?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

The study examined the influence of school heads' clinical supervision practices on teachers’ professional competency development in public secondary schools in Tanzania. It was a mixed-methods research approach that involved Tanzanian school heads and teachers. Survey data from 94 participants were quantitatively analysed, and narrative data from 28 informants were subject to content analysis. Based on narrative findings, clinical supervision was the factor in developing teachers’ professional competencies: searching for teaching and learning resources, understanding the subject matter, organizing lessons, conducting interactive teaching and learning, and evaluating students’ learning. The descriptive results showed pre-observation of the lesson plans (M = 1.79) ranked at strongly agreed responses. Pre-observation of schemes of work, classroom observation, supervisory feedback, teachers’ professional support, and post-observation had a range of (M = 1.86) and (M = 2.06) ranked at agreed responses. These findings detail that school heads’ clinical supervision practices positively influenced teachers’ professional competency development. Therefore, the present study contributes to the existing literature of clinical supervision that each clinical supervision technical aspect has the potential to enhance teachers’ teaching professional competencies development in the workplace. These findings exceptionally increase the need to strengthen the clinical supervision practices that centrally map teachers’ professional needs and development.

REVIEWING EDITOR:

1. Introduction

Professional teachers are competent in exercising teaching and learning activities (Tanjung, Citation2020). Indeed, stable teachers’ competencies are essential in ensuring that teaching and learning quality is appropriately implemented (Haris et al., Citation2018; Sergiovanni et al., Citation2013) for developing the human capital of any nation (Widodo et al., Citation2022). To this end, promoting teachers’ professional competency is vital (Anangisye, Citation2011; Goodson & Hargreaves, Citation2003) for teaching professional sustainability and raising a successful generation (Szabo & Jagodics, Citation2019). With it, Anangisye (Citation2011) writes: ‘Teachers’ sense of competency does not end with graduation ceremonies. Rather, the ceremonies mark the beginning of an endless process of professional advancement’ (p. 143). In other languages, developing teachers’ professional competencies as planning and implementing teaching and learning activities (Tanjung, Citation2020), is an ongoing process in teachers professional lives (Goodson & Hargreaves, Citation2003; Kaur, Citation2018; Keiler, Citation2018; Mgeni & Anangisye, Citation2017; Rostami et al., Citation2020).

Educational organisations, which are secondary schools in this study, promote teachers’ teaching professional competency feelings (Carr, Citation2000; Dilekçi & Limon, Citation2022; Liljenberg & Blossing, Citation2021; Neil & Morgan, Citation2005). It occurs through school heads and teachers’ supervisory interactions (Chen et al., Citation2022; García-Martínez & Tadeu, Citation2018; Hubbard, Citation2021; Rostami et al., Citation2020; Suarez & McGrath, Citation2022). For example, Suarez and McGrath (Citation2022) confirm that school principals play an essential role in promoting the development of teachers’ professional competencies. Since the school heads’ supervisory practices are essential in developing teachers’ professional competencies, it is crucial to study how school heads’ clinical supervision practices develop teachers’ teaching professional competencies. This case study aimed to examine the opinions of school heads and teachers on school heads’ clinical supervision practices in developing teachers’ professional competencies in Tanzania’s public secondary schools.

2. Literature review

Clinical supervision in education began at Harvard University School of Education in the 1960s (Grimmett, Citation1981; Gürsoy et al., Citation2016; Reavis, Citation1976). Its primary implementation is interactive with the school heads and teachers during the teaching and learning process (Okorji & Ogbo, Citation2013). Finding the weaknesses in the teaching and learning process and directly improving such deficiencies within school settings (Babo & Agustan, Citation2022). Olibie, Mozie, and Egboka (Citation2016) argue that clinical supervision is the ‘process of facilitating the professional growth of teachers, primarily by observing teachers’ instructional practices, giving teachers’ feedback about classroom interactions and helping the teacher make use of the feedback to make teaching more effective’ (p. 47). It could be argued that clinical supervision is a professional supervisory model for in-service teachers’ professional development at the workplace.

Empirically, it is universally accepted that clinical supervision guides school heads to diagnose teachers teaching competency and improve it (Ayeni, Citation2012; Bello & Olaer, Citation2020; Bojo & Mustapha, Citation2017; Enyonam & Mensah, Citation2020; Garman, Citation2020). Despite the importance of clinical supervision practices in school settings worldwide, little has been investigated regarding developing teachers’ professional competencies through clinical supervision practices in Tanzania.

The surveyed previous studies associated school heads’ competencies in clinical supervision practices and teachers’ competencies in international settings: Iran by Khaef and Karimnia (Citation2021), Philippines by Bello and Olaer (Citation2020), and Laguna et al (Citation2023), and Indonesia by Darmawati (Citation2021). From these studies, school heads were found to have supervisory skills in reinforcing pre-observation, classroom observation, supervisory feedback, and post-observation. A study by Khaef and Karimnia (Citation2021) discovered that school heads were competent in post-observation supervisory feedback for teachers. Laguna et al.(Citation2023) discovered that school heads’ clinical supervisory activities in the classrooms improve teachers’ competencies in constructing formative assessments and developing content knowledge of the subject matter.

Similarly, Darmawati (Citation2021) confirms that school heads’ supervisory competencies in pre-observation, classroom observation, and post-observation effectively improved teachers’ mastering of teaching and learning methods. Due to school heads’ skills and knowledge in clinical supervision, teachers developed the necessary teaching professional skills (Darmawati, Citation2021). Previous studies’ findings inspire the current study about the positive relationship between school heads’ competencies in reinforcing clinical supervision to teachers and thereby enhancing teaching professional competency development. However, such consensus on developing teaching professional competency due to clinical supervision practicum exists in international contexts, so conducting this study in Tanzania is of concern. To provide new direction relative to developing teaching professional competencies at the workplace.

In the clinical supervision literature, there are studies on the perceptions of educational leaders, managers, and educators of its relevance in education (Dreyer & Musundire, Citation2019; Reid & Soan, Citation2019). The study by Reid and Soan (Citation2019) in the United Kingdom found that educational leaders positively perceived clinical supervision because it made them grow professionally. Similarly, a study by Dreyer & Musundire (Citation2019) in South Africa revealed that school managers and educators had positive views on clinical supervision practices, which improved teachers’ work performance and quality teaching.

These findings from previous studies bridge the present study by providing evidence that clinical supervision practices develop professional competency among educational leaders and managers. Differently, the present study focuses on developing teachers’ professional competencies. This is a crucial contribution to the clinical supervision literature, as the findings would widen an understanding of the extent to which teachers have positive perceptions relative to professional growth from school heads’ clinical supervision practices in secondary schools.

Chinedu (Citation2021), Husain et al. (Citation2019), and Putra et al. (Citation2021) examined the contribution of clinical supervision on teachers’ work performance. Chinedu (Citation2021) in Nigeria and Husain et al. (Citation2019) in Malaysia discovered that school heads effectively supervised teachers through clinical supervision comprising pre-observation, classroom observation, and post-observation. In turn, teachers develop positive feelings regarding improving work performance. Husain et al. (Citation2019), for example, specify that due to school heads’ clinical supervision, teachers were found to have high work performance not limited to involving students in teaching and learning activities, increasing levels of students’ testing in classroom assignments, and examinations.

These findings suggest that school heads are essential to ensure teachers develop a sense of teaching professional accountability in effectively teaching students. Many efforts are required to discover the importance of clinical supervision in shaping teachers’ mindsets about professional competencies development within schools. Darling-Hammond and Richardson (Citation2009) argue that workplaces for teachers are opportunities for them to learn and reflect on new teaching practices that increase their professional knowledge.

