Abstract

This review assessed the status of food insecurity in Ethiopia with a special focus on dryland areas. Food security is achieved when all people, at all times, have physical and economic access to sufficient, safe, and nutritious food that meets their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life. In contrast, food insecurity occurs when individuals, households, or an entire have neither physical nor economical access to the nourishment they need. Food insecurity causes people great difficulty, especially in the dryland areas of Ethiopia. Hence, improving food security policies and intervention mechanisms requires theoretical and empirical evidence on the current food insecurity situation. Nearly 33 million people in Ethiopia suffer from chronic undernourishment and food insecurity of which 25% are in need of urgent assistance. The severity is more pronounced in the arid and semiarid rangelands of Ethiopia which comprises nearly 13% of the population and constitute about 63% of the country’s landmass. The result of the empirical review indicated, especially in dryland areas of Ethiopia, the majority of households were food insecure. Drought risks, desert locus, the spread of corona varies, protracted impacts of past poor seasons, conflict, poor household income, cost of nutritious food, and knowledge on nutritious food factors are the major drivers of food insecurity. The international non-governmental organizations, local organizations, private sector, and government should continue to work together to adopt drought risk-friendly modern technologies and design new production-oriented and commercialization policies to improve food security.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Food is a basic means of sustenance and a human right and having enough food in terms of quantity and quality for all people is an important factor for a healthy and productive life. Food insecurity is a topic of keen interest to policymakers, practitioners, and academics around the world in large part which is defined as people who lack secure access to sufficient amounts of safe and nutritious food for normal growth and development and an active and healthy life. Currently, Ethiopia is one of the most food-insecure and famine-affected country having nearly 33 million people are suffering from chronic undernourishment and food insecurity with 8.1 million food-insecure people in need of urgent action. The severity is more in dryland areas of the country due to drought risks, erratic rainfall, pest infestations, and disease outbreaks, and these regions have become heavily dependent on external food aid.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

It is widely accepted that food is a basic means of sustenance and a human right. Having enough food in terms of quantity and quality for all people is an important factor for a healthy and productive life (FAO, Citation2014; Sani & Kemaw, Citation2017). Adequate intake of quality food is needed condition to be well-nourished and indicates the food security status of a household. In contrast, food insecurity exists when people lack access to an adequate and safe supply of food on a stable basis (FAO, Citation2005).

Food security is a topic of keen interest to policymakers, practitioners, and academics around the world in large part because the consequences of food insecurity can affect almost every facet of society (Feleke, Citation2019). For example, the food price crisis and subsequent food riots in 2007–2008 highlighted the critical role of food security in maintaining political stability (Jones et al., Citation2013). Reports indicate that about 795 million people in the world were food insecure, with many more sufferings from “hidden hunger” caused by micronutrient or protein deficiencies (FAO, I. & UNICEF, Citation2015). Although the prevalence of undernourishment declined from 32.7% to 24.8% over the last two decades, Sub-Saharan Africa has the highest prevalence of undernourishment (American Foundation for Surgery of the Hand [AFSH], Citation2014).

As a part of Africa and the developing world, Ethiopia is one of the most food-insecure and famine-affected countries as a large portion of the population is affected by food insecurity. The Ethiopian economy is mainly dependent on agriculture which is vulnerable to different shocks, seasonality, and trends (Bedemo et al., Citation2014). For example, in the country, most areas are exacerbated by low production and crop loss mainly caused by seasonal unpredictable and sporadic rainfall and climate shocks, mainly occurrence of drought which often results in low farm production, widespread lower-income, and subsequent food shortages and famines (Urama & Ozor, Citation2010). According to Bezu (Citation2018) in Ethiopia, nearly 33 million people are suffering from chronic undernourishment and food insecurity with the highest percent of the food-insecure population living in dryland areas. According to the report of the ministry of agriculture and rural development (MoARD, Citation2009), arid and semiarid rangelands of Ethiopia comprise nearly 13% of the population, while these areas constitute about 63% of the country’s landmass.

According to the report of FAO (Citation2018), the main causes of food insecurity in most drylands of Ethiopia are prolonged drought, conflict, and political instability, crop disease, flooding, protracted impacts of past poor seasons, desert locusts, poor household income, and cost of nutritious foods and knowledge on nutritious food factors. And also, the report shows, in Ethiopia, prolonged drought conditions are severely affecting the livelihoods in most southern and southeastern dryland areas of south nation nationality people which is a part of the state (region), southern Oromia, and southeastern Somali Regions, where cumulative seasonal rainfall was up to 60% below average.

