Abstract

Social media platforms can deliver benefits for their users. They help people to stay in touch with each other and to have control over how they present themselves to their contacts on these platforms. In some cases, these benefits lead to excessive usage, which can diminish individual wellbeing, and compromise relationships with significant others. We surveyed 275 respondents to investigate the influence of and interactions between (1) self-presentation (specifically false self-presentation), (2) FoMO (fear of missing out), and (3) phubbing (ignoring someone by diverting attention to a mobile phone) in the context of excessive Instagram use. We found that phubbing mediates the relationship between false self-presentation and excessive Instagram use but did not find evidence that phubbing mediates the relationship between FoMO and excessive Instagram use. We also found a positive relationship between excessive Instagram use and educational level. We conclude with a discussion on the theoretical and practical implications of the results.

1. Introduction

It has become common for individuals to have one or more social media accounts. Such accounts are used not only to stay in touch with friends and family, but also to consume and produce content—a pleasurable pastime for millions of individuals (Chen et al., Citation2021). However, there is the potential for usage to become excessive, consuming increasing amounts of time. This is referred to as “excessive Instagram use.” This is defined as either the use of the platform for prolonged (i.e., extended) periods or very frequent use for shorter periods (e.g., 20 times per day for 15 minutes). Such usage can lead to negative outcomes such as depression, anxiety, insomnia, anorexia nervosa or self-harm (Chancellor et al., Citation2016; D’Souza & Negahban, Citation2019).

We investigated the influence of three different factors on such excessive Instagram usage. The first was false self-presentation, which refers to how individuals behave or present themselves to others so as to create a certain impression (Michikyan et al., Citation2015). The second influence was FoMO, which is defined as individuals’ concern that they are missing out on chances of interpersonal contact with their peers (Roberts & David, Citation2020). The third factor was phubbing, which is the impolite (and antisocial) use of a mobile phone during an in-person conversation (“telephone” and “snubbing”; Karadaǧ et al., Citation2015). This is considered undesirable and negative (Chotpitayasunondh & Douglas, Citation2018; Ivanova et al., Citation2020; McDaniel & Wesselmann, Citation2021).

These factors have been investigated in other studies in the context of other kinds of usage. For example, recent studies have focused on self-presentation, investigating its direct influence within different contexts (Chen et al., Citation2019; González-Nuevo et al., Citation2021). Other studies have explored the mediating effects of FoMO—specifically in relation to smartphone addiction (Li et al., Citation2020; Servidio, Citation2019), problematic social media use (Fang et al., Citation2020; Oberst, Citation2016), and social media engagement (Reer et al., Citation2019). Studies that have focused on phubbing have investigated only its direct influence on smartphone addiction (Fu et al., Citation2020), specific psychological issues, such as negative emotions (Fellesson & Salomonson, Citation2020), well-being (Kadylak, Citation2020), work relationships (Roberts & David, Citation2020; Yasin et al., Citation2020), and parental care (Bai et al., Citation2020; Niu et al., Citation2020; Wang et al., Citation2020).

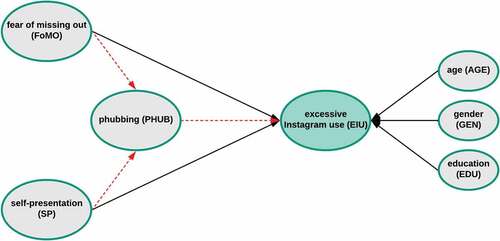

The interplay between the three factors, as proposed in our research model, is under-researched in the Instagram context, hence this investigation. We depict these interactions in figure , our proposed research model. Notably, we indicate the mediatory paths in dotted lines below.

To our knowledge, the only recent study that closely resembles ours is that of Çikrikci et al. (Citation2019). Given that phubbing is usually modeled as an outcome of excessive (or even problematic) social media use, the rationale for this study is to understand the extent to which phubbing may influence excessive use. We wanted to explore how phubbing and excessive Instagram usage are related. Our thinking in this regard is mirrored by that of Brailovskaia et al. (Citation2018) who found evidence to suggest that excessive Facebook use should not only be viewed as an outcome, but also as a potential moderator or mediator. We take a similar view, focusing specifically on the excessive use of Instagram. Given the lack of significant overlap with other studies, this paper makes a significant contribution to the field of cyberpsychology in general and excessive use of Instagram in particular.

We commence by developing the study hypotheses. Next, we provide a complete outline of our methodological approach, followed by the results of our statistical analysis. Following this, we briefly discuss some results and conclude with an outline of the theoretical and practical implications of this study.

2. Hypothesis development

2.1. Phubbing

Phubbing first appeared in 2007 in Australia (Nazir & Piskin, Citation2016) and has become a phenomenon of worldwide interest to laypersons and academia alike. The increase in the incidence of phubbing is likely due to the widespread availability and use of smartphones, as well as the pervasive co-present interactions found in society (Capilla Garrido et al., Citation2021). While there are numerous benefits that can be derived from the use of smartphones, there has been an increased focus on their negative consequences for the mental and physical health of users. Phubbing as a form of behavior detrimentally affects the quality of social interactions between people, as it is generally perceived to be disrespectful (Anshari et al., Citation2016; Dwyer et al., Citation2018). Importantly, phubbing takes place at any time and at any location, from family meals to formal work meetings and conferences, as well as social gatherings with family and friends. Phubbing involves one (or more) conversation partners being snubbed, with the mobile phone taking center stage instead of the focus being on physically co-present partners (Yasin et al., Citation2020). This may negatively affect relationships, increase feelings of jealousy (Balta, Emirtekin, Kircaburun, & Griffiths,, Citation2018) and, in extreme cases, lead to mobile phone addiction (Ivanova et al., Citation2020). In some instances, even those who experience being phubbed are further drawn into the use of social media in an effort to escape feelings of social exclusion (Ivanova et al., Citation2020).

As a result of phubbing, both parties may increase the excessiveness with which they use social media platforms such as Instagram. As such, and not surprisingly, phubbing has attracted attention from the research community. For example, phubbing has been found to exert a direct (and significant) influence on internet use disorders, abnormal smartphone use, depression, the communicative ability of users offline, as well as the intimacy of said communication (Bai et al., Citation2020; Balta et al., 2018; Ivanova et al., Citation2020). In this study, we evaluate the mediating effects of phubbing on excessive Instagram use. Understanding its influence is crucial in helping to explain the extent to which certain variables influence our phenomenon of interest (Nitzl et al., Citation2016). Within the context of this study, the phenomenon of interest is the excessive use of Instagram. The more excessive, the more likely it becomes that such usage will negatively impact these individuals (e.g., development of social media dependencies and an overall reduction in well-being). Mediation analysis enables us to understand the development of this phenomenon as a result of the influence of the mediating variable (Carrión et al., Citation2017). In other words, what insights do the mediating nature of phubbing offer us when studying excessive Instagram use? Although phubbing has received much attention within the Information Science (IS) discipline, few studies have explored the role of mediation within the context of excessive Instagram use. Even fewer studies have made use of partial least squares (PLS).