There are studies on clinical supervision and teachers’ quality teaching and learning (Babo & Agustan, Citation2022; Maulidiansyah et al., Citation2023; Musa & Binti, Citation2020; Nkwasiibwe et al., Citation2023; Sule et al., Citation2020) across Indonesia, Uganda, Malaysia, and Nigeria. In these countries, school heads’ clinical supervision practices included pre-observation of teaching materials, observing teaching and learning in the classroom, and supervisory feedback. Babo and Agustan (Citation2022) in Indonesia, for example, claim that due to school heads’ clinical supervision practices, teachers’ readiness for quality teaching and learning in aspects such as preparation of teaching tools and reflecting learning and learning reflection significantly improved.

Similarly, Nkwasiibwe et al. (Citation2023) found a significant relationship between clinical supervision and teachers’ preparation for teaching in universal primary schools in Uganda. Maulidiansyah et al. (Citation2023) argues that school heads’ planning and implementing clinical supervision with school heads’ assistants, senior teachers, and deputy heads of curriculum helped teachers grow independently in preparing quality teaching and learning in schools. In countries such as Malaysia, Musa and Binti (Citation2020) found that school heads’ clinical supervision practices, which are not limited to direct classroom observation, and teachers’ professional support enhanced teaching and learning knowledge in teachers.

The same case has been discussed by Sule et al. (Citation2020) from Nigeria, that school heads’ clinical supervisory practices, such as classroom observation and post-observation, significantly influenced teachers’ professional efficacy development among teachers. The surveyed literature has been conducted in different contexts to confirm the influence of clinical supervision practices on teachers’ professional commitments in preparing quality learning. As quality teaching - learning preparation and practices are relatively influenced by teachers' competencies, in Tanzania, scant research studies have examined the contribution of school heads’ clinical supervision practices in developing teachers’ professional competencies. To reflect on the surveyed research studies, few studies were similar to this one in international contexts; what makes this study different is that it focuses on the opinions of school heads and teachers towards school heads’ clinical supervision practices in developing teaching professional competencies in Tanzania.

3. Clinical supervision in the Tanzania context

The United Republic of Tanzania emphasises that school heads employ clinical supervision strategies in supervising teachers’ teaching professional activities (United Republic of Tanzania, Citation2018a). Primary enabling teachers to grow professionally (United Republic of Tanzania, Citation2017). In the course of action, school heads and teachers employ clinical supervision strategies as directed in the ‘School Improvement Toolkit for Tanzanian Heads of Schools (SITHS) of 2013’ (United Republic of Tanzania, Citation2013): (1) before teaching and learning, school heads and teachers have to discuss teaching and learning activities as prepared in schemes of work and lessons plans; (2) regularly planing and undertaking actual classroom supervision; (3) ensuring teachers receive teaching professionally technical supported; (4) ensuring an ongoing teaching and learning supervision for teachers to improve quality of teaching and learning. It could be argued that school heads supervising teachers through clinical supervision is crucial for teachers’ professional growth in the workplace. This was the main focus of the present study.

However, its contribution to developing teachers’ competencies in the workplace is generally missing, as few empirical studies have investigated clinical supervision practices in line with teachers’ work performance across Regions in Tanzania, such as Mwanza, Kagera, Lindi, and Kilimanjaro (Chiwamba et al., Citation2022; Mwesiga & Okendo, Citation2018; Ngole & Mkulu, Citation2021). According to Chiwamba et al. (Citation2022), school heads’ oversight of classroom observation caused some teachers to lag in completing the lessons’ topics.

Similarly, Ngole and Mkulu (Citation2021) discovered that school heads were ineffective in supervising teachers’ schemes of work, among other professional documents and classroom teaching and learning activities. On the contrary, Mwesiga and Okendo (Citation2018) found that school heads effectively undertook supervisory activities such as reviewing teachers’ schemes of work lesson plans and observing actual teaching and learning activities. These supervisory activities improved teachers’ work performance by involving students in learning activities. School heads’ clinical supervision practices in developing teachers’ professional competencies are somewhat unclear as there is a lack of research studies that specify how teachers’ professional competencies advance from clinical supervisory practicum.

The present study, however, acknowledges the study by Mwakajitu and Lekule (Citation2022) on the contribution of instructional supervision to teachers’ professional development. In its discovery, teachers developed professional capacities for efficiently preparing schemes of work and lesson plans. These insights are insufficient to argue for constantly developing teaching competencies through clinical supervision practices in secondary schools in Tanzania. Therefore, the study aimed to examine the opinions of school heads and teachers on school heads’ clinical supervision practices in developing teachers’ professional competencies in Tanzania’s public secondary schools.

4. Theoretical framework

The theoretical stance of this study is built on the view that clinical supervision is the supervisory approach used to develop teaching professional competencies (Cogan, Citation1973; Goldhammer, Citation1969). Its practices comprise five chronological orders: pre-observation, classroom observation, supervisory feedback, professional support, and post-observation. Pre-observation allows school heads to review teachers’ preparatory teaching and learning materials before actual teaching and learning practices. Classroom observation guides school heads in observing teaching and learning activities in a natural classroom. Teachers’ teaching and learning behaviours, such as engaging students in learning activities, are recorded for further discussion and professional support.

Supervisory feedback deals with disclosing teaching and learning weaknesses and strengths to teachers. School heads and teachers reflect on important areas requiring professional development through such practices. Under professional support practices, school heads must be planned and organised school-based learning for teachers. Post-observation practice guides school heads in re-observing classroom teaching and learning and planning future clinical supervision.

Regarding the classification of teachers’ professional competencies: Professional competencies of teachers include experts in subject matter, teaching methodological and didactical perspectives (Beijaard et al., Citation2004); teachers’ language skills, disciplinary knowledge, and knowledge of practicing teaching in the classroom (Pennington & Richards, Citation2016); teachers’ in the subject of teaching, mastering the preparation of professional documents as lesson plans and schemes of work, and evaluating teaching and learning practices (Cheng, Citation2021). Education International & UNESCO, Citation2019) in the Global Framework of Professional Teaching Standards (GFPTS) 2019 highlight multiple dimensions of teaching professional competencies. These are subject content, setting teaching and learning objectives, facilitating interactive teaching and learning, and evaluating student outcomes.

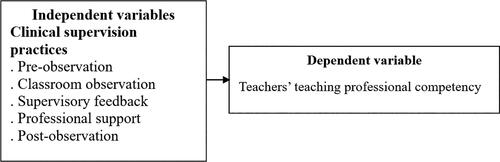

The present study treated multiple dimensions of teaching professional competencies as teachers’ professional competency development. Ballová Mikušková et al. (Citation2024) sum up teachers’ multiple competencies by the term ‘professional competencies which enable a teacher to perform skilled activities on a professional basis’ (Ballová Mikušková et al., Citation2024, p. 1). Therefore, the study’s independent variable was clinical supervision practices (pre-observation, classroom observation, supervisory feedback, professional support, and post-observation), and the dependent variable was teachers’ teaching professional competency. Assuming that there was a relationship between school heads’ clinical supervision practices and teachers’ teaching professional competency. shows the relationships of variables.

Figure 1. Conceptual framework for clinical supervision.

Source: Literature (Cogan, Citation1973; Education International & UNESCO, Citation2019; Goldhammer, Citation1969).

5. Methods and materials

5.1. Research approach and design

The study employed a mixed concurrent research methods approach (Creswell, Citation2014; Pajo, Citation2018). It collected numerical and narrative data from school heads and teachers within their schools to get teachers’ feelings on developing professional teaching competency. The study was guided by complementarity to clarify if school heads’ and teachers’ perceptions differed significantly from clinical supervision practices. Triangulation merged informants’ views and respondents’ attitudes as derived from stages of clinical supervision practices. Regarding expansion, it served as a means of enlarging the study by presenting descriptive and narrative findings side by side. Initiation is the last reason that helped to unfold the finding contradictions that appeared in descriptive findings against narrative results to make a sturdy stand. The study employed a multiple-case study design (Yin, Citation2014). In addition, the design puts forward strategies for deeply investigating a phenomenon from the context (Marshall & Rossman, Citation2016; Starman, Citation2013). Based on this ground, perceptions of the school heads and teachers on school heads’ clinical supervision were gathered in line with teachers’ teaching competency development.

