?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This study attempted to investigate the determinants of small-scale farmers’ participation decision and intensity of participation in the fruits (apple and mango) value chains in the Upper Blue Nile Basin, Ethiopia. Using a multi-stage sampling procedure, 384 growers were selected at random to participate in the survey. A structured household survey was the main tool for data collection. Descriptive statistical methods and the double-hurdle model were employed in the analysis. Our study finds that the probability of a household being participating in the apple value chain increases with household head education level, experience, extension contacts, and membership in local cooperatives, while decreases with household size and incidence of disease and insect pests. Results further showed that mango plot size and membership in local cooperatives increase the probability of participation decisions in the mango value chain. Moreover, households’ intensity of participation in the apple value chain increases with education level and extension contacts, whereas age squared and distance to the nearest market decrease their intensity of participation in the mango value chain. Our findings suggest that policies aimed at improving rural infrastructure (roads and markets), price information systems, human capital, and promotion of farmers’ cooperatives, as well as access to disease and insect pest control mechanisms, could improve the participation of farmers in the fruits value chain.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

In addition to maintaining the ecological balance, fruit farming plays an important role in both generating income and nutritional improvement for nearly six million Ethiopian small-scale farmers. The country has a worthy potential in the production of high-value fruit crops such as apples and mangoes. Despite the production potential and importance of such high-value crops, the producer-market linkage is weak. This is due to demographic, institutional, socio-economic, and other related factors. This contribution is, therefore, an attempt made to enhance fruit farmers to reach agri-food value chains and actively engage in the high-value markets to increase their income and food security.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests regarding the work reported in this paper.

1. Introduction

New consumption patterns and preferences for high-value agricultural products (e.g., fruits) are emerging in developing countries due to rapid urbanization, improved incomes, and increased awareness of their nutritional values (Tschirley et al., Citation2015; Wiggins, Citation2014). This has further triggered changes in dynamism and transformation processes of the local agri-food systems with positive implications on small-scale farmers’ integration into market-oriented value chains (Blandon et al., Citation2009; Lowitt et al., Citation2015; Reardon, Citation2015). Participation in improved local agri-food chains may offer small-scale farmers the opportunity to produce and sell high-value products, translating their vertically-coordinated relationships into premium prices and letting them capture a bigger share of the price paid by final consumers (Hussein & Suttie, Citation2016; De Janvry & Sadoulet, Citation2020; Kilelu et al., Citation2017). Indeed, there is evidence in Ethiopia, as is elsewhere in sub-Saharan Africa, increased access and participation of small-scale farmers in high-value markets present opportunities to improve their productivity, income, food security, and reduce poverty (Belay, Citation2018; Sharp et al., Citation2007).

In rural areas of Ethiopia, as such, high-value markets (e.g., fruits) play an important role in the social and economic development of small-scale farmers’ due to poorly functioning markets with high transaction costs; this often deters their market participation and promotes mainly own consumption (Worako, Citation2015). Realizing the underexploited opportunities that could be offered by the fruit sector, the Ethiopian government has been facilitating fruit development as one of the main development strategies for poverty reduction and improvement in social and economic growth, and several measures have been put in place to enhance small-scale farmers’ access to such markets. For instances, as part of its commercialization support programs, the government of Ethiopia in collaboration with non-governmental organizations (e.g., German Development Cooperation, MASHAV) has been supporting the fruit sector through various ways: (a) targeting major growth corridors and providing necessary technical, budgetary, and facilitation assistance, (b) strengthening extension system to improve small-scale farmers adoption of improved technologies (e.g., irrigation expansion, grafted seedling supply, agronomic management activities), and market-oriented production systems, and (c) development of agro-industrial parks (e.g., Burie agro-industrial park constructing around study areas) (ATA, Citation2017).

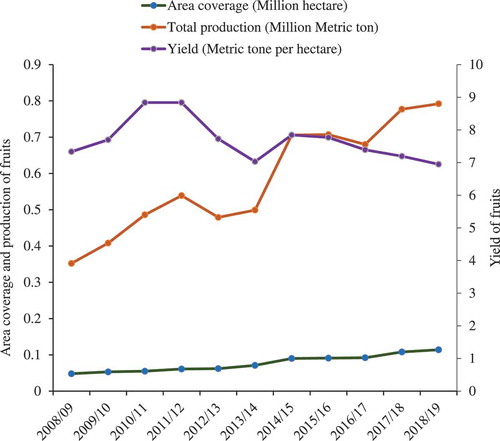

Due to these efforts, despite fluctuations in the area planted with fruits and their production in recent years, significant growth has occurred in both (Figure ). In 2019, close to 114,421.81 hectares of land was covered under fruit crop production and, more than 7,924,306.92 quintals of fruits were produced in the country. The area under fruits cultivation and volume of fruits production increased during 2008–2019 by 138 and 125%, respectively. Observed production fluctuations are attributed to erratic weather conditions, shortage of water, an infestation of pests and disease, and poor post-harvest management (CSA, Citation2019).

North-western Ethiopia, particularly the Upper Blue Nile Basin, is agro-ecologically suitable and known for its production potential of different types of fruits (EIAR, Citation2013). Currently, apple and mango productions are expanding across the basin (MoA, Citation2014). In the basin context, fruit crops are gradually transforming from subsistence to cash crops for small-scale farmers. However, small-scale producers are usually forced to sell their produce at lower prices (Girmay et al., Citation2014). Given the weak organization of fruit markets, most small-scale producers market their produce through middlemen such as collectors and street vendors, who may retain the highest marketing margin than producers (Getahun et al., Citation2018). For instance, during our preliminary assessment, we have observed that small-scale farmers are selling mango and apple at a farm-gate price of 6 (six) and 20 ETB kg−1, respectively. However, in study districts, Bahir Dar and Enjibara, buyers are paying 25–30 ETB kg−1 for mango and 40–45 ETB kg−1 for apple.

Evidence suggests that participation of small-scale farmers in fruits value chain varies with respect to a range of social, economic, infrastructural, and institutional factors: Globally (Ao et al., Citation2019; Chang et al., Citation2014; Jaji et al., Citation2018; Slamet et al., Citation2017); in Africa (Adepoju et al., Citation2015; Ngenoh et al., Citation2019; Sigei et al., Citation2014); and in Ethiopia (Girmalem et al., Citation2019; Kassa et al., Citation2017; Mengesha et al., Citation2019; Tamirat & Muluken, Citation2018; Tarekegn et al., Citation2020; Tufa et al., Citation2014). However, the evidence vis-à-vis the importance of these factors in determining small-scale farmers’ participation in the fruits value chain activities is mixed. In other words, results from these studies vary depending on the product being considered, number and organization of available channels, and the institutional, technical, social and economic environment the farmers operate in. For example, a study by Temesgen and Hiwot (Citation2017) asserted that age and level of education “were factors which negatively and significantly influenced participation of farmers in the fruit value chains”, whereas Chala (Citation2010) found that both variables have positive and significant effect on the participation of farmers in the fruit value chain activities which shows a mixed result. In addition, Tadesse and Temesgen (Citation2019) reported that farming experience was negatively and significantly influenced participation of farmers in the fruit value chains, whereas Mengesha et al. (Citation2019) indicated that the variable has positive and significant effect on the participation of farmers in the fruit value chain activities which also shows a mixed result. Further Kassa et al. (Citation2017) reported that household size was positively and significantly influenced participation of farmers in the fruit value chains, whereas Girmalem et al. (Citation2019) indicated that the variable has negative and significant effect on the participation of farmers in the fruit value chain activities which as well shows a mixed result.

