Abstract

The school type can greatly affect the posture and psychological state of adolescent girls by controlling many factors, such as school bag load and way of carriage, furniture-anthropometry degree of matching, and availability of resources. This study aimed to compare postural changes and psychological aspects of adolescent Egyptian girls, attending two different school types: public versus private schools. An observational study was conducted on 200 adolescent girls, whose ages ranged from 14 to 17 years, with a body mass index of 19–25 kg/m2, selected from two different school types (two public and another two private) at El-Sharkia government, Egypt. They were assigned into two equal groups: group (A), including 100 public schoolgirls, and group (B) involving 100 international schoolgirls. Postural and mechanical changes were assessed at the head, rib cage, shoulders, hips, and knees in both groups by the Posture Screen® Mobile app and a photographic method from lateral and frontal views while standing. Assessing anxiety, depression, and stress signals was done using depression anxiety stress scales-21. The girls of public and international schools had different schoolbag characteristics but assumed the same poor posture. The results indicated more significant changes in the public schoolgirls of group (A) (p ˂ 0.05) in the head shift, shoulder tilting, hip shift, hip tilting, total shift, and total tilting, compared to the international girls of the group (B), while there were more changes in head weight, and effective head weight, indicating more forward head in the international girls of the group (B). For psychological aspects, the public-school girls had statistically significantly higher stress and anxiety scores (p ˂ 0.05) than the international schoolgirls. Thus, it could be concluded that the school type may affect the posture and psychology of Egyptian adolescent girls, as the girls at the public schools had more coronal postural changes together with more stress and anxiety than the girls enrolled in the private schools, while girls of the private schools had more forward head posture.

1. Introduction

Human posture is known to continuously undergo alterations over time that normally begin during school-age, because of bodily growth and development (Coelho et al., Citation2014). Negative postural changes are seen as a major determinant of the musculoskeletal system’s health that is related to many painful and debilitating conditions (Ferreira et al., Citation2010). Having unhealthy postural changes in adolescence, especially those affecting the spinal column, can predict the development of degenerative spinal conditions in adulthood, giving the rise to a possible public health problem (Sedrez et al., Citation2015).

High incidences of postural deviations and back pain were reported in students of school age, with more prevalence among girls than boys (Da Rosa Bn et al., Citation2017). Also, a high incidence of back pain was stated among Egyptian school girls (Ibrahim, Citation2012). Common reasons behind those deviations and the resultant backache are prolonged incorrect sitting position, furniture-anthropometry mismatch, furniture misuse, and backpack characteristics (Sampaio et al., Citation2016). A study was designed by Jurak et al. (Jurak et al., Citation2019) to evaluate the effect of the schoolbag on the standing posture of 76 school-age children. It found that the schoolbag has resulted in a change of the center of gravity by shifting it anteriorly in the sagittal, axial, and coronal axes. Also, it affected the craniocervical and craniovertebral angles (Jurak et al., Citation2019). Moreover, spinal symptoms appearing in the adolescent student population were found to be related to their anthropometric dimensions as well as their school furniture (Cardon et al., Citation2004). The previously mentioned reasons all present consistently applied demands on the body causing body asymmetries and can negatively impact the quality of life of adolescent girls and continue to affect them through their adulthood (Penha et al., Citation2005).

On the other hand, a systematic review with meta-analysis has indicated psychological features (i.e., depression, anxiety, and feeling tense) as the most probable causes of young individuals’ back pain (Beynon et al., Citation2020). According to the World Health Organization, mental health issues are expressed by around 10–20% of children and adolescents wide-world (Keles et al., Citation2020). Those conditions are associated with social and educational impairments, poor physical health, and deliberate self-harm. That can signal long-term mental health difficulties and cause high distress for adolescents and their families (Jones et al., Citation2020).

The school type was claimed to have a significant effect on the physical state of school-age children and adolescents, as students attending different school types are faced with varying stressors. For instance, in a study by Castellucci et al. (Castellucci et al., Citation2015) conducted in Chile, the school furniture dimensions’ mismatching was shown to be varied with the type of the school, with the public-school type being the one with the highest mismatch, compared to the semi-public and private types. That high degree of furniture mismatching with the students’ anthropometry has been stated to cause postural overload and consequent back pain (Batistão et al., Citation2012). Similarly, a cross-sectional Ethiopian study (Delele et al., Citation2018), done on 723 children selected from six elementary schools, has claimed that the school type could greatly affect the students’ physical state, as they found that the self-reported musculoskeletal pain was more prevalent across the governmental (68%) versus the private schools (51%). At the same time, a Nigerian cross-sectional study on 1,785 secondary school students reported that students attending private schools carry heavier schoolbag weights, compared to those of public schools (Hamzat et al., Citation2014).

Furthermore, the school type was shown to, also, affect the degree of depression and anxiety the female adolescent may have (RK Kumar et al., Citation2022). According to Kumar et al. (RK Kumar et al., Citation2022), students enrolled in public schools had higher degrees of depression but lower stress than those in private schools. These findings would raise the attention for postural screening and the evaluation of psychological changes in the girls attending different school types to early detect and, consequently, manage those possible changes. Preliminary screening for these psychological changes could be the first step toward the prevention of more serious conditions (Dolphens et al., Citation2012).

