Abstract

Agricultural extension is the primary mechanism that enhances agricultural production. Thus, the main objective of this paper was to review the Ethiopian Agricultural Extension Services. The literature review was used to collect the data across Ethiopia. This method collected and evaluated the published documents that relate to agricultural extension in the country. The evaluation of various studies showed that agricultural extension contributes to improving farming, improving commercialisation, educating farmers, conserving natural resources, promoting new technology, promoting sustainable agriculture, and disseminating information across various settings. By the same token, weak interaction, low participation, lack of technical skills, missed use of services, the weak link of research extension, a lack of incentives, and a lack of suitable adaptation to technologies constrain the extension system across the country. Likewise, the available agricultural inputs, high demand for agricultural products, available donors, and access to weather roads and media, access to credit, and available manpower were the main prospects of the extension system in Ethiopia. Therefore, the government of Ethiopia needs to resolve the constraints of extension services, while using its prospects in order to improve the agricultural sector.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Agricultural extension services are the only appropriate option to be used to change the living standard of rural households across the country. Those services are capable of boosting the economy of the country thereby strengthening the agricultural production, reducing food insecurity, increasing consumptions, and promoting rural youth employment opportunities. However, the usage, coverage and the policies of extension services are not well aware. The services are not intended to appropriate beneficiaries and targeted areas. Then, both the rural people and administration unexploited the benefits of agricultural extension services across the Ethiopia. Accordingly, the policies should be set and carried out to the direct target populations or locations in order to increase the agricultural production in Ethiopia.

1. Introduction

In Ethiopia, the agricultural extension system was started in the imperial regime and has been applied across different areas of knowledge systems (Biratu, Citation2008). The extension system is established at different levels in the country. It functions at federal, regional, zonal, district, kebele, development agents, and household members (Waktole, Citation2020). The advisory service for the country focuses on many issues. It deals with the governance structures, sector development, capacity building, management, and the methods of utilizing services (Tewodaj et al., Citation2009).

Hence, as it is well acknowledged (Anaeto et al., Citation2012), Extension advisory services play a critical part in the agricultural sector’s growth and development. Agricultural extension is employed to help farmers improve their ability to adopt and implement new methods and share information about new technologies (Aregawi, Citation2017). Agricultural Extensions contribute to agricultural development by assisting and facilitating those who work in agriculture. Agricultural Extension Services are often concerned with the provision of agricultural technologies or inputs in order to increase agricultural productivity (Tariku et al. Citation2021). Agricultural extension and advisory services address the challenges of production system sustainability as well as the quality of life and rural livelihoods (Nwafor, Citation2020).

Conversely, due to socio-economic developments and agricultural sector reforms, public extension services in developing countries have faced some obstacles in the previous decade (Biratu, Citation2008). An extension mission is difficult in comparison to working with animals and plants in secure and pleasant research facilities, and this is because it works with illiterate, rural poor people with the goal of positively influencing their behavior (Qamar, Citation2005). Past extension techniques in Ethiopia have been developed and implemented from the top down, without the participation of the people for whom they were designed (Belay, Citation2003). While the number of extension workers in many sections of the country is quite low, those that do exist lack qualifications and communication skills (Belay and Abebaw, Citation2004).

However, there have been insufficient studies on the mixed perspectives of extension services in Ethiopia. Previously, some studies were conducted on the evaluation of challenges and opportunities for extension (Asfaw, Citation2018; Tilahun, Citation2018). On the other hand, Waktole (Citation2020) investigated the role of extension and its challenges as well.On the contrary, Alemayehu and Marta (Citation2018) examined the evolution of extension services approach in Ethiopia. Nevertheless, those studies have failed to come up with the constraints, prospects, and contributions of agricultural extension services in the country. Likewise, some of those investigations were carried out at local levels. Due to that gap, this study was carried out across the country with the combined perspectives. Thus, the specific objectives of this article are:

To examine the contributions of agricultural extension services

To explore the constraints of agricultural extension services

To review the prospects of agricultural extension services

With this motivation, this article can make many contributions to knowledge across Ethiopia. It can provide knowledge to extension agents working in the farm fields. Similarly, it is a precondition for extension service delivery in rural settings. By the same token, it can be significant for the development of the agricultural sector through increasing production. Furthermore, it can be demonstrated to be an insight for new development interventions all over the world. In conclusion, it can be a source of empirical findings for many studies.

