Abstract

Objective

To explore the views of social prescribing service providers on the barriers and enablers to recruitment of service users in social prescribing research.

Design

A qualitative study design, using semi-structured interviews with social prescribing service providers in the voluntary, community, faith, and social enterprise sector. Data were analysed using Thematic Framework Analysis.

Results

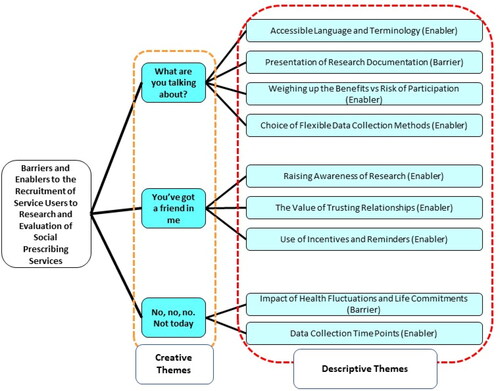

Ten interviews were conducted with service providers from five different social prescribing services. Three analytical themes were created. (1) What are you talking about?, related to service provider experiences of attempting to engage service users in social prescribing research, specifically confusion about the term social prescribing. (2) You’ve got a friend in me, focused on the positive impact of quality relationships between service providers and service users on recruitment. (3) No, no, no. Not today, reflected the experiences of service providers who reported that service users will often experience fluctuations in their mental and physical health, limiting their capacity to engage with structured research activity.

Conclusions

Key implications arising from this study is a need for more accessible and person-centred strategies for strengthening recruitment to, and participation in, social prescribing research. Increasing accessibility of research language (and information about participation), providing flexibility in recruitment methods, and conduct of research can also improve recruitment and retention. Service providers are vital for supporting engagement of service users in social prescribing research.

Reviewing Editor:

Introduction

Social prescribing offers a package of wraparound care to individuals to address their physical, mental, and social health and wellbeing, and can be defined as a non-pharmacological, community-based intervention that aims to address the holistic needs of the individual (NHS lnu, 2022). Social prescribing services aim to provide a person-centred approach where a social prescriber engages a client in shared decision-making, to co-produce (i.e. between a link worker and client) a package of care (social prescription) based on their personal needs and preferences. Social prescribing has its roots within the Voluntary, Community, Faith, and Social Enterprise Sector (VCFSE). In the UK National Health Service (NHS), a common social prescribing pathway is the use of link workers within the NHS, specifically within primary care, to refer people to the VCFSE sector. People would then receive a social prescription (support group, community welfare support, or volunteering scheme for example) in their local community (NHS England, Citation2023). There is mixed evidence to support the impact of social prescribing services on health-related outcomes, with few studies reporting on impact on service use (e.g. reduction in primary care attendance), hindered by high attrition rates, with an average of 38%, and in some cases up to 90% (Cooper, Avery, et al., Citation2022; Wakefield et al., Citation2022).

In the context of research broadly, the recruitment of a representative sample is an important methodological issue. Sub-optimal recruitment and retention is recognised to impact negatively on the veracity of conclusions that can be drawn and is relevant regardless of study design, as evidenced in cross-sectional surveys (Wu et al., Citation2022), randomised control trials (Treweek et al., Citation2018), qualitative research (Negrin et al., Citation2022), including social media-based research (Archer-Kuhn et al., Citation2022). For social prescribing services in particular, the target population can also present additional complexity for recruitment and retention; potential participants are more likely to be experiencing complex difficulties, encompassing physical, mental, and social health issues (Cooper et al., Citation2023). Combined with the heterogeneity of people’s experiences and their personal needs and goals, typical methods of recruitment may not be as appropriate, especially when used in isolation.

There is also the possibility that any positive health outcomes reported as a result of social prescribing might be over-stated as only those who feel they have experienced or have the greatest potential to benefit are more likely to participate in research (Webber-Ritchey et al., Citation2021). While this bias is not unique to social prescribing research, what is different is the lack of evidence for effectiveness, with issues around recruitment and retention a contributing factor to distorted findings. These issues need to be addressed to strengthen the evidence base for social prescribing services. This would facilitate sustainability and optimisation of social prescribing services via continued funding, where evidence informs decision-making on funding provision when community-based services are often first to be cut when resources are limited.

Social prescribing research is often undertaken by researchers external to the social prescribing service, typically from a research institution, with support from social prescribing professionals. Previous research has reported that recruitment can be influenced by issues surrounding confidentiality (Bonisteel et al., Citation2021), working with gatekeepers (Namageyo-Funa et al., Citation2014), and ambiguity about the research (Natale et al., Citation2021). One study concluded that gatekeepers involved with the recruitment of participants were motivated based on their interest in the research and the potential positive impact on daily practice (Sheridan et al., Citation2020). What is not yet established in social prescribing research is the role that link workers play in supporting research recruitment and engagement, or their views on methods of recruiting and retaining participations.

In the wider field of qualitative health research, systemic barriers can impact negatively on the recruitment of participants (such as trust in research and time capacity) (Perez et al., Citation2022). Other barriers include the lack of community-driven frameworks for research and opportunities for adjusting recruitment strategies based on participant feedback (Webber-Ritchey et al., Citation2021). The impact of these barriers within social prescribing research has yet to be established, and recommendations to change recruitment practice have yet to be developed. Whilst multimodal strategies that utilise research team composition (research teams with diverse backgrounds and experiences), flyers, social media, and purposive sampling are reported to increase recruitment of diverse samples in qualitative health research (Webber-Ritchey et al., Citation2021); again, it is unknown whether they would also be applicable for social prescribing research. Studies that were designed to establish the effectiveness of social prescribing services have utilised a multitude of methodological approaches (Costa et al., Citation2021; Kiely et al., Citation2022; Tierney et al., Citation2020). However they still experienced issues with recruitment and retention of participants, highlighting the need for research to directly examine recruitment and retention from people working in social prescribing services in the VCFSE sector who have an in-depth experiential understanding of the context and research setting.

This research aims to address this gap in knowledge by exploring the perceptions of social prescribing service providers who have facilitated recruitment of service users to research to inform recommendations for research practice to support the recruitment and retention of participants in social prescribing research. In the context of this qualitative study, social prescribing service providers (SPSP) included link workers (or iterations of this role such as community link worker, community navigator, or social prescriber), team leaders, and managers involved in the delivery of social prescriptions in the VCFSE sector.

