?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has significantly impacted mental well-being, leading to increased stress, anxiety, and social isolation, particularly affecting students’ self-confidence and academic performance. This study aims to establish the relationship between anxiety levels and student satisfaction with distance learning in taxation during the pandemic. The study is conducted quantitatively using surveys and explicitly targets students from Brawijaya University’s Taxation Study Program in Indonesia. This program was chosen because its distinctive curriculum combines theoretical and practical tax components, making it difficult to reproduce online. The research sample was taken using purposive sampling. It reveals that anxiety, directly and indirectly, influences student satisfaction during distance learning, with higher mental pressure correlating with lower satisfaction levels. These findings suggest administrators should consider academic factors in online learning to boost satisfaction and alleviate anxiety. However, the study’s specificity to Brawijaya University’s Taxation Program warrants caution against universal application. Future research could explore additional moderating variables such as learning motivation, skills, social support, and technology readiness to understand students’ diverse learning experiences better.

Reviewing Editor:

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020 triggered widespread concern in multiple countries worldwide. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the education sector should adopt remote learning. Implementing lockdown measures and social distancing regulations is widely recognized as the most effective method for reducing educational inequalities (UNESCO, Citation2020). Distance education is a form of learning that physically separates the student and teacher from each other in terms of time and distance (Khamidzhanovna & Rakhmatullaevna, Citation2022). This learning strategy involves a physical distance between the instructor and the learner. The advantages of this learning strategy include the ability to study at any location and time, enhanced communication, efficient use of time and resources, the freedom to select learning techniques, and the possibility of combining work with learning (Sadeghi, Citation2019). Nevertheless, the change in the educational methodology has noteworthy repercussions. Both students and instructors need help adjusting to the abrupt shift from face-to-face lectures to online instruction.

Anxiety regarding their social isolation harms the students’ self-confidence. It can significantly impair a student’s academic performance (Ajmal et al., Citation2019; Bandura, Citation1977; Bollinger, Citation2017). A study examined the effects of distance learning on students’ mental health and found that the most significant issues were insufficient time management, the absence of a comprehensive adaptation strategy, the need to adapt to new digital technologies, the responsibility of ensuring the quality of new learning materials, and concerns about the inability to finance educational activities during the COVID-19 pandemic (Aditya & Ulya, Citation2021). Besides that, increasing academic self-efficacy (ASE) impacts students’ motivation to complete new assignments (Wäschle et al., Citation2014). Enhanced student confidence in effectively accomplishing online tasks or materials will bolster their motivation to acquire knowledge, resulting in elevated student contentment with online learning (Abdolrezapour et al., Citation2023).

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a substantial influence on mental well-being, resulting in heightened levels of stress, anxiety, and social seclusion (Fancourt et al., Citation2021; Szcześniak et al., Citation2019; Torales et al., Citation2020). The influence above has had a significant effect, especially on susceptible demographics such as women, younger adults, individuals with limited educational achievements, and those from minority ethnic backgrounds (Fancourt et al., Citation2021). Educational institutions should allocate resources and provide support services focusing on addressing the psychological effects experienced by students and educators (Szcześniak et al., Citation2019; Torales et al., Citation2020). Students need to enhance twenty-first-century skills, such as critical thinking, creativity, and teamwork, to confront future difficulties effectively. Education may effectively respond to these issues and cater to students’ evolving demands in a dynamic environment (Vasil et al., Citation2018).

From an emotional point of view, this research integrates Emotion Theory in the learning process. The theory of emotions in learning highlights the role of emotions in the learning experience and how emotions can influence students’ cognitive processes and perceptions of learning (Samost-Williams & Minehart, Citation2022). Emotions play a crucial role in the learning process, influencing both the cognitive and affective domains of learning. Research has shown that emotions can significantly impact learning outcomes (Wortha et al., Citation2019). Positive emotions have been associated with better learning results as they foster motivation, while negative emotions can hinder learning (Hu & Chen, Citation2022). Emotions are intertwined with the learning process and are not separate from the learning environment (Cleveland-Innes & Campbell, Citation2012). The impact of emotions on learning is evident in various contexts, including online learning (Jumaat & Termidi, Citation2022), service-learning (Martin et al., Citation2017), and collaborative online activities (Hilliard et al., Citation2020).

In the context of distance learning anxiety, emotions such as anxiety, frustration, and discomfort may arise and impact the student’s overall learning experience. Distance Learning Anxiety (X) describes the level of anxiety experienced by students when learning remotely. Distance Learning Satisfaction (Y) describes the level of student satisfaction with their distance learning experience. Meanwhile, Grade (Z) describes students’ previous learning experiences, which can influence how they deal with anxiety and respond emotionally to learning experiences. By integrating the Theory of Emotions in learning with relevant variables in the context of distance learning anxiety and learning satisfaction, and considering learning experience as a moderating variable, this research can develop a strong grand theory to understand the influence of distance learning anxiety from an emotional perspective.

Students frequently experience concerns such as anxiety, different levels of stress, fatigue from excessive social media usage, and sadness. Nevertheless, there are instances where the symptoms are not primarily attributable to mental health conditions (Grigorkevich et al., Citation2022). In addition, student satisfaction and emotional experiences can be influenced by factors such as the course’s clarity, pace, and difficulty. Higher levels of understandability and illustration can increase satisfaction and lower negative emotions, such as anxiety and boredom (Ghaderizefreh & Hoover, Citation2018). Moreover, the COVID-19 epidemic has required a move to remote learning, and research has indicated that this change has resulted in heightened levels of worry and tension among students (Mazlan & Sumarjan, Citation2022). Hence, it is imperative to tackle anxiety within the framework of online education in order to safeguard the mental health and contentment of students.

Academic emotions, arising from cognitive appraisals of control over the learning task and value in the learning activity, have reciprocal connections with antecedents and consequents, affecting the learning experience (D’Mello & Graesser, Citation2012). Emotions are considered both outcomes and predictors of learning, with fluctuations in student emotions being understood within the context of situated learning (Maidment & Crisp, Citation2011). Learners’ emotions significantly impact learning processes and regulation strategies (Lavoue et al., Citation2017).

