Abstract

The relationship between attitudes and behaviour is largely defined by intentions. The stronger the intention to engage in a behaviour, the greater the likelihood that attitudes will predict that behaviour. In order to predict cohabitation behaviour, both cohabitation attitudes and intentions must be measured. However, to the best of our knowledge, there appears to be a lack of standardized instruments that measure cohabitation intentions and only a few that measure cohabitation attitudes. We therefore set out to develop and validate a Cohabitation Intentions Scale (CIS) in Ghana. The CIS was developed and validated with an existing Cohabitation Attitudes Scale (CAS). The validation process was conducted in two phases: phase I with 226 respondents and phase II with 245 respondents, both from one of the public universities in Ghana. The phase I results necessitated changes to the wording of three items in the CAS and modifications to the rating scales for both the CIS and the CAS. The final instruments contained six items each which were rated on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. Overall, the CIS and the CAS were found to be highly reliable and valid instruments in the Ghanaian context. These findings suggest that the new CIS can be used to measure cohabitation intentions alongside the CAS which measures cohabitation attitudes, and may predict future cohabitation behaviour.

IMPACT STATEMENT

An attempt to predict cohabitation behaviour requires the measurement of both cohabitation attitudes and intentions. Given the existence of instruments which measure cohabitation attitudes, there was a need to develop an instrument that can be used to assess cohabitation intentions. This is the first report of an instrument developed and validated to fill this need.

REVIEWING EDITOR:

Introduction

Cohabitation refers to a consensual non-legal sexual union between two adults who choose to share housing, economic resources, matrimonial duties, and sometimes procreate without performing any marriage ceremony (Calvès et al., Citation2007; Ogunsola, Citation2011; Popoola & Ayandele, Citation2019). In Ghana, there are three types of marriages that are recognized by the state as complete marriages: the Customary or Traditional, Islamic, and Ordinance marriages (Obeng-Hinneh, Citation2018). In a situation where a couple does not follow through with the processes required of any of these forms of marriage, they would legally not be considered married.

Among the Akans who are the most dominant ethnic group in Ghana, cohabitation is perceived to be a phenomenon that undermines cultural values like assuming responsibility, showing commitment, and allowing oneself to be held accountable (Okyere-Manu, Citation2015). Cohabitaion relations are referred to as ‘mpenawadie’, which means a concubine marriage (Okyere-Manu, Citation2015). Due to this perception, attitudes toward cohabitation among Akan indigenes are negative and there is a sense of shame and stigma associated with it. In instances where there are financial constraints, some Akan couples cohabit after ‘knocking’ under the premise that the man would come to complete the rites later (Macaulay, Citation2015). Knocking is a customary tradition where the bridegroom introduces himself formally to his prospective in-laws by sending one bottle of gin to the girl’s father, and another to her Abusua Panyin (the extended family head) or the girl’s mother’s uncle, as the family may require (Kyei, Citation1945). Although Akan culture is not representative of Ghana as a whole, customary marriage rites across all Ghanaian cultures follow a similar script and are held in high esteem. In Sub-Saharan Africa, including Ghana, norms for marriage typically progress from the introduction stage to meetings and background checks between the families involved, then marriage and procreation (Popoola & Ayandele, Citation2019). However, in recent times, financial constraints often determine whether relationships would progress from cohabitation to marriage (Attah, Citation2012).

Cohabitation is a universal phenomenon across different continents and cultures although there are some variations in how it is practiced. In collectivist countries such as Turkey and China, dating and marriage follow a highly formal and traditional script with families inquiring about each other’s background and class to ensure that the couple match each other before non-sexual courtship is approved, and cohabitation relationships are short-lived and not commonplace (Delevi & Bugay, Citation2010; Yu & Xie, Citation2015). On the other hand, people in individualist countries like the United States of America (USA) and European countries, choose their partners, marry for love, or choose to stay in cohabitation for a long period and postpone marriage without fear of stigmatization within their social context (e.g. Delevi & Bugay, Citation2010; Žilinčíková & Hiekel, Citation2018).

Changing trends in cohabitation

The increasing rate of globalization is changing not only traditional social institutions but also people’s values and attitudes toward marriage, what they acknowledge as marriage, and the role of traditional extended families in marriage rituals (Shields-Dutton, Citation2004). Cohabitation relationships are becoming commonplace in contemporary Ghana. Baataar & Amadu (Citation2014) reported that 54% of a sample of tertiary students in Ghana were cohabiting and many of remaining sampled students had intentions to cohabit in future relationships. Statistics from Ghana’s Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) also revealed consistent increases in the rate of cohabitation from 8.1% in 2003 to 13.1% in 2008, and to 14.1% in 2014 (Ghana Statistical Service (GSS) et al., 2015). Similar pattern of increases in the rates of cohabitation has been observed in other parts of Sub-Saharan Africa, particularly in countries like Cameroon, South Africa, Botswana, and Mozambique (Odimegwu et al., Citation2018). For instance, Palamuleni (Citation2010) observed that among 20- to 40-year-old couples in South Africa, there had been a 50% increase in rates of cohabitation. Kamgno & Mengue (Citation2014) also found that cohabitation among women aged 15 to 34 years in Cameroon had increased from 15% in 1991 to 39% in 2004.