Methods

Study design

This research employed a qualitative study design, using semi-structured interviews with SPSPs.

Research team

Two authors were PhD candidates (MC, KA) at the time the research was conducted, and held a postgraduate degree in Health Psychology. Three authors (LA, DF, JS) are chartered psychologists and hold a PhD qualification. MC and KA were trained in qualitative research methods and LA, DF and JS have extensive experience of leading/conducting qualitative research. MC conducted all interviews and had no prior relationships with participants prior to commencement of the study.

Participants

Eligible participants were SPSPs, aged ≥18 years, and employed by UK-based social prescribing services in the voluntary, charity, faith, or social enterprise (VCFSE) sector. Participants were recruited from the VCFSE sector as social prescribing services are primarily delivered by the VCFSE following a self-referral or referral from primary care link workers or other VCFSE organisations. Participants were a convenience sample recruited via gatekeepers within the VCFSE using contacts and networks known to the study authors (i.e. contacts made during the conduct of previous research).

Data collection

The geographical location of participants (i.e. where they were employed) was recorded. No additional participant data was collected because our research was not looking at comparisons between participant demographics to address the research aims (Van Epps et al., Citation2022).

Interviews with participants were conducted using a topic guide (Appendix 1). The topic guide consisted of three open questions (experiences of challenges, beliefs about recruitment strategies, and identifying solutions/recommendations for improvement), followed by a series of prompts depending on the question. The development of the topic guide was iterative and informed by previous research and the authors’ experiences of recruitment to research studies (Cooper, Avery, et al., Citation2022; Cooper, Flynn, et al., Citation2022). It was piloted with the first participant to assess the relevance of the questions for addressing the research aims. The topic guide included questions about experiences of recruitment and retention to research and service evaluations, methods of data collection, willingness, and capabilities of service users to engage with research, stigma, and information delivery (e.g. during recruitment). SPSPs were asked to reflect on any personal challenges they had experienced with recruitment and retention to research. Finally, participants were asked for their views on enablers to recruitment and retention, and what would be feasible to implement within their service.

Following receipt of consent, all interviews were conducted using Microsoft Teams (video conferencing software) and audio recorded using a Dictaphone. Recordings of interviews were transcribed verbatim. Interview transcripts were read through by one researcher (MC) while listening to the audio recording to check for accuracy. Personally identifiable information was replaced with pseudonyms or redacted from transcripts.

Data analysis

Interview data was analysed using thematic framework analysis (TFA) to create an analytical hierarchy of themes and constructs of meaning, which allows for a systematic approach to data analysis, with transparent data management (Ritchie et al., Citation2013). TFA follows an established methodology consisting of six steps (a description of each step is provided below). This was conducted independently by two researchers (MC, JS) with input on the veracity of the process and developed themes from the other study authors (DF, LA, KA) (Barbour, Citation2001; Hennink & Kaiser, Citation2022; Janesick & Peer, Citation2015).

Step 1: Familiarisation with the data. Familiarisation involved three stages: immersion (reading transcripts), critical engagement (reviewing transcripts in relation to the research aim) and documenting initial thoughts (ideas and feelings related to the data).

Step 2: Generation of initial codes. One researcher (MC) read all interview transcripts systematically, noting points of potential relevance to the research aim. This was highlighted and labelled with a code. One researcher (JS) independently read 50% of the interview transcripts. Coding between researchers was compared and discussed before moving to the next step.

Step 3: Generating initial themes. This consisted of MC creatively thinking and engaging with the raw data to organise initial codes into potential descriptive themes, followed by discussion with another researcher (JS) for clarification and consistency with previous steps.

Step 4: Development and reviewing of themes. Codes were developed into descriptive themes based on similarity of meaning by one researcher (MC) and discussed with another researcher (KA) to establish confirmation of interpretation. The purpose of this stage was to check the initial descriptive theme clusters and constructs of meaning and to check for any additional patterns or descriptive themes.

Step 5: Refining, defining, and naming themes. All descriptive themes created were assigned a name and a definition from which analytical themes were developed. This was completed through discussion between two researchers (MC, KA). This allowed for a higher order interpretation of the data and organisation of descriptive themes into more dominant analytical themes across the entirety of the data set. An analytical theme can be identified as capturing ‘underlying patterns and commonality between the categories to answer the research question’ (de Farias et al., Citation2021). The analytical themes defined the scope and core concept of the meaning within groups of descriptive themes. In addition, a final creative theme label was added to capture the attention of the reader (Francis et al., Citation2010). These creative themes were used to give an interpretive starting point and a sense of how each researcher interpreted the data (Francis et al., Citation2010).

Step 6: Presentation of final themes. Themes were refined to represent a structure and hierarchal order of the data flow and any underlying interconnectedness of themes. The final themes were presented to all study authors to check for understanding and representation of collected data.

All analysis was carried out by hand. In line with published guidance, interviews were conducted to the point of data saturation (Hennink & Kaiser, Citation2022). This was informed by the literature that outlines three principles that are needed to confirm data saturation. Each of these three principals were checked by one researcher (MC) following the conduct of every second interview (Hennink & Kaiser, Citation2022).

Principle one: Initial sample size was appropriately sized for the phenomenon of investigation allowing for different experiences to be captured (diversity of sample).

Principle two: A stopping criterion was applied when no new information emerged from three consecutive interviews.

Principle three: Independent coding between two researchers (MC, JS) and discussions with all team members (i.e. co-authors) to establish the robustness of the themes.

Methods to maximise trustworthiness

Initial descriptive and analytical themes were reviewed by all authors to improve trustworthiness (Barbour, Citation2001). Two researchers (MC, JS) worked independently to code, and organise data into descriptive themes. Two researchers subsequently developed the descriptive themes into overarching analytical themes (MC, KA) (Janesick & Peer, Citation2015; Spall, Citation1998). This use of triangulation allowed for the development of descriptive themes and the generation of analytical themes without losing the grounding in the raw data (Hallsworth et al., Citation2020; Yamada et al., Citation2018). It also ensured the data were represented and there was transparency across each hierarchical level of analysis. All themes were presented with supporting quotes to add context and grounding in the data (Coughlan et al., Citation2007; Ryan et al., Citation2007).