2.2. FOMO: Fear of Missing Out

Although we concede that individuals predominantly use Instagram via their smartphones, this study focuses on excessive use without focusing on the devices used. In other words, we want to determine the extent to which phubbing further explains excessive Instagram use as a function of individuals’ level of FoMO and self-presentation, regardless of the source device. Individuals experiencing high levels of FoMO desire to be constantly connected with other people by staying abreast of what they are doing (Roberts & David, Citation2020). Not surprisingly, platforms like Instagram are particularly well suited to engendering such connectedness. For example, individuals can “follow” the Instagram updates of just about anybody of interest. FoMO also causes individuals to ruminate on that which they might be missing out on, which makes them feel that they are unable to compete or keep up with their Instagram peers (Fuster et al., Citation2017). As a result, individuals may spend excessive amounts of time on social media to find content (and other individuals) with which they associate, to the point that such excessive use has a negative impact on the wellbeing of the individual in question. We argue that phubbing provides an additional explanation of such excessive use as a function of an individual’s level of FoMO. In other words, when an individual uses Instagram because they feel they are missing out, they may choose to phub real-life conversation partners. Because mediation modeling requires us to theorize (and test) the relationship between phubbing and excessive Instagram use, it is important to note that we are not arguing in favor of the enjoyable nature of phubbing. Instead, together with FoMO, phubbing becomes habitual, which then (and over time) influences excessive Instagram use and perhaps the prevalence of phubbing as well. For example, FoMO has been found to significantly influence phubbing within the context of smartphone use (Al-Saggaf, Citation2020). Given the predominant use of smartphones to access Instagram (which is, first and foremost, a mobile app), it stands to reason that this also applies here. Similar findings are reported for the influence of phubbing on excessive social media use, with recent studies reporting significant relationships between phubbing and social media addiction and problematic use (Bai et al., Citation2020; Guazzini et al., Citation2019), but these studies have not focused on Instagram.

2.3. Self-presentation

We also evaluated the extent to which phubbing mediates self-presentation. Self-presentation is regarded as an important social media activity (Subrahmanyam & Smahel, Citation2011). Arguably, such activities often center on users’ needs to share personal content on social media for reasons related to impression management and self-expression (Krämer & Winter, Citation2008). The immediacy of the feedback mechanisms (e.g., likes and comments) on various social networking site platforms (such as Instagram) provides individuals with clues about the social desirability of the information they are providing on these platforms. This feedback can then be used to adjust their future posts to bring them more in line with the self-presentation they would like to project to others. Individuals may also compare themselves to their peers, and then decide how to present themselves on social media to these peers (Chua & Chang, Citation2016). Additionally, online self-presentation helps individuals gain peer acceptance and feedback (Djafarova & Trofimenko, Citation2019). Therefore, the more individuals depend on such feedback, the more likely the excessive use of Instagram becomes. Importantly, and to increase followers, individuals also tend to present themselves positively on Instagram (Salim et al., Citation2017); in other words, more positively than is authentically true of themselves (Layder & Manning, Citation1994). However, as an individual’s followers increase, the more excessive their use of Instagram becomes in order to refine the way they portray themselves. The more positive the feedback, the more followers are gained. This perpetuates the cycle of excessive use as a function of their need to gain increasing amounts of positive feedback from followers. Ultimately, the ever-increasing excessive use of Instagram (for self-presentation purposes) may become problematic. For example, social media self-presentation (as enacted on Instagram) has been linked to reduced mental health and well-being. A study focusing on teenagers found that a high focus on social media self-presentation was linked to more mental health problems and a reduced quality of life. Specifically, there were strong associations with signs of depression and anxiety (Skogen et al., Citation2021). Research has revealed similar findings amongst adults where false self-presentation behaviors were associated with negative mental health, as seen by higher reported levels of anxiety, depression, and stress (Wright et al., Citation2018). The effects of social media-based false self-presentation are particularly problematic. For example, extant research has revealed significant associations between false self-presentation, high levels of social anxiety and low self-esteem (Twomey & O’Reilly, Citation2017). We argue that when individuals experience negative side effects of social media use (e.g., social anxiety, social exclusion, and low esteem) they are more likely to seek social approval by presenting themselves in an overly positive or even false manner. FoMO may further drive this process of false self-presentation, as any relevant social media activity may be viewed as a chance to enhance how they present themselves online. For some, engaging in these behaviors may be so vital to their psychological needs that they will use any available opportunity to engage in such behavior. In such instances phubbing may further strengthen (or even enable) the excessive use of Instagram. We hypothesize that:

H1: Phubbing mediates the relationship between FoMO and excessive Instagram use.

H2: Phubbing mediates the relationship between self-presentation and excessive Instagram use.

3. Methodological approach

3.1. Respondents and procedure

After receiving ethical clearance from the Rhodes University Ethical Standards Committee (RUESC; ref 2020–1448-3533), we collected data from 285 respondents recruited via a survey platform called Prolific (Chandler et al., Citation2019). Once recruited, potential respondents had to first provide informed consent before being allowed to continue with the associated survey questionnaire. In addition to providing informed consent, respondents had to be at least 18 years old, active Instagram users, and citizens of the United States of America. After applying the aforementioned criteria, we improved the data quality by disqualifying those respondents who did not complete the questionnaire or showed signs of inattentiveness (evaluated via attention check questions; Abbey & Meloy, Citation2017). Subsequently, 275 responses (n = 275) remained, of which 133 (48.4%) were male and 142 (51.6%) female. From an educational perspective, 94 (34.2%) respondents had no degree or were educated up to high school level, 128 (46.5%) were in possession of a bachelor’s degree and 53 (19.3%) were in possession of a master’s degree or above. Respondents’ ages varied with 90 (32.7%) aged 18–24, 114 (41.5%) aged 25–34, 41 (15%) aged 35–44, 21 (7.6%) aged 45–54, and nine (3.2%) aged 55–64.

3.2. Measures used

FoMO. Respondents’ levels of FoMO were evaluated by making use of a 10-item scale developed by Przybylski et al. (Citation2013). The scale makes use of five-point Likert scale response anchors (1 = Not at all true of me and 5 = Extremely true of me) and has been used extensively in similar, and recent, cyberpsychology contexts (Elhai et al., Citation2020; Fabris et al., Citation2020; Laato et al., Citation2020). After eliminating items with outer loadings below 0.7, we obtained a reliability score (i.e., Cronbach’s alpha) of 0.80.

Phubbing. To evaluate respondents’ propensity to phub conversation partners, we adapted a 10-item phubbing scale developed by Karadaǧ et al. (Citation2015). Like the scales described above, the phubbing scale uses a five-point Likert scale but makes use of different response anchors (1 = Never and 5 = Always). It should be noted that this scale has also been widely used within similar contexts (Busch & McCarthy, Citation2021; Harris et al., Citation2020; Ivanova et al., Citation2020). After eliminating items which exhibited factor loadings below 0.7, we obtained a reliability score of 0.81.

