?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Academic Development Programmes (ADPs) are a distinct category of South African Higher Education that aims to provide alternative access to students who meet the minimum entry requirements for university but not necessarily for the particular academic programme of their choice. Although these programmes have existed for over 30 years, limited rigorous and systematic evaluations of their impact have been conducted. This study examines the effect of one such programme on graduation outcomes at a South African university using logistic regression (LR) and propensity score weighting methods (IPTW). Our sample was restricted to 1852 students who began their studies in 2014, 2015 and 2016. These students were tracked for six years to ensure a realistic graduation period. The results indicate that ADP students had a higher first to second-year progression rate than their regular entry counterparts. Moreover, the results from the descriptive analysis, LR and IPTW collectively suggest a graduation advantage for the ADP students compared to their regular entry counterparts. In other words, the educational interventions provided by the ADP in the first year of university study positively influenced the alternative access students’ academic performance, particularly their graduation rates after four or five years, relative to their mainstream peers.

REVIEWING EDITOR:

SUBJECTS:

Introduction

Globally, participation in Higher Education has been marked by social inequalities for many years (Evans et al., Citation2019). In South Africa (SA), these inequalities have a long history that dates back to the apartheid education system, which was fragmented along racial lines. Although many years have passed since the demise of apartheid, its legacy continues to frame the educational experiences of many young South Africans (de Clercq, Citation2020; McKeever, Citation2017) and is mainly manifested in the low participation and low university throughput of Black South African students (Department of Higher Education and Training, DHET, Citation2019a). To illustrate, only 40-50% of each cohort of South African students successfully complete high school, with only 15-16% of high school leavers entering Higher Education (DHET, Citation2019b; Young, Citation2016). When disaggregated by race, approximately 4% of Black South Africans aged 18-29 have access to Higher Education, relative to 17-20% of their Indian and White counterparts. Most of these Black South African students are first-generation university students from low-income families, a factor which has been shown to negatively affect their academic prospects (Vincent & Hlatshwayo, Citation2018). In addition to low participation, the South African Higher Education system is also plagued by high attrition rates. Several studies suggest that approximately 50% of South African students make it to graduation, although these statistics vary by discipline and/or institution (DHET, Citation2019a; Murray, Citation2014; Paideya & Bengesai, Citation2021). There is also evidence that close to 20% of first-time-entering South African students leave at the end of the first year, while less than 30% graduate in regulation time (Centre for Higher Education, CHE, Citation2013; Khuluvhe et al., Citation2021).

To address this broad social issue, the SA government, like elsewhere in the world (Burke, Citation2017; Chowdry et al., Citation2013; Evans et al., Citation2019), has developed several policies aimed at widening participation and improving university throughput rates. One such policy is the Foundation Provisioning, which was instituted in 2004 (CHE, Citation2013; Leibowitz & Bozalek, Citation2016) to provide access to students from disadvantaged backgrounds who are generally underprepared for university education (Dhunpath & Subbaye, Citation2018). The SA government’s commitment towards widening access can be seen in the financial investment into Foundation Provisioning Programmes (referred to as Academic Development Programmes [ADPs] or the Foundation Phase [FP] henceforth), which has increased by almost 300%, from approximately ZAR 85 million in 2004 to ZAR 336 million in 2017 (Dhunpath & Subbaye, Citation2018). Currently, ADPs exist in some form in 24 out of 26 universities across SA (Garraway & Bozalek, Citation2019).

ADPs are not unique to South Africa. Many countries internationally have been building their educational policies around increasing participation of ‘non-traditional students’- a term which has considerable fluidity due to the multiple and often overlapping forms of diversity students bring (McCall et al., Citation2020; Johnson & O’Keeffe, Citation2016). The term ‘non-traditional students’ has been used to refer to i) mature students- usually defined as at least 21 years old at the time of enrolment (Hayman et al., Citation2024); ii) students who are different from the majority of students in terms of background factors such as race, socio-economic status, first-generation etc., (McCall et al., Citation2020); or iii) students at risk of dropping out due to the above factors, working and studying or inadequate entry qualification (Raaper et al., Citation2022). Thus, academic development programmes worldwide might differ at institutional and perhaps national levels due to the profile of the students targeted. However, they all aim to deal with the inevitable challenges of diversity in the student population that go hand in hand with the massification of higher education.

Different terminologies have also been used to refer to AD programmes. In the United Kingdom (UK), terms such as access (McMullin, Citation2017), pre-sessional, or foundation (Schmidt-Unterberger, Citation2018) have been used. Other terms that exist in the literature include pre-university (McDougall, Citation2019, Australia); bridging programmes- (Black, Citation2023 UK); Greer et al., 2020, United States of America, USA; Johnson & O’Keeffe, Citation2016, Ireland; Ssempebwa et al., Citation2012, Uganda) or developmental education (Umbauch et al., Citation2020, USA).

While these programmes have become popular as an alternative access route to students who might otherwise not have qualified for certain degree programmes, they have also been widely criticised for not providing evidence of impact (Scott, Citation2017; Umbauch et al., Citation2020). In the South African context, a major criticism is that the throughput of ADP students is considered to be much lower than the national cohort (DHET, Citation2019a). While many practitioners have sought to provide counter evidence of efficacy, as seen in some conference proceedings, particularly the Higher Education Learning and Teaching Association of Southern Africa (HELTASA) conferences, where practitioners regularly report on the success of ADP interventions in the courses they teach (HELTASA, Citation2018; Garraway, Citation2009), these criticisms cannot be dismissed outright. This is because ADPs in SA remain marginalised, both as a field of inquiry and of practice (Ogude & Rollnick, Citation2022). The lack of impact studies also means that ADP students continue to shoulder the blame for poor pass rates at the institutional level. As such, the present study attempts to address some of these arguments by examining the impact of an ADP programme on academic outcomes. We specifically focus on whether the graduation outcomes of ADP students are comparable to those of their regular entry counterparts. To facilitate this comparison, we use a method that controls for imbalances by matching sets of treated and untreated individuals who share a similar value of the propensity score.

History of ADPs in South Africa

Although the term ‘academic development’ was first used in SA in the 1990s, its conceptual origins can be traced back to the 80s, when some more liberal universities began admitting a few Black students in response to the relaxation of apartheid policies (Boughey & Niven, Citation2012). During this period, academic development (AD) work was mainly advisory, focusing on remedial support and equipping students with the academic and language skills needed to improve their chances of university success (McKenna, Citation2012; Scott, Citation2017). Most of these programmes were also adjuncts, located outside mainstream teaching, and often were the responsibility of ‘enthusiastic, idealistic, junior staff’ (Boughey & Niven, Citation2012; Grayson, Citation2010), who were paid with donor funding. Since 2004, ADPs have been funded by DHET to execute an key objective set out in Education White Paper 3 (Department of Education, DoE, 1997), namely, to increase equity in access and outcomes (Leibowitz & Bozalek, Citation2016). The new policy also required Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) to move away from adjunct programmes and to develop fully articulated, credit-bearing, extended degree programmes (McKenna, Citation2012), also referred to as the Foundation Phase (FP), particularly in the university under study.

