?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

The ecological settings in the Himalayan hills provide a unique opportunity to the farmers in Nepal to sell their large cardamom in the global market. However, little efforts are made about the adoption of profitable large cardamom post-harvest upgrading practices in the country. This paper examines and discusses about the adoption of important post-harvest practices of large cardamom in the Eastern Himalayan road corridor of Nepal. Semi-structured interviews with 300 large cardamom-producing farmers as well as focus group discussions were conducted in Taplejung district in 2019. A SUR logit was used to examine the factors influencing the adoption of five major post-harvest practices, such as, improved method of drying, curing, cleaning, tail cutting and grading based on size and color. The findings revealed that about one-third of the respondents had adopted improved method of drying whereas about three-fifth of the respondents (62%) adopted curing. Nearly three-fourth (73.3%) of them had followed the practice of cleaning cardamom. On the other hand only less than 5% of respondents reported that they had been adopting the practice of tail (calyx) cutting. The findings also revealed that the adoption of improved method of large cardamom drying was mostly driven by access to credit. Results from an adoption models identified experience, household income from large cardamom, commercial scale of production, risk averse, access to credit, and access to technical services as of positive contributors (p < 0.05) to the adoption of major post-harvest practices of large cardamom.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

The ecological settings in the Himalayan hills provide a unique opportunity to the farmers in Nepal to sell their large cardamom in the global market. A SUR logit model was used to examine the factors influencing the adoption of five major post-harvest practices of large cardamom, namely curing, drying, cleaning, tail cutting and grading. The findings revealed that the adoption of improved method of large cardamom drying was mostly driven by access to credit. Results from an adoption model identified experience, household income, commercial scale of production, risk averse, access to credit, and access to technical services were found as of positive contributors to the adoption of major post-harvest practices. These findings thus clearly hint that promotion of major post-harvest practices would be needed at farm level to increase the income of farmers, and also to become competitive for large cardamom global market.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

1. Introduction

Large cardamom (Amomum subulatum Roxb.) is one of the world’s most ancient spices, popularly known as Alainchi in Nepali and renounced as Black Gold, Queen of Spices. It belongs to the Zingiberaceae family and is a perennial soft-stemmed low-volume, high-value crop (Avasthe et al., Citation2011). Originating in Sikkim (India), the crop is grown only in the eastern Himalayan countries viz., Nepal, northeast India, and Bhutan (Sharma et al., Citation2009) at altitudes ranging from 1000 to 2000 meter above sea level. Large cardamom is the high-value cash crop and main source of cash income for farmers in eastern Himalayan region. It is one of the highest export revenue earning high-value products of Nepal. The International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development reported that in Nepal over 21,960 households are engaged in its farming.

Total area of large cardamom in Nepal was 12511 ha with 6528 MT production and 520 kg/ha productivity in fiscal year 2016/17. From 1994/95 to 2016/17, an average area within 23 years of large cardamom in Nepal has been increased by 1.6% whereas production was increased by 4.5%. On an average area of large cardamom in Nepal has been increased by 183.5 ha per year whereas production increased by 79.8 MT per year. The productivity of cardamom is also highest in Taplejung with 0.7 MT per hectare in comparison with national productivity which is 0.52 MT per hectare (District Agriculture Development Office [DADO], Citation2017; Ministry of Agriculture Development [MoAD], Citation2017). The contribution of large cardamom on farmer’s livelihoods is significant in terms of both employment and as a source of household cash income (Chapagain, Citation2011).

Economic yield of large cardamom starts from third year onward after its plantation and its optimal yield period is 8–10 years. The total life span of large cardamom plants is about 20–25 years. There are sixteen varieties of large cardamom in the world and they are known for high quality in the market as they have unique taste and flavor (Adhikari & Sigdel, Citation2015). According to the regulations of the Department of Food Technology and Quality Control (DFTQC), cardamom capsules should not include more than 5% extraneous matter, including calyx pieces and stalk bits. Its seed should contain a minimum of 1% (volume/weight) of volatile oil (Government of Nepal / International Trade Centre [GoN/ITC], Citation2017).

In recent years, the crop has undergone several changes in the demand as well as supply front. The supply demand discussion is from a regional perspective, because the crop from all three countries of Nepal, India and Bhutan is largely marketed in Siliguri in India, from where it is sold in retail market all over the country, or sold to processors or exported.

In general, curing, drying and cleaning of large cardamom are carrying out at the farm level by farmers, while tail cutting, size and color grading are done at the collectors and exporters level in Nepal. Curing is the most crucial step in processing, as the quality of the capsule depends largely on the conditions and methods of curing. The optimal curing temperature is 45°C to 55°C and is generally done in traditional bhatti.Footnote1 Dried capsules are generally packed in polyethylene-lined jute bags for storage with 11% moisture content (Bhutia et al., Citation2018). Fresh capsules have a moisture content of 70% to 80%. In curing, the moisture content is reduced to a level that is safe for storage, about 10 to 12%. Curing substantially reduces the weight of the capsules. The final weight depends on various parameters, including the initial size, the final moisture content, the cure method, and the cure temperature. Curing is usually done in traditional bhatti. Depending on capsule size and curing methods, the weight ratio of fresh to cured capsule is 4∶1 to 5∶1 (Madhusoodanan & Rao, Citation2001). The tail of the capsule (calyx) is removed manually with scissors, a laborious and time-consuming slow process. Capsules are classified by size and color, but no reports of use of mechanical graders have been found in the study area. Harvest and post-harvest processing methods (curing, chalice cutting, packaging and storage), quality problems and their impacts on the value chain and business patterns, it also suggests future research and development approaches that could make cultivation more sustainable (Bhutia et al., Citation2018).

