?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Vegetables are important for income generation to a large proportion of the rural households. Enhancing tomato farmers to reach markets and actively engage in the markets is a key challenge influencing tomato production in Ethiopia. The perishable nature of tomato necessitates effective marketing channels choice decisions. So, the main objective of this study was analyzing the determinants of market outlet choice decisions of tomato producers. The two-stage random sampling procedure was used to select the sampled kebeles and households, whereby 235 farm households were surveyed for the study. Both primary and secondary data were collected to address the objectives. The collected data were analyzed using descriptive statistics and an econometric model by using SPSS and STATA software. Multivariate probit Model results showed that the probability to choose wholesalers, collectors, retailers, and consumers market outlets were significantly affected by age of the household head, educational status of the household head, distance to the nearest market, access to credit, owning transport facility, land allocated to tomato and household size. Policy implications drawn from the study findings include that the government and concerned stakeholders should focus on strengthening rural-urban infrastructure, intensification of land for tomato, expanding the accessibility of credit and strengthening the existence of formal and informal education.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

The Agricultural sector contributes 46% of GDP, 80% of export value, and about 73% of employment for the Economy of Ethiopia. Vegetable production is an important activity in the agricultural sector of the country following the development of irrigation and increased emphases given by the government to small scale commercial farmers. Tomato is the most frequently consumed vegetables in many countries, becoming the main supplier of several plant nutrients and providing an important nutritional value to the human diet. The study area is the potential producer of tomato. Despite its productivity, the nature of the product in terms of perishability on one hand and lack of organized marketing system on the other resulted in low producers’ price. Analysis of the factors affecting market channel choice decision is very important in order to enhance tomato farmers to reach markets and actively engage in the markets to have an attractive price.

Competing Interests

The authors declares no competing interests.

1. Introduction

Agricultural performance in the continent is vital to improve food and nutrition security, accelerate poverty reduction, and boost overall growth by contributing about 43% of the GDP, 80% of employment and 90% of the export value (Ministry of Finance and Economic Development [MoFED], Citation2011). Having all this importance, agriculture continues to face a number of problems and challenges. The major ones are adverse climatic conditions, lack of appropriate land use system resulting in soil and other natural resources degradation, limited use of improved agricultural technologies, the predominance of subsistence agriculture and lack and/or absence of business-oriented agricultural production system, limited or no access to market facilities resulting in low participation of the smallholder farmers in value chain or value addition of their produces (Bezabih & Hadera, Citation2007). Despite the significant recovery and continued output growth in the last two decades, African agriculture still scores low in terms of productivity, measured in yield levels, relative to other parts of the world. The growth of agriculture in Ethiopia is a major contributor to overall economic growth and remarkable occurrence for Africa, which lags in agricultural performance globally and increasingly dependent on imported staple foods to feed its population (Efa & Tura, Citation2018).

Ethiopia has various climate and altitude conditions that are favorable to various agricultural activities. There are several lakes and perennial rivers that have great potentials for irrigated agriculture. The groundwater potential of the country is about 2.6 billion cubic meters. Groundwater in the country is generally of good quality and it is frequently used to supply homes and farmsteads. The potentially irrigable land area of the country is estimated at 10 million hectares, out of which only about 1% is currently under irrigation. Most of the soil types in fruits and vegetables producing regions of the country range from light clay to loam and are well suited for horticultural production (Addisu, Citation2017).

According to CSA (Citation2015), Vegetable production is becoming an increasingly important activity in the agricultural sector of the country following the development of irrigation and increased emphases given by the government to small scale commercial farmers. Recently, due to high nutritional value vegetable does have ever-rising demand both in local and foreign markets and are classified among those export commodities’ that generate considerable amount of foreign currency earnings to the country. As a matter of these fact, commercial farms in Ethiopia used to grow vegetables over a considerable land area for years. Vegetable production provides a source of income for the smallholder farmer as well as an important source of food security for the people of Swaziland, thereby reinforcing the overall development of poverty reduction goals (Fentie, Goshu, & Tegegne, Citation2017).

Tomato (Lycopersicon Esculuntum Mill) is one of most important edible and nutritional vegetable crops in the world. It ranks next to potato and sweet potato with respect to world vegetable production. It is widely cultivated in tropical, sub-tropical and temperate climates. According to FAOSTAT (Citation2009), 126 Million tons of tomatoes were produced in the world. China, the largest producer accounted for about one-fourth of the global output, followed by the United States, Turkey, Iran, Mexico, Brazil, and Indonesia. It is one of the most economically important vegetable crops and is widely cultivated in the world with the total tones in area and production of 5,227,883 ha and 129,649,883 in 2008. It is the most frequently consumed vegetable in many countries, becoming the main supplier of several plant nutrients and providing an important nutritional value to the human diet (Willcox, Catignani, & Lazarus, Citation2003). The crop generally requires warm weather and abundant sunshine for best growth and development. Vegetative and reproductive growth takes place at 12°C (Mebrat, Citation2014).