Moreover Tarekegn et al. (Citation2020) in their study reported that adequacy of extension services promotes fruit farmers participation decision in the value chain, whereas distance from market deters their participation; Girmalem et al. (Citation2019) got the same result and concluded that area allocated for mango fruit production indorses farmers intensity of participation in the output market. Likewise, proximity to road and asset ownership (Tarekegn et al., Citation2017), improved fruit variety utilization (Tarekegn et al., Citation2020), irrigation (Tufa et al., Citation2014), access to credit and off-farm income (Abafita et al., Citation2016; Girmalem et al., Citation2019; Kassa et al., Citation2017), gender (Ao et al., Citation2019; Tufa et al., Citation2014), and perishability (Regasa et al., Citation2019) influence fruit farmers participation decision and intensity of participation in the fruits value chain. Most of these studies in Ethiopia however, did not consider both participation decision and intensity of participation possibilities among small-scale fruit farmers.

While these studies offer useful insights into identifying production potentials and constraints, marketing supply channels, and distribution of margins and potential factors influencing value chain participation, they are limited in a number of ways. Firstly, these studies focus on Eastern Ethiopia (Tufa et al., Citation2014), Central Ethiopia (Getahun et al., Citation2018), Northern Ethiopia (Girmalem et al., Citation2019), and Southern Ethiopia (Kassa et al., Citation2017; Mengesha et al., Citation2019; Tarekegn et al., Citation2020), and thus may have limited contextual relevance (e.g., social, cultural, environmental) to north-western Ethiopia. Secondly, most of the studies mainly focus on value chains of cereal crops like rice, teff, sesame, and wheat (Abate et al., Citation2019; Biggeri et al., Citation2018; Gebremedhn et al., Citation2019; Habtewold et al., Citation2017; Kyaw et al., Citation2018; Warsanga & Evans, Citation2018). Thirdly, unlike Kassa et al. (Citation2017) and others, our study relied on the double hurdle model proposed by Cragg (Citation1971). This is because in this model non-participants are considered to a corner solution utility model (i.e. allows considering the characteristics of non-participants) whereas in the Heckman two-stage model non-participants will never participate under any circumstances (Beshir et al., Citation2012; Kahenge et al., Citation2020; Musah, Citation2013; Yami et al., Citation2013).

To this end, this study envisages investigating factors that affect small-scale farmers’ decisions to participate in the respective value chain, on the one hand, and the extent of participation (volume supplied), on the other hand, using a sequential market participation model. By doing so, the study contributes to evolving literature on farm households’ participation in fruit value chains.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 briefly describes materials and methods. Section 3 elaborates on the conceptual framework of the study, while section 4 presents and discusses the estimated results. Section 5 concludes.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study sites description

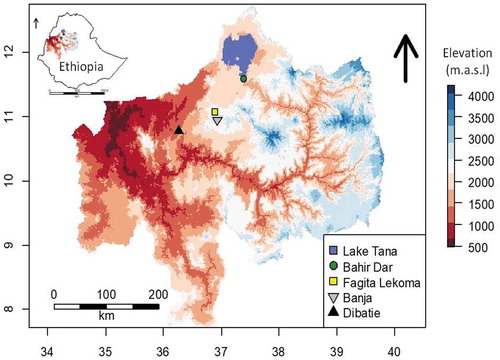

This study was carried out in the Dibatie district from the Benishangul-Gumuz Region, the Fagita Lekoma, Banja, and Bahir Dar Zuria districts from the Amhara Region, four districts in the north-western highlands of the Upper Blue Nile Basin, Ethiopia (Figure ). The livelihood of the communities in these districts is mainly comprised of a rain-fed mixed subsistence crop production-livestock farming system (Table ). Fruit crops such as apple and mango are also the most important contributors to agricultural activity and, hence, a focus for the development in the north-western highlands of Ethiopia. The basin has a high potential for fruit farming and, generally, it is considered as among the important fruit-growing corridors in the country (Nigussie et al., Citation2017; Teshager Abeje et al., Citation2019). The climate changes from humid (Fagita Lekoma and Banja) to semi-arid and arid zones (Dibatie and Bahir Dar Zuria). The annual rainfall pattern of the basin is ranging from 850 to 3465 mm depending on altitude. Table summarizes the biophysical characteristics of the study sites according to their order of elevation as low, mid, and high elevation.

Table 1. Biophysical characteristics of the study districts

2.2. Sampling technique and sample size determination

This study took the small-scale fruit producers of the four districts in the Upper Blue Nile Basin as the research subjects. Fruit producers mainly included growers of mango and apple fruits. To draw an appropriate sample, multi-stage sampling was applied to select participants for the study. In the first stage, four sample districts were chosen purposively from the Upper Blue Nile Basin based on their high potential for fruit production. These districts were selected in such a way that they can capture differences in agro-climatic zones, socio-economic conditions, and their experiences on fruit production. Accordingly, from the highland apple-producing areas Fagita Lekoma and Banja districts, from the midland mango producing areas Bahir Dar Zuria district, and from the lowland mango producing areas Dibatie district were selected. In the second stage, we have selected a total of ten sample kebeles (i.e. the smallest administrative unit below the district) by employing a simple random sampling technique. Accordingly, the following kebeles were selected: Dibatie 01, Dibatie 02, and Gallessa kebeles from Dibatie district; Laguna and Wonjeta kebeles from Bahir Dar Zuria district; Endewuha and Gafera kebeles from Fagita Lekoma district; Chewusa, Basanguna, and Bata kebeles from Banja district. Finally, respondents were proportionally selected by employing a simple random sampling technique. As a sampling frame, a list of farming households was obtained from the respective kebele agriculture offices and categorized them into participants and non-participants in the fruits value chain with the assistance of local informants. The sample size was determined using (Mugenda & Mugenda, Citation2003) table due to the reason that the total population size (N) is more than 10,000. Accordingly, n was determined as follows:

Where: n is the desired sample size when the population is more than 10,000; Z is standard normal deviation (1.96) corresponding to 95% confidence level; p is estimated characteristic of target population the researcher assumes (is the occurrence level of the phenomenon under study and is equal to 0.5 where the occurrence level will not know); and d2 is the desired level of precision or level of statistical significance/margin of error the researcher wills to accept (0.05).

Therefore, a sample (n) of 384 fruit-growing households was set on. Then after, 223 mango growers and 161 apple growers were proportionally allocated among the selected kebeles (Table ).

Table 2. Household distribution and sample intensity across the study districts

2.3. Data types, sources, and methods of collection

This study employed a cross-sectional research design, using mixed methods. Both quantitative and qualitative data were collected from primary and secondary sources. A preliminary questionnaire was designed through a review of the literature and with the assistance of key informants. To increase the reliability of data, triangulation approaches (such as semi-structured questionnaires, key informant interview guides, focus group discussion guides, and field observation) were used. The primary data used in this study came from individual small-scale apple and mango farmers survey, key informant interview, focus group discussion, and field observation by employing semi-structured questionnaires and checklists. The key informants were four horticultural experts, one from each district. The instrument was translated into Amharic, the local language, and it was then tested and refined through interviews with 35 fruit-growing farmers before the actual survey. The survey was conducted from November 2019 to January 2020 by trained enumerators. The survey provided information on household characteristics, ownership of assets, production systems, postharvest loss, socio-economic and institutional factors, marketing activities, and value addition practices. Secondary data were collected from the respected agricultural offices as well as from trade and revenue offices.

