?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

The main aim of the research was to analyze whether nutrition education and farm production diversification improved household dietary diversity as well as fruit and vegetable consumption among rural households in Zimbabwe. A cross-sectional survey using systematic random sampling was conducted in eight rural districts covering 1417 households. Poisson, Instrumental Variables Poisson, and Instrumental Variables probit regressions were used for analysis. Nutrition education and farm production diversity were associated with 53% and 2% increase in household dietary diversity, respectively. Nutrition education shows a significant and positive association with both fruits and vegetables intake. Nutrition education was associated with a 50% and 18% likelihood of consuming fruits and vegetables, respectively. Farm production diversification was associated with fruit consumption among rural households. Using alternative model specifications, we note that nutrition education was associated with an increase in the frequency of consuming vegetables. Farm production diversification and income were positively correlated with the frequency of fruit intake. Therefore, government, private sector, and development agencies need to promote nutrition education programs that emphasize production and consumption of fruits and vegetables. Second, interventions that promote crop and livestock diversification, including household cultivation of nutrient-rich fruits and vegetables, need to be upscaled.

Highlights

Nutrition education enhanced consumption of fruits and vegetablesFarm production diversification enhanced fruit consumptionNutrition education programs promote production and consumption of fruits and vegetablesCrop diversification should include cultivation of fruits and vegetables

Public Interest Statement

Fruit and vegetable consumption is important for nutrition and health. Yet, their consumption is low in many developing countries. Nutrition education, community nutrition gardens, and farm production diversification are some interventions being promoted to improve fruit and vegetable consumption intervention. The extent to which nutrition education and production diversification improve fruit and vegetable consumption has creceived less research attention. The study analysed factors influencing household fruit and vegetable consumption and whether nutrition education and farm production diversification are important drivers. Nutrition education was positively related with the eating of fruits and vegetables. Farm production diversification enhanced fruit consumption. The government, private sector and development agencies need to promote nutrition education programs that emphasize production and consumption of fruits and vegetables. In addition, interventions that promote crop and livestock diversification, including household cultivation of nutrient-rich fruits and vegetables, need to be upscaled.

1. Introduction

Inadequate eating of fruits and vegetables is among the drivers of higher incidences of diseases, including cancer, diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases (Madzorera et al., Citation2021; Miller et al., Citation2016, Citation2017; Mokdad et al., Citation2015) in Zimbabwe and other countries. In their study, Miller et al. (Citation2017) highlighted that adequate fruit and vegetables consumption reduced the risk of heart attack, stroke, cancer, and diabetes among other diseases in Zimbabwe as well as other 17 countries. The consumption of vegetables and fruits remains low in Africa, despite their documented health benefits. For instance, only 13% of Zimbabwean population consumed at least 400 g per day of fruits and vegetables required by WHO (ZIMSTAT, Citation2018). Elsewhere, in South Africa, Faber et al. (Citation2013) found that less than 10% of the interviewed respondents consumed the recommended five servings of vegetables and fruits per day. Peltzer and Pengpid (Citation2010) also report that only 22% of the respondents met the daily recommended servings of fruit and vegetable consumption in seven selected African nations.

Interventions that promote the sufficient intake of fruits and vegetables have the potential to improve nutrition and avert disease development. Therefore, there is need for designing strategies that promote the growing and eating of fruits and vegetables in developing countries. Numerous strategies continue to be implemented to address these challenges. These include the promotion of vegetable gardens at household, community, or school level (Roothaert et al., Citation2021), provision of food vouchers to purchase these food items, nutrition education, and income generation activities (Roothaert et al., Citation2021). Existing evidence suggests that promoting nutrition education, farm diversification, market access, and income are some key strategies for improved dietary quality and nutrition (Habtemariam et al., Citation2021; Murendo et al., Citation2018; Pradhan et al., Citation2021; Shrestha et al., Citation2021; Sibhatu & Qaim, Citation2018).

From literature, a number of studies demonstrate that nutrition education is one of the effective avenues for promoting the production and eating of fruits and vegetables (Bernstein et al., Citation2002; Gullotta & Bloom, Citation2014; Patel et al., Citation2020; Pradhan et al., Citation2021; Selvaraj et al., Citation2021; Wagner et al., Citation2016). For example, nutrition education programmes increased knowhow of the sizes of portions and intake of fruits and vegetables (Gullotta & Bloom, Citation2014; Patel et al., Citation2020; Selvaraj et al., Citation2021). It was observed that nutrition education improved fruit and vegetable intake (Athare et al., Citation2020; Wagner et al., Citation2016) among adults, while Bernstein et al. (Citation2002) also found that nutrition education increased fruit, vegetable, and calcium-rich food consumption.

