?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Maize is the main cereal crop that supports the livelihoods of millions of smallholder farmers in Africa. However, one of the main bottlenecks for maize production is low market penetration. This study examined the factors influencing the likelihood of smallholder farmers taking part in maize trading in southern Ethiopia using cross-sectional data collected from 360 smallholder maize growers. The data were examined with inferential statistics and the Heckman two-stage sample selection econometric model. Household head age and sex, maize price, household size, farm experience, market distance, access to transportation, frequency of extension contact, land size, amount of credit received, market information, and off-farm income were all found to be significant factors that determine maize farmers’ market participation. Investment in road infrastructure in maize production potential areas and access to market information is mainly needed to increase maize trading.

1. Introduction

Maize is the main cereal crop that supports the livelihoods of millions of smallholder farmers in Africa. The world’s top three maize-producing countries are the United States, China, and Brazil, which produce 347,048,000, 260,958,000, and 101,139,000, respectively, of the 1.1 billion tons of maize produced in the world (FAO, Citation2021). Ethiopia is also among the major maize-producing countries in the world, with 9,636,000 tons produced in 2019 (FAO, Citation2021). The mean maize yield in the Wolaita zone was 26.99/ha, which was smaller than the national mean of 33.87/ha (Cochrane and Bekele, Citation2018).

The main bottleneck for maize production is the low market penetration. As Alene et al. (Citation2008) reported, smallholder farmers in general, who account for 90% of agricultural production in Ethiopia, do not produce and sell their products and farming inputs in an organized manner, and part of their advantage may be transferred to middlemen. Similarly, as Abayneh and Tefera (Citation2013) indicated, the maize market in Ethiopia, similar to that of other agricultural products, was fragmented. As a result, millions of smallholders supply tiny amounts, which are then handled by small traders at various levels.

Household market participation is a critical tool for food security, poverty alleviation, and enhancing livelihoods in general for the vast majority of smallholder farmers in rural places. These places are trapped in a cycle of poverty characterized by low economic returns as a result of limited market participation, among other factors (Gebremedhin and Tegegne, Citation2012; Niankara and Traoret, Citation2019; Olwande and Mathenge, Citation2011; Vandenbroucke and Cantillon, Citation2014). Moreover, increased market involvement by the poor is crucial for breaking the cycle of traditional semi-subsistence farming and for lifting rural households out of poverty. Smallholders do not often participate in food crop markets due to subsistence production and the additional expenses associated with seeking requirements (World Bank, Citation2007).

Recent studies on smallholder maize farmers’ participation in the market system in East Africa by Changalima and Ismail (Citation2022), Galtsa et al. (Citation2022), Ismail (Citation2022), Gebre et al. (Citation2021), and Ismail and Changalima (Citation2019) indicated that input-output, demographic and socioeconomic factors such as transactional, transportation access, road conditions, market prices, access to market information, quality of maize seed, access to inputs, storage facilities, household size, and farm size, market distance, gender gap, education level, farming experience, the quantity of maize produced, cooperative membership, amount of credit received, non-farming income, lagged price, and livestock holding are significant factors that determine the participation of smallholder farmers in the maize market.

Earlier empirical maize studies in Ethiopia have mainly focused on the maize value chain (Abajobir et al., Citation2018; Abdul-Rahman and Donkoh, Citation2015; Erge et al., Citation2016; Giref, Citation2016; Rashid et al., Citation2019), determinants of increased maize technology adoption (Gecho and Punjabi, Citation2011; Milkias and Abdulahi, Citation2018; Zegeye et al., Citation2001) and factors determining maize production efficiency (Ahmed et al., Citation2018; Bealu et al., Citation2013; Degefa et al., Citation2017; Iticha, Citation2020). Data are scarce on variables influencing producer involvement in Ethiopia’s maize market. The studies by Galtsa et al. (Citation2022) and Haile et al. (Citation2022) addressed the concern using a double hurdle approach in Southern and Southwestern Ethiopia. However, these studies used different analytical approaches and were conducted in different production and marketing systems. The demographic and socioeconomic characteristics that affect farmers’ participation in maize while delivering the crop in both fresh and dried stages have not been explored, particularly in the Damot Pulassa district (the area with higher actual maize production potential in Wolaita Zone (Wolaita Zone Agriculture and Natural Resource Office (WZANRO), Citation(2019)). Understanding farmer market participation in this district is critical for increasing smallholder farmer income. Moreover, it will have a significant influence on decreasing the challenges of smallholder farmers in the Damot Pulasa area, southern Ethiopia, and other comparable settings in general. Therefore, the research aimed to investigate the demographic, socioeconomic and institutional factors determining the likelihood of smallholder farmers’ participation in maize trading in southern Ethiopia.

