Abstract

Within the literature, there is a well-established relationship between alcohol use and risky sexual behaviour. Three different but related explanations have been identified to account for the relationship, namely social, biological and individual. Although these explanations and the associated factors have been well explored in the literature, there is currently no empirical initiative that has shown how these factors interact with each other within the alcohol use and risky sexual behaviour relationship. The aim of the systematic review is to review and synthesise existing literature on the relationship between alcohol use and risky sexual behaviour among young adults (18–24 years old). Seventy-one articles were included in the review subsequent to a systematic search of the literature. The review highlighted three thematic domains relating to personality influences, social determinants and interpersonal factors, contributing to a more comprehensive understanding of these factors. At a foundation level, more research is required to gain new insights, discover new ideas and/or increase knowledge of a phenomenon, i.e. factors influencing the relationship between alcohol use and risky sexual behaviour among young adults.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

There is a substantial body of evidence documenting the relationship between alcohol use and risky sexual behaviour. However, there is a dearth of empirical evidence highlighting the nature and complexity of this relationship, especially as it relates to intensity and frequency of alcohol use and contextual variables such as socio-economic status as well as gender and age. Similarly, the links between motivations for alcohol use and sexual behaviours are not well understood. Furthermore, it is noteworthy that the alcohol use–risky sexual behaviour link has not been adequately explored in young adults. The current study reviewed the literature available since 2000 relating to factors contributing to why young adults engage in alcohol use and risky sexual behaviour. A systematic review of global research was conducted. Results indicated that personality influences, social determinants and interpersonal factors were related to alcohol use and risky sexual behaviour.

1. Introduction

There is a substantial body of evidence documenting the relationship between alcohol use and risky sexual behaviour (see Adams et al., Citation2014; Campbell, Williams, & Gilgen, Citation2002; Fritz et al., Citation2002; Mbulaiteye et al., Citation2000; Weiser et al., Citation2006). While the literature indicates a relationship between alcohol use and risky sexual behaviour, there is little empirical evidence highlighting the nature and complexity of this relationship, especially as it relates to intensity and frequency of alcohol use and contextual variables such as socio-economic status as well as gender and age (Cooper & Orcutt, Citation2000; Leigh & Stall, Citation1993). Similarly, the links between motivations for alcohol use and sexual behaviours are not well understood (Patrick & Maggs, Citation2010). It is noteworthy that high-risk sexual behaviours and the resulting health effects disproportionately affect young people.

Evidence from a 2010 National Survey on Drug Use and Health conducted among young people, predominantly urban youth located in New York City, indicated that alcohol use was highest among young adults from 21 to 25 years of age with 45.5% of these individuals reporting binge drinking and 18% reporting heavy drinking (binge drinking on five or more days) in the past month (Griffin, Scheler, Acevedo, Grenard, & Botvin, Citation2012). Furthermore, in a study conducted in the US, approximately 50% of all new sexually transmitted infections (STIs) in the US occurred among 15–24 year olds, and almost 50% of all new HIV infections in the US occurred in young people aged 24 years or under (CDC, Citation2003, Griffin et al., Citation2012). Brown and Vanable (Citation2007) also found that alcohol use prior to a sexual encounter was strongly correlated to unprotected sexual intercourse encounters involving casual partners. Important to note previous research has focused on adolescents or youth in formal educational settings (Pithey & Morojele, Citation2002), in other words those attending school, college and/or university. Additionally, it is important at this point to note the definition of both adolescents and young adults.

According to the APA (Citation2002), the most commonly used chronologic definition of adolescence includes ages 10–18; nevertheless, it could include 9–26 years depending on the source. “The current lack of consensus of an operational definition of adolescent chronology can be attributed to a number of factors, including: the appreciated continuity of human development; a recognition of individual, cultural, gender and racial variability; the ascribed relative salience of specific developmental milestones, and a perpetually refined science of human development in a dynamically evolving society” (Curtis, Citation2015, p. 9). Curtis (Citation2015) proposes an operational definition of adolescence based in developmental science that includes ages from 11 to 25 years. In this definition, “early adolescence” and “young adulthood” are substages of this critical transitional period. With early adolescence ranging from 11 to 13 years, adolescence from 14 to 17 years and young adulthood from 18 to 24 years old. For the purpose of this study, Curtis’ (Citation2015) operational definition will be taken into account when referring to young adults.

The relationship between alcohol use and risky sexual behaviour is complex and cannot be explained by a single mechanism. This relationship instead reflects multiple underlying causal and non-causal processes (Cooper, Citation2006). While there is a clear relationship between alcohol use and risky sexual behaviour, research identifies them as two separate variables interacting at a specific given point. The use of alcohol has globally been identified as the third leading risk factor for poor health (World Health Organisation (WHO), Citation2010). The deleterious effects of alcohol result in an estimated 2.5 million deaths every year, of which a significant proportion occur amongst young people (WHO, Citation2010). Previous research has shown that a range of alcohol-related problems, including poor class attendance, hangovers, trouble with authority, injuries and even fatalities, are commonly experienced by young adults engaging in heavy drinking (see Foster, Neighbors, & Young, Citation2013; Hingson, Citation2010; Hingson, Heeren, Winter, & Wechsler, Citation2005). Despite these findings, heavy alcohol consumption (AC) among young adults remains normative and is increasing in prevalence within university populations (Stewart & Devine, Citation2000). Stewart and Devine further state that studies have shown that about one-third of undergraduate students drink at a level that produces acute physical, psychological, social and academic problems (e.g. hangovers, lowered self-esteem, sexual misconduct, missing classes). Crawford and Novak (Citation2007) reported that students who perceive heavy drinking as a common activity at school are more likely to increase their levels of AC in order to gain social acceptance and avoid negative peer evaluations. Despite having specific policies designed to reduce students’ levels of consumption, binge drinking remains a frequent recurrence and is escalating (Crawford & Novak, Citation2007).

Previous research (see Baer, Citation1994; Critchlow, Citation1987; Darkes & Goldman, Citation1993; Evans & Dunn, Citation1995; Stacy, Widaman, & Marlatt, Citation1990) has identified a number of specific factors associated with heavy drinking, including demographic characteristics (gender and fraternity/sorority membership); descriptive and injunctive social norms; enhancement, social, coping and conformity drinking motives, expectancies and tendencies; and subjective evaluations of positive and negative alcohol effects. Surprisingly little research has evaluated the relative contribution of different factors in predicting AC and related problems as well as the direct impact of these constructs on binge-drinking consequences in a systematic manner (Neighbors, Lee, Lewis, Fossos, & Larimer, Citation2007; Turrisi, Wiersma, & Hughes, Citation2000).

Hall, Holmqvist, Simon, and Sherry (Citation2004) define risky sexual behaviour in terms of the behaviour itself, as well as the nature of the relationship between partners. Simply put, it can take several forms, ranging from acquiring a large number of sexual partners, to engaging in risky sexual activities and sexual intercourse under the influence of substances such as cocaine or alcohol (Hall et al., Citation2004). Risky sexual behaviour is identified as the second highest risk factor for harm in high mortality developing countries and constitutes 10.2% of the global burden of disease (Rehm & Room, Citation2003, as cited in Morojele et al., Citation2006). Globally there are an estimated 357 million new cases of STIs each year (WHO, Citation2016), with the highest rates among 20–24 year olds (Karl & Gabriele, Citation2005). Young adults are vulnerable for a number of reasons: their tendency to have multiple sexual partners (concurrent or sequential) as well as difficulty accessing effective STD prevention services (Charnigo et al., Citation2013); unprotected sexual intercourse (Gullete & Lyons, Citation2006; Khasakhala & Mturi, Citation2008); social, economic and contextual settings (Khasakhala & Mturi, Citation2008); sexual debut for most people occurs during their teenage years (Khasakhala & Mturi, Citation2008); the urge to have sex and curiosity play a role in risky behaviour but to name a few (Caron, Davis, Wynn, & Roberts, Citation1992; Keeling, Citation1995; Mickler, Citation1993; Okafor & Obi, Citation2005; Sells & Blum, Citation1996). Simultaneously, there has been a marked increase in the unwanted personal and social consequences associated with these behaviours such as higher prevalence of STDs, unintended pregnancies, school dropouts and heightened demands on the health and human service agencies (Langer, Warheit, & McDonald, Citation2001)

As reported by Langer et al. (Citation2001), these negative social and personal consequences associated with these changes in sexual attitudes and behaviours have attracted the interest of researchers and scholars from a variety of disciplines. Researchers collectively have examined the impact of biological and psychological predispositions as well as elements derived from our social and cultural environments (Langer et al., Citation2001). These include psychosocial variables (e.g. norms, attitudes and self-efficacy) as well as personality traits such as sensation seeking and impulsivity (Charnigo et al., Citation2013; Hoyle, Fejfar, & Miller, Citation2000; Noar, Zimmerman, Palmgreen, Lustria, & Horosewski, Citation2006).