2.4. Conceptual framework

This study conceptualizes farmers’ decisions about whether to participate in the fruits’ value chain was reflected under the framework of utility maximization. The key assumption of this model is the decision of farm households is based on the principle of utility maximization (Norris & Batie, Citation1987). Specifically, in this study, a farmer is said to participate in the fruits’ value chain if s/he sells a part of her/his fruits output in the market. According to(McFadden, Citation1974), a household’s utility function from using alternative j then expressed as follows:

where; Uij — is the perceived utility attained by the ith small-scale apple/mango producer from participating in the respective value chain, Vij — is explainable part of Uij that depends on socio-economic attributes (Dij), farm characteristics (Cij), infrastructural and institutional factors (Iij), and the random error term (εij). Hence, subject to these attributes, farmers are expected to maximize their utility through participating in a given market chain only if participation is expected to be profitable (De Janvry et al., Citation2010). That is, each farm household chooses to partake in the value chain (if );

– is the farm household’s net benefit, Uij and Uik are utility from participation and non-participation, respectively, of the ith small-scale fruit producer. Since these utilities are unobservable, they can be expressed in EquationEquatoin (3)

(3)

(3) as a function of observable elements:

where, Yi — is the observed dependent variable, Xi — is a vector of explanatory variables, β — is a vector of parameters to be estimated, and ui — is an independent normally distributed error term with zero mean and constant variance. In general, this conceptual understanding leads us to select an appropriate model for analysis.

2.5. Analytical models

A two-step analytical approach is followed to determine small-scale farmers’ participation in the fruits value chain. The main reason for the adoption of such methods is that value chain participation involved two-way decisions: the decision to participate and the actual degree of participation. The two well-known models are the Heckman two-stage selection model and Cragg’s Double hurdle model (Komarek, Citation2010). Both regression models recognize that discrete outcomes are expressed by the selection and degree of participation decisions. Normally, in this study, not all farmers participated in apple and mango markets. Meaning: the farmers do not have fruit produce to supply to market or farmers have the product but not supply it to market. Hence, following Kahenge et al. (Citation2020) our study relied on the double hurdle model proposed by Cragg (Citation1971). This is because in the double hurdle model non-participants are considered to a corner solution utility model (i.e., allows considering the characteristics of non-participants) whereas in the Heckman two-stage selection model (Heckman, Citation1979) non-participants will never participate under any circumstances (Yami et al., Citation2013). The double hurdle model takes all the zero observations as corner solutions where a small-scale farmer assumed to be a seller of apple and mango with zero sales. By employing craggit command (Burke, Citation2009) in Stata software, the model combines a probit estimation in the first stage with a truncated regression in the second stage.

The participation equation is specified as:

where; - is a latent variable that takes 1 if the respondent participates in fruits value chain activity and, 0 otherwise; X — is a vector of independent variables; β — is a vector of parameters; εi — is the disturbance term which captures all unmeasured variables. The dependent variable used in this participation equation is: farm households participation decision in the fruits value chain (dichotomous; 1 = participant; else = 0).

The second hurdle (truncated regression), which closely resembles the Tobit model is specified according to Wooldridge (Citation2010) as:

Where, - represents the volume of mango and apple sold in quintal/year; Xi — is the independent variables; βi — is a vector of parameters; and ui — is the disturbance term. The dependent variable in this case is: intensity of farmers’ participation (continuous; quantity of mango and apple sold in quintal/year).

Data management was performed in SPSS ver. 24. Descriptive, inferential, and econometric techniques were employed to analyze the data collected from the respondents, using the Stata ver. 14.0. Descriptive statistics including percentage, frequency, mean, and standard deviation and inferential statistics consisting of t-test and chi-square tests were employed to analyze the data. For the econometric analysis, the double hurdle model was used to examine the factors influencing small-scale farmers’ participation in fruit value chains. Descriptions of the explanatory variables used for model analysis are presented in Table .

Table 3. Description and summary statistics of explanatory variables

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Description and summary statistics of variables

Description of variables and summary statistics for all dependent and explanatory variables included in the model as well as their level of significance for each variable for participants and non-participants are presented in Table .

3.2. Dependent variables

The decision to participate in the apple and mango value chains is a dichotomous dependent variable that takes the value one for households who participated in these fruits value chain whereas it takes the value zero otherwise. Likewise, the volume of apple and mango sales is a continuous dependent variable in the supply equation is measured in quintal (100 kg) and represents the actual supply by apple and mango farm households to the market in the survey year. With regard to participation categories, about 48.5 and 59.5% of apple and mango growers participated in the value chain as sellers of their produce, respectively. Households who participated in the apple and mango market sold an average of 2.0 and 18.2 quintals of apple and mango produce, respectively.

3.3. Explanatory variables

In the course of identifying determinants influencing apple and mango value chain participation decision and level of participation by small-scale farmers, the main task is to examine which determinant influences and how? Therefore, the potential explanatory variables were categorized into the household characteristics, farm characteristics, transaction costs variables, and institutional support variables which are supposed to influence value chain participation decision and quantity of apple and mango fruit supply to the market.

3.4. Household characteristics

Age is one of the demographic variables that are useful for describing households and providing insight into the sample’s age structure and population. The age of the head of the household, who is usually the decision-maker, is considered to be a crucial factor in influencing the decision of the household in agricultural activities, as it determines whether the household benefits from the experience of the elderly or has to base its decision on the attitudes of younger farmers to take risks. In our study, for those cultivating apples, the majority of the households (78.9%) were male-headed. The average age was about 49.6 years. Likewise, for those cultivating mangoes, the majority of the households (81.1%) were male-headed. The average age was about 46.5 years. With regard to participation categories, on average, non-participants were somewhat older than that of participant households in both apple and mango households. The result of an independent-sample t-test indicates that mean differences for apple households are statistically significant but insignificant for mango households.

Of the total sample of apple households, 78.9% were headed by men, while only 21.1% were headed by women, while 81.1% of mango households were headed by men, while only 18.9% were headed by women (Table ). Moreover, the Pearson chi-square test result indicated that participation in the mango value chain and sex is statistically significant. But there is no relationship between participation in the apple value chain and sex of the household. In addition, almost equal proportions of male-headed households were in the participants and non-participants categories of apple growers, whereas more than half male-headed household mango growers were non-participants. In addition, education is important both in the management of the business and decision-making (Kadigi, Citation2013). About 44.1% of apple respondents had attained the primary level of education, and about 14.2% had a secondary level of education. About 45.3% of mango respondents had attained the primary level of education, and about 17.4 % had a secondary level of education. Furthermore, the result of the chi-square test showed that there was a significant variation among respondents’ education levels. The average household size for the apple household was 5.8, whereas the average household size for the mango producer was 5.45.

The descriptive analysis highlighted that mean family labor (in man equivalent) was significantly greater for apple value chain participants than non-participants. However, there is no statistically significant difference between participant and non-participant mango growers. For the sample respondents, the man equivalent of the economically active labor of 15–64 years was calculated. Our study also finds that the average working labor (in man equivalent) of both apple and mango farmers was found to be 3.99 and 3.65, respectively. The result indicated that the average fruit farming experience for apple farmers was 8.1 years. Similarly, for those cultivating mangoes, the majority of the households (81.1%) were male-headed. The average age was about 46.5 years, with an average fruit farming experience of 9.65 years. The analysis of field data further underscores both apple and mango farming experience between the two groups was highly significant at a 1% level of significance.

3.5. Farm characteristics

The land is perhaps the most valuable resource, as it provides the basis for any economic activity, particularly in the agricultural sectors. In this study, the average-cultivated apple and mango landholding of respondents was found to be 0.09 ha and 0.21 ha, respectively. Statistically, the plot size of both apple and mango value chain participants were significantly larger than those of non-participants in respective the crop. With regard to livestock holdings, the average livestock size of apple farmers was 5.44 TLU, while that of mango farmers was 5.95 TLU. Not surprisingly, the mean differences in total livestock herd size between mango participants and non-participants were highly significant. But the reverse is true for apple value chain participants and non-participants. Moreover, about 37.3% of apple farmers and 42.1% of mango farmers reported that their fruits produce was damaged by wild animals (e.g., apes, baboons, and birds). Our descriptive findings further indicate that both disease and insect pests’ incidence and perceived wild animals as a serious problem are statistically significant.

