Abstract

The market share of small household appliances has grown tremendously in recent years. Varied innovation methods are applied in developing small household appliances, including Turkish Coffee Makers; however, Kansei Engineering has not yet been carried out in this field. This paper aims to conduct Kansei Engineering methodology on these machines to provide design inputs for industrial designers. The domain of the study is Turkish Coffee Makers with one pot and without a water tank, and the target is between 20–40 aged Turkish people. 382 participants attended the study, and 16 stimuli were utilised. The study methods are extracting Kansei words, selecting product properties, affinity diagram, SD Questionnaire, factor, descriptive, and PLS analyses. The results suggest that designers can generate Turkish Coffee Makers with Square with fillet as the top view, Trapezoid as the front view, C-shape cornered as the right view, and two colours as the main body colour; and design these products depending on the design factors of stylish, easy to use, joyful, trend follower, functional, desirable, youthful, dissimilar, and luxurious to succeed in the market. As a result, product designers might determine the product properties more efficiently via the findings of this study.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Along with the Covid-19 pandemic, the Small Household Appliances and Electronics Industry has grown. Turkish Coffee Makers are one of these devices whose market share has increased during the pandemic. The manufacturers of these novel machines are already employing various innovation methodologies to stay ahead of the competition. However, there was still a need to learn about the feelings and desires of consumers regarding these products. In this study, we applied Kansei Engineering methods in Turkish Coffee Makers with one pot and without a water tank. We tried to examine the connection between Turkish Coffee Maker consumers’ Kansei and the visual design properties (hedonic, aesthetic factors, form and colour properties) of these products. We found that the most effective product properties are “Square with fillet” in the top view, “Trapezoid” form in the front view, and “C-shape cornered” design in the right view, two coloured on the whole product.

1. Introduction

Since the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic, people have been retained in their homes and have spent more time at home (Donthu & Gustafsson, Citation2020), and the lockdown caused a significant increase in home cooking (Sarda et al., Citation2022). Moreover, along with this pandemic, the Small Household Appliances and Electronics Industry has grown (Gavlovskaya & Khakimov, Citation2022). Turkish Coffee Maker (TCM) is one of these appliances whose market share has risen during the pandemic (URL 1). Moreover, the market size of Turkish Coffee Makers has grown by an average of 30–40 per cent yearly over the last five years. This market, 61 million TL in 2013, reached 156 million TL in 2016; the market continued to grow in 2017 and reached 191 million TL with a 34 per cent growth compared to the same period in 2016. (CitationURL-2) In 2020, as of September, the coffee machine market reached 1.1 million units and 429 million TL (CitationURL-1).

As a new product category, TCM aimed to replace the traditional Turkish coffee preparing ritual, which consisted of a pot and stirring spoon. The rise of TCM products resulted in many competitors with their original designs. With the emergence of this new product category, industrial designers became responsible for convincing ordinary users to purchase a TCM to prepare their Turkish coffee by creating new product forms.

The rise in market share of TCMs can be related to some of their advantages: (1) it is easier to make Turkish coffee in TCM than in traditional coffee pots, (2) it saves time depending on its automatic system with an audible alert, and (3) the taste of the coffee produced with this machine is almost the same as the traditional coffee pots.

Considering the high consumption rates of traditional Turkish coffee, white goods manufacturer Arçelik invented and introduced the first TCM, as a new product, in 2004 and changed how this cultural beverage is consumed. Since 2004, many companies have followed this technology, and today there are more than 20 companies and over 100 TCMs in Turkey’s Small Household Appliances market. This rise in the number of manufacturers has increased the competition and the need for innovation.

Many innovation methods have already been applied to small household appliances, such as the use of bioplastic (Cecchini, Citation2017), the use of sustainable materials (Ceschin and Gaziulusoy (Citation2016), technology-push and market-pull innovation (Choi, Citation2018) and customer-driven innovation (Desouza et al., Citation2008). However, we noticed that the Japanese innovation method Kansei Engineering (Nagamachi, Citation1995; Schütte, Citation2002) has not yet been applied to TCM as it is a new and local product with a strong cultural background.

This study aims to apply Kansei Engineering techniques in TCMs and provide design inputs and hints for TCMs’ industrial design processes. The study’s sub-goals are to explore (1) consumer emotions, high-level Kansei words and design factors regarding TCMs, (2) affective dimensions of TCMs, (3) relationships between product features and consumer emotions, (4) the most desired product features, and (5) to create optimum designs.

This study is limited to Turkish consumers aged 20–40 and 16 Turkish Coffee Maker products. We used 110 Kansei words in the first study and 20 Kansei words in the second study. Moreover, due to the difficulty of evaluating the high number of product attributes, we implemented KE for four items and 29 categories.

The design values and product features that this study focuses on are other limitations. A product consists of functional, aesthetics and symbolic values (Benaissa & Kobayashi, Citation2022; Brunner et al., Citation2016; Candi et al., Citation2017; Creusen & Schoormans, Citation2005; Eisenman, Citation2013; Homburg et al., Citation2015; Noble & Kumar, Citation2010; Rafaeli & Vilnai-Yavetz, Citation2004). Although product designs’ functional and symbolic values are effective on consumers’ product purchasing (Baxter, Citation2018; Brunner et al., Citation2016; Candi et al., Citation2017; Crilly et al., Citation2004; Homburg et al., Citation2015; Norman, Citation2004; Rafaeli & Vilnai-Yavetz, Citation2004), this study concentrated on solely the aesthetic design factors (values). The main reasons for working on aesthetics are that the research was conducted online, and our planned future studies on this research are related to aesthetic values. In addition, although product aesthetic dimensions are mentioned in the literature as form, colour, material and texture (Zuo, Citation2010; Tilburg et al., Citation2015), we examined only the form-colour properties of TCMs due to time constraints. On the other hand, considering a specific product, the number of product alternatives on the market has significantly increased over the decades. This fact has resulted the widespread use of online shopping, which is mostly based on a visual evaluation and selection process, in other words form and colour qualities, compared to in-store shopping processes.

The remainder of the article is organised as follows. Chapter 2 consists of a literature review; Chapter 3 presents methodology; Chapter 4 shows results; Chapter 5 includes a discussion and implications; and chapter 6 contains a conclusion.

2. Literature review

2.1. Design factors affecting consumers’ attitudes and responses

Batra and Ahtola (Citation1991) stated that “consumers purchase goods and services and perform consumption behaviours for two basic reasons: (1) consummatory affective (hedonic) gratification (from sensory attributes), and (2) instrumental, utilitarian reasons”. According to Voss et al. (Citation2003), hedonic factors arise from the feelings associated with using products, and utilitarian factors arise from the functions performed by the products. On the one hand, several researchers have defined the design factors that affect consumers’ attitudes towards products as hedonic and utilitarian (pragmatic) factors (Babin et al., Citation1994; Batra & Ahtola, Citation1991; Chitturi et al., Citation2008; Dhar & Wertenbroch, Citation2000; Voss et al., Citation2003). On the other hand, numerous researchers have defined the design factors that affect consumers’ response to products as aesthetics, utility and symbolic concepts (Benaissa & Kobayashi, Citation2022; Brunner et al., Citation2016; Candi et al., Citation2017; Creusen & Schoormans, Citation2005; Eisenman, Citation2013; Homburg et al., Citation2015; Noble & Kumar, Citation2010; Rafaeli & Vilnai-Yavetz, Citation2004).

Holbrook (Citation1980) defined the consumer aesthetic as “the study of the buyer’s cognitive, affective, and behavioural responses to media, entertainment, and the arts” and mentioned the aesthetic value as the diffuse feeling of pleasure while seeing the product without using it. Consistent with Holbrook (Citation1980), Kumar and Noble (Citation2016) described the aesthetic value of product design as the consumers’ perception of attractiveness and pleasure stemming from its looks.

On the other hand, according to Kumar and Noble (Citation2016), functional value in a product’s design is the way it helps satisfy the practical or utilitarian demands of the consumer. Furthermore, Crilly et al. (Citation2004) stated that the functional values include “practical qualities such as function, performance, efficiency, and ergonomics”. Finally, according to Crilly et al. (Citation2004), symbolic value is the consumers’ perception of what a product tells about its owner or user and the social and personal meaning that this product design includes.