The above-mentioned studies (Castellucci et al., Citation2015; Delele et al., Citation2018; Hamzat et al., Citation2014; RK Kumar et al., Citation2022) have presented a strong association between the school type and various factors affecting the posture and psychology of school-age children and adolescents. Yet, research is lacking in exploring the effect of attending a certain school type on the posture and psychological aspects of adolescent girls. Also, no studies were found to investigate that association among Egyptian students. Based on the previous research, it could be hypothesized that the posture and psychological state of Egyptian adolescent girls may be affected by the school type they attend due to facing different forms of stressors. So, this study was done to compare postural changes and psychological aspects occurring in Egyptian adolescent girls in public schools versus international schools.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study design, participants, and settings

2.1.1. Study design

The study was designed as an observational study. Approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board at the Faculty of Physical Therapy, Cairo University before study commencement (No: P.T.REC/012/002023), and the study had a registered clinical trial no: [NCT03847259]. The study followed the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki regarding the conduct of human research and was carried out between March 2019 and December 2019. All school principals recorded consent for acceptance to share in the study. All girls involved agreed to participate in the study.

2.1.2. Participants

To determine the sample size needed for the present study, based on the study’s primary outcome, the DASS-21, a subject-item ratio of 1:5 was utilized. According to that ratio, 5 × 21 = 105 Egyptian girls were needed. To counteract possible dropouts, a sample of 200 Egyptian adolescent girls was considered. An initial convenient sample of 240 adolescent girls, who were enrolled in two different secondary school types (two public and another two private) at El-Sharkia government, Egypt, were recruited, using flyers distributed to the schools’ classes and by direct interviews.

Their ages ranged from 14 to 17 years, and their body mass index (BMI) was from 19 to 25 kg/m2. They had regular ovulatory menstrual cycles (i.e., established 6 months to 3 years before study enrollment). Girls were excluded if they had a chronic respiratory disease, a history of the upper limb, lower limb, and/or back deformities. Underweight girls, those with unestablished menstrual cycles, and/or girls complaining of severe menstrual pain were also excluded from the study.

2.1.3. Study settings and assessment of outcome measures

Adolescent females were divided into two equal groups, group (A); which involved a hundred public schoolgirls, and group (B); which involved a hundred international schoolgirls. All girls were asked about the style of their schoolbag [backpack (traditional vs with front pockets), one strap design] and were observed for sitting posture during studying (slumped vs. upright or supported posture, crossed vs uncrossed legs). Personal data, including age, height, weight, BMI, and menstrual history, and the answers to the previous questions were recorded in a recording data sheet, Figure . The primary outcome of the study was to assess the psychological status of the involved schoolgirls, in terms of depression, anxiety, and stress. The secondary study outcome was to evaluate posture deviations and assess mechanical changes at the head, rib cage, shoulders, hips, and knees from lateral and frontal views in a standing position.

Figure 1. Classification of schoolbag and sitting characteristics data of schoolgirls involved in the study.

All girls were evaluated by a single examiner, respecting the same methodology, using Posture Screen® Mobile (PSM) app, version 8.5, developed by Posture Co. Inc. (Trinity, FL, USA), installed from the AppStore. This app is known for its validity and reliability in evaluating body posture. It provides simple, fast, and easily reproducible examination from a standing position. Also, it does not require in-depth knowledge of posture science (Iacob et al., Citation2020; Kaplan, Citation2018; Szucs & Brown, Citation2018).

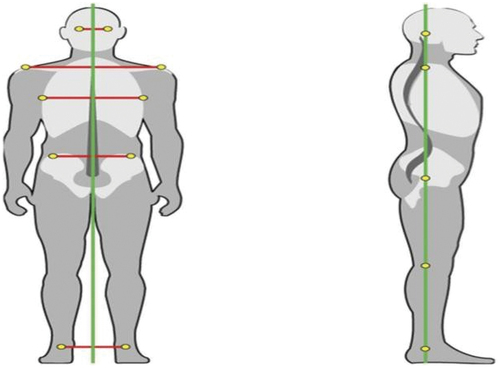

To assess postural changes, a stable stand and water balance were used, the first to fix the mobile and the latter for the mobile surface adjustment. Each girl was asked to stand barefoot on a specific area of the floor with a one-foot distance between the two feet in front of a camera at an equal distance (1.5 cm) for all trials. Two photographs were taken with an iPhone 6, and the reference points were manually placed, as illustrated in Figure , Table . After placing the reference points, the measurements were automatically made by the PSM app, and the deviation means from the medial and vertical lines of 13 parameters, as listed in Table , were displayed. Then, the examiner obtained the results in a PDF file format (Iacob et al., Citation2020).