In Ghana, the desire to cohabit is heightened especially among college and university students who are exposed to people from various cultures, with varying experiences and beliefs. They may cohabit to test compatibility between partners, discover whether they can deal with conflict within relationships, share financial responsibility, and test their readiness to stay committed to another person (Attah, Citation2012; Manning et al., Citation2007; Rogers et al., Citation2016) or simply due to campus norm. This experience of cohabitation during university years makes a student population especially relevant to cohabitation research that explores attitudes, intentions, and behaviour.

Relationship between cohabitation attitudes, intentions, and behaviours

The relationship between attitudes and behaviours is heavily influenced by a person’s context, societal norms, and the values that endorse certain behaviours whiles sanctioning deviants. Key to this relationship is the influence of intentions, as highlighted in Ajzen’s theory of planned behaviour (Khoo & Ainley, Citation2005). Intentions are the motivational factors that influence a behaviour; they are indications of how hard people are willing to try, of how much of an effort they are planning to exert, in order to perform a behaviour (Ajzen, Citation1991). Therefore, the stronger the intention to engage in a behaviour, the more likely should be its performance. Together, the attitude towards a behaviour, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control, result in the formation of an intention, which in turn leads to the performance of the behaviour (Meijer et al., Citation2016).

Per the theory of planned behaviour, the attitudes an individual has toward marriage and cohabitation by extension, have the potential to affect their decision-making directly or indirectly. Before couples enter a cohabitation relationship, they make evaluations of the advantages and disadvantages of that union, the subjective norms surrounding cohabitation, their evaluations of social perceptions of cohabitation and their compliance with societal norms. They also take consideration of their ability to enter a cohabitation relationship based on the resources available to them and the obstacles they would have to confront. The above factors would inform an individual’s intention to cohabit, which is the proximate determinant of the occurrence of the cohabitation. Although intentions do not perfectly predict behaviour, there is a proven correlation between them (Khoo & Ainley, Citation2005; Manning et al., Citation2014). The theory of planned behaviour, therefore, disputes the idea that the decision to cohabit with one’s partner is not a deliberate one. Rather, couples make deliberate decisions about transitioning to cohabitation (Murrow & Shi, Citation2010).

Quantitative measurement of cohabitation attitudes and intentions

Most studies relating to cohabitation that we found look at how cohabitation relates to marital satisfaction, marital intentions, mental health, sexuality, and the likelihood of divorce among others (e.g. Kasearu, Citation2010; Ogunsola, Citation2011; Stanley et al., Citation2010). Other studies look at cohabitation as part of a larger study that gathered census information relating to the demographics of the people within the study area, notably in the global west. For such studies, often only one or two questions were used to determine respondents’ cohabitation attitude (e.g. Kogan & Weißmann, Citation2020; Rontos et al., Citation2017; Shields-Dutton, Citation2004; Xu & Ocker, Citation2013). Therefore, to the best of our knowledge, there appears to be a dearth of standardized instruments that measure cohabitation attitudes and intentions. The only satisfactory standardized instrument we found that measures cohabitation attitudes was the Cohabitation Attitudes Scale (CAS; Willoughby & Carroll, Citation2012).

As earlier indicated, the relationship between attitudes and behaviour is largely defined by intentions. The stronger the intention to engage in a behaviour, the greater likelihood that attitudes will predict behaviour (Ajzen, Citation1991; Khoo & Ainley, Citation2005). An attempt to predict cohabitation behaviour will require the measurement of both cohabitation attitudes and intentions. Given the existence of the CAS which measures cohabitation attitudes, there is a need to develop an instrument that can be used to assess cohabitation intentions. It is in this light that we developed a new instrument, the Cohabitation Intentions Scale (CIS) to assess cohabitation intentions. We subsequently validated the CIS alongside the existing CAS in the Ghanaian cultural context.

Methods

Study design

This study is part of a larger study that sought to explore university students’ attitudes and intentions toward cohabitation using an exploratory sequential mixed-methods approach. For this part of the study, we used a cross-sectional research approach, which is appropriate for collecting data on the prevalence of behaviours, attitudes, opinions, and intentions at a particular point in time (Connelly, Citation2016). This design is flexible, inexpensive, and can easily be distributed both online and in person.

Participants

Participants were recruited from the undergraduate and postgraduate university student population of one of the public universities in Ghana. The university is a reputable and well-established school worldwide with an estimated number of over 39,249 students who come from varied cultural and socioeconomic backgrounds. A student population was relevant to this study because university students at this stage of their lives are likely to experiment with various social roles (e.g. student, colleague, girlfriend, and daughter) and be faced with having to make independent decisions in ‘real-life’ situations. These decisions may be focused on their romantic relationships and the far-reaching consequences these decisions could create. Two hundred and twenty-six (226) students (128 males and 98 females) were selected to participate in the first phase of the current study using convenience sampling. For the second phase of this current study, 245 students (100 males and 145 females) were selected to participate using convenience sampling.

Instrumentation

Cohabitation intentions scale (CIS)

We developed CIS to address the lack of a parametric instrument that assesses cohabitation intentions. It was evidenced from our literature search that such an instrument was unavailable and therefore there was a need to create one. The CIS is a 6-item scale which measures cohabitation intentions in terms of openness, desire, and plan to cohabit on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (6). The items include the following: ‘I am open to living with my romantic partner before marriage’, ‘I am interested in living together with my romantic partner before marriage’, ‘It makes sense to live with my romantic partner even if we are not yet married’, ‘Nothing prevents me from living with my romantic partner before marriage’, ‘I plan to live with my romantic partner before marriage’ and ‘It is important to me that I live together with my romantic partner before marriage.’ Total scores were computed as the mean of these six items which ranges from 1 to 6, with higher scores indicating a higher intention to cohabit. Upon pretesting, the CIS was found to be highly reliable, with a Cronbach’s alpha of .95 (N = 10).