Ethics statement

This research received ethical approval from the School of Health and Life Science Research Ethics Committee at Teesside University (Reference: 2021Jan1710Cooper)

Results

The three principles of data saturation were met following the conduct of ten interviews with SPSPs from five services based in the VCFSE sector (4 in England, 1 in Wales). Average interview duration was 27 min (range 21–37 min). Several participants had previously been or engaged in supporting the recruitment of service users into research studies, although a proportion (30%) of participants were unknown to the research team. Three analytical themes were created from analyses of interview data. Each analytical theme (with creative theme labels) associated descriptive themes, and supporting quotes from participants are presented in supplementary materials 1, with a diagrammatic representation presented in .

Figure 1. SPSP perspectives of the barriers and enablers to recruitment in social prescribing research and evaluation.

Theme 1: what are you talking about?

This analytical theme related to participants’ experiences with service users who were confused about social prescribing research and practice. There were four associated descriptive themes that captured participant experiences of barriers to recruitment and retention of service users in research.

Accessible language and terminology

The language used in the context of social prescribing services and research represented a potential barrier to engagement in research. Participants reflected on how some service users, ‘haven’t been told, or don’t care, that it’s called social prescribing’ (P02), which meant that some, ‘may not even know that they’ve had a social prescribing intervention’ (P02). While this was a common finding, there were no alternative terms suggested for how service users describe social prescribing services. Informed by previous experiences of the research team, terms could include therapy services, social services, or mental health support. Consequently, participants recommended that language used to refer to social prescribing research should be congruent with that used by the service and service users (for example, tailoring language to that of the participant)

Other participants suggested that use of clinical labels such as anxiety and depression would impact negatively on participation, as in their experience, service users did not think in those terms, with descriptions of symptoms considered as more acceptable. Participants felt the word interview may have negative connotations for some:

[the] level of terminology and language used, […] ‘research’ or ‘interview’ may seem a little bit like additional stress to things that they might find timely, where an informal chat might be more appealing to someone (P06).

When the only interview they might have is with the Department of Work and Pensions or somebody wanting to take away their PIP [Personal Independent Payment] or something like that (P03).

Make it less official, less clinical, but with the same meaning, you know, which people would be more receptive because if people don’t understand words or meaning then you’re not going to engage them (P08).

Presentation of research documentation

Making the information about research studies (such as participant information sheets) accessible and acceptable to service users, whilst addressing ethical requirements, was a key issue highlighted by participants that impacted on service user engagement with research. Participants recalled comments from service users about previous research, ‘the way that the patient information sheets were written, it was more for the academics involved and for the research ethics committee and more the powers that be, than it was to have a service user friendly document’ (P03). However, it was acknowledged there was a need to ensure ethical considerations and informed consent were fully addressed—‘the right balance between the demands of the ethics committee and the needs of clients, I think is going to be tricky’ (P03).

In addition, several participants described how using written communication might lead to barriers to participation in research, as many service users have low levels of literacy. Participant 07 reflected on this ‘a big lesson for us is written information, again I think the average reading age for the communities that we work in is nine. So, how do we produce written information that’s accessible to people’ and found that ‘word of mouth from trusted sources is better than from anonymous sources’. Other participant accounts referred to service users with learning difficulties who ‘wouldn’t be able to understand the form and what was required of them’ (P08).

Furthermore, the completion of ethical documents (such as the consent form) was seen as a further barrier to service user participation in service evaluations. Participants recalled instances where they did not ‘know how confident people feel about either using a picture of their signature or just typing their name’ (P02) and whether service users had the necessary digital literacy skills. Other participants provided accounts of their experiences of gaining consent, where service users were overwhelmed with information. One participant described how they dealt with this situation:

relay the information to them, and just get a straight yes or no answer from them which just takes the pressure off them having to seek the advice out…interpret it, and then come up… you know, it’s more that we describe that to them, and they’ll just say yes or no to their consent (P06).

Weighing up the benefits versus risks of participation

A leaflet or a conversation outlining the benefits of the research for service users and the service was believed to improve engagement rates in research, for example ‘describe with them face to face as such, what it takes to encourage them and make them feel reassured by it, would probably get higher levels of engagement than asking them to read through and then respond’ (P06). This was echoed by other participants who recommended a leaflet style resource that service users could take away with them to digest in their own time, followed by a request to take part in the research.

The personal benefits to service users were commented on by one participant:

People were much more willing to give information on that basis if they felt that it was something that was helpful, that would help them’ (P03).

it’s about making it really, really easy, going to where people are, making it really easy and aligning what was important with what was important to them and acknowledging that that had to be very timely as well (P07).

Choice of flexible data collection methods

Participants used a range of data collection methods for their own service evaluations. These included telephone calls, video calls, letters, text messages, emails, posters, advertisements, and/or social media. Participants spoke of their experiences of using these methods in combination with varying levels of success. For every participant who said one method was successful for their service users, another would tell of how the same method was a barrier that led to disengagement. Overall, offering service users a choice of engagement methods in research that are sensitive to their preferences would appear to be the optimal approach—‘they might be perfectly happy doing everything online’ or ‘they might be perfectly happy speaking to somebody on the end of the phone’ (P09). An optimal approach would involve tailoring data collection methods to the target population and actively involving members of the public (public partnerships) to support the design. However, this approach has resource implications and researchers should consider the allocation of appropriate resources at the data collection stage of the research process to offer a flexible method of data collection. Specific methods will likely involve additional time and expertise to develop online data collection platforms or resources, with robust data security and storage mechanisms.

Theme 2: you’ve got a friend in me

The second analytical theme represents participants’ accounts of building positive relationships with services users, which was a prerequisite for enhancing their recruitment to, and engagement in, social prescribing research. This theme related to participants’ established relationships with service users which made them ideally placed to support research recruitment. Participants in their role offered initial support to service users to bridge the gap between them and the ‘unknown’ researchers.

Raising awareness of research

Participants reflected on the work they had done to raise awareness of research to facilitate service user recruitment in research studies: ‘we spent three months just developing relationships in our host environments, so that they were then doing the kind of brief intervention, opportunistic conversations about recruitment’ (P07). Participants placed an emphasis on how prior development of relationships with service users had helped them approach the topic of involvement in research and the benefits research could bring to the service. It was these trusting relationships that were considered vital to introducing service users to the idea of research and the researchers conducting the research within their services. If introductions were made via a SPSP, then the service user was considered more likely to participate in research. Recruiting service users at locations where they already felt comfortable and knew the staff helped with recruitment, such as within communities or primary care spaces. Recruitment strategies such as use of peer researchers, or peer-to-peer recruitment (snowball sampling), where peers could inform others about research, could be considered helpful. However, participants, ‘recognise that there is bias with the link worker asking [service users] to report back’ (P06) and these ethical issues should be considered when using pre-existing relationships (e.g. coercion) in recruitment to research.

