Abstract

Sacred natural sites are culturally and environmentally significant areas to be researched in different cultural contexts. Hence, this research was conducted to investigate the indigenous mechanisms of preserving sacred natural sites in Guji Oromo, southern Ethiopia. Particularly, the study was conducted in Guji zone, Adoolaa Reeddee and Annaa Sorraa districts. Data were produced by interview (in-depth and key informants’ interview), focus group discussion and transect walk. The data analysis was made qualitatively. The findings of the study demonstrate customary laws and oral declaration, taboos, customary punishment and social banishment are used as indigenous mechanisms used to preserve sacred natural sites in the study area.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

This research reports on the indigenous mechanisms of preserving sacred natural sites of Guji Oromo in Ethiopia emphasizing the role of the indigenous institution of Oromo community known as Gadaa system in protection of natural places set aside for cultural purposes. The research is significant in that it contributes to global production of knowledge about the worldview of Guji Oromo community pertaining to traditionally and mythically sacralized natural sites and yearlong traditions of maintaining and sustaining the sites. Hence, the findings of the study might be of interests to academics, preservationists of sacred natural sites, policymakers and local community in general whose traditional practices are interconnected with the physical environment in general and sacred natural sites in particular.

Competing Interests

The author declares no competing interests.

1. Introduction

Local communities have conserved sacred natural sites in their land for millennia. In long-centuries endeavor of conserving sacred natural sites, various people of the globe have been inspired by the belief system, cosmos, praxis and myth that deep-implanted in their culture. The sacredness of natural sites is sprouted from yearlong human–environmental interaction and embedment of culture in the environmental features. As indicated by the scholars, the sacred natural site refers to socially reserved, holy or venerated areas that are connected with local people traditions, worship, remembrance and belief systems (Oviedo, Jeanrenaud, & Otegui, Citation2005; Verschuuren, Wild, McNeely, & Oviedo, Citation2010). It is undeniably the oldest protected areas of the earth by local communities even long before the introduction of formal conservation programs (Verschuuren, Citation2010; Wild, McLeod and Valentine, Citation2008). On the other hand, sacred natural sites are globally significant due to dual functions they offer to local culture and sustain biodiversities in the environment (Wild, McLeod, and Valentine, Citation2008).

These sites embrace biological and cultural diversities and serve as biocultural diversity hotspot (Maffi & Woodley, Citation2012). In fact, in terms of their importance for humans life, sacred natural sites are sources of medicinal plants, centers for various rituals whereby local people address their sociocultural and psychological needs and to sustain biodiversities and cultural identity of the people (Doffana, Citation2017; Dudley, Higgins-Zogib, & Mansourian, Citation2009; Ormsby & Bhagwat, Citation2010; Wild et al., Citation2008). The sacred natural sites such as Wonsho of Sidama and Caatoo of Horro Guduru Wollega are socially conserved and respected sites which could have sociocultural and environmental importance in Ethiopia (Doffana, Citation2014, Citation2017; Lemessa, Citation2014). In Guji land, there are also many sacred natural areas identified for different traditional rituals since time immemorial (Gemeda, Citation2018).

Even though sacred natural sites are found in different communities and important in multidimensional for humans social life, currently they have been increasingly threatened in many parts of the world due to anthropogenic pressures (Dudley et al., Citation2009; Wild et al., 2008). The ubiquitous anthropogenic pressure affects the environment in general and sacred natural sites in particular. Hence, the empirical investigation and proper documentation of indigenous knowledge and practices associated with sacred natural sites are very essential. In Guji Oromo context, the previously conducted studies witnessed that sacred natural sites are interlinked with local traditions and serve as the vital physical environment in the Gada system (Gemeda, Citation2018; Hinnant, Citation1977; Jemjem & Dhadacha, Citation2011; Taddesse, Citation1995). However, the indigenous mechanisms of preserving sacred natural sites, which operate in Guji Oromo since the ancient time, are not addressed in these previous studies. Obviously, in this era of rapid and ubiquitous sociocultural changes, which mainly emanated from anthropogenic pressures, the investigation of indigenous mechanisms of protecting sacred natural sites is an overlooked aspect in the researches. Specifically, the typical indigenous mechanisms of preserving sacred natural sites, how and why these mechanisms are functioning among Guji Oromo need research intervention. Therefore, this article tries to investigate the existing indigenous mechanisms of preserving sacred natural sites, how and why the mechanisms have been practiced in Guji Oromo in Anna Sorra and Adola districts, Guji Zone.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Description of the study area

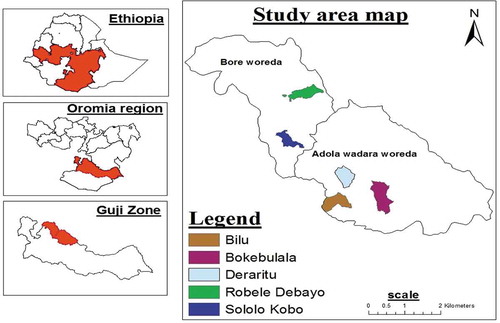

This study was conducted in two neighboring districts of Guji zone- Adoolaa and Annaa Sorraa. Guji zone is among 20 zones of Oromia national regional state that borders on the East Bale zone, at the west direction, the west Guji zone, on the south Borana zone and on the north the Sidama and Gedeo zones of South Nations Nationalities and People of Ethiopia region. Currently, Guji Zone has 14 districts and three town municipalities. The total land area of the zone is 18,577 square kilometers (Teshome, Citation2016). Based on the census conducted in 2007, the total population of Guji Zone was 1, 389, 800, of which 702, 580 are men and 687, 220 women with an area of 18,577.05 square kilometers and a population density of 74.81 persons/km2 (PCCFDRE, Citation2007). Guji land is characterized by three ecological zones, Baddaa (high altitude), Badda-daree (middle altitude) and Gammoojjii (semiarid land) (Debsu, Citation2009), but Adoola and Annaa Sorraa districts are found at middle altitude and highland ecological zones. The rainfall pattern is bimodal and the major season (Ganna) extends from March to May and the minor season (Hageyya) extends from September and November.

