Abstract

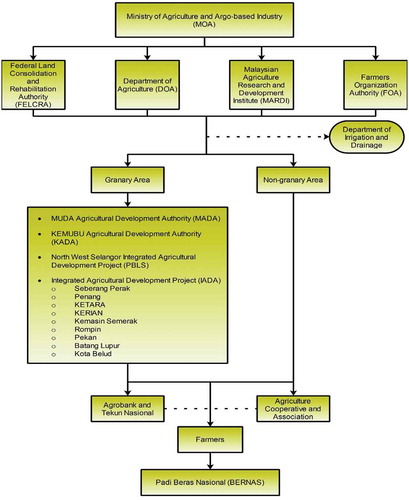

This study aims to investigate the contribution of leading key players for maintaining and increasing the quality of paddy industry in Malaysia. The Ministry of Agriculture and Argo-based Industry (MOA) plays a key role in improving the production of paddy and welfare of the farmers in this country by doing the transformation within the agricultural sector. Hence, in order to ensure the successful implementation and fulfilment of direction from Ministry of Agriculture (MOA), Federal Land Consolidation and Rehabilitation Authority (FELCRA), Department of Agriculture (DOA), Malaysian Agricultural Research and Development Institute (MARDI) and Farmers Organisation Authority (FOA) involve greatly in Malaysian paddy production chain with each agency playing different roles. BERNAS acts as the main regulatory body in the production chain. It does so by ensuring the stability of rice trade within the country as well as its distribution. By way of qualitative methodology, this study conducted in-depth interviews with six key informants on their respective agency’s contribution to paddy industry in Malaysia. We also conducted a review of the agencies’ web page and previous literature on respective agencies. This research found that the farming area is divided into two major sections; the granary area and non-granary area. The granary area is the area recognized by the government as the main paddy production area and the non-granary area is the opposite of this recognition. This research provides substantial information about the roles of key players in Malaysia paddy value chain, especially MADA and Farmers Organisation Authority and discusses current issues, initiatives and suggestions in relation to the paddy industry.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Government agencies play significant roles in agricultural industry including providing farming infrastructures such as irrigation systems and dams but also, the price control of the inputs, subsidies and tariffs that will directly impact the sustainability of farmers. Apart from investing to improve physical infrastructure in the agricultural modernization programme, the government is also supervising and monitoring this programme via a host of centralized and coordinated governmental agencies at its disposal. The authorities are dedicated and mandated to assist the paddy farmers to improve their productivity, output, earning, marketing and technology practices. This study investigated the contribution of leading key players for maintaining and increasing the quality of paddy industry in Malaysia. The Malaysian paddy sector is protected by means of a high degree of government intervention. We had summarised our findings from in-depth interviews by using seven themes, namely Perception, Price, Subsidies, Training, Infrastructure, Issues and Effort which frequently appeared and mentioned by the interviewees from our in-depth interviews.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

1. Introduction

1.1. Land area and paddy production in Malaysia

Land area for paddy production has grown tremendously since 1961 from 51,649 hectares to a peak land area of 766,180 hectares in 1972 and maintained within the range area through 1980 and remained stagnant since. From 716,873 hectares in 1980, the land area for paddy plantation has gone down to 698,544 hectares in 2000. Since then, the land area for paddy production has remained at an average of 677,000 hectares through 2014, which gives the area of paddy harvest a growth rate of −0.2% (Harun & Ariff, Citation2017).

On the other hand, the opposite trend is observed for the granary areas where major irrigation is more than 4,000 hectares, and it is recognised by the government as the main paddy-producing area. 317,041 hectares were recorded in 1980, whereas, in 2014 a much higher land area of 400,733 hectares was recorded (“Malaysia Economic Statistics—Time Series 2015”, 2017; “Press Release: Selected Agricultural Indicators 2015”, Citation2015a).

