?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

In the wake of climate change, failing of conventional food systems, and low agricultural productivity, baobab tree is central to the livelihoods of many individuals in ASALs. In Kenya, the baobab is a high-priority tree with high economic value than use value. However, products derived from the tree remain rare and only a few are traded. This paper sought to establish the determinants of awareness and attitudes of retailers toward baobab products. Descriptive statistics, Zero-truncated Poisson model, and Exploratory factor analysis were employed to assess awareness levels, attitudes, and their underlying determinants. Data was collected from 352 retailers in rural and urban markets. Descriptive indicated a low product awareness across markets. Further, attitudes of retailers towards baobab were positive and relatively homogeneous. Out of the 13 statements, 10 scored positively on the Likert scale. The model revealed that gender, age, education, years in retailing, and group membership positively influenced awareness, while distance to the market and income from other sources had a negative influence. Exploratory factor analysis generated five factors that explained 57.93% of the total variance. “Source of employment”, “livelihood and survival”, and “nutritive value and freshness,” had the highest factor loadings respectively. The study, therefore, recommends the need to develop strategies that could promote awareness of baobab products. This includes; designing appropriate educational and training programs that focus on gender disparity, youth, and nutritional value. Likewise, governments and the private sector should invest in baobab value chain and infrastructure to enhance market employability, access and availability of products.

1. Introduction

Access to quality, healthy and nutritious food is a fundamental human right and a prerequisite for people to attain their full physiological potential. However, access to nutritious, safe, and sufficient food across the globe has remained a challenge (United Nations, Citation2021). Indigenous fruit trees (IFTs) have been identified as one of the pathways with the potential to address these unprecedented challenges (Omotayo & Aremu, Citation2020). IFTs thrive well in harsh climatic conditions where environmental degradation and crop failure are common (Kehlenbeck et al., Citation2013; Muok, Citation2019). Nonetheless, the potential for IFTs remains untapped. Hence, their products realize limited commercialization (Muok, Citation2019). Baobab is an example of an IFT that remains underutilized.

Baobab (Adansonia digitata L.) is among the leading IFTs that provide non-timber benefits with a projected annual income of $1 billion for producer countries (UNEP, Citation2006). It is a multifunctional plant with benefits ranging from its role as a source of food, medicine, fodder, and raw material in processing (Chabite et al., Citation2019; Rahul et al., Citation2015). Besides, Buchmann et al. (Citation2010) documented different uses of baobab in Benin and Mali while in Burkina Faso, Citation2012 recorded

uses. The magical tree also ensures environmental sustainability since its products are harvested without affecting forest structure (Asogwa et al., Citation2021). Hence, trading with baobab not only conserves the environment but also provides a great opportunity for income generation, particularly for rural communities and other stakeholders (Abdelrham & Adam, Citation2020; Fischer et al., Citation2020; Kaimba et al., Citation2021).

Following the acceptance of baobab pulp as a novel food product by the European Union (European Union, Citation2008) and the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), there has been increased evidence of baobab products in both local and international markets. For instance, in the European markets, over 300 products containing baobab have been recorded (Gebauer et al., Citation2016) while in Africa, Darr et al. (Citation2020) documented baobab products in Malawi retail markets. Moreover, baobab products in Kenya remain rare, and only a few informally processed are traded (Jäckering et al., Citation2019; Kaimba et al., Citation2020). Thus, the products occupy a small market share. This shows a clear indication that there is still low product awareness and under-developed market for baobab products (Omotayo & Aremu, Citation2020). Hence, a nuanced understanding of attitudes and awareness of baobab products at the retail level can enhance market development and commercialization of the products.

Attitude has been widely accepted as a “learned predisposition to respond favorably or unfavorably towards a product” (Fishbein & Ajzen, Citation1975; Junges et al., Citation2021). This concept has several implications for retailers’ behavior. First, attitudes are learned. Therefore, they may develop through direct experience with the product or via information gathering from other individuals. Second, attitudes are predispositions and thus they reside in the mind (Junges et al., Citation2021). The third implication is that attitudes are consistent and they reflect individuals’ behavior regarding a particular product (Franke & Maximillians, Citation1999). Moreover, attitudes are affected by various factors (Cicia et al., Citation2021). Hence, retailers may have different attitudes toward the same product.

Awareness plays a crucial role in decision-making regarding product retailing. It enables retailers to answer questions such as; what product to trade, why trade with a certain product over the other, and by how much. Hence, awareness can possibly influence the choice of the products retailers trade with. Also, awareness enhances market development (Omotayo & Aremu, Citation2020) and enables the value chain actors to perform their tasks effectively (Endsley & Garland, Citation2000). However, retailer awareness has majorly been associated with “brand awareness” (Allen et al., Citation2016; Dabija & Nicoleta, Citation2011), which is expressed as the extent to which consumers recognize or recall a particular retailer in a certain category (Pappu & Quester, Citation2006). Nonetheless, the ability of retailers to recognize and recall various products has been neglected by research.

In the paper, the determinants of awareness and attitudes of retailers toward various baobab products are reported. This is significant since it addresses issues in the baobab retail sector in Kenya where it plays a crucial role in economic development (Kiptoo, Citation2017) and represents the largest proportion among the value chain actors (Shaikh & Gandhi, Citation2016). Despite the enormous contribution of the sector, baobab products remain rare and unknown among retailers. Furthermore, the empirical evidence regarding retailers’ attitudes and awareness of baobab products remains scanty. Therefore, the study provides strategies that retailers can adopt to improve their awareness levels and attitudes. Ultimately, leading to an increase in sales volume, as well as enhancing market development and commercialization of the products.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Research design

The study adopted a cross-sectional survey design. The design was preferred since it allows the researcher to collect sample data to represent the whole population at given a period while maintaining data confidentiality. The data was collected between February 2021 and June 2021 after obtaining a research permit from National Commission for Science, Technology, and Innovation (approval no. 980,188).