Cohabitation attitudes scale

The CAS was designed by Willoughby & Carroll (Citation2012) to evaluate three types of attitudes toward cohabitation namely, the belief that cohabitation is beneficial, endorsement of cohabitation with marital plans and endorsement without marital plans. It is a 6-item scale created as a subset of the larger Project Research Emerging Adults Developmental Years (Project READY) questionnaire. Its items include the following: ‘It is a good idea for a couple to live together before getting married as a way of ‘trying out’ their relationship’, ‘Living together first is a good way of testing how workable a couple’s marriage would be’, ‘Living together before marriage will improve a couple’s chances of remaining happily married’, ‘A couple will likely be happier in their marriage if they live together first’, ‘It is all right for a couple to live together without planning to get married’ and ‘It is all right for an unmarried couple to live together as long as they have plans to marry.’ The first four items relate to the belief that cohabitation is beneficial while the last two measured the general endorsement of cohabitation. The items are scored on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (very strongly disagree) to 6 (very strongly agree).

Adaptation of the CAS

The CAS was pilot tested using 10 students to determine its appropriateness to the Ghanaian student sample. This was necessary because the original instrument was developed for use with a Western sample. Results from the pilot testing showed a Cronbach’s alpha of .97 (N = 10) but we noticed from the data collection process that the wording of items 2, 3, and 4 were a bit problematic for most of the participants (n = 7). These participants asked for clarification on what the items really meant while responding to the scale. We therefore changed the wording of these items as shown in . We also changed the scoring of the items to range simply from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (6). To score the scale, participants’ responses were summed with total scores ranging from 6 to 36. The total scores were then averaged to produce a final score that denotes each participant’s overall attitude towards cohabitation. The average scores ranged from 1 to 6, with scores between 1 and 2 denoting negative attitudes, 3 and 4 denoting neutral/moderate attitudes and scores between 5 and 6 denoting positive attitudes.

Table 1. Differences between original and adapted CAS.

Data collection procedure

The first phase of data collection was done in-person and online using Google Forms. For the online administration, a google form link to the questionnaire was circulated through students’ WhatsApp group platforms across all academic levels. For the in-person data collection, the selection of respondents was done in the lecture halls, residential hostels, and academic departments. Students were duly informed, and asked to participate in the study once they confirmed their identity as students and Ghanaians. Only respondents who consented to be part of the study were given questionnaires to complete. Completing the questionnaire took less than 15 minutes per respondent. The total number of respondents assessed in-person was 157.

For the online data collection, the link to the Google Form version of the questionnaire was sent to students who were course representatives for the various academic levels and they in turn shared the link on their various WhatsApp platforms. This online version required respondents to first read information about the study and consent to participating in it before they could proceed to complete the questionnaire. The total number of respondents assessed online was 69. For phase II, the response options for both the CAS-R and the CIS were modified. The modification was necessitated by the results from phase I analyses. The original 6-point Likert response scale was changed to a 7-point Likert response scale. Data was collected for the modified versions of the instruments in the same manner as the first phase.

Ethical considerations

As indicated previously, this current study is part of a larger study which was approved by the Departmental Research and Ethics Committee of the Department of Psychology within the university where the study was set (Protocol number: DREC/010/20-21). The informed consent of respondents was sought for both the in-person and online data collection process for the study. Respondents were assured of confidentiality and the right to discontinue participation at any point during both data collection processes. No compensation was given for participation in the study.

Results

The data on the cohabitation attitudes and intentions scales in phase I and phase II of the study were analyzed separately but the results are presented in a parallel order. The Rasch measurement model was used for the data analysis. First, the psychometric properties of the two scales were analyzed. This was followed by analyses of the rating scales, item analyses, differential item functioning (DIF) analyses, and construct validation analyses.

Psychometric properties

There was greater similarity in the psychometric properties of the cohabitation attitudes and intentions scales in phase I and phase II (see ). The cohabitation attitudes and intentions scales were found to be highly reliable in both phase I and phase II. There was .91 Cronbach’s alpha reliability for the attitudes scale in both phase I and phase II. The intention scale had .95 and .96 Cronbach’s alpha reliabilities in phase I and phase II respectively. The Rasch person and item reliabilities ranged from .78 to .95 for the two instruments. Item separation was high for cohabitation attitudes scale (separation index of 5.47 in phase I and 4.35 in phase II) but low on the intentions scale (separation index of 2.77 on phase I and 1.90 on phase II). Person separation was similar for both instruments and both phase I and phase II. There was lower root mean square error (RMSE) for items than for persons in both studies and for both instruments. For the cohabitation attitudes scale, item RMSE was .08 in study I and .07 in study II compared to person RMSE of .91 in phase I and .83 in phase II. Similarly, the cohabitation intentions scale had an item RMSE of .09 in phase I and .08 in phase II against person RMSE of 1.04 in phase I and .99 in phase II.

Table 2. Reliability, separation, and RMSE statistics of cohabitation attitudes and intentions scale.

Rating scale analyses

The rating scale analysis assessed the extent to which respondents utilized response categories of the rating scale as intended. Two versions of the rating scale were used in the two phases of the study: phase I and phase II. Phase I used a 6-point rating scale with responses ranging from strongly disagree, disagree, somewhat disagree, somewhat agree, agree, and strongly disagree. In phase II of the study, the 6-point rating scale was modified into a 7-point scale by rewording somewhat disagree and somewhat agree response categories into disagree slightly and agree slightly. In addition, a midpoint response category of neither disagree nor agree was added. The midpoint response category was considered a useful link between the negative and positive response categories.