Table 1. The reference points used, and the variables evaluated with the PSM application

In general, the posture was analyzed from the region above to the region below. Head, shoulder, and ribs’ angles were all measured off the horizontal, while the ribs’ linear offset was measured against the hips’ midpoint, the and hips’ linear offset was measured against the feet midpoint. The green plumb line was used for the participants’ education, and it was drawn vertically at the midpoint between the foot digitized points in the frontal view up from the ankle in the lateral view. From the side, all translations were measured against the next lowest point, with the linear head shift being the horizontal distance of the ear point compared to the shoulder point (Iacob et al., Citation2020). The app was able to detect the change in the variables selected, including sagittal and coronal plane translations and angulations with intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) reaching up to 0.84 (Szucs & Brown, Citation2018).

To assess the psychological aspects of the girls of both groups, the Arabic version of the depression anxiety stress scale-21 (DASS-21), the short form of the original DASS-42, was utilized (Appendix 1; Alamri et al., Citation2020). This scale was developed to provide a self-reported degree of anxiety, depression, and stress signals in multiple age groups, with validity, good reliability, and internal consistency. It consists of 21 items, seven for each of the three subscales (Dahm et al., Citation2013). Each girl in both groups was instructed to rate each item of the three domains by how it was closely applied to her emotions experienced over the last week. The answers were scored on a 4-point Likert scale starting with 0, indicating “not applied to me at all” till 3 which is “applied to me most of the time”. Items for depression were 3, 5, 10, 13, 16, 17, and 21, for anxiety, 2, 4, 7, 9, 15, 19, and 20 and for stress, items were 1, 6, 8, 11, 12, 14, 18. Scoring for each subscale and the total scale was done by summing up the score for each item in the subscale and the score of the three domains, respectively, then multiplying it by 2, to be comparable with the original DASS-42 scale scoring. Thus, the subscales’ total scores ranged from 0 to 42, while the total DASS scoring ranged from 0 to 120 (Alamri et al., Citation2020). The greater the scores, the higher the degree of level of psychological issues (Dahm et al., Citation2013; Jiang et al., Citation2020). For clinical purposes, degrees of severity were characterized using familiar severity labels (mild-moderate-severe-extremely severe), used by Alamri et al., to describe the full range of scores for each DASS axis (Alamri et al., Citation2020).

2.1.4. Data and statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS (version 25 for windows, SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL), for all study variables including postural assessment variables from the frontal view (head deviation, head deviation angle, shoulders deviation, shoulders deviation angle, chest deviation, hip deviation, and hip deviation angle), postural assessment from lateral view (estimated head weight, physically calculated head weight, head deviation, shoulder deviation, and knee deviation), as well as assessment of depression, anxiety, and stress levels in both groups.

Firstly, the data were explored for normality assumption, and descriptive data like age, weight, height, and BMI were presented by mean and standard deviation, while to show the significant differences between both groups regarding the study variables (postural deviations from two views and DASS-21 scores), Mann Whitney test and Chi-Square test were used. The significance level was determined at p ≤ 0.05, where p = probability level.

3. Results

Two hundred forty Egyptian adolescent girls were initially selected and explored for eligibility. Twenty-eight were excluded for having back deformities (kyphosis, scoliosis), irregular menstrual cycles, absent menstrual cycles, and being underweight, while twelve girls refused to be included in the study, Figure .

3.1. Demographic data

As shown in Table , for demographic data, there were no significant differences in age, weight, height, or BMI (p > 0.05) between both groups.

Table 2. Demographics of the girls, postural deviations, and DASS-21 scoring in both groups

3.1.1. Schoolbag characteristics

According to the girls’ answers regarding their schoolbag style and the way of carrying it, 11% of public schoolgirls (n = 11) had a single-strap schoolbag, while 89% (n = 89) had a double-strap backpack, 82% of them (n = 73) were of the traditional type and the rest (n = 16) were backpacks with front pockets. Regarding the way of backpack carriage, about 79.8% (n = 71) of the girls carry their backpacks on both shoulders while only 20.2% of them (n = 18) were used to carry their bags on one shoulder.

For the international schoolgirls, the preferred schoolbag style was that of a single strap design, with an incidence of 81% (n = 81), whereas only 19% (n = 19) of the girls had backpacks. Of them, about 68.4% (n = 13) had backpacks with front pockets, and only 31.6% (n = 6) had traditional backpacks. The answers of the international schoolgirls about the preferred way of carrying their backpacks revealed that about 57.9% of the girls (n = 11) choose to carry their bag on both shoulders, and 42.1% of them (n = 8) carry their bag on one shoulder.

3.2. Sitting posture during classroom studying

About 10% (n = 10) of the public schoolgirls versus 21% (n = 21) of the international schoolgirls were noticed to assume a slumped posture, while 83% (n = 83) versus 63% (n = 63) of public and international schoolgirls, respectively, were sitting upright and only 7% (n = 7) of public versus 16% (n = 16) of international schoolgirls were sitting supported. For the legs’ posture, 61% (n = 61) of public versus 74% (n = 74) of international girls were found to cross their legs during sitting.