The value of trusting relationships

Participants referred to the development of a therapeutic and trusting relationship with service users. It was highlighted that once they were both in a positive place, a conversation could be had where they could say ‘I think it would be great if you could take part in this because it will help people understand about social prescribing’ (P01). Participants acknowledged the impact of an existing therapeutic relationship and the influences this could have, ‘we have an established relationship that we continue to build on and you guys don’t. Again, you will know from your own work about the importance of that engagement, that contracting, that trust that you need to build up’ (P07). Participants described how they could introduce researchers to service users, where they could, ‘do shadowing and stuff, in person it’s like, this is my colleague, who is new, I’ve never had anyone say, no I don’t want them listening or I don’t want them here, everyone is like, yes, they’ve got to learn’ (P04). By offering a more informal introduction the service user would become familiar with the researcher and the reason for the research study, which in turn could be an enabler to participation in research.

Ethical considerations were raised again in relation to the boundaries of a therapeutic influence on participation, ‘I was just saying that you need link workers onsite to persuade their clients to take part and that would probably … that element of persuasion would probably go down like a lead balloon with ethics’ (P03). Service users may feel under pressure, and therefore avoid providing negative feedback about their SPSP, and there is also high risk of SPSPs ‘cherry picking’ the service users they believe would provide positive feedback on the service (selection by gatekeeper leading to selection bias in the sampling strategy). These considerations parallel those for recruitment across health and social care research, and careful consideration needs to give to how to minimise their impact.

Use of incentives and reminders

The use of incentives to support engagement in research and evaluation-based activities was considered to be an enabler, however participants acknowledged this need not be financial. If ‘the research is for your benefit’ (P03) and service users were taking part based on a desire to help others, then this was a further enabler. Other participants spoke about the size of monetary incentives:

any token of support like that means the world, and we had a conversation around this this morning in our meeting, where link workers were thinking around which clients, we could promote this to, and the link workers all identified how £30 would be a huge help to a lot of people that we serve (P06).

How important was it for them to recruit or was it just something that they added to a long list of stuff that they had to do. How many of them actually had conversations with clients, as opposed to you asking them to do it, so at a very basic level, was it important to them, did they have time to do it in a very busy conversation and did they have the capability to do it justice (P07).

Theme 3: no, no, no. not today!

The third analytical theme referred to the perception amongst participants that service users will occasionally have too much going on in their lives to have the capacity to engage in research. This was not seen as a negative or that service users would not engage later, but more of an acknowledgement that first and foremost, service users come to social prescribing services for support with their mental health and other needs. Participants commented that research should be flexible and allow a service user to ‘come in and out’ of the research as appropriate, by providing them with the opportunity to say no initially, but potentially change their mind later down the line.

Impact of health fluctuations and life commitments

Participants knew from experience that fluctuations in service users’ mental health affected their willingness to engage with services, which was also applicable to participation in research. For example, one participant asserted that engagement ‘with self-care activities is low, never mind doing something additional such as research’ (P04). One participant suggested allowing time for service users to engage when they felt comfortable with doing so and providing repeated opportunities for them to (re-)engage in research, rather than at just one time point (for example, after receiving a social prescription). Not only this but, ‘at what point in stability with their [service users] emotional wellbeing they are’ (P04) and researchers should consider ‘everything else with their complex lives that goes hand in hand with that’ (P04). Enabling participation with research over time would allow service users to engage when they felt ready and able. Research should be conscious that ‘people with mental health problems need something when they need it’’ (P01) and that engagement opportunities should reflect this reality.

Regarding complexity of service users’ lives, life commitments were important to consider such as family or employment. Participants talked about their experiences of being flexible and able to work around service users’ lives, ‘I think nightshift is a big one, I’ve always struggled personally, as a professional to try and get somebody to answer the phone almost’’ (P04). This underscored the need to understand service users’ availability when engaging and scheduling data collection. Participant 07 described the type of demands that a service user might be facing:

if you’re rushing to drop the kids off and you’ve got to go and think about, have you got a shift at your zero hours contract and you’re caring for elderly relatives and you’re doing all that with the psychosocial distress of not knowing whether you’re going to be able to get enough food or pay the heating bills, engaging in something that’s important to somebody else is probably not on your radar and not on your agenda. (P07)

Data collection time points

The amount of time a service user had been engaged with a social prescribing service, and the progress made with their mental health and wellbeing, was considered to impact positively on both service user engagement in research and their reflections on their experiences of the support received. All participants stated that service users who benefited from a social prescription would be more likely to report their positive experiences than those who had not:

I think people who’ve gone through an intervention and had a really good one, are perhaps more interested in giving back than those who are perhaps still trying to work out their own mental health and well-being (P02).

Services users with a more protracted experience of engaging with a social prescribing service may experience specific benefits (e.g., development of social skills and confidence) that would make it more likely they would engage in research, as participant 05 attested:

What I realised was that if people had had a positive experience and were confident… it’s a lot about confidence and sharing something which is very personal to yourself. So, if you’re dealing with mental health issues, people have their stories to tell, they are willing to tell it, but only to people that they feel really comfortable and confident with [doing so]. (P05)

Discussion

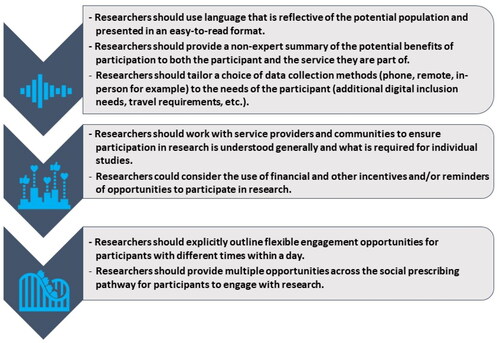

This qualitative study is the first to examine the views of SPSPs in the VCFSE, who often perform a pivotal gatekeeping role in social prescribing research, about the barriers and enablers to recruitment and retention of service users in research. Three analytical themes and nine descriptive themes were derived from SPSPs during one-to-one interviews. Issues in need of consideration for potentially improving recruitment and retention in future social prescribing research were: accessibility of the recruitment methods; raising awareness of research with service users through information, understanding the importance of the research for the service and the service users; and how research needs to consider the health of service users and how this influence recruitment and retention and the need to provide adequate flexibility to support their participation. The findings of this research have informed the development of recommendations () for enhancing recruitment and retention of service users in social prescribing research.

