Abstract

Even though both empirical and field evidence hail integrated pest management (IPM) as promising techniques for cost-effective and environment friendly control of agricultural pests, coffee farmers still rely on pesticides. A post coffee stem borer IPM training survey of 126 farmers reveals that farmers’ attitudes toward pesticides is a major constraint to IPM use. Farmers perceived that pesticide use simplifies pest management, produces higher yields and good quality coffee appealing to the buyers. On this basis, they mainly used pesticides compared to IPM practices for Coffee Stem Borer (CSB) pest management. Second, the CSB IPM practices are less appealing because of the high labor requirements and costly nature and therefore a constraint especially to women and the elderly. Consequently, increasing IPM practices uptake requires a deliberate and collective effort of key coffee sector stakeholders to design and implement educational programs aimed at judicious application of pesticides. After that, a continuous testing of more IPM techniques coupled with encouraging farmers to adapt and make modifications on the current practices can potentially reduce pesticide use.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

While the provision of less harmful, environment friendly, effective pest control solutions is a main aim in modern crop protection, farmers’ dependence on pesticides is far from over. Farmers equate pesticide use to better yields desired by the market. Furthermore, farmers consider deployment of a variety of pest management strategies to complement, reduce or replace the application of synthetic pesticides to be labor-intensive and costly to implement. The study findings have relevance to effective public policies on health and environmental protection formulation especially in developing countries experiencing policy dilemma in pesticide use compliance measures. Similarly, research and development partners ably design and implement more gender-sensitive programs after understanding different reasons for gender-based use of pesticides instead of integrated pest management practices.

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

1. Introduction

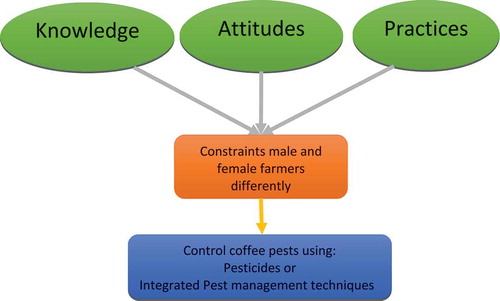

In the era of modern agriculture, crop protection including that of coffee has been a center of focus in the recent years. Crop protection involves selecting and applying context-specific crop pest solutions by farmers to obtain high yields. To successfully select and apply appropriate pest control methods, farmers must learn to develop their skills and knowledge on the relevant pest control methods. The knowledge obtained in turn shapes farmers attitudes and practices regarding pest control method selection and use. In fact, recent evidence suggests that farmers’ knowledge, attitudes and practices influence their choice of pesticides over different methods particularly in developing countries (Atreya, Johnsen, & Sitaula, Citation2012; Khan & Damalas, Citation2015a). Currently, farmers have to choose either pesticides or integrated pest management (IPM) techniques as their pest control methods.

Actually, a majority of farmers rely on pesticides as the effective crop pest control solution (Damalas, Citation2009; Damalas & Eleftherohorinos, Citation2011; Schreinemachers et al., Citation2017) as compared to IPM. Indeed scholars, practitioners and policymakers have found that farmers equate instant pest killing action as well as labor and time saving to effectiveness in crop pest control (Chen, Huang, & Qiao, Citation2013; Hou, Huang, Wang, Hu, & Xue, Citation2012). Whereas farmers hail pesticides for their performance, pesticides have negative effects on the environment and human well-being (Jallow, Awadh, Albaho, Devi, & Thomas, Citation2017; Kim, Kabir, & Jahan, Citation2017; Nicolopoulou-Stamati, Maipas, Kotampasi, Stamatis, & Hens, Citation2016; Souza, Costa, Maciel, Reis, & Pamplona, Citation2017; Valcke et al., Citation2017; Verger & Boobis, Citation2013; Wang, Chu, & Ma, Citation2018). Accordingly, scholars have a task to unearth reasons for continuous dependence on pesticides by farmers to increase their knowledge on correct pesticides use and regulation.

Investigations have revealed that limited knowledge, poor attitudes and practices (KAP) regarding pesticides (Schreinemachers et al., Citation2017) are the main reasons for farmers’ dependence on pesticides. Indeed, most scholars have found that farmers’ have limited knowledge of pesticide use, risks and safety measures (Chen et al., Citation2013; Damalas & Hashemi, Citation2010; Fan et al., Citation2015; Hashemi, Rostami, Hashemi, & Damalas, Citation2012; Khan & Damalas, Citation2015a; Lekei, Ngowi, & London, Citation2014; Mengistie, Mol, & Oosterveer, Citation2017; Mohanty et al., Citation2013; Sa’ed et al., Citation2010; Wang, Jin, He, & Gong, Citation2017; Yang et al., Citation2014; Zhang, Guanming, Shen, & Hu, Citation2015). Moreover, farmer’s limited knowledge about pesticide use and alternative pest control methods is responsible for farmers’ beliefs regarding pesticide performance and effectiveness (Cameron, Citation2007; Damalas & Koutroubas, Citation2014; Hashemi & Damalas, Citation2010; Mengistie et al., Citation2017; Schreinemachers et al., Citation2017). Then, farmers’ limited knowledge and believes about pesticides effectiveness are responsible for their incorrect pesticide application methods; for example, wrong spray preparation and actual spraying operations, a result of low education levels or information, limits farmers’ ability to read precautionary labels on pesticides containers (Damalas & Koutroubas, Citation2016; Grovermann, Schreinemachers, & Berger, Citation2013). While it’s clear that farmers’ limited KAP explain high farmers dependence on pesticides as compared to other pest control methods, these findings cannot be applied across contexts.