Large cardamom is used in foods, beverages, perfumes, and medicines. Production is currently declining, and the improved post-harvest process would be one way to help ensure the sustainability of this position crop. The drying by the traditional system has reduced the quality of cardamom capsules (colour, flavour and oil content, etc.) and as well as cost as compared to improved drying with good quality product (Ranjan et al., Citation2018). Bhutia et al. (Citation2018) also reported that the well-processed quality capsules have great demand in the market and help the growers by protecting and promoting their livelihood. Furthermore, Singh and Pothula (Citation2013) reviewed the crop’s post-harvest processing (with emphasis on curing, calyx cutting, packaging, and storage), quality issues, and trade patterns, and identifies research topics that could contribute to increase its quality and value and thereby protect and promote the livelihoods of several thousands of people in the value chain.

Use of improved bhatti for curing large cardamom capsules has been recently adopted in eastern Himalayan road corridor districts in Nepal since few years. The improved method of curing is an indirect heating system that uses heated air and a flue gas pipe arrangement to dry capsules. The capacity of improved bhatti varies from 200 kg to 400 kg of fresh capsules in 17 to 24 hours drying time having excellent product quality with maroon color and 2% to 2.4% volatile oil content (Singh & Pothula, Citation2013).

Global production of large cardamom, a high value, low-volume crops, has fallen in recent years due to several factors, including diseases and global price fluctuation. Adoption of proper post-harvest processing techniques can help to compensate decreased production by reducing post-harvest losses and adding value. Improved kiln (bhattis) yields better quality than traditional kiln (bhattis), but these devices have not been well accepted by farmers (Singh & Pothula, Citation2013). Large cardamom producers need a low-cost curing system that can produce good-quality capsules. Sever other labor-intensive postharvest processing operation such as separating capsules from spikes, cleaning, tail cutting and grading have not well practiced at farm level in the study areas (Singh & Pothula, Citation2013). They grade their cardamom by three categories as Jumbo Jet (JJ), Standard/Super Delux (SD) and usual type (Chalan chalti/Ilami) making price variation to the producers as well as for quality selling (Federation of Large Cardamom Enterprenuers of Nepal [FLCEN], Citation2016).

In this context, this paper investigated attempted to investigate factors influencing adoption major post-harvest handling practices of large cardamom sub-sector in eastern Himalayan road corridor of Nepal considering major production and marketing problems faced by farmers.

2. Literature review on adoption decisions

There exists massive literature on factors that influence agricultural technology and post-harvest practices adoption. According to Loevinsohn et al. (Citation2012), farmers’ decisions about whether and how to adopt new innovative technology are conditioned by the dynamic interaction between characteristics of the technology itself and the array of conditions and circumstances. The explanatory variables were selected on the basis of the technology adoption literature and organized them into four major categories, namely, farmers’ characteristics, farm assets/resource, institutional factors and extension factors.

1) Farmers’ characteristics: Age, gender, experience of household head and migration status of household members to abroad for better job opportunity were explanatory variables included in this category based on empirical findings and past adoption-related literature. Human capital of the farmer is assumed to have a significant influence on farmers’ decision to adopt major post-harvest practices of large cardamom. Most adoption studies have attempted to measure human capital through the farmer’s age, gender, experience and household size (Asfaw et al., Citation2012; Fernandez-Cornejo et al., Citation2007; Ghimire & Huang, Citation2015; Kattel, Citation2015a, Citation2015b; Keelan et al., Citation2009; Mignouna et al., Citation2011). Age was also assumed to be a determinant of adoption of new technology. Older farmers are assumed to have gained knowledge and experience over time and are better able to evaluate technology information than younger farmers (Kariyasa & Dewi, Citation2011; Mignouna et al., Citation2011). On the contrary, age has been found to have a negative relationship with adoption of technology (Mauceri et al., Citation2005; Udimal et al., Citation2017). Thus, the expected sign of the coefficient on age variable is indeterminate.

Gender issues in agricultural technology adoption have been investigated for a long time and most studies have reported mixed evidence regarding the different roles of men and women played in technology adoption. Morris and Doss (Citation1999) had found no significant association between gender and probability to adopt on technology in Ghana. Lavison (Citation2013) indicated that male farmers were more likely to adopt organic fertilizer compared to female. Dummy variable for the gender of the household head was included to capture the gender difference in adoption decisions of post-harvest practices. In developing countries like Nepal, male farmers are expected to be more likely to adopt new innovation because women in Nepal have very limited access to resources such as land, capital and extension (Gartaula et al., Citation2012; Ghimire & Huang, Citation2015). The expected sign on the coefficient of experience is positive while farmers are getting more knowledge on adoption of large cardamom post-harvest practices with their greater experience in farming. Households with migrated members had positive impact on adoption (Poudel et al., Citation2018). In the present context of Nepal, labour migration towards the other countries for searching income opportunities is in increasing trend and households received financial capital from migrated members, they can invest on new technology from receiving remittance from abroad. The expected sign of migrations is positive coefficient.