3.6. Institutional support variables

In terms of willingness to participate in the apple and mango value chain, institutional variables have a significant effect on the observed status of farmers. In this study, the most likely institutions hypothesized to affect farmers’ participation in the apple and mango value chain include the frequency of extension contacts, membership of local cooperatives, and access to price information. Accordingly, the average frequency of extension contacts per year for apple farmers was 7.30, while that of mango farmers was 4.25. The differences in the average frequency of extension contacts per year between participants and non-participants were also statistically significant at the 1% level. Membership in local cooperatives was statistically significant between both groups. Further, the survey result indicated that 52.0% of apple farmers and 49.0% mango farmers had access to price information. Our result portrays that there was a statistically significant difference between both groups in terms of access to price information. Besides, almost equal proportions of participant households’ access to price information on their apple mango produce.

3.7. Transaction costs variables

The survey result showed that the average distance of apple farmers’ residence from the nearest market is greater (39.55 minutes of walking) than mango farmers’ residence (36.65 minutes of walking on foot). The t-test result indicates that the variable had a strong association with participation decisions in mango value chain participants than apple farmers. On average, value chain participants are closer to the market than non-participants. Ownership of mobile phones is important information communication equipment helps growers aware of up-to-date information regarding production and marketing activities. About 42.2 and 59.1% of apple and mango households have their own mobile phone, respectively. The differences in the ownership of mobile phones between participants and non-participants were statistically significant. Finally, ownership of transportation assets (equines and cart) offers more chances in finding marketing alternatives and encourages participating in the value chain. In our study, about 34.8% and 52.9% of apple and mango households have their own transport facility, respectively. The differences in ownership of transportation assets between participants and non-participants were statistically significant at the 1% level.

3.8. Distribution of respondents based on their production and marketing activities

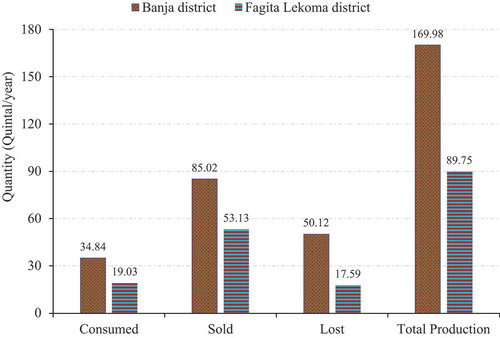

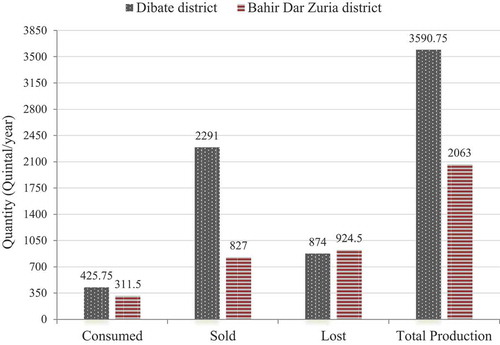

Our descriptive result, presented in Figures and , indicates that there are a significant number of apple and mango growers in the study districts, with a varied amount of production and marketing intensities. In both Dibatie and Bahir Dar Zuria districts (Figure ), a significant proportion of mango is brought to the market. This reaffirms the thought that products such as mango are cash crops or are produced primarily for the market. Our finding further underscores that in Dibatie district the amount of total mango production was larger than in Bahir Dar Zuria. Importantly, the size of wasted mango produce should not be overlooked.

Post-harvest wastage is hampering farmers from getting planned revenue, implying that about 31.8% of the total mango produce was lost. Most of us are not aware of such an enormous amount of food wasted in the value chain activities (i.e., from harvesting to consumption). Empirical findings supported this finding that fruits post-harvest losses are estimated at 20–40% in developing countries and 5–20% in developed countries. In Ethiopia, the principal reasons for mango produce losses are wind, birds, microorganisms, wounding, and maturity stage (Hussen & Yimer, Citation2013).

Figure 3. Distribution of respondents based on their mango practices

With regard to apple-growing districts, there are also growers with significant amounts of production levels. The total production in the Fagita Lekoma district is less than that of the Banja district. This might be due to poor implementation of common agronomic practices such as pruning and thinning, fencing, manuring, composting, pest control, and others. Post-harvest wastage is also hampering apple farmers from getting planned revenue, indicating that about 26.1% of the total apple produce was lost (Figure ). In general, there is a significant district-based difference between total production, consumption, selling, and loss of apple produce.

3.9. Agronomic and value-addition practices in the study districts

Table summarizes agronomic and value-addition methods employed by apple and mango growers among study districts. More than half of respondents in all study districts adopt intercropping of their apple and mango with other crops like maize and vegetables. Literature by (Dapaah et al., Citation2003) revealed that intercropping as compared to monocropping is a common practice applied worldwide as it improves the use of land efficiently, minimizes crop failure risks, reduces soil erosion, and increases yield stability. In terms of traditional methods used to control disease and insect pest infestations, about 39% of both apple and mango farmers were adopted different biological, chemical, and mechanical methods in the four study districts. From these adopters, in Dibatie district, the majority (12.0%) of mango growers applied intercropping as a traditional controlling mechanism, whereas in Bahir Dar district, 16.4% of mango producers adopted different controlling methods at a time (e.g., weeding and hoeing, spraying pesticide chemicals like diazinon, intercropping, and cultural methods).

Table 4. Agronomic and value addition methods adopted by growers among study districts

Moreover, the majority of (14.6%) apple growers in Fagita Lekoma district stated that weeding and hoeing were important means of controlling disease and insect pest infestations. Furthermore, value-addition as a core component of value chain study results from activities such as cleaning, sorting/grading, packaging, storing, transporting, and processing. Theoretically, rapid agricultural growth worldwide has been arising from post-production activities/value-added products (Punjabi, Citation2007). In developing countries, low agro-industrial expansion has mainly been the major cause of stagnation for the value addition of market-oriented crops (e.g., apple and mango). Among the surveyed farmers, the majority of mango growers were better in the adoption of value-addition activities on their produce than apple growers. Sorting and cleaning were reported to be the most adopted value-addition practices. Banja district, next to Dibatie, had the highest percentage of adopting value addition activities. Note, however, that a significant number of both apple and mango growers supplied their products to the market without any value addition activities (Table ). Our finding further indicates almost more than 90% of respondents from both apple-growing districts irrigate their apple farm. However, the variation is reported from mango growing districts. Implying that, less than half of respondents in Dibatie were not practiced in their mango farm, while in Bahir Dar Zuria the majority (91.4%) of respondents used irrigation.

3.10. Econometric model results and discussion

In section 4.1, the study presented the description of the sample respondent characteristics and test of association among the dependent and independent variables to determine factors influencing apple and mango growers’ participation in the value chain. Nevertheless, the identification of these determinants alone is not enough to inspire appropriate policy interventions. Hence, analyzing the relative influence of variables helps for priority-based policy interventions. In this section, the double hurdle model results are presented to comprehend the relationships of variables.

3.11. Specification tests

Prior to operating the model, all explanatory variables were checked for the assumptions of regression analysis. Thus, it is vital to test the existence of multicollinearity of the data among the variables that determine the farm household’s participation in the apple and mango value chain. The data was checked for multicollinearity problems by employing the variance inflation factor (VIF) and correlation matrix. The estat vif command displayed an average result of 1.32 and 1.55 in apple and mango data, respectively. The mean VIF results for both apple and mango commodities were less than the critical value of ten (10) indicates that there is no multicollinearity problem among explanatory variables. Gujarati and Porter (Citation1999) recommend that variables with high VIF value (10) should be excluded since it is an indication of problems of multicollinearity.