According to Bezabih and Hadera (Citation2007), in the eastern part of Ethiopia production of horticultural products is seasonal and the price is inversely related to supply. During the peak supply period, the prices decline. The situation is worsened by the perishability of the products and poor storage facilities. According to the same study, along the vegetable channel, 25 percent of the product is spoiled. Vegetable production is poorly addressed in Ethiopia. However, these days efforts have been stepped up to improve and support the sector. Within this line, the current Growth and Transformation Plan (GTP) prioritize intensive production and commercialization of horticulture as a sector for attention. Thus, the development policy initiates the need to accelerate the transformation of the sub-sector from the subsistence to business-oriented agriculture. But, the existing constraints of production, post-harvest handling, and marketing such as input utilization, productivity, packing, warehousing cold storage, and distribution have played their deterring role in the production, trade, and consumption of vegetables in Eastern Ethiopia (Mebrat, Citation2014).

Fogera woreda is one of the tomatoes producing areas in the south Gonder zone. The study area is mainly constrained by seasonality. The nature of the product in terms of perishability on one hand and lack of organized marketing system on the other resulted in low producers’ price. The involvement of market intermediaries, lack of proper coordination among the value chain actors, and low marketing margins are shared among the actors as share to producers and quality and post-harvest losses are the major problems. Enhancing tomato farmers to reach markets and actively engage in the markets is a key challenge influencing tomato production in Ethiopia. The perishable nature of tomato necessitates effective marketing channels. And choices of channels are one of the important factors for producers because different channels are different profitability and cost. Even though tomato is economically and socially important vegetable, determinants of market channel choice decisions of tomato farmers have not studied and documented well in the study area. Therefore, this study was initiated to fill this gap and may contribute towards the improvement of strategies for reorienting the supply chain system at Fogera Woreda of the North Gonder zone.

2. Research methods

2.1. Description of the study area

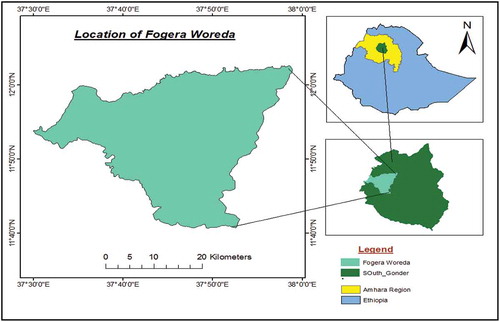

Fogera is one of the woredas in Amhara region of North West Ethiopia. Fogera is part of the south Gonder Zone. The district is bordered on the south by Dera, on the west by Lake Tana, on the north by the Reb which separates it from Kemekem, on the northeast by Ebenat, and on the east by Farta (Figure ).

Wereta city is the administrative center for this woreda. The altitude of this woreda ranges from 1774 to 2415 meters above sea level. Rivers in Fogera include the Gumara and the Reb. Both of which drain into Lake Tana. A survey of the land in Fogera shows that 44.2% is arable or cultivable and another 20% is irrigated, 22.9% is used for pasture, 1.8% has forest or shrubland, 3.7% is covered with water, and the remaining 7.4% is considered degraded or other. Fogera has 55 kilometers of dry-weather road and 67 kilometers of all-weather road, for an average of road density of 111 kilometers per 1000 square kilometers.

Based on the 2007 national census conducted by the Central statistical agency of Ethiopia (CSA), this woreda has a total population of 228,449. By gender, the population has held steady in a split of about 51% male to 49% female. With an area of 1,111.43 square kilometers, Fogera has a population density of 205.55, which is greater than the Zone average of 145.56 persons per square kilometer. The woreda is divided into 26 rural kebeles and 5 urban kebeles. A total of 52,905 households were counted in this woreda, resulting in an average of 4.32 persons to a household. The largest ethnic group reported in Fogera was the Amhara (99.83%). Amharic was spoken as a first language by 99.89% of the reported population. Teff, corn, sorghum, cotton, Vegetables, and sesame are important cash crops. Fogera is also known for its breed of cattle. Also located in this woreda is the community of Awra Amba, an Ethiopian grass-roots experiment in egalitarian living.

2.2. Data type and methods of data collection

In this study, both primary and secondary data were used. Both formal and informal survey procedure was used to collect primary data. The formal survey was undertaken through interviews with selected tomato producer farmers using a pretested semi-structured questionnaire. Secondary data was collected from published and unpublished documents, and internet sources.