As Cooper (Citation2002) noted, “the relationship between Alcohol use and risky sexual behaviour appears to be both complex and highly circumscribed” (p. 115), varying with characteristics of the individual drinker and the sexual situation. Although some multiple-event studies have supported the hypothesis that AC increases the likelihood of engaging in risky sexual behaviour, the findings are mixed (Cooper, Peirce, & Huselid, Citation1994; Graves & Hines, Citation1997; Morrison et al., Citation2003; Testa & Collins, Citation1997). Some authors point to an interplay between individual and environmental factors reflecting a cyclical and mutual dynamic of the individual influencing or being influenced by their environment (Choquet, Citation2004; Clapp, Segars, & Voas, Citation2002, Citation2008; DeJong et al., Citation2006; Harford, Citation1979; Jessor, Citation1998; Wechsler et al., Citation2002). Other authors have found stronger results when the outcome measure was number of casual sexual partners than when it was frequency of condom use (Cooper, Citation2002). Graves and Hines (Citation1997) found that AC was more common in sexual events that involved partners known for a short period of time; however, results regarding the relationship between AC and condom use were inconsistent. The interrelationships between partner type, intoxication and condom use make it difficult to disentangle alcohol’s role in unprotected sex (Abby, Parkhill, Buck, & Saenz, Citation2007). Although alcohol researchers focus on alcohol’s role in risky sexual behaviour, many theories of health behaviour have been applied to sexual risk taking and STD and HIV prevention (Albarracin et al., Citation2005).

Prior literature focused on adolescents, while less is known about how associations between substance use and risky sexual behaviour may change across young adulthood. The transition to adulthood is marked by dramatic increases in freedoms and responsibilities that occur at the same time that an individual’s ability to self-regulate is still emerging (King, Nguyen, Kosterman, Bailey, & Hawkins, Citation2012). However, how the associations between substance use disorders and risky sexual behaviours unfold across young adulthood remains unclear. (King et al., Citation2012). Despite the strong link between alcohol use and risky sexual behaviour, researchers have not adequately explored this relationship among young adults. The studies that have been conducted focused primarily on adolescents in formal educational settings (Cooper, Citation2002; Flisher et al., Citation1996 cited in Pithey & Morojele, Citation2002), clinic-based populations receiving treatment for STIs and HIV (Kalichman, Simbayi, Cain, & Jooste, Citation2007). It is important to note that the majority of studies that have linked alcohol use and risky sexual behaviour have been carried out in the developed world and among high school or college students (Khasakhala & Mturi, Citation2008). In a study conducted by Griffin et al. (Citation2012), they found that these behaviours peak during the early to mid-twenties as young people live more independently and autonomously from their family of origin, enjoy new freedoms such as legal drinking and the ability to enter bars and nightclubs, and have increased opportunities for sexual and romantic relationships. With statistics suggesting that the age group of 18–25 years is most vulnerable in terms of abusing alcohol (South African Community Epidemiology Network on Drug Use [SACENDU], Citation2011), it is imperative to explore the link between alcohol use and risky sexual behaviour in this cohort. This would contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of the relationship between alcohol use and risky sexual behaviour as suggested by Adams et al. (Citation2014).

1.1. Rationale

Within the literature, there is a well-established relationship between alcohol use and risky sexual behaviour (Adams et al., Citation2014; Campbell et al., Citation2002; Fritz et al., Citation2002; Mbulaiteye et al., Citation2000; Weiser et al., Citation2006). This relationship has emerged as a major health concern especially among young adults between the ages of 18–25 (Morojele et al., Citation2004; SACENDU, Citation2011). Freeman and Parry (Citation2006) have identified three different but related explanations to account for the relationship, namely social, biological and individual. Although these explanations and the associated factors have been well explored in the literature, there is currently no empirical initiative that has shown how these factors holistically interact with each other within the alcohol use and risky sexual behaviour relationship. The current study hopes to contribute in this regard by systematically reviewing the literature with the ultimate aim of informing future studies. It is anticipated that this would contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of the factors influencing the relationship between alcohol use and risky sexual behaviour among young adults and better inform intervention strategies.

1.2. Aim

The aim of the systematic review is to review and synthesise existing literature on the factor that influence the relationship between alcohol use and risky sexual behaviour among young adults (18–24 years old).

2. Method

We performed a systematic review of published studies since 2000 to identify the factors influencing the relationship between alcohol use and risky sexual behaviour among young people (age 18–24 years). The findings of this review will provide evidence-based knowledge critical for addressing the aim and specific objectives.

2.1. Review question

What factors influence the relationship between alcohol use and risky sexual behaviour among young adults?

2.2. Article search

Various resources, published in English from the year 2000 to present, were consulted for the review. Based on the nature of the topic, ScienceDirect and EBSCOhost were the main sources for the search. Databases within EBSCOhost included PsycARTICLES, SocINDEX, and Academic Search Complete. Once the articles had been appraised, manual searching of reference lists then took place. An initial review of relevant literature was conducted to identify key studies in the field. The following keywords formed part of the initial search within the above-mentioned databases: prevalence, alcohol consumption, risky sexual behaviour, alcohol use and risky sexual behaviour, participants, risk and protective factors, extraneous factors, at-risk behaviour and risk-taking behaviour. Within the searches that were initially conducted, it was found that the initial keywords did not yield the expected number of studies pertaining to the topic or no results were yielded. It was therefore decided to use the following terms: alcohol consumption, risky sexual behaviour, young people, young adults, risk and protective factors, contributing factors and influences.

2.3. Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Included studies were original English-language research articles published in peer-reviewed literature which reported on both quantitative and qualitative studies that focused on the factors impacting on the relationship between alcohol use and risky sexual behaviour among young people. The review did not attempt to categorise studies in terms of these two methods of research, but instead to provide a comprehensive picture of studies exploring the factors contributing to alcohol use and risky sexual behaviour. The review included both males and females between the ages of 18–24 years. Any racial, ethnic, cultural or religious groups were eligible for inclusion, regardless of geographic region. Articles pertaining to sexual violence, sexual coercion, intimate partner violence, HIV/AIDS and alcohol use disorders were not included in the review as there has been a paucity of research conducted to adequately addressed the extraneous factors contributing to the relationship between alcohol use and risky sexual behaviour (Morojele et al., Citation2006; Scott-Sheldon et al., Citation2012). Furthermore, studies focusing on age groups other than young adults and studies focusing on substance use in general were also excluded from the review.

2.4. Quality assessment

Study quality assessment is relevant to every step of a review. The assessment is crucial in evaluating the strengths, weaknesses and benefits of the assumptions and conclusions made in the study, as well as exploring heterogeneity and informing decisions regarding suitability of meta-analysis. In addition, they help assess the strength of inferences and make recommendations for future research. The selection of studies to be included in the review was thus assessed by utilising an adapted version of the Evaluation Tool for Qualitative Studies and The Evaluation Tool for Quantitative Research Studies (Long, Godfrey, Randall, Brettle, & Grant, Citation2002; Long & Godfrey, Citation2004).

2.5. Data extraction

Using the template in Table (Appendix), data was extracted at various stages, namely assessment of eligibility, assessment of quality, assessment of study characteristics and extraction of study findings. The table utilised for data extraction has been formatted to extract data specifically relevant to the research question, which includes the study authors, aim, sample size, participant characteristics, research design, outcomes, themes and self-concept domain.

Table 1. Type of research article

Table 2. Thematic domains

Table 3. Personality influences on alcohol consumption and risky sexual behaviour

Table 4. Social determinants of alcohol consumption and risky sexual behaviour

Table 5. Interpersonal factors related to alcohol consumption and risky sexual behaviour

2.6. Data synthesis

Data was summarised by means of tabulation of study characteristics, quality and effects as well as statistically if they are sufficiently similar and if they are of adequate quality to explore differences between studies and combining their effects (meta-analysis). The Textual Narrative Analysis approach as proposed by Lucas, Arai, Baird, and Roberts (Citation2007) was utilised. This method synthesises the studies used for review by study characteristics, context, quality and findings that are reported on. Structured summaries were then developed, expanding on and illuminating the context of the extracted data. This method was utilised as this approach typically groups studies into more homogenous groups, synthesising different types of research evidence and making explicit the diversity in study designs and contexts (Lucas et al., Citation2007).