Guji Oromo is composed of three phratries known as Uraagaa, Maattii and Hookkuu. According to Guji legend, Gujo the founding father of Guji had three sons whose names were Uraago, Maattoo and Hookku. The three phratries of Guji are named after the names of three Gujo sons. Guji is known by indigenous institution-Gada system that has been developed since the time immemorial. There is no exact and precise historical record regarding when and how the Gada system was begun by the community descendants.

However, Gada system is a comprehensive organization embodying sociocultural, economic and political aspects of Oromo population at large and Guji society in particular (Debsu, Citation2009; Jalata & Schaffer, Citation2013; Jeylan, Citation2006; Legesse, Citation1973). This institution represents the whole traditional way and worldview of the Oromo community (Legesse, Citation1973). Nevertheless, the diachronic analysis of Gada system implies, even though the institution formerly strong in all dimensions, currently it has been reduced to sociocultural rituals than political and military roles used to be played in the past (Debsu, Citation2009). Presently, in spite of formidable changes, Gada system is relatively intact among Guji Oromo and it has been serving as a customary governing system. The sociocultural power of the system is transmitted peacefully and ritually from one party (Baallii) to another in the sacred natural sites. There are five parties (not like political parties, but culturally organized) in the Gada system of Guji that handover sociopolitical power in every eight years. These five parties are Halchiisaa, Dhallana, Muudana, Roobale and Harmuufaa. The term of office for one party is eight years as per the Gada system principle.

Geographically, Adoolaa and Annaa Sorraa areas have significant implications in the history and culture of Guji Oromo, because Adoolaa is believed to be a center of origin for Guji, whereas Annaa Sorraa district, particularly Me’e Bokko, has been serving as a center for Gada system of Guji Oromo (Jemjem & Dhadacha, Citation2011). These two districts are found on the main asphalt road stretches from the capital city of the country – Addis Ababa to Nagele zonal town of Guji zone.

2.2. Methodological approach

This study employed a qualitative approach as well as qualitative descriptive design. Data were produced through in-depth interview, key informant interview, focus group discussion and transect walk. In-depth interview was made with community elders, practitioners of the Gada system and experts of Culture and Tourism offices of Guji zone and two aforementioned districts. The focus group discussions were made with practitioners of the Gada system and community elders in Adoola Reedde and Annaa Sorraa districts. The points of discussion were forwarded by the support of moderators, and discussants raised existing experiences of traditional preservation of sacred natural sites in the discussion. Another form of data collection technique used in the study was transecting walk in which I made an intensive combination of observation and interview with local community elders. This had been used to practically observe the sacred natural sites and existing situation of them with the help of local community elders. Data collected by the abovementioned techniques were analyzed through the qualitative description in general and thematical analysis in particular. Similarly, data presentation is conducted qualitatively through the narration of quoted and paraphrased statements.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Conception of sacred natural sites in Guji

Before delving into investigating what sort of and how the indigenous system of preserving sacred natural sites in the area is functioning, it is important to introduce the local conception of sacred natural sites from Guji community point of view. The conception of sacred natural sites in the community is highly linked with the tradition of land ordaining that was developed long century ago by Guji descendants. Gada system and sacred natural sites are two inseparable entities in Oromo worldview at large and Guji sacred cosmology in particular. Consequently, questioning how Guji Oromo of the study area has mythically conceptualized sacred natural site itself is the core idea in this article. From Guji community vantage point, sacred natural sites are Woyyuu (sacred) place and locally known as Ardaalee Jilaa or lafa Woyyuu. In the community, sacred natural sites are places dedicated to rituals of Gada system and adoring of Waaqaa (God). Based on this dedication, sacred natural sites of Guji Oromo are termed as sacred shrines and/or Gada shrines which are interchangeably used in this article. Particularly, as indicated by one of the elderly informants from the study area, sacred natural sites are places where prayer and thanksgiving rituals are offered to God in the organized and culturally systematized approach (In-depth interview made with Dabbasoo Waaree at Adoolaa, February 2018). Another key informant from Me’ee Bokkoo area added, “Ardaan Jilaa lafa woyyuu Gujiin, waaqa woliin itti haasawu”, meaning sacred shrine is a sacred place where Guji communicate with God and propitiate him. When explaining how sacred shrines have a significant position in Guji culture, the informants underlined that “Ardaan Jilaa bannaan aadaan Gujiille badde” means if sacred shrines are destroyed, the Guji tradition will be lost. This implies that there is an inextricable interconnection between culture and sacred natural sites in the view of Guji Oromo. This inextricability and embedment of sacred natural sites with Guji sociocultural tradition are profoundly found in traditional prayer made before and after formal social gathering in either public office or anywhere else. In the session of supplicating God, Abbaa GadasFootnote1 and other community elders list down some names of sacred shrines in Guji land. In this traditional prayer, which is locally known as “eebbifachuu” for the specific event, Gada leaders and community elders would enumerate names of some sacred natural sites saying:

‘Oh God of Me’e Bokko, God of Dibbee Dhugoo, God of Dhugoo Dooyaa, God of Daamaa and Daarraa, God of Adoolaa, God of Odaa Doolaa, God of Ilaalaa…. listen to our entreaty and please respond to our call, block inauspicious omen and potential danger from us, give us peace and make us safe in our life span…’.

The elders list down only a few sacred natural sites out of 376 sites in the Guji land during calling upon God for the successfulness of the specific event. This shows that the sacred natural sites of Guji Oromo are highly interconnected with and inseparable from daily cultural practices. In general, sacred shrines are places dedicated to various rituals and other cultural events in the Gada system and the place where praying of God for sustainable peace, health and wealth.

