Abstract

Research has established an association between disgust propensity and stigmatizing reactions against obese individuals. We conducted two online experiments (n = 544) with the moral machine paradigm to investigate a disgust-related bias against obese humans and animals (cats, dogs). We focused on three different facets of trait disgust: pathogen/core disgust, moral disgust, and self-disgust. Participants were presented with dilemmas consisting of two persons or animals (one non-obese, one obese) crossing a street. The participants had to decide which person (animal) had to be sacrificed by an unavoidable car accident. We calculated logistic regression analyses to estimate the relationship between the three domains of trait disgust, sex, and body mass index (BMI) of the participants and the tendency to sacrifice more obese than non-obese humans/ animals. Participants showed a pronounced obesity bias against humans, which was negatively associated with their BMI and positively with their self-disgust (disgust directed toward physical aspects of the self). The obesity bias against animals was less pronounced and could not be predicted based on disgust variables. This study identified self-disgust as the strongest predictor of negative reactions against obese persons. This finding points to the association between internalized and externalized negative body attitudes.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Obesity is defined by the body mass index (BMI), which is calculated using one’s weight (in kilograms) by the square of one’s height (in meters). According to the BMI classification, a BMI equal to or greater than 30 is obese. This study assessed implicit attitudes (evaluations that occur without conscious awareness) towards obese humans and pets. An adapted version of the Moral Machine task was created where participants had to decide whether an obese or non-obsese person (or animal) had to be sacrificed by an unavoidable car accident. (The Moral Machine has been developed by a group from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, that generates moral dilemmas and collects information on the decisions that people make between two destructive outcomes). Participants showed a pronounced obesity bias: they sacrificed more obese than non-obese persons. Participants with a lower BMI and more negative attitudes toward their own body (self-disgust) tended to sacrifice more obese people.

1. Introduction

Disgust is a multifaceted emotion that can be elicited by a wide range of stimuli. According to several authors (e.g., Rozin et al., Citation2008; Tybur et al., Citation2009), these stimuli can be assigned to broader domains of disgust elicitors, such as “core disgust” (repulsion toward bodily secretions and threatening food), “animal-reminder disgust” (repulsion toward death and dying), “pathogen disgust” (repulsion toward disease-causing agents), and “moral disgust” (repulsion toward immoral behaviors). States of disgust are associated with specific bodily reactions (e.g., nausea) and behaviors, such as avoidance/ withdrawal (e.g., distancing from the disgust elicitor), rejection (e.g., social rejection of people with disgusting behaviors), and elimination (e.g., destruction of a disgust elicitors via hygienic behaviors; Rozin et al., Citation2008).

Disgust is typically elicited by external stimuli in the immediate environment of an individual. However, it can also be triggered by the own person (Schienle et al., Citation2014). Disgust can be directed at one’s appearance and personality (e.g., “my body is revolting”) and/or one’s behavior (“the way I act makes me feel sick”). These two facets of self-disgust are dysfunctional and can be understood as a maladaptive self-focused generalization (or internalization) of the generally adaptive disgust response (Overton et al., Citation2008).

Persons vary in the tendency to feel disgusted known as “trait disgust” or “disgust propensity”. The personality characteristic disgust propensity describes the temporally stable tendency of a person to experience disgust toward external stimuli (Schienle et al., Citation2020). The lasting appraisal of (some features of) the self as repulsive characterizes the trait of self-disgust (Overton et al., Citation2008; Schienle et al., Citation2014).

Research has established an association between state disgust, disgust propensity, and stigmatizing behaviors against obese individuals (Lieberman et al., Citation2012; Vartanian, Citation2010). Vartanian (Citation2010) conducted three studies on obesity-related stigmatization. He showed that disgust toward obesity was the strongest predictor of negative attitudes toward obese people in each of the experiments. Lieberman et al. (Citation2012) examined the relationship between three domains of disgust propensity (pathogen, sexual, moral) and obesity stigma. A greater proneness to experience “pathogen disgust” was associated with more negative attitudes toward obese individuals, however only in females.

