Abstract

Culture plays a significant role in protecting the environments and critical ecosystems. The purpose of this study was to explore the relevance’s of indigenous beliefs, sacred sites, cultural practices and traditional rules (seera) in promoting environmental conservation and sociocultural values. The study further addresses the cultural interconnection between plants and people (ethnobotanical myths of Gedeo). The study employed broadly a qualitative approach with an anthropological design. The study was used key informant interviews, focus groups, participant observation and descriptive ecological inventory. The results revealed that, songo indigenous institutions, traditional beliefs, taboos, and local rules (seera) have been playing an enormous role in promoting environmental protections and cultural conservation. The setting aside sacred forest for ritual purposes also well entrenched traditions as indigenous mechanism of tree biodiversity conservation. Due to the prohibition systems (taboos), traditionally protected area (e.g. amba sacred forest) has highest tree diversity and well preserved than adjacent non-sacred farming habitats. Social taboos as indigenous belief systems have limiting people from cutting down trees from sacred sites, killing birds and injuring nature carelessly. Trees in sacred forest were not axed except when it is needed for public uses like local bridge constructions and chopping its woods for ritual purposes with consent of cultural elders. Broadly speaking, these cultural practices and prohibition mechanisms informally enhance ecosystem conservation and protection via limiting local people from destroying nature carelessly. Hence, due to the banishment, the sacred forest havens critical threatened plants or trees not found elsewhere special in non-sacred farming habitats. For instance, Aningeriaadolfi-friedeicii, Podocarpus falcatus, Cordia africana, Prunus africanum, O. welwitschii, and Syzygium guineense native tree species were abundantly counted in sacred forest while critically threatened in non-sacred adjacent landscape. The current study concludes that indigenous knowledge (IK) expressed through local practices, indigenous beliefs, social banishment, customary laws (seera) and prohibition systems is very useful tools in conservation of degraded tropical ecosystems and resilient for adverse climate change. In contrast, religious monotheism, changes in social norms, erosion in ancestral beliefs and lack of proper documentation of IK were some of the main factors that contributing towards the degradation and erosion of indigenous mechanisms of environmental protections which need to be looked into and formal law enforcement should be needed to safeguard the sacred forests.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Indigenous knowledge (IK) plays a significant role in promoting environmental conservation, natural resources, food security achievements and protection of critical threatened ecosystems. The nature-culture nexus has attracting a great attention in promoting the conservation of sacred natural sites and remnant natural forests. Indigenous society and their old-dating knowledge has playing an enormous roles in sustaining food productions, natural resources, climate change mitigation and providing the resilient ways in halting environmental degradation. The current research reports on the indigenous ways of environmental protection and traditional beliefs in promoting tree biodiversity conservation and cultural values in Gedeo, Southern Ethiopia. The research is emphasizing on the worldviews, traditions, myths and ethnobotanical perspective of local communities. On the other hand, the research also addresses the endangerment of sacred sites, IK, and indigenous belief systems due to the various human influences and modernization. The research is significant in that it contribute in global level in promoting the conservation of sacred natural places, biodiversity and natural resources.

Competing Interests

The author declares no competing interests.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background of the study

Biodiversity conservation is vital for all living organisms due to its social, economical, ecological and global importance (Millennium Ecosystem Assessment [MA], Citation2005). Conservation of environmental resources is a wise use of the earth’s resources by humanity (IUCN (World Conservation Union), Citation2008). It is the management of valuable and critical ecosystems such as timber, fish, topsoil, pastureland, minerals, forests, watershed areas and wildlife (MA, Citation2005; IUCN (World Conservation Union), Citation2008). These critical ecosystems are bases for all life on the planet including human beings. However, year after year, scientists release statements stating the earth has seen a new record setting-level of carbon emissions, adverse environmental degradation’s, and biodiversity loss (Cook et al., Citation2013). This is not new news, however, but the implication of failing to address this issue is becoming exponentially more serious. Such record emissions for life on earth have already been detrimental in the form of species extinction, degradation of natural resources, and large-scale environmental deterioration (MA, Citation2005; Oksanen et al., Citation2010). For instance, with carbon emissions reaching a total of 402 ppm and growing, it is crucial to motivate others to acknowledge and act on these environmental issues (Cook et al., Citation2013). In view of this, the rapid decline in biological diversity—(species, ecosystems, forests and genetic resources)—is one of the critical challenges of the twenty-first century (Fonjong, Citation2008). As environmentalists, scientists, and policymakers continue with the debate over the causes and solutions to halt destruction and outright depletion of the environmental resources.

As evidenced from various scholars, the current increasing rate of natural resource degradation and species loss is a major adversely effect to human being as well as all life on the earths. The loss of each species in ecosystem comes with the loss of economic benefits, and social well-beings in many rural people (Attuquayefio & Gyampoh, Citation2010). For example, the forest ecosystems have recognized as resilience’s for climate change mitigation and income generation among the rural poor (FAO, Citation2008; Messier et al., Citation2013; Paquette & Messier, Citation2010). Many scholars also supported that ecosystems like forest and trees within such habitats are balancing global warming, provide income diversification, recycle water resources, and make refugees for million of species (MA, Citation2005; IPCC, Citation2007; BIE, Citation2014). However, an alarming environmental degradation and anthropogenic activities currently heavily degrading forest resources (MA, Citation2005). According to the IUCN the current loss rate of forest ecosystems including wildlife is described as “crisis” and “great extinction” unless the efforts made to halt (IUCN (World Conservation Union), Citation2008; FAO, Citation2014).

Today, there is an urgent need for conservation and preservation of the remnant NRs and forest biodiversity (IUCN (World Conservation Union), Citation2008; FAO, 2011). In fact, since time immemorial the conservation of environmental resource and ecosystems are an integral part of human culture. Indigenous communities, all over the world lived in harmony with the nature and conserved valuable biodiversity surrounding them (Appiah-Opoku, Citation2007; Dudley et al., Citation2009; Oksonen et al., Citation2010). In fact, currently, the governments of various countries and organizations have enacting formal laws and police to halt the rate of environmental degradation (Ikyaagba et al., Citation2015). However, these formal mechanisms of NR conservation’s and protections have not yet halted the degradation. But, before the introduction of modern forms of conservation approaches, indigenous communities often have developed elaborative and local resilient practices associated with conservation and management of environmental resources (Kideghesho, Citation2009; Dudley et al., Citation2009; McCarter and Gavin, Citation2011; Turnhout et al., Citation2012; Toledo, Citation2013). Apart from the formal laws and policies, indigenous people have been used their IK and customary laws that have used for conservation and protection of remnant NRs (Endalkachew (Citation2015); Verschuuren et al., Citation2010).

For instance, the African beliefs and taboos helped in enforcing rules and regulations for environmental preservation and conservation because people refrained from using environmental resources carelessly, especially as it is related to sacred places, forests and reverenced wildlife areas (Appiah-Opoku, Citation2007; Adu-Gyamfi, Citation2011; Ryser, Citation2011; Toledo, Citation2013). In traditional protected areas, trees, wildlife or plants are safeguarded because of their sacredness or spiritual significance’s to custodian communities (Dudley et al., Citation2009; Mascia et al., Citation2014). In view of this, due to the spiritual significance’s, sites, plants or entire forests are protected (Maffi & Woodley, Citation2012). These traditional protected areas can outnumber legally conserved areas in some tropical countries and in some cases are more effective at sheltering endangered plant species than legally conserved areas (UNESCO, Citation2003; Maffi, Citation2005, Dudley et al., Citation2009). These traditional maintained sites also important for preserving cultural diversity (Bhagwat & Rutte, Citation2006) and offer opportunities for the conservation of tropical biodiversity (Cardelu´s et al., Citation2012). The traditional taboos helped in enforcing informal rules and regulations of sacred natural sites preservation (Adu-Gyamfi, Citation2011; Bhagwot, Citation2004). These taboos or traditional beliefs make the local people to abstain from harming forest resources carelessly, especially as it is related to religious sites (Bhagwat, Citation2011; Dickson et al., Citation2018). Adu-Gyamfi (Citation2011) argues that the indigenous practices are more environmentally friendly approaches and better protect biodiversity than the western paradigms of conservation approaches.