Compared to the global rice production, Malaysia is only a minor rice producer contributing only 0.4% of the total global output (Ibrahim & Mook, Citationn.d.). Rice production in Malaysia has doubled after four decades from 914,550 tons in 1970 to 1,685,236 tons in 2013. An annual increase of rice production, however, is not consistent with the declining productions in several years. These scenarios were due to the weather conditions, pest and disease outbreak (Harun & Ariff, Citation2017). The average yield of paddy per hectare, however, showed an increase in value from 2,852 kg/ha in 1980 with paddy production of 2,044,604 tonnes and rice production of 1,318,332 tonnes to 4,194 kg/ha in 2014 with paddy production of 2,848,852 tonnes and rice production of 1,835,015 tonnes. In terms of rice production per hectare, a value of 1.84 tons/ha was recorded in 1980 compared to 2.70 tons/ha recorded in 2014 (“Malaysia Economic Statistics—Time Series 2015”, Citation2018). This gives an annual growth rate of paddy production at 1.9% and its yield at 2.1% (Harun & Ariff, Citation2017).

Promising rice production is better particularly in granary areas, as in 1980, the rice production was recorded at 2.65 tons/ha and 3.39 tons/ha in 2014. Since the Third National Agricultural Policy 1998, eight granary areas were specified to achieve a minimum self-sufficiency level (SSL) for rice at 65%. However, by 2014, Malaysia had only managed to achieve an SSL of 71.6% (“Supply and Utilization Accounts Selected Agricultural Commodities, Malaysia 2010–2014”, Citation2015b).

To date, 10 granary areas have been recognised in Malaysia, namely Muda Agricultural Development Authority (MADA), Kemubu Agricultural Development Authority (KADA), Kerian Integrated Agriculture Development Area, Barat Laut Selangor Integrated Agriculture Development Area, Seberang Perak Integrated Agriculture Development Area, Pulau Pinang Integrated Agriculture Development Area, North Terengganu Integrated Agriculture, Development (KETARA), Kemasin Semerak Integrated Agriculture Development Area, Pekan Integrated Agriculture Development Area and Rompin Integrated Agriculture Development Area (“Malaysia Economic Statistics—Time Series 2015”, Citation2018). Besides granary areas, there are also another 74 secondary granaries and 172 minor granaries in Malaysia that total up to 28,441 and 47,653 hectares, respectively. Secondary and small granaries are classified based on the scale of irrigation supported (Ibrahim & Mook, Citationn.d.). Apart from the Ninth Malaysia Plan, the Northern Corridor Economic Region (NCER) plan was also introduced to ensure that the national target is met (Othman, Muhammad & Bakar, Citation2010).

1.2. Major actors and support system in Malaysian upstream paddy production chain

The viability of Malaysia’s rice industry depends greatly on government initiatives and support. Support by the government is not limited to only farming infrastructures such as irrigation systems and dams but also, the price control of the inputs, subsidies and tariffs that will directly impact the sustainability of farmers. The leading key player that determines the progress of these farmers is the Ministry of Agriculture (MOA) in Malaysia which spearheads transformation process within the agriculture sector via a planned, integrated and holistic approach based on a collaborative organizational effort. This is carried out in both intellectual and physical engagements towards the realization of the National Agrofood Policy 2011–2020 (Pilo, Citation2017).

Large-scale irrigation systems were only introduced in Malaysia in the early 1900s through Kerian Irrigation Scheme and the Wan Mat Saman Scheme. The country’s farming was upgraded when the Department of Irrigation and Drainage (DID) was formed in 1932 together with the Department of Agriculture (DOA). Consequently, 85% of the total paddy cultivation is irrigated and the balanced 15% are those of non-irrigated areas that include rain-fed paddy fields and hill paddy which are mostly from East Malaysia (Ibrahim & Mook, Citationn.d.).

In an effort to ensure the successful implementation and fulfilment of direction from MOA, Federal Land Consolidation and Rehabilitation Authority (FELCRA), DOA, Malaysian Agricultural Research and Development Institute (MARDI) and Farmers Organisation Authority (FOA) play crucial roles in the production of paddy industry with each and each agency plays a different role in the support system as shown in Table and Table .