2. Research methodology

2.1. Description of the study area

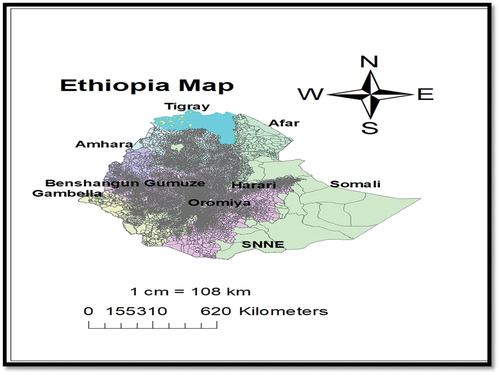

Ethiopia is a country in the Horn of Africa (Figure ). It is bordered on the north by Eritrea; on the east by Djibouti and Somalia; on the west by Sudan and South Sudan; on the south by Kenya. Ethiopia has a high central plateau with elevations ranging from 1,290 to 3,000 meters (4,232 to 9,843 feet), with the highest peak reaching 4,533 meters (14,872 ft.). Ethiopia is Africa’s second most populated country, with an estimated 80 million people living on a land area of 1.1 km2.

Ethiopia’s climate, as well as that of its neighboring countries, varies widely. The agro ecology of highland Ethiopia is temperate, whereas the lowlands are hot. The country is entirely within the tropics, although the elevation of the land compensates for its proximity to the equator. The temperature in Addis Ababa ranges from 2,200 to 2,600 meters (7,218 to 8,530 feet), with a maximum of 26 degrees Celsius (78.8 degrees Fahrenheit) and a minimum of 4 degrees Celsius (39.2 degrees Fahrenheit).

2.2. Data collection and methods of analysis

The main aim of this article is to review the Ethiopian’s perspectives towards agricultural extension services. The data of this article was accessed through literature review. The paper collected the secondary data from various studies in Ethiopia. The secondhand information was collected from the existing papers concerning about the contributions, constraints, and the prospects of agricultural extension across the country. Thus, the main sources of this article were journal articles, conference proceedings, theses, and the reports of the government and NGOs.

As a result, about 37 papers were used for evaluations. Based on the subjects, the times and the locations of the studies; these papers were found appropriate for the explanation of this article. So, the data from those articles were strongly criticized in order to get the better findings. Meanwhile, there are many methods involved in analysis of the data collected from the published works. The data was explored by thematic based methods, and comprehension method.

3. Results and discussions

3.1. The concepts and definitions

3.1.1. Agriculture

Agriculture is the general term used to describe many ways in which plants and domestic animals provide food and other items to the world’s human population. Hence, to minimize misinterpretations, several agricultural terms must be clarified (Harris & Fuller, Citation2014). Agriculture is derived from the Latin words ager (field) and colo (cultivate), which together denote the Latin agricultural field or land tillage (Harris & Fuller, Citation2014). This implies that agriculture is cultivation of crops and rearing of animals.

3.1.2. Agricultural extension

Agricultural extension is a multifaceted concept that covers a varied range of undertakings (Van Assche, Citation2016. In its conception, agricultural extension is a practice of countryside collective teaching that takes place in rural areas. It is also an informal educational approach aimed toward the rural community in order to assist them in resolving their issues. The agricultural extension can be described as the full range of organizations that assist individuals in participating in agricultural production in order to solve challenges. Further, agricultural extension has lately been characterized as systems that help farmers improve their technical, organizational, and management skills (Christoplos, Citation2010).

3.1.3. Agricultural extension services

To different people, the agricultural extension service has meant different things. It is defined as a government and non-governmental organization’s intervention in farming households. It can also be defined as the production of information, knowledge, and skills that can help boost the adoption of improved agricultural technologies (Berhanu & Hoekstra, Citation2006). It is a method of transferring technology, increasing adult learning in rural areas, assisting farmers in problem solving, and increasing their interest in agriculture (Christoplos & Kidd, Citation2000).

3.2. Agricultural extension services in Ethiopia

Extension services initiatives have historically supported the adoption of technologies in Ethiopia (Alexander & Marco, Citation2020). At least 50 years have passed since the extension’s inception in the country (Biratu, Citation2008). The imperial regime was most likely in place when Ethiopia’s agricultural expansion began. The Ambo Agricultural School was founded in 1931 (Waktole, Citation2020), the Ministry of Agriculture was established in 1943 (EEA, Citation2006a), and the Imperial Ethiopian College of Agriculture and Mechanical Art was founded in 1950. (Belay, Citation2002). The requirement for high-level workforce training, agricultural extension promotion, and distribution of research output and scientific knowledge served as the foundation for the start of actual agricultural extension (Abesha et al., Citation2000).