2.2. Product aesthetics and utility

Hedonic benefits are connected to products’ aesthetic, experiential, and enjoyment-related benefits (Batra & Ahtola, Citation1991; Strahilevitz & Myers, Citation1998; Chitturi et al., Citation2007; Dhar & Wertenbroch, Citation2000; Sundar et al., Citation2020) emphasized how product aesthetics is significant on consumers’ purchase decisions via packaging design sample. Holbrook and Zirlin (Citation1985) defined consumers’ aesthetic response as a “deeply felt experience that is enjoyed purely for its own sake without regard for other more practical consideration”. According to Hekkert and Leder (Citation2008), people experience aesthetics through their five senses, and visual aesthetics is one of them. K. L. Hsiao and Chen (Citation2018) explained design aesthetics as the “beauty of a product’s appearance”. Consistent with K. L. Hsiao and Chen (Citation2018), P. Lu and Hsiao (Citation2022) stated that consumers generally perceive the visual aesthetic of a physical product according to how it looks.

K. L. Hsiao and Chen (Citation2018) conducted an experimental study on smartwatches and documented that design aesthetics positively affect user attitudes. In addition, Toufani et al. (Citation2017) examined smartphones and found that aesthetics positively influence consumers’ purchase intentions. Li and Li (Citation2022) also revealed that design aesthetics favourably affect consumers’ purchase intention through perceived value. From the point of view of New Product Development (NPD) field some research argue that product aesthetics is an part essential part of the design of a new product (Tang et al., Citation2013), as it positively affects purchase intention (Toufani et al., 2007; Li & Li, Citation2022). Also, there exist some research comparing product aesthetics and utilitarian properties. According to Chitturi et al. (Citation2008), products that meet hedonistic expectations arouse delight, whereas products that meet utilitarian expectations arouse satisfaction. Previous studies have examined how much importance customers place on hedonic and utility factors in their purchasing decisions (Chitturi, Citation2009). Kivetz and Simonson (Citation2002) reported that consumers give more weight to the utilitarian dimension than the hedonic dimension unless they think they have “earned the right to indulge”. Consistent with Kivetz and Simonson (Citation2002), Chitturi et al. (Citation2007) documented that when options in a choice set satisfy both utilitarian and hedonic needs, consumers give more weight to the hedonic attribute.

In this paper, we assumed that all of the TCM stimuli in this study satisfy utility needs. Thus, we concentrated on TCMs’ hedonic and visual aesthetic factors with the help of an online survey.

2.3. Design principles affect aesthetic appreciation

Reber et al. (Citation2004) defined aesthetic pleasure (appreciation) as a “pleasurable subjective experience that is directed toward an object and not mediated by intervening reasoning”. Because of the positive correlation between product aesthetics and purchase intention, consumers’ aesthetic appreciation is essential for companies (Li & Li, Citation2022). According to Berlyne’s (Citation1974) theory, people have similar emotional processes while valuing aesthetics (Benaissa & Kobayashi, Citation2022). After the emergence of this theory (Berlyne, Citation1974), several researchers focused on this topic. Benaissa and Kobayashi (Citation2022) stated that some design principles influence aesthetic appreciation. In addition, Saurwein (2017) mentioned that common principles of aesthetic appreciation are identical to human nature. Below, we have presented some of these principles and Gestalt laws relevant to our experimental study.

The design principles that may be included in the products that are the subject of this study are symmetry (Bauerly & Liu, Citation2008; Corradi et al., Citation2019; Hekkert, Citation1995; Veryzer Jr, Citation1993), complexity (al-Rifaie et al., Citation2017; Corradi et al., Citation2019; Güçlütürk et al., Citation2016; Van Geert & Wagemans, Citation2021), curvatures (Bar & Neta, Citation2006; Bertamini et al., Citation2016; Corradi et al., Citation2019; Gómez-Puerto et al., Citation2016, Citation2018), balance (Corradi et al., Citation2019; Fillinger, Citation2020), unity (Post et al., Citation2016; Veryzer Jr & Hutchinson, Citation1998), proportion (Baxter, Citation2018: Hannah, Citation2002), continuance (Baxter, 218; Elder & Goldberg, Citation2002), order (Van Geert & Wagemans, Citation2021), similarity (Baxter, Citation2018; Chou, Citation2011; Kubovy & Van Den Berg, Citation2008). Definitions of these principles are as follows+;

Balance is defined as “the dynamic state in which the forces constituting a visual configuration compensating for one another” (Arnheim, Citation1983) for a pictorial composition

Complexity refers to “a whole plethora of different stimuli” (Van Geert & Wagemans, Citation2021)

Good Continuance refers to “the tendency of things to be perceived as a group if they are visually co-linear or nearly co-linear.” (Pirzadeh, Citation2012)

Curvature means “the condition or extent of being curved” (CitationURL-3)

Proportion The overall proportion is defined as “the character or overall configuration of a group of forms.” (Hannah, Citation2002)

Similarity: “Based on Gestalt laws of similarity, elements/objects tend to be perceived as a whole in cognition if they share the similar appearance of visual features (Yan et al., Citation2018)

Symmetry is “is the exact correspondence of shape on opposite sides of a dividing line or plane or about a center or axis” (Arnheim, Citation1988)

Unity is “the perception of a whole, and of an order and coherence between properties and elements” (Berlyne, Citation1973)

2.4. Cross-cultural design

Cross-cultural design means designing for different cultures, languages and economic standings and ensuring usability and user experience across cultural boundaries (Aykin, Citation2005; Walsh & Nurkka, Citation2012). Globalization has necessitated cross-cultural design, which requires creating systems or products with properties recognized generally by all cultural groups (Stefanou, Citation2014). According to Kaynak and Herbig (Citation2014), global business can be risky if designers do not leave behind an ethnocentric viewpoint. The authors pointed out that designers should consider the new markets’ language, preferences, way of life, and cultural connections. (Kaynak & Herbig, Citation2014).

Zhou et al. (Citation2022) explained some cultural and visual elements used in product design: colour, material, pattern and form. Jacobs et al. (Citation1991) conducted an experimental study and documented the meanings of colours for various cultures. For instance, in China, more than 50% of the respondents perceived the feeling of red as happy, while in Korea, Japan, and the USA, more than 50% perceived the feeling of red as love. Furthermore, according to Zhang’s (Citation2014) cross-cultural design research on children’s responses to packaging form design, both US and China preferred curved packaging shapes. On the other hand, it was also revealed that Chinese children tended to prefer figurative forms in packaging design more than their American peers (Zhang, Citation2014). Ljungberg and Edwards (Citation2003) explained the importance of cross-cultural values of materials in product design with examples. For instance, they stated that sinks in Turkey are usually made of stone (marble), while in Sweden, they are traditionally made of stainless steel (Ljungberg & Edwards, Citation2003). In addition, the authors stated that wood is a material associated with luxury in Mediterranean countries rather than Scandinavian countries due to its limited availability and high cost (Ljungberg & Edwards, Citation2003).

In the cross-cultural design approach, designers can use existing cultural theories, user-centred design in the specific culture and countries, and usability studies and testing with local people (Aykin, Citation2005; Walsh & Nurkka, Citation2012; Walsh & Vainio, Citation2011). As an alternative, Zhou et al. (Citation2022) proposed a deep learning methodology to facilitate cross-cultural design processes.

2.5. Kansei engineering

2.5.1. Definitions, application areas and selected domain

Kansei Engineering (KE) is an ergonomics-based and customer-oriented (Nagamachi, Citation2002), computer-aided (Bouchard et al., Citation2003), and emotion-focused (Schütte, Citation2005) innovation methodology. It is developed in the early 1970s at Hiroshima University, Japan (Nagamachi, Citation2002). Nagamachi (Citation1995) stated that Kansei Engineering was created as a consumer-oriented technology for New Product Development processes and defined it as “translating technology of a consumer’s feeling and image for a product into design elements”. Schütte et al. (Citation2004) explained that Kansei Engineering is a tool that converts client emotions into concrete product features and provides guidance for future product design. Moreover, Nagamachi et al. (Citation2006) explained the goal of Kansei engineering as creating a new product by transferring customers’ psychological demands and feelings (Kansei) about it into design specifications.

According to Schütte et al. (Citation2004), Kansei Engineering serves primarily as a catalyst for the systematic development of novel and innovative designs; however, it can also be utilised to advance current products and designs. Numerous success stories contribute to Kansei Engineering’s reputation among Japanese corporations such as Mazda, Sharp, and Wacoal (Schütte et al., Citation2004). These success stories serve as some of the study’s motivation.