The results of the rating scale analysis for the cohabitation attitudes scale are presented in while presents the results of the rating scale analysis for the cohabitation intentions scale. According to Bond & Fox (Citation2015), the functionality of response categories should be evaluated on a combination of statistical indicators including observed category frequencies, average measures, fit statistics, threshold estimates and category measures. As a requirement for rating scale analysis, it is recommended that each category should have at least a minimum of 10 responses (Linacre, Citation1999). This requirement was met in both phase I and phase II of the study. The least count of category utilization was 92 for strongly agree response category for the cohabitation attitudes scale in phase II.

Table 3a. Cohabitation attitudes rating scale analysis.

Table 3b. Cohabitation intentions rating scale analysis.

A proper functioning rating scale is expected to have monotonic increase in average measures, threshold estimates, and category measure. In both phase I and phase II, average measures and category measures increased systematically. Also, threshold estimates increased systematically for nearly all response categories except for somewhat agree response category in phase I and disagree slightly response category in phase II. While threshold estimates are expected to increase monotonically, disordered thresholds do not pose any threat to polytomous Rasch models, nor do they affect the estimations of Rasch measures or data fitness to the Rasch model (Linacre, Citation1999). In terms of fit statistics, all the response categories were within recommended outfit mean square criterion of ± 2.0 (Linacre, Citation1999). This shows that the two versions of the rating scale are functioning appropriately and can be used interchangeably for the cohabitation attitudes and intentions scale.

Item analyses

The quality of each item in the cohabitation attitudes and intentions scales was assessed based on the Rasch model specifications. Generally, high quality items are those whose infit mean squares range from 0.5 to 1.5; infit mean square of 1 indicates a perfect fit of an item to the Rasch model (Linacre, Citation2012, Citation2020; Linacre & Wright, Citation2002). One item of the cohabitation attitudes scale (COH_ATT5) (see ) and one item of the cohabitation intentions scale (COH_INT4) (see ) had infit mean square beyond the recommended range of 0.5–1.5 in both phase I and phase II. All remaining items had infit mean squares within the recommended range. In terms of item difficulties, item 5 (COH_ATT5) was found to be most difficult while items 1 and 2 (COH_ATT1 and COH_ATT2) emerged as the easiest items on the cohabitation attitudes scale in both phase I and phase II (see ). On the cohabitation intentions scale, items 2, 3 & 4 (COH_INT2, COH_INT3, and COH_INT4) emerged as difficult items while item 1 (COH_INT1) was the easiest in both phase I and phase II (see ).

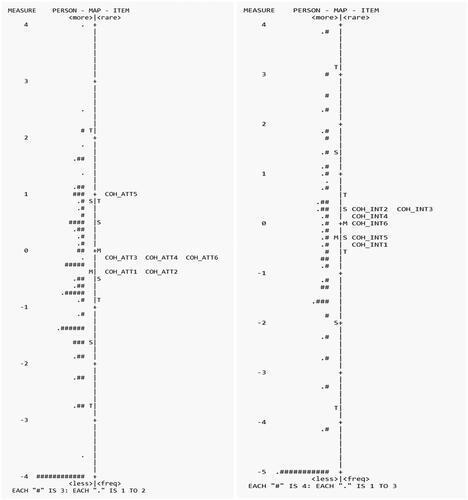

Figure 1. Cohabitation Attitudes and Intentions Scale Item Difficulties on Wright Variable Map – Phase I. Two variable maps displaying variations in item difficulties in Cohabitation Attitudes Scale (CAS) on the left, and Cohabitation Intentions Scale (CIS) on the right. CIS map on the right shows more evenly and hierarchically distributed item difficulties than CAS map on the left.

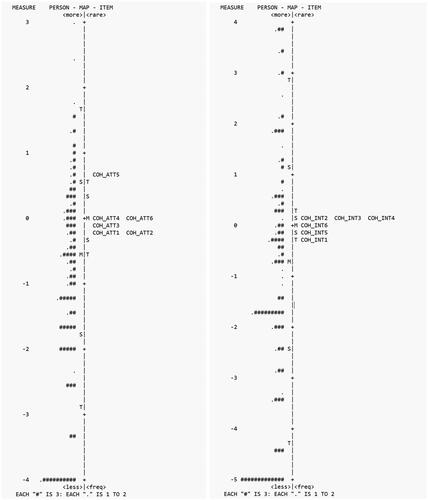

Figure 2. Cohabitation Attitudes and Intentions Scale Item Difficulties on Wright Variable Map – Phase II. Two variable maps displaying variations in item difficulties in Cohabitation Attitudes Scale (CAS) on the left, and Cohabitation Intentions Scale (CIS) on the right. CIS map on the right shows more evenly and hierarchically distributed item difficulties than CAS map on the left.

Table 4a. Cohabitation attitudes scale item analysis.

Table 4b. Cohabitation intentions scale item analysis.