2.3. Sampling technique and sample size

The study area, Fogera, was selected as a study area since the area has high potential for tomato production and marketing. For sampling producers, two-stage random sampling was used for this study. In the first stage, 3 kebeles (Woreta zuriya, Tiwa and Shina) from tomato growers in the Woreda were randomly selected. In the second stage, the study considered only tomato producer households. Thus, from each sampled kebele tomato producer farmers were listed out with the help of development agents at kebele level (Table ). From these population lists, sample farmers were selected randomly based on probability proportional to size sampling technique.

For this study, the total sample size was determined based on the sampling formula provided by Yamane (Citation1967). The formula used for sample size determination with a 95% confidence level, degree of variability = 0.5 and level of precision 6% (0.06) was:

Where: n = Sample size, N = Population size and e = level of precision

Based on the above formula a total of 235 households were interviewed.

2.4. Method of data analysis

Descriptive statistics and econometric analysis were used to analyze the data collected from tomato producers. Mean, percentages, standard deviation minimum and maximum in the process of describing households’ characteristics. Econometric analysis uses a multivariate probit model to analyze the determinants of market channel choice decisions of tomato producers in the study area because all tomato producers sold tomato though more than two channels.

2.4.1. Multivariate probit model to analyze producers market outlet choice decision

As tomato producers more likely choose two or more than two types of outlets simultaneously in the study area, assuming the selection of different marketing outlets, as well as their simultaneous use, depends on producers’ willingness to maximize their profit and is conditional to socioeconomic, institutional, production, and market-related factors. Following the literature, the researchers concluded that a producers’ decision to sell in an advantageous market derives from the maximization of profit he or she expects to gain from these markets. Econometric models such as multivariate probit/logit, multinomial probit/logit, conditional or mixed, or nested logit are useful models for the analysis of categorical choice dependent variables. A number of studies have been done that have revealed factors influencing marketing channel choice decisions. A study by (Abreham, Citation2013; Mebrat, Citation2014; Ntimbaa, Citation2017; Nyaga, Citation2016) used multinomial logit model to determine factors affecting producers’ market outlet choice decision. Whereas (Abera, Citation2016; Arinloye et al., Citation2015; Efa & Tura, Citation2018; Kiplangat & Vincent, Citation2018; Melese, Goshu, & Tilahun, Citation2018; Nuri, Citation2016; Tarekegn, Haji, & Tegegne, Citation2017) employed multivariate probit model to analyze factors affecting producers’ market outlet choice.

This study undertakes that the farmer’s decision is generated based on its utility maximization. This infers that the alternative marketing outlet choice requires different private costs and benefits, and hence different utility, to a household decision-maker. Hence, farmers will choose marketing outlet if the expected utility from it exceeds that from other marketing outlets such that:

Where, Yi represents the strategy type i, Yj an alternative strategy type j, Vi and Vj the corresponding expected indirect utility values of strategy type i and its alternative j, while Y* represents the strategy type actually chosen. Therefore, we can view the farmer’s decisions on strategy implementation within a random utility discrete choice model. RUM is particularly appropriate for modeling discrete choice decisions such as between marketing outlets because it is an indirect utility function where an individual with specific characteristics associates an average utility level with each alternative marketing channel in a choice set. In this framework, the utility function is assumed to be known for each farmer but some of its components are unobserved by the researcher. This unobserved part of the utility is treated as a random variable. For the ith strategy decision the expected indirect utility is then modeled as the sum of the observed variables and non‐observable random component:

As in Equation (1), we can write the choice utility of implementing any alternative as follows:

Where,

β1i and β1j are vectors of parameters. Hence, farmers can decide simultaneously whether to choose one or more market outlet conditional upon the vectors of explanatory variables Xi and Xj. In this approach, we can use a multivariate probit model (MVP) to study the farmer’s joint‐decisions to market outlet choice.

Following Equations (2) and (3) the empirical specification of MVP takes the form:

With j = 1,2,3,4, 5

Where,

Yi* is an unobservable latent variable denoting the probability of choosing j type of market outlet, for i = 1 (wholesaler), i = 2 (collectors), i = 3 (retailers) i = 4 (consumers) is as follows: Thus, empirically the model can be specified as follows:

Where, Yi1 = 1, if farmer choose wholesaler (0 otherwise), Yi2 = 1, if farmer choose main roadside traders (0 otherwise), Yi3 = 1, if farmer choose retailer (0 otherwise), Yi4 = 1, if farmer choose consumers (0 otherwise), Xi = vector of factors affecting market outlet choice, βj = vector of unknown parameters (j = 1,2,3,4,), and ε = is the error term. To estimate the five Equations (6)–(9) we assumed that the error terms (ε1, ε2, ε3 and ε4) may be correlated. Then, instead of being independently estimated, they are considered to be a multivariate limited‐dependent‐variable model in which the four error terms follow a multivariate normal distribution with zero mean and variance and covariance matrix.