Self-presentation (based on SPFBQ). To evaluate Instagram-based self-presentation we adapted the Self-Presentation on Facebook Questionnaire (SPFBQ), which consists of 17 items (Michikyan et al., Citation2015, Citation2014). This scale assessed online self-presentation on a five-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly disagree and 5 = Strongly agree) and is widely used in cyberpsychology, specifically to evaluate to what extent a respondent expresses aspects of the real, ideal, and false on Facebook. Within this context the scale was adapted for Instagram, and we only used the false self-presentation subscale. A reliability score of 0.83 was obtained.

Excessive Instagram Use (based on the SMUQ). To evaluate the excessiveness with which respondents use Instagram, we adapted the nine-item Social Media Use Questionnaire (SMUQ) developed by Xanidis and Brignell (Citation2016). We felt this to be an apt choice given its focus on addiction or dependency formation which are often modeled as negative or problematic consequences of excessive social media use (Van der Schyff et al., Citation2020). These nine items were evaluated using a five-point Likert scale (1 = Never and 5 = Always) and achieved a reliability score of 0.85 after eliminating items with factor loadings below 0.7.

4. Statistical analysis and results

A cross-sectional survey was used to collect primary data, which was first analyzed to describe the correlations between all the variables in our research model (see, Table for these correlations). Following this we analyzed our data using the PLS algorithm to develop a path model in SmartPLS v3 (Ringle et al., Citation2015).

Table 1. Measurement model statistics including demographic correlates (** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01)

4.1. Measurement model evaluation

We first evaluated the validity of our measurement model—specifically convergent and discriminant validity. To assess convergent validity, we used three criteria. First, we checked that all the items within our research model loaded significantly (t-values of more than 1.96) onto their desired latent variables. Second, we checked that the items exhibited outer loadings in excess of the accept threshold of 0.7 (J. Hair et al., Citation2017). Third, the average variance extracted (AVE) value of each latent variable was checked to ensure that it was more than 0.5 (see, Table ). All the above criteria were satisfied. To assess discriminant validity, we made use of three criteria. First, we used the Fornell-Larcker criterion which required us to calculate the square root of the AVE value of each latent variable (on the diagonal in Table ). These values were all in excess of 0.5 and higher than the correlations of the related latent variables (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981). Second, we checked the cross-loadings of the items in our questionnaire (see Table in the Appendix). These items all loaded highest on their intended latent variables. Third, we assessed the heterotrait–monotrait (HTMT) ratios (see Table in the Appendix), which were all below the threshold of 0.85 (Henseler et al., Citation2014). From the above, we concluded that our measurement model was valid.

When developing path models using PLS, it is important to also assess the questionnaire for any signs of multicollinearity (Hair et al., Citation2019). To eliminate multicollinearity, a researcher has to inspect the variance inflation factor (VIF) values of the items to ensure that they are below 3.0 (Hair et al., Citation2010). All the VIF values were below 3.0, enabling us to eliminate multicollinearity (see Table in the Appendix). Given that all the latent variables exhibited reliability scores in excess of 0.7 for both the Cronbach’s alpha (CA) and composite reliability (CR) criteria, we declared the questionnaire to be reliable (Tavakol & Dennick, Citation2011). See, Table (below) and Table (in the Appendix) for a complete outline of our measurement model statistics and questionnaire descriptive statistics, respectively.

4.2. Structural model evaluation

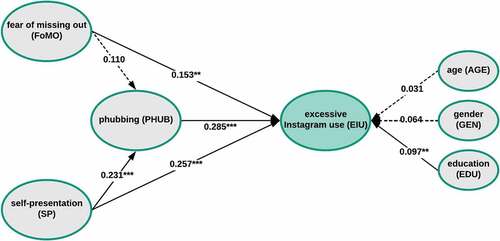

As part of the structural evaluation of our model, we calculated the predictive power (R2) of the dependent variables in our model. The dependent variable excessive Instagram use (EIU) achieved an R2 value of 0.263, whereas phubbing (PHUB) achieved an R2 value of 0.082. This indicates that 26.3% of the variance in EIU occurred because of an individual’s level of FoMO and phubbing. Additionally, 8.2% of the variance in PHUB occurred because of an individual’s level of FoMO and self-presentation (SP). We also calculated the relative impact of our independent variables on the dependent variables (i.e., phubbing, and excessive Instagram use) by inspecting their effect sizes derived from Pearson correlations. These correlations were interpreted in terms of Cohen’s guidelines for r, as presented in Table above. FoMO exhibited a small-to-medium positive effect (0.183) on phubbing and a medium positive effect (0.284) on excessive Instagram use. Self-presentation exhibited a small-to-medium positive effect (0.266) on phubbing and a medium positive effect (0.368) on excessive Instagram use, while phubbing exhibited a medium positive effect (0.391) on excessive Instagram use. In addition to the effect sizes and predictive power, the predictive relevance (Q2) of our model was also calculated (Geisser & Eddy, Citation1979; Stone, Citation1974). Stone-Geisser’s Q2 equaled 0.156 for excessive Instagram use and 0.047 for phubbing. Based on the these analyses we declared our model to exhibit reasonable predictive relevance (J. Hair et al., Citation2017; Vinzi et al., Citation2010). Finally, we also evaluated the influence of several demographic variables including gender, education, and age. Only education exhibited a significant (albeit weak) relationship with excessive Instagram use (β = 0.097, p < 0.05). Given that education is positively correlated to excessive Instagram use, there is some indication that excessive use is prevalent in more educated individuals, the implications of which we explore in the discussion. From the above it is clear that the model is structurally sound, enabling us to test for mediating effects.

4.3. Testing for mediating effects

Following the evaluation of our measurement and structural models, we proceeded to test for mediating effects. Mediation revolves around the idea that a third latent variable significantly alters the relationship between an independent and a dependent variable (excessive Instagram use). Within this context, phubbing acts as this third mediating variable, with FoMO and self-presentation acting as the independent variables. Unlike many mediation analyses which make use of the PROCESS macro, we opted to use PLS. We argue such an approach to be preferable given that composite structural equation modeling (SEM) methods address the issues experienced with regression and factor-based SEM models (Sarstedt et al., Citation2020). As a first step towards evaluating the mediating effects of phubbing, PLS literature instructs researchers to assess the significance of the indirect and direct effects. The indirect effect associated with the path FoMO → PHUB → EIU was not significant (β = 0.031, p > 0.05), with only the direct effect (FoMO → EIU) being significant (β = 0.153, p < 0.05). According to Nitzl et al. (Citation2016), this type of finding indicates the absence of any form of mediation. As such, and within our sample, phubbing does not mediate the relationship between FoMO and excessive Instagram use. We, therefore, reject our first hypothesis (H1). However, for the path SP → PHUB → EIU we found evidence of a significant indirect effect (β = 0.066, p < 0.05) and a significant direct effect (β = 0.257, p < 0.01) for the path SP → EIU. Given that the sign of the path SP → PHUB → EIU is positive (i.e., complementary), we conclude that phubbing does mediate the relationship between self-presentation and excessive Instagram use. Therefore, H2 is supported. In addition to the above, we also used the bias corrected confidence intervals (CI) to further substantiate the significance of the paths used to test for mediatory effects. This enabled us to provide further evidence as to the significance of the indirect effects associated with the hypotheses we developed. If the CI of a path associated with an indirect effect is found to be non-zero (i.e., does not contain a zero and is thus significant), then an assessment of the significance of the direct effect is also required to determine the mediation type (Zhao et al., Citation2010). See, figure and Table for a complete summary of the path estimates our research models and the hypothesis testing results, respectively.