In fact, the spiritualities among the indigenous people which are largely made up of a body of beliefs, values and respects intimately connected to the surrounding biodiversity and environments (Mallarach, Citation2006; Verschuuren et al., Citation2008; Verschuuren and Brwon, Citation2018). This spiritual connection with nature cosmos is manifested by setting aside certain areas as SNS (i.e., woodlands, water points, mountains, forest, and certain animals as totemic species). These sacred areas have maintained for cultural purposes and they are not to be abused and destroyed carelessly due to its sacredness and reverences (Pungetti et al., Citation2012). For example, sacred forests across the world are conserved primarily for spiritual reasons (Frascaroli, Citation2013). Harming this sacred forest is forbidden by tradition of indigenous tribes and it is typically believed that any alteration of the forest, such as cutting wood for construction or firewood, hunting animals or other forms of resource extraction, could result negative consequences to the offenders (Barre et al., Citation2009).

In context of Ethiopia, the country is considered one of the most important biodiversity hotspots of the world, but also one of the most degraded country in tropics (BIE, Citation2014; FAO, 2011). In contrast, the country has a rich mix of ethnic, religious and mosaic cultural groups with diversified social, political and economic organizations. In Ethiopia, since several decades there has been progressive degradation of ecosystem resources. The rate of deforestation in Ethiopia, which amounts to 163,000–200,000 ha year−1, is one of the highest in tropical Africa (EFAP, Citation1993). It has been a major problem for quite a long time with serious consequences to the country. These consequences includes, declines in soil fertility and water quality, loss of biodiversity, drought, poverty, loss of wildlife, and land bareness particularly in highland area (BIE, Citation2014; Heide, Citation2012; Mulugeta, Citation2004). In other side, the farmers of the country have well known and time tested IK, mosaic ecological knowledge and traditional ways of natural resource conservation and management (e.g. Konso indigenous soil and water conservation [terracing], indigenous Agroforestry system of Gedeo community, coping strategies of Borena and Afar pastoralist, traditional healing practices both human and animal health, seed identification knowledge and food production systems in many rural area) (SLUF, Citation2006; Ayal et al., Citation2015; Ocho, Citation2012). But, IK of local people has been marginalized for centuries and it has not been in the attention of scholars and government (Paula, Citation2004; Wild et al., Citation2008; Ulman and Mokal, Citation2009; Rim-Rukah et al, Citation2013). Hence, low attention has been given for IK especially in environmental conservation and protections area in the era of environmental degradation (Tanyanyiwa & Chikwanha, Citation2011).

In the context of biodiversity conservation, for example, the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahido Church is one of the oldest Christian churches in Africa and has a long history of protecting and preserving indigenous forest as sanctuaries for prayer and burial grounds. In a general sense the forests surrounding churches are seen as sacred, with the trees symbolic of angels guarding the church. These spiritual dedicated forests are an integral component of the church as they provide sites for religious ceremonies, social gatherings, and burial grounds. These church forests are, therefore, regional biodiversity hotspots and showcases for remnant vegetation and wildlife (Bongers et al., Citation2006). Apart from church forest, there are many cultural and sacred landscapes that setting aside for ritual or religious purposes (Doffana, Citation2014). For instance, the sacred natural sites such as Wonsho of Sidama and Caatoo of Horro Guduru Wollega are socially conserved and respected sites which could have sociocultural and environmental importance in Ethiopia (Doffana, Citation2014; Doffana, Citation2017; Lemessa, Citation2014). In Guji land, there are also many sacred natural areas identified for different traditional rituals since time immemorial (Gemeda, Citation2018). Like other sacred forests, Ethiopian sacred forests have exhibited remarkable resilience in the face of disturbance and environmental degradation (Cardelu´s et al., Citation2012). Therefore, this research was conducted in Gedeo, because no researches have been conducted in biocultural diversity and sacred natural sites in terms of biodiversity assessments. Hence, the current study was intended to understanding indigenous ways of environmental conservation and its relevance’s in protecting the surrounding biodiversity and cultural landscapes. The paper further investigates the socio-ecological perspective of sacred natural sites and the role of traditional beliefs, norms, taboos, myths, and traditions in conservation of environments.

1.2. Objective of the study

The main intend of the current study was to better understanding the IK practices and its relevance to NR conservation among the Gedeo community. Further, the paper aimed to assess the worldviews, indigenous beliefs, and environmental ethics of Gedeo, associated with biodiversity conservation. More specifically the study was focused:

To assess the Gedeo myths, indigenous institutions, and traditional rules (seera) associated with environmental protections

To investigate tree biodiversity conservation potential of sacred forest and its sociocultural significances

To describe the major factors that contributing for erosion of traditional ways of environmental protection and endangerment of sacred natural sites

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Description of the study area

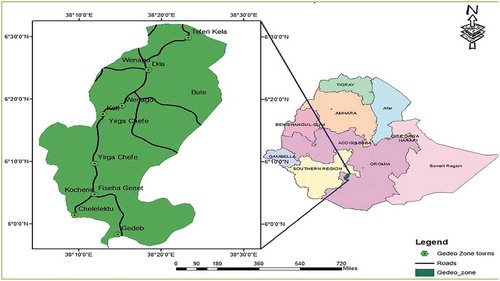

The study was conducted in the Gedeo zone (Gedeo community) which is located 369 km from the capital city of Ethiopia, (Addis Ababa), and 90 km from the regional capital (Hawassa), to the south on the main highway from Addis Ababa to Moyale toward Kenya (Figure ). Administratively, it lies in the South Nation Nationalities and People Regional State (SNNPRS) (Southern Region of Ethiopia) one of the nine self-administering regions in Ethiopia. Geographically, Gedeo zone is located north of the equator from 5°53ʹN to 6° 27ʹN latitude and from 38° 8ʹ to 38° 30ʹE longitude (Negash, Citation2007; Negash, Citation2010). The altitude ranges from 1500 to 3000 m above sea level. The Gedeo zone is part of the inter-tropical convergence zone (Tadesse, Citation2002) and experiences annual rainfall in the range of 800–1800 mm and the mean annual temperature varies from 12.5°C to 25°C (Negash et al., Citation2012).

The Gedeo highland receives both equatorials and monsoons, the two most important trade winds in the region (Tadesse, Citation2002). It is situated in the Rift Valley in Southern Ethiopia. The Gedeo community shares boundaries with the Oromia regional state in the East, West and South, and Sidama zone in the North. The total area of the zone is 134,708 ha (GZFD, Citation2009). According to the current government administrative division, the zone consists of six woredas (districts) and two administration towns (Figure ).

2.2. Materials and methods

This study was ecological descriptive and it employed broadly qualitative methods and the methodological goal was to gain an in-depth understanding of the perspectives of local people with help of an anthropological approaches (Creswell, Citation2013). The design for data generation and analysis broadly followed a mixed-methods model, whereby an assortment of qualitative and semi-quantitative data collection and analytical tools were employed. Data were produced through in-depth interview, focus group discussion, participatory observation, and transect walk. In addition to this, ecological descriptive inventory mechanism was used to count tree biodiversity in sacred forest patch and adjacent non-sacred farming habitat. In-depth interview was made with community elders, practitioners of the baalle system (traditional administration wings), songo cultural elders (hayyichuwwa), and experts of Culture and Tourism offices of Gedeo zone. The focus group discussions were made with people surrounding the sacred forest, practitioners of the baalle system, village elders (lolinixxa gedhee), young people, chief of local institutions and community elders in Yirgacheffee, Wonago, Dilla_zuriya and Bule districts. The points of discussion were the experiences and origin of traditional ways of preservation sacred sites, sacred forest and overall conservation traditional prac of environmental resources.

Another form of data collection technique used in the study was transecting walk in which I made an intensive and rigorous of observation and informal discussion with local community elders, youth, and village head to grasp the local knowledge of biodiversity conservation and environmental protection. This had been used to practically observe the origin of sacred natural sites, indigenous belief system associated with surrounding sacred natural sites. Local informants representing various socio-demographic categories as well as interviewees representing organizational bodies across the spatial scales were recruited on the basis of their relevance to the study problem. Referral or snowball sampling was employed to identify and interview informants (particularly at local scale) who commanded important influence and were reported as holders of valuable information but were hard to identify. The household survey was administered by deploying, under the supervisorial role of my research assistant and myself, six trained data collectors.

In addition to the socio-cultural data, the determination of tree inventories was conducted by taking a representative sampling main pilots in sacred forest and adjacent non-sacred habitats to understand the conservation potential of threatened ecosystems. Hence, to understand tree conservation statuses of sacred forest total of (20 × 20 m) 400 m2 quadrant, was laid down for tree assessments and counts both in sacred and non-sacred adjacent habitats.