In fact, there is a persistent call for research that considers the farming context specific pest management solutions. Indeed, context-specific pest management solutions should take into account the heterogeneous nature of farmers, diversity of crops and pest in a particular location (Zhang et al., Citation2015). To this end, some studies have demonstrated that male and female farmers’ knowledge, attitudes and practices differ, yet few studies have exhaustively investigated these differences. Particularly, few studies have demonstrated gender differences in the level of pesticide KAP. For instance, some scholars have found that male farmers have a better knowledge of pests, pesticide use than female farmers (Atreya, Citation2007; Chetna, Vaibhav, Pallavi, & Jitendra, Citation2012; Christie, Van Houweling, & Zseleczky, Citation2015; Kasner et al., Citation2012; Wang, Jin, et al., Citation2017). Relative to their male counterparts, women experience barriers in accessing agricultural information and knowledge about pesticide use, risks and safety measures (Akter, Krupnik, Rossi, & Khanam, Citation2016) due to, for example, their socially ascribed roles that limit their movements. Much as pesticides use knowledge varies between male and female farmers, so do attitudes and practices, yet little effort has been made to explain the variation. Apart from the variations among farmers level of KAP, other contextual variations such as pest, crops are still unaccounted for. For this reason, understanding differences (constraints) between male and female farmers level of KAP across for different crops and pests does not only make it easy to regulate excessive pesticide use but increase IPM approach adoption as alternative pesticides.

IPM, a rational deployment of a variety of pest management techniques is designed to complement, scale back or replace the application of synthetic pesticides (Ahuja, Ahuja, Singh, & Singh, Citation2015; Ehler, Citation2006; Pretty & Bharucha, Citation2015; Rao, Kumari, Sahrawat, & Wani, Citation2015). IPM techniques involve implementation of assorted strategies like regular scouting of plants for pests and diseases, correct crop rotation and use of resistant varieties, healthy seedlings, use of biopesticides and biocontrol agents (Pretty & Bharucha, Citation2015). Despite IPM’s apparent benefit of being less harmful to the environment and human beings, low adoption has been registered for smallholder farmers (Allahyari, Damalas, & Ebadattalab, Citation2017; Clausen, Jørs, Atuhaire, & Thomsen, Citation2017; Damalas & Khan, Citation2016; Jayasooriya & Aheeyar, Citation2016; Khan & Damalas, Citation2015a, Citation2015b; Ochilo et al., Citation2018; Rahman, Norton, & Rashid, Citation2018). The low adoption of IPM by farmers can be traced to the controversy about scientific evidence for IPM’s cost-effectiveness that has raged unabated for over a decade. Farmers incredibly doubt the cost-effectiveness of IPM techniques i.e. heavy labor demand and yet delay to deliver results—low crop yields (Egonyu et al., Citation2015). Factors such as these challenge the actual scientific evidence that IPM is more cost-effective or better for health thus justifying farmer use of pesticides (Atreya, Citation2007). Thus, a critical step to address this misconception is to separately identify constraints faced by male and female farmers while using IPM techniques, which constraints determine whether or not farmers choose pesticides over IPM.

Broadly, this gap was addressed through a descriptive survey of 71 men and 55 women to assess gender differences herewith referred to as constraints in knowledge, attitudes and practices of coffee stem borer pest management in Sironko and Namisindwa (former Manafwa) districts, Uganda. More specifically, the survey is broken down into three small parts: First, identify gender differences in the level of knowledge, attitudes and practices relating to IPM techniques. Additionally, identify gender differences in the level of knowledge, attitudes and practices relating to pesticides. The findings of this study will not only guide more rational and effective public health and environmental protection policy formulation (Fan et al., Citation2015; Jin, Wang, He, & Gong, Citation2016) but also contribute to the literature on understanding gendered constraints to adoption of pest control techniques in developing countries.

2. Methods

2.1. Description of the study area

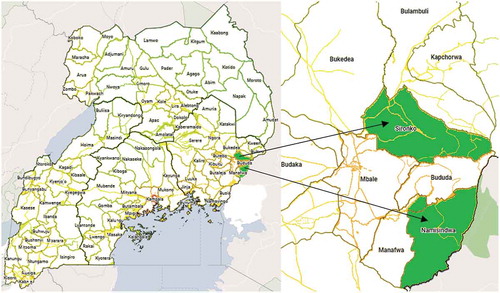

This study was conducted in the typical coffee growing area of Mt Elgon region of Uganda covering the districts of Sironko and Namisindwa (Figure ). The coordinates of the Sironko and Namisindwa districts are 1.1608° N, 34.2866° E, 0.9064° N, 34.23° E, respectively. According to 2016 population estimates, Uganda Bureau of Statistics puts Sironko and Namisindwa districts at about 113,500 and 178,746 people, respectively.

2.1.1. Farming system and coffee agronomy

Mt. Elgon is characterized under the banana–coffee farming system where mixed farming is predominant. The area has deep, fertile soils, well-distributed rainfall, relatively high altitude and with large tree vegetation coverage that supports coffee growth. Coffee (Coffea arabica L.) is the main income source alongside other activities. Coffee often intercropped with bananas is mainly grown by smallholder farmers on farm sizes of less than one acre on average (Jassogne, Lderach, & Van Asten, Citation2013). Arabica coffee is the most grown on the slopes of Mountain Elgon (1,500–2,300 m above sea level) (Ahmed, Citation2012) because of favorable climatic conditions temperatures between 15C and 24°C (59 and 75°F) and banana shades. Coffee plants grow up to 5 m tall but usually kept at about 2 m to ease harvesting. Coffee flowers are small and white, they smell like jasmine flowers, sweet and pretty. The beans (which are actually seeds) are found inside of the berries that grow on this shrub-like plant. The berries are usually handpicked when “cherry” or deep-red/dark-purple often have two beans in each berry. When the arabica coffee beans are removed from the berries, there is also a “parchment coat” and a “silver skin” that have to be removed.

