?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

The adoption and implementation of sustainable management practices in the cocoa sector remain crucial in the research and policy agenda in Sub-Saharan Africa. The study aimed to investigating the effect of farmers’ management practices on the safety and quality standard of cocoa produced in the South West Region of Cameroon. Information for the analysis was obtained from 201 farmers using questionnaires and a multi-stage random sampling procedure. Based on the Theory of Planned Behavior and a cacao beans quality equation, the study was achieved empirically by a two-stage structural equation modeling method using the maximum likelihood estimation technique of SmartPLS version 2. The findings revealed that the adoption and implementation of Good Agricultural Practices and Good Post Harvest Management Practices positively and significantly affect cocoa beans quality. Hence, changing farmers’ behavior and perception toward sustainable management practices is critical to boosting the production of safe and quality cocoa beans. Besides, given that certified farmers receive premiums, it does make a difference in the overall return farmers receive from their cocoa proceeds. The paid premiums lead to an overall marginal income increase. Consequently, this affirms that sustainable management practices have increased a considerable number of farmers’ efficiency and led to more certified cocoa bean production. Hence policies should be geared towards incorporating sustainable, environmentally friendly management practices into agricultural development programs that will continuously improve farmers’ knowledge of safety and quality standards of cocoa production since it tends to increase farmers’ overall marginal income.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Cocoa is predominantly grown by many small-scale farmers in Cameroon and an essential source of revenue for the livelihood of many households in cocoa producing communities. The increasing demand for high-quality premium beans products poses a threat to the cocoa sector of Cameroon. As such, this has led to the introduction of certification schemes. This study assesses the effect of farmers’ behavior in the adoption of Good Agricultural Practices and Good Post Harvest Management Practices as a very vital step to ensure the production of quality cocoa. Based on the findings, the adoption and implementation of Good Agricultural Practices and Good Post Harvest Management Practices have a positive and significant relationship with cocoa beans quality. The results suggest that one possible solution to help farmers keep producing certified cocoa is by reaching out with a premium to all farmers who produce certified cocoa and implement a flexible premium policy.

1. Introduction

Developing countries have been more concerned about the demand for high-quality premium beans products (Pacific Agribusiness Research & Development Initiative [PARDI], Citation2012). Since 2003, more attention has been given to food safety and quality standards by consumers and governments in developing countries with strict regulations and legislation on the safety and quality of food produced, processed, and its economic sustainability to protect consumers’ health (International Cocoa Organization [ICCO], Citation2008a; World Health Organization [WHO], Citation2003), due to the increasing prevalence of chemical residues, bad flavor, smoke contamination, broken, germinated, mold, placenta and foreign materials in beans that consistently affects its quality (Standard Trade Development Facility [STDF], Citation2014). According to the (ICCO Citation2008b) specific standards are required to be followed to improve the quality of cocoa beans. It was argued that cocoa beans of merchant quality must be fermented, thoroughly dry, free from smoky beans, free from abnormal or foreign odor and free from any evidence of adulteration; and reasonably uniform in size, reasonably free from broken beans, fragments and pieces of shell, and be virtually free from foreign matter.

Most developing countries are taking part in schemes that aim to generating more foreign exchange earnings and attain food security, thereby sustaining its sub-sectors, such as Cameroons’ cocoa sub-sector (David, Citation2013). With continuous liberalization of the agricultural sector, the guarantee of quality and safety standards in food is crucial nowadays, and food handlers are responsible for production, processing, handling and distribution (Will & Guenther, Citation2007). Consumers are increasingly anxious about the quality and standard of food across the entire agri-food chain from inputs, production, processing, and distribution (Gereffi & Lee, Citation2009). Therefore, this has led to the introduction of certification schemes. Cameroons’ cocoa certification started in 2014 by Telcar Cocoa Limited (Mubeteneh, Citation2007). Three leading organizations certify farmers; Organic, Fairtrade, Rainforest Alliance (UTZ and Rainforest Alliance, which have merged, January 2018; Fountain & Hütz-Adams, Citation2018). Although there is a difference in the certification philosophy of the different certification organizations, they convey the idea of ameliorating farm households’ livelihoods and the sustainability of the cocoa value chain (ICCO, Citation2011). In 2014, globally, 1.7 million metric tons of certified cocoa was produced on 2 million hectares of land by the four leading certification organizations (Lernoud et al., Citation2015).

More than 5 million smallholder farmers are engaged in cocoa production worldwide, providing a living for about 40 to 50 million people (Hütz-Adams et al., Citation2016). Cocoa is a crucial perennial cash crop that is predominantly grown by many small-scale farmers in West Africa and an essential source of revenue for the livelihood of many households in cocoa producing communities (Kimengsi & Azibo, Citation2015). Cameroon is ranked as the third-largest producer of cocoa in Africa with a production capacity of 380,00 tonnes in 2017 against 882,175 tonnes for Ghana and 2.01 million tonnes for Côte d’Ivoire (ICCO, Citation2017). In 2018, cocoa beans accounted for 492 USD million and were the second top export in Cameroon after crude petroleum (Observatory Economic Complexity [OEC], Citation2018). Cocoa contributed 22.4% of the export share of the country’s overall exports in 2017 (Klynveld Peat Marwick Goerdeler [KPMG], Citation2017). Cocoa plantations have increased significantly with a planting area of 500 000 hectares, with about 400,000 to 600, 000 households involved in cocoa production and about 95% of their farms on average ranging from 2.5 to 5 hectares (Hütz-Adams et al., Citation2016). Furthermore, cocoa is cultivated in 7 out of 10 regions in Cameroon, and about 90% of household income in cocoa producing communities is generated from cocoa production activities (Mukete et al., Citation2018).

Generally, two types of cocoa beans are produced in Cameroon; ordinary and certified cocoa. The ordinary cocoa bean is purple in color, has bad flavor and aroma, heterogeneous in size, has foreign materials and infested by disease (Benjamin et al., Citation2011). Certified beans have a humidity content of ≤7.5%, minimum infection from pest and disease, fewer defects in grains, minimal or no moldiness, homogeneous grains, and less foreign matter (Ansah et al., Citation2018). Cameroon cocoa farmgate prices rose sharply at the 2020 cocoa production season as bean quality also improved (Business in Cameroon [BIC], Citation2020). However, in Cameroon, the cocoa farming sector is characterized by low investments in cocoa plantations, lack of sustainability in the cocoa value chain, and a vicious circle of persistently low yields and income (Hütz-Adams et al., Citation2016). Thus, this implies that research aimed at improving the quality of cocoa beans produced in Cameroon tends to improve farmers’ livelihood and needs to be encouraged.

