Abstract

Eyewitness statements are commonly used in the criminal justice system and viewed as having a high-probative value, especially when the witness has no motive to lie, other witness recollection corroborates the account, or the witness is highly confident. A fatal police shooting incident in Sweden had 13 witnesses (nine civilians and four police officers) and was also filmed with two mobile phones. All interviews were conducted before witnesses viewed the films, allowing for the analysis of discrepancies between their statements and the videos. In this incident, a police patrol was sent to find out a man who was reported to have attacked two persons with a knife. When found, the perpetrator refused to obey the officer’s commands, and the police eventually shot at him. The analysis showed clear differences between the witness testimonies and the film. Elements associated with perceived threat, for example, the assailant’s armament and movement direction and number of shots fired, were remembered fairly accurately. However, most witnesses poorly recollected when, that is, after which shot, the assailant fell to the ground. Moreover, memory of the actual order of events was altered and important aspects omitted that were crucial from a legal point of view.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Eyewitness statements are commonly used in the criminal justice system and viewed as having a high-probative value, especially when the witness has no motive to lie or the witness is highly confident. However, much of the research is based on laboratory studies and its questionable to what extent the results parallel real-life situations. The present study is a rare opportunity to analyze a real-life situation. Several persons saw a police shooting with fatal outcome and gave their witness statements without knowing the fact that the whole event was filmed with a mobile phone. This gave us an opportunity to analyze if there were any differences between the film and the witnesses’ statements. The analysis showed that witness remembered central part of the event, but was unable to correctly report the order of the particular actions in the event. The legal consequences are discussed.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing Interest.

1. Introduction

The use of eyewitness statements is very common and often considered by the criminal justice system to possess a high-probative value, especially when the witness has no motive to lie and when veracity is corroborated by other witness recollection or the witness is highly confident (e.g., Kebbell & Milne, Citation1998; Wells, Memon, & Penrod, Citation2006). Nevertheless, an abundance of research has brought into question the validity of these recollections and highlighted various factors that can give rise to biased recall (Arkowitz & Lilienfeld, Citation2010; Wixted & Wells, Citation2017).

Another important issue concerns the validity and usefulness of conclusions based merely on laboratory studies (for a discussion on real-life vs. laboratory, see Wagstaff et al., Citation2003; Yuille, Ternes, & Cooper, Citation2010). The overwhelming body of research on eyewitnesses is based on what Yuille et al. (Citation2010) call “laboratory witnesses”; that is, findings based on research conducted in a laboratory, often with the belief that the results are generalizable to real-life situations, thus constituting something reliable and useful to the legal justice system. Research based on archival studies or real-life settings, on the other hand, does not always support “laboratory conclusions” but sometime points in a different direction. Yuille et al. (Citation2010) states that the results from non-laboratory studies are in general more complex or heterogeneous, while the pattern found in laboratory studies are relatively consistent. Examples of conditions were these discrepancies commonly are found, are “gun-focus effect” and effects on memory caused by stress (for a discussion see Yuille et al., Citation2010). In comparison to laboratory research, however, archival studies or real-life settings are very scarce. Furthermore, for obvious reasons, real-life scenarios permit less control and are, therefore, more difficult to reliably analyze. This makes the comparison between laboratory and non-laboratory studies complicated. Nevertheless, these studies constitute an extremely important part of the overall understanding of eyewitness memory: a finding detectable in the laboratory but not in real-life is not only useless, but also potentially detrimental to the legal justice system. Research that can aid actors within the legal system without being influenced or framed by extraneous or even erroneous factors in their evaluation of eyewitness testimony must therefore be based on both laboratory and archival/real-life settings.

This study is based on the preliminary investigation protocol (Förundersökningsprotokoll Citation2013, 0150-K3305-13) from a real-life case, where the police officers responded to two reports involving two persons at different locations unprovoked having been stabbed in their throats. Eventually, the perpetrator was found, still with a knife in his hand. He refused to obey the officer’s commands and was, tragically, fatally wounded by gunshots inflicted by a policeman. From an eyewitness perspective, the incident is notable for several reasons: it took place in a residential area on a Sunday morning, which meant that the number of witnesses was high (there were 19 witnesses interviewed). The incident was unexpected and progressed rapidly; hence, the witnesses were taken by surprise and completely unprepared. Furthermore, because of the violent nature of the incident, the level of stress induced in the witnesses and police officers responding to the active threat in the situation were most likely high. Finally, and most important, the last part of the incident was filmed with two mobile phones, something that provided an opportunity to evaluate the accuracy of the eyewitness statements.