The most effective and crucial strategy for reaching rural households is an agricultural extension (Aregawi, Citation2017). So, the expansion might be a technique for achieving Ethiopia’s Millennium Development Goal of reducing severe poverty and famine (Biratu, Citation2008). Agricultural extension services that are efficient, thorough, need-based, and participative play a significant role in raising the income and welfare of rural households (Tariku et al. Citation2021). As a result, efforts have been undertaken to offer farmers agricultural extension services through the supply of input subsidies, farmers’ training, and the provision of advice services (Aregawi, Citation2017; Tewodaj et al., Citation2009). Expanding agricultural extension services is therefore highly prioritized, leading to an increase in agricultural productivity (Aregawi, Citation2017).

There is a reputation for the extension efforts as being essentially unsuccessful in rural areas (Gautam, Citation2000). Regarding the Ethiopian agricultural system’s ability to bring about the desired change in the nation’s rural communities, more has been said than done practically in rural areas (EEA, Citation2006a). There is virtually little participation in the adoption of modern agricultural technology and information from farmers (Aregawi, Citation2017). It is due to the strong standardization of extension programs as a result of top-down public service delivery that doesn’t prioritize farmers’ requirements (Tewodaj et al., Citation2009). The viewpoints of the farmers were not given enough attention when creating the extension programs and policies at the local level (Belay, Citation2002). Periodically, the sector’s performance is declining, leaving farmers with fewer products from their farming operations (Aregawi, Citation2017; Biratu, Citation2008).

3.3. The review findings

3.3.1. The contributions of agricultural extension services

3.3.1.1. Improve farming

Extension programs help farmers in Ethiopia to produce more food in a variety of contexts. High agricultural yields are experienced due to extension services. The extension service helps farmers increase their produce (Aregawi, Citation2017; Tigist et al., Citation2018a; Waktole, Citation2020). This means that extension services help farmers boost their yields. Despite this, the study failed to show how extension services in Ethiopia help farmers boost their yields. Furthermore, extension services boost land productivity (Biratu, Citation2008; Benefit Realize, Citation2020). To increase land production, the extension provides a variety of organic and inorganic fertilizers. These fertilizers can then be used to boost farm production across the country. Nonetheless, this research lacked significant evidence regarding the amount of fertilizer to be used at the time of application. In this finding, the types of fertilizers to be used to boost fertility are not yet well-defined.

3.3.1.2. Improve commercialization

The fundamental goal of extension services is to improve the commercialization of farm products. As such, extension services help to improve the commercialization of agricultural products. It meets the demands of many parties in relation to the sale of agricultural products. Market orientation is aided by the extension system (Waktole, Citation2020; Asfaw, Citation2018). As a result of the extension system, farm owners’ behavior shifts from basic consumption to market firmness. This finding is criticized for the lack of presentation of how farm products are marketed. In addition, the extension also facilitates commercialization (Teka et al. Citation2019). It provides different kinds of awareness training about the importance of commercializing agricultural products. Nevertheless, this study was criticized for its vague methods of facilitating commercialization.

3.3.1.3. Conserve natural resources

Natural resources are a vital foundation for agricultural production and environmental protection. The extension services currently emphasize the safeguarding of natural resources in Ethiopia. The Extension System provides education on conserving natural resources (Asfaw, Citation2018; Gerba, Citation2018; Waktole, Citation2020). This means that the extension organizes training about natural resource conservation. However, these studies have not indicated the kinds of natural resources that should be given more concentration in the context of Ethiopia. By the same token, the extension enhances the rehabilitation and conservation of natural resources (Benefit Realize, Citation2020). This supports the regaining of nature’s lost beauty and protects the remaining resources. The lack of resources to be rehabilitated and protected is not clearly addressed in this study.

3.3.1.4. Disseminate information

Information dissemination is the main aim of the extension system in farming areas. The extension services disseminate information to solve the problems of farmers in the farm fields. Some of the studies indicated that the extension system disseminates information to farmers (Waktole, Citation2020; Teka et al. Citation2019). The system transfers information relating to agricultural activities. However, the forms of agricultural information disseminated to farmers were not clear from these studies. And then, the extension system disseminates useful information to the farmers (Asfaw, Citation2018). It provides information when it is needed urgently. For example, during pest outbreaks, heavy wind, rain, and conflict the extension transfer various coping mechanisms to farmers. But the kind of information that was disseminated is not justified.