2) Farm assets/resource: Variables included were commercial scale of large cardamom producers, livestock holding, types of house, risk averse type of farmers, household food security status and annual household income from large cardamom. The commercial scale of large cardamom producers is expected to have positive impact on adoption. Farmers with large land holding of large cardamom are more likely to adopt post-harvest handling practices than those with small holding because farmers with large landholding can afford to devote part of their land to try out the new technology (Ghimire & Huang, Citation2015; Mariano et al., Citation2012). Farmer with high number of livestock holding is expected to have positive impact on adoption of post-harvest practices. Farmers with cemented (Pakki) house are expected to have positive impact on adoption with indicator of high-income status. The risk-averse farmers and year-round food security are expected to have positive impact on technology adoption decisions. The expected sign of farm income on adoption decision is positive (Kattel, Citation2015b). Food security status of household has positive impact on adoption of post-harvest practices. In this context, resource endowment of farmers and their income-generating capacity are expected to have a positive impact on the likelihood of adoption of new technologies and practices (Yaron et al., Citation1992).

3) Institutional factors: Access to credit and membership in any organization variables were included in this category. Access to credit and membership are expected to have positive impact on post-harvest practices adoption decisions. Access to credit has been reported to stimulate technology adoption (Mohamed & Temu, Citation2008; Udimal et al., Citation2017). It is believed that access to credit promotes the adoption of risky technologies through relaxation of the liquidity constraint as well as through the boosting of household’s risk-bearing ability (Simtowe & Zeller, Citation2006). Kafle (Citation2011) confirmed that access to credit can increase the probability of adoption of agricultural new technologies by offsetting the financial shortfall of the households in Nepal. Farmers within a social group and organization learn from each other about adoptions the benefits and usage of a new technology (Conley & Udry, Citation2010; Ghimire & Huang, Citation2015). Uaiene et al. (Citation2009) suggested that social network effects are important for individual decisions, and that, in the particular context of agricultural innovations, farmers share information and learn from each other. Katungi and Akankwasa (Citation2010) found that farmers who participated more in community-based organizations were likely to engage in social learning about the technology hence raising their likelihood to adopt the technologies.

4) Extension factors: These variables included in this category were access to technical and extension services and training received. Access to technical service and training received are expected positive coefficient for post-harvest practices adoption. Many scholars have reported a positive relationship between technical-extension services and technology adoption (Genius et al., Citation2014; Karki & Siegfried, Citation2004; Mignouna et al., Citation2011; Uaiene et al., Citation2009). The training dummy variable has a positive impact on farmers’ decision on technology adoption (Kattel, Citation2015a, Citation2015b).

3. Methodology

3.1. Study site and sample

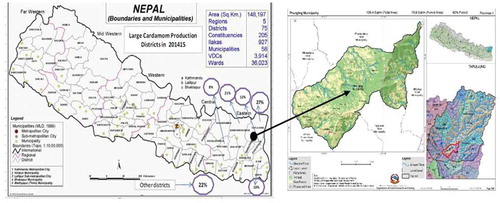

Both quantitative and qualitative data were collected from Phungling Municipality, Taplejung district in March to June, 2019. Taplejung district was chosen purposively for two reasons: firstly, Taplejung district along shared about more than 45% total large cardamom production in Nepal and, secondly, many large cardamom traders and organization like ICIMOD’ Himalica Project and UNNATI-Inclusive Growth Program have been focused on postharvest management and large cardamom-based agribusiness promotion especially in Phungling municipality. The study site map is presented in Figure . Following formula was used to determine sample size in the study area (Israel, Citation1992):

where n is sample size, N is total household of the study area those who were producing large cardamom and e is precision level (5%). The farm household survey was conducted through a semi-structured survey interview of 300 farm households.Footnote2 The sampling framework was prepared from total household population of 2993 (50% of the total 5986 households were producing large cardamom in Phungling municipality). Total 10% of samples were taken using simple random sampling technique. Furthermore, two community-level focus group discussions (FGDs) and Key informant Interview (KII) were done to validate collected information. The FGDs provided qualitative information for understanding farmers’ perspective on adopting or not adopting the improved method of large cardamom drying and curing, and those information were considered while designing the survey instrument. Collected data were analyzed by using statistical software STATA (version 14.0).

3.2. Empirical method using SUR Logit model

In order to better understand adoption decisions of post-harvest practices of large cardamom, namely improved method of large cardamom drying (bhatti), curing, cleaning, tail (calyx) cutting and grading based on color and size, a set of econometric model was specified and estimated using seemingly unrelated regression (SUR) logit.