3. Results

The aim of the systematic review is to review and synthesise existing literature on the factors that impact on the relationship between alcohol use and risky sexual behaviour among young adults (18–24 years old). The results of the systematic review are structured as follows: type of research, scope and focus of research, context of the studies, quality (content and method of the studies), age cohort, theory and findings, as proposed by Lucas et al. (Citation2007) in the Textual Narrative Analysis. A detailed summary of the final search procedure will be outlined below followed by a comprehensive explanation of the findings.

3.1. Article search procedure

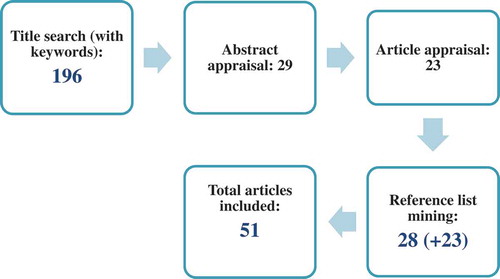

The keyword search yielded a total of 4,149 articles with 196 titles identified as relevant and were included for the abstract appraisal. The 147 articles that were excluded did not meet the inclusion criteria as they focused on other substances, HIV/AIDS-related cases, intimate partner violence and other age groups. Of the 196 abstracts, 29 were included for full-text appraisal. After a full-text appraisal, only 23 articles were included in the review. Based on reference list mining of the included articles, an additional 28 articles were identified as relevant for full-text appraisal. This process is outlined in Figure .

3.1.1. Type of research

The 51 articles included in the review can broadly be categorised into two types, that is, empirical work and review articles on alcohol use and risky sexual behaviour. Forty-five articles were classified as empirical articles utilising both qualitative and quantitative methods, as well as longitudinal studies with various age cohorts of young people ranging from children in school, adolescents in high school, college and university students, employed and unemployed youth, drinkers and non-drinkers. Additionally, six of the articles were review articles, consisting of literature reviews and systematic reviews focusing on various aspects of the relationship between alcohol use and risky sexual behaviour, such as the nature of the relationship, the motivations for engaging, and risk and protective factors.

3.1.2. Scope and focus of research

The research focus of the 45 studies in the review can generally be divided into three thematic domains, namely

Personality influences on alcohol use and risky sexual behaviour.

Social determinants of alcohol use and risky sexual behaviour.

Interpersonal factors related to alcohol use and risky sexual behaviour (see Table ).

These domains will be discussed in greater detail below.

3.2. Thematic domains

3.2.1. Personality influences on alcohol use and risky sexual behaviour

Studies in this domain focused on how personality traits influence their motivation to engage in risky alcohol use, risky sexual behaviour and/or the combination of the two. More specifically the articles focused on concepts like, self-efficacy, self-regulation, impulsivity, self-esteem, self-awareness, self-consciousness, sensation seeking but to name a few. This domain included 14 studies. Using Textual Narrative Analysis as a guide, it is discussed specifically in terms of (1) content, (2) age cohort, (3) context, (4) method, and (5) theory.

3.2.1.1. Content

The content and specific focus of the research studies in this domain ranged from elucidating the joint contribution of sensation seeking and impulsivity to decision-making to risk behaviours (Charnigo et al., Citation2013), evaluating self-consciousness, self-awareness, drinking identity, sensation seeking, self-esteem, as a moderator or contributor to risky alcohol use and subsequent risky sexual behaviour (Gullete & Lyons, Citation2006; Miller et al., Citation2003). Studies (Quinn & Fromme, Citation2010) also focused on self-regulation as buffering risk associated with alcohol use and as a protective factor to heavy drinking and unprotected sex. Other studies focused specifically on gender differences (Morojele et al., Citation2006), individual competencies (Stuewig et al., Citation2015), distinct facets of impulsivity and its contribution to alcohol use outcomes (Shin, Hong, & Jeon, Citation2012), examining restraint and temptation (Rinker & Neighbors, Citation2013), and drinking refusal self-efficacy (DRSE) (Oei & Morawska, Citation2004).

3.2.1.2. Age cohort

The review of literature showed that studies in this research area focused predominantly on young adults between the ages of 17 and 26 years. Two longitudinal studies focused on a specific cohort at two points in their lives, one focused on a mean age of 14.6 years and the second point was at a mean age of 22.8 (Griffin et al., Citation2012), the second study’s first point was at age 10 − 12 years and the second point was at 18 − 21 years (Stuewig et al., Citation2015).

3.1.2.3. Context

The context of the research studies which focused on alcohol use and risky sexual behaviour among young adults were conducted primarily in various states in the US, specifically various states in the US. Studies were predominantly conducted amongst university students in both the private and public sectors. Studies were also conducted in both low-income communities and middle-income communities.

3.1.2.4. Method

The majority of the studies utilised quantitative methods (n = 9 of 10) with most utilising self-reported questionnaires or computer or online-based surveys. Three studies were longitudinal studies that each had two contact points with individuals that reported on how behaviours at point one could be possible predictors for behaviour at point two (Griffin et al., Citation2012; Quinn & Fromme, Citation2010; Stuewig et al., Citation2015). All studies (n = 9) were generally descriptive studies that utilised correlation analysis and one utilising structural equation model (Murry, Simons, Simons, & Gibbons, Citation2013). The one review study focused on key constructs of alcohol expectancies (AEs) and DRSE to explain the acquisition and maintenance of binge drinking.

3.1.2.5. Theory

There were only 5 of the 10 studies which used a theoretical framework to guide their study. Four of the eight studies utilised the Five-Factor Model of Personality (Charnigo et al., Citation2013; Miller et al., Citation2003; Shin et al., Citation2012; Stewart & Devine, Citation2000) to synthesise and interpret the findings of their study. Other studies utilised Transtheoretcal Model of Behavioral Change (Gullete & Lyons, Citation2006) and Alcohol Expectancy Theory (Oei & Morawska, Citation2004). One study utilised the theory behind self-regulation and sensation seeking to synthesise and explain the findings (Table ) (Quinn & Fromme, Citation2010).

3.2.2. Social determinants of alcohol use and risky sexual behaviour

The studies in this domain explored the social, contextual and environmental factors impacting on the relationship between alcohol use and risky sexual behaviour. More specifically the articles focusing on social aspects including social norms, motives assumptions and beliefs in the social context. Contextual aspects focused on the context in which alcohol use and risky sexual behaviour takes place. Lastly environmental aspects focus on the historical construction of communities.

3.2.2.1. Content

The content and specific focus of the research studies in this domain consisted of an array of focal areas including assumptions of environmental approaches to alcohol use (Clapp et al., Citation2002), normative perceptions (Lewis, Patrick, Mittmann, & Kaysen, Citation2014), social norms, demographics, drinking motives and AEs in predicting AC and related problems (Neighbors et al., Citation2007), the nature of the relation among drinking beliefs, drinking tendencies, perceived sexual control (Walsh et al., Citation2013), behavioural consequences (Turrisi et al., Citation2000) and effects of alcohol use on condom use (Abbey, Saenz, & Buck, Citation2005). Further studies explore alcohol use and risky sexual behaviour (Abby et al., Citation2007; Orchowski & Barnett, Citation2012; Seth, Wingood, DiClemente, & Robinson, Citation2011). Contextual aspects include the extent to which Spring Break drinking and sexual behaviours are related (Patrick, Citation2013), rates of risky sexual behaviour among women bar drinkers (Parks, Hsieh, Collins, Levonyan-Radloff, & King, Citation2008) and reducing sexual risk behaviours among university students in particular (Connor, Psutka, Cousins, Gray, & Kypri, Citation2013). Further studies focus on identifying patterns of alcohol use behaviours and AEs among women (Stappenbeck et al., Citation2013), the relationship between binge drinking, “reflection impulsivity” alcohol-related expectancies and unplanned sexual behaviour in a sample of young social drinkers (Townsend et al., Citation2011). Environmental aspects include studies focusing on the extent of the current alcohol problem as well as a historical perspective (Vicary & Karshin, Citation2002), how alcohol misuse increases the occurrence of sexual risk behaviour in South African communities (Pithey & Morojele, Citation2002) and describing an example of the use of latent variable modelling to create measures of complex phenotypes and environments that illustrate the utility of the general versus specific conceptualisation (Bailey, Hill, Meacham, Young, & Hawkins, Citation2011).

3.2.2.2. Age cohort

The review of literature showed that studies in this research area focused predominantly on young adults between the ages of 17 and 35 years. One longitudinal study focused on fifth graders at its first point of contact and adults were later retained at 24 years old (Bailey et al., Citation2011).

3.2.2.3. Context

The context of the research studies focused young adults in relation to social, contextual and environmental aspects of alcohol use and risky sexual behaviour primarily in countries outside of South Africa, specifically various states in the US. Studies were predominantly conducted in schools, colleges and universities in both the private and public sectors. Studies were also conducted in both low-income communities and middle-income communities. Two studies were conducted in South Africa, one in an impoverished community on the Cape Flats (Abby et al., Citation2007) and the other in broader South African communities (Pithey & Morojele, Citation2002).