Currently, coffee yields range from 1,556 to 1,776 kg/ha. This average yield is below the production potential of 2,000 kg/ha for Arabica coffee under good management practices. The low production is attributed to high incidence of diseases and pests. The white coffee stem borer (Monochamus leuconotus [Pascoe] [Coleoptera: Cerambycidae]), the second most important pest of Arabica coffee in Uganda (Egonyu et al., Citation2015; Jonsson, Raphael, Ekbom, Kyamanywa, & Karungi, Citation2015), causes up to 80% loses (Egonyu et al., Citation2015; Kutywayo, Chemura, Kusena, Chidoko, & Mahoya, Citation2013). Like other borers, coffee white stem borer is difficult to control, as most of its lifetime is spent inside the stem (Table )/Figures -. Cultural control measures such as soil amendments reduce infestation and damage, as healthy and strong trees are less susceptible to attack (Knight, Citation1939). Other cultural practices, such as bark smoothing, stem wrapping with banana leaves to prevent oviposition or larvae killing by driving a wire into galleries, are used (Rutherford & Phiri, Citation2006). Chemical treatments with insecticides showed variable efficiency (Egonyu et al., Citation2015; Rutherford & Phiri, Citation2006) and are minimally used by coffee smallholders. However, these practices are not efficient enough to keep coffee white stem borer damage at an economically acceptable level (Egonyu et al., Citation2015) and so farmers continue to use pesticides to achieve high agricultural productivity.

2.2. Survey instrument and data collection

A structured interview questionnaire that had been subjected to content validity by a panel of experts and suitability tests through pretesting was used to collect data from the sample. The final questionnaire contained three sections: (1) farmers’ demographic information; (2) farmers’ knowledge, attitudes and practices of CSB IPM; (3) farmers’ knowledge, attitudes- pesticide use risk awareness and practices (Table ). The KAP were adopted as an analytical lens due to frequent use in studies on pesticide exposure (Brown & Khamphoukeo, Citation2010; Karunamoorthi, Mohammed, & Wassie, Citation2012; Recena, Caldas, Pires, & Pontes, Citation2006; Yang et al., Citation2014). This method (KAP) of assessment is particularly useful in studying what coffee farmers know about the problem, how they feel about it and how they behave. A purposive sampling method was employed to select 71 male and 55 female farmers from the list of 3 coffee IPM farmer groups. A purposive sampling technique was chosen because of the expected difficulty in obtaining a statistically acceptable sample. At the study time, all the three farmer groups formerly farmer field schools had been graduated by the IPM CRSP project, making the traceability of a majority of the members difficult. These three groups had received training on IPM techniques such as stem smoothening, wrapping, stumping, pruning and soil amendments under the IPM CRSP funding. The coffee IPM interventions commenced after a baseline survey of Arabica coffee producers in the districts of Sironko, Manafwa and Mbale. The farmers in the study areas were found to use pesticides as the main control method for stem borers. The National Agricultural Research Organization Coffee Research Program-Coffee Research (COREC) in collaboration with IPM Collaborative Research Support (IPM CRSP) beneath United States Agency for International Development funding carried out research in 2008 to compare the conventional method of pest control in coffee, which involved chemical pesticide application with IPM management methods (stem smoothening and stem wrapping), and thereafter the later were found to be effective. Hence, between 2009 and 2010, the IPM choices were evaluated on farm. The results from the on-farm trial were positive, and so the IPM packages were upscaled in 2009 through coffee IPM groups in two subcounties (Bumbo and Bupoto) of Manafwa District (present Namisindwa district). One subcounty (Buwalasi) in Sironko district was other in 2010. Coffee IPM group members would meet twice a calendar month at a coffee demonstration field at a farmer’s home. Learning methods were experiential, participatory and learner-centered. Farmers followed the coffee IPM management activities listed on a coffee management calendar covering the whole year. Four calendar months, March to June, were earmarked for scouting and controlling coffee pests including CSB.

Table 1. Knowledge, attitudes and practices questionnaire items

2.3. Data analysis

Data were encoded, entered into and analyzed via the software IBM SPSS 18 and STATA 13, in two steps. The first step consisted of a descriptive analysis to determine the level of men and women farmers’ knowledge of the CSB control. The second step involved tests of significance i.e. t-tests for mean differences and chi-square (χ2) test for measures of association at 5% level of significance. This helped to explain the difference between the two genders in CSB control and pesticide use knowledge, attitudes and practices. A summated rating scale of the entire KAP attributes (Table ) after past studies (Erbaugh, Donnermeyer, Amujal, & Kidoido, Citation2010; Wang, Tao, Yang, Chu, & Lam, Citation2017; Wang, Jin, et al., Citation2017) was used as a basis for analysis.

3. Results

3.1. Farmer demographic characteristics

Majority of respondents were men, 56%. More than half of the participants (73%) were married. Results in Table show that men were older (over 50 years) than women (P < 0.05). All respondents had attained basic education (primary school level—7 years on average) and were able to read and write English and the local dialect. With exception of coffee farming experiences that was skewed toward men (P < 0.05), t-tests found no significant differences in mean scores of men and women in coffee acreage and the number of people who provided coffee labor in the household.

Table 2. Farmer demographic characteristics, N (men = 71, women = 55)

3.2. Knowledge of the coffee stem borer control methods

In this section, the first set of questions (five) aimed to gauge gendered differences in ability to identify the coffee stem borer while the next seven measured the awareness of the pest management methods. These questions help to draw conclusions on whether the low level of knowledge of the pest control methods by gender is responsible for the choice (attitudes and practices) pesticides over IPM practices.

3.2.1. Knowledge of the CSB pest

As shown in Table , there are gender differences in farmers’ knowledge of the CSB pest control methods. What stands out in the table is that most respondents (over 80%) were knowledgeable about coffee stem borer control methods though skewed in favor of men compared to women. The results of the correlational analysis indicated that more men could correctly identify, name the coffee stem borer, and observe the pest though skewed in favor of men compared to women at p < 0.05.