3.12. Factors affecting participation decision and intensity of participation

Table presents the probit model results on the decision to participate in apple and mango value chains and truncated regression results on the intensity of participation. The probit model results confirm that out of thirty (13) covariates nine and seven were found to significantly influenced the probability of apple and mango household’s participation decision, respectively. Likewise, truncated regression results indicate that four and nine covariates significantly affect the intensity of participation among apple and mango households, respectively.

Table 5. Results of double hurdle model of determinants influencing participation decision and intensity of participation

The age of the household head exhibits a significant and positive relationship (p < 0.05) with respondents’ intensity of participation in the mango value chain but insignificant relationships with the intensity of apple value chain participation. The positive effect of age on the intensity of mango value chain reflects that as farmers get older, they could acquire skills and hence produce more and develop skills to participate in the value chain activities. An increase in the age of respondents by a year increases the intensity of participating in the mango value chain by 12%. Our result contrasted the findings held by Azam et al. (Citation2012), Abafita et al. (Citation2016), and Tafesse et al. (Citation2020), who found the negative relationship with farmers’ participation. On the other hand, the age-square of the respondent had a negative (non-linear) relationship on both apple and mango value chain participation decisions. The variable had also a significant relationship with the intensity of farmers participating in the mango value chain but insignificant relationships with the intensity of apple. The Age-square of the respondent had a negative (non-linear) relationship on the mango value chain level of participation. On the other hand, the negative effect of age-square indicates that, as the farmer gets older, the probability of participation decision and intensity of participation declines. A similar finding was reported by Somano (Citation2008).

The educational level of the household head was found to be a positive and significant factor in explaining both apple and mango farmers’ participation decisions and intensity of participation in the value chain. The variable “illiterate” was left out of the regression model to avoid the variable trap and used as a reference. Our study finds that a household with the education level of high school and above increases the probability of apple and mango value chain participation decisions by 1.43% and 3.35%, respectively, compared to the reference variable. Randela et al. (Citation2008) revealed that highly educated farmers were more likely to participate in the agri-food market due to their better production, marketing, and managerial skills. However, our finding is contrasted with Ouma et al. (Citation2010), who reported that banana farmers’ education level negatively affects their market participation in Burundi and Rwanda.

Household size had a significant and negative relationship with the probability of participation decisions in both apple and mango value chains. The negative coefficient of household size with the probability of participation in both apple and mango value chains, perhaps because larger family size had more dependents and increased consumption. The more the household consumption requirement, the less a farmer could decide to participate in the fruits value chain. However, the literature by Makhura et al. (Citation2001) revealed that even though large family size reduces the probability of participating in the market economy, it also signifying access to active labor for production and marketing activities. Our result contrasted the findings held by Kassa et al. (Citation2017), whereas a similar finding was reported by Girmalem et al. (Citation2019) and Megerssa et al. (Citation2020).

3.12.1. Plot size

Unlike apple value chain participation, plot size had a positive significant influence on the decision to participate in the mango value chain. In an agrarian society like Ethiopia, the land is the most essential means because of its role in any economic activity including farming. A study by Tufa et al. (Citation2014) and Tarekegn et al. (Citation2020) supported our finding that the plot size allocated for fruit crops positively and significantly influenced growers’ participation decisions in production and marketing. This result also supports the literature (Tesfay, Citation2008) that landholding size has important implications for the production of market-oriented crops like apple and mango. Also, Jaleta et al. (Citation2009) showed that cultivable land size to be an important factor in persuading farmers to supply their produce to the market.

Farming experience is another crucial factor in influencing growers’ production and marketing capabilities. The variable is highly significant and positively associated with both apple and mango growers’ probability to participate in value chains. In addition, it had a positive significant effect on mango farmers’ intensity of value chain participation, but an insignificant effect on apple farmers’ intensity of value chain participation. Other things being constant, the coefficients showed that as experience increases by a year, the probability of participating in value chain increases by 20% and 7% for apple and mango households, respectively. Our finding is theoretically acceptable as more experienced growers may have more production and marketing linkage and information.

The incidence of disease and insect pests had a statistically negative relationship and highly significant with both apple and mango growers’ participation decisions. The negative relationship with both apple and mango growers’ participation decision reaffirms how the variable becoming a major challenge influencing the grower’s participation. This result is in agreement with the study results by Nigussie et al. (Citation2019). However, in terms of relationships, their finding was unexpectedly a positive relationship with apple growers. A study by Dessalegn et al. (Citation2014) revealed that powdery mildew and anthracnose are the two most common fungal diseases of mango trees in one of our study area (Bahir Dar Zuria district). Similarly, scale borer, aphid, and caterpillar are the major insect pests affecting apple tree production. Diseases such as twig blight, apple scab, and powdery mildew are the major ones that contributed to the reduction of apple production and productivity (Atreya & Kafle, Citation2016).

Perceived wild animals as a serious problem had a negative significant effect on growers’ probability of participation in the mango value chain, but insignificant relationship with apple farmers’ value chain participation decision. This variable decreases the probability of value chain participation for mango by 2.108%, indicates how much this variable deters mango farmers from participation in the value chain. In the areas, mango farmers reported that the major wild animals damaged their fruits produce includes apes, baboons, and birds.

Distance to the nearest market had a statistically negative influence on sales volume for mango, but an insignificant effect for apple. The variable was specified in walking time on foot in minutes from respondents’ residence to the market. The negative effect of distance to the nearest market implies that farmers closer to the market have access to better market facilities and buyers. As the distance to the nearest market from farmers’ residences increases by a minute, mango produce supplied for sale is decreased by 0.0096 quintals. Besides, the shorter the market distance would be the reduced transportation costs and reduced walking time. Previous finding by Tufa et al. (Citation2014) and Habtamu (Citation2015) supports this result.

The frequency of extension contact had a positive and significant effect on the decision to participate in the apple value chain, but an insignificant effect on mango value chain participation. The variable had a positive and significant effect (p < 0.01) on the intensity of participation in both the apple and mango value chain. The positive significant effect of frequency of extension contact is theoretically acceptable, implies that frequent visit by extension agents’ makes growers aware of current information regarding new agricultural practices that might enhance production and marketing and therefore increase their decision and intensity of participation in the value chain. Our finding is similar to that of Tufa et al. (Citation2014), Tarekegn et al. (Citation2020), and Abrha et al. (Citation2020). This result is quite relevant as extension service plays an important role in the production and marketing of cash crops like apple and mango.

3.12.2. Ownership of transportation asset

Our findings further underscore that ownership of transportation assets (e.g., equines and cart) had a positive and significant effect (p < 0.01) on sales volume for mango, but an insignificant effect on apple. Ownership of transportation assets plays an important role in reducing transportation costs. It also offers more chances of finding marketing alternatives and encourages participating in the value chain. The positive effect of our finding is consistent with the study of Regasa et al. (Citation2019) and Kassaw et al. (Citation2019).

3.12.3. Membership in local cooperatives

The coefficient of membership in local cooperatives is statistically significant and positively related to value chain participation for both apple and mango households. The positive effect of membership in local cooperatives on the decision to and intensity of participation in both apple and mango value chains suggests that farmers’ cooperatives and associations can be a good information exchange platform enabling growers to share experiences to increase production and marketing decisions. This result supports the literature (Asfaw et al., Citation1997) that membership in cooperatives has important implications for producers to be exposed to information and aware of improved agricultural practices.

Access to price information had a positive and significant effect on the decision to participate in apple, but an insignificant effect for mango. Moreover, Access to price information was another key variable that positively influences the decision to participate in the apple value chain. This result is also quite relevant as information plays an important role in the marketing of cash crops like apple and mango. Our result is in line with economic theory by Alene et al. (Citation2008), who revealed the presence of a positive association between price and sales proportion and approve price to be an inducement to supply for sale. Our result is also consistent with the findings of (Mbapila et al., Citation2019).