3.3.1.5. Promote sustainable agricultures

The extension services contribute to sustainable agriculture production in Ethiopia. The extension system initiates the sustainable production of agriculture. Previous studies showed that extension services promote sustainable farming (Waktole, Citation2020; Teka et al., Citation2019). It supports the use of environmentally friendly technology during farming. It also encourages an economically viable production system across various locations. But how sustainability can be applied in the farming system was not clarified by these studies. Furthermore, the extension system can help sustain farming (Asfaw, Citation2018). It is supposed to contribute to maintainable farming, thereby establishing interventions in rural areas. Even though that finding is useful, it lacks a clear picture of how agriculture is sustained across the country.

3.3.1.6. Educate farmers

The extension services provide informal education to farmers worldwide. It promotes the use of adult education, which has the potential to shape the attitudes and living conditions of farmers in rural areas. Some studies have shown that the extension system provides training to the farmers in the country (Aregawi, Citation2017; Biratu, Citation2008). This indicates that various capacity-building training programs were given to the farmers in Ethiopia. Still, how the farmers were trained is not found in these studies. In the same way, the extension system teaches farmers about technological utilization (Asfaw, Citation2018; Gerba, Girma, Till, Anna et al., Citation2017a). This demonstrates that the extension system teaches farmers, to utilize adult education across the country. The system set up the farmers’ training center in all administrative units, or menders. Regardless of that, the study failed to indicate the number of farmers who got training across the study areas.

3.3.1.7. Promote technologies

The extension services contribute to the promotion of farming technologies to farmers. The extension system encourages farmers to adopt new technologies in order to increase yields. The extension system helps some of these technologies be distributed to farmers (Waktole, Citation2020; Aregawi, Citation2017). Sometimes, the technologies may be supplied freely without any expectation of cost on the part of the farmers. This could be to increase their motivation for new technologies. However, this study lacks the types of new technologies being distributed freely in the country. Besides, the extension system promotes technologies (Gerba, Girma, Till, Anna et al., Citation2017a; Guush et al., Citation2018). It brings food packages to the farmers. Depending on the nature of the technology, this may be free or at a cost. And yet, there is a limit on methods of promoting new technologies to farmers.

3.3.2. The constraints of agricultural extension services

3.3.2.1. Weak interaction

There is a weak connection between extension agents and farmers in the extension system. The farmers and extension agents work individually on numerous agricultural activities. It was shown that there was poor interaction between farmers and extension agents across the country (Tewodaj et al., Citation2009; Tigist et al. Citation2018a). This shows that there is a partial bond between extension agents and farmers in Ethiopia. Nonetheless, the causes of poor interaction were not indicated in this study. Moreover, there is low contact between extension agents and farmers (Tilahun, Citation2018). This indicates that there is a lack of trust between the extension workers and farmers. There is also a weak advisory service to farmers from extension workers (Gerba, Citation2018). The extension agents don’t offer advisory services to the farmers in Ethiopia. However, the advisory services that the Extension System lacks are not specified.

3.3.2.2. Low participation

The lack of farmers’ involvement in extension activities contributes to the low level of agricultural production in Ethiopia. This low participation couldn’t consider the needs of all extension stakeholders. Farmers’ participation in extension work involved in agricultural extension in Ethiopia is low, according to previous studies (Tesfa, Citation2008; Aregawi, Citation2017; Asfaw, Citation2018; Waktole, Citation2020; Tariku et al. Citation2021). The level and types of participation that extended to extension, on the other hand, were not discovered. By the same token, tough centralization is used by the extension system in the design phases (Berhanu & Hoekstra, Citation2006; Gerba, Citation2018). It uses a top-down approach in order to deliver and design the extension services. This finding concentrated mainly on planning, leaving out monitoring, implementation, and evaluation. Furthermore, it is regarded as supply-driven (Tigist et al. Citation2018b), and it is an unsatisfied extension service (Guush et al., Citation2018). And still, this study did not take into account the needs and demands of the farmers.

3.3.2.3. Deficiency of technical skills

The lack of technical skills among extension agents is a critical limitation in extension work. It discourages farmers from not adopting the new agricultural extension services in Ethiopia. There are limited skills for extension workers (Berhanu & Hoekstra, Citation2006; Gerba, Citation2018; Waktole, Citation2020). This indicates that the extension agents have a dearth of knowledge, skills, and capability to pursue the extension activities. They are usually waiting for the supervisors and regional/federal extension specialists to perform the tasks. Nonetheless, the specific skills lacking among extension workers were neglected. In addition, there is a lack of qualified extension workers in the agricultural field (Asfaw, Citation2018; Guush et al., Citation2018). Most of the extension workers were not qualified for the assigned work. They work in unrelated fields across the country. However, the nature of classifying people and qualifications is not specified.