There are notable pathways through which nutrition education could potentially improve the intake of fruits and vegetables (Nanney et al., Citation2007; Olawuyi et al., Citation2018) among others. First, nutrition education builds human capital that will trigger production diversity and subsequent consumption diversity (Pradhan et al., Citation2021) including fruits and vegetables. Second, nutrition education focuses on increasing knowledge on nutritive and health values of different foods and the associated benefits of balanced diets (Nanney et al., Citation2007; Pradhan et al., Citation2021; Shrestha et al., Citation2021; Wagner et al., Citation2016) foods. More recently, authors have started investigating the association between nutrition education (Murendo et al., Citation2018; Shrestha et al., Citation2021) and farm production diversity (Habtemariam et al., Citation2021; Sariyev et al., Citation2021) on dietary diversity. Nutrition and health education has been seen to improve both nutrition and health knowledge, diet quality, and nutrition status among individuals (Murendo et al., Citation2018; Xu et al., Citation2021). For farm production diversity, the main potential pathways for improved consumption of fruits and vegetables are twofold. First, farm production diversification ensures availability of diverse food items for the household including fruits and vegetables, which, subsequently, improves diet quality and nutrition (Habtemariam et al., Citation2021; Sibhatu et al., Citation2015). Second, producing a diverse range of farm commodities can lead to increased household incomes for buying and eating of fruits and vegetables and other diverse food items (Habtemariam et al., Citation2021; Sibhatu et al., Citation2015).

Recent literature concur that fruits and vegetable consumption are a common feature in all indicators employed for investigating the risks of non-communicable diseasesfor example,: Alternative Healthy Eating Index, Dietary Quality Index International (Bigman & Ryan, Citation2021), and Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (Jacobs et al., Citation2015; Miller et al., Citation2020; Serra-Majem et al., Citation2019). Based on the discussion above, there is a general agreement in the literature that dietary quality associated with micronutrient intake can also be measured using the consumption of micronutrient-rich fruits and vegetables (Miller et al., Citation2020; Serra-Majem et al., Citation2019).

One research gap identified by Sibhatu and Qaim (Citation2018) is that the majority of studies on nutrition in developing countries mostly concentrate on dietary diversity and food consumption score only (Habtemariam et al., Citation2021; Hirvonen et al., Citation2017; Kissoly et al., Citation2020; Murendo et al., Citation2018; Onyeneke et al., Citation2019), and fail to extend and analyze other nutrition indicators, which capture micronutrients, such as vegetables and fruits intake. In addition, the few studies that exist (Choudhury et al., Citation2020; Darfour-Oduro et al., Citation2020; Padrão et al., Citation2012; Sinyolo et al., Citation2020) do not systematically analyze how nutrition education drives fruit and vegetable consumption in a developing country context. Hence, this study helps to address the identified research gap by analyzing how nutrition education and farm production diversity are associated with fruit and vegetable consumption in Zimbabwe.

2. Livelihoods and Food Security Programme (LFSP)

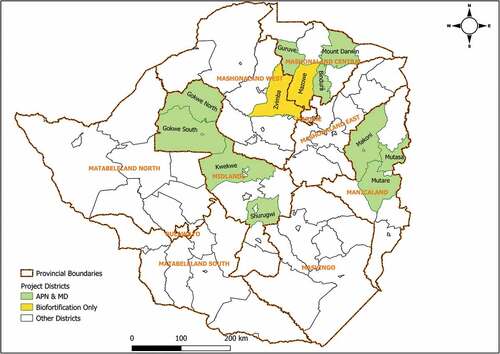

The LFSP received funding from the Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO) of the United Kingdom (LFSP, Citation2021). The LFSP (Szebini et al., Citation2021) was implemented in four provinces from 2014 to 2020 and covered 12 districts as follows: Mutasa, Mutare, and Makoni in Manicaland province, Guruve, Bindura, Mazowe, and Mt Darwin in Mashonaland Central province and Kwekwe, Gokwe North, Gokwe South and Shurugwi in Midlands province as well as Zvimba in Mashonaland West. Bindura, Gokwe North, Mazowe, and Zvimba districts were added to the program from 2018 onwards (LFSP, Citation2021). Three consortiums led by World Vision, Welthungerhilfe, and Practical Action (Szebini et al., Citation2021), respectively, were the implementing partners in Mashonaland Central, Midlands, and Manicaland provinces, respectively. The program aimed to increase food security of 250,000 beneficiary households through improving crop and livestock productivity, increasing income, as well as improving consumption of diversified nutritious foods (LFSP, Citation2021). Various behaviour change communication and nutrition education channels were employed to improve the eating of nutritious foods, among them eggs, vegetables, fruits, biofortified maize and beans. Nutrition awareness and information were disseminated to farmers through community health clubs, field days, videos, WhatsApp, podcasts, and various forums by agriculture and health extension officers, and trained lead farmers and community volunteers.