Table 3. Knowledge of the CSB pest, N (men = 71, women = 55)

3.2.2. Knowledge of the CSB IPM pest control methods

Similarly, the study indicates some gender differences in farmers’ level of awareness of IPM tactics for CSB control (Table ). More men (42%) compared to women (38%) were reported to have heard, trained and knew how to apply stem smoothening, warping, pruning and stumping. Interesting about the CSB IPM practices is the fact that there is a huge uncounted for level of awareness versus utilization. From the data, it is apparent that of the 80% who were aware of the CSB IPM practices, only 36% did utilize the practices. What strikes about the figures in this table even more is that few (36%) used the IPM practices to control CSB pest compared to 88% for pesticides. In Table , a majority of farmers access IPM practices information from IPM CRSP extension agents as compared to other sources.

Table 4. Knowledge of the CSB IPM pest control methods, N (men = 71, women = 55)

Table 5. Sources of IPM practices information, n (men = 71, women = 55)

3.2.3. Knowledge of pesticide use, risks and safety measures

When asked whether farmers were aware and used pesticides, 70% of the respondents reported that they were aware of the pesticides used to control CSB and actually (88%) applied pesticides on coffee gardens (Table ). Surprisingly, the pesticides application even exceeds the level of awareness of appropriate pesticides to control CSB pest. This implies that the level of awareness may not adequately explain farmers’ continual use of pesticides. More men (52%) compared to women (36%) were reported to apply pesticides. This is not surprising since pesticide application was generally considered a man’s role in the community. Pesticides especially ambush (53%) were preferred because of positive perceptions about CSB pest instant killing action. Other pesticides used include sumithion, rocket and copperzeb. Additionally, a majority (70%) of farmers reported that they were aware of the adverse effects of pesticides on human health, but no significant differences by gender (p > 0.05). Few farmers, 19% of men and 16% of women, thought that pesticide exposure-related illnesses can cause death.

Table 6. Knowledge of pesticide use, risks and safety measures, N (men = 71, women = 55)

All (100%) those surveyed reported awareness of positive protective behaviors, such as putting on protecting gear and carefully reading instructions before mixing and spraying pesticides. Specifically, 38% of men and 35% of men were aware of protective gear such as nose masks (p > 0.05). Similarly, few men (11%) and women (4%) indicated the importance of reading instructions before pesticides application (p > 0.05). Follow-up interviews revealed the following: First, most farmers did not take any precautions (use of protective measures, correct application and good personal hygiene) while spraying pesticides, and second, few pay attention to the technical information on pesticide usage, which is usually found on the pesticide container. Third, most could not differentiate agrochemicals based on their active ingredients or even trade names e.g. Cypermethrin, Dudu cypher, Dudu mac, an ambush is considered different yet similar.

Contrary to IPM practices, coffee farmers relied on the knowledge of those selling the agrochemicals on how to use the pesticides. Important to note is that, depending on pesticide retailers is not bad per say but pesticide retailers may be motivated by opportunities for greater profit-making and, therefore in their own interest, promote the aggressive use of pesticides. Similarly, they may be constrained by the lack of knowledge of pesticides and, consequently, are not providing accurate information to the farmers. The dependence on pesticides sellers therefore, to an extent, may account for the different choices of pesticides and the incorrect handling of these chemicals without regard to relevant technical criteria and recommendations.

3.3. Farmer attitudes about the CSB pest methods

The section captures farmers’ beliefs about CSB IPM practices effectiveness (rating), pesticide and health effects, including possible misconceptions. These questions further give pointers to reasons for possible choice of pesticides over IPM practices.

3.3.1. Attitudes toward CSB IPM practices

Respondents were asked their reasons for rating the effectiveness of CSB IPM package. In Table , stem smoothening was perceived as effective by men (46%) as opposed to pruning (70%) for women. Stem wrapping was perceived as ineffective by both gender categories. Pruning was ranked first by women due to close association with their reproductive roles i.e. women obtained firewood from the pruned twigs and the fact that stem smoothing was more labor-demanding (bending for long time) as opposed to pruning. Overall (Table ), the CSB IPM package was ranked negative because of being labor intensive. In addition to being labor-intensive, stem wrapping hides pests inside the wrapping materials (banana fibers or gunny bags) (48% of men and 30% of women) while stumping reduced coffee yields due to delay in maturity attainment (41% of men and 29% of women).

Table 7. Rating effectiveness of CSB IPM package, n (men = 71, women = 55)

3.3.2. Attitudes toward pesticide use

Results in Table indicate no gender differences in farmers’ attitudes toward CSB pest control methods. A small number of those interviewed (10% of men and 6% of women) reported that pesticides caused many health problems to you and other people in your household. Those that agreed sighted flu and cough, 48% of men and 38% of women, as major symptoms. A common view amongst interviewees (53% of male farmers and 39% of female farmers) was that the risk of pesticides to their health was high. However, 33% of women and 22% of men agreed that more pesticide use can have better effects on pest control. This finding resonated with the earlier finding where despite the level of awareness of IPM practices and pesticides dangers, a majority applied pesticide in their coffee gardens. At this point, it’s not surprising to note that 80% of both genders rated CSB IPM package as negative. Almost two-thirds of the participants (64%) said that the CSB IPM package is labor-intensive (Table ). In addition to being labor-intensive, notable among others is the fact that stem wrapping hides pests inside the wrapping materials (banana fibers or gunny bags) (48% of men and 30% of women) while stumping reduced coffee yields due to delay in maturity attainment (41% of men and 29% of women).

Table 8. Farmer attitudes about CSB pest control methods, N (men = 71, women = 55)

3.4. Farmer CSB control practices

The section captures farmers’ actual behavior (actions) that demonstrate knowledge of and attitudes toward pest management.