3.2.1. Postural deviations

Table shows between-group comparisons regarding the frontal and sagittal postural changes. For deviations from the frontal view, results revealed statistically significant differences between both groups in most of the frontal view postural measures (the head shift; p = 0.043*, shoulder tilting; p < 0.001*, hip shift; p = 0.001*, hip tilting; p < 0.001*, total shift; p = 0.004*, and total tilting; p < 0.001*). These significant differences were more observed in the public school group (A), compared to the international school group (B).

For deviations from the sagittal view, between groups comparison revealed a significant difference between both groups in head weight (p < 0.001*) and effective head weight (p = 0.002*) in favor of the international school group (B), compared to the public-school group (A). Conversely, no significant differences (p > 0.05) were found in any other variables, Table .

3.3. Psychological state assessment

Considering the DASS-21 scoring, between groups comparison showed a significant difference between both groups in both anxiety and stress scores with (p = 0.037* and p = 0.044*), respectively, with a more increase in favor of the public-school group (A), compared to the international school group (B), Table . Moreover, as presented in Table , the frequency distribution of the severity degree of the psychological complaints indicated a statistically significant increase in the degree of stress severity (p = 0.012*) among the girls in the public-school group (A), but no significant differences between both groups were observed in either of the degrees of depression or anxiety severity (p > 0.05).

Table 3. The frequency distribution of the severity degree of depression, anxiety, and stress between both groups (A&B)

4. Discussion

The purpose of the current study was to investigate whether there was an effect of attending different school types on the posture and psychological status of Egyptian adolescent girls in public versus international schools. It was hypothesized that there would be an effect of attending different school types on the physical and psychological aspects of the girls attending them. That hypothesis was confirmed by the study findings.

The study results revealed that there were apparent coronal and sagittal postural deviations in both public and international schoolgirls, with more coronal-view postural deviations in public schoolgirls of the group (A), while girls in both groups had nearly the same degree of sagittal-view deviation, except for forward-head deviation, which was more obvious in international schoolgirls of the group (B), indicating more load at the head and neck due to having higher effective head weight. Also, the results have shown an elevation in the level of depression, anxiety, and stress in all girls of both school types, with more stress and anxiety experienced by public schoolgirls.

For postural deviations observed in the study, these findings came in agreement with Neves et al. (Neves & Leite, Citation2016), who found that all elementary school students demonstrated some sort of postural dysfunction or alteration following postural assessment. These results could be explained by Cardon et al. (Cardon et al., Citation2004), who assumed that the posture of young students might be affected by the school type and school furnishings. The same reason was stated by Desouzart and Gagulic (Desouzart & Gagulic, Citation2017), who proposed that the observed shoulder asymmetry among students could be related to the way of backpack carrying and transport and the size and weight of the bags. They have also found postural deviations including all body segments, attributed to students’ improper sitting posture and lifting objects off the floor.

Concerning the postural deviations found in the schoolgirls of both groups in head shift, shoulder tilt, hip shift, and hip tilting, the results were congruent with Penha et al. (Penha et al., Citation2005), who evaluated postural deviations in students and found that there were postural changes in the form of head tilt, together with hip shoulder imbalance. The same findings were stated by Santos et al. (Santos et al., Citation2009), who showed that the main postural deviations were found in public school students in the form of shoulder imbalance, protracted shoulder, and cervical region, medial hip rotation, and head tilt. The opposite was true in the study of Detsch et al. (Detsch et al., Citation2007), who observed a higher prevalence of anteroposterior postural changes in adolescent girls who did not go to school or have gone to a public school type, while lateral changes were more prominent in students who were watching TV and using technology.

In this study, most public schoolgirls were found to have a traditional backpack, compared to the international schoolgirls, who had backpacks with front pockets. This notice could explain the difference in postural deviations reported between both schoolgirls’ groups. According to Fiolkowski et al. (Fiolkowski et al., Citation2006), the backpack styles appeared to greatly affect the students’ posture during walking. For instance, students who used traditional backpacks had a higher level of forward flexion at the hips, compared to those carrying front packs. Likewise, an Egyptian study by Mosaad and Abdel Aziem (Mosaad & Abdel-Aziem, Citation2015) has claimed that carrying a double-sided bag has regained postural balance and resulted in better head posture.

Additionally, when the girls were observed for their method of schoolbag carrying, for unknown reasons, most of the girls attending public schools were carrying their backpacks on both shoulders, while the majority of the international schoolgirls preferred either carrying their backpacks on one shoulder or using the single strap backpack design. That could justify the higher sagittal postural changes found in international schoolgirls. The same findings were reported by Mandreker et al. (Mandrekar et al., Citation2019), who studied the effect of carrying schoolbags on the cervical and shoulder posture of 70 adolescents and found that carrying the bag unilaterally resulted in significant changes in the sagittal plane, compared to fewer changes with carrying the bag bilaterally. Also, Mosaad et al. (Mosaad et al., Citation2014) have indicated, in their study, that bilateral carriage of the schoolbag has caused lower and more symmetrical muscular activity when compared to the unilateral way of carriage. Unilateral load carriage causes the body to compensate for the extra load placed on one body side to keep the center of gravity within the body’s base of support. The net result of such compensation is the leaning of the trunk away from the direction of the load (Samuel, Citation2011).