3.3.2.4. Missed use of services

There is an absence of the right application of agricultural-related extension services. In this country, many of the extension services do not reach the correct beneficiaries at suitable sites. At the time of operation, the extension interventions are changed to other locations and target populations. Accordingly, some of the studies show that people in the country are underutilizing dissemination technologies (Gerba, Citation2018; Waktole, Citation2020). This implies that there is poor implementation of extension services for the targeted households. But how and why people don’t use technology is not indicated. Furthermore, the services of Extension are full of bias (Alemayehu & Marta, Citation2018; Asfaw, Citation2018; Tigist et al. Citation2018a). As usual, the extension services are gender-biased. It is dominated by men’s outlooks. Similarly, the extension method focuses on selected potential locations. It doesn’t consider the pastoral and lowland areas of the country. This finding lacks the severity of bias because it is gender, sex, age, and location segregated.

3.3.2.5. Weak link of research-extension

The poor relationship between research and extension is a common constraint in the extension system. According to previous studies, there is a poor relationship between research and extension (Belay, Citation2002; Tesfa, Citation2008; Tewodaj et al., Citation2009; Asfaw, Citation2018; Belay & Dawit, Citation2017; Gerba, Citation2018; Guush et al., Citation2018; Tilahun, Citation2018; Teka et al. Citation2019). In Ethiopia, the poor linkage of research extension leads to supply-driven extension services. However, the causes of poor relationships are missed by this study. In addition, there is poor feedback (Tigist, Kavitha, Haimanot, Mohammed et al., Citation2018b). The communication between the extension and the research is linear in nature. From each, there is a lack of regular feedback on information in the country. Still, the time and the message lacking feedback are not clarified in this study.

3.3.2.6. Lack of incentives

The scarcity of incentives is a danger to extension services. It reduces the inspiration of extension agents towards extension services. The study indicated that the lack of various services for extension agents is the biggest limitation in extension (Waktole, Citation2020). For example, some of the studies showed that there is a lack of incentive in the extension system (Gerba, Citation2018; Guush et al., Citation2018; Teka et al. Citation2019). The incentives for agricultural development agents were ignored in Ethiopia. But incentives that were needed were not found in these studies. Meanwhile, there is a shortage of financial motivation (Asfaw, Citation2018; Tesfa, Citation2008; Teka et al., Citation2019). The government of Ethiopia makes the salaries of extension agents the lowest among the other development experts, particularly health and educational employees.

3.3.2.7. Lack of suitable adaptation to technologies

The lack of adaptation to appropriate agricultural-related technologies is a constraint in the extension system. The lack of acclimatizing to the proper technologies doesn’t meet the demands of the local people. According to studies, the inability to adapt to new technology is a major limitation of extension services (Asfaw, Citation2018; Waktole, Citation2020). The technologies are not adjusted based on the locations. Equally, there are insufficient technologies in the extension system. Disseminated technologies do not reach everyone. At the same time, there are low gendered technology adoption rates (Catherine et al., Citation2013). Men and women are not considered equal. There is ignorance of women’s interests and demands in extension technologies.

3.3.3. The prospects of agricultural extension services

3.3.3.1. Available agricultural inputs

Access to farming inputs is a problem for farm production around the world. It makes the farming system more productive. For instance, increasing access to agricultural inputs helps farmers boost production (Gerba, Girma, Till, Anna et al., Citation2017a). This addresses the needs and demands of the farmers in agricultural extension. However, no figures for increased agricultural yields are provided. The presence of arable land, bodies of water and good weather conditions provide an opportunity for extension services (Waktole, Citation2020). This suggests that the country’s sufficient water bodies, land, and weather conditions lead to the best extension services in the country. These basic inputs of agricultural production are the starting points for the successful design of new technologies or extension services in the country. Still, the extension services to be supplied in relation to available inputs were not shown.

