(2), 181–196. https://doi.org/10.1080/09571736.2013.784345

- Gardner, R. C., & Lambert, W. E. (1972). Attitudes and motivation in second-language learning. Newbury House Publishers.

- Genesee, F. (2004). What do we know about bilingual education for majority language students?. In T. K. Bhatia & W. Ritchie (Eds.), Handbook of bilingualism and multiculturalism (pp. 547–576). Blackwell.

- Genesee, F., & Lindholm-Leary, K. (2008). Dual language education in Canada and the USA. Encyclopedia of Language and Education, 2(5), 253–263.

- Isaacs, T. (2009). Integrating form and meaning in L2 pronunciation instruction. TESL Canada Journal, 27(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.18806/tesl.v27i1.1034

- Jenkins, J. (2007). English as a Lingua Franca: Attitude and Identity. Oxford University Press.

- Kennedy, S., & Trofimovich, P. (2017). Pronunciation acquisition. In S. Loewen & M. Sato (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of instructed second language acquisition (pp. 260–279). Routledge.

- Kent, R. D. (1992). The biology of phonological development. In C. A. Ferguson, L. Menn, & C. Stoel-Gammon (Eds.), Phonological development: models, research, implications (pp. 65–90). York Press.

- Kochem, T. (2022). Exploring the connection between teacher training and teacher cognitions related to L2 pronunciation instruction. TESOL Quarterly, 56(4), 1136–1162. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.3095

- Kordíková, B., & Brestenská, B. (2022). Bilingual science education: perceptions of Slovak in-service and pre-service teachers. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 25(2), 728–741. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2020.1718590

- Lambert, W. E., Genesee, F., Holobow, N., & Chartrand, L. (1993). Bilingual education for majority English-speaking children. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 8(1), 3–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03172860

- Lee-Kim, S. I. (2014). Revisiting Mandarin ‘apical vowels’: An articulatory and acoustic study. Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 44(3), 261–282. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0025100314000267

- Levis, J. (2020). Revisiting the intelligibility and nativeness principles. Journal of Second Language Pronunciation, 6(3), 310–328. https://doi.org/10.1075/jslp.20050.lev

- Levis, J. M., Sonsaat, S., Link, S., & Barriuso, T. A. (2016). Native and nonnative teachers of L2 pronunciation: Effects on learner performance. TESOL Quarterly, 50(4), 894–931. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.272

- Levis, J., & Sonsaat, S. (2017). Pronunciation teaching in the early CLT era. In O. Kang, R. I. Thomson, & J. M. Murphy (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of contemporary English pronunciation. (pp. 267–283). Routledge.

- Li, F., & Munson, B. (2016). The development of voiceless sibilant fricatives in Putonghua-speaking children. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research: JSLHR, 59(4), 699–712. https://doi.org/10.1044/2016_JSLHR-S-14-0142

- Lin, L. C., & Johnson, C. J. (2010). Phonological patterns in Mandarin–English bilingual children. Clinical Linguistics & Phonetics, 24(4-5), 369–386. https://doi.org/10.3109/02699200903532482

- Littlewood, W. (2011). Communicative language teaching: An expanding concept for a changing world. In E. Hinkel (Ed.), Handbook of research in second language teaching and learning (Vol. 2) (pp. 541–557). Routledge.

- Liu, W. (2020). Success factors for a Mandarin bilingual program: An autoethnographic case study. Chinese as a Second Language (漢語教學研究—美國中文教師學會學報), 55(3), 208–229.

- MacDonald, S. (2002). Pronunciation-views and practices of reluctant teachers. Prospect, 17(3), 3–18.

- MacLeod, A. A., & Stoel-Gammon, C. (2010). What is the impact of age of second language acquisition on the production of consonants and vowels among childhood bilinguals? International Journal of Bilingualism, 14(4), 400–421. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367006910370918

- Major, R. C. (2001). Foreign accent: The ontogeny and phylogeny of second language phonology. Routledge.

- May, S., & Hill, R. (2005). Māori-medium education: Current issues and challenges. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 8(5), 377–403. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050508668621

- McLeod, S., & Crowe, K. (2018). Children’s consonant acquisition in 27 languages: A cross-linguistic review. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 27(4), 1546–1571. https://doi.org/10.1044/2018_AJSLP-17-0100

- Meckelborg, A., Luu, M., Nguyen, T., Lin, Y., Li, F., & Pollock, K. (2024). Acquisition of Mandarin tones by Canadian first graders: Effect of prior exposure to tonal and non-tonal languages. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 155(2), 1608–1623. https://doi.org/10.1121/10.0024985

- Menke, M. R. (2017). Phonological development in two-way bilingual immersion: The case of Spanish vowels. Journal of Second Language Pronunciation, 3(1), 80–108. https://doi.org/10.1075/jslp.3.1.04men

- Menken, K., & García, O. (2010). Negotiating language education policies: Educators as policymakers. Routledge.