Figure 2. Recommendations for enhancing recruitment and retention of service users in social prescribing research.

Whilst several factors that influence recruitment and retention to social prescribing research are described in the wider qualitative health research literature (use of appropriate language, financial rewards, or power dynamics) (Grant, Citation2011; Halpern, Citation2011; McFadyen & Rankin, Citation2016), findings that were especially relevant to social prescribing research were that certain types of language should be avoided (including the term ‘interview’) (Peters et al., Citation2016), the influences of mental health on recruitment and retention; the therapeutic relationship between social prescriber and service users; and strategies for supporting gatekeeper recruitment within social prescribing research.

The most prominent analytical themes that captured both barriers and enablers, was the approach taken to recruit participants. Specifically, incorrect use of language and poor presentation of participant information documents can lead to a misunderstanding of what participation involves, the aims of the research, and the value of participation, all which impact negatively on recruitment and retention. For example, researchers typically used the term ‘interview’ when referring to a method of qualitative data collection, but use of this term in the context of social prescribing research is problematic, specifically in relation to mental health. The term ‘interview’ can often be associated with (re-)assessment of personal benefits (a form of social security in the UK, such as personal independence payment assessments, which are conducted in the UK by the Department of Working Pensions to establish benefit entitlement). These assessments usually involve a lengthy process of interviews and research has recorded how the experience of a benefit ‘interview’ is considered negative and/or stressful (Grant, Citation2011). The use of inaccessible language more broadly has been reported to increase cognitive overload when reading text, which can affect the participants’ understanding of what is being asked of them in research (Isaacs et al., Citation2022). The study of appropriate language is seen as one of the biggest challenges in recruiting participants to randomised control trials (RCTs) where there is a need to provide information in an understandable way without losing the level of detail required to ensure a participant is fully informed (Newington & Metcalfe, Citation2014). In the context of social prescribing research, terms like consent, transcription, or ethics could mean different things to different groups. Social prescribing research should therefore reflect the community which it represents and as such consult with service users to identify the most appropriate language to use. This should also consider translation or interpreting services to reduce language barriers when communicating and to ensure requirements are adequately understood (Patel et al., Citation2003).

Research documents are created with a need to meet the requirements of academic ethical assessment or funding panels and not with the specific needs and circumstances of individual participants in mind (Isaacs et al., Citation2022). While upholding the ethical rigour of research is important, there is a need to ensure recruitment bias introduced by the research process itself is minimised as much as possible (Haley et al., Citation2017; Kannan et al., Citation2019). This creates a balancing act for researchers to perform with ensuring what is written meets ethical and regularity standards, while maintaining accessibility for participants (Beskow et al., Citation2010; Kraft et al., Citation2017). This research progresses this debate by suggesting that an alternative language should be used when researching social prescribing (e.g. replacing ‘interview’ with the term ‘conversation’ or ‘discussion’) and all communications should be reflective of the participants language and literacy levels, with the opportunity for an open discussion about terms that are unfamiliar (Peters et al., Citation2016). While some of the findings reported, (i.e. language and accessibility) have been identified by applied health and qualitative research more generally (Beskow et al., Citation2010; Haley et al., Citation2017; Kannan et al., Citation2019; Peters et al., Citation2016), they were particularly pertinent in the context of social prescribing research.

The need to increase awareness of research processes, such as how to take part and what will happen, and the potential benefits of the research to the participant (e.g., improving social prescribing service provision and/or personal financial rewards) was highlighted consistently in this research. The use of financial rewards for participation in research has been a common tool to improve participation (Halpern, Citation2011). While some research offers reimbursement for travel expenses, others can offer more substantial rewards for completing more complex research or participation in trials (Resnik, Citation2015). Providing financial rewards or incentives (or compensation) ensures participants are not financially impacted by participation and is typically offered with short-term benefit for their input. However, social prescribing services are frequently accessed by people in receipt of benefits, therefore reimbursement may have implications for tax or benefit (social security) claims and should be carefully considered. If financial incentives are provided, there is debate about the impact this could have on the autonomous choice to participate, with the incentive representing a potential coercion concern or a risk of false participation (McNeill, Citation1997; Ridge et al., Citation2023; Vallotton, Citation2010).

Additionally, previous research has reported on how the use of incentives can lead to a conflict of interest in those who participate (Zutlevics, Citation2016), whereby the motivation to participate is financial versus other considerations, such as supporting the development of knowledge, especially where there may be no immediate impact on themselves (Ridge et al., Citation2023). The current research outlined that SPSPs believed that financial incentives would be useful, but researchers should consider the points raised to decide whether use of an incentive will impact the autonomous choice of participants. Guidelines should be used to provide a standardised and fair reimbursement for participation (National Institute for Health and Care Research [NIFHAC], 2022).

The use of pre-established relationships between SPSPs and service users was suggested to be advantageous for research recruitment. SPSPs felt they could act as gatekeepers to service users where they could introduce the concept of research and the research team. Supporting research was deemed to be part of their professional role for participants in this study, and although a proportion (30%) of participants were known to the research team, which could suggest that views were skewed by previous experience of research, those participants unknown to the research team responded similarly.