Table 2. Summary of hypothesis (thus mediation) testing

5. Discussion

Instagram has become a popular choice among social media users. Despite its popularity, extant research on its use (not to mention excessive use) remains limited. To address this, the objective of the current study was to investigate the mediating effects of phubbing; specifically, as a mediator between FoMO and excessive Instagram use, as well as between self-presentation and excessive Instagram use. Our results indicate that phubbing does partially mediate the relationship between self-presentation and excessive Instagram use. This means that we have found evidence to suggest that self-presentation (specifically false self-presentation) increases the likelihood of excessive Instagram usage, mainly through its influence on phubbing. Although our literature searches were unable to uncover similar findings on the mediatory role of phubbing (within a similar context), we were able to find studies that confirmed the direct influence of self-presentation on outcomes related to excessive Instagram use. This study, therefore, confirms the findings of previous studies (Balci & Karaman, Citation2020) that self-presentation is a positively significant predictor of excessive Instagram use. Novita Kalalo (Citation2018) also found self-presentation to significantly influence Instagram addiction—a problem caused by excessive use. This is corroborated by Chen and Kim (Citation2013), who found self-presentation to be positively related to the problematic use of social networking sites. Casale et al. (Citation2015) also found self-presentation to significantly influence addictive behavior—albeit within the context of internet addiction. Furthermore, most studies have investigated the various subscales of self-presentation, rather than pursuing the nature of false self-presentation. This makes our finding of the mediating influence of phubbing on the relationship between false self-presentation and excessive Instagram usage very interesting. Authenticity (i.e., not participating in false self-presentation) is essential to an individual’s psychological well-being, something that is negatively influenced when excessively using Instagram (Bailey et al., Citation2020; Jerrentrup, Citation2021; Wirtz et al., Citation2021). Based on our results, we conclude that false self-presentation may indeed be a major contributor to the excessive use of Instagram; more so than the other subscales that comprise self-presentation as a whole. Given that recent research has found most Instagram users to selectively present overinflated content (Jiang & Ngien, Citation2020), excessive use is likely to remain an issue of concern. We therefore recommend that Instagram investigate ways to encourage platform authenticity. A promising approach is proposed by a recent study into how social norms and nudging could be used to dissuade the posting of false news (Andi & Akesson, Citation2020). For example, Instagram may wish to revise the way in which filters are used on its platform as these may act as enablers of false self-presentation. Although these filters are somewhat limited in their ability to address such authenticity-related problems, we advise Instagram to reduce the number of filters. This does not, however, address the source and type of content posted, which may be altered before posting content. Such problems plague not only Instagram (Mun & Kim, Citation2021), but also other social media platforms (Turel & Gil-Or, Citation2019).

Similar to previous studies (e.g., Balta et al., Citation2020; Błachnio & Przepiorka, Citation2018; Karadaǧ et al., Citation2015), our study also found a positive relationship between problematic Instagram use and phubbing. However, other studies have confirmed that FoMO has a positive association with phubbing (Tandon et al., Citation2022). Research has even documented that FoMO is one of the most important predictors and an antecedent of phubbing behavior (Balta et al., 2018; Davey et al., Citation2018; Lai et al., Citation2016; Van Rooij et al., Citation2018). However, our results did not indicate that phubbing mediates the relationship between FoMO and excessive Instagram use. We did, however, find that both FoMO and phubbing significantly influence excessive Instagram use, with a plethora of studies that confirm the significant relationship between FoMO and a variety of outcomes related to the excessive use of Instagram (e.g., addiction to and problematic use of social media and the internet; Alt & Boniel-Nissim, Citation2018; Rozgonjuk et al., Citation2020; Savci et al., Citation2020; Shen et al., Citation2020; Van Rooij et al., Citation2018). The same applies to phubbing, with recent studies reporting significant relationships with problematic (and addictive) forms of social media use (Chi et al., Citation2022; Davey et al., Citation2018).

Most social media studies do not focus or report on the results of the educational levels of participants as we have done in this study. Rather, most studies looking at education and social media usage focus on the use of the social platform as an educational tool (Carpenter et al., Citation2020; Coman et al., Citation2021). Or, these studies investigate the effect of social media use on students’ academic performance (Al-Rahmi et al., Citation2018; Lambić, Citation2016; Whelan et al., Citation2020). We found evidence to suggest that an individual’s education is significantly related to excessive Instagram use. Specifically, we found that excessive use is prevalent in more educated individuals. Other studies have revealed mixed findings on this relationship. For example, Henzel and Håkansson’s (Citation2021) results confirm ours, that is, that individuals leaving high school were found to be more addicted to social media. The more educated the person, the more they tend to use social media. Adults with a postgraduate degree or more use social media more frequently than those with a high-school education (Perifanou et al., Citation2021). Conversely, Koçak et al. (Citation2021) found no significant relationship between social media addiction and education. Van Deursen et al. (Citation2015) found that participants with low levels of education were using the internet for more hours daily in their spare time than more educated and employed people. Correa (Citation2015) also found that less educated young people tended to use social media more frequently. We conclude that the mixed results could be attributed to the use of many social media platforms as an empirical case as opposed to only one, such as Instagram. The educational-level difference in Instagram usage could also be explained by the fact that more educated participants have greater knowledge and practical experience in technology and, hence, express greater interest in social media platforms. However, these mixed results do confirm that more research in this area needs to be done with generic populations.