2. Methodology

2.1. Study area description

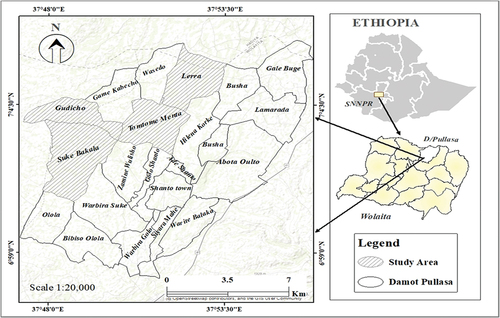

Damot pulasa is one of 22 districts in the Wolaita zone in the Southern Nations, Nationalities, and Peoples’ Regional State (SNNPR) in Ethiopia (Figure ). The district is situated at 1,734 masl. It is located at 7° 0‘59“north and 38° 21’ 22” east (see Figure ). The region is one of the Wolaita zone’s potential maize-producing areas.

2.2. Sampling methods and sample size

To choose sample respondents, a multistage sample selection procedure was adopted. The research district was chosen purposefully in the first stage based on the extent and potential of maize production (WZANRO, Citation(2019)). Secondly, the district was then divided into two zones: humid weinadega, which consists of 13 kebeles,Footnote1 and dry weinadega, which consists of 10 kebeles. In the third stage, using a simple random sample selection technique two kebeles from dry weinadega (mid-altitude), Lera and Tontome Menta, and two kebeles from humid weinadega, Gudicho, and Pullassa Bakala, were selected randomly due to homogeneity in maize production of all kebeles in this two agro-ecologies. The desired sample size of 360 was set using the sampling formula (Yamane, Citation1967) and allotted to respective kebeles using proportionally to the household size of maize farmers. We used Yamane’s (1967) formula to determine the sample size. Finally, 360 respondents from a total of 3,598 households (Damot Pulasa District Agriculture and Natural Resource Office (Damot Pulasa District Agriculture and Natural Resource Office DPDANRO, Citation2019) in selected kebeles were chosen using systematic random sampling (with an interval of 10). The proportionality to the number of maize producers in each kebele was used to determine the sample distribution in selected kebeles. As displayed in Table , 113, 99, 80, and 68 homes from the Lera, Tontome Menta, Gudicho, and Pulassa bakala kebeles were chosen, respectively.

Table 1. Sample size and distribution to kebeles

2.3. Data source

To achieve its goals, the study utilized both primary and secondary data. The data used were household surveys from sampled households collected from the study area. The primary data were acquired from 360 sample houses using standardized questionnaires after improvement from the preliminary result of selected five different households from selected kebeles. During the survey, the required information was collected on factors that affect maize market involvement among smallholder maize producers. The study’s questionnaire was also designed to elicit responses from the selected farmers on their agricultural and marketing activities. Further, to back primary investigation results information about the research area maize production, marketing, and research findings from secondary data were gathered from published and unpublished documents, including research articles, and reports from Central Statistical Agency (CSA), and the zone sector offices.

2.4. Data analysis

The acquired data were statistically examined using inferential statistics and econometric models in the Stata 14 statistical package. The Heckman two-stage econometric model was employed due to survey data truncation and observed sample selection bias. The model differentiates between the first and second decisions involved and the intensity of participation (Heckman, Citation1976). The decision to join the maize market, as well as the level of market penetration, are response and outcome variables in the Heckman two-stage model, respectively. The statistical significance of the inverse Mills ratio (IMR) of this research indicated that two judgments are interconnected, which makes the model more appropriate for analyzing the current data in contrast to other competing models, such as Tobit, Double hurdle, and OLS (Ordinary Least Square model). The model was built in two steps to estimate: first, a probit model (for the selection equation) and then OLS regression (for the outcome equation). Farmers who grow maize make a specific decision to trade or not trade maize in the first stage. Farmers, on the other hand, make a continual decision on the marketable surplus in the later step, which is conditional on their first decision.

As illustrated in the formula below, a probit model predicts whether a particular household participated in the maize market (Equation 1).

where zi is an indicator variable with a value of unity for smallholder maize farmers who participated in the marketing, Ф is the standard normal cumulative distribution function, wi is the vector of factors influencing the decision to participate in the maize market, α is the vector of coefficients to be estimated, and εi denotes the error term assumed to be normally distributed with a mean of zero and constant variance. The variable has a value of 1 if the marginal utility of participating in maize marketing is greater than zero and 0 otherwise. To calculate the IMR we used the following formula (Equation 2):

where φ is the normal probability density function (PDF).