Reflecting on the literature, there are potential benefits of this approach for increasing access to populations or improving trust in the researcher (Crowhurst & Kennedy-Macfoy, Citation2013; McFadyen & Rankin, Citation2016). However, capabilities of gatekeepers to engage in recruitment activity may be influenced by the amount of time they are given to recruit or the frequency of research recruitment within the population (Daly et al., Citation2019). Research has also suggested that if the relationship between the researcher and gatekeeper is not established (mutual goals on ethical considerations), this can lead to issues with denied or limited access (McFadyen & Rankin, Citation2016). Furthermore, research has reported on the power dynamic between the provider and receiver of support (McFadyen & Rankin, Citation2016). Power dynamics can create distrust between researcher and participants, especially in certain populations, such as mental health or within community-based research (Rose & Kalathil, Citation2019; Wallerstein et al., Citation2019). As such, there is a need for negotiation regarding the responsibilities of the provider when supporting the service user to engage with social prescribing research (Crowhurst & Kennedy-Macfoy, Citation2013; Edwards, Citation2013). To address this concern, social prescribing research could consider the implementation of a framework for community recruitment, whereby gatekeepers are actively involved in the research and support the recruitment based on their positionality to the target population (Wilson, Citation2020). Additionally there should be considerations made about renumeration for the organisations involved (either VCFSE or NHS), where organisational payments cover the costs of employees for the time they spend recruiting. This process (i.e. the Attributing the cost of health and social care Research and Development Framework) is already in place for the NHS and its partners to identify, recover and attribute the costs of health and social care research (Department of Health [DoH], 2012). This would contribute towards supporting SPSPs as a workforce and avoid overbearing on their workload to support research recruitment.

Underpinning all the factors discussed previously, is the use of a person-centred approach to social prescribing research. SPSPs spoke of the fluctuations in health of service users and the impact this had on their capability and motivation to participate. Previous research attests to this, reporting on the regularly observed high dropout rate in social prescribing research (Archer-Kuhn et al., Citation2022; Negrin et al., Citation2022; Treweek et al., Citation2018). Enabling flexible engagement (e.g. the option to delay participation and re-engage later) would help to address retention rates in social prescribing research. Research could also consider providing options for the conduct of data collection, for example using a range of phone, video, in person or written methods for collecting qualitative data. But critically the choice of data collection methods should be reflective of the population needs.

Strengths and limitations

A strength of this study is that the findings are evidence-informed and based on first-hand experiences of the challenges associated with recruitment to research in social prescribing contexts. Critically, recommendations for research activity are derived from the perspective of SPSPs and not those of service users. Therefore, further work is needed to elicit the perspectives of service users on the barriers and enablers to recruitment and retention.

A potential limitation of this research is the lack of the perspective from the wider link worker workforce employed within the NHS. Following the introduction of the NHS workforce development framework for link workers, introduced in January 2023, there are substantially more link workers employed by the NHS (NHS England, Citation2023). Therefore, their perspective warrants further investigation to understand whether barriers and enablers to recruitment and retention for social prescribing research in NHS settings differ from those identified in this study.

The sample size within this research was small with ten participants. However, in addition to the three principles of data saturation, where a non-statistical method of establishing data saturation was used, the total number of interviews conducted for the purpose of this research fell within the nine to seventeen interview range reported by Hennink and Kaiser (Citation2022). Based on the complexity of the research questions asked within the topic guide, the nature of the analysis, and the breadth/complexity of discussion topics, data saturation was determined to be achieved by ten interviews (Francis et al., Citation2010; Hennink & Kaiser, Citation2022).

Conclusions

The key implications arising from this research are a need for more accessible and person-centred strategies for strengthening recruitment to, and sustained participation in, social prescribing research. Primary barriers focus on the accessibility of research, such as language and information about participation, and the lack of flexibility in recruitment methods and data collection. Social prescribing service providers are critical for supporting engagement of service users in research.

Disclaimer

The authors declare no relevant competing interests. The views expressed in this article are the authors own views and not an official position of their institutions.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (22.5 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data available within the article or its supplementary materials. This research was conducted as part of a Teesside University fully funded PhD studentship awarded to DF and LA, and held by MC.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Matthew Cooper

Matthew Cooper is a Post-Doc Research Associate with the NIHR Newcastle Patient Safety Research Collaborative at Newcastle University.

Jason Scott

Jason Scott is an Associate Professor of Health and Social Care Quality and a Chartered Psychologist (CPsychol) at Northumbria University.

Leah Avery

Leah Avery is a Professor of Applied Health Psychology and a Registered Health Psychologist at Teesside University.

Kirsten Ashley

Kirsten Ashley is a Post-Doc Research Associate and Chartered Psychologist at Teesside University.

Darren Flynn

Darren Flynn is a Professor of Applied Health and Social Care Research, and Health and Care Professions Council registered Practitioner Health Psychologist at Northumbria University.

References

- Archer-Kuhn, B., Beltrano, N. R., Hughes, J., Saini, M., & Tam, D. (2022). Recruitment in response to a pandemic: pivoting a community-based recruitment strategy to facebook for hard-to-reach populations during COVID-19. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 25(6), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2021.1941647

- Barbour, R. S. (2001). Checklists for improving rigour in qualitative research: a case of the tail wagging the dog? BMJ (Clinical Research ed.), 322(7294), 1115–1117. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.322.7294.1115

- Beskow, L. M., Friedman, J. Y., Hardy, N. C., Lin, L., & Weinfurt, K. P. (2010). Simplifying informed consent for biorepositories: stakeholder perspectives. Genetics in Medicine: official Journal of the American College of Medical Genetics, 12(9), 567–572. https://doi.org/10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181ead64d

- Bonisteel, I., Shulman, R., Newhook, L. A., Guttmann, A., Smith, S., & Chafe, R. (2021). Reconceptualizing recruitment in qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 20, 160940692110424. https://doi.org/10.1177/16094069211042493

- Cooper, M., Avery, L., Scott, J., & Flynn, D. (Eds.). (2022, August 23–27). Social prescribing professionals perspectives on the barriers and enablers to the design and enablers to the design and delivery of services [Paper presentation]. 36th Annual Conference of the European Health Psychology Society: EHPS 2022, Slovakia.

- Cooper, M., Flynn, D., Avery, L., Ashley, K., Jordan, C., Errington, L., & Scott, J, (Eds.). (2022). A thematic synthesis of barriers and enablers to engagement with social prescribing interventions targeting mental health. Teesside University School of Health and Life Sciences Research Conference, Teesside University, United Kingdom.