6. Limitations and future research

Although our study is limited in terms of sample size (and source), cross-sectional approach, and Instagram-only focus, it does highlight interesting areas for future research. First, we advise future research to use probability sampling, which would allow for certain generalizations to be made. Second, unlike our study, we advise that future research should include smartphone use, possibly as a moderator of the relationships we explored in this study. Third, we advise future research to approach excessive social media use by way of focused experiments. For example, researchers could develop monitoring apps that record not only the frequency and duration of use but also the use of specific features (e.g., engagement metrics such as likes, emoticons, and hashtags). Fourth, and as opposed to our cross-sectional approach, it is advised that future research be conducted longitudinally, an approach that would enable researchers to investigate causal relationships. Even more interesting would be a longitudinal country-based analysis. For example, citizens of collectivistic countries may favour inclusive (and in-person) discussions, as opposed to citizens of individualistic countries (Jiang & Ngien, Citation2020). It is likely that this may directly influence phubbing behavior. Fifth, we also advise future research to investigate the influence of social anxiety as an antecedent of excessive use. As stated previously, the active use of Instagram includes engaging with your followers or friends by liking and commenting. Conversely, the passive use of Instagram focuses on the observation of other users without any engagement (Trifiro & Gerson, Citation2019). Research suggests that such passive use leads to a plethora of problems as alluded to in the introduction. Therefore, future research should use our results to understand how socially anxious individuals communicate in order to better understand the impact of phubbing on socially anxious individuals’ use of social media platforms, specifically the extent to which phubbing prevents such individuals from seeking real-life connections (Al-Saggaf & O’Donnell, Citation2019). We argue this to be an apt approach given that phubbing negatively influences a phubbed conversation partner’s need to belong, self-esteem, meaningful existence, and social control (Chotpitayasunondh & Douglas, Citation2018). These all amplify the negative consequences of phubbing behavior and the excessive use of Instagram (Chotpitayasunondh & Douglas, Citation2018). Sixth, future research could investigate interaction effects. Although we tested for these effects (and found none), the inclusion of additional antecedents (such as social anxiety) may yield interesting interaction effects. For example, it is possible that such research may find that as an individual’s social anxiety increases so does their propensity to phub conversation partners. Having said this, it is possible that our model could be evaluated in its current form with the proviso that different scales (i.e., items) are used for phubbing and self-presentation. In addition, then, our seventh and final recommendation is that further research be conducted on the association between educational level and social media usage. As suggested by Perifanou et al. (Citation2021), usage may be influenced by study field and prior experience on certain social media platforms, but this is still far too unclear.

6.1. Theoretical implications

Despite the limitations, our study provides some significant theoretical implications. First, we advise future research to adopt other theoretical frameworks. For example, selected latent variables from uses and gratification theory could be modeled as moderators within the context of the research model in this study. We argue this to be particularly compelling given that extant research suggests social media to enhance individuals’ desire for instant gratification (Wilmer et al., Citation2017). Second, it would be very interesting to combine the latter latent variables with those from the belongingness hypothesis. We argue this to be an appropriate choice given that the premise of the belongingness hypothesis is that individuals have an innate drive to form significant and long-lasting relationships, one of the fundamental factors that drive social media use (Roberts & David, Citation2020).

6.2. Practical implications

Our study also provides several practical implications. First, social media users should be mindful of the way in which they communicate with others (i.e., not phub conversation partners). This applies specifically to those individuals who knowingly present themselves in an overly positive or false manner. Such behavior (i.e., phubbing) leads conversation partners to feel excluded and ignored. According to the temporal need-threat model of ostracism, such exclusion immediately impairs those being phubbed. Using this model, Nuñez et al. (Citation2020) explain that such impairments are experienced in three consecutive stages: first, a fundamental human need (reflexive) is threatened, then there is a delay in coping (reflective), and ultimately long-term health-related issues result (resignation). Together, these consequences pose a serious threat to the establishment (and maintenance) of healthy relationships. Those victimized by phubbing should therefore point out such behavior and, if not resolved, avoid these conversation partners as part of a long-term coping strategy.

Second, our results inform possible treatment of not only excessive Instagram use, but also those psychological factors and behavior that exacerbate it. For example, and as stated before, if therapists were to evaluate an individual’s levels of false self-presentation, it is likely that such an individual also phubs conversation partners. Effective treatment may not only improve the well-being of the individual who suffers from excessive use, but also those around them as they are subject to less phubbing. In such instances, treatment may, for example, lead to reduced feelings of social exclusion and ostracism, which will improve relationships. This is particularly important within family environments, where phubbing has been found to resemble parental rejection—specifically by those teens who are anxious and absorbed (Liu et al., Citation2021).

7. Conclusion

In this study, we investigated the influence and interactions between three factors with regard to excessive Instagram usage: (1) self-presentation (specifically false self-presentation), (2) FoMO, and (3) Phubbing. Together, these factors and behavioral tendencies provide insights into the excessive use of Instagram. Our results indicate that phubbing acts as a mediator between self-presentation and excessive Instagram use—albeit in a complementary manner. Based on this, we argue that those individuals who display high levels of self-presentation (specifically false self-presentation) are more likely to use Instagram excessively. Moreover, for these individuals, phubbing enables the excessive use of Instagram. Counter to our first hypothesis, we did not find any evidence to suggest that phubbing mediates the relationship between FoMO and excessive Instagram use. We also found a positive relationship between Instagram use and educational level, with excessive use being more prevalent in more educated individuals.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

This study made use of survey data that is not publicly available for ethical reasons.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Karl van der Schyff

Karl van der Schyff (Ph.D. Rhodes University) is a Senior Lecturer at Rhodes University. His research interests include behavioural information security, information privacy, quantitative methods and cyberpsychology.

Karen Renaud

Karen Renaud (Ph.D. University of Glasgow) is a Chancellor’s Fellow at the University of Strathclyde. Her research interests include all aspects of human-centred and behavioural security and privacy.

Juliet Puchert- Townes

Juliet Puchert- Townes (Ph.D. Industrial Psychology Nelson Mandela University) is a Senior Lecturer of Business Management at the University of Fort Hare. Her research interests include human resource selection, psychological assessment, emotional intelligence and leadership.

Naledi Tshiqi

Naledi Tshiqi (B.Sc (Hons) Rhodes University) was a student of Information Systems at Rhodes University. Her research interests include social media, cyberpsychology and psychopathology.

References

- Abbey, J. D., & Meloy, M. G. (2017). Attention by design: Using attention checks to detect inattentive respondents and improve data quality. Journal of Operations Management, 53(1), 63–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2017.06.001

- Al-Rahmi, W. M., Alias, N., Othman, M. S., Marin, V. I., & Tur, G. (2018). A model of factors affecting learning performance through the use of social media in Malaysian higher education. Computers & Education, 121, 59–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2018.02.010

- Al-Saggaf, Y. (2020). Phubbing, fear of missing out and boredom. Journal of Technology in Behavioral Science, 6(2), 352–357. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41347-020-00148-5

- Al-Saggaf, Y., & O’Donnell, S. B. (2019). Phubbing: Perceptions, reasons behind, predictors, and impacts. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies, 1(2), 132–140. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbe2.137

- Alt, D., & Boniel-Nissim, M. (2018). Parent–adolescent communication and problematic Internet use: The mediating role of fear of missing out (FoMO). Journal of Family Issues, 39(13), 3391–3409. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X18783493

- Andi, S., & Akesson, J. (2020). Nudging away false news: Evidence from a social norms experiment. Digital Journalism, 9(1), 106–125. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2020.1847674

- Anshari, M., Alas, Y., Hardaker, G., Jaidin, J. H., Smith, M., & Ahad, A. D. (2016). Smartphone habit and behavior in Brunei: Personalization, gender, and generation gap. Computers in Human Behavior, 64, 719–727. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.07.063

- Bai, Q., Lei, L., Hsueh, F. H., Yu, X., Hu, H., Wang, X., & Wang, P. (2020). Parent-adolescent congruence in phubbing and adolescents’ depressive symptoms: A moderated polynomial regression with response surface analyses. Journal of Affective Disorders, 275, 127–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.03.156

- Bailey, E. R., Matz, S. C., Youyou, W., & Iyengar, S. S. (2020). Authentic self-expression on social media is associated with greater subjective well-being. Nature Communications, 11(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-18539-w

- Balci, Ş., & Karaman, S. Y. (2020). Social media usage, self-presentation, narcissism, and self-esteem as predictors of Instagram addiction: An intercultural comparison. Erciyes Iletisim Dergisi, 7(2), 1213–1239.