Obesity is associated with disgust-related concepts of poor personal hygiene, impaired body function, and disease (Puhl & Heuer, Citation2010). Park et al. (Citation2007) suggested that morphological anomalies such as swellings (changes in size or shape of regions of the body) are potent disgust triggers. These bodily changes (e.g., abscesses) can indicate bacterial and viral infections, which are highly contagious. Thus, obesity appears to share some of the bodily features (e.g., skin swellings, fluid build-up) present in infectious diseases (Park et al., Citation2007). In line with this conception, individuals with chronic concerns about pathogens scored higher on an anti-fat attitude scale (Park et al., Citation2007).

However, overweight and obesity have increased dramatically over the past decades, making larger body sizes more normative and less correlated with the perceived presence of pathogens. Nevertheless, in Western cultures socially prescribed stereotypical body size attitudes still link negative characteristics of a person, such as laziness, and lack of discipline, to larger body size (Puhl & Heuer, Citation2010). These characteristics are negative in terms of the functioning of social groups and may therefore be related to the concept of “moral disgust” (Rozin et al., Citation2008). Moral disgust is elicited in response to persons who have broken social norms or moral codes (Tybur et al., Citation2009). By some people, obesity is viewed as a moral failing (a betrayal of the ingroup for selfish reasons) that constitutes an important threat to public health as well as an economic burden (Ringel & Ditto, Citation2019). Mooijman et al. (Citation2018) have argued that moralization of self-control is a group-oriented process; it may serve to increase self-control success for oneself and regulate self-control success for others. Moreover, moral disgust strengthens ingroup binding via rejection (prejudice, stigmatization) of the outgroup (Vartanian et al., Citation2016).

Limited research exists on whether self-disgust is associated with negative attitudes toward obesity in others. Questionnaire studies have identified positive correlations between body dissatisfaction (Griffiths & Page, Citation2008), a negative body image (Spreckelsen et al., Citation2018; Stasik-O’Brien & Schmidt, Citation2018), the urge to be thin (Marques et al., Citation2021), and self-disgust. Moreover, individuals with eating disorders, such as binge-eating disorder (which is often accompanied by excess body weight) report elevated self-disgust (Ille et al., Citation2014). Self-disgust has been viewed as a component of self-stigmatization, which is a frequent problem among individuals with obesity (Pearl et al., Citation2017). People who experience weight-related prejudice and discrimination by others may internalize these negative attitudes and affective reactions, such as disgust.

Thus, several studies have revealed relationships between negative attitudes toward obesity and different facets of trait disgust. The mentioned studies predominantly used explicit measures to assess these attitudes (e.g., questionnaires). However, obesity bias and associated stigmatization may be better predicted via implicit attitudes, which are less controlled, more emotional, and more closely related to impulsive behavior. Therefore, the present investigation used the moral machine paradigm (Awad et al., Citation2018). This paradigm has been designed to collect data on implicit attitudes toward certain groups of people (e.g., male/female; younger/older) by assessing the moral acceptability of decisions made by autonomous vehicles in situations of unavoidable accidents. We adapted this paradigm and conducted two experiments. For experiment 1, users were presented with a series of dilemmas and had to decide whether an obese or non-obese person crossing a street should be spared or run over by the car. The dilemmas with obese and non-obese individuals were embedded in other dilemmas (e.g., cats, dogs crossing the street) to distract from the aim of the study. The participants were not aware of the fact that the study focused on attitudes toward obesity but they were asked to make spontaneous decisions.

The second experiment focused on obese animals. The users were presented with a series of dilemmas and had to decide whether an obese/ non-obese cat or dog that crossed a street should be spared, or run over by a car. The dilemmas were embedded in other dilemmas (e.g., persons crossing the street) to distract from the aim of the study. Obese animals show the same disgust-relevant physical characteristics as humans (i.e. increase in body size). However, the animal has no responsibility for its excess body weight. Pet obesity can be traced back to the behavior of the pet owner. It has been shown, that owners of obese dogs feed their dogs more often during the day (higher frequency of main meals), give more treats, and exercise less often with their dog than owners of non-obese dogs (Bland et al., Citation2009).

The present study investigated obesity bias and associated discrimination via the implicit task of the moral machine paradigm. We attempted to identify automatic attitudes and negative responses toward obese individuals and the association of these processes with different facets of trait disgust. We hypothesized that core/pathogen disgust, moral disgust, and self-disgust would be positively correlated with the number of sacrificed obese individuals. Moreover, we explored the research question of whether a similar bias would be present against obese animals and whether this bias would also be connected with trait disgust.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

A total of 544 university students were recruited via campus announcements and social network advertisements to participate in an online study, which was conducted between May, 1st, 2020 until December, 31st, 2020. The study had been approved by the local ethics committee of the University. Each participant gave written informed consent.