3. Methodology

3.1. Data sources

This article utilized data from the 2020 LFSP Crop and Livestock Production Assessment implemented by the FAO (Murendo et al., Citation2018). The data were cross-sectional and drawn from the eight traditional districts of the LFSP program as shown in Figure (Murendo et al., Citation2018). Data were drawn from 1417 households from Gokwe South (221), Guruve (99), Kwekwe (209), Makoni (201), Mt Darwin (216), Mutare (197), Mutasa (168), and Shurugwi (106). Households in each wardFootnote1 and district were selected using systematic random sampling using beneficiary lists and a sampling interval of five. The enumerators interviewed individual households with replacement households chosen from the same list next to the absent household and not the next-door neighbour (Murendo et al., Citation2018). Information on household characteristics, agriculture production, expenditure, technology adoption, crop and livestock production, household, and individual nutrition outcomes were collected.

3.2. Measurement

3.2.1. Household dietary diversity

This was calculated for each household using recall data on consumption of 12 food groups over the previous 24-h Food groups used included: cereals, roots and tubers, vegetables, fruits, meat, eggs, fish and seafood, pulses and nuts, milk and milk products, oils, and fats. Acceptable dietary diversity is denoted as the consumption of six or more food groups (Sibhatu et al., Citation2015).

3.2.2. Fruit and vegetable consumption

This was captured using binary variables indicating that fruits and vegetables were eaten by households in the previous 24 h. In the alternative specification, the frequency of fruits and vegetables consumption by household in the past 7 days is used instead of the binary variable.

3.2.3. Nutrition education

Households receiving maternal and child nutrition information were coded as one or zero, otherwise. Various messages such as healthy eating, four-star diets (Murendo et al., Citation2018), and bio-fortification were disseminated to program participants to raise their nutrition knowledge (LFSP, Citation2021).

3.2.4. Farm production diversification

Refers to the sum of livestock and crop species grown on farm households (Kissoly et al., Citation2020; Murendo et al., Citation2018) and is widely used in the literature (Habtemariam et al., Citation2021; Rasmussen et al., Citation2020). Higher farm production diversity (Rasmussen et al., Citation2020) is expected to result in better welfare than those with lower diversification.

3.2.5. Market participation

In this article, market participation as an indicator of commercialization is measured by whether households sold crops or livestock to the market (Kissoly et al., Citation2020; Murendo et al., Citation2018).

4. Estimation strategy

4.1. Household dietary diversity

The following regression model is estimated to understand how nutrition education and farm production diversification (Murendo et al., Citation2018) are associated with dietary diversity.

Where DDSi captures dietary diversity for household i. NEi and FPDi is nutrition education and farm production diversity, respectively. Xi represents all individual and household factors influencing dietary diversity, and β are coefficients for estimation, and εi is the error term. β1 and β2 measure the association of nutrition education and farm production diversification (Kissoly et al., Citation2020; Murendo et al., Citation2018) with dietary diversity, respectively. The dietary diversity of household has values between 0 and 12 and is therefore a count variable (Greene, Citation2012). In this study, nutrition education and farm production diversity are potentially endogenous to dietary diversity (Hirvonen et al., Citation2017; Onyeneke et al., Citation2019). To account for this, we rely on the instrumental variable Poisson (IV Poisson) regression for estimating EquationEquation 1(1)

(1) . The Poisson estimation technique that has been used extensively in the recent studies (Kabir et al., Citation2022; Sibhatu & Qaim, Citation2018; Sibhatu et al., Citation2015) and Hirvonen et al. (Citation2017) used IV Poisson. We use the concentration of households in a ward assessing nutrition education as an instrument. Households residing in a ward with a higher number of households knowledgeable about nutrition are also more likely to transfer it to their neighbours and social networks. Recent studies have used similar approaches to study the impact of health or nutrition knowledge on various behavioral outcomes (Hirvonen et al., Citation2017). The incident rate ratios (IRRs) from the Poisson estimator denote the percentage change in the outcome variable as independent variable shifts by a unit (Greene, Citation2012; Long et al., Citation2014; Murendo et al., Citation2018). An IRR of one or greater shows a positive effect, while less than one denotes a negative relationship.