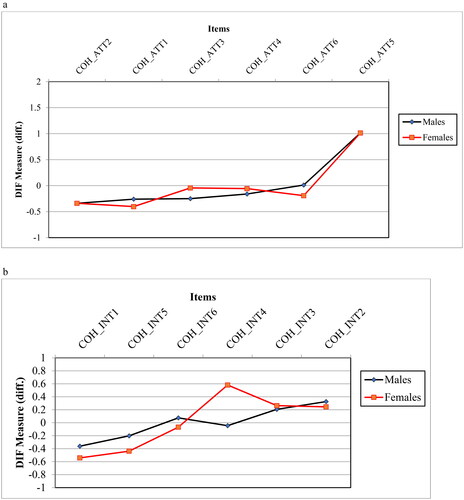

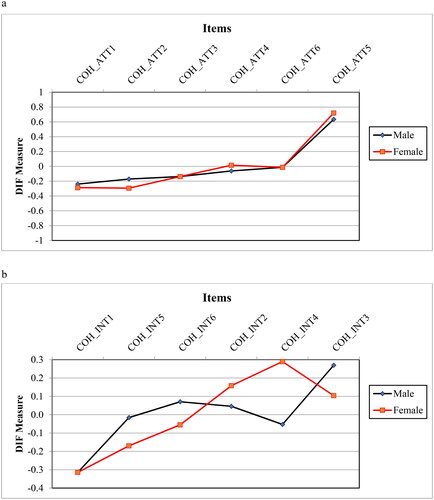

Differential item functioning analyses

Differential item functioning (DIF) was assessed to determine if any of the items functioned differently for male and female respondents. The analyses revealed that all the items in the cohabitation attitudes scale and all but item 4 (COH_INT4) in the cohabitation intentions scale functioned equally for male and female respondents in both phase I and phase II (see ; ). Item COH_INT4 was one of the most difficult items in the cohabitation intentions scale. It had significant DIF contrasts of 0.63 (p = .00) in phase I and 0.34 (p = .03) in phase II. In both situations, the DIF contrast was against female respondents which means that the female respondents found item COH_INT4, Nothing prevents me from living with my romantic partner before marriage, more difficult than did the male respondents. However, using educational testing service classification, the DIF contrast of 0.63 in phase I may be classified as moderate while the DIF contrast of 0.34 in phase II is negligible (Zwick et al., Citation1999).

Figure 3. (a) DIFF Analysis on Cohabitation Attitudes Scale by Gender – Phase I. Male and female curves illustrating lack of differential item functioning (DIF) by gender on all items of Cohabitation Attitudes Scale. (b) DIFF Analysis on Cohabitation Intentions Scale by Gender – Phase I. Male and female curves illustrating significant differential item functioning (DIF) by gender on item 4 of Cohabitation Intentions Scale.

Figure 4. (a) DIFF Analysis on Cohabitation Attitudes Scale by Gender – Phase II. Male and female curves illustrating lack of differential item functioning (DIF) by gender on all items of Cohabitation Attitudes Scale. (b) DIFF Analysis on Cohabitation Intentions Scale by Gender – Phase II.

Male and female curves illustrating significant differential item functioning (DIF) by gender on item 4 of Cohabitation Intentions Scale.

Table 5. Differential item functioning.

Construct validation analyses

Construct validation was conducted through correlation and regression analyses. The Pearson r test was used to correlate cohabitation attitudes and intentions scores. Also, the simple linear regression test was used to regress cohabitation intentions scores on cohabitation attitudes scores. The analyses revealed a strong positive correlation between cohabitation attitudes and cohabitation intentions in both phase I (r = .88, p < .001) and phase II (r = .83, p < .001). In phase I regression analyses, cohabitation attitudes accounted for 77.5% of the variance in cohabitation intentions (F(1, 223) = 768.58, p < .001, S.E. = 4.33). Also, in phase II regression analyses, cohabitation attitudes accounted for 68.5% of the variance in cohabitation intentions (F(1, 234) = 509.55, p < .001, S.E. = 6.30).

Discussion

As we noted earlier, there is an increase in the number of young people choosing to cohabit all over the world and even in collectivist cultures like Ghana where there are societal restrictions. Regardless of these societal restrictions, young people still find benefits in cohabitation relationships. Researchers need to explain why this is happening and what factors motivate or hinder young people in the decision-making process towards cohabitation. This requires standardized quantitative instruments to measure cohabitation attitudes and intentions. The goal of this study was therefore to develop a new cohabitation intentions scale and to validate an existing cohabitation attitudes scale in the Ghanaian cultural setting.

We developed the new cohabitation intentions scale based on standard instrument design procedures which include reviewing the relevant literature, defining the construct, generating items, expert review of items, piloting items, and validating items through psychometric analyses (Holmbeck & Devine, Citation2009; Morse et al., Citation1996). We validated the new cohabitation intentions scale along with the existing cohabitation attitudes scale with two sets of empirical data (phase I and phase II data). Using the Rasch measurement model (Rasch, Citation1960; Wright, Citation1988), we examined the psychometric properties of the two instruments, and then analyzed for the functionality and appropriateness of the response options. We also conducted item analyses, DIF analyses, and construct validation analyses.

The psychometric analyses revealed that both the cohabitation attitudes and intentions scales are highly reliable instruments for the Ghanaian participants. In addition, the cohabitation attitudes scale had a high item separation index which could have resulted from the higher distance of item 5 (COH_ATT5) from the rest of its items. Item separation is a measure of the spread of items in an ordered continuum of item difficulties. Generally, a high item separation index means that there is a greater spread of items in a linear form, and it is an indication that the measurement instrument will likely produce interval level measures. An inspection of the Wright maps in shows that the cohabitation intentions scale had a good hierarchy of items to serve as a linear instrument for interval level measurement. While the cohabitation attitudes scale had a higher item separation index which contributes positively to instrument sensitivity, the cohabitation intentions scale had a more evenly spread hierarchy of items which is an added advantage for linear instruments. Finally, there was a lower rate of root mean square error (RMSE) for items in both instruments which suggests that the quality of items did not significantly deviate from the Rasch measurement model.