In this regard, within each quadrant, tree species greater than 10 cm diameter at breast height (DBH) was enumerated and recorded. Identification of tree species was done with the help of local communities, published floras and other available literature. Conservation practices, belief system and socio-cultural significance’s of sacred forest was discussed with local inhabitants residing within and around the vicinity of the sacred forests. The endangered or threatened trees was assessed and listed by using the local developed criteria (Bekele et al. Citation1999 and Magurran Citation2004), local reported researchers criteria and International Union of Conservation of Nature (IUCN) red list of threatened species (also known as the IUCN red list or red data list of Ethiopia and Eritrea).

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Myths of Gedeo environmental protection

The Gedeo have a rich culture and IK that fosters environmental conservation, hard-working and well mannered social principles (seera). In this context, the researchers observed that, Gedeo people have well established local knowledge of environmental protection and conservation since time immemorial. Mythical, they perceived themselves as part of nature and all creature on the planet including human beings are signifying the spectacular works of “Magenno” which is equivalent to creator God. The traditional Elders confirmed that:

Gedeo believes in Magenno (sky God), the one and only one Supreme Being. “Magenno” is believed to be manifested Himself in His works of creations such as mountains (kobba), hills, forests, rivers, large trees and other natural landscapes. They were further stated that nature is regarded as legitimate intermediaries between creator sky God and people.

Gedeo have great respect for nature and it revered as elderly men and women because nature recognized as intermediaries between “magenno” (creator God) and man. According to the cultural elders, it is playing an enormous role in revealing a great wisdom of sky God (magenno). Thus, nature like mountains, hillsides, trees, riversides (anish manjjo), rivers and forest patches are serves as bridges that connect the creature (Man) with God (creator). According to the myths of forebears, the protection of such natural sites or places is the way of expressing the human desire and prayers to Supreme Being (Magenno) via reverences and protection. The cultural elders, notifying the name of mountain (koobba daadette maggenni), sky God (samayee daadette magenni), elderly clans (gossatti magenni), sacred forest patches (ambi magenni) while they praise or prayer their sky God. This is why of expressing admiration of sky God for his miracles creature and works. Mythical, Gedeo person has obligation to care, respect and protect nature including domestic animals in acceptable manners and proper exploitation since time immemorial. In Gedeo traditional rules (seera) in general, the plants, animals, wildlife, trees, birds, forests, and other ecosystems are the part of nature, which is belonging to the creator sky God (magenno) and it should deserving to be respected as much as human beings who are also part of nature. This was also supported by the findings of Henshey (Citation2011); he point out that in traditional African societies, many tribes believed that rocks, trees, streams, ponds and forests were the manifestation power of the Supreme Being and places of reverences for sociocultural aspects.

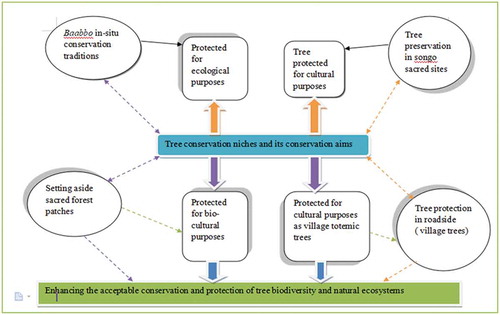

Basically in Gedeo cosmology, nature is regarded as the legitimate intermediaries between creator God (magenno) and human-beings. Particularity, nature like land is a basic and most crucial resource among the Gedeo traditions. In Gedeo worldviews, land is believed to be home to many sacred natural sites, living things, and havens niches for various trees, plants and wildlife which protected and preserved as economic and sociocultural well-beings. According to Gedeo elders, there is strong relation between Gedeo “traditions” and “Land” ownership. Land is the most valuable resource among the Gedeo and it cannot be considered as marketable and exchangeable commodity. That is why every Gedeo families have strong believes that land is the basis of their livelihoods, culture, and traditions. Thus, all natural resources upon it such as trees, forests, cultural landscapes, birds, wildlife and natural ecosystems are basically protected and revered for cultural purposes apart from its economic needs (Figure ).

3.2. The “Seera” as basic traditional rules and environmental protections

Most popular of all, the discussion conducted with community elders reveals that, the co-existence of Gedeo people is established on the long stand rules (seera) of norms, and respects of elders and their oral declaration that passed from generation to generation. Particularly, respect is an important social values among the Gedeo community. Though often this respect is limited to the elderly men and generally to humans, understanding from our discussion on the nature reverence reveal that the value of respect is intended towards all creations including domestic animals and surrounding nature. The respect is often seen in the form of reverence aspects of environmental resources because of their association with the traditions and relation to the human beings. For instance, songo sacred trees are often seen as ritualistic trees which maintained and protected by prohibition systems (taboos) and traditional rules of “seera”. In the mores of Gedeo, respect is translated into attitudes such as respecting elder person in villages, not cutting songo sacred trees (Dhadacha), not injuring sacred forests, not felling young and immature plants from farms, not cutting grave trees for house uses, killing birds which is serious sins and burying animals dead body as human beings, murdering of human-being, defecation in sacred natural sites, degrading the reputation of cultural elders and mass-cutting of trees (degradation) from indigenous cultural landscapes (agroforestry) have been accepted as disrespectful deeds and perjuring of ancestral rules “seera”.

In sum, the natural resources like “Land” is regarded as an essential life provider and dwelling places for all life on the earths and perceived as natural gift of Creator God (Magenno) to their ancestors and it should protected through generation via acceptable manners and norms. For such reasons, all natural resources (such as trees, forests, plants, vegetation, animals, and birds) within the “land” should be conserved and protected without the damage caused to them through human activities. This is also similarly acknowledged by (Eneji et al., Citation2012) for traditional Africans, land and water are very precious gifts from God and it has provided the particular care and proper management for them. That is why every Gedeo family has accepted as land is the basis of economic and values for sociocultural well-being. Regarding the ownership, in Gedeo traditional norms (seera), there is no personal or private land ownership rights, “Land” is belongs to public so called “yaa’a”. Yaa’a is a group of people who have shared common values, norms, identities, and beliefs within community. This group of people has governed by traditional rule of “seera”. In view of community elders, “seera” is unwritten traditional rules (laws) that govern and guide individual person or entire people how to use, conserve, interact, and respect the surrounding nature and it has shape the individual behavior how to co-exist friendly with environmental resources and human beings each other. In all circumstances, these unwritten rules or “seera” have compelled individual person to obey to all rules and regulations that associated with human-nature interactions and sociocultural norms in general. Traditionally, “seera” is emanated from baallee systems and enforced by songo indigenous institutions and its cultural elders.

3.3. Indigenous baallee traditional administration systems and its sociocultural values

Ballee as a system of administration has its own principles and philosophy that used to regulate the people and nature. The Gedeo “Ballee” system is divided into three administrative stages known as “Rogas.” These are the Suboo, Riqataa, and Dhiibataa. While each of these is presided over by the “Roga” they will be accountable to the Abaa-Gadaa. Abaa-Gada is a traditional leader of Gedeo people and at the same time a leader of Ballee administration system. He has been elected from two clans Liikko and Logoda. Each clan administers for 8 years and after 8 years new Gadaa will be born with warm ceremony. As stated by cultural elders, the Gedeo people maintain their expensive values, economy, norms, cultures and heritages by establishing their own Baalle system which similar to the Gada system of the Oromo. Baallee has functioned as a system of traditional administration to date and passed through out of generation. Traditionally, the cultural rules (seera) that regulate the overall sociocultural activities of Gedeo people are formulated by baallee traditional systems and all social rules emanated from baallee traditions and enforced by songo social institutions and its cultural elders.

As evidenced from community elders, social institutions like songo and baallee traditional systems are particularly a decisive culturally structured and solidified institutions of preserving and protecting the natural resources, social values and cultural landscapes among the Gedeo. For instance, the traditional rules (seera) have proclaimed by Aba-Gada at annual thanksgiving ceremonies (daarrarro) and the oral proclamation of abaa-gadaa includes sociocultural regulations, peace and security, environmental issues and about the preservation of native trees in all niches (Figure ) and preaching social co-existences. For instance, in annual ritual ceremonies, aba-gada has announced the local proclamation to yaa’a (oral declaration) local called “lalabbaa” to preserve native trees, and not to cut century-old big trees in the villages such as Pouteria adolfi-friedericii, Cordia africana, Ficus elastica, Ficus gnaphalocarpa, and Podocarpus falcatus. These native trees are highly degraded in farming landscapes and they are only found in ritual sacred sites. Furthermore, Aba-gada has the responsibility and spiritual power of preaching about the peace, cohesion and social co-existences among the people.