Logit regression is used to investigate the determinants of the farmers’ decisions whether they adopt major post-harvest upgrading practices of large cardamom or not. The decision may be influenced by an “asset bundle” comprises physical, natural, human, social, institutional, technical and financial assets (Conley & Udry, Citation2010; Ghimire & Huang, Citation2015; Kafle, Citation2011; Kattel, Citation2015a, Citation2015b; Katungi & Akankwasa, Citation2010; Negera, Citation2015; Udimal et al., Citation2017). Thus, a logit model was used for the analysis of binary responses and it allows one to examine how a change in any independent variable changes all the outcome probabilities (Hosmer & Lemeshow, Citation2000). In general, the results are reasonably robust to change in the set of explanatory variables included in the regression. Thus the relationship between the discrete variable and a parameter is non-linear. In the basic model, let Yi be the binary response of a large cardamom farmer taking one of two possible values: Yj = 1 if the farmers decide to adopt five major post-harvest practices (j = 1 … 5) and Y = 0 if not. Suppose x is a vector of explanatory variables contributing to the adoption decision and β a vector of slope parameters, measuring the changes in x on the probability of the farmers’ decision to adopt post-harvest practices. Thus, the probability of adopting the technology then expressed as (Hosmer & Lemeshow, Citation2000):

Where;

The logit transformation of the probability of adoption decision of the post-harvest practices of large cardamom, P (Yi = 1) can be represented as follows (following Gujarati, Citation2003):

Where;

Yi = (Adoption of Post-harvest practices) Dichotomous dependent variable

Xi = Vector of variables included in the logit model,

βi = Parameters to be estimated,

= error term of the model,

exp (e) = base of natural logarithms (ln),

Li = Logit and Pi/(1- Pi) = Odd ratios.

Here, same explanatory variables (variables affecting adoption large cardamom post-harvest practices) determined the different dependent variables (major five post-harvest upgrading practices), so the seemingly unrelated regression (SUR) logit model was used to gauge the factor affecting five major post-harvest handling practices, using the functional form of logit model expressed by Gujrati and Porter (Citation2004) as:

where j =1, 2, 3, 4, 5 denote the five types of post-harvest practices. In EquationEquation (3)(3)

(3) the assumption is that a rational ith farmer has a latent variable, Yij which captures the unobserved preferences or demand associated with the jth choice of large cardamom post-harvest handling practices (j = adoption of five major practices, Yes =1). Given the latent nature of Yij* the estimations are based on observable binary discrete variables Yij which indicate whether or not a farmer undertook a particular large cardamom post-harvest handling practices at farm level. β a vector of slope parameters, FC is farmer characteristics (age, gender, experience, migration), FA is farm assets/resource (commercial scale of production, livestock holding, type of house, risk-averse nature of farmer, household food security, income from large cardamom), IF is institutional factors (access to credit and membership in any organization, group and cooperative) and EF is extension factors (access to technical service and training received for production of large cardamom and marketing) (refer Table for detail description of these variables).

Table 1. Definition of variables in adoptions of post-harvest handling practices large cardamom the study area

4. Results and discussion

4.1. Descriptive analysis of variables

Table presents the post-harvest practices, socio demographic, economics, institutional and extension characteristics of large cardamom producing households in the study area. About 27% of large cardamom producers used the improved method of drying. About 62% of farmers used large cardamom cleaning, 73% for cleaning, 4% for tail cutting and 22% farmers used grading of large cardamom based on size and color in the study area. The average age of household head was 45.19 years whereas about 75% of household head were male. The large cardamom farming experience was 14 years whereas 15% household members were migrated abroad to better job opportunity.

Table 2. Descriptive analysis of variables in adoption of post-harvest practices in the study area

The proportion of farmers having more than one hectare of land used for large cardamom cultivation was about one-third whereas only one-third of them had followed the crop diversification practices (Table ). About one-fourth farmers had adopted the crops/income diversification practices in cardamom farm (growing fruits kiwi, banana, citrus, bee keeping etc.). In study area, an average livestock holding was 2.54 livestock standard unit. About 53% households had concrete (Pakki) type of house. Thirty five per cent households in the study area had year round food security from own production. Average annual household income from large cardamom was Nepalese Rupees [NRs.] 242,449 with share of about 60% total annual household income.

About 57% households had access to credit facility. About 87% had a membership from group, cooperative or any other organization. In case of access to technical services, about 45.4% households had access to services related to large cardamom production and marketing. About 39% households had received training facility related to large cardamom production, marketing and post-harvest handling practices in the study area (Table ).

4.2. SWOT analysis of large cardamom production and marketing

Strength, weakness, opportunities and threats (SWOT) analysis of large cardamom in eastern Himalayan corridor is presented in Table . There were a number of trader routes, the hilly terrain and poor infrastructure and poor upgrading practices were main hindrances in large cardamom trade. Diseases and pest, price variation, lack of improved drying, curing and packing methods at farm level, many collectors and high market margin were major constraints and threats in large cardamom value chain development. The SWOT analysis indicated that there were lots of challenges of large cardamom production and marketing in Nepal, albeit with lots of avenues for possible opportunities for global value chain promotion of Nepalese large cardamom.

Table 3. SWOT analysis of large cardamom production and marketing in study area

4.3. Econometric model to assess adoption decision of improved curing and drying

The Seemingly Unrelated Regression (SUR) logit model was used to investigate factors influencing adoption of five major post-harvest handling practices of large cardamom at farm level (refer Table ). Fourteen different explanatory variables were used to assess same explanatory variables that determined on the major five post-harvest handling practices.