2.2. Description of study sites

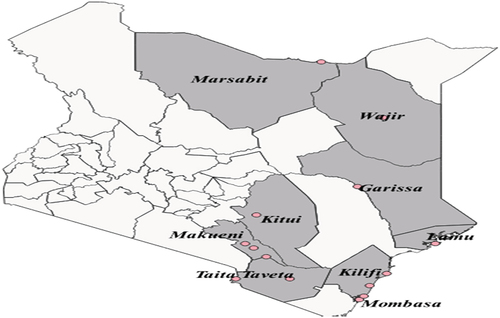

The study was conducted in various Counties in Kenya. Kitui, Garissa, Makueni, Kilifi, Wajir, Marsabit, Taita Taveta, and Lamu were selected purposively to represent rural township markets while Mombasa represented urban markets. Apart from Mombasa County, whose markets operate daily, the markets in Makueni, Kilifi, Kitui, and Taita Taveta were selected purposively to represent the rural township markets as they fall within the baobab growing belt (Fischer et al., Citation2020; Kiprotich et al., Citation2019) and their operations are limited to a specific day of the week. Moreover, Lamu, Garissa, Wajir, and Marsabit counties fall outside the baobab growing belt. However, they were selected to represent rural township markets as they host majority of baobab consumers and traders, and their markets operate on a specific day. On the other hand, markets within Mombasa county were chosen to represent urban markets as they host majority of baobab traders, processors, and consumers (Muriungi et al., Citation2021). Additionally, Mombasa county is among the final urban markets in Kenya where both processed and unprocessed baobab products are traded (Kiprotich et al., Citation2019). Thus, the main markets within the county were selected to represent the urban markets.

Apart from Kitui and Makueni counties, all the other counties were selected purposively due to the existence of Swahili culture (Muslims descent), where consumption of baobab candy is remarkable. Notably, the selected counties in the study are characterized by semi-arid climatic conditions and rapid population growth. Thus, baobab retailing can be used to supplement income and food for poor households within the counties. Figure shows a map of the selected baobab retailing Counties and their respective market locations in Kenya.

2.3. Sampling and data collection

Purposive sampling was adopted to identify and select the study sites where baobab retailing is common while cluster sampling was used to subdivide the sites into two clusters, namely rural townships and urban markets. Following Cochran’s (Citation1977) formulae, a target sample of 385 respondents was not attained due to the outbreak of COVID-19. However, a sample size of 352 baobab retailers was drawn randomly across the markets. This represented about 91.43% of the targeted sample. For inclusion in the sample, all respondents were required to be retailers who trade baobab products and sell to final consumers in the local markets. The study adopted the description of the local market as defined by Shackleton et al. (Citation2007), where local markets are known to exist and operate within cities, towns, neighboring villages, and on roadsides. Such markets are often run by retailers. A structured questionnaire was developed and pre-tested to establish its validity and relevance to the study. After establishing the suitability of the tool, it was administered to the retailers who accepted to be interviewed. The data obtained was on the socio-economic characteristics, awareness levels, and attitudes of retailers concerning baobab products. Lastly, the data was cleaned, coded, and entered into statistical tools such as SPSS version 25 and STATA version 2.1 for analysis.

2.4. Analytical framework

The data from baobab retailers was analyzed using descriptive and inferential statistics. Descriptive statistics such as mean and percentage were used to present summaries of the socio-economic characteristics, awareness levels, and attitudes of the retailers toward baobab products. Independent sample t-test and chi-square were carried out to allow a comparison of differences in socio-economic characteristics and awareness levels of retailers in the two market segments. Zero truncated Poisson (ZTP) model and exploratory factor analysis (EFA) were employed to investigate the determinants of awareness and attitudes respectively.

2.4.1. Retailer awareness

Majority of the studies so far have linked retailer awareness to “brand awareness” (Allen et al., Citation2016; Dabija & Nicoleta, Citation2011). However, in this paper, retailer awareness was defined as the ability of the retailer to recognize and recall various products derived from baobab tree. Moreover, the reviewed literature on the determinants of retailer awareness revealed scanty references. Therefore, the variables used in the study were drawn from other related studies (Omotesho et al., Citation2013; Pambo et al., Citation2014). Retailers were asked to list the number of baobab products they were aware of. This generated an awareness score.

2.4.2. Empirical specification of the model

The zero truncated Poisson (ZTP) model was used to investigate the determinants of retailer awareness towards baobab products. The model was suitable since it uses count data above the truncation point of zero and assumes non-negative integers (Shanker, Citation2017; Zuur et al., Citation2009). The targeted respondents were retailers who traded with at least one baobab product. Hence, the ZTP model was suitable for analysis as there was no possibility of zero occurrences.

The model used was presented as:

Where) and is the dependent variable.

Derived log-likelihood for the above distribution function was:

Log-likelihood in equation is parameterized in terms of linear predictor

Where which forms:

According to Cameron and Trivedi (Citation2007), robust standard errors are recommended for Poisson models. Therefore, differentiating equation () gave us the basis for a robust score and was calculated as shown in equation

:

Where y = Number of baobab products the respondent is aware of. (Awareness score)

= Explanatory variables.

= Poisson distribution means.

β = linear predictor of random variable response.