Consumers’ perception of food has been severely affected by residues from pesticides and toxins such as cadmium (Buzby, Citation2003); hence there is a gradual shift from traditional production methods to sustainable production of cocoa beans. In 2013, the first African country, Cameroon, witnessed 2,000 tons of cocoa beans rejected by the European Union, who failed to certify their bean grains. The reason was that more than two micrograms of cadmium per kilogram were detected in bean grains, which resulted partly from chemical fertilizers. Recently, there has also been contamination with Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon, mainly because cocoa beans are dried on tarred roads (Bitumen) and poorly smoke traditionally using wood ovens. Consequently, this has resulted in high levels of chemicals in the bean grain, and poor bean grain quality, characterized by a strong smell of smoke harmful to human health (Moki Kindzeka, Citation2013; Viban, Citation2018a). Operators in the cocoa sector continue to seek solutions to improve cocoa beans’ quality. Despite all the efforts to step up bean quality, quality remains almost the same as before (BIC, Citation2018).

Most empirical studies (Akmel et al., Citation2016; Benjamin et al., Citation2011; Folayan, Citation2010; Levai et al., Citation2015; Niemenaka et al., Citation2014; Quarmine et al., Citation2012) have focused on the different management practices and constraints that limit farmers from producing quality cocoa. They found out that farmers’ management practices had a positive and significant relationship with cacao beans quality. Baffoe-Asare et al. (Citation2013) found out that farmers’ adoption of cocoa innovations is linked to their production capacity and farms. By contrast, this study jointly assesses the effect of farmers’ behavior in adopting Good Agricultural Practices (GAP) and Good Post Harvest Management Practices (GPHMP) simultaneously as a vital step to ensure the production of quality cocoa because the quality process is a pre-requisite one. Once an activity is not well carried out at the preceding stages of production, it becomes difficult to correct at successive stages in the production chain and affect the final quality of the bean available for sale.

Although many studies have been carried out on cocoa beans quality and safety standards in West Africa and other parts of the World, minimal research work has been done in Cameroon. Most studies in the South West region have applied the deductive approach to research, which is not very efficient in meeting up with cocoa beans quality and safety standards and has been based primarily on numerical evidence. This study will use an integrative approach to examine if a selection of factors is associated with the farmers’ behavior for their different management practices. This study will formulate a structural model (SM) that shows the relationship between the farmers’ management practices and their cocoa beans’ quality. This model will show the present state of beans in the South West region of Cameroon, and the recommendations of the study will suggest what can be done to help farmers improve their quality of cocoa beans. The model will be relevant to all the cocoa sector stakeholders who have as their objectives to alleviate poverty and ensure food security. The findings will serve as a policy instrument to eliminate bad farm management practices and encourage result-oriented behavioral changes.

This study is based on the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) (Ajzen, Citation1991) as a critical theoretical framework to study cocoa farmers’ general attitude in the adoption and implementation of sustainable farm management practices. The theory postulate that a persons’ intention is an explanatory factor of their actual behavior. Furthermore, a persons’ intent is built from their perceived behavioral control (PBC), attitude and subjective norms. As such, the intention is the cognitive product of careful consideration of motivational, social and non-motivational factors that affect behavior. An individual perceived social pressure to carry out a particular behavior is viewed as his subjective norm. The extent to which an individual has an unfavorable or a favorable evaluation of a behavior is referred to as his attitude. Lastly, the extent to which a person can perform a behavior is regarded as his PBC (Ajzen, Citation1991). Higher intentionality shows a higher willingness to carry out behavior over which a person has actual control. Based on this reason, this modified theory is widely used in research.

The applicability of the TPB theory in different research contexts gives it strength over other psycho-social category theories (Ajzen, Citation2011: Meijer et al., Citation2015). Its extensive usage in many studies has confirmed its importance and validity (Armitage & Conner, Citation2001; Godin & Kok, Citation1996). This study thus focuses on the TPB with a keen interest in the PBC. It also incorporates knowledge from other psycho-social theories such as the Theory of Reason of Action, which also explains that behavior can be captured by the intension of the individual to perform the behavior (I. F. M. Ajzen, Citation1980). However, TPB’s main criticism is its prime prominence on psycho-social factors (Ajzen, Citation1985).

The study adopts the framework of the cacao beans quality equation proposed by Lima et al. (Citation2011) to set up the research hypothesis. Figure depicts the different management practices that farmers implement. The GAP that influences cocoa beans quality and safety standards include; planting improved plant varieties, proper soil management, spraying, frequent harvesting, Phytosanitory harvesting, pruning, adequate field sanitation and climate variability. The postharvest management process starts with pod breaking, followed by fermenting, drying and sorting (Lima et al., Citation2011).

Figure 1. Stages that Contribute to the Quality and Safety Standards of Commercial Cocoa

Mindful of the research problem, the following hypothesis was raised:

H01: Farmers’ behavior in practicing GAP has no positive and statistically significant effect with their GPHMP.

H02: Farmers’ behavior in carrying out GAP has no positive and statistically significant effect on the Quality and Safety Standard (QSD) of cocoa beans produced.

H03: Farmers’ behavior towards GAP and GPHMP (GAP*GPHMP) has no positive and significant effect on the QSD of cocoa beans produced.

H04: Farmers’ behavior in practicing GPHMP has no positive and statistically significant effect on the QSD of cacao beans produced.

Based on the justifications mentioned supra, the study seeks to investigate the relationship between farmers’ behaviors’ towards implementing GAP and GPHMP and its effect on the QSD of cocoa beans produced in the South West region.

2. Materials and method

2.1. Research design and selection of research sites

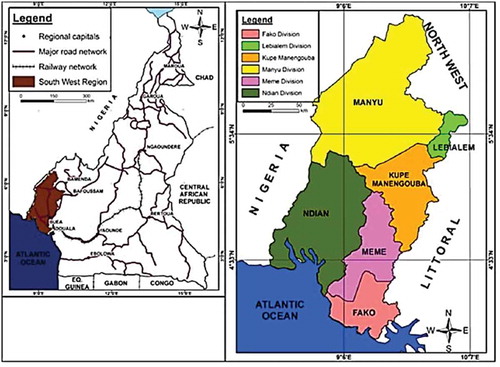

This study was conducted in the cocoa-producing areas of the South West region of Cameroon. The region is geographically located in the coastal highlands with an equatorial climatic condition characterized by forest, good volcanic soil, and a mono-modal rainfall pattern between latitude 2° 20ʹ-4°40ʹ N and 8°30ʹ-10°20ʹ E (Ministry of Environment, Protection of Nature and Sustainable Development [MINEPDED], Citation2012). It has a surface area of 25,410 km2 and a population of 1,553,320 (South West Region, Citation2019). The South West region was considered as a case study due to its dominance in cocoa production. Figure depicts a map of the South West region.