In this case, from a legal point of view, the most important aspect was whether the use of deadly force—the police officer firing at the perpetrator—was in keeping with prevailing laws. The police officer firing the shots was indicted but acquitted. However, the purpose of this study was not to evaluate the verdict but to, exploratory, analyze what perceptual distortions there were, when comparing the eyewitness testimonies to the filmed recordings of the event. For example, how many witnesses remembered correctly the number of shots fired? What effect did the shots have on the offender? What actions were taken by the offender as well as by the police officers involved and in what order?

2. Method and analysis

2.1. The shooting incident

A police patrol was sent to an address in the central part of a small town, where a stabbing allegedly had occurred. When the patrol arrived, they found a man seriously injured, with a knife wound to the neck. The police initiated a search for the perpetrator without success. About an hour later, the communication central received a report of a second stabbing. Soon after arriving at the address of the second incident, the police noticed a man on a first-floor balcony of an apartment house, with a kitchen knife in his hand, loudly claiming that he was the man the police was seeking. The police commanded him several times to put down the knife, without any response from the man. The perpetrator then jumped from the balcony and walked into the middle of a nearby street, still without responding to the commands from the police to put down the knife. The man advanced toward one of the officers, who unholstered his gun. At this point, a witness started to film the incident with a mobile phone from a position above and behind the police officer. At the same time, another person filmed a part of the incident from another angle. None of these two persons were interviewed and included in the study. The man continued to move toward the police officer, who moved backward, repeatedly loudly commanding the perpetrator to drop the knife. The police officer then fired two warning shots in the air, but the man showed no signs of obeying the commands to put down the knife and halt. The police officer then fired for effect two shots at the lower parts of the man’s body (stomach and legs), who immediately fell to the ground. The man tried to get up, but when unable to do so, rolled over and crawled on his knees toward the officer, still holding the knife in his hand. The police officer fired a fifth shot, for effect also at the lower parts of the man body. The man then stopped, still on his knees and holding onto the knife, and was rapidly approached by two other police officers, one of whom hit him several times with a baton while the other emptied a can of OC spray (pepper-spray) in his face. The man slowly collapsed on the ground, and although paramedics were present at the scene, the gunshots became fatal. The earlier-described events can be clearly seen on one of the films. The analysis of the bullet trajectories within the perpetrator’s body and considering the relative positions of the perpetrator and the police officer when the shots were fired, revealed that the third shot likely caused a leg lesion, the fourth shot was probably a fatal hit in the stomach area, whereas the fifth shot missed the perpetrator. However, it could not with absolute certainty be established, an alternative is that the fourth shot missed and the fifth was lethal. Later, it was established that the perpetrator prior to the shooting incident had cut a third victim in the throat, a woman who died of her injuries.

2.2. Analysis

The data were based on the protocols of interviews with the police officers and witnesses from the preliminary investigation protocol (Förundersökningsprotokoll Citation2013, 0150-K3305-13). The protocols are written reports by the interviewing police officer, describing the witness’s account of the incident. These types of reports are standard practice of the Swedish police force, and therefore also the material the court uses in their assessments. All interviews, but one, were conducted within 3 days after the incident. There were nine civilian witnesses and four police officers interviewed who reported seeing the event.Footnote1 There were 12 different police officers conducting the interviews and afterward all interviewees read and confirmed the correctness of their statements. The police officers were interviewed twice, but only the first interview was used in the primary analysis. At the time for the second interview, the existence of the film was known to the police-officers, and they claimed to have seen it. Therefore, the second-time interviews were of no importance to the basic analysis. However, it can be noted that when confronted with how the event progressed, as shown in the film, one of the police-officers commented on the discrepancies between the statements in the first interview and the film. He said that he could see how it happened, but that was not how he experienced it.

The preliminary investigation protocol, which constitutes the basis for this study, is publicly accessible and because no individuals are identifiable merely on the basis of the analysis done in the study, it’s in line with the prevailing ethic regulations. The accuracy of the all witness interviews was evaluated by matching them to the mobile phones’ video recordings.