Anxiety and psychological stress have been identified as significant factors affecting student well-being and academic performance in the context of remote education, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic (Pelucio et al., Citation2022). The increased levels of anxiety among students during the pandemic have been well-documented (Oliveira et al., Citation2022). Research has observed that anxiety tends to exacerbate in distant learning settings due to heightened isolation and diminished social support (Gorriz et al., Citation2022). The influence of anxiety on students’ pleasure has a substantial effect on the outcome of online learning, thereby affecting their academic achievement (Lai et al., Citation2021). Therefore, educational institutions must understand the emotional repercussions of anxiety on student happiness. Comprehending this is crucial for devising effective techniques to handle anxiety and tension and providing necessary emotional and psychological support to students in an online learning environment. Moreover, it has been stressed that it is imperative to tackle anxiety and psychological obstacles in online learning to improve the calibre and efficacy of remote education, especially amid the COVID-19 epidemic (Gorriz et al., Citation2022).

The challenge in implementing education today is effective and inclusive learning in today’s educational landscape, which requires solving difficulties by integrating technology and ensuring equity and inclusion. Technology integration is crucial in response to the rapid expansion of digital tools and platforms. It involves addressing challenges related to digital accessibility, providing training for educators, and devising suitable learning methodologies (Khan & Ali, Citation2023; Talib et al., Citation2021). It is becoming increasingly crucial to tackle inequalities in educational opportunities, cater to varied learning requirements, and establish inclusive learning environments (Skiba et al., Citation2006; Stanley et al., Citation2017). Addressing these obstacles is crucial for fostering student diversity and promoting successful learning outcomes (Ackerman & Busija, Citation2012; Ramadan et al., Citation2021). Technologies for remote education delivery, such as telemedicine and tele-education, are vital in supporting students’ mental health and well-being, especially during crises like the COVID-19 pandemic (Sharma & Bhaskar, Citation2020). Studies have demonstrated that the transition to remote learning due to the pandemic has posed challenges for students, particularly in science and mathematics fields, impacting their academic performance and increasing stress levels (Franco et al., Citation2023). However, leveraging available technological tools and platforms can help address these challenges and ensure continuity in learning (Nasri et al., Citation2020).

While emergency remote teaching may not always result in high levels of student satisfaction, incorporating interactive technologies and distance learning methods can positively influence students’ learning experiences and engagement (Rybakova et al., Citation2021). Factors like self-regulated effort, flexibility, and satisfaction are essential in enhancing students’ experiences in distance education (Turan et al., Citation2022). Additionally, the use of intelligent tutoring systems and high-quality services can further enhance student satisfaction, task-technology fit, and learning motivation, ultimately improving learning performance (Yuce et al., Citation2019).

Prior studies solely focused on exploring the correlation between anxiety and learning satisfaction without delving into any disparities in anxiety levels and satisfaction among participants in emergency distance learning, taking into account the learning experience of each academic group. The outcome needs to be a more comprehensive comprehension of pupils’ worries and happiness, which raises the probability of mishandling. Hence, the objective of this study is to fill the research voids indicated in the studies conducted by Abdous and Yen (Citation2010), Abdous (Citation2019), and Spitzer et al. (Citation2006) by examining the influence of anxiety on satisfaction with distant learning. Furthermore, this study examines fluctuations in anxiety levels and satisfaction with distance learning across several grades.

2. Literature review

2.1. Distance learning anxiety

The phrases "fear" and "anxiety" possess distinct definitions. Anxiety is an emotion contingent on the future and characterized by the anticipation of terrible events (Barlow, Citation2002). On the other hand, fear is a rational response to imminent danger. Anxiety in distance learning refers to the psychological condition experienced by students while learning remotely. It is characterized by feelings of fear, worry, lack of confidence, and anxiety (Sara, Citation2022). Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) is a highly prevalent mental illness. Unfortunately, no clinical measures exist to evaluate the syndrome (Spitzer et al., Citation2006). Adult women have a higher likelihood of experiencing Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) compared to adult men, but it is possible. This type of psychiatric disorder is exceedingly rare among youngsters. The criteria utilized to evaluate Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) exhibit more significant variability compared to the criteria employed for diagnosing other types of mental disorders (Wittchen, Citation2001).

A study determined the most effective items for assessing Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) (Spitzer et al., Citation2006). The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition (DSM – IV) was delineated through the utilization of assessment items. Nevertheless, a rudimentary examination to ascertain the existence or nonexistence of worry comprises four evaluation components. Consequently, a total of 13 evaluation questions were used to measure the overall level of anxiety. The screening encompassed seven assessment criteria to evaluate the presence of anxiety disorders. Psychological symptoms associated with stress include worry, fear, difficulty in relaxation, restlessness, impatience, and a sense of impending doom (Manzar et al., Citation2021).

2.2. Distance learning satisfaction

The discrepancy between what is expected and what is experienced can quantify satisfaction. Learning satisfaction is strongly related to learning motivation. Learning satisfaction refers to the instructional process and can be determined according to the amount of time and effort students devote to it (Yang et al., Citation2016). Students’ satisfaction refers to a temporary mindset that arises from assessing students’ educational experience, services, and facilities. Initially assessed through universal satisfaction frameworks, higher education-specific satisfaction models emerged subsequently (Weerasinghe et al., Citation2017).

Defining student happiness is a challenging task due to its intricate nature. Satisfaction pertains to the positive expectations regarding providing services, specifically in the context of students. It is multifaceted, and the literature on student satisfaction abnormally agrees with this (Teeroovengadum et al., Citation2019). Multiple elements can affect student satisfaction with distance learning with online media. Educator attitudes, technological dependability, and student interaction are among these aspects. Another study discovered that the faculty’s response to student needs and technological issues is critical to student happiness (Siming et al., Citation2015).

2.3. Research hypotheses

A previous study identified several problems in Australian institutions from 2001 to 2007 due to distance learning. Isolation stems from limited face-to-face interactions and a need for computer skills. Obstacles such as discrepancies in time zones, unstable internet connectivity, and inadequate technological staff expertise impede the effective execution of synchronous learning (Lyubetsky et al., Citation2021). Amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, a study revealed that students engaged in distant learning encountered elevated levels of anxiety, sadness, and stress in contrast to their counterparts in traditional face-to-face education. A survey conducted on Malaysian students attending vocational schools revealed that 30% of them reported experiencing severe anxiety, and 41% reported suffering from chronic stress (Wang, Citation2023).

A cross-sectional study in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, revealed that younger pupils exhibited higher levels of anxiety compared to older students. However, there was no statistically significant disparity in depressive symptoms (Pelucio et al., Citation2022). As the learning process’s duration lengthens, the concern diminishes. The grade variable represents a student’s educational experience in lectures. Thus, as a student’s grade level increases, their acquisition of college experience also increases.