To reverse this problem, the government of Ethiopia has been formulating and implementing various strategies and programs like productive safety net program (a platform to provide emergency-related support to vulnerable households in need of relief cash/food in times of shocks) and agricultural development led industrialization (example, Growth and Transformation Plan one and two) in which food security strategy is a key component. To foster broad-based development in a sustainable manner, the growth and transformation Plan (GTP I) (2010/11- 2014/15) was implemented. Generally, the aim of the plan was significantly increasing the share of industry in the economy along with the rise in agricultural production. Hence, according to Dube et al. (Citation2019) during the GTP I implementation period, there was a positive achievement in the economic growth of the country such as double-digit growth rate of real GDP and decline in the incidence of poverty from 38.7% headcount poverty index in 2005 to 29.6% in 2010/11. Similarly, GTP 11 (2015/16-2019/20) is a continuation of GTP 1, and giving more emphasis on humanitarian challenges arising from climatic change continued affecting the economic growth of the country, and production of high-value crops and livestock, and market orientation (Dube et al., Citation2019).

In addition, pastoral and agro-pastoral households’ in the dryland areas of Ethiopia use different kinds of coping mechanisms to reduce the incidence of food insecurity. As coping strategies, mobility of pastoralists exploiting the animal feed resources along different ecological zones represents a flexible response to a dry and increasingly variable environment because animal byproduct like milk is the main source of food. This means pastoralists are movable in searching for better animal feed sources because in most dryland areas the rainfall is very erratic. Hence, pastoralists move in areas having rainfall and feed their animal grass which is the only source of animal feed. However, constraints on pastoral mobility, such as changes in land use, tenure regulations, and borders, have undermined the whole pastoral system and results in the problem of food insecurity continued to persist in the country (FAO, Citation2018).

Since the problem is more severe, especially in the dryland areas of the country, the government of Ethiopia has recently appealed to its international partners for emergency food assistance to feed 10.2 million people and for special nutritional programmers‟ for more than 2.1 million, including 400,000 severely malnourished children. In addition, over 8 million vulnerable and food-insecure people receive support under the Productive Safety Net Programme (Nkunzimana et al., Citation2016). Thus, this review synthesizes the status of household food insecurity and drivers of food insecurity which provides important information to policymakers, practitioners, academics, and other concerned bodies to intervene and improve the food security status of the households in the country.

1.2. Objectives

The overall objective of the review was to assess food insecurity status in Ethiopia, special focus on dryland areas.

Specifically, the study was trying:

To review the possible major sources of food insecurity;

To review the extent of food insecurity status of households.

1.3. Methodology

Since this paper is a review article; it was synthesized based on an intensive reading of published and unpublished journals, articles, and books. To shorten the paper, in addition to narrations, tables and figures were used as a reviewing technique.

2. Review of related literature

2.1. Definitions and concepts of food security

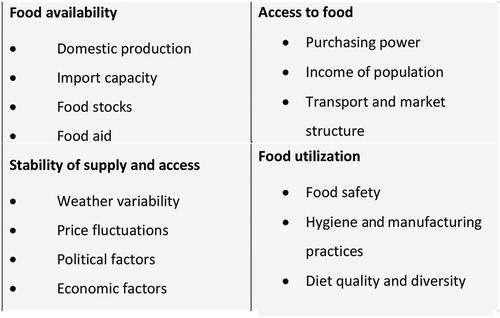

According to Al et al. (Citation2008), a country or region is food secure when all people, at all times, have physical and economic access to sufficient, safe, and nutritious food that meets their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life. Similarly, Amwata (Citation2004), and Nyariki and Wiggins (Citation1999) define food security as the availability of an adequate diet all year round for an active healthy life (2250 kcal/AE (adult equivalent)/day). Hence, food security is attained when sufficient growth in food crops and livestock is achieved not only to maintain output per person but also to reduce food calorie deficits, and to lower food imports (Nyariki & Wiggins, Citation1999). And also, Al et al. (Citation2008), and Marion (Citation2011) found that food availability, access, stability, and utilization are the four pillars of food security. Therefore, to realize food security objectives, the four pillars must be fulfilled, simultaneously.