3.12.4. Ownership of mobile phones

The coefficient of ownership of mobile phones is statistically significant and positively related to the intensity of participation for both apple and mango growers. The positive coefficient of ownership of mobile phone suggests that mobile phone is important information communication equipment helps growers aware of up-to-date information regarding production and marketing activities and therefore increase their motivation to participate in the value chain. This result supports the literature by (Hoang, Citation2020).

Total livestock size measured in tropical livestock unit (TLU) had a statistically negative influence on the decision to participate for apple, but an insignificant effect for mango. Finally, though not significant, the household labor force in man equivalent had a positive relationship with both apple and mango growers’ intensity of participation in the value chain. In rural Ethiopia, livestock holding might indicate a specialization in livestock farming, in which involvement in fruits production like mango may be less likely. However, the reason for a negative relationship with apple growers might be ownership of such assets diverts the household into an alternative source of earnings. Our result is consistent with the findings of Jaleta et al. (Citation2009) but contradicts the findings of Temesgen and Hiwot (Citation2017), who reported that total livestock holding improves small-scales’ decision to participate in cash crops like apple and mango.

4. Conclusions and policy implications

4.1. Conclusions

Using household-level data, our study emphasized examining the determinants of small-scale farmers’ participation decision and intensity of participation in apple and mango value chains in the Upper Blue Nile Basin, Ethiopia. Employing combinations of descriptive statistics and the double hurdle model, the study has tried to look into the socio-economic, institutional, demographic, and other non-price constraints. The result shows that the probability of a farmer being participating in the apple value chain increases with household head education level, extension contacts, fruit farming experience, and membership in local cooperatives, while decreases with household size and incidence of disease and insect pests. Moreover, mango plot size and membership in local cooperatives increase the probability of participation decisions in the mango value chain. Furthermore, households’ intensity of participation in the apple value chain increases with education level and extension contacts, whereas age squared and distance to the nearest market decrease their intensity of participation in the mango value chain. Hence, the following policy measures should get more attention from the district extension experts and regional agriculture development policymakers:

The age of farmers is a factor influencing their participation in the fruits value chain. This suggests that participation in value chain declines as the age of farmers increases. Therefore, it is important to conduct periodic experience-sharing among young and old age producers. Human capital improvement appears to be vital in small-scale farmers’ value chain participation. The role of value chain participation in more educated small-scale households suggests that offering basic education for them might improve productivity, participation in the fruits value chain, and their food security status. Regarding household size, policies, and programs incorporating family planning should get attention since having a large number of household size decreases the probability of households’ fruits value chain participation. On the other hand, the experience of small-scale producers is a factor that is positively influencing their participation. This suggests that participation in the value chain increases as the experience of farmers increases. Therefore, it is important to conduct periodic experience-sharing among experienced and inexperienced small-scale producers. Incidence of disease and insect pests is a major factor that threatens participation decision and participation intensity among mango producers. Therefore, the integration of traditional and scientific ways of preventing should be emphasized by Federal and Regional Research Centers and Agricultural Offices. The regional agricultural bureau should place emphasis on post-harvest handling to minimize the loss of both apple and mango production. The regional governments should also extend their support through access to updated market and price information, access to frequent extension contacts, rural infrastructure development (such as rural road development).

4.2. Implications for future research

The main intention of the current study was to investigate the determinants influencing small-scale farmers’ participation decision and intensity of participation in apple and mango value chains. The study was only focused on one actor (small-scale farmers) apple and mango value chains. Therefore, further investigations highlighting the determinants of fruit traders’ participation along the value chain should get attention.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to extend their deepest thanks to Addis Ababa University and Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA)-the Science and Technology Research Partnership for Sustainable Development (SATREPS), for sponsoring this study. Special thanks go to Dr. Daregot Berihun, Professor Nigussie Haregeweyn, and Dr. Derege Tsegaye. Our thanks also go to all respondents and data collectors. The authors appreciate and thank Mr. Anteneh Wubet and Mr. Niguse Tadesse, who are the SATREPS project field research assistants, for their cooperation during data collection. Finally, we would like to thank the editor and the two reviewers for their constructive comments.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Mengistie Mossie

Mengistie Mossie is a PhD fellow in Rural Development Studies, at Addis Ababa University. His research interests include: impact assessment studies of different rural development projects, rural business management/enterprise development as well as value chain development for fresh horticultural crops.

Alemseged Gerezgiher

Dr. Alemseged Gerezgiher is an Ass. Professor of Development Studies at Addis Ababa University, Ethiopia. He is also associate consultant at the Ethiopian Management Institute.

Zemen Ayalew

Dr. Zemen Ayalew is an Asso. Professor of agricultural economics at Bahir Dar University, Ethiopia. He is also component leader in the Science and Technology Research Partnership for Sustainable Development (SATREPS) project- Bahir Dar University.

Zerihun Nigussie

Dr. Zerihun Nigussie is a scientist at the Arid Land Research Center, Tottori University, Japan. His research work falls in the domain of technology adoption, issues of economics and agriculture, food security, and poverty analysis.

References

- Abafita, J., Atkinson, J., & Kim, C. (2016). Smallholder commercialization in Ethiopia: Market orientation and participation. International Food Research Journal, 23(4), 1797. http://www.ifrj.upm.edu.my/

- Abate, T. M., Mekie, T. M., & Dessie, A. B. (2019). Determinants of market outlet choices by smallholder teff farmers in Dera district, South Gondar Zone, Amhara National Regional State, Ethiopia: A multivariate probit approach. Journal of Economic Structures, 8(1), 39. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40008-019-0167-x

- Abrha, T., Emanna, B., & Gebre, G. G. (2020). Factors affecting onion market supply in Medebay Zana district, Tigray regional state, Northern Ethiopia. Cogent Food & Agriculture, 6(1), 1712144. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311932.2020.1712144

- Adepoju, A. O., Owoeye, I. T., & Adeoye, I. B. (2015). Determinants of market participation among Pineapple farmers in Aiyedaade local government area, Osun State, Nigeria. International Journal of Fruit Science, 15(4), 392–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/15538362.2015.1015763

- Alene, A. D., Manyong, V. M., Omanya, G., Mignouna, H., Bokanga, M., & Odhiambo, G. (2008). Smallholder market participation under transactions costs: Maize supply and fertilizer demand in Kenya. Food Policy, 33(4), 318–328. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2007.12.001

- Ao, X. H., Vu, T. V., Le, K. D., Jirakiattikul, S., & Techato, K. (2019). An analysis of the smallholder farmers’ cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz) value chain through a gender perspective: The case of Dak Lak province, Vietnam. Cogent Economics & Finance, 7(1), 1645632. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2019.1645632

- Asfaw, N., Gunjal, K., Mwangi, W., & Seboka, B. (1997). Factors affecting the adoption of maize production technologies in Bako Area, Ethiopia. Ethiopian Journal of Agricultural Economics, 1(2), 52–73.

- ATA. (2017). Ethiopia’s Agricultural Extension Strategy (Draft): Vision, Systemic Bottlenecks and Priority Interventions. Agricultural Transformation Agency.

- Atreya, P., & Kafle, A. (2016). Production practice, market and value chain study of organic apple of Jumla. Journal of Agriculture and Environment, 17, 11–23. https://doi.org/10.3126/aej.v17i0.19855

- Azam, M. S., Gaiha, R., & Imai, K. (2012). Agricultural supply response and smallholders market participation: The case of Cambodia. School of Social Sciences, University of Manchester.