- Balta, S., Emirtekin, E., Kircaburun, K., & Griffiths, M. D. (2020). Neuroticism, trait fear of missing out, and phubbing: The mediating role of state fear of missing out and problematic Instagram use. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 18(3), 628–639. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-018-9959-8

- Błachnio, A., & Przepiorka, A. (2018). Be aware! If you start using Facebook problematically you will feel lonely: Phubbing, loneliness, self-esteem, and Facebook intrusion. A cross-sectional study. Social Science Computer Review, 37(2), 270–278. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439318754490

- Brailovskaia, J., Schillack, H., & Margraf, J. (2018). Facebook addiction disorder in Germany. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 21(7), 450–456. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2018.0140

- Busch, P. A., & McCarthy, S. (2021). Antecedents and consequences of problematic smartphone use: A systematic literature review of an emerging research area. Computers in Human Behavior, 114, 1–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106414

- Capilla Garrido, E., Issa, T., Gutiérrez Esteban, P., & Cubo Delgado, S. (2021). A descriptive literature review of phubbing behaviors. Heliyon, 7(5), e07037. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e07037

- Carpenter, J. P., Morrison, S. A., Craft, M., & Lee, M. (2020). How and why are educators using Instagram? Teaching and Teacher Education, 96, 103149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2020.103149

- Carrión, G. C., Nitzl, C., & Roldán, J. L. (2017). Mediation analyses in partial least squares structural equation modeling: Guidelines and empirical examples. In H. Latan & R. Noonan (Eds.), Partial least squares path modeling: Basic concepts, methodological issues and applications (pp. 173–195). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-64069-3_8

- Casale, S., Fioravanti, G., Flett, G. L., & Hewitt, P. L. (2015). Self-presentation styles and problematic use of internet communicative services: The role of the concerns over behavioral displays of imperfection. Personality and Individual Differences, 76, 187–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.12.021

- Chancellor, S., Pater, J., Clear, T., Gilbert, E., & De Choudhury, M. (2016). Thyghgapp: Instagram content moderation and lexical variation in Pro-Eating disorder communities. Proceedings of the ACM conference on computer supported cooperative work, CSCW. San Francisco. https://doi.org/10.1145/2818048.2819963

- Chandler, J., Rosenzweig, C., Moss, A. J., Robinson, J., & Litman, L. (2019). Online panels in social science research: Expanding sampling methods beyond mechanical turk. Behavior Research Methods, 51(5), 2022–2038. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-019-01273-7

- Chen, H. T., & Kim, Y. (2013). Problematic use of social network sites: The interactive relationship between gratifications sought and privacy concerns. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 16(11), 806–812.

- Chen, S., Van Tilburg, W. A. P., & Leman, P. J. (2021). Self-objectification in women predicts approval motivation in online self-presentation. British Journal of Social Psychology, bjso.12485. https://doi.org/10.1111/BJSO.12485

- Chen, X., Wei, S., Sun, C., & Liu, Y. (2019). How technology support for contextualization affects enterprise social media use: A media system dependency perspective. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 62(3), 279–297. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPC.2019.2906440

- Chi, L. C., Tang, T. C., & Tang, E. (2022). The phubbing phenomenon: A cross-sectional study on the relationships among social media addiction, fear of missing out, personality traits, and phubbing behavior. Current Psychology, 1, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/S12144-021-02468-Y/TABLES/5

- Chotpitayasunondh, V., & Douglas, K. M. (2018). The effects of “phubbing” on social interaction. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 48(6), 304–316. https://doi.org/10.1111/jasp.12506

- Chua, T. H. H., & Chang, L. (2016). Follow me and like my beautiful selfies: Singapore teenage girls’ engagement in self-presentation and peer comparison on social media. Computers in Human Behavior, 55, 190–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.09.011

- Çikrikci, Ö., Griffiths, M. D., & Erzen, E. (2019). Testing the mediating role of phubbing in the relationship between the big five personality traits and satisfaction with life. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 20(1), 44–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-019-00115-z

- Coman, C., Mesesan-Schmitz, L., Tiru, L. G., Grosseck, G., & Bularca, M. C. (2021). Dear student, what should I write on my wall? A case study on academic uses of Facebook and Instagram during the pandemic. PLOS One, 16(9), e0257729. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.025772

- Correa, T. (2015). Digital skills and social media use: How Internet skills are related to different types of Facebook use among ‘digital natives’. 19(8), 1095–1107. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2015.1084023

- D’Souza, L., & Negahban, M. B. (2019). Instagram virtual network addiction and sleep quality among students pursuing a speech and hearing course. Interdisciplinary Journal of Virtual Learning in Medical Sciences, 10(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.5812/ijvlms.89059

- Davey, S., Davey, A., Raghav, S. K., Singh, J. V., Singh, N., Blachnio, A., & Przepiórkaa, A. (2018). Predictors and consequences of “Internet ” among adolescents and youth in India: An impact evaluation study. Journal of Family & Community Medicine, 25(1), 1–35. https://doi.org/10.4103/JFCM.JFCM_71_17

- Djafarova, E., & Trofimenko, O. (2019). “Instafamous”: Credibility and self-presentation of micro-celebrities on social media. Information Communication and Society, 22(10), 1432–1446. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2018.1438491

- Dwyer, R. J., Kushlev, K., & Dunn, E. W. (2018). Smartphone use undermines enjoyment of face-to-face social interactions. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 78, 233–239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2017.10.007

- Elhai, J. D., Gallinari, E. F., Rozgonjuk, D., & Yang, H. (2020). Depression, anxiety and fear of missing out as correlates of social, non-social and problematic smartphone use. Addictive Behaviors, 105, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106335

- Fabris, M. A., Marengo, D., Longobardi, C., & Settanni, M. (2020). Investigating the links between fear of missing out, social media addiction, and emotional symptoms in adolescence: The role of stress associated with neglect and negative reactions on social media. Addictive Behaviors, 106, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106364

- Fang, J., Wang, X., Wen, Z., & Zhou, J. (2020). Fear of missing out and problematic social media use as mediators between emotional support from social media and phubbing behavior. Addictive Behaviors, 107, 106430. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106430

- Fellesson, M., & Salomonson, N. (2020). It takes two to interact: Service orientation, negative emotions and customer phubbing in retail service work. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 54, 102050. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102050