Table 1. The Key Players and Support System for Paddy Production

Table 2. Five Forces Model Framework

Table 3. Transcription process and data collection

Table 4. Thematic analysis acronyms and definition

Table 5. Findings from Thematic Analysis of In-depth Interviews

FELCRA was established in 1966 to develop the rural sector by assisting the rural community in national economic activities to improve their standard of living (“FELCRA Profile”, Citation2018). FELCRA is responsible to develop land with the permission of state government together with the transfer of knowledge and technology to farmers (see Figure ).

Whereas, MARDI is a registered body in Malaysia that focuses on the research and development of agriculture. They do not only support farmers on technical services such as training, quality testing and certification but also the development of marketing and improving the technology used (“Malaysia: BASF and MARDI Announce Rice Production Project”, Citation2010). In fact, since 2010, MARDI has already developed 44 rice varieties and aspires to innovatively improve farmers’ income (Muthayya, Sugimoto, Montgomery, & Maberly, Citation2014). One of the advancements and development of conventional paddy plantation is the cooperation of MARDI, Seri Merbok Rice Factory Sdn. Bhd. with BASF Malaysia whereby a Clearfield Production System is introduced to control the weed in direct seeding culture. This system consists of herbicide-tolerant rice variety and stewardship guide (“MARDI, Kilang Beras Seri Merbok dan BASF Lancar Pusat Tani Clearfield pertama di Asia Pasifik”, Citation2017). If it is properly implemented, this system is able to increase paddy harvest by 50-60%, and this is one of the first systems introduced in the Asia Pacific (“Malaysia: BASF and MARDI Announce Rice Production Project”, Citation2010). Apart from this, MARDI has also initiated an investigation into the application of technology by organic farmers in 2014. Among the technologies that have been studied in terms of their viability include control of pest and diseases, accreditation, use of legumes for control of weeds, mulching, fertilizer and buffer zones (Abiola, Mad, Alias, & Ismail, Citation2016).

FOA is an organization founded by farmers and established under Act 109 in 1973 (See Figure ). FOA plays an important role in implementing national policies and ensuring a balanced development from all parties besides its central role in enhancing the business and investment growth in agriculture and improving the socio-economic status as well as quality of life of the farmers (“Farmer’s Organization Introduction”, Citation2019).

The farming area in Malaysia managed by the farmers is divided into two major sections, namely as the granary area and non-granary area. Granary area is an area that has major irrigation schemes and is normally more than 4000 hectares. These are the areas that are recognized by the government of Malaysia as the main paddy production areas (Siwar, Nor, Muhammad, & Golam, Citation2014). Apart from all these support roles, farmers are the main actors at the production level in which the plantation of paddy and implementation of all plantation methods are at its final stage. Farmers would also have to outsource their own financial support from entities such as Agrobank as well as Agricultural Cooperative and Association for technical support.

Whereas, BERNAS is the main regulatory body in the supply chain that ensures the stability of rice trade within the country as well as its distribution. The obligation of these group of companies includes managing the Bumiputera Rice Millers Scheme and delivery of paddy price subsidies to farmers on behalf of the government. To further strengthen the position of BERNAS in the paddy supply chain, BERNAS has now ventured into seeding and farming activities as well as rice complementary business (Industry, M.o.A, Citation2019).

Figure 1. Major Actors and Support Systems in Malaysian Upstream Paddy Production Chain.

Source: Own illustration, 2019.

In addition to government bodies involved in the regulation and policymaking for the production of paddy and wellbeing of farmers, Agrobank is the farmer’s pillar of financial support. Paddy-i or Tawarruq is a program under Agrobank to support the capital for rice planting activities in paddy field which is certified by government agencies. To further strengthen their support in the production chain, Agrobank signed their first memorandum of understanding (MoU) with University Putra Malaysia (UPM) to leverage the strength of both organizations to further evaluate agri-business proposal and enhance the application in crop management. This partnership has also been extended to include MARDI as a stakeholder (Bersama Siaran Akhbar, Citation2017).