3.4.1. CSB IPM practices

In Table , there was no significant gender differences in IPM practices to control CSB pest. That said, though below average, slightly more men were involved with the CSB IPM package as compared to women. Besides, smoothing or wrapping the coffee stems with banana leaves, some farmers opted to smear ambush (pesticide) around the coffee stems as a measure to discourage the pest to barrow the stem. Other farmers chose to intercrop their coffee plantations with onions as a CSB repellant. Similarly, farmers also intercropped coffee with beans so as to add nitrogen into the soil, which nitrogen leads to vigorous coffee plant growth to out beat the CSB pest. Lastly, farmers regularly applied a range of phytosanitary measures such as weeding and uprooting plants with dead bark.

Table 9. CSB IPM control practices, N (men = 71, women = 55)

3.4.2. CSB pest pesticides control

Results in Table indicate that more men (52%) compared to women (36%) were reported to apply pesticides while women (men 6%, women 52%) fetch water for mixing chemicals. Then women contributed money to pay for spraying of joint coffee gardens using the income obtained from onion, cabbage and carrot sells. Women who participated in coffee garden spraying complained of the 20-liter capacity spray pump being heavy let along the strap being discomfort.

Table 10. CSB IPM control practices, N (men = 71, women = 55)

4. Discussion

Very little was found in the literature that answer the question of what specific gender differences (constraints) have an effect on farmer selection of pesticides over IPM techniques. With respect to the research question, it was found that more men were knowledgeable about the coffee stem borer management methods compared to women. Moreover, despite the high level of knowledge coffee stem borer management methods, chemical pesticides were the primary choice of over 80% growers for pest management (Keshavareddy, Nagaraj, Bai, & Kulkarni, Citation2018; Rijal et al., Citation2018). A plausible explanation for these results is farmers’ belief that more pesticide use offers better effects on pest control. Then, the IPM package as an alternative to pesticide use is labor intensive. Consequently, the knowledge of CSB IPM is not a constraint to IPM use but the negative farmer beliefs about its cost effectiveness. Such perceptions and farmers’ strong desire to secure high yields will probably encourage them to overuse pesticides (Stadlinger, Mmochi, Dobo, Gyllbäck, & Kumblad, Citation2011).

It is assumed that farmers with heighten perceptions of pesticides as risks to human health and the environment, for example due to experienced health problems from using pesticides, will decrease their pesticide use. What is surprising is that despite farmers’ awareness of health risks associated with pesticides, chemical pesticides were the primary choice for pest management. It is plausible to state that the majority of farmers in this survey do not give great weight to environmental and human health factors when applying pesticides. Farmers minimally took precautionary measures while handling chemical pesticides. These findings are not particularly surprising, because farmers who overuse pesticides apparently view them as a guaranty for high yields (Al Zadjali, Morse, Chenoweth, & Deadman, Citation2014). The study finding is consistent with studies elsewhere who found that farmers rarely used personal protective equipment while applying pesticides (Al Zadjali, Morse, Chenoweth, & Deadman, Citation2015; Bondori, Bagheri, Damalas, & Allahyari, Citation2018; Damalas & Khan, Citation2016; Mohanty et al., Citation2013; Rezaei, Damalas, & Abdollahzadeh, Citation2018; Yuantari et al., Citation2015). These findings suggest that increasing the use of protective measures could decrease the probability of pesticides poisoning (Damalas & Khan, Citation2016; Sharifzadeh, Damalas, & Abdollahzadeh, Citation2017). Finally, the CSB IPM package which would otherwise serve as an alternative to pesticides is perceived to be labor-intensive and delivers unsatisfying results over a long period of time and therefore rarely used.

5. Conclusions

The purpose of the current study was to determine specific gender differences (constraints) that affect farmer selection of pesticide over IPM techniques. Much as the level of knowledge of pesticides of the stakeholders is vital for providing sound strategies for reducing environmental and health risks, the study findings indicating that knowledge level are moderate among farmers—regardless of gender. In addition, despite farmers’ awareness of the benefits of the IPM package as compared to pesticides, they rely on pesticides as the main means to CSB pest control. The results of this study indicate that knowledge of IPM practices and health risks of pesticides may alone be inadequate to pesticides reduction campaign. More specifically, this study has raised the recurrent question of farmer perceptions about pesticides ability to deliver better yields desired by the market. Factors such as these challenge the actual scientific evidence that IPM is more cost-effective or better for health. Moreover, the CSB IPM package was less relied on by farmers because of the high labor requirement e.g. bending for a long time and cost associated. Based on the results of this study, increasing IPM practices adoption requires resources (e.g. time, people, money), a deliberate and collective effort of key coffee sector stakeholders. Another important practical implication should involve participatory testing of more IPM techniques coupled with encouraging farmers to adapt and make modifications on the current practices. Tapping into the existing working and new relationships of various stakeholders e.g. Bugisu Cooperative Union, Uganda Coffee Development Authority, Ministry of Agriculture Animal Industry and Fisheries, the private sector, NGOs and farmers to create gender-sensitive educational programs targeting safety awareness, proper use of pesticides and implementation of personal protective measures for both farmers and pesticide retailers is necessary to decrease the pesticide exposure risk of farmers. The training for pesticide retailers should lead to certification so that they may effectively disseminate accurate and reliable information to farmers.

Despite these promising results, questions remain as follows: (1) the link between IPM techniques learnt by farmers through trainings or social contacts and actual application; (2) the contribution of farmers experiences to learning and application of IPM practices and (3) more practical strategies (other than sensitization) to demonstrate the scientific relevance of IPM strategies as opposed to pesticides. Finally, replicate a similar study with an ongoing farmer field school and incorporating non-participants.

Acknowledgments

This article has no direct funding; however, data were collected as part of Robert Ochago’s Msc Thesis under the Gender Global Theme of USAID IPM CRSP project in Uganda.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Robert Ochago

An agricultural Extension professional, with 7 years’ experience in smallholder agricultural systems and value chains development in Sub-Saharan Africa. Robert Ochago is currently, a PhD Candidate at Wageningen and Makerere Universities in The Netherlands and Uganda, respectively. Ochago’s current research is in the area of development, management and implementation of learning strategies relevant to address wicked problems in food and agriculture.