4.2. Fruits and vegetable consumption

Fruits and vegetables intake are expected to be driven by nutrition education and farm production diversification and other factors. To systematically answer this, a regression model is denoted as:

Where FVi captures fruit or vegetable consumption for household i. NEi and FPDi is nutrition education and farm production diversification, respectively. The variable Xi represents a vector of other characteristics influencing fruit and vegetable consumption, and the β the coefficients for estimation, and εi is the error term. Nutrition education and farm production diversity could potentially be endogenous to fruit and vegetable intake. Using the same instrument, mentioned above, we test for endogeneity and use probit and Instrumental Variable (IV) Probit regression to understand the association between nutrition education and farm production diversity and fruit and vegetable consumption (Cameron & Trivedi, Citation2010)

We also specified the frequency of fruit and vegetable consumption (Sinyolo et al., Citation2020) as separate outcome variables to check if our model is robust to alternative specification. Since the frequency is a count variable, we estimated the Instrumental Variable Poisson model in the alternative specification (Cameron & Trivedi, Citation2010; Greene, Citation2012). The study uses cross-section data, and it must be noted that our findings show potential associations and not causality and should be interpreted with caution.

5. Results and discussion

5.1. Descriptive analysis

The sample summary statistics are shown in Table . The consumption of six or more food groups is a useful indicator of household nutrition adequacy (Sibhatu et al., Citation2015). About 61% of households had acceptable dietary diversity. The low levels of dietary diversity among 39% of the households can potentially be attributed to poor harvest owing to low rainfall received in the 2019/20 season. During the previous day, about 83% of the respondents ate vegetables, but much fewer (38%) ate fruits. These results support the notion that the consumption of fruits in Zimbabwe is low (Miller et al., Citation2016) and further enquiry to identify the barriers to fruit consumption are needed. About 74% of households received nutrition information. On average, households produced a total of 6 crop and livestock species in the study districts. About 98% of households participated in the market by selling crops and or livestock sales. Also, the mean income was 107 United States Dollars.

Table 1. Sample summary statistics

5.2. Does nutrition education and farm production diversification improve dietary diversity?

Results from an earlier study from the same area found that nutrition education and farm production diversification (Murendo et al., Citation2018) improved household nutrition. Using a more recent dataset from the same study area, we seek to understand if these positive associations still hold. Nutrition education was found to be positively related to an improvement in household dietary diversity (Table ). Nutrition education is associated with a 53% increase in household dietary diversity. Producing one additional crop or livestock species (production diversity) is associated with 2.1% increase in household dietary diversity. These findings are consistent with earlier studies and demonstrate that nutrition education, complemented by farm production diversification (Murendo et al., Citation2018) are important for household dietary diversity and resonates with other recent similar studies (Gupta et al., Citation2020; Habtemariam et al., Citation2021; Nandi et al., Citation2021).

Table 2. Correlating nutrition education and production diversity to household dietary diversity

Market participation was found to have no effect on household dietary diversity, contradicting previous literature that demonstrated positive effects (Gupta et al., Citation2020; Murendo et al., Citation2018; Nandi et al., Citation2021). Although, there is a notion that commercialization improves nutrition and welfare of rural households, the empirical evidence is somewhat mixed (Habtemariam et al., Citation2021). An IRR of 1.057 on education indicates that household head with one more year of education of the household head is associated with a 5.7% increase in the food groups consumed. This is in line with findings from Onyeneke et al. (Citation2019) and Ochieng et al. (Citation2017). Education increases individuals' ability to access and understand information concerning the benefits of consuming nutritious foods and therefore improves nutrition knowledge, as observed by Onyeneke et al. (Citation2019). Larger households are associated with reduced dietary diversity. Land size is positively associated with household dietary diversity. Land is a crucial factor, and households owning larger land sizes tend to have higher dietary diversity. Most of the households in the study districts rely on agriculture, thus land is important for food production and dietary diversity. Ochieng et al. (Citation2017) reported similar findings for the case of Tanzania. Similar to other studies (Mayén et al., Citation2014), income is positively related to household dietary diversity.

5.3. Nutrition education, production diversity, and consumption of fruits and vegetables

Table shows the instrumental variable probit model findings on whether nutrition education and production diversification are associated with intake of fruits and vegetables. The parameter ath(ρ) was insignificant for the fruit regression model, indicating that there is no selection bias, and the results can be estimated using the normal probit regression (Miyata et al., Citation2009). However, for the vegetable model, the ath(ρ) parameter is significant denoting selection bias, and the results are estimated with IV probit regression. This is also confirmed by the Wald test of exogeneity, which denotes the absence and presence of endogeneity issues for fruit and vegetable models. Therefore, the IV probit regression is ideal for estimating the determinants of vegetable consumption. The instrument is positively related with nutrition education. We therefore rely on probit regression (column 2) and IV probit (column 6) for estimating determinants of fruit and vegetables consumption, respectively.