All stakeholders are targeted to improve the production of paddy and a stable income for farmers which aligned with the government policies, namely Malaysian National Agro-food Policy. The policy consists of six strategies to strengthen the value chain of paddy. These six strategies include increasing production and quality of rice, improving the efficiency of mechanization and automation, intensifying the use of a by-product from paddy plantation, strengthening the rice stockpile management, restructuring the incentive and subsidy for rice, and augmenting the institutional management of paddy and rice (Haron, Citation2016).

2. Theoretical framework

This study adopted the Five Forces Model Framework (see Table ). Porter (Citation2008) wrote on the productivity of firms and support systems, namely workers to work collectively, and the importance of the national and regional environment to support in increasing the productivity. Insufficient fund is a barrier to entry into any particular market (www.hbr.org, n.d.). Five Forces model framework can be adopted to analyze the industry’s competitive forces and to shape the organisation’s strategy.

Five Forces model analyzes threats of new entrants, threats of substitutes, bargaining power of buyers, bargaining power of suppliers and rivalry among existing competitors. As found by Humphrey and Schmits (Citation2004) found that good local system relationships is vital. In this context, relationships refer to the link between firms and the support systems including government agencies.

Wu, Tseng, and Chiu (Citation2012) applied the aspects of Porter’s Five Forces in their study. For bargaining of supplier, there are six criteria that meet the requirement of this research: (1) it is commanded by several organizations and is more concentrated than the business it offers to; (2) the supplier is not competing with other substitute products in the industry; (3) the supplier group do not perceive the industry as an important group; (4) the buyer needs the supplier’s products as it is an important input; (5) increase in switching cost and differentiation of supplier’s products; (6) in forward integration, the supplier is powerful enough to place a credible threat. For pressure from substitute products, the criteria of this research are the industry is competing with substitutes according to trends in terms of price-performance trade-off and also the substitute products are produced by high profiting companies.

Pringle and Huisman (Citation2011) applied Porter’s Five Forces Model to Ontario’s University System. The faculty and administration were categorized as the suppliers while buyers were parents and students. The substitute products were the availability of online degree programs and university’s profit. The power of the supplier is strong when there are limited numbers of suppliers given in a large number of customers. Therefore, the supplier holds the power to charge at higher price, limiting quality or services. The university expenditure is made up of the faculty as the largest contributor followed by the non-academic staff. Therefore, the faculty holds the power in decision-making and only require little interference from the administration due to their prestige and expertise. Furthermore, according to Barutcu and Mustafa (Citation2012), E-SCM lowers dependence on current distribution channels, reduces suppliers’ bargaining power and tends to increase e-tailers’ negotiating power over suppliers. As for substitution threat: The e-market place threat of substitute products or services is high because there are many options for e-suppliers and e-tailers. Increasing the number and closer substitute products lead to increasing the tendency of e-tailers to switch between suppliers.

3. Methodology

3.1. Transcription of in-depth interview sessions

Six expert interviews and all in-depth interview sessions were conducted, recorded and transcribed by appointed research assistants. To maintain confidentially of the interviewees, the names and dates of the interviews are not disclosed (See Table ). The steps involved in the transcription process are as follows: (1) Discussion during all in-depth interviews was recorded by researchers; (2) Audio recording was transcribed by a research assistant.

3.2. Thematic analysis

To summarize this study’s findings from in-depth interviews, we conducted thematic analysis using the following themes (See Table ). Thematic analysis was conducted to classify all the information gathered from the in-depth interviews into selected themes. Themes selected are as follows:

4. Findings

As paddy is the nation’s staple food, paddy plantation has been receiving generous subsidies compared to other crops. Nearly two (2) billion subsidies, incentives and support are provided by the federal government for the paddy industry. The government’s support in terms of subsidies and incentives begins as early as the preparation of land to the sale of paddy.

