Abstract

To investigate the outcomes of men using a community-based suicide prevention service before and during COVID-19 and to understand experiences of therapists for the rapid adaptation and delivery of the service throughout the pandemic. A mixed-methods approach using quantitative and qualitative data to assess the delivery of the intervention before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. The CORE-34 and CORE-10 Clinical Outcome Measures (CORE-OM) were used pre and post intervention to measure clinical change in psychological distress for the men engaged with the service. Six therapist interviews were used to supplement this data for the purposes of understanding the delivery of the service remotely during the pandemic. Data was collected between 1 August 2018 and 1 November 2021 (n = 1115). Interview data were conducted between March and May 2021. Across the cohort, for men who received therapy before (n = 450) or during the pandemic (n = 665), there was a statistically significant reduction in mean psychological distress scores between assessment and end of treatment (p < 0.001). Therapists adapted to delivering the hybrid model and discussed the barriers and facilitators to working this way. This study highlighted the effectiveness of the James’ Place suicide prevention model in saving lives and managing to adapt during a global pandemic.

1. Background

Globally, the COVID-19 pandemic has caused an unprecedented disruption impacting on communities, livelihoods and economies across the world (World Health Organisation [WHO], Citation2020a). The national and devolved governments’ restrictions and guidance throughout the pandemic have been ever-changing in response to the level of the coronavirus present in the various countries and regions of the UK. The World Health Organisation declared the pandemic on the 11 March 2020 (WHO, Citation2020a). Following this, the UK government imposed its first official advice on controlling the virus by announcing the introduction of “social distancing” on 16 March 2020, closure of hospitality on 20 March 2020, and a full nationwide lockdown on the 23 March 2020 (Prime Minister’s Office, Citation2020a).

In England, these restrictions included all schools being closed with education moving to home-schooling, all non-essential workplaces to close or for staff to work from home where possible. The first lockdown lasted seven weeks and then gradually eased from the 10th May, with the guidance changing from “stay at home” to “stay alert” and the “rule of six” mixing outdoors (Prime Minister’s Office, Citation2020b). Restrictions eased for a final time on 4th July, allowing up to two households to mix indoors and the hospitality industry (i.e. hotels, pubs and restaurants) to re-open with social distancing measures in place (Prime Minister’s Office, Citation2020c). containment efforts for the pandemic included social distancing, quarantine and isolation, health care providers were confronted with major challenges in the delivery of care (Wright & Caudill, Citation2020). There are growing concerns about the impact of COVID-19 on suicide and a wide range of interdisciplinary response recognises how the pandemic might heighten the risk of suicide (Gunnel et al., Citation2020); thus, the knowledge about suicide prevention approaches is key. Research is sparse about the adaptation to delivery of suicide prevention services (Moutier, Citation2021; Saini et al., Citation2021; Wasserman et al., Citation2020) and the increased use of telehealth within suicide prevention approaches (Balcombe & De Leo, Citation2021).

With over 800,000 people dying by suicide each year worldwide (World Health Organisation [WHO], Citation2020b), suicide remains a significant, yet preventable, public health risk. Suicide among men is a major public health problem and ecent figures show that men accounted for three quarters (4,903 deaths by suicide) of the 6,507 registered suicides in 2018 in the UK (Office for National Statistics [ONS], Citation2020). Suicide mortality among males in England significantly increased by 14% in 2018 compared to 2017, with a 31% increase of men aged 20–24 years dying by suicide and middle-aged men (40–50 years) accounting for a third of all suicides in England in 2018 (ONS, Citation2020). The COVID-19 pandemic could adversely affect known suicide risk factors such as increase in psychiatric disorders, unemployment, financial stressors, domestic violence and alcohol and drug abuse (Gunnel et al., Citation2020). Social isolation and feelings of loneliness are likely to have increased during the pandemic and have been considered as risk factors of suicide during previous epidemics (Wasserman, Citation1992). People at higher risk of suicide include individuals with pre-existing psychiatric disorders, with previous suicide attempt, males, female victims of intimate partner violence (Bitrus et al., Citation2021), and individuals who have been bereaved during the pandemic (Gunnel et al., Citation2020). Recent prevalence studies show that the impact of the pandemic has resulted in an increase in anxiety, stress and depression in the general population (Salari et al., Citation2020), especially among healthcare workers (Huang & Zhao, Citation2020; Sher, Citation2020) and people with pre-existing psychiatric disorders (Sher, Citation2020). The fear of contagion, isolation, loneliness and physical distancing may exacerbate pre-existing psychiatric disorders and trigger mental health problems in the general population (Gunnel et al., Citation2020). The pandemic is representing a challenge to mental health teams at both primary and speciality care levels, who have subsequently needed to reformulate their practices and develop proficiency to deliver remote assessments, consultations and interventions, wherever possible (Gunnel et al., Citation2020; Royal College of Psychiatrists, Citation2020). It is therefore important to gain an understanding of the processes used by suicide prevention therapists when adapting to deliver remotely. In terms of fidelity, it is also important to gain therapists perspectives of delivering suicide prevention remotely during the pandemic to ensure the content of suicide prevention interventions are transferable and delivered as intended. Remote psychotherapy provided by a distance includes a broad range of technologies encompassing the use of telephones, videoconferencing, and email (Balcombe & De Leo, Citation2021). Suicide prevention care conducted remotely (i.e., via videoconferencing) has rapidly evolved worldwide as a technology for the management of people at risk of suicide (Saini et al., Citation2021), as it enables the direct delivery of real-time therapy. The current situation around the COVID-19 pandemic and the measures necessary to fight it have further accelerated the rapid expansion of remote therapy; however, the benefits of remote suicide prevention therapy are currently unknown.

Digital mental health is in its adolescence, but there is efficacy for digital interventions at the population level as it provides advantages for some populations including: increased accessibility, acceptability, affordability, availability of care, equity, autonomy as well as improved understanding of mental health (Balcombe & De Leo, Citation2021). However, there are also disadvantages with efficacy, insufficient validation of technology, user engagement and retention issues, data security and privacy, digital poverty and marginalisation. More needs to be known about whether telehealth is effective for people receiving psychotherapy for suicide prevention. To date, the evidence suggests that these methods are effective for mild to moderate anxiety and depression and stress, but less is known for suicide prevention interventions (Lai et al., Citation2014).

James’ Place is a suicide prevention community-based service delivering a clinical intervention for men in crisis based in Northwest England. James’ Place delivers an intervention based on three theoretical models: Interpersonal Theory of Suicide (Joiner et al., Citation2009), the Collaborative Assessment and Management of Suicidality (CAMS; Jobes, Citation2012), and the Integrated Motivational-Volitional Theory of Suicide (IMV; O’Connor, Citation2011; O’Connor & Kirtley, Citation2018). All three approaches include working alongside the suicidal person to coproduce effective suicide prevention strategies and safety planning. Partnerships across the city enable men to be referred to James’ Place from emergency departments, primary care, mental health services, local universities, or via self-referrals. Clients were offered the James’ Place model that included approximately ten sessions of therapy; however, the number may fluctuate depending on each client’s individual needs. Experienced suicide prevention therapists deliver the James’ Place model. Following referral and a welcome assessment, men are given three sessions over the first week that involve the assessment formulation stage where therapists assess the risk of the men, in a collaborative way, with a safety plan. The middle three sessions are delivered over 10 days and are more person centred and include behavioural activation, such as relaxation with someone who is really struggling with anxiety, or sleep hygiene. The final three sessions consist of relapse prevention by completing a more in-depth safety plan whereby men reflect on their progress and review what helped them with their recovery. More detailed outcomes for the service are available in two published reports (Saini et al., Citation2021; Saini et al., Citation2020).