The study adopted a parametric test that assumes normal distribution criteria for the parameters within the population distribution from which the sample is drawn (Uchechi, Citation2019). Variables used in the model were subjected to normal distribution tests such as skewness and kurtosis. Skewness and kurtosis with a p-value>0.05, indicate that the variable is normally distributed. Years in baobab retailing, distance to the market, and income from other sources did not adhere to the criterion. Thus, they were transformed. Field (Citation2005), suggested the use of a natural logarithm when transforming variables with non-zero value and

if variables have zero value. The variables used are presented in Table .

Table 1. Description of variables hypothesized to influence retailer awareness

A key observation from the study was that some retailers had been involved in baobab retailing for a few months prior to the survey and had covered zero distance to the market as the products they traded with were delivered directly to their stores. Hence, was used to transform the variables. In regard to income from other sources, all respondents had earned a monthly income of more than Ksh 1000 from non-retailing activities. Therefore,

was used to transform the variable, as shown in Table below.

A diagnostic test for statistical problems such as multicollinearity was used to assess the suitability of the variables used in the model. Variance Inflation Factors (VIF) were computed for each variable to detect multicollinearity between independent variables. This involved estimating ordinary least squares regression between each retailer characteristic as the dependent variable with the rest set as independent variables (Otieno, Citation2013). The VIF for each variable was calculated as:

Where is

of the artificial regression with the

independent variable as a dependent variable. VIF<5 suggests the absence of significant multicollinearity (Becker et al., Citation2015).

The study findings revealed that the mean VIF was 1.84, with individual VIF ranging from 1.22 to 3.09, thus indicating the absence of serious multicollinearity. Hence, the variables in Table qualified for inclusion in the ZTP model.

2.4.3. Retailer attitudes toward baobab products

Attitudes are known to cause behavioral change among individuals toward a product (Franke & Maximillians, Citation1999). Therefore, understanding retailer attitudes is key to understanding their behavior (Wadkar et al., Citation2016). For instance, if a retailer has a favorable attitude towards baobab products, the willingness and the likelihood of such a retailer to trade with a wide range of baobab products is expected to be much higher and vice versa. Ultimately, leading to the commercialization of the products.

In this study, attitudes were operationalized as the degree of positive or negative feelings about baobab products among retailers. 13 attitudinal statements concerning baobab products were developed and presented to retailers. Retailers were asked to rate the extent in which they strongly disagree, disagree, neutral, agree, or strongly agree on each of the statement (Likert scale). A Cronbach’s alpha coefficient test of reliability was undertaken to assess the internal consistency of the 13 statements presented in Table . Cronbach’s alpha value is considered adequate (Olaniyi, Citation2019). The study attained an overall alpha value of 0.754, with individual values ranging between 0.724 to 0.89. Hence, all the statements in Table qualified for inclusion in the exploratory factor analysis.

Table 2. Attitudinal statements measuring retailers’ attitudes toward baobab products

After establishing the reliability of the 13 attitudinal statements (Table ), exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was used to condense them into a smaller set of uncorrelated latent variables. EFA was preferred since there were no prior studies on retailer attitudes and predefined structures to the outcome (Child, Citation1990). Principal component analysis (PCA) was used to extract and obtain fewer uncorrelated factors from correlated variables while retaining most of the original information (Jollife & Cadima, Citation2016).

The new sets of latent variables were rotated using orthogonal varimax to obtain a simple structure and enhance the interpretation of the factors. This rotation was suitable since it assumes that all factors are uncorrelated (Dean, Citation2009). Prior to extraction, the study conducted Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) and Bartlett’s test of sphericity (BTS) to assess the sampling adequacy and suitability of the model. KMO and BTS with a significant value of less than 0.05 is considered adequate (Field, Citation2005). Further, the study employed Kaiser rule of eigenvalue to determine the number of factors to be retained. Usually, the factors with an eigenvalue greater than one are retained and explained.

3. Results and discussions

3.1. Socio-economic characteristics of baobab retailers

Table presents the results of a two-tailed t-test and chi-square (χ2) analysis for continuous and categorical characteristics of the baobab retailers. The t-test showed that baobab retailers in urban and rural township markets were relatively similar in age, years of baobab retailing, and income from other sources. However, they differed statistically in terms of household membership, education level, distance to the market, product awareness, and daily business operation. Rural retailers had higher household members (5) compared to their counterparts in the urban market (4). Additionally, urban retailers were more educated with 7 years of schooling compared to rural retailers with 6 years. This was partially due to a higher number of schools in urban areas. Hence, retailers in urban markets seem to have easy access to education. Similarly, retailers in urban markets operated their baobab businesses for more extended hours (10.56) than rural retailers (9.08). This finding was partly due to electricity connectivity inside urban markets, whereas, in rural markets, retailers majorly relied on traditional methods, such as paraffin lumps for lighting. Electricity is a reliable and less expensive source of energy compared to traditional methods. Thus, the urban retailers continued to operate their baobab business for extended hours, especially in the evening.

Table 3. Descriptive statistics for socio-economic characteristics of baobab retailers

On average, the distance to the market differed significantly across the market segments. Urban retailers covered a shorter average distance (46 km) compared to rural retailers (144 km). This was possible since the majority of retailers in the urban markets were more concentrated and lived near the markets. On the other hand, markets in rural areas are sparsely distributed. Therefore, retailers in rural markets had to cover a wider distance to access the markets which operate on a specific day of the week. Product awareness differed statistically across the market segments. Urban retailers were more aware of various baobab products (11) compared to their rural counterparts (9).