As mentioned earlier, we analyzed two different Likert-rating scales in phase I and phase II datasets. Phase I used a 6-point Likert-rating scale while phase II adopted a 7-point Likert-rating scale by including a midpoint response category of neither disagree nor agree. The midpoint response category was considered a useful link between the negative response categories (i.e. the disagrees) and positive response categories (i.e. the agrees). Although both rating scales met the standards of the Rasch rating scale model (Bond & Fox, Citation2015; Linacre, Citation1999; Wright & Masters, Citation1982), we recommend that researchers use the 7-point rating scale in phase II in order to achieve greater variability in measurement scores.

Moreover, the item analyses revealed that all but one item of the cohabitation attitudes scale (COH_ATT5) and the cohabitation intentions scale (COH_INT4) met the standard of the Rasch unidimensional model (Andrich, Citation1988; Linacre, Citation2012, Citation2020). Item 5 (COH_ATT5) was extremely difficult compared to the other items in the cohabitation attitudes scale. This extreme item difficulty may have caused the misfit of item 5 in the cohabitation attitudes scale. The misfit is unlikely to undermine the validity of the cohabitation attitudes scale. While item 4 of the cohabitation intentions scale was not extremely difficult compared to other items in the scale, the misfit of this item may have occurred as a result of the observed significant DIF contrast between the male and female participants on this item (Linacre, Citation2020; Zwick et al., Citation1999).

As previously mentioned in the results, only item 4 of the cohabitation intentions scale (COH_INT4) displayed significant DIF although the DIF contrast is culturally explicable. According to Billari et al. (Citation2005), the impact of attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived control is gender specific, with subjective norms being highly impactful in decision-making for women than for men. In Ghana, subjective norms around leaving your father’s home to your husband’s home are reliant on the occurrence of a wedding ceremony to announce this transition. Cohabiting couples deviate from this norm and there is some shame associated with being deviants. Kgadima (Citation2017) noted that oftentimes the women bear the brunt of this shame. This is especially heightened in religious cultures such as in Ghana, where female sexual purity is highly valued and monitored, and cohabiters are seen as promiscuous. With regards to perceived control in cohabitation/marriage decisions, men’s economic resources play a significant role in determining relationship progression (Sassler & Miller, Citation2011). This would mean that even for female respondents who desired cohabitation, their male partner’s finances could limit their options. The weight of these factors would certainly differ from one female participant to the other, thus influencing their responses to this item (COH_INT4).

For COH_ATT5 which measured attitudes toward cohabitation without marital expectations, the significant DIF is understandable considering the fact that within the Ghanaian cultural context, attitudes toward cohabitation are generally negative. In instances where there is some acceptance of cohabitation, it is under the agreement of a future marriage (Macaulay, Citation2015). Therefore, cohabitation without marital expectations would be inconceivable for a lot of the participants, including those that had positive attitudes toward cohabitation. In the light of this cultural dynamic in the Ghanaian setting, the misfit and significant DIF of COH_ATT5 and COH_INT4 may not have any significant impact on the validity of the cohabitation attitudes or intentions scale.

Finally, as theoretically and conceptually expected, we found a strong positive relationship between cohabitation attitudes and intentions. The regression analyses also confirmed that cohabitation attitudes have significant influence on cohabitation intentions. This evidence supports the construct validity of the two instruments. Given that the literature provides evidence for a strong positive relationship between attitudes and intentions (e.g. Ajzen, Citation1991; Kasearu, Citation2010), it should also be expected that measurement scores from two instruments that measure these constructs should be related. Therefore, the strong correlation between cohabitation attitudes scale scores and cohabitation intentions scale scores is an indication that the two instruments are measuring the construct they were designed to measure.

Conclusion

The goal of this study was to develop and validate a cohabitation intention scale in the Ghanaian cultural context. A student population was considered relevant to this study because of the prevalence of cohabitation on campuses and due to the fact that university students at this stage of their lives experiment with various social roles and take critical decisions for their life including mate selection. The use of such a population could however be limiting in the sense that Ghanaian university students differ from the average Ghanaian in several ways including their cognition, experiences, and privileges. The uniqueness of the university student population may make the current findings somewhat different from what would otherwise be found in the general population. Thus, generalization of the findings must be done with caveats relating to the population investigated.

This limitation acknowledged, our findings show that the new CIS and the adapted CAS are reliable and valid measures of cohabitation intentions and attitudes in Ghana and in perhaps other similar cultural contexts. While both the 6-point and 7-point rating scale yielded comparable results, it is our recommendation that in using the instruments, the 7-point rating scale should be favored over the 6-point rating scale to achieve greater variability in measurement scores. Also, as revealed in the results of the Rasch analyses, CIS and CAS items differ in difficulties, therefore it will be most appropriate for researchers to consider using Rasch person measures for their analyses, instead of the raw scores obtained through classical test approach. Rasch person measures do not only account for the variations in item difficulties but also consider the differential thresholds of rating scale categories when assessing individuals’ levels on a given latent trait (Bond & Fox, Citation2015; Linacre, Citation1999, Citation2020).