A perusal of the literature reveals some attempts to assess the effectiveness of these programmes. Both qualitative (Craig, Citation2017; Ogude et al., Citation2021; Pearce et al., Citation2016) and quantitative studies (Chetty, Citation2014; Mabila et al., Citation2006; McKay, Citation2016; Smith et al., Citation2013) have been conducted, with most of these suggesting that ADPs have been beneficial, and a few others indicating otherwise (Smith et al., Citation2013). Most of these studies have focused on course performance and progression to the mainstream programme or first-year level (Mabila et al., Citation2006; Slabbert & Friedrich-Nel, Citation2016). Of the few that have provided evidence of efficacy at the programme level (Smith, Citation2009; Commerce); (Smith et al., Citation2013, Commerce, Engineering & Science); (Mabila et al., Citation2006), a critical question that scholars have grappled with is how to create a comparable counterfactual, given the differences in entry requirements between the two groups. Despite these methodological challenges, AD practitioners are still expected to provide evidence of the effectiveness of these programmes in order to secure their continuation.

Our work, therefore, contributes to this ongoing discourse on ADPs by employing a propensity score-based method to assess the effectiveness of an AD programme on graduation outcomes. We opted to use this approach because it enables us to mimic a hypothetical experiment, allowing us to compare students with similar propensities based on observed characteristics (Schudde & Keisler, Citation2019). In particular, we highlight recent methodological advances that involve weighting subjects by the inverse probability of treatment (Austin & Stuart, Citation2015).

Characteristics of the ADP under investigation

The student profile

In SA, the Foundation Provisioning Policy (FPP) allows for five models, which range from an entirely foundational programme, where students do a full year of pre-university level modules, to a fully integrated model where the first year is spread over the first two years of study (McKenna, Citation2012). The present analysis focuses on a programme that takes the former format, where courses are added to the front-end of the curriculum. This programme was instituted in the College of Law and Management Studies at a South African university in 2014.

Although the FPP recommends that the students enrolled in this ADP must come from disadvantaged schools and have at least one Admission Point Score (APS) below the mainstream programme requirement, in reality, several factors influence whether a student will end up in the ADP or not. For instance, the APS (colloquially known as matric points) required for entry into a mainstream Bachelor of Commerce degree is 30 APS with a level 4 (minimum 50%) in Mathematics. For admission into the ADP, a student might meet the minimum APS for the mainstream degree programme but may have a level 3 (40%). Another instance where admission into the ADP may be granted is when a student who wants to enrol in the BCOM degree programme has at least 29 APS with a level 5 for Mathematics. In both instances, where the minimum Mathematics score or the minimum APS has not been attained, students are placed in the ADP as they do not meet the entry requirements for the mainstream programme.

In addition to matric points or APS, the school quintile system, which is used to categorise schools based on socio-economic status, as measured by the average income, poverty rates, and literacy levels of the surrounding community, is also used to determine admission (South Africa Government Gazette 31496, Citation2008). Hence, without other indicators, the school quintile can be used as a proxy for socio-economic status. Quintile 1 schools are the most disadvantaged and usually found in rural communities, while quintile 5 are found in the most economically advantaged communities. These socio-economic differences are also reflected in the quality of education and, by extension, educational outcomes, with disparate performance observed between learners from quintile 5 schools and the rest of the education system (Spaull, Citation2015).

In principle, the students enrolled in the ADP should come from school quintiles 1-3, which are the most disadvantaged schools. However, as explained above, it is not uncommon for students from high-ranking quintiles 4-5 to also be enrolled in this particular ADP if they have lower entry points than required for admission to the regular entry programmes. This admission criterion allows two students from the same disadvantaged quintile to be separated by just one APS, enabling one to enter the mainstream and the other the ADP. Given that ADPs are intended to assist students in developing sound academic and social foundations (CHE, Citation2013), which are necessary for success in university, an assumption might be made that the student who enters the ADP will benefit from this form of support, while the other, who has the same disadvantaged background but enters the mainstream programme, will be at a disadvantage.

The content of the ADP

ADP students in the university under study must complete six foundational modules during the first year, as shown in . A general guiding principle in the ADP curriculum is that the course content does not necessarily have to be similar to the content of level 1 of the mainstream programme. Where similar concepts are taught, as in elementary micro-and macroeconomics, the foundation level is introductory in nature, while the mainstream level provides more depth. Overall, all the courses taught at the foundation level are carefully selected to develop academic literacy for commerce as well as to provide a broad base for basic quantitative and analytical skills required in subsequent economics, mathematics, and statistics modules. These courses also run concurrently throughout the ADP year to promote knowledge transfer between the subjects.

Table 1. Structure of the curriculum.

In addition, academic skills such as goal setting, study skills, time management, and psycho-social support are integrated into the programme. Moreover, student performance is closely monitored, although this support is ‘abruptly’ withdrawn at the end of the foundation year, leaving students to transition to level 1 of the mainstream programme on their own; another valuable area of research, but which is beyond the scope of this study.

Factors influencing student success

Given that our focus is on comparing the academic outcomes of ADP students and their regular entry counterparts, it is essential to consider factors that influence these outcomes. Accordingly, we drew insights from prior research on student persistence (Braxton et al., Citation1997; Tinto, Citation1993). We used Tinto’s model of student persistence as a starting point in selecting variables to include in our model, given its ‘near-paradigmatic status’ in student persistence research (Braxton et al., Citation1997), especially in SA (Tinto, Citation2014).

The key argument in Tinto’s model is that students bring many diverse attributes, which, combined with institutional experiences such as academic and social integration, can either hinder or facilitate their persistence to graduation (Tinto, Citation1993). These attributes include background characteristics (e.g. family background, pre-entry academic attributes) and a combination of intentions, goals and commitments. Tinto (Citation1993) explained that intentions were exemplified by a student’s choice of a major subject or intended career, which are shaped by pre-entry attributes and reshaped by institutional experiences and, ultimately, goal and institutional commitment. He also linked students’ institutional experiences to academic and social systems and argued that the more students engaged in activities related to academic success (such as lecture attendance, consultation with lectures, library use, etc.) and interactions with significant individuals in the university, the more likely they will remain enrolled until graduation.

Several scholars have empirically tested Tinto’s theory and identified several testable propositions, some of which are partially supported in different types of institutions. Thus, while there is a wide array of factors that can be operationalised to explain each of the key points in Tinto’s theory, Braxton et al. (Citation2014) advise that there is no ‘one size fits all’ approach to student persistence; therefore, research should explore and those propositions that apply to the type of institution under investigation.