As mentioned previously, food insecurity exists when “people lack secure access to sufficient amounts of safe and nutritious food for normal growth and development and an active and healthy life” (Marion, Citation2011). In line with this definition, factors that may lead to a situation of food insecurity include non-availability of food, lack of access, improper utilization, and instability over a certain time period.

Al et al. (Citation2008) measured food insecurity in two ways, which are chronic and transitory. Chronic food insecurity is a long-term or persistent condition and occurs when people are unable to meet their minimum food requirements over a sustained period of time. It results from extended periods of poverty, lack of assets, and inadequate access to productive or financial resources (FAO, Citation2008). Contrarily, transitory food insecurity is short term and temporary and occurs when there is a sudden drop in the ability to produce or access enough food to maintain a good nutritional status. This means transitory food insecurity is caused by short-term shocks and fluctuations in food availability and food access, including year-to-year variations in domestic food production, food prices, and household incomes (FAO, 2008).

2.2. Food insecurity situations in Ethiopia

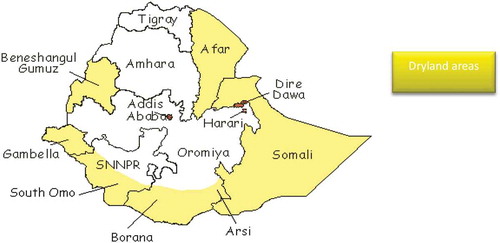

In Ethiopia, food insecurity is highly prevalent in the moisture deficit highlands and in the lowland pastoral and agro-pastoral dryland areas. Abule et al. (Citation2005) identified the six regions of dryland area in Ethiopia, considering the environmental conditions, floristic composition, and productivity values (). These arid and semiarid rangelands of Ethiopia has shown in , comprise nearly 13% of the population, having 63% of the country’s landmass (MoARD, Citation2009).

Even in years of adequate rainfall and good harvest, the people, particularly in dryland pastoral and agro-pastoral areas remain food insecure and in need of food assistance. In dry (low land) areas, droughts have become frequent and more severe in recent years and are one of the most important triggers of malnutrition and food insecurity in the country (Dominguez, Citation2010). In most of these areas, the rainfall is raining in a very short period of time, starting from June to August; the remaining time of the year is dry. Even though in this time, the level of rainfall is very erratic result in droughts and other related disasters (such as crop failure, water shortage, and livestock disease, land degradation, limited aid household assets, low income) (Mohamed, Citation2017).

According to (Food Security Information Network [FSIN], Citation2020), among intergovernmental authority for development (IGAD) countries, Ethiopia was the most food-insecure country in the region with 8.1 million food-insecure people in need of urgent action, followed by Sudan with 6.2 million, and South Sudan with 6.1 million. The problem is more severe in the dryland areas of the region because, mostly, prolonged dry conditions and flash floods negatively affected pastoral and agro-pastoral livelihoods by causing below-average crop production, pasture, as well as limiting water sources for both, and results in chronic and acute food insecurity is prevalent. As a result, these regions have become heavily dependent on external food aid.

The Integrated Food Security Phase Classification [IPC], Citation2020 classifies food insecurity into five phases ; phase one (People minimally food insecure), phase two (People in Stress), phase three (people in crises), phase four (people in an emergency) and phase five (people in catastrophe). The report also evidenced of the 8 million food-insecure people in Ethiopia, 21% is severely food insecure at the IPC Phase three-level, 38% IPC phase two, 34% IPC phase one, 6-% IPC phase four, and 0-% IPC phase five. The analysis includes all food-insecure households irrespective of whether they benefit from a productive safety net program (PSNP), including current internally displaced persons or returnees.

The worst-hit populations are distributed in the south, southeast, central, and north-eastern areas of the six regions of Ethiopia (). From 8 million people in IPC Phase 3 (Crisis) and above requiring urgent action to save lives, reduce food gaps, restore livelihoods, and reduce malnutrition, 44% are in Oromia, 22% are in Somali, 13% are in south nation nationalities and republic of Ethiopia (SNNPR), 10% are in Amhara, 5% are in Afar and are 5% in Tigray (). This table includes internally displaced persons, who have had to leave their homes due to unrest or with violence, conflict, and climatic shocks, erratic rainfall, pest infestations, and disease outbreaks negatively affecting the lives and livelihoods of vulnerable people. And will likely increase through 2020 due to the spread of novel coronavirus (COVID-19) as travel restrictions and economic disruptions hinder peoples’ income and access to food.