Table 4. Factors influencing adoption decisions of major post-harvest practices of large cardamom using SUR logit

The experience, commercial scale of large cardamom production, farm income, access to credit and access to technical and extension services were found positively and statistically significant on adoption of improved method of drying in logit model. Age, experience, risk averse, farm income, access to credit and training were found statistical significance on adoption decision of large cardamom curing whereas gender, experience, house type, farm income, membership, access to credit and training were statistically significant impact on adoption on cleaning of large cardamom. Large cardamom capsules tail cutting decisions and adoption at farm level were determined significantly by age and membership. In case of large cardamom grading based on color and size, age, experience, livestock holding, house type, member and training were significantly impact in logit model.

Age had negative impact on curing (p <0.001) and large cardamom tail cutting (p <0.1) whereas it had positive impact on cardamom grading based on color and size (p <0.001). Different findings show different results, some showed positive and some negative. Age showed no significant effect on adoption. The adoption of farm practices was not determined by the age of the respondents (Ekepu & Tirivanhu, Citation2016; Farid et al., Citation2015). Subedi et al. (Citation2019), Udimal et al. (Citation2017), and Ayalew (Citation2003) reported that age of household head showed negative relation with new technology adoption decisions. Younger farmers are more flexible and could like to adopt new technology and more innovative than older once (Asfaw et al., Citation2012; Ghimire & Huang, Citation2015; Udimal et al., Citation2017). On the other hand, older farmers may have experience and resource that would allow them more possibilities for trying a new technology whereas in case of younger farmers, they are more likely to adopt new technology because they have had more schooling, more innovative and more exposure to access the new information than the older generation (Melesse, Citation2018). Further, Dasgupta (Citation1989) stated that the findings on the relationship between the age of farmers and their adoption behaviour are somewhat inconsistent.

Gender had positive impact on large cardamom cleaning (p <0.001). If household head was male, the probability of adoption of cleaning would be about 14% as compared to female-headed households. The male-headed households have more access to information to use innovation than female-headed households (Melesse, Citation2018). So, male-headed households adopt new agricultural technology more easily (Abunga et al., Citation2012). The existence of wealth difference between female-headed and male-headed households could be also the possible reason for the difference in adoption of agricultural new technologies. The male-headed households who had more wealth can easily afford the price of agricultural new technologies.

Migration had not significantly impacted on any post-harvest practices of large cardamom. Experience of large cardamom had positive impact on improved drying (p <0.1) and curing (p <0.05) whereas it had negative impact on cleaning (p <0.1) and grading (p <0.05). Farming experience was found to be positively associated with adoption of new recommended practice (Dhital & Joshi, Citation2016). Ekepu and Tirivanhu (Citation2016) reported that farming experience showed no significant effect on adoption decisions of agriculture technologies.

Commercial scale of large cardamom farming was positive and significant impact only on improved drying (p <0.1) among post-harvest practices. If farmer had one or more than one hectare large cardamom farming land, the probability of adoption decisions on improved drying would be about 12%. Size of landholding was found to have both negative and positive relationship with respect to adoption. Positive relation was found with adoption of modern agricultural technologies (Abunga et al., Citation2012; Ayalew, Citation2003; Ghimire & Huang, Citation2015). Farmers with small land may adopt land-saving technologies. Small farms have been argued to have high fixed costs thereby hindering technology adoption at farm level.

Livestock holding (LSU) had negative and significant impact on grading (p <0.1). House type showed negative and significant impact on cleaning (p <0.001) and negative impact on grading of large cardamom. Risk averse nature of farmer showed positive and significant impact on curing (p <0.05) among post-harvest upgrading practices. If farmers had risk averse nature and adopting income diversification strategy, the probability of curing would be increased by 21%. Food security status of household had have no significant impact on any post-harvest practices adoption of large cardamom in the study area. Annual household income from large cardamom was positive and significant impact on improved drying (p <0.05) and cleaning (p <0.1) whereas negative impact on curing (p <0.001). The probability of adoption of improved method of drying would be increased by about 9% if income increased by 1%.

Among the institutional variables used in the logit model, access to credit had positive and significant effect on adoption of improved method of drying (11% at p <0.1) and curing (42.7% at p <0.001) whereas membership was positive and significant impact on cleaning (39.4% at p <0.001) and grading (10.9% at p <0.05), however negative and significant impact of membership was found on cleaning (19.5% at p <0.1). The credit variable had a positive correlation with the adoption of new agricultural technologies (Abunga et al., Citation2012; Ekepu & Tirivanhu, Citation2016; Udimal et al., Citation2017). Giving subsidies and providing the agricultural credit at low interest rate promote the adoption of recently released agricultural technologies (Subedi et al., Citation2019). Kafle (Citation2011) confirmed Access to credit can increase the probability of adoption of agricultural new technologies by offsetting the financial short fall of the households.