In the analysis, details such as presence of weapon, numbers of shots fired, things the involved person said or shouted were counted. Moreover, to what extent the succession of events was correctly described was analyzed. From a police perspective, much information can be generated afterward (clothing, weapon used, etc.) because the perpetrator was apprehended on the scene. The number of shots fired, in this case by the police, can also with a high (if not absolute) degree of certainty be established by the crime scene investigation. The progression of the event, on the other hand, cannot be established with certainty; therefore, the analysis of the witness statements revolves around what happened and in what order.

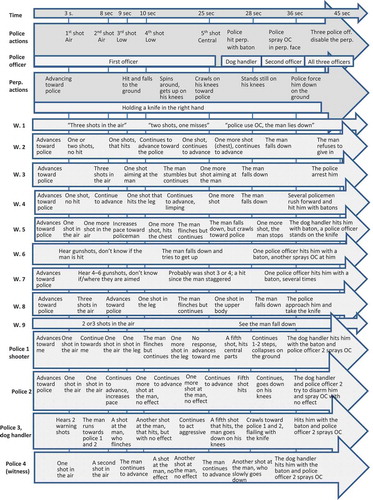

Witness statements were organized along a timeline based on timing of the actual event, as recorded by the mobile phones. The witnesses do not give any estimates of the duration between, for instance, the shots, but their statements are ordered in a timeline based the mobile phone recording. The degree of consistency between the statements and the actual related event was evaluated by two of the authors independently.

3. Results

Six of the 13 witnesses claimed that five shots were fired while the others cited numbers ranging from three to six. In some cases, the witnesses did not specify an exact number but gave a range (Figure ). All 13 witnesses reported seeing the knife, and several were even more specific, using terms like “kitchen knife”, “stainless knife”, or “a big silvery knife”. Furthermore, all 13 witnesses reported hearing the police shouting “drop the knife”. Figure gives an overview of the witness and officer statements and to what extent they correspond to the actual course of events.

All but one of the 13 witnesses reported seeing the perpetrator advancing toward the policeman. All 13 also reported that the policeman fired warning shots into the air and the perpetrator ignored these warnings shots and continued to advance toward the policeman. To this point in the timeline of events, the testimonies were fairly consistent and in accordance with what the film clips showed. However, the accounts then began to diverge to various extents from the actual course of events: Twelve of 13 witnesses, including the police officers, reported that the perpetrator was hit by the third or fourth shot, but with very limited effect. The perpetrator was reported to have “flinched”, “staggered”, “continued limping”, or simply “been unaffected”. Nine of 13 witnesses reported that the perpetrator continued to advance and an additional bullet was then fired that stopped the perpetrator and made him fall to the ground. Only one witness (witness 5; Figure ) reported correctly a shot being fired when the perpetrator was lying down or on his knees. All witnesses then reported that the perpetrator was approached by the other police officers and incapacitated, described with various degrees of detail.

4. Discussion

The main finding is that the ability to correctly report the actual course of action was affected. As the results show, the main aspects of the incident were included, but the order was altered or disintegrated from the actual timeline. Interestingly, it seemed to be offset in time, in which the moment for firing the last bullet was “moved” to the episode prior to the actual fall of the perpetrator and integrated into the firing of bullets 3 and 4. An alternative interpretation is that the firing of bullet 5 was omitted from the recollections, but this possibility is contradicted by the fact that most of the witnesses correctly reported that five bullets were fired. Regardless, the effect was a seemingly systematic bias in which all but one (witness 5; Figure ) of the witnesses reported that the perpetrator was hit by the third or fourth shot, but with only limited effect, and that he continued to advance toward the policeman and fell as a result of the fifth or last shot.

What, then, could be the cause of these biases? A first possible explanation is that all witnesses and the police officers had coordinated their statements and simply were lying. This explanation seems unreservedly improbable, however. The police officers could be suspected of having an interest in describing the situation favouring the righteousness of their actions to avoid an indictment of the shooter. There is, however, no reason to assume that the civilians shared this interest. Hence, because the statements of the civilians and the police officers did not differ on any crucial point, the most plausible conclusion is that the police officers did not consciously try to adjust their statements. A second possibility is that the police officers who conducted the interviews, consciously or unconsciously, favouring certain aspects of the statements, in order to stress a particular interpretation of the incident. This possibility seems, like the first one, implausible. According to the preliminary investigation protocol, there were 12 different police officers conducting the interviews and afterward all interviewees read and confirmed the correctness of their statements. Taken together, this makes it highly unlikely that the differences between the film recording and the statements are due to a deliberate “misinterpretation”, or even an unconscious information bias, ascribable to the involved police officers.