Previous studies have reported that although services have adapted to provide continuity of care in mental healthcare since the onset of the pandemic, there was a reduction in patients accessing services, potentially placing a future burden on services (Bauer-Staeb et al., Citation2021). To eliminate the lack of access to mental health services during the pandemic, telehealth has been implemented as a solution within suicide prevention (Saini et al., Citation2021). For example, videoconferencing offers potential for delivering psychotherapy from distance during the COVID19 pandemic, as some evidence indicates comparable outcomes of providing psychotherapy remotely via the internet to in-person psychotherapy (Bashshur et al., Citation2016). Psychotherapists found their experiences with remote psychotherapy to be better than expected but found that this mode was not totally comparable to face-to-face psychotherapy with personal contact, particularly, telephone-based therapy was rated less favourably (Humer et al., Citation2020). Previous studies have focussed upon the experiences and effectiveness of remote therapy at the patient level; however, literature is sparse on therapists’ perspectives of delivering remote therapy (Humer et al., Citation2020), particularly within suicide prevention services. To the best of our knowledge, there are no studies on the views and perspectives of therapists on their experience of the rapid adaptation and delivery of a suicide prevention therapeutic service due to an ongoing public health emergency such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, the current study aimed to investigate the outcomes of men using the service before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, and to understand experience of therapists for the rapid adaptation and delivery of the service during lockdown and the easing of government restrictions.

2. Method

Design: A mixed-methods approach was used for this study. A range of quantitative and qualitative data was collected and analysed to evidence the effectiveness of the James’ Place model and to assess the delivery of the intervention before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. This information was used to explore the demographic information for the men being referred into and engaging with the service and whether the James’ Place model was effective in reducing psychological distress. Data from before and during the COVID-19 pandemic were compared for men using the service before and after the March 2020 lockdown was imposed. Qualitative interviews were used to supplement this data for the purposes of understanding the rapid adaptation of the service and delivery of the therapy remotely.

Participants: Quantitative data was collected from a cohort of men experiencing a suicidal crisis who had been referred to James’ Place between 1 August 2018 to 1 November 2021 (n = 1115). Referrals came from Emergency Departments [ED], Primary Care, Universities, other community settings or self-referrals. Qualitative data was elicited through six in-depth interviews with all therapists at the community-based suicide prevention service (carried out between March and May 2021). Interviews explored therapists’ experiences of the rapid adaptation of the service, delivering the intervention remotely, returning to face-to-face therapy and their perspectives on the men’s engagement and outcomes following the hybrid model that included remote therapy and/or face-to-face therapy.

Procedure for quantitative data collection:

Demographic data

Demographic data was collected from the service data system on all men referred to the service.

The Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) data

The Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) is a measure of relative deprivation for small areas (Lower Super Output Areas [LSOA]). It is a combined measure of deprivation based on a total of 37 separate indicators that have been grouped into seven domains, each of which reflects a different aspect of deprivation experienced by individuals living in an area. Every LSOA in England is given a score for each of the domains and a combined score for the overall index. This score is used to rank all the LSOAs in England from the most deprived to the least deprived, allowing users to identify how deprived areas are relative to others.

Clinical Records

Clinical records were compiled for each of the men referred into the service. Sociodemographic information and precipitating factors for men help-seeking in suicidal crisis were entered into the clinical records from the completed referral forms that were received from referral services or by the men via self-referrals. Therapists completed this information when it was missing and where it was deemed appropriate to collate this for the men. The CORE-34 and CORE-10 (CORE-OM); number of sessions (engagement with sessions); reasons for drop out; and referrals out were included within the clinical records. Records were stored on an online computer system that was updated by service administrators or therapists before or following a session with a client. The data collected are described in more detail below.

CORE-34 and CORE-10 Clinical Outcome Measures (CORE-OM)

Clinical data was collected from before and during covid CORE-34 Clinical Outcome Measure (CORE-OM) scores. The CORE-OM is a client self-report questionnaire, which is administered at the beginning and end of the therapy. The therapists gave the questionnaire to the men at their first session and then at their final session. The client was asked to respond to 34 questions about how they have been feeling over the last week, using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “not at all” to “most of the time”. The 34 items cover four dimensions; subjective well-being, problems/symptoms, life functioning, and risk/harm, producing an overall score called the global distress (GD) score. Comparison of the pre- and post-therapy scores offer a measure of “outcome” (i.e., whether or not the clients level of psychological distress has changed, and by how much). For the CORE-34, scores are presented as a total score (0 to 140) as well as a mean score. Higher scores indicated higher levels of psychological distress, and a total score of 51 or above shows the clinically significant range. Scoring includes less than 20—non-clinical range; 21 to 33—low level distress; 34–50—mild psychological distress; 51 to 67—moderate psychological distress; 68 to 84—moderate-to-severe psychological distress; 85 or above—severe psychological distress.

In September 2020, the CORE-34 was replaced by the validated CORE-10 measure to enable the administration of the questionnaire at more time points. For the CORE-10, scores are presented as a total score (0 to 40) as well as a mean score (between 0–4). Higher scores indicated higher levels of psychological distress, and a total score of 11 or above shows the clinically significant range. Scoring includes: less than 10—non-clinical range; 11 to 14—mild psychological distress; 15 to 19—moderate psychological distress; 20 to 24—moderate-to-severe psychological distress; 25 or above—severe psychological distress.

CORE-OM data are routinely collected by psychological therapy services (Evans et al., Citation2002). Recent research has shown that participants find the CORE-OM useful in assessing psychological distress and progress within treatment (Evans et al., Citation2002). The measures show good reliability and convergent validity with other measures used in psychiatric or psychological settings (Evans et al., Citation2002). Connell et al. (Citation2007) published benchmark information and suggested a GD score equivalent to a mean of 10 or above was an appropriate clinical cut-off, demonstrating a clinically significant change, while a change of greater than or equal to five was considered reliable.

Engagement with Sessions

Engagement with sessions includes men attending a welcome assessment and at least one therapy session. Those who attended a welcome assessment and then no further sessions were classed as incomplete. The number of sessions was determined by the number of times men attended for therapy sessions. This was recorded within their clinical records.

Clinical records from the service were available for the entire sample. Researchers had access to the data, extracted the information, and stored it in excel spreadsheets and SPSS software files to complete the analysis. However, the records only captured entries made in clinical records; unrecorded clinical activity or missing information from referral documents was therefore unavailable. For this study, only the presence of each factor within each client’s clinical records was used for the analysis. It is possible this strategy may have led to underestimation of some factors: for example, sexual orientation. Where clients are noted to have completed the intervention, this indicates that the therapy sessions were attended but does not indicate that the discharge CORE-OM questionnaire was filled in.

Quantitative data analysis: The sample size was predetermined based on the number of men who used the service before and during covid. Data was analysed using SPSS 27 (IBM Corp. Released, Citation2020). To examine client outcomes repeated measures general linear models were used to compare pre and post treatment data. Magnitude of effect sizes were established using the Cohen’s criteria of 0.1 = small effect, 0.3 = medium effect and 0.5 large effect. Descriptive statistics were carried out to illustrate the sociodemographic data of the sample and the precipitating factors for men attending in suicidal crisis. MANOVA’s were conducted to establish differences between groups on the core outcome measures at the beginning and end of the treatment, using baseline characteristics which were significantly different before and during COVID-19 as covariates Referrals were coded as secondary care (mental health practitioners, crisis and urgent care, ED), primary care (GPs, nurses, support workers, improving access to psychological therapies [IAPT], occupational health, and student wellbeing services), self-referrals (individual/family member), and other (voluntary organisations and charities). The index of IMD score ranged between 1 being indicative of the most deprived and 10 the least deprived. Scores of 1–5 indicate the most deprived areas and scores of 6–10 the least deprived areas.