Unlike other schoolbag characteristics, the weight of the bag has been a matter of debate. Many studies (Chansirinukor et al., Citation2001; Marsh et al., Citation2006; Sankaran et al., Citation2021) have confirmed the negative influence of the schoolbag weight and the time of carrying that weight on pain, discomfort, as well as cervical and shoulder posture. However, Mandreker et al. (Mandrekar et al., Citation2019) have concluded that even with a schoolbag weighing less than 10%, significant postural alternations could occur. They stated that carrying a schoolbag during dynamic activities (e.g., during walking) resulted in biomechanical changes along the cervical and shoulder regions, regardless of the weight carried. Also, Dockrell et al. (Dockrell et al., Citation2015) have found that neither schoolbag weight nor the duration of its carriage was linked to schoolbag-related unease. Thus, the assessment of schoolbag weight was not included in this study and more concern was given to other bag parameters (e.g., design, way of carrying).

Regarding sitting posture, most public and international schoolgirls were found to assume poor or inadequate postures in the form of slumped and/or upright unsupported postures. Only seven public and sixteen international students were sitting in a correct supported posture. Additionally, most of the girls in both school types were sitting with their legs crossed, with a higher percentage of international girls (74% vs. 61%). The same findings were reported by Kumar et al., Citation2015 (G Kumar et al., Citation2015). They found girls to be frequently sitting in erect posture (upright) with more lordosis, compared to boys. They explained that finding as girls are controlled by different behavioral and anatomical factors than boys of the same age. Similar results were proposed by Araújo et al. (Araújo et al., Citation2020), who found that female students presented a higher frequency of distant positions from the table and poorer lower limb position, compared to their boy counterparts. They also stated the presence of a link between altered lower limbs’ posture and both anterior head detection and pelvic retroversion, causing improper sitting posture. Poor sitting posture, especially when assumed for a long duration, could negatively impact trunk muscular activity, leading to pain, discomfort, and more serious consequences (Wong et al., Citation2019).

Such a high prevalence of poor posture found in both school types was a little unexpected. International students were supposed to assume better-supported postures compared to the public-school students, as the public-school type was previously found to have higher mismatching between the students’ anthropometric measures and school furniture (Castellucci et al., Citation2015). Similarly, almost all Egyptian governmental/public schools use furniture of the fixed type, which may cause a significant degree of mismatching. On the contrary, private/international schools have the availability of resources to offer modified and more adequately designed furniture. Nevertheless, international students had poor sitting postures even with the modifiable furniture offered to them. This highlights the importance and the need for postural screening and awareness about the correct posture regardless of the school type.

Another finding of the present study was the elevated level of depression, anxiety, and stress in the girls enrolled in both school types, with more stress and anxiety experienced by public schoolgirls than international schoolgirls. That finding agreed with Rask et al. (Rask et al., Citation2002), who stated a prevalence reaching up to 29% of mental disorders, affecting adolescents visiting the facilities of primary health care. Several factors were proposed as heavy school timetables, with limited time for dealing with the school’s various requirements. Also, parents’ and teachers’ unrealistic expectations and demands together with poor study habits comprise frequent sources of distress and anxiety and eventually can cause depression (Banerjee, Citation2011).

The results were congruent with Kumar et al. (RK Kumar et al., Citation2022), who concluded that the school type could influence the degree of psychological complaints of the students. They found that public school students complained of higher depression degrees than private school students. However, private school students had more stress than public school students, which contradicted our findings. The results from Kaczmarek and Trambacz-Oleszak (Kaczmarek & Trambacz-Oleszak, Citation2021) also disagreed with ours. In their cross-sectional study on 1846 adolescent Poland students, they found that neither the school type nor the student’s residence place was associated with a high level of perceived stress. Rather, gender and BMI were directly associated factors.

This study has several strong points, as it was carried out on a representative sample of 200 Egyptian adolescent girls and the anatomical landmarks were determined by PSM application, a valid, reliable, and accurate tool for posture assessment. None of the girls were obese. That made it easy to correctly detect landmarks, even with the girls having their clothing on. Also, the DASS-21 scale used was the Arabic-translated and validated version of the scale that enabled the females to understand the instructions and to accurately answer the questions.

Although the current study reveals objective data with statistically significant differences, the study had some limitations. Postural deviations were evaluated only from anterior and lateral views. Future studies are required to evaluate postural deviations from the posterior view. The psychological aspects could be assessed by other different tools to further confirm the effect on the psychology of adolescent girls attending different school types. Other schoolbag parameters as the bag strap length and weight needed to be evaluated and compared among girls of different school types. Also, other non-school-related habits (watching TV, sleeping habits, and physical exercises) should be investigated in future studies to control confounding factors that may, also, affect the posture and psychology of the students.