In this study, we assume that pre-entry attributes such as school background, academic factors such as matriculation points and the number of credits accumulated in the first year of study, and institutional factors such as on-campus residence and financial aid and academic support are all associated with persistence to graduation. We also include race and gender, given that academic performance in SA is generally disaggregated by these two factors (Paideya & Bengesai, Citation2021; Schreiber & Yu, Citation2016).

Apart from aligning with Tinto’s theory, the above attributes or factors were carefully chosen based on contemporary South African Higher Education debates. For instance, there is considerable debate regarding the academic preparedness of students and, in particular, the extent to which high school performance, represented by admission point scores (APS), regardless of whether the school is classified as disadvantaged or not, is a true reflection of students’ potential in Higher Education (Murray, Citation2017; Schaap & Luwes, Citation2013). Commentators argue that most first-year students, regardless of their school quintile, generally lack the basic knowledge needed for university studies, a phenomenon referred to as the ‘articulation gap’ in South African literature (Scott & Ivala, Citation2019). This articulation gap is attributed to grade inflation, which is a result of government’s pressure to produce better matric results (Tewari & Ilesanmi, Citation2020). Hence, students who enter university with higher points may have unrealistic expectations of their academic abilities. This then begs the question of whether students who are separated by just one or two points significantly differ in their future academic performance. The question becomes particularly important when considering that most South African students come from similarly disadvantaged backgrounds, especially at the university under study, where more than 65% of the student population comes from disadvantaged socio-economic and educational backgrounds (Bengesai & Pocock, Citation2021). Thus, regardless of the one or two points differences between mainstream and ADP students, the majority of the student body faces largely similar background challenges.

Financial aid is a significant factor in the democratisation of higher education (Nguyen et al., Citation2019)– especially in the context of widening participation where students from diverse socio-economic backgrounds are enrolled. In SA, the significance of financial aid in student persistence was especially brought to the fore during the 2015/2016 student protests (#feesmustfall), which centred around the high tuition fees and registration costs that posed barriers to student enrolment (Naidoo & McKay, Citation2018). These protests were, therefore, a pointed critique of both HEIs and the government for their perceived lack of commitment to supporting students in achieving their educational goals. Research also confirms that financial support is crucial in influencing a student’s choice to enrol in a university and their decision to stay on (Bengesai & Pocock, Citation2021; Nguyen et al., Citation2019). This is because students with financial aid might have less financial anxiety and distraction, enabling them to entirely focus on their academic pursuits and commit to their educational goals.

Other factors that have been identified as influencing student persistence include performance in the first year (Bengesai & Pocock, Citation2021; Paideya & Bengesai, Citation2021) and academic support. Despite their significance, these are among the least empirically tested propositions in the South African literature. We address this gap by including first-year accumulated credits (FYAC) as a proxy for academic performance in the first year. FYAC reflects the rate at which students earn credits toward their degree and serves as an indicator of their progress and success in their courses (Paideya & Bengesai, Citation2021). In addition, we consider the uptake of academic support interventions as an indicator of academic integration. Students who actively use academic support resources such as supplemental instruction or tutoring will likely be better integrated into the academic environment and better equipped to overcome academic challenges (Tinto, Citation2014). We also assume that students who reside on university campuses have increased community and social integration, especially for quintile 1-3 students whose background experiences might differ significantly from those of their counterparts from suburban areas (Walker & Mathebula, Citation2020).

We acknowledge that the above are not the full range of factors influencing graduation rates. Indeed, research has shown that other factors, such as the student’s family background, the language of learning, and other non-cognitive factors, such as self-efficacy, significantly affect academic attainment (McKay, Citation2016; Schaap & Luwes, Citation2013). Nonetheless, our analysis is limited to the data archived at the institution in question. While omitting these other variables can potentially introduce some form of bias, we contend that our analysis remains informative for the institution in question as this is the first study to evaluate the efficacy of the particular ADP. Further, to the best of our knowledge, not many South African studies investigating ADPs have used as many variables as we do. Even with these limitations in mind, our analysis is far more rigorous than other analyses undertaken of South African ADPs.

Materials and methods

Data description

We employed a retrospective observational study approach and extracted data from the administrative records of the university under investigation. Prior to accessing the data, permission was obtained from the Registrar’s Office. Ethical clearance for the study was also granted by the relevant authorities. For this study, we extracted data on 1887 incoming students beginning 2014-2016 who were tracked for six years (for each cohort), ensuring a realistic graduation period. Of these, 1446 were enrolled directly into the mainstream programme, while 441 came in through the AD programme.

At the institution under investigation, a fully Foundational model (1 + 3) consisting of one year of preparatory coursework followed by a three-year BCOM curriculum was adopted. In this model, progression to the regular mainstream programme depends upon completing the ADP modules. Thus, students who fail any ADP module are considered unprepared for the mainstream Bachelor of Commerce curriculum. These students are excluded and often redirected into other programmes they qualify for based on their AP scores. Nonetheless, some of these students leave the university and, thus, cannot graduate from any degree programme. As such, the analysis undertaken in this study focuses on those students who successfully completed the ADP year and compares their academic performance with their mainstream counterparts. We also include those redirected into other programmes as a sub-group. We did the same for the mainstream students, given that most students do not persist in their declared major (Bengesai & Pocock, Citation2021). However, we exclude those who left the university before the end of the ADP year as they did not have the chance to graduate in the BCOM programme or any other programme within the university. Including this group would introduce a confounding factor that may skew the results. Thus, after excluding ADP students who did not articulate to the mainstream programme (), our analytical sample comprises 1852 (1446 mainstream and 406 ADP students (see ).

Table 2. Descriptive analysis of the sample according to their mode of entry (n = 1852).

Table 3. Retention statistics.

Variable definitions

Outcome variable

The outcome variable of interest for the multivariable analysis was persistence to graduation (Yes = 1; No = 0); which indicates whether a student has graduated from the registered programme or not. We further disaggregate this variable to denote the duration it took the student to graduate as follows:

Regulation time - graduation in three years

Regulation time plus one - graduation within four years

Regulation time plus two - graduation within five years

Regulation time plus three- graduation in six years

Independent variable of interest (intervention)

We used a binary indicator, subsequently referred to as the intervention variable, to identify students entering the ADP and define students enrolled in the programme as having the ‘intervention’ (ADP = 1), while the others, referred to as the mainstream, are the comparison group (ADP = 0).