3.1.1. Customary law and oral declaration

Traditionally, the customary laws that regulate the overall sociocultural life of Guji people are formulated in Me’e Bokko sacred shrine every eight years. Me’e Bokko is a sacred natural site, which has a special position in the Guji Gada system and the place where customary laws are formulated and Gada power transition is ceremonially performed. The customary laws proclaimed at this place include sociocultural regulations, environmental issues and wild animals protection. The formulation and announcement of customary laws are performed according to principles and regulation of the Gada system. As stated by Guji elders, nine YuubaasFootnote2 that comprised of Baatuu, Yuuba diqqaa and Yuuba guddaa from three Guji phratries, namely Uraagaa, Maattii and Hookkuu, come together and make the customary laws (FGD, February 21/2018 at Adoola Woyyuu). This means each three phratries of Guji community are composed of Baatuu, Yuuba diqqaa and Yuuba guddaa that can be counted as nine when gathered from three phratries. These nine Yuubaas are believed to have good knowledge and rich experiences in the Gada system and they are legitimate bodies given a responsibility to formulate laws and make an oral declaration. Yuubaas are given not only responsibility to make customary laws but also they are assigned to amend or omit some portion of the laws as much as demand arises.

These customary laws play a significant role in preserving sacred natural sites. When expounding the role of customary laws in preserving sacred shrines, one key informant underscored, “ardaan jilaa seera Gada’atiin bula” means sacred shrines are managed by Gada customary laws (In-depth interview made at Damboobii, February 2018). These customary laws are publically announced through an oral declaration at Me’e Bokko after being made or amended by Yuubaas. As noted by research participants, customary law clarifies the mandate and responsibility of all Guji people in general and active practitioners of the Gada system in particular. At a very broader level, all Gujis are mandated to keep, respect and preserve sacred shrines. This mandate is basically supported and reinforced by customary laws and oral declaration. The research participants explained that Yuubaas make oral declaration centering on customary laws, calling names of three each phratries of Guji according to their seniority rank to give them mandate of preservation, starting from Uraaaga, the first son of Gujo,Footnote3 and then Maattii and Hookku in their descending order. Yuubas declare the laws of preserving sacred shrines as the following turn by turn:

Uraagaa dhage’i (Uraagaa, listen to declaration)

Maattii dhage’i (Maattii, listen to declaration)

Hookkuu dhage’i (Hookkuu, listen to declaration)

Diqqaa dhage’i Guddaa dhage’i (The younger and elders, listen to declaration)

Gumii baate dhage’i (The assembled people, listen to declaration)

Gujii baye dhage’i (Guji assemblage, listen to declaration)

Ardaan jilaa woyyu’u (Ardaa Jilaa is sacred shrines)

Hin kunuunfama, hin eegama, hin kabajama (it should be preserved, kept and respected)

This oral declaration indicates that even though Yuubaas are mandated to formulate overall customary laws and make declaration pertaining to the protection of sacred shrines, the responsibility of preserving, keeping and sustaining the sites is given to the entire Guji community regardless of the territorial difference in settlement pattern and phratry. Guji elders denoted that customary laws of preserving Gada shrines are publically declared to meet the following targets. First, it is declared to indoctrinate the respect, reverence and cultural position of sacred natural sites in people’s daily way of life. Second, it is declared to expound the potential danger that may befall individuals who violate customary laws of Gada shrines, as dictated in local myths and belief system. The existing belief system speculates that a person who even misbehaves in Gada shrine and violates the customary law of its protection would no longer live or would be unsuccessful in his/her life. Third, the customary law of preserving Gada shrines is announced to acquaint the governmental, nongovernmental and religious organizations not to intervene and manipulate the customary laws, rather invite them for collaborating in backing up local customs and traditions. Hence, customary laws and related oral declaration serve the central role as indigenous mechanisms of preserving sacred shrines. Generally, customary laws of preserving Gada shrines have predominantly embraced cultural prohibition, assignment of responsible bodies and customary punishment and social banishment.

3.1.2. Cultural prohibitions

Cultural prohibition refers to taboos whereby some actions and activities are strictly forbidden by local traditions. This taboo strongly supports the preservation of sacred natural sites. In the study area, cultural prohibitions are emanated from customary laws of the Gada system, local myths and belief system. According to Guji elders, actions and activities enumerated below are firmly forbidden by local taboos of the people not to perform in sacred shrines. Among these activities and actions farming, settlement, cutting down trees and degrading forests, killing or thrusting wild animals, having sexual intercourse, burning, spitting, burying dead body, quarreling with someone, crying for dead person, defecation and urinating in sacred Gada shrines are common (FGD, February 15 and 21/2018 at Daraartuu).

As far as cultural prohibition pertaining to sacred shrines is part of customary laws, Yuubaa declares it every eight years at Me’e Bokko as follows:

Ardaan jilaa woyyuu, santi seera (Ardaa Jilaa is a sacred shrine that is a law)

Hin tuqamuu, santi seera (It should not be damaged by no means, that is a law)

Tuqan yakkaa, santi seera (If damaged, it is a customary rule violation that is a law)

Qodha qabaa, santi seera (If it is destroyed, there should be punishment that is a law)

Qodhi kormaa goronsa, santi seera (The punishment for moderate detriment is a payment of bull and heifer, that is a law)

Yoo kanan hin adabatin saddeetaa, santi seera (If a person acutely harms the shrines, he/she should be punished paying eight cattle that is a law).

When declaring about prohibitions, Yuubaa emphasize the enumeration of those prohibitions and potential punishment to be implemented in case of violation. The violation of these cultural prohibitions is locally perceived as not only breaching the customary law of Gada system but also as defying supernatural power (Waaqaa’s) covenant which is embedded in myths and local belief system.

Locally, the prohibited actions are broadly classified into two as deconsecrating actions and detrimental activities. Deconsecrating actions are killing or thrusting wild animals, having sexual intercourse, spitting, burying a dead body, quarreling with another person, crying for a dead person, defecation and urinating in the sacred shrines. These actions are prohibited not to be performed in sacred shrines because they could desecrate the sacred features of the shrines as perceived in myths and belief systems of the study community. According to the informants, a person who deconsecrated sacred shrines could be punished by God through sudden death, accidents, the death of children, insanity and loss of wealth and health.