In multivariate model, where the choice of several market outlets is possible, the error terms jointly follow a multivariate normal distribution (MVN) with zero conditional mean and variance normalized to unity (for identification of the parameters) where (μx1, μx2, μx3, μx4) MVN~ (0, Ω) and the symmetric covariance matrix Ω is given by:

Of particular interest are the off-diagonal elements in the covariance matrix, which represent the unobserved correlation between the stochastic components of the different types of outlets. This assumption means that Equation (10) generates the MVP model that jointly represents the decision to choose a particular market outlet (Table ). This specification with non-zero off-diagonal elements allows for correlation across error terms of several latent equations, which represents unobserved characteristics that affect the choice of alternative outlets.

Following the formula used by Cappellari and Jenkins (Citation2003), the log-likelihood function associated with a sample outcome is then given by:

Where ω is an optional weight for observation I and Φi is the multivariate standard normal distribution with arguments μi and Ω, where μi can be denoted as:

3. Result and discussion

3.1. The proportion of producers choosing market outlets

Out of the total sampled households about 74.04 %, 70.21 %, 63.83% and 63.83% of them choices wholesalers, collectors, retailers and consumers market outlet respectively. Based on this result, the tomato producer’s choice of wholesaler’s market channels than other market outlets of marketing the tomato produced in the study areas (Table ).

Table 1. Number of sampled households in each kebele

Table 2. Summary of Hypothesized Independent Variables for MVP Model

Table 3. Proportion of Producers Choosing Market Outlets

3.1.1. The total volume of sale for each channel

In this study, four major tomato market outlets were identified as alternatives to farmers to sell their tomato products. These were wholesalers which account for 30% of total sales followed by retailers (24.74%), collectors (22.9%), and consumers (21.54%) (Table ). Although the role of agricultural cooperatives in smallholder farmers marketing is recognized as vital, no single household reported cooperatives as an alternative market outlet in their tomato products marketing. This should be seen as a serious policy concern for the government and other relevant stakeholders in this sector.

Table 4. Total volume of sale for each channel

3.2. Socio-economic characteristics of tomato producers across tomato marketing channels

The mean and percentage of household characteristics by tomato market outlets are provided in Table below. The mean age of household heads who sold to a wholesaler, collectors, retailer, and consumer market outlets was 39, 40.77, 40.09 and 39.7 years, respectively. The household sold to wholesalers, collectors, retailers and consumers market outlets with an average family size of 2.63, 2.71, 2.65 and 2.58 persons in adult equivalent respectively. The average distance traveled by tomato producers to sold to a wholesaler, collectors, retailer, and consumer market outlets was on average 1.32, 1.38, 1.35 and 1.38 km away from the nearest market away from home respectively. The average land size allocated by tomato farmers that sold to wholesalers, collectors, retailers, and consumers market outlets was 0.33, 0.34, 0.33 and 0.35 respectively. Households who have average livestock size of 5.66, 5.68, 5.76 and 5.65 in tropical livestock unit sold to wholesaler, collectors, retailer and consumers market outlets respectively. The average tomato farming experience of tomato farmers who sold to a wholesaler, collectors, retailer and consumers market outlets 7.86, 8.57, 8.12 and 7.71 years respectively.

Table 5. Producers mean and proportion by socio-economic characteristics across tomato marketing outlets

As indicated in Table , the proportion of the respondents who sold to wholesalers (37.93%), collectors (35.15%), retailers (40%) and consumers (36.67%) market outlets had attending formal and informal education respectively. And transport ownership indicates that 75.86, 64.85, 68 and 72% of market participants choose wholesaler, collector, retailer, and consumer market outlet respectively. This implies that the majorities who sold to wholesaler owned transport facilities. The proportion of households (73.56, 73.94, 81.33 and 74 %) who have access to credit choose assembler, wholesaler and retailer market outlet, respectively. In terms of membership in any cooperative only 6.90, 6.06, 5.33 and 5.33 % of the households were a member and choose wholesalers, collectors, retailers and consumers market outlets respectively.

Results in parenthesis are standard deviations. Source: Own computation of survey data (2018).

3.3. Actors in the tomato supply chain and their roles

Input supplier: Regarding the delivery of inputs like improved seed, herbicide and pesticide, WOA is the main actor responsible for the supply of such inputs in the study area. Development agents are playing a facilitation role in collecting farmer’s input requirements and submitting them to the WOA. They also play the same role during input distribution. Most of the time in the study woreda input suppliers are primary cooperatives who disseminate suitable seed varieties to expand and promote the development of new tomato varieties.