Figure 2. Map of Study Area

2.2. Sampling and data collection

A stratified multi-stage random sampling procedure was used to select the survey sites and the sample household in the South West region. From the selected region, three divisions were randomly selected from the four-leading cocoa-producing divisions. They were Manyu, Fako and Meme. In the next stage, three leading cocoa-producing sub-divisions were purposively selected from the three selected divisions. In the next stage, two leading cocoa-producing communities were purposively selected from each sub-division. The last step involves the selection of participants. Cocoa farmers were approach randomly at their farms and houses for the study. Thus, in other to ensure that the research was feasible, a sample size of 210 farm households were interviewed. Each interview consists of four main sections; socioeconomic data, demography, geography, farmers’ Good Agricultural practices (GAP), farmers’ Good Post Harvest Management Practices (GPHMP) and information on the quantity of certified and ordinary cocoa beans produced. In each of the selected farm households, the household head that makes the day-to-day decisions on-farm management activities were used as the sampling unit. At the end of the data collection period, a total of 201 valid questionnaires were received (95.7% response rate).

The leading cocoa producing region in Cameron is the South West region (50%), followed by the center (35%) and lastly the South East (15%) (Mubeteneh, Citation2007). Meme division is the largest producing area in the South West, accounting for 40% of its production. It is followed by the Manyu, Kupe Manenguba and Fako regions, which account for 25%, 14% and 11%, respectively (Tosam & Njimanted, Citation2013). The South West region has the highest production capacity in Cameroon with more than 425 kg per hectare compared to 360 kg per hectare and 200–300 kg per hectare in the Centre and South regions, respectively (Royal Tropical Institute et al., Citation2010). The primary reason for undertaking fieldwork in these particular communities was that about 90% of household income in these cocoa-producing communities is generated from cocoa production (Mukete et al., Citation2018).

The information for the analysis was obtained from cross-sectional data through a well-structured and semi-structured questionnaire, key informant interviews and personal observations. The questionnaire was designed based on existing literature, theory, pilot study, and informal group discussions with agricultural experts. The study used the framework of Sefriadi et al. (Citation2013) and Chinda and Suanmali (Citation2017) to develop the questionnaires. One community was used to carry out a pre-test survey to test the feasibility of the questionnaire. After the interview with 20 farmers, corrections were made on the questionnaires to contextualize and modify them to ensure no ambiguity in the questions asked. Some questions were left out, and new ones were added based on existing theory and literature. Subsequently, the questionnaire was used to obtain information about farmers’ behavior while carrying out their management practices to produce quality and safe cocoa beans.

2.3. Analytical framework

Based on the TPB and the cacao beans quality equation proposed by Lima et al. (Citation2011), the researcher used the Partial Least Square Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) approach to measure the inter-relationship between variables in the conceptual model. The study used the SEM framework similar to the work of Booth et al. (Citation2013), Sefriadi et al. (Citation2013), Xayavong et al. (Citation2016), Chinda and Suanmali (Citation2017), Mutyasira et al. (Citation2018), and Raza et al. (Citation2019), for model building and analysis. The reason for using multiple items as opposed to single items to construct measurements is that the measures will be more accurate (Hair et al., Citation2013) and can be used to test theoretically supported linear and additive causal models (Sarstedt, Citation2014). A set of indicators was used to measure each construct, as shown in Table . Initially, GAP was measured from farmers’ response in their perceived behavior in 6 aspects of farmers’ farm activities: changes in current agricultural practices (CarryCH), adopt good agricultural practices learned from FFS (IGAP), soil nutrient management (FSoilM), soil erosion management (Erosion), spray pest and disease (FSprayPD) and dispose-off infested pods (DisIpods). Based on a three-point (Never, some time and always) and a five-point (Never, rarely, sometimes, often, always) likert scale, farmers were asked the extent to which they perceived changes in current agricultural practices (adopt good agricultural practices, soil nutrient management, soil erosion management, spray pest and disease, and dispose-off infested pods) contributed to increasing or decreasing the quality and safety of commercial cocoa beans.

Table 1. Dimensions of the cacao beans quality and safety standards and item description

The GPHMPs construct was theoretically built from farmers’ behavior in three aspects: adopt GPHMP (IGPHMP), drying methods used by farmers (Mdry), and sorting of cocoa beans (BrokenG). A three-point and a five-point likert scale were also used to assess the extent to which farmers adopt GPHMPs, drying methods used and sorting of cocoa beans to either increase or decrease the quality of beans. Cocoa bean grain quality and safety (QSD) construct was theoretically built from the GAPs, and GPHMPs construct with two dimensions: certified bean (Cert_1) and ordinary bean (Ordinary_1). Certified and ordinary cocoa bean grain was measure by asking farmers records of the quantity of marketable beans sold as ordinary or/and certified beans in kilograms.

To test the model proposed by Lima et al. (Citation2011), we implemented a two-step approach by first carrying out an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and later set up and tested the SM. The SPSS software, version sixteen, was used for EFA, and SmartPLS software version 2 (Ringle et al., Citation2015) was used to analyze the SM.

2.4. Data analysis technique

In other to explore the construct dimensions, the researcher employed EFA to check if the proposed factor structure was indeed consistent with the actual data. Therefore, this was done using principal component analysis with varimax rotation as the extraction method. According to Field (Citation2009), the minimum value for an excellent factor loading analysis is 0.5, and only items with loadings above 0.5 were retained. The reliability and validity of the measurement model were thoroughly assessed (Hair et al., Citation2013). In other to specify a valid measurement model, it was imperative to establish satisfactory convergent and discriminant validities for the research model sequentially.