5.2. Location of the study

This study was conducted in one of the regions in Tanzania for the academic year (2020–2021). It is located in the Southern Highlands, below the equator between latitudes 8° 40' and 10° 32' and longitudes 33° 47' and 35° 45' East of Greenwich; its land area is 21,299 Square Kilometres, and water area is 3,695 Square Kilometres. The Region was chosen for this study because it has good records of students’ academic achievement (United Republic of Tanzania, Citation2018b). However, the government survey on secondary education performance delivery report shows that 43% of education stakeholders were unsatisfied with teaching and learning (United Republic of Tanzania, Citation2016). Therefore, it was essential to understand school heads and teachers’ perceptions of the influence of clinical supervision practices under school heads on the development of teachers’ teaching professional competency feelings, as teachers’ competencies were directly linked with students’ teaching and learning processes.

5.3. Sample size and sampling techniques

National Database for Education Statistics (2020) (United Republic of Tanzania, Citation2020) and Yamane’s sample size determination formula at 0.1% sampling error (Yamane, Citation1967) were used in selecting 94 teachers as respondents for quantitative aspects and 28 teachers as informants for qualitative elements. Quantitative respondents were subjected to a simple probability random sampling technique, the fishbowl draw method (Singh, Citation2006), and qualitative informants were subject to purposive sampling techniques. With this reputation, the purposive technique was employed to select four school heads and eight experienced teachers. The purposive criteria technique was used in selecting sixteen teachers. The sixteen teachers were selected based on inclusion criteria such as gender (Shapira-Lischshinsky, Citation2009) and working experience (Chinedu, Citation2021); subsequently, only male and female teachers whose working experiences ranged from 5 to 10 years were included in the study.

5.4. Data collection instrument and procedures

The study used a self -developed questionnaire titled ‘School Heads’ Clinical Supervision Practices for Development of Teacher Profession Identity (SHCSDoTPI)’. The questionnaires comprised five Likert Scales, ranging from 1 = Strongly agree to 5 strongly disagree. The questionnaires measured the extent of teachers’ perceptions of the contribution of clinical supervision practices to developing teachers’ professional competencies. There were 19 research items. (1) Pre-observation of schemes of work (3 items) aimed to assess teachers’ perceptions on setting teaching and learning objectives, knowledge of the subject matters, and designing participatory teaching and learning. (2) Pre-observation of lesson plans (3 items) assessed teachers’ perception of setting objectives, organising the subject matter, and facilitating participatory teaching and learning. (3) Classroom observations (3 items) aimed to assess teachers’ perception of managing students, facilitating participatory teaching and learning, and evaluating classroom teaching and learning.(4) Supervisory feedback (3 items) assessed teachers’ perceptions relative to competencies in participatory teaching and learning, managing students in classrooms, and evaluating classroom teaching and learning. (5) Professional support (4 items) aimed to assess teachers’ perceptions on managing students’ learning in the classroom, facilitating participatory teaching and learning, evaluating classroom teaching and learning, and assessing students’ teaching and learning achievement skills. (6) post-observation (3 items) assessed teachers’ perceptions on managing students in the classroom, facilitating participatory teaching and learning, and evaluating classroom teaching and learning practices.

The principal investigator administered the questionnaires himself to 94 teachers. To avoid incomplete questionnaires or questionnaires being filled in by third-party individuals and low-rate returns of the questionnaires. In return, there was a high return rate for the completed distributed questionnaires. The qualitative data, on the other hand, were obtained through a semi-structured interview protocol and Focused Group Discussions (FGDs). Qualitative data were collected through in-depth interview sessions with school heads and experienced teachers at each school.

One interview session of approximately 60 to 90 minutes was carried out. Teachers also participated in FGDs, whereas, in each school, four teachers were involved in FGDs within the school settings. The principal investigator was the facilitator of FGDs and agreed with the participants to use a maximum of 90 minutes for discussion to allow each participant to contribute to the subject matter (school heads’ clinical supervision practices and teachers’ professional competencies). The allocated time was standard as suggested: ‘One session for FGD should last no more than 90 to 120 minutes’ (Marczyk et al., Citation2015, p. 155). The study tape-recorded the narrative data, and after individual interviews and FGDs, the tape-recorded narrative data were immediately transferred to an audio storage device for the safety of the data.

5.5. Variable measurements

Variables of the study were subjected to five-point Likert scales ranging from 1 ‘strongly agree’ to 5 ‘strongly disagree’ (Singh, Citation2006) whereby:

Therefore, 1–1.8 = strongly agree, 1.9–2.6 = agree, 2.7–3.4 = neutral, 3.5–4.2 = disagree, 4.3–5.0 = strongly disagree. Mean scores were used to define centrality and the endpoint of analysis per variable. In this case, the mean scores of 1–2.6 were considered items accepted and highly contributed to teachers’ professional competency development. Variables with 2.7–3.4 mean scores were considered accepted and slightly contributed to teachers’ professional competency development. The mean scores of 3.5–5.0 were unacceptable and did not contribute to teachers’ professional competency development. A standard Deviation (SD) of ± 2 low was used to determine how the teachers’ responses to clinical supervision practices and professional competency development varied. Qualitative variables were measured by informants’ positive or negative attitudes: below ± 49 percentages yield negative attitudes, and ±50 above percentages are positive attitudes toward school heads’ clinical supervision practices aligned with the developed professional teaching competencies. Therefore, decisions on the results followed the majority overall counts and percentages in each sub-theme.

5.6. Validity and reliability

Content validity of the instruments crafted from the literature requires an expert judgment approach, and those judges must be specialists in the selected field of study (Mohajan, Citation2017; Taherdoost, Citation2016). To ensure the content validity of the developed tools, they were shared with two experts in School supervision and Professionalism in the teaching profession at the University of Dodoma. It was found that some terminologies (pre-observation conferences, analysis and interpretation, and post-observation conferences) would be new to teachers. It, therefore, was replaced with words that were more familiar to the context. Pre-observation was replaced with observation of teachers’ professional documents, analysis and interpretation were replaced with teaching and learning supervision feedback, and post-observation was replaced with teaching and learning supervisory follow-up.

The reliability of the instrument’s internal consistency was observed accordingly (Segal & Coolidge, Citation2018; Smith & Smith, Citation2018). The internal consistency results are presented as Cronbach’s coefficient (α) value, .90, considered excellent; a value above .80 is considered good, and a value of .70 is regarded as acceptable (Segal & Coolidge, Citation2018). Sürücü and Maslakçı (Citation2020) classify Cronbach’s Alpha Coefficient ().

Table 1. Classification of Cronbach’s alpha coefficient.

Literature (e.g. Mohajan, Citation2017; Segal & Coolidge, Citation2018; Sürücü & Maslakçı, Citation2020) has suggested that a value of 0.7 to 0.8 Cronbach’s Alpha is acceptable and satisfactory. shows the Cronbach’s Alpha results of research instruments.

Table 2. Cronbach’s alpha results.