The sample size was determined based on G*Power (Faul et al., Citation2007) analyses which indicated that 200 participants were needed for a two-tailed logistic regression with an alpha level of .05 along with a power of 0.8.

2.1.1. Experiment 1

A total of 344 individuals completed the online study with two parts (moral machine paradigm, questionnaire assessment). Eight participants were excluded due to unrealistically fast reaction times (reaction time below 2 SDs; M = 2.18 s, SD = .58). The analyzed sample consisted of 336 individuals (240 females, 96 males) with a mean age of 25.99 years (SD = 8.94) and a mean self-reported body mass index (BMI) of 22.57 (SD = 3.51; range: 17–36). The majority of the participants were university students (77 %). The remaining participants had white-collar jobs.

2.1.2. Experiment 2

A total of 200 individuals completed the online experiment. Five participants had to be excluded due to unrealistically fast reaction times (reaction time below 2 SDs; M = 2.14 s, SD = .58) and two additional participants due to missing questionnaire data. The analyzed sample consisted of 193 individuals (130 females, 63 males) with a mean age of 27.87 years (SD = 10.74) and a mean BMI of 23.47 (SD: 4.11; range: 17–41). The majority of the participants were university students (64 %). The remaining participants had white-collar jobs.

2.2. Materials

We assessed three different domains of trait disgust via the following questionnaires:

Disgust Propensity. The brief version of the Questionnaire for the Assessment of Disgust Propensity (QADP_brief; Schienle et al., Citation2020) measures the propensity to experience disgust in various situations with a focus on core/pathogen disgust (e.g., “You smell spoiled food”, “You discover that a friend of yours changes his/her underwear only once a week”, You try to eat monkey meat”). The scale consists of 10 items which are rated on 5-point scales (0 = “not disgusting”; 4 = “very disgusting”). The internal consistency (McDonald´s omega) in the current sample was > .75 in both experiments.

Self-disgust. The Questionnaire for the Assessment of Self-Disgust (QASD; German version; Schienle et al., Citation2014) measures “personal self-disgust” with 9 items (e.g., “I find myself repulsive”, ’I am ashamed of myself’, “I can’t stand myself”) and “behavioral self-disgust” with 5 items (e.g., “Some of my behaviors are repulsive to others”, “I feel humiliated”, I do things that I find disgusting’). The items are rated on 5-point scales (0 = “never”, 4 = “always”. McDonald´s omega for the total scale was > .91 in both experiments.

Moral Disgust. The Moral Disgust Scale (Tybur et al., Citation2009) describes eight social norm violations (e.g., “Intentional lying during a business transaction”, “A student cheating to get good grades”, “Forging another person’s signature on a legal document”) which are rated on 7-point scales (0: “not at all disgusting”; 6: “extremely disgusting”). McDonald´s omega was >.88 in both experiments.

2.3. Moral machine paradigm

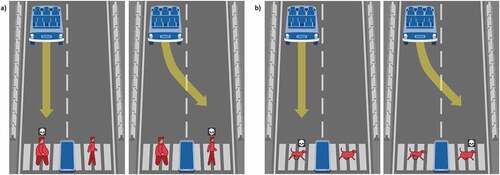

We used the “Moral Machine Paradigm”, which has been designed to collect data on the moral acceptability of decisions made by autonomous vehicles in situations of unavoidable accidents (Awad et al., Citation2018). Users were presented with a series of dilemmas that consisted of two persons/animals (one non-obese, one obese) crossing a street. Obese persons/animals were specifically designed for the study (). A pilot test (n = 50) indicated that the persons/animals were identified as extremely overweight. The users had to decide whether the car drives left or right, so one person/animal would be spared, while the other person/animal would be sacrificed. The verbal instruction of the task was “What should the self-driving car do?”

Before the start of the paradigm, participants were familiarized with the task with four practicing trials. The first two decision intervals were not time-locked, while subsequent decisions were time-locked to four seconds (as in the experiment).