Disclosure statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Data availability statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Angela A. Gyasi-Gyamerah

Angela A. Gyasi-Gyamerah is a social psychologist and senior lecturer at the Department of Psychology, University of Ghana. Her research interests include sexual and reproductive health issues with a current focus on cohabitation and abortion decision-making. She has had several years of field experience working with street youth and commercial sex workers under the auspices of Streetwise Project-Ghana and West Africa Project to Combat AIDS and STI (WAPCAS) respectively. In 2017, she set up a social advocacy organization known as Dialogue Genitalia Ghana which focuses on creating safe spaces for the opposite sexes to discuss issues relating to sexuality and reproductive health.

Christabel Quansah

Christabel Quansah holds a bachelor’s and master’s degree in social psychology from the University of Ghana. Her research interests include gender and culture and its intersection with sexuality and interpersonal relationships. She is currently an instructor of Intercultural Communication and Leadership at the Council on International Educational Exchange, Ghana. Here she guides the students to explore the contemporary host culture through the lens of intercultural studies in order to easily assimilate into the host culture for a more wholesome, enriching experience.

Christopher M. Amissah

Christopher M. Amissah is the Rasch Measurement SIG Graduate Student Representative of the American Educational Research Association (AERA), and a doctoral candidate in Psychometrics at Morgan State University. Chris’ research interests are in Rasch measurement models and culturally responsive measurement. His current research focuses on comparative evaluation of the stability and precision of Rasch models and Exploratory Factor Analysis using selected psychological and educational measures. Chris has several peer-reviewed presentations and publications in scholarly journals.

Kwasi Gyasi-Gyamerah

Kwasi Gyasi-Gyamerah has two decades of experience working with international students. He is currently the Regional Director of Operations for Africa and the Middle East at CIEE. Prior to this position, he had served as Center Director for CIEE, Legon Center based at University of Ghana since 2006. He holds a PhD from the College of Education and MPhil in Clinical Psychology both from the University of Ghana. He is a member of the International Programmes Advisory Board of the University of Ghana. He is also a member of the Ghana Psychological Association and the Ghana Psychology Council. His research interests are in how international students adjust psychologically and socio-culturally to academics and social life in Ghana’s tertiary institutions. He provides probono counseling and mentoring sessions for underprivileged and marginalized kids at an educational intervention organization in the city of Accra.

References

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behaviour. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

- Andrich, D. (1988). Rasch models for measurement. Sage.

- Attah, M. (2012). Extending family law to non-marital cohabitation in Nigeria. International Journal of Law, Policy, and the Family, 26(2), 162–186. https://doi.org/10.1093/lawfam/ebs001

- Baataar, C. K. M., & Amadu, M. F. (2014). Attitude towards marriage and family formation among Ghanaian tertiary students: A study of University for Development Studies. Journal of Asian Development Studies, 3(2), 122–134.

- Billari, F., Philipov, D., & Testa, M. R. (2005). The influence of attitudes, subjective norms and perceived behavioural control on union formation intentions [Paper presentation]. International Union for the Scientific Study of Population (IUSSP) Conference, Tours, France.

- Bond, T. G., & Fox, C. M. (2015). Applying the Rasch model: Fundamental measurement in the human sciences. (3rd ed.). Routledge.

- Calvès, A. E., Kobiané, J. F., & Martel, E. (2007). Changing transition to adulthood in urban Burkina Faso. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 38(2), 265–283. https://doi.org/10.3138/jcfs.38.2.265

- Connelly, L. M. (2016). Cross-sectional survey research. MEDSURG Nursing, 25(5), 369.

- Delevi, R., & Bugay, A. (2010). Understanding change in romantic relationship expectations of international female students from Turkey. Contemporary Family Therapy, 32(3), 257–272. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10591-010-9124-4

- Ghana Statistical Service (GSS), Ghana Health Service (GHS), and ICF International. (2015). Ghana demographic and health survey 2014. GSS, GHS, and Maryland, USA: ICF.

- Holmbeck, G. N., & Devine, K. A. (2009). Editorial: An author’s checklist for measure development and validation manuscripts. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 34(7), 691–696. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsp046

- Kamgno, H. K., & Mengue, C. E. M. (2014). Rise of unofficial marriages in Cameroon: Economic or socio-demographic response? American International Journal of Social Sciences, 3(3), 55–66.

- Kasearu, K. (2010). Intending to marry… Students’ behavioural intention towards family forming. Trames. Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences, 14(1), 3–20. https://doi.org/10.3176/tr.2010.1.01

- Kgadima, N. P. (2017). [Cohabitation in the context of changing family practices: Lessons for social work intervention ]. [Doctoral dissertation]. University of South Africa.

- Khoo, S. T., & Ainley, J. (2005). Attitudes, intentions and participation (No. 7-1-2005). The Australian Council for Educational Research Ltd. https://research.acer.edu.au/lsay_research/45

- Kogan, I., & Weißmann, M. (2020). Religion and sexuality: between-and within-individual differences in attitudes to pre-marital cohabitation among adolescents in four European countries. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 46(17), 3630–3654. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2019.1620416

- Kyei, T. E. (1945). Marriage and divorce among the Asante. Asante Social Survey. https://www.african.cam.ac.uk/system/files/documents/marriage.pdf

- Linacre, J. M. (1999). Investigating rating scale category utility. Journal of Outcome Measurement, 3(2), 103–122.

- Linacre, J. M. (2012). What do infit and outfit, mean-square and standardized mean? Rasch Measurement Transactions, 16(2), 878.