Producers: Farmers produce tomato and sell to wholesalers and local village markets. Out of the total output they produced (7148.35 quintals) the sample households answered that they sold 30.37 % to wholesalers, allow 22.9% to collectors, 24.74% to retailers and 21.49 % to consumer’s market outlet (Table ).

Wholesalers: Wholesalers are market participants who buy large quantities of tomato and resell to other traders. They purchase tomato at the farm gate, from producers in a larger volume than any other marketing actor does from the village market. They relatively spend their full time in wholesale buying throughout the year in and out of the woreda. Each wholesaler uses Isuzu trucks as a transportation vehicle; if the amount of tomato supplied to the market is large. Otherwise, they purchase other vegetable crops like onion together with tomato to fill the truck. The role of brokers was inclined towards buyers. Wholesalers usually get information from friends in Bahir Dar, Debretabour and Gonder and set the daily price. There seemed slight competition among wholesalers but the collusion outweighs.

Collectors: These are traders in assembly markets who collect vegetables from farmers in village markets and from farms for the purpose of reselling it to wholesalers and retailers. They use their financial resources and their local knowledge to bulk vegetables from the surrounding area. They play an important role and they do know areas of surplus well. Collectors are the key actors in the tomato supply chain, responsible for the trading of 22.9 percent of tomato from production areas to wholesale and retail markets in the study areas (Table ). The trading activities of collectors include buying and assembling, repacking, sorting, transporting and selling to wholesale markets.

Brokers: These participants of the system were those who exist between producers and bulk buyers. They did not handle any product but facilitate the buying and selling activities between farmers, wholesalers, roadside traders, and retailers. There are many brokers working in Fogera. These people are not permanent brokers where their main activity is farming in the farming months of the year. It all had mobile telephones. They are divided into urban and rural brokers. The urban brokers who were brokering tomato sometime before are now brokering the only vehicle. These people had the power to suppress the free selling and buying behavior of the farmers. The main activities that brokers usually do were weighing, registering the amount of tomato supplied by each farmer and safeguarding wholesalers. They also served in suppressing grievances of selling farmers at the time of weighing, and another mischief. The rural brokers are area segmented where one or group of brokers in one Kebele would not be allowed to work in other Kebeles.

Retailers: Tomato retailers in Fogera purchase tomato directly from producers and sell to consumers. This is one of the final links in the chain that delivers tomato to consumers. They are very numerous as compared to others and their function is selling tomato to consumers in small volumes after receiving large volumes from wholesalers and producers. retailers are the key actors in the tomato supply chain, responsible for the trading of 24.74 percent of tomato from producers and wholesale to the consumer’s in the study areas (Table ).

Consumers: They are individual households and large consumers like restaurants, hotels, cafe. They buy the commodity for their own consumption. Consumers’ consumption patterns/demand structure, purchasing power, and traditions/norms are assumed to largely affect the potential market for agricultural commodities. From the consumer point of view, the shorter the market chain, the more likely is the retail price going to be low and affordable. In the study, area producers sold 21.49 % of tomato products to the consumers (Table ).

Supportive actors: supporters or enablers provide support services and represent the common interests of the chain operators. They remain outsiders to the regular business process and restrict themselves to temporarily facilitating a chain upgrading strategy. Typical facilitation tasks include creating awareness, facilitating joint strategy building and action, and the coordination of support activities (like training, credit, input supply, etc.) and facilitating the market. The main supporters of the tomato supply chain in the study area are woreda’s Office of Agriculture (WOA), Amhara Credit and Saving Association (ACSI) and Fogera woreda Cooperative Promotion Office through providing inputs and technical advice on tomato production, facilitating credit services, and delivering market information.

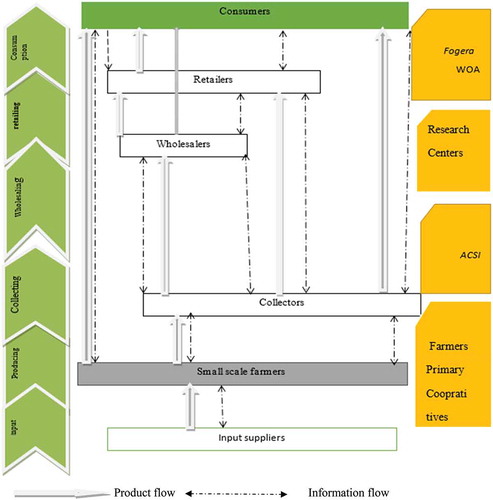

3.4. Tomato supply chain mapping

Tomato supply chain map involves different actors in the tomato supply chain and activities performed by different chain actors. It also shows the flow of tomato production inputs from input suppliers to producers as well as the flow of the product from farmers through different value chain actors to the consumers. There are also information flows regarding the quality and price of tomato among the value chain actors. Figure () shows different levels of tomato supply chain in the study areas. This includes different levels, actors and functions involved in the flow of the product and information flow from consumers to the producers regarding the quality of products they prefer to buy through different actors that help to improve the performance of the chain.