In experiment 1, the participants were presented with eight combinations of an obese and non-obese person crossing the street (left-right/right-left): non-obese female—obese female, non-obese male—obese male, non-obese female—obese male, non-obese male—obese female. Additionally, 12 combinations (e.g., cat—dog; male doctor—female doctor) were used as distractors, resulting in a total number of 20 dilemmas.

In experiment 2, the participants were presented with eight combinations of obese and non-obese pets (one non-obese, one obese) crossing the street (left-right/right-left non-obese cat—obese cat, non-obese cat—obese dog, non-obese dog—obese dog, non-obese dog—obese cat. Additionally, 12 combinations were used as distractors (e.g., non-obese male—female). After the moral machine experiment, each participant completed the questionnaires.

2.4. Statistical analyses

The data analysis focused on the ratio between the number of sacrificed obese persons and non-obese persons (and on the ratio between obese vs. non-obese animals). To compare the count of sacrificed obese persons (animals) relative to non-obese persons (animals) a Wilcoxon signed-rank test for paired samples was computed.

Additionally, we computed binomial logistic regression analyses. Mean centered scores of disgust propensity, self-disgust (personal, behavioral), moral disgust, participants’ BMI, and participants’ sex were used to predict the ratio of sacrificed obese vs. non-obese humans (animals) (1 = more obese than non-obese humans (animals) were sacrificed; the remaining cases were coded as 0).

Furthermore, due to the high collinearity between personal and behavioral self-disgust in both experiments (r1: .84, r2: .82), personal self-disgust scores were residualized (García et al., Citation2020). Residualization did neither change the overall model fit nor the estimates/p-values of the other non-residualized predictors.

We computed the analyses (experiment 1) for the complete set of eight dilemmas (including combinations of persons with different sex crossing the street), and a subset of four dilemmas including comparisons with persons of the same sex (e.g., obese vs. non-obese female; obese male vs. non-obese male crossing the street). A similar analysis approach was used for experiment 2 with eight dilemmas (comparisons of different species) and four dilemmas (comparisons of same species: obese cat vs. non-obese cat; obese dog vs. non-obese dog).

In both experiments the majority of participants completed the total set of dilemmas (experiment 1: four dilemmas: 83 % (n = 278), eight dilemmas: 77 % (n = 259); experiment 2: four dilemmas: 91 % (n = 176), eight dilemmas: 87 % (n = 168)). In experiment 1, two individuals had to be excluded from the analyses of the four dilemmas due to missing data.

3. Results

3.1. Questionnaire data

Descriptive statistics for the disgust questionnaires are displayed in . Correlations between the variables can be found in the supplementary material (Table S1).

Table 1. Questionnaire scores

3.2. Moral machine paradigm

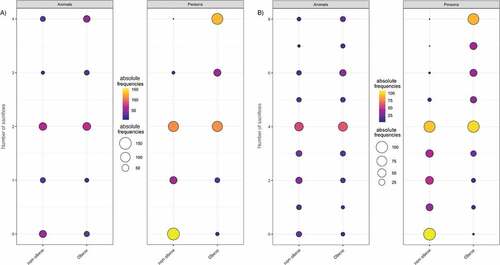

In the first experiment, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test showed that participants sacrificed more obese persons than non-obese persons (). For eight dilemmas, the medians were 5 obese vs. 2 non-obese persons, and the modes were 4 obese vs. 0 non-obese persons, Z = 12.02, p < .001). For four dilemmas, the medians were 3 obese vs. 1 non-obese person, and the modes: 4 obese vs. 0 non-obese persons, Z = 11.53, p < .001).

Figure 2. Absolute frequencies of sacrificed obese/ non-obese animals/humans for four (A) and eight (B) dilemmas.

In the second experiment, the same pattern emerged. A higher number of obese relative to non-obese animals was sacrificed. The obesity bias was less pronounced for animals compared to humans (8 dilemmas: medians: 4 obese vs. 4 non-obese animals, modes: 4 obese vs 4 non-obese animals, Z = 3.31, p = .001, 4 dilemmas: medians: 2 obese vs. 2 non-obese animals, modes: 2 obese vs 2 non-obese animals, Z = 2.75, p = .006; ).

The logistic regression revealed that a lower BMI and higher personal self-disgust were associated with the tendency to sacrifice more obese relative to non-obese persons (four dilemmas). Behavioral self-disgust was linked to the tendency to sacrifice more non-obese than obese persons (). In a second step, we used the residualized personal self-disgust score as the predictor. Then, behavioral self-disgust was not a significant predictor anymore (p = .789), whereas personal self-disgust remained statistically significant.