3.4. The values of respects among the Gedeo

Accordingly, under rules of traditional “seera” the ethics of care and respect is essential tool to traditional understanding of environmental protection and conservation of nature in the contemporary world. As a evidence, in the mores of Gedeo, the value of care implies not “hurting” the nature carelessly, respecting for cultural elders, and obliged to ancestral norms and not doing social seized actions. Over exploitation of any forms of nature, and perjuring the traditional rules (seera) associated with environmental conservation and social values shows the absence of care and untruthfulness to governing rules. The offender is traditional punished by cultural elders for perjuring the “seera”. Traditional elders revealed that:

The value of care obliges us not to harm the natural environments and the value of reciprocity imposes an obligation on humankind to protect and repair the damage caused to nature through human activities and this cultural accepted norm is highly appreciating the intensive care and proper nurturing of surrounding environments. They further stated that, traditional prohibition systems (taboos) has guided individual person in discouraging cutting trees from sacred natural sites such as sacred forests, graveyard, songo sacred sites (Dhadacha) and mass-cutting of baabbo trees from indigenous farming landscapes.

3.5. The traditional beliefs associated with animal conservation and protection

More evidently, the discussion held with Gedeo elders reveals that, apart from conservation of trees, plants and other ecosystems, Gedeo have due respect to their domestic animals and wildlife. This can be observed by their gifting the grass so called Gorassanjjo to ram (heifer) before slaughtering for foods. This is the way of escaping and cleaning themselves from sins of killing (slaughtering) live animals for foods despite that the God is allow them for feasting. It is come up with their prayers and praise to creator God (magenno) before slaughtering the ram for food because God is believed to be being creator of all nature. From practical discussion with cultural elders, begging, theft, adultery, putting to death pregnant animals and killing a person is highly discouraged and accepted as social an evil actions among the Gedeo traditions and the offender could punished in the forms of various calamities (ill-lucks) such as death, infertility, death at birth, social exclusion (muuniddoo), humiliation, and disease. For this reason, the Gedeo have common believe that, creator (God) has gave rights as well as responsibilities to human beings to use, care and not to hurt the nature carelessly. Similarly, from the biblical point of views, in first page of Genesis 1: 26, in the story of creation God gave man an order, so fiat an authority to rule over the whole world. He gave man the authority to keep down the earth, all the creatures of earth and all resources upon it.

More evidently, there is also common believes and norms associated with birds and animals. For instance, mythical in Gedeo, birds, domestic animals like dog, cat are highly respected and not killed in all circumstances and treated as human beings. In most case, birds are perceived as holistic creatures that foretelling or forewarning of upcoming good or bad omen in the villages and person life. Discussions with songo cultural elders reveals that, bird is true omen indicator (creatures) or foreseeing the upcoming impediments such as death in village, war, disease-outbreak, set backs, sudden accidents, onset of rain season, and ill-luck in person life. On the other hand, some birds also visualizing the upcoming situations like omen of good luck (kayyo) such as safely deliverance of pregnant women in the village, showering of rains, surplus harvesting, fruitfulness, omen of good marriage, the visit of beloved friends, and guests (kesumma), decree onset of farming season and declaration of peace in the villages. For instance, Cuculus solitarius (bekkeko) is popularly known birds in the Gedeo by alerting the onset of farming season (rain seasons). The singing of this bird has given alerts for preparation of farms to plant the enset (Ensete ventricosum), coffee (Coffee arabica L.), beans (Phaseolus vulgaris), maize (maizeZea mays L.) and other farming crops. On the other hand, the birds such as Dendropicos abyssinicus (xixiyyo), Cossypha semirufa (kitiyyo), and Oriolus monacha (shollocho) were associated with providing upcoming bad or good situations. Historical, bird like Tauraco leucotis (warrayye) also associated with traditional marriage practices. The feather of this bird has used to proposed girl for marriage or engagement processes. The men bride’s has stabbing the feather of this bird in dressed hair of proposed girl. Due to the sacredness of bird, stabbed girl with feather, traditional not allowed to merry other men and she has forced to get married the person that being proposed or stabbed with feather. However, this kind of traditional marriage nowadays social banned not to be functioned and declared as bad traditions by community elders. Hence, since time immemorial, birds are not killed and any injuring them is perceived as perjuring the taboos and committed as dreadful sins.

The cultural elders confirmed that,

the most terrible (fearful) sins (cubbo) that our community knew regarding birds is for a man, women or children to break the eggs, damage bird nests and cutting down trees birds nested. It is accepted as sins (cubbo) and causes the misfortune or calamities on the offender families. The most impending situations (elobaxxa farra) for perjuring taboos are infertility after marriages both men and women, early child death, death at birth, health disorder and ill-luck.

From the community elders point of view, there is also some common believes associated with other animals. For example, howling of dog (Canis familiaris) predicts bad news for the family of the vicinity and bad omen for owner of the dog. The crying sound of owl (Otus spp) at night foretelling bad omen to the villagers and predicts the death of person. Similarly, crowing of the cock (Gallus gallus) at a time other than morning is bad omen which perceived as the ruling regime could change in the country. The croaking of owl at night, it indicates bad omen which foretelling the death in village.

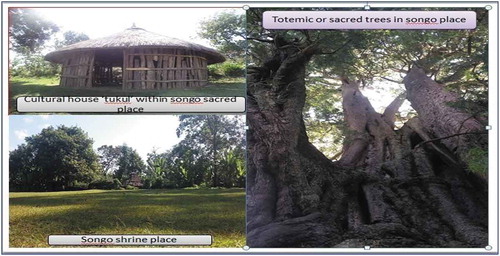

3.6. Songo traditional institutions

The traditional beliefs, social institutions, and practices have been played a crucial role in successful conservation and management of the environmental resources in study area. Particularly, traditional institution like songo has enforcing the customary laws, traditional rules (seera) and playing a crucial role in passing the local declarations. As evidenced from cultural elders, since time immemorial the social coexistence among the Gedeo strongly maintained by obeying to the traditional rules that have enacted by songo indigenous institutions and its cultural elders. This songo institution has guided the moral behavior of entire communities and it compelled the individual person to obliged to rules, norms, and environmental that passed from their ancestors through oral declarations. As stated in previous study (Maru et al., Citation2019) songo is indigenous institution and well-known public ritual meeting place among the Gedeo (Figure ). It has accepted as sacred sites or shrine places to perform cultural ceremonies (such as prayers, swearing, purification, scarification, reconciliation process, and holy places to perform rainmaking rituals which local called qexxalla). The current study reveals that, songo is spiritual dedicated places and serving as indigenous institution to enacting various local rules and norms. In view of this, many ritual ceremonies have been performed in the sanctity of ritualistic places for want of rains, good health of livestock’s, farm productivity (karra miso’a), and for fending off any impending disasters and calamitous situations in the village.

The songo sacred places are maintained as flat, smooth and covered with clean and attractive green grasses local called (Qorichissa) (Figure ). According to the cultural elders, due to the sacredness of songo places stealing the properties from songo environs, infidelity, cutting trees from its surrounding and dishonesty conducts are strictly forbidden and seized by social norms. Any breaking of rules and regulations associated with “ songo” accepted as taboos and believed to cause misfortune and negative things in life of offenders (such as sudden death, infertility, disobedience of children, bareness, curses, and violence in villages). In addition to this, the eyes of songo cultural elders believed as spiritually powerful and fearful. For this reason, the elders are considered as the bridge and nearest mediators that connect entire community with creator (sky God). Hence, no one could deny any facts or making deception in front of elders and under songo sacred places (Figure ). As evidenced by community elders:

“Swearing (kakko) in songo sacred place and under songo sacred trees is accepted amongst traditional religious believers as a declaration of the truth and exoneration from false accusations or crimes”. More surprisingly, any deny of crime/truth in songo and under songo sacred trees,perceived as he/she could receive punitive punishment by losing eye sight (loss of sight) and encountered with various impending situations. Therefore, even non-evidential crimes and disputes are commonly brought to songo places and peacefully resolved by cultural elders without violence since time immemorial.

4. Socio-ecological values of sacred forests and its environmental conservation

4.1. Myths of sacred forest conservation and its origin

The tradition of sacred forest patch preservation and conservation is well-known and entrenched traditions, in the Gedeo community. The concept of “sacred” natural sites in Gedeo involves traditional protected areas (such as sacred forest patches, songo sacred sites, sacred trees, graves, grove [qarra], and spiritual places [bitta hunabba]). From Gedeo community conceptual point, sacred natural sites are Reverend places and locally known as “woyyo” or “uliffesendexxa” bakka. In the community, sacred natural sites are cultural dedicated places for ritual ceremonies and respectful place for player deliverance to creator God (Maggeno). These areas have the religious as well as cultural significance’s for surrounding community and cultural elders. For example, amba sacred forest is holy place which the prayer and thanksgiving rituals were performed and offered to super natural power (magenno) in the organized and culturally systematized approaches with help of spiritual leaders and traditional songo elders.