3.5. Tomato marketing channels

Eight (8) main alternative marketing channels were identified for tomato marketing in the study area. From the total tomato product produced in the study sample kebeles,7148.35 quintals of tomato were marketed in different markets in 2017/2018 that supplied by sample respondents. The main marketing channels with the percentage of tomato handled by each actor were identified from the point of production until the product reaches the final consumer through different intermediaries were depicted in Figure . Based on the volume of tomatoes pass through each channel, the channel comparison is performed. Accordingly, Producers—Retailers—Consumers market channel carried the largest volume (1768.75qt) of tomato followed by Producers—Wholesalers—Retailers -Consumers market channel which carried a total volume of 1545qt of tomato.

Channel I. Producers → Collectors→ Wholesalers →Retailers →Consumers (463qt)

Channel II. Producers → Collectors →Retailers →Consumers (918.4 qt)

Channel III. Producers → Collectors →Consumers (57.3qt)

Channel IV. Producers → Wholesalers →Retailers→ Consumers (1545qt)

Channel V. Producers → Wholesalers →Consumers (287qt)

Channel VI. Producers → Retailers → Consumers (1768.75qt)

Channel VII. Producers →wholesalers → out of the region (375.2qt)

Channel VIII. Producers → Consumers (1535.45qt)

3.6. Determinants of market channel choice decision of tomato producers

As depicted in the Table out of eleven (11) explanatory variables included in a multivariate probit model, seven variables significantly affected channel choice decisions of farmers at different levels of significance (Table ). The Multivariate probit model fitness was reasonably good and the explanatory power of the independent variables in the model is satisfactory as indicated by Wald test chi2(44) = 370.49, p = 0.000)) that is significant at 1% significance level. The model is significant because the null hypothesis that the market outlet choice decision of the four tomato market outlets is independent was rejected at a 1% significance level. The likelihood ratio test in the model (LR χ2 (6) = 37.4495, χ2 > p = 0.0000) indicates the null hypothesis that the independence between market outlet choice decision ((ρ21 = ρ31 = ρ41 = ρ32 = ρ42 = ρ43 = 0)) is rejected at 1% significance level and there are significant joint correlations for four estimated coefficients across the equations in the models. This verifies that separate estimation of choice decision of these outlets is biased, and the decisions to choose the four tomato marketing outlets are interdependent for household decisions.

Table 6. Correlation Matrix of farmers’ Market Channels choice for Multivariate Probit Model

Table 7. Multivariate probit estimation results of the determinants of tomato market outlet choice

The age of the household head has a significant and negative relationship with the likelihood of choosing wholesalers market outlets at a 1% significance level. This result shows that an increase in farmers’ age decreases the likelihood of selling tomatoes to wholesalers. This means that older tomato producers prefer selling for another market than wholesaler’s markets. The possible explanation might be that older producers prefer selling for other channels who buy at farm gate than wholesalers. This result is in line with the finding of Nuri (Citation2016) that showed younger farmers have a preference for selling Enset products to the urban markets, while older farmers prefer rural markets.

The educational status of tomato producers has a highly significant and positive effect on the chances of choosing wholesalers and retailers’ market outlets. This result shows that educated farmers would more likely sell tomato to wholesalers and retailers than other channels. This result is consistent with the findings of Abreham (Citation2013) that education level is negatively and significantly related to the collector’s market outlet, thus, households preferred wholesalers market outlet. The possible reason might be that as the education level increases farmer’s productivity increases and strengthen the linkage with wholesalers and retailers. Education increases the knowledge of farmers that can be used to collect information, interpret the information received, and make knowledgeable and marketing decisions.

Market distance has a positive relationship with the likelihood of choosing collectors and consumers channel. This result shows that the increase in distance to the market center would decrease the probability of choosing the wholesalers channel, but increase the likelihood of choosing the collector’s consumer channel. This is due to the fact that most producers prefer to sell their products at the farm gate without incurring transaction costs. Selling tomato products to wholesalers requires transporting the product to urban markets where they are buying the products. As a result, producers prefer to choose collectors and consumer channels to deliver their products at the farm gate as compared to selling to wholesalers. This result is in line with Abera (Citation2016), Arinloye et al. (Citation2015) and Tarekegn et al. (Citation2017); found that market distance has a positive relationship with the rural market and negative relationship with urban markets.