In a conclusion, the present study deduced a possible effect of the different school types on the posture and psychological aspects of a representative sample of Egyptian schoolgirls attending two different school types. The girls attending the two public secondary schools had different schoolbag aspects than the international schoolgirls but assumed similar bad postures. The girls of both school types had significant postural deviations in frontal and lateral directions, with higher coronal postural changes in the public schoolgirls, and more sagittal postural changes in the private schoolgirls. For the psychological aspects, the girls in both private and public schools had high degrees of negative emotions, with more stress and anxiety in public school girls than in international schools.

It is necessary to direct more attention to the type of furniture used in such school type. Changing the furniture into a more ergonomic or adaptable type could be costly but worthwhile. Also, Instructions about the negative impact of poor sitting postures on physical health as well as programs for muscle reeducation and postural awareness are a must. Postural training and ergonomic education are essential for students in both public and international schools, with more concerns for public school students, to minimize the occurrence of musculoskeletal disorders, pain, stress, and anxiety.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all individuals who contributed to the completion of this work.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Doaa Saeed

Doaa Saeed conceptualized and designed the study, collected, and interpreted data, drafted, performed revision, and reviewing of the manuscript, and agreed to hold responsibility and accountability for the article’s content.

Hamada Ahmed

Hamada Ahmed Conceptualized and designed the study, performed data analysis, interpretation, revision and reviewing of the manuscript and agreed to hold responsibility and accountability for the article’s content.

Fahima Metwally

Fahima Metwally Conceptualized and designed the study, supervised data collection, revised and critically reviewed the manuscript and agreed to hold responsibility and accountability for the article’s content.

Amel M. Yousef

Amel M. Yousef Conceptualized and designed the study, supervised data collection, revised and critically reviewed the manuscript and agreed to hold responsibility and accountability for the article’s content.

Ghada Koura

Ghada Koura Conceptualized and designed the study, supervised data collection, revised and critically reviewed the manuscript and agreed to hold responsibility and accountability for the article’s content.

Osama Ahmed Khaled

Osama Ahmed Khaled Conceptualized and designed the study, supervised data collection, revised and critically reviewed the manuscript and agreed to hold responsibility and accountability for the article’s content.

Mahitab M Yosri

Mahitab M Yosri Conceptualized and designed the study, interpreted data, drafted, performed revision, and reviewing of the manuscript, and agreed to hold responsibility and accountability for the article’s content.

References

- Alamri, H. S., Algarni, A., Shehata, S. F., Al Bshabshe, A., Alshehri, N. N., ALAsiri, A. M., Hussain, A. H., Alalmay, A. Y., Alshehri, E. A., Alqarni, Y., & Saleh, N. F. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and stress among the general population in Saudi Arabia during Covid-19 pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 17(24), 2020 Dec 99183. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17249183

- Araújo, L. G. L., Rodrigues, V. P., Figueiredo, I. A., & Medeiros, M. N. L. Association between sitting posture on school furniture and spinal changes in adolescents. Int J Adolesc Med Health, https://doi.org/10.1515/ijamh-2020-0179

- Banerjee, S. Effect of various counseling strategies on academic stress of secondary level students [ Ph.D. thesis], Punjab University 2011.

- Batistão, M. V., Sentanin, A. C., Moriguchi, C. S., Hansson, G. Å., Coury, H. J., & de Oliveira Sato, T. (2012). Furniture dimensions and postural overload for schoolchildren’s head, upper back and upper limbs. Work, 41 Suppl 1, 4817–17. https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-2012-0770-4817

- Beynon, A. M., Hebert, J. J., Hodgetts, C. J., Boulos, L. M., & Walker, B. F. (2020). Chronic physical illnesses, mental health disorders, and psychological features as potential risk factors for back pain from childhood to young adulthood: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Eur Spine J, March 29(3), 480–496. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-019-06278-6. Epub 2020 Jan 6. PMID: 31907659

- Cardon, G., De Clercq, D., De Bourdeaudhuij, I., & Breithecker, D. (2004). Sitting habits in elementary schoolchildren: A traditional versus a “moving school”. Patient Educ Couns, 54(2), 133–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0738-3991(03)00215-5

- Castellucci, H. I., Catalán, M., Arezes, P. M., & Molenbroek, J. F. (2015). Evaluation of the match between anthropometric measures and school furniture dimensions in Chile. Work, 53(3), 585–595. https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-152233

- Chansirinukor, W., Wilson, D., Grimmer, K., & Dansie, B. (2001). Effects of backpacks on students: Measurement of cervical and shoulder posture. Aust J Physiother, 47(2), 110–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0004-9514(14)60302-0

- Coelho, J. J., Graciosa, M. D., de Medeiros, D. L., da Silva Pacheco, S. C., Resende da Costa, L. M., & Kittel Ries, L. G. 2014. Influence of flexibility and gender on the posture of school children. Revista Paulista de Pediatria, 32(3), 223–228. English Edition. https://doi.org/10.1590/0103-0582201432312.