- Cooper, M., Avery, L., Scott, J., Ashley, K., Jordan, C., Errington, L., & Flynn, D. (2022). Effectiveness and active ingredients of social prescribing interventions targeting mental health: a systematic review. BMJ Open, 12(7), e060214. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-060214

- Cooper, M., Flynn, D., Avery, L., Ashley, K., Jordan, C., Errington, L., & Scott, J. (2023). Service user perspectives on social prescribing services for mental health in the UK: A systematic review. Perspectives in Public Health, 143(3), 135–144. https://doi.org/10.1177/17579139231170786

- Costa, A., Sousa, C. J., Seabra, P. R. C., Virgolino, A., Santos, O., Lopes, J., Henriques, A., Nogueira, P., & Alarcão, V. (2021). Effectiveness of social prescribing programs in the primary health-care context: a systematic literature review. Sustainability, 13(5), 2731. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13052731

- Coughlan, M., Cronin, P., & Ryan, F. (2007). Step-by-step guide to critiquing research. Part 1: quantitative research. British Journal of Nursing (Mark Allen Publishing), 16(11), 658–663. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2007.16.11.23681

- Crowhurst, I., & Kennedy-Macfoy, M. (2013). Troubling gatekeepers: Methodological considerations for social research (pp. 457–462). Taylor & Francis.

- Daly, D., Hannon, S., & Brady, V. (2019). Motivators and challenges to research recruitment–a qualitative study with midwives. Midwifery, 74, 14–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2019.03.011

- de Farias, B. G., Dutra-Thomé, L., Koller, S. H., & de Castro, T. G. (2021). Formulation of themes in qualitative research: Logical procedures and analytical paths. Trends in Psychology, 29(1), 155–166. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43076-020-00052-0

- Department of Health (DoH). (2012). Attributing the Costs of Health and Social Care Research & Development (AcoRD). Department of Health.

- Edwards, R. (2013). Power and trust: An academic researcher’s perspective on working with interpreters as gatekeepers. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 16(6), 503–514. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2013.823276

- Francis, J. J., Johnston, M., Robertson, C., Glidewell, L., Entwistle, V., Eccles, M. P., & Grimshaw, J. M. (2010). What is an adequate sample size? Operationalising data saturation for theory-based interview studies. Psychology & Health, 25(10), 1229–1245. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870440903194015

- Grant, A. (2011). Fear, confusion and participation: Incapacity benefit claimants and (compulsory) work focused interviews. Research, Policy and Planning, 28(3), 161–171.

- Haley, S. J., Southwick, L. E., Parikh, N. S., Rivera, J., Farrar-Edwards, D., & Boden-Albala, B. (2017). Barriers and strategies for recruitment of racial and ethnic minorities: perspectives from neurological clinical research coordinators. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 4(6), 1225–1236. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-016-0332-y

- Hallsworth, K., Dombrowski, S. U., McPherson, S., Anstee, Q. M., & Avery, L. (2020). Using the theoretical domains framework to identify barriers and enabling factors to implementation of guidance for the diagnosis and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a qualitative study. Translational Behavioral Medicine, 10(4), 1016–1030. https://doi.org/10.1093/tbm/ibz080

- Halpern, S. D. (2011). Financial incentives for research participation: Empirical questions, available answers and the burden of further proof. The American Journal of the Medical Sciences, 342(4), 290–293. https://doi.org/10.1097/MAJ.0b013e3182297925

- Hennink, M., & Kaiser, B. N. (2022). Sample sizes for saturation in qualitative research: A systematic review of empirical tests. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 292, 114523. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114523

- Isaacs, T., Murdoch, J., Demjén, Z., & Stevenson, F. (2022). Examining the language demands of informed consent documents in patient recruitment to cancer trials using tools from corpus and computational linguistics. Health (London, England: 1997), 26(4), 431–456. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363459320963431

- Janesick, V., & Peer, D. (2015). The Blackwell encyclopedia of sociology. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

- Kannan, V., Wilkinson, K. E., Varghese, M., Lynch-Medick, S., Willett, D. L., Bosler, T. A., Chu, L., Gates, S. I., Holbein, M. E. B., Willett, M. M., Reimold, S. C., & Toto, R. D. (2019). Count me in: using a patient portal to minimize implicit bias in clinical research recruitment. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association: JAMIA, 26(8–9), 703–713. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocz038

- Kiely, B., Croke, A., O’Shea, M., Boland, F., O’Shea, E., Connolly, D., & Smith, S. M. (2022). Effect of social prescribing link workers on health outcomes and costs for adults in primary care and community settings: A systematic review. BMJ Open, 12(10), e062951. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2022-062951

- Kraft, S. A., Constantine, M., Magnus, D., Porter, K. M., Lee, S. S.-J., Green, M., Kass, N. E., Wilfond, B. S., & Cho, M. K. (2017). A randomized study of multimedia informational aids for research on medical practices: Implications for informed consent. Clinical Trials (London, England), 14(1), 94–102. https://doi.org/10.1177/1740774516669352

- McFadyen, J., & Rankin, J. (2016). The role of gatekeepers in research: Learning from reflexivity and reflection. GSTF Journal of Nursing and Health Care (JNHC), 4(1).

- McNeill, P. (1997). Paying people to participate in research: Why not? Bioethics, 11(5), 390–396. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8519.00079

- Namageyo-Funa, A., Rimando, M., Brace, A., Christiana, R., Fowles, T., Davis, T., Martinez, L., & Sealy, D.-A. (2014). Recruitment in qualitative public health research: Lessons learned during dissertation sample recruitment. The Qualitative Report, 19(4), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2014.1282

- Natale, P., Saglimbene, V., Ruospo, M., Gonzalez, A. M., Strippoli, G. F., Scholes-Robertson, N., Guha, C., Craig, J. C., Teixeira-Pinto, A., Snelling, T., & Tong, A. (2021). Transparency, trust and minimizing burden to increase recruitment and retention in trials: A systematic review. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 134, 35–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2021.01.014

- National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIFHAC). (2022). Payment guidance for researchers and professionals. NIFHAC.

- Negrin, K. A., Slaughter, S. E., Dahlke, S., & Olson, J. (2022). Successful recruitment to qualitative research: A critical reflection. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 21, 160940692211195. https://doi.org/10.1177/16094069221119576

- Newington, L., & Metcalfe, A. (2014). Factors influencing recruitment to research: qualitative study of the experiences and perceptions of research teams. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 14(1), 10. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-14-10

- NHS England. (2023). Workforce development framework: Social prescribing link workers. NHS England. [cited 2024 26/03/2024]. Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/long-read/workforce-development-framework-social-prescribing-link-workers/.

- NHS lnu. (2022, November 9). Online version of the NHS long term plan 2022. https://www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/online-version/.