- Belay, C. S. (2018). The effects of crop market participation in improving food security among smallholder crop producer farmers: The case of Central Ethiopia, Adaa Woreda. Journal of Development and Agricultural Economics, 10(9), 298–316. https://doi.org/10.5897/JDAE2018.0953

- Beshir, H., Emana, B., Kassa, B., & Haji, J. (2012). Determinants of chemical fertilizer technology adoption in North eastern highlands of Ethiopia: The double hurdle approach. Journal of Research in Economics and International Finance, 1(2), 39–49. http://www.interesjournals.org/JREIF

- Biggeri, M., Burchi, F., Ciani, F., & Herrmann, R. (2018). Linking small-scale farmers to the durum wheat value chain in Ethiopia: Assessing the effects on production and wellbeing. Food Policy, 79, 77–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2018.06.001

- Blandon, J., Henson, S., & Cranfield, J. (2009). Small‐scale farmer participation in new agri‐food supply chains: Case of the supermarket supply chain for fruit and vegetables in Honduras. Journal of International Development: The Journal of the Development Studies Association, 21(7), 971–984. https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.1490

- Burke, W. J. (2009). Fitting and interpreting Cragg’s tobit alternative using Stata. The Stata Journal, 9(4), 584–592. https://doi.org/10.1177/1536867X0900900405

- Chala, W. (2010). Value chain analysis of fairtrade coffee: The case of Bedeno Woreda primary coffee cooperatives, East Hararghe Zone, Ethiopia [MSc Thesis]. Haramaya University.

- Chang, K., Brattlof, M., & Ghukasyan, S. (2014). Smallholder participation in the tropical superfruits value chain: Ensuring equitable share of the success to enhance their livelihood. Food and Agriculture Organisation.

- Cragg, J. G. (1971). Some statistical models for limited dependent variables with application to the demand for durable goods. Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society, 39(5), 829–844. https://doi.org/10.2307/1909582

- CSA. (2019). Agricultural sample survey: Area and production of major crops. Central Statistical Agency of Ethiopia.

- Dapaah, H., Asafu-Agyei, J., Ennin, S., & Yamoah, C. (2003). Yield stability of cassava, maize, soya bean and cowpea intercrops. The Journal of Agricultural Science, 140(1), 73. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021859602002770

- De Janvry, A., Dustan, A., & Sadoulet, E. (2010). Recent advances in impact analysis methods for ex-post impact assessments of agricultural technology: Options for the CGIAR. Unpublished working paper, University of California-Berkeley.

- De Janvry, A., & Sadoulet, E. (2020). Using agriculture for development: Supply-and demand-side approaches. World Development, 133, 105003. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105003

- Dessalegn, Y., Assefa, H., Derso, T., & Tefera, M. (2014). Mango production knowledge and technological gaps of smallholder farmers in Amhara Region, Ethiopia. American Scientific Research Journal for Engineering, Technology, and Sciences (ASRJETS), 10(1), 28–39. http://asrjetsjournal.org/

- EIAR A. (2013). Seed Potato Tuber Production and Dissemination Experiences, Challenges and Prospects. In Proceedings of the National Workshop on Seed Potato Tuber Production and Dissemination, 12–14 March 2012. Ethiopian Institute of Agricultural Research.

- Gebremedhn, M. B., Tessema, W., Gebre, G. G., Mawcha, K. T., & Assefa, M. K. (2019). Value chain analysis of sesame (Sesamum indicum L.) in Humera district, Tigray, Ethiopia. Cogent Food & Agriculture, 5(1), 1705741. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311932.2019.1705741

- Getahun, W., Tesfaye, A., Mamo, T., & Ferede, S. (2018). Apple value chain analysis in the Central Highlands of Ethiopia. International Journal of Agriculture Innovations and Research, 7(1), 2319–1473. https://ijair.org/

- Girmalem, N., Negussie, S., & Degye, G. (2019). Determinants of mangoes and red peppers market supply in Ahferom and Kola-Tembien Districts of Tigray Region. Socio Economic Challenges, 3(4), 39-51.

- Girmay, G., Menza, M., Mada, M., & Abebe, T. (2014). Empirical study on apple production, marketing and its contribution to household income in Chencha district of southern Ethiopia. Scholarly Journal of Agricultural Science, 4(3), 166–175. http://www.scholarly-journals.com/SJAS

- Gujarati, D. N., & Porter, D. C. (1999). Essentials of econometrics. Irwin/McGraw-Hill.

- Habtamu, G. (2015). Analysis of Potato Value Chain in Hadiya Zone of Ethiopia [MSc Thesis]. Haramaya University.

- Habtewold, A. B., Challa, T. M., & Latha, D. A. (2017). Determinants of smallholder farmers in teff market supply in Ambo district, West Shoa Zone of Oromia, Ethiopia. International Journal of Advanced Research in Management and Social Sciences, 6(2), 133–140. www.garph.co.uk. IJARMSS /133

- Heckman, J. J. (1979). Sample selection bias as a specification error. Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society, 47(1), 153–161. https://doi.org/10.2307/1912352

- Hoang, H. G. (2020). Determinants of the adoption of mobile phones for fruit marketing by Vietnamese farmers. World Development Perspectives, 17(C), 100178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wdp.2020.100178

- Hussein, K., & Suttie, D. (2016). IFAD Research Series 5-Rural-urban linkages and food systems in sub-Saharan Africa: The rural dimension. IFAD Research series.

- Hussen, S., & Yimer, Z. (2013). Assessment of production potentials and constraints of mango (Mangifera indica) at Bati, Oromia zone, Ethiopia. International Journal of Sciences: Basic and Applied Research, 11(1), 1–9. http://gssrr.org/index.php?journal=JournalOfBasicAndApplied

- Jaji, K., Man, N., & Nawi, N. M. (2018). Factors affecting pineapple market supply in Johor, Malaysia. International Food Research Journal, 25(1), 366-375. http://www.ifrj.upm.edu.my/

- Jaleta, M., Gebremedhin, B., & Hoekstra, D. (2009). Smallholder commercialization: Processes, determinants and impact. ILRI Discussion Paper 18. Nairobi(Kenya).

- Kadigi, M. L. (2013). Factors influencing choice of milk outlets among smallholder dairy farmers in Iringa municipality and Tanga city. https://www.semanticscholar.org/

- Kahenge, Z., Kavoi, M., & Nhamo, N. (2020). Determinants of non-transgenic soybean adoption among smallhoder farmers in Zambia. Cogent Food & Agriculture, 6(1), 1797260. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311932.2020.1797260

- Kassa, G., Yigezu, E., & Alemayehu, D. (2017). Market chain analysis of highvalue fruits in Bench Maji Zone, Southwest Ethiopia. International Journal of Marketing Studies, 9(3), 124–135. https://doi.org/10.5539/ijms.v9n3p124

- Kassaw, H. M., Birhane, Z., & Alemayehu, G. (2019). Determinants of market outlet choice decision of tomato producers in Fogera woreda, South Gonder zone, Ethiopia. Cogent Food & Agriculture, 5, 1709394. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311932.2019.1709394

- Kilelu, C., Klerkx, L., Omore, A., Baltenweck, I., Leeuwis, C., & Githinji, J. (2017). Value chain upgrading and the inclusion of smallholders in markets: Reflections on contributions of multi-stakeholder processes in dairy development in Tanzania. The European Journal of Development Research, 29(5), 1102–1121. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41287-016-0074-z

- Komarek, A. (2010). The determinants of banana market commercialisation in Western Uganda. African Journal of Agricultural Research, 5(9), 775–784. https://doi.org/10.5897/AJAR.9000687

- Kyaw, N. N., Ahn, S., & Lee, S. H. (2018). Analysis of the factors influencing market participation among smallholder rice farmers in magway region, central dry zone of Myanmar. Sustainability, 10(12), 4441. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10124441

- Lowitt, K., Hickey, G. M., Ganpat, W., & Phillip, L. (2015). Linking communities of practice with value chain development in smallholder farming systems. World Development, 74, 363–373. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.05.014

- Makhura, M., Kirsten, J., & Delgado, C. (2001). Transaction costs and smallholder participation in the maize market in the Northern Province of South Africa. Proceedings of the Seventh Eastern and Southern Africa Regional Conference, 11-15 February, Pretoria. 2001.