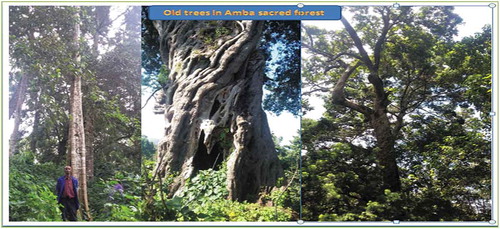

Historical, in many indigenous people a section or pocket of forests, and other natural landscapes are setting aside as sacred (Maffi & Woodley, Citation2012). Similarly, in the study area sacred forest is small in size or fragment of dense natural forests that surrounded by farming habitats particularly by agroforestry land use systems. The discussion held with cultural elders confirmed that, such pocket forest it could be the remnant of once intensive or dense natural forests in the area. Thus, amba sacred forest is a best example of forest patch or pocket area that dedicated for ritual/cultural purposes. It is the old remnant forest vegetation of a once-extensive and diverse landscapes with old majestic trees and havens various wildlife’s (Figure ). This forest patch is regarded as ritualistic and being protected by informal prohibition systems (taboos) and ancestral oral declarations. Mythical this forest was shielded or safeguarded the forebears of current generation from dreadful conflicts and enemies inventions. Their forefathers had took refugees and hide their properties, children, women’s, and livestock’s within this forest until the enemies had evicted from area.

A local elderly man said that:

Amba is holy or spiritual dedicated forest in the village. Historical, this ritual forest was shielded or havens our ancestor/forefathers from enemies and our forefathers took refugees and rescued from their kidnappers or enemies during the violence and blood shedding conflicts”. Thus, since time immemorial, amba forest has been preserved and protected as sacred place and ritualistic area which the elders deliver the prayers to sky God via reverences of amba forest.

The remaining forest patch and its immediate surroundings, especially periphery, has protected on the basis of the cultural taboos that pronounced by forebears not to injure the forest and its biodiversity. According to the traditional elders, taboo is unwritten rules that have been accepted within community as informal laws and individual member of families has obliged to respect and not to perjure these rules (seera). The community has obeyed to unwritten bandaging laws of their ancestors not to damage the forest patch. Hence, the sacred forest or old trees within forest has protected from generations to generations. One of the cultural (hayyichcha) elder men state that:

This respectful forest is not protected by formal laws or formal policemen; it has been protected by strong customary laws and ancestral sanction systems (taboos). Our ancestors or forebears were pronounced curses nakedly not to damage or injure this forest.

Thus, individual community member has obligation to compel the taboos or not to perjure the pronounced words of forefathers. In addition to this, the tree ownership right also has its own specific impacts on the tree diversity and conservation’s. In sacred forest, tree owned by entire communities which belongs to public and strongly regulated by ancestral sanction systems and human impact is minimal in forest resources. Contrary, in non-sacred farming habitats, land owner holds the tree ownership right and individual have right to plant, cut, prunes, and to use it for various purposes and other economic purposes.

4.2. The prohibition systems (taboos) and social banishment as conservation tools

As stated by songo cultural elders, due to its reverence, the local villagers are delivering mass prayer to God in the name of “amba holy forest”. They had common beliefs that God could response players positively only if the sacred forested protected and conserved in sustainable manure without perjure of ancestral taboos. Thus, the mass-prayers have been delivering in surrounding of the amba forest in case of unexpected impending calamities in the villages (such as drought, death, infertility, bareness, ill-luck, diseases out-break, and early death). The intensity of player responses from creator God (magenno) is basically depends on the protection and obeying of customary laws. In case, any mismanagement and perjure could bring negative impediments to the villages and offenders. For this reasons, tree of this forest are sacred and hence no axe may be laid to any tree, no branch broken, no firewood gathered, no grass burnt; and wild animals which have taken refuge there may not be molested, and hanging of beehives, grazing, the violence and shedding bloods, defecation and doing any infidelity deeds within this holy forest is accepted as disrespect-full practices and committed as sins. Even though the entire Gedeo community is vested responsibility to preserve this forest at a broader context, the spiritual leaders, cultural baalle leaders (abg-gada), village elders and songo chiefs (hayichchuwa) are traditional appointed and responsible bodies in enforcing the traditional rules and customary laws associated with conservation and management of amba sacred forest. Thus, these customary laws and informal rules (seera) indirectly playing critical role in conservation of forest biodiversity and other bio-physical environments in studied area.

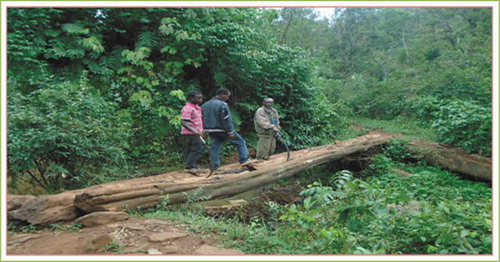

Figure 4. The deadwood chopped from sacred forest for setting fire in songo ritualistic hearth in songo houses for elders (Photo taken by Y.Maru.).

Therefore, any disobedience could bring harm to the offenders, if the forest is disturbed or mismanaged by community members for personal benefits and house uses. Thus, to protect family from such calamities, individuals abstain from prohibited activities and not perjure the taboos. But, apart from its cultural devotions, some selected activities were allowed with consent of spiritual leaders and songo cultural Elders, if it is needed for community benefits as whole (such as collecting medicinal plants, selective cutting of old trees to laid down over river for public uses (Figure ) and chopping of uprooted or dead-woods for ritual ceremonies or to setting fire on the hearth of songo cultural houses while the local elders have public meetings and ritual ceremonies in cultural house of songo (Figures and ). In addition to this, spiritual enthusiastic grasses (herbs) also harvested from sacred forest in case of needed for making “huluqqa” in annual thanksgiving ceremonies and to cover the roof of songo cultural houses. In sum, the conservation of natural resources such as sacred forests and trees in Gedeo is partly done by controlling the number of people from injuring. The delineation of some part of the forest as sacred is encourages the conservation and protection of biodiversity including all the wildlife.

4.3. Tree conservation statuses in amba sacred forests

Apart from the bio-cultural assessments the tree biodiversity inventory was carried out to understand the conservation statuses of sacred forest habitat. From state of the inventory results, sacred forest habitat had well-established conservation statuses and inhabits diversified tree species than adjacent non-sacred farming habitat (Figure ).

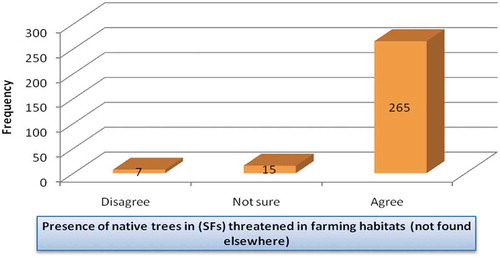

In Ethiopia, studies documenting the role of sacred forest in conserving tree species are emerging in response to adverse climate change and environmental degradation. This study reveal that sacred ecologies, particularly sacred forests are havens and conserving the threatened tree species due to the traditional beliefs and prohibitions (taboos). In terms of the conservation statuses, Podocarpus falcatus (bribirissa), Syzygium guineense (Badessa), Aningeriaadolfi-friedeicii (Gudubo), Oda-badee (scientific name is unknown), Cordia africana (wodessa), Croton macrostachyus (mokenissa), Albizia gummifera (Goribe) were dominate and abundantly counted indigenous trees in amba sacred forest while critical threatened in adjacent non-sacred farming habitat (Table ). The case of some trees that were local reported as “fast disappearing” or “already loss” at other places being conserved at sacred forest habitat is significant. As evidenced from our tree inventories, particularly Aningeriaadolfi-friedeicii (Gudubo), Podocarpus falcatus (Bribirissa), Cordia africana (wodessa), and Syzygium guineense (Badessa) were indigenous tree species that rarely counted in the adjacent farming habitat but abundantly enumerated in sacred forest patch (Table ). This also confirmed by opinions of household head that may of them were reported sacred forest as havens for threatened tree species that not found elsewhere or for those tree species threatened in farming landscapes (Figure ). This is similarly acknowledged by (Khan et al., Citation2008) the several plants and animals have been conserved in the sacred groves and prohibition systems.