Table 1. Current food insecurity situation of the population in the regions

2.3. Drivers of food insecurity

According to the report of Family Early Warning Systems Network [FEWS NET] and World Food Program [WFP] (Citation2020), In Ethiopia, causes of food insecurity have always been complex given that multiple factors affect food security. In most dryland areas of Ethiopia, the level of rainfall is very erratic and raining in a short period of time (mostly, June to August) and flooding is also a major problem at this time. In addition, there are increased daily air temperatures throughout the year. These climate changes (weather variability) affect cropping and pasture which reduces crop yield and results in poor dietary diversity and consumption. Hence, erratic rains, uneven distribution, and long dry spells resulted in late planting and poor crop development, poor pasture regeneration, and low water availability are the key drivers of food insecurity which negatively impacts the four pillars of food security in Ethiopia (). Similar to, COVID-19 has affected the transport and market structure and results in economic disruptions. In addition, in the future, it may be one major source of food insecurity which negatively impacts the four pillars of food security in Ethiopia depending on its spread level throughout the country.

The report also indicates, currently, the desert locust is a problem in some areas of Ethiopia which affect crop production and pasture. It spread over in most Dryland area of Ethiopia, across areas of Somali, Afar, eastern lowlands of Amhara, Oromia, and south nation nationalities and people regions because desert locusts would invade a larger extent of lowland and main cropping areas due to high temperatures. Hence, it is one factor that results in food security which directly and indirectly affects the four pillars of food insecurity ().

Markets are the major sources of food. However, in most dryland areas of Ethiopia, market prices are not favorable for households, following a persistent increase in cereal prices due to shortages coupled with other factors. The recent spike of food prices, largely driven by a limited supply of cereals and erupting conflicts in most parts of the region, affected households dependent on staple foods. The conflict facing is recurrent inter-communal, especially over water and pasture. The conflicts have limited the movements of households and their livestock and led to disruptions in the major markets, limiting physical access to food and affecting prices, and continue to affect the food security (IPC, Citation2020)

In addition, Gebremichael and Asfaw (Citation2019) reported, driving factors of food choice included protracted impacts of past poor seasons, poor household income, cost of nutritious foods, availability of nutritious foods, quality of foods, familiarity with new foods, knowledge on nutritious foods, and health conditions of individuals.

2.4. Empirical review: status of food insecurity

Food insecurity in Ethiopia is most widespread in pockets of extreme poverty, particularly in rural areas; traditional agricultural or general economic interventions alone are unlikely to generate substantial improvements (Burchi et al., Citation2018). But, it is more pronounced in the dry land areas relative to other parts of the country because, in these parts of the country, agricultural production and productivity are highly vulnerable to climate variables. The households’ food insecurity status can be measured by using a direct survey of income, expenditure, and consumption. Different scholars found that there is a high incidence of food insecurity in different parts of the country.

Kahsay et al. (Citation2020) analyzed the food security status and its determinants in pastoral and agro-pastoral districts of Afar regional state, Ethiopia, using 150 sampled respondents. As a result, they found that 72.67% of the sample households were found to be food insecure at an average consumption of 2100 Kcal/AE/day as the cut-off point. And they identified the variability in per capita food available among the households was also extremely wide, ranging between 206 and 7835 Kcal/AE/day. That is, the mean per capita food available for the food secure and insecure households was 2825.21 and 1103.18Kcal/AE/day, respectively. Further analyzed, the overall mean for the districts was 1040 Kcal/AE/day; which is 51.5% below the 2100 Kcal/AE/day. Finally, they concluded that the majority of the households in the sample districts were food insecure because the district is a very dryland area and having the erratic climatic conditions. Since, the district is arid, dryland/rain-fed agriculture is practiced with a major and deeply rooted barrier to consuming nutritious/healthful foods. The occurrence of repeated drought in this area makes it one of the most climate change vulnerable groups on the planet (Thornton et al., Citation2009).