Table 2. Results of the binomial logistic regression in experiment 1

In experiment 2, the model fit did not reach statistical significance (four and eight dilemmas; p > .125). The number of sacrificed animals could not be predicted based on the selected variables.

4. Discussion

The present study investigated the association between weight bias and different facets of trait disgust (core/pathogen disgust, moral disgust, self-disgust). The participants decided whether a non-obese or obese person (or a non-obese or obese pet) should be sacrificed by an unavoidable car accident in the moral machine paradigm.

In the first experiment, the participants showed a pronounced obesity bias. When analyzing four dilemmas with persons of the same sex crossing the street, the most commonly observed decision pattern (modes) of male and female participants consisted of four sacrificed obese persons, whereas all non-obese persons were spared. This represents the most extreme possible decision pattern. The median ratio of sacrificed obese vs. non-obese persons was 3:1. Very similar, the analysis of eight dilemmas (including comparisons with persons of different sex crossing the street) indicated that the most common decision was to spare all non-obese persons. The median ratio of sacrificed obese vs. non-obese persons was 5:2. Similar findings have been reported in previous studies demonstrating that weight bias and stigmatization associated with obesity are ubiquitous and can be found across different countries, age, and sex groups (Lieberman et al., Citation2012; Park et al., Citation2007; Puhl et al., Citation2015; Schwartz et al., Citation2006; Vartanian, Citation2010).

The tendency to sacrifice more obese than non-obese individuals was correlated with the reported self-disgust of the participants. Those, who experienced aversion directed against their own body, sacrificed more obese persons in the moral machine paradigm compared to those who felt no self-disgust. A study by Palmeira et al. (Citation2019) that explored the relationship between self-disgust and eating psychopathology, tested whether self-compassion mediated this relationship. The computed path analysis showed that the effect of self-disgust on eating psychopathology occurred through the inability to be self-compassionate. It is possible that self-disgust not only reduces self-compassion but also compassion for others.

Kahan and Puhl (Citation2017) discussed the damaging effects of weight bias internalization, which is defined as holding negative beliefs about oneself due to weight or size. They suggested that individuals with obesity may internalize weight-biased attitudes, leading to self-directed shaming and stereotypes about themselves. Thus, the externalized bias (negative attitudes against, and beliefs about others because of their weight) can be directed against the own person. In the present investigation, the devaluation of one’s own body was very likely transferred to obese individuals in the moral machine paradigm. Thus, influences of internalized /externalized negative body attitudes seem to be bi-directional.

The logistic regression also showed that participants with a lower self-reported BMI tended to sacrifice more obese persons compared to those with a higher BMI. Previous research has shown that one’s body weight and attributions about the causes and controllability of bodyweight appear to predict weight bias (Carels & Musher-Eizenman, Citation2010; Puhl et al., Citation2015; Schwartz et al., Citation2006). For example, a large online study (n = 4283) on implicit and explicit anti-fat attitudes and obesity stereotypes (Schwartz et al., Citation2006) showed that thinner people were more likely to automatically associate negative attributes (bad character, laziness, reduced motivation) with obesity. A substantial proportion of respondents indicated a willingness to endure aversive life events or even give up years of their life to avoid being obese. In the present investigation, thinner respondents were more willing to give up years of the life of another person, if that person was obese.

We were not able to replicate the finding by Lieberman et al. (Citation2012) that pathogen disgust is associated with weight bias, as indicated by the tendency to sacrifice more obese persons in the moral machine paradigm. Some authors (e.g., Park et al., Citation2007) have suggested that obesity shares bodily features of infectious disease (e.g., swellings; fluid build-up). However, it seems not difficult to differentiate between typical physical indicators of obesity (e.g., increased waist circumference) and infection-related increase in body size (e.g., swollen extremities). Moreover, infection is typically accompanied by further signs of disease (e.g., skin rash, fever) that are not present in obesity.

It is also possible that the decisions in the moral machine paradigm were not (only) driven by disgust-related motivations but utilitarianism. The participants may have decided to sacrifice more obese individuals to save years of life, considering that severe overweight reduces life expectancy. This interpretation is consistent with the observation that young people are more likely to be saved than older people in the original moral machine paradigm (Awad et al., Citation2018).