The second step, OLS is given by (Equation 3):

where E is the expectation operator, Y is the size of maize traded, λi (lambda) is the IMR that corrects sample selection bias, xi is a vector of explanatory variables (Table ) influencing the amount of maize traded, and β is the vector of the parameters to be computed. Thus, Yi can be denoted as Equation 4:

Table 2. Description and hypothesis of variables

Yi * is only observed for those maize producers that are involved in maize trade and ui ~ N (0, σ2), in this case, Yi= Yi *. The differential probability of the involvement determines the marginal effects of the attributes on participation. It is specified in Equation 5;

2.5. Model diagnostics

Several factors were hypothesized (Table ) to influence the maize trading decisions and maize marketable surplus of respondents (Abajobir et al., Citation2018; Abdul-Rahman and Donkoh, Citation2015; Ahmed et al., Citation2018; Alene et al., Citation2008; Beadgie and Zemedu, Citation2019; Bealu et al., Citation2013; Changalima and Ismail, Citation2022; Degefa et al., Citation2017; Degye & Dagmawit, Citation2016; Erge et al., Citation2016; Galtsa et al., Citation2022; Gani and Adeoti, Citation2011; Gebre et al., Citation2021; Gecho and Punjabi, Citation2011; Giref, Citation2016; Ismail and Changalima, Citation2019; Ismail, Citation2022; Iticha, Citation2020; Kabeto, Citation2014; Martey et al., Citation2012; Rashid et al., Citation2019; Rehima & Dawit, Citation2012; Shafi et al., Citation2014; Sigei et al., Citation2014; Zeberga, Citation2010). As mentioned above, the Heckman two-stage selection econometric model was used to due to it considers selectivity bias. The checking for multicollinearity, heteroscedasticity, and omitted variable issues was made before the estimation process to obtain consistent, unbiased, and valid results. The variance inflation factor (VIF) and contingency coefficient are common measures of multicollinearity when dealing with continuous and dummy variables, respectively. The VIF for continuous variables is less than 10, and the contingency coefficient for categorical variables is less than 1, which indicates that there is no multicollinearity problem for variables considered in the model. As evidenced by the insignificant Brueshpagan heteroscedasticity test result (Prob > chi2 = 0.183), the data also have no problem with heteroscedasticity. Moreover, the omitted variable test (ovtest) result of (Prob > F = 0.796) suggests that there is no problem with omitted variables in the model specification.

3. Results and discussions

3.1. The statistical summary of the sampled households

We summarized the household characteristics in Table . The annual maize yields for maize sellers and non-sellers are significantly different. On average, 21.44 quintals were computed for participants, while yields for nonmarket participants were 7.92 quintals. Furthermore, market participants’ average year of schooling was found to be 2.61 years, whereas nonmarket participants’ was 2.02, which is statistically significant at 10%. This implies that market participants were better educated than nonmarket participants. The average farm experience of households in the maize market was 16.34 years, while nonmarket participants had 15.21 years, and the overall average maize farming experience of the two groups was 15.72 years, which is significantly different. This entails that experienced farmers understand how to prepare the land, the planting and harvesting periods, and how to use the input to suitably increased family participation. Maize market participants had significantly larger farm sizes (0.72) than nonparticipant farmers (0.26 ha). The average yearly off-farm revenue for maize traders is 20.60 USD and 20.11 USD for counterparts. We found no significant difference in the frequency of extension contact provided for maize market participants and nonparticipants. The difference in the yearly price of maize was significant that demonstrating maize traders were more interested in higher maize prices received than their counterparts. The primary reason for traders to provide more maize to the market is a higher output value. We also found that market participants were living closer to the marketplace compared to the non-participants.

Table 3. Statistical summary of continuous demographic and socioeconomic variables

Moreover, the summary in Table shows dummy variables. The χ2 result of 64.55 for the sex of household head variable indicates that it was significant (at 1%), which implies that more male maize farmers participated in the market than their counterparts. Further, survey results showed a few maize market participant households have better access to transportation facilities, while the majority do not. However, there is no significant variation in transportation access between the two groups. The chi-square value 76.136 for household credit use indicated that there was a significant difference at a 1%) significance level on credit use. One-quarter of participant households did not use it that is 70.71% of nonparticipants did not use credit services, while the remaining did. This implies that maize traders were more credit users than non-readers. In addition, 38% of maize market participant households had access to market information, while 62.35% of total participant households did not have market information about the current price, demand, and supply of maize. On the other hand, from nonparticipant households, approximately one out of ten households have market information access. The chi-square value of 40.833 indicates that there is a positive and significant difference in market information access between the two groups. Among the maize market participant households in the study area, only 27.16% were cooperative members, while 72.84% were not members of any cooperatives. Of non-market participant households, 28.28% were cooperative members, while 71.72% were nonmembers. However, there was no significant difference between the two parties on cooperative membership. Table also shows that only 16.67% of maize traders and 18.69% of nonparticipant households have access to improved seed variety. However, approximately 83.33% of maize market participants and 81.31% of nonparticipants did not have access to enough improved seed variety. Hence, there was also no statistically significant difference between maize traders and nonreaders.