According to the findings of a study, there is a clear correlation between the anxiety levels of students and their level of readiness (Hachey et al., Citation2014). Multiple variables influence a student’s readiness to participate in distance learning. One determining component is the generation’s year. Younger students in a new cohort may likely feel more anxiety in contrast to their older counterparts in the senior class. It refers to the educational experience that youngsters go through (Abdous, Citation2019). Distance learning employs computer-based instruction, which prioritizes the development of a system that considers each learner’s unique characteristics. How a learner embraces a specific computer-based learning system can impact their level of anxiety during the learning process with the system (Tlili et al., Citation2016).

According to specific research, satisfaction with academic programs tends to remain consistent during the entire four years of study (Kim & Baek, Citation2020). Nevertheless, other research suggests that undergraduate students’ competencies and educational happiness favourably impact their competencies and contentment in the subsequent year (Grayson, Citation2004). Furthermore, the level of contentment with the educational encounter can be impacted by diverse circumstances, including gender, age, duration of enrollment, and quantity of failed courses. Moreover, academic motivation contributes to happiness since a greater degree of autonomous motivational orientation is associated with increased satisfaction in the study (Melita et al., 2019).

Enhanced learning opportunities are crucial in helping students manage stress and anxiety associated with remote learning. By offering a wider range of learning experiences, students can develop effective strategies for addressing challenges like time management, accessing additional resources, and overcoming technical difficulties in online learning environments. Research indicates that a more comprehensive educational experience can lead to reduced anxiety levels and increased student satisfaction with distance learning systems (Cidral et al., Citation2018).

This study employs the use of Grades to illustrate students’ educational experiences. Enhanced educational experiences can enhance students’ capacity to effectively cope with stress and anxiety from engaging in distance learning. Students with a more extensive range of learning experiences are likely to possess more effective approaches for addressing the difficulties associated with online learning, such as time management, locating supplementary materials, and overcoming technical obstacles. Thus, a more extensive educational encounter can reduce the impact of DLS by diminishing anxiety levels and enhancing student satisfaction levels in remote education.

Current evidence suggests a clear connection between anxiety levels and satisfaction with distance learning among students, indicating that increased anxiety is typically associated with decreased satisfaction (Gorriz et al., Citation2022). Previous research underscores the role of computer anxiety in determining satisfaction among e-learners (Sadaf et al., Citation2019), while recent studies emphasize the impact of anxiety on student engagement and performance during remote learning, particularly amid the pandemic (Kim & Park, Citation2021). Investigations into e-learning services highlight various factors influencing satisfaction, such as behavioral attitude and perceived utility (Kolug & Kankam, Citation2023). Similarly, studies on course design reveal that clear and comprehensive layouts contribute to greater student enjoyment and reduced anxiety (Sadaf et al., Citation2019). However, further research is needed to validate these findings and refine our understanding of the intricate relationship between anxiety and satisfaction in the context of distance learning (Gabrovec et al., Citation2022). The results of this research illustrate that each group of students in the sample has different experiences related to satisfaction with distance learning. It results in varying levels of anxiety, so the satisfaction felt by each student will be extra.

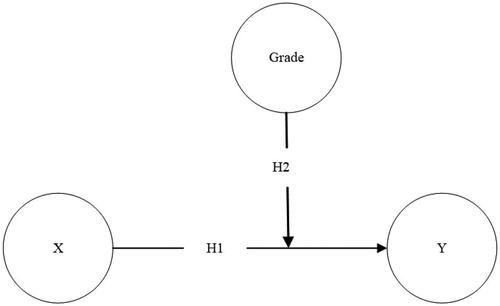

shows independent variables (X) is Distance Learning Anxiety (DLA). Then, dependent variable (Y) is Distance Learning Satisfaction (DLS). Grade as moderation variable. also describe total item question in the questioners.

This study investigated three assumptions based on the picture in :

H1: Distance Learning Anxiety Affects Distance Learning Satisfaction.

H2: Distance Learning Anxiety Affects Distance Learning Satisfaction Throughout Grade.

2.4. Research method

This study takes a quantitative approach and employs a survey method. We use questionnaires for students of the Taxation Study Program, Faculty of Administrative Sciences, Brawijaya University, Malang, Indonesia. The Taxation Study Program was chosen as the favoured educational institution because of its distinctive curriculum that combines theoretical and practical elements of taxes, which cannot be adequately replicated through distant learning methods. Furthermore, it is essential to conduct further study that examines pedagogical approaches in taxation. The research sample was taken using purposive sampling with the following criteria:

Students have active status based on the Reporting Information System (SIMPEL) in the 2021/2022 academic year

Students do not have the status of having withdrawn or are in terminal status, on leave, registered, or not registered

Students are still studying in the 2021/2022 academic year

Student satisfaction in distant learning was influenced by worry, as shown by the background. Anxiety was assessed using seven measurement items outlined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition (DSM-IV). The level of expertise students provokes the stress that emerges in learning. The grade as a moderating variable influencing the level of satisfaction in distant learning during the COVID-19 epidemic. The grade serves as a standard by which we assess the different learning methodologies. The grade can impact the level of student satisfaction with online learning.

We utilized Google Forms to provide surveys to currently enrolled students who participated in tax courses from 2016 to 2020. Cluster sampling is a commonly employed research sampling approach. This approach involves partitioning the target population into many clusters, from which a random selection of sample clusters is made (Ghozali, Citation2016). The categorization is based on fundamental classes: freshmen, sophomores, juniors, and seniors. In 2020, the term “first-year students” referred to students in their first year of study. In 2019, “Sophomore students” were students in their second year. In 2018, "Junior students" were in their third year. Lastly, “Senior students” were students in 2016 and 2017. A total of 469 questionnaires were utilized in the data processing.

The questionnaire was created by generating evaluation items based on some prior research, including Abdous and Yen (Citation2010), Spitzer et al. (Citation2006), and Abdous (Citation2019). A Likert Scale with a score of 1 to 5 to measure each item of each variable. The statement “Very Not Good” gets a score of 1, “Not Good” gets a score of 2, “Medium” gets a score of 3, “Good” gets a score of 4, and “Very Good” gets a score of 4. The statement items and reference sources are shown in . lists the statement elements as well as the reference sources used.

Table 1. Statement item of distance learning anxiety (X).

Table 2. Statement item of distance learning satisfaction (Y).