The study was guided by internal reliability and a 10% sample size for pre-testing the instruments. The piloting instruments test from 10 participants produced an overall Cronbach’s Alpha of 0.922. The results were above the suggested (α) value, .70 to .80. These findings suggest that the research instruments were satisfactorily developed and could examine teachers’ opinions on school heads’ clinical supervision practices in developing teachers’ professional competences. However, pre-testing each category of clinical supervision technical aspect produced diverse results. For example, school heads’ post-observation supervision had a value of Cronbach’s Alpha (0.537). Despite this, the research items were retained, following that a ‘scale that measures two components of the construct will have lower (α) than another scale that measures one core concept’ (Segal & Coolidge, Citation2018, p. 3). Bajpai and Bajpai (Citation2014) support the claim that ‘the items should be hanging together as a set and be capable of independently measuring the same concept’ (p. 114).

Therefore, the study argues that three items in post-observation were found to have weak internal consistency of the scale within the instruments due to the few participants piloting the instruments. Segal and Coolidge (Citation2018) argue that when participants are above two hundred, Cronbach’s Alpha results are usually high, 0.80 to 0.90. When a hundred or a few participants participate in the study, Cronbach’s Alpha results tend to be low. The findings in support the scholarly insights as the value of Cronbach’s Alpha changed from (0.537) in the pre-testing of the instruments to (0.713) in the actual study. Generally, there was high reliability between 0.798 and 0.895 in sub-scales: pre-observation of schemes of work, pre-observation of lesson plans, supervisory feedback, and professional support. Only the sub-scale of post-observation had a weak reliability of 0.537.

5.7. Absence of common method bias

Harman’s single-factor test tested the absence of Common Method Bias (Fuller et al., Citation2016; Kock, Citation2017; Kock et al., Citation2021; Tehseen et al., Citation2017). Kock et al. write: ‘Common method bias can occur when both the independent and dependent variables are measured within one survey using the same response techniques’ (2021, p. 3). As the present study collected data from a single source, namely, secondary school teachers from one Region in Tanzania, using five-point Likert scales in all research items, it was necessary to ensure data were free from the standard method bias. Tehseen et al. (Citation2017) argue that common method bias may significantly influence the study findings. The data produced the single factor result of 41.969% of the total variation, which is below 50% (Kock et al., Citation2021), and therefore, the data used in this study were considered to be free from common method bias.

5.8. Data analysis

5.8.1. Qualitative analysis

Content analysis helps to analyses qualitative data (Elo & Kyngäs, Citation2008; Gheyle & Jacobs, Citation2017). Elo and Kyngäs (Citation2008) write: ‘Content analysis is a method that may be used with either inductive or deductive way’ (2008, p. 107). It was worth employing a deductive content analysis approach in creating main categories and an inductive content analysis approach in creating sub-categories that emerged from the raw data. In this manner, each stage of clinical supervision, pre-observation, classroom observation, supervisory feedback, professional support, and post-observation supervision were deductively analysed, and emerging sub-categories were inductively analysed from the data.

Both deductive and inductive content analysis involve three stages of content analysis: preparation, organization, and reporting the results (Elo et al., Citation2014). In the preparation stage, the study prepared semi-structured and FGDs protocols to allow narrative data collection from school heads, experienced teachers, and teachers. Also, the study underscored that school heads and teachers were potential resources for data generation. In the organization stage, each participant was given an independent code, and each semi-structured Interview and FGD category was assigned a different colour. The study generated unique words, and through Microsoft Office software, keywords were picked up with the help of word navigator, and the narrator (informant) was identified with his/her narrations.

The practices provide a means of describing and understanding the opinions of school heads and teachers on heads’ clinical supervision practices in developing teachers’ professional competencies. Narrative data were presented in Tables (statements) as sub-categories, presenting informants’ positive or negative opinions on teaching professional competencies development as results of school heads’ clinical supervision practices. Reporting the findings is the last stage. Findings were reported as the overall opinions of school heads and teachers regarding the contribution of school heads’ clinical supervision practices in developing teaching professional competencies before being discussed with the support from previous studies.

5.8.2. Quantitative analysis

The quantitative data were managed in the constructed database using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 25. Building the dataset followed Mertler and Vannatta’s (Citation2005) procedures: first, data were cleaned manually for completeness and accuracy, and procedures were followed continuously throughout data collection. Participants were re-contacted and asked to fill in any blanks or unanswered items in questionnaires. Second, managing quantitative data involved creating a codebook with all the collected data. The codebook (database) was created to gather socio-demographic information about the respondents and research items. Third, the data was screened to ensure each variable was assigned a suitable range of responses.

Descriptive analysis was performed to screen the data to ensure that outlier values were identified and resolved before data analysis. The results indicate that no missing values were detected in research items. Therefore, data were within an acceptable range, responses were complete, and all the necessary information was included in the dataset. The data were analysed using descriptive statistics to establish means and standard deviation. The findings were presented as means scores and standard deviation in Tables.

6. Objective of the research

The main objective of this study was to examine the extent to which school heads’ clinical supervision technical aspects enhance teachers’ professional competencies development in public secondary schools in Tanzania. One research question and six sub-questions guided the study:

To what extent do school heads’ clinical school supervision practices enhance the development of teachers’ professional competencies in public secondary schools?

Do you observe professional schemes of work, and how does this shape your teachers?

Do you observe lesson plans, and how does this shape your teachers?

How often do you observe classroom teaching? How does this affect your teachers?

Do you give feedback after classroom observation, and how does this impact your teachers?

Do you provide professional support to teachers regarding teaching practice, and what is this implication for your teachers?

Do you make teaching and learning follow-ups? How does this affect your teachers?

7. Findings

The narratives and descriptives findings are presented side by side to compare responses of the quantitative and qualitative dimensions and confirm how the findings converge or diverge from each other. The findings are presented in six categories: pre-observation of schemes of work, pre-observation of lesson plans, classroom observation, supervisory feedback, professional support, and post-observation.

7.1. Pre-observation of schemes of work

7.1.1. Research questions

Do you observe professional schemes of work, and how does this shape your teachers? Qualitative analysis shows that 82% (n = 23) of informants demonstrated that school heads’ supervision of schemes of work had contributed to developing teachers’ professional competencies. Their expressions are presented in three sub-categories: searching teaching and learning resources, understanding subject matter, and understanding teaching methods. There, 18% (n = 5) of informants disagreed with the views, and their negative expressions are found in one sub-category, disagreement on schemes of work. shows the responses.

Table 3. Scheme of work supervision and professional competencies (n = 28).

presents the means and standard deviations of teachers’ responses to school heads’ review of schemes of work and teachers’ professional competency development. An overall average means score was 1.87, indicating that teachers agreed that school heads’ review of schemes of work enhanced the development of teaching professional competency. The standard deviation was 0.844, which is low, indicating that the teachers were consistent in their responses about the contribution of school heads’ review of schemes of work in developing professional competency. The findings suggest that teachers grew professionally by identifying teaching and learning resources, improving knowledge on the subject, and designing participatory teaching and learning approaches.

Table 4. Scheme of work supervision and professional competency (N = 94).

7.2. Pre-observation of lesson plans

7.2.1. Research questions

Do you observe lesson plans, and how does this shape your teachers? Narrative analysis shows that 96% (n = 27) of informants had positive feelings about school heads’ review of lesson plans in line with developing teachers’ professional competencies. Teaching professional competencies are presented in three sub-categories: organising lessons, interactive teaching and learning, and evaluating teaching and learning practices. It was found that 4% (n = 1) of informants felt otherwise; the opposing viewpoint is in the serving school heads sub-category. The findings are presented in .

Table 5. Lesson plans and professional competencies (n = 28).

shows that the school heads’ review of lesson plans and teachers’ professional competency feelings had an average mean score of 1.79. Regarding standard deviation, the result was 0.756, which is low, indicating that teachers were consistent in their responses, meaning that they had a positive attitude towards developing professional competencies due to school heads’ review of lesson plans. The findings indicate that teachers strongly agreed that due to school heads’ review of lesson plans, they developed professional competencies such as organising the subject matter, engaging students in teaching and learning activities and setting appropriate teaching and learning objectives.