Table 1. Dominate woody/indigenous tree species in amba sacred forest and conservation statuses in adjacent agroforestry

In addition to this, all tree species inventoried in the sacred forest were indigenous or native to the area. It is generally the view of the community, represented through interviews and surveys, that sacred forest serve as havens for such native trees (Table ). The result generally shows that sacred forest and its socio-cultural beliefs play positive roles in preserving native plants and ethno-botanical knowledge of local people. In sum, the traditional beliefs and taboos helped in enforcing rules and regulations for forest preservation because people refrained from using resources carelessly, especially as it is related to sacred places.

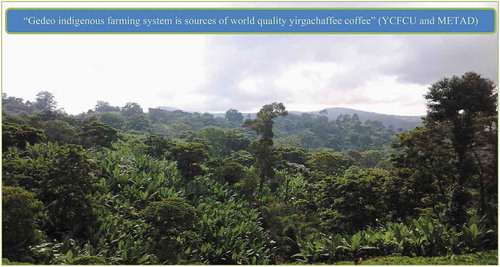

In contrast, non-sacred farming habitat is highly dominate by agroforestry land use systems with perennial and annual crops (94.5%) as previously published (Bogale, Citation2007; Mebrate, 2007). The current study also confirmed that, non-sacred farming habitat was retained mainly perennial crops such as Ensete (Ensete ventricosum), coffee (Coffea arabica), and woody species (Table ). The farmers were intentionally integrating economically significant cash crops and ecologically viable multipurpose woody species on farms. The discussion with indigenous farmers reveals that, the main reasons for integrating multipurpose tree species with perennial crop in non-sacred habitat were mainly for economic and ecological aspects such as firewood, fodder, timber production, soil fertility improvement, and shading crops. Based on the inventory results, the most dominate native tree species in non-sacred farming habitat were Millettia ferrunginea (Dhadhatto), gorbe (Albizia gummifera), wodessa (Cordia africana), ebicha (Veroniaamygdalina Del.), ode’e (Ficusvasta), Qilta (Ficussur), and Erythrina abyssinica (wollena) (Table ).

Table 2. Some dominate plant species in adjacent non-sacred farming habitat and its origin and uses

5. Factors eroding indigenous belief systems and endangerment’s of sacred natural sites

Indigenous beliefs, rituals, cultural mores and indigenous knowledge have been playing crucial roles for the successful conservation of the (tree) biodiversity and environmental resource. As stated in previous topics, in revered areas, local people refrain from cutting down trees, killing animals, practicing farming activities and injuring such ritual sites. But, currently such indigenous mechanisms of natural resource conservation and protection are under great pressure and erosion’s. The interviews have conducted with cultural elders reveal that, population pressure, change in social norms, lack of documentation and the introduction of modern faith (religious monotheism) were the main factors have eroding the indigenous ways of NRs protection in the study area. In addition to this, community elders stated that, the introduction of formal education and adaptation of modern knowledge among the current generation has been watered down the value and respect given to indigenous knowledge, taboos and cultural beliefs. This also similarly acknowledged by Abiyot (Citation2012) in his findings the formal education is eroding and gearing dynamics in the indigenous knowledge systems and agroforestry knowledge.

Figure 7. Household heads’ opinions of sacred forests’ role as showcase for threatened native trees not found elsewhere, Gedeo Zone, Ethiopia (n = 287).

5.1. The religious monotheism (Introduction of modern faith)

Eneji et al. (Citation2012) argued that, traditional religious belief systems are being eroded via acculturation and enculturation of most African communities, especially the introduction of Christianity and formal education. Similarly, traditional beliefs, environmental ethics and indigenous knowledge systems were used as a conservation tool is under great pressures and abrogation. I must stress here that, with the arrival of modern faith (protestant) and formal education, some of these traditional practices and believes are steadily losing their value in the current generation, and as a result has led to the termination and abrogation of local practices, rituals and ancestral traditions. This was also acknowledged in findings of Eneji et al. (Citation2009) the introduction of western religion and formal education somehow eroded the rich cultural values and religious diversities of Africans and also changed their belief and worship systems. According to the respondents, the introduction of missionary particularly the protestant faith has been watered down the value and respect given to indigenous beliefs, rituals, taboos, and environmental ethics. More evidently, the religion leaders or pastors have banned or pass sanctions, if the religion followers could violate the ban or they went to the ritual ceremonies or sacred songo places.

The cultural elders confirmed this:

The expansion of Christianity (barinixxa addee), particularly protestant faith in the area has been watered out Gedeo traditional religion and taboo systems. Modern Christianity faith or protestant religion has decreed cultural beliefs and rituals as evil and satanic deeds. That has no link with God the Father Almighty (maggenno) and it has been preaching community members or religion followers not go to rituals, sacred areas and songo places. But, since immemorial time, our ancestral was used traditional religion and indigenous institutions as their spiritual well-being and conservation tools for socio-economic-sustenance-and-coexistences.

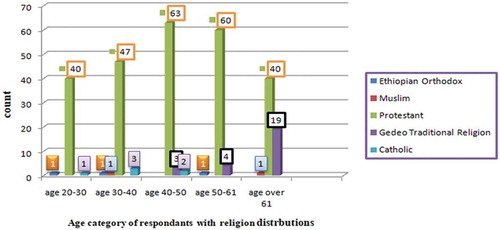

The supremacy of modern faith, particularly protestant religion in the study area, has put adverse pressure on the traditional belief systems and ritual practices that have been used as conservation strategies for long periods. Many of respondents confirmed that, songo cultural deeds, the preservation of sacred sites, performing ritual ceremonies and obey to environmental ethics have been abrogated and eroded by introduction of modern thinking among the youth, change in social norms and supremacy of modern faith dominance’s. Particularly, the expansion and dominance of protestant faith in study area has played great roles in eroding the traditional beliefs; and thus only a few old people (songo cultural elders) were adhere to devote and performed often their ancestral traditional religion and beliefs (Figure ). In the survey, 250 respondents (87.1%) of sampled households (n = 287) were protestant faith followers whereas 9% (26) adhere to devote traditional religion and beliefs (Figure ).

In addition to this, the age also had significant effects on practicing and devotion to religious beliefs and indigenous practices. The respondents had age category (above 61) in the survey adhere and devote to beliefs in traditional religion and they were actively perform rituals and attend in songo indigenous social institutions when compare to those in age group below 40 (Figure ). Hence, religion followers, and pastors have decreed the abrogation of traditional institutions, ancestral beliefs, and ritual practices. Therefore, this tremendous religious rivalry is restricting young people and protestant followers from attending in songo traditional institutions, performing rainmaking rituals (qexxa’lla), veneration of sacred sites and conservation of ritualistic tree species. However, in case of sacred forest and sacred sites reverence, many respondents had agreed in conservation and protections.

One of the protestant faith follower confirmed that:

I am protestant religion follower and my religion not allow me to go ritual area or to take part in traditional religion rituals. But I adhering the traditional rules (seera) and respecting sacred sites like sacred forest and songo ritual areas are mandatory. As family, we have been feared to cut trees from sacred forests or graves (hiressa). we all respects our culture, the problem is we couldn’t often attend the annual ritual and the devotion towards traditional religion is very seldom due to the Protestant doctrine.

5.2. The disobedience for traditional rules and norms (seera)

Many songo elders agreed that, the current generation less and less respecting for ancestral traditional rules. There has been breaking of rules (seera), environmental ethics, and norms among the young generation. Off course, the Gedeo traditional rules are basically grounded on respecting each other and adherence’s for norms. The co-existence of Gedeo people is established on the long stand rules, norms, and principles. Every family member should know and implement these values. The traditional rules are encouraging the elders to teach their children. Elders and parents have the duty to familiarize these rules and norms to their youngsters and coming generation. According to the cultural elders, the traditional rules and norms such as respecting songo elders, keeping environmental ethics, obedience for traditional sanctions (seera) and families were under great pressure and erosion among the generation. These disrespecting norms to indigenous beliefs, taboos and environmental ethics have been encouraging the mismanagement of environmental resources. In addition to this, lack of documentation for indigenous practices, and ignoring them instead of incorporating is one of challenges have raised by respondents during interviews.