This algorithm employed in the study is the PLS-SEM, which is a Generalized Least Square method and is exploratory (Hair et al., Citation2014). The PLS-SEM does not assume normality in the distribution of data. Consequently, a parametric significance test cannot be applied to test whether coefficients are significant (Hair et al., Citation2017). In reality, the PLS-SEM entirely relies on the nonparametric bootstrapping procedure (Davison & Hinkley, Citation1997). It is known as resampling with replacement in obtaining the estimates for path coefficients and testing for significance since the data is not normally distributed (Hair et al., Citation2014). The PLS-SEM was the preferred method for many reasons. Garson (Citation2016) point out the advantages of PLS; the ability to model multiple dependent as well as numerous independent variables, ability to handle multicollinearity among the independents, robustness in the face of data noise and missing data, and creating independent latent variables directly based on cross products involving the response variable(s) with more robust predictions. Tsang (Citation2002) points out one key advantage of PLS-SEM: it allows for data analysis during the early stages of theory development. A disadvantage of PLS-SEM includes difficulties in interpreting the loadings of the independent latent variables, and because the distributional properties of estimates are not known, the researcher cannot assess significance except through Bootstrap induction (Garson, Citation2016). The SM was used to test or dis-confirm proposed theories involving explanatory relationships among various latent variables (Raykov & Marcoulides, Citation2006).

2.5. Empirical model

The researcher used the hierarchical component model (HCM) made up of two parts; the higher-order component (HOC), which considers the more abstract higher-order entity and the lower-order component (LOC), which captures the sub-dimensions of the higher-order entity. The higher-order construct is either formed or reflected by its dimensions as a lower-order construct (Becker et al., Citation2012). For this research, the reflective-formative HCM was adopted, which shows a formative relationship between HOC, LOC and all the first-order constructs, the reflective indicators measure (Hair et al., Citation2017). The hypothesized mathematical equations for the measurement model (MM) and the structural model (SM) shows the reflective-formative HCM.

2.5.1. The measurement model of farmers’ management practices

For the lower-order component model (LOC), Good Agricultural practices (GAP) is an endogenous latent variable build up from 6 indicators; CarryCH, DisIpods, Erosion, FSoim, FSprayPD, and IGA. The endogenous latent variable Good Post Harvest Management Practices (GPHMP) is built from three indicators; BrokenG, IGPHMP, and Mdry. Lastly, QSD is an endogenous latent variable with two dimensions; ordinary_1 and Cert_1. The endogenous latent variables and their indicators for the LOC model are presented mathematically.

Where:

Ai refers to the intercept associated with Equationequations 1(1)

(1) , Equation2

(2)

(2) and Equation3

(3)

(3) .

Β1, β2, … β6, are path loadings, β21, β22, and β23, are path loadings, and β31, and β32, are path weights.

Ɛi represents the error term of Equationequations 1(1)

(1) , Equation2

(2)

(2) and Equation3

(3)

(3) .

2.5.2. Structural model of farmers’ management practices

For the higher-order component model (HOC), Good Agricultural Practices (GAP) and Good Post Harvest Management Practices (GPHMP) are exogenous latent variables, while Quality and Safety Standard (QSD) is an endogenous latent variable. The model also includes an interactive term (GAP*GPHMP), which is an exogenous latent variable that predicts QSD. The model is presented mathematically.

Where:

αi represents the inner path coefficient, and µi represents the error term.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Characteristics of Cocoa Farmers

Ninety-three percent of the respondents were male. The sample is highly represented by those with no formal education (40.8%), followed by primary school (34%). Secondary and tertiary education were represented at 18.4% and 6%, respectively. Respondents aged between; 40–49 years formed the largest group (37.3%), 50–59 years were 25.4%, 30–39 years were 20.9 %, 20–39 were 11.4%, and age group greater than 59 years were 5%. Respondents’ marital status distribution was; 43.3% married, 12.4% divorced, 22. 9% widowed, and 20.45% singled. A significant proportion of farmers received premiums (67.7%) in the last three years.

3.2. Assessment of reflective-formative measurement of farmers’ farm management practices

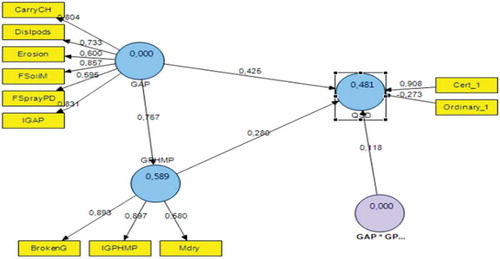

The indicators used for analysis have factor loadings higher than 0.5 (Field, Citation2009) from EFA. Figure shows a reflective-formative model. For the reflective part, based on theory, the indicators are highly correlated, interchangeable, and the direction of causality is from construct to item. For the formative part, the indicators represent the constructs’ independent causes, are not highly correlated and are not interchangeable among themselves (Jarvis et al., Citation2003). The initial step in the PLS-SEM is to assess for reliability and validity of key indicators and latent variables.

3.3. Results of the reflective-measurement: Reliability assessment of farmers’ farm management practices

In Table the Cronbachs alpha values for the exogenous latent variables GAP (O,834), GPHMP (0,717) and GAP*GPHMP (0,881) is above the 0.7 threshold (Rossiter, Citation2002). The value of the composite reliability for all three exogenous indicators, GAP (O,880), GAP*GPHMP (0,855), and GPHMP (0,841), is above the 0.7 threshold (Rossiter, Citation2002). The indicators of Erosion, FSprayPD, Mdry, and Ordinary_1 have individual indicator reliability values smaller than the minimum acceptable level of 0.4. The indicators CarryCh, DisIPods, FSiolM, IGAP, BrokenG, IGPHMP and Cert_1, have individual indicator reliability values that are larger than the minimum acceptable level of 0.4 (Hulland, Citation1999). However, since PLS-SEM does not emphasize the purpose of indicator reliability; instead, the significance of the indicator was tested using resampling techniques such as bootstrapping (Chin, Citation1998).

Table 2. Summary results of reflective outer models

In Table the average variance extraction (AVE) of GAP (0.554) and GPHMP (0.647) surpassed 0.5 (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981). Therefore, this shows that convergent validity was confirmed for GAP and GPHMP.

Discriminant validity was assessed in Table using the Fornell-Larcker criterion (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981). The latent variable GAP’s average variance extraction (AVE) was found to be 0.554, and its square root is 0.744. This value is larger than the two correlation values for the different constructs in the column of GAP (0.144 and 0.657), and smaller than one of the values (0.767). The latent variable GPHMPs’ AVE was found to be 0.647, and its square root is 0.804. This value is larger than that of all the correlation values for different constructs in the column of GPHMP (0.625), and the row of GPHMP (0.767 and 0.162). Optimum validity and reliability were demonstrated for all the checks.