3.3.3.2. High demands of products

The high demand for agricultural products is an opportunity for extension services. It increases the production of the agricultural sector and its products. One of the studies showed that there is high agricultural market demand (Gerba, Citation2018). It implies that many people are consuming agricultural products. But this study lacks the kinds of agricultural products demanded by the market. On the other hand, market demand provides the opportunity for the development of agriculture (Gerba, Girma, Till, Anna et al., Citation2017a). This connects the increase in people’s demands to the development of the agricultural sector. When people understand that their products are highly needed by the market, they produce more on their farms. This can in turn increase the development of the agricultural sector. Nevertheless, there is no clear linkage shown in this study.

3.3.3.3. Available manpower

The increasing manpower is an opportunity for the extension system in Ethiopia. It supports the agricultural sector’s development. The study revealed that there is access to capable manpower that boosts agriculture production (Gerba, Citation2018). The criteria for accessible manpower are not clear. Subsequently, there are an increasing number of development agents in agricultural fields (Abate, Citation2007; Gerba, Girma, Till, Anna et al., Citation2017a). This implies that the growing number of development agents improves agricultural production. It also increases the extension coverage in terms of farmers and locations. However, these studies did not provide the minimum and maximum numbers of workers. Furthermore, the readiness and motivation of many farmers to adopt the new technology is an opportunity (Gerba, Girma, Till, Anna et al., Citation2017a). This indicates that the presence of many farmers involved in agriculture is an opportunity in the extension system. In this study, there are drawbacks to justifying the level and kind of motivation.

3.3.3.4. Financial access

Access to credit services is a prospect for agricultural extension in Ethiopia. The existing agricultural extension services support farmers’ access to financial services. Gerba, Girma, Till, Anna et al. (Citation2017a) found that numerous micro-financial traditions are emerging to provide credit services to farmers in cash and in kind. The system distributes funds to selected farmers in specific areas of the country. This finding lacks the types of services provided by micro-financial institutions. Likewise, there is an allocation of seed money to scale up the adoption of new technologies (Gerba, Girma, Till, Anna et al., Citation2017a). Some of the money is given to the group of people to purchase the particular technology. But it lacks the new technologies being focused on by seed money.

3.3.3.5. Available donors

The motivation of organizations to invest in agricultural extension is an opportunity for the development of agriculture. The support of international donors contributes to agricultural extension systems (Gerba, Girma, Till, Anna et al., Citation2017a). There are some organizations that are willing to support extension work in the country. Nevertheless, the names of supportive organizations or donors are not mentioned in the findings. OXFAM (Citation2016) indicated that some of the donors pay due attention to agricultural extension in Ethiopia. They are working day and night to change the lives of farmers. However, the status of the extension of pay is not justified. Gerba, Girma, Till, Anna et al. (Citation2017a) found that most of these donors focus on introducing productivity-enhancing food crop technologies in Ethiopia. In the meantime, there is a lack of the kinds of food crops supported by the donors.

3.3.3.6. Access to weather road and media

Access to infrastructure, particularly roads and mobile phones, is an opportunity for extension systems. The infrastructure links the smallholder farmers to the market and information. There is increasing access to weather-related road and communication services (Gerba, Girma, Till, Anna et al., Citation2017a). This means that the presence of roads and phones strengthens access to new technologies and information. However, how many kilometers a farmer can be classified as accessible is not specified in this finding. Currently, mobile phones help farmers call and access free devices for production technologies or agronomic practices (Agricultural Transformation Agency (ATA), Citation2014). This implies that the farmers can ask for the required information without moving to distant areas and paying fares. However, the recipients to whom the farmers communicate are not specified.

4. Conclusions

Agricultural extension is the primary mechanism that enhances agricultural production. The appraisal of different studies showed that the agricultural extensions have made a great contribution to the livelihoods of the farmers in Ethiopia. It discovered the various constraints of agricultural extension services across the country in the same way. This evaluation also found many prospects for agricultural extension services in Ethiopia.

Nevertheless, the critique of those findings was restricted by different limitations. The study has limitations due to its lack of specified target populations, locations, samples, and heavy dependency on secondary data. Accordingly, the government of Ethiopia needs to resolve the constraints of extension services while using its prospects in order to increase the contributions of extension services. Finally, there is a need for further studies on extension services in the country or region to obtain appropriate data.

Acknowledgements

The author acknowledged his coworkers, Gambella University and librarians.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Chayot Gatdet

Chayot Gatdet (M.Sc in Rural Livelihood and Food Security) is lecturer in Department of Rural Development and Agricultural Extension, and coordinator for University Industry Linkage and Technology Transfer at Gambella University. His research areas are livelihood, food security, agricultural extension, sustainable development and pastoralism. He has participated in many national research conferences and published seven journal articles and one book from 2021-2022.