Table 4. Statistical summary of dummy socioeconomic characteristics variables

Regarding fertilizer utilization on time, approximately 34.57% of sampled market participant households and 34.85% of nonparticipants did have the accessibility to enough fertilizer, but the remaining percentage did not have the accessibility to enough fertilizer. However, the difference is not significant in terms of accessibility of improved seed variety and fertilizer.

3.2. Factors affecting maize trading

Maize is produced in the research area for both market and domestic consumption. It was assumed that demographic and socioeconomic and institutional determinants would influence maize market participation. We summarized significant factors that determine households’ probability of maize market participation (see Table ).

Table 5. Maize market participation and degree of penetration determinants

Maize-producing farmers may be encouraged to engage in the maize market if the market price is attractive. The positive effect of market price on maize market participation means that when market prices rise, the likelihood of maize market participation rises as well. The marginal effect for maize price reveals that when the market price of maize rises by one USD, the chance of maize market participation rises by 0.18%. It argues with the results of Abajobir et al. (Citation2018) and Degye and Dagmawit (Citation2016) who discovered a favorable association between maize market price and market participation. Furthermore, it complies with the results of Kabeto (Citation2014), who showed a positive interrelationship between the price of red beans and market involvement, and Sigei et al. (Citation2014), who discovered positive interrelations between pineapple price with pineapple market participation.

Moreover, household age positively determines maize market participation, which is different from the expected hypothesis. As specified in Table , it positively affected market participation at less than a 1% significance level. This is might be because mature maize-producing farmers can produce a high quantity of products. As a result, they could have a better experience with their farming than young farmers. When the age of the household increases by one extra year, participation in the maize market increases by 29%. Our result is in agreement with the results by Beadgie and Zemedu (Citation2019), Abajobir et al. (Citation2018), and Degye and Dagmawit (Citation2016), who found that increasing the age of the household by one similarly improves the likelihood of maize trading. However, it is not in line with Andaregie et al. (Citation2021) and Citation2020).

The sex of the household head determines maize market participation positively. The econometric outcome of the study demonstrated that being a male family head enhanced the likelihood of maize market participation. The positive impacts of gender, as expected, might be due to less access to information in female-headed households than in their counterparts due to the male-dominated culture in developing countries. Asfaw and Ketema (Citation2014), Abajobir et al. (Citation2018), Beadgie and Zemedu (Citation2019), Degye and Dagmawit (Citation2016), Andaregie et al. (Citation2021), Gebre et al. (Citation2021) and Haile et al. (Citation2022),) reported a positive association between maize market participation and male-headed households.

Household family size further has a positive influence on the decision of maize market participation (Table ). This may be due to the households with large family sizes can produce more amounts by substituting labor and could participate in the maize market. The marginal effect for family size indicates that it increases by one unit, increasing the likelihood of maize trading by 0.719%. This result is in agreement with Changalima and Ismail (Citation2022), Abajobir et al. (Citation2018), Degye and Dagmawit (Citation2016), and Kabeto (Citation2014), who found increasing trends in market participation with increasing family size. This is mainly because a larger family size has contributed to an increase in the volume of maize marketed supply. This result is not in agreement with Citation2020). However, as indicated in Table , our results confirmed that the family size of the households has a negative effect on the amount of maize supplied to the market. This effect of family size on market supply may imply that households with large family sizes allocated more products for consumption purposes and supplied less quantity to the market. The coefficient confirms that one family member increases or decreases the proportion of maize market supply by 12.9%. This finding complies with the study of Haile et al. (Citation2022) and Abajobir et al. (Citation2018) and Kabeto (Citation2014) who found that as the family size of the households increases would lessen the level of market participation.

The household head’s experience in maize farming was anticipated to positively determine farmers’ maize market involvement. Similarly, the econometric result shows that the households’ maize farming experience positively determined maize market participation. As a result, a family with more maize farming experience can produce more maize and participate in the maize market more than less experienced farmers. As household maize farming experience increases by one year, the probability of maize market participation increases by 0.22%. This finding is in agreement with the findings of Adeoti et al. (Citation2014) and Oparinde and Daramola (Citation2014) who reported that the household head’s experience and farm practice had a significant influence on maize market participation. It is also in line with Andaregie et al. (Citation2021). However, it is not in line with Haile et al. (Citation2022) finding in the Gamo Gofa zone, in southern Ethiopia.