3.2.2.4. Method

It was found that most studies in this domain utilised quantitative methods (n = 16). Various designs and data analysis techniques were used in these studies. The research designs used included correlational designs, cross-sectional and longitudinal designs. Many of these quantitative studies used independent and correlational techniques such as multiple, hierarchical and logistic regression (Abbey et al., Citation2005; Abby et al., Citation2007; Bogg & Finn, Citation2009; Connor et al., Citation2013; Lewis et al., Citation2014; Neighbors et al., Citation2007; Orchowski & Barnett, Citation2012; Parks et al., Citation2008; Seth et al., Citation2011; Turrisi et al., Citation2000). Two of the studies made use of latent analysis (Stappenbeck et al., Citation2013; Townsend et al., Citation2011), and one study made use of path modelling procedures (Walsh et al., Citation2013). Three of the articles in this domain were review articles (Pithey & Morojele, Citation2002; Vicary & Karshin, Citation2002).

3.2.2.5. Theory

There were only three studies which used a theoretical framework to guide their study. These studies all utilised different theories to guide their study. Theories considered problem behaviour theory (Murry et al., Citation2013) and traumagenic dynamics theory (Walsh et al., Citation2013). Another study utilised a conceptual model, more specifically family and economic stress theories and problem behaviour theory (Murry et al., Citation2013). Lastly, Oei and Jardim (Citation2007) utilised the theory behind AEs and drink refusal self-efficacy to shape and guide their study (Table ).

3.2.3. Interpersonal factors related to alcohol use and risky sexual behaviour

The studies in this domain focused on the family, peers, risk and protective factors, and personal attributes. The articles that focused broadly on the family and, in particular, parental and family influence and parental and family beliefs. Peer aspects focused on the relationship between young adults and their peers. These factors included perceived care of friends, role modelling, and perceived alcohol use and sexual behaviour of friends. Personal attributes refer to attitudes, race, gender, genetics and religiosity. Lastly, risk and protective factors also emerged in this domain. Using Textual Narrative Analysis as a guide, it is discussed specifically in terms of content, age cohort, context and method, and theory.

3.2.3.1. Content

The content and specific focus of the research studies in this domain broadly considered the relationship between alcohol use and risky sexual behaviour to more individual, family and peer aspects. More specifically, exploring the relationship between alcohol use and risky sexual behaviour as a phenomenon (Adams et al., Citation2014; Cooper, Citation2002, Citation2006), associations across motivations for engaging in alcohol use and risky sexual behaviour (Patrick & Maggs, Citation2010), to illuminating our understanding of sexual behaviour (Marston & King, Citation2006), risk and protective factors (Kogan et al., Citation2010; Langer et al., Citation2001; Voisin, Hotton, Tan, & DiClemete, Citation2013), and protective behavioural strategies (LaBrie, Lac, Kenney, & Mirza, Citation2011). Individual aspects such as gender and psychological risk and protective factors (Park & Grant, Citation2005), cognitive and affective attitudes, personal normative beliefs, social determinants and expectations (Sonmez et al., Citation2006) and the impact of partner type (Brown & Vanable, Citation2007). Family relationships focused on parental mediation and critical thinking (Radanielina-Hita, Citation2015). Peer relationships, with specific reference social relationships (Townshend, Kambouropoulos, Griffin, Hunt, & Milani, Citation2014), perceived awareness and caring, or know or care about student’s behaviour (Wetherill, Neal, & Fromme, Citation2010).

3.2.3.2. Age cohort

The review of literature showed that studies in this research area focused predominantly on young adults between the ages of 15 and 35 years. One mixed-method study focused on 18–62 year olds (Townshend et al., Citation2014).

3.2.3.3. Context

The context of the research studies focused on young adults in relation to family, peers and individual aspects relating to alcohol use and risky sexual behaviour primarily in countries outside of South Africa. Studies were predominantly conducted in colleges and universities in both the private and public sectors. Studies were also conducted in both low-income communities and middle-income communities. Two studies were conducted in South Africa, one in an impoverished community on the Cape Flats (Adams et al., Citation2014) and the other in one of the poorest suburbs in South Africa, average household income is less than R1500 pm and unemployment is high (Townshend et al., Citation2014). Four reviews were conducted within this domain focusing on published articles worldwide (Cooper, Citation2002, Citation2006; Marston & King, Citation2006).

3.2.3.4. Method

It was found that most studies in this domain utilised quantitative methods (n = 15). Various designs and data analysis techniques were used in these studies. The designs ranged from correlation designs, to survey designs, and cross-sectional and longitudinal designs. Data analysis techniques used ranged from structural equation modelling (Radanielina-Hita, Citation2015; Schraufnagel, Davis, George, & Norris, Citation2010; Wayment & Aronson, Citation2002) and generalised estimating equations (Voisin et al., Citation2013; Wetherill et al., Citation2010), to various types of regression (Brown & Vanable, Citation2007; Kogan et al., Citation2010; Langer et al., Citation2001; Sonmez et al., Citation2006). Two studies used structural correlational analysis (Adams et al., Citation2014; Park & Grant, Citation2005), while one study utilised latent profile analysis (Patrick & Maggs), and another utilised path analysis (Walsh, Latzman, & Latzman, Citation2014). It was noted that only one study was a mixed-method study that utilised regression analysis for data analysis (Townshend et al., Citation2014). Four reviews were conducted, three being literature reviews (Cooper, Citation2002, Citation2006) and one a systematic review (Marston & King, Citation2006).

3.2.3.5. Theory

In total, 10 of the 21 studies used a theoretical framework to guide their study. Theories comprised of Ecological Systems Theory (Kogan et al., Citation2010; Voisin et al., Citation2013) and Myotopia Theory (Brown & Vanable, Citation2007; Cooper, Citation2002). Other theories included Message Interpretation Model (Radanielina-Hita, Citation2015), Health Belief Model (Wayment & Aronson, Citation2002) and The Theory of Interpersonal Behavior (Table ) (Sonmez et al., Citation2006).

4. Discussion

While the relationship between alcohol use and risky sexual behaviour is well-established in the literature (see Adams et al., Citation2014; Campbell et al., Citation2002; Fritz et al., Citation2002; Mbulaiteye et al., Citation2000; Weiser et al., Citation2006), there are few empirical studies that demonstrate and unpack the nature of this relationship (see Cook & Clark, Citation2005; Morojele et al., Citation2006; Muchimba, Haberstick, Corley, & McQueen, Citation2013; Scott-Sheldon et al., Citation2012). Research shows that young adults engage in heavy drinking and experience a range of alcohol-related problems, including poor class attendance, hangovers and trouble with authorities, injuries and even fatalities (Foster et al., Citation2013; Hingson, Citation2010; Hingson et al., Citation2005; Wechsler, Davenport, Dowdall, & Moeykens, Citation1994; Wechsler, Lee, Kuo, & Lee, Citation2000). The aim of the systematic review is to review and synthesise previous literature to discuss factors identified in the literature that influence the relationship between alcohol use and risky sexual behaviour. Thus, the articles in the current systematic review focused on literature highlighting these factors. The key factors influencing the relationship between alcohol use and risky sexual behaviour that emerged from the review were personality incluences, social determinants and interpersonal factors. Yet, determining alcohol’s precise role in sexual risk taking has proven to be difficult. Past research has produced mixed results, depending on characteristics of individuals, their partners and the situation, as well as how the link between alcohol use and sexual behaviour was assessed (Abby et al., Citation2007).

Patrick and Maggs (Citation2010) suggested that the links between motivations for alcohol use and sexual behaviours are not well understood. However, within the literature the contributing factors for each overlap significantly, strengthening the relationship between the two concepts. While personality influences such as self-efficacy, self-regulation, self-awareness, sensation-seeking and so forth are important to understanding and determining drinking patterns, it has been suggested that dosage is an important aspect of alcohol use which is largely under the individuals’ control. However, there is evidence that frequency of drinking occasions may be greatly influenced by social factors (Vogel-Sprott, Citation1974). For example, university or college students with high levels of sensation seeking may be at especially high risk to begin or escalate heavy drinking. However, articles reviewed to a large extent employed a cross-sectional research design, thus making it impossible to examine changes over time and, therefore, difficult to draw solid conclusions. The major implication for the studies that utilised longitudinal designs is the age periods at which data was collected. Collecting data before adolescence and then after does not make allowance for the period in between. Future longitudinal examination of the aetiology of alcohol use will allow for better understanding of the window of influence for specific risk and protective factors (Rutledge & Sher, Citation2001), and using multilevel modelling approaches would allow researchers to evaluate several predictors at once in order to determine their individual and combined effects (Kraemer et al., Citation2001).