There is a belief system state, “badiin nama dhokatte waaqaa hin dhokattu”, means the violation act, which is invisible to man is visible to Waaqaa (God). This means that the local people believe that sacred shrines are jointly managed by customary laws of Gada system and rule of Waaqaa so that Waaqaa always oversees the existing situation of sacred shrines. This indicates that customary laws and local belief systems formed solid cultural prohibitions that underpin preservation of sacred natural sites.

3.1.3. Responsible body and managing structure

Even though the entire Gujis are vested responsibility to preserve sacred shrines at a broader context, there are mandated personages from the structure of the Gada system to govern the protection endeavor the sites. In the Gada system, Jadhaabaa, HayyuuFootnote4 and Abbaa Gada are the mandated personages at front-line duty among Gada councils to manage overall issues of the Gada shrines (in-depth interview made at Biluu in February 2018). As noted by informants, whenever somebody violates cultural prohibitions and customary laws by harming sacred shrines, Jadhaabaas bring the violatorFootnote5 to Abbaa Gada or Hayyuu based on their proximity to the harmed shrines. In the case when the issue of destroyed sacred shrines is reported to Abbaa Gadaa, he commands Hayyuus to deal with the reported case and pass the right decision. On the other hand, when Abbaa Gada is not available in the vicinity of harmed shrines, Jadhaabaa can bring the case to Hayyuus who inhabit environs of harmed shrines. Structurally, Abba Gada is a prime body, Hayyuu are customary decision makers and Jadhaabaas have police officers role in the system. The following figure demonstrates the hierarchical structure of Gada councils assigned to manage sacred shrines in the Gad system.

These three members of the Gada system central committee have their own specific role in the management of Gada shrines. For instance, Abbaa Gada’s role is taking the case of destroyed sacred shrines that would be eventually reported to Hayyuu for further deal and customary decision. He is head of Gada councils and holds the sociocultural power in the system to oversee all activities of preserving and managing sacred shrines. Locally, Abba Gada is believed to be a father of all nations and steward of natural resources. Hayyuus are also mandated to investigate the case, which is given them by Abbaa Gada or sometimes by Jadhaabaa so that they pass customary decision over the issues of sacred shrines. They are customary judges that critically scrutinize different social cases from the vantage point of Gada rule and pass decision over the controversial issue. Abbaa Gada does not pass decision over the case of sacred shrines by himself, but as per the tradition of his headship in the Gada system, he enforces the decision given by Hayyuu to keep the sustainability of the shrines. This indicates that Abbaa Gada leads every customary system in the community through participatory approach as per the Gada system, but not like an authoritative dictatorship that decides everything based on his interest. Jadhaabaas have also the role of keeping and managing Gada shrines and bring a person who violates the customary rules of the sacred shrines to the concerned bodies – most probably to Abba Gada and Hayyuu.

Even though the abovementioned three structures of Gada councils are primarily responsible at the front line to manage and preserve sacred shrines, at a bit broader scope, the other structures of the Gada system are functioning as prime guardians of sacred shrines. These include Jalkeya, Faga, Waamura and Torbii. The members in these structures are active in the system and have been working as members of general central committees of the Gada system that administer overall aspects and take necessary administrative measures. Besides the primary endeavors of Abba Gada, Hayyuu and Jadhaabaa to preserve Gada shrines, the direct or indirect support of the rest of structures in the Gada system have a significant role in the preservation of sacred shrine. For instance, one of the Fagas in Gada council was assigned to keep the Gombobaa sacred shrine from local people intervention in the study area. This indicates that even though some technical activities such as passing decision over the issue of destroyed sacred shrines and implementation of customary punishment are limited to Abbaa Gada, Hayyuu and Jadhaabaa, the other councils in the Gada system are responsible to closely and collaboratively manage the shrines.

Hierarchically, Abbaa Gada is head, Faga is a mentor of Abbaa Gada and ritual head, Jalkeya acts as a vice head or protocol officer, Hayyuu acts as a decision-maker and the customary judge, Waamura as facilitator body for the decision-making process and Jadhaaba act as peacekeeping or security force in the Gada structure. Generally, these structures work together in an interrelated approach to preserve sacred natural sites in the Guji community.

3.1.4. Power decentralization

Traditionally, there are practices of decentralizing power in the Gada system to manage and preserve sacred shrines. This indigenous system of decentralizing power to closely preserve sacred shrines is locally known as Hagaanaa baqassuu, meaning sharing mystical power to Gada councils in different localities so that they strongly protect the condition of sacred shrines in a specific locality.

In power decentralization process, Abbaa Gada usually assigns Gadaa balbalaa,Footnote6 Hayyuu Dudda, Jadhaaba and Worra dibbeeFootnote7 in different places so that they manage the overall phenomena of sacred shrines. Gada Balbalaa is a member of Gada councils who lives nearby specific location of sacred shrines, and for whom Abbaa Gada shares power so that he acts on behalf of Abbaa Gada. Gadaa Balbalas are traditionally delegated body who are given the power to be Gada leaders (traditional leaders) and responsible to preserve sacred shrines in particular and lead every social tradition of Guji at large. Unlike Gada Balbalaas who are given the power to act like Abbaa Gadaa in their vicinity, the Hayyuu duddaa are members of Gada council mandated to pass decision over the case reported to them by Gada Balbala and/or Jadhaabaa. Basically, they are customary decision-makers whose decision is very limited to the specific geographical area. These decision-maker bodies are responsible for a specific location in which they are delegated and keep sacred shrines from human-induced detriment. After delegated by Abba Gada in the power decentralization process, Gadaa balbalaas assign another group known as Hayyuu Duddaa – customary decision-makers whose power exercise is limited to restricted ideal demarcation.