Table 3. Correlating nutrition education and production diversification to consumption of fruits and vegetables

Nutrition education is associated with a 50% and 18% likelihood of consuming fruits and vegetables, respectively. Nutrition education shows a significant and positive association with both fruits and vegetables intake. The results indicate that nutrition education through various behaviour change communication strategies has a huge effect in encouraging the eating of fruits and vegetables to supply micronutrients. This resonates with other studies showing that nutrition education improves fruit and vegetable consumption among children and adolescents in developing country context (Patel et al., Citation2020). We now turn to the role of farm production diversification. Producing one additional crop or livestock species (production diversity) is associated with 5% increase in consumption of fruits only. These results show that nutrition education complemented by farm production diversification increases fruit intake among rural households in the study area.

Surprisingly, market participation and land ownership produced a negative association with fruit intake and no relationship with vegetable consumption. This could be due to the fact that income from market sales is usually used for household needs, for example, education, health care, and purchase of basic commodities, and little is reserved for purchase of fruits and vegetables. In addition, our measure of market access used in this study may not be robust. A more appropriate measure could have asked households if they purchased and/or sold fruits and vegetables. In Zimbabwe, fruit consumption is seasonal and usually low in rural areas. Households with a large number of members tend not to consume fruits.

5.4. Nutrition education, production diversity and frequency of eating fruits and vegetables

Table shows the instrumental variable Poisson estimates on whether nutrition education and production diversification are associated with the frequency of consuming fruits and vegetables. Holding other factors constant, nutrition education is associated with a 99% increase in the frequency of consumption of vegetables (Table ). Producing one additional crop or livestock species (production diversity) is associated with an 8% increase in the frequency of consuming fruits. Income is associated with a 5% increase in the frequency of consuming fruits. Contrary to expectations, market access is associated with lower frequency of eating fruits and no association with vegetable consumption. Usually, households rely on consuming fruits and vegetables from their own production and do not rely on markets for this. This result could also be a dummy measurement of market access compared to a more robust measure that uses market intensity. Resonating with earlier literature, income was positively correlated with frequency of fruit intake (Choudhury et al., Citation2020; Lallukka et al., Citation2010; Miller et al., Citation2016; Pechey et al., Citation2015; Sinyolo et al., Citation2020).

Table 4. Correlating nutrition education and production diversification to frequency of fruit and vegetable consumption

6. Conclusion and implications

Nutrition education improves dietary diversity and household consumption of fruits and vegetables. Alternative model specifications also show that nutrition education improves the frequency of consuming vegetables and not fruits. Our findings show that, in our study area, households with greater farm production diversity in terms of livestock and crop species have improved dietary diversity and fruit consumption. Households with higher disposable income had better dietary diversity and increased frequency of eating fruits.

The study results have important implications for programming and policy. First, there is scope for government, private sector, and development agencies to roll out various nutrition education and awareness campaigns highlighting the importance of producing and consuming micronutrient-rich fruit and vegetable diets. These awareness campaigns should utilize all information dissemination platforms, such as print and electronic media including social media such as Facebook, Twitter, and WhatsApp. Fruit and vegetable consumption messaging should be both in English and translated to all local languages to ensure wider reach to rural households. In addition, the awareness promotions should be done by all extension services (both public and private especially the agriculture and health extension staff) during physical meetings, field days, and exchange visits where appropriate.

Second, interventions that promote crop and livestock diversification, including household cultivation of nutrient-rich fruits and vegetables, need to be upscaled. The Government of Zimbabwe agricultural subsidy programmes (e.g. Pfumvudza and Presidential Input Schemes) could be avenues for enhancing crop diversification. These schemes have largely provided only cereal seeds (maize, sorghum, and millets) and fertilizers, and there is added value in expanding them to include fruit and vegetable seeds and seedlings in their input package. Third, increasing income-generating programs among smallholder farmers have the potential to boost the growing and eating of fruits and vegetables in Zimbabwe. Overall, nutrition education complemented by farm production diversification and enhanced generation of income should be promoted to increase the growth and consumption of diverse crops including vegetables and fruits.

7. Limitations and areas of further study

This study has associated limitations. First, our study is based on recall and could potentially suffer from the associated recall bias. Second, the use of cross-sectional data does not allow assessment of changes in fruit and vegetable consumption over time and other factors including accessibility, cost, and availability. Third, estimating causality with cross-sectional data requires the use of instruments, which remains a challenge to find. Future studies should rely on panel data to rigorously establish causality.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to the respondents and research assistants for their provision of information and data collection services, respectively. We are grateful to FCDO for financially supporting the program and the study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Conrad Murendo

Conrad Murendo is the Program Learning Advisor within the Monitoring, Evaluation and Learning Unit at Mercy Corps Headquarters. He holds a PhD in Agricultural Economics from the University of Goettingen, Germany. He researches on food and nutrition security, gender, resilience, consumer finance, and technology adoption.