Other independent variables (covariates)

We acknowledge some methodological issues that should be considered when performing this type of analysis. First, meaningful comparisons can only be made if there are similarities between the regular entry students and their ADP counterparts. Hence, we opt to include several covariates informed by our conceptual framework as well as the availability of data. As such, we include the following covariates or controls: pre-entry attributes/academic preparedness- (school quintile (1-5); and APS (continuous); background factors- gender (male/female) and race (Black South African/Other); factors that may influence social integration (campus residence (yes/no); institutional support (financial aid receipt (yes/no). We also considered whether students attended supplemental tutorials offered as part of academic support (AMS). This variable is continuous and indicates the frequency with which a student has used this service (from 0 to 18). To account for cases where students transferred to different degree programmes within the university, we included an indicator (0 = no, 1 = yes) indicating whether a student switched their degree. This allowed us to track all students who initially enrolled in the BCOM programme, ensuring us to track their persistence to graduation.

Data analysis

For the analysis, we employed multiple methods, ranging from descriptive statistics, logistic regression, and propensity score technique to assess the impact of the ADP on students’ performance. Combining these different models allowed us to assess the robustness of findings under different modelling assumptions. Thus, we leverage the strengths of both methods to obtain more reliable estimates of the effectiveness of the ADP programme.

We acknowledge that only a carefully designed randomised experiment can efficiently estimate causal effects because it guarantees that study participants in the intervention groups will not differ substantially in their baseline characteristics. Further, proper randomisation usually reduces the probability of selection bias by balancing both known and unknown background factors (Rosenbaum & Rubin, Citation1983). However, randomised experiments are not feasible in many situations, such as educational research or behavioural science. Therefore, our study adopted a quasi-experimental design, enabling an observational study to mimic a hypothetical experiment. We use the propensity scoring technique to adjust for the non-randomisation of students to the intervention group (ADP) or the comparison group (mainstream). The propensity score is the probability of an individual or unit being assigned the intervention, conditional on the measured background covariates (Austin, Citation2011; Rosenbaum & Rubin, Citation1983). Although different methods of calculating the propensity score have been described in the literature (Pan & Bai, Citation2015), we utilise the inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) in this study.

IPTW analysis

While reducing treatment selection bias and potential confounding factors, we estimated the impact of the AD programme on students’ graduation status using IPTW via the following procedures. First, we performed a binary logistic regression model of main effects by regressing the intervention variable (a binary indicator of AD qualification) on all the covariates to generate propensity scores. Second, we used the estimated propensity scores to weight the probability of the ith student being in the intervention (AD qualification) or comparison group (mainstream). Weights for students with AD qualifications were assigned to be

while weights for the mainstream students were

Intuitively, we weight students in the intervention group by the inverse of the probability of getting the ‘treatment’, while students in the comparison group are weighted by the inverse of the probability of not getting the ‘treatment’.

The objective of IPTW adjustment is to create a weighted sample in which the distribution of the background covariates is the same between the intervention and comparison control groups. We thus verified that covariate balance had been induced in each of the reweighted synthetic populations by comparing and examining their absolute standardised mean differences (ASMDs) (Austin & Stuart, Citation2015). We then estimated the average treatment effect (odds ratio) of the AD programme for all the students by regressing graduation status on an indicator variable denoting whether a student was admitted through the AD programme. Next, we conducted a sensitivity analysis using the tesensitivity package and the conditional independence assumption (Masten & Poirier, Citation2018). This approach considers a class of assumptions called conditional c-dependence where c = 0 represents conditional independence and c > 0 suggests that only conditional independence partially holds. Therefore, we cannot estimate the true value of intervention effects; instead, we only get bounds. How small or large the bounds correspond to how sensitive the results are. The tesensitivity package also provides a breakdown point on the data under which the condition holds.

We first present the descriptive statistics of the sample (). This is followed by the distribution data on the two indicators used to place students in the ADP programme ( and ). Next, we present data on ADP students who articulated to the mainstream programme as well as a comparative analysis of this sub-group and the regular access students in terms of first to second-year progression (), as well as time to graduation (). Finally, we present logistic regression and IPTW results for the three graduation indicators used in this study ().

Table 4. Effect estimation of the ADP on graduation status.

Preliminary analysis

Only a few variables had missing values. In dealing with this omission, the missing indicator method is used for the quintile variable, where ‘missing’ is made a separate category (Stuart, Citation2010; D’Agostino et al., 2001).

Exploratory results analysis

Distribution of the sample

As illustrated in , the analytical sample of 1852 students, of whom 406 (21.9%) were admitted through the ADP, while the remaining 1446 (78.1%) were mainstream students. The mean APS was significantly higher in the mainstream group than in the ADP group. Also, the percentage of mainstream students receiving financial aid was notably lower than those in the ADP group (p < 0.001). The proportion of mainstream students from the most advantaged school quintiles 4-5 was markedly higher than those in the ADP group (p < 0.001). Significantly, more students in the ADP group resided in the university residences than the mainstream students. However, gender distribution and FYAC were comparable between the groups (p > 0.05).

also shows that the unadjusted raw data had a relatively high degree of covariate imbalance. Seven of the ten covariates had ASMD values above the 0.25 threshold. We opted to use this threshold, considering the inherent difficulty in achieving perfect balance given the diverse entry pathways of the groups under study. Our aim was to strike a balance between statistical precision and covariate balance, recognising the practical challenges associated with comparing groups entering through distinct pathways. Also, this threshold aligns with established practices in other studies (Normand et al., Citation2001).

After applying the IPTW adjustment, the ASMD values of these covariates were within the threshold for 8 out of 10 variables in our model. Although the unadjusted ASMDs were lower than the adjusted for two of our covariates, gender and first-year accumulated credits, the final values were still within the recommended threshold. However, the AMS variable remained unbalanced despite the iterative refitting of the propensity scores model. We acknowledge this as a limitation of our model, however, considering the importance of academic support in student persistence- we still opted to retain it in the analysis.

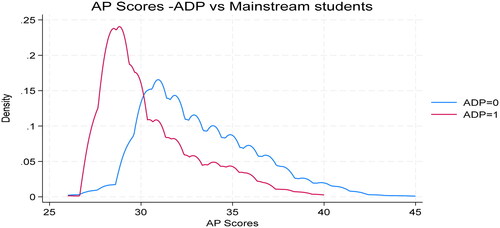

Distribution of AP scores (APS) for ADP and mainstream entry students

As shown in , APS for the ADP students ranged between 26 and 41, while for the mainstream students, they ranged between 28 and 50. This is despite the minimum entry points for both programmes being 28 (ADP) and 30 (mainstream). Hence, it is possible that the few records with 25 APS were due to errors in data capture. Another interesting finding from this graph is that although ADP students have fewer points overall than their direct entry counterparts, a considerable number had comparable APS to their mainstream peers. Given that the premise for registering in the ADP is to help these students meet mainstream requirements, it can be argued that whatever differences exist between the groups, participation in the ADP can help in addressing them.