An alternative and, in our opinion, more plausible interpretation of the discrepancy is that it arose from an interaction of several cognitive factors, where acute stress, attention, and schema are the most plausible candidates. We discuss each of these in the following sections.

4.1. Stress and attention

First of all, it is safe to assume that an event like this induces stress for both witnesses and the police officers. To what extent is impossible to evaluate, although an indication is given in those cases in which eyewitnesses or police officers give a subjective evaluation. Thus, perception and memory distortions related to various levels of elevated stress can be expected.

How do these various degrees of stress affect witness perception and memory? There are no clear-cut answers because the findings are mixed. One reason is individual differences in how stressful a particular event is and individual differences in response (for an overview, see Deffenbacher, Bornstein, Penrod, & McGorty, Citation2004; Reisberg & Heuer, Citation2007).

Another reason is that the relationship between stress, perception and memory performance does not seem to be linear, and a moderate stress level predicts an enhancement in memory performance (e.g. Reisberg, Heuer, McLean, & O’Shaughnessy, Citation1988). The picture at a high level of stress is more complex: in some cases, impairment is found, for instance (Arrigo & Pezdek, Citation1997). The memory impairment is often, theoretically, summed up in the traumatic memory argument where recollections predicted to contain sensory and emotional information, but lack coherent narrative. Conversely, the traumatic superiority argument predicts an enhancement in memory quality in stressful memories, where traumatic events are remembered as vividly and correctly as mildly stressful events (McNally, Citation2003; Peace & Porter, Citation2004; for discussion see Porter, Woodworth, & Doucette, Citation2007)

A third reason for the variability centres on whether the subject is in an emotional state prior to the witnessed event or if the witnessed event itself induces the emotionality. In the first case, an enhancement of negative material compared to neutral material is found (Payne et al., Citation2006, Citation2007), while material or an event eliciting a negative emotional state impairs some aspects of memory, such as the peripheral information compared to the central (Reisberg & Heuer, Citation2004). A plausible explanation for this situation is the attention-grabbing power of emotional material. Something that results in a biased perception toward the emotional material (e.g., Calvo & Lang, Citation2004; Nobata, Hakoda, & Ninose, Citation2010; Valentine & Mesout, Citation2009) can in turn lead to privileged processing in the episodic memory system compared to the less attended material (Compton, Citation2003). In a similar vein, a well-documented phenomenon is the Easterbrook hypothesis (Easterbrook, Citation1959), which basically states that the memory for the central parts or gist of an event is more accurately and completely remembered compared to peripheral details of the same event (for overviews, see McNally, Citation2003; Reisberg & Heuer, Citation2004). The reason for the discrepancy is, as described previously, that stress narrows the attention to the stress-generating features at the expense of attention to other (peripheral) features. It is important, though, to note that the distinction between “central” and “peripheral” details is subjective; what in retrospect can be considered as forensically relevant and thus “central” does not necessarily coincide with what the witness perceives as “central” (Read & Connolly, Citation2007). In addition, the information do not necessarily has to be presented spatially in the centre of the field of view; rather, it is the content of the information that is perceived as central, or essential for the line of events, which defines “central” in the distinction “central–peripheral” (Heuer & Reisberg, Citation1990). The Easterbrook hypothesis also accounts for the well-documented finding known as the “weapon-focus effect” (for reviews, see Fawcett, Russell, Peace, & Christie, Citation2013; Steblay, Citation1992). It states that the presence of a weapon grabs the attention of the witness, enhancing the memory for the weapon, but at the same time impairing perception and memory for other aspects of the event. In other words, the weapon is “central” and other details are “peripheral”.

As mentioned earlier, the findings of stress are mixed. In some cases, the recollection of an event is enhanced, but sometimes the effect is detrimental. Deffenbacher et al. (Citation2004) states, however, that stress always impairs memory for, at least, details. The claim of the Easterbrook hypothesis is also an impaired memory for peripheral details.