The data processing technique used the SEM method based on Partial Least Square (PLS) using SMART PLS version 3.3.3 software. In PLS, there are two stages of testing, namely, evaluation of the outer or measurement model and assessment of the inner or structural model. The measurement model consists of observable indicators. This test also estimates path coefficients that identify the strength of the relationship between the independent and dependent variables. The measurement model consists of the relationship between the observable variable items and the latent construct measured by these items.

3. Result

3.1. Demographics

According to the results of the descriptive statistical analysis (), male tax students experienced the highest average level of distance learning anxiety (DLA) during the Covid-19 epidemic, with a score of 3.08. Nevertheless, this figure deviates slightly from the DLA for female tax students, which stood at 3.00. According to the grade level, sophomores have the highest mean DLA score of 3.14, whereas seniors have the lowest mean DLA score of 2.80. Nevertheless, there is only a slight disparity in DLA scores among tax students, as sophomores achieve a score of 3.14 while juniors obtain a score of 3.10. In contrast to the average DLA calculations, female tax students exhibit a greater average distance learning satisfaction (DLS) during the Covid-19 epidemic compared to male tax students (3.22 versus 3.34). Nevertheless, this ratio also exhibits a slight disparity. The average DLS based on grade has a limited range, with juniors having the highest average DLS (3.33) and seniors having the lowest (3.27). Meanwhile, sophomores possess an average DLS of 3.32, while freshmen have an average DLS of 3.29.

Table 3. Demographics.

3.2. Measurement model evaluation (outer model)

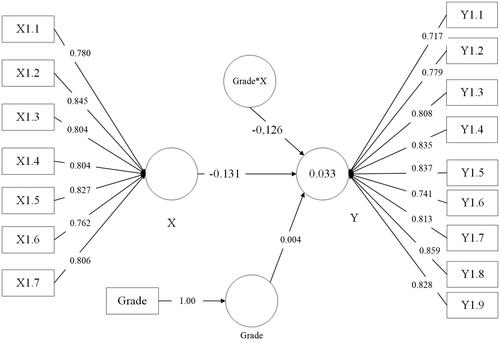

Three criteria for using data analysis techniques with SMART PLS to assess the outer model are convergent validity, discriminant validity, and composite reliability. Convergent validity aims to determine the validity of each relationship between indicators and their latent variables. The concurrent validity of the measurement model with reflexive indicators is assessed based on PLS's correlation between the component and construct scores. The value of loading factors above 0.7 is ideal and valid. However, loading factor values above 0.5 are still acceptable. Based on the PLS testing, each indicator’s convergent validity value in shows the factor loading value > 0.7. It is valid. Thus, all the loading factor values of the distance learning anxiety and distance learning satisfaction indicators are more significant than 0.7 (> 0.7), so these indicators are valid.

Discriminant validity proves that the latent construct predicts their block’s size better than the others. The tests are assessed based on cross-loading measurements with constructs. Suppose the correlation of the construct with the primary measurement (each indicator) is more significant than the size of the other constructs. The latent construct predicts the indicator better than the other constructs. The research model has good discriminant validity if each loading value of each indicator of a latent variable has the most considerable loading value compared to different loading values of other latent variables. shows the results of the tests carried out.

Table 4. Cross loading value.

All indicators that make up each variable in this study (in bold) have fulfilled discriminant validity based on the cross-loading value. When compared to other loading values of other latent variables, each loading value of each indication of a latent variable has the highest loading value. As a result, discriminant validity fulfilled all indicators in each variable in this study. Another outer model assessment is composite reliability and Cronbach alpha from the indicator block that measures the construct. The construct is declared reliable if the combined reliability and Cronbach alpha values are exceed 0.7. The value of composite reliability for the construct of batch and class*X is 1. Meanwhile, the composite reliability value for construct X is 0.928, and for construct Y, it is 0.944. Thus, each construct has good reliability.

3.3. Structural model evaluation (inner model)

The next test is an investigation of the inner model. The test examines the link between the R2 and the significant value components of the research model. The structural testing model uses R2 for the dependent construct of the t-test and the significance of the coefficients of the structural path parameters. shows the structural model of the research.

This study uses exogenous variables influenced by other variables, namely the distance learning satisfaction variable. It is affected by distance learning anxiety and year of class. The R-Square value of 0.033 shows that distance learning anxiety and grade affect distance learning satisfaction (Y). Other variables outside the study influence the remaining 96.7%.

3.4. Research hypothesis testing

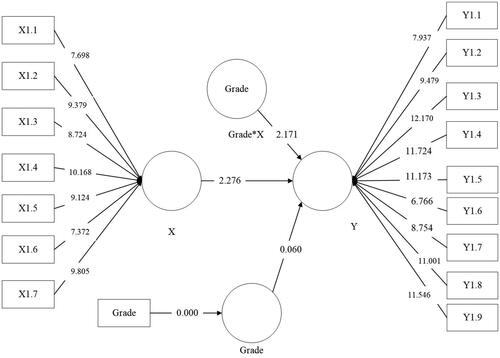

In PLS, we conduct statistical testing of each hypothesized relationship through simulation. This research uses the bootstrap method on the sample. Testing with Bootstrap is also intended to minimize the problem of abnormal research data. shows the test results by bootstrapping from the PLS analysis.

Table 5. Path coefficient.

The structural equations obtained are as follows:

The test compares the t-statistics of each hypothesis with the t-table for 469 respondents, which is 1.960. The first hypothesis is that distance learning anxiety directly affects distance learning satisfaction. The t-statistic value of the first hypothesis is 2.276, which is greater than the t-table value (1.96), and the p-value of 0.023 is less than 0.05 (0.023 < 0.05). Thus, the first hypothesis is accepted because the value of t-statistics > t-table and p-values <0.05. Distance learning anxiety has a negative and significant effect on distance learning satisfaction.

The second hypothesis is that distance learning anxiety affects distance learning satisfaction with the year of class as moderation. The t-statistic value of the second hypothesis is 2.171, which is greater than the t-table value (1.96). In addition, the p-values of 0.03 are smaller than 0.05 (0.03 < 0.05). Thus, the third hypothesis is accepted because the t-statistic value is greater than the t-table value, and the p-value is < 0.05.