Our result further confirmed that poor household market access had a negative influence on market participation. It shows that as the distance to the market increases by one kilometer, the chance of maize market participation decreases by 1.68%. Similar findings by Changalima and Ismail (Citation2022), Kabeto (Citation2014), and Gebremedhin and Tegegne (Citation2012) Indicated that smallholder households located away from market centers were found to have less market participation as that distance to the nearest markets. It has been discovered that the distance to the market has a negative impact on pineapple market participation in Kenya (Sigei et al., Citation2014). Moreover, Abajobir et al. (Citation2018) and Degye and Dagmawit (Citation2016) found a negative association between maize market participation and market distance in their studies. This means that when the kilometer to the market increases by one, the degree of maize market participation decreases by 0.22 quintals. This is in line with the red bean market participation study by Kabeto (Citation2014) in the Halaba special district. Additionally, it has been found to have a negative impact on the level of pineapple marketing in Kenya by Sigei et al. (Citation2014).

However, household transportation access has a positive influence on maize farmers’ market participation decisions. The marginal effect of the result revealed that access to a means of transport increases by kilometer, and the chance of maize market involvement increases by 4.54%. This implies that when farmers access transportation, farmers are more likely to produce a surplus and contribute to the market. The smallholder farmer’s better access to transportation helps them to transport farm inputs and outputs to the market. This finding is consistent with Kabeto’s (Citation2014) and Sigei et al.'s (Citation2014) findings on red bean and pineapple trading, respectively, which stated that owning a mode of transportation had a positive influence on market participation. This is because of its critical role in lowering transportation costs and increasing transportation volume. Furthermore, access to transportation has a positive and significant influence on the extent of maize trade. The one-kilometer access to the market increases the proportion of maize supply by 0.577 quintals. Because access to transportation plays a critical role in lowering transportation costs and increasing transport volume, maize sales to the market increase. Similarly, Sigei et al. (Citation2014) discovered that the greater the number of vehicle owners, the higher the volume of pineapple supply to the market. Furthermore, Kabeto’s (Citation2014) discovered possession of means of transport had a positive impact on the extent to which red bean farmers participated in the market. Abajobir et al. (Citation2018) discovered in their study that it also has a positive and significant influence on maize supply.

As expected, household extension contact determines maize market involvement positively. The marginal effect confirms that increasing extension contact by a single day increases the possibility of maize market participation by 0.47%. As a result, households with extension contact on input use, price, and demand at the required time have a greater implication on maize market participation. This finding complies with Abajobir et al.'s (Citation2018) study, which discovered a positive and significant link between the frequency of extension contacts per year and market participation decisions.

Furthermore, the use of credit services had a significant and positive influence on farmers’ possibility of being involved in the maize market. Credit-user households have a 3.57% higher possibility of participating in maize trade than noncredit-user households. This would be because credit users may hire more laborers and buy better seeds and fertilizers on time than nonusers. This finding is consistent with the findings of Beadgie and Zemedu (Citation2019), Abajobir et al. (Citation2018), and Kabeto’s (Citation2014), who found that credit access and use had a positive and significant influence on smallholder farmers’ likelihood of participating in maize marketing. In addition, it has a similar influence on the extent of maize marketing at a level of less than 1% significance. It is a critical tool for households to purchase inputs, materials, and pesticides, hire laborers on time and at the right price, and increase production when compared to noncredit users. An increase in credit used in one USD increased the level of maize market participation by 1.445 quintals. This result is consistent with the findings of Beadgie and Zemedu (Citation2019) and Kabeto’s (Citation2014) about a positive and significant influence on the extent of maize trading with credit access and use.

An increase in off-farm income had also a significant and positive influence on maize market involvement. Maize producers with higher off-farm revenue may be able to participate more effectively than farmers with less off-farm income because they can easily purchase inputs and hire laborers. The marginal effect output confirms that as annual off-farm income rises by one USD, the possibility of maize trading increases by 0.94%. This result is consistent with the research of Degye and Dagmawit (Citation2016) and Andaregie et al. (Citation2021), who discovered that the more off-farm income there is, the greater the likelihood of market involvement. Furthermore, this was similar to the survey finding of Sigei et al. (Citation2014), who obtained a positive and significant link between pineapple marketing and off-farm income.

Furthermore, the land size for maize farming had a positive effect on the maize supply. This may be because farmers with larger farming land can produce maize in greater quantities and participate in greater numbers than farmers with smaller farming land. This is consistent with Degye and Dagmawit (Citation2016), who discovered a significant positive link between farm output marketing and land size. This study found that increasing the size of land by hectare increases the proportion of the volume of the market supply of maize by 10.783 quintals. These findings are in line with that of Adenegan et al. (Citation2012), who found that households with large farmland could partake in the maize market at a higher level than households with small farmland.