The government emphasis on paddy (plantation) where it can be said that paddy has been receiving subsidies in each and every level (of production). We can see that ever since paddy is planted since 1979, the government has introduced Federal Government Paddy Fertilizer Scheme (SBPKP) whereby free fertilizers and materials are provided for free up to RM690 per hectare. (Expert Interview 1, 2018)

Government subsidy inputs include seedlings, fertilisers and pesticides for paddy farming and price for paddy. As mentioned in the interview with Expert 3,

Fertilizer incentives are also available. Back then, there were incentives for paddy production but now not anymore. So, the ones left are fertilizer incentives and pesticides incentives. (Expert Interview 3, 2018)

MADA is responsible for managing farmers in terms of irrigation, planting and technical advices. This agency has been working hard on increasing rice production in Malaysia. It is the intensive, efficient irrigation and drainage facilities that paved the way for farmers to practice double cropping with high yielding varieties such as MR219 and MR220. These varieties demand sufficient water resources and control for optimal yields. Given the per-humid conditions in lowland areas of Malaysia, irrigation is crucial for prolonging wet condition of these new varieties of paddy. As stated by Expert Interview 1,

Previously, when MADA was established in 1970, the production was only 3.76, at most. From time to time, technological advancement, government incentive, recovery in terms of infrastructure resulted in an increase (of production). Although it took some time from 1970 till now, MADA is currently producing at around the rate 6.19. (Expert Interview 1, 2018)

The government has given out strong support for paddy plantation and production even during the world food crisis in 2008. Paddy Production Incentive Scheme (SIPP) was introduced by the government to help paddy farmers in producing their output.

The government created another scheme called Paddy Production Incentive Scheme (SIPP), giving farmers the incentives where many agricultural inputs, fertilizers were given, whereby if we were to calculate the cost per hectare supported by the government is as much as RM2645 per hectare. (Expert Interview 1, 2018)

To be precise, RM 2645 worth ofsubsidies is the total subsidies for agricultural inputs, paddy price, and agricultural inputs including fertilizers, pesticides and vitamin boosters or in the form of incentives. Among the Regulatory Bodies for Granary Areas, MADA has performed its duties and acts as the main producer for rice production in Malaysia. In Malaysia, production of rice is solely for domestic market. As mentioned by Expert Interview 1,

If we look at MADA, MADA is the main contributor where 40% of 70% (of rice production) is contributed by MADA. We are called as The Pulse of the National Rice Paddy. (Expert Interview 1, 2018)

MADA provides training and gives advisory services to paddy farmers at all stages starting from preparation of land until the final stage which is the harvest stage. These trainings range from counselling to using fertilizers, appropriate pesticides, and integrated pest control. In essence, MADA facilitates the cultivation of paddy according to its needs on two basic things. First, the infrastructure and irrigation needs:

Paddy farm requires irrigation and that irrigation requires infrastructure. Therefore, we provide infrastructure including its management. Both are technology related, so we have about 700 development officers or extension officers. The task is to get down and accompany these farmers to convey, remind, advise and guide these farmers on good farming practices and the cultivation of paddy which we recommend from time to time as the latest technology advances. (Expert Interview 2, 2018)

MADA’s contribution to farmers is supported by the Paddy Estate Project Manager (2018) which stated that several courses are organized by respective agencies on how to grow paddy according to the paddy check issued by the Department of Agriculture as well as paddy seasonal operation courses when paddy is at the age of 25–35 until the rice is almost fully grown. MADA has also played its significant role to enhance the outcomes of research, courses and incentives to improve the socioeconomic level of farmers. MADA has created a few programs including integrating farming to ensure the sustainability of farmers’ income per capita. With integrated farming, farmers source of income is more diversified. As stated in the interview with Expert 1,

We created programs to increase paddy production. Based on the result of the paddy crop through advisory services, we recommended quality, legitimate seeds. We make sure a strong infrastructure network to improve water efficiency in the field. Subsequently, we also introduced income other than paddy through livestock, other crops such as plums that may help in sustaining the industry as a side income. If the farmer himself makes rice, then his wife or children can be involved in the sustaining industry. It can indirectly increase the household’s income per capita. (Expert Interview 1, 2018)

In terms of corporate social responsibility, MADA introduced Farmers Education Foundation to support the second generation of MADA farmers. This will help to reduce farmers’ burden to support their family and children.

Our education has a foundation, MADA Farmers Education Foundation. We have a foundation where we provide free tuition and advice to farmer’s children. After that, whoever gets good result, we give out tokens. Every year we help school, university students, diplomas …. (Expert Interview 1, 2018)

There are issues related to production, price and market of paddy plantation in Malaysia related to agencies and farmers.