In this case, the perpetrator held a large knife in his hand, and the police officer, on several occasions, commanded him to drop the knife, something that can be expected to have increased the attention of the eyewitnesses toward the object in the man’s hand. In other words, a weapon-focus effect, most likely amplified by an elevated stress level, could be expected. As a consequence, an impairment of the memory for other details can be expected.

Furthermore, actual movements of police officers present at the scene but not directly engaged and the presence and movements of other people such as witnesses can also be considered peripheral information because it did not alter or affect the course of the central event. But, what about number of shots fired or the actual progression of the event and the elapsed time between the shots? Did the perpetrator fall to the ground after or before the last shot? Did he continue his movement toward the officer after he was hit and if so, was it on foot or was it by crawling? It is not obvious if this information is “central” or “peripheral”. From a judicial point of view, this information is of utmost importance and therefore “central”, but it is quite unlikely that an unprepared witness automatically would apply a legal focus when encountering an incident and focus on the “central” aspects based on their legal relevance.

4.2. Schema

Another plausible distortion is related to script-based interpretation: to organize and understand new situations, we use knowledge-based schema or scripts (i.e., Bower, Black, & Turner, Citation1979; Greenberg, Westcott, & Bailey, Citation1998). When we encounter a familiar situation, we activate a schema and apply its structure to the new situation to faster and more easily comprehend and interpret it. Several studies have shown that this application of a schema also applies when witnessing a crime (Holst & Pezdek, Citation1992; Luna & Migueles, Citation2008; Tuckey & Brewer, Citation2003). For instance, when witnessing a robbery, a schema for “robbery” is activated based on prior knowledge and experience of robbery. If, however, the witnessed robbery was “atypical” compared to the activated schema, there is a risk of distortion and a less correct memory representation of the robbery. Thus, if there are some gaps in information about the event or parts of the event are ambiguous in the activated schema, missing parts are filled in and the interpretation most similar to the activated schema is done. The resulting memory representation is thus not only based on information encoded while witnessing the crime, but also on the schema the witness activates (Greenberg et al., Citation1998; Tuckey & Brewer, Citation2003).

A possible “schema” in this case would be as follows: a perpetrator who advances toward a policeman with an unholstered gun and does not stop when commanded or when the policeman fires a warning shot will most likely be shot. When being shot at a close range, it is likely that the perpetrator falls to the ground. When lying on the ground, he poses much less threat and can be approached and disarmed. In a general sense, this is what happened, but with some “atypical” biases: the perpetrator did not stop even though he was shot and fell, and he was then fired upon again while he was moving on his knees and, finally, being approached by the other police officers and disarmed. This diversion, from a “typical script” is, as the result shows, something the witnesses are unable to correctly adjust for.

4.3. Limitation of the study

This is an analysis of a real-life situation, so the causes of the distortions are, of course, speculation rather than experimentally supported conclusions. Another problem concerns the risk of circular argumentation: when analysing something in retrospect, there is a risk of stating predictions that are known to be supported in the data. Furthermore, because the interviews were not systematically conducted in the sense that the same questions were posed to all interviewees. It was not possible to reliably quantify the responses; that is, it would not be possible to reliably determine whether a particular detail was omitted because the witness actually missed it during encoding or if the witness omitted it when conveying information during the interview. Nor is it possible to fully control for the post-event factors. Of special interest in this case is the fact that one of the mobile films of the event was uploaded to the internet and possibly accessible to the witnesses, something that would have had a devastating effect on testimony reliability. In this type of study where a laboratory-experiment degree of control is not possible, the probabilities for the different alternatives must be assessed. In the witness interviews, no one mentioned the film, except for a paramedic, whose interview was conducted later, and he did mention the film. He was therefore excluded from the analysis. Moreover, the second time the police-officers were interviewed, one of them mentioned seeing the film (after the first interview). In the second interview, they also commented on the discrepancies between the film and their statements in the first interview (as mentioned above). If they had seen the film before the first interview, it seems highly implausible that they deliberately would state something not shown in the film. Taken together, even though absolute certainty cannot be reached, the probability that the witnesses at the time for the interview had not seen the film seem high enough to make the analysis interesting.