Studies exploring the social, contextual and environmental factors conducted research on very similar populations, namely college students or university students predominantly from First World countries (the US, New Zealand and Australia). While only 4 out of 20 studies under this theme focused on developing countries (South Africa and Kenya). Therefore, the above results may be limited to the specific context of North American, New Zealand and Australian young adults’ patterns of risky behaviour. Literature reviewed found that social norms, social context and social beliefs, as well as the broader environment, contribute to alcohol use and risky sexual behaviour. Thus, studies from other countries are needed in order to acquire knowledge on the significance of the cultural influences of drinking motives.

Literature reviewed focusing on factors relating interpersonal aspects concentrated on how the individual interacts with various other parts of their lives such as the personal attributes (age, race, gender, biological make up and religiosity), family, peers, romantic relationships, and broader risk and protective factors. The studies additionally highlight the impact of one’s sociopolitical and historical situation shape decisions or lifestyles today (Cooper, Citation2006). Cooper (Citation2006) further states that the belief that alcohol causally disinhibits sexual behaviour is firmly ingrained in our culture. Most people believe that drinking increases the likelihood of sexual activity, enhances sexual experience, and promotes riskier sexual behaviour (Cooper, Citation2006). Countries with an oppressive history have been shown to have a negative impact on an individual’s healthy self-development, and more broadly on the development of the environment in which the individual resides. This is evident in studies conducted in South Africa (Adams et al., Citation2014; Townshend et al., Citation2014) and the US (amongst various ethnicities such as African-Americans, Hispanic and Asians) (Brown & Vanable, Citation2007; Kogan et al., Citation2010; Langer et al., Citation2001; Park & Grant, Citation2005; Voisin et al., Citation2013). This is consistent with previous research that states that while there is evidence that there is an inverse relationship between risky behaviours and age (Ajayi, Marangu, Miller, & Paxman, Citation1991; Akwara, Madise, & Hinde, Citation2003; Chassin, Pitts, & Prost, Citation2002; Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, & Schulenberg, Citation2004; Kiragu & Zabin, Citation1995; O’Neill, Parra, & Sher, Citation2001; Ochollo-Ayayo & Schwarz, Citation1991; Schulenberg, O’Malley, Bachman, Wadsworth, & Johnston, Citation1996), it is an unlikely outcome in communities characterised by poverty and lack of resources and access to educational and employment opportunities. These factors, with a historical and political genesis, are mutually influencing, resulting in a recurring process of risky behaviour and impoverishment. Along with these external factors, individual factors such as perceptions of self-identity, social identity, self-efficacy, sense of belonging and hope for the future play a significant role in contributing towards risky behaviours (Adams et al., Citation2014).

Despite the large body of theory and research that supports alcohol’s role in risky sexual behaviour, understanding the nature of this relationship has been more challenging than originally anticipated (for reviews, see Cooper, Citation2002; Halpern-Felsher, Millstein, & Ellen, Citation1996; Weinhardt & Carey, Citation2000). A possible contributing factor is that there were very few studies which utilised theoretical frameworks to structure the studies. The theoretical frameworks utilised attempted to summarise and make sense of individual and social factors contributing to alcohol use and risky sexual behaviour. These frameworks were used to understand the behaviour and help account for underlying mechanisms of the specific cohort’s drinking and may ultimately explain points for more comprehensive intervention development and enhancement. Essentially, there is no one theory to explain the relationship between alcohol use and risky sexual behaviour. However, for an intervention to be successful a theory is needed to explain the relationship, understand the contributing factors and the patterns in the relationship and how it changes. Additionally, the use of theoretically based questionnaires with well-defined items is particularly important since the diversity of content of research in this field restricts the comparability of findings and makes conclusions difficult (Kuntsche, Knibbe, Gmel, & Engels, Citation2005).

According to Kuntsche et al. (Citation2005), an explanation for these inconsistent results could be that motives affect drinking only in the onset phase and not the continuation to drink and indulge in risky sexual behaviour. From the research reviewed, there is consensus that internally caused motives such as coping, sense of belonging and self-efficacy are strongly related with personality traits are more consistently related to alcohol use across drinking situations. However, since there is a lack of longitudinal evidence it is nearly impossible to determine the long-term effects of different drinking motives on different alcohol-relatedoutcomes in different age groups within different contexts (Kuntsche et al., Citation2005).

4.1. Conclusions and Recommendations

Whilst there has been an increase in research attempting to ascertain and determine the key factors that make the relationship between the alcohol use and risky sexual behaviour significant, very few studies focused directly on the factors mediating and moderating this relationship. In spite of this, the studies and reviews which form part of this systematic review provide key insights into factors impacting on alcohol use and risky sexual behaviour. Further systematic enquiry and qualitative exploration at a primary level will allow for an increased comprehension as to how these factors contribute specifically to the relationship between alcohol use and risky sexual behaviour as some young adults may engage in risky sexual behaviour but not necessarily engage in alcohol use, or vice versa. Many of these studies reviewed were also quantitative studies; thus, an in-depth understanding, across time, will allow for a greater understanding of these factors. As Cooper (Citation2006) expressed, the relationship between alcohol use and risky sexual behaviour is complex and cannot be explained by a single mechanism, but instead reflects multiple underlying causal and non-causal processes. Moreover, even the causal portion of this relationship is not apparent as a main effect but as an interaction. Therefore, there is a need to qualitatively explore young people’s understandings, perceptions and motivations to engaging in alcohol use and risky sexual behaviour. While these findings will be context-specific, this will be the foundation for studies that aim to quantitatively understand this relationship. Furthermore, there remains a need for research among young adults as a whole and not exclusively among young adults in school, colleges, university or clinic/treatment setting. Other gaps in the literature point to the need for research across diverse socio-economic group.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Cassandra Wagenaar

Cassandra Wagenaar is currently a PhD candidate in the Department of Psychology at the University of the Western Cape. Her research interests are in the broad area of adolescent and youth development with a specific focus on substance use and risky sexual behaviour.

Maria Florence

Dr. Maria Florence is currently a senior lecturer in the Psychology Department at the University of the Western Cape. Her research interests include measurement design and validation, youth risk behaviour and substance use in low socio-economic status communities.

Sabirah Adams

Dr. Sabirah Adams is a research psychologist based in the Department of Psychology at the University of the Western Cape. Her research interests include environmental psychology, child well-being, children’s subjective well-being and children’s geographies.

Shazly Savahl

Prof. Shazly Savahl is research psychologist based in the Department of Psychology at the University of the Western Cape. His research interests include child well-being, children’s subjective well-being and quality-of-life research.

References

- Abbey, A., Saenz, C., & Buck, P. (2005). The cumulative effects of acute AC, individual differences, and situational perceptions on sexual decision making. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 66, 82–90. doi:10.15288/jsa.2005.66.82

- Abby, A., Parkhill, M., Buck, P., & Saenz, C. (2007). Condom use with a casual partner: What distinguishes college students’ use when intoxicated? Psychology of Addictive Behaviours, 21(1), 76–83. doi:10.1037/0893-164X.21.1.76

- Adams, S., Savahl, S., Carels, C., Isaacs, S., Brown, Q., Malinga, M., … Zozulya, M. (2014). AC and risky sexual behaviour amongst young adults in a low-income community in Cape Town. Journal of Substance Use, 19(1–2), 118–124. doi:10.3109/14659891.2012.754059

- Ajayi, A., Marangu, L., Miller, J., & Paxman, J. (1991). Adolescent sexuality and fertility in Kenya: A survey of knowledge, perceptions, and practices. Studies in Family Planning, 22, 205–216. doi:10.2307/1966477

- Akwara, A. P., Madise, N. J., & Hinde, A. (2003). Perception of risk of HIV/AIDS and sexual behaviour in Kenya. Journal of Biosocial Science, 35, 385–411. doi:10.1017/S0021932003003857

- Albarracin, D., Gillette, J. C., Earl, A. N., Glasman, L. R., Durantini, M. R., & Ho, M.-H. (2005). A test of major assumptions about behavior change: A comprehensive look at the effects of passive and active HIV-prevention interventions since the beginning of the epidemic. Psychological Bulletin, 131, 856–897. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.131.6.856

- APA. (2002). Developing adolescents: A reference for professionals. Washington, DC: American Psychological Society.