Agidew and Singh (Citation2018) evaluated the determinants of food insecurity in the rural farm households of the Teleyayen sub-watershed in Ethiopia. The data were collected from 215 sample households. The study adopted a simple household food balance model, and the converted results were divided by the number of household members as adult equivalent and the number of days in the recall period. Consequently, the results were compared with the minimum daily recommended food energy intake of 2100 kcal per adult equivalent and used as the cutoff level for classifying food-insecure households. As a result, they found that 79.1% of the sample households are food insecure. They also identified the majority of the food-insecure households had younger household heads, who own less than 1 ha of farmlands. Accordingly, the study concluded that the study area was mostly affected by food insecurity, land degradation in the form of soil erosion, and nutrient depletion. Moreover, the area was prone to low and erratic rainfall and frequent droughts.

Tesfaye and Ruach (Citation2019) investigated food insecurity and coping strategies among agro-pastoral households in Lare district, Ethiopia. They used households’ food or calorie acquisition/consumption per adult per day to identify the food secure and food-insecure households. The calories consumed by a household were compared with the minimum-recommended calories of 2100 kcal per adult per day. Data used were from available food for consumption from home production, purchase on the available food for consumption, from home production, purchase, and/or gift/loan/wage in kind for the previous 7 days before the survey day. As a result, they found that from all 160 respondents, 40 (33.75%) were food insecure. The mean calorie amounts were 2528.04 kcals for a food security and 1785.71 kcals for food-insecure households.

Similarly, Sani and Kemaw (Citation2019) analyzed households’ for food insecurity and the coping mechanisms in Western Ethiopia. They adopted the same procedure as Tesfaye and Ruach (Citation2019), and they identified that households consumed mainly food items of maize products (such as white porridge, white bread, “injera,” and whole roasted, white’ kitaa’), wheat products (such as bread and “kitaa”), and teff products (such as “injera” and porriage). In addition, they identified vegetables such as onion, cabbage, tomato, and green pepper, as well as livestock and poultry products such as milk, meat, egg, cheese, and butter are food items consumed by the households. They used 276 sampled households. The resulting analysis showed that 53.62% of the sampled households were found to be food insecure. Since the study area is dry land; severe climatic conditions resulted in more than half of the households being food insecure.

2.5. Interventions to alleviate food insecurity

According to Awulachew et al. (Citation2010), Ethiopia has a great groundwater potential which varies from 2.6 to 13.5 billion m3 per year. Therefore, the government of Ethiopia, in collaboration with other partners, should give concentrations on the utilization of underground water as an alternative source to strengthen irrigation activities and improve the production of food items locally. Since mobility is common in drought-prone areas, the government has to encourage them to be settled and produce different food items by presenting seeds and other farming materials either as subsidies or in discounts. Additionally, strengthening microfinance institutions' service delivery, improving infrastructures, and establishing local food complexes (factories) are also important actions to reduce food insecurity.

3. Conclusion and recommendation

This work has thoroughly reviewed the assessment food insecurity status of households,’ focused on dryland areas of Ethiopia. In drought-prone areas of Ethiopia, drought, recurring food shortage, and famine are great challenges faced by people. A high incidence of poverty and an alarming degree of food insecurity are the features of households in the dryland areas. The main determinants of poverty mainly in the dryland area of Ethiopia are limited resources, low incomes, a low level of human and social capital, as well as limited access to markets and service institutions, including those for credit, extension, and plant protection (Ogato et al., Citation2009).

Ethiopia has experienced long periods of food insecurity. Among Sub-Saharan countries, Ethiopia is the worst of all regions in the prevalence of undernourishment and food insecurity. A large portion of the country’s population has been affected by chronic and transitory food insecurity. The severity is more in dryland areas of the region where chronic and acute food insecurity are prevalent. Food-insecure households in these dryland regions ranged from 5% to 44% of the households are due to internally displaced persons in conflict, drought risks, desert locus, the spread of corona varies, protracted impacts of past poor seasons, disease outbreaks, poor household income, cost of nutritious food and knowledge on nutritious. As a result, these regions have become heavily dependent on external food aid. This figure also will likely increase due to the spread of novel coronavirus (COVID-19) as travel restrictions and economic disruptions hinder peoples’ livelihoods and access to food.