Procedure for qualitative data collection: Prior to the interviews, all participants gave verbal consent. Gatekeeper consent was received from James’ Place prior to data collection from the therapists. Semi-structured interview schedules were used to elicit discussions about the rapid adaptation of the service and remote delivery of the James’ Place model since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. Researchers experienced in qualitative methods conducted one-to-one interviews. The interviews and discussions lasted between 20 to 40 minutes.

Qualitative data analysis: Thematic analysis was used to analyse the six therapist interview transcripts and was selected as an appropriate method for examining the interview data because it provides a way of getting close to the data and developing a deeper appreciation of the content (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). Thematic analysis was used to meet information needs and to provide practical outcomes and recommendations. It offered a highly visible and systematic approach to data analysis, showing very clearly how findings were derived. Analysis followed the five stages of framework analysis; familiarization with the data; identifying a thematic framework; indexing the data; charting the data; and mapping & interpretation. To monitor and limit the possible bias of a single-analyst perspective, additional members of the research team with experience in qualitative methods examined the transcripts to compare their perceptions of the interview data and analysis with the main analyst’s interpretation. All data transcripts were checked for errors by listening back to the audio-recording and reading the transcripts simultaneously. Pooja Saini (PS) and Claire Hanlon (CH) conducted the interviews and listened back to the audio-recorded interviews to become familiar with the whole data set. PS, CH and Jen Chopra (JC) conducted analysis of the anonymised transcripts that have been used within this study.

Patient and Public Involvement: The research question was developed through a collaboration involving the James’ Place Research Steering Group who oversee the research taking place at the centre. The group includes commissioners, clinicians, academics, researchers, therapists, James’ Place staff members and experts-by-experience. Experts-by-experience are men who have personal experience of being in a suicidal crisis or those who have been bereaved by a male suicide. Experts-by-experience are members of the Research Steering Group. Members of the group were involved in choosing the methods and agreeing plans for the dissemination of the study to ensure that the findings are shared with wider, relevant audiences within the field, particularly as some members are part of the National Suicide Prevention Alliance and NIHR Applied Research Collaboration.

Ethical Approval: Ethical approval was granted by the Liverpool John Moores University Research Ethics Committee (Reference: 19/NSP/057) and written consent was gained from men using the service at their initial welcome assessment and verbal consent from those staff who took part in the interviews.

3. Results

3.1. Referrals into the service

Between 1 August 2018 and 1 November 2021, James’ Place received 1115 referrals from ED, Primary Care, Universities, or self-referrals. -Before COVID-19 referrals were between 1 August 2018 and 22 March 2020 (n = 450) and those during COVID-19 were between April 2020 and November 2021 (n = 665). Overall, 479 (43%) of the 1115 men referred to the service attended a welcome assessment and went on to engage in therapy, 88 (8%) men attended the welcome assessment only, 200 (18%) men did not engage with the service following on from their referral, 1 (0.00%) of the men died following their referral into the service but was never seen and 329 (30%) men did not meet the service criteria for therapy and were usually referred to other relevant services (e.g., GP, mental health services, third sector organisations).

shows the engagement with the welcome assessment and therapy for men referred into the service before and during-covid COVID-19. A chi-square test for independence indicated a significant association between before and during COVID-19, and the overall outcome for psychological distress χ2 (6, N = 1095) = 57.85, p < .0001. The mean number of sessions men attended before COVID-19 (5.95) and during COVID-19 (6.36) was 6, ranging between 1–19 sessions. For those

Table 1. Engagement with the service

who did not attend the welcome assessment before and duringCOVID-19, the reason was usually no response when the men were followed-up or some reported not feeling suicidal anymore. The mean age of men was 36 years (range 18–69 years). The mean age of men accessing the service before COVID-19 was 34 years and has risen to 37 years in the during COVID-19 sample.

3.2. Baseline characteristics

Baseline characteristics for men referred into the service are given in . For men attending the service, clinical outcomes differed significantly pre- and during-covid for ethnicity χ2 (3, n = 992) = 42.09, p < .0001, relationship status χ2 (6, n = 934) = 59.86, p < .0001, living situation χ2 (8, n = 684) = 194.93, p < .0001, sexual orientation χ2 (4, n = 702) = 87.16, p < .0001, occupation χ2 (6, n = 975) = 69.99, p < .0001 and by who referred them χ2 (4, n = 1115) = 122.59, p < .0001. No significant differences for clinical outcomes were noted before and during covid for levels of deprivation (p = .45);thus, suggesting that the James’ Place model was just as effective for men across different levels of deprivation.

Table 2. Demographic characteristics of the men help-seeking at James’ Place

3.3. Clinical outcomes

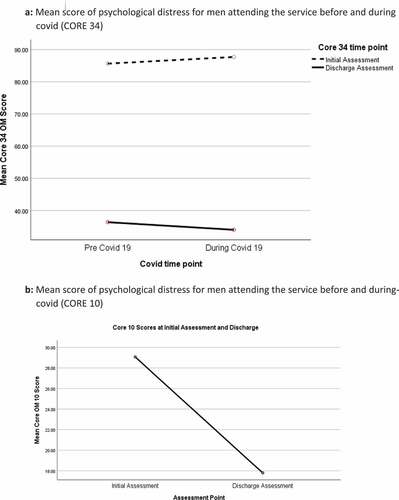

shows the levels of psychological distress at initial assessment and discharge for all men who completed the clinical outcome measures before and during COVID-19. Before COVID-19, 83 (51%) men completed both the initial and discharge CORE 34 measure, and during COVID-19 242 (62%) men completed both the CORE 34 and CORE 10. There were no significant differences between CORE scores at initial assessment and discharge (p = .32). There were also no significant differences between scores before and during COVID-19 (p = .97).

Figure 1. Levels of psychological distress at initial assessment and discharge (CORE 10 and CORE 34).

(a) (CORE 34) and (b) (CORE 10) show that the mean score for most men attending at initial assessment indicated severe levels of psychological distress, with this reducing to mild levels on average at discharge. There was a statistically significant reduction in mean scores for psychological distress for men attending before during COVID-19 between initial assessment and discharge assessment (CORE 34: F (1,149) = 12.27, p = .005, partial eta squared .53; CORE 10: F (1,168) = 10.23, p = .005, partial eta squared .40 when baseline characteristics were controlled for.

3.4. Precipitating factors for men help-seeking in suicidal crisis

Precipitating factors were identified for 298 (66%) men before and for 551 (83%) men during COVID-19. shows the factors related to the suicidal crisis the men were in at the time of referral into the James’ Place service. For men engaged in therapy before COVID-19 (N = 164), 124 (76%) had precipitating factors identified, and during COVID-19 (N = 393), 316 (80%) had precipitating factors identified. Most of the precipitating factors included relationship breakdown or family problems, work or the lack of work, and bereavement (see ). There are differences in precipitating factors recorded before and during COVID-19 that are worth noting. For example, additional factors relating to COVID-19 were added during COVID-19, such as lockdown and COVID-19 related trauma at work. During COVID-19 there was a significant increase in men presenting with housing issues (4% vs. 8%, p = .01), concerns about physical health (although most were not covid related) (4% vs. 11%; p < .001), relationship problems (2% vs. 7%; p = .002), perpetrator of crime (1% vs. 5%; p = .002), victims of past abuse or trauma (7% vs. 16%; p < .001), people experiencing bereavement (not covid related) (13% vs. 18%; p < .001), bereavement by suicide (2% vs. 7%; p < .001), caring responsibilities (0.2% vs. 2%; p = .05), concerns about COVID-19 or lockdown (0% vs. 9%; p < .001), and there was a significant reduction in drug misuse (6% vs. 3%; p = .02) and family problems (23% vs. 1%; p = .02).