5.3. Population pressure

Population pressure in terms of agricultural expansion is main and adversely affecting, and eroding factors for less respect of sacred sites and taboos. One local elder revealed that:

Population pressure and demanding additional lands for farming activities are adversely affecting the indigenous beliefs and respect for taboos. Due to the farming land shortage, the taboo breakers expanding farming activities to sacred forests, graves and sacred sites. Nowadays, local people/law breakers cutting trees from graves, sacred sites and constructing house from trees were harvested from graves (hiressa).

Field visit with local elders also confirmed this, the size of sacred forests and songo places were severely degraded and loss its size from original size due to the encroachments. The households surrounding the environs of songo sacred sites, pushing its boundary for agricultural activities and competing for farming land such as planting enset (Ensete ventricosum), seasonal crops, coffees (Coffea arabica), and other perennial crops (Figure ). The field visit with ritual leaders and observation confirmed that, the bollocho, kallacha, and amba sacred forest patches were adversely encroached due to the farming land expansion and mismanagement.

Songo elders evident that, the main reason for encroachments of sacred sites was less devotion among the young population for cultural taboos that used as conservation tools. One of local elder revealed that,

In our community mores, ancestral graves are respectful and frightened place as shrine. The community members are abstained from cutting trees and encroachment. It is frightening sites to allow their animals to graze within environs of grave sites. But, today due to change in social norms and erosion of cultural taboos local people nowadays are cutting trees and grazing their animals in frightened places, and converting them into agricultural lands.

In the Figure (9) illustrated that completely damaged and abandoned sacred site in the village due to the farming expansions and unplanned infrastructural (road) development.

6. Conclusion and recommendations

From the very on-set, the paper aims at looking at the roles of traditional beliefs, environmental ethics, and socio-cultural practices in conservation of natural resources. Indeed, natural ecosystems loss currently a major concern to mankind, and all life on earth. But, over the millennia, indigenous peoples have developed environmental resilient traditional practices. Apart from economic aspects, they have a close and intimate cultural connection with their lands, forests, trees, and surrounding biodiversity. Indigenous people have well established distinct systems of knowledge, innovation and local practices relating to the uses and management of environmental resources. On the other hand, traditional belief systems and taboos that associated with biodiversity protections (such as trees, shrine places, wildlife, and forest) are still maintained and used as conservation tool for safeguarding and protecting the remnant natural resources. For instance, indigenous people are setting aside sacred ecologies (such as sacred grove, sacred forests, trees, animals, and plants) for spiritual as well as cultural purposes. These traditional protected areas as acknowledged by many scholars, they well reserved and havens the endangered wildlife and plants than formal protected areas.

The data and discussion above are a testimony to the indigenous ways of natural resource conservation and sacred forests as showcases for the conservation of locally endangered native trees, such as Aningeriaadolfi-friedeicii (Gudubo), Podocarpus falcatus (Bribirissa), Cordia africana (wodessa), and Syzygium guineense (Badessa), and cultural diversity associated with the species. In this regards, various forms of indigenous knowledge practices in Gedeo community that assist in the conservation of local ecologies and agro-biodiversity. In view of this, the mythical and cultural connection between nature and people is manifested by setting aside sacred forest, sacred trees, and venerated places are informal mounting the conservation of surrounding ecosystems in sustainable manners. For example, the sacred forest patch has been protecting for cultural purposes and played a great in conservation of endangered trees and various wildlife in study area. The tree species inventories showed that the sacred ecologies (for example, amba sacred forest has undisturbed, dense vegetation, consisting of a large old trees and havens threatened wildlife than farming landscape). This traditional protected forest is showcases or undisturbed place for endangered indigenous trees in farming habitats. Due to the prohibition system of taboos and ancestral sanctions (seera), local people abstain themselves from mismanagement of sacred forest and its biodiversity. That why this religious place is havens or refugees threatened trees in farming landscapes, tree species such as Podocarpusfalcatus (bribirissa), Syzygiumguineense (Badessa),Aningeriaadolfi-friedeicii (Gudubo), Oda-badee, Cordia africana (wodessa), Prunus africanum, and Albizia gummifera (Goribe) were dominate tree species in sacred forest while critically threatened species in non-sacred adjacent farming habitat.

On the other hands, over the years, traditional belief systems and indigenous knowledge that conserve the natural resources now under adverse pressure due to the changes in the social norms, modern thinking infiltration, population pressure, and religious monotheism. The young population has forced to abrogate ancestral rules and norms have been practicing by their forebears.

This research paper recommended that for providing necessary protection to indigenous practices, beliefs, and traditional rules (seera) the surrounding people, governmental officials, modern faith followers and young people need to be educated for conservation awareness. Unless we safeguard taboos, local practices, ancestral rules (seera), and traditional beliefs in general, there could be negative consequences and destructive pressure on the remaining patches of sacred ecologies and agro-biodiversity. In view of this, researchers, conservation experts, policymakers, government, and modern communities should pick those indigenous practices and local knowledge that encourage the conservation and management of natural resources and livelihoods of community.

7. In sum, the paper is forwarding the following recommendations

The local government structures particularly kebele (PA) or local officials should work closely with cultural elders and religion leaders in protecting the ritual sites, sacred forests and sacred trees in the villages. This will increase conservation and awareness of local community about sacred sites.

All concerned stakeholders particularly local government should work together in terms of enforcing local rules to preserve the remaining forest patch, indigenous knowledge practices and belief systems.

Further, indigenous ecological knowledge systems and beliefs should properly document to maintain its sustainability and to pass the its old dating practices in perpetuate ways from one generation to another.

The government and other conservation agencies should encourage local communities still having and practicing traditional mechanisms of natural resource conservation and management, this can be done through positive motivation and incentives like rewards and also promoting experience sharing tour to the community.

Final, the documentation and inventories of sacred forests, songo sacred sites and natural ritual sites are to be needed for further protection and preservation.

Many unplanned infrastructural development like road project is devastating the sacred sites and cultural heritages. Therefore, the concerned governmental body should give attentions and the rural development project should guided with planned manners.

The mass tourism and group educational tours also recorded as threats in sacred natural sites. The students, researchers, and NGO experts have been put adverse pressure on ritual sites by littering, harvesting medicinal plants for research, injuring sacred trees, and others were the main factors that adversely affecting the cultural sites. Therefore, the concerned government body should stress on it by improving management plans.

Acknowledgements

The people and organizations that were helpful in completing this research article need to be acknowledged. I wish to first express my sincere gratitude to my mentor and academic supervisors, Aster Gebrekristos (PhD) and Getahun Haile (PhD) for their scientific commitments, guidance and support in the preparation of this work. I am also thankful to my friends Fikadu Abebe (Economist), Fikadu Dayasso (MA), Samuel Boku (lawyer), Danial Tadesse (Economist), Melkamu Shiferawu (Msc), Fantahun Ayele (lawyer) and Tedila Getahun (PhD candidate) for their support in diverse ways and encouragements during my research work. My hearty thanks also goes to Gedeo zone administration main office. This work would not have been possible without the financial support of the Yirgachaffe Coffee Farmer’s Cooperatives Union, Gedeo zone (YCFCU) special Takele Mamo, General manager of YCFCU for his academic outlooks, METAD organic coffee washing and exporting industry PLC and Dilla University for diverse supports. In addition to this, I would like to express my deepest appreciation and thanks to Gedeo indigenous farmers for sharing their incredible knowledge in environmental conservation, farming practices, bio-cultural diversity and they had educated me in diverse ways of sociocultural aspects.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Yoseph Maru

Yoseph Maru, a former experts and chief head of culture, tourism, and government communication affairs office in Gedeo zone, Ethiopia. He has a BA degree in Tourism Management, MA in Development Management and currently he is PhD student in Dilla University, Ethiopia. Overall, he has seven years’ experience of working in culture, tourism, hospitality industry, communication media and development aspects. He has publication contribution in peer-reviewed and reputable journal mainly related to the role of IK in environmental protection, tree conservation, and acidic soil amendments. He has also presented his research findings in various national research conferences organized by Ethiopian Universities. Further he has other prepared manuscripts ready to send to reputable peer-reviewed journals. The research reported in this paper is a part of PhD dissertation project that mainly focused on promoting indigenous knowledge practices, tree biodiversity conservation, sacred forests, carbon stocks and the research work also could enhance the sustainable natural resource conservation.

References

- Abiyot, L. (2012) The Dynamics of Indigenous Knowledge Pertaining to Agroforestry Systems of Gedeo: Implication for Sustainability [PhD Dissertation]. University of South Africa.

- Adu-Gyamfi, M. (2011). Indigenous beliefs and practices in ecosystem conservation: Response of the church. Scriptura, 10(7), 145–26.