The households and productive-aged members of the household should participate in different income-generating activities and diversify their livelihood strategies that help them to escape from a wider state of food insecurity and undernourishment. The government could reduce food insecurity by improving groundwater use and helping to develop irrigated agricultural systems. In addition, the international non-governmental organizations, local organizations, private sector, and government should continue to work together on providing better seeds, conservation of the natural resource base for food production, improvement in research and extension, upgrading of rural infrastructure, improved market access, and special provision for people in particular need to reduce food insecurity.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Dagninet Asrat

Dagninet Asrat is a full-time lecturer in the Department of Agribusiness and Value Chain Management at Samara University, Ethiopia, and has MSc. in Agricultural Economics from Bahirdar University, Ethiopia. He has taught several courses for agribusiness and value chain management, agricultural economics, natural-resource economics and management, and rural development students. And, he also has engaged in the supervision of research projects for the students in the same department. His research interests focus on conducting research challenges and the impact of the different technological interventions on climate smart agriculture, the status of food security, value chain, market chain, etc., with the particular inclination to the Sub-Saharan Africa.

References

- Abule, E., Snyman, H. A., & Smit, G. N. (2005). Comparisons of pastoralists’ perceptions about rangeland resource utilization in the Middle Awash Valley of Ethiopia. Journal of Environmental Management, 75(1), 21–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2004.11.003

- AFSH. (2014). Undernourishment Multiple Indicators: Time lag for verifiable comparable information across countries 12 to 18 months, 2014.

- Agidew, A. M. A., & Singh, K. N. (2018). Determinants of food insecurity in the rural farm households in South Wollo Zone of Ethiopia: The case of the Teleyayen sub -watershed. Agricultural and Food Economics, 6(1), 10.

- Al, W., Orking, G., & Clima, O. (2008). Climate change and food security: A framework document. FAO Rome.

- Amwata, A. D. (2004). Effects of communal and individual land tenure systems on land use and food security in Kajiado District, Kenya [Doctoral dissertation]. University of Nairobi.

- Awulachew, S. B., Erkossa, T., & Namara, R. E. 2010. Irrigation potential in Ethiopia; Constraints and opportunities for enhancing the system. IWMI, 59.

- Bedemo, A., Getnet, K., Kassa, B., & Chaurasia, S. P. R. (2014). The role of rural labor market in reducing poverty in West Ethiopia. Journal of Development and Agricultural Economics, 6(7), 299–308. https://doi.org/10.5897/JDAE2013.0518

- Bezu, D. C. (2018). A review of factors affecting food security situation of Ethiopia: From the perspectives of FAD, economic and political economy theories.

- Burchi, F., Scarlato, M., & d’Agostino, G. (2018). Addressing food insecurity in sub‐Saharan Africa: The role of cash transfers. Poverty & Public Policy, 10(4), 564–589. https://doi.org/10.1002/pop4.233

- Dominguez, A. (2010). Why was there still malnutrition in Ethiopia in 2008? Causes and humanitarian accountability. Journal of Humanitarian Affairs. http://sites.tufts.edu/jha/archives/640

- Dube, A. K., Fawole, W. O., Govindasamy, R., & ÖZKAN, B. (2019). Agricultural development led industrialization in Ethiopia: Structural break analysis. International Journal of Agriculture Forestry and Life Sciences, 3(1), 193–201.

- Family Early Warning Systems Network [FEWS NET] and World Food Program [WFP]. (2020). Ethiopia food security outlook. Retrieved May, 2020, from https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/fies/resources/ETHIOPIA_Food_Security_Outlook_February%202020_Final.pdf

- FAO. (2005). Assessment of the world food security situation. Committee on World Food Security, Thirty-First Session, May 23–26, 2005. Food and Agricultural Organization.

- FAO. (2008). Food and agriculture organisation of the United Nations. Retrieved form https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=FAO%2C2008&btnG

- FAO. (2014). The state of food insecurity in the world 2014. Strengthening the enabling environment for food security and nutrition. Food and Agriculture Organization. http://www.fao.org/3/a-i4030e.pdf

- FAO. (2018). Pastoralism in Africa’s dry lands; reducing risks, addressing vulnerability and enhancing resilience. Retrieved June, 2020, from http://www.fao.org/3/CA1312EN/ca1312en.pdf

- FAO, I., & UNICEF. (2015). WFP. The state of food insecurity in the world, 46.

- Feleke, A. (2019). Determinants of household food security in Doyogena woreda, Kambata Tembaro Zone, South Nation Nationalities and People Regional State, Ethiopia. Pacific International Journal, 2(1), 13–25.