The χ2 analysis in Table revealed that marital status, access to formal training, and business registration were relatively similar across the market segments. Nonetheless, gender, access to credit, and group membership had significant differences. Overall, women were more involved in baobab retailing (65%) compared to men (35%). This finding collaborated with those from Muriungi et al. (Citation2021), which showed that baobab activities such as processing are majorly undertaken by women. Moreover, rural markets recorded a higher involvement of women (77%) compared to urban markets (52%). This is possibly attributed to the fact that many women in rural areas earn their income from gathering and selling non-timber forest products (Nemarundwe et al., Citation2008). The results further showed that the urban market segment had a relatively higher number of retailers (49%) who accessed credit facilities compared to their rural counterparts (38.8%). This was partially due to the existence of many credit service providers in urban areas than rural areas. In terms of group membership, about 68.4% and 60% of rural and urban retailers belonged to a trade group respectively. Thus, it was concluded that over 60% of the baobab retailers across the markets belonged to a group.

3.2. Retailer awareness

3.2.1. Descriptive analysis of retailers’ awareness toward baobab products

Table presents the results of the χ2 analysis of retailers’ awareness of various baobab products. Generally, the study revealed a relatively low product awareness across the markets. Out of the 28 products derived from the baobab tree and presented to retailers, only ten (10) were well-known at the retail level. Nonetheless, Table , indicates that retailers in urban markets were relatively more aware of various baobab products (11) compared to their counterparts in rural markets (9).

Table 4. Retailers’ awareness levels of various baobab products

The study further observed a low awareness level of fruit-based products among retailers across the markets. However, baobab juice, candy, processed pulp, and unprocessed pulp on seed were well-known fruit-based products by retailers across the markets. It was observed that urban retailers were more aware of all fruit-based products compared to their counterparts in rural townships, except for baobab sweets and yogurt, as indicated in Table . Baobab porridge, ice cream, juice, sweets, processed pulp, cooking oil, and massage oil were the only fruit-based products that showed significant differences in awareness levels between the retailers in the two markets i.e. rural townships and urban markets.

Firewood (75%) and bowls from shells (50%) were the only well-known waste-related products by retailers across the markets. Retailers in urban markets were more aware of waste-related baobab products than their rural counterparts. Firewood, bowls from the shell, and decoration products were the only waste-related products that showed significant differences in the two markets. In terms of other baobab products, more than half of the retailers across the markets were aware of baobab ropes, baskets, and herbal products besides the use of leaves as vegetables. All the products under this category revealed a statistical difference between the two market segments.

The study concluded that the most well-known baobab products in the retail sector were baobab candy (100%), pulp on seed (99.4%), processed pulp (96.6%), and baobab juice (78.4%) while baobab soda (2%), rat trap (1.4%), chutney (0.9%), and baobab chocolate (0.6%) were the least-known products across the baobab retail markets in Kenya (Table ).

3.2.2. Determinants of retailer awareness of various baobab products

Table presents the empirical findings of the zero truncated Poisson model on the determinants of retailer awareness of various baobab products. The dependent variable was the awareness score.

Table 5. Determinants of retailer awareness level toward baobab products

The log-likelihood across the markets was negative, indicating that all the coefficients in the predictor variables conformed to the nested test model, as indicated in Table . Hence, the estimates obtained are statistically significant and can be relied on. The study revealed that gender, age, education level, years in baobab retailing, group membership, distance to the market, and income from other sources were the significant factors influencing retailer awareness of baobab products across the market segments.

Gender was found to have a positive and significant effect (p < 0.05) on awareness across the markets. However, it was positive and significant (p<0.1) in the urban markets but insignificant in rural markets. This finding was possibly due to male dominance in urban markets (48%) compared to rural markets (23%). Overall, the study revealed that male respondents were comparatively more knowledgeable and aware of various baobab products than female retailers. The age of the retailer was also found to have a significant and positive effect (p < 0.01) on awareness levels across the markets. Older retailers in baobab retailing were more likely to be aware of various baobab products than younger retailers. Older individuals are known to have a high tendency to retain traditional knowledge that has been accumulated over time.

Education level across the markets had a positive significant (p < 0.01) influence on the awareness levels of retailers. This suggests that more educated retailers in the study markets were more likely to be aware of the various baobab products than less educated retailers. This result was expected since more educated retailers are exposed to a broader scope of information, especially on the products they trade with. Therefore, education increases the awareness level of baobab products among retailers. Similarly, years in baobab retailing was found to have a positive and significant relation (p < 0.01) with awareness across the markets. This finding showed that with an increase of one year in baobab retailing, ceteris paribus, the awareness level of baobab products among retailers improved by about 22.5%. This was possibly attributed to the wide knowledge and experience acquired during baobab retailing. Hence, retailers with more years in baobab retailing were more likely to be aware of various baobab products compared to less knowledgeable and less experienced.

Group membership influenced the awareness level of retailers positively (p < 0.01) across the markets, as indicated in Table . Retailers belonging to trade groups were more likely to be aware of various baobab products than those who did not belong to the groups. This finding was possible since group membership provides access to information concerning various products. Hence, retailers with low product awareness within the group can benefit greatly from those with in-depth knowledge regarding various baobab products. Thus, improving the awareness level of baobab products among the members of the groups.

From the pooled data, distance to the market had a negative relation with awareness of baobab products and was statistically significant (p < 0.01). The distance to the market constraint was found to have a negative effect on awareness, such that if the market was far apart by one Kilometre, ceteris paribus, the likelihood of retailers being aware of baobab products was expected to decline by 8.5%. Likewise, income from other sources was also found to be negatively significant (p < 0.01) across the market segments. This implies that as retailers increased their income from non-retailing activities, their awareness level of baobab products decreased, and vice versa. This is possibly attributed to the assertion that retailers with higher income from other sources tend to ignore and neglect baobab retailing and concentrate on those other income opportunities that earn them more.