Table 3. Precipitating factors to the suicidal crisis for men referred to James Place

3.5. Interview data

Following the thematic analysis process, five inter-related themes were conceptualised as reflecting the corpus of this material. The themes illustrate the areas how the service responded to the COVID-19 pandemic. The first theme related to service delivery moving to remote therapy and was conceptualised as “Preparation for remote working for a suicide prevention service”. The second theme identified was “Experience of men using the James” Place service during the pandemic’ and how the men engaged with remote therapy. The third theme “Challenges for delivering the James Place model remotely” related to the impact of the changing delivery of the James’ Place service. The fourth theme “COVID-19-related concerns” informs on the worries staff had about returning to face-to-face delivery. The final theme “Lessons learned for suicide prevention during the global pandemic” demonstrates what did and did not work when adapting the service delivery model during a global pandemic. Each of these themes is discussed below.

3.6. Theme 1: Preparation for remote working for a suicide prevention service

Findings from the interviews with therapists demonstrated how the James’ Place service adapted and provided a safe and welcoming, hybrid therapeutic setting (from 22 March 2020 with the introduction of remote online consultations until 4 July 2021 when a hybrid model was used for a phased return to face-to-face delivery). Men accessing therapy reported feeling supported and were encouraged to talk about their problems and find solutions. The support and therapy they received appeared to increase their awareness to understand their own thoughts and feelings, and they were able to adopt coping strategies and this in turn had a positive impact upon their mental health and their thoughts around suicide and wanting to act on these.

Whilst there was a sense that lockdown may occur, the lack of Government notice of the lockdown and their uncertainty severely limited preparation time—giving the service approximately a week to prepare to deliver the service remotely;

We did see that it was coming. But literally, it was like everybody was in on the Friday and then that was it. The building was shut for three months. The only person who went in was me, just to make sure it was safe. That we had cancelled the milk, turned off the heating, or just put it on low. I just went in to make sure we weren’t overrun by mice. (P4)

Yes, we all went home on Friday thinking that we could be back in the building, then the whole country shut down. (P1)

Although most aspects of the changes were positive, many staff discussed how the planning of remote delivery was impeded by poor and unclear Government guidance;

I think what was also challenging was that the guidance was so wishy washy. I think that, for a small organisation, we actually spent a lot of time looking at the guidance that was there. So if we had of been a hairdressers, we would have known what to do and if we had of been a restaurant and things like that, but, you know we would have had more guidance. So it was about interpreting the guidance in a way that felt as safe as possible. Our environment leant itself to being able to come back in a way that was safe, I think. The rooms are big and we could have the windows open. We have got the windows open and stuff like that. But it was really challenging, the whole thing. (P4)

Once the lockdown was announced, the service provided staff with the IT equipment to enable them to work from home. One staff member prepared word versions of the “Lay your cards on the table” tool that was previously used within face-to-face sessions via individual cards. Therapists had a role in preparing the transformation of the therapy from face-to-face to online remote delivery; this was perceived positively as they coproduced the changes required. Most of the staff were involved in informing the men of the changes in response to COVID-19, organising caseloads and booking new referrals. Therapists reported how men were receptive to the necessary changes because they were aware of the pandemic and how it was unfolding;

Everyone was very much, because it was all new last year, so everyone was very much, “Yes, of course, of course,” and we just, like, decided whether it was going to be phone or video, and, yes, carried on online. (P1)

Staff reported needing to use video consultants via the service’s “HeyDoc” clinical system for delivering the therapy remotely and how they found this method simple to use. Some therapists had some limited experience of working remotely before the pandemic but most had not done it to this level previously. Some reported having minor network issues at the beginning, but no-one reported them to be a major problem;

Basically they [online appointments] had been booked in and it was just click on the link and it worked and it worked really well. So internet at the point wasn’t so problematic as it seems to be every now and again. It was really good. It just seemed to work really well from the beginning. I didn’t have any technical issues. The men had already been spoken to and prepared for that because I wasn’t doing welcome assessments at the time. So it just seemed to work quite smoothly from my point of view. (P2)

All the therapists commended the administrative team for their role in preparing for remote service delivery. The Clinical Lead played an integral role, along with administrative team, in transferring the James’ Place model from face-to-face to remote delivery;

Admin did brilliant in moving everything from paper copies, kind of thing, to online. (P3)

3.7. Theme 2: Experiences of men using the James’ Place service during the pandemic

Therapists felt the men understood the situation and the need to for the changes, and that the transition was smooth from face-to-face to remote therapy;

It was okay at the beginning, and nobody complained. It was a smooth transition. (P1)

Although the adjustment took a bit of time to get used to for both the men and the therapist;

It was awkward, the usual awkward at the beginning, but it was not, like, the men were a bit awkward as well, but we did get used to it. So, it was okay.

3.7.1. Positives for the men being offered or receiving remote therapy

One of the most reported positives was that the service could continue providing continuity of care for existing clients and supporting men experiencing suicidal crisis during the pandemic. The offer of rapid access to men, which is perceived as a successful element of the James’ Place model, was still applied when providing therapy remotely;

… we were working and the main benefit is that, for the men that we were able to see them, even though remotely, despite everything that was happening, and to us, yes, we continued to work. So, yes, that is the benefit, because our intervention was never meant to be done over video. It is a very much in person intervention. (P1)

I do generally think it worked well and most men didn’t even question, like, “I would have preferred face to face.” It was like, “This is what’s available.” And the feedback from all the men across the board, the thing that they get from us is that rapid access to somebody to talk to, however that’s delivered to them. That, for me, is the key of why this works. It doesn’t matter if it’s telephone, video or in person really. It is a lovely building and it’s a nice place to be but having that person to listen to and talk to within a couple of days or within a day when you’re doing a referral that’s the key thing for us. (P2)

The remote delivery of the service provided increased accessibility for those men who would not typically engage with James’ Place and it provided flexibility that was not otherwise available such as booking sessions around the men’s working commitments or if they were too unwell to attend in person;

if you’re working with a few guys who are employed, they want later appointments it just gave me a bit more flexibility to do that. (P2)

Some men probably did benefit from the fact that it was online and done from their own home. There’s been one, I remember, who said that he’s not sure, and he only lives basically at the bottom of the street where we’re on, and he said that he’s not sure, because of anxiety, not COVID or whatever, but just that going out was a challenge and that. So, he said that he’s not sure if he would engage if it was in person. So for some men, I think it was easier to do it remotely. Some men it wasn’t, some men, kind of, dropped off because they can’t deal with being online or on the phone. (P6)

As illustrated above, remote therapy did not work for all the men. However, some men were anxious to come out to appointments because of COVID-19 and others were shielding, therefore the remote delivery avoided risking unnecessary COVID-19 exposure for some men, particularly those needing to use public transport;

I just think again they chose a time and all they had to do was find a space that was private at home and they could do the session. They didn’t have to travel, they didn’t have to worry about getting on the bus which a lot of our guys do- very few drive. So that safety aspect of keeping themselves safe and people that they were living with who were shield safe was a positive for them. (P5)

You’ve got your ones who were shielding anyway, so they couldn’t leave. Even if we did have that face-to-face service in the building, which I imagine we might have been able to, well, that was shielding. You know, it would be, like, “I can’t help you, because you’re not coming into the office.” So, I suppose if anything, it made our service even more accessible to wider people. People who were shielding, people who might have mobility issues themselves and I’ve got one guy at the moment, and he is agoraphobic. (P3)

3.7.2. Negatives for men being offered or receiving remote therapy

Technology was perceived as a barrier for some men, particularly older men who were not as used to technology or video conferencing. However, they could be accommodated through telephone delivery of the intervention. Therapists suggested that for some of the men, learning how to use technology while also engaging in therapy may have been too burdensome;