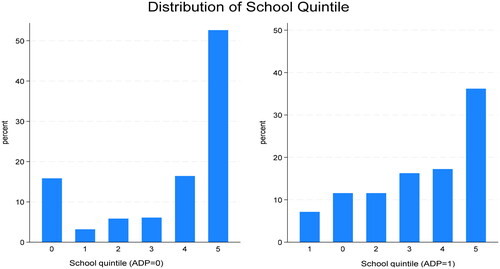

Distribution of school quintile: AD students and regular entry students

Similarly, the students sampled are spread across all school quintile levels, although for regular entry mainstream students, the majority are from quintile 5 schools (). This is not surprising, given that the university under study, as mentioned earlier, generally caters mostly to students from disadvantaged backgrounds.

Comparison of retention statistics (ADP vs mainstream students)

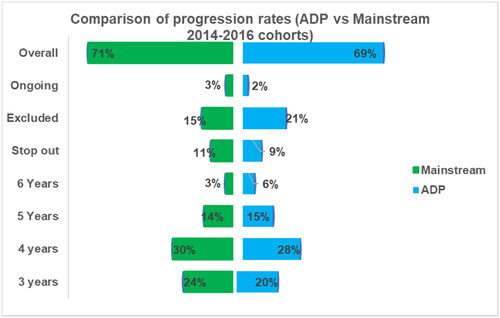

presents a comparison of retention statistics for ADP and mainstream students.

Students who fail any course in the ADP are excluded and cannot progress to the mainstream programme. In other words, these students are weeded out and deemed not ready for mainstream studies. shows that 23 students (12.9%); 5 (5.2%) and 7 students (4.19%) from the 2014, 2015 and 2016 ADP cohorts, respectively, did not progress to the mainstream programme and neither did they enrol in other programmes within the university. In other words, the articulation rate was 87% in 2014, 95% in 2015 and 96% in 2016. The ADP students who articulated progressively into the mainstream programme had a higher first to second-year retention rate than their directly enrolled counterparts. On average, the first-year retention rate for the ADP was 97%, while for the mainstream students, it was 89%. compares the progression rates and time to graduation of the ADP students and their mainstream counterparts.

Regarding time-to-graduation, the descriptive statistics shown in indicate that 24% of the ADP students who articulated to the mainstream programme graduated in regulation time, i.e. three years, relative to 20% of the BCOM mainstream students. The six-year graduation rate for the ADP students was 71% vs 69% for their mainstream counterparts. There was a higher exclusion rate among ADP students (21%) in the mainstream vs 15% of their mainstream counterparts. Conversely, the stop-out rate was slightly lower for ADP students (9%) compared to 11% for their mainstream peers. Although these differences in percentage points seem marginal, they suggest noteworthy trends in the data that require further investigation. As our multivariate analysis will show, even these small differences have meaningful implications for understanding the significance of the ADP intervention in students’ success.

Association between graduation status and mode of entry

To systemically investigate the effect of the ADP on graduation, we first completed a logistic regression analysis, followed by an IPTW analysis. Because we are interested in the effect of an ADP before and after controlling for the background covariates, we only report the odds ratios (OR), p-values and confidence intervals (CI) for the ADP variable. All other covariates are omitted from the regression analysis results (see ).

Across all three models, the results suggest that students who were enrolled in the ADP programme had better odds of graduating than their mainstream counterparts. In the unadjusted model, the odds of graduating ranged from OR = 1.23 -1.26) in favour of the ADP students. In the adjusted regression model, ADP students were up to two times more likely to graduate in regulation time (3 years), which is significantly higher than the mainstream students (OR = 1.98, 95% CI: 1.41-2.77). Similarly, the odds of graduating in regulation plus one (4 years, OR = 1.80, 95% CI:1.35-2.39); regulation plus two (5 years, OR = 1.56, 95% CI: 1.12-2.10 or regulation plus three (6 years, OR = 1.36, 95% CI: 1.01-1.85) were significantly higher for the ADP students relative to their mainstream counterparts.

The results from the IPTW analysis also supported the conclusion of significantly higher odds of graduating for ADP students. The odds of graduating in regulation time for the ADP students (OR = 1.34, 95% CI: 0.79-1.89); regulation time plus one year (OR = 1.76, 95% CI 1.28-2.25); regulation plus two years (OR = 2.24, 95%, CI: 1.69-2.79) or regulation plus three years (OR = 2.38, 95% CI: 1.82-2.94) were significantly higher for ADP students relative to their mainstream counterparts.

We also conducted a sensitivity analysis to assess the robustness of our findings. As shown in , our conclusions are sensitive to the variations in the conditional independence assumption. In our case, the breakdown point of our data is 0.030. also shows that the conclusion holds at the 50th percentile (P50) for almost all of our covariates (except AP scores). At the 75th percentile (P75), the conclusion only holds for eight of the variables and only four at the 90th (P90). Thus, the conclusion held well at the 50th percentile but showed reduced consistency at higher levels. Therefore, our findings should be interpreted with these limitations in mind.

Table 5. Sensitivity analysis.

Discussion

In this study, we examined the impact of an ADP where study skills, academic literacy and a few select subjects are added to the front-end of the curriculum. This programme was introduced in 2014, and this study represents the first formal evaluation thereof. Our results show that the ADP students who articulated to the mainstream programmes had better first to second-year progression rates than their mainstream counterparts. The descriptive statistics also showed a marginal graduation advantage for the ADP students, which was particularly noticeable in graduation in regulation time, where a four-percentage difference was observed.

These findings were also confirmed in the regression models and the IPTW analysis, where the graduation advantage of ADP students was significantly higher across all four graduation statuses. Thus, our findings suggest that despite entering university with slightly lower AP scores, most ADP students in our sample caught up with their direct entry counterparts, with some even surpassing them. These promising results align with most of the descriptive analyses found in much of the literature in South Africa, where ADPs have been reported as successful in overall completion rates (CHE, Citation2013; Garraway, Citation2009; Smith, Citation2009). For instance, Garraway found that completion rates at the University of the Witwatersrand for their ADP students were over 50% compared with just under 50% for mainstream Black students. The study by Smith (Citation2009) found that ADP students in a front-loaded programme, such as the ADP analysed in this study, outperformed their peers enrolled in the mainstream. This effect was more pronounced for African students. However, in a follow-up version of the study, Smith et al. (Citation2013) found the opposite, as students enrolled in different models of ADPs were found to have lesser odds of graduating. The authors attributed these contradictory findings to several factors, such as additional covariates, student cohort differences, and a larger sample. It is also important to note that they used a different analytical method in the later study.