- Baer, J. S. (1994). Effects of college residence on perceived norms for AC: An examination of the first year in college. Psychology of Additive Behaviors, 8, 43–50. doi:10.1037/0893-164X.8.1.43

- Bailey, J., Hill, K., Meacham, M., Young, S., & Hawkins, J. (2011). Strategies for characterising complex phenotypes and environments: General and specific family environmental predictors of young adult tobacco dependence, alcohol use disorder, and co-occurring problem. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 118(2011), 444–451. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.05.002

- Bogg, T., & Finn, P. (2009). An ecologically based model of alcohol-consumption decision making: Evidence for the discrimination and predictive role of contextual reward and punishment information. Alcohol Drugs, 70, 446–457. doi:10.15288/jsad.2009.70.446

- Brown, J., & Vanable, P. (2007). Alcohol use, partner type, and risky sexual behaviour among college students: Findings from an event-level study. Addictive Behaviours, 32(2007), 2940–2952. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.06.011

- Campbell, C., Williams, B., & Gilgen, D. (2002). Is social capita a useful conceptual tool for exploring community level influences on HIV infection? An exploratory case study from South Africa. AIDS Care, 14(1), 41–54. doi:10.1080/09540120220097928

- Caron, S. L., Davis, C. M., Wynn, R. L., & Roberts, L. W. (1992). “America responds to AIDS”, but did college students? Differences between March 1987, and September 1988. AIDS Education Preview, 4(1),18-28.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2003). Guidelines for environmental infection control in health-care facilities: recommendations of cdc and the healthcare infection control practices advisory committee (HICPAC). MMWR, 52 (10): 1–48.

- Charnigo, R., Noar, S., Garnett, C., Crosby, R., Palmgreen, P., & Zimmerman, R. (2013). Sensation seeking and impulsivity: Combined association with risky sexual behaviour in a large sample of young adults. Journal of Sex Research, 50(5), 480–488. doi:10.1080/00224499.2011.652264

- Chassin, L., Pitts, S. C., & Prost, J. (2002). Binge drinking trajectories from adolescence to emerging adulthood in a high-risk sample: Predictors and substance abuse outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 70, 67–78.

- Choquet, M. (2004). Underage drinking: The epidemiological data. In a report commissioned by the International Centre for Alcohol Policies: What drives underage drinking? An International Analysis (pp. 14–24). Washington, DC: International Center for Alcohol Policies.

- Clapp, J., Segars, L., & Voas, R. (2002). A conceptual model of the alcohol environment of college students. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 5, 73–90. doi:10.1300/J137v05n01_05

- Clapp, J.D, Min, J.W, Shillington, A.M, Reed, M.B, & Croff, J.M. (2008). Person and environment predictors of blood alcohol concentrations: a multi-level study of college parties. alcoholism. Clinical and Experimental Research, 32(1), 100-7.

- Connor, J., Psutka, R., Cousins, K., Gray, A., & Kypri, K. (2013). Risky drinking, risky sex: A national study of New Zealand university students. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 37(11), 1971–1978. doi:10.1111/acer.12175

- Cook, R. L., & Clark, D. B. (2005). Is there an association between AC and sexually transmitted diseases? A systematic review. Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 32(3), 156–164. doi:10.1097/01.olq.0000151418.03899.97

- Cooper, M. (2006). Does drinking promote risky sexual behaviour? A complex answer to a simple question. Association for Psychological Science, 15(1), 19–23.

- Cooper, M. L. (2002). Alcohol use and risky sexual behavior among college students and youth: Evaluating the evidence. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, Supplement, 14, 101–117. doi:10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.101

- Cooper, M. L., & Orcutt, H. K. (2000). Alcohol use, condom use and partner type among heterosexual adolescents and young adults. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 61, 413–419. doi:10.15288/jsa.2000.61.413

- Cooper, M. L., Peirce, R. S., & Huselid, R. F. (1994). Substance use and sexual risk taking among black adolescents and white adolescents. Health Psychology, 13, 251–262. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.13.3.251

- Crawford, L. A., & Novak, K. B. (2007). Resisting peer pressure: Characteristics associated with other-self discrepancies in college students’ levels of AC. Journal of Alcohol and Drug Education, 51, 35–62.

- Critchlow, B. (1987). A utility analysis of drinking. Addictive Behaviors, 12, 269–273. doi:10.1016/0306-4603(87)90038-4

- Curtis, A. C. (2015). Defining Adolescence. Journal of Adolescent and Family Health, 7(2). Article 2. Retrieved from http://scholar.utc.edu/jafh/vol7/iss2/2

- Darkes, I., & Goldman, M. S. (1993). Expectancy challenge and drinking reduction: Experimental evidence for a mediational process. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 61, 344–353. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.61.2.344

- DeJong, W., Kessel, S. S., Gomberg, T. L., Murphy, M. J., Doerr, E. E., Simonsen, N. R., … Scribner, R. A. (2006). A multisite randomized trial of social norms marketing campaigns to reduce college student drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 67, 868–879. doi:10.15288/jsa.2006.67.868

- Evans, D. M., & Dunn, N. I. (1995). Alcohol expectancies, coping responses and self-efficacy judgments: A replication and extension of Cooper, Shapiro and Powers’ 1988 study in a college sample. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 56, 186–193. doi:10.15288/jsa.1995.56.186

- Flisher, AJ, Ziervogel, CF, Chalton, DO, Leger, PH, & Robertson, BA. (1996). Risk-taking behaviour of cape peninsula high-school students: part ix: evidence for a syndrome of adolescent risk behaviour. S Afr Med J, 86(9), 1090–3.

- Foster, D., & Neighbors, C. (2013). Self-consciousness as a moderator of the effect of social drinking motives on alcohol use. Addictive Behaviors, 38(2013), 1996–2002. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.01.011

- Foster, D. W., Neighbors, C., & Young, C. (2013). Drink refusal self-efficacy and implicit drinking identity: An evaluation of moderators of the relationship between self-awareness and drinking behavior. Addictive Behaviors. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.09.024

- Freeman, M., & Parry, C. (2006). Alcohol use literature review: Prepared for Soul City.

- Fritz, K. E., Woelk, G. B., Bassett, M. T., McFarland, W. C., Routh, J. A., Tobalwa, O., & Stall, R. D. (2002). The association between alcohol use, sexual risk behaviour, and HIV infection among men attending beer halls in Harare, Zimbabwe. AIDS and Behaviour, 6(3), 221–228. doi:10.1023/A:1019887707474

- Graves, K. L., & Hines, A. M. (1997). Ethnic differences in the association between alcohol and risky sexual behavior with a new partner: An event-based analysis. AIDS Education and Prevention, 9, 219–237.

- Griffin, K., Scheler, L., Acevedo, B., Grenard, J., & Botvin, G. (2012). Long-term effects of self-control on alcohol use and sexual behaviour among urban minority young women. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 9, 1–23. doi:10.3390/ijerph9010001

- Gullete, D., & Lyons, M. (2006). Sensation seeking, self-esteem, and unprotected sex in college students. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, 17(5), 23–31. doi:10.1016/j.jana.2006.07.001

- Hall, P. A., Holmqvist, B. A., Simon, B., & Sherry, M. A. (2004). Risky sexual behaviour: A psychological perspective for primary care clinicians. Topics in Advanced Practice Nursing (E Journal), 4(1), 1–6.

- Halpern-Felsher, B. L., Millstein, S. G., & Ellen, J. M. (1996). Relationship of alcohol use and risky sexual behavior: A review and analysis of findings. Journal of Adolescent Health, 19, 331–336. doi:10.1016/S1054-139X(96)00024-9

- Harford, T. C. (1979). Contextual drinking patterns among men and women. Curr Alcohol, 4, 287–296.

- Hingson, R., Heeren, T., Winter, M., & Wechsler, H. (2005). Magnitude of alcoholrelated mortality and morbidity among U.S. college students ages 18–24: Changes from 1998 to 2001. Annual Review Of Public Health, 26, 259 - 279.

- Hingson, R. W. (2010). Magnitude and prevention of college drinking and related problems. Alcohol Research & Health, 33(1–2), 45–54.

- Hoyle, R. H., Fejfar, M. C., & Miller, J. D. (2000). Personality and sexual risk taking: A quantitative review. Journal of Personality, 68, 1203–1231. doi:10.1111/1467-6494.00132

- Jessor, R. (Ed.). (1998). New perspectives on adolescent risk behaviour. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Johnston, L. D., O’Malley, P. M., Bachman, J. G., & Schulenberg, J. E. (2004). Monitoring the future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2003 VolumeII: College students and adults ages 19–45 (NIHPublication No.04-5508). Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse.

- Kalichman, S. C., Simbayi, L. C., Cain, D., & Jooste, S. (2007). Alcohol expectancies and risky drinking among men and women at high risk for HIV infection in Cape Town, South Africa. Addictive Behaviours, 32(10), 2304–2310. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.01.026

- Karl, D., & Gabriele, R. (2005). Sexually transmitted infections among adolescents: The need for adequate health services. Geneva: World Health Organisation.