Many literature showed the positive relationship of membership in any organizations and farmers decision to adopt new technologies (Dhital & Joshi, Citation2016; Katungi & Akankwasa, Citation2010; Subedi et al., Citation2019). Farmers in group tend to come together with a commitment and with sense of direction and plan for the future. They learn together and collectively bargain for opportunities, so they can adopt the appropriate technologies. They exchange skill, knowledge and information among each other and also with the external sources of information. These types of farmers adopt the new technology faster.

Access to technical services related to large cardamom production and marketing, it had positive and significant effect on adoption of improved method of drying (12.8% at p <0.05) whereas negative impact on cleaning (29.2% at p <0.001). Training received was positive and significant impact on adoption of cleaning (18.4% at p <0.001) and grading based on color and size of large cardamom capsules (24.2% at p <0.001) whereas negatively and significant effect on curing (25.1% at p <0.001). Positive and significant influence of the frequency of contact of farmer with personal localite source of information on adopting the recommended technology (Abunga et al., Citation2012; Ayalew, Citation2003; Dhital & Joshi, Citation2016; Ekepu & Tirivanhu, Citation2016). Good extension contacts for the farmers influences the level of technology dissemination and adoption. Participation in training, demonstration, field days creates the platform for acquisition of the relevant information that promotes technology adoption. Access to technology balance negative effect of lack of formal education and reduces uncertainty about technology’s performance. Furthermore, many literature showed the positive impact of training received on technology adoption decisions made by farmers in agriculture sector (Kattel, Citation2015a, Citation2015b).

5. Conclusion and policy implication

Adoption of major post-harvest practices of large cardamom was found to be affected by socio-economic circumstances and institutional effectiveness. Majority of post-harvest practices for value addition was done by traders in case of large cardamom in Nepal. Results from an adoption model identified experience, household income from large cardamom, commercial scale of production, risk averse, access to credit, access to technical services and training received were found significant impact on adoption major post-harvest practices of large cardamom.

This study suggested that promotion of major post-harvest practices mainly improved method of drying, curing, cleaning, tail cutting and grading would be needed at farm level to increase the income of farmers and to capture competitiveness of large cardamom in global market. Results of this research provide information that is important in national policy making. Moreover, the government would consider short-term strategies that offset post-harvest management practices of large cardamom to capture net social benefits and competitiveness of quality products in the global market. Lastly, government interventions to improve the training, access to credit and technical service facility as well as encourage more profit-oriented behavior by farmers are necessary to enhance technology adoption of post-harvest practices of large cardamom in the long-run.

Authors’ contributions

Rishi Ram Kattel designed and executed research plan. Moreover, he analyzed the data and prepared the manuscript. Prof. Dr. Punya Prasad Regmi, Prof. Dr. Moha Dutta Sharma and Adjunct Prof. Dr. Yam Bahadur Thapa advised and provided comments and feedback to finalize this manuscript. All authors approved the manuscript.

correction

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by Directorate of Research and Extension from Agriculture and Forestry University, Nepal. We would like to extend our gratitude to Prof. Dr. Naba Raj Devekota for his valuable comments and feedback to improve this manuscript. We are also deeply indebted to the farmers and large cardamom traders in our study area, who are too numerous to mention individually, but without whose cooperation this study would not have been possible. Errors, if any, are entirely our own.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Rishi Ram Kattel

Rishi Ram Kattel is an academic with extensive practical and field experience within the agriculture sector in Nepal. He is an Assistant Professor and PhD Scholar at the Department of Agricultural Economics and Agribusiness Management, Agriculture and Forestry University (AFU), Rampur, Chitwan, Nepal. Kattel holds a Master's Degree in Agricultural Economics from the Leibniz University Hannover, Germany in 2009. His area on research interest includes value chain analysis, agribusiness management and agricultural economics.

Punya Prasad Regmi

Punya Prasad Regmi is Vice-chair of Planning Commission of Karnali Province and Professor at Department of Agricultural Economics and Agribusiness Management, AFU, Nepal.

Moha Dutta Sharma

Moha Dutta Sharma is a Professor at Department of Horticulture, AFU, Nepal. He has a PhD Degree in Horticulture Science.

Yam Bahadur Thapa

Yam Bahadur Thapa is an Adjunct Professor at Department of Agricultural Economics and Agribusiness Management, AFU, Nepal. He has awarded with a PhD in Economics.

Notes

1. bhatti is a place/house for large cardamom curing and drying and it is also known as kiln.

2. Farm household is defined as one where a group of individuals related by blood or marriage live on the same premises, share a kitchen and practice agriculture farming system.

References

- Abunga, M., Emelia, A., Samuel, G., & Dadzie, K. (2012). Adoption of modern agricultural production technologies by farm households in Ghana: What factors influence their decisions ? Journal of Biology, Agriculture and Healthcare, 2(3), 1–17.

- Adhikari, P., & Sigdel, K. (2015). Activities of cardamom development centre and DoA in large cardamom development. In R. Chaudhary & S. Prasad Vista (Eds.), Proceedings of the Stakeholders Consultation Workshops on Large cardamom Development in Nepal held in April 20, 2015. Commercial Crop Division, NARC.