Household cooperative membership had a significant positive effect on the extent of maize trading. This means that household members obtain inputs (fertilizers, seeds, pesticides, credits, and so on) that increase farmer output and encourage maize households to be more involved in the maize market. The result confirms that cooperative members supply 0.934 quintals more maize to the market than their counterparts. Similarly, Beadgie and Zemedu (Citation2019) and Musah (Citation2013) found that membership in cooperative organizations was related to maize production and the extent of maize marketing positively. This finding is also in agreement with Andaregie et al. (Citation2021). However, the result is not consistent with Haile et al. (Citation2022).

Household access to market information has a significant and positive impact on maize supply. This confirms that families with better market info supply approximately 1.907 quintals of maize to the market than their counterparts. This implies that access to market info decreases farmers’ risk aversion conduct by obtaining a market and then reduces farmers’ transaction costs, which determines the maize marketable surplus. This result is consistent with the findings of Ismail (Citation2023),Changalima et al. (Citation2022), Beadgie and Zemedu (Citation2019), Degye and Dagmawit (Citation2016), and Urgessa (Citation2011), who indicated that with more access to the market, more households are likely to participate in maize marketing. Furthermore, it agrees with that of Sigei et al. (Citation2014), who discovered price information has a significant positive influence on the extent of market participation in pineapple sales.

4. Conclusions and implications

We found that the annual price of maize sold per quintal, age, sex, family size, maize farming experience, proximity to district market, ownership of means of transportation, extension contact, credit service, and yearly off-farm income were all factors that significantly determined households’ probability of maize market participation.

This significant influence demonstrates the need for a supporting situation to increase smallholders’ capacity to deliver quality maize products in larger quantities. As a result, the following recommendations were developed to increase maize farmers’ market participation and extent.

This infers that the accessibility of credit, particularly during the plantation period, may encourage farmers to produce more and participate in the market. Improving farmer access to credit should be a top priority to improve maize market performance, efficiency, and consumer welfare. As a result, the government should invest in and encourage credit service provider satisfaction to solve problems associated with the utilization of credit.

Improving access to maize market information appears to be necessary for maize market decisions, and steady and trustworthy communication and information presented understandably appear to be most valuable. Moreover, the government should develop and expand methods for farmers to easily access market information via easily accessible technologies such as mobile phones and local radio channels, and it is vital to invest in raising awareness and training, particularly in encouraging farmers to adopt new technology and developing the skills and knowledge of smallholder farmers so that they can easily trade maize.

Raising farmers’ bargaining power in setting market prices for their products is anticipated to positively affect a household’s maize marketing choice, thus establishing a fair and motivating price for farmers’ produce needed. Access to rural infrastructures, especially road connections, to ease the transportation of maize from the production site to the market point is needed; thus, farmers can be easily involved in the maize trade. Empowering activities should be considered for increasing gender awareness, which can be accomplished by endowing more women to participate in maize trading. Households should be enticed to join cooperatives. The government and other interested parties should educate smallholder farmers about the advantages of joining cooperatives.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Alula Tafesse

Alula Tafesse is an Assistant Professor and senior researcher at the Department of Agricultural Economics, College of Agriculture, Wolaita Sodo University.

Gezahagn Gechere

Gezahagn Gechere is MSc student at the Department of Agricultural Economics, College of Agriculture, Wolaita Sodo University.

Alemayehu Asale

Alemayehu Asale is an Assistant Professor and researcher at the Department of Agricultural Economics, College of Agriculture, Wolaita Sodo University.

Abrham Belay

Abrham Belay is an Assistant Professor and senior researcher at Hawassa University, Wondo Genet College of Forestry and Natural Resources.

John W. Recha

John W. Recha is Scientist, Climate-Smart Agriculture, and Policy International Livestock Research Institute.

Ermias Aynekulu

Ermias Aynekulu is Landscape ecologist, Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR) & World Agroforestry (ICRAF)

Zerihun Berhane

Zerihun Berhane is an Associate Professor of Development Studies and Head, the Center for African and Asian Studies (CAAS), at Addis Ababa University

Philip M. Osano

Philip M. Osano works at Stockholm Environment Institute-Africa, World Agroforestry Centre

Teferi D. Demissie

Teferi D. Demissie at International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI)

Dawit Solomon

Dawit Solomon works at International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI)

Notes

1. The lowest administrative unit in Ethiopia.

References

- Abajobir, B. N., Zemedu, L., & Ademe, A. (2018). Analysis Of Maize Value Chain: The Case Of Guduru Woreda, Horro Guduru Wollega Zone Of Oromia Regional State, Ethiopia (MSc thesis, Haramaya university).

- Abayneh, Y., & Tefera, T. (2013). Factors influencing market participation decision and extent of participation of haricot bean farmers in Meskan District, Ethiopia. International Journal of Management and Development Studies, 2(8), 17–15.

- Abdul-Rahman, F. A., & Donkoh, S. A. (2015). Analysis of the maize value chain development in the northern region, the case of the Association of Church Development Programme (ACDEP).