- Keeling, R. P. (1995). HIV update. American College Health Association.

- Khasakhala, A., & Mturi, A. (2008). Factors associated with risky sexual behaviour of school youth in Kenya. Journal of Biosocial Science, 40(5), 641–653. doi:10.1017/S0021932007002647

- King, K., Nguyen, H., Kosterman, R., Bailey, J., & Hawkins, J. (2012). Co-occurrence of sexual risk behaviours and substance use across emerging adulthood: Evidence for state- and trait-level associations. Addiction, 107, 1288–1296. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.03792.x

- Kiragu, K., & Zabin, L. S. (1995). Contraceptive use among high school students in Kenya. International Family Planning Perspectives, 21(3), 108–113. doi:10.2307/2133184

- Kogan, S., Brody, G., Chen, Y., Grange, C., Slater, L., & DiClemente, R. (2010). Risk and protective factors for unprotected intercourse among rural african american young adults. Public Health Reports, 125, 709–717. doi:10.1177/003335491012500513

- Kraemer, H, Stice, E, Kazdin, A, Offord, D, & Kupfer, D. (2001). How do risk factors work together? mediators, moderators, and independent, overlapping, and proxy risk factors. Am J Psychiatry, 158(6), 848-56.

- Kuntsche, E., Knibbe, R., Gmel, G., & Engels, R. (2005). Why do young people drink? A review of drinking motives. Clinical Psychology Review, 25, 841–861. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2005.06.002

- LaBrie, J., Pedersen, E. R., Neighbors, C., & Hummer, J. F. (2008). The role of self consciousness in the experience of alcohol-related consequences among college students. Addictive Behaviors, 33, 812–820.

- LaBrie, J. W., Lac, A., Kenney, S. R., & Mirza, T. (2011). Protective behavioral strategies mediate the effect of drinking motives on alcohol use among heavy drinking college students: Gender and race differences. Addictive Behaviors, 36(4), 354–361. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.12.013

- Langer, L., Warheit, G., & McDonald, L. (2001). Correlates and predictors of risky sexual practices among a multi-racial/ethnic sample of university students. Social Behaviour and Personality, 29(2), 133–144. doi:10.2224/sbp.2001.29.2.133

- Leigh, B., & Stall, R. (1993). Substance use and risky sexual behavior for exposure to HIV. Issues in methodology, interpretation, and prevention. American Psychology, 48, 1035–1045. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.48.10.1035

- Lewis, M., Patrick, M., Mittmann, A., & Kaysen, D. (2014). Sex on the beach: The influence of social norms and trip companion on spring break sexual behaviour. Prevention Science, 15, 408–418. doi:10.1007/s11121-014-0460-8

- Littleton, H., Breikopf, C., & Berenson, A. (2007). Sexual risk behaviours: Relationships among women and potential mediators. Child Abuse and Neglect, 31(2007), 757–768. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.12.015

- Long, A. F., & Godfrey, M. (2004). An evaluation tool to assess the quality of qualitative research studies. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 2(7), 181–196. doi:10.1080/1364557032000045302

- Long, A. F., Godfrey, M., Randall, T., Brettle, A. J., & Grant, M. J. (2002). Developing evidence based social care policy and practice. Part 3: Feasibility of undertaking systematic reviews in social care. Leeds: Nuffield Institute for Health.

- Lucas, P. J., Arai, L., Baird, L. C., & Roberts, H. M. (2007). Worked examples of alternative methods for the synthesis of qualitative and quantitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 7(4), 1–7. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-7-4

- Marston, C., & King, E. (2006). Factors that shape young people’s sexual behaviour: A systematic review. The Lancet, 368, 1581–1586. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69662-1

- Mbulaiteye, S. M., Ruberantwari, A., Nakinyings, J. S., Carpenter, L. M., Kamali, A., & Whitworth, J. (2000). Alcohol and HIV: A study among sexually active adults in rural southwest Uganda. International Journal of Epidemiology, 29(9), 911–915. doi:10.1093/ije/29.5.911

- Mickler, S. E. (1993). Perceptions of vulnerability: Impact on AIDS-preventive behavior among college adolescents. AIDS Education and Prevention, 5, 43–53.

- Miller, J., Lynam, D., Zimmerman, R., Logan, T., Leukefeld, C., & Clayton, R. (2003). The utility of the Five Factor Model in understanding risky sexual behaviour. Personality and Individual Differences, 36(2004), 1611–1626. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2003.06.009

- Morojele, N., Kachieng’a, M., Mokoko, E., Nkoko, M., Parry, C., Nkowane, A., … Saxena, S. (2006). Alcohol use and sexual behaviour among risky drinkers and bar and shebeen patrons in Gauteng province, South Africa. Social Science & Medicine, 62(2006), 217–227. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.05.031

- Morojele, N. K., Kachieng’a, M. A., Mokoko, E., Nkoko, M. A., Moshia, K. M., Parry, C. D. H., … Saxena, S. (2004). The relationships between alcohol use and risky sexual behaviour among adults in a urban areas in Gauteng Province, South Africa. Parow: Medical Research Council.

- Morrison, D. M., Gilmore, M. R., Hoppe, M. J., Gaylord, J., Leigh, B. C., & Rainey, D. (2003). Adolescent drinking and sex: Findings from a daily diary study. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 35, 162–168. doi:10.1363/3516203

- Muchimba, M., Haberstick, B., Corley, R., & McQueen, M. (2013). Frequency of alcohol use in adolescence as a marker for subsequent sexual risk behavior in adulthood. Journal of Adolescent Health, 53(2), 215–221. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.02.005

- Murry, V., Simons, R., Simons, R., & Gibbons, F. (2013). Contributions of family environment and parenting processes to sexual risk and substance use of rural African American males: A 4-year longitudinal analysis. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 83(23), 299–309. doi:10.1111/ajop.12035

- Neighbors, C., Lee, C. M., Lewis, M. A., Fossos, N., & Larimer, M. E. (2007). Are social norms the best predictor of outcomes among heavy-drinking college students? Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 68, 556–565. doi:10.15288/jsad.2007.68.556

- Noar, S. M., Zimmerman, R. S., Palmgreen, P., Lustria, M., & Horosewski, M. L. (2006). Integrating personality and psychosocial theoretical approaches to understanding safer sexual behavior: Implications for message design. Health Communication, 19, 165–174. doi:10.1207/s15327027hc1902_8

- O’Neill, S. E., Parra, G. R., & Sher, K. J. (2001). Clinical relevance of heavy drinking during the college years: Cross-sectional and prospective perspectives. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 15, 350–359. doi:10.1037/0893-164X.15.4.350

- Ochollo-Ayayo, A. B. C., & Schwarz, R. A. (1991). Report on sex practices and the spread of STDs and AIDS in Kenya. Nairobi: University of Nairobi.

- Oei, T. S., & Jardim, C. (2007). Alcohol expectancies, drinking refusal self-efficacy and drinking behaviour in Asian and Australian students. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 87(2–3), 281–287. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.08.019

- Oei, T. S., & Morawska, A. A. (2004). A cognitive model of binge drinking: The influence of alcohol expectancies and drinking refusal self-efficacy. Addictive Behaviors, 29, 159–179. doi:10.1016/S0306-4603(03)00076-5

- Okafor, I., & Obi, S. N. (2005). Sexual risk behaviour among undergraduate students in Enugu, Nigeria. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 25(6), 592–595. doi:10.1080/01443610500239511

- Orchowski, L., & Barnett, N. (2012). Alcohol-Related sexual consequences during transition from High school to College. Addictive Behaviour, 37(3), 256–263. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.10.010

- Park, C., & Grant, C. (2005). Determinants of positive and negative consequences of AC in college students: Alcohol use, gender, and psychological characteristics. Addictive Behaviours, 30, 755–765. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.08.021

- Parks, K., Hsieh, Y., Collins, L., Levonyan-Radloff, K., & King, L. (2008). Predictors of Risky sexual behaviour with new and regular partners in a sample of women bar drinkers. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 70(2), 197–205.