5. Conclusion

There were obvious differences between the films and the statements made by the witnesses. They cannot correctly report the actual progression of the event; yet, the bias was similar in almost every witness statement even though the type of involvement in the incident varied (some were passive witnesses while others were active police officers). This consistency of inaccuracy indicates general biases rather than biases connected to a particular witness role or position during the incident. It is fairly safe to assume that there is a considerable increase in the stress level, in a case like this, varying from low or moderate/high, most likely, depending on the whether you are a bystander or the police-officer handling the situation. Because stress is an often-present factor in forensically relevant situations, but difficult to induce for ethical reasons, the real-life studies constitute important pieces of information when understanding how stress effects and interacts with other, often more easily experimentally manipulated, estimator variables.

From a legal point of view, these biases are of great importance because eyewitness statements are common and often considered to have a high-probative value (Wells et al., Citation2006). As discussed earlier, it’s important to stress, what from the witness perspective at the time of the encoding, most likely, can be seen as the central part, or the gist of a situation, don’t necessarily coincide with a retrospective analysis of the course of event where the central aspects or the gist are defined from a legal perspective. That is, for instance, “if a particular event had occurred, the witnesses could not have missed it, since it is a ‘central’ aspect”. But, is it still “central” when considering the conditions present during encoding, not knowing final result, or is it “central” only when analysing in retrospect knowing how the event a progressed or at least, its results? In this case, 12 of 13 witnesses state a similar version on some of the crucial parts of the progression of the incident, that is, after which shot the man falls, a level of witness agreement that most likely would lead most courts to believe that truth is established beyond reasonable doubt; yet, video evidence proves these 12 in-agreement witnesses wrong.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Mats Dahl

The authors are a multi-disciplinary group, which consists of researchers from behavioral science, medicine, and the police academy. Their focus is on the effects of stress on performance and cognition within high-risk occupations. Their goal is to combine traditional laboratory studies with ecologically valid studies, both archival studies and studies were police-officers, or military personal act in scenarios similar to real-life situations.

Notes

1. In the preliminary investigation protocol, there were nine additional persons interviewed. They are omitted from the analysis because they reported not being present at the scene or not seeing anything of the actual event.

References

- Arkowitz, H., & Lilienfeld, S. O. (2010). Why science tells us not to rely on eyewitness accounts. Scientific American, January 1 Retrieved from http://www.scientificamerican.com/2017-02-12

- Arrigo, J. M., & Pezdek, K. (1997). Lessons from the study of psychogenic amnesia. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 6, 148–152. doi:10.1111/1467-8721.ep10772916

- Bower, G. H., Black, J. B., & Turner, T. J. (1979). Scripts in memory for text. Cognitive Psychology, 11, 177–220. doi:10.1016/0010-0285(79)90009-4

- Calvo, M. G., & Lang, P. J. (2004). Gaze patterns when looking at emotional pictures: Motivationally biased attention. Motivation and Emotion, 28, 221–243. doi:10.1023/B:MOEM.0000040153.26156.ed

- Compton, R. (2003). The interface between emotion and attention: A review of evidence from psychology and neuroscience. Behavioral and Cognitive Neuroscience Reviews, 2, 115–129. doi:10.1177/1534582303002002003

- Deffenbacher, K. A., Bornstein, B. H., Penrod, S. D., & McGorty, E. K. (2004). A meta-analytic review of the effects of high stress on eyewitness memory. Law and Human Behavior, 28, 687–706. doi:10.1007/s10979-004-0565-x

- Easterbrook, J. A. (1959). The effect of emotion on cue utilization and the organization of behavior. Psychological Review, 66, 183–201. doi:10.1037/h0047707

- Fawcett, J. M., Russell, E. J., Peace, K. A., & Christie, J. (2013). Of guns and geese: A meta-analytic review of the ‘weapon focus’ literature. Psychology, Crime & Law, 19, 35–66. doi:10.1080/1068316X.2011.599325

- Förundersökningsprotokoll. (2013). 0150-K3305-13. Rikspolisstyrelsen IU. Stockholm

- Greenberg, M. S., Westcott, D. R., & Bailey, S. E. (1998). When believing is seeing: The effect of scripts on eyewitness memory. Law and Human Behavior, 22, 685–694. doi:10.1023/A:1025758807624

- Heuer, F., & Reisberg, D. (1990). Vivid memories of emotional events: The accuracy of remembered minutiae. Memory & Cognition, 18, 496–506. doi:10.3758/BF03198482

- Holst, V. F., & Pezdek, K. (1992). Scripts for typical crimes and their effects on memory for eyewitness testimony. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 6, 573–587. doi:10.1002/acp.2350060702

- Kebbell, M., & Milne, R. (1998). Police officers’ perceptions of eyewitness performance in forensic investigations. The Journal of Social Psychology, 138, 323–330. doi:10.1080/00224549809600384

- Luna, K., & Migueles, M. (2008). Typicality and misinformation: Two sources of distortion. Psicológica, 29, 171–188.