Table 3. Fornell-Larcker criterion

3.4. Results of the formative-measurement model of farmers’ farm management practices

For the evaluation of our formative-MM of QSD, the researcher implements a series of guidelines proposed by Hair et al. (Citation2013) and Centfetelli and Bassellier (Citation2009). The study addresses each formative indicators’ contribution to the formative construct score created by aggregating the formative indicators of a construct using indicators’ weight (Götz et al., Citation2010). The indicators’ weight should be significant, its magnitude should be greater than 0.10, and its sign should be consistent with the underlying theory (Andreev et al., Citation2009). The bootstrapping technique of generating 50,000 subsamples was used to test for significance (Preacher & Hayes, Citation2008).

Table shows that QSD has two formative indicators Cert_1 and Ordinary_1 bean, which are significant at 1% and 5%, respectively. Their indicator weight is 0.908 and −0.273 for Cert_1 and Ordinary_1, respectively, and their magnitude is greater than the cut-off value of 0.01. The sign of their weight is positive and negative for Cert_1, and Ordinary_1, respectively, which is in line with existing theory and the empirical model. Therefore, there is empirical support and both items were included in the data sample set.

Table 4. Formative measurement model

3.5. Assessment of the structural model of farm management practices

The correlation between all the constructs was also measured, and it was confirmed that there is no extreme multivariate collinearity in the data. To assess the formative-SM, the researcher evaluates; the coefficient of determination (R2), magnitude and significance of path coefficients to get an insight about the quality of the estimates (Hair et al., Citation2013). The bootstrapping technique was used to test for significance (Preacher & Hayes, Citation2008). The results are shown in Table and Figure and are interpreted as follow:

Table 5. Results of the structural model using reflective-formative measurement model of farmers’ farm management practices

GAP has a strong positive relationship and a highly statistically significant effect on GPHMP with its path coefficient (β) greater than 0.1 (T = 32.019 > 2.326, β = 0.767, p < 0.01), thus supported H01, at one tail-test.

GAP has a moderate positive relationship and a highly statistically significant impact on QSD at one tail test with its’ β greater than 0.1 (T = 6.449 > 2.326, β = 04.25, p < 0.01), thus supported H02, at one tail-test.

GAP*GPHMP has a weak positive relationship and a highly statistically significant impact on QSD with β greater than 0.1 (T = 2.414 > 2.326, β = 0.118, p < 0.01), thus supported H03, at one tail-test.

GPHMP has a weak positive relationship and a highly statistically significant impact on QSD with β greater than 0.1 (T = 3.705 > 2.326, β = 0.280, p < 0.10), thus supported H04, at one tail-test.

All the reflective indicators are significant at a 1% level, one tail-test. The R2 is 0,481 for QSD. Consequently, this means that the two latent variables (GAP and GPHMP) moderately explain 48.1% of the variance in QSD. The R2 is 0.589 for GPHMP. Therefore, this implies that GAP modestly explains 58.9% of the variance in GPHMP.

4. Discussion

In the last three years, a considerable number of farmers received premiums (67.7%). Given that certified farmers receive a slight net income increase for producing certified cocoa, this premium does make a difference in the overall return farmers make from their cocoa proceeds given that the paid premiums lead to overall marginal income increase. However, globally, about 20 to 60% of cocoa beans produced and processed as certified cocoa is never sold as certified cocoa beans (Fountain & Hütz-Adams, Citation2018). Hence, standards, rules, and regulations on the payment of farm gate prices and premiums put in place by Organic, Fairtrade, and Rainforest Alliance must be transparent. Another possible solution to help farmers keep producing certified cocoa beans is by reaching out to all farmers who produce certified cocoa beans with a premium and implementing a flexible premium policy. In such an instance, if the world market price goes down, the premium price goes up. Nevertheless, a key challenge is to see how certification programs can target farmers found in the interior parts of cocoa producing communities and not only focus on farmers who are easy to access. Consequently, this will intensify and increase the quantity of certified cocoa beans produced.

The findings revealed that GAP was directly associated with QSD, and GPHMP also had a direct relationship with QSD; hypothesis H02 and H04 were supported, respectively. The results also show that GAP was directly associated GPHMP; Hypothesis H01 supported. Accordingly, changing farmers’ behavior, and perception toward sustainable management practices will lead to a two-fold change in the cocoa sector; firstly, efficiency and effectiveness in implementing GPHMP will improve; secondly, it is vital to pursue increase production of safe and quality cocoa beans. Thus, this is similar to the results of Mutyasira et al. (Citation2018), who showed that changing farmers’ attitude and perception, increased awareness, and on-farm demonstrations are vital for the adoption of sustainable agricultural practices. Similar to the findings of Benjamin et al. (Citation2011), farmers were also well acquainted with sustainable management practices, with some of them strictly implementing adequate measures to ensure the production of the quality cocoa bean. These findings also support and confirm previous studies by Ansah et al. (Citation2018), Lima et al. (Citation2011), and Quarmine et al. (Citation2012), who found out that beans’ quality was dependent on farmers’ adoption of sustainable management practices.

Furthermore, the study shows that farmers have a better understanding of GAP (H02) with a strong predictive power (0.425) on QSD than GPHMP (H04) with a weak effect (0.280) on QSD that is moderated by GAP. Therefore, this means that the moderator has a significant moderating effect on the relationship between GPHMP and QSD. An increase (decrease) in the level of the moderator variable by one standard deviation unit, the simple effect value of GPHMP (0.280) will decrease (increase) by the size of the moderating effect (0.118), and the relationship between GPHMP and QSD will change to 0.161(0.398), respectively, ceteris paribus. The interactive term GAP*GPHMP (0.118) had a weak significant positive effect on farmers’ QSD; hypothesis H03. All the reflective indicators selected showed significant positive relationships with their corresponding latent variables, while the formative indicators were all in line with existing literature and a priori.

The study found out that most farmers did not fully adopted and implement GAP. The farmers’ soil management activities were inadequate, with soil erosion being one of the leading causes of declining soil fertility resulting from continuous rainfall. The result also supports the work of Benjamin et al. (Citation2011) that farmers’ management of pest and disease is inadequate, resulting in disease and pest-infested pods that are not correctly disposed of the farm to limit contamination of other cocoa pods. Farmers do not carry out timely and proper management of weeds, chupons, mistletoe, and some harvest and include infested pods for pod breaking, which negatively affect cocoa beans quality. Thus, these findings also support the work of Quarmine et al. (Citation2012) and Olujide and Adeogun (Citation2006).