Dowsen Sango

Dowsen Sango is a Monitoring and Evaluation Specialist at the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Zimbabwe. He is an expert in monitoring and evaluation of food and nutrition security, rural development, and resilience programs.

Claudious Hakuna

Claudious Haruna is a Data Analyst at the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Zimbabwe. He possesses extensive experience in monitoring and evaluation of food and nutrition security programs.

Notes

1. A ward is an administrative unit and consist of 5 to 6 villages.

References

- ZIMSTAT. (2018) Income, consumption and expenditure survey report. Zimbabwe National Statistical Agency. Harare.

- Athare, T. R., Pradhan, P., & Kropp, J. P. (2020). Environmental implications and socioeconomic characterisation of Indian diets. The Science of the Total Environment, 737, 139881. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139881

- Bernstein, M. A., Nelson, M. E., Tucker, K. L., Layne, J., Johnson, E., Nuernberger, A., Castaneda, C., Judge, J. O., Buchner, D., & Singh, M. F. (2002). A home-based nutrition intervention to increase consumption of fruits, vegetables, and calcium-rich foods in community dwelling elders. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 102(10), 1421–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0002-8223(02)90315-9

- Bigman, G., & Ryan, A. S. (2021). Healthy eating index-2015 is associated with grip strength among the US adult population. Nutrients, 13(10), 3358. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13103358

- Cameron, A. C., & Trivedi, P. K. (2010). Microeconometrics using Stata. Stata Press.

- Choudhury, S., Shankar, B., Aleksandrowicz, L., Tak, M., Green, R., & Harris, F., Scheelbeek P, & Dangour A. (2020). What underlies inadequate and unequal fruit and vegetable consumption in India? An exploratory analysis. Global Food Security, 24, 100332. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfs.2019.100332

- Darfour-Oduro, S. A., Andrade, J. E., & Grigsby-Toussaint, D. S. (2020). Do fruit and vegetable policies, socio-environmental factors, and physical activity influence fruit and vegetable intake among adolescents? The Journal of Adolescent Health: Official Publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine, 66(2), 172–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.07.016

- Faber, M., Laubscher, R., & Laurie, S. (2013). Availability of, access to and consumption of fruits and vegetables in a peri-urban area in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 9(3), 409–424. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1740-8709.2011.00372.x

- Greene, W. H. (2012). Econometric analysis (7th ed.). Prentice Hall.

- Gullotta, T. P., & Bloom, M. (Eds.). (2014). Encyclopedia of primary prevention and health promotion (Springer reference). Springer.

- Gupta, S., Sunder, N., & Pingali, P. L. (2020). Market access, production diversity, and diet diversity: Evidence from India. Food and Nutrition Bulletin, 41(2), 167–185. https://doi.org/10.1177/0379572120920061

- Habtemariam, L. T., Gornott, C., Hoffmann, H., & Sieber, S. (2021). Farm Production diversity and household dietary diversity: Panel data evidence from rural households in Tanzania. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 5. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2021.612341

- Hirvonen, K., Hoddinott, J., Minten, B., & Stifel, D. (2017). Children’s diets, nutrition knowledge, and access to markets. World Development, 95, 303–315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2017.02.031

- Jacobs, S., Harmon, B. E., Boushey, C. J., Morimoto, Y., Wilkens, L. R., Le Marchand, L., Kröger, J., Schulze, M. B., Kolonel, L. N., & Maskarinec, G. (2015). A priori-defined diet quality indexes and risk of type 2 diabetes: The multiethnic cohort. Diabetologia, 58(1), 98–112. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-014-3404-8

- Kabir, M. R., Halima, O., Rahman, N., Ghosh, S., Islam, M. S., & Rahman, H. (2022). Linking farm production diversity to household dietary diversity controlling market access and agricultural technology usage: Evidence from Noakhali district, Bangladesh. Heliyon, 8(1), e08755. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e08755

- Kissoly, L. D., Karki, S. K., & Grote, U. (2020). Diversity in farm production and household diets: Comparing evidence from smallholders in Kenya and Tanzania. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 4, 77. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2020.00077

- Lallukka, T., Pitkäniemi, J., Rahkonen, O., Roos, E., Laaksonen, M., & Lahelma, E. (2010). The association of income with fresh fruit and vegetable consumption at different levels of education. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 64(3), 324–327. https://doi.org/10.1038/ejcn.2009.155

- LFSP. (2021). Livelihoods and food security programme Zimbabwe. Accessed 3 July. 2021. https://lfspzim.com/what-is-lfsp/background/projects/.