- Patrick, M. (2013). Daily associations of alcohol use with sexual behaviour and condom use during spring break. Drug and Alcohol Review, 32, 215–217. doi:10.1111/dar.2013.32.issue-2

- Patrick, M. E., & Maggs, J. L. (2010). Profiles of motivations for alcohol use and sexual behavior among first-year university students. Journal of Adolescence, 33, 755–765. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2009.10.003

- Pearson, M., D’Lima, M., & Kelly, M. (2011). Self-regulation as a buffer of the relationship between parental alcohol misuse and alcohol-related outcomes in first-year college students. Addictive Behaviours, 36(2011), 1309–1312. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.07.009

- Pithey, A. L., & Morojele, N. K. (2002). Literature review on alcohol use and sexual risk behaviour in South Africa. A report. Prepared for WHO project alcohol and HIV infection: Development of a methodology to study determinants of sexual risk behaviour among alcohol users in diverse settings. Retrieved from www.mrc.ac.za/adorg/publications.2002.pdf

- Quinn, P. D., & Fromme, K. (2010). Self-regulation as a protective factor against risky drinking and sexual behavior. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 24, 376–385. doi:10.1037/a0018547

- Radanielina-Hita, M. (2015). Parental mediation of media messages does matter: More interaction about objectionable content is associated with emerging adults’ sexual attitudes and behaviours. Health Communication, 30(8), 784–798. doi:10.1080/10410236.2014.900527

- Randolph, M., Torres, H., Gore-Felton, C., Lloyd, B., & McGarvey, E. (2009). Alcohol use and sexual risk behaviour among college students: Understanding gender and ethnic differences. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 35, 80–84. doi:10.1080/00952990802585422

- Rehm, J., & Room, R. (2003). The global burden of disease 2000 for alcohol, tobacco and illicit drugs. (Paper presented at the conference on preventing substance use, risky use and harm: What is evidence-based policy, Fremantle, Australia, February 2003).

- Rinker, D., & Neighbors, C. (2013). Social influence on temptation: Perceived descriptive norms, temptation and restraint, and problem drinking among college students. Addictive Behaviours, 38(2013), 2918–2923. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.08.027

- Rutledge, P.C, & Sher, K.J. (2001). Heavy drinking from the freshman year into early young adulthood: the roles of stress, tension-reduction drinking motives, gender and personality. J Stud Alcohol, 62(4), 457-66.

- Schraufnagel, T., Davis, K., George, W., & Norris, J. (2010). Childhood sexual abuse in males and subsequent risky sexual behaviour: A potential alcohol use pathway. Child Abuse Neglect, 34(5), 369–378. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.08.013

- Schulenberg, J., O’Malley, P. M., Bachman, J. G., Wadsworth, K. N., & Johnston, L. D. (1996). Getting drunk and growing up: Trajectories of frequent binge drinking during the transition to young adulthood. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 57, 289–304. doi:10.15288/jsa.1996.57.289

- Scott-Sheldon, L., Carey, M., Carey, K., Cain, D., Heirel, O., Mehlomkula, V., … Kalichman, S. (2012). Patterns of alcohol use and sexual behaviours among current drinkers in Cape Town, South Africa. Addict Behav, 37(4): 492–497

- Sells, C. W., & Blum, R. W. (1996). Current trends in adolescent health. In R. J. DiClemente, W. B. Hansen, & L. E. Ponton (Eds.), Handbook of adolescent health risk behavior (pp. 15–21). New York, NY: Plenum Press.

- Seth, P., Wingood, G., DiClemente, R., & Robinson, L. (2011). Alcohol use as a maker for risky sexual behaviours and biologically-confirmed sexually transmitted infections among young adult African American women. Womens Health Issues, 21(2), 130–135. doi:10.1016/j.whi.2010.10.005

- Shin, H., Hong, H., & Jeon, S. (2012). Personality use: The role of impulsivity. Addictive Behaviours, 37(2012), 102–107. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.09.006

- Sönmez, S, Apostolopoulos, Y, Yu, C, Yang, S, Mattila, A, & Yu, L. (2006). Binge drinking and casual sex on spring break. Annals Of Tourism Research, 33(4), 895-917.

- South African Community Epidemiology Network on Drug Use (SACENDU). (2011). Monitoring alcohol and drug abuse treatment admissions in South Africa. ISBN: 978-1-920014-77-3

- Stacy, A. W., Widaman, K. R., & Marlatt, G. A. (1990). Expectancy models of alcohol use. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58, 918–928. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.58.5.918

- Stappenbeck, C, Norris, J, Kiekel, P, Morrison, D, George, W, Davis, K, Jaczques-Tiura, A, & Abdallah, D. (2013). Patterns of alcohol use and expectancies predict sexual risk taking among non-problem drinking women. Journal Of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 74(2), 223-232.

- Stewart, S. H., & Devine, H. (2000). Relations between personality and drinking motives in young people. Personality and Individual Differences, 29, 495–511. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(99)00210-X

- Stuewig, J., Tangney, J., Kendall, S., Folk, J., Meyer, C., & Dearing, R. (2015). Children’s proneness to shame and guilt predict risky and illegal behaviour in young adulthood. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 46, 217–227. doi:10.1007/s10578-014-0467-1

- Testa, M., & Collins, R. L. (1997). Alcohol and risky sexual behavior: Event-based analyses among a sample of high-risk women. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 11, 190–201. doi:10.1037/0893-164X.11.3.190

- Townsend, L., Ragnarsson, A., Mathews, C., Johnson, L., Ekström, A., Thorson, A., & Chorpra, M. (2011). “Taking care of business”: Alcohol as a Currency in transactional sexual relationship, South Africa. Qualitative Health Research, 21(1), 41–50. doi:10.1177/1049732310378296

- Townshend, J., Kambouropoulos, N., Griffin, A., Hunt, F., & Milani, R. (2014). Binge drinking. Reflection Impulsivity, and Unplanned Sexual Behaviour: Impaired Decision-Making in Young Social Drinkers. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 38(4), 1143–1150.

- Turrisi, R., Wiersma, K., & Hughes, K. (2000). Binge drinking-related consequences in college students: The role of drinking beliefs and parent-teen communications. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 14, 342–355. PubMed: 11130153. doi:10.1037/0893-164X.14.4.342

- Vicary, J. R., & Karshin, C. M. (2002). College alcohol abuse: A review of the problems, issues, and prevention approaches. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 22, 299–331. doi:10.1023/A:1013621821924

- Vivancos, R., Abubakar, I., Phillips-Howard, P., & Hunter, P. (2013). School-based sex education is associated with reduced risky sexual behaviour and sexually transmitted infections in young adults. Public Health, 127, 53–57. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2012.09.016

- Vogel-Sprott, M. (1974). Discrimination of low blood alcohol levels and self-titration in social drinkers. Quarterly Journal Of Studies on Alcohol, 35(1), 86-97.

- Voisin, D., Hotton, A., Tan, K., & DiClemete, R. (2013). A longitudinal examination of risk and protective factors associated with drug use and unsafe sex among young African American females. Children and Youth Service Review, 35(2013), 1440–1446. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2013.05.019

- Walsh, K., Latzman, N., & Latzman, R. (2014). Pathway from child sexual and physical abuse to risky sex among emerging adults: The role of trauma-related intrusions and alcohol problems. Journal of Adolescence Health, 54(2014), 442–448. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.09.020

- Walsh, K., Messman-Moore, T., Zerubavel, N., Chandley, R., DeNardi, K., & Walker, D. (2013). Perceived sexual control, sex-related alcohol expectancies and behaviour predict substance-related sexual revictimization. Child Abuse & Neglect, 37(2013), 353–359. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2012.11.009

- Wayment, H. A., & Aronson, B. (2002). Risky sexual behavior in American white college women: The role of sex guilt and sexual abuse. Journal of Health Psychology, 7, 723–733. doi:10.1177/1359105302007006876

- Wechsler, H., Davenport, A., Dowdall, G., & Moeykens, B. (1994). Health and behavioural consequences of binge drinking in college: A national survey of students at 140 campuses. JAMA. The Journal of the American Medical Association, 272, 1672–1677. doi:10.1001/jama.1994.03520210056032

- Wechsler, H., Lee, J., Kuo, M., & Lee, H. (2000). College binge drinking in the 1990s: A continuing problem: Results of the harvard school of public health 1999 college alcohol study. Journal of American College Health, 48, 199–210. doi:10.1080/07448480009599305

- Wechsler, H., Lee, J. E., Kuo, M., Seibring, M., Nelson, T. F., & Lee, H. (2002). Trends in college binge drinking during a period of increased prevention efforts. Findings from 4 Harvard School Of Public Health College Alcohol Study surveys: 1993–2001. Journal of American College Health, 50, 203–217. doi:10.1080/07448480209595713

- Weinhardt, L. S., & Carey, M. P. (2000). Does alcohol lead to sexual risk behavior? Findings from event-level research. Annual Review of Sex Research, 11, 125–157.

- Weiser, S. D., Leiter, K., Heisler, M., McFarland, W., Percy-De Korte, F., DeMonner, S. M., … Bangsberg, D. R. (2006).A). population-based study on alcohol and high risk sexual behaviours in Botswana. PLOS Medicine, 3(10), 1940–1948. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0030392