The GPHMP of farmers was also found to be inadequate and not consistent with sustainable management practices. With defective wood oven dryers as the dominant drying medium, beans are in constant contact with smoke. Therefore, this affects the beans flavor and color, which is similar to literature in Agritrade (Citation2013) and Viban (Citation2018a). The use of traditional drying facilities means that farmers have to dry beans longer in other to meet the 8.00% threshold for certified cocoa beans, which is one of the critical determining factors for QSD of cocoa beans and this is similar to the work of Sefriadi et al. (Citation2013). Farmers who rely on sun drying did not raise their bean grains enough to prevent beans from coming into contact with foreign materials like stones and sticks. Most farmers did sort cocoa beans to ensure that they were free from smoke, contaminants, abnormal or foreign odor, broken and germinated beans, fragments and shell pieces.

This research finding has both practical and academic implications. It contributes to existing literature that GAP and GPHMP will increase the quantity of certified beans produced if well implemented (Levai et al., Citation2015; Olujide & Adeogun, Citation2006). It brings a unique contribution that; GAP has a significant positive effect on GPHMP. It has practical implications that the farmer will understand in detail the importance of sustainable management practices on the final quantity of certified cocoa beans produced. This study shows that continuous improvement in farmers’ behavior towards sustainable management practices will increase the quantity of certified cocoa beans produce. Some farmers were unable to produce a single kilogram of certified cocoa beans. However, some farmers produce only certified cocoa beans. Moreover, the study found that farmers’ knowledge of sustainable farm management practices is not essentially translated into practical activities on their farms. It entails going the extra mile for farmers to adopt and implement sustainable management practices fully.

5. Policy suggestions and conclusions

All the hypotheses supported the empirical results of the SM with all construct paths revealing a formative model with good predictive effect. The research revealed that GAP, GAP*GHPMP and GPHMP were predictors of QSD, and GAP was also a predictor of QSD via GPHMP-construct. Based on the findings that GAP has a significant positive impact on QSD, the results suggest that GAPs’ improvement by 1%, QSD goes up by 42.5%. The results also show that GPHMP also has a significant positive impact on QSD; hence, a 1% improvement in farmers’ GPHMP will lead to a 28.0% increase in the QSD of cocoa beans produced. Thus, this means that, if policies are geared towards improving farmers’ GAP and GPHMP, there will be an enormous increase in the QSD of cocoa beans produced. Consequently, this affirms that sustainable management practices have increased a considerable number of farmers’ efficiency and led to more certified cocoa beans production. However, cocoa farming will not be appealing until it can alleviate the poverty status of hardworking farmers.

The results further indicate that if farmers are motivated to increase production, sustainability is not necessarily assured since cocoa is bought in kilograms; farmers will include infested beans, beans with high moisture content and unwanted materials to increase quantity. However, if policies are formulated toward the sustainable production of safe and quality beans, the sector will experience a two-fold change in the future; firstly, quality and safety of the beans will increase does gaining consumers’ confidence in Cameroon cocoa beans; secondly, production will increase since there exists a strong relationship between quality and output. Hence policies should be geared towards incorporating sustainable, environmentally friendly management practices into agricultural development programs that will continuously improve farmers’ knowledge of safety and quality standards of cocoa production since it tends to increase farmers’ overall marginal income.

Acknowledgements

The Authors wish to acknowledge the assistance provided by Telca Cacao officials in the South West region of Cameroon.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Neville N. Suh

Neville Suh Ndohnwi is a Ph.D. student in the Department of Agribusiness Technology, University of Bamenda, Cameroon. This current article is from my master’s thesis. I am a holder of a Master of Science and Bachelor of Science in Agriculture (Agricultural Economics) from the University of Buea Cameroon in 2019 and 2014, respectively. I joined EMPOWERMENT NGO in the South West region of Cameroon in 2015, working as a field supervisor to date. Since 2016, I have served as a research assistant in the Association for Biodiversity, Research and Sustainable Development (ABiRSD), South West Region, Cameroon. I have a research interest to contribute to the furtherance of food security, digital technology in farming, climate change and environmental governance.

References

- Agritrade. (2013). The ‘quiet evolution’ of Cameroon’s cocoa sector. Retrieved December 04, 2017, from http://agritrade.cta.int/Agriculture/Commodities/Cocoa/The-quiet-evolution-of-Cameroon-s-cocoa-sector.html

- Ajzen, I. (1985). From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior. In Kuhl J., Beckmann J. (eds), Action control (pp. 11–18). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-69746-3_2

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

- Ajzen, I. (2011). The theory of planned behavior: Reactions and reflections. Psychology & Health, 26(9), 1113–1127. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2011.613995

- Ajzen, I. F. M. (1980). Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. Prentice Hall.

- Akmel, D. C., Nogbou, A. L. I., Cisse, I., Kakou, K. E., Kone, K. Y., Assidjo, N. E., & Yao, B. (2016). Comparison of post-harvest practices of the individual farmers and the farmers in cooperative of Côte d’Ivoire and statistical identification of modalities responsible of non-quality. Journal of Food Research, 5(6), 102–113. https://doi.org/10.5539/jfr.v5n6p102

- Andreev, P., Heart, T., Maoz, H., & Pliskin, N. (2009). Validating formative partial least squares (PLS) models: Methodological review and empirical illustration. ICIS 2009 proceedings (pp. 193). http://aisel.aisnet.org/icis2009/193

- Ansah, G. O., Ofori, F., & Siaw, L. P. (2018). Rethinking Ghanas Cocoa Quality: The stake of license buying companies (LBCs) in Ghana. Journal of Agricultural Science and Food Research, 9(224), 2.