Table 6. Lesson plans supervision and professional competency (N = 94).

7.3. Classroom observation

7.3.1. Research questions

How often do you observe classroom teaching? How does this affect your teachers? The qualitative analysis has revealed that 78% (n = 22) of informants demonstrated that school heads were working with actual classroom observation supervision. The practices contributed to teaching professional competencies as presented in three sub-categories: teaching and learning prior preparation skills, evaluating teaching and learning, and interactive teaching and learning practices. There was 22% (n = 6) of informants demonstrated negative views that such practices were irregular, causing teachers not to receive instant professional support. Teachers’ negative responses are presented in the lack of instant classroom supervision sub-category. presents the findings.

Table 7. Classroom observation and teaching professional competencies (n = 28).

presents that school heads’ classroom observation enhances teachers’ professional competency development with an overall mean score of 2.0, suggesting that the more committed school heads towards classroom observation, the more teachers feel professionally competent. The relatively low standard deviation of 0.863 indicates a higher level of consensus among teachers regarding developing professional competence from school heads’ classroom observation. These findings indicate that teachers had positive perceptions by agreeing that school heads’ classroom observation influenced the development of teaching competencies such as conducting interactive teaching and learning activities, managing students in the classrooms, and assessing teaching and learning activities.

Table 8. Classroom observation and professional competency (N = 94).

7.4. Supervisory feedback

7.4.1. Research questions

Do you give feedback after classroom observation, and how does this impact your teachers? The narrative analysis results have shown that 67% (n = 19) of informants demonstrated that school heads’ were committed to supervisory feedback practices. It was noted that these informants expressed positive views regarding developing teaching professional competencies such as interactive teaching and learning practices. There was 33% (n = 9) of informants argued that supervisory feedback was collectively done. Negative thoughts are presented in one sub-category named collective feedback. These findings are presented in .

Table 9. Supervisory feedback and professional competencies (n = 28).

shows that school heads’ supervisory feedback and teachers’ feelings had an overall mean score of 1.86. The result indicates that teachers had positive perceptions by agreeing that supervisory feedback enhanced their professional competency. The standard deviation of 0.683, which is low, indicates that teachers were consistent in their responses. Due to school heads’ supervisory feedback, teachers’ professional competency in teaching and learning approaches, managing students in the classrooms, and evaluating teaching and learning practices improved significantly.

Table 10. Supervisory feedback and professional competency (N = 94).

7.5. Teaching professional support

7.5.1. Research questions

Do you provide professional support to teachers regarding teaching practice, and what is this implication for your teachers? The qualitative analysis revealed that 86% (n = 24) of informants presented positive views that teachers developed teaching competencies through school heads’ professional support for teachers. These are presented into two sub-categories: interactive teaching and learning practices, and evaluating students’ learning. It was also found that 14% (n = 4) of informants reported that school-based professional academic support was theoretical-based ideologies and insufficient to enhance teaching professional competencies in teachers. Informants’ negative thoughts are presented under the deficit in mentoring services sub-categories in .

Table 11. Professional support and professional competencies (n = 28).

presents that school heads’ professional support and teachers’ competency development had an overall mean score of 2.06, suggesting that teachers had positive perceptions by agreeing that school heads’ professional support for teachers improved their professional competencies development. The standard deviation of 0.876, which is low, highlights that teachers were consistent in their responses that they grew professionally due to school heads’ professional support. Such as managing students in teaching and learning activities, assessing students’ learning achievement, facilitating participatory teaching and learning methods, and evaluating the subject achievement.

Table 12. Professional support and professional competency (N = 94).

7.6. Post-observation

7.6.1. Research questions

Do you make teaching and learning follow-ups? How does this affect your teachers? The narrative analysis results have shown that 71% (n = 20) of informants demonstrated that school heads practiced teaching and learning supervision follow-up. It was regarded as a factor in developing teaching professional competencies in teachers. Positive responses are presented in two sub-categories: language of teaching and learning, and interactive teaching and learning. There, 29% (n = 8) of informants presented their negative thoughts in one sub-category: teaching and learning needs. shows the findings as follows:

Table 13. Post–observation and professional competencies (n = 28).

shows that school heads’ post-observation supervision and teachers’ teaching competency development had an overall mean score of 1.89. The result indicates that teachers had positive perceptions by agreeing that post-observation positively influenced their professional competency development. The standard deviation of 0.876 is low, indicating that teachers responded consistently and developed professional teaching competencies due to school heads’ post-observation. Such as participatory teaching and learning practices, skills in managing students in the classrooms, and assessing students’ learning achievement.

Table 14. Post-observation and professional competency (N = 94).

8. Discussion

8.1. Pre-observation of schemes of work

The study found that school heads were observing teachers’ scheme of work. School heads assisted teachers in selecting teaching and learning resources for preparing participatory teaching and learning activities. In agreement with scholars of clinical supervision, Cogan (Citation1973) and Goldhammer (Citation1969) state that clinical supervision practices count on reviewing teaching and learning materials before the actual teaching and learning processes.

Reviewing schemes of work is a vital role of Tanzanian school heads (United Republic of Tanzania, Citation2013). Teachers benefited from the practices as most of them were encouraged to conduct a situational analysis of the available teaching-learning resources within the working context before listing them in the schemes of work. To an end of designing interactive teaching and learning practices. These findings are consistent with the findings by Darmawati (Citation2021) and Maulidiansyah et al. (Citation2023), who discovered that school heads’ pre-observation activities, such as planning with teachers in implementing clinical supervision, helped teachers in preparing teaching and learning materials for quality teaching and learning activities in the classrooms.

The present study also found that school heads’ review of schemes of work encouraged teachers to read relevant teaching and learning materials, thus gradually improving their subject expertise. Teachers also grew professionally in searching for teaching and learning resources and designing methods for facilitating participatory teaching and learning to students. Teachers’ responses in the descriptive analysis suggest that teachers felt professionally growing in identifying relevant teaching and learning resources and designing appropriate teaching and learning approaches. It could be argued that schemes of work supervision were viewed as an essential factor that encouraged teachers to develop skills in identifying lesson requirements before actual teaching and learning practices.

The findings are consistent with those of Chinedu (Citation2021) and Mwesiga and Okendo (Citation2018), which suggest that clinically supervised teachers developed teaching competencies in teaching methods. Hence, teachers’ readiness for quality teaching and learning increases (Babo & Agustan, Citation2022; Maulidiansyah et al., Citation2023). It could be argued that school heads’ review of schemes of work in Tanzania’s public secondary schools played an important role in developing teachers’ teaching professional competency at the workplace.

8.2. Pre-observation of lesson plans

The study found that school heads observed lesson plans. Cogan (Citation1973) and Goldhammer (Citation1969) argue that supervising teachers’ lesson plan preparations and utilisations are essential in clinical supervision. Teachers must appear to the school heads and present orally what the students would learn by presenting the lesson plans (Goldhammer, Citation1969). Similarly, in Tanzania, school heads have to review teachers’ lesson plans to ensure the proper preparation of the lesson, delivery of lesson objectives and assess students’ learning achievement (United Republic of Tanzania, Citation2013).

It was found that school heads and teachers had positive perceptions of school heads’ review of lesson plans and teachers’ professional competency development. From a narrative point of view, teachers were found to have developed competencies regarding responding to students’ questions fluently and making all the students read together cheerfully. The findings reflect teachers’ strong agreement in the survey regarding developing competencies such as the ability to organize the subject matter, engaging students in teaching and learning, and setting teaching and learning objectives.