- Mbapila, S. J., Lazaro, E. A., & Karantininis, K. (2019). Institutions, production and transaction costs in the value chain of organic tomatoes and sweet peppers in tourist hotels, Unguja and Arusha. Cogent Food & Agriculture, 5(1), 1631581. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311932.2019.1631581

- McFadden, D. (1974). The measurement of urban travel demand. Journal of Public Economics, 3(4), 303–328. https://doi.org/10.1016/0047-2727(74)90003-6

- Megerssa, G. R., Negash, R., Bekele, A. E., & Nemera, D. B. (2020). Smallholder market participation and its associated factors: Evidence from Ethiopian vegetable producers. Cogent Food & Agriculture, 6(1), 1783173. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311932.2020.1783173

- Mengesha, S., Abate, D., Adamu, C., Zewde, A., & Addis, Y. (2019). Value chain analysis of fruits: The case of mango and avocado producing smallholder farmers in Gurage Zone, Ethiopia. Journal of Development and Agricultural Economics, 11(5), 102–109. https://doi.org/10.5897/JDAE2018.1038

- MoA. (2014). Growth and Transformation Plan I (GTP-I). Draft Document. Ministry of Agriculture.

- Mugenda, O. M., & Mugenda, A. G. (2003). Quantitative and qualitative approaches. Acts Press.

- Musah, A. B. (2013). Market participation of smallholder farmers in the Upper West Region of Ghana. University of Ghana.

- Ngenoh, E., Kurgat, B. K., Bett, H. K., Kebede, S. W., & Bokelmann, W. (2019). Determinants of the competitiveness of smallholder African indigenous vegetable farmers in high-value agro-food chains in Kenya: A multivariate probit regression analysis. Agricultural and Food Economics, 7(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40100-019-0122-z

- Nigussie, Z., Fisseha, G., Alemayehu, G., & Abele, S. (2019). Smallholders’ apple-based agroforestry systems in the north-western highlands of Ethiopia. Agroforestry Systems, 93, 1045–1056.

- Nigussie, Z., Tsunekawa, A., Haregeweyn, N., Adgo, E., Nohmi, M., Tsubo, M., Aklog, D., Meshesha, D. T., & Abele, S. (2017). Farmers‘ perception about soil erosion in Ethiopia. Land Degradation & Development, 28(2), 401–411. https://doi.org/10.1002/ldr.2647

- Norris, P. E., & Batie, S. S. (1987). Virginia farmers‘ soil conservation decisions: An application of tobit analysis. Journal of Agricultural and Applied Economics, 19(1), 79–90. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0081305200017404

- Ouma, E., Jagwe, J., Obare, G. A., & Abele, S. (2010). Determinants of smallholder farmers‘ participation in banana markets in Central Africa: The role of transaction costs. Agricultural Economics, 41(2), 111–122. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-0862.2009.00429.x

- Punjabi, M. (2007). Emerging environment for agribusiness and agro-industry development in India. Food and Agricultural Organisation of the United Nations.

- Randela, R., Alemu, Z. G., & Groenewald, J. A. (2008). Factors enhancing market participation by small-scale cotton farmers. Agrekon, 47(4), 451–469. https://doi.org/10.1080/03031853.2008.9523810

- Reardon, T. (2015). The hidden middle: The quiet revolution in the midstream of agrifood value chains in developing countries. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 31(1), 45–63. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxrep/grv011

- Regasa, G., Negash, R., Eneyew, A., & Bane, D. (2019). Determinants of smallholder fruit commercialization: Evidence from Southwest Ethiopia. Review of Agricultural and Applied Economics (RAAE), 22(2), 96–105. https://doi.org/10.15414/raae.2019.22.02.96-105

- Sharp, K., Ludi, E., & Gebreselassie, S. (2007). Commercialisation Of Farming In Ethiopia: Which Pathways? Ethiopian Journal of Economics, 16, 39–54.

- Sigei, G., Bett, H., & Kibet, L. (2014). Determinants of market participation among small-scale pineapple farmers in Kericho County, Kenya.

- Slamet, A. S., Nakayasu, A., & Ichikawa, M. (2017). Small-scale vegetable farmers’ participation in modern retail market channels in Indonesia: The determinants of and effects on their income. Agriculture, 7(2), 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture7020011

- Somano, W. (2008). Dairy marketing chains analysis: The case of Shashemane, Hawassa and Dale District’s milk shed, Southern Ethiopia. Haramaya University.

- Tadesse, B., & Temesgen, A. (2019). Value chain analysis of banana in Mizan Aman Town of Benchi Maji Zone, Southwest Ethiopia. International Journal of Horticulture, Agriculture and Food Science, 3(1). https://doi.org/10.22161/ijhaf.3.1.2

- Tafesse, A., Megerssa, G. R., & Gebeyehu, B. (2020). Determinants of agricultural commercialization in Offa District, Ethiopia. Cogent Food & Agriculture, 6(1), 1816253. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311932.2020.1816253

- Tamirat, G., & Muluken, P. (2018). Analysis of apple fruit value chain in Southern Ethiopia; the Case of Chencha District.

- Tarekegn, K., Asado, A., Gafaro, T., & Shitaye, Y. (2020). Value chain analysis of banana in Bench Maji and Sheka Zones of Southern Ethiopia. Cogent Food & Agriculture, 6(1), 1785103. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311932.2020.1785103

- Tarekegn, K., Haji, J., & Tegegne, B. (2017). Determinants of honey producer market outlet choice in Chena District, southern Ethiopia: A multivariate probit regression analysis. Agricultural and Food Economics, 5(1), 20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40100-017-0090-0

- Temesgen, Z., & Hiwot, A. (2017). Determinants of smallholder farmers’ participation in certified coffee value chain:Evidence from members of coffee cooperatives in Dale District, Sidamo, Southern Ethiopia.

- Tesfay, A. (2008). Determinants of Adoption and Intensity of Adoption of Vegetable Cultivation in the Irrigated Fields: The Case of Laelaymychew District, Central Tigray [M. Sc. Thesis]. Haramaya University.

- Teshager Abeje, M., Tsunekawa, A., Adgo, E., Haregeweyn, N., Nigussie, Z., Ayalew, Z., Elias, A., Molla, D., & Berihun, D. (2019). Exploring drivers of livelihood diversification and its effect on adoption of sustainable land management practices in the Upper Blue Nile Basin, Ethiopia. Sustainability, 11(10), 2991. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11102991

- Tschirley, D., Reardon, T., Dolislager, M., & Snyder, J. (2015). The rise of a middle class in East and Southern Africa: Implications for food system transformation. Journal of International Development, 27(5), 628–646. https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.3107

- Tufa, A., Bekele, A., & Zemedu, L. (2014). Determinants of smallholder commercialization of horticultural crops in Gemechis District, West Hararghe Zone, Ethiopia. African Journal of Agricultural Research, 9(3), 310–319. https://doi.org/10.5897/AJAR2013.6935

- Warsanga, W. B., & Evans, E. A. (2018). Welfare impact of wheat farmers participation in the value chain in Tanzania. Modern Economy, 9(4), 853. https://doi.org/10.4236/me.2018.94055

- Wiggins, S. (2014). African agricultural development: Lessons and challenges. Journal of Agricultural Economics, 65, 529–556.

- Wooldridge, J. M. (2010). Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data. MIT press.

- Worako, T. K. (2015). Transactions costs and spatial integration of vegetable and fruit market in Ethiopia. Ethiopian Journal of Economics, 24, 89–130.

- Yami, M., Tesfaye, T., & Bekele, A. (2013). Determinants of farmers’ participation decision on local seed multiplication in Amhara region, Ethiopia: A double hurdle approach. International Journal of Science and Research, 2, 424–425.