4. Discussion

The conducted experiments indicate that distant learning anxiety has the potential to negatively impact distance learning satisfaction. As students’ anxiety levels rise, their satisfaction with the experience of delivering lectures through remote learning will decrease. Distance education can induce greater levels of anxiety compared to traditional in-person learning, particularly when utilising online platforms. Moreover, there is a correlation between worry and student satisfaction (Ajmal et al., Citation2019; Bolliger & Halupa, Citation2012; Bollinger, Citation2017). Students feel anxious about the absence of direct interaction with classmates and lecturers. Technology is one of the factors that can affect student self-efficacy. Student self-efficacy towards technology is proven to have a relationship with student academic achievement. Students with high self-efficacy towards technology experience learning satisfaction compared to those with lower self-efficacy. Students with higher levels of computer anxiety will feel unlucky because these feelings of anxiety will affect satisfaction with learning and delivery of material (Artino, Citation2008; Mcghee, Citation2010; Saadé & Kira, Citation2007).

The transition from traditional face-to-face learning to remote distance learning is a direct consequence of the COVID-19 epidemic. Distance learning is the optimal solution for organising educational activities. Students would inevitably be adversely affected by any abrupt alterations. In the past, students engaged in direct interaction with their peers and professors. Distance learning precludes direct interaction between students and their peers and instructors. The absence of face-to-face communication would inevitably lead to a feeling of seclusion among pupils.

Feelings of isolation may occur as a result of decreased social connection with college classmates, which can impact motivation and collaboration during lectures. This emotion leads to a reduction in students’ self-assurance when it comes to accomplishing each assignment assigned by the instructor. Students engaged in distance learning may encounter elevated levels of anxiety. Student academic performance might be impacted by anxiety (Ajmal et al., Citation2019; Bandura, Citation1977; Bollinger, Citation2017; DeVaney, Citation2010).

Lockdown policies and social distancing have changed face-to-face learning to distance learning. The sudden change has put mental pressure on students. The more significant the mental pressure felt, the lower the students’ satisfaction during the implementation of distance learning. Distance learning in taxation classes during the COVID-19 pandemic affects students’ distance learning satisfaction. Any abrupt alterations will unquestionably result in an adverse effect on students. In the past, students directly interacted with their peers and instructors.

Distance learning has given rise to several problems apart from isolation due to limited face-to-face interactions and lack of digital literacy (Owens et al., Citation2009). Another problem that may arise is the time difference, poor internet quality, and limited staff knowledge about the use of technology, which can also hinder synchronous learning implementation. Therefore, although technological sophistication can reduce feelings of isolation, students still feel that many other obstacles can trigger the emergence of anxiety. This feeling of anxiety affects distance learning satisfaction.

The test results indicate that there is a moderate negative impact of distance learning anxiety on distance learning satisfaction across all grade levels. This finding indicates a negative correlation between the level of anxiety experienced by students and their satisfaction in taxation classes during the COVID-19 epidemic. This association can be established by taking into account the student’s academic performance. First-year students are prone to experiencing heightened anxiety levels in online courses. They must exert greater effort when transitioning into a novel educational setting. The anxiety surrounding remote learning intensifies this condition (Ray et al., Citation2023). Due to the COVID-19 epidemic, first-year students are required to engage in remote learning at the start of their classes. Undoubtedly, this circumstance will have an impact on their scholastic performance while delivering lectures through remote learning within the COVID-19 pandemic.

However, more experienced students feel free of the pressure to feel satisfaction in distance learning. The more senior the student, the more experience students have in preparing for lectures. Thus, students become more capable of preparing for lectures using distance learning. In addition, the more capable students feel ready to conduct class using distance learning, the more satisfied they will be with implementing it during the COVID-19 pandemic. The higher the students’ grades, the more experience they have, including the experience of participating in distance learning. This condition also relates to students’ classroom readiness using distance learning during the COVID-19 pandemic.

There is a strong relationship between students’ readiness and the level of perceived anxiety. Senior students have more experience in time management, critical thinking skills, and collaborating with others. More senior students feel more confident and able to take distance learning, making them less anxious and frustrated (Abdous, Citation2019). Younger students (first-year students) will feel more anxious than older students (seniors). However, the other previous study explains that students who are in the second year of university have higher adverse effects, levels of anxiety, and depression than first-year students. It happens because of the heavier burden of the curriculum and the thought that isolation and online learning will only hinder the progress of their studies (Cao et al., Citation2020). This condition is related to the experience they gain in learning. Therefore, students’ readiness is negatively related to anxiety levels. The level of anxiety hurts satisfaction during distance learning (Holder, Citation2007; Kanuka & Jugdev, Citation2006; Parkes et al., Citation2014).

5. Conclusion

The purpose of this research is to establish a causal connection between anxiety levels and student satisfaction with distance learning in the field of taxation amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. The aim is to illustrate that worry can, directly and indirectly, influence student happiness throughout their academic journey. Before and throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, the educational experience did not necessarily guarantee the satisfaction of students involved in remote learning. The sentiment of final-year and intermediate or new students towards remote learning is the same. Students encounter comparable intrinsic characteristics, such as motivation, IQ, and learning objectives, as well as extrinsic factors, like limitations on teacher proficiency, learning materials, teaching resources, learning environment, and learning opportunities, all impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic.

The research on the impact of Distance Learning Anxiety (DLA) on Distance Learning Satisfaction (DLS), with experience in learning as a moderator, has important practical implications for educational practice and policy. Firstly, comprehending the moderating function of the learning experience illuminates the significance of customizing interventions and support mechanisms to tackle DLA among students. Teachers can provide specific interventions to assist students with different degrees of learning expertise, such as supplying extra resources or advice to inexperienced learners while providing more sophisticated ways or opportunities for experienced learners to address DLA. Moreover, acknowledging the crucial influence of the learning experience in mediating the connection between DLA and DLS emphasizes the necessity of continuous professional growth for educators to enhance their comprehension and handling of the varied requirements of students. The policy implications involve lobbying for incorporating techniques that promote the inclusion of learners with varied backgrounds and experiences into educational policies and practices. Furthermore, by promoting inclusive learning environments that prioritize mental health and well-being, regardless of students’ previous learning experiences, we can create a more supportive and conducive learning environment for all students. It, in turn, will enhance overall satisfaction and success in distance learning settings.

Additional investigation could be enhanced by doing a longitudinal study that monitors the changing correlation between DLA, DLS, and learning experience over an extended period. It would provide valuable insights into their enduring effects. An integrated methodology that combines quantitative surveys with qualitative interviews or focus groups has the potential to yield a full comprehension of students’ opinions and experiences. Conducting comparative analyses among different demographic groups would provide insights into the differences in the effectiveness of interventions. Additionally, intervention studies might assess specific techniques to reduce DLA (difficulties in learning) and boost DLS (learning success), considering the role of the learning experience. In addition, cross-cultural research can investigate the cultural elements that influence these dynamics, providing valuable insights for culturally sensitive solutions. By exploring these channels, future studies can enhance comprehension and guide the creation of impactful measures to promote student contentment and achievement in remote learning environments.