The present findings support the findings of Malunda, Onen, Musaazi, and Oonyu (Citation2016), who found that in Uganda, school heads’ review of lesson plans improved teachers’ pedagogical practices in the classroom. The present and previous findings (Malunda et al., Citation2016) diverge from Fussy’s (Citation2018) findings who found that most Tanzanian teachers felt that school heads’ review of lesson plans lacked feedback as the main concern was to check if teachers were fulfilling their professional duties.

Based on the interview and descriptive responses, school heads worked hard on reviewing teachers’ lesson plans and encouraged teachers to develop skills relevant to participatory teaching and learning practicum. These pedagogical practices are considered as teaching professional competencies from methodological and didactical perspectives (Beijaard et al., Citation2004; Cheng, Citation2021; Education International & UNESCO, Citation2019). It is argued that school heads’ lesson plans significantly influenced the development of teaching professional competencies in Tanzania’s workplaces. The present study’s findings and the previous ones match in highlighting the importance of supervision of lesson plans in developing teaching professional competency.

8.3. Classroom observation

The study found school heads practiced actual classroom observation. This was a good practice of clinical supervision as Cogan (Citation1973) and Goldhammer (Citation1969) state that school heads’ actual classroom observation is one of the core activities of the school heads that allow them to engage in the teaching process as one of the observed teachers. As a result of school heads and teachers’ interactions in the classroom, teachers felt that school heads were working with them, and conversations about teaching helped teachers to maximise teaching creativity. Similarly, studies findings by Musa and Binti (Citation2020) and Sule et al. (Citation2020) found that school heads’ direct classroom observation encouraged teachers to develop innovative teaching and learning activities that increased students’ morale to learning. It could be argued that a culture of working together between school heads and teachers in the classroom is essential for teaching innovation.

From the interview responses, school heads and teachers expressed positive perceptions that school heads’ classroom observation enhanced teachers’ skills before teaching and learning preparation. Likewise, descriptive results have shown teachers developed skills relative to engaging students in teaching and learning activities, evaluating the taught subject to the students, and capacity to manage students in the classroom.

Synonymously, clinical supervision positively influenced teachers in searching for new teaching and learning pedagogical practices (Malunda et al., Citation2016; Mette & Riegel, Citation2018), thereby attracting students to learning activities (Bencherab & Al Maskari, Citation2021; Dikeogu & Amadi, Citation2019). The present study’s findings and previous ones signify that regular classroom observation contributes to teaching professional competencies, primarily pedagogical professional competencies (Pennington & Richards, Citation2016).

8.4. Supervisory feedback

The study found school heads practiced supervisory feedback. School heads adhere to professional feedback agree with the United Republic of Tanzania (Citation2013) directive that classroom teaching and learning supervisory feedback are necessary for guiding teachers to adjust teaching methods and learning activities. Interview responses of school heads and teachers revealed that due to school heads’ supervisory feedback practices, teachers developed participatory teaching method competencies.

Similarly, the survey results also found that teachers agreed that supervisory feedback improved competencies in teaching and learning approaches, managing students in the classrooms, and evaluating teaching and learning activities. These findings concur with Khaef and Karimnia (Citation2021), who found that clinical supervision feedback was a tool for teachers’ teaching reflection and improved the quality of teaching-learning practices. The present study’s findings and previous ones suggest that teaching-learning supervisory feedback increased teachers’ attention to teaching students through participatory methods, which, in turn, made them competent in the teaching profession.

The study found few cases evidencing that school heads initiated collective supervisory feedback. From interview responses, teachers developed negative thoughts that collective supervisory feedback was ineffective in developing teaching professional competency. The present study argues that some school heads overlooked the provision of educative supervisory feedback to the teachers. Relatively, previous studies such as Aldaihani (Citation2017), Nabhani, Bahous, and Sabra (Citation2015), and William and Ligembe (Citation2022) found that schools provided teachers with unrealistic teaching and learning feedback, so teachers resisted receiving such reports. Based on the findings of the current and previous studies, one-to-one supervisory feedback for teachers enhanced teachers’ professional competency development compared to collective supervisory feedback.

8.5. Teaching professional support

The study found that school heads provided professional teaching support to teachers. The finding suggests that Tanzanian school heads ensured teachers are professionally assisted at the workplace (United Republic of Tanzania, Citation2013). The school heads and teachers confirmed the presence of the whole school’s professional development support. This formal in-service for teaching staff sought to equip teachers with skills for competence-based curriculum teaching and learning practicum.

These findings are highly consistent with the literature on school-based professional development for teachers (Bouchamma et al., Citation2019; Darling-Hammond & Richardson, Citation2009; Mahimuang, Citation2018; Sroinam, Citation2018; Sunaengsih et al., Citation2020). More specifically, teaching technical know-how incorporates teachers’ responsibilities for gaining knowledge through a school-based community of learning. The narrative and descriptive results converged positively on teachers’ professional growth relative to participatory teaching and learning practices, and evaluating the subject taught within the classroom.

From a descriptive point of view, there was general agreement among teachers that they developed skills for managing students in the classrooms and assessing students’ learning achievement. The current study’s findings support the previous ones by Husain et al. (Citation2019), Laguna et al. (Citation2023), and Musa and Binti (Citation2020) that clinical supervision practices developed teachers’ skills in constructing formative assessments. To specify the claim, Husain et al. (Citation2019) argue that due to school heads’ clinical supervision, teachers were highly influenced in testing students in classroom assignments and examinations.

These findings align with Nabhani, Bahous, and Sabra (Citation2015), who found that as a result of clinical supervision, both school supervisors and teachers were satisfied with the contribution of clinical supervision to the professional development of teachers in teaching and learning delivery. This development was attributed to collecting teachers’ learning needs assessment checklists included in the school’s plans for teachers’ professional development.

8.6. Post-observation

The study found that school heads adhered to post-observation supervision practices. Most school heads’ post-observation supervision comprised proper use of the language of instruction, team teaching and exchange teaching, and participatory teaching methods. The findings align with post-observation of classroom teaching and learning in the literature, such as Khaef and Karimnia (Citation2021) and Sule et al.(Citation2020). For example, Khaef and Karimnia (Citation2021) found that school heads were competent in post-observation supervisory feedback for teachers.

The interview responses further highlight the significance of post-observation and developing teaching competencies in the language of teaching and learning and interactive teaching and learning among teachers. Similarly, from descriptive responses, teachers expressed positive perceptions by agreeing that school heads’ post-observation enhanced competencies in participatory teaching, students' classroom management, and students’ learning achievement assessment. Teachers’ optimistic view on the effects of clinical supervision is recognised by Bello and Olaer (Citation2020), Ngwenya (Citation2020), and Nwankwoala (Citation2020), that post-observation positively influences teachers’ gaining techniques for improving teaching and learning instructions.

The present study here in Tanzania and others in Brazil and Nigeria, to mention a few, significantly added a clear picture that clinical supervision practices and, in particular, post-observation would contribute to teachers’ sense of professional competency development. Similarly, literature by Bello and Olaer (Citation2020) and Khaef and Karimnia (Citation2021) found that school heads’ post-observation improved teachers’ competencies in cooperating with students in teaching and learning practices. Pennington and Richards (Citation2016) consider that teachers’ language skills and knowledge of practicing teaching in the classroom are essential elements of teachers’ competence in the teaching profession.

9. Conclusions

The present study examined how technical aspects of school heads’ clinical supervision enhance teachers’ professional competencies development in public secondary schools in Njombe Region, Tanzania. The study underscores that teachers’ professional competencies grow gradually under clinical supervision practices. Some conclusions are made as follows:

The school heads’ review of the schemes of work was arguably the best pre-observation practice for teachers who required professional support in developing the teaching and learning preparations. With such practices, teachers were flexible in adjusting the schemes of work to achieve the lesson goals, especially if the lesson required additional materials unavailable in schools. These findings suggest that school heads’ schemes of work observation increased teachers' ability regarding the accumulation of teaching and learning resources from within the school environments. Hence, teaching-learning creativity developed among teachers.