References

- Abate, H. (2007). Review of extension systems applied in Ethiopia with special emphasis to the Participatory Demonstration and Training Extension System (PADETS).

- Abesha, D., Waktola, A., & Aune, J. B. (2000). Agricultural Extension in the Dry lands of Ethiopia. Report-Drylands Coordination Group (Norway).

- Agricultural Transformation Agency (ATA). (2014). Transforming Agriculture in Ethiopia. Annual Report.

- Alemayehu, A., & Marta, H. (2018). Historical evolution of agricultural extension service approach in Ethiopia - a review. Agricultural Extension Journal, 2 (4), 201–2102521 – 11. Review Article

- Alexander, J., & Marco, G. (2020). The pain of a new idea: Do late bloomers response to extension service in rural Ethiopia. Econ.EM.

- Anaeto, F. C., Asiabaka, C. C., Nnadi, F. N., Ajaero, J. O., Ugwoke, F. O., Ukpongson, M. U., & Onweagba, A. E. (2012). The role of extension officers and extension services in the development of agriculture in Nigeria. Wudpecker, Journal of Agriculture Research, 1 (6), 180–185. Nigeria

- Aregawi, B. (2017). The role of agricultural extension services on increasing food crop productivity of smallholder farmers in case of Atsbi Womberta Woreda, Eastern Tigray, and Ethiopia. Proceedings of the 11th Annual Student Research Forum,

- Asfaw, A. (2018). Review on role and challenges of agricultural extension service on farm productivity in Ethiopia. International Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension, 4(1), 093–100. www.premierpublishers.org

- Belay, K. (2002). Constraints to agricultural extension work in Ethiopia: The insiders’ view. South African Journal of Agricultural Extension, 31.

- Belay, K. (2003). Agricultural extension in Ethiopia: The case of participatory demonstration and training extension system. Journal of Social Development in Africa, 18(1), 49–83. https://doi.org/10.4314/jsda.v18i1.23819

- Belay, K., & Abebaw, D. (2004). Challenges facing agricultural extension agents: A case study from south-western Ethiopia. African Development Bank, P(1), 139–168. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8268.2004.00087.x

- Belay, K., & Dawit, A. (2017). Agricultural research and extension linkages: Challenges and intervention options. Ethiopian Journal of Agricultural Sciences, 27(1), 55–76.

- Benefit Realize (BR). (2020). Agricultural extension service in Ethiopia: Achievements and challenges and case study on Customized extension.

- Berhanu, G., & Hoekstra, D. (2006). Commercialization of Ethiopian agriculture: Extension service from input supplier to knowledge broker and facilitator. IPMS (Improving Productivity and Market Success) of Ethiopian farmers project working paper 1. ILRI (International Livestock Research Institute), Nairobi, Kenya.

- Biratu, G. (2008). Agricultural extension and its impact on food crop diversity and the livelihood of farmers in guduru, eastern wollega, Ethiopia. A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Science in Management of Natural Resources and Sustainable Agriculture (MNRSA). Norwegian University of Life Sciences (UMB), Norway.

- Catherine, R., Guush, B., Fanaye, T., & Alemayehu, S. (2013). Quality matters and not quantity: Evidence on productivity impacts of extension service provision in Ethiopia. Selected Paper prepared for presentation at the Agricultural & Applied Economics Association’s 2013 AAEA & CAES Joint Annual Meeting, Washington, DC: Publisher is International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI).

- Christoplos, I. (2010). Mobilizing the potential of rural and agricultural extension. Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations and global forum for rural advisory services. FAO.

- Christoplos, I., & Kidd, A. (2000) Guide for monitoring, evaluation and joint analysis of pluralistic extension support. Neuchâtel group and Swiss Centre for agricultural extension and rural development. http://www.neuchatelinitiative.net

- EEA. (2006a). Evaluation of the Ethiopian agricultural extension with particular emphasis on the participatory demonstration and training extension system (PADETS). In Ethiopian Economic association/Ethiopian Economic Policy research Institute. Addis Ababa.

- FAO. (2019). Agricultural extension manual for extension workers. Strengthening the capacity of Farmers Associations to increase production and marketing of root crops, fruits and vegetables in FSM.

- Gautam, M. (2000). Agricultural extension: The Kenya experience: An impact evaluation. Operations evaluation studies. World Bank.

- Gerba, L. (2018). The Ethiopian Agricultural Extension System and Its Role as a Development Actor: Cases from Southwestern Ethiopia. PhD Dissertation University of Bonn.