- Meziane, R. S., & MacLeod, A. A. N. (2020). Integrating multiple views and multiple disciplines in the understanding of child bilingualism and second language learning. In F. Li, K. E. Pollock, & R. Gibb (Eds.), Child bilingualism and second language learning: Multidisciplinary perspectives (pp. 9–27). John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China (MOE P.R.China). (2012). The Elementary School Chinese Curriculum in Compulsory Education Period – Revised. People’s Education Press. [In Chinese]

- Molbæk, M., & Kristensen, R. M. (2020). Triangulation with video observation when studying teachers’ practice. Qualitative Research Journal, 20(1), 152–162. https://doi.org/10.1108/QRJ-07-2019-0053

- Murphy, D. (2011). An investigation of English pronunciation teaching in Ireland. English Today, 27(4), 10–18. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266078411000484

- Murphy, J. M. (2017). Teacher training in the teaching of pronunciation. In O. Kang, R. I. Thomson, & J. M. Murphy (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of contemporary English pronunciation (pp. 298–319). Routledge.

- Nance, C. (2020). Bilingual language exposure and the peer group: Acquiring phonetics and phonology in Gaelic Medium Education. International Journal of Bilingualism, 24(2), 360–375. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367006919826872

- Netelenbos, N., Li, F., & Rosen, N. (2016). Stop consonant production of French immersion students in Western Canada: A study of voice onset time. International Journal of Bilingualism, 20(3), 346–357. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367006914564566

- Ngwenya, T. (2010). Negotiating a nuanced task-based communicative syllabus of Setswana as an additional language. Journal for Language Teaching, 43(1), 115–133. https://doi.org/10.4314/jlt.v43i1.56963

- Noels, K. A., Pelletier, L. G., Clément, R., & Vallerand, R. J. (2000). Why are you learning a second language? Motivational orientations and self‐determination theory. Language Learning, 50(1), 57–85. https://doi.org/10.1111/0023-8333.00111

- Paia, M., Cummins, J., Nocus, I., Salaün, M., & Vernaudon, J. (2015). Intersections of language ideology, power, and identity: Bilingual education and indigenous language revitalization in French Polynesia. In W. E. Wright, S. Boun, & O. García (Eds.), The handbook of bilingual and multilingual education (pp. 145–163). Wiley.

- Paradis, J. (2011). Individual differences in child English second language acquisition: Comparing child-internal and child-external factors. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism, 1(3), 213–237. https://doi.org/10.1075/lab.1.3.01par

- Peel, K. L. (2020). A beginner’s guide to applied educational research using thematic analysis. Practical Assessment. Research, and Evaluation, 25(2), Article 2.

- Pérez Cañado, M. L. (2016). Teacher training needs for bilingual education: In-service teacher perceptions. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 19(3), 266–295. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2014.980778

- Place, S., & Hoff, E. (2016). Effects and noneffects of input in bilingual environments on dual language skills in 2 ½-year-olds. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 19(5), 1023–1041. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1366728915000322

- Probyn, M. (2001). Teachers voices: Teachers reflections on learning and teaching through the medium of English as an additional language in South Africa. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 4(4), 249–266. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050108667731

- Richter, K. (2019). English-medium instruction and pronunciation: Exposure and skills development. Multilingual Matters.

- Riestenberg, K., & Sherris, A. (2018). Task-based teaching of indigenous languages: Investment and methodological principles in Macuiltianguis Zapotec and Salish Qlispe revitalization. Canadian Modern Language Review, 74(3), 434–459.

- Robinson, P. (2005). Aptitude and second language acquisition. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 25, 46–73. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0267190505000036

- Saito, K., Suzukida, Y., & Sun, H. (2019). Aptitude, experience, and second language pronunciation proficiency development in classroom settings: A longitudinal study. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 41(1), 201–225. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0272263117000432

- Sakamoto, M. (2012). Moving towards effective English language teaching in Japan: Issues and challenges. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 33(4), 409–420. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2012.661437