- Asfaw, S., Shiferaw, B., Simtowe, F., & Lipper, L. (2012). Impact of modern agricultural technologies on smallholder welfare: Evidence from Tanzania and Ethiopia. Food Policy, 37(3), 283–295. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2012.02.013

- Avasthe, R. K., Singh, K. K., & Tomar, J. S. (2011). Large cardamom (Amomum subulatum Roxb.) based agroforestry systems for productions, resource conservation and livelihood security in the Sikkim Himalayan. Indian Journal of Soil Conservation, 39(2), 155–160.

- Ayalew, A. W. (2003). Factors affecting diffusion and adoption of agricultural innovations among farmers in Ethiopia case study of Oromia Regional State Western Shewa. Journal of Medicine and Biology, 1(2), 54–66.

- Bhutia, P. H., Sharangi, A. B., Lepcha, R., & Yonzone, R. (2018). Post-harvest and value chain management of large cardamom in hills and uplands. International Journal of Chemical Studies, 6(1), 505–511.

- Chapagain, D. (2011). Assessment of climate change impact on large cardamom and proposed adaptation measures in eastern hill of Nepal. Ministry of Environment.

- Conley, T. G., & Udry, C. R. (2010). Learning about a new technology: Pineapple in Ghana. The American Economic Review, 100(1), 35–69. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.100.1.35

- Dasgupta, S. (1989). Diffusion of agricultural innovations in village India. Wiley Western Limited.

- Dhital, P. R., & Joshi, N. R. (2016). Factors affecting adoption of recommended cauliflower production technology in Nepal. Turkish Journal of Agriculture - Food Science and Technology, 4(5), 378–383. https://doi.org/10.24925/turjaf.v4i5.378-383.637

- District Agriculture Development Office (DADO). (2017). Annual agriculture development programme and statistics books of Taplejung District. District Agriculture Development Office (DADO), Taplejung district profile.

- Ekepu, D., & Tirivanhu, P. (2016). Assessing socio–economic factors influencing adoption of legume-based multiple cropping systems among smallholder Sorghum Farmers in Soroti, Uganda. South African Journal of Agricultural Extension, 44(2), 195–215.

- Farid, K. S., Tanny, N. Z., & Sarma, P. K. (2015). Factors affecting adoption of improved farm practices by the farmers of Northern Bangladesh. Journal of the Bangladesh Agricultural University, 13(2), 291–298. https://doi.org/10.3329/jbau.v13i2.28801

- Federation of Large Cardamom Enterprenuers of Nepal (FLCEN). (2016). Federation of large cardamom entrepreneurs of Nepal.

- Fernandez-Cornejo, J., Mishra, A., Nehring, R., Hendricks, C., Southern, M., & Gregory, A. (2007). Off-farm income, technology adoption, and farm economic performance [ Agricultural Economics Report No. 36]. USDA ERS.

- Gartaula, H., Niehof, A., & Visser, L. (2012). Shifting perceptions of food security and land in the context of labour out-migration in rural Nepal. Food Security, 4(2), 118–194. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-012-0190-3

- Genius, M., Koundouri, M., Nauges, C., & Tzouvelekas, V. (2014). Information transmission in irrigation technology adoption and diffusion: Social learning, extension services and spatial effects. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 96(1), 328–344. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajae/aat054

- Ghimire, R., & Huang, W.-C. (2015). Household wealth and adoption of improved maize varieties in Nepal: A double-hurdle approach. Journal of Food Security, 7(6), 1321–1335. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-015-0518-x

- Government of Nepal / International Trade Centre (GoN/ITC). (2017). Nepal national sector export strategy large cardamom 2017-2021. Government of Nepal (GoN)/ International Trade Centre (ITC). https://moics.gov.np/media/Resources/Strategy/Large_Cardamom_1508652892.pdf.

- Gujarati, D. N. (2003). Basic Econometrics. McGraw-Hill.

- Gujrati, D. N., & Porter, D. C. (2004). Basic econometrics. McGraw-Hill.

- Hosmer, D. W., & Lemeshow, S. (2000). Applied logistic regression (2nd ed., pp. 373). John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

- Israel, G. (1992). Sampling, the evidence of extension program impact, evaluation and organizational development. IFAS: University of Florida.

- Kafle, B. (2011). Factors affecting adoption of organic vegetable farming in Chitwan District, Nepal. World Journal of Agricultural Sciences, 7, 604–606.

- Kariyasa, K., & Dewi, A. (2011). Analysis of factors affecting adoption of integrated crop management farmer field school (ICM-FFS) in swampy areas. International Journal of Food and Agricultural Economics, 1(2), 29–38.

- Karki, B., & Siegfried, B. (2004). Technology adoption and household food security; analyzing factors determining technology adoption and impact of project intervention: A case of smallholder peasants in Nepal. Conference Paper in The Deutscher Tropentag held on 5-7 October, 2004. Humboldt University.

- Kattel, R. R. (2015a). Adoption of technology upgrading by rural smallholders in the Nepalese coffee sector. Sukkur IBA Journal of Management and Business, 2(2), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.30537/sijmb.v2i2.91

- Kattel, R. R. (2015b). Rainwater harvesting and rural livelihoods in Nepal. South Asian Network for Development and Environmental Economics (SANDEE) Working Paper No. 102-15.