Today KE methodology is used in a variety of fields and for a wide range of products (Ishihara & Nagamachi, Citation2008), such as; transportation design (Chang & Chen, Citation2016; Chiu & Lin, Citation2018; Smith & Fu, Citation2011), web interfaces (Y. C. Lin et al., Citation2013), architecture (Llinares & Page, Citation2011), interior spaces (Castilla et al., Citation2017), fashion (Shimizu et al., Citation2004), jewellery (J Lin et al., Citation2019), packaging (Maleki et al., Citation2020), food (Schütte, Citation2013), services (Y. H. Hsiao et al., Citation2017), eco-design (Rasamoelina et al., Citation2013). Mobile phones (Oztekin et al., Citation2013), furniture (Hsu et al., Citation2017), power tools (Grimsæth, Citation2005), glassware (Kittidecha & Yamada, Citation2018), sunglasses (Chuan et al., Citation2013), ceramic souvenirs (Tama et al., Citation2015) are examples of KE research focusing on product design.

Small household appliances are another product design field in which KE is applied. For instance, filter coffee machines (S. W. Hsiao et al., Citation2010), blenders (Kang, Citation2020), kettles (K. A. Hsiao & Chen, Citation2006), and toasters (Y. Lu & Guo, Citation2021) are samples of KE-applied products and research. Inspired by the literature stated above, we chose Turkish Coffee Makers as the research domain. There are numerous grounds for this choice, including the fact that it is a new, radical innovation with high consumption rates due to its traditional aspects. The appearance of a small appliance can be an essential factor in consumers’ purchasing decisions (Creusen & Schoormans, Citation2005); therefore, in this KE case study, we focused on the shape and colour characteristics of TCMs.

2.5.2. Selected property spaces, form and colour

The appearance of a product, in terms of aesthetics, symbolism, and functionality, directly influences consumer choices (Creusen & Schoormans, Citation2005). The form of a product is one of the essential features that attract the consumer’s attention at first glance. Studies in Kansei Engineering frequently focus on the form properties of product design. These studies use three approaches: a morphological schema with images, a text table, or both. For example, filter coffee makers (S. W. Hsiao et al., Citation2010), disposable razors (Razza & Paschoarelli, Citation2015), chairs (S. W. Hsiao & Huang, Citation2002), electric bicycles (Wang & Zhou, Citation2020), bikes (Chiu & Lin, Citation2018), mobile phones (Yang, Citation2011), soccer shoes (Lee & Han, Citation2022), running shoes (Shieh & Yeh, Citation2013) use morphological analysis with abstracted or photorealistic images. On the other hand, the KE study on toothbrushes (Shieh & Yeh, Citation2016) uses text to present form features.

Colour is another significant feature that affects people’s purchasing decisions (Grossman & Wisenblit, Citation1999). Ma et al. (Citation2007) stated that various colour combinations could achieve a trendier look. However, since there are many colour alternatives, companies have to narrow these options and choose some colour combinations in their product ranges. Kansei Engineering is valuable for identifying these colour clusters in NPD processes. An example of KE research focusing on colour is a study on chocolates (Schütte, Citation2013) evaluating two-colour chocolate packages, red and gold. Another study (Tama et al., Citation2015) applied KE to ceramic souvenirs and evaluated the colour properties of single-colour, multi-colour, blocked/solid colour, and colour grading.

3. Materials and methods

The methodology utilised in this study is adapted from Schütte’s KE model (Schütte, Citation2002), highly cited in KE literature. Furthermore, consistent with the model of Nagamachi and Lokman (Citation2016), we reduced the number of Kansei words at the beginning of the study. The stages of the study are explained below:

3.1. Stage 1: Choosing the domain

At the beginning of the study, the product domain was determined. Schütte and Eklund (Citation2005) gathered information from market research, expert interviews, focus groups and stakeholders to choose the domain for their KE study. Consistent with them, we carried out market research and expert designer interviews. Additionally, informal visits to retailers, along with observations at these retailers, were conducted to support and fine-tune our decision.

3.2. Stage 2: spanning the semantic space

After choosing the domain, we extracted low-level Kansei Words by following the literature (Nagamachi & Lokman, Citation2016; Schütte, Citation2002). In addition, we examined customer reviews from e-commerce sites such as amazon.com, trendyol.com, gittigidiyor.com, n11.com, and hepsiburada.com. Resources such as designers’ interviews, industry news and related Kansei engineering articles (Schütte, Citation2013; Schütte & Eklund, Citation2005; S. W. Hsiao et al., Citation2010) are also utilised in spanning the semantic space. Furthermore, unlike previous KE research, we reviewed award-winning product descriptions and jury statements from the Red Dot Design Awards and IF Design Awards to extract other Kansei Words (Goken and Alppay, Citation2021).

Text mining applications have become increasingly popular in Kansei Engineering research over the past few years. (Chen et al., Citation2019; Chiu & Lin, Citation2018; Y. H. Hsiao et al., Citation2017; Kim et al., Citation2019; Lai et al., Citation2022; W. M. Wang et al., Citation2018). Consistent with these studies, we used text mining techniques besides the abovementioned methods to expand the semantic space. First, we extracted text data from customer reviews on the Trendyol e-commerce site through WebHarvy, a web scraping software; then, we sorted them considering the repetition frequency and added them to the Kansei words list. At the end of the study, we applied the affinity diagram (KJ) method (Lokman & Kamaruddin, Citation2010) to reduce the number of Kansei Words without losing critical information. In this study, we grouped the words with similar meanings and gave representative names for each group (Goken and Alppay, Citation2021), as shown in Appendix C. In addition, we utilised the most frequently repeated words in the text-mining study as representative words because we estimated they were high-level Kansei words.

After spanning the semantic space, we conducted Osgood’s semantic differential method on a 7-point Likert scale to measure the customers’ feelings about these products via SD Questionnaire 1. Each participant evaluated the images of ten well-known Turkish Coffee Makers and five Kansei word pairs. 210 participants responded to 21 questionnaires related to 105 Kansei word pairs via social media. The demographic data of the participants in SD Questionnaire 1 is shown in Table .

Table 1. Profile of the participants in SD questionnaire 1

Factor analysis is a multivariate statistical analysis method to reduce numerous variables into fewer numbers of factors. In order to diminish the number of Kansei words and extract the main factors, we performed factor analysis with IBM SPSS V.28 software after conducting the Affinity Diagram (KJ) method. Next, following Nagamachi and Lokman (Citation2016), we chose high-level Kansei Words among the highest-scoring Kansei words in the factor columns and the most necessary words with different meanings.

Nagamachi and Lokman (Citation2016) stated that even without applying KE, by examining the factorial structure and developing a novel design without skipping these factors, particularly the ones with the highest value, a new product can be manufactured successfully. As the authors explained, it is possible to create the market appeal of TCMs by designing these products depending on these factors (Table ). In order to utilise these factors efficiently, we assigned each factor a name representing all Kansei words with high loading values, indicated in Table .

Table 2. Profile of the participants in SD questionnaire 2

Table 3. Selected stimuli

Table 4. Result of factor analysis 1 with rotation varimax

3.3. Stage 3: spanning the property space

After selecting high-level Kansei Words, we determined TCM’s main body’s form and colour as product features. First, we created a morphological chart (Razza & Paschoarelli, Citation2015; S. W. Hsiao et al., Citation2010) by dividing the main body into parts, such as the top, front, and right (orthographic views). Next, in order to be utilised in the later phases of the research, we visualised these views’ simplified images (Table ), and then grouped, named them (these shapes), and created a product feature matrix (Table ) consistent with the KE studies (Shieh & Yeh, Citation2013; Yang, Citation2011). We used the 16 stimuli photographs to extract these drawings.

Table 5. Selected high-level Kansei words

Table 6. Top(A), front(b), and right (c) views of TCM main bodies

Table 7. Items and categories of form and color properties

Secondly, we focused on the colour characteristics of the main body. There are many colour options for TCMs; however, we only used the stimuli with black, grey or anthracite, rose, and black with chrome and copper stripes. On the other hand, we grouped and defined the main body colour properties similarly to Tama et al.’s (Citation2015) study, including five categories; single-colour, single-colour with a stripe, single-colour with a stripe and coloured button, two-colour, and two-colour with a stripe. Afterwards, we added colour items and categories to the product feature matrix (Table ). This matrix table will be utilised in the other parts of the research. The 16 stimuli (Table ) have a significant role in determining the space of form and colour properties of TCMs; therefore, we selected TCMs that differed from one another concerning their form and colour attributes.