- Dahm, J., Wong, D., & Ponsford, J. (2013). Validity of the depression anxiety stress scales in assessing depression and anxiety following traumatic brain injury. J Affect Disord, 151(1), 392–396. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2013.06.011

- da Rosa B.N, Furlanetto, T. S., Noll, M., Da Rosa, B. N., Sedrez, J. A., Schmit, E. F. D., & Candotti, C. T. (2017). 4-year longitudinal study of the assessment of body posture, back pain, postural and life habits of schoolchildren. Motricidade, 13(4), 3–12. https://doi.org/10.6063/motricidade.9343

- Delele, M., Janakiraman, B., Bekele Abebe, A., Tafese, A., van de Water Atm, & van de Water, A. T. M. Musculoskeletal pain and associated factors among Ethiopian elementary school children. BMC Musculoskelet Disord, 2018 Jul 31 19(1), 276. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-018-2192-6

- Desouzart, G., & Gagulic, S. (2017). Analysis of postural changes in 2nd cycle students of elementary school. J Spine, 6(1), 1000357. https://doi.org/10.4172/2165-7939.1000357

- Detsch, C., Luz, A. M., Candotti, C. T., Oliveira, D. S. D., Lazaron, F., Guimarães, L. K., & Schimanoski, P. (2007). Prevalence of postural changes in high school students in a city in southern Brazil. Rev Panam Salud Publica= PAJPH, 21(4), 231–238. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1020-49892007000300006

- Dockrell, S., Simms, C., & Blake, C. (2015, November). Schoolbag carriage and schoolbag-related musculoskeletal discomfort among primary school children. Appl Ergon, 51, 281–290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apergo.2015.05.009

- Dolphens, M., Cagnie, B., Coorevits, P., Vanderstraeten, G., Cardon, G., Dʼhooge, R., & Danneels, L. (2012). Sagittal standing posture and its association with spinal pain: A school-based epidemiological study of 1196 Flemish adolescents before age at peak height velocity. Spine, 37(19), 1657–1666. https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0b013e3182408053

- Ferreira, E. A., Duarte, M., Maldonado, E. P., Burke, T. N., & Marques, A. P. (2010). Postural assessment software (PAS/SAPO): Validation and reliability. Clinics, 65(7), 675–681. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1807-59322010000700005

- Fiolkowski, P., Horodyski, M., Bishop, M., Williams, M., & Stylianou, L. Changes in gait kinematics and posture with the use of a front pack. Ergonomics, 2006 Jul 15 49(9), 885–894. https://doi.org/10.1080/00140130600667444. PMID: 16801234

- Hamzat, T. K., Abdulkareem, T. A., Akinyinka, O. O., & Fatoye, F. A. (2014, September). Backpack-related musculoskeletal symptoms among Nigerian secondary school students. Rheumatol Int, 34(9), 1267–1273. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-014-2962-x

- Iacob, S. M., Chisnoiu, A. M., Lascu, L. M., Berar, A. M., Studnicska, D., & Fluerasu, M. I. (2020). Is PostureScreen® Mobile app an accurate tool for dentists to evaluate the correlation between malocclusion and posture? Cranio, 38(4), 233–239. https://doi.org/10.1080/08869634.2018.1512197

- Ibrahim, A. H. (2012). Incidence of Back Pain in Egyptian School Girls: Effect of school bag weight and carrying way. World Appl Sci J, 17(11), 1526–1534. https://scholar.cu.edu.eg/sites/default/files/amalhassan/files/20.pdf

- Jiang, L. C., Yan, Y. J., Jin, Z. S., Hu, M. L., Wang, L., Song, Y., Li, N. N., Su, J., Wu, D. X., & Xiao, T. (2020 March). The depression anxiety stress scale-21 in Chinese hospital workers: reliability, latent structure, and measurement invariance across genders. Front Psychol, 6(11), 247. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00247. 2020 Apr 15.

- Jones, R. B., Thapar, A., Rice, F., Mars, B., Agha, S. S., Smith, D., Merry, S., Stallard, P., Thapar, A. K., Jones, I., & Simpson, S. A. (2020). A digital intervention for adolescent depression (MoodHwb): mixed methods feasibility evaluation. JMIR Ment Health, 7(7), e14536. https://doi.org/10.2196/14536

- Jurak, I., Rađenović, O., Bolčević, F., Bartolac, A., & Medved, V. The influence of the schoolbag on standing posture of first-year elementary school students. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2019 Oct 16 16(20), 3946. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16203946

- Kaczmarek, M., & Trambacz-Oleszak, S. School-related stressors and the intensity of perceived stress experienced by adolescents in Poland. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2021 Nov 10 18(22), 11791. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182211791

- Kaplan, D. Ö. (2018). Evaluating the effect of 12 weeks football training on the posture of young male basketball players. J Educ Train Stud, 6(10), 47–53. https://doi.org/10.11114/jets.v6i10.3423