- Katungi, E., & Akankwasa, K. (2010). Community-based organizations and their effect on the adoption of agricultural technologies in Uganda: A study of banana (Musa spp.). Pest Management Technology, National Banana Research Program, Acta Hort., 879, ISHS.

- Keelan, C., Thorne, F. S., Flanagan, P., Newman, C., & Mullis, E. (2009). Predicted willingness of Irish farmers to adopt GM technology. AgBioForum, 12(3 & 4), 394–403.

- Lavison, R. (2013). Factors influencing the adoption of organic fertilizers in vegetable production in Accra [Msc Thesis]. Accra Ghana.

- Loevinsohn, M., Sumberg, J., & Diagne, A. (2012). Under what circumstances and conditions does adoption of technology result in increased agricultural productivity? Protocol. EPPI Centre, Social Science Research Unit, Institute of Education, University of London.

- Madhusoodanan, K. J., & Rao, Y. S. (2001). Cardamom (large). In K. V. Peter (Ed.), Handbook of Herbs and Spices (Vol. 1, pp. 139). Woodhead.

- Mariano, M. J., Villano, R. A., & Fleming, E. (2012). Factors influencing farmers’ adoption of modern rice technologies and good management practices in the Philippines. Agricultural Systems, 110(2012), 41–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2012.03.010

- Mauceri, M., Alwang, J., Norton, G., & Barrera, V. (2005). Adoption of integrated pest management technologies: A case study of potato farmers in Carchi, Ecuador: Selected Paper prepared for presentation at the American Agricultural Economics Association Annual Meeting, Providence, Rhode Island, July 24-27, 2005.

- Melesse, B. (2018). A review on factors affecting adoption of agricultural new technologies in Ethiopia. Journal of Agricultural Science and Food Research, 9(3), 1–4.

- Mignouna, B., Manyong, M., Rusike, J., Mutabazi, S., & Senkondo, M. (2011). Determinants of adopting imazapyr-resistant maize technology and its impact on household income in Western Kenya. AgBioforum, 14(3), 158–163.

- Ministry of Agriculture Development (MoAD). (2017). Statistical Information on Nepalese Agriculture. Government of Nepal, Ministry of Agricultural Development, Monitoring, Evaluation and Statistics Division Agri Statistics Section.

- Mohamed, K., & Temu, A. (2008). Access to credit and its effect on the adoption of agricultural technologies: The case of Zanzibar. African Review of Money Finance and Banking, 45–89.

- Morris, M. L., & Doss, C. R. (1999). How does gender affect the adoption of agricultural innovations? The case of improved maize technology in Ghana [Paper presentation]. Annual Meeting, American Agricultural Economics Association (AAEA), Nashville, Tennessee, August 8-11.

- Negera, D. G. (2015). Analysis of factors determining the supply of Ethiopian cardamom spice (Aframomumcorrorima): A case from Bench Maji Zone of SNNPR, Ethiopia. European Journal of Business and Management, 7(1), 56–63.

- Poudel, G. P., Shah, M., Khandelwal, P., & Justic, S. E. (2018). Determinants, impacts and economics of reaper adoption in the rice-wheat systems of Nepal. Agriculture Development Journal, 14, 63–72.

- Ranjan, P., Achom, J., Prem, M., Chettri, S., Lepcha, P. T., & Marak, T. B. (2018). Study of different drying methods effect on quality of large-cardamom (Amomum Subulatum Roxb.) capsules. An International Refereed, Peer Reviewed & Indexed Quarterly Journal in Science, Agriculture & Engineering, VII(XXV), 182–186.

- Sharma, G., Sharma, R., & Sharma, E. (2009). Traditional knowledge systems in large cardamom farming: Biophysical and management diversity in Indian mountainous regions. Indian Journal of Traditional Knowledge, 8(1), 17–22.

- Simtowe, F., & Zeller, M. (2006). The impact of access to credit on the adoption of hybrid maize in Malawi: An empirical test of an agricultural household model under credit market failure. MPRA Paper No. 45.

- Singh, A. I., & Pothula, A. K. (2013). Postharvest processing of large cardamom in the Eastern Himalayan. Mountain Research and Development, 33(4), 453–462. https://doi.org/10.1659/MRD-JOURNAL-D-12-00069.1

- Subedi, S., Ghimire, Y. N., Adhikari, S. P., Devkota, D., Poudel, H. K., & Sapkota, B. K. (2019). Adoption of improved wheat varieties in eastern and western Terai of Nepal. Journal of Agriculture and Natural Resources, 2(1), 85–94. https://doi.org/10.3126/janr.v2i1.26047

- Uaiene, R., Arndt, C., & Masters, W. (2009). Determinants of agricultural technology adoption in Mozambique. Discussion papers No. 67E.

- Udimal, T. B., Jincai, Z., Mensah, O. S., & Caesar, A. E. (2017). Factors influencing the agricultural technology adoption: The case of improved rice varieties (Nerica) in the Northern Region, Ghana. Journal of Economics and Sustainable Development, 8(8), 137–148.

- Yaron, D., Dinar, A., & Voet, H. (1992). Innovations on family farms: The Nazareth Region in Israel. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 74(2), 361–370. https://doi.org/10.2307/1242490