Very interestingly, the obesity bias expressed against pets (cats, dogs) was less pronounced compared to the bias against humans. This might be an effect of different body norms for humans and animals. While most cultures have strict norms about the socially acceptable size of human bodies, this is less true for other species. Pet owners even think that being overweight reflects the good life of their chubby and cute animals (Teng et al., Citation2020).

None of the selected facets of trait disgust was able to predict an obesity bias for animals. As mentioned before, a pet is not responsible for having gained excess body weight. The owner overfeeds and under-exercises the pet. Moreover, Pretlow and Corbee (Citation2016) postulate that pet obesity results from overfeeding to obtain affection from the animal. Thus, obesity in pets acquires a positive connotation; it reflects the love of the pet owner. This very likely reduced the weight bias against the animal (Puhl et al., Citation2015). It is also important to note that animal obesity does not pose any threat to (human) group functioning, which is the relevant factor for the elicitation of moral disgust.

We need to mention the following limitations of the present study that was not preregistered. The sample predominantly consisted of students. Therefore, the findings cannot be generalized to other groups. The participants reported low to moderate levels of trait disgust, on average. This is typical for a healthy student sample.

Considering these shortcomings, future research should be conducted with participants displaying more extreme levels of trait disgust. This can be found in clinical groups (e.g., patients with eating disorders). Moreover, different degrees of overweight in the displayed humans/ animals could be integrated into the paradigm to investigate the influence of this factor on decision making. Finally, the effect of intervention programs to reduce implicit obesity bias and associated stigmatization could be tested. For example, the moral machine paradigm could be conducted before and after a public health program to counteract discrimination against obese individuals.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (16 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Datasets are available on the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/4hzgr/)

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/23311908.2022.2090077

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Anne Schienle

Anne Schienle is a professor of Clinical Psychology at the University of Graz, Austria. Her continuing research interests include disgust processing and affective neuroscience.

Albert Wabnegger is a senior scientist for Clinical Psychology at the University of Graz.

References

- Awad, E., Dsouza, S., Kim, R., Schulz, J., Henrich, J., Shariff, A., Bonnefon, J.-F., & Rahwan, I. (2018). The moral machine experiment. Nature, 563(7729), 59–11. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0637-6

- Bland, M., Guthrie-Jones, A., Taylor, R. D., & Hill, J. (2009). Dog obesity: Owner attitudes and behavior. Preventive Veterinary Medicine, 92(4), 333–340. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prevetmed.2009.08.016

- Carels, R. A., & Musher-Eizenman, D. R. (2010). Individual differences and weight bias: Do people with an anti-fat bias have a pro-thin bias? Body Image, 7(2), 143–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2009.11.005

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A. G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program fort he social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39(2), 175–191. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03193146

- García, C. B., Salmerón, R., García, C., & García, J. (2020). Residualization: Justification, properties and application. Journal of Applied Statistics, 47(11), 1990–2010 https:/doi.org/10.1080/02664763.2019.1701638.

- Griffiths, L. J., & Page, A. (2008). The impact of weight‐related victimization on peer relationships: The female adolescent perspective. Obesity, 16(2), 39–45. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2008.449

- Ille, R., Schöggl, H., Kapfhammer, H. P., Arendasy, M., Sommer, M., & Schienle, A. (2014). Self-disgust in mental disorders symptom-related or disorder-specific? Comprehensive Psychiatry, 55(4), 938–943. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2013.12.020

- Kahan, S., & Puhl, R. M. (2017). The damaging effects of weight bias internalization. Obesity, 25(2), 280–281. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.21772

- Lieberman, D. L., Tybur, J. M., & Latner, J. D. (2012). Disgust sensitivity, obesity stigma, and gender: Contamination psychology predicts weight bias for women, not men. Obesity, 20(9), 1803–1814. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2011.247

- Marques, C., Simão, M., Guiomar, R., & Castilho, P. (2021). Self-disgust and urge to be thin in eating disorders: How can self-compassion help? Eating and Weight Disorders – Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity, 26(7), 2317–2324. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-020-01099-9

- Mooijman, M., Meindl, P., Oyserman, D., Monterosso, J., Dehghani, M., Doris, J. M., & Graham, J. (2018). Resisting temptation for the good of the group: Binding moral values and the moralization of self-control. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 115(3), 585–599 https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000149.