3.4. Stage 4: synthesise the semantic and property spaces

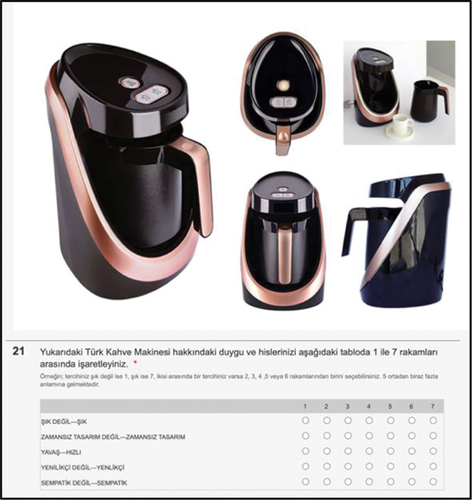

After spanning Kansei words and TCM properties, we conducted SD Questionnaire 2 using an online survey website. This survey showcased 16 stimuli with five images for each and five hedonic Kansei word pairs on 7 Likert scales. In addition, 172 volunteers participated in this study. Demographic data of the experiment are shown in Table . In this questionnaire, we used the 16 products selected among well-known brands in Turkey (Table ). In Appendix B, we also showed a sample question including S14ʹs perspective, top, front, and right views, and a composition of the main body, its coffee pot, and a coffee cup.

We carried out two primary analyses in this stage: descriptive and PLS. First, we conducted a descriptive analysis in IBM SPSS V.28 to show the mean scores for each stimulus. Consistent with Razza and Paschoarelli (Citation2015) and Chenet al. (Citation2015), we presented descriptive analysis results and the mean scores (affective dimensions) of 16 TCM stimuli in Tables . Furthermore, we highlighted the highest and lowest scores in bold.

Table 8. Affective dimensions of the TCM (K1-K10)

Table 9. Affective dimensions of the TCM (K11-K20)

In the synthesis stage, we carried out PLS analysis in Microsoft Excel XLSTAT, considering the models of Schütte (Citation2002) and Nagamachi and Lokman (Citation2016) to connect semantic space and space of properties. Partial Least Squares Regression is an analysis method used to find essential relations between two matrices. Although QT1 is the most popular method in Kansei Engineering studies, we conducted a PLS analysis. The main reason for this preference is that PLS can measure numerous valuables with a small sample size (Matsubara et al., Citation2011). Furthermore, some researchers such as Chen, Hsu et al. (Citation2015); Shieh and Yeh (Citation2013); Y. H. Hsiao et al. (Citation2017) performed PLS analysis in their Kansei Engineering research; in particular, Y. H. Hsiao et al. (Citation2017) inspired us to build a PLS model for this study.

In PLS analysis, we utilised two primary data: the mean scores of Kansei words and the dummy variables of product properties of 16 TCM stimuli. The descriptive analysis had already revealed the mean scores of Kansei words. Furthermore, consistent with the literature (Abdi and Greenacre, Citation2020; Y. H. Hsiao et al., Citation2017), we created dummy variables of TCM properties for 16 stimuli and indicated them in Appendix A. In this matrix table, 0 represents that the TCM stimulus did not adopt the categories, while 1 represents the adoption of the categories. We presented this table of colour items and categories as an example and generated a similar dummy table for form properties.

3.5. Stage 5: test of validity and factor analysis 2

In order to identify and interpret critical factors (Nagamachi et al., Citation2008; Mamaghani et al., Citation2014), we conducted factor analysis 2. Next, we tested the study’s validity and used Cronbach’s alpha for the reliability analysis (Lokman & Nagamachi, Citation2009; Chen et al., Citation2015; Y. H. Hsiao et al., Citation2017). For these analyses, we utilised IBM SPSS V.28.

3.6. Stage 6: building the models

After the validation study, we built two PLS models, (1) the form model and (2) the colour model, between Kansei words and the product properties of Turkish Coffee Makers. These models will provide some hints for designers in TCMs’ NPD processes.

3.7. Creating optimum designs

Optimum designs are inspiring visuals and data for designers on how to use KE results. For instance, Kansei Engineering studies, such as Guo et al. (Citation2014) and S. W. Hsiao et al. (Citation2010), produced and offered optimum designs depending on their findings. Moreover, we presented the optimum designs by presenting orthographic views concerning form features and product samples related to colour features in Tables . The TCM optimum designs created depending on our findings can guide designers, marketing experts, managers, and decision-makers in R & Ds and the small appliances household sector.

Table 10. PLS model l, form property and Kansei words (standardised coefficients)

Table 11. PLS Model 2, main body colour-Kansei words (standardised coefficients)

Table 12. Categories with highest mean values related to Kansei words

Table 13. Optimum Design 1

Table 14. Optimum design 2

4. Results

4.1. Results of choosing the domain

We chose the domain as the Turkish Coffee Maker with one pot and without a water tank. We target Turkish consumers between the ages of 20–40. In addition, we selected the participants of the SD Questionnaires among people consuming coffee regularly or occasionally.

4.2. Results of spanning semantic space

In the spanning semantic space stage, we first attempted to discover the most powerful Kansei words, customers’ emotions, on Turkish Coffee Makers, which addresses the study’s first sub-goal. Initially, we extracted 384 Kansei words from e-commerce sites, industry news, academic journals, jury comments in design competitions, and text-mining studies based on 1600 customer reviews. Following this word extraction, we reduced the number of Kansei Words from 384 to 105 via the affinity diagram (KJ) method (Goken and Alppay, Citation2021), which will be utilised in the following stages of the studies. These 105 Kansei words are the most representative words that define the target customers’ feelings toward Turkish Coffee Makers. Finally, we decreased the number of Kansei words due to the difficulty of conducting the study with the high number of words (384). Appendix C shows these 105 representative words chosen via the affinity diagram method.

However, because the number of Kansei words (105) was higher for a KE methodology application, we reduced the number to 20 by performing SD Questionnaire 1 and factor analysis 1. Namely, we performed the first experiment (SD1) and factor analysis to select the high-level Kansei words utilised in the main experiment (SD2).

Table shows the results of factor analysis with rotation varimax. Each Kansei word has a factor loading greater than 0.6. This table also reveals eight factors with eigenvalues higher than 1, describing 48.19% of the total variance. The first factor, “ stylish,” represents 12.261% of the data. This factor has the most significant impact on the market success of these machines. The other factors represent 6.876%, 6.229%, 5.874%, 4.957%, 4.356%, 3.985%, and 3.653% of all data. The total variance (48.19%) is relatively low because we eliminated the Kansei words associated with the taste of the coffee produced in TCMs at the beginning of the study. Furthermore, we eliminated the factors with low impacts as being insignificant, consistent with Mamaghani et al. (Citation2014).

Next, we labelled all the factors of the chosen Turkish Coffee Maker domain as “stylish, easy to use, joyful, trend follower, youthful, functional, dissimilar and luxurious”. After obtaining the results of factor analysis 1, we selected the highest-rated 20 hedonic Kansei words (Table ) as high-level Kansei words out of every factor. Moreover, we eliminated the pragmatic variables in Table at this stage because the study’s main focus is the appearance of TCMs instead of usage, and it would be challenging to evaluate pragmatic words without touching and using them.

4.3. Results of spanning property space

In this stage, we determined the form and colour properties of TCMs to utilise them in the synthesis stage, and first, we extracted form features. Next, we generated the simplified orthographic drawings (Table ) of each 16 products based on photographs shown in Table . Next, we grouped and named these data in Table . Furthermore, we obtained five colour features based on 16 stimuli and grouped and defined these features in Table . Finally, we clustered all categories and presented them in the right part of Table .

Table includes all items and categories of selected properties. However, it would be better to define some design features in detail to make them more comprehensible. These definitions are; C shape with fillet (Right): Resembles C shape and has fillets in the interior part in the right view; C shape cornered (Right): Looks like C shape and has one or zero fillets in the interior part in the right view; C shape minimum (Right): C form has the narrow interior part, the coffee pot is seen less in the right view, Z shape (Right): The outline of the right view resembles Z shape. Z shape reverse (Right): The outline of the right view turned 180 degrees resembles a Z shape. Closed (Right): The right view is convex; no interior part is seen.