3.3. Attitudes of retailers toward baobab products

3.3.1. Descriptive analysis of retailers’ attitudes toward baobab products

Table shows the results of the thirteen attitudinal statements presented to the baobab retailers. The study observed that most of the attitudes scores were high on the positive end of the Likert scale (i.e., strongly agree and agree). Out of the 13 attitudinal statements, five of them scored over 85% on the Likert scale responses (both strongly agree and agree), as shown in Table : “baobab products have a long shelf life;” “baobab products are a source of income;” “baobab products are the key source of employment;” “baobab products are profitable;” and “baobab products improve people’s livelihood and health”.

Table 6. Descriptive analysis of retailer attitudes toward baobab products

Four other statements i.e. “by selling baobab products, farmers, processors, and collectors receive good economic returns”, “I can survive with income from baobab products only”, “inputs for baobab business are affordable”, and “baobab products are statements nutritious”, had positive scores of 77.9%, 66.9%, 62.7%, and 60% respectively. Thus, these four statements inherently conveyed positive attitudes towards baobab products. However, despite baobab growing naturally in the majority of rural areas, the statement “I easily access baobab products whenever I need them” scored at the lower positive end of the scale in rural markets (57.3%), compared to a higher score in urban markets (80%). Similarly, the statement that “baobab products are nutritious”, was found to be low positive (48.7%) in rural markets compared to 72.7% in urban markets. This was partly attributed to the high presence of health-cautious customers in urban markets than in rural markets. Hence, the statement scored high in urban markets.

Further, two of the 13 attitudinal statements had a moderate score on the negative end of the Likert scale (i.e. strongly disagree and disagree). The first statement “buyers pay high prices for baobab products” scored 67.1% across the markets. However, it scored higher in rural markets (76.5%) compared to urban markets (52.1%). It was observed that this statement did not adhere to the economic expectations since retailers were expected to have favorable attitudes towards the high purchasing price of baobab products by customers. However, it is important to note that the baobab retail market in Kenya is at a nascent stage and under-developed. Thus, some facets of the markets may not be fully functional hence economic theory and market dynamics may not be applicable in baobab retail markets. The second statement “starting a baobab business requires high capital” had a negative score on the Likert scale. A good percentage of retailers across the markets responded negatively to the statement (73.8%); ultimately making it a positive attitude statement. For example, 78.6% of rural retailers and 68.5% of urban retailers disagreed with the statement, as indicated in Table . Hence, it was concluded that starting a baobab business does not require huge capital.

Lastly, out of the 13 attitudinal statements “selling well-labeled products improves my economic returns” was the only statement with a different direction of responses on the Likert scale (i.e. strongly disagree, disagree, agree and strongly agree) between the markets. In the rural markets, 57.2% of retailers disagreed with the statement while in the urban markets, 55.7% of the retailers responded positively to the statement. This was possibly attributed to the assertion that most retailers in urban markets traded with labeled products. Hence, the statement inherently carried a positive attitude among urban retailers.

The study concluded that retailers across baobab markets have positive attitudes toward baobab products. This finding was in tandem with the study conducted by Kavoi and Kimambo (Citation2021), which revealed that traders have positive attitudes toward Traditional African vegetables (TAV). Additionally, it was concluded that retailers across the markets have relatively homogeneous attitudes towards baobab products, as measured by the Likert scale and presented in Table .

3.3.2. Results from exploratory factor analysis

Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was used to reduce a large group of latent variables measuring retailers’ attitudes toward baobab products into a smaller set of uncorrelated variables. Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) and Bartlett’s test of sphericity (BTS) were undertaken and the results are presented in Table . The study observed a KMO value of 0.69 and BTS of 543.558 with a p-value of 0.000 thus indicating the sufficiency of data for EFA.

Table 7. KMO and bartlett’s test of sphericity of exploratory factor analysis

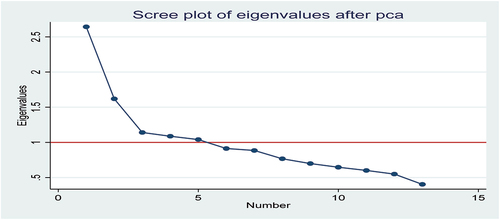

Further, the study employed Kaiser rule of eigenvalue to determine the number of factors to be retained. In the study, five factors met this criterion and were presented by the scree plot in Figure .

The selected and retained factors accounted for 57.93% of the total variance explained as indicated in Table . The first factor accounted for 20.328% of the total variance and was named “source of employment” since it had attributes that were concerned with profitability, income, and employment. This finding suggests that retailers are persuaded that baobab products are profitable, are a key source of income, and can create job opportunities.

Table 8. Exploratory factor analysis for baobab retailers in Kenya

Three attitudinal variables concerning packaging, health, and income of baobab products were loaded in the second factor. The factor accounted for 12.45% of the total variance and was labeled “livelihood and survival”. Packaging and quality attributes of the food products are among the key determinants of retailers’ purchasing behavior, especially when selecting their local suppliers (Nandonde et al. (Citation2016). Hence, these product attributes partly shaped retailers’ attitudes positively toward baobab products. This finding aligns with the survey done by Gracia and Zeballos (Citation2003), which observed that retailers have positive attitudes toward labeling beef products. The third factor was labeled “nutritive value and freshness”. It accounted for 8.78% of the total variance and incorporated three elements focusing on nutrition and shelf life dimensions. The two elements had positive coefficients. Hence, they influenced retailers’ attitudes toward baobab products positively. This finding was consistent with the studies by Rimal and Onyango (Citation2013) and Iwu et al. (Citation2017), who established that freshness, quality, and lifespan of products are the key drivers of purchasing behavior of retailers and food vendors. The third item in this factor “by selling baobab products farmers, producers, and collectors receive good economic returns” represented a negative coefficient (−0.511) for retailers’ attitudes. This was possibly attributed to the seasonality nature of baobab as its harvesting varies across the country (Wanjeri et al., Citation2020). Hence, the economic returns of other value chain actors cannot be linear in the off-season.