- Food Security Information Network [FSIN]. (2020). Global report on food crises. Retrieved march, 2020, from https://www.sadc.int/files/8415/8818/9448/GRFC_2020_ONLINE.pdf

- Gebremichael, B., & Asfaw, A. (2019). Advances in Public Health, Eastern Ethiopia. Advances in Public Health. doi:10.1155/2019/1472487

- Giday, K., Debebe, F., Raj, A. J., & Gebremeskel, D. (2019). Studies on farmland woody species diversity and their socioeconomic importance in Northwestern Ethiopia. Tropical Plant Research, 6(2), 241–249. https://doi.org/10.22271/tpr.2019.v6.i2.34

- Integrated Food Security Phase Classification [IPC]. (2020). Acute food insecurity analysis. World food program (WFP). Retrieved June, 2020, from http://www.ipcinfo.org/fileadmin/user_upload/ipcinfo/docs/IPC_Ethiopia_AcuteFoodSec_2019July2020June.pdf

- Jones, A. D., Ngure, F. M., Pelto, G., & Young, S. L. (2013). What are we assessing when we measure food security? A compendium and review of current metrics. Advances in Nutrition, 4(5), 481–505. https://doi.org/10.3945/an.113.004119

- Kahsay, S. T., Reda, G. K., & Hailu, A. M. (2020). Food security status and its determinants in pastoral and agro-pastoral districts of Afar regional state, Ethiopia. African Journal of Science, Technology, Innovation and Development, 12(4), 333–341. https://doi.org/10.1080/20421338.2019.1640429

- Marion, N. (2011). Towards a food insecurity multidimensional index. Master in Human Development and Food Security, 1-72. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Towards-aFood-Insecurity-Multidimensional-Index-(NapoliMuro/e37dad6f2c3e6d3f159ab68e6c7867b3ea3034ad

- MoARD. (2009), Ethiopian food security program (2010–2014). Retrieved June, 2020, from http://extwprlegs1.fao.org/docs/pdf/eth144896.pdf

- Mohamed, A. A. (2017). Food security situation in Ethiopia: A review study. International Journal of Health Economics and Policy, 2(3), 86–96.

- Nkunzimana, T., Custodio, E., Thomas, A. C., Tefera, N., Perez Hoyos, A., & Kayitakire, F. (2016). Global analysis of food and nutrition security situation in food crisis hotspots; EUR 27879. https://doi.org/10.2788/669159

- Nyariki, D. M., & Wiggins, S. (1999). Livestock as capital and a tool for ex-ante and ex-post management of food insecurity in semi-traditional agro pastoral societies: An example from Southeast Kenya. Social Sciences, 3(3), 117–126.

- Ogato, G. S., Boon, E. K., & Subramani, J. (2009). Improving access to productive resources and agricultural services through gender empowerment: A case study of three rural communities in Ambo District, Ethiopia. Journal of Human Ecology, 27(2), 85–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/09709274.2009.11906196

- Sani, S., & Kemaw, B. (2017). Assessment of households’ food security situation in Ethiopia: An empirical synthesis. Developing Country Studies, 7(12), 30–37.

- Sani, S., & Kemaw, B. (2019). Analysis of households’ food insecurity and its coping mechanisms in Western Ethiopia. Agricultural and Food Economics, 7(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40100-019-0124-x

- Tesfaye, L., & Ruach, B. J. (2019). Food insecurity and coping strategies among agro pastoral households: The Case of Lare Woreda, Nuer Zone, Gambella Regional State of Ethiopia. The Journal of Agriculture and Natural Resources Sciences. http://www.journals.wsrpublishing.com/index.php/tjanrs

- Thornton, P. K., van de Steeg, J., Notenbaert, A., & Herrero, M. (2009). The impacts of climate change on livestock and livestock systems in developing countries: A review of what we know and what we need to know. Agricultural Systems, 101(3), 113–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2009.05.002

- Urama, K. C., & Ozor, N. (2010). Impacts of climate change on water resources in Africa: The role of adaptation. African Technology Policy Studies Network, 29, 1–29.

- US Department of Agriculture. (2019). Definitions of food security. USDA. https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-theus/definitions-of-food-security.aspx

- Webb, P., Von Braun, J., & Yohannes, Y. (1994). Famine in Ethiopia: Policy implications of coping failure at national and household levels. Food and Nutrition Bulletin, 15(1), 1–2. https://doi.org/10.1177/156482659401500107