4.4. Results of synthesis of semantic and property spaces

4.4.1. Results of descriptive analysis (affective dimensions)

We performed a descriptive analysis in IBM SPSS V.28 to obtain the mean values of each stimulus. The results (Table , Table , Figure , Figure ) illustrate the participants’ Kansei perceptions depending on the SD Questionnaire 2 responses with the 7-point Likert scale. Furthermore, Tables address sub-goal two related to learning the affective dimensions of the selected TCM stimuli.

The Kansei words and correlating mean values of 16 stimuli are presented in Tables . Moreover, these tables show the highest scores in bold and the lowest scores underlined and bold. According to the findings, the mean scores of dissimilar, showy corresponding the product S14 have the highest values (5.35), and the mean scores of artistic relating the product S6 have the lowest value (2.40). Furthermore, S1 has received a highly positive impression for many semantic axes, and S15 has received the lowest evaluation for many semantic axes in this study.

In addition, Figure shows the mean value scores of the stimuli. The results indicate that S14 has the highest mean value score; S5 has the lowest mean value score. A pattern identified is that the products S12 and S14 have different forms, shapes, and sizes from other stimuli and have the highest mean scores. On the other hand, S6 and S15 have received minimum mean value scores according to Figure , although they consist of steel coffee pots. In the market, the TCMs with steel pots have higher prices than those with plastic pots.

The mean scores of the Kansei Words are indicated in Figure . The Kansei word striking has the highest mean score (4,46), and the artistic has the lowest (3,31). Therefore, most participants perceived TCM stimuli as more striking but less artistic. On the other hand, the participants found TCM products contemporary (4,32), speedy (4,25) and trend follower (4,15) with the highest mean value scores, respectively, besides striking.

4.4.2. Results of PLS Analysis 1: PLS Form Model 1

This stage aimed to examine the correlation between TCM form properties and Kansei words; and addresses sub-goal 3 of the study. First, following Abdi and Greenacre (Citation2020), we chose two words with the most significant loadings from each factor for the effectiveness of the research process. These words are creative (.915), pleasurable (.901), stylish (.894), timeless (.819), well-considered (.832), elegant (.828), luxurious (.850), and contemporary (.826). Second, we identified Kansei words as dependent and TCM properties dummy as independent variables for the PLS analysis in Microsoft Excel XLSTAT. PLS model 1 contains three items and 24 categories. The results are indicated in Table , and we presented the highest scores in bold. According to the results, it is observed that the categories with positive score value significantly and positively affect the consumers’ feelings.

In the top view, five categories have positive score values: Square with fillet, Amorphous, Semicircle-rectangle (vertical) compound, Rectangle with fillet and Circle. These features affect the users’ emotions positively; however, Square with fillet has the most significant effect compared to the others. In the front view, four categories have positive score values: Trapezoid, Amorphous, Other geometry and Rectangle with fillet, respectively, and Trapezoid has the highest value. In the right view, three categories have positive score values: C-shape cornered, Z-shape reverse, and Z-shape in order. Furthermore, C-shape cornered has the most substantial impact on consumers’ emotions.

4.4.3. Results of PLS Analysis 2: PLS Color Model 2

Following PLS study 1, we conducted another PLS analysis to examine the relationship between the TCM main body colours and Kansei words. This analysis’s findings also address sub-goal 3 of the study. PLS model 2 consists of one item and five categories. Moreover, the results of the PLS analysis and the highest scores in bold are indicated in Table . In addition, the 8 Kansei Words with high factor loadings were evaluated in this stage, consistent with PLS study 1.

The result of PLS 2 (Table ) shows that the main body colour properties, which are “two colours and one colour”, positively impact consumers’ feelings except for luxurious. It means that the main body with two colours has the most significant influence on the participants. Furthermore, when we examined the one-coloured TCM stimuli, we encountered that these products’ coffee pots have a different colour from the main body colour. Namely, it can be deduced that consumers desire TCM whole product with two colours.

Furthermore, the consumers found the TCM products without stripes more “creative, pleasurable, stylish, timeless, well-considered, elegant and contemporary”. On the other hand, users found the TCM products with “one-colour with stripe and coloured button, two-colour with stripe and one-colour with stripe” more “luxurious”, respectively. That means users perceive TCM products with stripes as more “luxurious”; however, less “creative, pleasurable, stylish, timeless, well-considered, elegant and contemporary”. Moreover, “one colour with a stripe and a coloured button” as the main body colour has the strongest impression on users concerning the luxurious perception.

4.5. Optimum designs

This stage of the study addresses sub-goals 4 and 5. Initially, the first three high-impact product properties on consumers’ Kansei depending on the PLS models, are shown in Table . Moreover, this table indicates the results for eight Kansei words; “creative, pleasurable, stylish, timeless, well-considered, elegant, luxurious and contemporary”, except for the relationship between luxurious and colour properties. Table also presents the categories with high mean values.

As the top view, we displayed the three categories with the highest mean values: “Square with fillet, Amorphous, and Semicircle-rectangle (vertical) compound”. Similarly, as the front view, we sequentially showed the three high-valued categories: “Trapezoid, Amorphous, and Other geometry”. In the right view, we indicated three categories having a substantial impact “C-shape cornered, Z-shape reverse, and Z-shape”. As for main body colours, only two categories have positive mean values: “two colours and one colour, and the two colours” has the highest mean values.

Tables shows the optimum designs related to the high-level Kansei Words. For instance, designers can evoke customers’ feelings of “creative, pleasurable, stylish, timeless, well-considered, elegant and contemporary” by generating optimum design based on the results of this study; such as utilising the “Square with fillet (top), a Trapezoid (front) C-shape cornered (right) and two colours (colour)” (Table ) features as TCM main body properties. In addition, utilising “Amorphous (top), Amorphous (front), and Z shape reverse (right)” (Table ) attributes could be a second optimum design depending on our findings.

4.6. Results of factor analysis 2 and validity

This study utilised factor analysis to explain the primary consumers’ Kansei factors on TCMs. Table shows four hedonic factors consisting of 20 high-level Kansei words. We had already eliminated the pragmatic factors after conducting the SD 1 questionnaire. Furthermore, Table also indicates the items with a factor loading greater than 0.65. For instance, “creative” has the highest factor loading (0.915).

Table 15. Results of factor analysis 2

According to the results, four hedonic factors can explain 68.809 % of the TCM Kansei dimensions based on their cumulative contribution to Factor Analysis (Table ). Factor 1 contributes 20.900 % and is the most dominant factor. The second, third and fourth factors describe 18.448%, 15.387%, and 14.074% of the data.

The first factor consists of “creative, pleasurable, energetic, artistic, and trend follower”. This Kansei space could be represented as “creative”. In addition, the second factor includes “stylish, timeless, sympathetic, innovative and speedy”, and this Kansei space could be interpreted as “stylish”. Moreover, the third factor comprises “well-considered, elegant, showy, dissimilar and young”, and this factor could be named “dissimilar”. The fourth factor involves “luxurious, contemporary, beautiful, striking, and joyful”. This factor could be described as “contemporary”.

In addition to factor analysis, Cronbach’s alpha was calculated to test the reliability. The results of the reliability analysis display that Cronbach’s alpha value is .821, greater than .70, indicating high reliability (Nunnally, Citation1978). To summarise, the results of this analysis verify that TCM consumers’ Kansei responses in SD Questionnaire 2 are reliable.

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical implications

Our findings make two significant theoretical contributions. First, they contribute to the literature by revealing the design factors of Turkish Coffee Makers. Although the KE literature on small household appliances (K. A. Hsiao & Chen, Citation2006; Kang, Citation2020; Y. Lu & Guo, Citation2021; S. W. Hsiao et al., Citation2010) offered similar design factors to our results, they also indicated different factors from ours and vice versa. The main reason is that their studies’ domains are similar but not identical to ours. The other reason is that these studies focused on global products, such as blenders and toasters and are widely used worldwide; however, our focus TCMs are local items used in Turkey. Furthermore, we have not yet encountered any KE study on TCMs in the literature.