- Long, J. S., Freese, J., Long, J. S., O’Prey, J., Nixon, C., Roberts, F., Dufès, C., & Ryan, K. M. (2014). Regression models for categorical dependent variables using Stata. Oncogene, 33(32), 4164–4172. https://doi.org/10.1038/onc.2013.470

- Madzorera, I., Blakstad, M. M., Bellows, A. L., Canavan, C. R., Mosha, D., Bromage, S., Noor, R. A., Webb, P., Ghosh, S., Kinabo, J., Masanja, H., & Fawzi, W. W. (2021). Food crop diversity, women’s income-earning activities, and distance to markets in relation to maternal dietary quality in Tanzania. The Journal of Nutrition, 151(1), 186–196. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/nxaa329

- Mayén, A. -L., Marques-Vidal, P., Paccaud, F., Bovet, P., & Stringhini, S. (2014). Socioeconomic determinants of dietary patterns in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 100(6), 1520–1531. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.114.089029

- Miller, V., Mente, A., Dehghan, M., Rangarajan, S., Zhang, X., Swaminathan, S., Dagenais, G., Gupta, R., Mohan, V., Lear, S., Bangdiwala, S. I., Schutte, A. E., Wentzel-Viljoen, E., Avezum, A., Altuntas, Y., Yusoff, K., Ismail, N., Peer, N., Chifamba, J. … Mapanga, R. (2017). Fruit, vegetable, and legume intake, and cardiovascular disease and deaths in 18 countries (PURE): A prospective cohort study. The Lancet, 390(10107), 2037–2049. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32253-5

- Miller, V., Webb, P., Micha, R., & Mozaffarian, D. (2020). Defining diet quality: A synthesis of dietary quality metrics and their validity for the double burden of malnutrition. The Lancet Planetary Health, 4(8), e352–370. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(20)30162-5

- Miller, V., Yusuf, S., Chow, C. K., Dehghan, M., Corsi, D. J., Lock, K., Popkin, B., Rangarajan, S., Khatib, R., Lear, S. A., Mony, P., Kaur, M., Mohan, V., Vijayakumar, K., Gupta, R., Kruger, A., Tsolekile, L., Mohammadifard, N., Rahman, O. … Mente, A. (2016). Availability, affordability, and consumption of fruits and vegetables in 18 countries across income levels: Findings from the Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology (PURE) study. The Lancet Global Health, 4(10), e695–703. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(16)30186-3

- Miyata, S., Minot, N., & Hu, D. (2009). Impact of contract farming on income: linking small farmers, packers, and supermarkets in China. World Development, 37(11), 1781–1790. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2008.08.025

- Mokdad, A., El Bcheraoui, C., Basulaiman, M., AlMazroa, M., Tuffaha, M., Daoud, F., Wilson, S., Al Saeedi, M., Alanazi, F., Ibrahim, M., Ahmed, E., Hussain, S., Salloum, R., Abid, O., Al Dossary, M., Memish, Z., & Al Rabeeah, A. (2015). Fruit and vegetable consumption among adults in Saudi Arabia, 2013. Nutrition and Dietary Supplements, 41, 41. https://doi.org/10.2147/NDS.S77460

- Murendo, C., Nhau, B., Mazvimavi, K., Khanye, T., & Gwara, S. (2018). Nutrition education, farm production diversity, and commercialization on household and individual dietary diversity in Zimbabwe. Food & Nutrition Research, 62(0). https://doi.org/10.29219/fnr.v62.1276

- Nandi, R., Nedumaran, S., & Ravula, P. (2021). The interplay between food market access and farm household dietary diversity in low and middle income countries: A systematic review of literature. Global Food Security, 28, 100484. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfs.2020.100484

- Nanney, M. S., Johnson, S., Elliott, M., & Haire-Joshu, D. (2007). Frequency of eating homegrown produce is associated with higher intake among parents and their preschool-aged children in rural Missouri. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 107(4), 577–584. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jada.2007.01.009

- Ochieng, J., Afari-Sefa, V., Lukumay, P. J., Dubois, T., & van Wouwe, J. P. (2017). Determinants of dietary diversity and the potential role of men in improving household nutrition in Tanzania. PLoS One, 12(12), e0189022. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0189022

- Olawuyi, A. T., Adeoye, I. A., & Oyeyemi, A. L. (2018). The prevalence and associated factors of non-communicable disease risk factors among civil servants in Ibadan, Nigeria. PLoS One, 13(9), e0203587. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0203587