… yes, just sometimes they just slowly disengage. There’s not been that, you know, I couldn’t give you any sort of number. There’s been a few, and in my experience the ones that were maybe a little bit older and didn’t want, they did phone, you know? They didn’t do video, they wanted to do phone. Video is the better option out of the two, because you can see the person, but not everyone knows how to do it or has internet, so the ones that were on the phone were usually in their 50s, and not so sure about the internet, and not so sure about therapy. (P1)

Men maybe being in therapy for the first time at the same time as learning some technology for the first time, it can be, yes, maybe too much. (P5)

Lack of accessibility to technology was perceived as a potential barrier for men wishing to access the service. Particularly for the most vulnerable men at risk of suicide who may have been from more deprived backgrounds (e.g., low-SES);

Or they don’t have the tech that would allow them to do it. I suspect that there were people who were not referred to us because the technological barrier of accessing it - that is a challenge. (P5)

Some men struggled to find suitable therapeutic space to receive the intervention at home, especially when they had families;

So I think that having the safe and quiet space to have therapy was quite a challenge for some of the men. I think there is something about the ritual of therapy. (P4)

In some cases, the remote therapy created a different or less formal counselling or therapeutic environment which occasionally blurred the therapist-client relationship. This could become problematic as some men may not have the appropriate space to focus upon the therapy session or arrive at appointments appropriately dressed as they were in their homes. Creating a therapeutic space was described as a challenge for some of the men who preferred face to face, especially for men deeply entrenched in their crisis;

We always have an informal agreement where we do the consent and the data protection information but we had not done anything about this for remote therapy. We therefore had to introduce to the men “This is your appointment time, you need to treat it like appointments, even though you’re in your own home. Please get dressed, please don’t be eating and smoking and doing whatever else you’re doing at the time of the session. (P3)

There was growing evidence of remote or video consultation fatigue among the men as key progress recording tools started being missed or not completed;

I don’t know it really feels like this last month there’s just been this weird shift that they’re not looking at their emails and they’re not following the instructions. I don’t know what that is. I don’t know what that is about. Before that it seemed to be working well. (P2)

It was expressed that the men preferred face-to-face delivery compared to remote delivery of the James’ Place model, although they preferred remote to nothing at all. However, remote delivery made it easier for men to disengage and drop out of therapy;

I think if people didn’t want to attend, they just wanted to disengage, it was easier to just not show up, you just don’t turn on the computer. (P1)

3.8. Theme 3: Challenges for delivering the James Place model remotely

A number of challenges were encountered, and consideration had to be given to not only the delivery of the model itself, but informal aspects of staff management including their confidence to deliver the model remotely;

There were loads of challenges. Some of them were really technical. So, would we be able to do our therapy, which very much is quite visual and collaborative. Would that translate to remote working? We needed to make sure that everybody had phones and that everybody had suitable IT and suitable working environments at home. So some health and safety issues that we needed to address with team members. Trying to make sure that, when you work as part of a team, a lot of that … it always gets called, ‘Informal supervision and informal support.’ It is those, “I just saw a difficult person, have you got two minutes,” or people sitting having lunch and talking about that somebody. So trying to replicate that, or trying to make sure that all the therapists felt supported whilst they were still working. Because I didn’t literally see any of them for about three months, other than on Zoom and phone calls. So it was making sure that everybody felt confident and comfortable. Letting our referrers know. I think it was challenging trying to understand exactly when we should be coming back, because the guidance was … I mean, I knew that NHS services weren’t really coming back, other than A&E-type services, or places delivering physical care. (P4)

It took a bit of time to adjust to changes of delivering the model online in terms of getting familiar with the technology and also working in a home environment;

At the beginning, what I just said, it took some getting used to, because, until now, all I have ever done was face-to-face, apart from when I have to have a conversation on the phone with a client, but that’s not a session, that would be a supporting phone call, but yes, it took a bit of getting used to. Just the whole, kind of, getting around, technology, and, yes, it was just, sort of, working from a different environment. (P1)

Although technology was easy to use, therapists reported having a different experience delivering therapy remotely compared to face-to-face, including staff creating alternative modes of delivery for the cards online;

Yes, technologically it was an easy process to do. It was a different experience in terms of doing the sessions with the men because obviously we didn’t have the physical cards but [colleague name] had put all those on a Word document. So straightaway we had that as well which made it easier. I could just email that to the men and they’d either looked at it or we were looking at it together as we worked through depending what system they were working with. (P2)

It took some time for the therapist to adapt to delivering therapy over the phone as some problems were encountered with the phone provided by the service. For example, hearing the men was difficult at times and making judgements during therapy was difficult in the absence of being able to pick up on non-verbal cues;

It is really hard to hear people on the mobile phones for the first couple of men who didn’t have the technology themselves, so it was telephone calls that were really faint and it was so hard to hear them. I found that particularly difficult but also the silences and the stuff, with the telephone it’s just so hard to judge, am I giving this person enough of a silence? Are they waiting for me to speak? So trying to work with that, silence is quite an important part of counselling. On the telephone you’re a bit, like, “Are you still there?” (P2)

… you’re just like are you still there, sometimes people become quiet when they thinking, sometimes they’re waiting for me to speak, So I’m just going to give you some time if you’re ready to continue let me know.” But it was just trying to get that little bit of patter in while still giving them time to think. The telephone was probably the bit I didn’t feel quite prepared for. At the same time after a couple of sessions it was fine. (P1)

While the therapists preferred the face-to-face mode of delivering the model, they did feel delivering the service remotely worked well in some ways;

Telephone or online is not my first option when working with people therapeutically. But if it’s the only option that you’ve got, I think it worked brilliant.

The therapist felt that the intervention was as effective online versus face-to-face;

… they were mostly, well, not mostly, but yes, it worked. The ones that engaged, it worked for them, and also the ones that we, kind of, transitioned from face-to-face to online, we already had that relationship, so from that aspect it might have been easier because you don’t have to build rapport, but then people who started remote when they had everything from welcome assessment to the end they had online, they didn’t know anything different anyway. So, they didn’t know what it’s like to have a face-to-face therapy at [name of service]. So, I think it was as effective as face-to-face, yes.

One challenge included the nature of the work the therapists do as defining boundaries between work and home was when working from home;

Especially working with the people we work with, it’s not the best thing to have in your living room from 9:00 in the morning to 5:30. (P2)

Trying to help someone who’s suicidal. It’s not as if you just turn your laptop off at 5:30 and put the TV on; “Now I’m back at home.” It doesn’t work that way. (P3)

The service recognised that the nature of the work they do with men may have implications for those therapists with young families (e.g., not wanting them to overhear the content of discussions). However, a positive noted by therapists with children of being at home was that their children benefited from having them home to see more often;

Other people had kids at home. You wouldn’t want your children … it’s not the sort of job you do thinking that the kids are running in and out as well. So I think that that was really tough. I think the same issues would be for the men. So I think that having the safe and quiet space to have therapy was quite a challenge for some of the fellas. I think there is something about the ritual of therapy. (P4)

Therapists reported the challenge of dealing with crisis or emergency situations from home, and how these were perceived as more difficult to manage;

I think when you were dealing with a crisis situation that was harder to do remotely. So if somebody- if you’re trying to encourage somebody, so say somebody came into the building and I wanted them to go to hospital. Now we got a little bit more ability to do that and to negotiate with them because they’re adults. It is negotiating, isn’t it, about autonomy and safety and stuff. That felt a little bit harder to do over the phone, particularly, where you’re like, “I’ve got to contact your supporter and stuff,” and that feeling disjointed and not in as much as- when I’ve done that here before I might be, “I’ll call your supporter while you’re here so you can hear what I’m saying,” and we’re all on the same page about what we’re saying is the next step. “I’m advising you to go to A&E. I told your supporter, they’re going to meet you there.” It was harder to do those kind of parts of it. So the emergency crisis parts, if you like.” (P5)Therapists spoke about a loss of informal social support or incidental peer support. While informal or impromptu support from colleagues was lacking, the therapists’ described receiving strong peer support using WhatsApp which was perceived as just as effective as face-to-face support;