Generally, it is a stable industry, however it is stable with strong government support. This industry is sometimes a bit complex and need to be micro-managed. (Expert Interview 2, 2018)

Expert 2 believed that today’s production is sufficient although official data from the government stated that Malaysia has the capacity to produce 70% −72% of the production where the remaining (28 − 30%) is imported from overseas. This has created more varieties and options for consumers in Malaysia.

The national production is enough, compared to the total population in Malaysia. It is just that the increase in paddy yield is less in terms of production. (Expert Interview 6, 2018)

The price of paddy in Malaysia is controlled by the government. As mentioned in Expert Interview 2,

The price is currently regulated by the government which sets the price of paddy at the plant at RM 1200 per tonne and includes incentives for selling paddy and so on. On average, 1 tonne of rice is sold, 1 tonne of net is sold by farmers, they can earn about RM 1500 per tonne and on average Malaysia produce rice, I would estimate, among the 5 tonnes per hectare for Malaysia. (Expert Interview 2, 2018)

From the perspective of the industry, it is crucial to expand the granary areas especially from the right edge. Paddy price is quite stable in Malaysia, for instance, at RM1200 per tonne. The price is good for farmers but it is costly for manufacturers as the price of rice is not revised. This is corroborated by an interview with a Technical Officer, 2018 who stated that;

If we follow the paddy’s market price in Malaysia, paddy price is O.K. We see RM1300, RM1200. Depends … for the paddy. For seeds, quite expensive. If it is rice, the price is a little bit lesser …. (Expert Interview 4, 2018)

The price of paddy needs to be revised. Farmers expect the price to be set according to the quality of production.

No matter how good is the quality of paddy, it is still at RM1200. If seedling … RM1300. This is what the farmers are trying to emphasize. If possible, there is no need for ceiling price. Meaning, in terms of quality, the price can follow according to the quality of paddy. If it is on the farmers, they would want RM1200 to be the floor price and not the ceiling price. (Expert Interview 6, 2018)

In Malaysia, the technology used in paddy production is quite advanced compared to the previous production approach. Most field operations in the granary areas are performed using machinery. Both land preparation and paddy harvesting are 100% operated using machinery. On average, other field operations such as seed sowing, manuring and chemical spraying were 80.3%, 78.7% and 84.8% respectively conducted using machinery (DOA, 2009). Mechanization is a way that is viable in lowering production cost, increasing labour and enhancing land productivity. As mentioned in the interview with the Technical Officer,

If we look at paddy industry in Malaysia, technology is moving towards modern technology. If we look at the old days, we plant and so on (using) old technology but now we are moving forward. (Expert Interview 4, 2018)

However, they are issues when it comes to the adoption of technology. Since majority of farmers are elderly, majority 60 years old, they are resistant to change when it comes to the adoption of new technology. Unfortunately, most of the second generation of MADA farmers are not keen to work in the farm. As mentioned in the interview with Expert 1,

These issues related to the MADA level involve youths in the cultivation of paddy fields. One, most youths do not want to do dirty things and such. Our constraints are in that regard. Followed by the foreign workers … when it comes to the elderly, during the introduction of new technology, they are resistant to change. (Expert Interview 1, 2018)

However, precision agriculture is needed to improve paddy farming productivity and efficiency.

Rice production still needs to be improved. We estimate that at least farmers should produce up to 5 tonnes per hectare to cover the nation’s rice stock. (Expert Interview 6, 2018)

5. Conclusion

The Malaysian paddy sector is protected by means of a high level of government intervention. Apart from investing to improve physical infrastructure in the agricultural modernization program, the government is also supervising and monitoring this program via a host of centralized and coordinated governmental agencies at its disposal. The authorities are dedicated and mandated to assist the paddy farmers to improve their productivity, output, earning, marketing and technology practices. Thus, support system, roles of actors in the value chain, rules of governance and critical issues are important elements to be considered for improvement in the industry. We have summarized our findings from in-depth interviews by using seven themes, namely Perception, Price, Subsidies, Training, Infrastructure, Issues and Effort, which frequently appeared and mentioned by the interviewees during the in-depth interviews. This study’s findings have contributed to the literature related to agriculture and paddy industry as both primary and secondary data collection were analysed for this research.