- Armitage, C. J., & Conner, M. (2001). Efficacy of the theory of planned behaviour: A meta‐analytic review. British Journal of Social Psychology, 40(4), 471–499. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466601164939

- Baffoe-Asare, R., Danquah, J. A., & Annor-Frempong, F. (2013). Socioeconomic factors influencing adoption of CODAPEC and cocoa high-tech technologies among small holder farmers in Central Region of Ghana. American Journal of Experimental Agriculture, 3(2), 277–292. https://doi.org/10.9734/AJEA/2013/1969

- Becker, J. M., Klein, K., & Wetzels, M. (2012). Hierarchical latent variable models in PLS-SEM: Guidelines for using reflective-formative type models. Long Range Planning, 45(5–6), 359–394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2012.10.001

- Benjamin, T. A., Eunice, F., & Vivian, F. B. (2011). Farmers’ management practices and the quality of cocoa beans in upper Denkyira district of Ghana. Asian Journal of Agricultural Science, 3(20), 487–491.

- Booth, R., Hernandez, M., Baker, E., Grajales, T., & Pribis, P. (2013). Food safety attitudes in college students: A structural equation modeling analysis of a conceptual model. Nutrients, 5(2), 328–339. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu5020328

- Business in Cameroon (BIC). (2018). Retrieved January 03, 2018, from https://www.businessincameroon.com/agriculture/1908-6445-almost-97-of-cocoa-production-exported-by-cameroon-during-the-2015-2016-campaign-was-grade-ii

- Business in Cameroon (BIC). (2020). Retrieved August 06, 2020, from https://www.businessincameroon.com/agriculture/1503-8945-cameroon-cocoa-farm-gate-price-exceeds-xaf1-000-perkg-as-wet-season-approaches

- Buzby, J. C. (2003). International trade and food safety: Economic theory and case studies. United States Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service.

- Centfetelli, R. T., & Bassellier, G. (2009). Interpretation of formative measurement in information systems research. MIS Quarterly, 33(4), 689–708. https://doi.org/10.2307/20650323

- Chin, W. W. (1998). The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. Modern Methods for Business Research, 295(2), 295–336.

- Chinda, T., & Suanmali, S. (2017). Structural equation modeling of food safety standard in the Cassava Industry in Thailand. Suranaree Journal of Social Science, 11(1), 89–108.

- David, B. (2013). Competitiveness and determinants of cocoa exports from Ghana. International Journal of Agricultural Policy and Research, 1(9), 236–254.

- Davison, A. C., & Hinkley, D. V. (1997). Bootstrap methods and their application (Vol. 1). Cambridge university press.

- Field, A. (2009). Discovering statistics using SPSS (3rd ed.). Sage publications Ltd.

- Folayan, J. A. (2010). Nigerian cocoa and cocoa by-products: Quality parameters, specification and the roles of stakeholders in quality maintenance. Pakistan Journal of Nutrition, 9(9), 915–919. https://doi.org/10.3923/pjn.2010.915.919

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104

- Fountain, A., & Hütz-Adams, F. (2018). Cocoa barometer (No. BOOK_B). Public Eye. https://www.patrinum.ch/record/176357

- Garson, G. D. (2016). Partial least squares: Regression and structural equation models. Statistical Associates Publishers.

- Gereffi, G., & Lee, J. (2009). A global value chain approach to food safety and quality standards. Global Health Diplomacy for Chronic Disease Prevention, Working Paper Series. Duke University.

- Godin, G., & Kok, G. (1996). The theory of planned behavior: A review of its applications to health-related behaviors. American Journal of Health Promotion, 11(2), 87–98. https://doi.org/org/10.4278/0890-1171-11.2.87

- Götz, O., Liehr-Gobbers, K., & Krafft, M. (2010). Evaluation of structural equation models using the partial least squares (PLS) approach. In Esposito Vinzi V., Chin W., Henseler J., Wang H. (Eds.), Handbook of partial least squares (pp. 691–711). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-32827-8_30

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2013). A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM). Sage.

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2014). A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). Sage.

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) (2nd ed.). Sage.

- Hulland, J. (1999). Use of partial least squares (PLS) in strategic management research: A review of four recent studies. Strategic Management Journal, 20(2), 195–204. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(199902)20:2<195:AID-SMJ13>3.0.CO;2-7

- Hütz-Adams, F., Huber, C., Knoke, I., Morazán, P., & Mürlebach, M. (2016). Strengthening the competitiveness of cocoa production and improving the income of cocoa producers in West and Central Africa. Südwind.

- International Cocoa Organization (ICCO). (2008a). Annual report 2006/2007. International Cocoa Organization. Retrieved January 12, 2018, from https://www.icco.org/about-us/international-cocoa-agreements/cat_view/1-annual-report/23-icco-annual-report-in-english.html

- International Cocoa Organization (ICCO). (2008b). Manual of best practices in cocoa production. Consultative Board on the World Cocoa Economy. Sixteenth meeting. ICCO. Retrieved January 12, 2018, from https://www.icco.org/sites/www.roundtablecocoa.org/documents/CB-16-2%20-%20ICCO%20-%20Best%20known%20practices.pdf

- International Cocoa Organization (ICCO). (2011). Annual Report 2011/2012. Retrieved August 12, 2018, from https://www.icco.org/about-us/icco-annual-report.html

- International Cocoa Organization (ICCO). (2017). Annual Report 2016/2017. Retrieved August 1, 2020, from https://www.icco.org/about-us/icco-annual-report.html

- Jarvis, C. B., MacKenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, P. M. (2003). A critical review of construct indicators and measurement model misspecification in marketing and consumer research. Journal of Consumer Research, 30(2), 199–218. https://doi.org/10.1086/376806

- Kimengsi, J. N., & Azibo, B. R. (2015). How prepared are Cameroon’s cocoa farmers for climate insurance? Evidence from the south west region of Cameroon. Procedia Environmental Sciences, 29, 117–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proenv.2015.07.196

- Klynveld Peat Marwick Goerdeler (KPMG). (2017). Cameroon Economic Snapshot H2.

- Lernoud, J., Potts, J., Sampson, G., Schlatter, B., Huppe, G., Voora, V., Willer, H., & Wozniak, J. (2015). The state of sustainable markets: Statistics and emerging trends. In The World of organic agriculture (pp. 130).

- Levai, L. D., Meriki, H. D., Adiobo, A., Awa-Mengi, S., Akoachere, J. F. T. K., & Titanji, V. P. (2015). Postharvest practices and farmers’ perception of cocoa bean quality in Cameroon. Agriculture & Food Security, 4(1), 28. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40066-015-0047-z

- Lima, L. J., Almeida, M. H., Nout, M. R., & Zwietering, M. H. (2011). Theobroma cacao L.,“The food of the Gods”: Quality determinants of commercial cocoa beans, with particular reference to the impact of fermentation. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 51(8), 731–761. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408391003799913[

- Meijer, S. S., Catacutan, D., Sileshi, G. W., & Nieuwenhuis, M. (2015). Tree planting by smallholder farmers in Malawi: Using the theory of planned behaviour to examine the relationship between attitudes and behaviour. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 43, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2015.05.008

- Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development (MINADER). (2012). Annual Report 2012 for the South West. Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development for Cameroon. Report Retrieved from the Divisional Delegates Office.