References

- Ahmed, M. (2012). Analysis of incentives and disincentives for coffee in Uganda. Technical Notes Series, MAFAP, FAO, Rome.

- Ahuja, D., Ahuja, U. R., Singh, S., & Singh, N. (2015). Comparison of integrated pest management approaches and conventional (non-IPM) practices in late-winter-season cauliflower in Northern India. Crop Protection, 78, 232–238. doi:10.1016/j.cropro.2015.08.007

- Akter, S., Krupnik, T. J., Rossi, F., & Khanam, F. (2016). The influence of gender and product design on farmers’ preferences for weather-indexed crop insurance. Global Environmental Change, 38, 217–229. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2016.03.010

- Al Zadjali, S., Morse, S., Chenoweth, J., & Deadman, M. (2014). Factors determining pesticide use practices by farmers in the Sultanate of Oman. Science of the Total Environment, 476, 505–512. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.12.040

- Al Zadjali, S., Morse, S., Chenoweth, J., & Deadman, M. (2015). Personal safety issues related to the use of pesticides in agricultural production in the Al-Batinah region of Northern Oman. Science of the Total Environment, 502, 457–461. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.09.044

- Allahyari, M. S., Damalas, C. A., & Ebadattalab, M. (2017). Farmers’ technical knowledge about integrated pest management (IPM) in olive production. Agriculture, 7(12), 101. doi:10.3390/agriculture7120101

- Atreya, K. (2007). Pesticide use knowledge and practices: A gender differences in Nepal. Environmental Research, 104(2), 305–311. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2007.01.001

- Atreya, K., Johnsen, F. H., & Sitaula, B. K. (2012). Health and environmental costs of pesticide use in vegetable farming in Nepal. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 14(4), 477–493. doi:10.1007/s10668-011-9334-4

- Bondori, A., Bagheri, A., Damalas, C. A., & Allahyari, M. S. (2018). Use of personal protective equipment towards pesticide exposure: Farmers’ attitudes and determinants of behavior. Science of the Total Environment, 639, 1156–1163. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.05.203

- Brown, P. R., & Khamphoukeo, K. (2010). Changes in farmers’ knowledge, attitudes and practices after implementation of ecologically-based rodent management in the uplands of Lao PDR. Crop Protection, 29(6), 577–582. doi:10.1016/j.cropro.2009.12.025

- Cameron, P. (2007). Factors influencing the development of integrated pest management (IPM) in selected vegetable crops: A review. New Zealand Journal of Crop and Horticultural Science, 35(3), 365–384. doi:10.1080/01140670709510203

- Chen, R., Huang, J., & Qiao, F. (2013). Farmers’ knowledge on pest management and pesticide use in Bt cotton production in China. China Economic Review, 27, 15–24. doi:10.1016/j.chieco.2013.07.004

- Chetna, D., Vaibhav, K., Pallavi, N., & Jitendra, R. (2012). Gender differences in knowledge, attitude and practices regarding the pesticide use among farm workers a questionnaire based study. Research Journal of Pharmaceutical, Biological and Chemical Sciences, 3(3), 632–639.

- Christie, M. E., Van Houweling, E., & Zseleczky, L. (2015). Mapping gendered pest management knowledge, practices, and pesticide exposure pathways in Ghana and Mali. Agriculture and Human Values, 32(4), 761–775. doi:10.1007/s10460-015-9590-2

- Clausen, A. S., Jørs, E., Atuhaire, A., & Thomsen, J. F. (2017). Effect of integrated pest management training on Ugandan small-scale farmers. Environmental Health Insights, 11, 1178630217703391. doi:10.1177/1178630217703391

- Damalas, C. A. (2009). Understanding benefits and risks of pesticide use. Scientific Research and Essays, 4(10), 945–949.

- Damalas, C. A., & Eleftherohorinos, I. G. (2011). Pesticide exposure, safety issues, and risk assessment indicators. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 8(5), 1402–1419. doi:10.3390/ijerph8051402

- Damalas, C. A., & Hashemi, S. M. (2010). Pesticide risk perception and use of personal protective equipment among young and old cotton growers in northern Greece. Agrociencia, 44(3), 1405–3195.

- Damalas, C. A., & Khan, M. (2016). Farmers’ attitudes towards pesticide labels: Implications for personal and environmental safety. International Journal of Pest Management, 62(4), 319–325. doi:10.1080/09670874.2016.1195027

- Damalas, C. A., & Koutroubas, S. D. (2014). Determinants of farmers’ decisions on pesticide use in oriental tobacco: A survey of common practices. International Journal of Pest Management, 60(3), 224–231. doi:10.1080/09670874.2014.958767

- Damalas, C. A., & Koutroubas, S. D. (2016). Farmers’ exposure to pesticides: Toxicity types and ways of prevention. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute MDPI AG, Basel, Switzerland.

- Egonyu, J., Kucel, P., Kagezi, G., Kovach, J., Rwomushana, I., Erbaugh, M., … Kyamanywa, S. (2015). Coffea arabica variety KP423 may be resistant to the cerambycid coffee stemborer Monochamus leuconotus, but common stem treatments seem ineffective against the pest. African Entomology, 23(1), 68–74. doi:10.4001/003.023.0109

- Ehler, L. E. (2006). Integrated pest management (IPM): Definition, historical development and implementation, and the other IPM. Pest Management Science, 62(9), 787–789. doi:10.1002/ps.1247

- Erbaugh, J. M., Donnermeyer, J., Amujal, M., & Kidoido, M. (2010). Assessing the impact of farmer field school participation on IPM adoption in Uganda. Journal of International Agricultural and Extension Education, 17(3), 5–17. doi:10.5191/jiaee

- Fan, L., Niu, H., Yang, X., Qin, W., Bento, C. P., Ritsema, C. J., & Geissen, V. (2015). Factors affecting farmers’ behaviour in pesticide use: Insights from a field study in northern China. Science of the Total Environment, 537, 360–368. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.07.150