Elsewhere, Ssempebwa et al. (Citation2012) found no significant difference in the mean grade point average (GPA) of students enrolled in the bridging programme and those admitted through conventional routes in a Ugandan university. Cohort studies from the USA (Greer et al., Citation2023; Umbauch et al., Citation2020) and the UK (Black, Citation2023) have also shown promising results for front-end support. Notably, Umbauch et al. (Citation2020), who also used a similar analytical approach as our study, found that high school students who enrolled in college through developmental programmes had a more or less similar likelihood of earning a degree as their regular entry counterparts. While we recognise that the programmes examined in these studies may differ in content and delivery methods, our findings suggest that developmental support, in whatever form, can potentially benefit underprepared students.

The findings from this study also raise significant implications for ADPs and South African Higher Education in general. As the CHE (Citation2013) report points out, ADP students would not have qualified for admission to the corresponding mainstream curriculum based on their APS. Hence, without the ADPs, these students with the potential to add to human capacity development would not have had the opportunity to do so (Mabila et al., Citation2006). This is particularly important considering that the progression rates for direct entry students are generally poor, with most completing their degrees in regulation plus one year (Bengesai & Pocock, Citation2021; CHE, Citation2013; Paideya & Bengesai, Citation2021). Thus, overall, the identified ADP did not just provide access to disadvantaged students but also improved the academic success rates of the students who articulated to the first level of the BCOM programme.

This then raises the question: could underperforming mainstream students in SA universities benefit from educational interventions similar to those offered in ADPs? If so, what structural changes would need to be made to ensure that mainstream students benefit from such support (Shay et al., Citation2016)? In essence, the findings from our study emphasise the potential scalability and applicability of successful ADP components to improve the overall academic success of a broader student population within SA higher education. Nonetheless, while we assume that the integration of academic and quantitative literacy, as well as essential academic skills such as goal setting, time management, and psycho-social support, might have equipped students with the necessary tools needed for a successful transition to university life (McKay, Citation2016), further research is needed to verify this in practice.

Drawing on Tinto’s work, the findings from this study also suggest that while many factors influence the academic performance of students from disadvantaged backgrounds, academic under-preparedness might be one of the most critical factors (Tinto, Citation2014. Therefore, structured academic support, such as that provided by ADPs, not only provides a supportive learning environment for underprepared students- but might also equip them with the tools to succeed academically.

The issue of academic under-preparedness is not new in South Africa. It has been the subject of discussion about possible solutions. For instance, the CHE has proposed the introduction of flexible curricula where students can opt in or out of an ADP to developing a common first-year supported curriculum for all students (CHE, Citation2013; Shay et al., Citation2016). However, these proposals have not been adopted mainly due to financial and logistical constraints (Shay et al., Citation2016). Further, the Foundation Provision Policy has capped the ADP intake to at least 20% of the first-time entering undergraduate students (DHET, 2020)- making it impossible for universities to enrol more students in these programmes. It may also be argued that the lack of rigorous studies on the effectiveness of these ADP programmes potentially limited the attention given to the proposal for flexible curricula, as there is still uncertainty regarding their effectiveness in the South African Higher Education sector. It is hoped that the current study and others to come will provide evidence-based motivation for reforming undergraduate curricula to align with South African students’ realities, especially at the institution under investigation.

Limitations

Although our study makes some significant contributions to the literature on the effects of ADP support on student outcomes, the findings should be interpreted with some limitations in mind. Firstly, while the use of IPTW is an improvement over the existing research on the effectiveness of ADPs, the technique does not address unmeasured confounding. We acknowledge that other factors may have greater predictive power beyond what we included in this study. Nonetheless, our analysis was limited to the data archived by the institution under study. Secondly, ADP students bring with them different pre-entry attributes, particularly their APS, which makes direct comparison difficult. However, using a propensity score technique with sensitivity analysis in this study provides an avenue for addressing this limitation within reasonable conditional independence assumptions. Thus, while we do not claim the generalisability of our findings to other contexts or different ADPs, we believe that our analytical approach could be applied to other studies where the focus is on estimating the direct impact of ADPs on student performance and throughput rates. Such impact studies can assist university administrators in making evidence-based decisions about the most effective structure and implementation of ADPs in South African Higher Education institutions.

Recommendations

Despite these limitations, our study provides some valuable insights that can be used to improve the effectiveness of ADPs and promote student success. Considering that ADPs can potentially improve student outcomes, there is a need for South African HEIs, particularly the university under study, to consider investing in and improving existing ADPs. This could include allocating additional resources beyond government funding to improve staffing, infrastructure, and programmatic support. While increasing the number of students enrolled in the ADP may be restricted by the enrolment caps imposed by the Foundation provisioning policy, integrating the successful components of the ADPs into the mainstream programme may expand support to a broader student population. To effectively do this, continuous monitoring and evaluation of the programme is crucial to ensure it is being implemented as intended in terms of design, objectives and curriculum alignment. This will ensure implementation fidelity and facilitate the transfer of successful components of the ADP to other academic programmes. Qualitative studies are also needed to understand students’ experiences during their participation in the ADP and transition to the mainstream programme. Understanding students’ experiences beyond the ADP year is critical to refining the programme, addressing student needs and optimising support mechanisms. In the long run, the CHE recommendation for a flexible curriculum also presents an opportunity for institutions to address academic under-preparedness while supporting most students during their first year of study. This is critical as the first year is a critical determinant of future academic success.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study highlights the significant positive impact of the AD programme on student progression and graduation rates. ADP students not only caught up with their mainstream counterparts but often surpassed them. Thus, the evidence provided by this study can be used to inform policy and further research to refine ADP programmes, ensuring they meet the evolving needs of South African higher education. As institutions continue to seek ways to support their diverse student bodies, implementing some of these recommendations could enhance success and promote equity in higher education.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Registrar’s Office and the Department of Institutional Intelligence at the institution under study for authorising access to the data.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Annah Vimbai Bengesai

Annah Vimbai Bengesai, PhD, is the Head of Teaching and Learning at the University of KwaZulu-Natal. Her research interests are in social statistics, institutional research on student access and success, and the demography of education.

Lateef Babatunde Amusa

Lateef Babatunde Amusa, PhD, is a lecturer and researcher at the University of Ilorin. His research interests are in Biostatistics, public health, and machine learning.

References

- Austin, P. C. (2011). An introduction to propensity score methods for reducing the effects of confounding in observational studies. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 46(3), 399–424. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273171.2011.568786

- Austin, P. C., & Stuart, A. (2015). Moving towards best practice when using inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) using the propensity score to estimate causal treatment effects in observational studies. Statistics in Medicine, 34(28), 3661–3679. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.6607

- Bengesai, A. V., & Pocock, J. (2021). Patterns of persistence among engineering students at a South African university: A decision tree analysis. South African Journal of Science, 117(3/4), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.17159/sajs.2021/7712

- Black, A. M. (2023). The role of bridging programmes in supporting student persistence and prevention of attrition: A UK case study. Studies in Higher Education, 2023, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2023.2269246

- Boughey, C., & Niven, P. (2012). The emergence of research in the South African Academic Development movement. Higher Education Research & Development, 31(5), 641–653. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2012.712505

- Braxton, J. M., Doyle, W. R., Hartley, H. V., Hirschy, A. S., Jones, W. A., & McLendon, M. K. (2014). Rethinking college student retention. Jossey Bass.