Analysis results indicate four TCM design factors and 20 high-level Kansei words mentioned in Section 4 and Table . The common Kansei words between our study and KE investigation on kettles (K. A. Hsiao & Chen, Citation2006) are “innovative, contemporary, young, and elegant”; KE research on filter coffee machines (S. W. Hsiao et al., Citation2010) are “creative and elegant”; KE study concerning blender (Kang, Citation2020) is “elegant”, and KE toaster research (Y. Lu & Guo, Citation2021) is “stylish”. Moreover, “excited, gorgeous” (K. A. Hsiao & Chen, Citation2006), “graceful” (S. W. Hsiao et al., Citation2010), “original, aesthetic satisfaction” (Kang, Citation2020), and “exquisite” (Y. Lu & Guo, Citation2021) are similar words used in literature with ours. As a result, our findings and the literature above identified a pattern: small household appliances could be “elegant, original and aesthetically pleasant” to succeed in the market. On the other hand, there are some other words, such as “creative, pleasurable, stylish, innovative, young, beautiful, and joyful”, have partial similarities with the literature (K. A. Hsiao & Chen, Citation2006; Kang, Citation2020; Y. Lu & Guo, Citation2021; S. W. Hsiao et al., Citation2010) are also significant for the small household appliances’ market appeal.

The second contribution to the literature is the top Kansei words with a mean value score higher than 4.0, depending on the SD Questionnaire 2 responses. These words are “striking, contemporary, trend follower, speedy, beautiful and dissimilar”. Although all 20 high-level Kansei words represent consumers’ feelings on TCMs, those mentioned above are the most powerful ones. We could not encounter “striking, trend follower and speedy”; instead, we found “contemporary, beautiful and dissimilar” in the literature (K. A. Hsiao & Chen, Citation2006; Kang, Citation2020; Y. Lu & Guo, Citation2021; S. W. Hsiao et al., Citation2010) related to KE studies on the small household appliances.

The word “striking” is generally utilised in KE studies, such as packaging (Effendi et al., Citation2020) and shoes (Shieh & Yeh, Citation2013). This term was not previously encountered in our KE investigations on small household appliances. It is estimated that the word striking was rated highest by consumers because it is a relatively novel product, and new TCM models are entering the market frequently. Therefore, consumers may not have seen some of these products before and find them “striking” due to this innovation. Secondly, the word “speedy” is widely used in KE studies on goods connected to transportation, such as automotive (Nagamachi, Citation1995) or sports-related goods, such as sneakers (C. C. Wang et al., Citation2016). This word might be a specific word used in TCMs among small house appliances, as we could not find the “speedy” word in KE studies in this field. The main reason might be that making coffee with TCMs takes a shorter time than with traditional coffee pots, and also, making quick coffee is an advantage for consumers in today’s fast-paced world. Therefore, the participants may have associated this word and TCMs in their minds. Lastly, “Trend follower” is a popular word in the design world, which means that the designed product traces technological developments in similar fields and the appearance of similar products. We extracted this word from the designer interviews; however, we could not find its use in KE applications. Our findings show that consumers define this product as a “trend follower”.

5.2. Practical implications

The study’s results offer significant guidelines for practitioners. The first practical contribution is the obtained Kansei words related to small household appliances. We found nine high-level Kansei words dissimilar from the literature (K. A. Hsiao & Chen, Citation2006; Kang, Citation2020; Y. Lu & Guo, Citation2021; S. W. Hsiao et al., Citation2010) which are “energetic, artistic, trend follower, sympathetic, timeless, speedy, well-considered, striking and luxurious”. We estimate that we acquired these words because we began the study with a high number of Kansei words (384). Moreover, these words may directly relate to TCMs. On the other hand, designer interviews on TCMs might assist in finding these unique words, such as “trend follower”. Finally, we envision that KE researchers might utilise these Kansei words “energetic, artistic, trend follower, sympathetic, timeless, speedy, well-considered, striking and luxurious” in other KE studies on small household appliances.

The second practical contribution is regarding the revealed design factors. According to Nagamachi and Lokman (Citation2016), it is possible to ensure the market success of new products designed depending on design factors. As the authors mentioned, it would be advantageous for designers to connect these design factors: “stylish, easy to use, joyful, trend follower, youthful, functional, desirable, youthful, dissimilar, and luxurious” to the selected domain. For instance, they can design a TCM that is easier to use and more dissimilar. TCM designers also can use images related to these design factors to be inspired and make their design process more practical and enjoyable, considering the literature (Zabotto et al., Citation2019).

Thirdly and most significantly, our findings can guide the designers and NPD experts by revealing the correlations between customers’ hedonic Kansei and the Turkish Coffee Makers’ properties related to their appearances. We presented two optimum designs: (1) “Square with fillet (top), Trapezoid (front) and C-shape cornered (right), two-colour (main body)”; (2) “Amorphous (top), Amorphous (front) and Z-shape reverse (right) and one-colour (main body)”. Designers can use these findings in their TCM projects and interpret them depending on the design briefs. S. W. Hsiao et al.’s (Citation2010) study has a similar approach. Although their domain is drip coffee makers, we focus on similar product properties, such as the main body of coffee makers. While we conducted a PLS analysis to synthesise Kansei words and TCM properties, S. W. Hsiao et al. (Citation2010) performed genetic algorithms method. In order to analyse the data, they utilised a specific GA program for product form design that aided the authors in creating more designs. On the other hand, we utilised IBM SPSS V.28 and Microsoft Excel XLSTAT for the analysis.

Furthermore, in the study of S. W. Hsiao et al. (Citation2010), the number of parts of drip coffee makers is higher than the TCMs’; therefore, they indicated more optimum design alternatives (twelve). They presented combinations of these parts as the optimum designs considering the study findings. Shieh and Yeh (Citation2013) also displayed eight optimum designs for each Kansei word related to running shoes depending on PLS results. One reason for presenting a high number of designs is that the number of parts of these products is high; the other reason for having more optimum designs is that designers and companies may choose a comprehensive solution from various choices.

By considering the advantages of offering a high number of optimum designs, we can propose an additional method to enhance designs. For instance, by combining and crossing positive high-scored top, front, right views and main body colours, it is possible to increase the number of optimum designs depending on the PLS results, similar to the literature (Shieh & Yeh, Citation2013; S. W. Hsiao et al.’s, Citation2010). Namely, we can utilise Tables to create new optimum designs for TCM design. Other KE studies related to sunglasses (Chuan et al., Citation2013) and websites (Abdi and Greenacre, Citation2020) have similarities in reflecting the PLS results into optimum designs. However, it is challenging to compare the results of our study with the results of Chuan et al. (Citation2013) and, Abdi and Greenacre (Citation2020), S. W. Hsiao et al. (Citation2010) studies because the domains are different.

5.3. Comparison of optimum TCM designs and aesthetic design principles

5.3.1. Optimum design 1

The first optimum design of the study, based on the PLS analysis, includes “Square with fillet (top), Trapezoid (front) and C-shape cornered (right), two-colour (main body)” properties. When we examine the products containing these features among 16 stimuli, we see that they have the following design principles; balance, complexity, good continuance, curvature, proportion, similarity, symmetry, and unity.

Firstly, S1 and S4 products have “square with fillet” property in the top view. A1 and A4 images, including “square with fillet”, show the top and bottom views of S1 and S4 products. By interpreting these images, we can claim that; these forms consist of symmetry in vertical axes, balance through symmetry, the similarity between the top and bottom views, which have the same shapes at different scales; curvature through square fillets; reasonable proportion between the top and bottom views; The unity of the view in two different dimensions, top and bottom. Secondly, S1, S4 and S5 products have Trapezoid” form in the front view. B1, B4, and B5 images show these products’ “Trapezoid” front view forms. By examining these shapes, we can propose that these forms have symmetry on the vertical axis, symmetry-related balance, curvature through trapezoid shape’s fillets, good continuance with the convex outline of trapezoid form; the similarity between the upper and lower curves, which are parallel, and the left and right curves, which are symmetrical. Thirdly, S1, S4, S5 and S16 have “C-shape cornered” feature in the right view. C1, C4, C5, and C16 images show these products’ “C-shape cornered” right view shapes. By observing these forms, we can claim that these products have complexity as these forms make coffee pots visible and, make these products more complex than others. Moreover, these right views forms have asymmetric balance; good continuance due to concave, closed and flowing structure; curvature through fillets, the reasonable proportion with their concave structures; the similarity between the upper and lower forms; unity with its concave structure, coffee pot and space. Finally, the products with the highest score are S1, S3, S8, S13, S14 and S16 with two colours. We can say that the colours of these products provide an asymmetrical balance and unity with these two different colours. These products also include similarity due to the use of the same colour in various parts and complexity due to the use of multi-colour.