We set up a WhatsApp group; the therapists and [colleague name]. And then if we had any issues, or just needed a bit of extra support, we’d just go on the WhatsApp group, and it was fully supported by the colleagues. (P6)

A negative aspect of the changing environment was that remote delivery of the James’ Place model resulted in “constant meetings” to manage staff, including their wellbeing, health and safety and in navigating the COVID19-guidance;

Yes, so daily catch up meetings, weekly catch up meetings. Things that, like I said, would just happen quite naturally in a building, that we would all get in and say, “What is everybody up to today? How is everybody doing? What are we up to?” That has become a meeting. A daily, a weekly, “How are you going?” I didn’t have a weekly catch up. We had monthly caseload catch ups. So yes, lots of meeting and then lots of meetings about COVID. We put together quite a big risk assessment. At one point, when we were at decision making points and we were waiting for government changes and things, we were having almost daily catch ups about it then. So yes, it is a lot more work. A lot more thinking. We put together a roadmap to get everybody back into the building. Considering there are only six of us, it felt a bit like, “Can’t we just … can’t we all just come back. (P4)

3.9. Theme 4: COVID-19-related concerns

When anticipating a return to the service, a concern reported by therapists was about transmitting COVID-19 to vulnerable family members;

… I wasn’t bothered at all, for me. I was worried about, let’s say, if my mum gets it, it probably won’t be great, but for myself, no. (P2)

The therapists did not feel particularly at risk when working at James’ Place as the service had clear guidelines and policies in place for ensuring a safe working environment. However, they reported feeling that the risk was everywhere, such as when travelling into work or shopping;

Erm, the risk was everywhere, so it didn’t matter. Be it work, supermarket, the school, a bus ride in … (P1)

It wasn’t unique to coming into the office. (P3)

Particularly, therapists reported feeling wary of men who may not stringently adhere to the COVID-19 restrictions. It was difficult to manage risk of COVID-19 from external people to the service or maintain COVID-19 secureness on occasions;

You’re just a bit more wary of other people’s actions than you are your own. I have been so regimental and restricted, and I have stuck to the guidelines. Whereas I’d had a couple of clients, and I’d get “I was at a party last night, at a friends” and I’d be like, “Are you complying? Are you sticking to the COVID guidelines” “Ah, well, I only wear a mask if I have to.” And that kind of thing. So, it was all that kind of thing, I felt safe in myself and my colleagues, but I didn’t feel safe with some of the clients. I just had a client today, and he said he’d socially met up with friends at the weekend. We can’t stop them from doing it.” (P3)

3.10. Theme 5: Lessons learned during the global pandemic

The service has reflected on some of the lessons learned during the lockdown period and through the adaptations they made to enable continued delivery of the service during the pandemic. Some staff reported that the offer of hybrid delivery improved accessibility of the service (i.e., remote and face-to-face) as it could allow some men to access the service who may not be able to do so if it is only delivered face-to-face, particularly offering flexibility and late appointments for men who are working and want to fit the sessions around their work commitments;

I felt it worked really well from the get-go. I was a little bit, I suppose I’m a little bit, kind of- when [colleague name] says, “We’re not going to do a hybrid thing going forward,” I think there are some guys that would benefit from that. I personally don’t feel we should exclude it completely. I think, yes, it should be the exception in the future going forward but I don’t think we should say you’ve got to come in and if you can’t come in, you’re not suitable. (P2)

Another area of learning was to introduce initial conversations with the men to be able to set boundaries appropriate for remote delivery. This was a lesson learnt during first lockdown which was implemented during the second lockdown;

I think the only thing was like I said before when we said about needing to do the ‘ground rules’ and just saying that’s something that we’ve introduced, that was a lesson learned at the time from the first one [lockdown] to the second one. (P3)

In future if a similar situation was to be encountered, therapists perceived it would be helpful to themselves to have create clear work-life boundaries;

… I don’t know, create some sort of, deal with boundaries better. It’s possible, I just don’t know how to. I don’t know if it’s possible, because there’s that factor of children and all that, but I would like to maybe have more defined boundaries for myself between work and home. P1

The lockdown forced the service to consider alternative modes of delivering the service. While this may not be the preferred way to deliver the service, the therapists felt prepared and confident to deliver the James’ Place model remotely. The idea of delivering the therapy remotely had previously been discussed but never prepared for. The pandemic created a necessity to transfer the service online in unprecedented circumstances and highlighted the flexibility of the service to treat men experiencing suicidal crisis remotely, should the need arise again in the future. However, the consensus was that the model is best suited to be delivered face-to-face within the therapeutic setting as this is an integral part of the James’ Place model’s implementation framework;

But I think if this kind of thing happened again, you know, we would be very much prepared … For online, remote therapeutic intervention to go ahead. I think as time went on, it becomes second nature. (P5)

Some hard lessons were learned after the first lockdown, specifically involving and consulting staff on their willingness to return to face-to-face delivery of the James’ Place model;

So it did seem that the nature of our intervention is it is a crisis intervention, so it felt like where there were barriers to men being able to access our intervention online and over the phone, that we should be able to offer them a face-to-face alternative. But then, that was quite challenging, in terms of people feeling comfortable coming back to the building. I think initially, people felt that it was a bit rushed … . It was quite challenging that clearly people felt less willing to come back face-to-face … (P4)

Staff wellbeing was perceived as a priority to ensure the service was delivered effectively; this was reported by all staff interviewed;

Because our wellbeing is just as important as our clients. (P3)

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of main findings

This study investigated the outcomes of men using a community-based suicide prevention service before and during COVID-19, and the experiences of therapists for the rapid adaptation and delivery of the service throughout the pandemic. During COVID-19, significantly more referrals were received from primary care and self-referrals compared to before the onset of the pandemic. Other studies have reported a reduction in patients accessing mental health services for suicide and self-harm during the pandemic (Bauer-Staeb et al., Citation2021). Our findings suggest that men may have consulted more in primary care rather than A&E due to covid risk or that primary care needed other alternatives for referrals for men at risk of suicide. Regarding precipitating factors of the suicidal crisis, our research supports that health and social aspects may increase suicide risk (Gunnel et al., Citation2020); particularly since the onset of the pandemic, such as housing issues (Horne et al., Citation2021), concerns about physical health (Puccinelli et al., Citation2021), relationship problems (Pieh et al., Citation2021), caring responsibilities (Blaney & Saini, Citation2021; Power, Citation2020), concerns related to COVID-19 or lockdown (Almaghrebi Citation2021), were the most common factors within our sample. Similar to other studies (Dunn & Piatkowski, Citation2021; European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, Citation2021), this study reported drug misuse as a precipitating factor less for men arriving in a suicidal crisis than before the pandemic. Although there was a less reporting of family problems during the pandemic, recent research has highlighted that the impact of COVID-19 on families has been different depending on whether they have younger children at home or whether families had good relations prior to the pandemic (Gadermann et al., Citation2021). More research is needed to understand this effect of the pandemic for men who received therapy at the James’ Place centre.