- Braxton, J. M., Sullivan, A. S., & Johnson, R. M. (1997). Appraising Tinto’s theory of college student departure. In J. Smart (Ed.), Higher education: Handbook of theory and research (pp. 107–164). Agathon Press.

- Burke, P. J. (2017). Access to and widening participation in higher education. In J. C. Shin & P. Teixeira (Eds.), Encyclopedia of international higher education systems and institutions (pp. 1–7). Springer.

- Centre for Higher Education (CHE). (2013). A proposal for undergraduate curriculum reform in South Africa: The case for a flexible curriculum structure. CHE.

- Chetty, N. (2014). The first-year augmented programme in Physics: A trend towards improved student performance. South African Journal of Science, 110(1/2), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1590/sajs.2014/20120096

- Chowdry, H., Crawford, C., Dearden, L., Goodman, A., & Vignoles, A. (2013). Widening participation in higher education: Analysis using linked administrative data. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series A: Statistics in Society, 176(2), 431–457. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-985X.2012.01043.x

- Craig, T. (2017). Enabling capabilities in an engineering extended curriculum programme. In B. Bangeni & R. Kapp (Eds.), Negotiating learning and identity in higher education: Access, persistence and retention (pp. 133–154). Bloomsbury.

- D'Agostino, R., Lang, W., Walkup, M., Morgan, T., & Karter, A. (2001). Examining the impact of missing data on propensity score estimation in determining the effectiveness of self-monitoring of blood glucose (SMBG). Health Services and Outcomes Research Methodology, 2(3/4), 291–315. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1020375413191

- de Clercq, F. (2020). The persistence of South African educational inequalities: The need for understanding and relying on analytical frameworks. Education as Change, 24, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.25159/1947-9417/7234

- Department of Higher Education and Training (DHET). (2019a). 2000 TO 2016 first time entering undergraduate cohort studies for public higher education institutions. DHET.

- Department of Higher Education and Training (DHET). (2019b). A 25 year review of progress in the basic education sector. DHET.

- Dhunpath, R., & Subbaye, R. (2018). Student success and curriculum reform in post-apartheid South Africa. International Journal of Chinese Education, 7(1), 85–106. https://doi.org/10.1163/22125868-12340091

- Evans, C., Rees, G., Taylor, C., & Wright, C. (2019). ‘Widening Access’ to higher education: The reproduction of university hierarchies through policy enactment. Journal of Education Policy, 34(1), 101–116. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2017.1390165

- Garraway, J. (2009). Success of foundation (extended programmes) in engineering and sciences. In HELTASA. Success stories in foundation/Extended Programmes. Higher Education Learning and Teaching Association of South Africa (HELTASA).

- Garraway, J., & Bozalek, V. (2019). Theoretical frameworks and the extended curriculum programme. Alternation - Interdisciplinary Journal for the Study of the Arts and Humanities in Southern Africa, 26(2), 8–35. https://doi.org/10.29086/2519-5476/2019/v26n2a2

- Grayson, F. (2010, 20-23 June 2010). ENGAGE: An extended degree program at the University of Pretoria in South Africa. Paper presented at the American Society for Engineering Education Annual Conference and Exposition, Louisville, Kentucky.

- Greer, C., Chi, C., & Hylton-Patterson, N. (2023). An empirical evaluation of a summer bridge program on college graduation at a Small Liberal Arts College. Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice, 24(4), 909–923. https://doi.org/10.1177/1521025120960035

- Hayman, R., Wharton, K., Bell, L., & Bird, L. (2024). Navigating the first year at an English university: Exploring the experiences of mature students through the lens of transition theory. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 43(1), 39–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/02601370.2023.2297671

- HELTASA. (2018). HELTASA. 2018 Conference Proceedings. Retrieved from https://heltasa2018.mandela.ac.za/getmedia/8620ee79-8cfc-4b5c-9aac-27e8aeb57787/Heltasa-proceedings-WEB?disposition=attachment

- Johnson, P., & O’Keeffe, L. (2016). The effect of a pre-university mathematics bridging course on adult learners’ self-efficacy and retention rates in STEM subjects. Irish Educational Studies, 35(3), 233–248. https://doi.org/10.1080/03323315.2016.1192481

- Khuluvhe, M., Netshifhefhe, E., Ganyaupfu, E., & Negogogo, V. (2021). Post-school education and training monitor: Macro-indicator trends. Department of Higher Education and Training.

- Leibowitz, B., & Bozalek, V. (2016). Foundation provision – A social justice perspective. South African Journal of Higher Education, 29(1), 8–25. https://doi.org/10.20853/29-1-447

- Mabila, T. E., Malatje, S. E., Addo-Bediako, A., Kazeni, M. M. M., & Mathabatha, S. S. (2006). The role of foundation programmes in science education: The UNIFY programme at the University of Limpopo, South Africa. International Journal of Educational Development, 26(3), 295–304. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2005.08.004

- Masten, M. A., & Poirier, A. (2018). Identification of treatment effects under conditional partial independence. Econometrica, 86(1), 317–351. https://doi.org/10.3982/ECTA14481

- McCall, D., Petrakis, M., & Western, D. (2020). Opportunities for change: What factors influence non-traditional students to enrol in higher education? Australian Journal of Adult Learning, 60, 89–112.

- McDougall, J. (2019). ‘I never felt like I was alone’: A holistic approach to supporting students in an online, pre-university programme. Open Learning: The Journal of Open, Distance and e-Learning, 34(3), 241–256. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680513.2019.1583098

- McKay, T. J. M. (2016). Academic success, language, and the four year degree: A case study of a 2007 cohort. South African Journal of Higher Education, 30(4), 190–209. https://doi.org/10.20853/30-4-570

- McKeever, M. (2017). Educational inequality in Apartheid South Africa. American Behavioral Scientist, 61(1), 114–131. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764216682988

- McKenna, S. (2012). The context of access and foundation provisioning in South Africa. In R. Dhunpath & R. Vithal (Eds.), Alternative access to higher education: Underprepared students or underprepared institutions Cape. Pearson Education South Africa.