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104

- Fu, X., Liu, J., Liu De, R., Ding, Y., Hong, W., & Jiang, S. (2020). The impact of parental active mediation on adolescent mobile phone dependency: A moderated mediation model. Computers in Human Behavior, 107, 106280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106280

- Fuster, H., Chamarro, A., & Oberst, U. (2017). Fear of missing out, online social networking and mobile phone addiction: A latent profile approach. Aloma: Revista de Psicologia, Ciències de l’educació i de l’esport Blanquerna, 35(1), 23–30. https://doi.org/10.51698/aloma.2017.35.1.22-30

- Geisser, S., & Eddy, W. F. (1979). A predictive approach to model selection. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 74(365), 153–160. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.1979.10481632

- González-Nuevo, C., Cuesta, M., & Muñiz, J. (2021). Concern about appearance on Instagram and Facebook: Measurement and links with eating disorders. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 15(2), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.5817/CP2021-2-9

- Guazzini, A., Duradoni, M., Capelli, A., & Meringolo, P. (2019). An explorative model to assess individuals’ phubbing risk. Future Internet, 11(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi11010021

- Hair, J. F., Black, W., Babin, B. Y. A., Anderson, R., & Tatham, R. (2010). Multivariate data analysis: A global perspective. Pearson Higher Education.

- Hair, J., Hult, T., Ringle, C., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) (2nd ed. ed.). Sage.

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203

- Harris, B., Regan, T., Schueler, J., & Fields, S. A. (2020). Problematic mobile phone and smartphone use scales: A systematic review. Frontiers in Psychology, 11(672), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00672

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2014). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

- Henzel, V., & Håkansson, A. (2021). Hooked on virtual social life. Problematic social media use and associations with mental distress and addictive disorders. PLOS One, 16(4), e0248406. https://doi.org/10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0248406

- Ivanova, A., Gorbaniuk, O., Błachnio, A., Przepiórka, A., Mraka, N., Polishchuk, V., & Gorbaniuk, J. (2020). Mobile phone addiction, phubbing, and depression among men and women: A moderated mediation analysis. Psychiatric Quarterly, 91(3), 655–668. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11126-020-09723-8

- Jerrentrup, M. T. (2021). Ugly on the internet: From #authenticity to #selflove. Visual Studies, 36(4–5), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/1472586X.2021.1884993

- Jiang, S., & Ngien, A. (2020). The effects of Instagram use, social comparison, and self-esteem on social anxiety: A survey study in Singapore. Social Media and Society, 6(2), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305120912488

- Kadylak, T. (2020). An investigation of perceived family phubbing expectancy violations and well-being among U.S. older adults. Mobile Media and Communication, 8(2), 247–267. https://doi.org/10.1177/2050157919872238

- Karadaǧ, E., Tosuntaş, Ş. B., Erzen, E., Duru, P., Bostan, N., Şahin, B. M., Babadaǧ, B., & Çulha, İ. (2015). Determinants of phubbing, which is the sum of many virtual addictions: A structural equation model. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 4(2), 60–74. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.4.2015.005

- Koçak, O., İlme, E., & Younis, M. Z. (2021). Mediating role of satisfaction with life in the effect of self-esteem and education on social media addiction in Turkey. Sustainability, 13(16), 9097. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13169097

- Krämer, N. C., & Winter, S. (2008). Impression management 2.0: The relationship of self-esteem, extraversion, self-efficacy, and self-presentation within social networking sites. Journal of Media Psychology, 20(3), 106–116. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-1105.20.3.106

- Laato, S., Islam, A. K. M. N., & Laine, T. H. (2020). Did location-based games motivate players to socialize during COVID-19? Telematics and Informatics, 54, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2020.101458

- Lai, C., Altavilla, D., Ronconi, A., & Aceto, P. (2016). Fear of missing out (FOMO) is associated with activation of the right middle temporal gyrus during inclusion social cue. Computers in Human Behavior, 61, 516–521. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.03.072

- Lambić, D. (2016). Correlation between Facebook use for educational purposes and academic performance of students. Computers in Human Behavior, 61, 313–320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.03.052

- Layder, D., & Manning, P. (1994). Erving goffman and modern sociology. The British Journal of Sociology, 45(4), 699. https://doi.org/10.2307/591892

- Li, L., Griffiths, M. D., Mei, S., & Niu, Z. (2020). Fear of missing out and smartphone addiction mediates the relationship between positive and negative affect and sleep quality among Chinese university students. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 877. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00877

- Liu, K., Chen, W., Wang, H., Geng, J., & Lei, L. (2021). Parental phubbing linking to adolescent life satisfaction: The mediating role of relationship satisfaction and the moderating role of attachment styles. Child: Care, Health and Development, 47(2), 281–289. https://doi.org/10.1111/cch.12839

- McDaniel, B. T., & Wesselmann, E. (2021). “You phubbed me for that?” Reason given for phubbing and perceptions of interactional quality and exclusion. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies, 3(3), 413–422. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbe2.255

- Michikyan, M., Dennis, J., & Subrahmanyam, K. (2015). Can you guess who I am? Real, ideal, and false self-presentation on Facebook among emerging adults. Emerging Adulthood, 3(1), 55–64. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167696814532442

- Michikyan, M., Subrahmanyam, K., & Dennis, J. (2014). Can you tell who I am? Neuroticism, extraversion, and online self-presentation among young adults. Computers in Human Behavior, 33, 179–183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.01.010

- Mun, I. B., & Kim, H. (2021). Influence of false self-presentation on mental health and deleting behavior on Instagram: The mediating role of perceived popularity. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 1138. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.660484

- Nazir, T., & Piskin, M. (2016). Phubbing: A technological invasion which connected the world but disconnected humans. International Journal of Indian Psychology, 3(4), 39–46.

- Nitzl, C., Roldan, J. L., & Cepeda, G. (2016). Mediation analysis in partial least squares path modelling, helping researchers discuss more sophisticated models. Industrial Management and Data Systems, 116(9), 1849–1864. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMDS-07-2015-0302

- Niu, G., Yao, L., Wu, L., Tian, Y., Xu, L., & Sun, X. (2020). Parental phubbing and adolescent problematic mobile phone use: The role of parent-child relationship and self-control. Children and Youth Services Review, 116, 105247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105247

- Novita Kalalo, C. (2018). Online self-presentation relationship with Instagram addiction in students of the department of physical education, health and recreation, university of Musamus, Merauke, Indonesia. International Journal of Mechanical Engineering and Technology, 9(10), 288–294. http://iaeme.com/MasterAdmin/Journal_uploads/IJMET/VOLUME_9_ISSUE_10/IJMET_09_10_029.pdf

- Nuñez, T. R., Radtke, T., & Eimler, S. C. (2020). A third-person perspective on phubbing: Observing smartphone-induced social exclusion generates negative affect, stress, and derogatory attitudes. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 14(3), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.5817/CP2020-3-3

- Oberst, U. (2016). New technologies-new disorders? Smartphone use, online social networking, and the fear of missing out. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 5(1), 33–34.