Two attitudinal variables concerning the availability and price of the products were loaded into factor four. The factor was termed “Availability and Price,” and it accounted for 8.38% of the total variance, as indicated in Table . Hence, availability and price were among the key factors that influenced retailers’ attitudes toward baobab products. This finding corroborated with those of Rimal and Onyango (Citation2013), which showed that the availability and price of locally produced foods shape the attitudes of retailers. Likewise, Diehl et al. (Citation2015) observed that price affects the perception of retailers toward the choice of fruits to trade with. The fifth and final factor was labeled “input factors” and it accounted for 8.006% of the total variance. It incorporated two attitudinal statements concerning baobab inputs: “inputs for baobab business are affordable” and “starting a baobab business requires high capital”.

4. Conclusion and recommendation

The paper investigated determinants of awareness and attitudes of retailers toward baobab products. Zero-truncated Poisson model and Exploratory factor analysis were used to facilitate data analysis. The findings indicated a low product awareness among retailers across the markets. Gender, age, education level, years in baobab retailing, and group membership influenced awareness positively, while income from other sources and distance to the market had a negative influence.

Further, a good proportion of retailers had positive scores on the Likert scale (i.e. strongly agree and agree). Out of the 13 attitudinal statements concerning baobab products, 10 of them scored positively across the markets. Hence, the study concluded that retailers have positive and relatively homogeneous attitudes toward baobab products. Exploratory factor analysis generated five factors. “Source of employment”, “livelihood and survival”, and “nutritive value and freshness” were the key factors influencing the retailers’ attitudes toward baobab products.

In line with the findings, various recommendations emerge. First, there is a need to design educational and training programs that can improve the awareness levels of baobab products. The programs should focus on gender gap issues, youth and nutritional value. Second, promotional approaches such as product labeling, certification and packaging is essential. Labeling creates awareness on the product while certification and packaging builds confidence and trust. Other approaches include developing sensitization campaigns on nutritional value and income opportunities of baobab, and information dissemination. Such promotional activities will raise retailer awareness and ultimately lead to market development and commercialization. Third, the adoption of effective storage technologies that maintain freshness and nutritive value of baobab is essential. This will enable retailers to trade with baobab products even during off-seasons. Also, national, county governments and the private sector should invest in the baobab value chain and infrastructures to enhance market employability, access and availability of products in the markets. Thus, leading to an increase in the awareness. Lastly, to improve the awareness level, retailers are encouraged to join a trade group and specialize in baobab retailing.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the research grants from the Germany Federal Ministry of Food and Agriculture (BMEL) through the Federal Office of Agriculture and Food (BLE) as a component of the “Value chain, post-harvest losses and producer associations (also known as the BAOQUALITY PROJECT, grant number 2816PROC17).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Kinyili Mutua

Mutua Kinyili is an M.Sc research student in the Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics, Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology. His research interest includes themes on agricultural value chain, food security and food systems, food policy, project management and adoption of technology in agricultural practices.

Muendo M. Kavoi

Muendo M. Kavoi is an Associate Professor of Agricultural Economics at the Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics, Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology. His research focuses on food policy, agricultural value chains in Arid and Semi-Arid lands and agricultural marketing systems

Dagmar Mithöfer

Dagmar Mithöfer is a Professor of Agri-food Chain Management at the Department of Agricultural Economics, Humboldt University of Berlin. Her research focuses on Agri-food value chains, governance, impact assessment, food security and rural development

References

- Abdelrham, T. K., & Adam, Y. O. (2020). Value chain analysis of baobab (Adansonia digitata L .) Fruits in Blue Nile State, Sudan. Agriculture and Forestry Journal, 4(2), 131–19.

- Allen, J., Honatha, C., & Inggrit, L. (2016). The Impact of Retailer Awareness, Retailer Association, Retailer Perceived Quality, and Retailer Loyalty on Purchase Intention in Hypermart Surabaya. Proceedings of the Management Research National Conference, Lombok, Indonesia (pp. 20–22). September.

- Asogwa, I. S., Ibrahim, A. N., & Agbaka, J. (2021). African baobab: Its role in enhancing nutrition, health, and the environment. Trees, Forests and People, 3(May 2020), 100043. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tfp.2020.100043

- Becker, J. M., Ringle, C. M., Sarstedt, M., & Völckner, F. (2015). How collinearity affects mixture regression results. Marketing Letters, 26(4), 643–659. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11002-014-9299-9

- Buchmann, C., Prehsler, S., Hartl, A., Vogl, C. R., Buchmann, C., Prehsler, S., Hartl, A., & Vogl, C. R. (2010). The Importance of Baobab (Adansonia digitata L .) in Rural West African Subsistence — Suggestion of a Cautionary Approach to International Market Export of Baobab Fruits. Ecology of Food and Nutrition, 49(3), 145–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/03670241003766014

- Cameron, C., & Trivedi, P. K. (2007). Essentials of Count Data Regression. A Companion to Theoretical Econometrics, 331–348. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470996249.ch16

- Chabite, I. T., Maluleque, I. F., Mazuze, I., Abdula, R. A., & Joaquim, F. (2019). Morphological Characterization, Nutritional and Biochemical Properties of Baobab (Adansonia digitata L.) Fruit Pulp from Two Districts of Mozambique. EC Nutrition, 14(2), 158–164.