- Overton, P. G., Markland, F. E., Taggart, H. S., Bagshaw, G. L., & Simpsons, J. (2008). Self-disgust mediates the relationship between dysfunctional cognitions and depressive symptomatology. Emotion, 8(3), 379–385. https://doi.org/10.1037/1528-3542.8.3.379

- Palmeira, L., Pinto-Gouveia, J., & Cunha, M. (2019). The role of self-disgust in eating psychopathology in overweight and obesity: Can self-compassion be useful? Journal of Health Psychology, 24(13), 1807–1816. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105317702212

- Park, J. H., Schaller, M., & Crandall, C. S. (2007). Pathogen-avoidance mechanisms and the stigmatization of obese people. Evolution and Human Behavior, 28(6), 410–414. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2007.05.008

- Pearl, R. L., Wadden, T. A., Hopkins, C. M., Shaw, J. A., Hayes, M. R., Bakizada, Z. M., Alfaris, N., Chao, A. M., Pinkasavage, E., Berkowitz, R. I., & Alamuddin, N. (2017). Association between weight bias internalization and metabolic syndrome among treatment-seeking individuals with obesity. Obesity, 25(2), 317–322. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.21716

- Pretlow, R. A., & Corbee, R. J. (2016). Similarities between obesity in pets and children: The addiction model. British Journal of Nutrition, 116(5), 944–949 https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114516002774.

- Puhl, R. M., & Heuer, C. A. (2010). Obesity stigma: Important considerations for public health. American Journal of Public Health, 100(6), 1019–1028. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2009.159491

- Puhl, R. M., Latner, J. D., O’Brien, K., Luedicke, J., Danielsdottir, S., & Forhan, M. A. (2015). Multinational examination of weight bias: Predictors of anti-fat attitudes across four countries. International Journal of Obesity, 39(7), 1166–1173. https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2015.32

- Ringel, M. M., & Ditto, P. H. (2019). The moralization of obesity. Social Science & Medicine, 237, 112399. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112399

- Rozin, P., Haidt, J., & McCauley, C. R. (2008). Disgust. In M. Lewis, J. M. Haviland-Jones, & L. F. Barrett (Eds.), Handbook of emotions (3rd ed., pp. 757–776). Guilford Press.

- Schienle, A., Ille, R., Sommer, M., & Arendasy, M. (2014). Diagnostik von Selbstekel imRahmen der Depression. (Diagnostics of self-disgust in depression). Verhaltenstherapie, 24(1), 15–20 http://dx.doi.org/10.1159/000360189.

- Schienle, A., Zorjan, S., & Wabnegger, A. (2020). A brief measure of disgust propensity. Current Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-00883-1

- Schwartz, M. B., Vartanian, L. R., Nosek, B. A., & Brownell, K. D. (2006). The influence of one’s own body weight on implicit and explicit anti-fat bias. Obesity, 14(3), 440–447. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2006.58

- Spreckelsen, P., Glashouwer, K. A., Bennik, E. C., Wessel, I., de Jong, P. J., & Ghosh, S. (2018). Negative body image: Relationships with heightened disgust propensity, disgust sensitivity, and self-directed disgust. PLOS ONE, 13(6), e0198532. Article e0198532. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0198532

- Stasik-O’Brien, S. M., & Schmidt, J. (2018). The role of disgust in body image disturbance: Incremental predictive power of self-disgust. Body Image, 27(7729), 128–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2018.08.011

- Teng, K. T., McGreevy, P. D., Toribio, J. A. L., Dhand, N. K., & Olsson, I. A. S. (2020). Positive attitudes towards feline obesity are strongly associated with ownership of obese cats. PLoS ONE, 15(6), e0234190. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0234190

- Tybur, J. M., Lieberman, D., & Griskevicius, V. (2009). Microbes, mating, and morality: Individual differences in three functional domains of disgust. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 97(1), 103–122 https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015474.

- Vartanian, L. R. (2010). Disgust and perceived control in attitudes toward obese people. International Journal of Obesity, 34(8), 1302–1307. https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2010.45

- Vartanian, L. R., Trewartha, T., & Vanman, E. J. (2016). Disgust predicts prejudice and discrimination toward individuals with obesity. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 46(6), 369–375. https://doi.org/10.1111/jasp.12370