- Grovermann, C., Schreinemachers, P., & Berger, T. (2013). Quantifying pesticide overuse from farmer and societal points of view: An application to Thailand. Crop Protection, 53, 161–168. doi:10.1016/j.cropro.2013.07.013

- Hashemi, S. M., & Damalas, C. A. (2010). Farmers’ perceptions of pesticide efficacy: Reflections on the importance of pest management practices adoption. Journal of Sustainable Agriculture, 35(1), 69–85. doi:10.1080/10440046.2011.530511

- Hashemi, S. M., Rostami, R., Hashemi, M. K., & Damalas, C. A. (2012). Pesticide use and risk perceptions among farmers in southwest Iran. Human and Ecological Risk Assessment: an International Journal, 18(2), 456–470. doi:10.1080/10807039.2012.652472

- Hou, L.-K., Huang, J.-K., Wang, X.-B., Hu, R.-F., & Xue, C.-L. (2012). Farmer’s knowledge on GM technology and pesticide use: Evidence from papaya production in China. Journal of Integrative Agriculture, 11(12), 2107–2115. doi:10.1016/S2095-3119(12)60469-9

- Jallow, M. F., Awadh, D. G., Albaho, M. S., Devi, V. Y., & Thomas, B. M. (2017). Pesticide knowledge and safety practices among farm workers in Kuwait: Results of a survey. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(4), 340. doi:10.3390/ijerph14040340

- Jassogne, L., Lderach, P., & Van Asten, P. (2013). The impact of climate change on coffee in Uganda: Lessons from a case study in the Rwenzori Mountains. Oxfam Policy and Practice: Climate Change and Resilience, 9(1), 51–66.

- Jayasooriya, H., & Aheeyar, M. M. (2016). Adoption and factors affecting on adoption of integrated pest management among vegetable farmers in Sri Lanka. Procedia Food Science, 6, 208–212. doi:10.1016/j.profoo.2016.02.052

- Jin, J., Wang, W., He, R., & Gong, H. (2016). Pesticide use and risk perceptions among small-scale farmers in Anqiu County, China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(1), 29. doi:10.3390/ijerph14010029

- Jonsson, M., Raphael, I. A., Ekbom, B., Kyamanywa, S., & Karungi, J. (2015). Contrasting effects of shade level and altitude on two important coffee pests. Journal of Pest Science, 88(2), 281–287. doi:10.1007/s10340-014-0615-1

- Karunamoorthi, K., Mohammed, M., & Wassie, F. (2012). Knowledge and practices of farmers with reference to pesticide management: Implications on human health. Archives of Environmental & Occupational Health, 67(2), 109–116. doi:10.1080/19338244.2011.598891

- Kasner, E. J., Keralis, J. M., Mehler, L., Beckman, J., Bonnar‐Prado, J., Lee, S. J., … Waltz, J. (2012). Gender differences in acute pesticide‐related illnesses and injuries among farmworkers in the United States, 1998–2007. American Journal of Industrial Medicine, 55(7), 571–583. doi:10.1002/ajim.22052

- Keshavareddy, G., Nagaraj, K., Bai, S. K., & Kulkarni, L. R. (2018). Pesticides usage and handling by the tomato growers in Ramanagara District of Karnataka, India–An analysis. International Journal Current Microbiologic App Sciences, 7(4), 3312–3321. doi:10.20546/ijcmas

- Khan, M., & Damalas, C. A. (2015a). Factors preventing the adoption of alternatives to chemical pest control among Pakistani cotton farmers. International Journal of Pest Management, 61(1), 9–16. doi:10.1080/09670874.2014.984257

- Khan, M., & Damalas, C. A. (2015b). Farmers’ knowledge about common pests and pesticide safety in conventional cotton production in Pakistan. Crop Protection, 77, 45–51. doi:10.1016/j.cropro.2015.07.014

- Kim, K.-H., Kabir, E., & Jahan, S. A. (2017). Exposure to pesticides and the associated human health effects. Science of the Total Environment, 575, 525–535. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.09.009

- Knight, C. (1939). Observations on the life-history and control of white borer of coffee in Kenya. The East African Agricultural Journal, 5(1), 61–67. doi:10.1080/03670074.1939.11663925

- Kutywayo, D., Chemura, A., Kusena, W., Chidoko, P., & Mahoya, C. (2013). The impact of climate change on the potential distribution of agricultural pests: The case of the coffee white stem borer (Monochamus leuconotus P.) in Zimbabwe. PLoS One, 8(8), e73432. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0073432

- Lekei, E. E., Ngowi, A. V., & London, L. (2014). Farmers’ knowledge, practices and injuries associated with pesticide exposure in rural farming villages in Tanzania. BMC Public Health, 14(1), 389. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-14-389

- Mengistie, B. T., Mol, A. P., & Oosterveer, P. (2017). Pesticide use practices among smallholder vegetable farmers in Ethiopian Central Rift Valley. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 19(1), 301–324. doi:10.1007/s10668-015-9728-9

- Mohanty, M. K., Behera, B. K., Jena, S. K., Srikanth, S., Mogane, C., Samal, S., & Behera, A. A. (2013). Knowledge attitude and practice of pesticide use among agricultural workers in Puducherry, South India. Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine, 20(8), 1028–1031. doi:10.1016/j.jflm.2013.09.030

- Nicolopoulou-Stamati, P., Maipas, S., Kotampasi, C., Stamatis, P., & Hens, L. (2016). Chemical pesticides and human health: The urgent need for a new concept in agriculture. Frontiers in Public Health, 4, 148. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2016.00148

- Ochilo, W. N., Otipa, M., Oronje, M., Chege, F., Lingeera, E. K., Lusenaka, E., & Okonjo, E. O. (2018). Pest management practices prescribed by frontline extension workers in the smallholder agricultural subsector of Kenya. Journal of Integrated Pest Management, 9(1), 15. doi:10.1093/jipm/pmy009

- Pretty, J., & Bharucha, Z. P. (2015). Integrated pest management for sustainable intensification of agriculture in Asia and Africa. Insects, 6(1), 152–182. doi:10.3390/insects6010152

- Rahman, M. S., Norton, G. W., & Rashid, M. H.-A. (2018). Economic impacts of integrated pest management on vegetables production in Bangladesh. Crop Protection, 113, 6–14. doi:10.1016/j.cropro.2018.07.004

- Rao, G. R., Kumari, B. R., Sahrawat, K., & Wani, S. (2015). Integrated Pest Management (IPM) for reducing pesticide residues in crops and natural resources. In: Chakravarthy A. (ed). New horizons in insect science: Towards sustainable pest management (pp. 397–412). Springer, New Delhi.