- Child, D. (1990). The essentials of factor analysis (2nd ed.). Cassel Educational Limited.

- Cicia, G., Furno, M., & Del Giudice, T. (2021). Do consumers’ values and attitudes affect food retailer choice? Evidence from a national survey on farmers’ market in Germany. Agricultural and Food Economics, 9(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40100-020-00172-2

- Cochran, W. G. (1977). Sampling Techniques (3rd ed.). John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

- Dabija, D., & Nicoleta, A. I. (2011). Study on retail brand awareness in retail. Journal of Economic Literature, 3(31), 742–748.

- Darr, D., Chopi-Msadala, C., Namakhwa, C. D., Meinhold, K., & Munthali, C. (2020). Processed Baobab (Adansonia digitata L.) food products in Malawi: From poor men’s to premium-priced specialty food? Forests, 11(6), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.3390/f11060698

- Dean, J. (2009). Choosing the Right Type of Rotation in PCA and EFA. JALT Testing & Evaluation SIG Newsletter, 13(3), 20–25.

- Diehl, D. C., Sloan, N. L., Brecht, J. K., & Mitcham, E. J. (2015). What Factors Do Retailers Value When Purchasing Fruits? Perceptions of Produce Industry Professionals. Journal of Food Distribution Research, 46(3), 81–91.

- Endsley, M. R., & Garland, D. J. (2000). Theoretical Underpinnings of Situation Awareness: A Critical Review. Situation Awareness Analysis and Measurement, Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Elbaum Associates http://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&btnG=Search&q

- European Union. (2008). Commission Decision 2008/575/EC. Official Journal of the European Union, 2003(1882), 38–39. https://ec.europa.eu/research/participants/data/ref/h2020/wp/2014_2015/annexes/h2020-wp1415-annex-g-trl_en.pdf

- Field, A. (2005). Discovering statistics using SPSS: (and sex and drugs and rock “n” roll) (2nd ed.). Sage Publication. https://doi.org/10.5860/choice.48-0922

- Fischer, S., Jäckering, L., & Kehlenbeck, K. (2020). The Baobab (Adansonia digitata L.) in Southern Kenya–A Study on Status, Distribution, Use and Importance in Taita–Taveta County. Environmental Management, 66(3), 305–318. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-020-01311-7

- Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research. Addison-Wesley.

- Franke, N., & Maximillians, L. (1999). Retailer Attitudes Towards Manufacturers. Proceedings of the 15th Annual IMP Conference, Durblin (pp. 001–010). University College.

- Gebauer, J., Adam, Y. O., Sanchez, A. C., Darr, D., Eltahir, M. E. S., Fadl, K. E. M., Fernsebner, G., Frei, M., Habte, T. Y., Hammer, K., Hunsche, M., Johnson, H., Kordofani, M., Krawinkel, M., Kugler, F., Luedeling, E., Mahmoud, T. E., Maina, A., Mithöfer, D., & Kehlenbeck, K. (2016). Africa’s wooden elephant: The baobab tree (Adansonia digitata L.) in Sudan and Kenya: A review. Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution, 63(3), 377–399. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10722-015-0360-1

- Gracia, A., & Zeballos, G. (2003). Attitudes of Retailers and Consumers toward the EU Traceability and Labeling System for Beef. Journal of Food Distribution Research, 2005(3), 46–56.

- Iwu, A. C., Uwakwe, K. A., Duru, C. B., Diwe, K. C., Chineke, H. N., Merenu, I. A., Oluoha, U. R., Madubueze, U. C., Ndukwu, E., & Ohale, I. (2017). Knowledge, Attitude and Practices of Food Hygiene among Food Vendors in Owerri, Imo State, Nigeria. Occupational Diseases and Environmental Medicine, 5(01), 11–25. https://doi.org/10.4236/odem.2017.51002

- Jäckering, L., Fischer, S., & Kehlenbeck, K. (2019). A value chain analysis of baobab (Adansonia digitata L .) products in Eastern and Coastal Kenya. Journal of Agriculture and Rural Development in the Tropics and Subtropics, 120(1), 91–104.

- Jollife, I. T., & Cadima, J. (2016). Principal component analysis: A review and recent developments. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, 374(2065), 20150202. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.2015.0202

- Junges, J. R., Do Canto, N. R., & de Barcellos, M. D. (2021). Not as Bad as I Thought: Consumers’ Positive Attitudes Toward Innovative Insect-Based Foods. Frontiers in Nutrition, 8(June), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2021.631934

- Kaimba, G. K., Mithöfer, D., & Muendo, K. M. (2021). Commercialization of underutilized fruits: Baobab pulp supply response to price and non-price incentives in Kenya. Food Policy, 99(101980), 101980. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2020.101980

- Kaimba, G. K., Muendo, K. M., & Mithöfer, D. (2020). Marketing of baobab pulp in Kenya: Collectors’ choice of rural versus urban markets. African Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics, 15(3), 194–212. https://doi.org/10.53936/afjare.2020.15(3).13

- Kavoi, M. M., & Kimambo, J. J. (2021). Attitudes of Farmers, Traders, and Urban Consumers Concerning Consumption of Traditional African Vegetables in Tanzania. Journal of Agriculture Science and Technology, 3(2), 41–51.

- Kehlenbeck, K., Asaah, E., & Jamnadass, R. (2013). Diversity of indigenous fruit trees and their contribution to nutrition and livelihoods in sub-Saharan Africa: Examples from Kenya and Cameroon. Earthscan Routledge, 1(January 2013), 257–269.