This study has several limitations. The grade can describe the learning experience but can only be part of the whole. The grade cannot yet describe students’ learning experiences in the form of extracurricular activities, self-development, and individual factors, so each student’s learning experience will be different. Therefore, further research can use other variables as moderating variables, for example, learning motivation, learning skills, social support, learning quality, and technology readiness. This study was conducted at the Taxation Study Program of Universitas Brawijaya, which is the sole university in Indonesia that provides a tax curriculum for undergraduate students. Hence, the conclusions drawn from this study cannot be extrapolated to different scenarios. Additional investigation could entail comparing the degree of anxiety and student contentment in alternative academic programs, either within the same educational institution or at a distinct university.

Authors’ contributions

The author actively participates in the conceptualization and design, analysis and interpretation of data, the drafting of the paper, the critical revision of its intellectual content, and the final approval of the version to be published. The author accepts responsibility for all parts of the work.

Ethics statement

The research involving human participants followed the ethical standards of the commitee for research ethics and with comparable ethical standards.

Disclosure statement

The author declares no financial, professional, or personal competition interest with other parties.

Data availability statement

The dataset generated during and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on request.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Nurlita Sukma Alfandia

Nurlita Sukma Alfandia is a lecturer at the Taxation Study Program, Brawijaya University, Indonesia. Current research focuses include education, accounting, finance, and taxation. This is her first research that related education and taxation.

References

- Abdolrezapour, P., Ganjeh, S. J., & Ghanbari, N. (2023). Self-efficacy and resilience as predictors of students’ academic motivation in online education. PLoS One, 18, e0285984. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0285984

- Abdous, M. (2019). Influence of satisfaction and preparedness on online students’ feelings of anxiety. The Internet and Higher Education, 41, 34–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2019.01.001

- Abdous, M., & Yen, C. J. (2010). A predictive study of learner satisfaction and outcomes in face-to-face, satellite broadcast, and live video-streaming learning environments. The Internet and Higher Education, 13(4), 248–257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2010.04.005

- Ackerman, I. N., & Busija, L. (2012). Access to self-management education, conservative treatment and surgery for arthritis according to socioeconomic status. Best Practice & Research. Clinical Rheumatology, 26(5), 561–583. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.BERH.2012.08.002

- Aditya, R. R., & Ulya, Z. (2021). Impact and vulnerability of distance learning on the mental health conditions of students. Journal of Psychiatry Psychology and Behavioral Research, 1(1), 8–11. https://jppbr.ub.ac.id/index.php/jppbr/article/view/24/25 https://doi.org/10.21776/ub.jppbr.2021.001.01.3

- Ajmal, M., Ahmad, S., & Scholar, P. (2019). Exploration of anxiety factors among students of distance learning: A case study of Allama Iqbal Open University. Bulletin of Education and Research, 41(2), 67–78.

- Artino, A. R. (2008). Motivational beliefs and perceptions of instructional quality: Predicting satisfaction with online training. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 24(3), 260–270. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2729.2007.00258.x

- Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. American Political Science Review, 71(1), 67–85. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055400259303

- Barlow, D. H. (2002). Anxiety and its disorder: The nature and treatment of anxiety and panic (2nd ed). The Guilford Press.

- Bolliger, D. U., & Halupa, C. (2012). Student perceptions of satisfaction and anxiety in an online doctoral program. Distance Education, 33(1), 81–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2012.667961

- Bollinger, A. S. (2017). Foreign language anxiety in traditional and distance learning foreign language classrooms.

- Cao, W., Fang, Z., Hou, G., Han, M., Xu, X., Dong, J., & Zheng, J. (2020). The psychological impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on college students in China. Psychiatry Research, 287, 112934. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112934

- Cidral, W. A., Oliveira, T., Di Felice, M., & Aparicio, M. (2018). E-learning success determinants: Brazilian empirical study. Computers & Education, 122, 273–290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2017.12.001

- Cleveland-Innes, M., & Campbell, P. (2012). Emotional presence learning online environment. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 13(4), 269–292. http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/1234 https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v13i4.1234

- D’Mello, S., & Graesser, A. (2012). Dynamics of affective states during complex learning. Learning and Instruction, 22(2), 145–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2011.10.001

- DeVaney, T. A. (2010). Anxiety and attitude of graduate students in On-Campus vs. online statistics courses. Journal of Statistics Education, 18(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/10691898.2010.11889472

- Fancourt, D., Steptoe, A., & Bu, F. (2021). Trajectories of anxiety and depressive symptoms during enforced isolation due to COVID-19 in England: A longitudinal observational study. The Lancet Psychiatry, 8(2), 141–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30482-X

- Franco, Z. I., Go, J. A., & Iniego, J. (2023). Stress experiences and coping mechanisms of science and mathematics students on online learning amidst COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Research Studies in Education, 12(3), 53–66. https://doi.org/10.5861/ijrse.2023.1004

- Gabrovec, B., Selak, Š., Crnkovič, N., Cesar, K., & Šorgo, A. (2022). Perceived satisfaction with online study during COVID-19 lockdown correlates positively with resilience and negatively with anxiety, depression, and stress among Slovenian postsecondary students. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(12), 7024. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19127024

- Ghaderizefreh, S., & Hoover, M. L. (2018). Student satisfaction with online learning in a blended course.

- Ghozali, I. (2016). Desain Penelitian Kuantitatif dan Kualitatif.