- Recena, M. C. P., Caldas, E. D., Pires, D. X., & Pontes, E. R. J. (2006). Pesticides exposure in Culturama, Brazil—Knowledge, attitudes, and practices. Environmental Research, 102(2), 230–236. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2006.01.007

- Rezaei, R., Damalas, C. A., & Abdollahzadeh, G. (2018). Understanding farmers’ safety behaviour towards pesticide exposure and other occupational risks: The case of Zanjan, Iran. Science of the Total Environment, 616, 1190–1198. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.10.201

- Rijal, J. P., Regmi, R., Ghimire, R., Puri, K. D., Gyawaly, S., & Poudel, S. (2018). Farmers’ knowledge on pesticide safety and pest management practices: A case study of vegetable growers in Chitwan, Nepal. Agriculture, 8(1), 16. doi:10.3390/agriculture8010016

- Rutherford, M. A., & Phiri, N. (2006). Pests and diseases of coffee in Eastern Africa: A technical and advisory manual. Wallingford, UK: CAB International.

- Sa’ed, H. Z., Sawalha, A. F., Sweileh, W. M., Awang, R., Al-Khalil, S. I., Al-Jabi, S. W., & Bsharat, N. M. (2010). Knowledge and practices of pesticide use among farm workers in the West Bank, Palestine: Safety implications. Environmental Health and Preventive Medicine, 15(4), 252. doi:10.1007/s12199-010-0136-3

- Schreinemachers, P., Chen, H.-P., Nguyen, T. T. L., Buntong, B., Bouapao, L., Gautam, S., … Srinivasan, R. (2017). Too much to handle? Pesticide dependence of smallholder vegetable farmers in Southeast Asia. Science of the Total Environment, 593, 470–477. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.03.181

- Sharifzadeh, M. S., Damalas, C. A., & Abdollahzadeh, G. (2017). Perceived usefulness of personal protective equipment in pesticide use predicts farmers’ willingness to use it. Science of the Total Environment, 609, 517–523. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.07.125

- Souza, G. D. S., Costa, L. C. A. D., Maciel, A. C., Reis, F. D. V., & Pamplona, Y. D. A. P. (2017). Presence of pesticides in atmosphere and risk to human health: A discussion for the environmental surveillance. Ciencia & saude coletiva, 22(10), 3269–3280. doi:10.1590/1413-812320172210.18342017

- Stadlinger, N., Mmochi, A. J., Dobo, S., Gyllbäck, E., & Kumblad, L. (2011). Pesticide use among smallholder rice farmers in Tanzania. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 13(3), 641–656. doi:10.1007/s10668-010-9281-5

- Valcke, M., Bourgault, M.-H., Rochette, L., Normandin, L., Samuel, O., Belleville, D., … Phaneuf, D. (2017). Human health risk assessment on the consumption of fruits and vegetables containing residual pesticides: A cancer and non-cancer risk/benefit perspective. Environment International, 108, 63–74. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2017.07.023

- Verger, P. J., & Boobis, A. R. (2013). Reevaluate pesticides for food security and safety. Science, 341(6147), 717–718. doi:10.1126/science.1241572

- Wang, J., Chu, M., & Ma, Y. (2018). Measuring rice farmer’s pesticide overuse practice and the determinants: A statistical analysis based on data collected in Jiangsu and Anhui Provinces of China. Sustainability, 10(3), 677. doi:10.3390/su10030677

- Wang, J., Tao, J., Yang, C., Chu, M., & Lam, H. (2017). A general framework incorporating knowledge, risk perception and practices to eliminate pesticide residues in food: A structural equation modelling analysis based on survey data of 986 Chinese farmers. Food Control, 80, 143–150. doi:10.1016/j.foodcont.2017.05.003

- Wang, W., Jin, J., He, R., & Gong, H. (2017). Gender differences in pesticide use knowledge, risk awareness and practices in Chinese farmers. Science of the Total Environment, 590, 22–28. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.03.053

- Yang, X., Wang, F., Meng, L., Zhang, W., Fan, L., Geissen, V., & Ritsema, C. J. (2014). Farmer and retailer knowledge and awareness of the risks from pesticide use: A case study in the Wei River catchment, China. Science of the Total Environment, 497, 172–179. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.07.118

- Yuantari, M. G., Van Gestel, C. A., Van Straalen, N. M., Widianarko, B., Sunoko, H. R., & Shobib, M. N. (2015). Knowledge, attitude, and practice of Indonesian farmers regarding the use of personal protective equipment against pesticide exposure. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment, 187(3), 142. doi:10.1007/s10661-015-4371-3

- Zhang, C., Guanming, S., Shen, J., & Hu, R.-F. (2015). Productivity effect and overuse of pesticide in crop production in China. Journal of Integrative Agriculture, 14(9), 1903–1910. doi:10.1016/S2095-3119(15)61056-5

Additional materials

Table A1. Farmers’ description of the coffee stem borer infestation

Table A2. Description/Measurement of the knowledge, attitudes and practices variables

Table A3. Advantages and disadvantages of the CSB IPM practices (reasons for not using individual CSB IPM practices, N (men = 71, women = 55)