5.3.2. Optimum design 2

The second optimum design of the study depending on the PLS analysis, consists of “Amorphous (top), Amorphous (front) and Z-shape reverse (right) and one-colour (main body)” features. When we examine the products containing these properties in 16 stimuli, we can observe that these products include the design principles of balance, complexity, good continuance, curvature, proportion, similarity, symmetry, and unity.

Firstly, S14 has “Amorphous” form in the top view, represented by the A14 image. This image indicates the top and bottom shapes of the respective stimulus. When we analyse the A14 form, we can see that this form has curvature and good continuity predominantly, a symmetrical balance, similarity and reasonable proportion between upper and lower figures, and unity of two different forms, upper and lower. Secondly, the front view of S14 has the “ Amorphous “ form represented by the B14 figure. This image shows the outline of the front view of S14. We can observe that this B14 form contains curvature and good continuity with a convex and flowing form predominantly, a symmetrical balance, similarity of the right and left parts and a reasonable proportion between them. Thirdly, S14 has “Z-shape reverse” form that represents the C14 shape in the right view. This C14 image shows the outline of the right view of S14. We can claim that this form has asymmetrical balance and unity in variety, curvature provided by fillets, good continuance and reasonable proportion of the concave and closed form. This form also includes complexity as it makes the coffee pot visible. Finally, the one-coloured S4 and S11 products ranked second among all colour alternatives. However, since the coffee pot or coffee pot handles of these products are coloured, these products are seen as two-coloured when used with the coffee pot. Therefore, we can claim that these products provide asymmetrical balance, unity and complexity with these two colours.

We can claim that the design principles were successfully applied in the highest-scoring TCM stimuli. Consumers aesthetically appreciate the products mentioned above in form and colour, especially the more complex products were ranked higher in this study, consistent with the literature (Van Geert & Wagemans, Citation2021).

5.4. Limitations and further studies

Although hedonic and pragmatic Kansei are utilised in similar KE studies, we eliminated pragmatic Kansei in this study because it is difficult to vote for pragmatic emotions online without using or touching them. The eliminated words from the high-level Kansei are “easy to use, functional, easy to comprehend, durable, successful, and ideal capacity”. Additionally, we eliminated the words related to the coffee taste produced by TCMs in the study’s beginning. Therefore, a face-to-face study can be conducted in future studies, and these variables can be examined later. This study also focused only on the form and colour attributes among all product features of TCMs. Future studies may examine material and texture properties with the KE methodology, which are TCM’s other product aesthetic properties. Moreover, due to time restrictions, we solely concentrated on the main body of this product; therefore, a Kansei Engineering study on the coffee pots of TCMs might be conducted in the following research.

Several researchers have defined design factors in three categories: aesthetic, symbolic and utilitarian. (Benaissa & Kobayashi, Citation2022; Brunner et al., Citation2016; Candi et al., Citation2017; Creusen & Schoormans, Citation2005; Eisenman, Citation2013; Homburg et al., Citation2015; Noble & Kumar, Citation2010; Rafaeli & Vilnai-Yavetz, Citation2004). In this KE application study, we only focused on the TCMs’ aesthetic qualities due to the online structure of our research. Further studies can analyse the utility properties of TCMs, such as coffee and coffee foam quality, cooking time, ergonomics of pot handle and warning sound, with KE methods. Additionally, the symbolic properties of TCMs can be explored with Kansei Engineering methodologies in future studies. For instance, the use of cultural motifs, traditional coffee pot forms, traditional materials and textures such as copper, and customization of TCMs can be examined within the scope of KE.

The TCM product is an invention that was first introduced in 2004; It has only 18 years of history. Therefore, product feature alternatives, especially form alternatives, are limited so that designers can perform Kansei Engineering studies with their novel TCM projects, CAD drawings, form designs and design features. In addition, they can use rendered visuals of CAD drawings in online surveys. On the other hand, VR technology is another option for presenting CAD drawings to consumers for evaluation. We eliminated size, proportion and dimension properties because of the time limitation, and form and colour are the main focuses of the ongoing PhD study. However, the size property can be analysed using the same data in the future.

Designers utilise both objective and subjective tools in their design processes. The basic design principles and Gestalt Laws are some of these objective intermediaries (Crilly et al., Citation2004). On the other hand, Kansei Engineering is a subjective tool that provides design inputs based on how consumers feel about the products (Schütte et al., Citation2004). As a result, how designers can use these objective and subjective tools together is another design research proposal for future work.

After the Turkish coffee maker was invented, it became popular in other countries. Therefore, this is an opportunity for researchers to carry out cross-cultural designs on TCMs. In summary, the design researchers may conduct a similar KE study with local people from other countries and different cultures. These proposed studies may also benefit TCM manufacturers aiming to trade internationally.

6. Conclusion

The problem addressed by the study is the high competition among small household appliances and the necessity for innovation in Turkish Coffee Makers. Until recently, several innovative strategies have been used in the NPD process of small household appliances, such as the use of bioplastic (Cecchini, Citation2017), the use of sustainable materials (Ceschin & Gaziulusoy, Citation2016), technology-push and market-pull innovation (Choi, Citation2018) and customer-driven innovation (Desouza et al., Citation2008). However, Kansei Engineering, an emotional, statistical, and computer-aided innovation method, has not yet been applied to these machines. Therefore, this study aimed to apply Kansei Engineering techniques and provide design inputs and hints on TCMs to industrial designers through the outcomes. In order to achieve this purpose and sub-goals, which are identified in Section 1, we conducted a set of methods, including the collection of Kansei words, affinity diagram, selection of product properties, SD Questionnaire 1–2, factor analysis, PLS analysis, and the development of optimum designs. The related results are presented in Section 4 and discussed in Section 5. Lastly, this section is organised depending on the conclusions and their relations to the sub-goals of the study.

Goal 1: to explore consumer emotions, high-level Kansei words and design factors regarding TCMs.

Kansei term is utilised as the customers’ feelings and thoughts on products and a significant component in Kansei Engineering research. This study conducted a comprehensive investigation to determine consumers’ Kansei concerning TCMs. 384 Kansei words were gathered from varied sources defined in Section 3. In order to extract the most influential (high-level) Kansei words, the affinity diagram method, SD Questionnaire 1 and Factor Analysis 1 were performed. High-valued and dissimilar 20 Kansei words were extracted from the factor analysis results, which are “creative, pleasurable, energetic, artistic, trend follower, stylish, timeless, sympathetic, innovative, speedy, well-considered, elegant, showy, dissimilar, young, luxurious, contemporary, beautiful, striking, joyful”. If experts design the TCMs to evoke consumers’ these emotions, these products have a high probability of success in the market.

Additionally, this study found the design factors as “stylish, easy to use, joyful, trend follower, functional, youthful, dissimilar, and luxurious, “ obtained from factor analysis 1. Therefore, we recommend that designers may develop the TCMs depending on these factors to ensure market appeal.

Goal 2: to investigate the affective dimensions of TCMs.

The affective dimensions of 16 Stimuli related to 20 high-level Kansei words are some of this study’s significant outcomes concerning Goal 2. In order to examine these dimensions, a descriptive analysis was conducted using the data gathered from SD Questionnaire 2. Affective dimension findings presented in Section 4 include several design hints on TCMs for designers. Our findings indicate that the products S14, S12, S8, S7, S5, S4, S1 and S3 have the highest mean scores, respectively, and these products may inspire designers in terms of appearance. For instance, consumers found S14 the most desirable product related to 20 Kansei words. On the other hand, consumers found these 16 stimuli “striking, contemporary, trend follower, speedy, beautiful and dissimilar” mainly and sequentially depending on mean scores.

Although S14 has the highest mean scores, consumers found S12 the most “striking”; it is estimated that S12ʹs different form design and size from the other products made this product more “striking”. On the other hand, consumers found the S1 and S4 as the most “contemporary, trend follower and beautiful” products. S1 has the strongest relation with contemporary and trend followers; S4 has the most substantial relation with beautiful. However, the mean value scores are close to each other, and the form designs are similar. We estimate that consumers perceived S1 and S4 products as more “contemporary, trend follower and beautiful” due to their minimal and geometrical forms, use of materials effective, and application of large fillets on the main body design. Furthermore, S5 has the highest mean scores related to the “speedy” word, its compact and circular form design, its use of steel on the coffee pot and the handle, and the use of less material. Lastly, it is considered that consumers found S14 most dissimilar due to its amorphous and organic form design, although the other products generally have orthogonal, circular and geometric forms.