- Keles, B., McCrae, N., & Grealish, A. (2020). A systematic review: The influence of social media on depression, anxiety and psychological distress in adolescents. Int J Adolesc Youth, 25(1), 79–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673843.2019.1590851

- Kumar, R. K., Aruna, G., Biradar, N., Reddy, K. S., Soubhagya, M., & Sushma, S. A. (2022). The prevalence of depression, anxiety, and stress among high school adolescent’s children in public and private schools in Rangareddy district Telangana state: A cross-sectional study. J Edu Health Promot, 11, 83. https://doi.org/10.4103/jehp.jehp_548_21

- Kumar, G., Chhabra, A., Dewan, V., & Yadav, T. P. Prevalência e impacto nas atividades diárias da dor musculoesquelética idiopática em crianças da Índia [Idiopathic musculoskeletal pain in Indian Children-prevalence and impact on daily routine]. Rev Bras Reumatol, 2015 Jul 18 S0482-5004(15). 00073-X. Portuguese. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rbr.2015.03.005

- Mandrekar, S., Chavhan, D., Shyam, A. K., & Sancheti, P. K. Effects of carrying school bags on cervical and shoulder posture in static and dynamic conditions in adolescent students. Int J Adolesc Med Health, 34(1), 2019 Oct 30. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijamh-2019-0073

- Marsh, A. B., DiPonio, L., Yamakawa, K., Khurana, S., & Haig, A. J. (2006). Changes in posture and perceived exertion in adolescents wearing backpacks with and without abdominal supports. Am J Phys Med Rehabil, 85(6), 509–515. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.phm.0000219149.14010.d0

- Mosaad, D. M., & Abdel-Aziem, A. A. (2015). Backpack carriage effect on head posture and ground reaction forces in school children. Work, 52(1),203–209. PMID: 26410235. https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-152043

- Mosaad, M. D., Nabawy, H. E., & El-Sayed, W. H. (2014). Influence of load carriage on electromyographic activities of upper fibers of trapezius in school students during walking. Med J Cairo Univ, 8(2), 61–65. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Influence-of-Load-Carriage-on-Electromyographic-of-Mosaad-Nabawy/088d110c29fc279faa6f979195128585d6a38f9b

- Neves, M. M., & Leite, J. M. (2016). Avaliação postural em crianças do ensino fundamental, postural assessment in elementary school children [article in Portuguese]. Rev bras ciênc saúde, 20(4), 285–292. https://doi.org/10.4034/RBCS.2016.20.04.04

- Penha, P. J., João, S. M., Casarotto, R. A., Amino, C. J., & Penteado, D. C. (2005). Postural assessment of girls between 7 and 10 years of age. Clinics, 60(1), 9–16. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1807-59322005000100004

- Rask, K., Astedt-Kurki, P., & Laippala, P. (2002). Adolescent subjective well-being and realized values. J Adv Nurs, 38(3), 254–263. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.2002.02175.x

- Sampaio, M. H., Oliveira, L. C., Pinto, F. J., Muniz, M. Z. A., Gomes, R. C. T. F., & Coelho, G. R. L. (2016). Postural changes and pain in the academic performance of elementary school students. Fisioterapia em Movimento, 29(2), 295–303. https://doi.org/10.1590/0103-5150.029.002.AO08

- Samuel, W. (2011). Biomechanical applications to joint structure and function. In L. Pamela & N. Cynthia (Eds.), Joint structure and function, a comprehensive analysis (5th) ed., pp. 16–17). Jaypee Brothers.

- Sankaran, S., John, J., Patra, S. S., Das, R. R., & Satapathy, A. K. Prevalence of musculoskeletal pain and its relation with weight of backpacks in school-going children in Eastern India. Front Pain Res (Lausanne), 2021 Aug 18 2. 684133. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpain.2021.684133

- Santos, C. I., Cunha, A. B., Braga, V. P., Saad, I. A. B., Ribeiro, M. Â. G. O., Conti, P. B. M., & Oberg, T. D. (2009). Occurrence of postural deviations in children of a school of Jaguariúna, São Paulo, Brazil. Revista Paulista de Pediatria, 27(1), 74–80. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0103-05822009000100012

- Sedrez, J. A., Rosa, M. I., Noll, M., Medeiros, F. D. S., & Candotti, C. T. (2015). Risk factors associated with structural postural changes in the spinal column of children and adolescents. Revista Paulista de Pediatria, 33(1), 72–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rpped.2014.11.012

- Szucs, K. A., & Brown, E. V. (2018). Rater reliability and construct validity of a mobile application for posture analysis. J Phys Ther Sci, 30(1), 31–36. https://doi.org/10.1589/jpts.30.31

- Wong, A. Y. L., Chan, T. P. M., Chau, A. W. M., Tung Cheung, H., Kwan, K. C. K., Lam, A. K. H., Wong, P. Y. C., & De Carvalho, D. (2019, January). Do different sitting postures affect spinal biomechanics of asymptomatic individuals? Gait Posture, 67, 230–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaitpost.2018.10.028