Owning transport facilities influenced the choice of wholesalers and consumer outlets positively and significantly at a 1% significance level. Transport facilities ownership by farmers increased the likelihood of choosing wholesalers outlet. This might be due to the reason that farmers who have transport facilities could supply their product to urban centers and sale to wholesalers and consumers directly by getting better prices which might go to the collectors. This shows that the availability of transportation facilities helps reduce long market distance constrain and offering greater depth in marketing choices. This result also in line with Temesgen, Gobena, and Megersa (Citation2017) who found that owning a transport facility influenced the collectors market outlet negatively.

Access to credit has a positive and highly significant effect on households‟ choice of wholesalers, collectors, retailers, and consumers market outlet at a 1 % significance level. Access to credit would enhance the financial capacity of the farm households to purchase the necessary materials and increases output. The possible reason might be that farmers require finance to buy necessary inputs for tomato production, to produce on a large scale, and hence sale to all channels from his/her large produces. This result is consistent with Efa and Tura (Citation2018), found that obtained credit has a positive and significant effect in retailers market outlet. The result also in line with Melese et al. (Citation2018) found that access to credit has a positive and significant effect on choosing assemblers market outlet for marketing onion.

Household size was positively and negatively influencing the collectors and consumer market outlet choice of tomato producers at a 10% significance level respectively. The reason might probably be due to larger land demand for food crops like cereals as a household hosted larger family size. And they allocate small area for tomato production and sale their small quantity of tomato produces for collectors. As can be understood from the results, the probability to choose consumers channel decreased when the number of the family increased. This result is in line with Temesgen et al. (Citation2017) and found that as the number of families increased, the probability to participate in onion production decreased. Contrary to this Efa and Tura (Citation2018) who indicated that large family size enables better labor endowment so that households are in a position to travel to get wholesalers in the district or nearby town markets. And also the result contradicts Chala and Chalchisa (Citation2017) indicate that the more family size helps to supply vegetables to different retailer shops, restaurants, and kiosks in different units which affects to operate vegetable production.

Land size: Producers who have allocated more land for tomato production would obtain a larger quantity of tomato. The size of land allocated for tomato influenced the choice of wholesalers and consumers outlets positively and significantly at a 10% significance level. An increase in land allocated to tomato increase the likelihood of choosing wholesalers and consumer channels. In other words, farmers with more land holding, produce large amounts and they prefer to sell this large amount to wholesaler and consumers channel.

4. Conclusion and recommendations

The study was undertaken with the objective of characterization and analysis of the supply chain of tomato at Fogera woreda, South Gondar, Ethiopia. Tomato supply chain analysis in the study areas revealed that the main actors are input suppliers, tomato farmers, collectors, wholesalers, retailers, and consumers.

Regarding tomato products flow, the main receivers from producers were wholesalers, collectors, retailers and consumers with an estimated percentage share of 30.8732%, 22.9 %, 24.74 and 21.49 %, respectively. There are various factors that affect farmer’s choices of tomato market outlets. The channel alternatives in the tomato value chain which are available to tomato producers include collectors, wholesalers, retailers, and consumers.

The results of the multivariate probit model showed that the likelihood of choosing wholesaler marketing outlet was affected by age of the household head, educational status of the household head, ownership of transportation facilities and access to credit. The probability to choose the collector outlet was significantly affected by distance to the nearest market, household size and access to credit. The probability to choose the retailer outlet was significantly affected by the educational status of the household head and access to credit. Household size, distance to the nearest market, own transportation, and access to credit affected the likelihood of choosing of consumer’s market outlet. Accordingly, expanding the accessibility of infrastructures such as road and transportation facilities need government intervention to promote the effective marketing of tomato through all outlets.

Acknowledgements

The authors express special gratitude to the BDU-IUC Program and Ministry of Education for the research funding. My extended gratitude also goes to enumerators for their support in data collection and farmers for their cooperation during the survey.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Hawlet Mohammed Kassaw

Hawlet Mohammed Kassaw holds a bachelor’s degree in Agricultural economics from Bahir Dar University, Ethiopia in July/2015. Immediately after graduation, she was employed in Bahir Dar University College of Agriculture and Environmental science particularly the department of Agricultural Economics in August 2015. Then she has served in the College as a graduate assistant. After she served for one year, she got the chance to study M.Sc. degree in Agricultural Economics at Bahir Dar University College of Agriculture and Environmental Science by the Department of Agricultural Economics. Now she holds a master’s degree in agricultural economics in July/2019. Now, she is a lecturer at Bahir Dar University. Impact and adoption analysis, gender-related analysis, value chain, and supply chain analysis, sustainable livelihood analysis, and economic valuation are the author’s interest areas of research.

References

- Abera, S. (2016). Econometric analysis of factors affecting haricot bean market outlet choices in Misrak Badawacho District, Ethiopia. Ethiopian Institute of Agricultural research, 2(9), 6–20.