Then, Hayyuu Dudda delegate and share responsibility to Worra dibbee, meaning members of a specific neighborhood or village so that they protect sacred shrines. The territorial scope of Gada Balbalaa and Hayyu Duddaa is broader than that of Worra Dibbee, but all are given the equal mandate to protect sacred shrines in their territory. As early discussed in this article, Jadhaabaas also play an ample role in these structures as police officers by actively involving in preserving sacred shrines and bring the destroyers of the sites to Gada Balbala or Hayyu Dudda.

As stated by informants, traditional power decentralization is commonly and actively practiced in Uraagaa phratry of Guji Oromo, because, comparatively, some sacred shrines of Uraagaa group where they perform traditional rituals are far away from Uraagaa settlement and found in Hookkuu and Maattii territories. For instance, the Gada councils of Uraagaa from West Guji zone, Bule Horaa, Dudda Daawwa and Melka Sooddaa area go to Daraartuu sacred shrine nearby Adoolaa woyyuu town to perform rituals in Guji zone. This means they move more than 200 km to arrive at some sacred shrines where rituals are performed. Particularly, Daraartuu shrine of Uraagaa group where various sacred trees are found is an apparent example of places that Uraaga phratry manages sacred shrines through power decentralization approach. The research participants noted that this power decentralization enables and empowers the individuals to keep and preserve sacred natural sites.

3.1.5. Punishment and social banishment

Punishment and social banishment are vital parts of customary laws and local belief system that govern sacred shrines in Guji Oromo. There is no clear-cut boundary between punishment and banishment practices in Guji context since both are interrelated in multiple ways. The punishment imposed when a person violates customary punishment among Guji Oromo is classified into three and composes of the punishment by bull and heifer (kormaafi goronsa), punishment by paying eight cattle (saddeetaa) and punishment by excommunicating the violator (shammagga muruu) based on the degree of violation in the study area.

3.1.5.1. Punishment by bull and heifer

As noted by research participants, when a person destroys the sacred shrine by constructing a house, cutting down a tree and farming its land, he/she would be punished by paying bull and heifer. The cases categorized under this punishment can be moderate damage and violation of Gada shrines. Procedurally, Jadhaaba reports the case of destroyed sacred shrines to Hayyuu and Abba Gada based on their closeness to an area. Then, the detriment is thoroughlyinvestigated and necessary punishment is passed by Hayyuu. Hayyuus do not pass decision without properly investigating the detriment of the shrines in detail and identifying the degree of damage. Then, if the damage to the shrine is moderate, Hayyuus would pass decision over the destroyer of the shrines so that he/she pays a bull and heifer to Abba Gada and Gada council. After Hayyuu investigates the case and gives a decision, the Jadhaabaa would be sent to the home of the destroyer to take over a bull and heifer. As underlined by the informants, a bull taken in this way from the violator is slaughtered to Gada councils who take part in the decision-making process and the heifer is then given to Abbaa Gada. According to Guji tradition, after the implementation of the customary decision, which dictates payment of a bull and heifer, Abbaa Gada and other Gada councils supplicating Waaqaa not to again punish the destroyer by sudden death, accident and loss of health and wealth. This process is known as reconciling the destroyer of sacred shrines with Waaqaa because in Gada system of Guji Oromo, a person, who destroys the sacred shrine violates not only customary law of Gada system but also the rule of Waaqaa. The reconciliation session is conducted through traditional prayer after customary punishment is effective. This means Abbaa Gada supplicates Waaqaa not to punish the destroyer of sacred shrines who is once punished by paying a bull and heifer.

A person on whom the decision is imposed due to destroying sacred shrines could not disregard the customary punishment, because unlike the punishment in the formal court system, this decision has dual purposes. This dualism embodies, first, punishing the violators and warning them not to repeat the same violation; second, it aims at reconciling the violator with Waaqa through traditional supplication. As explained by informants, if a person who destroyed sacred shrines is not punished through customary rule or fails to accept the customary decision, Waaqaa would punish him/her by death or accidents as per the local belief system.

Similarly, the informants stated that the punishment of a person who violates the rule of sacred shrines is twofold; the first one emanates from Gada customary law and second is from waaqaa. Even though myths and belief system in Gada system have been eroded since the recent past decades, a person who harmed sacred shrine does not repudiate to accept the punishment, which is considered to be means of escaping from the wrath of waaqaa, because this is not the only penalty but also reconciliation process through which the violator gets mercy from waaqaa who is believed to give the places power of sacredness. As underlined by informants, after the customary punishment is executed, Hayyuus and other Gada councils make a traditional prayer to the violator saying “kuunnoo lafa sitta araarsinee, waaqa sitta araarsinee deebitee hin yakkin“, meaning ‘behold, we reconciled you with earth and God; please do not repeat the same violation’. This explanation demonstrates that the punishment aim is not only to penalize but also to reconcile a person with a supernatural deity as the local tradition. Concerning the inextricability of customary law and supernatural force punishment, one of former Abba Gada narrated the following:

It was some years ago when I was Abbaa Gadaa of Muudana party. As we usually did, we come to Gombobaaa sacred site to perform naming and circumcision rituals. At the first day of our arrival, we met someone who inhabited in the sacred site. Then I deployed my Jadhaabaa and they brought me the man. Next, I ordered my Hayyuus to deal with the case and pass decision. Then, they investigated the case and informed the man to pay Kormaa and a GoronsaFootnote8 due to the moderate condition of violation. Unfortunately, the man had no cattle to pay for the punishment. Therefore, we reduced the payment to a billy goat instead of a bull and heifer; because a bull does not always denote male cattle but also a billy goat. After punishing him by taking over a billy goat, we ordered the man to leave the area soon. Then the man promised to leave the territory of sacred shrine rapidly. Nevertheless, the man did not leave the area as per the order of Gada council and because of his stay in the sacred sites; the wrath of God had taken away his child by death.

This shows that customary punishment and local belief system concerning sacred shrines are highly interlinked. Hence, this linkage underpins the preservation of sacred natural sites on one hand or another.