- Linacre, J. M. (2020). Winsteps: A user’s guide to winsteps ministep Rasch-model computer programs. Program Manual, 4.7.0. https://www.winsteps.com

- Linacre, J. M., & Wright, B. D. (2002). Understanding Rasch measurement: Construction of measures from many-facet data. Journal of Applied Measurement, 3(4), 486–512.

- Macaulay, R. (2015). Cohabitation among Young Adults of the Global Evangelical Church in Ghana [Doctoral dissertation]. University Of Ghana.

- Manning, W. D., Longmore, M. A., & Giordano, P. C. (2007). The changing institution of marriage: Adolescents’ expectations to cohabit and to marry. Journal of Marriage and Family, 69(3), 559–575. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2007.00392.x

- Manning, W. D., Smock, P. J., Dorius, C., & Cooksey, E. (2014). Cohabitation expectations among young adults in the United States: Do they match behaviour? Population Research and Policy Review, 33(2), 287–305. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-013-9316-3

- Meijer, S. S., Sileshi, G. W., Catacutan, D., & Nieuwenhuis, M. (2016). Farmers and forest conservation in Malawi: the disconnect between attitudes, intentions and behaviour. Forests, Trees and Livelihoods, 25(1), 59–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/14728028.2015.1087887

- Morse, J. M., Mitcham, C., Hupcey, J. E., & Tasón, M. C. (1996). Criteria for concept evaluation. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 24(2), 385–390. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.1996.18022.x

- Murrow, C., & Shi, L. (2010). The influenceof cohabitation purposes on relationship quality: An examination in dimensions. The American Journal of Family Therapy, 38(5), 397–412. https://doi.org/10.1080/01926187.2010.513916

- Obeng-Hinneh, R. (2018). Understanding consensual unions as a form of family formation in Urban Accra [Doctoral dissertation]. University of Ghana.

- Odimegwu, C., Ndagurwa, P., Singini, M. G., & Baruwa, O. J. (2018). Cohabitation in sub-Saharan Africa: A regional analysis. Southern African Journal of Demography, 18(1), 111–170.

- Ogunsola, M. O. (2011). The effect of premarital cohabitation on quality of relationship and marital stability of married people in Southwest Nigeria. African Nebula, 1(3), 16–24.

- Okyere-Manu, B. (2015). Cohabitation in AKAN Culture of Ghana: An ethical Challenge to gatekeepers of indigenous knowledge system in the Akan culture. Alternation Special Edition, 14, 45–60.

- Palamuleni, M. E. (2010). Recent marriage patterns in South Africa 1996-2007. Bangladesh e-Journal of Sociology, 7(1), 47–70.

- Popoola, O., & Ayandele, O. (2019). Cohabitation: harbinger or slayer of marriage in sub-Saharan Africa? Gender and Behaviour, 17(2), 13029–13039.

- Rasch, G. (1960). Probabilistic models for some intelligence and attainment tests. Reprint, with Foreword and Afterword by B. D. Wright, University of Chicago Press. 1980. Danmarks Paedogogiske Institut.

- Rogers, A. A., Willoughby, B. J., & Nelson, L. J. (2016). Young adults’ perceived purposes of emerging adulthood: Implications for cohabitation. The Journal of Psychology, 150(4), 485–501. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2015.1099513

- Rontos, K., Roumeliotou, M., Salvati, L., & Syrmali, M. E. (2017). Marriage or cohabitation? A survey of students’ attitudes in Greece. Demográfia English Edition, 60(5), 5–31. https://doi.org/10.21543/DEE.2017.1

- Sassler, S., & Miller, A. J. (2011). Waiting to be asked: Gender, power, and relationship progression among cohabiting couples. Journal of Family Issues, 32(4), 482–506. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X10391045

- Shields-Dutton, K. (2004). Attitudes toward cohabitation: A cross sectional study (Unpublished [master’s thesis]). University of Central Florida.

- Stanley, S. M., Rhoades, G. K., Amato, P. R., Markman, H. J., & Johnson, C. A. (2010). The timing of cohabitation and engagement: Impact on first and second marriages. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 72(4), 906–918. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00738.x

- Willoughby, B. J., & Carroll, J. S. (2012). Correlates of attitudes toward cohabitation: Looking at the associations with demographics, relational attitudes, and dating behaviour. Journal of Family Issues, 33(11), 1450–1476. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X11429666

- Wright, B. D. (1988). George Rasch and measurement. Rasch Measurement Transactions, 2(3), 25–32.

- Wright, B. D., & Masters, G. N. (1982). Rating scale analysis: Rasch measurement. MESA Press.

- Xu, Y., & Ocker, B. L. (2013). Discrepancies in cross‐cultural and cross‐generational attitudes toward committed relationships in china and the United States. Family Court Review, 51(4), 591–604. https://doi.org/10.1111/fcre.12055

- Yu, J., & Xie, Y. (2015). Cohabitation in China: Trends and determinants. Population and Development Review, 41(4), 607–628. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2015.00087.x

- Žilinčíková, Z., & Hiekel, N. (2018). Transition from cohabitation to marriage. The role of marital attitudes in seven western and Eastern European countries. Comparative Population Studies, 43, 3–29. https://doi.org/10.12765/CPoS-2018-04

- Zwick, R., Thayer, D. T., & Lewis, C. (1999). An empirical bayes approach to mantel-haenszel DIF analysis. Journal of Educational Measurement, 36(1), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-3984.1999.tb00543.x