- Gorriz, J. M., Zhang, Y., Gabrovec, B., Selak, Š., Crnkovič, N., Cesar, K., & Šorgo, A. (2022). Perceived satisfaction with online study during COVID-19 lockdown correlates positively with resilience and negatively with anxiety, depression, and stress among Slovenian postsecondary students. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(12), 7024. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19127024

- Grayson, J. P. (2004). The relationship between grades and academic program satisfaction over four years of study. Canadian Journal of Higher Education, 34(2), 1–34. https://doi.org/10.47678/cjhe.v34i2.183455

- Grigorkevich, A., Savelyeva, E., Gaifullina, N., & Kolomoets, E. (2022). Rigid class scheduling and its value for online learning in higher education. Education and Information Technologies, 27(9), 12567–12584. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-022-11131-3

- Hachey, A. C., Wladis, C. W., & Conway, K. M. (2014). Do prior online course outcomes provide more information than G.P.A. alone in predicting subsequent online course grades and retention? An observational study at an urban community college. Computers & Education, 72, 59–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2013.10.012

- Hilliard, J., Kear, K., Donelan, H., & Heaney, C. (2020). The impact of emotions on student participation in an assessed, online, collaborative activity. In EDEN Conference Proceedings (1, pp. 143–152). https://doi.org/10.38069/edenconf-2020-ac0012

- Holder, B. (2007). An investigation of hope, academics, environment, and motivation as predictors of persistence in higher education online programs. The Internet and Higher Education, 10(4), 245–260. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2007.08.002

- Hu, N., & Chen, M. (2022). Improving ESP writing class learning outcomes among medical university undergraduates: How do emotions impact? Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 909590. https://doi.org/10.3389/FPSYG.2022.909590/BIBTEX

- Jumaat, N. F., & Termidi, N. S. A. (2022). Assessments of student’s emotions and their relevance in online learning. Asean Journal of Engineering Education, 6(2), 6–10. https://doi.org/10.11113/ajee2022.6n2.102

- Kanuka, H., & Jugdev, K. (2006). Open learning: The journal of open, distance and e-learning distance education MBA students: An investigation into the use of an orientation course to address academic and social integration issues. Open Learning, 21(2), 153–166. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680510600715578

- Khamidzhanovna, K. V., & Rakhmatullaevna, A. N. (2022). The role and place of distance learning in education. International Journal of Early Childhood Special Education, 14(5), 1. https://doi.org/10.9756/INTJECSE/V1415.1110

- Khan, R. M. I., & Ali, A. (2023). Review of Morel and Spector’s (2022) book “Foundations of Educational Technology: Integrative Approaches and Interdisciplinary Perspectives” Taylor & Francis. International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning (iJET), 18(06), 228–233. https://doi.org/10.3991/ijet.v18i06.36989

- Kim, J.-W., & Baek, S.-G. (2020). The longitudinal relationships between undergraduate students’ competencies and educational satisfaction according to academic disciplines. Asia Pacific Education Review, 21(4), 573–587. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12564-020-09646-w

- Kim, S. H., & Park, S. (2021). Influence of learning flow and distance e-learning satisfaction on learning outcomes and the moderated mediation effect of social-evaluative anxiety in nursing college students during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study. Nurse Education in Practice, 56(August), 103197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2021.103197

- Kolug, J. Y., & Kankam, G. (2023). Constructs of E-learning towards customer satisfaction among distance learning students in Ghana. Journal of Education and Learning Technology, 12–25. https://doi.org/10.38159/jelt.2023412

- Lai, C. S., Au, K. M., & Low, C. S. (2021). Beyond conventional classroom learning: Linking emotions and self-efficacy to academic achievement and satisfaction with online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Education and e-Learning Research, 8(4), 367–374. https://doi.org/10.20448/journal.509.2021.84.367.374

- Lavoue, E., Molinari, G., & Trannois, M. (2017 emotional data collection using self-reporting tools in distance learning courses [Paper presentation]. In IEEE 17th International Conference on Advanced Learning Technologies, ICALT 2017 (pp. 377–378). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICALT.2017.94

- Levpušček, M. P., & Podlesek, A. (2019). Links between academic motivation, psychological need satisfaction in education, and university students’ satisfaction with their study. Psihologijske Teme, 28(3), 567–587. https://doi.org/10.31820/pt.28.3.6

- Lyubetsky, N., Bendersky, N., Verina, T., Demyanova, L., & Arkhipova, D. (2021). IMPACT of distance learning on student mental health in the COVID-19 pandemic. E3S Web of Conferences, 273, 10036. https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202127310036

- Maidment, J., & Crisp, B. R. (2011). Social work education the impact of emotions on practicum learning the impact of emotions on practicum learning. Social Work Education, 30(04), 408–421. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2010.501859

- Manzar, M. D., Alghadir, A. H., Khan, M., Salahuddin, M., Albougami, A., Maniago, J. D., Vasquez, B. A., Pandi-Perumal, S. R., & Bahammam, A. S. (2021). Anxiety symptoms are associated with higher psychological stress, poor sleep, and inadequate sleep hygiene in collegiate young adults-a cross-sectional study. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 677136. https://doi.org/10.3389/FPSYT.2021.677136

- Martin, R. T., Lecrom, C. W., & Lassiter, J. W. (2017). Hearts on our sleeves: Emotions experienced by service-learning faculty. International Journal of Research on Service-Learning and Community Engagement, 5(1), 41–56. https://doi.org/10.37333/001c.29754

- Mazlan, N., & Sumarjan, N. (2022). Stress, anxiety and satisfaction in online learning: The moderating role of instructor support. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 12(11), 669–683. https://doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v12-i11/15611

- Mcghee, R. M. H. (2010). Asynchronour interaction, online technologies self-efficacy and self-regulated learning as predictors of academic achievement in an online classs.

- Nasri, N. M., Husnin, H., Mahmud, S. N. D., & Halim, L. (2020). Mitigating the COVID-19 pandemic: A snapshot from Malaysia into the coping strategies for pre-service teachers’ education. Journal of Education for Teaching, 46(4), 546–553. https://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2020.1802582

- Oliveira, A. A. d., Silva, L. A. B. d., Nelson Filho, P., Puccinelli, C. M., Silva, C. M. P. C., & Segato, R. A. B. (2022). The psychological impact of social distancing related to the covid-19 pandemic on undergraduate and graduate students in Brazil. Brazilian Journal of Oral Sciences, 21, e226698–e226698. https://doi.org/10.20396/bjos.v21i00.8666698

- Owens, J., Hardcastle, L., & Richardson, B. (2009). Learning from a distance: The experience of remote students. Journal of Distance Education, 23(3), 53–74.