3.1.5.2. Punishment by saddeeta

Guji elders explained that a person who severely harmed sacred shrines would be punished by “saddeeta” meaning payment of eight cattle, eight cattle hide, eight food’s container material called Qorii (wooden bowl) and additional eight cattle to be slaughtered. Conceptually, saddeeta refers to a serious punishment next to the punishment of bull and heifer in Gada system whereby destroyers of sacred shrines are ordered to pay the demanded payment, which is “eight” in numerical value. Basically, number eight has special meaning in Gada system and more profoundly it indicates the developmental stage of Gadaa grade which enters into new and next status every eight years on one hand and rotation of Gada power transition system in every eight years on the other. This means one of the five Baalliis (Muudana, Dhallana, Harmuufa, Roobalee, and Halchiisa) term of office is eight years and there is rotation of traditional power transition in Guji Oromo Gada system.

Saddeetaa, which has multicultural meanings and implications, is one of the customary ways of protecting the damage to sacred natural sites. Particularly, as indicated by the informants, cutting down HaaganaaFootnote9 trees in the shrine, destroying the whole sacred shrine deliberately by fire or distracting all the trees and forest in the shrine could lead to the punishment of saddeetaa. One of the Yuubaa noted that saddeetaa punishment in most cases imposed on the group violation than the individual detriment, because paying eight cattle at one time could be difficult to the individual person. Another breach that falls under the saddeetaa punishment is severe damage made on major sacred shrines like.

On the other hand, the eight slaughtered cattle from destroyers of sacred shrines because of acute shrine’s damage could be shared and eaten by all Gada councils who took part in the punishment procedure. The rest eight wooden bowls, eight cattle and eight hides are given to Abbaa Gada and his council. As stated by informants, this form of punishment was active when there had been a huge number of cattle owned by a single individual particularly before the advent and expansion of imported religions.

3.1.6. Excommunication

Another form of traditional punishment denoted by the informants is excommunication or social banishment. This banishment system is locally known as Shammaga muruu meaning excommunicating the destroyer of sacred shrines from every social life of the community. As explained by informants, this form of social banishment is given finally when a person or a group of people in neighborhood acutely and repeatedly harms the sacred shrines negligently. From this point of view, breaching the customary law of the sacred shrines results in the punishment and the final level of punishment would be social banishment whereby the destroyers of sacred shrines are excommunicated by local people. Social exclusion as a result of customary punishment is very serious in the Guji Oromo context. Once a person is excommunicated from the social life of local people, he/she is deprived of every social life and everyone is warned not to salute, eat and drink, participate funeral ceremony and share any social relationship with them. Starting from the date of exclusion punishment, the local people do not consider the violator as Guji clan member. This form of social banishment to the extent of excluding violator from social life is announced by Abba Gada and Gada councils. Generally, these forms of customary punishment and social banishment, which are emanated from customary law and local belief system, have been serving as indigenous mechanisms of preserving sacred shrines in Guji Oromo.

4. Discussion

In the Guji Oromo Gada system, sacred natural sites have special cultural recognition and implication which is deep-rooted in the life of the community. It is even impossible to separate Gada system from sacred natural sites in Guji context because Gada system is an indigenous institution which is highly imbued with sacred natural sites in multidimensional (Desalegn, Citation2013; Gemeda, Citation2018; Jemjem & Dhadacha, Citation2011; Taddesse, Citation1995). These sacred natural sites are preserved and managed by indigenous mechanisms since the time immemorial in Guji Oromo. Specifically, the findings of this study witness, customary laws and oral declaration, taboos, punishment and social banishment are common traditional mechanisms whereby Guji preserve sacred natural sites for a long period. These indigenous mechanisms covertly hold the philosophical understanding of Guji about the interconnection among nature, culture and supernatural power in sacred natural sites. This philosophical understanding entails the mutualistic view of the community about the linkage of nature and culture. Hence, the sacred shrines are perceived as the central point where cultural and supernatural practices take place in an intermingled manner. This means the site is physically visible landrace, culturally revered and supernaturally dedicated to some mystical practices. When explaining the local value of sacred natural sites, Taddesse (Citation1995) stated that sacred shrines are revered like Churches of Christians and Mosques of Islam among Guji Oromo. Even though the sacred natural sites are the natural environment, Guji perceive them as shrines where they perform different traditional and mystical rituals. As a result, Guji give the special position to sacred natural sites in their Gada system, because the system is, be it directly or indirectly connected to the sacred natural sites. The Gada power transition, formulation of customary laws and oral declaration, libation and supplication are common traditional practices performed at sacred natural sites. Hence, Guji preserve sacred shrines, which have special recognition in their sociocultural life.

The customary laws and oral declaration are local mechanisms mainly used to preserve sacred shrines in the study area. Customary laws primarily serve multiple functions in different communities of the world. For instance, customary law provides functions like settling conflicts, conserve natural resources and allocate land and water resources in different societal settings (Ayelew, Citation2012; Endalkachew, Citation2015; Katrina, Citation2011; Verschuuren et al., Citation2010). It is also deemed as indigenous laws of the people. This notion of perceiving customary law as indigenous law and implementing it to different sociocultural and political context is also a common phenomenon in various African communities (Katrina, Citation2011). In the Ethiopian context, Endalkachew (Citation2015) stated that customary law is a central element in the preservation of territories and natural resources. Specifically, in Guji context, Teshome (Citation2016) discussed that local customary practices have a lion’s share in the rangeland management system. These comparative studies demonstrate that customary laws play a crucial role in Ethiopia at large and Guji in particular. However, the findings of this study indicate that customary law is particularly a decisive culturally structured and solidified system of preserving sacred natural sites. This customary law indirectly provides the humans and environmental functions by protecting biodiversity in the physical environment and cultural practices performed in the sites. Because it (customary law) underpins the protection of every sacred natural sites. Correspondingly, customary practices behind sacred natural sites are essential in terms of environmental protection and sustaining cultural practices (Samanthae & Cathy, Citation2003). Endalkachew (Citation2015) and Katrina (Citation2011) also stated that customary laws are remarkable elements in biodiversity conservation. Hence, customary laws, which serve as vital mechanisms of preserving sacred natural sites in the study area, play an indispensable role in environmental and cultural protection. Generally, customary law in the study area preserves not only sacred shrines but every natural feature like trees, bushes, wild animals and forests.