Designers can use these affective dimension tables after deciding what emotion they want to evoke in consumers. For instance, if they want to design a “striking” TCM, they may design a different product from the other products. On the other hand, if they want to develop a “contemporary, trend follower and beautiful” TCM, they may use geometric and minimal forms, largely fillets with less material. Additionally, if their purpose is to design a TCM product perceived as “speedy”, the designer may design a coffee pot in steel and the main body compact. Lastly, if the purpose is to design a product “dissimilar”, they can develop it in amorphous and organic forms. This list can be expandable depending on the affective dimension of Tables in Section 4.

Goal 3: to find out the relationships between product features and consumer emotions,

This study conducted a PLS analysis to achieve Goal 3. As a result, the correlations between customers’ hedonic Kansei and the form and colour properties of Turkish Coffee Makers were revealed in Section 4. We simplified the process using the eight high-level Kansei words: “creative, pleasurable, stylish, timeless, well-considered, elegant, luxurious and contemporary”. However, the correlations between the word “luxurious” and colour properties have different outcomes from the findings below and explained in Section 4.

In this study, all properties belong to the main body of TCMs, and consumers found the features with positive mean values more desirable. Our findings show that the top view category has five alternatives with positive mean values: “Square with fillet, Amorphous, Semicircle-rectangle (vertical) compound, Rectangle with fillet and Circle”; the front view category has four positive mean values: “Trapezoid, Amorphous, Other geometry, and Rectangle with fillet”; the right view category has three positive mean values: “C-shape cornered, Z-shape reverse and Z-shape”; the colour category has two positive mean values: “two colours and one colour”. These properties are ranked according to their values. These product categories can be considered a conceptual base for shape creation, in other words, ideation for designing a new TCM. The designers may select and combine these product categories or interpret them depending on their design skills and design brief.

Goal 4: to indicate the most desired product features

The first three high-valued and the most desired TCM product attributes that impact consumers’ Kansei are shown below and in Section 4. “Square with fillet, Amorphous and Semicircle-rectangle (vertical) compound” are the highly valued top views. “Trapezoid, Amorphous and Other geometry” are the high-impact front views. “C-shape cornered, Z-shape reverse and Z-shape” are the top-rated right view properties. “Two-colours and one-colour” are the most desired colour features of TCM main bodies. Namely, our findings show that “Square with fillet” on the top view, “Trapezoid” on the front view, “C-shape cornered” on the right view, and “Two-colours” as the main body colour have the strongest influences on consumers’ Kansei for the TCMs. Additionally, it is observed that one-coloured TCMs have a coffee pot with a different colour from the main body; therefore, we estimate that designing the whole product in two colours is advantageous.

Goal 5: to create optimum designs

This study presents two optimum designs for designers’ inspiration depending on the findings explained in Section 4. The first optimum design is the combination of “(1) Square with fillet (top), (2) Trapezoid (front) and (3) C-shape cornered (right) and (4) two-colour (main body)”, and the second one includes “Amorphous (top), Amorphous (front) and Z-shape reverse (right) and one-colour (main body)”. These optimum designs can be utilised as a design evaluation tool and a shape guide for industrial designers. In addition, industrial designers can compare their designs with these optimum designs to make design decisions for their project process.

To sum up, it is expected that all these study outcomes will assist designers in determining the form and, colours, appearance properties of TCMs more efficiently in their TCM design processes.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Müge Göken

Müge Göken is a research assistant and PhD candidate at Istanbul Technical University in the department of Industrial Design. She has a B.S. degree from Middle East Technical University and MSc. Degree in Izmir Institute of Technology in the department of Industrial Design. She has six years of experience in the R&D departments of the construction industry and collaborated with the following companies: Valfsel Armatür Sanayi A.Ş., an Elginkan Community foundation; Ege Vitrifiye, an İ. Polat Holding foundation.

E. Cem Alppay

Cem ALPPAY is an industrial designer and is working as an Assistant Professor at the Industrial Product Design Department in Istanbul Technical University. He holds a PhD degree in industrial product design mainly focused in human factors and ergonomics. After completing his PhD dissertation, he worked as a visiting researcher in the Department of Design and Environmental Analysis at Cornell University. His professional areas of interest include ergonomics in consumer products, user-interface design and ergonomics, user-experience medical product design and ergonomics, new product development.

References

- Abdi, S. J., Greenacre, Z. A., & Meng, W. (2020). An approach to website design for Turkish universities, based on the emotional responses of students. Cogent Engineering, 7(1), 1770915. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311916.2020.1770915

- al-Rifaie, M. M., Ursyn, A., Zimmer, R., & Javid, M. A. J. (2017, April). On symmetry, aesthetics and quantifying symmetrical complexity. In International Conference on Evolutionary and Biologically Inspired Music and Art (pp. 17–36). Springer, Cham.

- Arnheim, R. (1983). The power of the center: A study of composition in the visual arts. Univ of California Press.

- Arnheim, R. (1988). Symmetry and the organization of form: A review article. Leonardo, 21(3), 273–276. https://doi.org/10.2307/1578655

- Aykin, N. (2005). Overview: Where to start and what to consider. In Aykin, N. (Ed.), Usability and internationalization of information technology (pp. 3–20). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Babin, B. J., Darden, W. R., & Griffin, M. (1994). Work and/or fun: Measuring hedonic and utilitarian shopping value. Journal of Consumer Research, 20(4), 644–656. https://doi.org/10.1086/209376

- Bar, M., & Neta, M. (2006). Humans prefer curved visual objects. Psychological Science, 17(8), 645–648. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01759.x

- Batra, R., & Ahtola, O. T. (1991). Measuring the hedonic and utilitarian sources of consumer attitudes. Marketing Letters, 2(2), 159–170. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00436035

- Bauerly, M., & Liu, Y. (2008). Effects of symmetry and number of compositional elements on interface and design aesthetics. Intl. Journal of Human–Computer Interaction, 24(3), 275–287. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447310801920508

- Baxter, M. (2018). Product design. CRC press.

- Benaissa, B., & Kobayashi, M. (2022). The consumers’ response to product design: A narrative review. In Ergonomics (pp. 1–30).

- Berlyne, D. E. (1973). Aesthetics and psychobiology. Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 31, 4.

- Berlyne, D. E. (1974). Studies in the new experimental aesthetics: Steps toward an objective psychology of aesthetic appreciation. Hemisphere.

- Bertamini, M., Palumbo, L., Gheorghes, T. N., & Galatsidas, M. (2016). Do observers like curvature or do they dislike angularity? British Journal of Psychology, 107(1), 154–178. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjop.12132

- Bouchard, C., Lim, D., & Aoussat, A., 2003. Development of a Kansei Engineering System for industrial design. Proceedings of the Asian Design International Conference 1, 1–12.

- Brunner, C. B., Ullrich, S., Jungen, P., & Esch, F. R. (2016). Impact of symbolic product design on brand evaluations. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 25(3), 307–320. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-06-2015-0896

- Candi, M., Jae, H., Makarem, S., & Mohan, M. (2017). Consumer responses to functional, aesthetic and symbolic product design in online reviews. Journal of Business Research, 81, 31–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.08.006

- Castilla, N., Llinares, C., Bravo, J. M., & Blanca, V. (2017). Subjective assessment of university classroom environment. Building and Environment, 122, 72–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2017.06.004

- Cecchini, C. (2017). Bioplastics made from upcycled food waste. Prospects for their use in the field of design. The Design Journal, 20(sup1), S1596–S1610. https://doi.org/10.1080/14606925.2017.1352684

- Ceschin, F., & Gaziulusoy, I. (2016). Evolution of design for sustainability: From product design to design for system innovations and transitions. Design Studies, 47, 118–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.destud.2016.09.002

- Chang, Y. M., & Chen, C. W. (2016). Kansei assessment of the constituent elements and the overall interrelations in car steering wheel design. International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics, 56, 97–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ergon.2016.09.010

- Chen, M. C., Chang, K. C., Hsu, C. L., & Xiao, J. H. (2015). Applying a Kansei engineering-based logistics service design approach to developing international express services. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 45(6), 618–646. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPDLM-10-2013-0251