From the technical perspective, we could see that government agencies play their significant roles accordingly. They also have the power to supply inputs, namely fertilisers and pesticides. They also make suggestions to the buyers (farmers) on the best combination of inputs with package for CL paddy. The buyers (the farmers) have options to choose from as well as which supplier they could buy the inputs from. Furthermore, farmers have the authority to decide which inputs, which price and type of technology or machineries to be used in the farms.

In terms of competitive rivalry, the price of paddy is controlled by the government. Regardless of the quality, the price can be followed according to the quality of paddy and from the perspectives of farmers, they prefer the price set based on quality. As for the threat of new entrance, the level of threat is high in terms of the establishment cost and investment cost but the agencies highly support the new entrants in terms of financial and monetary support. The threat for entry is the organic paddy using SRI system. Some agricultural officers believe that organic paddy farming is not cost-efficient, as it is suitable for mass production and requires physically demanding activities. Finally, the second generation of paddy farmers is not interested to join the system (as paddy farmers) which leads to the issue of the adoption of advanced technology among elderly farmers.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the USM Short Term Grant 304.PSOSIAL.6315027 for supporting this research.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Siti Rahyla Rahmat

Siti Rahyla Rahmat is currently senior lecturer in economics at School of Social Sciences, Universiti Sains Malaysia. Her research interests lie in environmental economics, agricultural economics, sustainable development, bio-economy and science policy. She attained her doctoral degree from Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn, Germany.

R.B. Radin Firdaus

R.B. Radin Firdaus is trained in development and environmental economics from Universiti Putra Malaysia and Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia. His area of research includes food security, agricultural development and policy, climate change adaptation and measures and sustainable development.

Samsurijan Mohamad Shaharudin

Mohamad Shaharudin is a senior lecturer at School of Social Sciences, Universiti Sains Malaysia. He obtained his PhD from Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia. He published research on environmental degradation and social impact assessment.

Lim Yee Ling

Lim Yee Ling is an experienced PhD Researcher with a demonstrated history of working in the higher education and private industries. Skilled in scientific development, communication, statistics, analytical instrument and laboratory analysis.

References

- (2019, September). Www hbr.org/ 191979/03/how-competitive-forces-shape-strategy

- (2019, September). Www.visual-paradigm.com/guide/strategic-analysis/what-is-five-forces-analysis/

- Abiola, O. A., Mad, N. S., Alias, R., & Ismail, A. (2016). Resource-use and allocative efficiency of paddy rice production in Mada, Malaysia. Journal of Economics and Sustainable Development, 7, 1.

- Barutçu, S., & Tunca, M. Z. (2012). The impacts of E-SCM on the E-tailing industry: An analysis from Porter’s five force perspectives. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 58, 1047–15. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.09.1085

- BASF. (2010). Malaysia: BASF and MARDI Announce Rice Production Project. Flexnews.

- Bersama, S. A. (2017). MARDI, Kilang Beras Seri Merbok dan BASF lancar Pusat Tani Clearfield® pertama di Asia Pasifik, in Siaran Akhbar Bersama. Alor Star, Malaysia: Siaran Akhbar Bersama.

- Chapagain, T., Riseman, A., & Yamaji, E. (2011). Assessment of system of rice intensification (SRI) and conventional practices under organic and inorganic management in Japan. Rice Science, 18(4), 311–320. doi:10.1016/S1672-6308(12)60010-9

- FELCRA. (2018). FELCRA Profile. Retrieved from http://www.felcra.com.my/background

- Haron, S. (2016). Feeding the Nation. Scientia MARDI, 2.

- Harun, R., & Ariff, E. E. E. (2017). The role of institutional support in Malaysia’s paddy and rice industry. FFTC Agricultural Policy Articles. MARDI.