- Gerba, L., Girma, K., Till, S., & Anna, H. (2017a). The agricultural extension system in Ethiopia: Operational setup, challenges and opportunities. Working Paper 158. ZEF Working Paper Series, 1864-6638 Center for Development Research, University of Bonn.

- Gerba, L., Girma, K., Till, S., & Anna, H. (2017b). The agricultural extension system in Ethiopia: Operational setup, challenges and opportunities. Working Paper 158. ZEF Working Paper Series, 1864-6638 Center for Development Research, University of Bonn.

- Guush, B., Catherine, R., Gashaw, T., & Thomas, W. (2018). The state of agricultural extension services in Ethiopia and their contribution to agricultural productivity. Strategy Support Program. Working Paper 118. IFPRI.

- Harris, D. R., & Fuller, D. Q. (2014). Agriculture: Definition and Overview. In (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology (Claire Smith (pp. 104–113). Springer.

- Nwafor, C. (2020). A review of agricultural extension and advisory services in subSaharan African countries: Progress with private sector involvement. https://doi.org/10.20944/preprints202008.0294.v1

- OXFAM. (2016).El Niño in Ethiopia: Program observations on the impact of the Ethiopian drought and recommendation for action. OXFAME L Niño Briefings,I https://www.oxfam.org/sites/www.oxfam.org/files/file_attachments/bn-el-nino-ethiopia-240216-en.pdf

- Oxford English Dictionary. (1971). The Oxford English dictionary. Oxford University Press.

- Qamar, M. K. (2005). Modernizing national agricultural extension system: A practical guide for policy makers of developing countries. FAO, Research, Extension and Training Division.

- Tariku, K., Abrham, S., & Alemseged, G. (2021). Analysis of the status and determinants of rural households’ access to agricultural extension services: The case of Jimma Geneti Woreda, Oromia regional state, Ethiopia. International Journal of Agricultural Extension and Rural Development Studies, 8(1), 52–99.

- Teka, D., Mulugeta, G., & Alemayehu, A. (2019). Contributions and challenges in research and extension linkage for agricultural transformation in Ethiopia: A review. International Journal of Agricultural Extension, 2311–8547. http://www.escijournals.net/IJAE

- Tesfa, C. (2008). Assessment of problems of agricultural extension services in Ethiopia: The case of food crop extension package in Guto Gida Woreda, East Wollega Zone, Oromia National regional state. A thesis submitted to Addis Ababa University, College of Development Studies, in Partial Fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of masters of art in development studies (rural livelihood and development).

- Tewodaj, M., Marc, J., Regina, B., Mamusha, L., Josee, R., Fanaye, T., & Zelekawork, P. (2009). Agricultural Extension in Ethiopia through a Gender and Governance Lens Development Strategy and Governance Division, International Food Policy Research Institute – Ethiopia Strategy Support Program 2.

- Tigist, P., Kavitha, N., Haimanot, A., & Mohammed. (2018a). Agricultural extension: Challenges of extension service for rural poor and youth in Amhara Region, North Western Ethiopia. The case of North Gondar Zone. International Journal of Scientific Research and Management (IJSRM), 6. 57.47, (2016): 93.67. https://doi.org/10.18535/ijsrm/v6i2.ah02

- Tigist, P., Kavitha, N., Haimanot, A., & Mohammed. (2018b). Agricultural extension: Challenges of extension service for rural poor and youth in Amhara Region, North Western Ethiopia. The Case of North Gondar zone. International Journal of Scientific Research and Management (IJSRM), 6 (2), AH-2018-05–14. (e): 2321-3418 Index Copernicus value (2015): 57.47, (2016):93.67DOI: https://doi.org/10.18535/ijsrm/v6i2.ah02

- Tilahun, S. (2018). Review on Agriculture-industry linkage and technology adoption in Ethiopia: Challenges and opportunities. Tropical Drylands Volume 2, Number 1, E-, 25802828, 18–27. https://doi.org/10.13057/tropdrylands/t020104

- Van Assche, K. (2016). Afterwards: Expertise and rural development after the soviets. In A.-K. Hornidge, A. Shtaltovna, & C. Schetter (Eds.), Agricultural knowledge and knowledge systems in post-soviet societies (Vol. 15, pp. Peter Lang). Interdisciplinary Studies on Central and Eastern Europe.

- Waktole, B. (2020). Review on roles and challenges of agricultural extension system on growth of agricultural production in Ethiopia. Journal of Plant Sciences. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.jps.20200806.11