Another mechanism of preserving sacred natural sites is taboo. The taboos, which are emanated from customary laws, myths and local belief system, underpin the preservation of the sacred shrines in Guji Oromo. As indicated in the data presentation, some actions and activities are strictly forbidden by cultural prohibitions from sacred shrines. Similarly, the study conducted in West Africa demonstrated that it is prohibited everywhere to cultivate sacred natural sites, to cut down the trees, to collect any part of them, even dead wood, to burn the vegetation, to harm or kill any animal found there or to take some earth or any stone from the place (Anne, Citation2011). This prohibition is evident in different indigenous communities and helps to realize the sustainability of sacred natural sites. Another comparative study conducted among Sidama of Ethiopia shows that prohibitions regarding sacred natural sites are mainly emanated from the belief system that these sites and trees represent ancestors (Doffana, Citation2014). Nevertheless, the taboos of sacred natural sites in Guji Oromo emanate from customary laws of the Gada system and local beliefs, which dictate the presidency of God over the sites. Similarly, the local belief system that associates sacred sites with supernatural power is a common practice among different communities across space and through the time (Doffana, Citation2014; Kandari, Bisht, Bhardwaj, & Thakur, Citation2014; Verschuuren et al., Citation2010).

The other mechanisms of preserving sacred shrines are customary punishment and social banishment. The procedures of punishment are specified in the customary laws. Moreover, as various global experience of traditionally preserved sacred natural sites indicate, fear of supernatural beings (Kandari et al., Citation2014), beliefs in supernatural power as presiding over sacred natural sites (Nath & Gam, Citation2012) and dedication of places or objects to deities (Negi, Citation2010) have served as mechanisms of preserving sacred natural sites. The customary laws and oral declaration, punishment and social banishment in Guji Oromo are serving as indigenous mechanisms of preserving sacred natural sites. This apparently indicates that sacred natural sites are protected by different traditional mechanisms in a different cultural setting.

5. Conclusion

It is apparent from the entire discussion that Guji people have yearlong indigenous mechanisms of preserving sacred natural sites. These mechanisms are customary laws and oral declaration, taboos, customary punishment and social banishment. Customary law that formulated and declared in Gada system, pertaining to sacred natural sites embodies, the prohibited actions and activities for the sake protecting the sites from detrimental, and despoilment interventions of local people. This law clarifies who does what and how in the endeavor of preserving sacred natural sites. In this law, every Guji is traditionally obliged to protect sacred shrines, which are embedded in the overall cultural practices; however, the mandates of practically dealing with some technical issues like passing customary punishment and making strict scrutiny of the status of sacred natural sites are given to personages like Abba Gada, Hayyuu and Jadhaaba. These groups work with other Gada councils to sustain Gada shrines in the area. The indigenous mechanisms of preserving sacred natural sites in the area are emanated from the worldview of Guji Oromo about culture–nature interconnection. Unlike western anthropocentric view that dichotomizes the nature and human culture as separate phenomena, Guji perceive that physical environment in general and sacred natural sites, in particular, is an integral part of Gada system tradition. The Gujis mutualistic view about cultural practices and sacred natural sites linkage is the source of origination and development of indigenous mechanisms of preserving sacred natural sites. Specifically, the dedication of sacred natural sites to rituals of the Gada system and adoring of Waaqaa is the building block for the practicability of indigenous mechanisms of preserving and sustaining sacred natural sites. The cultural practices of Guji at large and Gada system, in particular, are embedded with sacred natural sites in multiple ways. Therefore, the indigenous mechanisms of preserving sacred natural sites in Guji are originated from the mutualistic view of the people about the interconnection between culture and nature in general and inextricability between Gada system and sacred natural sites (Ardaalee Jilaa) in particular. Generally, due to the inextricability of sacred natural sites and Guji Oromo Gada system, the indigenous preservation of sacred natural sites is another way of sustaining Gada system, which was now registered as intangible heritage of Oromo community by United Nations, Science, Education and Culture Organization.

Acknowledgements

Firstly, I would like to thank Dr Awoke Amzaye who was my supervisor when I was conducting my thesis in Hawassa University. And also thanks are due to the academic staff of social anthropology in Hawassa University and Bule Hora University who directly or indirectly contributed to this article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Gemeda Odo Roba

Gemeda Odo Roba With MA in Social Anthropology from Hawassa University, I have four years’ teaching experience in Bule Hora University. I have been teaching Social Anthropology department in the University since 2014. My research interest areas are sacred natural sites, indigenous knowledge and traditional medicines among the others. Currently I am director for academic affairs directorate in Bule Hora University.

Notes

1. Prime body in the leadership of the Gada system.

2. Yuubaa is a general term refers to all retired Abbaa Gadaas. However, Baatuu refers to the former Abbaa Gadaa that transferred power to the next party and do not exceed eight years after the power transfer. Yuuba diqqaa lives from 8–16

3. Gujo is believed to be the ancestor of Guji people, who had three children, namely, Uraago, Maattoo and Hookku in descending order. The tree Guji phratries currently known as Uraaga, Maattii and Hookkuu are derivatives of names of those ancestors. In Guji tradition, the first son of Gujo was Uraago, the next son was Maattoo and the third and last son was Hookku.

4. Hayyuus are the members of Gadaa councils who have responsibility to pass customary decisions over the contestable cases in the Gada system. They are customary court in the Guji Oromo Gadaa system.