- Humphrey, J., & Schmitz, H. (2004). Chain governance and upgrading: Taking stock. Chapters. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Ibrahim, N., & Mook, L. S. (n.d.) Factors affecting paddy production under Integrated Agriculture Development Area of North Terengganu (IADA KETARA): A case study. IPICEX.

- Industry, M.o.A. (2019, April 14). Profile MOA. Retrieved from http://www.moa.gov.my/en/objektif;jsessionid=724FE73E9AA5CBF92D93DFC8DCAA787A

- LPP. (2019, April 19). Farmer’s organization introduction. Retrieved from http://www.lpp.gov.my/en/farmer-organization-introduction

- Malaysia, D.o.S. (2015a). Press release: Selected agricultural indicators 2015. Retrieved from https://www.dosm.gov.my/v1/index.php?r=column/pdfPrev&id=bnR4ZFJnbXVOQmt6TDhNNmh3M0Y5dz09

- Malaysia, D.o.S. (2015b). Supply and utilization accounts selected agricultural commodities, Malaysia 2010–2014. Retrieved from https://www.dosm.gov.my/v1/index.php?r=column/ctheme&menu_id=Z0VTZGU1UHBUT1VJMFlpaXRRR0xpdz09&bul_id=ZzNBdUlWT2l4NE4xNCt6U2VNc1Q2QT09

- Malaysia, D.o.S. (2018, April 15). Malaysia economic statistics - time series 2015. Retrieved from https://www.dosm.gov.my/v1/index.php?r=column/ctimeseries&menu_id=NHJlaGc2Rlg4ZXlGTjh1SU1kaWY5UT09

- Muthayya, S., Sugimoto, J. D., Montgomery, S., & Maberly, G. F. (2014). An overview of global rice production, supply, trade, and consumption. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1324(1), 7–14. doi:10.1111/nyas.2014.1324.issue-1

- Othman, Z. (2012). Information and communication technology innovation as a tool for promoting sustainable agriculture: A case study of paddy farming in west Malaysia ( Doctoral dissertation), University of Malaya. doi:10.1094/PDIS-11-11-0999-PDN

- Othman, Z., Muhammad, A., Bakar, A., & Akib, M. (2010). A sustainable paddy farming practice in West Malaysia. International Journal of Interdisciplinary Social Sciences, 5, 2.

- Pilo, W. (2017, April 20). SRI farm method introduced in Long Semadoh. Borneo Post Online. Retrieved from https://www.theborneopost.com/2017/07/21/sri-farm-method-introduced-in-long-semadoh/

- Porter, M. E. (2008). The five competitive forces that shape strategy. Harvard Business Review, 86(1), 25–40.

- Pringle, J., & Huisman, J. (2011). Understanding Universities in Ontario, Canada: An industry analysis using Porter’s five forces framework. Canadian Journal of Higher Education, 41(3), 36–58.

- Sato, S., & Uphoff, N. (2007). A review of on-farm evaluations of system of rice intensification methods in Eastern Indonesia. CAB Reviews: Perspectives in agriculture, veterinary science. Nutrition and Natural Resources, 2(054), 1–12.

- Siwar, C., Nor, D., Muhammad, Y., & Golam, M. (2014). Issues and challenges facing rice production and food security in the granary areas in the East Coast Economic Region (ECER), Malaysia. Research Journal of Applied Sciences, Engineering and Technology, 7(4), 711–722. doi:10.19026/rjaset.7.307

- Suhaimee, S., Ibrahim, I. Z., & Abd Wahab, M. A. M. (2016). Organic agriculture in Malaysia. FFTC Agricultural Policy

- Tey, Y. S., Darham, S., Noh, A. M., & Idris, N. (2010). Acreage response of paddy in Malaysia. Agricultural Economics, 56(3), 135–140.

- University, C. (2017). Overview of SRI in Malaysia. New York, NY: College of Agriculture and Life Sciences.

- Wu, K. J., Tseng, M. L., & Chiu, A. S. (2012). Using the analytical network process in Porter’s five forces analysis–case study in Philippines. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 57, 1–9. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.09.1151