- McMullin, P. (2017). Access programmes and higher education outcomes. In J. Cullinan, & D. Flannery (Eds.), economic insights on higher education policy in Ireland. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-48553-9_6

- Murray, M. (2014). Factors affecting graduation and student dropout rates at the University of KwaZulu-Natal. South African Journal of Science, 110(11/12), 6. https://doi.org/10.1590/sajs.2014/20140008

- Murray, M. (2017). How does the grade obtained at school for English and Mathematics affect the probability of graduation at a university? Pythagoras, 38(1), a335. https://doi.org/10.4102/pythagoras.v38i1.335

- Naidoo, A., & McKay, T. J. M. &. (2018). Student funding and student success: A case study of a South African University. South African Journal of Higher Education, 32(5), 158–172. https://doi.org/10.20853/32-5-2565

- Nguyen, T. D., Kramer, J. W., & Evans, B. J. (2019). The effects of grant aid on student persistence and degree attainment: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the causal evidence. Review of Educational Research, 89(6), 831–874. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654319877156

- Normand, S. T., Landrum, M. B., Guadagnoli, E., Ayanian, J. Z., Ryan, T. J., Cleary, P. D., & McNeil, B. J. (2001). Validating recommendations for coronary angiography following acute myocardial infarction in the elderly: A matched analysis using propensity scores. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 54(4), 387–398. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0895-4356(00)00321-8

- Ogude, N. A., Majozi, P. C., Mathabathe, K. C., & Mthethwa, N. (2021). The management of student success in extended curriculum programmes: A case study of the University of Pretoria’s Mamelodi Campus, South Africa. South African Journal of Higher Education, 35(4), 237–252. https://doi.org/10.20853/35-4-4242

- Ogude, N. A., & Rollnick, M. (2022). Ideological positioning of extended curriculum programmes – A case study of a large South African research university. South African Journal of Higher Education, 36(2), 222–238. https://doi.org/10.20853/36-2-4526

- Paideya, V., & Bengesai, A. V. (2021). Predicting patterns of persistence at a South African university: A decision tree approach. International Journal of Educational Management, 35(6), 1245–1262. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEM-04-2020-0184

- Pan, W., & Bai, H. (2015). Propensity score analysis: Concepts and issues. In W. Pan, & H. Bai (Eds.), Propensity score analysis: Fundamentals and developments (pp. 3–19). Guilford Publications.

- Pearce, H., Campbell, A., Tracy, C., Le Roux, P., Nathoo, P., & Vicatos, E. (2016). The articulation between the mainstream and extended degree programmes in engineering at the University of Cape Town: Reflections and possibilities. South African Journal of Higher Education, 29(1), 150–163. https://doi.org/10.20853/29-1-451

- Raaper, R., Brown, C., & Llewellyn, A. (2022). Student support as social network: Exploring non-traditional student experiences of academic and wellbeing support during the Covid-19 pandemic. Educational Review, 74(3), 402–421. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2021.1965960

- Rosenbaum, P. R., & Rubin, D. B. (1983). The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika, 70(1), 41–55. https://doi.org/10.1093/biomet/70.1.41

- Schaap, P., & Luwes, M. (2013). Learning potential and academic literacy tests as predictors of academic performance for engineering students. Acta Academica, 45, 181–214.

- Schmidt-Unterberger, B. (2018). The English-medium paradigm: A conceptualisation of English-medium teaching in higher education. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 21(5), 527–539. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2018.1491949

- Schreiber, B., & Yu, D. (2016). Exploring student engagement practises at a South African university: Student engagement as reliable predictor of academic performance. South African Journal of Higher Education, 30(5), 157–175. https://doi.org/10.20853/30-5-59

- Schudde, L., & Keisler, K. (2019). The relationship between accelerated Dev-Ed coursework and early college milestones: Examining college momentum in a reformed mathematics pathway. AERA Open, 5(1), 233285841982943. https://doi.org/10.1177/2332858419829435

- Scott, I. (2017). Academic development in South African higher education. In E. Blitzer (Ed.), Higher education in South Africa (pp. 21–49). Sun Press.

- Scott, C. L., & Ivala, E. N. (2019). Moving from apartheid to a post-apartheid state of being and its impact on transforming higher education institutions in South Africa. In Transformation of higher education institutions in post-apartheid South Africa (1st ed., pp. 12). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351014236

- Shay, S., Wolff, K., & Clarence-Fincham, J. (2016). New generation extended curriculum programmes: Report to the DHET. Univesity of Cape Town.

- Slabbert, R., & Friedrich-Nel, H. (2016). Extended curriculum evolution: A road map to academic success? South African Journal of Higher Education, 29(1), 45–59. https://doi.org/10.20853/29-1-458

- Smith, L. C. (2009). Measuring the success of an academic development programme: A statistical analysis. South African Journal of Higher Education, 23(5), 1009–1025. https://doi.org/10.4314/sajhe.v23i5.48813

- Smith, L. C., Case, J. M., & Van Walbeek, C. (2013). Assessing the effectiveness of academic development programmes: A statistical analysis of graduation rates across three programmes. South African Journal of Higher Education, 28(2), 624–638.

- South Africa. (2008). Amended national norms and standards for school funding. In Government Gazette 31496(1087). Government Printers.

- Spaull, N. (2015). Schooling in South Africa: How low-quality education becomes a Poverty trap. 2015. In A. De Lannoy, S. Swartz, L. Lake, & C. Smith (Eds.), South African child gauge (pp. 34–40). Children’s Institute, University of Cape Town.

- Ssempebwa, J., Eduan, W., & Mulumba, F. N. (2012). Effectiveness of university bridging programs in preparing students for university education: A case from East Africa. Journal of Studies in International Education, 16(2), 140–156. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315311405062

- Stuart, E. A. (2010). Matching methods for causal inference: A review and a look forward. Statistical Science: A Review Journal of the Institute of Mathematical Statistics, 25(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1214/09-STS313

- Tewari, D. D., & Ilesanmi, K. (2020). Teaching and learning interaction in South Africa’s higher education: Some weak links. Cogent Social Sciences, 6(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2020.1740519

- Tinto, V. (1993). Leaving college: Rethinking the causes and cures of student attrition (2nd ed.). The University of Chicago Press.

- Tinto, V. (2014). Tinto’s South Africa lectures. Journal of Student Affairs in Africa, 2(2), 5–26. https://doi.org/10.14426/jsaa.v2i2.66

- Umbauch, P. D., Clayton, A. B., & Smith, K. N. (2020). Developmental education’s effect on graduation and labor market outcomes. Journal of Developmental Education, 43(2), 10–17.

- Vincent, L., & Hlatshwayo, M. (2018). Ties that bind: The ambiguous role played by social capital in black working class first-generation South African students’ negotiation of university life. South African Journal of Higher Education, 32(3), 118–138. https://doi.org/10.20853/32-3-2538

- Walker, M., & Mathebula, M. (2020). Low-income rural youth migrating to urban universities in South Africa: Opportunities and inequalities. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 50(8), 1193–1209. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2019.1587705

- Young, D. G. (2016). The case for an integrated approach to transition programmes at South Africa’s higher education institutions. Journal of Student Affairs in Africa, 4(1), 1.