- Onyeneke, R., Nwajiuba, C., Igberi, C., Umunna Amadi, M., Anosike, F., Oko-Isu, A., Munonye, J., Uwadoka, C., & Adeolu, A. (2019). Impacts of caregivers’ nutrition knowledge and food market accessibility on preschool children’s dietary diversity in remote communities in Southeast Nigeria. Sustainability, 11(6), 1688. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11061688

- Padrão, P., Laszczyńska, O., Silva-Matos, C., Damasceno, A., & Lunet, N. (2012). Low fruit and vegetable consumption in Mozambique: Results from a WHO STEPwise approach to chronic disease risk factor surveillance. The British Journal of Nutrition, 107(3), 428–435. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114511003023

- Patel, N., Lakshminarayanan, S., & Olickal, J. J. (2020). Effectiveness of nutrition education in improving fruit and vegetable consumption among selected college students in urban Puducherry, South India. A pre-post intervention study. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health, 34(4), 243–248. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijamh-2020-0077

- Pechey, R., Monsivais, P., Ng, Y. -L., & Marteau, T. M. (2015). Why don’t poor men eat fruit? Socioeconomic differences in motivations for fruit consumption. Appetite, 84, 271–279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2014.10.022

- Peltzer, K., & Pengpid, S. (2010). Fruits and vegetables consumption and associated factors among in-school adolescents in seven African countries. International Journal of Public Health, 55(6), 669–678. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-010-0194-8

- Pradhan, A., S, R., Dj, N., Panda, A. K., Wagh, R. D., Maske, M. R., & Rv, B. (2021). Farming System for Nutrition-a pathway to dietary diversity: Evidence from India. PLoS One, 16(3), e0248698. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0248698

- Rasmussen, L. V., Wood, S. L. R., & Rhemtulla, J. M. (2020). Deconstructing diets: The role of wealth, farming system, and landscape context in shaping rural diets in Ethiopia. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 4. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2020.00045

- Roothaert, R., Mpogole, H., Hunter, D., Ochieng, J., & Kejo, D. (2021). Policies, multi-stakeholder approaches and home-grown school feeding programs for improving quality, equity and sustainability of school meals in Northern Tanzania. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 5. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2021.621608

- Sariyev, O., Loos, T. K., & Khor, L. Y. (2021). Intra-household decision-making, production diversity, and dietary quality: A panel data analysis of Ethiopian rural households. Food Security, 13(1), 181–197. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-020-01098-9

- Selvaraj, K., Mondal, A., & Kulkarni, B. (2021). Strengthening agriculture-nutrition linkages to improve consumption of nutrient-dense perishable foods in India - existing evidence and way forward. Journal of Food, Nutrition and Agriculture, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.21839/jfna.2021.v4.7201

- Serra-Majem, L., Román-Viñas, B., Sanchez-Villegas, A., Guasch-Ferré, M., Corella, D., & La Vecchia, C. (2019). Benefits of the Mediterranean diet: Epidemiological and molecular aspects. Molecular Aspects of Medicine, 67, 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mam.2019.06.001

- Shrestha, V., Paudel, R., Sunuwar, D. R., Lyman, A. L. T., Manohar, S., Amatya, A., & Hussain, A. (2021). Factors associated with dietary diversity among pregnant women in the western hill region of Nepal: A community based cross-sectional study. PLoS One, 16(4), e0247085. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0247085

- Sibhatu, K. T., Krishna, V. V., & Qaim, M. (2015). Production diversity and dietary diversity in smallholder farm households. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 112(34), 10657–10662. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1510982112

- Sibhatu, K. T., & Qaim, M. (2018). Farm production diversity and dietary quality: Linkages and measurement issues. Food Security, 10(1), 47–59. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-017-0762-3

- Sinyolo, S., Ndinda, C., Murendo, C., Sinyolo, S. A., & Neluheni, M. (2020). Access to information technologies and consumption of fruits and vegetables in South Africa: Evidence from nationally representative data. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(13), 4880. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17134880

- Szebini, A., Anyango, E., Orora, A., & Agwe, J. (2021). A technical review of select de-risking schemes to promote rural and agricultural finance in sub-Saharan Africa. FAO, AGRA and IFAD.

- Wagner, M. G., Rhee, Y., Honrath, K., Blodgett Salafia, E. H., & Terbizan, D. (2016). Nutrition education effective in increasing fruit and vegetable consumption among overweight and obese adults. Appetite, 100, 94–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2016.02.002

- Xu, Y. Y., Sawadogo Lewis, T., King, S. E., Mitchell, A., & Roberton, T. (2021). Integrating nutrition into the education sector in low- and middle-income countries: A framework for a win–win collaboration. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 17(3), e13156. https://doi.org/10.1111/mcn.13156