5. Violator, in this case, is used to denote a person who violates the customary laws, proclamation, myths, beliefs

6. Gada balbalaa is Afaan Oromoo term that refers to the members of the Gadaa ruling parties that have been

7. Worra dibbee refers to the inhabitants nearby the Gadaa shrines or neighborhood that can closely observe the

8. Korma is Afaan Oromoo term and it refers to a bull, whereas Goronsaa is a heifer.

9. Haaganaa tree is a traditionally ordained and identified tree for only cultural and ritual purposes of Gadaa system.

References

- Anne, F. (2011). Consequences of wooded shrine rituals on vegetation conservation in west Africa: A case study from the Bwaba cultural area (West Burkina Faso). Biodiversity and Conservation, 20, 1895–14. doi:10.1007/s10531-011-0065-5

- Ayelew, G. (2012). Customary laws in Ethiopia: A need for better recognition? A women’s rights perspective. Copenhagen: The Danish Institute for Human Rights.

- Debsu, D. N. (2009). Gender and culture in southern Ethiopia: An ethnographic analysis Guji OromoWomens’ customary right. The Center for African Area Studies, Kyoto University. doi:10.14989/71111

- Desalegn, F. (2013). Indigenous knowledge of Oromo on conservation of forests and its implications to curriculum development: The case of the Guji Oromo (Thesis). Retrieved from http://10.6.20.92:80/jspui/handle/123456789/8414

- Doffana, Z. (2014). ‘Dagucho [Podocarpus falcatus] Is Abbo!’ Wonsho Sacred Sites, Sidama, Ethiopia: Origins, maintenance motives, consequences and conservation threats (PhD Dissertation). University of Kent, Canterbury, the United Kingdom.

- Doffana, Z. D. (2017). Sacred natural sites, herbal medicine, medicinal plants and their conservation in Sidama, Ethiopia. Cogent Food & Agriculture, 3(1), 1365399. doi:10.1080/23311932.2017.1365399

- Dudley, N., Higgins-Zogib, L., & Mansourian, S. (2009). The links between protected areas, faiths, and sacred natural sites. Conservation Biology, 23(3), 568–577. doi:10.1111/cbi.2009.23.issue-3

- Endalkachew, B. (2015). The place of customary and religious laws and practices in Ethiopia: A critical review of the four modern constitutions. Social Sciences, 4(4), 90–93. doi:10.11648/j.ss.20150404.14

- Gemeda, O. (2018). Why some natural areas are sacred? Lesson from Guji Oromo in southern Ethiopia. Global Journal of Arts and Humanities, 1, 6.

- Hinnant, J. (1977). The Gadaa system of the Guji of southern Ethiopia (Doctoral Dissertation). The University of Chicago, Illinois.

- Jalata, A., & Schaffer, H. (2013). The Oromo, Gadaa/Siqqee Democracy and the liberation of Ethiopian colonial subjects. AlterNative: an International Journal of Indigenous Peoples, 9(4), 277–295. doi:10.1177/117718011300900401

- Jemjem, U., & Dhadacha, G. (2011). Gadaa democratic pluralism with particular reference to the Guji Socio-cultural and Politico-legal systems. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Rela Printing Press.

- Jeylan, W. (2006). A critical review of the political and stereotypical portrayals of the Oromo in the Ethiopian historiography. Nordic Journal of African Studies, 15(3), 256–276.

- Kandari, L. S., Bisht, V. K., Bhardwaj, M., & Thakur, A. K. (2014). Conservation and management of sacred groves, myths, and beliefs of tribal communities: A case study from north India. Environmental Systems Research, 3(1), 16. doi:10.1186/s40068-014-0016-8

- Katrina, C. (2011). Customs and constitutions: State recognition of customary around the world. Thailand: IUCN.

- Legesse, A. (1973). Gadaa: three approaches to the study of African society. New York: Free Press.

- Lemessa, M. (2014). Indigenous forest management among the Oromo of Horro Guduru, western Ethiopia. Ethiopian Journal of Social Sciences and Language Studies, 1(2), 5–22.

- Maffi, L., & Woodley, E. (2012). Biocultural diversity conservation: A global sourcebook. London: Routledge.

- Nath, P., & Gam, N. (2012). Conservation of plant diversity through traditional beliefs and religious practices of ritual mishing tribes in Majuli river Island, Assam, India. Indian Journal of Fundamental and Applied Life Sciences, 2(2), 62–68.

- Negi, C. S. (2010). Traditional culture and biodiversity conservation: Examples from Uttarakhand, central Himalaya. Mountain Research and Development, 30(3), 259–265. doi:10.1659/MRD-JOURNAL-D-09-00040.1

- Ormsby, A. A., & Bhagwat, S. A. (2010). Sacred forests of India: A strong tradition of community-based natural resource management. Environmental Conservation, 37(3), 320–326. doi:10.1017/S0376892910000561

- Oviedo, G., Jeanrenaud, S., & Otegui, M. (2005). Protecting sacred natural sites of indigenous and traditional peoples: An IUCN perspective. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN.

- PCCFDRE. (2007). Population and households of Ethiopia, 2007. Retrieved from https://knoema.com//EHPH2007/population-and-households-of-ethiopia-2007?region=1004610-guji-zone

- Samanthae, W., & Cathy, L. (Eds.). (2003). The importance of sacred natural sites for biodiversity conservation. In International workshop on the importance of scared natural sites for biodiversity conservation. France: UNESCO.

- Taddesse, B. (1995). Deforestation and environmental degradation in Ethiopia: The case of Jam Jam province. Northeast African Studies, 2(2), 139–155. doi:10.1353/nas.1995.0010

- Teshome, A. (2016). Indigenous ecological knowledge and pastoralist perception on rangeland management and degradation in Guji Zone. Consilience: the Journal of Sustainable Development, 15(1), 192–218.

- Verschuuren, B. (2010). Sacred natural sites: Conserving nature and culture. France: Routledge.

- Verschuuren, B., Wild, R., McNeely, J., & Oviedo, G. (Eds.). (2010). Sacred natural sites conserving nature and culture. London EC1N 8XA, UK: Earthscan.

- Wild, R., McLeod, C., & Valentine, P. (2008). Sacred natural sites: Guidelines for protected area managers. London and Washington, DC: IUCN.