The school heads continuously observed teachers’ lesson plan preparation. The practice holds information that school heads and teachers had a culture of discussing the lesson plans, and teachers received remarks for improvement. Teachers’ preparation of the lesson plans had become part of their professional lives, thus enabling some of them to note that lesson plans guided teachers in identifying students facing learning difficulties in the classrooms and trying to assist them.

The school heads’ actual classroom observation direct made them understand how teachers were teaching and how students were learning in the classrooms. These practices were as vital as they facilitated school heads and teachers’ discussions of teachers’ work. In turn, teachers learned how to engage students in active teaching and learning practices such as asking and answering questions posed by the teachers or peer students.

Teachers were satisfied with the school heads’ one-to-one supervisory feedback. In it, teachers felt being assisted in the proper practice of participatory methods, using teaching aids, lesson plans, and using English as a medium of instruction. Ultimately, it positively contributed to teachers’ sense of professional competency development at the workplace.

School heads ensured that teachers are professionally supported through a whole-school professional development programme. Teachers developed new thinking in search of new teaching and learning strategies and designing effective teaching and learning activities that touched each student. Thus, whole-school professional support was a positive factor contributing to teaching professional competency development among teachers at workplaces.

The school heads’ follow-ups were focused on improving the preparation and use of teachers’ professional documents, co-teaching, use of the medium of instruction, and application of the competence-based curriculum. Teachers whose thinking was positive on post-observation indicated they were flexible when learning the best teaching and learning practices for the student’s interest.

10. Implications of the study findings

10.1. Theoretical implications

School heads’ clinical supervision is a relevant approach to developing teachers’ professional competencies at workplaces. Clinical supervision is a bridge that significantly contributes to sustainable professional learning in teaching and learning settings. Conclusively, clinical supervision is an engine that produces positive mindfulness for teachers in developing workplace teaching professional competencies.

10.2. Practical implications

The study presents essential findings about the contribution of school heads’ clinical supervision to developing teachers’ competencies. First, the study found specific technical aspects of clinical supervision influenced monophonic teachers’ professional competencies. Pre-observation of schemes of work was a positive factor in developing teachers’ skills in searching teaching and learning resources, understanding subject matter, and understanding teaching methods.

The study found that pre-observation of lesson plans was a factor that enforced teaching competencies such as organizing lessons and facilitating learning. School heads’ classroom observation supervision was a factor that increased teachers’ skills before teaching and learning preparation. The study found that supervisory feedback improved teachers’ professional teaching commitments. Post-observation was a factor that increased teachers’ ability to exercise exchange teaching and learning, and use the English language as a medium of instruction for students.

Second, the study found multiple technical aspects of clinical supervision, such as pre-observation of lesson plans, classroom observation, supervisory feedback, professional support, and post-observation, enhanced teachers’ interactive teaching and learning practices in the classroom. These findings present unique information to the practitioners of the clinical supervision model as school heads and teachers; there are interconnected relationships between clinical supervision aspects in developing teachers’ professional competencies. Overall, each technical aspect of clinical supervision is a factor for teaching and learning interactive skills among teachers.

11. Limitations and future directions

This study was conducted in one Region using four secondary schools. Therefore, the findings of this study should not be generalized to all public secondary schools in Tanzania. Because the opinions of school heads and teachers on clinical supervision and teachers’ professional competency feelings are likely to differ from one Region to another. Concerning future directions, qualitative and quantitative data presented here, provide an initial, tentative link between clinical supervision and teachers’ professional competency development.

Therefore, it is suggested that future studies may continue exploring the influence of clinical supervision on teachers’ professional competencies development in different national and international locations. The study also suggests that future researchers are encouraged to use the conceptual framework () and quantitative cross-sectional study to test the effects of school heads’ clinical supervision practices in developing teachers’ professional competencies. As such, studies would provide strong evidence of the association between the two variables and particular school heads’ clinical supervision practices and teachers’ professional competency development.

Authors’ contributions

Linus Chaula: Developed and designed the study; collected raw data; formal analysed and interpreted the data; and wrote the research article. Godlove Lawrent and Iramba Freddie Warioba Iramba: writing—review and supervision

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the administration of the University of Dodoma and Njombe Region for granting research clearance to undertake this study. The Authors also wish to thank all school heads and teachers who participated in the study by providing their responses on the contribution of clinical supervision technical aspects in developing teachers’ professional competencies. The authors thank the anonymous peer reviewers for their constructive feedback on the article.

Disclosure statement

The Authors declare no conflict of interest concerning the research, authorships, and publication of this research article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Linus Chaula

Linus Chaula is a Ph.D candidate in the Department of Educational Management and Policy Studies at the University of Dodoma. He obtained his masters of educational planning and administration from Ruaha Catholic University, Tanzania (2016). He also obtained an advanced international diploma in educational planning and administration from the National University of Educational Planning and Administration from New Delhi, India (2018). He is a specialist in educational administration. His research interests are clinical school supervision, teachers’ professional identity development, school heads’ professional self-efficacy development, and public-private partnerships in School Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene.

Godlove Lawrent

Godlove Lawrent is a Senior Lecturer in the Department of Foundation and Continuing Studies at the University of Dodoma. His current research interests are in the professionalism of teachers and national educational policies.

Iramba Freddie Warioba Iramba

Iramba Freddie Warioba Iramba is a Lecturer in the Department of Educational Management and Policy Studies at the University of Dodoma. He is a senior supervisor in school leadership models, teaching professionalism, and educational management.

References

- Aldaihani, S. G. (2017). Effect of prevalent supervisory styles on teaching performance in Kuwaiti high schools. Asian Social Science, 13(4), 25. https://doi.org/10.5539/ass.v13n4p25

- Anangisye, W. A. L. (2011). Developing quality teacher professionals: A reflective inquiry on the practices and challenges in Tanzania. Africa-Asia University Dialogue for Education Development Report of the International Experience Sharing Seminar (2): Actual Status and Issues of Teacher Professional Development, 137–154.

- Ayeni, A. J. (2012). Assessment of principals’ supervisory roles for quality assurance in secondary schools in Ondo state, Nigeria. World Journal of Education, 2(1), 62–69. https://doi.org/10.5430/wje.v2n1p62

- Babo, R., & Agustan, S. (2022). Clinical supervision model to improve the quality of learning in elementary school. Jurnal Ilmiah Sekolah Dasar, 6(1), 85–94. https://doi.org/10.23887/jisd.v6i1.43470%0A

- Bajpai, S., & Bajpai, R. (2014). Goodness of measurement: Reliability and validity. International Journal of Medical Science and Public Health, 3(2), 112–115. https://doi.org/10.5455/ijmsph.2013.191120133

- Ballová Mikušková, E., Verešová, M., & Gatial, V. (2024). Antecedents of teachers’ professional competencies. Cogent Education, 11(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2023.2286813

- Beijaard, D., Meijer, P. C., & Verloop, N. (2004). Reconsidering research on teachers’ professional identity. Teaching and Teacher Education, 20(2), 107–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2003.07.001

- Bello, A. T., & Olaer, J. H. (2020). Influence of clinical supervision of department heads on the instructional competence of secondary school teachers. Asian Journal of Education and Social Studies, 12(3), 42–50. https://doi.org/10.9734/ajess/2020/v12i330314

- Bencherab, A., & Al Maskari, A. (2021). Clinical supervision: A genius tool for teachers’ professional growth. The Universal Academic Research Journal, 3(2), 51–57. https://doi.org/10.17220/tuara.2021.02.11

- Bojo, S. A., & Mustapha, A. (2017). Rethinking strategies of the modern supervision: Scope, principles, and techniques. International Journal of Topical Educational Issues, 1(2), 384–398.