- Adenegan, K. O., Adepoju, A., & Nwauwa, L. O. E. (2012). Determinants of market participation of maize farmers in rural Osun State of Nigeria. International Journal of Agricultural Economics & Rural Development, 5(1), 28–39.

- Adeoti, A. I., Oluwatayo, I. B., & Soliu, R. O. (2014). Determinants of market participation among maize producers in Oyo State, Nigeria. British Journal of Economics, Management and Trade, 4(7), 1115–1127. https://doi.org/10.9734/BJEMT/2014/7826

- Ahmed, M. H., Tazeze, A., Mezgebo, A., & Andualem, E. (2018). Measuring maize production efficiency in eastern Ethiopia: Stochastic frontier approach. African Journal of Science, Technology, Innovation and Development, 10(7), 779–786. https://doi.org/10.1080/20421338.2018.1514757

- Alene, A. D., Manyong, V. M., Omanya, G., Mignouna, H. D., Bokanga, M., & Odhiambo, G. (2008). Smallholder market participation under transactions costs: Maize supply and fertilizer demand in Kenya. Food Policy, 33(4), 318–328. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2007.12.001

- Andaregie, A., Astatkie, T., & Teshome, F. (2021). Determinants of market participation decision by smallholder haricot bean (Phaseolus vulgaris l.) farmers in Northwest Ethiopia. Cogent Food & Agriculture, 7(1), 1879715. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311932.2021.1879715

- Asfaw, H., & Ketema, M. (2014). Durum wheat value chain analysis: The case of Gololcha district of Bale zone, Ethiopia (Doctoral dissertation, MSc Thesis, Haramaya University).

- Bank, W. (2007). World development report 2008: Agriculture for development, The World Bank.

- Beadgie, W. Y., & Zemedu, L. (2019). Analysis of maize marketing; the case of Farta Woreda, South Gondar Zone, Ethiopia. International Journal of Agricultural Economics, 4(4), 169. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ijae.20190404.15

- Bealu, T., Endrias, G., & Tadesse, A. (2013, November). Factors affecting economic efficiency in maize production: The case of Boricha Woreda in Sidama Zone, Southern Ethiopia. In The Fourth Regional Conference of The Southern Nationalities State Economic Development in Hawassa. Ethiopia. (p. 28).

- Changalima, I. A., & Ismail, I. J. (2022). Agriculture supply chain challenges and smallholder maize farmers’ market participation decisions in Tanzania. Tanzania Journal of Agricultural Sciences, 21(1), 104–120.

- Cochrane, L., & Bekele, Y. W. (2018). Average crop yield (2001–2017) in Ethiopia: Trends at national, regional and zonal levels. Data in Brief, 16, 1025. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dib.2017.12.039

- Damot Pulasa District Agriculture and Natural Resource Office (DPDANRO). (2019). Annual Report, Shanto,

- Degefa, K., Jaleta, M., & Legesse, B. (2017). Economic efficiency of smallholder farmers in maize production in Bako Tibe district, Ethiopia. Developing Country Studies, 7(2), 80–86.

- Degye, G., & Dagmawit, G. S. (2016). Maize value chain analysis in south afhefer and jabitehnan districts of Amhara region. Harmaya University.

- Erge, B. E., Goshu, D., & Jaleta, M. (2016). Value chain analysis of maize: The case of Bako Tibe and Gobu Sayo districts in central west Ethiopia.

- FAO. (2021). World food and agriculture - statistical yearbook 2021. Rome. https://doi.org/10.4060/cb4477en

- Galtsa, D., Tarekegn, K., Kamaylo, K., Oyka, E., & Xiao, X. (2022). Maize market chain analysis and the determinants of market participation in the Gamo and Gofa Zones of Southern Ethiopia. Advances in Agriculture, 2022, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/2784497

- Gani, B., & Adeoti, A. (2011). Analysis of market participation and rural poverty among farmers in the northern part of Taraba State, Nigeria. Journal of Economics, 2(1), 23–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/09765239.2011.11884934

- Gebre, G. G., Isoda, H., Rahut, D. B., Amekawa, Y., & Nomura, H. (2021). Gender gaps in market participation among individual and joint decision-making farm households: Evidence from Southern Ethiopia. European Journal of Development Research, 33(3), 649–683. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41287-020-00289-6

- Gebremedhin, B., & Tegegne, A. (2012). Market orientation and market participation of smallholders in Ethiopia: Implications for commercial transformation.

- Gecho, Y., & Punjabi, N. (2011). Determinants of adoption of improved maize technology in Damot Gale, Wolaita, Ethiopia. Rajasthan Journal of Extension Education, 19(1), 1–9.