Factors relating to the suicidal crisis and CORE-OM data showed the reduction in psychological distress that the therapeutic intervention provided before and during the pandemic. Similar findings have been reported for the benefits of remote psychotherapy previously (Bashshur et al., Citation2016). The findings of this study indicate that the delivery of the brief psychological therapeutic model was effective in showing a significant improvement in the health of the men arriving in a suicidal crisis to the service when therapy was provided both face-to-face at the centre and remotely online or via telephone. Outcomes identified through the interviews with therapists clearly demonstrate that James’ Place is making a life-changing difference to individuals, their families, their communities, and the wider system. Upon further exploration with the therapists at James’ Place, it was suggested that through the provision of remote support, men accessing the service were able to begin to understand their suicidal thoughts and feelings (through increased awareness and the formation of knowledge) around what had led them to the point of crisis, help them to identify warning signs that their mental health may be worsening, and change the way in which they approached and dealt with (through coping strategies) the distress they were feeling. Although the outcomes for the men were positive via remote therapy, therapists still reported the preference of online videoconferencing to telephone only (Humer et al., Citation2020) and their optimal choice was face-to-face delivery of the suicide prevention therapy, particularly for managing men who may be at increased risk of suicide during a session.

4.2. Remote delivery of the James’ Place model

The themes illustrated the areas of how the suicide prevention service responded to the COVID-19 pandemic and delivered an online remote therapy alternative when face-to-face therapy was not an option. The first theme highlighted how efficiently the suicide prevention service managed to plan a full adaptation of the delivery for a remote service with a vulnerable population. All staff reported being involved and coproducing the management of the men currently engaged with the service and new referrals coming to the service. Therapists relayed their appreciation for the administrative staff and valued the therapy tools that were provided as an online alternative. Although, the community-based suicide prevention service reacted well to the planning, they reported how the government guidelines were at times difficult to navigate and understand for third sector organisations like them. The second theme showed that overall, the therapists felt that men adapted well and seemed to have a positive experience of engaging with the James’ Place service’ remotely. Online therapy enabled staff to continue therapy with men already engaged with the service and in some cases provided more flexibility for men who otherwise may not have attended the service (e.g., men who were working, shielding, or agoraphobic). However, delivering online therapy was more challenging and less accessible to men who were older, men who had less experience of using technology and men who did not have access to technology (e.g., more deprived). The third theme discussed the challenges staff faced when delivering the James Place model remotely. Technology was one aspect that staff needed to ensure was suitable for telephone therapy. Another challenge was delivering the therapy within their home environment and having less separation from their working day, which involved difficult conversations with men who were in suicidal crisis. There were also issues with ensuring a suitable environment for both the therapist and men to feel comfortable and at ease for therapy to take place. The fourth theme highlighted the COVID19-related concerns staff had generally in the wider population and for returning to work. Staff were confident about the safety measures at work but were more concerned about increasing COVID-19 related risks for their family members who were shielding, being at increased risk themselves when providing therapy to men who may not be following the guidelines as stringently or being at increased when travelling into work via public transport. The final theme indicates the learning and responsiveness of the service to its therapists and men using the service during the global pandemic.

4.3. Strengths and limitations

Strengths of this study include a large sample size, real-world applicability, use of a mixed-methods approach, and a focus on a key issue of our time. A further strength is that most previous research includes demographic data for people who died by suicide; however, this data included information on men at the time of crisis. Therefore, the findings can be used to establish the provision needed by men within their local support networks in the area. A good example is debt, which affected men attending the service both before and during COVID-19; the service work collaboratively with the local Citizens Advice Bureau to receive referrals for men attending the service. Another strength of this project is that interviews were conducted with therapists who have been delivering the intervention before and during COVID-19. As the data collected for this project is current, some of the findings should reflect current changes in clinical practice due to the global pandemic and social distancing rules that are continuously changing due to the emergence of new strains of the virus. However, the findings in this study should be interpreted in the context of some methodological limitations as the results may not be representative of the rest of the UK since data were collected in one area where the service is situated. However, many of the issues identified are likely to apply across other areas. One limitation to consider is the reduction of missing or unknown data for men who attend the service. Currently, this data is collected from information completed by referrers on the referral form. The service may therefore look at collating this information within the initial assessment completed at James’ Place. Although analyses have been conducted with a large sample, the findings are based on one psychological distress measure that was collected at two timepoints. Thus, interpretations of these findings should be made with caution.

4.4. Future implications

This study has highlighted the effectiveness of the James’ Place model in supporting men experiencing suicidal crisis before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Recommendations would include using the remote-delivery model as the basis for implementing the service in other settings if the need were to arise. Future research is needed to assess the long-term effects of the model to understand whether a reduction in psychological distress following remote therapy was as sustainable as face-to-face therapy over time.

In a time of great uncertainty and danger, resources are needed to help staff manage people who may find themselves in a suicidal crisis. With the requirement for remote therapy, new and old technologies are needed to be implemented without delay and put into action. Barriers such as maintaining confidentiality requirements, lack of technology expertise, need to be addressed for any future situations that may arise. In an encouraging sign, the findings suggest that the suicide prevention service responded well and provided the same level of high-quality care that they did face-to-face. Some services, like James’ Place are developing training for their staff to increase expertise in conducting suicide risk assessments and delivering interventions remotely (e.g., by telephone or online). These new working practices could be implemented more widely, but with the consideration that not all patients will feel comfortable interacting this way as they may present implications for privacy.

Making remote therapy available at scale when needed due to public health emergencies such as the COVID-19 pandemic, could benefit population mental health and reduce suicide risk. People in suicidal crisis might not seek help due to worrying about face-to-face appointments putting them at risk. The key learning from this suicide prevention service is the appropriate and timely, staff training to support new ways of working, such as for conducting remote assessments and delivering therapy for men who were in suicidal crisis. COVID-19 presents a new and urgent opportunity to focus investments on the vital imperative of suicide prevention. Suicide prevention in the COVID-19 period requires addressing not only pandemic-specific suicide risk and protective factors, but also pre-pandemic risk and protective factors. This study has provided an opportunity for those factors to have been investigated and evidence-based strategies to be reported for clinicians and health care delivery systems, along with national and local policy and educational initiatives tailored to the COVID-19 suicide prevention environment. Learning from this study could significantly mitigate the pandemic’s negative effects on suicide risk if more rapid access to community-based suicide prevention psychotherapy is provided.

Author contributions

Substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work: P.S., J.C. and J.E.B.; acquisition of the data: P.S., J.C., and J.E.B.; data extraction: P.S., J.C. and C.A.H.; statistical analyses: J.C.; interpretation of the data: P.S., J.C., C.A.H. and J.E.B.; drafting the work: P.S., and J.C.; revising the work critically for important intellectual content: P.S., J.C., C.A.H. and J.E.B.; final approval of the version to be published: P.S., J.C., C.A.H. and J.E.B.; agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work: P.S., J.C., C.A.H. and J.E.B. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted. P.S. and J.E.B. act as guarantors. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the staff at James’ Place Liverpool and Anna Hunt for their help during the study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Restrictions apply to the availability of these data. Data was obtained from James Place Liverpool and anonymised datasets are available from the authors with the permission of James Place Liverpool.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Pooja Saini

Pooja Saini is a Chartered Psychologist and Reader in Suicide and Self-Harm Prevention at Liverpool John Moores University. Pooja is well published in the field of suicide and is currently the Lead Researcher for the first non-clinical community-based centre for men in suicidal crisis. Pooja currently leads LJMU Suicide and Self-Harm Research Group and is the Co-Chair for the International Association for Suicide Prevention Special Interest Group “Suicide Prevention in Primary Care”. Her work within suicide includes public engagement, knowledge exchange, implementation science, as well as expertise in both quantitative and qualitative research methods. [email protected]

References

- Almaghrebi, A. H. (2021). Risk factors for attempting suicide during the COVID-19 lockdown: Identification of the high-risk groups. Journal of Taibah University Medical Sciences, 16(4), 605–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtumed.2021.04.010

- Balcombe, L., & De Leo, D. (2021). Digital mental health challenges and the horizon ahead for solutions. JMIR Mental Health, 8(3), e26811. https://doi.org/10.2196/26811

- Bashshur, R. L., Shannon, G. W., Bashshur, N., & Yellowlees, P. M. (2016). The empirical evidence for telemedicine interventions in mental disorders. Telemedicine Journal and E-health: The Official Journal of the American Telemedicine Association, 22(2), 87–113. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2015.0206