- Appiah-Opoku, S. (2007). Indigenous beliefs and environmental stewardship: A rural Ghana experience. Journal of Cultural Geography, 22(2), 79–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/08873630709478212

- Attuquayefio, D. K., & Gyampoh, S. (2010). The Boabeng-Fiema monkey sanctuary, Ghana: A case of blending traditional and introduced wildlife conservation systems. West African Journal of Applied Ecology, 17, 1–10.

- Ayal, D. Y., Desta, S., Gebru, G., Kinyangi, J., Recha, J., & Radeny, M. (2015). Opportunities and challenges of indigenous biotic weather forecasting among the Borena herders of southern Ethiopia. SpringerPlus, 4(1), 617. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40064-015-1416-6

- Barre, R. Y., Grant, M., & Draper, D. (2009). The role of taboos in conservation of sacred groves in Ghana’s Tallensi-Nabdam district. Social and Cultural Geography, 10(1), 25–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649360802553194

- Bekele, T., Haase, G., & Soromessa, T. (1999). Forest genetic resources of Ethiopia: Statuses and proposed actions. ln Edwards, S., Demmissie, A., Bekele, T., & Haase, G. (Eds), The national forest resource conservations strategy development workshop (pp. 39–49). Proceedings of national workshop from 21–22, June 1999 held in Addis Ababa. Institute of biodiversity conservation and research (IBCR), GTZ, Addis Ababa

- Bhagwat, S. A., Dudley, N., & Harrop, S. R. (2011). Religious following in biodiversity hotspots: Challenges and opportunities for conservation and development. Conservation Letters, 4 (3), 234–240. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1755-263X.2011.00169.x.

- Bhagwat, S. A., & Rutte, C. (2006). Sacred groves. Potential for biodiversity management. Frontiers in Ecology and Environment, 4, 519–524. https://doi.org/10.1890/1540-9295(2006)4[519:SGPFBM]2.0.CO;2

- Bhagwot, S. A. (2004). Ecosystem services and sacred natural sites. Reconciling Material and Non-material ValuesIn Nature Conservation, 18, 417–427.

- BIE. (2014). Ethiopian Institute of Biodiversity » Conservation and Sustainable Use of Medicinal Plants Project (CSMPP).

- Bogale, T. (2007). Agroforestry Practice in Gedeo Zone, Ethiopia: A geographical Analysis[Ph.D dissertation], 188.

- Bongers, F., Wassie, A., & Sterck, F. J. (2006). Ecological restoration and church forests in northern Ethiopia. Journal of Drylands, 1, 35–44.

- Cardelu´s, C. L., Lowman, M. D., & Wassie, E. A. (2012). Uniting Church and Science for Conservation. Science, 33(5), 916–917.

- Cook, J., Nuccitelli, D, Green, S. A., Richardson, M., Winkler, B., Painting, R., Way, R., Jacobs, P., & Skuce, A. (2013). Quantifying the consensus on anthropogenic global warming in the scientific literature http://iopscience.iop.org/1748-9326/8/2/024024

- Creswell, J. W. (2013). Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (4th ed.). SAGE Publications, Inc.

- Dickson, A., Asante, S. K., Nana, A., & Pokuaa, A. (2018). The conservation Ethos in the Asante cultural and artistic elements for the management of Ghana’s biodiversity. International Journal of Social Science Reviews, 4(2), 1–22.

- Doffana, Z. (2014). ‘Dagucho [Podocarpus falcatus] Is Abbo!’ Wonsho Sacred Sites, Sidama, Ethiopia: Origins, maintenance motives, consequences and conservation threats [PhD Dissertation]. University of Kent.

- Doffana, Z. D. (2017). Sacred natural sites, herbal medicine, medicinal plants and their conservation in Sidama, Ethiopia. Cogent Food & Agriculture, 3(1), 1365399. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311932.2017.1365399

- Dudley, N., Higgins-Zogib, L., & Mansourian, S. (2009). The links between protected areas, faiths, and sacred natural sites. Conservation Biology, 23(3), 568–577. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2009.01201.x

- EFAP (Ethiopian Forestry Action Program). (1993). Ethiopian forestry action program: The challenges for development (Vol. 2). Ministry of Natural Resources Development and Environmental Protection.

- Endalkachew, B. (2015). The place of customary and religious laws and practices in Ethiopia: A critical review of the four modern constitutions. Social Sciences, 4(4), 90–93. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ss.20150404.14

- Eneji, C. V. O., Gubo, Q., Jian, X., Oden, S. N., & Okpiliya, F. I. (2009). A review of the dynamics of forest resources valuation and community livelihood: Issues, arguments and concerns. Journal of Agriculture, Biotechnology and Ecology, China, 2(2), 210–231.

- Eneji, C. V. O., Ntamu, G. U., Unwanade, C. C., Godwin, A. B., Bassey, J. E., Willaims, J. J., & Ignatius, J. (2012). Traditional African religion in natural resources conservation and management: Cross River State, Nigeria. Canadian Center of Science and Education, 45.

- FAO. (2008). State of the World’s Forests. Retrived June 14, 2018, from. http://www.fao.org/docrep/009/a0773e/a0773e00.htm

- Fonjong, L. N. (2008). Gender roles and practices in natural resource management in the north west province of cameroon. Local Environment, 13(5), 461–475. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549830701809809

- Frascaroli, F. (2013). Catholicism and conservation: The potential of sacred natural sites for biodiversity management in Central Italy. Human Ecology, 41(4), 587–601. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10745-013-9598-4

- Gedeo zone finance and development (GZFD). (2009). Annual development and agriculture plan: annual report, 2009. Dilla: Gedeo zone-Ethiopia.

- Gemeda, O. (2018). Why some natural areas are sacred? Lesson from Guji Oromo in southern Ethiopia. Global Journal of Arts and Humanities, 1, 6.

- Heide, F. (2012). Feasibility study for a Lake Tana Biosphere Reserve, Ethiopia. Bundesamt für Naturschutz (BfN)/Federal Agency for Nature Conservation. http://www.bfn.de/fileadmin/MDB/documents/service/Skript_317.pdf

- Henshey, L. (2011). Religious & spiritual mysteries examiner.

- Ikyaagba, T. E., Tee, T. N., Dagba, B. I., Anncha, U. P., Ngibo, K. D., & Tume, C. (2015). Tree composition and distribution in Federal University of Agriculturema Kurdi, Nigeria. Journal of Research in Forestry Wildlife and Environment, 7(2), 147–157.

- IPCC Climate change. (2007). Impacts, adaptation and vulnerability. Report of the working group II. Cambridge University Press, 967.

- IUCN (World Conservation Union) (2008) Redlist of threatened species. Retrived March 20, 2017, from http://www.iucnredlist.org

- Khan, M., Khumbong, M. A. D., & Tripathi, R. S. (2008). The sacred groves and their significance in conserving biodiversity: An overview. International Journal of Ecology and Environmental Sciences, 34, 2077–2291.

- Kideghesho, J. R. (2009). The potentials of traditional African cultural practices in mitigating overexploitation of wildlife species and habitat loss: Experience of Tanzania. International Journal of Biodiversity Science & Management, 5(2), 83–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/17451590903065579

- Lemessa, M. (2014). Indigenous forest management among the Oromo of Horro Guduru, western Ethiopia. Ethiopian Journal of Social Sciences and Language Studies, 1(2), 5–22.

- Maffi, L. (2005). Linguistic, cultural, and biological diversity. Annual Review of Anthropology, 34(1), 599–618. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.anthro.34.081804.120437

- Maffi, L., & Woodley, E. (2012). Biocultural diversity conservation: A global sourcebook. Routledge.

- Magurran, A. E. (2004). Measuring biological diversity black-well science. Oxford.

- Mallarach, J. M., Papayannis, T., (Eds.). (2006). Protected areas and spirituality. IUCN and Publicacions de l’Abadia de Montserrat.

- Maru, Y., Aster, G., & Getahun, H. (2019). Farmers’ indigenous knowledge of tree conservation and acidic soil amendments: The role of “baabbo” and “Mona” systems: Lessons from Gedeo community, Southern Ethiopia. Cogent Food and Agriculture, 5(1), 1645259. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311932.2019.1645259

- Mascia, M. B., Pailler, S., Krithivasan, R., Roshchanka, V., Burns, D., Mlotha, M. J., Murray, D. R., & Peng, N. (2014). Protected area downgrading, downsizing, and degazettement (PADDD) in Africa, Asia, and Latin America and the Caribbean, 1900–2010. Biological Conservation, 169, 355–361. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2013.11.021