- Abreham, T. W. (2013). Value chain analysis of vegetables: The case of Habro and Kombolcha woreda in Oromiya Region, Ethiopia (M.sc. A thesis). Presented for Haramaya University, Haramaya, Ethiopia. p. 144.

- Addisu, H. (2017). Determinants of volume sales among smallholders potato farmers in Ejere District, West Shoa Zone, Oromia Region of. Journal of Economics and Sustainable Development, 8(5), 87–95.

- Arinloye, D.-D. A. A., Pascucci, S., Linnemann, A. R., Coulibaly, O. N., Hagelaar, G., & Omta, O. S. (2015). Marketing channel selection by smallholder farmers. 21(4), 337.

- Bezabih, E., & Hadera, G. (2007). Constraints and opportunities of horticulture production and marketing in Eastern Ethiopia. DCG Report No.462, (46). doi:10.1094/PDIS-91-4-0467B

- Cappellari, L., & Jenkins, S. (2003). Multivariate probit regression using simulated maximum likelihood. The Stata Journal, 3(3), 278–294. doi:10.1177/1536867X0300300305

- Chala, H., & Chalchisa, F. (2017). Determinants of market outlet choice for major vegetables crop : Evidence from smallholder farmers ’ of Ambo and Toke-Kutaye Districts. West Shewa, 4(2), 161–169.

- CSA. (2015). CSA (Central Statistical Agency). 2015. Large and medium scale commercial farms sample survey results. Volume VIII: Statistical report on area and production of crops, and farm (Private Peasant Holdings, Meher Season). Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Author.

- Efa, T. G., & Tura, H. K. (2018). Determinants of tomato smallholder farmers market outlet choices in West Shewa, Ethiopia. Journal of Agricultural Economics and Rural Development, 4(2), 454–460.

- FAOSTAT. (2009). FAOSTAT (Food and Agricultural Organization Statistical Division). 2009. Preliminary 2008 data for selected countries and products Retrieved from http://faostat.fao.org/site/567/PageID=567#ancor

- Fentie, M. B., Goshu, D., & Tegegne, B. (2017). Determinants of potato marketed surplus among smallholder farmers in Banja District, Awi Zone of Amhara Email address. International journal of agricultural Economics, 2(4), 129–134.

- Kiplangat, N. E., & Vincent, N. (2018). Farm gate dairy milk marketing channel choice in Kericho. 7(3), 92–104. doi:10.11648/j.jwer.20180703.11

- Mebrat, T. (2014). Tomato value chain analysis in the central rift valley: The case of Dugda woreda, East Shoa zone, Oromia National regional state, Ethiopia (M. Sc. Thesis). Haramaya University, Haramaya, Ethiopia.

- Melese, T., Goshu, D., & Tilahun, A. (2018). Determinants of outlet choices by smallholder onion farmers in Fogera district Amhara Region, Northwestern Ethiopia. Journal of Horticulture and Forestry, 10(3), 27–35. doi:10.5897/JHF2018.0524

- Ministry of Finance and Economic Development (MoFED). (2011). Macro-economic development in Ethiopia. Annual report. Addis Ababa. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences.

- Ntimbaa, G. J. (2017). Factors influencing choice decision for marketing channels by coffee farmers in Karagwe District, Tanzania. Global Journal of Biology, Agriculture & Health Sciences, 6(2), 1–10. doi:10.24105/gjbahs.6.2.1701

- Nuri, L. T. (2016). Value chain analysis of enset (Ensete ventricosum) in Hadiya Zone. Southern Ethiopia.

- Nyaga, J. (2016). Factors influencing the choice of marketing channel by fish farmers in Kirinyaga County. Ageconsearch.Umn.Edu. Retrieved from http://ageconsearch.umn.edu/bitstream/249338/2/284.FishfarminginKenya.pdf

- Tarekegn, K., Haji, J., & Tegegne, B. (2017). Determinants of honey producer market outlet choice in Chena District, southern Ethiopia: A multivariate probit regression analysis. Agricultural and Food Economics, 5. doi:10.1186/s40100-017-0090-0

- Temesgen, F., Gobena, E., & Megersa, H. (2017). Analysis of sesame marketing chain in case of Gimbi Districts, Ethiopia. Journal of Education and Practice, 8(10), 97–101. doi:10.4314/eamj.v78i2.9097

- Willcox, J. K., Catignani, G. L., & Lazarus, S. (2003). Tomatoes and cardiovascular health. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrient, 43, 1–18. doi:10.1080/10408690390826437

- Yamane, T. (1967). Statistics; An introductory analysis. (2nd ed.). doi:10.2307/2282703

Appendix 1. Conversion factors used to compute adult equivalent

Appendix 2. Conversion factors used to compute tropical livestock units (TLU)

Appendix 3. Error covariance matrix and correlations of the MVP model