- McNally, R. J. (2003). Remembering trauma. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Nobata, T., Hakoda, Y., & Ninose, Y. (2010). The functional field of view becomes narrower while viewing negative emotional stimuli. Cognition & Emotion, 24, 886–891. doi:10.1080/02699930902955954

- Payne, J. D., Jackson, E. D., Hoscheidt, S., Ryan, L., Jacobs, W. J., & Nadel, L. (2007). Stress administered prior to encoding impairs neutral but enhances emotional long-term episodic memories. Learning & Memory, 14, 861–868. doi:10.1101/lm.743507

- Payne, J. D., Jackson, E. D., Ryan, L., Hoscheidt, S., Jacobs, J. W., & Nadel, L. (2006). The impact of stress on neutral and emotional aspects of episodic memory. Memory, 14, 1–16. doi:10.1080/09658210500139176

- Peace, K. A., & Porter, S. (2004). A longitudinal investigation of the reliability of memories for trauma and other emotional experiences. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 18, 1143–1159. doi:10.1002/acp.1046

- Porter, S., Woodworth, M., & Doucette, N. L. (2007). Memory for murder: The qualities and credibility of homicide narratives by perpetrators. In S. Å. Christianson (Ed.), Offenders memories of violent crimes. Chichester: Wiley.

- Read, J. D., & Connolly, D. A. (2007). The effects of delay on long-term memory for witnessed events. In M. P. Toglia, J. D. Read, D. F. Ross, & R. C. L. Lindsay (Eds.), Handbook of eyewitness psychology: Volume 1: Memory for events (pp. 117–155). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc.

- Reisberg, D., & Heuer, F. (2004). Memory for emotional events. In D. Reisberg & P. Hertel (Eds.), Memory and emotion. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Reisberg, D., & Heuer, F. (2007). The influence of emotion on memory for forensic settings. In M. P. Toglia, J. D. Read, D. F. Ross, & R. C. L. Lindsay (Eds.), The handbook of eyewitness psychology: Volume 1: Memory for events (pp. 81–116). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc.

- Reisberg, D., Heuer, F., McLean, J., & O’Shaughnessy, M. (1988). The quantity, not the quality, of affect predicts memory vividness. Bulletin of the Psychonomic Society, 26, 100–103. doi:10.3758/BF03334873

- Steblay, N. M. (1992). A meta-analytic review of the weapon focus effect. Law and Human Behavior, 16, 413–424. doi:10.1007/BF02352267

- Tuckey, M. R., & Brewer, N. (2003). How schemas affect eyewitness memory over repeated retrieval attempts. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 17, 785–800. doi:10.1002/acp.906

- Valentine, T., & Mesout, J. (2009). Eyewitness identification under stress in the London dungeon. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 23, 151–161. doi:10.1002/acp.1463

- Wagstaff, G. F., Macveigh, J., Boston, R., Scott, L., Brunas-Wagstaff, J., & Cole, J. (2003). Can laboratory findings on eyewitness testimony be generalized to the real world? An archival analysis of the influence of violence, weapon presence, and age on eyewitness accuracy. Journal of Psychology: Interdisciplinary and Applied, 137, 17–28. doi:10.1080/00223980309600596

- Wells, G. L., Memon, A., & Penrod, S. D. (2006). Eyewitness evidence: Improving its probative value. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 7, 45–75. doi:10.1111/j.1529-1006.2006.00027.x

- Wixted, J. T., & Wells, G. L. (2017). The relationship between eyewitness confidence and identification accuracy: A new synthesis. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 18(1), 10–65. doi:10.1177/1529100616686966

- Yuille, J. C., Ternes, M., & Cooper, B. S. (2010). Expert testimony on laboratory witnesses. Journal of Forensic Psychology Practice, 10, 238–251. doi:10.1080/15228930903550590