- Bauer-Staeb, C., Davis, A., Smith, T., Wilsher, W., Betts, D., Eldridge, C., Griffith, E., Faraway, J., & Button, K. S. (2021). The early impact of COVID-19 on primary care psychological therapy services: A descriptive time series of electronic healthcare records. EClinicalMedicine, 37, 100939. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.100939

- Bitrus, D.K., Tunde, A.A., Quazeem, Q.D., Victor, E.N., Kazeem, O.A., Ismaeel, Y. (2021). Increased Risk of Death Triggered by Domestic Violence, Hunger, Suicide, Exhausted Health System during COVID-19 Pandemic: Why, How and Solutions. Frontiers in Sociology, 6. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsoc.2021.648395

- Blaney, P., & Saini, P. (2021). Informal families like ours seemed unaccounted for. The Psychologist. ISSN 0952-8229. https://thepsychologist.bps.org.uk/informal-families-ours-seemed-unaccounted

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Connell, J., Barkham, M., Stiles, W. B., Twigg, E., Singleton, N., Evans, O., & Miles, J. N. V. (2007). Distribution of CORE-OM scores in a general population, clinical cut-off points and comparison with the CIS-R. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 190(1), 69–74. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.105.017657

- Dunn, M., & Piatkowski, T. (2021). Investigating the impact of COVID-19 on performance and image enhancing drug use. Harm Reduction Journal, 18, 124. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-021-00571-8

- European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (2021). Impact of COVID-19 on drug markets, use, harms and drug services in the community and prisons: Results from an EMCDDA trendspotter study, Publications Office of the European Union.Retrieved 16 December 2021 from https://www.emcdda.europa.eu/system/files/publications/13745/TD0321143ENN_002.pdf

- Evans, C., Connell, J., Barkham, M., Margison, F., McGrath, G., Mellor-Clark, J., & Audin, K. (2002). Towards a standardised brief outcome measure: Psychometric properties and utility of the CORE-OM. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science, 180(1), 51–60. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.180.1.51

- Gadermann, A. C., Thomson, K. C., Richardson, C. G., Gagne, M., McAuliffe, C., Hirani, S., & Jenkins, E. (2021). Examining the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on family mental health in Canada: Findings from a national cross-sectional study. BMJ Open, 11(1), e042871. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042871

- Gunnel, I. D., Appleby, L., Arensman, E., Hawton, K., John, A., Kapur, N., Khan, M., O’Connor, R. C., Pirkis, J., Appleby, L., Arensman, E., Caine, E. D., Chan, L. F., Chang, -S.-S., Chen, -Y.-Y., Christensen, H., Dandona, R., Eddleston, M., Erlangsen, A., … Yip, P. S. (2020). Suicide risk and prevention during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Lancet Psychiatry, 7(6), 468–471. COVID-19 Suicide Prevention Research Collaboration. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30171-1

- Horne, R., Willand, N., Dorignon, L., & Middha, B. (2021). Housing inequalities and resilience: The lived experience of COVID-19. International Journal of Housing Policy, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/19491247.2021.2002659

- Huang, Y., & Zhao, N. (2020). Generalized anxiety disorder, depressive symptoms and sleep quality during COVID-19 outbreak in China: A web-based cross-sectional survey. Psychiatry Research, 288, 112954. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112954

- Humer, E., Stippl, P., Pieh, C., Pryss, R., & Probst, T. (2020). Experiences of psychotherapists with remote psychotherapy during the COVID-19 pandemic: Cross-sectional web-based survey study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(11), e20246. https://doi.org/10.2196/20246

- IBM Corp. Released. (2020). IBM SPSS statistics for windows, version 27.0.

- Jobes, D. A. (2012). The Collaborative Assessment and Management of Suicidality (CAMS): An evolving evidence-based clinical approach to suicidal risk. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 42(6), 640–653. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1943-278X.2012.00119.x

- Joiner, T. E., Van Orden, K. A., Witte, T. K., & Rudd, M. D. (2009). The interpersonal theory of suicide: Guidance for working with suicidal clients. American Psychological Association.

- Lai, M. H., Maniam, T., Chan, L. F., & Ravindran, A. V. (2014, January). Caught in the web: A review of web-based suicide prevention. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 16(1), e30. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.2973

- Moutier, C. (2021). Suicide Prevention in the COVID-19 Era: Transforming threat into opportunity. JAMA Psychiatry, 78(4), 433–438. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.3746

- O'Connor, R. C. (2011). The integrated motivational-volitional model of suicidal behavior [Editorial]. Crisis: The Journal of Crisis Intervention and Suicide Prevention, 32(6), 295–298. https://doi.org/10.1027/0227-5910/a000120

- O’Connor, R. C., & Kirtley, O. J. (2018). The integrated motivational–volitional model of suicidal behaviour. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 373(1754), 20170268. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2017.0268

- Office for National Statistics (ONS). (2020). Suicides in England and Wales: 2019 registrations. Retrieved December 16, 2021 from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/bulletins/suicidesintheunitedkingdom/2019registrations

- Pieh, C., O’Rourke, T., Budimir, S., & Probst, T. (2021). Relationship quality and mental health during COVID-19 lockdown. PLOS ONE, 16(9), e0257118. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0257118

- Power, K. (2020). The COVID-19 pandemic has increased the care burden of women and families, Sustainability: Science. Practice and Policy, 16(1), 67–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/15487733.2020.1776561

- Prime Minister’s Office (2020a, March). Prime Minister’s statement on coronavirus (COVID-19): 23 March 2020’. UK Government. https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/pmaddress-to-the-nation-on-coronavirus-23-march-2020

- Prime Minister’s Office (2020b, May). Prime Minister’s statement on coronavirus (COVID-19): 10 May 2020. UK Government. https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/pmaddress-to-the-nation-on-coronavirus-10-may-2020

- Prime Minister’s Office. (2020c). Prime Minister’s statement to the House on COVID-19: 23 June 2020. UK Government. https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/primeministers-statement-to-the-house-on-covid-19-23-june-2020

- Puccinelli, P. J., da Costa, T. S., Seffrin, A., de Lira, C. A. B., Vancini, R. L., Nikolaidis, P. T., Knechtle, B., Roseman, T., Hill, L., & Andrade, M. S. (2021). Reduced level of physical activity during COVID-19 pandemic is associated with depression and anxiety levels: An internet-based survey. BMC Public Health, 21(1), 425. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-10470-z

- Royal College of Psychiatrists. COVID-19: Guidance for clinicians. Retrieved September 22, 2020, from: https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/aboutus/responding-to-covid-19/responding-to-covid-19-guidancefor-clinicians

- Saini, P., Chopra, J., Hanlon, C., Boland, J., & O’Donaghue, E. (2021). James’ Place Liverpool Evaluation: Year Two Report. Liverpool John Moores University. Retrieved December 16, 2021, fromhttps://www.jamesplace.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Year-two-Report-Final-September-2021.pdf

- Saini, C., Hanlon, B., & Harrison, T. James’ Place Internal Evaluation: One-Year Report. 2020. https://www.jamesplace.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/James-Place-One-Year-Evaluation-Report-Final-20.10.2020.pdf

- Salari, N., Hosseinian-Far, A., Jalali, R., Vaisi-Raygani, A., Rasoulpoor, S., Mohammadi, M., Rasoulpoor, S., & Khaledi-Paveh, B. (2020). Prevalence of stress, anxiety, depression among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Globalization and Health, 16(1), 57. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-020-00589-w

- Sher, L. (2020). Psychiatric disorders and suicide in the COVID-19 era. QJM: An International Journal of Medicine, 113(8), 527–528. https://doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/hcaa204