- Perifanou, M., Tzafilkou, K., & Economides, A. A. (2021). The role of Instagram, Facebook, and YouTube frequency of use in university students: Digital skills components. Education Sciences, 11(12), 766.

- Przybylski, A. K., Murayama, K., Dehaan, C. R., & Gladwell, V. (2013). Motivational, emotional, and behavioral correlates of fear of missing out. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(4), 1841–1848. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.02.014

- Reer, F., Tang, W. Y., & Quandt, T. (2019). Psychosocial well-being and social media engagement: The mediating roles of social comparison orientation and fear of missing out. New Media and Society, 21(7), 1486–1505. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444818823719

- Ringle, C., Wende, S., & Becker, J. (2015). SmartPLS. (Vol. 3, No. 3). SmartPLS GmbH.

- Roberts, J. A., & David, M. E. (2020). Boss phubbing, trust, job satisfaction and employee performance. Personality and Individual Differences, 151, 109702. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2019.109702

- Rozgonjuk, D., Sindermann, C., Elhai, J. D., & Montag, C. (2020). Fear of missing out (FoMO) and social media’s impact on daily-life and productivity at work: Do WhatsApp, Facebook, Instagram, and Snapchat use disorders mediate that association? Addictive Behaviors, 110, 106487. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106487

- Salim, F., Rahardjo, W., Tanaya, T., & Qurani, R. (2017). Are self-presentation influenced by friendship-contingent self-esteem and fear of missing out? Makara Human Behavior Studies in Asia, 21(2), 70–82. https://doi.org/10.7454/mssh.v21i2.3502

- Sarstedt, M., Hair, J. F., Nitzl, C., Ringle, C. M., & Howard, M. C. (2020). Beyond a tandem analysis of SEM and PROCESS: Use of PLS-SEM for mediation analyses! International Journal of Market Research, 62(3), 288–299. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470785320915686

- Savci, M., Tekin, A., & Elhai, J. D. (2020). Prediction of problematic social media use (PSU) using machine learning approaches. Current Psychology, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/S12144-020-00794-1/TABLES/4

- Servidio, R. (2019). Self-control and problematic smartphone use among Italian university students: The mediating role of the fear of missing out and of smartphone use patterns. Current Psychology, 7, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00373-z

- Shen, Y., Zhang, S., & Xin, T. (2020). Extrinsic academic motivation and social media fatigue: Fear of missing out and problematic social media use as mediators. Current Psychology, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/S12144-020-01219-9/TABLES/2

- Skogen, J. C., Hjetland, G. J., Bøe, T., Hella, R. T., & Knudsen, A. K. (2021). Through the looking glass of social media. Focus on self-presentation and association with mental health and quality of life. A cross-sectional survey-based study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(6), 3319. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18063319

- Statista. (2021). Facebook MAU worldwide 2021. https://www.statista.com/statistics/264810/number-of-monthly-active-facebook-users-worldwide/

- Stone, M. (1974). Cross-validatory choice and assessment of statistical predictions. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Methodological), 36(2), 111–133.

- Subrahmanyam, K., & Smahel, D. (2011). Digital youth: The role of media in development. Choice Reviews Online. https://doi.org/10.5860/choice.48-5768

- Tandon, A., Dhir, A., Talwar, S., Kaur, P., & Mäntymäki, M. (2022). Social media induced fear of missing out (FoMO) and phubbing: Behavioural, relational and psychological outcomes. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 174, 121149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2021.121149

- Tavakol, M., & Dennick, R. (2011). Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. International Journal of Medical Education, 2, 53–55. https://doi.org/10.5116/ijme.4dfb.8dfd

- Trifiro, B. M., & Gerson, J. (2019). Social media usage patterns: Research note regarding the lack of universal validated measures for active and passive use. Social Media + Society, 5(2), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305119848743

- Turel, O., & Gil-Or, O. (2019). To share or not to share? The roles of false Facebook self, sex, and narcissism in re-posting self-image enhancing products. Personality and Individual Differences, 151, 109506. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2019.109506

- Twomey, C., & O’Reilly, G. (2017). Associations of self-presentation on Facebook with mental health and personality variables: A systematic review. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 20(10), 587–595. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2017.0247

- Van der Schyff, K., Flowerday, S., Kruger, H., & Patel, N. (2020). Intensity of Facebook use: A personality-based perspective on dependency formation. Behaviour & Information Technology. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929X.2020.1800095

- Van Deursen, A. J. A. M., Van Dijk, J. A. G. M., & Ten Klooster, P. M. (2015). Increasing inequalities in what we do online: A longitudinal cross sectional analysis of Internet activities among the Dutch population (2010 to 2013) over gender, age, education, and income. Telematics and Informatics, 32(2), 259–272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2014.09.003

- Van Rooij, A. J., Lo Coco, G., De Marez, L., Franchina, V., & Abeele, M. V. (2018). Fear of missing out as a predictor of problematic social media use and phubbing behavior among flemish adolescents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(10), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15102319

- Vinzi, V., Chin, W., Henseler, J., & Wang, H. (2010). Handbook of partial least squares. Springer.

- Wang, X., Wang, W., Qiao, Y., Gao, L., Yang, J., & Wang, P. (2020). Parental phubbing and adolescents’ cyberbullying perpetration: A moderated mediation model of moral disengagement and online disinhibition. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260520961877

- Whelan, E., Islam, A. K. M. N., & Brooks, S. (2020). Applying the SOBC paradigm to explain how social media overload affects academic performance. Computers & Education, 143, 103692. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2019.103692

- Wilmer, H. H., Sherman, L. E., & Chein, J. M. (2017). Smartphones and cognition: A review of research exploring the links between mobile technology habits and cognitive functioning. Frontiers in Psychology, 8(605), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00605

- Wirtz, D., Tucker, A., Briggs, C., & Schoemann, A. M. (2021). How and why social media affect subjective well-being: Multi-site use and social comparison as predictors of change across time. Journal of Happiness Studies, 22(4), 1673–1691. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-020-00291-z

- Wright, E.J., White, K.M., & Obst, P.L. (2018). Facebook false self-presentation behaviors and negative mental health. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 21(1), 40–49. http://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2016.0647

- Xanidis, N., & Brignell, C. M. (2016). The association between the use of social network sites, sleep quality and cognitive function during the day. Computers in Human Behavior, 55, 121–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.09.004

- Yasin, R. M., Bashir, S., Vanden Abeele, M., & Bartels, J. (2020). Supervisor phubbing phenomenon in organizations: Determinants and impacts. International Journal of Business Communication, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/2329488420907120

- Zhao, X., Lynch, J. G., & Chen, Q. (2010). Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and truths about mediation analysis. Journal of Consumer Research, 37(2), 197–206. https://doi.org/10.1086/651257

Appendix

Table A.1. Questionnaire descriptive statistics

Table A.2. Crossloading values

Table A.3. Heterotrait-monotrait (HTMT) ratio values