- Bouchamma, Y., April, D., & Marc, B. (2019). Principals’ supervision practices and sense of efficacy in professional learning communities. The Journal of Educational Thought, 52(2), 162–181. https://doi.org/10.2307/26873099

- Carr, D. (2000). Professionalism and ethics in teaching. Routledge Taylor & Francis Group.

- Chen, Y., Li, X., & Li, Y. (2022). Exploring the relationship between individual characteristics and argumentative discourse styles: The role of achievement goals and personality traits. Disciplinary and Interdisciplinary Science Education Research, 4(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43031-022-00062-1

- Cheng, L. (2021). Implications of English as a foreign language or English as a second language teachers’ emotions in their professional identity development. Journal of. Frontiers in Psychology, 12(September), 755592. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.755592

- Chinedu, O. (2021). Role of instructional supervision on teachers’ effectiveness in secondary schools in Enugu State. Global Journal of Education and Humanities, 1(1), 26–34.

- Chiwamba, S. V., Mtitu, E., Kimatu, J., & Ogondiek, M. (2022). Influence of heads of school instructional supervision practices on teachers’ work performance in public secondary schools in Lindi region-Tanzania. Journal of Education and Practice, 13(14), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.7176/JEP/13-14-01

- Cogan, M. (1973). Clinical supervision. Houghton Mifflin.

- Creswell, J. W. (2014). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed approaches. SAGE Publications, Inc.

- Darling-Hammond, L., & Richardson, N. (2009). How teachers learn. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. 66(5), 46–53.

- Darmawati, D. (2021). Supervision of school principal clinical in junior high school. (JPGI (Jurnal Penelitian Guru Indonesia)), 6(2), 397–401. https://jurnal.iicet.org/index.php/jpgi https://doi.org/10.29210/021062jpgi0005

- Dikeogu, M. A., & Amadi, E. C. (2019). Influence of school supervision strategies on teachers’ job performance in senior secondary schools in rivers State, Nigeria. International Journal of Innovative Development and Policy Studies, 7(4), 45–54. www.seahipaj.org

- Dilekçi, Ü., & Limon, İ. (2022). The relationship between principals’ instructional leadership and teachers’ positive instructional emotions: Self-efficacy as a mediator. Journal of Educational Leadership and Policy Studies, 6(1), 1–20.

- Dreyer, J. M., & Musundire, A. (2019). Effectiveness of the developmental supervision model as a tool for improving the quality of teaching in Gauteng, South Africa. Africa Education Review, 16(2), 109–125. https://doi.org/10.1080/18146627.2018.1454841

- Education International and UNESCO. (2019). Global framework of professional teaching standards. In Education International Education International.

- Elo, S., Kääriäinen, M., Kanste, O., Pölkki, T., Utriainen, K., & Kyngäs, H. (2014). Qualitative content analysis: A focus on trustworthiness. SAGE Open, 4(1), 215824401452263. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244014522633

- Elo, S., & Kyngäs, H. (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62(1), 107–115. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x

- Enyonam, R., & Mensah, A. (2020). Perception of teachers on instructional supervision in public basic schools in the Pokuase education circuit in the Ga-North municipality of the greater Accra region of Ghana. European Journal of Education Studies, 7(6), 196–219. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3686763

- Fuller, C. M., Simmering, M. J., Atinc, G., Atinc, Y., & Babin, B. J. (2016). Common methods variance detection in business research. Journal of Business Research, 69(8), 3192–3198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.12.008

- Fussy, D. S. (2018). The institutionalization of teacher ethics in Tanzania’s secondary schools: A school heads’ perspective. Pakistan Journal of Education, 35(2), 79–96. https://doi.org/10.30971/pje.v35i2.542

- García-Martínez, I., & Tadeu, P. (2018). The influence of pedagogical leadership on the construction of professional identity. Systematic review. Journal of Social Studies Education Research, 9(3), 145–162. https://doi.org/10.17499/jsser.90982

- Garman, N, University of Pittsburgh. (2020). Dream of clinical supervision, critical perspectives on the state of supervision, and our long-lived accountability nightmare. Journal of Educational Supervision, 3(3), 7–17. https://doi.org/10.31045/jes.3.3.2

- Gheyle, N., & Jacobs, T. (2017). Content analysis: A short overview. In Internal research note. (Internal Research Note). https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.33689.31841

- Goldhammer, R. (1969). Clinical supervision. Holt, Rinehart, and Winston.

- Goodson, I., & Hargreaves, A. (2003). Teachers’ professional lives (3rd ed.). In I. F. G. and A. Hargreaves (Eds.). Taylor and Francis e-Library.

- Grimmett, P. P. (1981). Clinical supervision and teacher thought processes. Canadian Journal of Education, 6(4), 23–39.

- Gürsoy, E., Kesner, J., & Salihoglu, U, Uludag University. (2016). Clinical supervision model in teaching practice: Does it make a difference in supervisors’ performance? Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 41(11), 61–76. https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2016v41n11.5

- Haris, I., Naway, F. A., Pulukadang, W. T., Takeshita, H., & Ancho, I. V. (2018). School supervision practices in the Indonesian education system; perspectives and challenges. Journal of Social Studies Education Research, 9(2), 366–387. https://doi.org/10.17499/jsser.17724

- Hubbard, H. R. (2021). Classroom teachers construct their professional identity after earning a teaching English to speakers of other languages graduate degree. The University of Alabama.

- Husain, H., Ghavifekr, S., Rosden, N. A., & Hamat, Z. W. (2019). Clinical supervision: Towards effective classroom teaching. Malaysian Online Journal of Educational Sciences, 7(4), 30–42. http://mojes.um.edu.my

- Kaur, M. (2018). Exploring teachers professional identity: Role of teacher emotions in developing professional identity. Bioscience Biotechnology Research Communications, 11(4), 719–726. https://doi.org/10.21786/bbrc/11.4/24

- Keiler, L. S. (2018). Teachers’ roles and identities in student-centered classrooms.International Journal of STEM Education, 5(1), 5–34. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40594-018-0131-6

- Khaef, E., & Karimnia, A. (2021). Effects of implementing clinical supervision model on supervisors’ teaching perspectives and qualifications: A case study in an EFL context. Education Research International, 2021, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/6138873

- Kock, N. (2017). Common method bias: A full collinearity assessment method for PLS-SEM. In R. N. H. Latan (Ed.), Partial least squares path modeling: Basic concepts, methodological issues and applications (pp. 245–275). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-64069-3

- Kock, F., Berbekova, A., & Assaf, A. G. (2021). Understanding and managing the threat of common method bias: Detection, prevention, and control. Tourism Management, 86, 104330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2021.104330

- Laguna, D., Velasco, R. Y., & Banayo, A. F. (2023). Clinical observation approach in promoting instructional competence among public school teachers in Calauan sub-office, division of Laguna. International Journal of Research Publications, 127(1), 150–159. https://doi.org/10.47119/IJRP1001271620235053

- Liljenberg, M., & Blossing, U. (2021). Organizational building versus teachers’ personal and relational needs for school improvement. Improving Schools, 24(1), 5–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/1365480220972873

- Mahimuang, S. (2018). Professional learning community of teachers: A hypothesis model development [Paper presentation]. The 2018 International Academic Research Conference, 229–235.

- Malunda, P., Onen, D., Musaazi, J. C. S., & Oonyu, J. (2016). Instructional supervision and the pedagogical practices of secondary school teachers in Uganda. Journal of Education and Practice, 7(30), 177–187.

- Marczyk, G., Dematteo, D., & Festinger, D. (2015). Essentials of research design and methodology. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Marshall, C., & Rossman, G. B. (2016). Designing qualitative research (Sixth). SAGE Publication, Inc.