- Ministry of Environment, Protection of Nature and Sustainable Development (MINEPDED). (2012). National biodiversity strategic and action plan Version II. https://www.cbd.int/doc/world/cm/cm-nbsap-v2-en.pdf

- Moki Kindzeka. (2013). New European Union import laws hurt African cocoa exports. https://p.dw.com/p/18fQ2

- Mubeteneh, T. C. (2007). Cameroon cocoa story. University of Dschang. Retrieved June 11, 2018, from http://www.supplychainge.org/fileadmin/reporters/at_files/Cameroon_cocoa_story.pdf

- Mukete, N., Li, Z., Beckline, M., & Patricia, B. (2018). Cocoa production in Cameroon: A socioeconomic and technical efficiency perspective. International Journal of Agricultural Economics, 3(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ijae.20180301.11

- Mutyasira, V., Hoag, D., Pendell, D., Manning, D. T., & Berhe, M. (2018). Assessing the relative sustainability of smallholder farming systems in Ethiopian highlands. Agricultural Systems, 167, 83–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2018.08.006

- Niemenaka, N., Eyamoa, J. A., Onomoa, P. E., & Youmbi, E. (2014). Physical and chemical assessment quality of cocoa beans in south and center regions of Cameroon. Journal of Syllabus Reviews Science Series, 5(2014), 27–33.

- Observatory Economic Complexity (OEC). (2018). Cameroon export, imports and trade patterns. OEC-the observatory of economic complexity. Retrieved August 1, 2020, from https://oec.world/en/profile/country/cmr/

- Olujide, M. G., & Adeogun, S. O. (2006). Assessment of cocoa growers’ farm management practices in Ondo State, Nigeria. Spanish Journal of Agricultural Research, 4(2), 173–179. https://doi.org/10.5424/sjar/2006042-189

- Pacific Agribusiness Research & Development Initiative (PARDI). (2012). Cocoa value chain review. Pacific Agribusiness Research & Development Initiative. Retrieved August 09, 2018, from https://www.adelaide.edu.au/global-food/documents/pardi-cocoa-chain-review-oct-2012.pdf.

- Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40(3), 879–891. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.40.3.879

- Quarmine, W., Haagsma, R., Sakyi-Dawson, O., Asante, F., Van Huis, A., & Obeng-Ofori, D. (2012). Incentives for cocoa bean production in Ghana: Does quality matter? NJAS-Wageningen Journal of Life Sciences, 6(63), 0,7–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.njas.2012.06.009

- Raykov, T., & Marcoulides, G. A. (2006). A first course in structural equation modeling (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

- Royal Tropical Institute, AgroEco/Louis Bolk Institute, & Tradin. (2010). Organic Cocoa production in Cameroon and Togo. http://www.cocoaconnect.org/sites/default/files/publication/Feasibility%20Study%20organic%20cocoa%20-%20Togo%20and%20cameroon.pdf

- Raza, M. H., Abid, M., Yan, T., Ali Naqvi, S. A., Akthar, V. S., & Faisal, M. (2019). Understanding farmers’ intentions to adopt sustainable crop residue management practices: A structural equation modeling approach. Journal of Cleaner Production,227(29), 613-623. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.04.244

- Ringle, C. M., Wende, S., & Becker, J. M. (2015). SmartPLS 3. SmartPLS. Retrieved December 20, from https://www.smartpls.com/

- Rossiter, J. R. (2002). The C-OAR-SE procedure for scale development in marketing. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 19(4), 305–335. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167-8116(02)00097-6

- Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., Raithel, S., & Gudergan, S. P. (2014). In pursuit of understanding what drives fan satisfaction. Journal of Leisure Research, 46(4), 419–447. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222216.2014.11950335

- Sefriadi, H., Villano, R., Fleming, E., & Patrick, I. (2013). Production constraints and their causes in the cacao Industry in West Sumatra: From the farmers’ perspective. International Journal of Agricultural Management, 3(1), 30–42. https://doi.org/10.5836/ijam/2014-01-05

- South West Region. (2019). South West region (Cameroon). https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Southwest_Region_(Cameroon)

- Standard Trade Development Facility (STDF). (2014). Training of master facilitators. ‘CocoaSafe’: Capacity Building and Knowledge Sharing in SPS in Cocoa in South East Asia (STDF/PG/381). Retrieved August 09, 2018, from http://www.standardsfacility.org/sites/default/files/PG_381_TOMF_Manual_Malaysia%26Indonesia.pdf

- Tosam, J., & Njimanted, G. (2013). An analysis of the socio-economic determinants of cocoa production in Meme Division, Cameroon. Greener Journal of Business and Management Studies, 3(6), 298–308. https://doi.org/10.15580/GJBMS.2013.6.072313748

- Tsang, E. W. (2002). Acquiring knowledge by foreign partners from international joint ventures in a transition economy: Learning‐by‐doing and learning myopia. Strategic Management Journal, 23(9), 835–854. https://doi.org/org/10.1002/smj.251

- Viban, J. (2018a). Ban on Cameroon Cocoa exports feared in Europe. Business in Cameroon. Retrieved April 03, 2017, from https://www.businessincameroon.com/cocoa/1203-3968-ban-on-cameroon-cocoa-exports-feared-in-europe

- Will, M., & Guenther, D. (2007). Food Quality and Safety Standards as required by EU Law and the Private Industry with special Reference to MEDA Countries ‘Exports of Fresh and Processed Fruits and Vegetables, Herbs and Spices. In GTZ-Division 45 (Ed.). A Practitioners ‘Reference Book.

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2003). Assuring food safety and quality: Guidelines for strengthening national food control systems. In Assuring food safety and quality: guidelines for strengthening national food control systems. WHO. Retrieved January 13, 2018, from https://www.who.int/foodsafety/publications/guidelines-food-control/en/

- Xayavong, V., Kingwell, R., & Islam, N. (2016). How training and innovation link to farm performance: A structural equation analysis. Australian Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics, 60(2), 227–242. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8489.12116