- Giref, D. (2016). Maize value chain analysis in south Achefer and Jabitehnan districts of ANRS, MSc Thesis,Haramaya University,

- Haile, K., Gebre, E., & Workye, A. (2022). Determinants of market participation among smallholder farmers in Southwest Ethiopia: Double-hurdle model approach. Agriculture & Food Security, 11(1), 18.

- Heckman, J. J. (1976). The common structure of statistical models of truncation, sample selection and limited dependent variables and a simple estimator for such models. In Annals of economic and social measurement (Vol. 5, No. 4, pp. 475–492). NBER.

- Ismail, I. J. (2022). Market participation among smallholder farmers in Tanzania: Determining the dimensionality and influence of psychological contracts. Journal of Agribusiness in Developing and Emerging Economies, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1108/JADEE-07-2021-0183

- Ismail, I. J. (2023). Seeing through digitalization! The influence of entrepreneurial networks on market participation among smallholder farmers in Tanzania. The mediating role of digital technology. Cogent Food & Agriculture, 9(1), 2171834. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311932.2023.2171834

- Ismail, I. J., & Changalima, I. A. (2019). Postharvest losses in maize: Determinants and effects on profitability of processing agribusiness enterprises in Tanzania. East African Journal of Social and Applied Sciences (EAJ-SAS), 1(2), 203–211.

- Iticha, M. D. (2020). Review on determinants of economic efficiency of smallholder maize production in Ethiopia. International Journal of Agricultural Economics, 5(4), 123–132. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ijae.20200504.15

- Kabeto, A. J. (2014). An analysis of factors influencing participation of smallholder farmers in red bean marketing in Halaba Special District. Ethiopia, University of Nairobi.

- Martey, E., Al-Hassan, R. M., & Kuwornu, J. K. (2012). Commercialization of smallholder agriculture in Ghana: A Tobit regression analysis. African Journal of Agricultural Research, 7(14), 2131–2141.

- Milkias, D., & Abdulahi, A. (2018). Determinants of agricultural technology adoption: The case of improved highland maize varieties in Toke Kutaye District, Oromia regional State, Ethiopia. Journal of Investment and Management, 7(4), 125–132. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.jim.20180704.13

- Musah, A. B. (2013). Market participation of smallholder farmers in the upper west region of Ghana. University of Ghana.

- Niankara, I., & Traoret, R. I. (2019). Formal education and the contemporaneous dynamics of literacy, labour market participation and poverty reduction in Burkina Faso. International Journal of Education Economics and Development, 10(2), 148–172. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJEED.2019.098679

- Olwande, J., & Mathenge, M. K. (2011). Market participation among poor rural households in Kenya.

- Oparinde, L. O., & Daramola, A. G. (2014). Determinants of market participation by maize farmers in Ondo State, Nigeria. Journal of Economics and Sustainable Development, 5(1), 69–77.

- Rashid, S., Getnet, K., & Lemma, S. (2019). Maize value chain potential in Ethiopia: Constraints and opportunities for enhancing the system. Gates Open Res, 3(354), 354.

- Regasa Megerssa, G., Negash, R., Bekele, A. E., & Nemera, D. B. (2020). Smallholder market participation and its associated factors: Evidence from Ethiopian vegetable producers. Cogent Food & Agriculture, 6(1), 1783173. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311932.2020.1783173

- Rehima, M., & Dawit, A. (2012). Red pepper marketing in Siltie and Alaba in SNNPRS of Ethiopia: Factors affecting households’ marketed pepper. International Research Journal of Agricultural Science and Soil Science, 2(6), 261–266.

- Shafi, T., Zemedu, L., & Geta, E. (2014). Market chain analysis of papaya (Carica papaya): The case of Dugda district, eastern Shewa zone, Oromia national regional state of Ethiopia. Journal of Agricultural Economics and Development, 3(8), 120–130.

- Sigei, G., Bett, H., & Kibet, L. (2014). Determinants of market participation among small-scale pineapple farmers in Kericho County. Egerton University, Kenya.

- Urgessa, M. (2011). Market chain analysis of teff and wheat production in Halaba special Woreda. (MSc thesis, Haramaya University, Ethiopia).

- Vandenbroucke, F., & Cantillon, B. (2014). Reconciling work and poverty reduction. How successful are European welfare states?

- Wolaita Zone Agriculture and Natural Resource Office (WZANRO). (2019). Annual Report.

- Yamane, T. (1973). Statistics: An introductory. analysis–3.

- Zeberga, A. (2010). Analysis of poultry market chain: The case of Dale and Alaba’. Special’Woredas of SNNPRS, Ethiopia, Haramaya University.

- Zegeye, T., Tadesse, B., & Tesfaye, S. (2001). Determinants of adoption of improved maize technologies in major maize growing regions in Ethiopia.