- Kiprotich, C., Kavoi, M. M., Mithöfer, D., & Yildiz, F. (2019). Determinants of the intensity of utilization of Baobab products in Kenya. Cogent Food and Agriculture, 5(1), 1704163. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311932.2019.1704163

- Kiptoo, C. (2017). Study on Kenya retail sector prompt payment. Ministry of Industry, Trade, and Cooperatives, 1(1), 1–90.

- Muok, B. O. (2019). Potentials and Utilization of Indigenous Fruit Trees for Food and Nutrition Security in East Africa. Global Advanced Research Journal of Agricultural Science, 8(2). http://garj.org/garjas/home

- Muriungi, M. K., Kavoi, M. M., & Mithöfer, D. (2021). Characterization and Determinants of Baobab Processing in Kenya. International Journal of Food and Agricultural Economics, 9(3), 215–228.

- Nandonde, F., Kuanda, J., Griffith, C., & Griffith, C. (2016). Modern food retailing buying behavior in Africa: The case of Tanzania. British Food Journal, 118(5), 1163–1178. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-09-2015-0335

- Nemarundwe, N., Ngorima, G., & Welford, L. (2008). Cash from the Commons: Improving Natural Products Value Chains for Poverty Alleviation. Proceedings of the 12th Biennial Conference of the International Association for the Study of Commons (IASC): 14th-18th, July, Cheltenham, England (pp. 1–22).

- Olaniyi, A. A. (2019). Application of Likert Scale Type and Cronbach’s Alpha Analysis in an Airport Perception Study. Scholar Journal of Applied Sciences and Research, 2(4), 12–19.

- Omotayo, A. O., & Aremu, A. O. (2020). Underutilized African indigenous fruit trees and food–nutrition security: Opportunities, challenges, and prospects. Food and Energy Security, 9(3), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1002/fes3.220

- Omotesho, K., Sola-Ojo, F., Adenuga, A. H., & Garba, S. (2013). Awareness and Usage of the Baobab in Rural Communities in Kwara State, Nigeria. Ethiopian Journal of Environmental Studies and Management, 6(4), 412–418. https://doi.org/10.4314/ejesm.v6i4.10

- Otieno, D. J. (2013). Market and Non-market Factors Influencing Farmers ’ Adoption of Improved Beef Cattle in Arid and Semi-Arid Areas of Kenya. The Journal of Agricultural Science, 5(1), 32–43. https://doi.org/10.5539/jas.v5n1p32

- Pambo, K. O., Otieno, D. J., & Okello, J. J. (2014). Consumer awareness of food fortification in Kenya: The case of vitamin-A-fortified sugar. 24th Annual World International Food and Agribusiness Management Association Symposium, Cape town, South Africa,16-17, 2–19.

- Pappu, R., & Quester, P. (2006). A consumer-based method for retailer equity measurement: Results of an empirical study. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 13(5), 317–329. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2005.10.002

- Rahul, J., Jain, M. K., Singh, S. P., Kamal, R. K., Anuradha, N. A., Gupta, A. K., Mrityunjay, S. K., & Mrityunjay, S. K. (2015). Adansonia digitata L. (baobab): A review of traditional information and taxonomic description. Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine, 5(1), 79–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2221-1691(15)30174-X

- Rimal, A., & Onyango, B. (2013). Attitudes toward Locally Produced Food Products” Households and Food Retailers. Journal of Food Distribution Research, 44(1), 2000–2002.

- Schumann, K., Becker, U., Thiombiano, A., Becker, U., & Hahn, K. (2012). Uses, management, and population status of the baobab in eastern Burkina Uses, management, and population status of the baobab in eastern Burkina Faso. Agroforestry Systems, 85(2), 263–278. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10457-012-9499-3

- Shackleton, S., Shanley, P., & Ndoye, O. (2007). Invisible but viable: Recognizing local markets for non-timber forest products. International Forestry Review, 9(3), 697–712. https://doi.org/10.1505/ifor.9.3.697

- Shaikh, A., & Gandhi, A. (2016). Small retailer’s new product acceptance in an emerging market: A grounded theory approach. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 28(3), 547–564. https://doi.org/10.1108/APJML-06-2015-0087

- Shanker, R. (2017). Zero-Truncated Poisson-Garima Distribution and its Applications. Journal of Biostatistics and Biometrics, 3(1). https://doi.org/10.19080/BBOAJ.2017.03.555605

- Uchechi, H. O. (2019). Parametric and Nonparametric Statistics. Sokoto Journal of Medical Labaratory, 4(2), 5–15. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781526421036877919

- UNEP. (2006) . Commercialization of non-timber forest products: Factors Influencing Success. Lessons Learned from Mexico and Bolivia and Policy Implications for Decision-makers. UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre.

- United Nations. (2021). The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2021. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2021. https://doi.org/10.4060/cb4474en.

- Wadkar, S. K., Singh, K., Chakravarty, R., & Argade, S. D. (2016). Assessing the Reliability of Attitude Scale by Cronbach’s Alpha. Journal of Global Communication, 9(2), 113. https://doi.org/10.5958/0976-2442.2016.00019.7

- Wanjeri, N., Owino, W., Kyallo, F., Habte, T. Y., & Krawinkel, M. B. (2020). Accessibility, availability, and consumption of Baobab during food emergencies in Kitui and Kilifi counties in Kenya. African Journal of Food Agriculture Nutrition and Development, 20(5), 16403–16419. https://doi.org/10.18697/AJFAND.93.19510

- Zuur, A. F., Ieno, E. N., Walker, N. J., Saveliev, A. A., & Smith, G. M. (2009). Zero-Truncated and Zero-Inflated Models for Count Data. In Mixed effects models and extensions in ecology with R. Springer Science and Business Media. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-87458-6