- Patel, M. X., Doku, V., & Tennakoon, L. (2003). Challenges in recruitment of research participants. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 9(3), 229–238. https://doi.org/10.1192/apt.9.3.229

- Perez, D., Murphy, G., Wilkes, L., & Peters, K. (2022). One size does not fit all–overcoming barriers to participant recruitment in qualitative research. Nurse Researcher, 30(1), 24–30. https://doi.org/10.7748/nr.2022.e1815

- Peters, P., Smith, A., Funk, Y., & Boyages, J. (2016). Language, terminology and the readability of online cancer information. Medical Humanities, 42(1), 36–41. https://doi.org/10.1136/medhum-2015-010766

- Resnik, D. B. (2015). Bioethical issues in providing financial incentives to research participants. Medicolegal and Bioethics, 5, 35–41. https://doi.org/10.2147/MB.S70416

- Ridge, D., Bullock, L., Causer, H., Fisher, T., Hider, S., Kingstone, T., Gray, L., Riley, R., Smyth, N., Silverwood, V., Spiers, J., & Southam, J. (2023). ‘Imposter participants’ in online qualitative research, a new and increasing threat to data integrity? Health Expectations: An International Journal of Public Participation in Health Care and Health Policy, 26(3), 941–944. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.13724

- Ritchie, J., Lewis, J., Nicholls, C. M., & Ormston, R. (2013). Qualitative research practice: A guide for social science students and researchers. Sage.

- Rose, D., & Kalathil, J. (2019). Power, privilege and knowledge: The untenable promise of co-production in mental “health. Frontiers in Sociology, 4, 57. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsoc.2019.00057

- Ryan, F., Coughlan, M., & Cronin, P. (2007). Step-by-step guide to critiquing research. Part 2: Qualitative research. British Journal of Nursing (Mark Allen Publishing), 16(12), 738–744. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2007.16.12.23726

- Sheridan, R., Martin-Kerry, J., Hudson, J., Parker, A., Bower, P., & Knapp, P. (2020). Why do patients take part in research? An overview of systematic reviews of psychosocial barriers and facilitators. Trials, 21(1), 840. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-020-04793-2

- Spall, S. (1998). Peer debriefing in qualitative research: Emerging operational models. Qualitative Inquiry, 4(2), 280–292. https://doi.org/10.1177/107780049800400208

- Tierney, S., Wong, G., Roberts, N., Boylan, A.-M., Park, S., Abrams, R., Reeve, J., Williams, V., & Mahtani, K. R. (2020). Supporting social prescribing in primary care by linking people to local assets: a realist review. BMC Medicine, 18(1), 49. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-020-1510-7

- Treweek, S., Pitkethly, M., Cook, J., Fraser, C., Mitchell, E., Sullivan, F., Jackson, C., Taskila, T. K., & Gardner, H. (2018). Strategies to improve recruitment to randomised trials. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2018(2), 1465–1858. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.MR000013.pub6

- Vallotton, M. B. (2010). Council for international organizations of medical sciences perspectives: Protecting persons through international ethics guidelines. International Journal of Integrated Care, 10 Suppl(Suppl), e008. https://doi.org/10.5334/ijic.478

- Van Epps, H., Astudillo, O., Martin, Y. D. P., & Marsh, J. (2022). The Sex and Gender Equity in Research (SAGER) guidelines: Implementation and checklist development. European Science Editing, 48, e86910. https://doi.org/10.3897/ese.2022.e86910

- Wakefield, J. R. H., Kellezi, B., Stevenson, C., McNamara, N., Bowe, M., Wilson, I., Halder, M. M., & Mair, E. (2022). Social Prescribing as ‘Social Cure’: A longitudinal study of the health benefits of social connectedness within a Social Prescribing pathway. Journal of Health Psychology, 27(2), 386–396. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105320944991

- Wallerstein, N., Muhammad, M., Sanchez-Youngman, S., Rodriguez Espinosa, P., Avila, M., Baker, E. A., Barnett, S., Belone, L., Golub, M., Lucero, J., Mahdi, I., Noyes, E., Nguyen, T., Roubideaux, Y., Sigo, R., & Duran, B. (2019). Power dynamics in community-based participatory research: A multiple–case study analysis of partnering contexts, histories, and practices. Health Education & Behavior: The Official Publication of the Society for Public Health Education, 46(1_suppl), 19S–32S. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198119852998

- Webber-Ritchey, K. J., Aquino, E., Ponder, T. N., Lattner, C., Soco, C., Spurlark, R., & Simonovich, S. D. (2021). Recruitment strategies to optimize participation by diverse populations. Nursing Science Quarterly, 34(3), 235–243. https://doi.org/10.1177/08943184211010471

- Wilson, S. (2020). ‘Hard to reach’parents but not hard to research: A critical reflection of gatekeeper positionality using a community-based methodology. International Journal of Research & Method in Education, 43(5), 461–477. https://doi.org/10.1080/1743727X.2019.1626819

- Wu, M.-J., Zhao, K., & Fils-Aime, F. (2022). Response rates of online surveys in published research: A meta-analysis. Computers in Human Behavior Reports, 7, 100206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chbr.2022.100206

- Yamada, J., Potestio, M. L., Cave, A. J., Sharpe, H., Johnson, D. W., Patey, A. M., Presseau, J., & Grimshaw, J. M. (2018). Using the theoretical domains framework to identify barriers and enablers to pediatric asthma management in primary care settings. The Journal of Asthma: official Journal of the Association for the Care of Asthma, 55(11), 1223–1236. https://doi.org/10.1080/02770903.2017.1408820

- Zutlevics, T. (2016). Could providing financial incentives to research participants be ultimately self-defeating? Research Ethics, 12(3), 137–148. https://doi.org/10.1177/1747016115626756

Appendix 1

Topic Guide – Exploring service providers’ perceptions of the barriers and enablers to recruitment of service users into social prescribing research.

Question 1.

In your current service have you experienced any challenges to participant/patient engagement in social prescribing services and research?

Prompts

What are they?

How were they identified?

What did they do about it?

Methods of interview – telephone vs video call

Information – paper vs email, letter

Devices/ skills level of people they work with

Trust or forming that relationship.

Digital exclusion

Stigma

Time to engage with service users.

Challenges experienced when doing research or data collection with your service users.

Question 2.

Are there things you could perceive that would mean people were reluctant to take part in research?

Different research methods (interview, focus group, email, phone, letter, etc.)

Question 3.

From the challenges and barriers, you have identified, how would you go about overcoming them?

Identification

Resources

Time frame/ funds