- Parkes, M., Stein, S., & Reading, C. (2014). Student preparedness for university e-learning environments. The Internet and Higher Education, 25(Suplement C), 1–10., https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2014.10.002

- Pelucio, L., Simões, P., Dourado, M. C. N., Quagliato, L. A., & Nardi, A. E. (2022). Depression and anxiety among online learning students during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional survey in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. BMC Psychology, 10(1), 192. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-022-00897-3

- Ramadan, M., Tappis, H., Villar, M., World, U., Group, B., & Brieger, W. (2021). Access to primary healthcare services in conflict-affected fragile states: A subnational descriptive analysis of educational and wealth disparities in Cameroon, Democratic Republic of Congo, Mali, and Nigeria. International Journal for Equity in Health, 20(1), 253. https://doi.org/10.21203/RS.3.RS-735923/V1

- Ray, E. C., Perko, A., Oehme, K., Arpan, L., Clark, J., & Bradley, L. (2023). Freshmen anxiety and COVID-19: Practical implications from an online intervention for supporting students affected by health inequities. Journal of American College Health: J ACH, 71(7), 2234–2243. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2021.1965610

- Rybakova, A., Shcheglova, A., Bogatov, D., & Alieva, L. (2021). Using interactive technologies and distance learning in sustainable education. E3S Web of Conferences, 250, 07003. https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202125007003

- Saadé, R. G., & Kira, D. (2007). Mediating the impact of technology usage on perceived ease of use by anxiety. Computers & Education, 49(4), 1189–1204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2006.01.009

- Sadaf, A., Martin, F., & Ahlgrim-Delzell, L. (2019). Student perceptions of the impact of “quality matters” certified online courses on their learning and engagement. Online Learning, 23(4), 214–233. https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v23i4.2009

- Sadeghi, M. (2019). A shift from classroom to distance learning: Advantages and limitations. International Journal of Research in English Education, 4(1), 80–88. (https://doi.org/10.29252/ijree.4.1.80

- Samost-Williams, A. L., & Minehart, R. D. (2022). Focus on theory: Emotions and learning. In D. Nestel, G. Reedy, L. McKenna, & S. Gough (Eds.), Clinical education for the health professions. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-6106-7_36-1

- Sara, J. A. (2022). Anxiety analysis of students taking distance learning in mathematics learning in junior high schools. Journal of Mathematics and Mathematics Education, 12(2), 96–104. https://doi.org/10.20961/jmme.v12i2.64438

- Sharma, D., & Bhaskar, S. (2020). Addressing the Covid-19 burden on medical education and training: The role of telemedicine and tele-education during and beyond the pandemic. Frontiers in Public Health, 8, 589669. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2020.589669

- Siming, L., Gao, J., Xu, D., & Shafi, K. (2015). Factors leading to student’s satisfaction in the higher learning institutions. Journal of Educational and Practice, 6(31), 114–118. www.iiste.org

- Skiba, R. J., Poloni-Staudinger, L., Gallini, S., Simmons, A. B., & Feggins-Azziz, R. (2006). Disparate access: The disproportionality of African American students with disabilities across educational environments. Exceptional Children, 72(4), 411–424. https://doi.org/10.1177/001440290607200402

- Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., Williams, J. W., & Löwe, B. (2006). A brief measure for assessing Generalized Anxiety Disorder: The GAD-7. Archives of Internal Medicine, 166(10), 1092–1097. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092

- Stanley, L. R., Swaim, R. C., Keawe’aimoku Kaholokula, J., Kelly, K. J., Belcourt, A., Allen, J., & Sci, P. (2017). The imperative for research to promote health equity in indigenous communities. Prevention Science, 21(S1), 13–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-017-0850-9

- Szcześniak, D., Gładka, A., Misiak, B., Cyran, A., & Rymaszewska, J. (2019). The SARS-CoV-2 and mental health: From biological mechanisms to social consequences. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry, 104, 110046. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnpbp.2020.110046

- Talib, M. A., Bettayeb, A. M., & Omer, R. I. (2021). Analytical study on the impact of technology in higher education during the age of COVID-19: Systematic literature review. Education and Information Technologies, 26(6), 6719–6746. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-021-10507-1

- Teeroovengadum, V., Nunkoo, R., Gronroos, C., Kamalanabhan, T. J., & Seebaluck, A. K. (2019). Higher education service quality, student satisfaction and loyalty validating the HESQUAL scale and testing an improved structural model. Quality Assurance in Education, 27(4), 427–445. https://doi.org/10.1108/QAE-01-2019-0003

- Tlili, A., Essalmi, F., Jemni, M., Kinshuk, & Chen, N.-S. (2016). Role of personality in computer based learning. Computers in Human Behavior, 64, 805–813. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.07.043

- Torales, J., O'Higgins, M., Castaldelli-Maia, J. M., & Ventriglio, A. (2020). The outbreak of COVID-19 coronavirus and its impact on global mental health. The International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 66(4), 317–320. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764020915212

- Turan, Z., Kucuk, S., & Karabey, S. C. (2022). The university students’ self-regulated effort, flexibility and satisfaction in distance education. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 19(1), 35. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-022-00342-w

- UNESCO. (2020). Distance learning strategies in response to COVID-19 school closures. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000373305?posInSet=2&;queryId=N-8ea77989-29de-4ff3-997c-eaddc678be5b

- Vasil, M., Weiss, L., & Powell, B. (2018). Popular music pedagogies: An approach to teaching 21st-century Skills. Journal of Music Teacher Education, 28(3), 85–95., https://doi.org/10.1177/1057083718814454 https://doi.org/10.1177/1057083718814454

- Wang, Y. (2023). Education and Information Technologies. Education and Information Technologies, 28(10), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-023-11693-w

- Wäschle, K., Allgaier, A., Lachner, A., Fink, S., & Nückles, M. (2014). Procrastination and self-efficacy: Tracing vicious and virtuous circles in self-regulated learning. Learning and Instruction, 29, 103–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2013.09.005

- Weerasinghe, I. M. S., Lalitha, R., & Fernando, S. (2017). Students’ satisfaction in higher education literature review. American Journal of Educational Research, 5(5), 533–539. https://doi.org/10.12691/education-5-5-9

- Wittchen, H. (2001). Wittchen.Hoyer.2001. Prev.Epi.Risk, 62(11), 15–19.

- Wortha, F., Azevedo, R., Taub, M., & Narciss, S. (2019). Multiple negative emotions during learning with digital learning environments – evidence on their detrimental effect on learning from two methodological approaches. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 479184. https://doi.org/10.3389/FPSYG.2019.02678/BIBTEX

- Yang, S., Hsu, W. C., & Chen, H. C. (2016). Age and gender’s interactive effects on learning satisfaction among senior university students. Educational Gerontology, 42(12), 835–844. https://doi.org/10.1080/03601277.2016.1231514

- Yuce, A., Abubakar, A. M., & İlkan, M. (2019). Intelligent tutoring systems and learning performance. Online Information Review, 43(4), 600–616. https://doi.org/10.1108/OIR-11-2017-0340